Abstract

A series of fused naphthalene-based chromophores (PT1–PT7) with an A-π-A configuration was designed through reference compound (PTR) for photovoltaic materials. Structural tailoring was done by incorporating benzothiophene (BT) based acceptor groups at the peripheral positions. Quantum chemical calculations were accomplished at MPW1PW91/6–31(d, p) functional to explore the fundamental photovoltaic and electronic characteristics of newly designed chromophores. Structural modeling with efficient BT-based acceptors had marked an impact on the absorption spectra across all derivatives, leading to a reduction in band gaps. The PT1–PT7 compounds displayed a band gap in the span of 2.267 to 2.137 eV, and broader absorption spectra of 685.109 to 718.666 nm in chloroform. The significant exciton dissociation rate was investigated for entitled compounds due to their smaller binding energy values (Eb = 0.492-0.368 eV). Furthermore, density of states (DOS) and transition density matrix (TDM) maps confirmed efficient transfer of charge from π-spacer in HOMO to BT acceptors in LUMO. In all the designed compounds PT5 displayed the narrowest band gap (2.137 eV), the highest bathochromic shift (718.666 nm), and the lowest Eb (0.492 eV), illustrating suitable candidate for photovoltaic materials. Moreover, open-circuit voltage (Voc) analysis was conducted with respect to HOMODONOR and LUMOPC61BM. All the designed derivatives are estimated to exhibit notable PCEs with good FF values. Thus, these findings illustrated that molecular engineering through BT based acceptors could be utilized as efficient technique for obtaining significant photovoltaic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, organic solar cells have gained a significant attention due to their, less toxicity, light-weight, simple solution-processing ability, high flexibility and low cost1. The photoactive layer of an organic photovoltaic cell usually consists of a p-type organic semiconductor to donate electrons and an n-type material to accept them. Fullerenes, particularly [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PC61BM) and [6,6]-phenyl-C71-butyric acid methyl ester (PC71BM) etc., have long been the dominant acceptor materials due to their remarkable electron affinity and charge transport properties. The power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of fullerene-based OPVs have surpassed 12% using blends of narrow bandgap polymer donors and fullerene acceptors in single-junction devices2,3,4. However, they also come up with certain drawbacks, such as high costs, less stability, week visible region absorption, limited electronic tunability and heating-induced morphological instability5. To address these limitations and improve solar cell efficiency, researchers have focused on developing and manufacturing fullerene-free OSCs6. The non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) offer advantages over fullerene-based acceptors, including easier synthesis, better solubility, environmentally friendly solvent compatibility, and structural flexibility for optimal frontier energy level matching7,8. Furthermore, NF small molecule acceptors exhibit excellent optical absorption characteristics, effectively broadening their absorption range into the infrared spectrum. Additionally, these type of compounds, featuring a fully conjugated structure, facilitate efficient electron acceptance and electron transport, promoting electron distribution at the donor-acceptor (D/A) interfaces. Recently, NF-OSCs have been divided into two categories: polymer solar cells (PSCs) and small molecular acceptors (SMAs). SMAs-based solar cells show better optoelectronic properties than PSCs9. The NFA molecules offer a diverse of structural designing possibilities including D-A-D, A–π–D–π–A and A–D–A. However, the chromophores with A–D–A configuration are largely utilized by integrating distinctive core elements such as donors, π-linkers, and terminal acceptor functions. Moreover, the conjugation in non- fullerene chromophores with strong absorption parameters can enhanced via attachment with chloro, cyano and fluoro moieties over NFA framework. The power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of A-D-A-based non-fullerene OPVs have rapidly surpassed 19%, with continuous advancements in NFA structures setting new efficiency records10. The PCE and FF are critical parameters in determining the overall performance of OSCs, as PCE reflects the ability to convert absorbed light into electricity, while FF indicates the quality of charge collection and transport within the device11. High PCE and FF are essential for achieving optimal device performance, making them key metrics in evaluating new materials for OSCs12. Studies in the literature reveal that the integration of benzothiophene acceptors, along with electron-withdrawing groups, improves the charge transfer directed towards acceptor regions. Incorporating benzothiophene-based extended acceptors lowers the LUMO level while keeping the HOMO level unchanged. This results in a notable improvement in open-circuit voltage (Voc) and short-circuit current density (Jsc) in photovoltaic materials13. In the light of these insights, this report introduces seven new non fullerene A-D-A type chromophores, designated as (PT1-PT7) derived from the parent compound PTT-2FIC14. The reference compound (PTR) is designed by altering the terminal acceptor unit of parent chromophore containing two 6-difluoro-1,1- dicyanomethylene-3-indanone units attached at the terminals of central core as dihydropyrenobisthieno[3,2- b]thiophene. The central core dihydropyrenobisthieno[3,2-b]thiophene (PTT) of the PTT-2FIC serve as an electron donating group, while terminal units acts as an electron-deficient moieties. Moreover, PTT core based NFAs have several advantages, which includes bathochromic shift, reduced energy gap, improved molecular alignment and enhanced charge carrier mobilities due to resonance for both holes and electrons14. A thorough literature review revealed that photovoltaic studies of the designed chromophores have not been reported previously. We examined the effect of various terminal acceptor groups on the optoelectronics and charge transfer phenomenon of the newly designed compounds through DFT/TD-DFT approaches to evaluate their efficacy as efficient OSCs materials for advanced photovoltaic devices.

Computational study

All the quantum chemical investigations (DFT/TD-DFT) calculations for the PTR and PT1-PT7 were carried out using the Gaussian 09 software package15. Input file generation and results visualization were obtained by using of Gauss View 6.0.16 software16. To select the most suitable functional, a bench marked study was carried out between experimental and simulated results λmax values for PTR chromophore. For this purpose, first of all the geometrical optimization of reference compound was accomplished at four hybrid functionals B3LYP17, CAM-B3LYP18, MPW1PW9119, and B3PW91 with the 6-31G(d, p) basis set in chloroform solvent. Then these ground state geometries were utilized to carried out UV-Vis calculation at above mentioned functionals. The simulated values for these functionals were calculated as B3LYP: 797, CAM-B3LYP: 556, MPW1PW91:750 and B3PW91: 801 nm in chloroform media and reported experimental value of PTR is 707 nm14. Among these, the absorption spectrum obtained using the MPW1PW91 functional showed the best alignment with the experimental data (Fig. 1). Therefore, all derivatives were optimized at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d, p) level. Using optimized geometries, UV-Visible spectra, FMOs, TDMs, electron-hole distribution, DOS, PCE, radiative lifetime and FF analyses were calculated at the DFT/T-DFT of MPW1PW91/6-311G(d, p) level. Time-dependent DFT was employed to evaluate the properties of the excited states, i.e., absorption spectra, TDM, FMOs, and electron-hole analyses and photovoltaic characteristics. Various software, including PyMOlyze 1.120, Multiwfn 3.721, Origin 6.022, Avogadro23, and Chemcraft24, were employed to analyze results obtained from output files.

Results and discussion

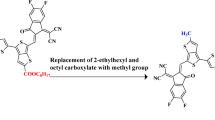

The present study aims to investigate the effect of benzothiophene based end capped acceptor units on optoelectronics, charge transfer phenomenon and photovoltaic characteristics of newly designed NFAs. For this purpose, PTR is utilized as a reference compound following by structural modulation of terminal acceptor units of the parent compound (PTT-2FIC) which is taken from literature14. The terminal acceptors of parent compound namely 6-difluoro-1,1- dicyanomethylene-3-indanone was replaced with more efficient (Z)-2-(2-ethylidene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1-H-benzo[b]cyclopenta[d]thiophen-1-ylidene)malononitrile acceptor in the reference compound (Fig. 2).

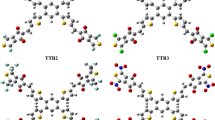

The derivatives (PT1–PT7) were designed by modifying terminal acceptor units of PTR, at both ends of central core. The end-capped changing of the reference compound accomplished with the various acceptor moieties as shown in Fig. 3. The IUPAC names of BT acceptors used in PTR and its derivatives (PT1–PT7) are given in Table S9. Moreover, their optimized and Chemdraw structures are illustrated in Fig. 4 and Figure S2, respectively. The cartesian coordinates of all the studied compounds are shown in Tables S1–S8. The geometrical parameters of entitled chromophores are illustrated in Tables S29–S36 and Figure S3.

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) analysis

FMOs study is regarded as a vital parameter to examine the photovoltaic and optoelectronic properties of organic solar cells (OSCs)25. According to band theory, the conduction band is represented by the LUMO, while the HOMO is denoted as the valence band26. The energy difference (ΔE) signifies the energy necessary for the transfer of electrons between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMOs) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs)27. The efficiency of OSCs and the quantity of current generated are inversely correlated with the band gap values of compounds28. The smaller energy gap facilitates greater efficiency of OSCs due to the ease of electron transport between the HOMO and the LUMO26,29. Power conversion efficiency and open circuit voltages (Voc) can also be well determined by using energy band gap. Table 1 demonstrates the band gap between the LUMO and HOMO orbitals for reference and designed compounds.

Table 1 shows that the energy gap of PTR is 2.267 eV, while the energy values of EHOMO and ELUMO are found as-5.471 and − 3.204 eV, respectively. The computed EHOMO values for (PT1–PT7) are − 5.510, -5.528, -5.671, -5.568, -5.625, -5.649, and − 5.536 eV, with their corresponding ELUMO values are − 3.275, -3.304, -3.449, -3.368, -3.488, -3.480, and − 3.319 eV, respectively. The calculated energy gap values PT1-PT7 are 2.267, 2.235, 2.224, 2.222, 2.200, 2.137, 2.169, and 2.217 eV, respectively. Among all the designed compounds, PT5 shows smallest band gap of 2.137 eV. This might be due to ability of strong withdrawing nitro (–NO2) groups on terminal acceptors which efficiently involve in resonance and transfer its unpaired electron to acceptors. PT6 (2.169 eV) shows a smaller energy gap compared to PT7 (2.217 eV) likely to the enhanced withdrawing influence of two oxygen atoms in the sulphonic acid functionality. It extracts the charge density via inductive effects more effectively than acetic group’s single oxygen atom. Likewise, the less band gap of PT2 (2.224 eV) in comparison to PT1 (2.224 eV) might attributed due to the larger size of chlorine atom which allows it to exert a greater inductive effect than fluorine in PT1. Overall, the energy gap of designed chromophores is as follows: PTR > PT1 > PT2 > PT3 > PT4 > PT7 > PT6 > PT5.

The surface diagrams of HOMO and LUMO facilitate the understanding of charge transference phenomenon of PTR and PT1-PT5 (Fig. 5). Moreover, their energy values and pictographs of HOMO-1, LUMO + 1, HOMO-2, and LUMO + 2 of all the designed compounds are provided in Table S10 and Figure S1, respectively. Figure 4 illustrates that for HOMO the highest electronic density is predominantly located on the π-linker. While in the LUMO, the charge cloud is majorly concentrated on acceptor portions and a small fraction is also present over π-spacer. In summary, the introduction of efficient acceptor with potent electron-withdrawing substituents causes reduction in orbitals band gap. This enables effective charge transfer from the π-spacer to the acceptor, positioning them as promising candidates for organic solar cells (OSCs). The minor variations in the band gaps of the designed derivatives might be attributed to the stability of the energy levels, influenced by the constant donor unit30,31.

Global reactivity parameters

Global reactivity parameters (GRPs) are used to determine the chemical reactivity and stability of investigated compounds by using the energies of HOMO and LUMO32. The GRPs include: global hardness (η), global softness (σ), global electrophilicity index (ω), electronegativity (X), ionization potential (IP)33,34 electron affinity (EA) and chemical potential (µ)35. GRPs are calculated by utilizing (Eqs. 1–7) that are given below. Equation (8) is used to obtain the maximum charge transfer index (ΔNmax)36.

The ionization potential (IP) and electron affinity (EA) of the aforementioned chromophores define their HOMO and LUMO energies, respectively. The electron-donating and accepting potential of the molecules can be assessed by their respective IP and EA values37. Additionally, electronegativity (X) is an important parameter38 that explains a molecule’s capacity to pull an electrons towards itself39. The chemical stability of all the examined molecules is evident from the negative values of the chemical potential (µ) presented in Table 2. Among all the designed compounds PT3 shows the highest ionization potential at 5.671 eV, whereas PT1 displays the lowest value of 5.51 eV. Higher ionization potential values indicate enhanced stability and chemical inertness. The decreasing trend ionization potential is: PT3 (5.671 eV) > PT4 (5.568 eV) = PT7 (5.568 eV) > PT6 (5.649 eV) > PT5 (5.625 eV) > PT2 (5.528 eV) > PT1 (5.51 eV) > PTR (5.471 eV). The relationship between global softness (σ) and global hardness (η) is connected to Egap, offering a valuable understanding of the reactivity of compounds. Similarly, compounds with a smaller Egap display enhanced softness and polarizability, indicating higher reactivity. PT5 is observed as softer and more reactive compound owing to its high global softness value of 0.468 eV−1. Additionally, Table 2 reveals that PT5 possesses the smallest global hardness (η) value, indicating its lower stability and greater reactivity. The global hardness follows a descending order: PTR (1.1335 eV) > PT1 (1.1175 eV) > PT2 (1.112 eV) > PT3 (1.111 eV) > PT4 (1.1 eV) = PT7 (1.1 eV) > PT6 (1.0845 eV) > PT5 (1.0685 eV). The ΔNmax values show that the PT5 compound has the greatest value at 4.264 eV, confirming a constant charge transfer within this compound. Conclusively, PT5 stands out the most suitable compound for photovoltaic applications among all designed compounds due to its greatest softness, lowest hardness and smallest energy gap value of 2.137eV.

UV-visible analysis

The absorption spectra of excited states of the designed chromophores PTR and PT1-PT7 are being examined using the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d, p) level of TD-DFT to measure their absorption behavior40. The maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax), excitation energies (Ex), oscillation strengths (fos) and molecular orbital contributions in both the chloroform solvent and gas phase are shown in Tables S11-S12 of supplementary section, respectively. Moreover, additional information is given in Tables S13-S28. The introduction of potent electron-withdrawing moieties in the designed derivatives causes an increase in λmax along with a decrease in excitation energy as compared to reference compound. Figure 6 depicts the absorption spectra of reference and newly designed chromophores with absorbance in the visible range.

In gaseous phase, the highest λmax values for all derivatives fall within the 652–678 nm range, surpassing the absorption peak of PTR as 640.845 nm. Out of all the designed compounds, PT5 exhibits the highest absorption peak (678.399 nm) with lowest excitation energy value (1.828 eV), owing to the electron-withdrawing nitro groups in the acceptor units41. The less bandgap with lower transition energies contribute collectively to enhance the charge mobility42 and increased power conversion efficiency43. Table S12 shows that all designed compounds exhibit enhanced absorption in comparison to the reference compound. The descending pattern of λmax is as follows: PT5 (678.399 nm) > PT3 (676.363 nm) > PT6 (671.673 nm) > PT4 (664.438 nm) > PT7 (656.070 nm) > PT2 (655.031 nm) > PT1 (652.137 nm) > PTR (640.845 nm).

In solvent phase, all the investigated chromophores have comparable results with each other. The computed λmax for all chromophores in solvent phase ranges from 685.109 to 718.666 nm. The increasing trend of absorption maximum solvent phase is as follow: PTR > PT1 > PT2 > PT5 > PT7 > PT3 > PT4 > PT6.The modification of the end-group acceptors, as previously discussed, proves to be an effective method for fine-tuning of photovoltaic and optoelectronic characteristics. This approach successfully decreases excitation energy and enhances absorption wavelength (λmax). Above discussion concludes that, all above mentioned compounds specifically PT5 would be used as an excellent chromophore for OSCs material.

Density of States (DOS)

To further support the FMOs of the examined compounds, DOS analysis was performed to access their electronic properties. It represents the quantity of electronic states per unit energy and volume. DOS diagrams provides insight into overall electronic density distribution for the HOMOs and LUMOs within the molecule, as well as determine the energy band gap44. The vertical axis of the DOS plot displays the electronic density at different levels of energy whereas the horizontal axis signifies energy band gap between HOMO and LUMO segment exhibiting right side energy values signifies the HOMOs, while the portion with left side energy values denotes the LUMOs. In this report, DOS analysis is conducted on the examined chromophores using the MPW1PW91 level of DFT with the 6-31G(d, p) basis set. The aim of this investigation is to examine the charge transfer rate, and the outcomes depicted in Fig. 7. These findings indicate that the distribution pattern of charges around the HOMOs and LUMOs of studied compounds is impacted by the nature of electron-withdrawing terminal acceptors. To elucidate the DOS analysis, all the designed compounds were divided into two parts: acceptor and the π-spacer. Moreover, Table 3 shows that the electronic distribution pattern for the acceptor ranging from 53.8 to 67.8% contributing to the LUMO, and 11.0 to 11.9% contributing to the HOMO for PTR and PT1-PT7. Likewise, the π-spacer exhibits contributions of 88.1 to 89% to HOMO and 32.8 to 46.2% to the LUMO for PTR and PT1-PT7. Figure 5 shows that in all compounds highest charge density is observed at π-spacer part denoted by red line at -5.6 eV while the greatest charge dispersion peak for LUMO is green and occurs on terminal acceptor units at -3.2 eV. Overall, DOS analysis reveals significant demonstrates a substantial transfer of charge from the π-bridge to the terminal acceptor groups across all the examined compounds.

Open circuit voltage (V oc)

Open-circuit voltage (Voc) analysis measures the OSC’s efficacy, device competence, and maximum current output from any optical material45. In solar devices, Voc is determined under zero voltage conditions. The open circuit voltages are primarily influenced by the type of current present, which are either photo-generated current or saturation voltages. The performance of solar cells is significantly influenced by the presence of these two currents46,47. The Voc correlates with the energy gap between the HOMO of the donor (D) and the LUMO of the acceptor (A) molecules (HOMOdonor-LUMOacceptor). To compute the Voc values of our designed molecules, we utilized a widely recognized acceptor polymer PC61BM, with simulated EHOMO value of -6.10 eV and ELUMO of -3.70 eV at M06/631G(d, p). The Theoretically, the Voc values for all the studied compounds are computed using the Eq. (9)48 reported by Scharber and his colleagues49.

The main objective of Voc analysis is to correlate the donor’s HOMO of tailored compounds to the LUMO of the acceptor polymer PC61BM. Table 4 presents the Voc values for the compounds under investigation. All our tailored chromophores exhibit higher Voc values compared to the reference compound (PTR), which has a Voc of 1.471 V. Among all the designed chromophores, PT3 with reference to the Eg of HOMO donor and LUMO Acceptor observed with highest Voc value of 1.671 V. Table 4 illustrates that the Voc values for PT1-PT7 calculated based on the energy difference between HOMODonor and LUMOPC61BM, found to be 1.510, 1.528, 1.671, 1.568, 1.625, 1.649, and 1.536 V, respectively. The Voc values of the designed chromophores follow a decreasing trend: PT3 > PT6 > PT5 > PT4 > PT7 > PT2 > PT1. As mentioned earlier, the Voc value primarily relies on the HOMO energy level of donating moiety and LUMO level of acceptor functions. A reduced LUMO level of the acceptor results in higher Voc and improved optoelectronic properties. The electrons transfer rate from HOMO of donor molecules is enhanced by a low-positioned acceptor LUMO. Additionally, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap between acceptor and donor regions boosts PCE values. The acceptor polymer PC61BM have their LUMO levels positioned below the LUMO level of the donor compounds. This particular arrangement of molecular orbitals enhances optoelectronic performance by facilitating the transfer of electrons from the electron-rich polymer to the electron-deficient segment. Computed Voc values, along with the optimized bandgap energies, suggest that the designed chromophores have strong potential for achieving PCEs, highlighting their suitability for real-world OSCs applications.

Fill factor, power conversion efficiency and radiative lifetime

The fill factor (FF) is essential in determining the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of organic photovoltaic (PV) devices. However, the factors that substantially influence the fill factor (FF) are the series resistance (Rs).and shunt resistance (Rsh)50. Theoretical prediction of the shunt resistance (Rsh) and series resistance (Rs) for organic materials continues to be a difficult task. Therefore, under ideal conditions, the fill factor (FF) can be expressed as shown in Eq. (10)51.

Equation (10) presented includes the variables e, T, KB, and Voc, which correspond to the elementary charge, temperature (300 K), Boltzmann constant, and open-circuit voltage, respectively. The Boltzmann constant, represented as KB, is valued at 1.380649 × 10−23 joules per kelvin (JK−1) or 1.380649 × 10−16 ergs per kelvin. The power conversion efficiency (PEC) of the chromophores under investigation was determined using Eq. (11)52.

The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of a molecule is affected by the short-circuit current Jsc, FF, and Voc53. The duration of the first excited state’s existence shows a crucial role in assessing charge transfer efficiency. A longer excited state lifetime significantly enhances charge transfer by allowing the molecule to remain in a cationic state for a prolonged period, thereby improving charge transfer conductivity. Prolonging the excited state lifetime also minimizes charge recombination, leading to higher solar cell efficiency. Additionally, an extended radiative lifetime assists the transfer of electrons from the LUMO of donor part to the LUMO of acceptor regions which enhances light-emitting efficiency (LEE)54,55.

The impact of absorbed radiation on the cell exhibits an opposing nature. The measured Voc values for the investigated compounds range from 1.471 V to 1.671 V. A linear relationship exists between FF and Voc, leading to higher FF values for chromophores with elevated LUMO levels. The calculated FF values are provided in Table 4, demonstrating the correlation between FF and Voc. Among all derivatives, PT3 stands out with the highest PCE of 28.102%, indicating superior photovoltaic performance. Additionally, PT3 exhibits a fill factor (FF) of 0.921, further supporting its efficiency as a promising chromophore. The observed PCE values for the designed chromophores follow a decreasing trend: PT3 > PT6 > PT5 > PT4 > PT7 > PT2 > PT1 > PTR. The calculated radiative lifetimes of the compounds PTR and PT1-PT7 reveal interesting trends associated with their excitation energies and oscillator strengths. The radiative lifetime (τ) provides insights into the exciton recombination dynamics, directly influencing the photovoltaic performance of the designed compounds. The observed trend, where all derivatives exhibits the longest radiative lifetime (0.218 × 10−15 s to 0.411 × 10−15 s) compared to PTR (0.214 × 10−15 s), suggests that excitons in derivatives persist longer before recombination. While longer radiative lifetimes are generally associated with improved exciton stability and enhanced light absorption, they may also indicate slower charge transfer, leading to increased recombination losses and reduced charge extraction efficiency. To optimize device performance, a balance between exciton stability and charge transport must be maintained. Structural modifications, such as tuning the electronic interactions within the donor-acceptor framework or optimizing molecular packing, could help in mitigating recombination losses while preserving light-harvesting efficiency. These findings suggest subtle variations in the molecular orbital contributions and transition dynamics, reflecting the influence of electronic structure on photophysical properties. The comparative graphs shown in Fig. 8 illustrate the performance comparison of PTR and PT1–PT7, specifically depicting the trends of Voc vs. PCE and FF vs. PCE.

Transition density matrix

The transition density matrix (TDM) study is important to examine and interpret the charge-transfer excitation processes56 in PTR and PT1-PT7. Therefore, it is considered a key factor in assessing the efficiency of OSCs as it explains the charge transfer process. In this study, hydrogen atoms are excluded due to their negligible contribution to transitions. Figure 9 displays the TDM heat maps in S0 to S1 state of examined compounds computed at MPW1PW91/6-31G(d, p)functional. For TDM analysis, all compounds have been divided into two segments end capped acceptor (A) and π-spacer. Among all the designed compounds, the TDM heat maps shows effective diagonal charge transfer coherence on π-spacer and terminal acceptors (Fig. 9). This diagonal charge transfer occurs from the acceptor through the π-bridge, reveals the formation of hole-electron pairs that progress diagonally towards acceptor units. Furthermore, the existence of red and green regions in TDM pictographs validates the occurrence of charge transfer in π-linker and acceptor moieties. The presence of electronic cloud at the acceptor terminals shows that end-capped acceptors modeling approach can be used to design optimized acceptor materials. In short, TDMs maps offer a direct and efficient exciton dissociation in the excited state, for all the designed chromophores, showing their significant potential for application in OSCs42.

Exciton binding energy (E b)

Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) plays a crucial role in evaluating the potential for exciton separation, optoelectronic properties, and working efficacy of OSCs57. Moreover, Eb ascertain the intensity of Columbic forces between electrons and holes. A lower binding energy leads to reduced Columbic interactions, promoting greater charge segregation leading to improved output in organic solar cells58. The Eb for the reference (PTR) and the designed compounds (PT1-PT7) was calculated using Eq. (12)59.

Eb is the binding energy, Eopt denotes the first singlet excitation energy, and EL−H defines the HOMO and LUMO gap as shown in Eq. (12).

Generally, materials with binding energy (Eb) values of 2.1 eV or lower are considered effective for organic solar cell applications with high open-circuit voltage. Interestingly, all investigated compounds exhibit Eb values below 2.1 eV, as indicated in Table 5. The values of binding energy of examined compounds decrease in the following trend: PT3 (0.492 eV) > PT7 (0.475 eV) > PT4 (0.474 eV) > PT6 (0.444 eV) > PTR (0.443 eV) > PT2 (0.436 eV) > PT1(0.425 eV) > PT5(0.368 eV). Among all the designed compounds, PT5 shows the lowest Eb value that indicates its greater optoelectronic characteristics with greatest efficacy in exciton dissociation.

Electron-hole analysis

The analysis of hole-electron interactions is carried by using the Multiwfn 3.8 software. It is a highly valuable approach for understanding the characteristics of electron excitations. Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive insight into various electron transfer properties60. Figure 10 displays that the highest hole intensity occurs at the carbon atoms (C5 and C12) in the π-spacer, whereas the greater electron intensity is present at the carbon atoms (C33 and C36) of the acceptor part. PT1 and PT2 have the greater hole density at carbon atom (C5 and C12) and electron intensity at carbon atoms (C33 and C36) of benzothiophene-based acceptors. Similarly, the highest hole density for PT3 and PT5 is found to be thick at C5 and C12 in the π-spacer, while for PT3 is detected at (C36 and C41), and for PT5 present at oxygen atom (O45) of the acceptor region. For PT4, PT6, and PT7, the highest electron intensity is located at C33 and C36, C38 and O45, and C38 and C36 in the terminal acceptors, respectively. Whereas, their highest hole density is found at C13, C5, and C11 of the central core π-spacer. In all the examined compounds the electronic cloud is found dense at the electronic band contrary to the hole density at hole band, suggesting that they exhibit characteristics of electron-rich materials.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, novel naphthalene-based compounds were designed by altering the terminal acceptors with more potent benzothiophene based acceptor units. This structural modification proved a crucial strategy to achieve greater redshifts while maintaining a reduced energy gap. Among all the designed compounds, PT5 was observed with lowest band gap (2.137 eV) and highest red shift absorption (678.399 nm). Similarly, PT5 was found with the greater softness (0.468eV), lower hardness (1.0685 eV) and lower binding energy (0.368 eV) values than all other designed compounds. Moreover, TDM analysis revealed that the end-capped acceptors modification might pull the electronic density, thus significantly enhanced the charge transfer rate. In addition, Voc was calculated for the HOMODonor and LUMOPC61BM, and all of the derivatives exhibit greater voltage findings to that of reference chromophore. The Voc values of the designed compounds are found to be in descending order as PT3 > PT6 > PT5 > PT4 > PT7 > PT2 > PT1. Further analysis of fill factor and power conversion efficiencies revealed that PT3 achieved the highest FF of 0.921 and a PCE of 28.102%, indicating its strong photovoltaic performance. The above results offer valuable insights for experimentalists, suggesting that the studied compounds might hold significant promise for the development of OSCs due to their suitable photovoltaic properties. Future work is recommended to focus on experimental validation and optimization of PCE, FF, and radiative lifetime to enhance OSC performance.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Abbas, F. et al. Body centered non-fullerene acceptors substitution on triangular shaped Sub-phthalocyanines (SubPcs) based ADA organic solar cells: A step toward new strategies for better performances. Opt. Quantum Electron. 54, 1–15 (2022).

Deng, D. et al. Fluorination-enabled optimal morphology leads to over 11% efficiency for inverted small-molecule organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 13740 (2016).

Zhang, F., Inganäs, O., Zhou, Y. & Vandewal, K. Development of polymer–fullerene solar cells. Natl. Sci. Rev. 3, 222–239 (2016).

Temimei, F. A. A. & Mhaimeed, M. S. Electronic structure, photovoltaic and absorption properties of designed photo-efficient new organic dyes with D-π-A framework. Int. J. Nucl. Energy Sci. Technol. 14, 61 (2020).

Rani, M. et al. Engineering of A-π-D-π-A system based non-fullerene acceptors to enhance the photovoltaic properties of organic solar cells; a DFT approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 801, 139750 (2022).

Rukhsar, J. et al. A DFT approach toward designing selenophene-based unfused small molecule acceptors by end‐capped modification for improving the photovoltaic performance of organic solar cells. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 37, e4587 (2024).

Hou, J., Inganäs, O., Friend, R. H. & Gao, F. Organic solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Mater. 17, 119–128 (2018).

Yan, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 1–19 (2018).

Tripathi, A., Kozaderov, O., Shikhaliev, K. & Prabhakar, C. A DFT study on optical, electronic, and charge transport properties of star-shaped benzo[1,2‐b:3,4‐b′:5,6‐b″]trithiophene oligomers. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 33, e4037 (2020).

Tamai, Y. Charge generation in organic solar cells: journey toward 20% power conversion efficiency: special issue: emerging investigators. Aggregate 3, e280 (2022).

Zhang, J., Zhu, L. & Wei, Z. Toward over 15% power conversion efficiency for organic solar cells: current status and perspectives. Small Methods. 1, 1700258 (2017).

Upama, M. B., Mahmud, M. A., Conibeer, G. & Uddin, A. Trendsetters in High-Efficiency organic solar cells: toward 20% power conversion efficiency. Sol RRL. 4, 1900342 (2020).

Chang, S. L. et al. Isomerically pure Benzothiophene-Incorporated acceptor: achieving improved Voc and Jsc of nonfullerene organic solar cells via end group manipulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 33179–33187 (2019).

Du, S. et al. Nonfullerene acceptors from Thieno [3, 2-b] thiophene-fused naphthalene donor core with six-member-ring connection for efficient organic solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 185, 108892 (2021).

Frisch, M., Clemente, F. & Gaussian 09, revision a. 01, mj frisch, gw trucks, hb schlegel, ge scuseria, ma robb, jr cheeseman, g. Scalmani V Barone B Mennucci GA Petersson H Nakatsuji M Caricato X Li HP Hratchian AF Izmaylov J Bloino G Zhe 20–44 (2009).

Dennington, R., Keith, T. A. & Millam, J. M. GaussView, version 6.0. 16. Semichem Inc Shawnee Mission KS (2016).

Andersson, M. P. & Uvdal, P. New scale factors for harmonic vibrational frequencies using the B3LYP density functional method with the Triple-ζ basis set 6-311 + G(d,p). J. Phys. Chem. A. 109, 2937–2941 (2005).

Yanai, T., Tew, D. P. & Handy, N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 393, 51–57 (2004).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: the m PW and m PW1PW models. J. Chem. Phys. 108, 664–675 (1998).

O’boyle, N. M., Tenderholt, A. L. & Langner, K. M. cclib: A library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 839–845 (2008).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Schmidt, H. et al. Dorsal root ganglion axon bifurcation tolerates increased Cyclic GMP levels: the role of phosphodiesterase 2A and scavenger receptor Npr3. Eur. J. Neurosci. 44, 2991–3000 (2016).

Hanwell, M. D. et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4, 17 (2012).

Zhurko, G. A. & Zhurko, D. A. ChemCraft, version 1.6. http://www.chemcraftprog.com (2009).

Khalid, M. et al. Role of extended end-capped acceptors in non-fullerene based compounds towards photovoltaic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 448, 115292 (2024).

Abdelaziz, B., Chérif, I., Gassoumi, B., Patanè, S. & Ayachi, S. Linear and nonlinear optical responses of Nitrobenzofurazan-Sulfide derivatives: DFT-QTAIM investigation on twisted intramolecular charge transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A. 127, 9895–9910 (2023).

Iftikhar, T., Ali, U. & Shoaib, M. Theoretical study of Α, Β unsaturated carbonyl thiophene derivatives to investigate optoelectronic properties toward organic photovoltaics. J. Mol. Model. 26, 1–8 (2020).

Khalid, M. et al. Theoretical approach towards Benzodithiophene-Based chromophores with extended acceptors for prediction of efficient nonlinear optical behaviour. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 339–359 (2024).

Abdelaziz, B. et al. Molecular engineering of D-π-A-type structures based on Nitrobenzofurazan (NBD) derivatives for both organic solar cells and nonlinear optical response. J. Mol. Liq. 395, 123934 (2024).

Abdali, S. A., AL-Temimei, F. A. & Al-Abbas, S. S. Computational design of D-π-A dyes for improved photovoltaic performance: a DFT approach. J. Comput. Electron. 23, 209–223 (2024).

Abdali, S. A., AL-Temimei, F. A. & Al-Abbas, S. S. Design a new D-π-A formation dyes as Dye-sensitized solar cells applications/ a DFT and TD-DFT study. J. Fluoresc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10895-023-03311-2 (2023).

Mustafa, G. et al. Quantum chemical exploration of A – Π 1 –D 1 –π 2 –D 2 -Type compounds for the exploration of chemical reactivity, optoelectronic, and Third-order nonlinear optical properties. ACS Omega. 8, 22673–22683 (2023).

Chérif, I. et al. Computational studies on optoelectronic and nonlinear optical properties of para-substituted Nitrobenzofurazan compound. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 106133 (2023).

Raissi, H. et al. Structure–property relationships in para-substituted nitrobenzofurazans: electrochemical, optical, and theoretical analysis. Chem. Pap. 76, 4059–4080 (2022).

Zhan, C. G., Nichols, J. A., Dixon, D. A., Ionization potential, electron affinity, electronegativity, hardness, and Electron excitation energy: molecular properties from density functional theory orbital energies. J. Phys. Chem. A. 107, 4184–4195 (2003).

Serdaroğlu, G. & Mustafa, E. A computational study predicting the chemical reactivity behavior of 1-substituted 9-ethyl-βCCM derivatives: DFT-Based quantum chemical descriptors. Turk. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2, 1–11 (2018).

Tahir, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization and NLO properties of 1, 4-phenylenediamine-based schiff bases: a combined theoretical and experimental approach. RSC Adv. 14, 4221–4229 (2024).

Chérif, I. et al. Photophysical and nonlinear optical properties of para-substituted Nitrobenzofurazan: A comprehensive DFT investigation. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem. 443, 114850 (2023).

Parr, R. G., Donnelly, R. A., Levy, M. & Palke, W. E. Electronegativity: the density functional viewpoint. J. Chem. Phys. 68, 3801–3807 (1978).

Ferdowsi, P. et al. Molecular design of efficient organic D–A–π–A dye featuring triphenylamine as donor fragment for application in dye-Sensitized solar cells. ChemSusChem 11, 494–502 (2018).

Lin, Y. et al. An electron acceptor challenging fullerenes for efficient polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 27, 1170–1174 (2015).

Al-Temimei, F. A., Alasadi, L. A. & Alaboodi, A. S. DFT study of new donor-π-acceptor materials based on thieno [2, 3-b] indole candidate for organic solar cells application. Materials Science Forum 1002, 221–229 (2020).

Khalid, M., Shafiq, I., Imran, M., Jawaria, R. & Braga, A. A. C. V-shaped naphthalene diimide-based chromophores: first theoretical framework for designing high efficacy of organic solar cells. Synth. Met. 303, 117548 (2024).

Siddique, S. A. et al. Discovery of versatile bat-shaped acceptor materials for high‐performance organic solar cells: A DFT approach. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 13393–13408 (2022).

Tang, S. & Zhang, J. Design of donors with broad absorption regions and suitable frontier molecular orbitals to match typical acceptors via substitution on oligo(thienylenevinylene) toward solar cells. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 1353–1363 (2012).

Doust Mohammadi, M. et al. Increasing the photovoltaic power of the organic solar cells by structural modification of the R-P2F-Based materials. J. Mol. Model. 29, 237 (2023).

Zheng, Z. et al. PBDB-T and its derivatives: A family of polymer donors enables over 17% efficiency in organic photovoltaics. Mater. Today. 35, 115–130 (2020).

Qi, B. & Wang, J. Open-circuit voltage in organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 24315–24325 (2012).

Hussain, R. et al. Enhancement in photovoltaic properties of N, N -diethylaniline based donor materials by bridging core modifications for efficient solar cells. ChemistrySelect 5, 5022–5034 (2020).

AL-Temimei, F. A. Design high—efficiency organic dyes based on fluorescein toward dye—sensitized solar cells: a DFT/TD-DFT study. Opt. Quantum Electron. 54, 600 (2022).

Qi, B. & Wang, J. Fill factor in organic solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 8972–8982 (2013).

Zanlorenzi, C. & Akcelrud, L. Theoretical studies for forecasting the power conversion efficiencies of polymer-based organic photovoltaic cells. J. Polym. Sci. Part. B Polym. Phys. 55, 919–927 (2017).

AL-Temimei, F. A., Abbas, F. S. & Alaboodi, A. S. New π-conjugated materials based on thienopyrazine as organic dye sensitizers for organic photovoltaic device applications. J. Phys. 1294, 022003 (2019).

Khan, M. U., Anwar, A., Hassan, A. U., Alshehri, S. M. & Sohail, A. DFT simulations of photovoltaic parameters of dye-sensitized solar cells with new efficient sensitizer of indolo[3, 2‐b]carbazole complexes. Energy Sci. Eng. 12, 3681–3703 (2024).

Mishra, A., Fischer, M. K. R. & Bäuerle, P. Metal-Free organic dyes for Dye‐Sensitized solar cells: from structure: property relationships to design rules. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2474–2499 (2009).

UrRehman, S. et al. DFT analysis of different substitutions on optoelectronic properties of carbazole-based small acceptor materials for organic photovoltaics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 140, 106381 (2022).

Mehboob, M. Y. et al. Quantum chemical design of near-infrared sensitive fused ring electron acceptors containing Selenophene as π‐bridge for high‐performance organic solar cells. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 34, e4204 (2021).

Wang, W. C. et al. A strategy of designing near-infrared porphyrin-based non-fullerene acceptors for panchromatic organic solar cells. Org. Electron. 86, 105899 (2020).

Dkhissi, A. Excitons in organic semiconductors. Synth. Met. 161, 1441–1443 (2011).

Liu, Z., Wang, X., Lu, T., Yuan, A. & Yan, X. Potential optical molecular switch: lithium@ cyclo [18] carbon complex transforming between two stable configurations. Carbon 187, 78–85 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-645), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. K.C. acknowledges the support from the doctoral research fund of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Muhammad Adnan Asghar: Conceptualization; methodology; supervision. Iqra Shafiq: Data curation; formal analysis. Sadia Jamal: Methodology; software; project administration. Khalid Abdullah Alrashidi: Resources; software; supervision. Ke Chen: Conceptualization; resources; project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asghar, M.A., Shafiq, I., Jamal, S. et al. Molecular engineering with benzothiophene based bracing units to improve the photovoltaic properties of the naphthalene core based chromophores. Sci Rep 15, 26872 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02101-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02101-z