Abstract

The melanoidins produced by the Maillard reaction give foods a golden, brown or black color and release aromatic compounds. Investigating the molecular structure and pyrolysis characteristics of melanoidins provides insight into improving food quality. Seven hydrosoluble colored fractions were isolated from three melanoidins (glycine/glucose (Gly–Glc), proline/glucose (Pro–Glc), and phenylalanine/glucose (Phe–Glc)) using size exclusion and C18 chromatography. Fractions with lower molecular weights (Mw: 5958– 20,106 Da) exhibited deeper colors (browning index: 0.783–3.044). For melanoidins derived from polar amino acids (glycine), low-polarity fractions contributed more to color, while for those from non-polar amino acids (proline), high-polarity fractions were more significant. Mass spectrometry revealed consistent polymerization patterns involving glyoxylic acid and glyoxal across fractions (mass-to-charge differences of 74 m/z and 58 m/z). NMR analysis indicated that Pro–Glc fractions contained more glucose skeletons, whereas Phe–Glc fractions exhibited benzene-ring features. After pyrolysis, furans, pyrroles, and cyclopentenones were major volatiles in Gly–Glc fractions, with pyrroles and DDMP dominating Pro–Glc fractions, and phenyl-containing compounds prevalent in Phe–Glc fractions. These findings suggest amino acids influence both melanoidin structure and glucose-derived skeletons, providing a foundation for controlling color and aroma formation during processing such as baked foods, roasted meats, coffee, dairy products and fermented foods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Maillard reaction is an important chemical reaction in the food industry, influencing the color and aroma of baked, grilled, roasted, and barbecued foods. It involves a complex series of cascade reactions between the amino group and the carbonyl group, forming melanoidins (brown polymers) that contribute to flavor and color1. Color and aroma are crucial sensory attributes that affect food quality and consumer preferences2. Melanoidins impart golden, brown or black colors to food and release aromatic compounds upon pyrolysis, enhancing flavor3. For example, melanoidins contribute to the deep brown color of roasted coffee beans and the golden-brown crust of baked bread, while also enhancing their respective aromatic profiles with roasted and caramel-like notes in coffee and toasty, malty nuances in bread4. Therefore, in order to learn more about the influence of fractions from melanoidins on color and flavor, melanoidins should be separated more finely, and the molecular characteristics and pyrolysis flavor characteristics of the separated fractions should be further studied.

Previous studies find that melanoidins are high-molecular-weight, nitrogen-containing polymers, and their molecular structure remains partially elucidated due to their heterogeneous and polymeric nature5. Spectroscopic analyses, including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry, suggest that melanoidins contain pyrrole, furan, and pyridine rings, as well as conjugated double bonds, contributing to their brown coloration and antioxidant properties6. In addition, structural studies indicate that melanoidins may exhibit polysaccharide-like backbones with covalently bound phenolic and protein-derived moieties7. Despite advancements in analytical techniques, the precise molecular arrangement of melanoidins remains a subject of ongoing research.

Thermal degradation and solid phase microextraction–gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (SPME–GC–MS) determination indicated that the key aroma compounds of melanoidins in coffee, tomato sauce and bread crust were 1,3-dioxolanes, pyrroles, furans, pyrazines, carbonyl compounds, phenols, pyridines and thiophenes3. SPME–GC–MS analysis of the nondialyzable and nonsoluble standard melanoidins from l-(+)-ascorbic acid/glycine, glucose/glycine and glucose/glutamic acid models revealed the formation furans, some oxazoles, pyrroles, pyridines, carbonyl compounds and pyrazines5. Besides, pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass (Py–GC–MS) analysis of the melanoidins in black garlic with high hydrostatic pressure showed the generation of aldehydes, ketones and heterocyclic substances8. Furthermore, our previous study found that pyrroles, furans, pyran, cyclopentenes, indole and phenyl-containing compounds were major pyrolytic volatiles from the hydrosoluble colored fractions of melanoidins of the Maillard reaction models (glucose/glycine, glucose/proline and glucose/phenylalanine)9. Whereas, the hydrosoluble colored fractions were separated using Sephadex LH-20 Gel according to molecular weight difference, and their molecular structures and detailed properties remain underexplored. Sephadex LH-20 Gel separates samples according to molecular weight difference, and the separated fractions are mixtures containing a certain molecular range. In the application of separation, C18 chromatography column is often used to further isolate the separated fraction to obtain relatively pure components10. The C18 column is based on the polarity difference of the compound to complete compound isolation, the purity of the isolated fraction is high, and even a single compound can be obtained.

In this study, the melanoidins produced by three Maillard reaction models were separated by C18 column to obtain hydrosoluble colored fractions. The color, molecular structure and pyrolytic volatile characteristics of the isolated fractions were analyzed to better understand the Maillard reaction’s impact on food color and flavor in processing.

Material and methods

Chemical material

l-Glycine (Gly), l-proline (Pro), l-phenylalanine (Phe) and glucose (Glc) were sourced from Solarbio Science & Technology. (Beijing, China). Styrallyl propionate (97%) was supplied by Macklin Biochemical Technology (Shanghai, China). The n-alkane standard solution (C7 ~ C30, ≥ 97%, 1000 μg/mL) was procured from Supelco (49451-U, Merck KgaA, Ballefonte, PA, USA). Potassium bromide (KBr, spectroscopic grade) was provided by Siyou Fine Chemicals (Tianjin, China). Polyethylene glycol (PEG) standard was obtained from Agilent (CA, USA). Sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4) and sodium nitrate (NaNO3) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). All reagents were analytical grades.

Preparation of hydrosoluble colored fractions from three melanoidins

The preparation of melanoidins was conducted following a protocol from EU COST Action 919 methodology11. Glucose (18.0 g) and amino acids (l-phenylalanine (18.1 g), l-proline (11.52 g) and l-glycine (7.5 g)) were separately dissolved in deionized water (50 mL) at a molar ratio of 1:1. Three resulting solutions were lyophilized in a freeze-dryer (SCIENTZ-10N/A, Scientz Biotechnology, Ningbo, China). Three freeze-dried samples were heated (125 °C) for 2 h using a preheated oven (Lichen Instrument Technology, Shanghai, China) and subsequently cooled to ambient temperature (20 °C) in a desiccator.

Initially, three melanoidins samples were fractionated using a LC-52 medium-pressure chromatographic system (SEP Technology, Beijing, China) paired with Sephadex LH-20 Gel column (50 mm × 400 mm, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA). Elution conditions are as follows: loading quantity: 2 g; eluent: deionized water; flow rate: 1 mL/min; detection wavelength: 280 nm. For collecting a primary separated fraction, the eluent represented by a single elution peak in the chromatogram was collected, vacuum-concentrated at 30 °C and subsequently lyophilized.

For collecting the purer melanoidins fractions, the lyophilized primary fractions (0.2 g) were dissolved in 5% methanol (1 mL) and loaded onto a 15 mm × 920 mm Buchi Sepacore C-690 column filled with octadecylsilyl (C18) material (YMC-Triart-Prep C18-S, YMC, Japan). Separation was performed on an LC-52 system with a detection at 280 nm, using 50% methanol as the eluent at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The purified fractions were collected by vacuum concentration and lyophilization.

Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy, browning index (BI), and color density (CD) and color dilution factors

Samples (1 mg/mL) were dissolved in deionized water, and UV–Vis spectrums (200 ~ 800 nm) were recorded using a spectrophotometer (UV2400, Sunny Hengping Instrument, Shanghai, China). For browning index (BI) and color density (CD), samples (5 mg/mL) were analyzed by measuring absorbance at 420 nm and 520 nm, respectively8. Hue tendency was evaluated via the absorbance ratio (AR), calculated alongside BI and CD values as follows:

A420: the absorbance at 420 nm; A520: the absorbance at 520 nm.

Color dilution factor was detected using a triangle test (Hofmann1). The sample was mixed with deionized water at a 1:1 ratio and progressively diluted until no visible color difference remained compared to a deionized water control. According to ISO 412012, the dilution number can be defined as the color dilution factor of each sample when the difference between the diluted sample solution and two controls can only be directly detected visually.

Color scale

Samples (1 mg/mL) were dissolved in deionized water, and transmittance (T%, wavelengths: 360 ~ 800 nm) was measured with a spectrophotometer. The calculations of L*, a* and b* values were executed using OriginPro software (Chromaticity Diagram function, v.2019b, OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Chroma (C*ab) and hue angle (h°) are calculated as following:

Relative molecular weights (RMWs) determination

RMWs of samples were analyzed using a Waters 1525 Binary HPLC system with a refractive index (RI) detector (2414, Waters, MA, USA) and a PL aquagel-OH MIXED 8 μm Column (Agilent, CA, USA). HPLC parameters are as follows: mobile phase: a solution containing 0.2 mol/L NaNO3 and 0.01 mol/L NaH2PO4 (pH = 7); flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; temperature: 30 °C. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) standards were used for the calibration curve. Number average molecular weight (Mn), weight average molecular weight (Mw), molecular weight of the highest peak (Mp) and polydispersity of sample were reported.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were obtained using an infrared spectrometer (IARffinity-1S, Persee Instrument, Beijing, China) according to the previous study6. Sample (1 mg) was mixed with potassium bromide (KBr, 100 mg), pressed to a pellet, and scanned from 4000 to 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 (32 scans). A KBr pellet was used as background reference.

Elemental analysis (EA)

Hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen contents were quantified using a Vario EL cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). High-purity oxygen and helium were used, with combustion at 1150 °C and reduction at 950 °C. Oxygen content (%) was calculated as the remainder after subtracting the percentages of the other three elements from 100%.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS)

MALDI-TOF-MS analysis was conducted using a mass spectrometer (autoflex speed MALDI-TOF, Bruker, Switzerland) according to the previous study6. The linear mode was used to detect signals from 400 to 100 m/z. Trans-2-[3-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-2-methyl-2-propenylidene]malonitrile (DCTB) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) was used as matrix and solvent, respectively.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

Sample (20 mg) was dissolved in D2O for 1H and 13C, HSQC NMR analyses using an NMR spectrophotometer (AVANCE III HD 500 MHz, Bruker, Switzerland). The 1H spectrum determination parameters: observation frequency: 500 MHz; scanning times: 256; cycle delay time: 1 s. The 13C spectrum determination parameters: observation frequency: 125 MHz; scanning times: 2048; cycle delay time: 2 s.

Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py–GC–MS)

Py–GC–MS analysis was executed using a GC–MS system (7890A Gas Chromatograph, 5975C inert XL MSD, Agilent, CA, USA) equipped with a DB-5 ms column (60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Sample (10 mg) and internal standard (styrallyl propionate) were dissolved in 5% ethanol (100 μL), and the solution (1 μL) was placed on quartz wool in a pyrolysis tube. Pyrolysis was conducted at 300, 600 and 900 °C for 30 s with a pyrolyzer (CDS 6200, CDS Analytical LLC, Pennsylvania, USA), respectively. The pyrolytic fractions were captured in a cryotrap at − 60 °C and released at 280 °C for 5 min.

GC system parameters are as follows: carrier gas: helium; flow rate: 1 mL/min; split ratio: 1: 20; temperature program: starting at 50 °C, then raising to 280 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and holding for 20 min. MS parameters are as follows: ion source mode: electron ionization (EI); ion source temperature: 230 °C; quadrupole temperature: 150 °C; mass scan range: 33–450 m/z.

Pyrolytic products were identified by comparing their mass spectrum and the retention index (RI) with data from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library (https://chemdata.nist.gov/). RI values were calculated using retention times of n-alkane (C7 to C30) external references and volatile compounds under the identical conditions. The relative content of each pyrolytic fraction was calculated by comparing its peak area to that of the internal standard.

Statistical analysis

All determinations were executed in triplicate and presented as means ± standard deviations. Variance analysis (one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range tests, P < 0.05) was performed using SPSS Statistics R26.0.0.0I (SPSS, BM, Armonk, State of New York, USA). Principal component analysis (PCA) and plots were created using OriginPro v.2019b (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Results and discussion

Isolation of hydrosoluble colored fractions

Firstly, three melanoidins were prepared from three Maillard reaction models (glycine/glucose: Gly–Glc; proline/glucose: Pro–Glc; phenylalanine/glucose: Phe–Glc), and four primary isolated fractions (Gly–Glc P1 (yield: 38.41%), Gly–Glc P2 (yield: 44.23%), Pro–Glc P1 (yield: 95.72%) and Phe–Glc P1 (yield: 85.73%)) were separated using LH-20 gel columns. These primary isolated fractions were separated using C18 chromatographic columns, with elution fractions designated based on their sequential elution (Supplementary Material Fig. S1). As can be seen in Table 1, seven secondary isolated fractions were collected for subsequent analysis: two fractions (Gly–Glc P1-1 (13.48% yield to Gly–Glc P1) and Gly–Glc P1-2 (21.71% yield to Gly–Glc P1)) from Gly–Glc P1 fraction, two fractions (Gly–Glc P2-1 (13.76% yield to Gly–Glc P2) and Gly–Glc P2-2 (54.74% yield to Gly–Glc P2)) from Gly–Glc P2 fraction, two fractions (Pro–Glc P1-1 (51.82% yield to Pro–Glc P1) and Pro–Glc P1-2 (12.24% yield to Pro–Glc P1)) from Pro–Glc P1 fraction, and one fraction (Phe–Glc P1-1 (66.01% yield to Phe–Glc P1)) from Phe–Glc P1 fraction.

Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrums

The spectrums of seven fractions (Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-1, Gly–Glc P2-2, Pro–Glc P1-1, Pro–Glc P1-2 and Phe–Glc P1-1) are shown in Fig. 1. A pronounced absorption band near 290 nm was observed in the spectrums of the Gly–Glc and Pro–Glc fractions, potentially attributable to the presence of intermediate products or heterocyclic structures within the melanoidins’ carbon skeleton13. The Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction had a significant absorbance peak around 260 nm, which might originate from the phenyl ring conjugated system in melanoidins from phenylalanine/glucose model14.

UV–Vis spectrums of seven hydrosoluble colored fractions. (a) spectrums of samples from glucose/glycine model; (b) spectrums of samples from glucose/proline model; (c) spectrums of samples from glucose/phenylalanine model. Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Gly–Glc P2-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (glycine/glucose model), respectively; Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the mela-noidins (proline/glucose model), respectively; Phe–Glc P1-1 represents the fraction eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (phenylalanine/glucose model).

Octadecylsilyl (C18) chromatography column isolates different fractions based on the difference of compound polarity. Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions had higher polarity than Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions, respectively. The results indicated that the UV–Vis absorbance of the Gly–Glc fraction with high polarity was weaker than that of the Gly–Glc fraction with low polarity. This may be due to the fact that the high-polarity fractions of Gly–Glc reaction products are more likely to form hydrogen bonds or other strong intermolecular interactions, reducing molecular conjugation, affecting their electronic transitions, and giving them lower absorbance15. Conversely, the high polarity Pro–Glc fraction demonstrated enhanced UV–Vis absorbance relative to the low polarity fraction. It indicates that in the Pro-Gly reaction products, the high-polarity fractions have stronger conjugation and stronger aromatic system, which makes them have higher UV–Vis absorbance than the low-polarity fractions16. Furthermore, these observations could be attributed to the varying polar characteristics of the R groups associated with the respective amino acids.

Color properties

The results of color characteristics in CIE (International Commission on illumination) color system are closer to the results of human visual perception of color in solution than absorbance measurement. Color attributes (AR, BI, CD, L*, a*, b*, color dilution factors, h° and C*ab) of seven fractions are recorded in Table 1, and the photos of these fraction solutions are shown in Supplementary Material Fig. S2. Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction had higher a* values and lower L*, b*, C*ab and h° values than Gly–Glc P1-1 fraction, which showed that Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction had a more red feature than Gly–Glc P1-1 fraction. This contrast in color intensity and hue may be attributed to the differences in the molecular structure and the extent of conjugation within the melanoidins formed from glycine and glucose2.

Besides, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions had higher h° and L* values and lower C*ab, a* and b* values than Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions, respectively, which suggested that Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions had a darker color, more red tonality and higher saturation than Gly–Glc P2-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions. Moreover, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions had higher BI, CD values and color dilution factors than Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions, which indicated that Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions had higher color contribution in their respective models, respectively. The findings might conclude that the low polarity fractions derived from the melanoidins of polar amino acid (glycine) and glucose reactions had a more pronounced effect on melanoidin coloration, whereas the high polarity fractions from non-polar amino acid (proline) and glucose reactions played a greater role in melanoidin color intensity.

The a* value of the Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction suggested that it had a green character. Moreover, Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction was the main fraction of melanoidin (phenylalanine/glucose) separated by LH-20 gel column and C18 column, which represented the color characteristics of this kind of melanoidin. Compared to the previously reported Phe–Glc P1 fraction with its subdued red and pronounced yellow hue9, Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction isolated in the present study exhibited a weaker greenish-yellow color. These results demonstrated that Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2, Pro–Glc P1-1 and Phe–Glc P1-1 fractions had important contributions to overall color in their reaction model, respectively.

Relative molecular weight (RMW)

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) can be used to analyze the RMWs and polydispersity of melanoidins. As can be seen in Table 1, Gly–Glc P1-1 fraction had significantly higher values of Mn (6371 Da), Mw (16,477 Da), Mp (15,879 Da) and polydispersity (2.59) than Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction. Moreover, Gly–Glc P2-1 fraction had significantly higher values of Mn (4755 Da), Mw (10,148 Da) and Mp (9949 Da) than Gly–Glc P2-2 fraction. These results suggested that the main colored fractions of melanoidins had lower RMW and molecular weight distribution in glycine/glucose model.

Pro–Glc P1-2 fraction had significantly higher Mn (9173 Da) and lower polydispersity (2.19) than Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction. The result indicated that the main colored fraction of melanoidins had lower RMW and higher molecular weight distribution in proline/glucose model. Besides, the values of Mn (5265 Da), Mw (12,436 Da) and Mp (11,318 Da) of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction were in the middle level of all tested fractions. The results showed that the colored fractions with low average molecular weight had deep color per unit concentration and contributed more to the overall color of melanoidins.

Combined with the retention characteristics of C18 fillers, the results demonstrated that the polarities of two fractions with low RMW in the melanoidins of glycine/glucose model were lower. However, a different phenomenon was observed in the melanoidins of proline/glucose model, and the polarity of the fractions with low RMW were higher. Compared with the data reported in previous studies9, it was found that the RMW characteristics of melanoidin fractions after C18 column separation were significantly different from those before separation. It can be inferred that the Maillard reaction could produce a series of colored substances with similar polarity but large molecular weight differences17.

Elemental analysis

Comparative analysis of elemental composition in melanoidins can provide basic information for investigating the characteristics of melanoidins. As detailed in Table 2, seven fractions contained lower hydrogen and oxygen contents than the theoretical contents of the corresponding elements, and they had higher carbon contents than theorized. The changes in the contents of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen elements in the melanoidins may be caused by the formation of H2O and CO2 during reaction18. Notably, nitrogen content exceeded expectations in fractions from glycine/glucose and phenylalanine/glucose models, which is consistent with the increase in nitrogen in melanoidins found in previous studies through the Maillard reaction19.

Besides, the N/C ratios of Gly–Glc P2-1, Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions were lower than the theoretical values, respectively. It could be inferred that Gly–Glc P2-1 fraction and two fractions from proline/glucose model had more glucose fragments. However, the N/C ratio of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction was higher than the theoretical value, which indicated that Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction contained more amino acid fragments.

Compared with the fractions collected before C18 column separation in the previous study9, the contents of hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon in Gly–Glc P1-1 and Gly–Glc P1-2 fractions decreased and oxygen content increased, and the contents of hydrogen and nitrogen in Gly–Glc P2-1, Gly–Glc P2-2, Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions decreased, while the contents of carbon and oxygen increased. The oxygen content of glucose group is higher than that of amino acid group . The increase of oxygen content indicated that these fractions separated from glycine/glucose and proline/glucose models contained more structures derived from glucose groups.

FTIR spectrums

FTIR spectroscopy can be used to indicate the properties of the chemical bonds of melanoidins20. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the IR spectrums of seven fractions contained a band (3600–3200 cm−1), which was assigned to OH stretching modes. It suggests that all seven fractions contain hydroxyl structures and have hydrogen bonds, which makes the fractions exhibit polarity and easily form polymers6.

FTIR spectrums of seven hydrosoluble colored fractions. Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Gly–Glc P2-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (glycine/glucose model), respectively; Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (proline/glucose model), respectively; Phe–Glc P1-1 represents the fraction eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (phenylalanine/glucose model).

The CH stretching bands in CH3 and CH2 were observed at around 2931 cm−117. The shoulder-like band around 1755 cm−1 was characterized by C=O stretching mode or COOH, which indicated that the melanoidin contained oxidized carbonyl structures6. The presence of these functional groups supports the hypothesis that melanoidins have a highly conjugated and oxygen-rich polymeric structure. The strong stretching band at around 1630 cm−1 could be related to C=C, C=O stretching vibration (amide I) or C–N (amide II) in all fractions20. Moreover, a broad band (1430–1365 cm−1) was attributed to CH3 stretching mode19.

In Pro–Glc P1-1, Pro–Glc P1-2 and Phe–Glc P1-1 fractions, the band (1454 cm−1) was assigned to the stretching of CH2, indicating that the straight and branched chains in Phe–Glc P1-1, Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions’ skeletons were longer than those of four Gly–Glc fractions. Meanwhile, a shoulder-like band (1505 cm−1) suggested that the final structure of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction contained a high degree of conjugation, possibly due to aromatic or heterocyclic moieties formed in the later stages of the Maillard reaction. In addition, a band (1240 cm−1) formed by C–N stretching in six fractions from glycine/glucose model and proline/glucose model, demonstrating that more C–N groups appeared in the skeleton of these six fractions7.

The band (1060 cm−1) is caused by the stretching of C–O–C and C–O, which is a characteristic band of the melanoidin skeleton containing carbohydrate side chains21. The absorptions of Gly–Glc P2-2 and Pro–Glc P1-2 fractions were stronger than those of Gly–Glc P2-1 and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions, respectively, suggesting a higher prevalence of oxygen-containing functional groups. Combined with the results of elemental analysis, it was an indicator that the increase of oxygen element content after C18 column separation might be caused by the increase of C–O–C and C–O structures. This suggested potential differences in the degree of carbohydrate incorporation or oxidative modifications among these fractions, which may further influence their structural complexity and functional properties.

Moreover, the FTIR spectra of the seven fractions exhibited a redshift, which may be attributed to changes in the electronic environment of functional groups due to progressive modifications during the Maillard reaction. This shift suggests the incorporation of diverse nitrogen-containing and oxygen-containing functional groups into the melanoidin backbone, such as carbonyl (C=O) and pyrrole- or pyrazine-like (C–N) structures, which contribute to the conjugated polymeric nature of melanoidins. Furthermore, the similarity in IR spectra among different fractions indicates that the core skeleton structures of the chromogenic substances formed during the Maillard reaction are likely to share common structural motifs, despite possible variations in side-chain composition and degree of polymerization.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MAIDI-TOF–MS)

MALDI-TOF-MS is a powerful technique for analyzing the molecular structures of melanoidin fractions, providing insight into their polymerization patterns and potential building blocks. As shown in Fig. 3, relatively similar peaks existed in the range of 400–750 m/z among seven fractions. This result is consistent with the infrared spectroscopic results, and seven fractions contain structurally similar skeleton from glucose derivatives. In addition, the difference of the spectrums between different fractions in the same model might be due to the different polarity of the fractions and the different content distribution. Moreover, a peak with a mass-to-charge ratio difference of 74 (489 m/z and 563 m/z, 518 m/z and 592 m/z, 592 m/z and 666 m/z, 551 m/z and 625 m/z) was observed, indicating that glyoxylic acid may be a key participant in the formation of colored melanoidin fractions. This recurring mass shift is consistent with known glyoxylic acid polymerization patterns, further supporting its role in melanoidin growth and structural diversification.

MAIDI-TOF–MS of seven hydrosoluble colored fractions. Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Gly–Glc P2-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (glycine/glucose model), respectively; Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the mela-noidins (proline/glucose model), respectively; Phe–Glc P1-1 represents the fraction eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (phenylalanine/glucose model).

In the Gly–Glc P2-2 fraction, a set of mass-to-charge ratio differing by 58 units (899, 957, 1015, 1074, 1132, 1190, 1249, 1307, 1366, 1424 m/z) suggested a consistent structural backbone from the Maillard reaction products (glycine/glucose). This uniformity likely stemmed from low molecular weight intermediates, such as glyoxal, which was incapable of enolation but could engage in polymerization through aldol condensation with enols, leading to the formation of polymeric melanoidins6. Such polymerization behavior indicates that glyoxal plays a fundamental role in melanoidin formation, facilitating cross-linking and molecular assembly through condensation with dicarbonyl aldehydes.

The previous studies showed that the melanoidins had a series of peaks with a mass difference of 74 m/z between 2500 and 5500 m/z and a mass difference of 58 m/z between 1500 and 2500 m/z, respectively, indicating distinct polymerization pathways for glyoxylic acid and glyoxal-derived structures6. In this study, the presence of the mass-to-charge ratio difference (74 m/z and 58 m/z) in the same Maillard reaction model suggested that these two polymerization pathways may occur simultaneously, contributing to the structural complexity of the melanoidin network. This simultaneous polymerization mechanism highlights the dynamic interplay between different reactive intermediates, offering new insight into the hierarchical assembly of melanoidins at the molecular level.

NMR

One-dimensional NMR spectrum

In this study, the flavor characteristics of the high color contribution fractions in the Maillard reaction products were a primary focus. Therefore, the fractions with large color contribution degree and mass proportion in the isolated Maillard reaction product (Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2, Pro–Glc P1-1 and Phe–Glc P1-1) were selected for NMR analysis and Py–GC–MS analysis. NMR is a technique for obtaining molecular structure information of melanoidin components. The 1H NMR spectrums of four fractions are shown in Supplementary Material Fig. S3, Gly–Glc P1-2 and Gly–Glc P2-2 fractions showed a chemical shift below 3.25 ppm, indicating that the formation of saturated hydrocarbons not associated with strong electron-withdrawing groups22. Notably, the 0.14 ppm signal in Gly–Glc P2-2 (Supplementary Material Fig. S3B) suggests terminal methyl or methylene groups, indicative of aliphatic chain terminations, which could arise from glucose-derived degradation products or cross-linking structures. Besides, the spectrum of Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction (Supplementary Material Fig. S3C) had two heightened signals between 1.0–1.5 ppm and 1.5–3.0 ppm, attributable to the saturated hydrocarbon structure of proline/glucose model. Additionally, the 6.3–6.4 ppm region observed in three fractions (Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2, and Pro–Glc P1-1) corresponded to olefinic protons, suggesting partial unsaturation within the conjugated melanoidin network. The signals between 7.0 and 8.0 ppm were attributed to hydrogens in aromatic and heterocyclic systems, indicative of conjugated π-electron systems that contribute to color formation. The 7.14 ppm peak in Gly–Glc P2-2 was particularly noteworthy, as it aligned with pyridine-like heterocyclic structures, further supported by the 8.0–8.8 ppm range, which was characteristic of protonated pyridine or other nitrogen-containing aromatic systems. The distinct 9.3 ppm resonance in Gly–Glc P2-2 suggested the presence of carboxyl functionalities, possibly arising from oxidation or incorporation of acidic intermediates23. In contrast, Phe–Glc P1-1 exhibited strong signals in the 3.0–4.2 ppm range, likely corresponding to hydroxylated and oxygenated aliphatic moieties, whereas the peaks between 7.2 and 7.5 ppm align with aromatic protons, confirming benzene ring retention within phenylalanine-derived structures. The weaker 4.2–4.7 ppm signals may originate from substituted benzene derivatives formed through Maillard reaction intermediates, suggesting structural modifications in the aromatic framework.

The 13C NMR spectrums (Supplementary Material Fig. S4) of Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2, and Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions were weak, with a notable peak at 89.66 ppm in Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction, indicating the presence of strongly electron-withdrawing groups, possibly related to oxygenated or heterocyclic carbon structures22. As are shown in Supplementary Material Fig. S5, the signal distribution between 50 and 105 ppm in Phe–Glc P1-1 implied new structural formations in colored fractions, supporting the idea that Maillard reaction intermediates undergo further condensation and rearrangement. Furthermore, compared with the predictive 13C spectrum of phenylalanine, the shift near 175 ppm indicated carboxyl group involvement in reaction pathways, likely leading to decarboxylation or incorporation into polymeric melanoidins. Notably, the persistence of signals between 125 and 135 ppm, corresponding to benzene carbons, suggested that while modifications occur, the core aromatic system remained intact, consistent with prior studies on Maillard-derived phenylalanine derivatives.

Two-dimensional NMR spectrum

The HSQC diagrams of four isolated fractions are shown in Fig. 4. Region 1 in the HSQC plots (Fig. 4A–D) likely originated from methylene groups bonded to nitrogen (–CH2–N–) or oxygen (–CH2–O–)24. These signals indicated the presence of heteroatom-substituted aliphatic chains, likely arising from the incorporation of glucose-derived hydroxyl (–CH2–OH) and amine (–CH₂–NH) functionalities into the polymeric melanoidin structure. Region 2 in the HSQC (Fig. 4C) of Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction could stem from the methyl end group of an alkane chain (–C–CH3), primarily from glucose residues25. These signals were indicative of glucose-derived methylated structures, suggesting that this fraction contains a richer glucose-derived backbone than the other fractions. This observation is consistent with elemental analysis, which showed a higher proportion of oxygen, reinforcing the idea that glucose residues are more prevalent in the Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction’s melanoidin network.

HSQC NMR spectrums of four hydrosoluble colored fractions. Gly–Glc P1-2 and Gly–Glc P2-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the mela-noidins (glycine/glucose model), respectively; Pro–Glc P1-1 and Phe–Glc P1-1 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from two melanoidins (proline/glucose model or phenylalanine/glucose model), respectively.

Besides, in the HSQC (Fig. 4D) of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction, region 3 was attributed to methyl groups attached to nitrogen atom (-N-CH3). These signals suggested the presence of N-methylated structures, possibly arising from secondary amines or pyrrole-like moieties formed during Maillard reaction condensation processes. The presence of such structures supports the hypothesis that nitrogen-containing heterocycles are key components of the chromophoric system in this fraction, contributing to its color intensity and stability. Region 4 was indicative of a benzene ring (-C6H5), demonstrating that the Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction retained the aromatic backbone of phenylalanine25. The persistence of these signals suggested that while structural modifications occur, the benzene ring remains largely intact, contributing to the distinct chromophoric properties of this fraction. This observation aligns with previous findings that phenylalanine-derived Maillard reaction products incorporate aromatic functionalities into melanoidins, playing a crucial role in their optical properties.

Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py–GC–MS)

Py–GC–MS can be used to determine the volatile characteristic of hydrosoluble colored fractions from the Maillard reaction model9. As shown in Supplementary Material Table S1, four hydrosoluble colored fractions contained 71 kinds of pyrolytic products, which were divided in nine groups (33 phenyl-containing compounds, 14 pyrroles, 5 furans, 5 cyclopentenes, 4 pyridines, 3 pyrazines, 3 indoles, 2 pyrans and 2 imidazoles).

The main compounds contained in the pyrolytic products of two hydrosoluble colored fractions from the melanoidins (glycine/glucose model) were pyrroles (7 kinds in Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction; 9 kinds in Gly–Glc P2-2 fraction) and phenyl-containing compounds (6 kinds in Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction; 5 kinds in Gly–Glc P2-2 fraction). The relatively high content compounds in Gly–Glc P1-2 fraction were indene, styrene, 3-methyl-1H-pyrrole, 2,5-dimethyl-furan (DMF) and 4-cyclopentene-1,3-dione. Meanwhile, 3-methyl-1H-pyrrole, DMF, 2,3-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole, pyridine and 4-cyclopentene-1,3-dione were the main compounds in Gly–Glc P2-2 fraction.

Indene, with its benzene ring and cyclopentadiene structures, possessed a subtle aromatic flavor (odor threshold values: 0.013 mg/m3)26. 4-Cyclopentene-1,3-dione, a characteristic degradation product of glucose under thermal conditions, features an intense caramel aroma. In addition, simplistic pyrroles (3-methyl-1H-pyrrole and 2,3-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole), likely arising from the cyclization and dehydration of glucose-derived carbonyl intermediates in the presence of nitrogenous species, a process favored in glycine-containing systems. These nitrogenous heterocycles contribute warm-ethereal and sweet aromas to thermally processed foods. Furthermore, DMF is thought to be derived from glucose and exhibits a baked bread aroma27. Furan structures, including 5-methyl-2-furanmethanol and 5-hydroxymethyldihydrofuran-2-one, were identified, suggesting that furans were generated from carbohydrate-derived precursors incorporated into the melanoidin network 18. These results demonstrate that the glucose skeleton dominates the hydrosoluble colored fractions in melanoidins from the glycine/glucose model. Besides, styrene has an extremely penetrating odor, containing balsamic, sweet and almost floral aroma. Pyridine is formed from reactants such as aldol condensates, thermal degraded amino acids and phenylacetaldehyde, and it exhibits an unpleasant odor28.

In Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction, pyrroles predominated among the pyrolytic products at 900 °C, and 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4(H)-pyran-4-one (DDMP) was the most abundant (974% at 600 °C and 385% at 900 °C). It indicates that DDMP is integrated into the melanoidin structure or serves as a key reaction intermediate in chromophore formation. Previous studies have demonstrated that DDMP, formed via 2,3-enolization and oxidation of glucose-derived structures, undergoes further transformations to generate furan and pyran compounds29. Furthermore, the glucose to proline molar ratio significantly influences DDMP formation, which is characterized by a baked cereal aroma and a strong bitter taste30. Additionally, Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction was rich in 2-hydroxy-1-(1’-pyrrolidiyl)-1-buten-3-one and 1-acetyl-pyrrolidine, which contain proline’s signature structure. It suggests that melanoidin fractions derived from glucose and amino acids contain diverse pyrrole-based heterocycles, reflecting their polymeric and multifunctional nature3.

The pyrolytic products of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction mainly contained phenyl-containing compounds (31 kinds), such as phenylacetaldehyde, toluene, N-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinylidene)-2-benzothiazolamine and styrene. The previous study demonstrated that phenylacetaldehyde was derived mainly from phenylalanine and could also be produced through the degradation of styrene31. Phenylacetaldehyde has a rose-like, floral, berry, honey and pungent odor at low concentrations. Toluene, a simple phenyl-ringed molecule, imparts a sweet and benzene-like aroma post-pyrolysis32. Moreover, the distinct pyrolytic profile of Phe–Glc P1-1 fraction, as opposed to those from proline/glucose and glycine/glucose models, underscores the prevalence of phenyl structures in the melanoidin skeleton of the phenylalanine/glucose model. The presence of these thermally stable phenyl-based compounds suggests that the incorporation of phenylalanine-derived structures contributes to the optical and sensory properties of the final melanoidin matrix.

Compared with our previous study9, DMF was absent in the pyrolytic products of Pro–Glc P1-1 fraction, while 5-methyl-2-furanmethanol and 5-hydroxymethyldihydrofuran-2-one were detected. These compounds are structurally similar to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a known carbohydrate-derived intermediate that undergoes further thermal decomposition to yield furan derivatives. The presence of these furans in melanoidin pyrolysis products suggests that HMF and its derivatives are incorporated into the melanoidin matrix rather than existing as free intermediates. Additionally, the presence of glucose derivatives like DDMP in melanoidins’ pyrolysis products, particularly at 600 °C and 900 °C, indicates a consistent reaction pathway for glucose across models, suggesting their integration into melanoidins’ skeleton. Elemental analysis further implies a significant role for glucose derivatives in melanoidin formation, confirming the influence of amino acids in modulating melanoidin structure while maintaining a predominantly glucose-based skeleton.

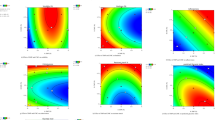

As shown in Fig. 5, the pyrolysis products of four fractions at 300 °C clustered towards the plot’s centroid, potentially owing to the minimal volatile yield at this temperature, resulting in indistinct separation. Principal Component 1 (PC1) exhibited a positive correlation with the pyrolysis products of the Phe–Glc P1-1 fractions at 600 °C and 900 °C, and a negative correlation with those of six other fractions at the same temperatures. This distinction in pyrolysis products between the Phe–Glc model and others might stem from the phenylalanine’s benzene ring structure, leading to an increased production of benzene-containing compounds. Conversely, the pyrolysis products of the Pro–Glc P1-1 fractions at 600 °C and 900 °C were negatively correlated to Principal Component 2 (PC2), while those of the Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-2, and Phe–Glc P1-1 fractions at these temperatures showed a positive correlation to PC2. These findings indicated that fractions derived from the three Maillard reaction models were dispersed across different regions of the plot, with similar types of fractions clustering at 600 °C and 900 °C pyrolysis temperatures. This suggested that fractions separated from the same model shared relative volatility similarities. Nevertheless, notable variations in volatiles among fractions from different models were evident, underscoring the substrate’s pivotal role in determining the volatile characteristics of Maillard reaction products.

PCA on the pyrolysis products of hydrosoluble colored fractions. Gly–Glc P1-1, Gly–Glc P1-2, Gly–Glc P2-1 and Gly–Glc P2-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (glycine/glucose model), respectively; Pro–Glc P1-1 and Pro–Glc P1-2 represent the fractions eluted using C18 separation from the mela-noidins (proline/glucose model), respectively; Phe–Glc P1-1 represents the fraction eluted using C18 separation from the melanoidins (phenylalanine/glucose model). Pyrolysis temperatures are 300 °C, 600 °C and 900 °C, respectively.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the polarity and amino acid type significantly influence the structural and chromophoric properties of hydrosoluble melanoidin fractions. In Maillard reaction systems, polar amino acids promote the formation of hydrosoluble colored fractions with stronger UV–Vis absorbance and greater color contribution, whereas non-polar amino acids lead to structurally distinct fractions with different physicochemical properties. The hydrosoluble fractions are composed of structurally related compounds with varying molecular weights, where low-molecular-weight fractions exhibit a higher color intensity. Mass spectrometry analysis reveals that the hydrosoluble colored fractions share a glyoxal-based polymeric backbone, with polymerization involving glyoxylic acid and glyoxal, forming a stable chromophoric system. Py–GC–MS results further confirm that the incorporation of HMF into melanoidins contributes to furan structures in the hydrosoluble fractions, whereas DDMP and other glucose-derived compounds are intrinsic components of the melanoidin skeleton rather than transient intermediates. The role of amino acids extends beyond simple participation in the Maillard reaction; they actively shape both their own degradation pathways and the polymerization process of glucose-derived structures, influencing the final melanoidin architecture. This study provides a novel methodology for the targeted isolation and structural characterization of hydrosoluble colored melanoidin fractions, paving the way for their potential application as water-soluble natural colorants and functional ingredients in food systems. By elucidating the relationship between amino acid polarity, structural composition, and chromophoric behavior, our findings offer critical insights into the design and controlled utilization of Maillard-derived melanoidins in food formulation and processing.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Hofmann, T. Studies on the relationship between molecular weight and the color potency of fractions obtained by thermal treatment of glucose/amino acid and glucose/protein solutions by using ultracentrifugation and color dilution techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 3891–3895. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf980397e (1998).

Sipos, L., Nyitrai, Á., Szabó, D., Urbin, Á. & Nagy, B. Former and potential developments in sensory color masking: Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 111, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.050 (2021).

Adams, A., Borrelli, R. C., Fogliano, V. & De Kimpe, N. Thermal degradation studies of food melanoidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 4136–4142. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf047903m (2005).

Nunes, F. M. & Coimbra, M. A. Melanoidins from coffee infusions. Fractionation, chemical characterization, and effect of the degree of roast. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 3967–3977. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf063735h (2007).

Adams, A., Abbaspour Tehrani, K., Keršienė, M., Venskutonis, R. & De Kimpe, N. Characterization of model melanoidins by the thermal degradation profile. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 4338–4343. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0340254 (2003).

Mohsin, G. F. et al. Structural characterization of melanoidin formed from d-glucose and l-alanine at different temperatures applying FTIR, NMR, EPR, and MALDI-ToF-MS. Food Chem. 245, 761–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.115 (2018).

Etxabide, A. et al. Analysis of Advanced Glycation End products in ribose-, glucose- and lactose-crosslinked gelatin to correlate the physical changes induced by Maillard reaction in films. Food Hydrocoll. 117, 106736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106736 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Ding, Y., Wang, D., Deng, Y. & Zhao, Y. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure conditions on the composition, morphology, rheology, thermal behavior, color, and stability of black garlic melanoidins. Food Chem. 337, 127790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127790 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Color characteristics and pyrolysis volatile properties of main colored fractions from the Maillard reaction models of glucose with three amino acids. LWT 192, 115739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115739 (2024).

Imam, M. S. et al. Adjusted green HPLC determination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir in the new FDA approved co-packaged pharmaceutical dosage using supported computational calculations. Sci. Rep. 13, 137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26944-y (2023).

Ames, J. M. EU COST action 919 melanoidins in food and health. Int. Congr. Ser. 1245, 389–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00877-4 (2002).

ISO. Vol. ISO 4120 : 2021 17 (ISO, Switzerland, 2021).

Mohsin, G. F., Schmitt, F.-J., Kanzler, C., Hoehl, A. & Hornemann, A. PCA-based identification and differentiation of FTIR data from model melanoidins with specific molecular compositions. Food Chem. 281, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.054 (2019).

Zhang, Q., Chen, M., Emilia Coldea, T., Yang, H. & Zhao, H. Structure, chemical stability and antioxidant activity of melanoidins extracted from dark beer by acetone precipitation and macroporous resin adsorption. Food Res. Int. 164, 112045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112045 (2023).

Nooshkam, M. & Madadlou, A. Maillard conjugation of lactulose with potentially bioactive peptides. Food Chem. 192, 831–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.094 (2016).

Bi, B., Yang, H., Fang, Y., Nishinari, K. & Phillips, G. O. Characterization and emulsifying properties of β-lactoglobulin-gum Acacia Seyal conjugates prepared via the Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 214, 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.112 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Formation mechanisms and characterisation of the typical polymers in melanoidins from vinegar, coffee and model experiments. Food Chem. 355, 129444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129444 (2021).

Cui, H. et al. Formation and fate of Amadori rearrangement products in Maillard reaction. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 115, 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.055 (2021).

Mohsin, G. F. et al. Melanoidin formed from fructosylalanine contains more alanine than melanoidin formed from d-glucose with L-alanine. Food Chem. 305, 125459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125459 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Structure and flavor characteristics of Maillard reaction products derived from soybean meal hydrolysates-reducing sugars. LWT 185, 115097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115097 (2023).

Boateng, I. D. & Yang, X.-M. Thermal and non-thermal processing affect Maillard reaction products, flavor, and phytochemical profiles of Ginkgo biloba seed. Food Biosci. 41, 101044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101044 (2021).

Kara, Y. S. & Yıldız, B. Synthesis and substituent effect study on 13C NMR chemical shifts of 4-(substitue-phenyl)-6-methyl-3-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-oxadiazin-5(6H)-one. J. Mol. Struct. 1250, 131787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131787 (2022).

Yadav, L. D. S. Organic Spectroscopy (Springer, 2005).

Violi, J., Bishop, D., Padula, M., Steele, J. & Rodgers, K. Considerations for amino acid analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: A tutorial review. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 131, 116018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2020.116018 (2020).

Miyabe, K. & Suzuki, M. chromatographic study on liquid-phase adsorption on octadecylsilyl-silica gel. AIChE J. 41, 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690410313 (1995).

Van Gemert, L. J. Odour Thresholds: Compilations of Odour Threshold Values in Air, Water and Other Media. second enlarged and revised edition edn, (Oliemans Punter & Partners BV, 2011).

Crews, C. & Castle, L. A review of the occurrence, formation and analysis of furan in heat-processed foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 18, 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2007.03.006 (2007).

Zhang, J. et al. Formation of a creatinine thermal degradation product and its role and participation in the radical pathway of forming the pyridine ring of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Food Chem. 312, 126083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126083 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. Synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one from maltol and its taste identification. Food Chem. 361, 130052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130052 (2021).

Li, H., Tang, X.-Y., Wu, C.-J. & Yu, S.-J. Formation of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-Dihydroxy-6-Methyl-4(H)-Pyran-4-One (DDMP) in glucose-amino acids Maillard reaction by dry-heating in comparison to wet-heating. LWT 105, 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.02.015 (2019).

Choo, J. P. S. & Li, Z. Styrene oxide isomerase Catalyzed Meinwald rearrangement reaction: Discovery and application in single-step and one-pot cascade reactions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 26, 1960–1970. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00473 (2022).

Burdock, G. A. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients 6th edn. (Taylor & Francis Group, 2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Program of Innovation Platform in State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, China; the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2017QNRC001), China; the Open Project of Grain, Oil and Food Engineering Technology Research Center of the State Grain and Reserves Administration / Key Laboratory of Henan Province (GO202207), China; the Natural Science Project of Henan Science and Technology Department-Key Science and Technology Project (232102110141), China; the University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Programs (202410463040), China; the Henan Province Key Research and Development Special Project (231111111800), China; the Young Key Teachers Training Program of Henan Province (2023GGJS059), China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Yuanhui Wang and Guobi Chai; Data curation: Yixian Zhao and Yueying Yang; Formal analysis: Yuanhui Wang, Qidong Zhang and Guobi Chai; Funding acquisition: Yuanhui Wang and Guobi Chai; Investigation: Yueying Yang, Boyu Li and Chenyu Ning; Methodology: Yueying Yang, Qidong Zhang and Guobi Chai; Project administration: Yuanhui Wang, Guobi Chai, Chunqiang Yang and Qidong Zhang; Resources: Yuanhui Wang, Qidong Zhang, Guobi Chai and Chunqiang Yang; Software: Yueying Yang and Guobi Chai; Supervision: Yuanhui Wang and Guobi Chai; Validation: Boyu Li and Xiaokang Wang; Visualization: Yuanhui Wang and Xiaokang Wang; Writing—original draft: Yuanhui Wang and Boyu Li; Writing—review & editing: Yuanhui Wang and Guobi Chai.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Li, B. et al. Molecular structure characteristics and pyrolytic volatiles of hydrosoluble colored fractions from three melanoidins. Sci Rep 15, 17392 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02108-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02108-6