Abstract

Monticola rufiventris belongs to the order Passeriformes and the family Muscicapidae. As the largest group of birds, the phylogenetic relationships within Passeriformes have been a hot topic of research; however, studies on the genus Monticola within Passeriformes are relatively limited. This study presents the first comprehensive sequencing and analysis of the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris. Using Illumina Novaseq 6000 for paired-end sequencing, the results show that the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris is 16,803 bp, containing 13 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA genes, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and 1 control region. Its structure is similar to that of known members of the Muscicapidae family, but there are some differences in gene size. Based on these data, we conducted mitochondrial assembly, selective pressure analysis, relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) analysis, structural prediction of the 22 tRNAs, and phylogenetic tree construction. This study adds new data to the avian mitochondrial genome database, enhances the understanding of the Monticola mitochondrial genome, and provides valuable information for future research in avian taxonomy and phylogenetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Monticola rufiventris, a small bird, belongs to the Muscicapidae family in the Passeriformes order. The order Passeriformes contains 145 families and over 6,500 species, accounting for about half of all existing bird species1.Passeriformes birds exhibit significant differences in size, morphology, and behavior, and have widely adapted to various environments in nature. Their origin, evolution, and the evolutionary relationships among different families have been a focal point of debate and interest in the field of avian biology2,3. Muscicapidae, which includes 53 genera and 351 species, is the most numerous family within Passeriformes4. The family is rich in species and widely distributed, exhibiting diverse ecological habits and morphological characteristics, playing an important role in the study of avian evolution. But, research on the family Muscicapidae is still limited, mainly focusing on simple descriptions of mitochondrial genomes5,6,7,8,9,10,11.M. rufiventris has unique features in terms of plumage color, behavior, and distribution range. In-depth research on it can help understand the diversity and evolution of Muscicapidae.

The mitochondrial genome has characteristics such as a simple molecular structure, strict maternal inheritance, high mutation rates, and rapid evolution. It has become an important genetic marker for studying origins, evolution, and phylogenetic relationships at the molecular level. In recent decades, with the development of molecular techniques and sequencing technologies, an increasing number of international studies have used the complete mitochondrial genome as a marker to investigate the molecular evolution of Passeriformes birds, achieving many significant results12,13,14. However, there are currently relatively few studies on the mitochondrial genomes of Muscicapidae birds, with a low proportion of sequenced species. The number of complete mitochondrial genomes of Muscicapidae published in the GenBank database does not exceed 30 species, and the Monticola genus has only one species, Monticola gularis, that has been made public. There is still a large amount of mitochondrial genome information for many species that needs to be explored.

This study aims to comprehensively analyze the mitochondrial genome characteristics of M. rufiventris, exploring its phylogenetic position and relationships within the Muscicapidae family. Theoretically, it fills the gap in the research on the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris, providing data for understanding the evolution and genetic diversity of Muscicapidae birds, and enhancing the theory of molecular evolution in birds.

Materials and methods

Samples and laboratory analyses

On July 22, 2024, a dead bird was discovered in Yadong County, Tibet Autonomous Region, China (27° 29′ N, 89° 01′ E). Based on its morphological characteristics, it was initially identified as M. rufiventris. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, total genomic DNA from the intestinal tissue was quickly extracted using The TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). With the assistance of Shenzhen Hui tong Biotechnology Company, the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris was determined using high-throughput technology. The animal experiments in this study were approved by the Experimental Animal Management Committee of Dali University (Approval No. 2024-P2-280) and conducted in compliance with local regulations, institutional guidelines, and the ARRIVE guidelines.

Gene sequencing, assembly, and annotation

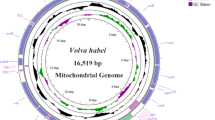

Following DNA quality confirmation, a 350 bp insert library was prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and sequenced in paired-end mode on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Raw reads were quality-filtered using fastp, yielding high-quality clean reads. These reads were then subjected to de novo assembly with SPAdes v3.14.1, generating a graph file that was visualized and analyzed using Bandage to reconstruct the complete mitochondrial genome. The assembled mitochondrial genome was annotated using MITOS15 (http://mitos.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/index.py), with manual refinement of annotation results. Finally, the mitochondrial genome map was generated using the online tool Organellar Genome DRAW v1.2.

Gene analysis

We used DNAsp6 (v6.12.03) to calculate the content of adenine (A) and thymine (T) as well as guanine (G) and cytosine (C) for each gene, and employed the formulas AT skew = (A - T)/(A + T) and GC skew = (G - C)/(G + C)16 to calculate the AT skew and GC skew. The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) was analyzed using MEGA17 (v11.0) software. The tRNAscan-SE18 software was used to predict the cloverleaf secondary structure of 22 types of tRNA.

The phylogenetic tree and evolutionary rate

When constructing the phylogenetic tree, researchers find that the selection of two rRNA gene models in the mitochondrial genome is uncertain19,20. The tRNA genes are short and difficult to align19. Due to high variability in control regions, potential saturation, and numerous gaps21, we selected 13 PCGs from the mitochondrial genomes of 45 bird species representing 8 families, with Gallus gallus designated as the outgroup22. The nucleotide sequences of these PCGs were concatenated and aligned using MUSCLE (implemented in MEGA v11.0) with default parameters. Sites containing gaps or missing data were removed prior to analysis. The General Time Reversible (GTR + G + I) model, identified as the best-fit evolutionary model in MEGA (v11.0), was used to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates for node support assessment23. The final tree was visualized and annotated using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/). Additionally, we calculated the non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) for the PCGs using DnaSP24 (v6.12.03).

Results

Genome organization: structure and composition

The mitochondrial assembly of the M. rufiventris is circular, with a gene sequence length of 16,803 bp. The complete mitochondrial genome contains 13 PCGs, 22 tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes, and 1 control region (Table 1). Additionally, 22 genes (trnF, rrnS, trnV, rrnL, trnL1, nad1, trnI, trnM, nad2, cox1, trnD, cox2, atp8 trnK, atp6, cox3, trnW, trnG, nad3, trnR, nad4L, nad4, trnH, trnS1, trnL2, cytb, nad5, trnT) are transcribed on the heavy strand, while the remaining 9 genes (trnQ, trnP, trnA, trnN, trnC, trnE, trnY, trnS2, nad6) are encoded by the light strand (Fig. 1) ,which is similar to most vertebrates that have been reported25,26,27. In the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris, there are 6 overlaps between genes, with a total length of 29 bp. The longest overlap occurs between atp8 and atp6, with a length of 10 bp, while the shortest overlaps are found between trnQ and trnM, trnC and trnY, and trnS1 and trnL1, each with a length of 1 bp.The nucleotide composition distribution of the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris is as follows: A:29.46%, C:32.74%, G:14.62%, and T:23.17%. This data reflects a higher content of C and A bases in the mitochondrial genome, a characteristic that is consistent with previous studies on avian mitochondrial genomes28,29. The global GC bias and AT bias of the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris are − 0.382 and 0.120, respectively (Table 2). The negative value of the GC bias indicates that the occurrence rate of C exceeds that of G, while the positive value of the AT bias indicates that the content of A exceeds that of T. A detailed analysis of the gene bias data of M. rufiventris reveals that, except for the trnG, trnT, and nad6 genes which show negative bias, the remaining genes have positive AT bias. The GC bias is negative in most genes, with the exception of the trnL1 and nad6 genes, which show positive bias.

The protein-coding genes

The PCGs of M. rufiventris have a total length of 11,395 bp, accounting for 67.82% of the total genome length. Among the 13 PCGs of M. rufiventris, the average AT content is 51.93%, with a range from 49.46% (nad6) to 56.55% (atp8). In these 13 PCGs, all except for cox1, which uses GTG as the start codon, use the standard ATG start codon. These PCGs utilize six different stop codons: cox1 uses AGG; cox2, atp6, atp8, nad4L, and nad3 use TAA; nad1 and nad5 use AGA; cytb and nad6 use TAG; cox3 and nad4 use T; nad2 uses TA. We created a relative synonymous codon usage table (Table S1) based on the codon usage patterns in the PCGs of M. rufiventris. Among all codons, CGA (Arg1) and CUA (Leu2) showed the highest usage frequencies, with RSCU values of 3.44 and 2.92, respectively. Conversely, AGG (Arg2), ACG (Thr), and UUG (Leu1) were the least frequently used, exhibiting much lower RSCU values of 0.08, 0.08, and 0.05, respectively (Fig. 2).

Transfer RNAs and ribosomal RNAs

M. rufiventris has 22 tRNA genes, among which serine and leucine each have 2 tRNA genes, distributed throughout the mitochondrial genome in the protein-coding regions, control regions, and between rRNA genes. Fourteen tRNA genes (trnF, trnM, trnV, trnL1, trnI, trnW, trnD, trnT, trnK, trnS1, trnL2, trnH, trnG, trnR) are encoded on the heavy chain, while eight tRNA genes (trnP, trnE, trnS2, trnC, trnY, trnQ, trnA, trnN) are encoded on the light chain. M. rufiventris mitogenome has 1,544 bp of tRNA genes. Their sizes range from 66 nucleotides (trnS1) to 75 nucleotides (trnL2). In the tRNA genes of M. rufiventris’s mitochondrial genome, only the tRNA-Ser(AGY) cannot fold into the typical cloverleaf secondary structure due to the absence of the “DHU” arm30, while the remaining 21 tRNAs can be identified by referring to the tRNA secondary structures and anticodons of other species(Fig. 3).

The sequence lengths of 12 S rRNA and 16 S rRNA are 985 bp and 1,597 bp, respectively. They are arranged in the genome between the trnF and trnL2 genes, separated by the trnV gene (Fig. 1). In the 12 S rRNA, the nucleotide composition is as follows: A:30.35%, T:20.92%, G: 21.12%, and C:27.61%; while in the 16 S rRNA, the nucleotide composition is: A:34.13%, T:20.91%, G:20.04% and C:24.92%. In both rRNAs, the content of AT (51.27% and 55.04%) is higher than that of GC (48.73% and 44.96%) (Table 2).

Control region

The mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris contains one non-coding region, the Control Region, located between trnF and trnE31,32, with a length of 1,230 bp. In this region, A:26.10%, T:29.19%, C:30.32%, and G:14.39%, with the AT content (55.29%) significantly higher than the GC content (44.71%).

The phylogenetic tree and evolutionary rate

This study constructed a phylogenetic tree based on 13 protein genes from 45 different bird species (Table S2). Phylogenetic analysis supports that Muscicapidae and Turdidae are monophyletic and sister (bootstrap value of 100) (Fig. 4) to each other12. In some earlier studies, M. gularis was classified under Turdidae33,34. In the phylogenetic tree we constructed, M. rufiventris and M. gularis are in the same branch (BP = 100) (Fig. 4). They are closely linked in the evolutionary context, forming a monophyletic group, and both belong to Muscicapidae. Meanwhile, Paradoxornis heudei, Paradoxornis fulvifrons, and Paradoxornis nipalensis, which were previously classified under Muscicapidae17,35, have been reclassified into Paradoxornithidae36.

The non-synonymous and synonymous substitution rates of 13 PCGs in M. rufiventris were calculated, and the results indicate that during evolution, the 13 PCGs in M. rufiventris are primarily characterized by synonymous substitutions (Fig. 5). The Ka/Ks values for the 13 PCGs are all significantly less than 1 (Table S3). The range of Ka/Ks values is from 0.02746 (cox1) to 0.15860 (nad4L). The Ka/Ks values for M. rufiventris, in ascending order, are as follows: cox1 < cox3 < nad1 < cox2 < cytb < nad4 < nad5 < atp8 < nad3 < atp6 < nad6 < nad2 < nad4L.

Discussion

This study presents the structural characteristics of the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris, which is a double-stranded circular DNA molecule encompassing 37 coding genes and one non-coding control region37. Among the 37 coding genes, there are 22 tRNA genes, 13 PCGs, and 2 rRNA genes, which is consistent with the composition found in most vertebrates that have been reported38. Some genes exhibit overlapping and intergenic regions, with overlapping regions generally ranging from 1 to 10 bp and intergenic regions ranging from 1 to 21 bp. In M. rufiventris, the longest coding gene is cox1, measuring 1,551 bp, while the shortest is atp8, at only 168 bp. The base composition of the genome shows a preference for C > A > T > G, with a higher total content of A and T compared to C and G, indicating a high AT content in this genome. The usage of start codons is similar to that of other birds. Regarding the usage of stop codons, there are two types: complete stop codons and incomplete stop codons. Specifically, the coding sequence of nad2 ends with an incomplete stop codon TA, while the coding sequences of cox3 and nad4 end with an incomplete stop codon T. This incomplete stop codon can be converted into a complete stop codon TAA through subsequent polyadenylation during transcription. The remaining PCGs have complete stop codons39,40. In the tRNA genes of the mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris, only the tRNA-Ser (AGY) is unable to fold into the typical cloverleaf secondary structure due to the absence of the “dihydrouridine (DHU)” arm, while the remaining 21 tRNA genes can form the classic cloverleaf secondary structure. According to the phylogenetic tree we established, Monticola belongs to Muscicapidae. P. heudei, P. fulvifrons, and P. nipalensis do not belong to Muscicapidae but to Paradoxornithidae. The ratio of nonsynonymous substitution rate to synonymous substitution rate for the 13 PCGs of M. rufiventris is far less than 1. This indicates that the 13 PCGs have undergone purifying selection, meaning that harmful mutations have gradually decreased, ensuring the stability of gene function41.

Conclusion

This study is the first to sequence the complete mitochondrial genome of M. rufiventris and provides a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of its mitochondrial genome structure. Based on key gene fragments in the mitochondrial genome, a preliminary phylogenetic tree was constructed. From a macro perspective, the addition of the complete mitochondrial genome data of M. rufiventris contributes to the improvement of the mitochondrial genome database for the Muscicapidae family, providing new key clues for the phylogenetic research of Muscicapidae species, enhancing the understanding of the evolutionary relationships among these species, and promoting further development in the fields of taxonomy and evolutionary biology.

Data availability

The data on which the findings of this study are based has been publicly released in the NCBI GenBank database and can be accessed via the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. The access number for the complete mitochondrial genome sequence is PQ459006.

References

Schmitt, C. J. & Edwards, S. V. Passerine birds. Curr. Biol. 32 (2022).

Ericson, P. G. P., Johansson, U. S. & Parsons, T. J. Major divisions in oscines revealed by insertions in the nuclear gene c-myc: a novel gene in avian phylogenetics. Auk 117 (4), 1069–1078 (2000).

Li, Q. W. & Qu, H. Y. Research progress in the molecular systematics of Passeriformes birds. J. Liaoning Norm. Univ. (Nat Sci. Ed) 02, 207–212 (2008).

Gill, F., Donsker, D. & Rasmussen, P. IOC World Bird List (v13.2). https://www.worldbirdnames.org/new/ioc-lists/master-list-2/.

Yang, N., Liu, W. & Yang, K. The complete mitochondrial genome of the snowy-browed flycatcher Ficedula hyperythra (Passeriformes, Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 6, 2870–2871 (2021).

Li, F. J. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of (Passeriformes: Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA. Part B. 5(3), 2322–2323 (2020).

Du, C., Liu, L., Liu, Y., Fu, Z. & Xu, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of daurian redstart Phoenicurus auroreus (Aves:Passeriformes: Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 2231–2232 (2020).

Zhang, N. L. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Siberian rubythroat (Calliope:calliope) from Maorshan, China. Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 8, 110–112 (2023).

Lu, C. H., Sun, C. H., Hou, S. L., Huang, Y. L. & Lu, C. H. The complete mitochondrial genome of dark-sided flycatcher (Passeriformes: Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA. Part B. Resour. 4(2) (2019).

Liu, B. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Grey-streaked flycatcher Muscicapa griseisticta (Passeriformes: Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 4, 1857–1858 (2019).

Min, X., Lu, C. H., Chen, T. Y., Liu, B. & Lu, C. H. The complete mitochondrial genome of Asian brown flycatcher Muscicapa latirostris (Passeriformes: Muscicapidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 4, 3880–3881 (2019).

Johansson, U. S., Fjeldså, J. & Bowie, R. C. K. Phylogenetic relationships within passerida (Aves: Passeriformes): a review and a new molecular phylogeny based on three nuclear intron markers. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 48 (3), 858–876 (2008).

Pacheco, M. A. et al. Evolution of modern birds revealed by mitogenomics: timing the radiation and origin of major orders. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 (6), 1927–1942 (2011).

Barker, F. K. et al. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (30), 11040–11045 (2004).

Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: improved de Novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 313–319 (2013).

Perna, N. T. & Kocher, T. D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 41, 353–358 (1995).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(16) (2021).

Gardner, P. P., Wilm, A. & Washietl, S. A benchmark of multiple sequence alignment programs upon structural RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (8), 2433–2439 (2005).

Sullivan, J. & Joyce P. Model selection in phylogenetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 445–466 (2005).

Krajewski, C., Sipiorski, J. T. & Anderson, F. E. Complete mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae). Auk. 127 (2), 440–452 (2010).

de la Fuente, J. et al. Tick genome assembled: New opportunities for research on tick-host-pathogen interactions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6. (2016).

Charrier, N. P. et al. A transcriptome-based phylogenetic study of hard ticks (Ixodidae). Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 12923 (2019).

Rozas, J. et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Yang, R., Wu, X., Yan, P. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of Otis tarda (Gruiformes: Otididae) and phylogeny of Gruiformes inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37(7), 3057–3066 (2010).

Man, Z., Yishu, W. & Peng, Y. & others. Crocodilian phylogeny inferred from twelve mitochondrial protein-coding genes, with new complete mitochondrial genomic sequences for Crocodylus acutus and Crocodylus novaeguineae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 60(1), 62–67 (2011).

Wei, L., Wu, X. B. & Zhu, L. X. Mitogenomic analysis of the genus Panthera. Sci. China Life Sci. 54 (10), 917–930 (2011).

Yu, J. et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Otus Lettia: exploring the mitochondrial evolution and phylogeny of owls (Strigiformes). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 6, 3443–3451 (2021).

Liu, G., Zhou, L., Li, B. & Zhang, L. The complete mitochondrial genome of Aix galericulata and Tadorna ferruginea: bearings on their phylogenetic position in the Anseriformes. PLoS One. 9, e109701 (2014).

Desjardins, P. & Morais, R. Sequence and gene organization of the chicken mitochondrial genome: a novel gene order in higher vertebrates. J. Mol. Biol. 212 (4), 599–634 (1990).

Mindell, D. P., Sorenson, M. D. & Dimcheff, D. E.Multiple independent origins of mitochondrial gene order in birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95(18), 10693–10697 (1998).

Lowe, T. M. & Chan, P. P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (W1)), W54–W57 (2016).

Zhao, X. A Photographic Guide To the Birds of China, 980 (Commercial).

Zheng, G. A. Checklist on the Classification and Distribution of the Birds of the World, 400 (Science, 2002).

Ding, H. et al. Mitogenomic codon usage patterns of superfamily certhioidea (Aves, Passeriformes): Insights into asymmetrical bias and phylogenetic implications. Animals 13, 96 (2023).

Cai, T. et al. & others. Near-complete phylogeny and taxonomic revision of the world’s babblers (Aves: Passeriformes). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 130, 346–356 (2019).

Quinn, T. W. Molecular evolution of the mitochondrial genome. In Avian Molecular Evolution and Systematics 3–28 (Academic, 1997).

Boore, J. L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 (8), 1767–1780 (1999).

Ojala, D., Montoya, J. & Attardi, G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature 290, 470–474 (1981).

Boore, L. J Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the polychaete annelid Platynereis dumerilii. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18 (7), 1413–1416 (2001).

Hurst, L. D. The Ka/Ks ratio: diagnosing the form of sequence evolution. Trends Genet. 18, 486 (2002).

Funding

This study was completed with the funding of the following institutions: the Natural Science Foundation of China (U2002219); Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Grant no. 202401AT070084); the Special Basic Cooperative Research Programs of Yunnan Provincial Undergraduate Universities’ Association (Grant no. 202301BA070001-045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. and Q.F.Z. are the first authors, X.Y. and C.H.D. are the corresponding authors. This study was conceived and written by R.H. The experimental operations and data analysis were jointly carried out by M.N.D., S.L., and S.B.T. C.H.D. and Q.F.Z. participated in the collection of Monticola rufiventris samples and academic discussions. D.D.J. and X.Y. were responsible for interpreting the experimental results, reviewing key knowledge content, and approving the final draft of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This study has been officially reviewed and authorized by the Administration Committee of Experimental Animals, Dali University, Yunnan Province, P.R. China.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, R., Zhang, Q., Duan, M. et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Monticola rufiventris and phylogenetic implications. Sci Rep 15, 18449 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02187-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02187-5