Abstract

To analyse the prevalence of magnesium disturbances in children admitted to the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) and its relationship with complications and mortality. Single-center, observational, retrospective study. Children with measured serum magnesium levels were included. Clinical, analytical, treatment data, clinical severity scores (Functional Status Scale, Paediatric Risk of Mortality, Paediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction and Paediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score) at admission and during PICU admission, mortality and duration of admission were recorded. A cohort of 200 children (57% male) with a median age of 55 months (interquartile range 8 months to 11 years) were included. Six children (3%) presented initial hypomagnesemia and 26 (13%) presented hypomagnesemia during admission. Hypomagnesemia during admission was significantly associated with the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI) (p = 0.038), shock (p = 0.003), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (p = 0.046). Patients with hypomagnesemia had a higher mortality (15.4% versus 1.7%) (p = 0.006). 64 children (32%) presented initial hypermagnesemia, and 89 (44.5%) presented hypermagnesemia during admission. Hypermagnesemia during admission was significantly associated with heart surgery (p < 0.001), without significant differences in mortality (p = 0.702). Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia are common among children admitted to the PICU. Hypomagnesemia during admission was associated with AKI, shock, ECMO and mortality. Hypermagnesemia during admission was associated with cardiac surgery but not with mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnesium is as an essential cofactor in several critical enzymatic reactions. Alterations in magnesium affect neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic functions1,2,3.

Hypomagnesemia has a prevalence of up to 65% in critically ill patients4,5,6. In some studies, hypomagnesemia has been associated with increased mortality4,7,8,9,10, but other studies have not observed this relationship11,12,13. An association has also been found between hypomagnesemia, sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation, and an increase in the time spent in the intensive care unit (ICU)4,6,13. However, most studies have been conducted on adult patients.

Hypermagnesemia is less common than hypomagnesemia in critically ill patients5,7. Some studies have linked hypermagnesemia with increased mortality4,7,14 and ICU admission duration7 although the results differ among the different series5. Few studies that have analysed the prevalence of hypermagnesemia in critically ill children5.

The objective of our study was to analyse the prevalence of hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia in critically ill children, and its relationship with complications during admission (need for mechanical ventilation, duration of admission, renal failure, sepsis, arrhythmias, cardiorespiratory arrest) and with mortality.

Methods

A single-center, retrospective, observational study was conducted. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), ethics and drug research committee, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón (HGUGM23/2017). Need for informed consent to participate was waived by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Inclusion criteria: All patients admitted to the PICU between January 1st, 2021 and December 31st, 2021, were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: patients without magnesium values recorded during admission to the PICU were excluded.

Variables collected

The following parameters were collected: date of birth, sex, weight, reason for admission to the PICU, total time of admission to the PICU, survival and cause of death. According to our protocols, all patients were evaluated by functional state score, FSS (Functional Status Scale)15, risk of mortality score, PRISM III (Paediatric Risk of Mortality)16, and multiorgan dysfunction scores, PELOD2 (Paediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction)17 and PMODS (Paediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score)18. Analytical values were obtained upon admission and during the stay in the PICU at the times of maximum and minimum magnesium values: magnesium (initial magnesium was the determination made in the first 24 h of admission and the number of magnesium determinations varied depending on the patient), sodium, potassium, pH, bicarbonate, glomerular filtration rate, creatinine, and urea. Administration of drugs that can cause alterations in magnesium values: magnesium metamizole, furosemide in continuous infusion, cyclosporine or tacrolimus, lithium, vasopressors, antacids, laxatives, and enemas. Other treatments administered: nutrition (enteral, parenteral or absolute), mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), cardiac surgery. Complications that could be related to an alteration in magnesium values: acute kidney injury (AKI), grade II or III according to the KDIGO criteria, infections (according to the CDC definitions), supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias, shock (defined as peripheral persistent hypoperfusion with or with hypotension that required volume expansion and/or vasoactive treatment), cardiorespiratory arrest, paralytic ileus. Treatments administered to correct hypermagnesemia or hypomagnesemia during admission.

Definitions of hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia: hypomagnesemia was defined as a magnesium value < 1.6 mg/dl (0.65 mmol/L) and hypermagnesemia as a magnesium value > 2.5 mg/dl (1.02 mmol/L).

Statistical analysis

The recorded data were analysed using the statistical package IBM SPSS 26.0 (IBM corp, Armonk, NY). Continuous quantitative variables are expressed as median and interquartile range. Missing values for the analysed variables were handled using the available-case deletion method. The qualitative variables were compared using the chi-squared test and the Fisher test. The quantitative variables were compared with the non-parametric Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney U tests. To assess the effect of the factors on the serum magnesium disorders, different analysis models were designed using multivariate logistic regression. The variables for which a statistical association was identified in the univariate analysis were included in these models. Those variables for which the existence of collinearity was considered were excluded from this analysis. For all statistical studies carried out, a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

General characteristics of the patients included in the study

During the study period, 327 patients were admitted to the PICU, of these, 127 lacked recorded magnesium values. 200 patients were included in the analysis. The median age was 55 months with an interquartile range (IQR) of 8.2–136.6 months. 57% were men and 43% were women. The median weight was 16.4 kg (IQR 8.3–33 kg). Figure 1 shows the causes for admission of patients. 46.5% of patients were admitted after cardiac surgery. 199 patients (99.5%) had their first blood test taken between the 1st and 4th day of admission and only 1 of them (0.5%) had it taken on day 11 of admission.

Hypomagnesemia in the initial analysis

The median Mg levels in the first analysis was 2.3 mg/dl (IQR 2–2.6 mg/dl). 6/200 patients (3%) presented hypomagnesemia in the first blood test performed during their admission to the PICU. Of them, 2 patients had ARF during admission, 3 had shock and one had paralytic ileus.

The incidence of shock was significantly higher among patients with initial hypomagnesemia than in the rest of the patients. There was no statistically significant relationship between hypomagnesemia in the first analysis and any treatment received or with other clinical complications throughout admission (Table 1). One of the 6 patients with hypomagnesemia on admission to the ICU (16.6%) and 5 of the 194 patients without hypomagnesemia (2.5%) died (p = 0.195).

Patients with hypomagnesemia in the initial analysis had higher PRISM III scores than those who did not presented hypomagnesemia, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.051). There were no significant differences in the other parameters.

Hypomagnesemia during PICU stay

26/200 patients (13%) presented hypomagnesemia during their stay in the PICU. Two patients had hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia during their stay. In 90% of the patients, the lowest magnesium value were observed within the first 7 days of admission to the PICU.

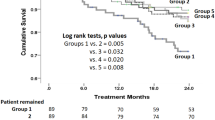

The comparison between patients with and without hypomagnesemia during admission is summarized in Table 1. Patients with hypomagnesemia more frequently presented AKI, shock, paralytic ileus, mechanical ventilation, ECMO, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), and treatment with vasopressors and furosemide. The mortality rate of patients with hypomagnesemia was significantly higher (15.4%) than that of patients without it (1.7%) (p = 0.006).

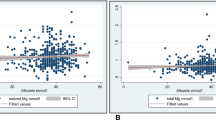

The relationship between hypomagnesemia during admission and the severity of illness scores, age, weight, and duration of admission is shown in Fig. 2. Patients who presented hypomagnesemia had significantly higher PRISM III, PELOD-2, and P-MODS scores than those who did not present it, as well as a longer duration of admission.

Age, weight, duration of admission, and clinical severity scores comparison between patients with hypomagnesemia and those who did not. (Median and interquartile range) at admission and during PICU stay. FSS: Functional Status Scale; PRISM III: Paediatric Risk of Mortality score; PELOD-2: Paediatric logistic organ dysfunction score; PMODS: Paediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score.

To analyse the effect of the different factors on the appearance of hypomagnesemia throughout admission, a multivariate analysis model was performed using logistic regression. Hypomagnesemia was more frequent in patients with acute kidney injury (OR 4.8; CI 1.1–20.9; p = 0.038), shock (OR 36.7; CI 3.5–390.9; p = 0.003), and in those who required ECMO (OR 15.8; CI 1–240.4; p = 0.046) (Table 2).

Hypermagnesemia in the initial analysis

64/200 patients (32%) presented hypermagnesemia in the first analysis performed in the PICU. Of them, 46/64 patients (71.9%) were admitted in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery, and this diagnosis was significantly associated with initial hypermagnesemia (Table 3).

In addition, patients with hypermagnesemia in the first analysis were more frequently treated with magnesium metamizole. The incidence of shock was significantly lower among patients with initial hypermagnesemia than in the rest of the patients. There was no statistically significant relationship between hypermagnesemia in the first analysis with the rest of the treatments received or with other clinical complications throughout admission (Table 3). None of the patients who presented hypermagnesemia on admission died.

The relationship between initial hypermagnesemia and severity of illness scores, age, and duration of admission is shown in Fig. 3. Children with hypermagnesemia at admission were younger and had a lower weight; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Age, weight, duration of admission, and clinical severity scores comparison between patients with hypermagnesemia and those who did not. (Median and interquartile range). FSS: Functional Status Scale; PRISM III: Paediatric Risk of Mortality score; PELOD-2: Paediatric logistic organ dysfunction score; PMODS: Paediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score.

Table 4 compares the serum magnesium values at admission among patients undergoing heart surgery depending on the cardioplegia fluids used.

Hypermagnesemia during PICU stay

Elevated magnesium levels were observed at some point during admission to the PICU in 89/200 (44.5%) of the patients studied. Of the 200 patients, 91% had the highest magnesium value in the first 7 days of admission. The median Mg level in the analysis with the highest magnesium value was 2.4 mg/dl (IQR 2.1–2.7 mg/dl).

A significantly higher percentage of patients with hypermagnesemia underwent heart surgery (71.9%) than patients without hypermagnesemia (27%) p < 0.001.

Patients who developed hypermagnesemia during admission were more frequently treated with ECMO, magnesium metamizole, furosemide in continuous infusion, and vasopressors than patients without hypermagnesemia. There were no significant differences in mortality (Table 3).

Figure 3 shows the relationship between hypermagnesemia during PICU admission and severity of illness scores, age, and duration of admission. Patients with hypermagnesemia had significantly higher PELOD-2 scores than patients without it.

To determine the influence of the factors analysed on the appearance of hypermagnesemia during admission, an analysis was performed using multivariate logistic regression. Hypermagnesemia was independently associated with heart surgery (OR 6.5; CI 3.1–13.8; p < 0.001). No association was found with other variables (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study revealed that hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia were common alterations in children admitted to the PICU, with hypermagnesemia being more common, affecting almost half of the patients (44.5%). Hypomagnesemia was associated with AKI, shock, ECMO, and mortality. Hypermagnesemia was associated with cardiac surgery.

Hypomagnesemia

The incidence of hypomagnesemia in our study was similar to that reported by Verive et al.19, but lower than that found in other studies4,5,6,20.

The most common causes of hypomagnesemia in critically ill patients are digestive malabsorption, sepsis, extracorporeal circulation, kidney disease, diabetic ketoacidosis, and treatment with drugs, such as diuretics, cyclosporine, and insulin5. The clinical manifestations of hypomagnesemia include muscle weakness, respiratory failure, and arrhythmias3,4,6,21.

Several studies have described the relationship between hypomagnesemia and increased complications and mortality in critically ill adult and paediatric patients4,5,6,7,21,22. In our study we separately analysed hypomagnesemia in the initial analysis upon admission to the PICU, and hypomagnesemia developed throughout the PICU stay. No relationship was found between hypomagnesemia on admission with mortality or duration of admission to the PICU, but there was a greater frequency of shock, although we cannot establish whether hypomagnesemia favours the appearance of shock or if patients with shock present more frequently. On the contrary, patients who presented hypomagnesemia at some point during PICU admission had a higher mortality rate, as has been found in other studies on critically ill adults and children4,6,7,21,22,23. Moreover, there was an association between hypomagnesemia throughout admission, the appearance of AKI, paralytic ileus, shock, and with CRRT and ECMO. Due to the study design, it was not possible to determine whether these associations imply causality. As found in other studies in children, there was no relationship between hypomagnesemia and the development of arrhythmias12, a fact that has been described in several studies in adults21,24.

Several authors have described a higher incidence of hypomagnesemia in the postoperative period of heart surgery, both in adults21 and children12. On the other hand, in our study we did not objectify this relationship. On the contrary, in our study, these patients had higher magnesium values. This fact could be related to the composition of the cardioplegia solutions used during heart surgery. In a previous study conducted by our group, it was observed that patients who had received cardioplegic solutions without magnesium had a high incidence of hypomagnesemia, whereas those who received cardioplegic solutions with magnesium, had significantly higher postoperative serum magnesium concentrations12. In our centre, three different cardioplegic solutions containing magnesium are currently used: Celsior© (13 mmol/L), Custodiol© (4 mmol/L), and Pedro del Nido solution© (6.2 mmol/L). As expected, serum magnesium values were higher in patients treated with the solution with the highest concentration of magnesium.

In several studies and meta-analyses on adult patients, a relationship has been found between hypomagnesemia and the need for mechanical ventilation4,6. In our study, mechanical ventilation was significantly more frequent in children with hypomagnesemia (73.1%) than in those without hypomagnesemia (43.1%). It is also not possible to define whether there is causality in this relationship.

Patients with hypomagnesemia received continuous furosemide infusion (which produces increased urinary losses of magnesium) and vasopressors more frequently than patients who did not present hypomagnesemia. We did not find other studies that have analysed these variables.

Finally, the length of admission for children with hypomagnesemia was significantly longer than for those without the condition. In some studies in adults4,6 and children7 hypomagnesemia was related to longer ICU admission times, whereas others have found no significant differences5,12. On the other hand, patients with hypomagnesemia had greater clinical severity with significantly higher PRISM III, PELOD-2, and P-MODS scores.

Therefore, hypomagnesemia during admission to the PICU is related to severe complications, higher mortality, and longer duration of admission to the PICU. Although causal relationships cannot be established from our data, hypomagnesemia may be an indicator of illness severity and complicated evolution and supports the need for periodic controls of this element.

Alterations in other biochemical parameters such as albumin25, lactate26, lactate/albumin ratio27, calcium28, phosphorus29, and chloride30 are also associated with the prognosis of critically ill adults and children, and they can also be used as markers of illness severity or risk of mortality.

Hypermagnesemia

In our study, hypermagnesemia was the most frequent alteration in serum magnesium levels, affecting 32% of patients in the initial analysis and 44.5% throughout admission to the PICU. This incidence is higher than that described in other studies8,9. This high incidence may be because our series includes a high proportion of patients (46.5%) who were admitted to the PICU after heart surgery and could be related to the cardioplegia solutions used12.

The most common causes of hypermagnesemia in the PICU are antacids administration, parenteral nutrition, hypothermia, and AKI5. However, our study did not find an association between hypermagnesemia and AKI.

In several adult studies, hypermagnesemia was correlated to mortality and duration of ICU admission7,14. However, in our study, patients with initial hypermagnesemia, or developed at some point during their admission, did not have higher mortality or longer admission to the PICU.

Treatment with vasopressors and furosemide was significantly more frequent in patients with hypermagnesemia. It is possible that this relationship is due to the fact that these treatments are more frequent during the postoperative period of heart surgery. We did not find other studies that analyse these variables either.

Hypermagnesemia was correlated with magnesium metamizole treatment. Metamizole is presented as metamizole magnesium 2 g/5 ml and the amount of magnesium ranges between 60 and 70 mg (5–6 mEq)31. Considering that the recommended daily dose of magnesium in children is 75–410 mg of magnesium and that enteral and parenteral nutrition also contain magnesium, it is possible that this drug contributed to the development of hypermagnesemia in some patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study of a heterogeneous population of patients with a limited sample size and referred to a single hospital, so the results could not be extrapolated to other centers. Nearly half of the patients were in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery, and as we have previously commented, this may have increased the incidence of magnesium abnormalities in our study compared with other PICUs.

Our study does not allow us to establish a causal relationship between magnesium levels and the rest of the parameters, only allowing us to establish a statistical association between the presence of magnesium alterations and the appearance of certain clinical evolution variables.

It must be considered that it is difficult to evaluate hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia in isolation because they often occur in the context of other electrolytic alterations (calcium, potassium, phosphorus) that can influence magnesium levels19. Regarding treatments such as diuretics, we did not analyse the relationship between the dose and timing of diuretic treatment and the onset of hypomagnesemia. We only analysed whether there was an association with the development of hypomagnesemia after admission to the ICU. We also did not analyse the relationship between the nutritional intake and the development of magnesium abnormalities. On the other hand, total magnesium levels measured in plasma do not reflect intracellular magnesium content or ionized magnesium in blood, which are those that are related to physiological functions and could be better associated with complications and clinical evolution7,12,19,22. A recent studied in critically ill children found higher red blood cell concentrations than in plasma32.

Conclusions

Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia were common in children admitted to the PICU. Hypomagnesemia during admission was associated with AKI, shock, and ECMO. Patients with hypomagnesemia during PICU admission exhibited significantly higher mortality. Hypermagnesemia during admission was associated with cardiac surgery but not with mortality or length of PICU stay. The importance of our study is to highlight the frequency of magnesium abnormalities in critically ill children and the conditions with which they are most associated, so that clinicians can diagnose and treat them early.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRRT:

-

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- FSS:

-

Functional status scale

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PELOD:

-

Paediatric logistic organ dysfunction

- PICU:

-

Paediatric intensive care unit

- P-MODS:

-

Paediatric multiple organ dysfunction score

- PRISM:

-

Paediatric risk of mortality

References

de Baaij, J. H. F., Hoenderop, J. G. J. & Bindels, R. J. M. Magnesium in man: Implications for health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 95, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00012.2014 (2015).

Ahmed, F. & Mohammed, A. Magnesium: The forgotten electrolyte—A review on hypomagnesemia. Méd. Sci. 7, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7040056 (2019).

Sagar, A. N. et al. A comprehensive review of the role of magnesium in critical care pediatrics: Mechanisms, clinical impact, and therapeutic strategies. Cureus 16(8), e66643. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.66643 (2024).

Upala, S., Jaruvongvanich, V., Wijarnpreecha, K. & Sanguankeo, A. Hypomagnesemia and mortality in patients admitted to intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM Int. J. Med. 109, 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcw048 (2016).

Magro, P. R., López, C. A., López-Herce, J., Campos, M. M. & Pérez, L. S. Metabolic changes in critically ill children. An. Esp. Pediatr. 51, 143–148 (1999).

Jiang, P., Lv, Q., Lai, T. & Xu, F. Does hypomagnesemia impact on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Shock 47, 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1097/shk.0000000000000769 (2017).

Singhi, S. C., Singh, J. & Prasad, R. Hypo- and hypermagnesemia in an Indian pediatric intensive care unit. J. Trop. Pediatr. 49, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/49.2.99 (2003).

Dandinavar, S. F., Suma, D., Ratageri, V. H. & Wari, P. K. Prevalence of hypomagnesemia in children admitted to pediatric intensive care unit and its correlation with patient outcome. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 6, 462–467. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20190228 (2019).

Yue, C. Y., Zhang, C. Y., Huang, Z. L. & Ying, C. M. A novel U-Shaped Association between serum magnesium on admission and 28-day in-hospital all-cause mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Front. Nutr. 9, 747035. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.747035 (2022).

Morooka, H. et al. Abnormal magnesium levels and their impact on death and acute kidney injury in critically ill children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 37(5), 1157–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-021-05331-1 (2022).

Saleem, A. F. & Haque, A. On admission hypomagnesemia in critically ill children: Risk factors and outcome. Indian J. Pediatr. 76, 1227–1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-009-0258-z (2009).

Mencía, S. et al. Magnesium metabolism after cardiac surgery in children. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 3, 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130478-200204000-00013 (2002).

Wang, H. et al. Hypermagnesaemia, but not hypomagnesaemia, is a predictor of inpatient mortality in critically Ill children with sepsis. Dis. Markers 2022, 3893653. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3893653 (2022).

Broner, C. W., Stidham, G. L., Westenkirchner, D. F. & Tolley, E. A. Hypermagnesemia and hypocalcemia as predictors of high mortality in critically ill pediatric patients. Crit. Care Med. 18, 921–928. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199009000-00004 (1990).

Pollack, M. M. et al. Functional status scale: New pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics 124, e18-28. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1987 (2009).

Ruttimann, U. E., Pollack, M. M. & Patel, K. M. PRISM III: An updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit. Care Med. 24, 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004 (1996).

Leteurtre, S. et al. PELOD-2: An update of the Pediatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit. Care Med. 41, 1761–1773. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e31828a2bbd (2013).

Graciano, A. L., Balko, J. A., Rahn, D. S., Ahmad, N. & Giroir, B. P. The pediatric multiple organ dysfunction score (P-MODS); Development and validation of an objective scale to measure the severity of multiple organ dysfunction in critically ill children. Crit. Care Med. 33, 1484–1491. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000170943.23633.47 (2005).

Verive, M. J., Irazuzta, J., Steinhart, C. M., Orlowski, J. P. & Jaimovich, D. G. Evaluating the frequency rate of hypomagnesemia in critically ill pediatric patients by using multiple regression analysis and a computer-based neural network. Crit. Care Med. 28, 3534–3539. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200010000-00031 (2000).

Panahi, Y. et al. The role of magnesium sulfate in the intensive care unit. EXCLI J. 16, 464–482. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-182 (2017).

Hansen, B.-A. & Bruserud, Ø. Hypomagnesemia in critically ill patients. J. Intensiv. Care 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0291-y (2018).

Sedlacek, M., Schoolwerth, A. C. & Remillard, B. D. Electrolyte disturbances in the intensive care unit. Semin. Dial. 19, 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-139x.2006.00212.x (2006).

Fairley, J., Glassford, N. J., Zhang, L. & Bellomo, R. Magnesium status and magnesium therapy in critically ill patients: A systematic review. J. Crit. Care 30, 1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.029 (2015).

England, M. R., Gordon, G., Salem, M. & Chernow, B. Magnesium administration and dysrhythmias after cardiac surgery: A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. JAMA 268, 2395–2402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490170067027 (1992).

de Sevilla, M. Á. C. F., Úbeda, M. G., Lugea, A. E. & Gómez, F. T. Magnesium in drugs: Do we have enough information?. Farm Hosp. 38, 494–495. https://doi.org/10.7399/fh.2014.38.6.8017 (2014).

Ari, H. F. et al. Association between serum albumin levels at admission and clinical outcomes in pediatric intensive care units: A multi-center study. BMC Pediatr. 24, 844. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-05331-8 (2024).

Wang, Y., Wu, Q., Zhu, X., Wu, X. & Zhu, P. Lactate levels and the modified age-adjusted quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) score are fair predictors of mortality in critically ill pediatric patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 92, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2025.03.010 (2025).

Arı, H. F., Keskin, A., Arı, M. & Aci, R. Importance of lactate/albumin ratio in pediatric nosocomial infection and mortality at different times. Future Microbiol. 19, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2023-0125 (2023).

Wang, B., Gong, Y., Ying, B. & Cheng, B. Association of initial serum total calcium concentration with mortality in critical illness. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 7648506. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7648506 (2018).

Barhight, M. F. et al. Increase in chloride from baseline is independently associated with mortality in critically ill children. Intensiv. Care Med. 44, 2183–2191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5424-1 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Relationship between serum phosphate and mortality in critically ill children receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1129156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1129156 (2023).

Veldscholte, K. et al. Plasma and red blood cell concentrations of zinc, copper, selenium and magnesium in the first week of paediatric critical illness. Clin Nutr. 43, 543–551 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.01.004 (2024).

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.,S.M.,S.R.T.,C.O., and C.D.A. Data collection and analysis, bibliographic search and analysis, writing and revision of the text J.A.Z.,R.P. and B.R.: Data collection and analysis and revision of the text J.L.H., R.G.: design and direction of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing and revision of the text.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital Institutional Review Board (HGUGM23/2017). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amar, S., Acedo, S.M., Rodríguez-Tubio, S. et al. Magnesium disturbances in critically ill children. Sci Rep 15, 17620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02288-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02288-1