Abstract

The accumulation of heavy metal(loid)s (HMs) in the soils of urban parks in industrial cities has raised global concerns because of their environmental and health impacts. However, traditional deterministic assessments commonly overlook uncertainties in pollution evaluation, failing to accurately quantify source-specific contributions and associated risks. This study combines multivariate statistical methods, machine learning techniques, and positive matrix factorization (PMF) with Monte Carlo simulation to investigate HM sources, probabilistic pollution levels, source-based ecological risks, and population-specific health hazards in seven urban parks in a nickel-based mining city in China. Results showed that average concentrations of Cd (0.53 mg/kg), Cr (77.72 mg/kg), Cu (171.15 mg/kg), Hg (0.03 mg/kg), Ni (125.42 mg/kg), Pb (27.13 mg/kg), and Zn (81.97 mg/kg) exceeded their background values, except for As (11.85 mg/kg), particularly for Cd, Cu, and Ni, with exceedance rates of 98.46%, 100.00%, and 100.00%, respectively. Probabilistic assessments revealed that pollution levels were particularly high due to Cd, Cu, and Ni. Source apportionment using PMF, correlation analysis, hierarchical cluster analysis, and super-clustering of self-organizing maps identified fertilizers and pesticides (19.33%), industrial atmospheric deposition (21.13%), mining and agrochemicals (16.41%), and mining and transport activities (43.13%) as the major pollution sources. Probabilistic ecological risk assessments showed significant risks from Cd, Hg, and Cu. Non-carcinogenic risks were negligible, while carcinogenic risks were cautionary, especially for children. Mining and transportation activities were the main contributors to ecological risks, while fertilizers, pesticides, and Ni were the primary health risk factors. This study provides a robust framework to improve the accuracy of risk evaluation and offers valuable guidance for targeted interventions and sustainable management of urban soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Green spaces in urban parks are vital for enhancing environmental quality, promoting public health, and providing recreational benefits1. However, soils in urban parks often contain elevated levels of anthropogenic metal(loid)s (e.g., As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Zn), particularly near industrial areas2,3. These heavy metal(loid)s (HMs) contribute to persistent soil pollution due to their resistance to degradation, high bioavailability, and significant toxicity4,5. The sources of HMs in urban environments are diverse, categorized into natural sources (e.g., soil parent material) and anthropogenic sources, such as road traffic (e.g., brake discs and tires), waste disposal, and industrial activities3,6,7. The long-term accumulation and increasing concentration of HMs in urban park soils can severely impact ecological integrity and pose risks to human health8,9. Therefore, understanding the sources and risks of HM contamination in urban park soils is essential for mitigating pollution and safeguarding public health, especially in regions with intense industrial activities.

Identifying soil HM pollution sources is crucial for effective risk management and remediation strategies10. Multivariate statistical methods, such as correlation analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), are widely used to differentiate natural sources from anthropogenic inputs6,11,12. For instance, Li et al.13 applied correlation analysis and PCA to identify HM sources in road dust sediments and soils from Lanzhou City, China. Moreover, machine learning methods, such as self-organizing map (SOM), have been increasingly used in the qualitative analysis of soil contamination sources10,14. Integrating SOM with K-means clustering, known as SOM super-clustering, enhances clustering resolution and data interpretation, providing deeper insights into complex datasets12,15. Wang et al.15 employed super-clustering of SOM to identify HM sources in the surface sediments of three lakes in Jiangsu Province, China. However, while these methods qualitatively identify HM sources, they cannot accurately quantify natural and anthropogenic contributions16, prompting the development of quantitative approaches to improve source apportionment. The positive matrix factorization (PMF) model, a widely used quantitative tool, has been extensively applied to quantify pollution sources and their contributions. It is highly valued for its robustness and non-negative outputs17,18. In recent years, the integration of PMF with correlation analysis, HCA, and PCA has gained significant attention as a means to enhance the precision of source analysis19,20,21. Additionally, SOM super-clustering is effective in recognizing and categorizing elements, and their integration with PMF can further substantiate the results by quantifying the relative contributions of various sources10,15. This integration facilitates a seamless transition from qualitative source identification to quantitative apportionment, providing a solid foundation for reliable soil HM pollution source analysis22.

Quantifying human and ecological risks from HM ecotoxicity aids in assessing and managing risks from contaminated soils. Validated techniques, including enrichment factor (EF), Nemerow integrated enrichment factor (NIEF), modified ecological risk factor (mEj), modified Nemerow integrated ecological risk index (mNIRI), and human health risk assessment (HHRA), have been utilized to assess soil HM contamination and associated risks20,22,23,24. Although these methods support environmental health and sustainability, they do not quantify risks related to specific pollution sources25. The growing need for risk management emphasizes the importance of prioritizing pollution sources based on their associated risks11,26. Source-specific risk assessment methods, which integrate source apportionment with risk evaluation, have been developed to quantify the contributions of various pollution sources to ecological and human health risks25,26,27. However, traditional soil HM risk assessments may not accurately reflect current conditions due to variations in concentration, environmental factors, and exposure parameters22,28. Probabilistic approaches, particularly Monte Carlo simulation (MCS), have increasingly been applied to address variability and reduce uncertainties in traditional deterministic methods10,29,30,31. For instance, Zhou et al.22 adopted MCS to quantify soil HM pollution levels, detecting 2.91% moderate and 1.63% heavy Pb contamination, which traditional methods failed to reveal. Source-specific probabilistic risk assessment is essential for guiding priority control strategies for pollution risk management12,22. Despite their advantages, efforts to integrate probabilistic risk assessment into a unified framework for soil HM pollution analysis remain limited. In addition, to our knowledge, no work has been reported on HMs pollution source analysis using correlation analysis, HCA, SOM super-clustering, and PMF for urban park soils. Furthermore, source-oriented risk assessments based on deterministic and MCS approaches are also limited, especially regarding areas influenced by industrial activities.

Herein we present the study of HM contamination in seven park green spaces in Jinchang City, a nickel (Ni) resource-based city and key refining center for platinum-group metals in China. The objectives are: (1) to examine HM (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Zn) concentrations and their probabilistic contamination profiles using EF, NIEF indices, and the MCS method; (2) to trace and quantify HM sources through correlation analysis, HCA, SOM super-clustering, and PMF methods; and (3) to assess concentration-specific and source-specific probabilistic ecological-health risks by integrating MCS with PMF-based mNIRI and HHRA models. This study may broaden the scope of research approaches to soil HM pollution and associated hazards, and could also provide references for environmental management in industrial mining cities.

Materials and methods

Study area and soil sampling

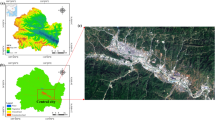

Jinchang (38°21′30″ to 39°00′30″N, 101°34′41″ to 102°34′26″E), located in northwestern Gansu Province within the central part of the Hexi Corridor (Fig. 1a), is a key city along the Belt and Road Initiative (https://www.jcs.gov.cn/). The city experiences a continental temperate arid climate, with elevations ranging from 1,400 to 1,600 m. The climate is characterized by abundant sunlight and moderate temperatures, with annual average temperatures ranging from 4.8 °C to 9.2 °C, sunlight exposure between 51% and 66%, and annual precipitation from 140 mm to 350 mm32. Precipitation decreases from south to north, and the climate is dry, frequently influenced by northwesterly winds and dust storms. Located at the junction of the northern Qilian tectonic belt and the Alashan Plateau. Jinchang has a southwest-high, northeast-low stair-step topography and is rich in copper-nickel sulfide mineralization (https://www.jcs.gov.cn/). This has made Jinchang the largest nickel-cobalt production base, platinum-group metal refining center, and copper production hub in northern China. The city covered an urban area of 3060.26 km², housing approximately 342,800 people and featuring 18.81 km² of green spaces, which provides a per capita green space of 28.58 m² in 202232. Over the years, Jinchang has faced significant environmental issues due to extensive mining and smelting33,34. The impact of mineral resource exploitation on the soil quality of urban parks requires urgent attention.

Location of study area and distribution of soil sampling sites (created using ArcGIS 10.7, https://www.esri.com, based on the standard map (GS2019(1822)). RV: Rose Valley; PGG: Purple Gold Garden; PCS: People’s Cultural Square; JCP: Jinchuan Park; JCMP: Jinchuan Mining Park; LQP: Longquan Park; JSLWP: Jinshui Lake Wetland Park.

In July 2022, a total of 65 representative samples were collected from seven parks in the urban area of Jinchang, with larger parks (e.g., Jinshui Lake Wetland Park and Jinchuan Mining Park) receiving more samples to capture greater variability. These samples were distributed as follows: three from Longquan Park, nine from Jinchuan Park, three from People’s Cultural Square, 16 from Jinshui Lake Wetland Park, 13 from Jinchuan Mining Park, five from Rose Valley, and 16 from Purple Gold Garden (Fig. 1b). The sampling sites were chosen from areas frequently visited by residents to ensure a representative distribution across the parks. Using a bamboo shovel, nine equally weighted topsoil subsamples (0–20 cm) were collected within a 25 m × 25 m area at each sampling site and thoroughly mixed to form a representative composite sample weighing approximately 2 kg (Fig. 1c). These composite soil samples were then placed in clean polyethylene bags, labeled with identification numbers, and transported to the laboratory.

Sample analysis

Soil samples were air-dried at room temperature and sieved through a 2-mm polyethylene mesh to eliminate animal residues, gravels, and plant debris. Soil pH was measured in a 1:2.5 (W/V) soil-water suspension after 30 min of agitation utilizing a glass electrode pH meter (PHS-3 C, Shanghai, China)35. Samples were further sieved through a 0.149 mm nylon sieve to measure HM concentration. The total concentrations of Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb, and Zn were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Thermo X Series 2, USA) following acid digestion (HNO3-HCl-HF-HClO4) of soil samples according to the method of HJ 781-201636. As and Hg concentrations were measured using atomic fluorescence spectrophotometry (XGY-1011 A, National Engineering Center Analytical Instrument, China) after aqua regia digestion (HNO3-HCl), in accordance with the Chinese National Standard HJ 702-201437. The measurement procedure is detailed in Text S1.

Quality assurance and control protocols mainly involved using blank samples, triplicate samples, and soil standard reference materials (GSS 20 and GSS 25, National Standard Detection Research Center, Beijing, China). Approximately 5.00% of the measured samples were triplicate samples, and their analysis showed relative standard deviations were consistently below 5.00% for As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Zn and below 10.00% for Fe. Recovery rates for HMs in the standard reference materials were above 92.60%. The quality control results demonstrated high test accuracy and met the study standards.

Pollution assessment methods

This study used EF to quantify individual HM accumulation and contamination levels, and NIEF to assess overall HM contamination in Jinchang park soils16,38. The detailed descriptions and evaluation criteria for EF and NIEF are described in Text S2 and Table S1.

Source identification and apportionment analysis

Multivariate statistical techniques, including correlation analysis and HCA, along with machine learning methods, such as SOM super-clustering, were employed to assess the relationships among HMs in the soil and to identify their sources.

The SOM model, an unsupervised neural network utilizing competitive learning, is increasingly applied to identify HM pollution sources in soils and sediments12,14. The model was shown as follows:

where n is the number of nodes in the SOM and m represents the amount of input data. Since SOM alone cannot determine the optimal cluster count, K-means clustering is integrated, forming SOM super-clustering to refine the partitioning and improve the classification of HM sources. The optimal number of clusters was identified using the elbow and silhouette methods.

The PMF model, a widely used receptor model, was employed to quantify HM pollution sources in soil18,21. A detailed description of the PMF model is provided in Text S4.

Probabilistic ecological risk assessment

Concentration-based ecological risk

The modified ecological risk factor (mEj) and modified Nemerow integrated ecological risk index (mNIRI) were applied to assess the concentration-based ecological risks of HMs in the soils of Jinchang urban park green spaces. The mEj and mNIRI are defined by Eqs. (2) and (3):

where Tj represents the toxic response factor of element, viz., As = 10, Cd = 30, Cr = 2, Hg = 40, Pb = Cu = Ni = 5, and Zn = 139. EF is the enrichment factor; \(\frac{{{{\left( {{{{C_j}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{C_j}} {{C_{ref}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{C_{ref}}}}} \right)}_{sample}}}}{{{{\left( {{{{C_j}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{C_j}} {{C_{ref}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{C_{ref}}}}} \right)}_{background}}}}\) represent the ratio of the background concentration of element to Fe in topsoil for Gansu province40 and the ratio of element concentration to Fe concentration in Jinchang urban park green space soils, respectively. mEjave and mEjmax is the average and maximum mEj for all elements, respectively. The ecological risk levels determined by mEj and mNIRI values are provided in Table S1.

Source-based ecological risk

The mNIRI integrated with the PMF model was utilized to determine the source-based mNIRI of soil HMs. Unlike traditional mNIRI, which focuses on concentrations, the source-based mNIRI uses contributions from various sources quantified by the PMF model (Ckij) rather than total HM contributions. Ckij represents the mass contributions of the jth HMs from source k in sample i (mg/kg), which is estimated using Eq. (4)27:

where Ck*ij and Ci denote the contribution of the jth HM from source k (mg/kg) and the concentrations of soil HMs in the ith sample (mg/kg), respectively.

Human health risk assessment (HHRA)

Concentration-based HHRA

The USEPA’s HHRA model was employed to determine the concentration-based health risks associated with soil HMs of Jinchang urban parks41. Given the behavioral and physiological disparities among different groups, separate assessments were conducted for children, adult males, and adult females20,41. Detailed description for the concentration-based HHRA method is presented in Text S3.

Source-based HHRA

Similar to the source-based ecological risk, integrating HHRA with PMF results quantifies health risk contributions from various sources. The source-based HHRA substitutes overall HM contributions with those from distinct sources determined by the PMF model (Ckij). Source-based health risks can be calculated using Eqs. (5), (6), (7)25.

where ADIkijing, ADIkijinh, and ADIkijdermal represent the average daily intake through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal pathway for HM j from source k in the ith sample, respectively (mg/kg/d), definitions and values for the other variables are detailed in Text S3. Ckij is the same as Eq. (4).

The non-cancer and cancer risks posed by soil HMs from various source were quantified using the hazard index (HI) and total cancer risk (TCR) based on Eqs. (8), (9), (10)25,41.

where the HQkij,p and CRkij,p denoted the hazard quotient and the cancer risk on the pth exposure route for the jth HM from source k in the ith sample (mg/kg), respectively. HQkij or HIkij values above 1 indicate potential adverse effects, while values below 1 suggest negligible non-carcinogenic effects18,41. CRkij or TCRkij values above 1 × 10− 4 indicate potential cancer risk, values below 1 × 10− 6 suggest no significant risk, and values between 1 × 10− 4 and 1 × 10− 6 indicate cautionary cancer risks18,41. Note that due to the much higher toxicity of Cr(VI) compared to Cr(III) in soil42, the total Cr concentration was multiplied by a factor of 1/7 to assess the health risk of Cr43 in this study. RfD and SF represented the reference dose and the carcinogenic slope factor for soil HMs, respectively, and were shown in Table S3.

Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) and sensitivity analysis

This study used EF, NIEF, mEj, mNIRI, and the HHRA model with MCS to assess probabilistic pollution levels and ecological and human health risks in Jinchang urban park soils. Risk variability and uncertainty were modeled through 10,000 iterations at a 95% confidence interval. Probability distributions of HM concentrations and HHRA parameters are provided in Tables S4 and S2. Sensitivity analysis quantified the contribution of variables influencing pollution, ecological risks, and health risks in MCS. High sensitivity values indicate greater impacts on uncertainty28.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2022 and SPSS 22.0 (IBM, USA). ArcGIS 10.8 (ESRI, USA) visualized the spatial distribution of soil HMs. Correlation analysis and HCA were performed using SPSS 22.0. Correlation coefficients (r) from the correlation analysis reflect relationships between HMs, indicating shared pollution sources or environmental influences19,20. High r values suggest stronger homogeneity, indicating common sources or migration pathways44. The HCA was performed using Ward’s method and absolute correlation distance, with similarity as the standard. SOM super-clustering mapping was conducted using MATLAB 2023b (MathWorks, USA). In SOM super-clustering analysis, color similarity among samples reflects elemental association14. HM source allocation was performed using the PMF model 5.0 (USEPA). Probabilistic pollution and its associated ecological and health risks were evaluated using MCS methods in Oracle Crystal Ball 11.1.24 (Oracle, USA). Graphs were created using Origin Pro 2021 (Origin Lab, USA).

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics of heavy metal(loid)s in park green space soils

The statistical results for eight HMs concentrations and pH values in Jinchang urban park green space soils are listed in Table 1. The pH values ranged from 7.80 to 9.35, with a median of 8.81 (Table 1), indicating the green space soil throughout the study area was alkaline. These pH levels aligned with those observed in previously studied mining-influenced soils from the Jinchang City33. All measured concentrations, as well as their mean and median values, were below the respective risk screening limits for soil contamination of development land in China45 (Table 1), suggesting negligible risk to human health2. However, when compared with the soil background concentrations for elements in Gansu province40, all these mean and median concentrations exceeded the background levels, except for As (Table 1). The proportions of samples exceeding background values were 27.69% for As, 98.46% for Cd, 66.15% for Cr, 100.00% for Cu, 61.54% for Hg, 100.00% for Ni, 72.31% for Pb, and 83.08% for Zn. This indicates a certain degree of enrichment of As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Hg, Ni, Pb, and Zn in the soils of urban park green spaces, particularly with the accumulation of Cd, Cu, and Ni, which is consistent with previous studies in the surrounding areas33,46.

The coefficient of variation (CV), which indirectly indicates the spatial variability and anthropogenic impact of the analyzed HMs in the research area, was highest for Cu (88.26%), followed by Ni (80.66%), Hg (70.54%), Cd (64.38%), Pb (44.17%), As (34.27%), Cr (24.38%), and Zn (19.99%) (Table 1). The high CV values (> 36%) of Cu, Ni, Hg, Cd, and Pb confirm anthropogenic contributions to high concentrations and spatial heterogeneity in green space soils19.

To better understand the HM concentrations in the soil, we compared the results of this study with those reported in urban park soils globally. Higher concentrations of Ni and Cu were observed in this study area compared to western China (e.g., Lanzhou13, Tianshui48, and Guiyang49 and Beijing2 (Table 1). Furthermore, the concentrations of Ni and Cu in the park soil were higher than those reported in Aberdeen (Scotland)50, Shahroud (Iran)51, and Madrid (Spain)52 (Table 1). This can be attributed to the significant geological background of Cu-Ni deposits, along with the long-term extraction and smelting of Cu and Ni in Jinchang City34.

Probabilistic pollution levels of heavy metal(loid)s in park green space soils

The EF assessment of HMs in Jinchang park soils, based on probabilistic and deterministic methods, is shown in Fig. 2 and Table S5. Simulated EF mean values align with actual values but slightly exceed them overall (Fig. 2; Table S5). Probabilistic MCS results show As, Cr, Hg, Pb, and Zn exhibit no to moderate pollution. Ni showed minimal pollution in 35.64%, moderate in 42.57%, and significant or higher in 17.82% of samples (Fig. 2f). Cd exhibited minimal pollution in 21.78%, moderate in 49.50%, and significant or higher in 27.72% of samples (Fig. 2b). Cu showed the greatest variability: minimal pollution in 16.83%, moderate in 34.65%, significant in 42.57%, and very high in 3.96% (Fig. 2d). Both measured and simulated EF assessments indicated that Cu and Cd were the most enriched HMs, followed by Ni in the study area.

Simulated NIEF mean values were slightly higher than actual values, indicating very high pollution (5 ≤ NIEF < 10), while actual values showed significant pollution (3 ≤ NIEF < 5) (Fig. 2i). Probabilistic NIEF results indicated pollution levels of minimal (1 ≤ NIEF < 2) in 23.76%, moderate (2 ≤ NIEF < 3) in 17.82%, and significant (3 ≤ NIEF < 5) in 20.79% of sites. Additionally, 23.76% and 11.88% of sites showed very high (5 ≤ NIEF < 10) and extremely high pollution (NIEF ≥ 10), respectively. Sensitivity analysis revealed that Cu contributed the most (97.18%), followed by Cd (5.92%) and Ni (4.48%) (Fig. S1). This confirms Cu, Cd, and Ni as key contributors to pollution risk.

In single- and multi-element pollution assessments, simulated mean values slightly exceeded or fell below the measured means (Fig. 2; Table S5). These discrepancies are attributed to limited sampling coverage, small sample size, and environmental heterogeneity22,23,53. MCS-based probabilistic assessments more effectively capture area-wide pollution levels and reduce data uncertainties compared to deterministic methods22,28. For instance, probabilistic pollution assessment identified 4.00% of sites with very high and 1.00% with extremely high Cu pollution (Table S5). These findings highlight the limitations of deterministic approaches, which rely solely on point-sampled data, and underscore the advantages of probabilistic methods in improving risk characterization and informing environmental management.

Overall, Cu, Cd, and Ni are the main pollutants in the park soils of Jinchang City, likely due to decades of non-ferrous metal mining activities in the area34. Given their prominence, Cu, Cd, and Ni should be prioritized in soil HM pollution management strategies for the region.

Source identification and apportionment of heavy metal(loid)s in park green space soils

The results of the correlation analysis indicated significant positive correlations (r > 0.70, P < 0.01) among the pairs Cd–Cu, Cd–Pb, Cd–Zn, Cu–Ni, Cu–Pb, Cu–Zn, Ni–Pb, Ni–Zn, and Pb–Zn (Fig. 3a; Table S6), suggesting that these HMs may originate from similar sources8,44. Moderate correlations (0.50 < r < 0.70, P < 0.01) for Cd–Ni, Cr–Cu, Cr–Ni, Cr–Pb, and Cr–Zn (Fig. 3a; Table S6) indicate complex pollution patterns or multiple sources20. Notably, As and Hg showed no correlation with the other six elements, indicating distinct pollution sources11.

The HCA results revealed four distinct clusters within a 10–20 distance range on the dendrogram of soil HMs: (1) As, (2) Cd, (3) Hg, and (4) Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and Ni (Fig. 3b). Notably, Cd formed a distinct cluster, suggesting a unique source or behavior. These classifications were further validated by the SOM super-clustering analysis.

SOM super-clustering was employed to cross-validate the HCA results, with the 7 × 7 neuron structure identified as the most informative through self-organizing training and learning (Fig. 3c). The distribution patterns of Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn showed similar color gradient changes, with their highest accumulations located in the upper-right area21. In contrast, the regions with elevated levels of As, Cd, and Hg were spatially distinct, positioned in the lower-left, upper-middle, and lower-central to upper-middle-left parts, respectively (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn likely share common sources or exhibit similar environmental behaviors, while As, Cd, and Hg are influenced by distinct factors, indicating separate pollution origins14. K-means clustering of the SOM-trained neurons further categorized the samples into four clusters (I–IV) (Fig. 3c). Cluster I included four samples, while Cluster IV contained the majority (37 samples). Clusters II and III comprised 13 and 11 samples, respectively.

The PMF model was employed to obtain the source contributions to soil HMs in Jinchang urban park green space. Detailed procedures for data validation, result optimization, and error evaluation in preliminary PMF model runs are provided in Text S5. Four HM pollution sources in park green space soils were identified: Factor 1, Factor 2, Factor 3, and Factor 4, contributing 19.33%, 21.13%, 16.41%, and 43.13% of the total, respectively (Fig. S2).

Factor 1 showed high loading values for As (65.52%) and moderate loadings for Cr (25.56%), Zn (23.51%), and Pb (22.84%), identifying As as the dominant metal for this factor (Fig. S2). As formed a distinct group in both HCA and SOM super-clustering analyses, with no connection to other HMs, suggesting a different source for As. Descriptive statistics and EF assessments indicate that As contamination at several sampled sites was influenced by human activities (Table 1; Fig. 2a). Furthermore, high As concentrations were concentrated in the northwest section of the study area (Fig. S3a), encompassing approximately 0.38 km2 of land containing aromatic herbs, flowers, and ornamental trees. In urban parks, plant maintenance typically involves annual applications of fungicides, pesticides, and insecticides to control pests and diseases, as well as chemical fertilizers and herbicides to promote growth. Many of these agricultural chemicals, such as pesticides, fungicides, and organic fertilizers, contain elevated levels of As, Zn, and Pb26,54,55. These elements, which exhibit limited mobility, gradually accumulate in the soil due to repeated applications, leading to increased contamination over time55. Consequently, Factor 1 is likely associated with the application of fertilizers and pesticides.

Factor 2 exhibited the highest loadings for Hg (88.06%) (Fig. S2). The observation that 61.54% of samples exceeded background Hg values, combined with high variability (Table 1), suggests significant human influence. Anthropogenic inputs for Hg in soils mainly include fossil fuel combustion56,57, mining58, and atmospheric deposition from industrial activities such as smelting, electroplating, plastic manufacturing, and cement and petrochemical production, and waste combustion55,58,59. Elevated Hg concentrations were mainly found in the central-eastern region, with isolated occurrences at other sites (Fig. S3e). These areas are near a non-ferrous metals industrial park engaged in sulfur chemical, coal chemical, and non-ferrous metal industries, which likely generate significant metal-rich particulate emissions that re-enter soils via atmospheric deposition. Unlike other metals, Hg, due to its high volatility, is primarily transported by airflow57. Hg remains stable in the atmosphere for six months to two years, depositing into soils through wet and dry processes59. Therefore, Factor 2 likely represents atmospheric deposition from industrial activities.

Factor 3 was predominantly weighted by Cr (47.29%) and Zn (34.32%), followed by Pb (21.11%) (Fig. S2). Over 65% of sampled sites had Cr, Zn, and Pb concentrations exceeding background levels, with Cr and Pb showing moderate variability (Table 1), indicating anthropogenic influence. Cr in surface soils originates from both geological processes and human activities, including solid waste, battery materials, industrial residues, metal smelting, mining, fertilizers, and pesticides60,61,62. High Cr concentrations were found in the southwestern and northeastern zones (Fig. S3c). The southwestern region, centered in Jinchang City, hosts mineral extraction, non-ferrous metal smelting, and tailings storage, likely releasing Cr, Zn, and Pb due to historical copper and nickel mining59. Additionally, elevated Zn and Pb levels in the northeastern and central-western zones (Fig. S3) may result from green space maintenance using fertilizers and pesticides62,63. Thus, Factor 3 reflects a mixed source of mining activities and agricultural inputs.

Factor 4 was heavily loaded with Cu (87.40%), Cd (72.58%), and Ni (68.79%), and moderately loaded with Pb (45.18%), and Zn (28.60%), indicating Cu, Cd, and Ni as dominant metals. EF analysis showed that park soils were mainly contaminated with Cu, Cd, and Ni, indicating strong anthropogenic influence (Fig. 2b and d, and f). The study area, rich in copper and nickel sulfide deposits, ranks second globally in Cu and Ni production33,34. Mining and smelting activities have released persistent metals, causing significant Cu and Ni accumulation in soils23,34,59. High Cu, Cd, Pb, and Zn levels were found in the central-western area near dense urban regions with heavy traffic (Fig. S3), indicating traffic-related contributions. Pb is a known marker of vehicle fuel combustion, engine operations, and catalytic systems20,64. Gasoline and natural gas combustion release Cd into soil4,49. Wear and tear of automobile components (e.g., tires, brake pads) contribute to Pb, Cu, Zn, and Cd accumulation in soils11,49. Intense mining and trade activities have increased transportation demands in the study area. correlation analysis, supported by HCA and SOM super-clustering analyses, showed that Zn, Pb, Cu, Ni, and Cd originate from mixed sources (Fig. 3). Thus, Factor 4 is mainly attributed to mining and transportation activities.

In summary, soil HM accumulation primarily stems from agrochemical applications, industrial atmospheric deposition, and mining and transportation activities. Among these, mining and transportation (Factor 4) were the dominant contributors to soil HM enrichment (Fig. S2). The cumulative application of agrochemicals for park maintenance also significantly contributes to soil HM inputs. Based on these findings, local authorities should focus on regulating the impacts of industrial and mining activities on soils while mitigating the long-term effects of low-dose agrochemical use.

Probabilistic ecological risk evaluation of heavy metal(loid)s in park green space soils

Concentration-based ecological risk

The concentration-based ecological risk assessment of HMs in Jinchang urban park green space soils using probabilistic and deterministic mEj methods is shown in Fig. 4 and Table S7. Measured mEj values showed 98.46% of Cd and 56.93% of Hg samples posed moderate to very high risks, with maximum values > 160, indicating high ecological risk (Table S7). For Cu, 70.77%, 23.08%, and 6.15% of samples had low, moderate, and considerable risks, respectively, averaging 33.33 (Table S7). Risks for As, Cr, Ni, Pb, and Zn were largely low (> 96.00% of samples) (Table S7). MCS simulations revealed 96.04% of Cd and 54.46% of Hg samples had moderate to high risk, with maximum values > 320 (Fig. 4b). For Cu, 72.29% of samples had low risks, while 20.79%, 5.94%, and 0.99% showed moderate, considerable, and high risks (Fig. 4d). Simulated Ni risks were low (< 40) for 94.06% of samples, moderate (40–80) for 4.95%, and considerable (80–160) for 0.99% (Fig. 4f). Risks for As, Cr, Pb, and Zn were predominantly low. Both measured and simulated mEj values ranked pollutants as Cd > Hg > Cu > Ni > As > Pb > Cr > Zn (Fig. 4; Table S7), confirming Cd as the primary ecological risk, followed by Hg and Cu in the study area.

Average mNIRI was 96.77, with 38.46% of samples indicating considerable risk (80–160) (Table S7). Low risk (< 40), moderate risk (40–80), and high/very high risks (160–320 and > 320) were observed in 9.23%, 38.46%, 12.31%, and 1.54% of samples, respectively. Simulated mNIRI averaged 94.23, with 33.66% of samples indicating considerable risk (80–160) (Fig. 4i). Low (< 40), moderate (40–80), high (160–320), and very high (> 320) risks were found in 11.88%, 41.58%, 11.88%, and 0.99% of samples, respectively (Fig. 4i). Sensitivity analysis confirmed Cd (97.17%) and Hg (4.77%) as the main contributors to mNIRI (Fig. S4). Despite not being the primary pollutant (Fig. 2), Hg poses moderate to very high ecological hazards due to its high toxicity26,39. Although probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) and traditional deterministic risk assessment (DRA) yield consistent results for soil HM contamination risks, the DRA method, which relies on direct soil HM concentration data, often fails to accurately capture overall pollution risk22. This discrepancy can lead to both overestimation and underestimation of pollution risks, supporting previous findings that highlight the superiority of probabilistic methods for more accurate risk assessments22,28.

In conclusion, Cd and Hg are the primary contributors to the potential ecological risks in the soils of the study area, with Cu following as the second most significant element. These findings are consistent with previous studies that identified Cd and Hg as major ecological hazards in soils, including those around gold smelting areas11, karstic urban parks8, and various regions across China55. Cd and Hg, the primary ecological hazards, negatively impact microbial communities8 and disrupt plant physiological and metabolic activities14,29. Thus, strengthening monitoring of Hg, Cu, and Cd is essential to better understand pollution dynamics and mitigate ecological risks.

Source-based ecological risk

The source-specific probabilistic ecological risk results for HMs in Jinchang urban park green space soils based on the combined use of MCS, PMF, and mNIRI are illustrated in Fig. 5. The average mNIRI values for Factors 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 18.02, 19.73, 15.32, and 40.28, respectively (Fig. 5a). Factor 4 showed a moderate ecological risk, unlike the low risks from the other factors. Contributing 43.14% to the total mNIRI, Factor 4 was the primary ecological risk source (Fig. 5b). Statistical analysis indicated that Factor 4 had probabilities of 62.38% for low risk, 29.70% for moderate risk, and 7.92% for considerable risk (Fig. 5c). Factors 1 and 2, with lower mNIRI values, had moderate risk probabilities of 4.95% and 6.93%. Factor 3 contributed the least to ecological risk, showing 97.03% low risk and 2.97% moderate risk probabilities (Fig. 5c). Sensitivity analysis results show that Cd had the highest impact on mNIRI (Fig. 5d), consistent with concentration-based results.

Probabilistic cumulative ecological risk evaluation using Monte Carlo simulation: (a) probability distribution for concentration-based and source-based mNIRI values; (b) source contributions to mNIRI; (c) probability of various ecological risks from all sources and total concentrations; (d) sensitivity analysis for mNIRI calculation.

Briefly, Factor 4 accounted for 43.14% of the total mNIRI, identifying it as the main source of ecological risk due to high levels of Cu (87.40%), Cd (72.58%), and Ni (68.79%). High mean mEj values for Cd (124.46), Hg (53.87), and Cu (32.63) were also observed (Fig. 4b, e, d), indicating considerable ecological risks (Mean mNIRI = 93.89) from these metals. These findings indicate that soil HMs source contributions affect ecological risks and emphasize that toxicity response coefficients contribute more to ecological risks than HM concentrations11,23,26. Low level but high toxicity of Hg in soils can lead to significant risks. Similar scenarios were observed by Zhou et al.11 and Jiang et al.63, highlighting that sources with low contribution rates to overall pollution can present high ecological risks due to the presence of highly toxic elements. These elements, although present in low concentrations, can bioaccumulate in the food chain and have long-term detrimental effects on both wildlife and human health9. Consequently, Factor 4, i.e., mining and transportation activities, along with Hg, should be prioritized to mitigate ecological risks in Jinchang urban park soils.

Probabilistic health risk of heavy metal(loid)s in park green space soils

Concentration-based health risk

The probabilistic risk assessment of soil HMs for children, adult females, and males is shown in Fig. 6 and Table S8. Non-carcinogenic risks (HI) were below 1.00 for all groups, indicating negligible risks (Fig. 6a; Table S8). HI values were highest in children, followed by males and females. Despite negligible non-carcinogenic risks, As and Cr contributed 26% and 58% of the total risk, respectively (Fig. 6b–d). Cd, Pb, Ni, Cu, Hg, and Zn collectively contributed less than 22% to non-carcinogenic risks. Sensitivity analysis identified ingestion rate (IngR), exposure frequency (EF), Cr, and As as key factors influencing non-carcinogenic risks (Fig. S5). Ingestion was the primary exposure route, consistent with Penteado et al.65, who identified direct soil ingestion as the main exposure pathway in urban parks in Brazil, and Ding & Hu66, who found higher non-carcinogenic risks from HM ingestion near industrial areas in China. Residents and visitors are advised to avoid hand-to-mouth actions, wash hands frequently, and maintain hygiene to minimize HM intake.

Probability distributions of the concentration-based (a) hazard index (HI) and (e) total carcinogenic risk (TCR) for children and adults, and contribution proportions of non-carcinogenic risk (NCR) for (b) adult males, (c) adult females, (d) children, and carcinogenic risk (CR) for (f) adult males, (g) adult females, (h) children.

The 95th percentile TCR values for adults and the mean TCR values for all populations ranged from 1 × 10− 6 to 1 × 10− 4 (Fig. 6e). Approximately 84.16% TCR values for children, ~ 96.04% for females, and 97.03% for males fell within this range (Fig. 6e). A 95% TCR value between 1 × 10− 6 and 1 × 10− 4 indicates a cautionary carcinogenic risk11,27. Notably, the 95th percentile TCR values for children exceeded 1 × 10− 4 (Fig. 6e), suggesting a potential cancer risk67. Therefore, cancer risks across all populations warrant attention. Ni was the primary contributor to carcinogenic risk, accounting for 86.35% in both males and females, and 86.34% in children (Fig. 6f–h). As, Cd, Cr, and Pb collectively contributed less than 25% to carcinogenic risk for all groups. Sensitivity analysis identified Ni, IngR, and EF as key factors influencing carcinogenic risk (Fig. S5), emphasizing the need to address Ni exposure.

The traditional DRA method, which uses fixed parameters, produced slightly higher risk estimates than PRA (Table S8). This aligns with previous findings that DRA may either overestimate or underestimate health risks22,23,27. The discrepancy may result from limited sampling data due to cost and uncertainty constraints22 and the inability of fixed DRA parameters to capture variability in HM concentrations and exposure28. DRA results fell within the 5–95% confidence interval of PRA (Table S8), partially reflecting health risk levels. However, DRA is limited by its static approach, overlooking variability in HM concentrations and exposure parameters compared to PRA22,27.

Source-based health risk

Source-specific probabilistic health risk assessments of soil HMs in Jinchang urban parks for adults and children are illustrated in Fig. 7, Fig. S6, and Table S9–S11, using MCS, PMF, and HHRA. The probability HI for HMs from all sources was below 1 for all populations (Fig. S6a–c), indicating negligible non-carcinogenic risks. Adult females and children exhibited similar risk characteristics for specific sources (Fig. S6a–b). Factor 1 was the largest contributor to HI (~ 33%), followed by Factor 3 (~ 30%), Factor 4 (~ 25%), and Factor 2 (~ 11%) (Fig. S6d–f). Children were more vulnerable to non-carcinogenic risks than adults (Table S9–S11). This aligns with previous studies22,27,65, which suggest that children face greater risks due to increased exposure to toxic agents, particularly through hand-to-mouth behaviors.

Regarding carcinogenic risk, mean TCR values for children were 5.44 × 10− 6 (Factor 1), 6.55 × 10− 6 (Factor 2), 1.21 × 10− 5 (Factor 3), and 4.01 × 10− 5 (Factor 4) (Fig. 7a). Factor 4 contributed most to children’s risk (62.50%), followed by Factor 3 (18.90%), Factor 2 (10.20%), and Factor 1 (8.50%) (Fig. 7d). The probability of cautionary risk (1 × 10− 6≤ TCR < 1 × 10− 4) for children was 100% for Factor 1–3 and 94.06% for Factor 4, the probability of potential risk (> 1 × 10− 4) for children was 5.94% for Factor 4 (Fig. 7a). Ni was the largest contributor to Factor 1’s TCR, accounting for 86.4% in children, 86.3% in females, and 86.4% in males (Fig. 7d–f). This finding contrasts with previous studies8,11,29, which attributed the carcinogenic risk mainly to As. This difference is likely due to the lower slope factor for Ni and its higher concentration compared to other metals. Furthermore, Factor 4 was the main contributor to adult carcinogenic risk, with mean TCR values of 2.14 × 10− 5 (females) (Fig. 7b) and 1.83 × 10− 5 (males) (Fig. 7c), similar to children. Similar to non-carcinogenic risks, children face higher carcinogenic risks than adults.

In summary, exposure to park soils poses no non-carcinogenic risks but presents a cautionary and minimal potential level of carcinogenic risk. The TCR contributions followed the order: Factor 4 > Factor 3 > Factor 2 > Factor 1. Factor 4, with high levels of Cu (87.4%), Cd (72.6%), and Ni (68.8%), Factor 4, with high levels of Cu (87.4%), Cd (72.6%), and Ni (68.8%), was the main contributor to soil HM accumulation (Fig. S2), accounting for approximately 65% of carcinogenic risks—substantially higher than other anthropogenic sources (Fig. 7d–f). This is mainly due to the elevated metal concentrations and toxicity coefficients11,68. Sensitivity analysis identified IngR, EF, and metal concentrations (As, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb) as key determinants of non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks (Figs. S7 and S8). Children faced higher health risks than adults (Table S9–S11). Consequently, policymakers should prioritize high-risk groups by enforcing stricter regulations and implementing effective remediation to reduce HM exposure. Individuals can reduce risks by maintaining hygiene, avoiding prolonged soil exposure, and wearing masks in polluted areas.

Limitations and prospects

This study investigated HM sources, probabilistic pollution levels, and associated ecological-health risks in urban park soils using multivariate statistical methods, the SOM super-clustering technique, the PMF model, and MCS analysis. However, a limitation of the study is the omission of key soil properties, such as soil type, organic matter content, and texture, which play a crucial role in HM accumulation. Future research should address the relationship between these soil properties and HM pollution to reduce potential biases in risk assessment and enhance pollution control strategies. Additionally, the bioavailability of HMs in soils was not considered, which may have led to an overestimation of the pollution risks. Therefore, future ecological and health risk assessments should incorporate bioavailable HM concentrations to improve accuracy.

Conclusions

This study reveals significant HM contamination in urban park soils of Jinchang, an industrial mining city in China, with Cu, Cd, and Ni as the primary pollutants. Mining and transportation activities were identified as the main contributors, accounting for a substantial portion of the contamination, while atmospheric deposition predominantly contributed to Cu levels. Mixed sources, including mining and agrochemicals, were linked to Cr and Zn pollution. Probabilistic risk assessments highlighted Cd and Hg as the key ecological risk factors, with non-carcinogenic health risks being negligible and carcinogenic risks remaining at a cautionary level. The integration of multivariate statistical methods, machine learning (i.e., SOM super-clustering), and receptor models proved effective in determining the sources of soil HM pollution. Furthermore, probabilistic assessment techniques offered improved management of uncertainties and variability compared to traditional deterministic methods. Despite these findings, current risk assessments are based on total metal concentrations, which may not fully reflect actual ecological and health risks. To further improve these assessments, future research should also integrate the influence of soil properties, such as texture and organic matter content, on HM bioavailability and speciation. This will enhance the accuracy of risk evaluations and inform more targeted pollution management strategies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Zheng, Y. C. et al. Quantitative evaluation of urban green exposure and its impact on human health: A case study on the 3-30-300 green space rule. Sci. Total Environ. 924, 171461 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Heavy metal(loid)s in the topsoil of urban parks in Beijing, China: concentrations, potential sources, and risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 260, 114083 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Source-sink relationships of anthropogenic metal(loid)s from urban catchment to waterway in relation to spatial pattern of urban green infrastructures. J. Hazard. Mater. 471, 134381 (2024).

Wang, C. C. et al. Heavy metal(loid)s in agriculture soils, rice, and wheat across China: Status assessment and spatiotemporal analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 882, 163361 (2023).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Evaluation of concentration and characterization of potential toxic elements and fluorine in ambient air dust from Iran’s industrial capital: A health risk assessment using Monte Carlo simulation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 132, 103998 (2024).

Du, H. M. & Lu, X. W. Spatial distribution and source apportionment of heavy metal(loid)s in urban topsoil in Mianyang, Southwest China. Sci. Rep. 12, 10407 (2022).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. The impact of mining on the ecosystem of central Iran’s wetland: A probabilistic approach to assessing ecological risk. Environ. Technol. Innov. 38, 10413 (2025).

Zhao, Z. J. et al. Contamination, sources and health risks of toxic elements in soils of karstic urban parks based on Monte Carlo simulation combined with a receptor model. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 156223 (2022).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Evaluation of the concentration and human health risk of nitrate and potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in melons from a Southern region of Iran: identification of pollution sources. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171702 (2024).

Ghosh, S. et al. Pollution and health risk assessment of mine tailings contaminated soils in India from toxic elements with statistical approaches. Chemosphere 324, 138267 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Determining priority control toxic metal for different protection targets based on source-oriented ecological and human health risk assessment around gold smelting area. J. Hazard. Mater. 468, 133782 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Advanced matter-element extension model and machine learning for source-specific probabilistic health risk assessment of heavy metals/metaloids in soil-rose systems in Kushui, Northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 170, 113017 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Contamination, ecological–health risks, and sources of potentially toxic elements in road–dust sediments and soils of the largest urban riverfront scenic park in China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 8169–8186 (2023).

Xiang, Q. et al. The potential ecological risk assessment of soil heavy metals using self-organizing map. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 156978 (2022).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Machine learning-driven assessment of heavy metal contamination in the impounded lakes of China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Project: Identifying spatiotemporal patterns and ecological risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 135983 (2024).

Lu, X. W. et al. Source-specific probabilistic risk evaluation of potentially toxic metal(loid) s in fine dust of college campuses based on positive matrix factorization and Monte Carlo simulation. J. Environ. Manage. 347, 119056 (2023).

Paatero, P. & Tapper, U. Positive matrix factorization: A non-negative factor model with optimal utilization of error estimates of data values. Environmetrics 5, 111–126 (1994).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0 Fundamentals and User Guide. (2014).

Anaman, R. et al. Identifying sources and transport routes of heavy metals in soil with different land uses around a smelting site by GIS-based PCA and PMF. Sci. Total Environ. 823, 153759 (2022).

Lei, M. et al. Source–specific health risks apportionment of soil potential toxicity elements combining multiple receptor models with Monte Carlo simulation. Sci. Total Environ. 817, 152899 (2022).

Banerjee, S. et al. Assessing pollution and health risks from chromite mine tailings contaminated soils in India by employing synergistic statistical approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 880, 163228 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Source–specific probabilistic contamination risk and health risk assessment of soil heavy metals in a typical ancient mining area. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167772 (2024).

Yang, Y. F. et al. Source-specific risk judgement and environmental impact of potentially toxic elements in fine road dust from an integrated industrial City, North China. J. Hazard. Mater. 458, 131982 (2023).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Novel modelling approach to assess elements contamination in drinking water from Southern Iran. Expo Health. 16, 661–678 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Pollution and source-specific risk analysis of potentially toxic metals in urban soils of an oasis-tourist City in Northwest China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 46, 55 (2024).

Sun, J. X. et al. Determination of priority control factors for the management of soil trace metal(loid)s based on source–oriented health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 423, 127116 (2022).

Yuan, B. et al. Source-oriented probabilistic health risk assessment of soil potentially toxic elements in a typical mining City. J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130222 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. A Monte Carlo simulation-based health risk assessment of heavy metals in soils of an oasis agricultural region in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159543 (2023).

Tang, R. et al. Human activities contributing to the accumulation of high-risk trace metal (loid)s in soils of China’s five major urban agglomerations. Sci. Total Environ. 905, 167218 (2023).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Seasonal variations of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in drinking water and health risk assessment via Monte Carlo simulation and Sobol sensitivity analysis in Southern Iran’s largest City. Appl. Water Sci. 13, 237 (2023).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Trace elements human health risk assessment by Monte Carlo probabilistic method in drinking water of Shiraz, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 20, 3775–3788 (2023).

Jinchang Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Jinchang Statistical Yearbook in 2022 (China Statistics, 2023). (In Chinese).

Lu, Y. et al. Accumulation of heavy metals in native plants growing on mining-influenced sites in Jinchang: a typical industrial City (China). Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 446 (2017).

Xu, S. H. et al. Characteristics and evaluation of heavy metal pollution in a soil-wheat system of an arid oasis city in Northwest China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 271, 115958 (2024).

Lu, R. K. Soil Agrochemical Analysis (China Agriculture, 2000). (In Chinese).

MEEP. Solid waste—Determination of 22 metal elements—Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. (In Chinese). (2016).

MEEP. Solid waste—Determination of Mercury, Arsenic, Selenium, Bismuth, antimony—Microwave Dissolution/atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2014). (In Chinese).

Hong, H. et al. Trace metal pollution risk assessment in urban Mangrove patches: Potential linkage with the spectral characteristics of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Environ. Pollut. 272, 115996 (2021).

Håkanson, L. et al. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Res. 14, 975–1001 (1980).

China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC). The Background Concentrations of Soil Elements in China (Chinese Environment Science, 1990). (In Chinese).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-09/052F. (2011).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Toxicological Review of Hexavalent Chromium. (1998).

Liu, J. W. et al. Multiple pathway exposure risks and driving factors of heavy metals in soil-crop system in a Pb/Zn smelting city, China. J. Clean. Prod. 459, 142523 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Source-specific probabilistic health risk assessment of heavy metals in surface water of the Yangtze river basin. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171923 (2024).

MEEP. Soil environmental quality–risk control standard for soil contamination of development land (GB36600-2018) (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. (In Chinese). (2018).

Li, X. H. et al. Characteristics of distribution and chemical speciation of heavy metals in environmental mediums around Jinchang mining city, Northwest China. Environ. Earth Sci. 64, 1667–1674 (2011).

MEEP. Soil environmental quality–risk control standard for soil contamination of agricultural land (GB 15618–2018) (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. (In Chinese). (2018).

Li, C. Y. et al. Source-specific ecological and human health risk analysis of topsoil heavy metals in urban greenspace: a case study from Tianshui City, Northwest China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 46, 445 (2024).

Liang, L. C. et al. Integrated insights into source apportionment and sourcespecific health risks of potential pollutants in urban park soils on the karst plateau, SW China. Expos. Health. 15, 933–950 (2023).

Paterson, E. et al. Urban soils as pollutant sinks—a case study from Aberdeen, Scotland. Appl. Geochem. 11, 129–131 (1996).

Mirzaei, R. et al. Comparative study of heavy metals concentration in topsoil of urban green space and agricultural land uses. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187, 741 (2015).

Izquierdo, M. et al. Bioaccessibility of metals and human health risk assessment in community urban gardens. Chemosphere 135, 312–318 (2015).

Liu, Z. Y. et al. Prediction of high-risk areas of soil heavy metal pollution with multiple factors on a large scale in industrial agglomeration areas. Sci. Total Environ. 808, 151874 (2022).

Islam, M. S. et al. Human and ecological risks of metals in soils under different land-use types in an urban environment of Bangladesh. Pedosphere 30, 201–213 (2020).

Shi, J. et al. Spatiotemporal variation of soil heavy metals in China: The pollution status and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 871, 161768 (2023).

Zhang, Y. X. et al. Soil mercury accumulation, Spatial distribution and its source identification in an industrial area of the Yangtze delta, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 163, 230–237 (2018).

Fei, X. F. et al. Source analysis and source-oriented risk assessment of heavy metal pollution in agricultural soils of different cultivated land qualities. J. Clean. Prod. 341, 130942 (2022).

Pučko, E. et al. Comparison of elemental composition of surface and subsurface soils on national level and identification of potential natural and anthropogenic processes influencing its composition. J. Geochem. Explor. 258, 107422 (2024).

Wang, Y. Z. et al. Spatial distribution and source analysis of heavy metals in soils influenced by industrial enterprise distribution: case study in Jiangsu Province. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 134953 (2020).

Ao, M. et al. Chromium biogeochemical behaviour in soil-plant systems and remediation strategies: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127233 (2022).

Sharma, P. et al. Chromium toxicity and tolerance mechanisms in plants through cross-talk of secondary messengers: An overview of pathways and mechanisms. Environ. Pollut. 320, 121049 (2022).

Fei, X. F. et al. Different nongrain activities affect the accumulation of heavy metals and their source-oriented health risks on cultivated lands. Environ. Res. 251, 118642 (2024).

Jiang, H. H. et al. An integrated approach to quantifying ecological and human health risks from different sources of soil heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 701, 134466 (2020).

Ahamad, A. et al. Potentially toxic elements in soil and road dust around Sonbhadra industrial region, Uttar Pradesh, India: source apportionment and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 202, 11685 (2021).

Penteado, J. O. et al. Health risk assessment in urban parks soils contaminated by metals, Rio Grande City (Brazil) case study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111737 (2021).

Ding, J. J. & Hu, J. M. Soil heavy metal pollution and health risk assessment around Wangchun industrial park, Ningbo, China. J. Soils Sediments. 24, 2613–2622 (2024).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)-Generic Table (2024).

Huang, R. et al. Source-specific health risk analysis on particulate trace elements: coal combustion and traffic emission as major contributors in wintertime Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10967–10974 (2018).

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Gansu Province (No. 24JRRA530) and the Project of Higher Education Innovation Foundation of Gansu Province (No. 2025 A-161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jun Li and Fei Zang wrote the main manuscript text; Xu Li, Xi-Sheng Tai, Xin-Ying Tuo, Fa-Yuan Zhou, and Yi-Jing Rong prepared all the figures and tables in the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants or animals. All of the authors have read and approved the paper for submission of publication. The manuscript in part or in full has not been submitted or published anywhere.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Li, X., Tai, XS. et al. Machine learning-assisted source identification and probabilistic ecological-health risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s in urban park soils. Sci Rep 15, 17451 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02307-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02307-1