Abstract

Current literature lacks comparative studies on the effects of solar and open sun drying (OSD) methods on the drying characteristics and color properties of henna leaves. Furthermore, energy and exergy analyses, techno-environmental assessments, and sustainability evaluations remain uninvestigated for hybrid photovoltaic-thermal (PVT)-based active direct solar dryer (ADSD) in this context. Filling these research gaps through systematic study is critical to advancing sustainable drying technologies for agricultural products. The current study used ADSD and OSD to dry henna leaves, with three-layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm. The obtained results showed that the drying time was between (14 and 16 h) and (15 and 19 h) for the ADSD and OSD, respectively. The lower color change (ΔE) value was observed with samples dried on OSD at a layer thickness of 2 cm, followed by the samples dried on ADSD at a layer thickness of 6 cm. The energy efficiency of the ADSD was ranged between 9.11 and 41.66%, and the highest drying efficiencies were 14.97%, 31.98%, and 34.57% at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively. The exergy outflow, exergy loss, and exergy efficiency of ADSD were in a range of (3.13–260.16 W), (218.64–1396 W), and (1.42–16.36%), respectively. Also, the improvement potential (IP) was in the range of 2.16–11.92 W, while the sustainability index (SI) and waste exergy ratio (WER) varied from (1.01 to 1.20) and (0.79 to 0.94), respectively. In addition, energy payback time (EPBT) was 6.89, 2.71, and 1.77 years at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm of henna leaves, respectively. Additionally, average annual CO₂ emissions in lifetime values for ADSD were 133.46 kg/year. In contrast, net CO₂ mitigations in lifetime values for ADSD were found to be 13.45, 40.42, and 63.90 tons, at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm of henna leaves, respectively. The study demonstrates that the ADSD significantly reduces drying time compared to OSD for henna leaves, particularly at 6 cm thickness, which also improves drying efficiency and sustainability. ADSD exhibits lower energy payback time (1.77 years) and higher CO₂ mitigation (63.9 tons) at 6 cm. Despite some color retention advantages in OSD, ADSD proves more energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable, making it a viable solution for agricultural drying.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world is facing a critical shortage of fossil fuels, the non-renewable energy sources that have powered industrialization and economic growth for over a century1. As reserves deplete and extraction becomes more challenging, the environmental and economic costs of relying on coal, oil, and natural gas are increasingly unsustainable. Fossil fuel combustion is a major contributor to climate change, air pollution, and resource depletion, prompting an urgent need for cleaner, renewable alternatives2,3. Solar energy has emerged as a leading solution to this global crisis. Harnessing the sun’s abundant and inexhaustible energy, solar power offers a sustainable way to meet growing energy demands while reducing greenhouse gas emissions4,5. Among the innovative applications of solar energy are solar dryers (SDs), which provide an eco-friendly alternative to conventional drying methods that rely on fossil fuels. SDs use sunlight to dehydrate agricultural products, preserving food and reducing post-harvest losses without emitting harmful pollutants6,7. They are particularly beneficial in rural and off-grid areas, offering a cost-effective and energy-efficient solution for farmers and communities. By transitioning to solar energy and technologies like SDs, we can address the fossil fuel shortage, combat climate change, and promote sustainable development, ensuring a cleaner and more resilient future for generations to come8,9.

Drying has been utilized for many years as a method to preserve agricultural, marine, and herbal items10. It has multiple advantages, such as preserving food flavor, nutrition, and quality, improving appearance, prolonging shelf life for consumer use, and minimizing packaging and shipping requirements11. The elimination of moisture during the drying process can also inhibit the growth of mold and germs, thereby preserving the food. In poor nations, OSD is a prevalent, efficient, and cost-effective technique employed for the drying and preservation of agricultural products12. The external drying factors, including heat input, moisture content, temperature, and drying airflow rate, cannot be regulated, leading to extended drying periods or suboptimal drying rates. Additional disadvantages of the OSD approach encompass the deterioration of product quality due to wind-blown dirt, precipitation, insects, and animals13,14. In the solar drying of agricultural products, moisture is eliminated by air heated by solar energy, with a temperature range of 50 to 60 °C15,16. Solar drying under regulated temperature and moisture removal rates guarantees optimal drying and superior product quality17.

Solar drying technology has been significantly improved by researchers through various innovations, including natural and forced air circulation systems, as well as the integration of auxiliary heating sources such as electrical and fossil fuel-based systems. These enhancements aim to optimize drying efficiency, reduce moisture content, and preserve the quality of agricultural products. Based on their design and operational mechanisms, SDs are broadly classified into three main types: direct, indirect, and hybrid SDs18,19. 1. Direct SDs consist of a transparent drying chamber, typically constructed with glass or plastic, where fresh produce is exposed directly to solar radiation. The sun’s rays penetrate the transparent cover, heating the product and facilitating moisture evaporation20,21. 2. Indirect SDs employ an opaque drying chamber connected to a solar collector (SC). In this system, convective heat transfer occurs as hot air passes over the produce, removing moisture without direct solar exposure22,23. 3. Hybrid SDs combine the principles of both direct and indirect drying, leveraging simultaneous solar radiation and convective heating to enhance drying performance22,24. Furthermore, based on airflow mechanisms, SDs can be categorized into natural convection (passive mode) and forced convection (active mode) dryers22,25. a. Forced Convection SDs (Active Mode) utilize motorized fans or blowers to actively circulate heated air within the drying chamber, ensuring uniform temperature distribution and faster drying rates. b. Natural Convection SDs (Passive Mode) rely on buoyancy-driven airflow, where temperature differences between the heated air inside the chamber and the cooler ambient air create natural circulation16,26,27,28. Each type of solar dryer offers distinct advantages depending on climatic conditions, energy availability, and the specific requirements of the agricultural product being dried. Recent advancements continue to explore hybrid configurations and energy-efficient designs to further improve drying performance and sustainability.

18,1920,2122,2322,2422,2526Numerous researchers have developed various PVT-based solar dryers to enhance the drying efficiency of agricultural crops, integrating renewable energy with thermal applications. For instance, Gupta et al.29 analyzed a hybrid PVT solar air dryer for green chilies, demonstrating improved thermal efficiency and reduced drying time. Tiwari et al.30 conducted a comparative study to identify the most suitable PV technology for PVT drying systems, evaluating both economic and environmental feasibility. Bayrak et al.31 introduced a novel PVT dryer with a sustainable control approach for apple slices, optimizing energy use and product quality. Further advancements include the work of Veeramanipriya and Sundari32, who assessed a hybrid PVT solar dryer for cassava, highlighting its superior performance over conventional drying methods. Tiwari et al.33 also explored a PVT mixed-mode greenhouse solar dryer, enhancing drying uniformity and energy efficiency. In a more technologically advanced approach, Elwakeel et al.34 designed an IoT-enabled PVT-integrated solar dryer for date fruits, incorporating real-time quality monitoring and control. Additionally, Elwakeel et al.34 investigated the drying kinetics and thermo-environmental performance of a PVT-operated tracking indirect solar dryer for tomato slices, emphasizing energy savings and sustainability. These studies collectively highlight the versatility, efficiency, and sustainability of PVT-based solar dryers in agricultural applications, paving the way for optimized drying technologies in food preservation.

Energy and exergy analysis are critical tools for evaluating the performance and sustainability of SDs35,36. Energy analysis focuses on quantifying the total energy input and output, helping to assess the efficiency of the drying process. However, it does not account for the quality or usability of energy, which is where exergy analysis becomes essential37,38. Exergy analysis evaluates the useful work potential of energy, identifying inefficiencies and losses within the system38,39. By combining these two approaches, we gain a comprehensive understanding of how effectively a SD converts solar energy into usable heat for drying39,40. Energy and exergy analysis help optimize these factors, ensuring maximum efficiency and minimal WER. This is crucial for reducing energy consumption, lowering operational costs, and minimizing environmental impact. By improving the sustainability of SDs, these analyses contribute to global efforts in promoting renewable energy and achieving sustainable development goals41,42. Numerous prior researchers have examined the energy and exergy of various types of SDs for the dehydration of multiple agricultural crops, such as Mugi and Chandramohan43, conducted an energy and exergy analysis of okra drying in an indirect SD utilizing both forced and natural convection methods. The mean SC and drying efficiencies were superior in forced convection (74.98% and 24.95%) relative to natural convection (61.49% and 20.13%). The exergy outflow of SD ranged from 1.04 to 46.85 W in forced convection mode and from 1.13 to 50.94 W in natural convection mode. The average exergy efficiencies for SC in forced convection were 2.03%, but in natural convection, they were 2.44%. In forced convection, the IP ranged from 0.0095 to 10.51 W, whereas the SI and WER varied between 0.06 to 17.05. Selimefendigil et al.44, examined the effects of incorporating nanoparticles into a paraffin-based latent heat thermal energy storage system on the thermal and drying characteristics of a greenhouse dryer. The average exergy efficiency metrics were determined to be 3.45% and 2.74%, respectively, in tests conducted at a flow rate of 0.016 kg/s for the greenhouse dryers with and without nanoparticles. The values recorded were 3.01% and 2.40%, respectively, in the test conducted at a flow rate of 0.010 kg/s. Ekka and Muthukumar45, examined the efficacy of a mixed-mode SD incorporating two double-pass solar air collectors in succession for the desiccation of cluster figs. The statistics gathered indicated that the overall exergy efficiency ranged from 18.8% to 41.4%. IP research reveals that an increase in air mass flow rate correlates with a diminished possibility for exergy loss reduction. The SI varies from 1.26 to 1.71, with elevated values linked to increased exergy efficiency. Şevik et al.46, developed and evaluated a double-pass solar air dryer and an infrared-assisted double-pass solar air dryer. Energy efficiency ranged from 1.15% to 26.46%. Chowdhury et al.47, conducted an energy and exergy analysis of solar drying jackfruit leather using a solar tunnel drier. The energy efficiency of the collector and dryer ranged from 27.45% to 42.50% and from 32.34% to 65.30%, respectively, corresponding to variations in solar radiation from 100 to 600 W/m2. The total energy efficiency of the SD was 42.47%. The exergetic efficiency of the collector ranged from 32 to 69%, whereas the average exergetic efficiency of the dryer was 41.42%. Hassan et al.35, examined the energetic and exergetic efficiency of a gas engine-driven combined heat and power system. The system exhibits energy and exergy efficiencies of 29.95% and 23.12%, respectively. The system’s SI is determined to be 1.30.

Additionally, environmental analysis of SDs is essential for assessing their ecological impact and sustainability. Where SDs, which use renewable energy to preserve agricultural products, offer a cleaner alternative to conventional drying methods that rely on fossil fuels28,44. By evaluating factors such as carbon emissions, energy consumption, and resource use, environmental analysis helps identify the benefits and potential drawbacks of solar drying systems. This analysis ensures that SDs contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, minimizing WER, and promoting sustainable practices28,48.

Current literature lacks comparative studies on the effects of solar and natural drying methods on the drying characteristics and color properties of henna leaves. Furthermore, energy and exergy analyses, techno-environmental assessments, and sustainability evaluations remain uninvestigated for hybrid PVT-based ADSD in this context. where most researches on henna are oriented towards its chemical composition49,50,51, its anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory52,53, antipyretic and analgesic effects52, while only some researches on henna are oriented towards drying process, such as, Bennamoun et al.54, studied the effect of forced convective solar drying on the biological activities, Bennamoun et al.55, explored solar drying of henna and its effect on the bioactivities, Bennaceur et al.56, studied the effect of ultrasound on henna leaves drying and extraction of lawsone. Filling these research gaps through systematic study is critical to advancing sustainable drying technologies for agricultural products. So, this research paper aims to investigate the energy, exergy and techno-environmental performance analysis and sustainability indicators of a hybrid PVT-based active direct SD while drying henna leaves and compare the obtained data for moisture content, drying time, and color specifications with traditional drying methods in open air.

Materials and methods

Experiment setup

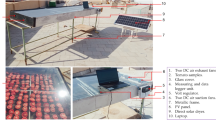

Henna leaves were purchased from local markets in Aswan, Egypt. Then, the leaves were transported to the Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources at Aswan University under an average temperature of 25 °C. The henna samples were then stored in plastic bags at 5 ± 1 °C until the drying experiments began. Fresh henna leaves were spread in three-layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm. Two drying methods were employed in the study: Using ADSD and an OSD for each thickness level, three identical tests were done using both the ADSD and the traditional OSD methods. This comprehensive experimental design resulted in a total of 18 drying trials (3 thickness levels × 2 drying methods × 3 replicates), ensuring robust statistical validity of the results. All drying tests for drying the fresh henna leaves were carried out on the roof of the Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Aswan University, Egypt, in January 2025. All drying experiments were conducted at a continuous air speed of 0.05 m/s above henna leaves. Based on the primary experiments without load, the fan speed was set to 0.05 m/s to increase the drying temperature up to 55 °C, which aligns with the recommended range of 40–60 °C for leafy agriproducts as established in prior studies57. This airflow rate ensures that over 50% of the drying process occurs within this recommended range of 40–60 °C, balancing energy use and product quality. Figure 1 illustrates both fresh and dried henna leaves.

Description of the ADSD

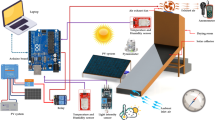

Figure 2 illustrates the main components of the developed ADSD. The dimensions of the ADSD are 300 cm in length, 100 cm in width, and 20 cm in depth. A glass cover, measuring 3 mm in thickness, covered the ADSD. The absorber plate is made from corrugated black aluminum plate and insulated with thermal wool with 3 cm in thickness from the three sides. The ADSD has three drying trays; each of them has a dimension of 100 cm in length and 100 cm in width (The equations and calculations used for dryer design—accounting for local ambient conditions and target drying temperatures—were derived from a previously published study58. And it was integrated with four DC brushless fans (12 V and 0.20 A, China) to distribute the air evenly around the henna leaves to create a homogeneous moisture content throughout the drying trays. Where two DC fans were used to force the ambient air to the ADSD, while the other DC fans were used to exhaust the hot air from the ADSD to the outside. The ADSD was integrated with an IoT-based measuring circuit for measuring both air temperature and relative humidity of air inside and outside the ADSD. The measuring unit consists of an Arduino board (model: Uno, China), a dry temperature and humidity sensor (model: DHT-22, China), and a micro-SD card reader module (data logger, China). The ADSD was operated with a photovoltaic (PV) system, as shown in Fig. 2. The PV system consists of a PV panel (100 W, India) and a voltage converter (12–5 V, China). Figure 3 also illustrates the placement of DHT sensors within the ADSD, which measure temperature and relative humidity at two critical locations: (1) near the air intake fans (Tin), where fresh air enters the system, and (2) at the exhaust fans (Tout), where the temperature and humidity of the outgoing hot air are monitored before it exits. This dual-point measurement ensures accurate tracking of environmental conditions across the airflow pathway.

Quality attributes dried henna leaves

Moisture content

The moisture content (\({\mu }_{w}\)) of henna leaf samples was estimated by oven drying the henna leaves at 105 ± 1 °C until reaching equilibrium moisture content (constant weight), according to AOAC methodology59, using Eq. (1)4,60.

where, \({W}_{w}\) and \({W}_{d}\) is the wet and dry weight of henna leaf sample, respectively in g.

Color analysis

Color analysis of dried henna leaves is crucial for assessing quality, as color directly correlates with pigment concentration, particularly lawsone, which determines dye efficacy. Drying methods impact color retention, influencing market value and consumer preference. Solar drying often preserves vibrant green hues, indicating better quality, while OAD may lead to discoloration due to oxidation. Analyzing color variations helps optimize drying techniques, ensuring superior product quality for cosmetic, medicinal, and artistic applications. During the current study, a colorimeter (model: CR-410, Konica Minolta Sensing Americas, Inc., USA) was used to measure the color of fresh and dried henna leaf samples as recommended in previous studies61,62,63.

Hue angle (H) of fresh and dried henna leaf samples

The hue angle (H) is a color attribute in the HSL/HSV color models, representing the dominant wavelength of a color on a circular scale (0° to 360°). It defines the color’s position on the color wheel, shown in Fig. 464.

Color wheel diagrams adopted from Dini et al.65.

Color change (\(\Delta\) E*) of dried henna leaf samples

Measuring color change (\(\Delta\) E*) involves quantifying differences in color attributes like hue, saturation, and brightness using tools such as spectrophotometers or colorimeters. It is essential in industries like manufacturing, food, and textiles to ensure consistency, quality, and compliance with standards. Equation (3) was used to calculate the total color change (E*)66.

where: L is the lightness, a is the redness, b is the yellowness;\((\) a**, b** and L**) are the value of (a*, b*, and L*) after the drying process.

Chroma (\({C}^{*}\)) of fresh and dried henna leaf samples

Chroma (\({C}^{*}\)) refers to the purity or intensity of a color, indicating how vivid or dull it appears compared to a neutral gray. High chroma colors are vibrant and saturated, while low chroma colors appear muted. It is a key attribute in color models like Munsell and CIELAB. Chroma was calculated using Eq. (4).

Energy analysis of the developed ADSD

The present work regarded the ADSD as steady flow devices, which were examined utilizing the concepts of mass and energy conservation for steady flow32,67,68. According to the principle of mass conservation, the mass flow rate remains constant, indicating that the inflow of air equals the outflow of air from the system.

where, \({\dot{m}}_{ai} \text{ and } {\dot{m}}_{ao}\) are the inlet and outlet mass flow rate of air, respectively.

According to energy conservation principles, the rate of energy transfer by work done (\(\dot{W}\)), heat (\(\dot{Q}\)) and mass (\({\dot{m}}_{ai}\)) into the ADSD, equal to the rate of energy transfer by work, heat and mass coming out of the ADSD (\({\dot{m}}_{ao}\)), according to Eqs. 6 and 769,70,71,72,73.

where, \({h}_{ai} \text{ and } {h}_{ao}\) is the input and output enthalpy of air, \({v}_{ai} \text{ and } {v}_{ao}\) is the input and output air velocity, and \({z}_{i} \text{ and } {z}_{o}\) represent input and output height of datum air.

According to the ADSD, the work done (\(\dot{W}\)) equal zero, the change in height (\({z}_{i}-{z}_{o}\)) and the value of \(\left(\frac{{v}_{ai}^{2}}{2}-\frac{{v}_{ao}^{2}}{2}\right)\) are very small and can be neglected.

From Eqs. 5 and 6, at steady flow mass to the ADSD and based on the principles of energy conversion, Eqs. 8 and 9, can be generated.

where, \({\dot{Q}}_{u}\) is the useful heat supplied by the ADSD, \({\dot{Q}}_{in}\) is the heat input to the ADSD and \({\dot{Q}}_{ls}\) is the heat lost from the ADSD. The heat input to the ADSD is calculated using Eq. (10).

where, \({I}_{s}\) is solar radiation flux in W/m2 and \({A}_{\text{ADSD}}\) is the area of ADSD in m2 (equal 3 m2).

The useful heat (\({\dot{Q}}_{u}\)) supplied by the ADSD was calculated using Eq. (11)74.

where, \({C}_{pa}\) is the specific heat of air in kJ/kg.K, \({T}_{co}\) and \({T}_{ci}\) are the outlet and inlet temperatures of air, respectively.

The efficiency of the ADSD (\({\eta }_{en}\)) is the ratio of useful heat supplied by ADSD (\({\dot{Q}}_{u}\)) to the heat input to the ADSD (\({\dot{Q}}_{in}\))75,

The specific moisture extraction rate (SMER) is the ratio of the amount of moisture evaporated from different henna leaf samples (\({m}_{w}\)) to the total energy input by solar radiation to the ADSD (\({E}_{in}\)) and given by Eq. (13), according to Wang et al.24:

where, \({m}_{w}\) is the mass difference between fresh and dried henna leaf sample (\({m}_{i}-{m}_{f}\)), and \({t}_{d}\) is the total drying time in hours.

The specific energy consumption (\(SEC\)) for drying henna leaf samples dried using the ADSD is an inversion of SMER. The SEC for drying refers to the amount of energy required to remove a unit mass of moisture from a material73,76,77. It is typically expressed in kWh/kg of water evaporated. Lower SEC indicates higher energy efficiency, making it a key metric for optimizing drying processes and reducing operational costs. The SEC was calculated using Eq. 1578.

Drying efficiency of the ADSD (\({\eta }_{en, ADSD}\)) refers to the effectiveness with which the dryer uses solar energy to remove moisture from a henna leaf sample. It is the ratio of energy utilized for moisture evaporation to the total solar energy input. Higher drying efficiency indicates better performance, reducing energy waste and improving sustainability. The drying efficiency was estimated using Eq. 1647.

where, L is the latent heat of vaporization of water (2260 kJ/kg.k).

Exergy analysis

Exergy for solar drying refers to the maximum useful work potential of solar energy utilized in the drying process, considering its quality and ability to perform effective moisture removal. It evaluates the efficiency of converting solar radiation into useful thermal energy for drying, accounting for environmental conditions and system irreversibility. Exergy analysis helps optimize solar dryers by minimizing energy losses and improving sustainability. The exergy study of the thermal system is predicated on the second law of thermodynamics. The energy per unit mass of any system is the aggregate of internal energy (\(u\)), entropy (\(s\)), flow work, momentum energy, gravitational energy, chemical energy (\(ch\)), and radiation energy79,80, computed using Eq. (17):

The drying process is typically considered a steady-flow process. Factors such as velocity, gravitational, chemical, and radiation energy are neglected. Radiation energy is ignored due to the small temperature difference between the dryer and the surrounding environment. Additionally, changes in system pressure and the exergy loss of the product are also not taken into account80. Based on the above assumptions, Eq. (17) is transformed into Eq. (18):

where, \({T}_{0}\) is atmospheric temperature.

Exergy analysis of the ADSD

Exergy analysis of the ADSD refers to evaluating the maximum useful work potential of solar energy captured by the ADSD, considering energy quality and system efficiency. It assesses how effectively the ADSD converts solar radiation into usable thermal energy, accounting for irreversibility and losses. This analysis helps optimize the ADSD’s performance by identifying inefficiencies and improving energy utilization for applications like drying. Exergy balance for ADSD is given by Eq. (19), according to Mugi et al.80,

where, \({\dot{Ex}}_{in, SC}\) is the exergy inflow, \({\dot{Ex}}_{out, SC}\) is the exergy outflow and \({\dot{Ex}}_{ls, SC}\) is the exergy loss.

The exergy inflow (\({\dot{Ex}}_{in}\)), associated with solar radiation falling on surface of the ADSD, and can be expressed as shown in Eq. (20), as mentioned by Bait81.

where, \({T}_{s}\) is the sun temperature (6000 K) and \({\dot{Q}}_{in, abs}\) is the solar energy falling on absorber plate in W, and it was calculated according to Eq. (21)80,

where, \(\alpha\) \(\text{and }\tau\) are the absorptivity (0.95) and transmissivity of glass cover (0.88), respectively82.

Exergy outflow for the ADSD (\({\dot{Ex}}_{out}\)), refers to the usable energy output available after accounting for losses and irreversibility. It represents the maximum work potential of the thermal energy transferred by the ADSD to the system, such as for heating of air. Higher exergy outflow indicates better efficiency and effective utilization of solar energy. The (\({\dot{Ex}}_{out, SC}\)) was estimated using Eq. (22)47.

The exergy loss (\({\dot{Ex}}_{ls}\)) can be evaluated from irreversibility and it is given by Eq. (23), as reported by Akpinar83.

The exergy efficiency of ADSD is obtained using Eq. (24)47,79.

Exergy sustainability indicators

Exergy sustainability indicators—specifically the Improvement Potential (IP), Waste Exergy Ratio (WER), and Sustainability Index (SI)—quantify irreversibility and exergy losses within a process relative to a given exergy input. These metrics enable a more rigorous assessment of thermodynamic performance. As exergy losses increased, the IP and WER exhibited an upward trend, while the SI declined. The IP reflects the system’s potential for optimization, highlighting areas where efficiency can be enhanced. The WER represents the proportion of exergy lost per unit of input exergy, serving as a direct measure of thermodynamic waste. Meanwhile, the SI provides insight into the system’s operational longevity, with higher values indicating greater sustainability. Collectively, these indicators offer critical insights into irreversibility, thermodynamic efficiency, and the overall sustainability of the ADSD. By analyzing these metrics, an optimized drying system can be designed by minimizing irreversibility during the drying process71. The calculations for IP, WER, and SI are derived from Eqs. (25)–(27)80,84.

Environment analysis of the ADSD

Embodied energy (EE)

The energy used to manufacture the ADSD and PV system is referred to as EE. All the energy inputs used in manufacture the ADSD are taken into account when calculating the coefficient of EE. The EE of the ADSD and PV system were estimated according to Eq. (28)85. Table 1 shows the EE of the ADSD and PV system.

Energy payback time (EPBT)

EPBT of the ADSD and PV system was determined using Eq. (29) and refers to the time required for the dryer to generate the same amount of energy that was used in its production, transportation, and installation86,89:

where annual energy output from the ADSD can be calculated using Eq. (30)90,91:

where, \({m}_{ev}\) is the total water removed from henna samples, \(L\) is the latent heat of vaporization.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions

By taking coal-based power production into account, we can calculate the yearly CO2 emissions of an ADSD. Usually CO2 emissions from coal-based power production are understood to be 0.98 kg/kWh of CO230,86, and it can be calculated according to Eq. (31).

Equation (31) is developed into Eq. (32), considering distribution and transmission (Ltd) and losses from domestic appliances (Lda) related to electricity generated from the coal-based power production44.

Equation (33) is generated from Eq. (32) by assuming the values of \({L}_{td}\) and \({L}_{da}\) as 0.4 and 0.2, respectively48,92.

CO2 mitigation

The CO2 mitigation per lifetime of the ADSD and PV system can be estimated using Eq. (34), as mentioned by Kumar et al.90:

Uncertainty analysis

The measurement uncertainties for critical drying parameters were quantified using Eq. 35, yielding values of 0.32% for temperature, 0.28% for relative humidity, 0.24% for wind speed, and 0.13% for solar radiation. Propagating these individual uncertainties through the system efficiency calculations resulted in a combined uncertainty of ± 2% for the overall dryer performance evaluation. This low cumulative uncertainty demonstrates that, despite inherent measurement limitations, the solar drying system maintains robust operational reliability. The marginal propagation of errors further confirms the system’s resilience under real-world operating conditions, validating its practical effectiveness for agricultural drying applications.

Results and discussions

Moisture content and sample weight of henna leaves at different layer thicknesses using both drying systems

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the weight loss of dried henna leaf samples at different layer thicknesses. The initial sample weights of fresh henna leaf samples were 3000 g, 6000 g, and 9000 g for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm. During the experiments, these samples were uniformly disrupted above three trays, each of them having a dimension of 1.0 m in length and 1.0 m in width. The final weights of different samples dried using the ADSD were 1270.9, 2533.8, and 3805.9 g, for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively. The final weights of various samples dried in open air were 1265.9, 2518.5, and 3771.5 g, respectively, for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm. Also, the henna samples dried with ADSD reached the equilibrium moisture content faster than the other OSD dried samples. The drying time varied significantly depending on the layer thickness and drying method. For the ADSD samples, layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm required drying times of 14, 15, and 16 h, respectively. In contrast, the OSD samples exhibited longer drying durations, taking 15, 17, and 19 h for the same respective thicknesses. This demonstrates that the ADSD consistently outperformed traditional open sun drying, with the efficiency gap widening as layer thickness increased. OSD relies solely on ambient sunlight and wind to evaporate moisture from agricultural produce, making the process highly dependent on weather conditions and inherently uncontrollable. In contrast, the ADSD employs an enclosed drying chamber with a transparent glass cover to efficiently trap solar radiation, while integrated vents or fans optimize airflow. This controlled environment accelerates moisture removal, ensures uniform drying, and protects the produce from dust, pests, and other external contaminants—significantly improving both efficiency and product quality compared to traditional OSD.

Figure 6 illustrates the combined effects of drying method and layer thickness on the moisture content reduction of henna leaves. The leaves had an initial moisture content of 59.1% (w.b.). When processed using the ADSD, all samples achieved significantly reduced moisture levels, with final averages of 3.51%, 3.21%, and 3.34% for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm respectively. Interestingly, the OSD method yielded even lower final moisture contents of 3.13%, 2.62%, and 2.46% for the corresponding layer thicknesses. This counterintuitive result suggests that while ADSD offers controlled and consistent drying conditions, the extended exposure time in OSD may lead to more complete moisture removal, particularly at greater layer thicknesses.

Color analysis of henna leaves dried using both drying systems

Color analysis of henna leaves is crucial for determining quality, especially in natural dye and cosmetic applications. It helps assess changes in color attributes (L*, a*, b*) due to drying methods and thickness, ensuring consistency and effectiveness. Proper color retention indicates better preservation of active compounds, enhancing the product’s market value and consumer appeal. The color attributes (L*, a*, b*) of fresh and dried henna samples were measured and illustrated in Fig. 7. The data illustrated in the same figure showed that the values of color attributes (L*, a*, b*) for both drying methods and layer thicknesses were very close, because both drying methods were dried under solar rays directly, but the lightness (L*) of dried samples using the ADSD was very close to the fresh samples.

The hue angle is a measure used in color science to describe the color tone or shade in the CIELAB color space. The a* (green–red axis) and b* (blue-yellow axis) values calculate it, representing the dominant wavelength of a color. The hue angle ranges from 0° to 360°: 0° or 360° is red, 90° is yellow, 180° is green, and 270° is blue. A higher hue angle indicates a shift toward yellow or blue, while a lower angle indicates a shift toward red or green. It helps in precisely defining and comparing colors. The hue angle of all dried samples lies in the green area and ranges between 108.49 and 113.18, while the dried sample in OSD ranges between 111.23 and 114.39. Additionally, chroma angles for dry samples are very close. This means that the use of ADSD had no noticeable effect on the color characteristics of dried henna leaves, but it had a noticeable effect on reducing drying time and maintaining the quality of the leaves after drying. When dried henna leaves were treated with ADSD in a layer that was 6 cm thick (Fig. 8), the color angle was very similar to that of the fresh samples. Also, the color change (ΔE) of dried henna samples was calculated to describe the value of color change after drying compared with the fresh samples. A higher E value indicates a more noticeable color change, while a lower E value suggests a minimal or no visible difference. Figure 8 shows that the samples dried on OSD with a 2 cm layer thickness had the lowest ΔE value. The samples dried on ADSD with a 6 cm layer thickness came in second.

Weather conditions during the drying experiments

Figures 9 and 10 illustrate the fluctuations of solar radiation, ambient air temperature, and the intake and output air temperatures of the ADSD on a typical day throughout the solar drying process of henna leaves. Henna leaves were desiccated for a continuous duration of 9 h, from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., in ADSD. The range of solar radiation flux was 93 to 687 W/m2. The peak solar radiation reached 687 W/m2, while the maximum heat input to the ADSD was 2061 W, with both the highest solar radiation and heat input recorded around 12 p.m. The ADSD’s temperature significantly exceeded the ambient air temperature, with an average exit temperature of 56 °C at 12 p.m. and an average temperature increase of 24 °C.

Energy analysis of the ADSD

Figure 11 shows the energy analysis of the ADSD, where the input energy, useful energy, energy loss, and efficiency were calculated hourly based on the solar radiation flux and the difference between the air temperature at the input and output of the ADSD. Input energy to the ADSD refers to the total solar radiation received by the ADSD, and it was measured in W.h/m2. It depends on solar irradiance, solar collected area, and orientation. During the current study, the input energy ranged between 279 and 2061 W.h/m2. Figure 11 shows the useful energy supplied by ADSD (estimated using Eq. (11)) while drying henna leaves. The useful energy was between 25.42 and 834.79 W, depending on the mass flow rate and solar radiation, as shown in Fig. 11. It is observed that useful energy is more because DC fans run continuously. The efficiency of ADSD was found (using Eq. (12)) and shown in Fig. 11. Due to its relationship with useful energy, the efficiency increased until noon and then decreased at 5 p.m. The efficiency was in the range of 9.11% and 41.66%. The maximum efficiency was observed at noon because of higher solar radiation. The obtained efficiency was better than (19.7%—12.9%)93; Hassan et al.35 reported that the overall system has an energy efficiency of 29.95%. According to Chowdhury et al.47, the energy efficiency changed from 27.45% to 42.50% when the amount of solar radiation changed from 100 W/m2 to 600 W/m2.

Figure 12 shows the drying efficiency of the ADSD. Drying efficiency of an ADSD measures how effectively it converts solar energy into usable heat for drying. It is calculated as the ratio of energy used for moisture removal to the total energy input and it was estimated using Eq. (15). Similar to ADSD efficiency, it is also higher at noon because of higher solar radiation. The drying efficiency varied according to the layer of henna leave. As shown in Fig. 12, the highest drying efficiency was 14.97%, 31.98%, and 34.57% at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively. Where the drying efficiency decreased with decreasing the layer thickness of henna leaves. As a result of the stability of the intensity of solar radiation in both cases, the reason is due to the increase in the amount of water evaporating from the henna samples with a thickness of 6 cm compared to the rest of the other samples. Also, the drying efficiency decreased with time due to decreasing water loss from the henna leave samples. Mugi and Chandramohan80 reported that the drying efficiency ranged between 20.13% and 23.94%. Also, Hassan et al.35, stated that the overall drying efficiency was 29.95%. Chowdhury et al.47, reported that the overall drying efficiency of the ADSD was 42.47%.

The specific moisture extraction rate (SMER) and specific energy consumption (SEC) of the dryer for varying layer thicknesses of henna leaves dried by the ADSD were calculated using Eqs. (13) and (15) and are presented in Table 2. Table 2 also presents the moisture loss from henna leaves, drying duration, and solar radiation intensity. SMER assesses the efficacy of a drying system by quantifying the moisture extracted per unit of energy utilized, generally represented in kg/kWh. A superior SMER signifies enhanced drying efficiency, demonstrating optimal energy utilization. Enhancing SMER is essential for minimizing energy expenses and augmenting the sustainability of drying procedures. The energy inflow was derived from the solar radiation statistics presented in Table 2. The calculated SMER values were 0.321, 0.777, and 1.145 kg/kW.h for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively. Increasing the layer thickness from 2 to 6 cm resulted in an approximate 256.7% rise in the SMER value.

The estimated SMER of the current configuration surpassed that of Kesavan et al.78 (0.18 kg/(kW-h)) during the drying of potato slices, Mugi et al.80 (0.41 and 0.445) during the drying of okra, and Ndukwu et al.94, whose WER values varied between 0.38 and 0.55. The acquired SMER aligns with Selimefendigil et al.44, (1.01–1.20 kg/kWh) in enhancing the drying efficiency of a greenhouse dryer by the utilization of a nano-embedded latent heat storage unit.

The SEC specifies the energy required per kilogram of moisture extracted from the materials during drying. The energy used to eliminate moisture is greater when drying henna leaves at a thickness of 2 cm compared to a thickness of 6 cm. The SEC at a layer thickness of 2 cm was 3.114 kW.h/kg, while at a layer thickness of 6 cm, it was 0.873 kW.h/kg. The specific energy consumption (SEC) was 4.3 (kW-h)/kg in the research conducted by Ndukwu et al.94, and 8.849 (kW-h)/kg in the study of Rabha et al.95.

Exergy analysis of the ADSD

Figure 13 illustrates the temporal change of exergy inflow, exergy outflow, exergy loss, and exergy efficiency for ADSD, derived utilizing Eqs. (20), (22), (23) and (24). Exergy input, exergy outflow, and exergy loss are directly proportional to solar radiation, as illustrated in Fig. 13. Consequently, these parameters rose from morning until midday and subsequently began to decline in the afternoon. The exergy influx was calculated based on the solar temperature (Eq. (21)). The exergy inflow was assessed relative to ambient air temperature, ranging from 221.8 to 1635.41 W during the tests, with the peak value recorded at 12 p.m. The exergy outflow ranged from 24.48 W to 260.16 W. The exergy loss varied between 218.64 and 1395.99 W. Exergy losses are greater at midday due to the elevated solar radiation flux measured during that time (Fig. 13). The average exergy inflow, exergy outflow, and exergy loss were determined to be 1015.94 W, 132.31 W, and 833.19 W, respectively. The exergy efficiency with time was determined using Eq. (24) and is illustrated in Fig. 13. The exergy outflow is mostly contingent upon temperature, while the exergy inflow correlates with solar radiation, which remains almost identical in both configurations; thus, exergy efficiency is determined by outlet temperature. It is noticed that exergy efficiency was between 1.41 and 16.36%, and the average exergy efficiency was 11.27%. Hassan et al.35 stated that the overall system has an exergy efficiency of 23.12%, Mugi and Chandramohan80 reported that the average exergy efficiency for ADSD in forced convection was 2.03%, while in natural convection, this was 2.44%. Selimefendigil et al.44, stated that the average exergy efficiency ranged between 2.4% and 3.45%. and Chowdhury et al.47, reported that the mean value of the exergetic efficiency of was 41.42%.

Exergy sustainable indicators of the ADSD

The exergy sustainability indicators, such as, IP, WER and SI, were calculated for ADSD to assess exergy losses and exergy efficiency in relation to the total exergy input. These metrics are vital for evaluating the system’s performance and optimizing the design of the drying chamber. By analyzing these indicators, engineers can identify areas of inefficiency, reduce energy waste, and enhance the sustainability of the drying process, ensuring more effective and eco-friendly operations. The IP in exergy-based sustainable indicators measures the potential to enhance energy efficiency and reduce WER in systems. It quantifies the gap between current and optimal performance, guiding efforts to minimize exergy destruction. By identifying inefficiencies, IP supports sustainable development, resource conservation, and the transition to cleaner, more efficient energy systems. IP is a function of exergy losses (Eq. (25)). The estimated IP was in the range of 2.16 to 11.92 W. It means that a lower amount of exergy losses is noticed in the present setup. The obtained value of IP comes in agreement with Mugi and Chandramohan80 (9.5 × 103 to 12.75 W), and Akpinar83, (0—17 W), It means that a lower amount of exergy losses is noticed in the present setup.

WER and SI of ADSD were calculated using Eqs. (26) and (27) and are shown in Fig. 14. The WER refers to the proportion of energy input that is lost or wasted during the drying process, rather than being utilized effectively. It is calculated as the ratio of waste exergy (unusable energy) to the total exergy input. A lower WER indicates higher efficiency, as less energy is wasted. This metric is crucial for optimizing solar dryer performance, as it helps identify energy losses and inefficiencies in the system. By minimizing WER, designers can improve energy utilization, reduce operational costs, and enhance the sustainability of the drying process, making it more environmentally friendly and economically viable. Since exergy loss is directly proportional to the temperature drop, WER decreases with drying time. WER values decreased by increasing the air temperature, where the lowest values were observed at 12 p.m. The average value of WER was 0.843. This value was slightly higher compared to Mugi and Chandramohan80, (0.41 and 0.445), and Ndukwu et al.84, (0.38 and 0.55).

SI is defined in terms of exergy efficiency and is inversely proportional to exergy losses. It delineates the exergy input per unit exergy loss in the ADSD, hence establishing an inverse relationship with WER. Figure 14 illustrates that when the SI grew, the exergy input also increased while losses diminished. In ADSD, the SI value was elevated, ranging from 1.01 to 1.20. Mugi and Chandramohan80 reported that the average value of SI ranged between 5.1 and 3.69, and45 reported similar values of SI, which varied between 1.26 and 1.71. Also, Sinha et al.36, reported that the SI ranged between 1.12 and 2.57, and Hassan et al.35, mentioned that the SI of the system is found to be 1.30.

Environmental analysis of the ADSD

The environmental analysis was conducted for both the ADSD and PV systems (Table 3), focusing on energy consumption and carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions released into the surrounding environment. The study utilized the concept of carbon footprint to evaluate the environmental impact of ADSD, particularly during the dehumidification phase, where CO₂ mitigation plays a significant role. By assessing energy use and emissions, this analysis provides insights into the system’s environmental performance, highlighting its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to sustainable practices. Such evaluations are essential for optimizing energy efficiency and minimizing the ecological footprint of drying technologies. The obtained results showed that the EPBT ranged from 6.89 to 2.71 and 1.77 years, respectively. This means that the layer of henna leaves has a great impact on EPBT, where drying of henna leaves at a layer thickness of 6 cm led to a decrease in EPBT by about 74.3%. According to the current study, the lifetime of the ADSD was assumed to be 30 years. The EPBT of the ADSD ranged between 5.9% of the lifetime when drying henna leaves at a layer thickness of 6 cm. Moreover, average annual CO₂ emissions in lifetime values for ADSD were 133.46 kg/year. On the other hand, net CO₂ reductions over the lifetime of ADSD were found to be 13.45 tons, 40.42 tons, and 63.90 tons at henna leaf layers of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively. Table 4 shows a comparison between the EPBT of the ADSD with previous studies. The comparative analysis of SDs reveals significant variations in EPBT, ranging from 1.17 to 5.14 years, with the hybrid PVT-based ADSD for henna leaves (6 cm thickness) achieving the lowest EPBT (1.17 years) due to its efficient PVT synergy and optimized loading. While phase change materials (PCMs) and solar trackers improve performance (EPBT: 2.4–2.98 years), forced convection systems show higher EPBT (up to 5.14 years). Notably, tomato dryers generally exhibit longer EPBTs (2.4–5.14 years) compared to fish (1.59 years) or henna, underscoring the impact of product-specific design and operational parameters on sustainability.

Conclusion

In the current study, an investigation of energy, exergy, and techno-environmental performance analysis and sustainability indicators of a PVT-based ADSD while drying henna leaves were conducted at three-layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, an air speed of 0.05 m/s, and a mass flow rate ranging between 0.057 and 0.061 kg/s. Based on the obtained data, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

The henna samples dried using the ADSD reached the equilibrium moisture content faster than the other samples dried in OSD, where the drying time was 14, 15, and 16 h for the ADSD and 15, 17, and 19 h for the samples dried in OSD, for layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively.

-

The hue angle of dried henna leaves using the ADSD at a 6 cm layer thickness is very close to the fresh sample. This means that the use of ADSD had no noticeable effect on the color characteristics of dried henna leaves.

-

The lower color change (ΔE) value was observed with samples dried on OSD at a layer thickness of 2 cm, followed by the samples dried on ADSD at a layer thickness of 6 cm.

-

The average efficiency of the ADSD were ranged between 9.11 and 41.66%, while the highest drying efficiency was 14.97%, 31.98%, and 34.57% at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively.

-

The estimated SMER was 0.321, 0.777, and 1.145 kg/kW.h, at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm, respectively.

-

The exergy outflow, exergy loss and exergy efficiency of ADSD were in a range of (3.13–260.16 W), (218.64 -1396 W) and (1.42 – 16.36%), respectively.

-

The IP was in the range of 2.16–11.92 W while the SI and WER varied from (1.01 to 1.20) and (0.79 to 0.94), respectively.

-

The EPBT was 6.89, 2.71, and 1.77 years, at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm of henna leaves, respectively.

-

Average annual CO2 emission in lifetime values for ADSD was 133.46 kg/year, while net CO2 mitigation in lifetime values for ADSD was found as 13.45, 40.42, and 63.90 tons, at layer thicknesses of 2, 4, and 6 cm of henna leaves, respectively.

Data availability

All data are provided within the article.

References

Elmessery, W. M. et al. Deep regression analysis for enhanced thermal control in photovoltaic energy systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 30600 (2024).

He, Y., Li, X., Huang, P. & Wang, J. Exploring the road toward environmental sustainability: natural resources, renewable energy consumption, economic growth, and greenhouse gas emissions. Sustainability 14, 1579 (2022).

Kreps, B. H. The rising costs of fossil-fuel extraction: An energy crisis that will not go away. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 79, 695–717 (2020).

El-Mesery, H. S. et al. Optimization of dried garlic physicochemical properties using a self-organizing map and the development of an artificial intelligence prediction model. Sci. Rep. 15, 3105 (2025).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Development and techno-economic analysis of a tracked indirect forced solar dryer integrated photovoltaic system for drying tomatoes. Sustainability 16, 7008 (2024).

Prabhu, N., Saravanan, D. & Kumarasamy, S. Eco-friendly drying techniques: A comparison of solar, biomass, and hybrid dryers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 95086–95105 (2023).

Gupta, A., Das, B., Biswas, A. & Mondol, J. D. Sustainability and 4E analysis of novel solar photovoltaic-thermal solar dryer under forced and natural convection drying. Renew. Energy 188, 1008–1021 (2022).

Hirmer, S. & Guthrie, P. The benefits of energy appliances in the off-grid energy sector based on seven off-grid initiatives in rural Uganda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 79, 924–934 (2017).

Farag Taha, M. et al. Emerging technologies for precision crop management towards agriculture 5.0: A comprehensive overview. Agriculture 15, 582 (2025).

Aravindh, M. A. & Sreekumar, A. Solar drying—a sustainable way of food processing. Energy Sustain. Through Green Energy https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2337-5_2 (2015).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Quality evaluation of dried tomato fruit and optimization of drying conditions using a modified solar dryer integrated with an automatic solar collector tracker. Sci. Rep. 15, 7659 (2025).

Elghazali, M. N. et al. Technological studies on aswan dry dates products after dehydration. Assiut J. Agric. Sci. 51, 32–49 (2020).

Manimaran, R. A comprehensive review of solar assisted technologies in india for clean water and clean energy. Clean Energy https://doi.org/10.1093/ce/zkae093 (2025).

Zhang, H.-N., Liu, Y., Zhang, H.-L., Wan, Q.-Z. & Wang, Y.-Q. Effect of different drying and grinding techniques on the physicochemical properties and biological activities of fungal polysaccharides. Food & Med. Homol. https://doi.org/10.26599/FMH.2025.9420045 (2025).

El-Sebaii, A. A. & Shalaby, S. M. Solar drying of agricultural products: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 37–43 (2012).

Belessiotis, V. & Delyannis, E. Solar drying. Sol. Energy 85, 1665–1691 (2011).

Daliran, A., Taki, M., Marzban, A., Rahnama, M. & Farhadi, R. Kinetic analysis, mathematical modeling and quality evaluation of mint drying in greenhouse solar dryer. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 46, 102252 (2023).

Rizal, T. & Muhammad, Z. Fabrication and testing of hybrid solar-biomass dryer for drying fish. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 12, 489–496 (2018).

Elwakeel, A. E., Gameh, M. A., Eissa, A. S. & Mostafa, M. B. Recent advances in solar drying technology for tomato fruits: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Energy Syst. 6, 37–44 (2024).

Jain, D. & Tewari, P. Performance of indirect through pass natural convective solar crop dryer with phase change thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 80, 244–250 (2015).

VijayaVenkataRaman, S., Iniyan, S. & Goic, R. A review of solar drying technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 2652–2670 (2012).

Kumar, M., Sansaniwal, S. K. & Khatak, P. Progress in solar dryers for drying various commodities. Sustain. Energy Rev. 55, 346–360 (2016).

Yassen, T. A. & Al-Kayiem, H. H. Experimental investigation and evaluation of hybrid solar/thermal dryer combined with supplementary recovery dryer. Sol. Energy 134, 284–293 (2016).

Wang, W., Li, M., Hassanien, R. H. E., Wang, Y. & Yang, L. Thermal performance of indirect forced convection solar dryer and kinetics analysis of mango. Appl. Therm. Eng. 134, 310–321 (2018).

Lingayat, A., Chandramohan, V. & Raju, V. Design, development and performance of indirect type solar dryer for banana drying. Energy Procedia 109, 409–416 (2017).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Development, drying characteristics, and environmental analysis of a PV operated automatic solar dryer for drying date. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1531601 (2025).

Younis, O. S. et al. Drying characteristics, environmental and economic analysis of a solar dryer with evacuated tube solar collector for drying Nile Tilapia slices. Sci. Rep. 15, 9822 (2025).

Ghanem, T. H. M. et al. Thin-layer modeling, drying parameters, and techno-enviro-economic analysis of a solar dried salted tilapia fish fillets. Sci. Rep. 15, 5073 (2025).

Gupta, A., Das, B. & Mondol, J. D. Experimental and theoretical performance analysis of a hybrid photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) solar air dryer for green chillies. Int. J. Ambient Energy 43, 2423–2431 (2022).

Tiwari, S. et al. Environmental and economic sustainability of PVT drying system: A heat transfer approach. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 40, e13535 (2021).

Bayrak, F. et al. Analysis of a novel PVT dryer using a sustainable control approach. Renew. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2025.122728 (2025).

Veeramanipriya, E. & Sundari, A. R. U. Performance evaluation of hybrid photovoltaic thermal (PVT) solar dryer for drying of cassava. Sol. Energy 215, 240–251 (2021).

Tiwari, S., Tiwari, G. N. & Al-Helal, I. M. Performance analysis of photovoltaic–thermal (PVT) mixed mode greenhouse solar dryer. Sol. Energy 133, 421–428 (2016).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Drying kinetics and thermo-environmental analysis of a PV-operated tracking indirect solar dryer for tomato slices. PLoS ONE 19, e0306281 (2024).

Hassan, R., Barua, H. & Das, B. K. Energy, exergy, exergo-environmental, and exergetic sustainability analyses of a gas engine-based CHP system. Energy Sci. Eng. 9, 2232–2251 (2021).

Sinha, A. A., Choudhary, T. & Ansari, M. Z. Estimation of exergy-based sustainability index and performance evaluation of a novel intercooled hybrid gas turbine system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48, 8629–8644 (2023).

Darvishi, H., Zarein, M., Minaei, S. & Khafajeh, H. Exergy and energy analysis, drying kinetics and mathematical modeling of white mulberry drying process. Int. J. Food Eng. 10, 269–280 (2014).

Brahma, B., Shukla, A. K. & Baruah, D. C. Energy, exergy, economic and environmental analysis of phase change material based solar dryer (PCMSD). J. Energy Storage 88, 111490 (2024).

da Silva, G. M., Ferreira, A. G., Coutinho, R. M. & Maia, C. B. Energy and exergy analysis of the drying of corn grains. Renew. Energy 163, 1942–1950 (2021).

Kumar, A., Ranjan, S., Prakash, O. & Shukla, A. Exergy analysis of solar dryers. Green Energy Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3833-4_8 (2017).

Mugi, V. R. & Chandramohan, V. P. Energy and exergy analysis of forced and natural convection indirect solar dryers: Estimation of exergy inflow, outflow, losses, exergy efficiencies and sustainability indicators from drying experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 282, 124421 (2021).

Zeng, Z. et al. Analysis of drying characteristic, effective moisture diffusivity and energy, exergy and environment performance indicators during thin layer drying of tea in a convective-hot air dryer. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1371696 (2024).

Mugi, V. R. & Chandramohan, V. P. Energy, exergy and economic analysis of an indirect type solar dryer using green chilli: A comparative assessment of forced and natural convection. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 24, 100950 (2021).

Selimefendigil, F., Şirin, C., Ghachem, K. & Kolsi, L. Exergy and environmental analysis of an active greenhouse dryer with Al2O3 nano-embedded latent heat thermal storage system: An experimental study. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.119167 (2022).

Ekka, J. P. & Muthukumar, P. Exergy efficiency and sustainability indicators of forced convection mixed mode solar dryer system for drying process. Renew. Energy 234, 121256 (2024).

Şevik, S., Aktaş, M., Dolgun, E. C., Arslan, E. & Tuncer, A. D. Performance analysis of solar and solar-infrared dryer of mint and apple slices using energy-exergy methodology. Sol. Energy 180, 537–549 (2019).

Chowdhury, M. M. I., Bala, B. K. & Haque, M. A. Energy and exergy analysis of the solar drying of jackfruit leather. Biosyst. Eng. 110, 222–229 (2011).

Singh, P. & Gaur, M. K. Environmental and economic analysis of novel hybrid active greenhouse solar dryer with evacuated tube solar collector. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101428 (2021).

Sienkiewicz-Szłapka, E., Janysz, A. & Wróbel, M. H. Quantification of Lawsone and p-Phenylenediamine in natural henna products for hair colouring available in poland. Cont. Dermatitis https://doi.org/10.1111/cod.14739 (2025).

S’hih, Y. et al. Evaluation of hypoglycaemic, hypolipidemic and glucose tolerant effect of Henna leaves on fructose-induced metabolic syndromes in Wistar rats. Pharmacol. Res.-Nat. Prod. 6, 100150 (2025).

Salah, A. A. S. & Mofleh, S. M. Q. The HPLC And FTIR analytical techniques to determination of Para-phenylenediamine in some black hair dyes. J. Sci. Technol. 30, 47–59 (2025).

Humaish, H. Study comparison analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory activity of aqueous and alcoholic leaves extract of Lawsonia inermis L. (Henna) with ketoprofen in male albino rats. Kufa J. Vet. Med. Sci. 8, 88–100 (2017).

Alkhalaf, M. I. et al. Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of avocado (Persea americana) fruit and seed extract. J.King Saud Univ.-Sci. 31, 1358–1362 (2019).

Bennamoun, L. et al. Exploring forced convective solar drying of henna (Lawsonia inermis) and its effect on the biological activities: Comparison with open sun dried product. Dry. Technol. 42(1540), 1551 (2024).

Bennamoun, L. et al. Exploring Solar Drying of Henna (Lawsonia inermis) and Its Effect on the Bioactivities. (2024).

Bennaceur, S. et al. Effect of ultrasound on henna leaves drying and extraction of lawsone: Experimental and modeling study. Energies (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/en14051329 (2021).

Babu, A. K., Kumaresan, G., Raj, V. A. A. & Velraj, R. Review of leaf drying: Mechanism and influencing parameters, drying methods, nutrient preservation, and mathematical models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 90, 536–556 (2018).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Design and implementation of a PV-integrated solar dryer based on internet of things and date fruit quality monitoring and control. Int. J. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7425045 (2023).

AOAC. Official Method of Analysis. (Association of Officiating Analytical Chemists, Washington, 2005).

Eke, A. B. & Simonyan, K. J. Development of small scale direct mode passive solar dryers for effective drying of tomato. J. Appl. Agric. Res. 6, 111–119 (2014).

Qian, C., Decker, E. A., Xiao, H. & McClements, D. J. Physical and chemical stability of β-carotene-enriched nanoemulsions: Influence of pH, ionic strength, temperature, and emulsifier type. Food Chem. 132, 1221–1229 (2012).

Ganje, M., Jafari, S. M., Farzaneh, V. & Malekjani, N. Kinetics modelling of color deterioration during thermal processing of tomato paste with the use of response surface methodology. Heat Mass Transf. 54, 3663–3671 (2018).

Mendoza, F., Dejmek, P. & Aguilera, J. M. Calibrated color measurements of agricultural foods using image analysis. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 41, 285–295 (2006).

Seerangurayar, T., Manickavasagan, A., Al-Ismaili, A. M. & Al-Mulla, Y. A. Effect of carrier agents on physicochemical properties of foam-mat freeze-dried date powder. Dry. Technol. 36, 1292–1303 (2018).

Dini, M. et al. Color shade heritability of peach flesh. J. Agric. Sci 11, 10–5539 (2019).

Nkhata, S. G. Total color change (ΔE∗) is a poor estimator of total carotenoids lost during post-harvest storage of biofortified maize grains. Heliyon 6, e05173 (2020).

Cengel, Y. A. & Boles, M. A. Thermodynamics: An engineering approach. Sea 1000, 287–293 (2002).

Gitan, A. A. & Al-Kayiem, H. H. Assessment of hybrid solar-thermal multi-chamber dryer integrated with desiccant dehumidifier for uniform drying. Sol. Energy 262, 111880 (2023).

Part, A. Energy metrics assessment of a photovoltaic thermal air collector (PVTAC): a comparison between flat and wavy collector.

Jha, P., Das, B. & Gupta, R. Energy matrices evaluation of a conventional and modified partially covered photovoltaic thermal collector. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 54, 102610 (2022).

Jha, P., Das, B., Gupta, R., Mondol, J. D. & Ehyaei, M. A. Review of recent research on photovoltaic thermal solar collectors. Sol. Energy 257, 164–195 (2023).

Hao, W. et al. Research on the performance and life cycle assessment of photovoltaic/thermal hybrid solar dryer: Comparative analysis with direct and mixed-mode. Appl. Therm. Eng. 272, 126425 (2025).

Yazici, M. & Kose, R. Comparative and comprehensive experimental analysis: Performance variation of a novel hybrid dryer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 240, 122226 (2024).

Panwar, N. L. Experimental investigation on energy and exergy analysis of coriander (Coriadrum sativum L.) leaves drying in natural convection solar dryer. Appl. Solar Energy 50, 133–137 (2014).

Lingayat, A. B., Chandramohan, V. P., Raju, V. R. K. & Meda, V. A review on indirect type solar dryers for agricultural crops–Dryer setup, its performance, energy storage and important highlights. Appl. Energy 258, 114005 (2020).

Hadibi, T., Boubekri, A., Mennouche, D., Benhamza, A. & Abdenouri, N. 3E analysis and mathematical modelling of garlic drying process in a hybrid solar-electric dryer. Renew. Energy 170, 1052–1069 (2021).

Yazici, M., Kose, R. & Acer, S. D. Investigation of the Comparative okra drying performance of a geothermal and solar hybrid forced convection indirect type cabinet dryer. Renew. Energy 239, 122031 (2025).

Kesavan, S., Arjunan, T. V. & Vijayan, S. Thermodynamic analysis of a triple-pass solar dryer for drying potato slices. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 136, 159–171 (2019).

Lingayat, A., Chandramohan, V. P. & Raju, V. R. K. Energy and exergy analysis on drying of banana using indirect type natural convection solar dryer. Heat Transf. Eng. 41, 551–561 (2020).

Mugi, V. R. & Chandramohan, V. P. Shrinkage, effective diffusion coefficient, surface transfer coefficients and their factors during solar drying of food products – A review. Sol. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2021.07.042 (2021).

Bait, O. Exergy, environ–economic and economic analyses of a tubular solar water heater assisted solar still. J. Clean. Prod. 212, 630–646 (2019).

Abhay, L., Chandramohan, V. P. & Raju, V. R. K. Numerical analysis on solar air collector provided with artificial square shaped roughness for indirect type solar dryer. J. Clean. Prod. 190, 353–367 (2018).

Akpinar, E. K. Drying of mint leaves in a solar dryer and under open sun: modelling, performance analyses. Energy Convers. Manag. 51, 2407–2418 (2010).

Ndukwu, M. C., Bennamoun, L., Abam, F. I., Eke, A. B. & Ukoha, D. Energy and exergy analysis of a solar dryer integrated with sodium sulfate decahydrate and sodium chloride as thermal storage medium. Renew. Energy 113, 1182–1192 (2017).

Vijayan, S., Arjunan, T. V. & Kumar, A. Exergo-environmental analysis of an indirect forced convection solar dryer for drying bitter gourd slices. Renew. Energy 146, 2210–2223 (2020).

Prakash, O. & Kumar, A. Environomical analysis and mathematical modelling for tomato flakes drying in a modified greenhouse dryer under active mode. Int. J. Food Eng. 10, 669–681 (2014).

Prakash, O. & Kumar, A. Solar greenhouse drying: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 29, 905–910 (2014).

Baird, G., Alcorn, A. & Haslam, P. The energy embodied in building materials-updated New Zealand coefficients and their significance. Trans. Inst. Prof. Eng. New Zealand: Civ. Eng. Sec. 24, 46–54 (1997).

Jain, A., Sharma, M., Kumar, A., Sharma, A. & Palamanit, A. Computational fluid dynamics simulation and energy analysis of domestic direct-type multi-shelf solar dryer. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 136, 173–184 (2019).

Kumar, M., Sahdev, R. K., Tiwari, S., Manchanda, H. & Kumar, A. Enviro-economical feasibility of groundnut drying under greenhouse and indoor forced convection hot air dryers. J. Stored Prod. Res. 93, 101848 (2021).

Ayyappan, S. Performance and CO2 mitigation analysis of a solar greenhouse dryer for coconut drying. Energy Environ. 29, 1482–1494 (2018).

Barnwal, P. & Tiwari, G. N. Life cycle energy metrics and CO2 credit analysis of a hybrid photovoltaic/thermal greenhouse dryer. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 3, 203–220 (2008).

Yahya, M., Fahmi, H., Hasibuan, R. & Fudholi, A. Development of hybrid solar-assisted heat pump dryer for drying paddy. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 45, 102936 (2023).

Ndukwu, M. C., Onyenwigwe, D., Abam, F. I., Eke, A. B. & Dirioha, C. Development of a low-cost wind-powered active solar dryer integrated with glycerol as thermal storage. Renew. Energy 154, 553–568 (2020).

Rabha, D. K., Muthukumar, P. & Somayaji, C. Energy and exergy analyses of the solar drying processes of ghost chilli pepper and ginger. Renew. Energy 105, 764–773 (2017).

Andharia, J. K., Markam, B., Patel, J. & Maiti, S. Study of a mixed-mode solar dryer integrated with photovoltaic powered dehumidifier. Sol. Energy 273, 112505 (2024).

Zeeshan, M. et al. Novel design and performance evaluation of an indirectly forced convection desiccant integrated solar dryer for drying tomatoes in Pakistan. Heliyon 10, e29284 (2024).

Sharma, M., Atheaya, D. & Kumar, A. Performance evaluation of indirect type domestic hybrid solar dryer for tomato drying: Thermal, embodied, economical and quality analysis. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 42, 101882 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for funding this work.

Funding

The work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Open access funding provided by Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Hungary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.E., methodology, A.E.E., software, A.E.E., M.M.A., formal analysis, A.E.E., investigation, A.E.E., F.S.M., A.E., M.M.A., and A.A.T., resources, A.E.E., A.A.T.O., F.S.M., M.H.E., M.M.A., A.I.A.M., and A.A.T., data curation, A.E.E., A.A.T.O., F.S.M., M.H.E., M.M.A., A.I.A.M., and A.A.T., writing-original draft, A.E.E., writing—review and editing, A.E.E., A.A.T.O., M.F.T., and A.A.T., visualization, A.E.E., A.A.T.O., W.A.O., A.F.A., M.F.T., and O.S., supervision, A.E.E., project administration, A.E.E., funding, W.A.O., A.F.A., O.S., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Recommendations

The study demonstrates that the ADSD significantly reduces drying time compared to OSD for henna leaves, particularly at 6 cm thickness, which also improves drying efficiency and sustainability. ADSD exhibits lower energy payback time (1.77 years) and higher CO₂ mitigation (63.9 tons) at 6 cm. Despite some color retention advantages in OSD, ADSD proves more energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable, making it a viable solution for agricultural drying.

Future works

The current findings are encouraging, but future research should explore temperature and airflow optimization to enhance drying efficiency and product quality. CFD analysis is essential to visualize heat and air distribution patterns, ensuring uniform drying and identifying design improvements. Integrating real-time monitoring with CFD could further refine the system for commercial scalability.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elwakeel, A.E., Oraiath, A.A.T., Omar, W.AM. et al. Investigation of energy, exergy and techno-environmental analysis of a hybrid PVT-based active direct solar dryer while drying henna leaves. Sci Rep 15, 42834 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02323-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02323-1