Abstract

This study proposes a low-cost, IoT-based multi-sensor system for monitoring volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and predicting activated carbon filter replacement in small-scale industrial settings. Sensor modules composed of low-cost VOC sensors were installed at the exhaust of adsorption towers to enable real-time monitoring. To improve measurement accuracy, a Reinforced Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (RANFIS) was developed for VOC concentration prediction, incorporating dynamic outlier detection and correction. Based on RANFIS outputs, a Decision Tree (DT) model estimates the breakthrough point of activated carbon filters to support timely replacement. The system was deployed in an actual automotive painting facility using eight sensor modules with three sensor types. RANFIS outperformed Deep Neural Network (DNN) and conventional ANFIS models, improving RMSE by up to 82.4%. The DT model also achieved over 80% accuracy in predicting filter replacement under different efficiency thresholds. This integrated approach enables real-time, autonomous filter maintenance using economical sensor hardware, providing a scalable solution for VOC management. The proposed system supports more efficient and sustainable operation of emission control systems in small industrial sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) are emitted by many industries, and the emitted VOCs react with NOx and become a major problem for ozone formation and carcinogenic smog1. VOCs also include toluene2, benzene3, and xylene4, which are damaging and carcinogenic to humans. VOCs emissions are increasing due to economic development, population growth, and industrialization, and statistically, VOCs emissions from human sources exceed 1.42 X108 tons of carbon annually5. Various sectors such as pharmaceuticals, packaging, and paint manufacturing are the main sources of VOCs6. In particular, VOCs are emitted from many plants that use organic solvents7, and automobile painting facilities are one of the largest emitters7,8. Currently, VOCs emission reduction facilities are not always managed for small-scale urban workplaces with pollutant generation of 10 tons or less due to technical and cost difficulties in applying and maintaining prevention facilities.

These plants have installed VOCs emission reduction facilities to control VOCs emissions, but most of the management facilities are aging and intermittently managed by the managers. In the automobile painting facility, which is one of the small-scale workplaces here, the main reduction facility installed is a fixed bed adsorption tower9. In fixed bed adsorption towers, activated carbon, which is easy to adsorb VOCs from hydrocarbons, is used as a filter10. However, fixed bed adsorption towers, which are often used as VOCs prevention facilities, are difficult to install due to the limited installation area, and even if they are installed, the management of activated carbon filters used as adsorbents is burdensome for workers and costly for businesses, resulting in poor management10,11,12.

Currently, small-scale operations typically use Flame Ionization Detector (FID) meters to verify the proper operation of the prevention system by self-measuring the activated carbon at the end of the filter13. However, these are expensive and not suitable for full-time monitoring of activated carbon status14. In addition, the replacement cycle of activated carbon is calculated without considering the actual amount and concentration of intermittent VOCs emitted, and is managed according to an arbitrarily set period of time, resulting in poor management of the replacement cycle10. Therefore, to solve this problem, a full-time self-measurement system utilizing a low-cost gas sensor system can be considered as an alternative.

Network monitoring systems using low-cost sensors have been proposed for air quality monitoring15,16, and the sensor types mainly used as low-cost sensors are Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) and Photo Ionization Detector (PID) sensors17,18. However, low-cost gas sensors have limitations in measurement accuracy due to differences in initial values19, external temperature and humidity20, and light source instability21. In addition, due to the nature of gaseous materials, it is difficult to measure at a precise location, so measurements are made only at a specific location13. However, a single measurement obtained with a low-cost sensor is not reliable.

To address these limitations, researchers have been working on calibrating sensors or predicting their accuracy using low-cost sensor arrays and Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms. Previous studies have used Long Short-Term Memory Neural Networks (LSTM NNs) to predict the actual values of MOS sensors in transient states22, or MOS sensor arrays and Back Propagation Neural Networks (BPNNs) to estimate VOCs concentrations23. It was also used in the challenge of disease diagnosis by distinguishing between breath samples from patients with diseases and healthy individuals through gas sensors and AI algorithms24. Studies have compared Multi Linear Regression (MLR) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) using data collected outside of laboratory environments, finding that ANNs outperformed MLRs due to their ability to model nonlinear data effectively25,26. Additionally, Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) has been widely used for air quality prediction27,28, and several studies have compared its performance with models such as MLR and Support Vector Machine (SVM)29,30.

Changes in external environments, such as climate change, can introduce noise into the data. To learn and adapt to these variations, some studies have collected long-term data for training purposes26, while others have integrated environmental factors such as temperature and humidity alongside key measurement parameters into the learning process31. However, ANNs rely on training data32, which can lead to poor performance in noisy data33,34. To address this issue, preprocessing to detect and remove outliers from the training data is important, and statistical analysis techniques such as standard deviation, median absolute deviation, and interquartile range (IQR) are commonly used to determine outliers35.

To overcome these critical challenges, this study proposes a novel, intelligent VOC emission monitoring and management system based on an Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled multi-sensor network combined with a Reinforced Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (RANFIS). The developed low-cost multi-sensor modules, strategically installed at adsorption tower outlets, significantly improve spatial measurement resolution. The proposed RANFIS model integrates systematic outlier detection and self-correction mechanisms into the conventional ANFIS framework, effectively enhancing sensor accuracy under dynamic environmental conditions. Furthermore, a Decision Tree (DT) model leverages the RANFIS predictions to determine optimal replacement cycles for activated carbon filters, providing practical and actionable insights for facility managers.

This integrated IoT-based monitoring system offers substantial improvements over traditional methods, featuring cost-effectiveness, scalability, and real-time operational capability. Consequently, the proposed framework significantly advances the management efficiency of VOC emission controls and filter maintenance in urban small-scale industrial facilities.

VOCs emission reduction system based on IoT multi-sensor network

VOCs emission reduction facility at an automotive paint shop

Automotive paint shops consist of paint booths and VOCs prevention facilities, and the thinners used in the paint booths primarily contain toluene, butyl acetate, xylene, and ethylbenzene. Activated carbon is the best adsorbent for removing VOCs from these hydrocarbons. Due to its high specific surface area and high affinity for VOCs, activated carbon can easily adsorb VOCs from the atmosphere at room temperature. Once activated carbon is saturated with adsorbent, it can no longer adsorb and will release pollutants into the air, so the adsorbent must be replaced. Replacing the adsorbent too soon can result in the activated carbon not being saturated enough, which can be costly, while replacing it too late can result in the release of pollutants into the air. Therefore, it is very important to determine the appropriate replacement cycle. However, the calculated replacement cycle is not accurate because it is difficult to know the exact value of adsorption efficiency, adsorption amount per unit weight, etc. in the actual field, and there are more intermittent emissions than continuous emissions of pollutant gases10. In addition, in the case of emissions of multiple components of VOCs, such as automobile paint booths, the breakthrough time is shorter than the replacement cycle calculated by the above variables due to the phenomenon of competitive adsorption36. In most cases, the replacement cycle of activated carbon is determined based on experience, or a certain period is arbitrarily set as the replacement period, and the management of the activated carbon replacement cycle is not managed properly.

The paint booth prevention facility used in this study is shown in Fig. 1. Contaminated gases pass through a pre-filter and activated carbon before being discharged to the atmosphere. The activated carbon bed is designed to fill as much space as possible with minimal differential pressure. The activated carbon becomes increasingly saturated as the pollutant gas enters, and once it is fully saturated, it can no longer adsorb the pollutant gas and discharges it at the same concentration as the entering gas. In general, the point at which the outlet concentration becomes 10% of the inlet concentration after the pollutant gas passes through the activated carbon layer is called the breakthrough point, and after reaching the breakthrough point, the outlet concentration increases rapidly and becomes equal to the inlet concentration. It is best to set the replacement cycle of activated carbon at the point where the breakthrough point is reached. However, since most paint shops do not continuously measure the concentration of pollutant gases, it is difficult to determine the time when the breakthrough point is reached.

IoT multi-sensor network-based monitoring system

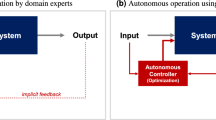

VOCs prevention facilities are mandatory for air pollutant emission facilities such as automobile painting facilities. However, the monitoring system to operate and manage them is not properly established, and small-scale businesses often fail to operate them due to the burden of administrative work12. The existing emission reduction system requires intermittent measurement reporting rather than full-time management. To solve this problem, a system that monitors and manages the emission reduction system of a workplace in real time is needed. Therefore, this study proposes a system to monitor and manage the emission reduction system in real time as shown in Figs. 2 and 3, we propose a low-cost, multi-type IoT multi-sensor-based monitoring system. VOCs emissions are measured through sensor modules attached to the exhaust outlet of the workplace prevention facility, and the data is stored in the Database (DB) of the local server in the workplace through CAN (Controller Area Network) communication. In the local server of each workplace, the measurement system is trained based on the RANFIS model proposed and updated in this study to estimate VOCs emissions. Based on the estimated data, the filter replacement cycle of the workplace prevention facility is predicted. The local server is connected to the main server that monitors small workplaces through Ethernet-based network communication, and the data is managed and secured to prevent tampering and loss and transmitted to the main server. The main server can check the VOCs emissions and activated carbon breakthrough rate for filter replacement in real time for each workplace, and the individual data is sent back to the workplace’s monitoring system for the manager to check.

Multi-sensor systems

Figure 4 shows an IoT multi-sensor system installed at the site. Each sensor module is built with a local server and CAN communication. Each module can transmit and receive data through the CAN bus, which makes it easy to reduce and expand the module, and the CAN network configured in the proposed system is a communication method that uses the voltage difference between the two wires, High and Low, which is resistant to electrical noise. The sensor module acts as a client of CAN communication and communicates with the local server PC by setting aside a microcontroller unit (MCU) that acts as a CAN communication host and checks the data in real time to minimize the loss rate, and then saves the data in a real-time manner.

The VOCs sensor is mounted on a designed circuit board, and the sensor data is communicated through the analog to digital converter (ADC) port of the MCU (CORTEX-M3) to process the data. Since the sensor module is installed in the exhaust and performs direct measurement, the measurement part is placed outside the case and the power and communication part are placed inside the sensor module to protect the circuit. The low-cost sensors used for VOCs measurement were MQ135 (Sensor 1)37, MQ138 (Sensor 2)38, and PID-A15 (Sensor 3)39, which were selected to measure multiple species in as wide a range as possible even with measurement errors. MQ135 and MQ138 are MOS type sensors.

The MOS type sensor changes in resistance caused by chemical reactions between VOCs and the surface of the metal oxide semiconductor. While this method is sensitive to temperature and humidity20,40 and has relatively low accuracy, it is characterized by a low cost and reasonable lifespan20. Specifically, the MQ135 sensor is sensitive to gases such as ammonia, carbon dioxide, and benzene37, whereas the MQ138 is specialized for detecting VOCs and alcohols38. However, due to the nature of the sensor, it exhibits high cross-sensitivity, making it challenging to distinguish between specific gases20. The PID-A15 is a PID type sensor that measures the current generated by ionizing VOCs using UV photons39. The PID method, while offering high selectively and accuracy, measures the overall total VOC (TVOC) concentration20. And They have measurement ranges of 0 ~ 1000ppm, 0 ~ 500ppm, and 0 ~ 4000ppm, respectively.

IOT multi-sensor network-based VOCs measurement and analysis in an automotive paint booth facility

IoT multi-sensor system setup in a painting facility

Since the measurement of VOCs in conventional prevention facilities requires intermittent measurements with a single high-precision measuring instrument with FID method, it is measured at a position where the air flow inside the exhaust vent is stable as much as possible, as shown in Fig. 4a. Therefore, in order to reduce the measurement error and improve the accuracy, this study installed 8 sensor modules around the sampling point of the prevention facility for reducing VOCs emissions in painting facilities, as shown in Fig. 4b, and measured the data. The sensor modules from the bottom are Pos 1, 2, 3, and 4, and the sensor modules installed directly above are Pos 5, 6, 7, and 8. The installed sensor modules are connected to the distribution board through communication lines and power lines to the location where the local server PC is installed. The Host MCU was used to transmit data through CAN communication, and the collected sensor data was stored in the DB through the local server PC.

In the painting booth, a paint thinner (AB380S) was used to generate VOCs inputs to simulate a real-world painting environment. The thinner used has a boiling point of 150℃ and a density of 0.884 g/cm3. The thinner was evaporated using a large heat plate in the center of the paint booth while running the supply and exhaust motors. The evaporation rate of the thinner increases with the heat plate temperature and as the remaining amount in the through decreases. So the evaporation rate of the thinner does not remain constant. The amount of activated carbon in the prevention facility was 400 kg, and eight 17 L pails (120 kg, 135.74 L) of thinner were used to pass through it. VOCs were measured in the exhaust using the FID method phx4241 as a reference instrument. The experiment was conducted twice, with data counts of 43,793 and 25,836, respectively. The field test experiments were conducted in a temperature range of 24℃~ 34℃ and relative humidity conditions of 27–72%. The experiments were run until the activated carbon set up for the dose was exhausted, and the generated data sets were used for model training and evaluation of the trained model, respectively.

Analyzing data

A normalized comparison of the data from the VOCs sensors attached to the exhaust vents shows that the measurements are different depending on the position of the sensor. In Fig. 5a, b, and Fig. 6, when observing Sensor 3 at different heights but in the same direction, Pos 1 and 5, as well as Pos 2 and 6, show large errors compared to the reference sensor and have relatively low correlation coefficients. While as seen in Fig. 5c, the Sensor 3 data in the opposite direction closely follows the reference sensor, with a correlation coefficient of 0.9 or higher. These differences stem from variations in airflow caused by the vent’s installation position and the particle size within the vent, complicating accurate measurements at specific locations. Consequently, the measurement ports are installed in areas with stable airflow, avoiding curved sections. Additionally, sensor modules are evenly distributed around the measurement ports to ensure balanced data collection.

As shown in Fig. 7, even with a high correlation coefficient, each sensor has a different initial value, and the raw data from the sensors is based on a different criteria. This requires precise calibration for each sensor, but it is time and economically inefficient to precisely calibrate each sensor individually18. Therefore, sensor module calibration is necessary before training to use low-cost VOCs sensors in the field. In addition, since Sensor 1 and Sensor 2 are MOS type sensors, they are sensitive to temperature and humidity, and since the measurement site is exposed to the outside, the sensor characteristics20 may exacerbate measurement errors. These errors can also be seen by correlation with the reference sensor in Fig. 6, which confirms the need for an outlier correction method to compensate for data errors.

ANFIS-based VOCs measurement

Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) is a system for processing ambiguous information or uncertain data and supporting decision making, and it works based on fuzzy logic. It is a theory that attempts to express ambiguous human language in computer language, and it can easily solve mathematical complexity and respond to nonlinear systems and multiple input/output systems. The Adapted Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) proposed by Jang42 is a model that combines artificial neural networks and FIS, and is advantageous for the measurement of VOCs in this study because it can model the nonlinear complexity of real data and naturally process the uncertainty and noise of measurement data with fuzzy logic29 to enable stable calibration. The general ANFIS model for a single-channel input consists of five layers.

Layer 1: membership value computation

Layer1 computes membership values using a generalized bell-shaped membership function:

Here, \(\:x\in\:\mathbb{R}\) is a scalar crisp input, \(\:{\mu\:}_{{A}_{i}}\) is the membership function of i-th fuzzy set within the linguistic label. \(\:{a}_{i},\:\:{b}_{i}\) \(\:{c}_{i}\:\in\:\mathbb{R}\) are premise parameters that determine the shape of the membership function.

Layer 2: rule firing strength calculation

This layer calculates the weights of each rule by multiplying the membership values of the corresponding membership functions:

where \(\:x,\:y\:\in\:\:\mathbb{R}\) are scalar crisp inputs, and \(\:{\mu\:}_{{A}_{\left(i\right)}},{\:\mu\:}_{{B}_{\left(i\right)}}\) represent the membership functions for these inputs.

Layer 3: normalization of rule strengths

Normalized weights are computed as:

Layer 4: rule output calculation

Each rule’s influence on the output is calculated by applying a linear function of the input variables, weighted by the normalized firing strength:

where \(\:{p}_{i}\), \(\:{q}_{i},\:\:{r}_{i}\:\in\:\:\mathbb{R}\) are scalar consequent parameters of the i-th rule.

Layer 5: aggregation of rule contributions

The overall output is obtained by aggregating the contribution of all rules:

Therefore, in this study, ANFIS was trained to calibrate the sensors of a multi-sensor system and improve the measurement accuracy. In the preprocessing stage, all sensor datasets were filtered using a fifth-order Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter with a cutoff frequency of 1. The filtering process is described by:

where, \(\:x\left[n\right]\), \(\:y\left[n\right]\in\:\mathbb{R}\) are the discrete-time input and output signal at time step \(\:n\), respectively. Here, \(\:{b}_{k}\), \(\:{a}_{k}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) represent feedforward and feedback filter coefficients, in the IIR filtering process, respectively, and \(\:M,\:Q\in\:\mathbb{N}\) denote the filter order. Finally, min-max scaling normalization was performed through Eq. 7 to learn with sensor modules at different locations.

where \(\:x,\:x\mathbf{{\prime\:}}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) is the original and normalized scalar input values, respectively. \(\:X\) is the complete set of observations for the scalar input x. During training, the generalized bell-shaped membership function is used with an epoch count of 100 to adapt the model parameters using gradient descent-based optimization.

We trained ANFIS on the dataset for three preprocessing scenarios, as shown in Fig. 8. The first was trained using sensors for all locations. Second, the dataset was trained by excluding the sensor with the lowest correlation with the reference sensor. As shown in Fig. 6, we excluded Pos 4 for Sensor 1, Pos 6 for Sensor 2, and Pos 5 for Sensor 3. Finally, to remove outliers from datasets with large measurement errors, such as the data from Sensors 1 and 2, we used the interquartile range (IQR), a common method, to determine the outliers and correct for them before training. Figure 9 shows the process of determining and correcting for outliers in the data from a portion of Sensor 1’s dataset across the eight multi-sensor modules. Based on the mean and standard deviation of the eight data at a particular point in time, data outside a certain distance were judged as outliers and corrected. The correction was trained by replacing it with the nearest normal value and replacing it with the average of the normal values.

The learning assessment was evaluated by Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) using Eq. 8.

where, \(\:n\) is the number of data, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual data, and \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted data corresponding to \(\:{y}_{i}\). Figure 10; Table 1 show the results of training the ANFIS model on the three preprocessed datasets. In Fig. 10(a), we can see that Sensor 3 performs the best when learning the sensor data from all locations, but Sensors 1, 2, and 3 all have large RMSE values. The result of training the dataset excluding the sensors at the locations with the lowest correlation with the reference sensor is shown in Fig. 10(b) and it can be seen that the RMSE is lower than when training the sensors at all locations. This means that there are sensors in the sensor data that contain a lot of measurement errors and outliers when measured in the field. Data from sensors with large measurement errors can be caused by measurement location selection, sensor aging, sensor failure, etc. and in situations where continuous monitoring is required in the field, sensors may be replaced frequently, so a method to evaluate the entire sensor dataset is needed.

Figure 10(c) shows the result of calibrating the nearest normal data by determining outliers through IQR and replacing them with the nearest normal data, and the performance is improved over the result of learning the whole sensor data as shown in Table 1. Figure 10(d) shows the result of compensating for the outliers by replacing them with the average, and it can be seen that the performance is improved compared to learning the entire sensor data except for Sensor 3. This shows that identifying and compensating for outliers is important to improve performance. However, we can see that replacing it with the average does not perform well because it is less affected by the suddenly changing data of the reference sensor, and we can see that the method that compensates with data from nearby normal values performs better.

Nevertheless, even after correcting for outliers, the error is still large and a new correction method is needed. In addition, Table 1 shows that the performance is lower when training with 10,000 data. This means that as the number of data increases, more conditions are learned and the performance improves. In the results of judging and correcting outliers in Sensors 1 and 2, the results of training with 10,000 data showed better performance, indicating that even with a large amount of data, the percentage of outliers in the data greatly affects the learning.

Proposed RANFIS model optimization method and validation

In this section, we propose a RANFIS model to correct the continuity of the entire data by determining and correcting outliers in the sensor dataset and detecting and correcting data with abnormal or rapidly changing rates of change by analyzing the gradient. We also introduce a methodology for optimizing the proposed model. As shown in the architecture and flowchart of Fig. 11, RANFIS improves the conventional ANFIS model by adding two preprocessing layers aimed at robust outlier detection and correction. In particular, Layer 1 and Layer 2 systematically analyze statistical deviations and gradient behaviors, evaluating the dataset by determining the percentage of outliers in Layer 2 to optimize the model parameters.

To determine the outliers among the data obtained in real time from multiple sensors in Layer 1, use Eq. 9 and Eq. 10 to find the mean and standard deviation of the data. Determine a range of normal values using Eq. 11, and judge data outside the range as anomalies. Replace the data determined to be an outlier with the closest normal data using Eq. 12.

Layer 1: statistical outlier removal

This layer identifies and removes statistical outliers from sensor measurements based on threshold derived from statistical metrics. For each sensor, the mean and standard deviation of measurements are calculated as follows:

where\(\:\:N\) is the number of sensors, \(\:{x}_{ij}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) is the input data from i-th sensor at j-th time instance, i is the sensor, and \(\:{m}_{i}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{i}\) are the mean and standard deviation of the sensor measurements at the j-th time instance, respectively. Using a predefined threshold parameter \(\:\tau\:\mathbb{\:}\in\:\mathbb{R}\), the set of outliers for sensor i is identified as follows:

Each measurement \(\:{x}_{ij}\) is corrected based on its classification as an outlier or normal data point. Specifically:

Here, the outlier value is replaced by the nearest non-outlier value from the measurements of the same sensor. In Fig. 12, the sensor data determined to be an outlier in Layer 1 is corrected by replacing it with the closest normal value. Table 2 shows the percentage of sensor data judged to be outliers in the entire dataset.

Table 2. Percentage of outliers for the entire dataset.

Using Eq. 15, Layer 2 analyzes the gradient between the data at one point in time and the data at the previous point in time to determine that gradient data with a different sign than the sum of the overall gradient is a Gradient Analysis based Outlier (GAO). Using Eq. 17, replace the gradient data that is determined to be a GAO with the closest data. In addition, measurement errors due to attached location, aging, failure, etc. are corrected by evaluating the reliability of the sensor dataset with the Quality Score (QS). QS is calculated through the ratio of GAO and accumulated data, and if the threshold R is exceeded, the data is replaced with the sensor with the lowest QS at the point of exceeding the threshold. This ensures that unreliable data sources are automatically excluded in favor of more trustworthy ones, without the need for labeled training data. The system continuously updates the baseline statistics and gradient in real time using only the incoming sensor data, allowing it to dynamically adapt to sensor drift or failure scenarios while maintaining long-term data reliability through autonomous self-correction.

Layer 2: gradient-based outlier detection

This layer detects gradient analysis-based outliers:

The gradient of the data is calculated as:

The gradient-based filtered value is:

A binary GAO flag is assigned as:

The Quality Score (QS) is computed as:

The corrected value for \(\:{x}_{ij}\) is determined as:

where \(\:{\widehat{x}}_{ij}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) represents the data from the sensor dataset with the lowest quality score that means the most reliable sensor. \(\:i\:\in\:\{1,\:2,\:\dots\:,\:{N}_{s}\}\) and \(\:j\:\in\:\{1,\:2,\:\dots\:,\:{N}_{d}\}\) denote the sensor locations (\(\:{N}_{s}\): number of sensors) and the number of data in the dataset (\(\:{N}_{d}\): number of data points), respectively. \(\:\nabla\:x,\:\:\nabla\:\stackrel{\sim}{x}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) represent discrete gradients between consecutive measurements and the gradient data identified as an outlier through gradient analysis, respectively.\(\:{x}_{ij}^{corr}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) is the corrected sensor measurements and \(\:\text{R}\in\:\mathbb{R}\) is the threshold value for acceptable quality score.

As shown in Fig. 13a, the gradient of the sensor data was corrected, and the sensor data was reconstructed based on the corrected gradient to improve continuity, as shown in Fig. 13b. Table 3 shows the QS per sensor for the entire dataset at Layer 2. The QS ratio remains below 30% for all sensors, except for Sensor 1 at Position 8. This indicates that the threshold should be adjusted to below 30% to identify the optimal value for each sensor.

As shown in Fig. 14, when we examine the GAO ratio and QS with accumulated data during training in Layer 2, we observe that QS tends to be high in the early GAO cases. To address this, we compare and tune the baseline value R after 10,000 data accumulations. Based on 28%, Sensor 1 was found to have several sensors that exceeded the threshold after 10,000, and the sensor with the lowest QS was replaced. Sensor 2 can be seen to drop after 26,000 data points due to Pos 8 being replaced. For Sensor 3, we can see that all sensor datasets are above the threshold.

To set the baseline value for each sensor, the RANFIS model was trained by adjusting the QS from 30 to 16%. Figure 15 shows the RMSE of the RANFIS model training results by QS and sensor. Figure 16 presents the training error of the RANFIS model when the QS is at its lowest RMSE. And Fig. 17 shows the RANFIS training results when the RMSE is the lowest among the QS in a graph by sensor. The analysis shows that Sensor 1 performs best when the QS is 22%, Sensor 2 performs best when the QS is 28%, and Sensor 3 performs best when the QS is 18%.

Table 4 presents a performance comparison between the RANFIS model under the optimal QS condition and conventional models including a Deep Neural Network (DNN) and ANFIS. The DNN model architecture consists of an input layer with 8 neurons (corresponding to the number of sensor modules), three hidden layers with 128, 128, and 64 neurons respectively, and a single output neuron for predicting VOC concentration. The swish activation function was applied to all hidden layers. The ANFIS model was configured using the same parameters as the RANFIS model for a fair comparison. Performance was evaluated using RMSE and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), as defined in Eqs. 8 and 18. The results show that while both ANFIS and DNN models exhibited sensor-dependent performance variations, the RANFIS model consistently outperformed both in all cases. This indicates that each sensor dataset contains a different proportion of outliers, and robust identification and correction of these outliers significantly improve prediction accuracy.

where, \(\:n\) is the number of data, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual data, and \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted value corresponding to \(\:{y}_{i}\).

Activated carbon replacement strategy

Predicting the replacement cycle of activated carbon is important for the efficient operation of a prevention facility. However, it is difficult to accurately determine the breakthrough point because the pollutant gas concentration cannot be measured continuously. In addition, the reduction efficiency should be calculated by measuring the concentration at the inlet and outlet of the prevention facility, but the wind speed is high and there is a high risk of sensor contamination when measuring at the inlet. Therefore, this study proposes a model to predict the replacement cycle by measuring the concentration at the outlet of the activated carbon.

The model’s dataset answer values were generated based on the ratio of the inlet and outlet concentrations of the prevention facility, with a 0 or 1 indicating that replacement is required or not, depending on whether the target reduction efficiency is reached. The reduction efficiency is calculated using Eq. 19, the inlet and outlet concentrations of the prevention facility, and the reduction efficiency decreases as the activated carbon becomes saturated. In general, the point where the ratio of inlet to outlet concentration is 10% is called the breakthrough point, and the reduction efficiency is 90%. However, the large amount of activated carbon used in a prevention facility may partially reach the breakthrough point as it adsorbs VOCs, or the activated carbon may not be fully penetrated during plant operating hours, even with continuous measurements. In addition, while the breakthrough curve is characterized by a sharp rise after the breakthrough point, when large amounts of activated carbon are used, the curve may show a gentle upward slope. This limits the ability to set the reduction efficiency to 90%. Therefore, the target reduction efficiency was varied from 80 to 30% to predict the activated carbon replacement cycle.

Figure 18 shows a graph of the ratio of the inlet concentration to the outlet concentration of the prevention facility measured in the field experiment. For example, when the target reduction efficiency is 70%, the point at which 30% is reached is first set as the activated carbon breakthrough point and the point at which replacement is required, and the correct answer value in the dataset is applied accordingly.

where, \(\:\eta\:\) is the abatement efficiency, \(\:{C}_{in}\) is the inlet concentration of the prevention facility, \(\:{C}_{out}\) is the outlet concentration of the prevention facility, and is the outlet concentration of the prevention facility. As input data, we utilized the ANFIS and RANFIS results based on VOCs concentrations measured at the outlet of the prevention facility using multi sensors. Based on this, a DT model was applied to predict the replacement cycle of activated carbon as shown in Fig. 19 to efficiently solve the binary classification problem of classifying cases that require replacement and cases that do not.

As shown in Fig. 20, using the ANFIS model results, the accuracy is more than 80% except for Sensor 2 when the reduction efficiency is 80%, 70%, and 60%, while the accuracy of predicting the activated carbon replacement cycle drops significantly when the reduction efficiency is lower than 50%. As a result of RANFIS training, the accuracy of activated carbon replacement cycle prediction was higher than ANFIS overall, and similarly, the accuracy tended to decrease from 50%, especially Sensor 3 with 80% reduction efficiency had the highest accuracy.

However, it can be seen from Fig. 18 that the lower the target reduction efficiency, the closer the breakthrough point or replacement point is to the beginning of activated carbon use. This means that the activated carbon will last for a shorter period, and a higher target reduction efficiency will result in shorter replacement cycle for the activated carbon filter. Such a shorter replacement cycle can increase the economic cost and workload of operating the prevention facility. Additionally, a false positive, occurs when the system indicates that the activated carbon needs to be replaced even though breakthrough has not happened. This can increase the economic burden of operating the prevention facility. Conversely, a false negative, happens when the activated carbon has reached breakthrough and needs replacement but is not replaced. This can result in the release of pollutants into the atmosphere, leading to not only economic loss but also significant environmental pollution.

Therefore, setting a low target reduction efficiency while maintaining a certain prediction accuracy is effective for efficient operation of the prevention facility. If the reduction efficiency is set at 60–70%, it can be verified that the system can determine the reasonable replacement cycle with a prediction accuracy of more than 80% for the breakthrough point of activated carbon by absorption and the need for replacement.

Discussion

This study developed and validated an IoT-based multi-sensor smart monitoring system for small-scale VOCs emission prevention facilities. The system collects real-time data from multiple sensor modules and predicts the optimal replacement cycle of activated carbon filters, providing a cost-effective alternative to expensive reference-grade detectors. The proposed RANFIS model enables real-time outlier detection, correction, and robust prediction even in dynamic environmental conditions. Deployment in an actual painting facility demonstrated the system’s practical viability and applicability in real-world settings. However, several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged:

Environmental specificity

The model was trained and validated using data collected under specific conditions, including temperature, humidity, and airflow patterns unique to the test facility. These environmental parameters may influence sensor behavior and model performance. Therefore, the current findings may not generalize to facilities with substantially different operating environments without retraining or recalibration.

Sensor drift, aging, and maintenance

Long-term issues such as sensor drift, aging, and degradation of low-cost sensors have not yet been fully addressed. Robust recalibration strategies and sensor health monitoring techniques must be incorporated to ensure stable, long-term operation.

Optimization of multi-sensor deployment

Although multiple sensors were deployed to enhance data reliability, the optimal number of sensors required to achieve a predefined accuracy level has not been systematically determined. Over-deployment may increase costs and complexity, whereas under-deployment may compromise prediction performance. Future work should focus on optimizing the number and spatial arrangement of sensor modules to balance cost efficiency and predictive accuracy.

Sensor selection and calibration

The use of low-cost sensors, while economically advantageous, presents challenges in terms of selectivity, sensitivity, and cross-sensitivity to non-target gases and environmental variations. Further research is needed to systematically evaluate different low-cost sensor types, calibrate their outputs, and develop correction algorithms to mitigate their limitations.

By addressing these limitations, the proposed system can be further enhanced to achieve broader generalizability, long-term stability, and scalability for diverse industrial applications. To overcome these limitations, future research will focus on the following directions: (1) Expanding the dataset across multiple sites and environmental conditions to validate the robustness and adaptability of the RANFIS model; (2) Developing dynamic recalibration methods to address sensor drift and aging without requiring manual intervention; (3) Conducting systematic studies to determine the minimum number of sensors required to achieve a predefined accuracy level; and (4) Refining sensor selection strategies and improving data fusion techniques to enhance prediction performance while minimizing operational costs. By addressing these challenges, we aim to enhance the system’s generalizability, long-term stability, and practical scalability for real-world deployment across diverse industrial environments.

Conclusion

This study proposed an IoT-based multi-sensor smart monitoring system for small-scale VOC emission prevention facilities, along with a predictive framework to estimate the optimal replacement cycle of activated carbon filters. The system was deployed and validated in a real-world automobile painting booth equipped with eight sensor modules composed of three types of low-cost VOC sensors. To improve prediction accuracy and robustness, a Reinforced Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (RANFIS) model was developed and compared with conventional Deep Neural Network (DNN) and ANFIS models. The RANFIS model integrates real-time outlier detection and correction layers into the learning process. A Decision Tree (DT) model was further applied to the VOC concentration predictions from RANFIS to estimate the replacement timing of activated carbon filters.

Based on experimental results, the RANFIS model achieved RMSE values of 14.757, 16.117, and 8.918 for Sensors 1 (MQ135), 2 (MQ138), and 3 (PID-A15), respectively—demonstrating performance improvements of 67.2–82.4% compared to DNN and 73.6%, 82.4%, and 29.7% compared to ANFIS. Additionally, MAPE values were significantly reduced, confirming the effectiveness of the RANFIS model in reducing sensor measurement error. The DT model trained on RANFIS outputs achieved over 80% accuracy in predicting filter replacement cycles under different efficiency thresholds (60%, 70%, and 80%) using only exhaust gas concentration data. These results demonstrate the feasibility of applying a fully autonomous, low-cost, multi-sensor monitoring system for continuous VOC emission management. The proposed system achieves high accuracy and robustness while minimizing operational cost, offering a scalable solution for real-time environmental monitoring and proactive filter maintenance in small-scale urban industrial sites.

Nevertheless, the applicability of the system beyond the tested conditions requires further validation. While the results indicate promising performance within the evaluated context, generalizability, long-term stability, and optimal deployment strategies remain open areas for future research. Addressing these will be essential for scaling the system to diverse industrial environments.

Data availability

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Berenjian, A., Chan, N. & Malmiri, H. J. Volatile organic compounds removal methods: A review (2012).

Filley, C. M., Halliday, W. & Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B. K. The effects of toluene on the central nervous system. J. Neuropathology Experimental Neurol. 63 (1), 1–12 (2004).

Snyder, R., Witz, G. & Goldstein, B. D. The toxicology of benzene. Environ. Health Perspect. 100, 293–306 (1993).

Rajan, S. T. & Malathi, N. Health hazards of Xylene: a literature review. J. Clin. Diagn. Research: JCDR. 8 (2), 271 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions control in iron ore sintering process: recent progress and future development. Chem. Eng. J. 448, 137601 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Emission characteristics and health risk assessment of volatile organic compounds in key industries: A case study in the central plains of China. Atmosphere 16 (1), 74 (2025).

Song, M. Y. & Chun, H. Species and characteristics of volatile organic compounds emitted from an auto-repair painting workshop. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 16586 (2021).

Choi, S. W. Characteristic of BTEX concentration ratio of VOC emission sources and ambient air in Daegu. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 16 (4), 415–423 (2007).

Kim, B. R. VOC emissions from automotive painting and their control: A review. Environ. Eng. Res. 16 (1), 1–9 (2011).

Choi, Y. J., Rhee, Y. W., Chung, G. H., Kim, D. H. & Park, S. J. A study on the environmental effects of improvement of activated carbon adsorption tower for the application of activated carbon Co-Regenerated system in Sihwa/Banwal industrial complex. Clean. Technol. 27 (2), 160–167 (2021).

Kim, B. R., Podsiadlik, D. H., Yeh, D. H., Salmeen, I. T. & Briggs, L. M. Evaluating the conversion of an automotive paint spray-booth scrubber to an activated‐sludge system for removing paint volatile organic compounds from air. Water Environ. Res. 69 (7), 1211–1221 (1997).

Wang, H. et al. A review of whole-process control of industrial volatile organic compounds in China. J. Environ. Sci. 123, 127–139 (2023).

Zheng, J. et al. Industrial sector-based volatile organic compound (VOC) source profiles measured in manufacturing facilities in the Pearl river delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 456, 127–136 (2013).

Xu, W. et al. New Understanding of miniaturized VOCs monitoring device: PID-type sensors performance evaluations in ambient air. Sens. Actuators B. 330, 129285 (2021).

Piedrahita, R. et al. The next generation of low-cost personal air quality sensors for quantitative exposure monitoring. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7 (10), 3325–3336 (2014).

Kumar, P. et al. The rise of low-cost sensing for managing air pollution in cities. Environ. Int. 75, 199–205 (2015).

Aleixandre, M. & Gerboles, M. Review of small commercial sensors for indicative monitoring of ambient gas. Chem. Eng. Trans. 30, 169–174 (2012).

Spinelle, L., Gerboles, M., Kok, G., Persijn, S. & Sauerwald, T. Review of portable and low-cost sensors for the ambient air monitoring of benzene and other volatile organic compounds. Sensors 17 (7), 1520 (2017).

Kim, J. N. & Kim, H. J. A chemoresistive gas sensor readout integrated circuit with sensor offset cancellation technique. IEEE Access (2023).

Khan, S., Le Calvé, S. & Newport, D. A review of optical interferometry techniques for VOC detection. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 302, 111782 (2020).

Rezende, G. C., Calvé, L., Brandner, S., Newport, D. & J. J., & Micro photoionization detectors. Sens. Actuators B. 287, 86–94 (2019).

Gambiroža, J. Č., Mastelić, T., Kovačević, T. & Čagalj, M. Predicting low-cost gas sensor readings from transients using long short-term memory neural networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 7 (9), 8451–8461 (2020).

Chen, Z., Zheng, Y., Chen, K., Li, H. & Jian, J. Concentration estimator of mixed VOC gases using sensor array with neural networks and decision tree learning. IEEE Sens. J. 17 (6), 1884–1892 (2017).

Guo, D., Zhang, D., Li, N., Zhang, L. & Yang, J. A novel breath analysis system based on electronic olfaction. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57 (11), 2753–2763 (2010).

Topalović, D. B. et al. In search of an optimal in-field calibration method of low-cost gas sensors for ambient air pollutants: comparison of linear, multilinear and artificial neural network approaches. Atmos. Environ. 213, 640–658 (2019).

Spinelle, L., Gerboles, M., Villani, M. G., Aleixandre, M. & Bonavitacola, F. Field calibration of a cluster of low-cost available sensors for air quality monitoring. Part A: Ozone and nitrogen dioxide. Sens. Actuators B. 215, 249–257 (2015).

Saini, J., Dutta, M. & Marques, G. A. D. F. I. S. T. Adaptive dynamic fuzzy inference system tree driven by optimized knowledge base for indoor air quality assessment. Sensors 22 (3), 1008 (2022).

Liu, H., Huang, M., Kim, J. T. & Yoo, C. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system based faulty sensor monitoring of indoor air quality in a subway station. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 30, 528–539 (2013).

Alhasa, K. M. et al. Calibration model of a low-cost air quality sensor using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Sensors 18 (12), 4380 (2018).

Humpe, A., Brehm, L. & Günzel, H. Forecasting air pollution in Munich: A comparison of MLR, ANFIS, and SVM. In ICAART (2), 500–506 (2021).

Tian, B. et al. Environment-adaptive calibration system for outdoor low-cost electrochemical gas sensors. IEEE Access. 7, 62592–62605 (2019).

Choi, S. U., Choi, B. & Choi, S. Improving predictions made by ANN model using data quality assessment: an application to local scour around Bridge piers. J. Hydroinformatics. 17 (6), 977–989 (2015).

Beliakov, G., Kelarev, A. & Yearwood, J. Robust artificial neural networks and outlier detection. ArXiv Preprint. arXiv:1110.0169 (2011).

Liano, K. Robust error measure for supervised neural network learning with outliers. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 7 (1), 246–250 (1996).

Yang, J., Rahardja, S. & Fränti, P. Outlier detection: how to threshold outlier scores? In Proceedings of the international conference on artificial intelligence, information processing and cloud computing (pp. 1–6). (2019), December.

Cho, J. H., Lee, S. & Rhee, Y. W. Activated carbon adsorption characteristics of multi-component volatile organic compounds in a fixed bed adsorption bed. Korean Chem. Eng. Res. 54 (2), 239–247 (2016).

Winsen Sensor – MQ135 semiconductor sensor for air quality. Available online: December (2024). https://kr.winsen-sensor.com/product/mq135-semiconductor-sensor-for-air-quality/ (accessed on 27.

Winsen Sensor – MQ138 VOC gas sensor. Available online: December (2024). https://kr.winsen-sensor.com/product/mq138-voc-gas-sensor/ (accessed on 27.

Alphasense – PID sensors. Available online: https://www.alphasense.com/products/view (accessed 430 on 27 December 2024).

Hirobayashi, S., Kimura, H. & Oyabu, T. Dynamic model to estimate the dependence of gas sensor characteristics on temperature and humidity in environment. Sens. Actuators B. 60 (1), 78–82 (1999).

LDAR Tools. Available online: https://ldartools.com/phx42fid/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

Jang, J. S. ANFIS: adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics. 23 (3), 665–685 (1993).

Funding

This work was supported through the “R&D Project for Intelligent Optimum Reduction and Management of Industrial Fine Dust” funded by the Korean Ministry of Environment (MOE) (2480000134) and conducted by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon university in 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and W.Y.; methodology, K.K. and W.Y.; software, K.K.; validation, K.K.; formal analysis, K.K., W.Y. and D.C.; investigation, K.K.; resources, K.K., W.Y. and D.C.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K., W.Y. and D.C.; visualization, K.K.; supervision, W.Y.; project administration, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K., Chun, D. & Yang, W. IoT-based filter management system using reinforced ANFIS for VOCs reduction in urban industrial facilities. Sci Rep 15, 17455 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02435-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02435-8