Abstract

In the field of smart healthcare, video consultation has become a key way to provide medical services for remote patients. In this process, it is essential to ensure the legal identity of both parties to the communication and to protect patient privacy data from unlawful interception and tampering. Therefore, a controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol is proposed by using the entanglement exchange ability and measurement correlation of Bell states. With the assistance of a trusted third party, the protocol first achieves the mutual authentication of the communication parties, so as to prevent malicious users from communicating by pretending to be medical specialists or patients. The trusted party then further assists the communicating parties in generating two implicit shared keys, which they use to encrypt the message and its digest, ensuring that the patient’s sensitive data is not intercepted or tampered with. In addition, the quantum sequences are transmitted only once in the channel, reducing the loss and noise effects caused by multiple transmissions. Security analysis shows that the protocol can effectively resist participant attacks and outside attacks. In addition, performance analysis provides computation in terms of qubit efficiency and experimental simulation results of the protocol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Driven by the rapid development of information technology, smart healthcare1,2,3 has emerged as a crucial element in enhancing medical service levels optimizing resource allocation, and improving patient experiences. In particular, it offers new avenues for patients in remote regions or those deprived of professional medical resources to obtain timely and high-quality medical services. Nevertheless, during the remote implementation of smart healthcare, it is inevitable to encounter a vast amount of sensitive patient privacy data, encompassing personal health information and diagnostic suggestions from medical specialist. Hence, ensuring the confidentiality and integrity protection of such data becomes particularly paramount. The security of traditional encryption systems employed in the past hinged on the computational complexity of certain mathematical problems, such as the factorization of large integers. However, with the advent of quantum computing, Shor’s algorithm4 has demonstrated an astonishing capacity for factoring large integers on quantum computers presenting unprecedented challenges to traditional encryption systems that rely on these mathematical conundrums. The advancement of quantum algorithms not only initiates a new computing era but also poses a latent threat to the security of classical communication systems.

Quantum cryptography, as the crystallization of the intersection and fusion of cryptography and quantum mechanics, uses quantum states as the carrier of transmitted information. Based on the core principles of quantum mechanics, such as the quantum non-cloning principle5 and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle6, quantum cryptography achieves unconditional security in its communication process. At present, there have been various quantum encryption protocols, applied to different conditions, such as quantum key distribution (QKD)7,8,9 quantum key protocol (QKA)10,11,12,13 quantum identity authentication (QIA)14,15 quantum private comparison (QPC)16,17,18 quantum secret sharing (QSS)19,20 and others21,22. By combining QKD or QKA, quantum confidential communication technology adopts the “one-time pad” encryption strategy, ensuring not only the confidentiality of patient privacy data but also utilizing quantum message authentication mechanisms to safeguard the integrity of data, preventing information tampering during transmission. Furthermore, reliable identity authentication plays a crucial role in maintaining communication security. QIA technology verifies the identity of each user, effectively preventing unauthorized users from impersonation, thereby ensuring that only authorized users can engage in secure communication.

QKD, which enables communicating parties to establish a secure session key, has been rapidly developed since Bennett and Brassard proposed the first QKD protocol, the BB84 protocol23, in 1984. According to the dimension of the coding space at the source side, QKD protocols are categorized into discrete-variable-based QKD (DV-QKD)24,25 and continuous-variable-based QKD (CV-QKD)26,27 where the Hilbert space of the encoded quantum state is finite in DV-QKD, while it is infinite and continuous in CV-QKD. However, when actually building a quantum key distribution system, due to issues such as non-ideal light sources and equipment, the system suffers from security vulnerabilities and is susceptible to threats such as photon number separation attacks, blinding attacks, and time-shift attacks, especially detector-side channel attacks which are the most common among all attacks. To solve this problem, Lo et al.28 proposed the measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution (MDI-QKD) scheme in 2012, which is able to effectively defend against detector-side channel attacks and significantly improve the communication distance. Since then, MDI-QKD has attracted extensive attention from researchers and further promoted the development of related research. In 2020, Sun et al.29 proposed a measurement-device-independent QKD scheme based on orbital angular momentum with dual detectors, which encodes the key information through the orbital angular momentum and sends it to the third-party measurement device, and at the same time, adopts the dual-detector theory to enhance the key generation rate and transmission distance. In 2023, Chen30proposed a four-dimensional MDI-QKD scheme based on phase-polarized hybrid coding by combining the principles of phase-polarized coding, quantum state fusion, and segmentation, and this scheme also shows good performance in terms of key generation rate and secure communication distance. In addition, the applications of QKD have been extended to several fields, e.g., in 2021 Yan et al.31 proposed a smart grid control architecture based on QKD to ensure the security of the control and measurement data flow in the smart grid, while in 2024 Singamaneni et al.32 proposed a multi-quantum bit QKD ciphering strategy for cloud security in combination with attribute-based encryption, which shows good potential in protecting cloud data.

Unlike QKD in which one party generates keys independently, QKA protocols require all participants to jointly and fairly negotiate the generation of shared keys, a feature that makes QKA more compatible with the needs of practical communication security. Since the first QKA protocol33 was proposed in 2004, researchers have proposed a variety of different QKA protocols, including two-party QKA34,35, three-party QKA36,37 and multi-party QKA protocols38,39. For example, an efficient multiparty QKA protocol utilizing single-particle states in two non-orthogonal bases was proposed by Tang et al.40 in 2020, and a quadrilateral QKA protocol based on GHZ entangled states was proposed by Ho et al.41 in 2021. Most of these protocols utilize single-particle states or entangled states as quantum resources. However, considering the effect of noise in real channels, researchers have also proposed QKA protocols that are resistant to noise42,43. In order to adapt to different environments, researchers further proposed controlled quantum key agreement (CQKA)44,45 protocols and semi-quantum key agreement (SQKA)46,47 protocols. In practical applications, confirming participant identity is an important step before key negotiation, which helps to prevent security threats such as impersonation attacks and man-in-the-middle attacks. Therefore, the verification of participants’ identities occupies a crucial position in QKA protocols. In 2022, He et al.48 and Xu et al.49 proposed QKA protocols with mutual authentication, which further enhanced the security and reliability of QKA in practical applications. The Mutual authentication quantum key protocol (MAQKA) proposed by he et al.48is based on the Bell state, which can verify the identity of participants by using the measurement correlation properties of the Bell state, and establish the shared key fairly by using the entanglement exchange relationship of the Bell state. Xu et al.49 utilize entanglement and Pauli operation of quantum states to achieve authentication and key agreement.

QIA technology offers an innovative approach to authentication grounded in the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. This technology effectively verifies the identities of each party involved in communication, thereby preventing unauthorized and deceitful individuals from impersonating legitimate users, which enhances the security and practicality of communications. Within the realm of QIA, two primary types of protocols exist: single-photon state-based QIA protocols50,51 and entangled state-based QIA protocols52,53 . In 2017, Hong et al.54 introduced a single-photon state QIA protocol that operates without entanglement resources; subsequently, in 2019, Zhang et al.55 proposed a QIA protocol utilizing Bell state entanglement exchange to facilitate identity verification between communicating parties through a semi-honest third party.

During communication processes, message authentication holds equal significance to identity authentication as it ensures that messages remain untampered by unauthorized third parties during transmission while safeguarding the integrity and accuracy of information content. Quantum message authentication is a technique within quantum computing that enables recipients of quantum messages to ascertain whether such messages have been altered. Currently, some researchers are dedicated to ensuring message integrity during communication via quantum digital signature56,57, and quantum message authentication technologies58,59. In 2021, Kang et al.60 devised a quantum message authentication protocol leveraging unitary operations on single qubits for authenticating and protecting the integrity of original messages. In 2022, Nicolas61 proposed an algorithm designed to detect malicious tampering with quantum messages (integrity attacks), which minimizes false positives while enhancing detection efficiency.

While QIA and QKA protocols have made significant progress in identity authentication and key agreement, practical applications in smart healthcare still face critical challenges:

-

Lack of integrated security mechanisms Most protocols focus on isolated aspects (e.g., identity authentication or key agreement), but fail to achieve simultaneous identity authentication, key agreement, data encryption and message integrity protection within a unified framework.

-

Inefficient quantum resource utilization Multiple transmissions of quantum sequences in conventional protocols increase channel loss and noise sensitivity, degrading reliability in long-distance scenarios.

In this paper, we will pay attention to the specific application of smart medicine in remote areas—video consultation, aiming to provide safer and more efficient medical services for patients there through quantum confidential communication technology, so as to narrow the regional differences in medical resources and promote the comprehensive progress of smart medical care. In order to protect the confidentiality and integrity of patient privacy information in smart medical services, prevent any information leakage or tampering that may lead to misdiagnosis, and ensure the continuity and reliability of medical services, we propose a controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol. Implemented with the assistance of trusted third party, the protocol ensures the security and integrity of patient private data during confidential communications. In addition, the identity mutual authentication mechanism in the protocol ensures that only authenticated participants can communicate, thus effectively preventing impersonation attacks and man-in-the-middle attacks. It is important to note that the trusted party has control over the agreement, which provides additional guarantees for the implementation of the agreement. Through security analysis and efficiency analysis, the protocol can effectively resist various attacks and has advantages in performance. In summary, the protocol proposed in this paper has the following benefits:

-

The mutual authentication of the patient and the medical specialist ensures that they are not impersonated by an attacker during confidential communication.

-

The confidentiality of the communication content and the integrity of the data are ensured during the video consultation between the patient and the medical specialist. Therefore, it not only effectively protects the privacy of patients but also prevents misdiagnosis caused by data leakage or tampering, ensuring the security and accuracy of medical services.

-

The controller, the hospital information center, is completely controllable for the communication between the patient and the medical specialist, not only for the identity authentication of the patients and the medical specialist, but also for the confidential communication between the two parties.

-

The protocol is well protected against participant attacks and outside attacks.

-

The single transmission of the quantum sequence in the channel significantly reduces the loss and noise effects that may occur due to multiple transmissions. This transmission strategy enhances communication efficiency while mitigating the risks of errors that can arise from complex operations.

-

The quantum source required by the protocol is relatively mature, and the controller, the hospital information center, only needs to prepare the Bell states.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In “Controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol for smart healthcare”, we describe our proposed protocol model and controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol. The correctness and controllability of protocols are discussed in “Correctness and controllability analysis”, and the security analysis including participant attacks and outside attacks is given in “Security analysis”. Experimental details and qubit efficiency are explored in “Experimental and qubit efficiency analysis”. Finally, “Conclusion” summarizes this paper.

Controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol for smart healthcare

In this section, we explore the protocol model in depth and provide a comprehensive overview of our proposed protocol.

Protocol model

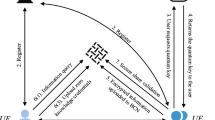

In the realm of smart healthcare, video consultation has emerged as an increasingly prevalent mode of communication, facilitating effective interactions between medical specialists and patients across diverse locations. In this context, safeguarding patient privacy and ensuring data integrity are paramount, as they directly influence patients’ access to accurate diagnoses and treatment options. To address these concerns, we have proposed an innovative controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol model for smart healthcare. This model (illustrated in Fig. 1) comprises three fundamental entities: the hospital information center, the medical specialist, and the patient. For convenience, the hospital information center is called Charlie, and patients and medical specialists are called Alice and Bob. It is worth noting that all three parties require quantum capabilities.

-

Hospital information center As the core trusted entity in the system, it is responsible for preparing sequences of quantum states and transmitting these sequences to medical specialists and patients. In addition, the hospital information center is also responsible for monitoring the quantum channel, conducting eavesdropping detection and ensuring the security of the communication process. It also assists identity authentication and confidential communication for medical specialist and patient by randomly specifying the positions of particles in quantum sequences.

-

Medical specialist Before establishing communication with patient, medical specialist first participates in eavesdropping detection of quantum channels to ensure the security of the channels. After successfully verifying each other’s identities, he communicates with the patient via a confidential communication protocol. In this process, medical specialist receives and decrypts the patient’s medical information to provide an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan for the patient.

-

Patient Patient also participates in the eavesdropping detection of quantum channels to ensure the security of their medical information during transmission. After completing identification with the medical specialist, patient encrypts his medical information and its digest through the confidential communication protocol and securely send them to the medical specialist.

The model aims to provide a higher level of security for medical communications through quantum encryption technology, ensuring the confidentiality and integrity of patient information during transmission, thereby preventing any information leakage or tempering that may lead to misdiagnosis, while protecting patient privacy from being compromised.

Controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol

Our proposed confidential communication protocol (as shown in Fig. 2) is divided into three phase: initialization phase, identity authentication phase and confidential communication phase.

Initialization phase

Suppose two participants, the medical specialist and the patient, Alice and Bob, want to communicate confidentially with the assistance of a trusted controller, Charlie.

In advance, Alice and Bob have secretly shared their identity information \(ID_A\) and \(ID_B\), where \(ID_A=ID_A^1\parallel ID_A^2\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_A^i\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_A^n\), and \(ID_B=ID_B^1\parallel ID_B^2\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_B^i\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_B^n\), \(ID_A^i,ID_B^i\in \{0,1\}\) and \(i=1,2,\ldots ,n\). And the message that Alice intends to transmit is represented as \(M=\{M_1,M_2,\cdots ,M_m\}\), where \(M_{i}\in \{00,01,10,11\}\), \(i=1,2,\ldots ,m\). Moreover, H(x) denotes a hash function capable of processing input data of arbitrary length and producing an output of fixed length n-bit.

Step 1-1:Charlie prepares two quantum sequences \(S_A=\{|\phi ^+\rangle _{12}^1,|\phi ^+\rangle _{12}^2,\cdots ,|\phi ^+\rangle _{12}^N\}\) and \(S_B=\{|\phi ^+\rangle _{34}^1,|\phi ^+\rangle _{34}^2,\cdots ,|\phi ^+\rangle _{34}^N\}\) of length \(N=l+4n+m\), and divides them into four sequences, \(S_1=\{|s_1^1\rangle ,|s_1^2\rangle ,\cdots ,|s_1^N\rangle \}\), \(S_2=\{|s_2^1\rangle ,|s_2^2\rangle ,\cdots ,|s_2^N\rangle \}\), \(S_3=\{|s_3^1\rangle ,|s_3^2\rangle ,\cdots ,|s_3^N\rangle \}\) and \(S_4=\{|s_4^1\rangle ,|s_4^2\rangle ,\cdots ,|s_4^N\rangle \}\), where \(S_1,S_2\) \((S_3,S_4)\) consist of all the 1st and 2nd ( 3rd and 4th ) particles in the sequence \(S_A\) \((S_B)\). Next, Charlie sends sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) to Alice and \((S_2,S_4)\) to Bob. It can be seen that the two Bell states \(|\phi ^+\rangle _{12}\otimes |\phi ^+\rangle _{34}\) satisfy the following equation (1):

Step 1-2: After ensuring Alice and Bob receive the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) from Charlie, respectively. They begin eavesdropping detection of the channel. Charlie randomly specifies l particles at corresponding positions in the sequences \(S_{1}\),\(S_{3}\),\(S_{2}\),\(S_{4}\), and publishes the position information of the l particles to Alice (Bob), which is used for eavesdropping detection. After that, Alice (Bob) performs Bell measurements (BM) on the corresponding l particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) (\((S_2,S_4)\)) and codes the results into a binary sequence \(P_A\) (\(P_B\)) using the coding rule \(G_1\) (as shown in Table 1), where \(P_{A}=P_{A}^{1}\parallel P_{A}^{2}\parallel \cdots \parallel P_{A}^{i}\parallel \cdots \parallel P_{A}^{l}\) (\(P_{B}=P_{B}^{1}\parallel P_{B}^{2}\parallel \cdots \parallel P_{B}^{i}\parallel \cdots \parallel P_{B}^{l}\)), \(P_A^i,P_B^i\in \{00,01,10,11\}\) and \(i=1,2,\ldots ,l\). Then Alice and Bob announce \(P_A\) and \(P_B\) to Charlie, respectively. However, according to equation (1), after Alice and Bob measure the particle pairs at corresponding positions in the quantum sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) respectively, consistent results will be obtained, the measurement results are in the set \(\{|\phi ^+\rangle ,|\phi ^-\rangle ,|\psi ^+\rangle ,|\psi ^-\rangle \}\) with equal probability. And the variable \(P_A^i||P_B^i\) is limited to four distinct cases: 0000, 0101, 1010, and 1111; thus, it becomes feasible to calculate the error rate. If the error rate is below the pre-set threshold, the channel is considered secure, and the protocol proceeds to the next step; otherwise, the protocol is halted and restarted.

Identity authentication phase

After passing the channel eavesdropping detection, Alice and Bob, with the assistance of Charlie, begin the mutual authentication.

Step 2-1: Taking Bob authenticates Alice as an example, and Alice authenticates Bob in the same way. First, Charlie randomly specifies 2n particles in the sequences \(S_1\),\(S_3\),\(S_2\),\(S_4\) and announces their location information to Alice (Bob), which is used for the following authentication. Then Alice uses the measurement base \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\) to measure the 2n particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and records the measurement results. According to equation (1), the measurement results are in the set \(\{|0\rangle |0\rangle ,|0\rangle |1\rangle ,|1\rangle |0\rangle ,|1\rangle |1\rangle \}\) with equal probability. Subsequently, Alice arranges the particles with measurement results \(|0\rangle _1|1\rangle _3\) and \(|1\rangle _1|0\rangle _3\) to obtain the quantum sequence \(r_A\), and codes it into a binary sequence \(R_A\) using the coding rule \(G_1\); the quantum sequence \(t_A\) is obtained by arranging the particles with measurement results \(|0\rangle _1|0\rangle _3\) and \(|1\rangle _1|1\rangle _3\), and converts it into a binary sequence \(T_A\) using the coding rule \(G_2\) (as shown in Table 2). Next, Alice performs the coding rule \(G_3\) (as shown in Table 3) on the binary sequence \(R_A\) according to her identity information \(ID_{A}\) to obtain the sequence \(R_A^*\). And Alice publicly announces the sequence \(R_A^*\).

Step 2-2: After Alice announces the sequence \(R_A^*\), Bob use \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base to measure the 2n particle pairs at corresponding positions in the sequence \((S_2,S_4)\). And Bob performs the same operation on the measurement results as Alice in Step 2-1 to obtain the sequences \(R_B\), \(T_B\). Then Bob performs the coding rule \(G_3\) on the sequence \(R_B\) according to Alice’s identity information \(ID_{A}\) to obtain the sequence \(R_B^*\). In the absence of eavesdropping and noise interference, \(R_A^*=R_B^*\). That is, by comparing \(R_A^*\) and \(R_B^*\), Bob can calculate the error rate. If the error rate is lower than the specified threshold, it indicates that Bob has successfully verified Alice’s identity. Otherwise, authentication fails.

Similarly, Alice utilizes the same way to verify Bob’s identity. Only after both Alice and Bob have successfully authenticated, will the protocol proceed to the next stage. If either party fails to pass the authentication, the protocol is terminated and restarted. Finally, Alice (Bob) retains the binary sequence \(T_A\) (\(T_B\)), which is used to ensure data integrity in subsequent confidential communications.

Confidential communication phase

After Alice and Bob complete their identity authentication, the confidential communication between them occurs.

Step 3-1: Alice and Bob utilize the remaining m particles in the sequences \(S_1\),\(S_3\),\(S_2\),\(S_4\) for the following confidential communication. Alice (Bob) measures the m particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) (\((S_2,S_4)\)) using the measurement base \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\), obtaining the measurement results \(k_A\) (\(k_B\)). Then, Alice (Bob) can obtain \(K_A\) (\(K_B\)) through the coding rule \(G_1\), and due to equation (1), it is known that \(K_A=K_B\), which is collectively denoted as \(K_{AB}\). Then Alice calculates the ciphertext \(\textrm{C}=M\oplus K_{AB}\) and \(S=H(M||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_A\). Next, Alice sends the bit string (C, S) to Bob.

Step 3-2: After receiving the bit string (C, S), Bob can obtain the secret message \(M^{\prime }\) by calculating \(M^{\prime }=C\oplus K_{AB}\), and calculate \(S^{\prime }=H(M^{\prime }||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_B\). If \(S^{\prime }=S\), then the communication is complete, that is, Bob has received the secret message M from Alice and the integrity of the message M is guaranteed. The same is true of Bob’s confidential communication to Alice.

Correctness and controllability analysis

In this section, our protocol is comprehensively analyzed in terms of correctness and controllability.

Correctness analysis and example

Correctness analysis

In the initialization phase, the quantum state prepared by Charlie are \(|\phi ^{+}\rangle _{12}\otimes |\phi ^{+}\rangle _{34}\). According to equation (1), we can see:

when Alice and Bob perform Bell measurements on \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) respectively, equation (2) shows that their measurement results are consistent. After encoding rule \(G_1\) is applied to the measurement results, the \(P_A\) and \(P_B\) obtained by Alice and Bob satisfies \(P_A^i||P_B^i\in \{0000,0101,1010,1111\}\). Then, after Alice and Bob announce the \(P_A\) and \(P_B\), Charlie can calculate the error rate to determine whether the channel is secure. That is, the initialization phase of the protocol is correct.

After successfully passing the eavesdropping detection, Alice and Bob utilized \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base to measure another set of particle pairs specified by Charlie, and it can be seen from equation (3) that their measurement results are consistent.

though encoding the measurements with \(G_1\) and \(G_2\), Alice and Bob are able to obtain consistent \(R_A\) and \(R_B\) and consistent \(T_A\) and \(T_B\). Alice then combines her identity information \(ID_A\) with \(R_A\), encodes \(R_A\) as \(R_A^*\) according to the encoding rule \(G_3\), and announces \(R_A^*\). Bob uses the same coding rules to calculate \(R_B^*\). Since Bob has shared Alice’s identity information beforehand, he can verify Alice’s identity by comparing \(R_A^*\) and \(R_B^*\). Authentication succeeds if and only if \(ID_A\) is correct. Therefore, the authentication phase of the protocol is accurate.

After passing each other’s identity authentication, Alice and Bob measure the remaining particle pairs based on \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base. According to equation (3), the measurement results of Alice and Bob are consistent, then the sequence obtained after encoding the measurement results using coding rule \(G_1\) is consistent, that is, \(K_A=K_B=K_{AB}\). In encryption, \(\textrm{C}=M\oplus K_{AB}\). The reversibility of the XOR operation ensures that \(M^{\prime }=C\oplus K_{AB}\) when decrypted. The strong collision property of hash function H(x) guarantees the uniqueness of \(S=H(M||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_A\). When Bob calculates \(S^{\prime }=H(M^{\prime }||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_B\), since \(T_A=T_B\) and \(M^{\prime }=M\), there must be \(S^{\prime }=S\). Any tampering will result in \(S^{\prime } \ne S\), thus breaking the integrity. Therefore, the confidential communication phase is also correct.

Example

In order to verify the correctness of our protocol, we take \(N=15\) as an example, where \(l=5\) and \(n=m=2\). Suppose Alice and Bob’s identity information is \(ID_A=01\) and \(ID_B=11\), respectively. The message Alice wants to send to Bob is \(M=0110\) and the hash value of \(M||ID_A||ID_B\) is \(H(M||ID_A||ID_B)=10\). From equation (1), it can be seen that Alice and Bob obtain the same results by performing Bell measurements or \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base measurements on the particle pairs at corresponding positions in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\). In the initialization phase, after Charlie publishes the position information of the l particles for eavesdropping detection, Alice (Bob) performs Bell measurements on the particle pairs at corresponding positions in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) (\((S_2,S_4)\)) and codes the measurement results into \(P_A\) (\(P_B\)) using the coding rule \(G_1\). Then Alice and Bob announce \(P_A\) and \(P_B\) to Charlie, respectively. According to equation (1), \(P_A^i||P_B^i\in \{0000,0101,1010,1111\}\). An error exists when \(P_{A}^{i}||P_{B}^{i}\not \in \{0000{,}0101,1010,1111\}\). And Charlie calculates the error rate utilizing \(P_A||P_B\). If the error rate is below the threshold, then the channel is secure. Then our initialization phase is correct. In the authentication phase, taking Bob authenticates Alice as an example. Suppose Alice’s measurements for the 2n particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) are \(\{|1\rangle |0\rangle ,|0\rangle |0\rangle ,|1\rangle |1\rangle ,|0\rangle |1\rangle \}\), where the positions of the particle pairs are specified by Charlie. Then \(R_A=1001\), \(T_A=01\). Subsequently, Alice executes the coding rule \(G_3\) on the \(R_A\) based on identity \(ID_{A}\) to get \(R_A^*=1010\) and publishes \(R_A^*\). After Alice announces the sequence \(R_A^*\), Bob performs the same operation on the particle pairs at the corresponding position in the sequences \((S_2,S_4)\) to obtain the sequences \(R_B=1001\), \(T_B=01\). Then Bob performs the coding rule \(G_3\) on the sequence \(R_B\) according to \(ID_{A}\) to obtain the sequence \(R_B^*\). By comparing \(R_A^*\) and \(R_B^*\), Bob can calculate the error rate. If the error rate is below the threshold, Bob successfully authenticates Alice. And Alice authenticates bob’s identity in the same way. That is, the authentication process is correct. In the confidential communication phase, suppose Alice and Bob measure the remaining particle pairs with the results \(\{|1\rangle |0\rangle ,|0\rangle |1\rangle \}\). According to Table 1, \(K_A=K_B=K_{AB}=1001\). Then Alice sends the ciphertext \(\textrm{C}=M\oplus K_{AB}=1111\) and \(S=H(M||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_A=11\) to Bob. By calculating \(M^{\prime }=C\oplus K_{AB}=0110\) and \(S^{\prime }=H(M^{\prime }||ID_A||ID_B)\oplus T_B=11\), Bob not only restores the original message M, but also ensures the data integrity of message M. That is, the confidential communication phase is also correct. To sum up, our protocol is endowed with correctness.

Controllability analysis

Our protocol achieves controllability in both the authentication phase and the confidential communication phase. In one case, the controller Charlie can prohibit the parties Alice and Bob from authenticating and communicating confidentially. Charlie does not send sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) to Alice and Bob, respectively, so that Alice and Bob are unable to authenticate and conduct subsequent confidential communications. The other case is that Charlie, the controller, allows Alice and Bob to communicate. Alice and Bob can authenticate only after Charlie publishes the location information of the particles used for authentication in the sequences \(S_1\),\(S_3\),\(S_2\),\(S_4\). After successful authentication, Alice and Bob can communicate confidentially. To summarize, Charlie, the controller, was in complete control of our protocol.

Security analysis

A secure communication protocol must incorporate a dual defense mechanism: on the one hand, it must be effective against external threats, and on the other hand, it must be able to protect against potential attacks from internal dishonest actors. Next, we will conduct a comprehensive analysis of the security of the protocol from the two dimensions of internal participant attacks62,63 and outside attacks.

Participant attacks

Charlie played a trusted role in our protocol. After Charlie sends quantum sequences to Alice and Bob respectively, they perform the steps of eavesdropping detection and identity authentication. Any dishonesty during these critical processes is not allowed, because if there is any fraud, Alice and Bob will not be able to continue with subsequent confidential communications. When Alice and Bob are authenticated, their identities are legitimate. Next, Alice and Bob measure the particle pairs in the sequence \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) using the \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base, to obtain \(K_{AB}\) for confidential communication. From equation (1), it can be seen that the measurement results of Alice and Bob occur with equal probability. That is, the measurement results of both parties are random, and neither Alice nor Bob can determine their measurement results or control \(K_{AB}\). Therefore, neither Alice nor Bob can successfully execute the participant attacks.

Outside attacks

Consider Eve as an eavesdropper intent on acquiring confidential information. She could potentially execute various types of attacks, including attacks against authentication, Trojan Horse attacks64,65, intercept-resend attacks, measure-resend attacks, entangle-measure attacks, ciphertext eavesdropping attacks and attacks in the noisy channels.

Attacks against authentication

Suppose the attacker Eve assumes Alice’s identity and communicates with Bob. Since Eve does not know Alice’s identity information \(ID_{A}\), random identity information \(ID_A^{\prime}=ID_A^{1\prime }\parallel ID_A^{2\prime }\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_A^{i\prime }\parallel \cdots \parallel ID_A^{n\prime }\) replaces Alice’s identity information \(ID_{A}\), where \(ID_{A}^{i\prime }\in \{0,1\}\). Assuming that Alice’s identity information \(ID_A^i=0\), Eve can perform the correct coding rule \(G_3\) on the binary sequence \(R_A\) when \(ID_{A}^{i\prime }=0\); When \(ID_{A}^{i\prime }=1\), the coding rule \(G_3\) performed by Eve on the sequence \(R_A\) is incorrect. Then the probability of Eve successfully disguising is 1/2. When the length of \(ID_{A}\) is n, the probability of Eve successfully camouflaging is \((1/2)^n\). So the probability that eve is detected is \(p(n)=1-(1/2)^n\). The relationship between p(n) and n is shown in Fig. 3, indicating that the probability of detecting the presence of eve approaches 1 as n approaches infinity. Similarly, when Eve tries to assume Bob’s identity, the probability of detection is closer to 1.

Trojan Horse attacks

Since the quantum sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) are transmitted only once in this scenario, Eve cannot successfully implement Trojan Horse attacks.

Intercept-resend attacks

Take the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) that Eve intercepts from Charlie to Alice in Step 1-1 as an example. After intercepting the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\), Eve randomly prepares \(l+4n+m\) particle pairs and sends them to Alice in place of the sequence \((S_1,S_3)\). Subsequently, eavesdropping detection is carried out. After Alice and Bob measure l particles used for eavesdropping detection, 16 cases (as shown in Table 4) will occur when the corresponding \(P_A^i||P_B^i\) is coded using the coding rule \(G_1\). From Step 1-2, it can be seen that \(P_A^i||P_B^i\) will only occur in four cases without eavesdropping. Therefore, the probability that Eve gets the \(P_A^i||P_B^i\) correctly is 1/4. Hence, the probability that the attacker successfully passes the eavesdropping detection is \((1/4)^l\). As l increases, the value of \((1/4)^l\) approaches 0 infinitely. Eve’s attacks can therefore be detected in eavesdropping detection in Step 1-2. Therefore, the protocol can resist intercept-resend attacks.

Measure-resend attacks

Take the example of Eve executing a measure-resend attacks on the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) that Charlie sends to Alice in Step 1-1. Eve randomly selects a set of measurement bases \(MB_A=MB_A^1\parallel MB_A^2\parallel \cdots \parallel MB_A^i\parallel \cdots \parallel MB_A^N\), Where \(MB_A^i\) is randomly selected from the Bell-base and \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base, measures the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\), and prepares sequences of the same states based on the measurements, and then sends the fake sequences to Alice. However, Charlie only announces the locations of the particle pairs used for eavesdropping detection after confirming that Alice has received the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\). Since Eve could not predict which pairs of particles would be used for the eavesdropping detection, she could not choose the correct measurement bases to measure the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\). The probability that Eve correctly selects a measurement base is 1/2, then the probability of successfully passing the eavesdropping detection is \((1/2)^l\). When l is infinite, the value of\((1/2)^l\) approaches 0. And Eve’s intervention would break the entanglement between the particles. As a result, Eve’s faked sequences will not be able to escape detection in subsequent eavesdropping detection. Therefore, the protocol is resistant to measure-resend attacks.

Entangle-measure attacks

When Charlie transmits quantum sequences to Alice and Bob respectively, the attacker Eve intercepts them and prepares the auxiliary particle \(\left| E\right\rangle\) to perform the unitary operation U on each \(|\phi ^+\rangle _{12}\otimes |\phi ^+\rangle _{34}\). Then the following state is obtained:

It satisfies the following conditions:

and

where \(\alpha ,\beta ,\varepsilon ,u=0,1,2,3\) and \(\beta \ne \varepsilon\).

When Alice and Bob use \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base to measure the particle pairs at corresponding positions in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\), respectively, they get four possible results \(|00\rangle ,|01\rangle ,|10\rangle ,|11\rangle\). For example, if Alice’s measurement result is \(|00\rangle\), Bob’s particle pairs will be \(|00\rangle\). Therefore, the Alice-Bob-Charlie hybrid system can be described as:

The probability that Alice’s (Bob’s) measurement result is \(|00\rangle ,|01\rangle ,|10\rangle ,|11\rangle\) is \(P_{A_{00}}\), \(P_{A_{01}}\), \(P_{A_{10}}\), \(P_{A_{11}}\) (\(P_{B_{00}}\), \(P_{B_{01}}\), \(P_{B_{10}}\), \(P_{B_{11}}\)), respectively. That is:

In the absence of eavesdropping and with a large number of particles, the Shannon entropy of the Alice system is \(H(A)=h\big (P_{A_{00}},P_{A_{01}},P_{A_{10}},P_{A_{11}}\big )=1\). Since Bob can infer the states of Alice’s particle pairs by measuring his own particle pairs, the conditional entropy is \(H(A|B)=0\), and the mutual information between Alice and Bob is \(I(B;A)=H(A)-H(A|B)=1\).

In addition, the mutual information between the attacker Eve and Bob is I(B : E). To ensure that Bob cannot detect the intervention of the attacker Eve when measuring the particle pairs, Eve must make:

However, in this way the mutual information between Bob and Eve is \(I(B:E)=0\). Therefore, \(I(B:A)>I(B:E)\). Eve cannot gain any valuable information by utilizing entangle-measure attacks. So our protocol defends against entangle-measure attacks.

Ciphertext eavesdropping attacks

In Step 3-1, assume that Eve intercepts ciphertext C and S, because Eve does not know \(K_{AB}\), she cannot recover the plaintext message M, nor can she verify the integrity of the message M. Therefore, the protocol can resist ciphertext eavesdropping attacks.

Attacks in the noisy channels

In our analysis, the confidential communication protocol is assumed to operate in the noiseless quantum channels. However, Eve might attempt to conceal her attacks in the quantum noisy channels. The quantum bit error rate (QBER) caused by noise is denoted as e, which is approximately between \(2\%\) and \(8.9\%\), depending on factors such as distance66,67,68,69,70. If Eve’s attack results in the QBER below e, her actions will go undetected by the participants. For our confidential communication protocol, the eavesdropping detection rate for each particle is at least 20%, which exceeds the QBER e. Therefore, by selecting an appropriate eavesdropping detection threshold71, Eve’s attacks can still be detected in the quantum noisy channels.

Experimental and qubit efficiency analysis

This section explores the experimental analysis of the protocol and the qubit efficiency analysis, providing a detailed discussion.

Experiment analysis in ideal channel

The following process will be simulated: Charlie prepares Bell states \(|\phi ^+\rangle\), and upon Alice and Bob receive the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\) from Charlie, they will perform Bell measurements and \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base measurements on the corresponding particle pairs.

The measurement results of Fig. 4.

To prepare the Bell state \(|\phi ^+\rangle\), Charlie operates on two qubits \(q_0\) and \(q_1\) in turn. First, the Hadamard gate is applied to \(q_0\) to change it from the initial state \(|0\rangle\) to the superposition state \(1/\sqrt{2}(|0\rangle +|1\rangle )\). Then, the CNOT gate is applied to \(q_0\) and \(q_1\), which entangles the state of \(q_1\) with the state of \(q_0\), resulting in a Bell state \(|\phi ^+\rangle =1/\sqrt{2}(|00\rangle +|11\rangle )\). The quantum circuit72 is shown in Fig. 4. To verify whether the Bell state prepared using a quantum circuit is \(|\phi ^+\rangle\), we measure it. In Fig. 5, the measurement shows that states \(|00\rangle\) and \(|11\rangle\) each occur with 50% probability, which is exactly consistent with the properties of the \(|\phi ^+\rangle\). Therefore, the \(|\phi ^+\rangle\) state can be successfully prepared by this quantum circuit. Then, Charlie can prepare the required quantum state sequences for the protocol by repeatedly running the quantum circuit. The length of the sequence prepared by Charlie is \(N = l + 4n + m\), where l is the number of particles used for eavesdropping detection, n is the length of the identity information, and m is the length of the communication message. In practical communication, to balance security and efficiency, it is recommended to set \(l = 1/2(m + 4n)\) to ensure the strength of eavesdropping detection. However, this parameter is not fixed, it has some flexibility, can be adjusted according to different security needs. In case of high security requirements, the value of l can be appropriately increased to exceed the recommended range to further strengthen security. The length of identity information n and message length m can be dynamically adjusted according to actual communication needs.

According to equation (1), after Alice and Bob perform Bell measurements on the particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\), the possible outcomes are \(|\phi ^+\rangle |\phi ^+\rangle\), \(|\phi ^-\rangle |\phi ^-\rangle\),\(|\psi ^+\rangle |\psi ^+\rangle\),\(|\psi ^-\rangle |\psi ^-\rangle\), which occur with equal probability. The quantum circuit is shown in Fig. 6 and measurement results are shown in Fig. 7. The quantum circuit is executed 1024 times, yielding measurement results of \(|\phi ^+\rangle |\phi ^+\rangle\),\(|\phi ^-\rangle |\phi ^-\rangle\),\(|\psi ^+\rangle |\psi ^+\rangle\) and \(|\psi ^-\rangle |\psi ^-\rangle\) respectively. The frequencies for each state were observed to be 255, 257, 254, and 258 occurrences in that order, which aligns with the anticipated outcomes.

The measurement results of Fig. 6.

According to Eq. (1), after Alice and Bob perform \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base measurements on the particle pairs in the sequences \((S_1,S_3)\) and \((S_2,S_4)\), they get four possible results \(|0000\rangle\),\(|0101\rangle\),\(|1010\rangle\),\(|1111\rangle\), which occur with equal probability. The quantum circuit is shown in Fig. 8 and measurement results are shown in Fig. 9. The quantum circuit is executed 1024 times, yielding measurement results of \(|0000\rangle\),\(|0101\rangle\),\(|1010\rangle\) and \(|1111\rangle\) respectively. The frequencies for each state were observed to be 255, 251, 254, and 264 occurrences in that order, which aligns with the anticipated outcomes.

The measurement results of Fig. 8.

Experiment analysis in noisy channel

During the transmission of quantum states, they are inevitably affected by channel noise. Noise can lead to loss or error of quantum information. Among them, bit flip noise and depolarization noise are two main noise models.

Bit flip noise describes the phenomenon where a qubit undergoes random flips between the computational basis states (\(|0\rangle\) and \(|1\rangle\)). Specifically, if the initial state is \(|0\rangle\), after being subjected to bit flip noise, there is a certain probability it will transition to \(|1\rangle\), and vice versa. This noise can be represented by the Pauli matrix X in its mathematical form: \(\mathscr {E}(\rho ) = (1-p)\rho + pX\rho X^\dagger\), where \(\rho\) is the density matrix of the quantum state and p is the probability of the bit flip. Depolarization noise describes the phenomenon where a quantum state randomly undergoes one of three Pauli errors (X, Y, Z) or remains the same when a qubit interacts with the environment in an uncontrollable manner. The mathematical form of depolarization noise is: \(\mathscr {E}(\rho ) = (1-p)\rho + \frac{p}{3}(X\rho X^\dagger + Y\rho Y^\dagger + Z\rho Z^\dagger )\), where p is the probability of an error.

In order to simulate the noise interference that may be encountered, we introduced 5% bit flip noise and 5% depolarization noise in the measurement process. Figures 10 and 11 show the results of Bell and \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base measurements with 5% bit flip noise, respectively. Figures 12 and 13 show the results of Bell and \(\textrm{Z}\otimes \textrm{Z}\)-base measurements with 5% depolarization noise, respectively. It can be seen that the error levels of both types of noise are low, and the proposed protocol still has good robustness when dealing with these two common noises.

Qubit efficiency analysis

At present, the bit efficiency of secure quantum communication is mainly measured by the Cabello qubit efficiency73: \(\eta =\frac{c}{q+b}\), where c is the number of bits of secret information, q is the total number of qubits transmitted in the protocol, and b is the total number of classical bits used in the transmission process. In this protocol, the length of secret information is \(c=2m\). The number of Bell states prepared by Charlie is \(2(l+4n+m)\), so the total number of qubits transmitted is \(q=4(l+4n+m)\). The total number of classical bits is \(b=l+5n+2m\). Therefore, the qubit efficiency of this protocol is: \(\eta =\frac{2m}{5l+21n+6m}\). Let \(l=(4n+m)/2\), then the qubit efficiency is: \(\eta =\frac{4m}{17m+62n}\). Figure 14 depicts the curve of qubit efficiency \(\eta\) changing with parameters m and n, and intuitively shows the dynamic change of qubit efficiency under different parameter combinations.

The comparison between the quantum confidential communication protocol proposed by us and other related protocols is shown in Table 5. The protocol in this paper uses Bell state as a quantum resource. Compared with W state in Yi’s46 and GHZ state in Wang’s13, the preparation technology of Bell state is more mature and easier to realize. In terms of function, this protocol not only has the function of identity authentication, but also ensures the integrity of the message, so as to make up for the shortcomings of protocols13,35,46. In addition, this protocol only needs one quantum sequence transmission, which significantly reduces the possible loss and noise during quantum sequence transmission compared with the multiple transmission of other schemes. In terms of efficiency, compared with other protocols, the efficiency of this protocol can reach about 23.53% under the same conditions, which has a relatively ideal feasible efficiency.

Conclusion

In the field of smart healthcare services, it is crucial to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of data when medical specialists provide surgical guidance and diagnostic scheme to remote patients. Therefore, this paper proposes a novel two-party controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol, which is based on Bell states to ensure the security of data transmission. In this process, the trusted quantum controller Charlie (representing the hospital information center) plays a key role, assisting the two parties involved Alice (representing the medical specialist) and Bob (representing the patient) to complete the identity authentication in the first place. Once the two parties have successfully authenticated each other, they will use the entanglement properties of the Bell states to securely generate the shared keys. The shared keys will be used to encrypt the message and its digest, thereby ensuring the security of the data, preventing leakage or tampering, and safeguarding the confidentiality and integrity of the communication data. The significant advantage of this protocol is that it not only ensures the confidentiality and integrity of the communication content, but also effectively defends against man-in-the-middle attacks through authentication. The quantum sequence involved in the protocol is transmitted only once, reducing the loss and noise effects caused by multiple transmissions. And the controller Charlie only needs to prepare relatively mature quantum resource, while the participants Alice and Bob only need to perform simple measurement operations. In addition, the protocol design can effectively resist from the participant and outside attacks, enhance the security of the communication process. Taken together, this protocol is particularly suitable for patients in remote areas with limited medical resources to provide them with safer and more reliable medical services.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sai, S., Hassija, V., Chamola, V. & Guizani, M. Federated learning and NFT-based privacy-preserving medical-data-sharing scheme for intelligent diagnosis in smart healthcare. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 5568–5577. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3308991 (2024).

Gong, W. et al. Embracing self-powered wearables for intelligent healthcare data management. IEEE Internet Things J. 11, 25674–25681. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3381233 (2024).

Soni, P., Pradhan, J., Pal, A. K. & Islam, S. H. Cybersecurity attack-resilience authentication mechanism for intelligent healthcare system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 19, 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3179429 (2023).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science 124–134 https://doi.org/10.1109/SFCS.1994.365700 (1994).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information 10th Anniversary edn. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Folland, G. B. & Sitaram, A. The uncertainty principle: A mathematical survey. J. Fourier Anal. Appl. 3, 207–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02649110 (1997).

Zhang, W. et al. A device-independent quantum key distribution system for distant users. Nature 607, 687–691. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04891-y (2022).

Zhou, S., Xie, Q. M. & Zhou, N. R. Measurement-free mediated semi-quantum key distribution protocol based on single-particle states. Laser Phys. Lett. 21, 065207 (2024) https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:269536778.

Xu, F. et al. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 025002–025062. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.92.025002 (2020).

Zhu, H., Wang, C. & Li, Z. Semi-honest three-party mutual authentication quantum key agreement protocol based on GHZ-like state. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 60, 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-020-04692-x (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. A novel three-party mutual authentication quantum key agreement protocol with GHZ states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 61, 245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-022-05220-9 (2022).

He, Y. F. & Ma, W. P. Quantum key agreement protocols with four-qubit cluster states. Quantum Inf. Process. 14, 3483–3498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-015-1060-7 (2015).

Wang, C. & Zhu, H. A hybrid dynamic n-party quantum key exchange protocol based on three-particle GHZ states. Quantum Inf. Process. 23, 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-024-04271-7 (2024).

Qian, Y., Gui, C., Liu, B., Huang, W. & Xu, B. J. Quantum identity authentication based on round robin differential phase shift communication line. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 61, 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-022-04988-0 (2022).

Lou, X. P., Wang, S., Ren, S. X., Zan, H. R. & Xu, X. J. Quantum identity authentication scheme based on quantum walks on graphs with IBM quantum cloud platform. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 61, 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-022-04986-2 (2022).

Gong, L. H., Ye, Z. J., Liu, C. & Zhou, S. One-way semi-quantum private comparison protocol without pre-shared keys based on unitary operations. Laser Phys. Lett. 21, 035207. https://doi.org/10.1088/1612-202X/ad21ec (2024).

Gong, L. H., Li, M. L., Cao, H. & Wang, B. Novel semi-quantum private comparison protocol with Bell states. Laser Phys. Lett. 21, 055209. https://doi.org/10.1088/1612-202X/ad3a54 (2024).

Zhou, N. R., Chen, Z. Y., Liu, Y. Y. & Gong, L. H. Multi-party semi-quantum private comparison protocol of size relation with d-level GHZ states. Adv. Quantum Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202400530 (2024).

Tian, Y., Li, J., Chen, X. B., Ye, C. Q. & Li, H. J. An efficient semi-quantum secret sharing protocol of specific bits. Quantum Inf. Process. 20, 217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-021-03157-2 (2021).

Tian, Y., Wang, J., Bian, G., Chang, J. & Li, J. Dynamic multi-party to multi-party quantum secret sharing based on Bell states. Adv. Quantum Technol. 7(7), 2400116 (2024).

Tian, Y., Zhang, N. Y. J., Ye, C. Q., Bian, G. Q. & Li, J. Different secure semi-quantum summation models without measurement. EPJ Quantum Technol. 11, 217. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-024-00247-9 (2024).

Gong, L. H., Ding, W., Li, Z., Wang, Y. Z. & Zhou, N. R. Quantum k-nearest neighbor classification algorithm via a divide-and-conquer strategy. Adv. Quantum Technol. 7, 2300221. https://doi.org/10.1002/qute.202300221 (2024).

Bennett, C. H. & Brassard, G. Quantum cryptography: Public-key distribution and coin tossing. In Proceedings IEEE Conference on Computers, Systems, and Signal Processing, Bangalore, India, 175–179 (1984).

Ramos, M., Pinto, A. & Silva, N. Polarization based discrete variables quantum key distribution via conjugated homodyne detection. Sci. Rep. 12, 6135. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10181-4 (2022).

Alia, O. et al. Dynamic DV-QKD networking in trusted-node-free software-defined optical networks. J. Lightwave Technol. 40, 5816–5824. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2022.3183962 (2022).

Djordjevic, I. B. Optimized-eight-state CV-QKD protocol outperforming gaussian modulation based protocols. IEEE Photonics J. 11, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOT.2019.2921521 (2019).

Zhang, J., Wang, X., Xia, F., Yu, S. & Chen, Z. Multiple-quadrature-amplitude-modulation continuous-variable quantum key distribution realization with a downstream-access network. Phys. Rev. A 109, 052429. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.052429 (2024).

Lo, H., Curty, M. & Qi, B. Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 130503–130507. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.130503 (2012).

Sun, H. Z., Shang, T. & Liu, J. W. Measurement-device-independent QKD based on orbital angular momentum with dual detectors. In 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC). Limassol, Cyprus, 2028–2032 https://doi.org/10.1109/IWCMC48107.2020.9148215 (2020).

Chen, Y. Research on the application of four dimensional MDI-QKD protocol based on phase polarization coding in quantum communication systems. In 2023 5th International Conference on Frontiers Technology of Information and Computer (ICFTIC). Qingdao, China, 911–914 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICFTIC59930.2023.10456085 (2023).

Yan, R., Dai, J., Wang, Y., Xu, Y. & Liu, A. Q. Quantum-key-distribution based microgrid control for cybersecurity enhancement. In 2021 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting (IAS). Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2022.3159314 (2021).

Singamaneni, K. K., Muhammad, G. & Ali, Z. A novel multi-qubit quantum key distribution ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption model to improve cloud security for consumers. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70, 1092–1101. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2023.3331306 (2024).

Zhou, N., Zeng, G. & Xiong, J. Quantum key agreement protocol. Electron. Lett. 40, 1149–1150 (2004).

He, Y. F. & Ma, W. P. Two-party quantum key agreement against collective noise. Quantum Inf. Process. 15, 5023–5035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-016-1436-3 (2016).

Wang, C., Zhang, Q., Liang, S. & Zhu, H. Secure mutual authentication quantum key agreement scheme for two-party setting with key recycling. Quantum Inf. Process. 23, 139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-024-04356-3 (2023).

Zhu, K. N. & Wang, Y. Q. Three-party semi-quantum key agreement protocol. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 59, 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-019-04288-0 (2020).

Wang, W., Zhou, B. M. & Zhang, L. The three-party quantum key agreement protocol with quantum Fourier transform. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 59, 1944–1955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-020-04467-4 (2020).

Zhou, N. R., Liao, Q. & Zou, X. F. Multi-party semi-quantum key agreement protocol based on the Four-qubit Cluster states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 61, 114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-022-05102-0 (2022).

Wu, Y. T., Chang, H., Guo, G. D. & Lin, S. Multi-party quantum key agreement protocol with authentication. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 60, 4066–4077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-021-04954-2 (2021).

Tang, R. H., Zhang, C. & Long, D. Y. An efficient circle-type multiparty quantum key agreement protocol with single particles. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 34, 2050199. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217979220501994 (2020).

Ho, J. et al. Experimental quantum conference key agreement. In 2021 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO). USA, 1–2 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe0395 (2021).

He, Y. F. & Ma, W. P. Two quantum key agreement protocols immune to collective noise. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 56, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-016-3165-x (2017).

Li, L., Zhou, R. G. & Zhang, X. X. Three-party quantum key agreement protocol based on logical four-particle Cluster state to resist collective noise. Quantum Inf. Process. 22, 453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-023-04206-8 (2017).

Tang, J., Shi, L. & Wei, J. Controlled quantum key agreement based on maximally three-qubit entangled states. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 34, 2050201. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984920502012 (2020).

He, Y. F. et al. New controlled quantum key agreement protocols based on Bell states. J. China Univ. Posts Telecommun. 29, 42–50 (2022) https://jcupt.bupt.edu.cn/EN/10.19682/j.cnki.1005-8885.2022.2018.

Yi, H. M., Zhou, R. G. & Xu, R. Q. Semi-quantum key agreement protocol using W states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 62, 212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-023-05467-w (2023).

Xu, X. & Lou, X. Improvement and flexible multiparty extension of semi-quantum key agreement protocol. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 62, 252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-023-05504-8 (2023).

He, Y. F., Pang, Y. B. & Di, M. Mutual authentication quantum key agreement protocol based on Bell states. Quantum Inf. Process. 21, 290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-022-03640-4 (2022).

Xu, Y. G., Wang, C. N., Chen, K. F. & Zhu, H. F. A novel three-party mutual authentication quantum key agreement protocol with GHZ states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 61, 245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-022-05220-9 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Measurement-device-independent quantum identity authentication based on single photon. In Artificial Intelligence and Security, ICAIS 2020, Communications in Computer and Information Science, Vol. 1253 (Springer, Singapore, 2020), 337–345 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8086-4_31.

Li, G. D., Liu, J. C., Wang, Q. L. & Sun, W. Q. Employing single photons for measurement-device-independent quantum secure direct communication with identity authentication. IEEE Commun. Lett. 28, 473–477. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2024.3354250 (2024).

Lim, N. H., Choi, J. W., Kang, M. S., Yang, H. J. & Han, S. W. Quantum authentication method based on key-controlled maximally mixed quantum state encryption. EPJ Quantum Technol. 10, 35. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-023-00193-y (2023).

Jian, L. Y., Wang, Y. Q., Chen, G., Zhou, Y. & Liu, S. M. Quantum identity authentication using a Hadamard gate based on a GHZ state. J. Phys. B 56, 075502. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/acbd27 (2023).

Hong, Ch., Heo, J., Jang, J. G. & Kwon, D. Quantum identity authentication with single photon. Quantum Inf. Process. 16, 236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-017-1681-0 (2017).

Zhang, S., Chen, Z. K., Shi, R. H. & Liang, F. Y. A novel quantum identity authentication based on Bell states. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 59, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10773-019-04319-w (2020).

Zhang, C. H., Fan, Y. T., Zhang, C. M., Li, J. & Wang, Q. Twin-field quantum digital signatures. Opt. Lett. 46, 3757. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.426369 (2021).

Inoue, K. & Honjo, T. Differential-quadrature-phase-shift quantum digital signature. Opt. Express 30, 42933–42943. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.468156 (2022).

Latif, M. K., Jacinto, H. S., Daoud, L. & Rafla, N. Optimization of a quantum-secure sponge-based hash message authentication protocol. In 2018 IEEE 61st International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS). Windsor, Canada, 984–987 https://doi.org/10.1109/MWSCAS.2018.8623880 (2018).

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Ahmad, H. & Wei, Z. Message authentication with a new quantum hash function. Comput. Mater. Contin. 59(2), 635–648. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2019.05251 (2019).

Kang, M. S., Kim, Y. S., Choi, J. W., Yang, H. J. & Han, S. W. Experimental quantum message authentication with single qubit unitary operation. Appl. Sci. 11, 2653. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062653 (2021).

Perez, N. An Efficient Quantum Message Authentication Scheme. M.S. thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa (2022).

Qin, S. J., Gao, F., Wen, Q. Y. & Zhu, F. C. Improving the security of multiparty quantum secret sharing against an attack with a fake signal. Phys. Lett. A 357, 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2006.04.030 (2006).

Gao, F., Qin, S. J., Wen, Q. Y. & Zhu, F. C. A simple participant attack on the brádler-dušek protocol. Quantum Inf. Comput. 7, 329–334 (2007) https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:11938897.

Deng, F. G., Li, X. H., Zhou, H. Y. & Zhang, Z. J. Improving the security of multiparty quantum secret sharing against Trojan horse attack. Phys. Rev. A 72, 044302–044305. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.72.044302 (2005).

Cai, Q. Y. Eavesdropping on the two-way quantum communication protocols with invisible photons. Phys. Lett. A 351, 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2005.10.050 (2006).

Jennewein, T., Simon, C., Weihs, G., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. Quantum cryptography with entangled photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4729–4732 (2000).

Stucki, D., Gisin, N., Guinnard, O., Ribordy, G. & Zbinden, H. Quantum key distribution over 67 km with a plug and play system. New J. Phys. 4, 41.1-41.8 (2002).

Hughes, R. J., Nordholt, J. E., Derkacs, D. & Peterson, C. G. Practical free-space quantum key distribution over 10 km in daylight and at night. New. J. Phys. 4, 43.1-43.14 (2002).

Gobby, C., Yuan, Z. L. & Shields, A. J. Quantum key distribution over 122 km of standard telecom fiber. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3762–3764 (2004).

Beveratos, A. et al. Single photon quantum cryptography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 187901 (2002).

Lin, J. & Hwang, T. New circular quantum secret sharing for remote agents. Quantum Inf. Process. 12, 685–697 (2013).

Andrew, W. C. The IBM Q experience and QISKit open-source quantum computing software. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. 2018, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:67150463 (2018).

Cabello, A. Quantum key distribution in the Holevo limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5635–5638. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5635 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61802302) and the Basic Research Project of Natural Science of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2021JM-462).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.H. and J.Q.F. conceived the original idea. J.Q.F. analyzed the results and wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Fan, J. & Zhang, Y. Controlled quantum authentication confidential communication protocol for smart healthcare. Sci Rep 15, 18094 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02448-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02448-3