Abstract

The degradation of soil through erosion poses a major environmental concern on a global scale, adversely affecting the chemical, biological, and physical properties of both soil and water. Precisely identifying the main sediment sources within a watershed is vital for developing targeted management strategies aimed at reducing erosion and improving water quality. Sediment sourcing is a commonly employed approach to achieve this goal. Some sediment sourcing methods not only determine the contributions of different sources but also provide estimates of average erosion/sedimentation intensity and sediment budget components. Therefore, the present study was conducted with the aim to compare the average soil erosion intensity and sediment yield in the past 100–120, 60–70, and 15 years within the control sub-watershed of the Khamsan representative-paired watershed. Furthermore, the contribution of various land uses to sediment yield, such as orchards, irrigated agriculture, rangeland, and rainfed agriculture were compared using geochemical fingerprinting characteristics obtained in 2021 with the corresponding results derived from the 137Cs method for the last 60–70-year period. In order to achieve the research objectives, a total of 106 soil samples were systematically collected with appropriate distribution in different land uses for sediment source fingerprinting using radionuclides and other indicators. The findings indicated that during the two recent periods, spanning 100–120 years and 60–70 years, the average gross erosion was estimated at 2.92 and 5.25 t ha−1 y−1, respectively, and the average net erosion was estimated at 2.85 and 5.05 t ha−1 y−1, respectively. Furthermore, the contributions of rainfed agriculture and rangeland to sediment yield in 2021 were 72.26% and 7.96%, respectively, and using the 137Cs method for the 60–70-year period, they were 85.49% and 8.93%, respectively. The study’s findings revealed also a decline in sediment yield over the past 60–70 years, compared to the measurements obtained during the last 15 years. This decrease can be primarily attributed to factors that include the abandonment of rainfed agricultural lands, a decrease in rainfall, and a reduction in sediment transport caused by tillage in waterways draining to the sub-watershed outlet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Massive population growth and intensification of human activities have led to the depletion of non-renewable soil resources and have undermined the United Nations sustainable development goals, especially those related to food security1. While sediment is a natural component of river systems and even essential in many aquatic ecosystems, excessive inventory of fine sediments often results in the alteration of river systems and aids in the downstream transport of pollutants2. Silvicultural practices, deforestation, urban and rural development, construction activities, and forest fires, have significantly contributed to the rise in sediment production and its transfer to rivers over the past decades3. Identifying the trend and magnitude of erosion and sediment yield changes in a watershed, known as erosion history, is a strategic tool for optimizing decision-making regarding macroplanning soil management in each watershed. Additionally, suitable measures must be applied along the primary transport routes from source areas to watershed outlets, taking into account varying climatic conditions and watershed characteristics4. Therefore, awareness of the proportional contributions of different sediment sources constitutes a critical prerequisite to establish effective countermeasures and minimizing impacts of the sediment delivered downstream5.

Sediment sourcing technology relies on measuring physical or biogeochemical fingerprinting tracers in soil and sediment, along with employing statistical techniques and hybrid models5, and offers a direct approach to identifying the characteristics, locations, and relative contributions of sediment sources6. In this context, tracers should be able to distinguish significant differences between potential sediment sources because they remain stable throughout the processes of erosion, transport, and sedimentation, or any changes in them should occur predictably and measurably7. Sedimentary properties, including magnetic characteristics, radionuclides, stable isotopes, major elements, and geochemistry fingerprinting, have been effectively employed to identify and trace sediment origins6.

The first study on sediment sourcing using geochemical fingerprinting was conducted in the early 1980s. Geochemical tracers, including major and tracer elements, have been widely used in sourcing studies5 and employed to determine various sources and their respective contributions to sediment yield8. Materials originating from diverse parent rocks typically exhibit distinct geochemical fingerprinting9 and sediments resulting from the erosion of these geochemical indicators retain them, making it possible to determine the relative contributions10. In recent decades, numerous studies have been conducted to trace sediment sourcing using geochemical fingerprinting characteristics (see, among the others11,12,13,14,15,). In all cases, the influence of land use or land cover, whether natural or human-induced is considered, in the yield of bed or suspended sediments or wind erosion, can be distinguished.

Another category of indicators used for sediment sourcing is represented by fallout radionuclides that include mainly 90Sr, 137Cs, 210Pbex, and 7Be. The first studies to estimate soil erosion using radionuclides were conducted by Menzel (1960) which made use of 90Sr measurements to compare radionuclide activities in soils and sediments on cultivated sites16. Other authors17 pioneered the use of the anthropogenic radioactive isotope 137Cs, characterized by a half-life of 30.1 years. 137Cs entered the environment via precipitation during the 1950–1970s as a result of nuclear tests and, due to its ability to provide spatial distribution maps of erosion and sediment yield, has then been widely recognized worldwide for tracking sediments and their changes, and for producing maps of soil erosion and/or sediment budget18. A valid alternative to 137Cs is given by the unsupported 210Pb, a naturally occurring radioactive isotope with a half-life of 22.3 years. 210Pb is part of the 238U decay series, which decays to 210Pb in the soil and the Earth’s atmosphere19 and, in view of its behavior similar to 137Cs, it was also recognized as a potential complement to 137Cs where the latter is under detection limits. 210Pbex and 137Cs are in fact quickly absorbed by surface soil particles, including clay particles and soil organic matter20, thus, they can serve as indicators of soil erosion or accumulation at specific locations. Furthermore, comparing 210Pbex or 137Cs in soil and sediments from different sources can determine the relative contribution of sediment from these sources21. Due to the large presence of these fallout radionuclides worldwide and their different half-life, the mean soil erosion rate resulting from their use can be considered over a long period of approximately 100–120 years for 210Pbex, and 60–70 years for 137Cs, for which the atmospheric fallout is episodic and limited to the nuclear experiments in the period 1954–1980, as well as nuclear accidents such as Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) (see, among the others22,23,).

Several researchers (e.g19,24,24,25,26,28.,) have emphasized that the simultaneous application of 210Pbex and 137Cs can be used in order to compare the history of erosion and its temporal changes according to the generalization of the mean values of erosion and sediment yield related to the different timespan. Other researchers (e.g29,29,31.,) explored further the simultaneous use of two or three radionuclides, including 239–240Pu, and 7Be, to provide information of erosion rates at different temporal scale.

In the study area, research on soil erosion and sediment yield has been conducted with different approaches in which the results of traditional methods and different models have been integrated with the results of the radionuclides methods. For example, Khaledi Darvishan et al.32 analyzed spatial and temporal changes in soil erosion using RUSLE model. Khodamoradi et al.33 examined the effectiveness of watershed management practices in minimizing soil erosion. Sedighi et al.27 examined the impact of land use on sediment budget components. Azami et al.34 compared the results of different methods for estimating sediment delivery ratios and, Zarei et al.35 combined the use of radionuclides with topographic metrics to analyze and estimate the sediment budget components. Almost all previous studies have emphasized that rainfed agricultural lands are the main source of erosion and sediment yield in the study area. It should be noted that in Iran, most of the rainfed agricultural lands are located in this region. In this context, the use of representative-paired watersheds is of considerable value due to their educational and research role, as well as their capacity to extrapolate findings to wider areas.

In this study, an attempt was made to compare the results obtained from 210Pbex and 137Cs measurements with observational sediment data collected over the past 15 years, to determine trends in erosion history within the Khamsan representative-paired watershed located in Kurdistan Province, western Iran. Additionally, geochemical fingerprinting was used to determine the current contribution of each land use in sediment yield, which was then compared with the average contribution of each land use over the past 60–70 years, as determined using the 137Cs technique. This approach also allowed for an investigation of changes in land use patterns over time.

Recent studies have advanced techniques that utilize the concentration of 137Cs to precisely determine sediment transport patterns in watersheds. These methods have significantly improved the identification of primary erosion and sedimentation zones35. Additionally, optimization algorithms have been introduced to refine fingerprinting approaches based on 137Cs, yielding more accurate predictions of sediment delivery ratios36. Furthermore, advancements in combining 137Cs with other elements such as 210Pbex, or employing hydrological methodologies, have enhanced the analysis of sediment sources and reduced uncertainties in estimations.

Materials and methods

Study area

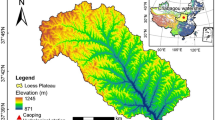

Located across an area of 4336 hectares, the Khamsan representative-paired watershed is located within the geographical coordinates of 47° 4′ 6″ to 47° 10′ 44″ East and 34° 57′ 41″ to 35° 1′ 29″ North in Kurdistan Province27. This research was carried out in the control sub-watershed, situated in the southwestern part of the watershed (Fig. 1), where no soil and water conservation measures have been implemented. Utilizing a digital elevation model (DEM) derived from photogrammetry drone data, the drainage area of the control sub-watershed was determined to be approximately 102.14 hectares, with a mean elevation of 1712 m above sea level and an average slope of 28%. According to data from the Khamsan climatological station, located 500 m northeast of the study sub-watershed, the annual mean precipitation is 428 mm, and the average temperature is 12.5 °C. The study area encompasses four distinct land cover types: orchard, rangeland, irrigated agriculture, and rainfed agriculture. Surface erosion is identified as the predominant erosion type, affecting both this sub-watershed and the entire Khamsan representative-paired watershed37.

The control sub-watershed within the Khamsan representative-paired watershed situated in Kurdistan province, Iran. (The photographs were taken by the authors in the study sub-watershed. The maps were generated using ArcMap 10.8.2, https://www.esri.com).

In areas close to the watershed outlet, the soil thickness extends beyond one meter, classified under hydrologic group B, with a clay loam texture suitable for irrigated agriculture. In the central region of the watershed, soil depth varies between 50 and 60 cm, and belongs to hydrologic group C, mainly under rainfed agriculture. In these two areas, plowing activities have disrupted the natural stratification of the soil. Additionally, in the upper area of the watershed, the soil depth ranges from 10 to 20 cm, categorized under hydrologic group C, where the natural layering of the soil remains intact, and the dominant rangeland vegetation includes Astragalus and Festuca species.

On the other hand, roughly 65% of area within the sub-watershed consists of dark gray, black, and silty shale, phyllitic shale, and yellow shales, accompanied by small amounts of sandstone and micritic limestone (Kvsh2). The main channel is surrounded by alluvial sediments, covering 15% of the area (Qt2), and light blue tuff with calcite veins covers 14% of the area (Kl22). Additionally, pink to purple pelagic limestone covers 4% (Kl32) and calcareous shale, ranging from light green to gray, constitutes 2% of the watershed area (Kf2), forming the geological characteristics of the sub-watershed Fig. 1.

Establishing a sediment budget using 210Pbex and 137Cs method

Selecting a reference area and soil sampling

The first step in determining erosion and sediment rates using 210Pbex and 137Cs is identifying reference sites. These areas should remain undisturbed from the time the radioisotopes entered the soil until sampling, and should not be affected by erosion and/or sedimentation processes. Therefore, there should be minimal changes in the amount of 210Pbex and 137Cs, aside from their natural decay. The inventories (Bq m−2) at these sites represent the total fallout of 210Pbex and 137Cs in the area up to the time of sampling. Selecting reference sites requires consideration of several criteria: these locations should be near the study area, have similar elevation, deep soil, no signs of erosion or deposition, and preferably minimal slope, with permanent vegetation cover. Generally, reference locations comprise conservation zones, including areas like cemeteries and parks38.

In this study, the reference areas of Muchesh and Ghoorogh, located 4 km from the basin in old cemeteries that have not been used for burial for over 60–70 years and where no agricultural or grazing activities, were selected. To ensure accuracy, 12 samples were gathered from the reference areas, with coefficients of variation for 210Pbex and 137Cs activities being 15.05% and 19.09%, respectively, and within the permissible limit of less than 20%37. Four samples were taken using incremental (layered) sampling, and the remaining samples were taken using in-depth (bulk or composite) sampling to examine variations in radioactive element activity in the soil profile and depth distribution.

Images of the reference area, incremental and bulk sampling, and sample preparation for soil and sediment analysis in the laboratory are shown in Fig. 2.

A depiction of the reference area (a), incremental sampling at the reference area (b), bulk sampling using auger (d) and laboratory protocols for preparing soil and sediment samples for radionuclide analysis (c). The photographs were taken by the authors in the reference area (a and b), study sub-watershed (c) and soil and water engineering laboratory, faculty of natural resources, Tarbiat Modares University (d).

Soil sampling in the study area

In the present study, the results from the selected reference area, used in previous research within this watershed35,37, were utilized. Subsequently, in the control sub-watershed, soil sampling for 210Pbex and 137Cs measurements was conducted by selecting a number of sampling points proportional to the land use areas and taking into account the different steepness and slope directions in the watershed. In other words, systematic random sampling was conducted to accurately estimate erosion and sedimentation considering the simultaneous effect of land use/cover and slope direction39. For this purpose, in a 200-m grid size with additional samples for a better representation of different land uses/covers, a total of 31 soil samples and 44 samples were identified over six transects parallel to the main slopes, resulting in 75 soil samples being collected in the control sub-watershed Fig. 3. Soil layer samples were gathered using a ‘Scotter plot’ (40 × 20 × 30 cm3), while the soil depth samples were taken using an ‘Auger’ with a height of 25 cm and a circular section having an 8 cm diameter. Although recent studies have shown that the key assumption of uniform spatial distribution during fallout is invalid, this is negligible for small areas, especially hilly areas with little elevation difference, and cannot be a significant source of error in the uniform spatial distribution during fallout. In addition, the aim of sampling approach was to minimize the effects of uneven radionuclide distribution during fallout and to provide a more comprehensive spatial representation of their distribution within the studied watershed.

Soil and sediment sampling points in the study area for different methods of radionuclides and geochemical fingerprinting. (The maps were generated using ArcMap 10.8.2, https://www.esri.com).

Laboratory analysis

Every single sample was oven-dried inside an aluminum receptacle for 24 h at 105 °C. Then, the samples were weighed and sieved using a 2-mm mesh. After that, they were crushed in an industrial mill and finally screened using a 63-micron mesh40. A representative mass of 293 g was coded and placed in commercial containers. Finally, the samples were analyzed for the activity of 210Pbex and 137Cs using high-purity germanium detectors in the laboratory of the Institute of Applied Physics. The activity of 210Pbex and 137Cs in soil and sediment samples was typically measured using an N-type and P-type coaxial germanium detector and gamma spectrometry37,41.

Calculating inventories

The cumulative inventory of 210Pbex and 137Cs in the soil profile was measured in terms of activity per unit soil mass (Bq kg−1). To estimate the erosion/sedimentation rate, the radionuclide activity was converted from Bq kg−1 to Bq m−2 in order to get inventory value of each sampling point. Calculations were made using Eq. (1)21.

Here, Di indicates depth or thickness of the sampling layer (m), Bi represents bulk density of the soil (gr cm−3), Ci denotes the 137Cs activity (Bq kg−1) and CPI refers to the 137Cs inventory (Bq m−2).

The mean activities of 210Pbex and 137Cs per unit mass of soil (Bq kg−1) for rangeland, irrigated agriculture, rainfed agriculture, and orchard land uses/cover types are presented in Table 1.

Conversion models, which rely on comparing the radionuclide inventory to the reference inventory, are essential for converting radionuclide loss or gain into soil erosion or deposition rates41. The International Atomic Energy Agency designed an Excel-based macro package to convert radionuclide inventory into soil redistribution, using various models. The software was originally designed for 137Cs and was later made available for 210Pbex38. In the current study, the mentioned software was used to convert the inventory of 210Pbex and 137Cs into erosion and sedimentation values. More specifically, for non-agricultural lands (undisturbed soil) due to the absence of displacement signs in the reference soil horizon, the diffusion and migration model was used according to previous studies and field visits. Also, due to the uncertain rainfall regime, inventory of soil displacement due to plowing and, soil tillage time, the mass balance model II was employed for agricultural land37,39. The required information for using the mentioned software based on each of the two selected models is shown in Table 2.

After converting the collected data, the values (both positive and negative) were analyzed to determine the range of erosion and deposition using established equations provided by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The idea is to differentiate areas undergoing erosion, stable conditions, and deposition. The 95% confidence interval with a 10% accepted error between 210Pbex and 137Cs inventories at reference area sampling points was used to determine the boundaries between erosion, stable (the relative balance between erosion and deposition processes over time) and deposition states. In other words, the 95% confidence interval was added to the mean reference inventory to obtain the boundary between stable and deposition states, while the subtraction used as the boundary between stable and erosion states35,39.

The data calculated from these equations indicate erosive, stable, or depositional sampling points. Therefore, these point data were extrapolated to the surface using working unit boundaries to obtain a map of erosion and sediment redistribution in the watershed36. In order to extrapolate point data across the entire sub-watershed, the working unit’s method was employed. In this approach, working unit maps were generated by overlaying land use and slope steepness layers in ArcMap software. Thus, in addition to the boundaries of land use, the slope layer was incorporated as one of the key topographical factors during the data extrapolation process. This integration allowed for more precise modeling of erosion and deposition distribution across the study area. The primary emphasis was placed on land use and slope, as these two factors significantly influence the erosion and deposition patterns within the study area and emphasized in previous studies.

Using ArcMap software, two working unit maps (for 1967 and 2021) as well as a regional slope map were generated. Then, the erosion/sedimentation rate of each sampling point was integrated with the working unit maps (1967–2021) resulting in an erosion/sedimentation distribution map. Following this, sediment budget components, including gross sedimentation, gross or total erosion, net erosion, and the sediment delivery ratio, were calculated using maps obtained from 210Pbex and 137Cs for the periods of 100–120 years and 60–70 years, utilizing the Zonal tool in ArcMap software. For this purpose, the area of each polygon in erosion, stable, or depositional sites was multiplied by the numerical value of erosion/sedimentation. Then, the sum of positive numbers was considered gross sedimentation, the sum of negative numbers was considered gross erosion, and net erosion was calculated by subtracting gross sedimentation from gross erosion. Also, the sediment delivery ratio was computed by splitting net erosion by gross erosion or total erosion27.

A comparison was made between the land use map of approximately 60–70 years prior and that of 2021. The comparison revealed significant changes, particularly the abandonment of rainfed agriculture due to increasing soil loss and reduction of the soil fertility. Then, the residents of Khamsan village were consulted to estimate the approximate year of land use change and the beginning of plowing activities, and finally, this information was used in the conversion models for these points. Subsequently, the minimum, maximum, mean, area, and standard deviation of erosion and sedimentation values were extracted for each land use type by utilizing the erosion and sedimentation map created through the unit approach method for the entire control watershed, employing the Zonal tool in ArcMap software. Finally, using the mean erosion/sedimentation and the area of erosion, stable, and depositional ranges, sediment budget components were calculated for each land use type. It is important to note that, due to the lack of a land use map from around 100–120 years ago, the average contribution of land use types to soil erosion over the past 100–120 years could not be assessed using the 210Pbex method.

Sediment sourcing using geochemical fingerprinting features

Soil sampling and laboratory analysis

For sourcing studies utilizing geochemical fingerprinting features, samples of soil were obtained superficially and from a depth of zero to 2.5 cm below the soil surface6. Initially, a thin surface layer including plant residues and organic material was meticulously removed. Subsequently, a consistent soil sample from the 0–2.5 cm layer was gathered, amounting to roughly 500 g. Soil sampling was performed under appropriate moisture conditions and without rainfall occurring within the five days before sampling. Collection of fine-grained sediment samples from the top 5-cm layer of the river bed was also undertaken. A plastic shovel to preserve the geochemical fingerprinting integrity, including heavy metal concentrations, was used42.

Initially, the grain size distribution of the soil samples was analyzed. The soil and sediment samples were then freeze-dried for 24 h, ground in a porcelain mortar, and sieved through a 63-microns mesh. A representative subsample of approximately 10 g was prepared for each sample and coded in 15 ml Falcon tubes43. Some views illustrate the procedures for soil and sediment sampling, as well as the laboratory methods employed for sample preparation Fig. 4.

Views of soil and sediment sampling, alongside laboratory preparation methods for geochemical fingerprinting measurement (The face belongs to the first author). The photographs were taken by the authors in the study sub-watershed (a) and soil and water engineering laboratory, faculty of natural resources, Tarbiat Modares University (b, c and d).

The soil and sediment samples underwent acid digestion to facilitate the measurement of geochemical fingerprinting elements, and 3 g of the fraction smaller than 63 microns were placed in a water bath for two hours in aqua regia solution, which is a blend of concentrated hydrochloric acid and nitric acid mixed in a 3:1 ratio. Once cooled, the samples were filtered through filter paper with a pore size of 0.2 microns. Finally, using the ICP-OES GBC Integra instrument and the Merck standard sample, an analytical curve was plotted, and the geochemical fingerprinting characteristics (mg kg−1) were obtained44. To determine the proportional contribution of land uses/land covers, the FingerPro program of the R software, which is a specialized open-source text mining package, was used. FingerPro is able to assess the contribution of sediment sources by selecting a set of optimal tracers using a multivariate model algorithm. The user-friendly features of this package include assisting in decision-making regarding the best tracers, visualizing results using advanced R graphics, determining the contribution of sediment sources without requiring high experience and expertise in software usage45, and visualizing the results. The optimal tracers were selected through the application of the range test (RT) and the Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test.

In this study, an initial selection of 56 elements was made to serve as tracers. Afterward, a statistically derived optimal set of tracers, capable of differentiating sediment sources, was determine46,47. The tracer selection process, along with the application of an integrated model to estimate the proportional contributions of different land uses to sediment production, was carried out using coding tools provided in the FingerPro package within the R programming environment45. The consistency of the tracers was evaluated through the range test provided within the FingerPro package in R software. Subsequently, tracers displaying statistically significant variations among sources were identified using the Kruskal–Wallis test45.

Investigating the erosion history by comparing sediment sourcing and sediment budget results with field measurements

In the control sub-watershed, a Santarita flume with a capacity of five m3 s−1 and a limnograph for collecting flow rates data with intervals of 5 min were installed to measure sediment concentration daily (on days when runoff events occurred) and in some cases with two repetitions per day. The measured sediment dataset from 2009 to 2023 were obtained from the General Directorate of Natural Resources of Kurdistan Province.

Average erosion/sedimentation rates over the past 100–120 and 60–70 years were determined using 210Pbex and 137Cs methods, respectively, and were used together with sediment fingerprinting using geochemical tracers and sediment measurement data for about 15 years to investigate the erosion history of the study area. These values served to detect the long-term and medium-term changes in erosion/sediment transport within the sub-watershed, including the direction of change (increase, decrease, constant, or combined) and the slope variation. Also, the mean contribution of various land uses to sediment yield over the last 60–70 years, as determined through the 137Cs method, was compared with the average land use contribution obtained from geochemical fingerprinting feature for the present time and was analyzed for the changes. Although the quantitative comparison of average erosion intensity over the examined periods, even without the need for statistical tests, is highly valuable, the comparison of erosion raster maps and sediment redistribution based on dominant slope directions (north, east, and west) and different land uses was also performed using the correlation coefficient48.

Results and discussion

Sediment budget results using 210Pbex and 137Cs

The sediment budget results, derived from the average distribution map of erosion/sedimentation values (see Fig. 5), as well as the calculation of sediment budget components using the 210Pbex and 137Cs methods, are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Comparison of erosion/sedimentation budget results for the past 100–120 and 60–70 years in Tables 3 and 4shows that the average gross erosion, average gross sedimentation, and average net erosion in the recent 60(70)-year period have increased by about two-fold, three-fold, and two-fold, respectively, compared to the recent 100–120-year period. Additionally, the sediment delivery ratio was estimated to be 0.976 in the 100–120-year period and 0.962 in the 60(70)-year period. In other words, the results related to all components of the sediment budget indicate an increase in erosion, sediment redistribution at the watershed level, and ultimately in sediment transport and delivery to the studied watershed outlet. Evidence suggests that the use of rain-fed agricultural land, plowing along the slope direction on steeper inclines, is frequently highlighted by researchers as a key factor contributing to the observed increase in average erosion rates in recent decades (e.g25,34,37,49,49,51.,).

An analysis comparing the 1967 and 2021 land use maps showed that the primary change was a reduction in dryland agricultural areas, resulting from the abandonment of these lands. Table 5 summarizes the estimated average contributions of different land uses to soil erosion rate over the last 60–70 years, based on the results of the 137Cs analysis.

As seen in Table 5, over 85% of erosion occurred within the Khamsan representative paired watershed’s control sub-watershed, which is characterized by rainfed agriculture land use. It should be noted that in a considerable portion of rangeland identified as a stable condition, soil erosion has also occurred, but the intensity of erosion is low and, based on the 95% confidence interval criterion, these regions were classified as stable and excluded from the calculations of erosion or sedimentation contributions. Additionally, the portion subjected to irrigated agriculture, which includes a modest, gentle-sloped region close to the sub-watershed outlet, where the erosion intensity is low, was considered a sustainable area in the final erosion/sedimentation map and, of course, had small contribution to sub-watershed erosion.

The erosion/sedimentation results using the 210Pbex and 137Cs methods along six transects (see Fig. 2) are shown in Fig. 6. The main factor describing the changes in erosion/sedimentation specially in the results of 137Cs method (yellow box labels) is rainfed agriculture, while the land use change to rainfed agriculture mainly done around 60–70 years ago and was not enough to affect the results of 210Pbex method (100–120 years) significantly. As a result, the erosion/sedimentation using 210Pbex method (blue box labels) shows lower erosion rates or even sedimentation in the middle of the hillslopes.

Sediment sourcing results using geochemical fingerprinting

The range test excluded 11 elements from the dataset, leaving the remaining elements as effective tracers at this stage. The Kruskal–Wallis test then identified 42 additional elements to be excluded. Ultimately, three elements (Hf, Ni, and Mo) were identified as the most suitable tracers. Table 6 summarizes the results of both tests, outlining the selection process. Additionally, Fig. 7 presents box plots showing the concentration variations (mg kg⁻1) of the final tracers across different sediment sources (land uses).

The discriminant function analysis using the optimal set of tracers is shown in Fig. 8. It presents the linear discriminant analysis in a three-dimensional format, highlighting whether the excluded variables influence the ability to differentiate between sources.

As can be seen in the DFA plot, the points related to irrigated agriculture and rainfed agriculture are well separated, but because the number of points related to irrigated agriculture was less than 4 points, the ellipse of the diagram separation was not drawn. In case of orchard, there were only two sampling points; one located near the irrigated agriculture points and the other located near the rainfed agriculture points. However, the area of the orchard was very small and is only a patch near the outlet of the sub-watershed, and its separation or integration cannot have a significant effect on the results of the contribution of land uses to sediment yield.

The results of the contribution of sedimentary sources, including irrigated agriculture, orchards, rangeland, and rainfed agriculture, the sediment yield analysis, performed with the FingerPro package in R software, is summarized in Table 7. The results show that rainfed lands have allocated the highest relative contribution of 72.26% in sediment yield. Furthermore, the contribution of other sedimentary sources, including irrigated agriculture (15.06%), rangeland (7.96%), and orchards (4.72%) were obtained. Tillage operations (plowing) on slopes caused rainfed agriculture to have the highest contribution to sediment yield. This result has been emphasized in many previous studies, especially in the Khamsan Watershed. On the other hand, analysis conducted with the FingerPro tool in R revealed a goodness of fit index of 0.78 ± 0.1 for sediment source identification, which is higher than 0.60, according to recent studies (e.g45,46,52.,), and it is acceptable.

The results of sediment measurement and analyzing the erosional history

The results of sediment yield measurements in the studied sub-watershed for the years 2009, 2010, 2011, 2018, and 2023 are presented in Table 8. The mean value of sediment yield observed during the monitoring period resulted ca. 1.322 t ha−1 y−1, which is about 1/2 and 1/4 when compared to the mean value of net erosion provided by 210Pbex and 137Cs for the period of 100–120 and 60–70 years, respectively.

Analysis of erosion and sediment yield history

The overall results and the tentative reconstruction of the erosion history, using three methods consisting of radionuclide cores, geochemical fingerprinting, and sediment observations, suggest that erosion intensity and sediment redistribution in the control sub-watershed of Khamsan representative-paired watershed has increased over the past 100–120 years. Furthermore, comparing the sediment budget components in the last 100–120 and 60–70 years shows that the average gross erosion and gross deposition have increased two-fold and three-fold, respectively. This difference in the ratio of changes of the average gross erosion and sediment deposition has resulted in a two-fold increase in net erosion during this period.

A very important point in confirming the increasing trend of erosion in the last 100–120 years is the contribution of land use to sediment yield, which was estimated using the 137Cs method for the average of the last 60–70 years, showing that more than 85% of erosion in the last 60–70 years has occurred in rainfed agricultural land use. Soil tillage (plowing) on slopes in the fields caused the highest share of sediment production to belong to rainfed agricultural land use, and this result has been emphasized in many earlier research (e.g25,46.,), especially in the Khamsan watershed37.

The average sediment yield measured over five years in the last 15 years was 1.32 t ha−1 y−1, which represents about two-fold and four-fold decrease compared to net erosion (sediment yield) in the sub-watershed over the 100–120 and 60(70)-year periods, respectively. These results are apparently in contrast with the overall estimates produced by the 210Pbex and 137Cs techniques but there are several possible explanations for this divergence. During the fallout period (i.e., 1954–1978), the redistribution of radionuclides led to their loss through runoff events. Studies have shown that when 137Cs was introduced via rainfall, its concentration in sediment was significantly higher than in the materials at the soil’s surface. This suggests that suspended sediments can absorb radionuclides from runoff water. However, most theoretical conversion models fail to account for this crucial pathway of radionuclide loss during fallout, leading to a significant overestimation of soil erosion rates53. This may be another reason why our net soil loss over the past 60–70 years is almost double the measured rate recorded over the past 15 years. Another reason is related to the short and discontinuous monitoring period (only 5 years) that makes the calculation of the mean value quite uncertain and certainly not representative of a long-term time window. In addition, decreasing sediment yield in recent years can be attributed to a corresponding reduction of precipitation and this may add problems of non-stationarity in the process. Additionally, physical barriers such as plowing along the main channels and even crop planting inside the channels have effectively restricted runoff and sediment movement at the watershed outlet. This may have caused a decrease in surface runoff and sediment yield due to the new generated areas of sedimentation upstream of the outlet of the sub-watershed. Therefore, management interventions clearly explain the reduced sediment transport rate in recent years, which aligns well with the collected data and conducted analyses. Figure 9 shows images of land tillage in rainfed agriculture areas near and even inside the main stream channel of the sub-watershed.

Furthermore, the results of sediment sourcing in 2021 also indicate that rainfed agriculture lands contributed more than 72% to the relative maximum sediment yield. However, the contribution of this land use in 2021 is less than its average contribution over the past 60–70 years (exceeding 85%). This reduction in rainfed agriculture’s contribution to sediment yield is attributed to the same factors that have led to a decline in erosion intensity in recent years, as previously discussed.

Limitations

Challenges and limitations are common in implementing source fingerprinting methods54. Despite analyzing a total of 106 soil samples, examined from four distinct land use types within a 102-hectare area, uncertainties persist regarding the representativeness of the sampling distribution within each land use. The process of using aqua regia for extracting tracers from source substances and sediment specimens yielded partial rather than comprehensive concentration values. The selection of tracers relied more heavily on the outcomes of previous international studies than on detailed physico-chemical analysis, resulting in a statistically-driven approach for distinguishing and attributing sediment sources. Despite these limitations, tests using virtual sediment mixtures indicated that the source attribution accuracy was within acceptable ranges Table 9.

Future prospects

If the current trend of land-use changes and plowing the beds of small streams continues in the study area, significant changes in the drainage network and sediment transport would be very likely. Specifically, the removal of first- and second-order channels could lead to disruption in the drainage network and loss of sediment connectivity. This, in addition to reducing hydrological connectivity, may halt sediment transport to the watershed outlet. Although reduced sediment transport might appear beneficial at first glance, it would, in fact, be detrimental to the region in terms of sustainable watershed management. The loss of sediment connectivity and disruption in the drainage network could impair the ability of the watershed to regulate floods and maintain ecosystem stability. To address these challenges, protective measures and management strategies must be implemented to preserve the drainage network, control drastic land-use changes, and enhance the watershed’s sustainability. Therefore, future planning must prioritize these actions to maintain the stability of the drainage network, limit severe land-use changes, and promote the overall sustainability of the watershed ecosystem services.

Conclusion

-

The present study integrates the results of 210Pbex and 137Cs techniques along with geochemical fingerprinting and observational data to minimize the uncertainties associated with the estimates of each individual method.

-

The analysis of erosion history through the measurement of average soil erosion intensity and sediment yield in the last 100–120, 60–70, and 15 years is feasible using a combination of radionuclide, geochemical fingerprinting, and sediment observational methods.

-

Using data from the climatology station within the sub-watershed, it was determined that the highest volume of precipitation occurs in the late winter and early spring. This period coincides with the lack of vegetative cover in dryland farming areas, which is another contributing factor to the increased sediment production in the study area.

-

The average gross erosion, gross sedimentation, and net erosion in the last 60–70 years have increased by approximately two-fold, three-fold, and two-fold, respectively, compared to the last 100–120 years period.

-

The average sediment yield in the last 15 years is 1.32 t ha−1 y−1, which represents about two-fold and four-fold decrease compared to net erosion (sediment yield) in the sub-watershed over the 100–120 and 60–70-year periods, respectively.

-

In 2021, in relation to the average of the last 60–70-year period, the contribution of rangeland and rainfed agriculture has decreased by approximately 1.1-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively, while orchards and irrigated agriculture has increased by approximately 1.25-fold and 8.4-fold, respectively.

-

The results show that erosion has occurred, and sediment is available for transport, but reduced precipitation and plowing, especially within the waterway, have restricted surface runoff and sediment delivery to the watershed outlet.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Keesstra, S. D. et al. The significance of soils and soil science towards realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Soil. Soil 2, 111–128. https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2-111-2016 (2016).

Vercruysse, K., Grabowski, R. C. & Rickson, R. J. Suspended sediment transport dynamics in rivers: Multi-scale drivers of temporal variation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 166, 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.12.016 (2017).

Jones, C. S. & Schilling, K. E. Agricultural intensification to conservation: Sediment transport in the Raccoon River Iowa 1916–2009. J. Environ. Qual. 40(6), 1911–1923. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2010.0507 (2011).

Lamba, J., Karthikeyan, K. G. & Thompson, A. M. Apportionment of suspended sediment sources in an agricultural watershed using sediment fingerprinting. Geoderma 239–240, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.09.024 (2015).

Koiter, A. J., Owens, P. N., Petticrew, E. L. & Lobb, D. A. The behavioural characteristics of sediment properties and their implications for sediment fingerprinting as an approach for identifying sediment sources in river basins. Earth-Sci. Rev. 125, 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.05.009 (2013).

Hancock, G. J. & Revill, A. T. Erosion source discrimination in a rural Australian catchment using compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA). Hydrol. Process. 27(6), 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9466 (2013).

Belmont, P. et al. Toward generalizable sediment fingerprinting with tracers that are conservative and nonconservative over sediment routing timescales. J. Soils Sediments 14(8), 1479–1492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-014-0913-5 (2014).

Vale, S. S., Fuller, I. C., Procter, J. N., Basher, L. R. & Smith, I. E. Characterization and quantification of suspended sediment sources to the Manawatu River, New Zealand. Sci. Total Environ. 543, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.003 (2016).

Douglas, G., Caitcheon, G. & Palmer, M. Sediment source identification and residence times in the Maroochy River estuary, southeast Queensland, Australia. Environ. Geol. 57, 629–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1336-7 (2009).

D’Haen, K. et al. Unravelling changing sediment sources in a Mediterranean mountain catchment: A Bayesian fingerprinting approach. Hydrol. Process. 27, 896–910. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9399 (2013).

Malhotra, K., Lamba, J. & Shepherd, S. Sources of stream bed sediment in an urbanized watershed. CATENA 184, 104228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104228 (2020).

Amasi, A. I. et al. Reconstructing the changes in sedimentation and source provenance in an East African hydropower reservoirs: A case study of Nyumba ya Mungu in Tanzania. Earth 2(3), 485–514. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth2030029 (2021).

Nosrati, K., Moradian, H., Dolatkordestani, M., Mol, L. & Collins, A. L. The efficiency of elemental geochemistry and weathering indices as tracers in aeolian sediment provenance fingerprinting. CATENA 210, 105932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105932 (2022).

Mohammadi, M., McMackin, C. & Egli, M. Source identification of morainic materials in soils of the Three Lakes region (Switzerland) using the fingerprinting technique. CATENA 234, 107619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107619 (2024).

Nam, S. et al. Differentiating potential suspended sediment sources using radionuclide tracers and soil organic matter analysis in a headwater catchment in Chuncheon, South Korea. Water 16(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16010182 (2024).

Menzel, R. G. Transport of 90Sr in runoff. Science 131, 499–500 (1960).

Ritchie, J. C. & McHenry, J. R. Determination of fallout 137Cs and naturally occurring gamma-ray emitters in sediments. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 24(10), 575–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-708X(73)90125-7 (1973).

Golosov, V., Belyaev, V., Kuznetsova, Y., Markelov, M. & Shamshurina, E. Response of a small arable catchment sediment budget to introduction of soil conservation measures. In Sediment Dynamics in Changing Environments, Vol. 325, 106-113 (IAHS Publications, 2008).

Mabit, L., Benmansour, M. & Walling, D. E. Comparative advantages and limitations of the fallout radionuclides 137Cs, 210Pbex and 7Be for assessing soil erosion and sedimentation. J. Environ. Radioact. 99(12), 1799–1807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2008.08.009 (2008).

Walling, D. E. & Quine, T. A. Use of 137Cs measurements to investigate soil erosion on arable fields in the UK: Potential applications and limitations. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 42(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1991.tb00099.x (1991).

Walling, D. E. Using Environmental Radionuclides as Tracers in Sediment Budget Investigations Vol. 283, 57–78 (IAHS Press, 2003).

Porto, P. & Callegari, G. Comparing long-term observations of sediment yield with estimates of soil erosion rate based on recent 137Cs measurements: Results from an experimental catchment in Southern Italy. Hydrol. Process. 36(9), e14663. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14663 (2022).

Porto, P., Walling, D. E., Callegari, G. & Catona, F. Using fallout lead-210 measurements to estimate soil erosion in three small catchments in Southern Italy. Water Air Soil Pollut. Focus 6, 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11267-006-9050-5 (2006).

Porto, P., Walling, D. E., Callegari, G. & Capra, A. Using caesium-137 and unsupported lead-210 measurements to explore the relationship between sediment mobilisation, sediment delivery and sediment yield for a Calabrian catchment. Mar. Freshw. Res. 60(7), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF08050 (2009).

Gharibreza, M. et al. Assessment of deforestation impact on soil erosion in loess formation using 137Cs method (case study: Golestan Province, Iran). Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 8(4), 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2020.07.006 (2020).

Mouri, G. Reproduction of sediment deposition and prediction of 137Cs concentration in the major urban rivers of Tokyo. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65700-y (2020).

Sedighi, F., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Golosov, V., Zare, M. R. & Spalevic, V. Influence of land use on changes of sediment budget components: western Iran case study. Turk. J. Agric. For. 46(6), 838–851. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-011X.3046 (2022).

Hancock, G. R., Gibson, A., Kirk, E., Conway, I. & Parrod, A. Soil erosion and carbon export: A case study in a steep slope grazing landscape. Geoderma Reg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2023.e00751 (2024).

Su, Z. A. et al. A preliminary study of the impacts of shelter forest on soil erosion in cultivated land: Evidence from integrated 210Pbex and 137Cs measurements. Soil Till. Res. 206, 104843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2020.104843 (2021).

Cabrera, M. et al. Using 210Pbex and 137Cs to assess soil redistribution at different temporal scales along with lithogenic radionuclides to evaluate contrasted watersheds in the Uruguayan Pampa grassland. Geoderma 435, 116502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116502 (2023).

Dowell, S. M. et al. Suitability of 210Pbex, 137Cs and 239+240Pu as soil erosion tracers in western Kenya. J. Environ. Radioact. 271, 107327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2023.107327 (2024).

Khaledi Darvishan, A., Jalal, F., Gholami, L. & Khorsand, M. Spatio-temporal variation of soil erosion in Khamsan representative watershed using RUSLE. Watershed Eng. Manag. 13(3), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.22092/ijwmse.2021.128809.1752 (2021) (in Persian).

Khodamoradi, H., Khaledi Darvishan, A. & Sadeghi, S. H. R. Performance evaluation of watershed management measures in reducing soil erosion in treated and control sub-watersheds of Khamsan representative watershed using 137Cs method. J. Watershed Manag. Res. 36(2), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.22092/wmrj.2022.358701.1474.(inPersian) (2023).

Azami, N., Khaledi Darvishan, A. & Gholami, L. Evaluation of sediment delivery ratio estimation methods in Khamsan representative-paired watershed. Watershed Eng. Manag. 16(3), 394–414. https://doi.org/10.22092/ijwmse.2024.358084.1965.(inPersian) (2024).

Zarei, R., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Porto, P. & Zare, M. R. Using radiotracers and topographic metrics for sediment budgeting at pixel and hillslope scales: A case study from western Iran. Ecol. Indic. 167, 112711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112711 (2024).

Ghaderi Dehkordi, N., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Zare, M. R. & Porto, P. Temporal changes in the average contribution of land uses in sediment yield using the 137Cs method and geochemical tracers. Water 17(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010073 (2025).

Sedighi, F., Khaledi Darvishan, A. & Zare, M. R. Effect of watershed geomorphological characteristics on sediment redistribution. Geomorphology 375, 107559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107559 (2021).

Dercon, G. et al. Fallout radionuclide-based techniques for assessing the impact of soil conservation measures on erosion control and soil quality: An overview of the main lessons learnt under an FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Project. J. Environ. Radioact. 107, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2012.01.008 (2012).

Walling, D. E., He, Q. & Zhang, Y. Conversion models and related software. In Guidelines for Using Fallout Radionuclides to Assess Erosion and Effectiveness of Soil Conservation Strategies. IAEA-TECDOC-1741, 125–148 (IAEA Publications, 2014).

Chiu, Y. J., Chang, K. T., Chen, Y. C., Chao, J. H. & Lee, H. Y. Estimation of soil erosion rates in a subtropical mountain watershed using 137Cs radionuclide. Nat. Hazards 59(1), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9749-0 (2011).

Zapata, F. Handbook for the Assessment of Soil Erosion and Sedimentation Using Environmental Radionuclides Vol. 219, 219 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48054-9.

Smith, H. G. & Blake, W. H. Sediment fingerprinting in agricultural catchments: A critical re-examination of source discrimination and data corrections. Geomorphology 204, 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2013.08.003 (2014).

Gholami, H., Middleton, N., Nazari Samani, A. A. & Wasson, R. Determining contribution of sand dune potential sources using radionuclides, tracers and major elements in central Iran. Arab. J. Geosci. 10(7), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-017-2917-0 (2017).

Nosrati, K., Ahmadi, H. & Forozan, A. Investigating seasonal change effects on suspended sediment yield using geochemical tracers. Iran. J. Geol. 12(46), 60–73 (2018) (in Persian).

Lizaga, I., Latorre, B., Gaspar, L. & Navas, A. FingerPro: An R package for tracking the provenance of sediment. Water Resour. Manag. 34(12), 3879–3894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-020-02650-0 (2020).

Mohammadi, M., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Bahramifar, N. & Alavi, S. J. Spatio-temporal suspended sediment fingerprinting under different land management practices. Int. J. Sediment Res. 38(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2023.02.003 (2023).

Haji, K., Khaledi Darvishan, A. & Mostafazadeh, R. Soil erosion and sediment sourcing in the Hyrcanian forests, Northern Iran: An integration approach of the G2loss model and sediment fingerprinting technique. Mod. Earth Sys. Environ. 10(2), 1897–1914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-023-01879-z (2024).

Masroor, M. et al. Analysing the relationship between drought and soil erosion using vegetation health index and RUSLE models in Godavari Middle Sub-basin. India. Geosci. Front. 13(2), 101312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2021.101312 (2021).

Walling, D. E. Linking land use, erosion and sediment yields in river basins. In Man and River Systems, 223–240 (Springer, 1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2163-9_24.

Mohammadi, M., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Dinelli, E., Bahramifar, N. & Alavi, S. J. How does land use configuration influence on sediment heavy metal pollution Comparison between riparian zone and sub-watersheds. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 36, 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-021-02082-1 (2022).

Haji, K., Khaledi Darvishan, A. & Mostafazadeh, R. Assessment of the G2 model estimations and comparing it with erosion plots and observed sediment data in the Southern Caspian Sea river basins. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 57, 102179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2025.102179 (2025).

Karimi, N., Gholami, L., Kavian, A. & Khaledi Darvishan, A. Determination of specific contribution of suspended sediment sources in Vaz watershed using geochemical characteristics. J. Ecohydrol. 9(4), 705–718. https://doi.org/10.22059/IJE.2023.344381.1649 (2022) (in Persian).

Dalgleish, H. Y. & Foster, I. D. L. 137Cs losses from a loamy surface water gleyed soil (Inceptisol); A laboratory simulation experiment. Catena 26(3–4), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/0341-8162(96)00002-1 (1996).

Collin, A. L. et al. Sediment source fingerprinting for catchment management: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 194, 86–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.075 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The current research was undertaken as the doctoral dissertation of Negin Ghaderi Dehkordi, with the financial support of Tarbiat Modares University, Iran. Authors would like to thank Mr. Hamid Khodamoradi, Dr. Reza Zarei, Dr.. Nabiyeh Karimi and Dr. Fatemeh Sedighi for their helps in the field sampling and laboratory measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.D. and P.P.; methodology, N.G.D., A.K.D., M.R.Z. and P.P.; software, N.G.D., A.K.D., M.R.Z. and P.P.; validation, N.G.D., A.K.D. and P.P.; formal analysis, N.G.D., A.K.D., M.R.Z. and P.P.; investigation, N.G.D., A.K.D. and P.P.; resources, N.G.D., A.K.D. and P.P.; data curation, N.G.D. and A.K.D.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G.D.; writing—review and editing, A.K.D. and P.P.; visualization, N.G.D. and A.K.D.; supervision, A.K.D., M.R.Z. and P.P.; project administration, A.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghaderi Dehkordi, N., Khaledi Darvishan, A., Porto, P. et al. Erosional history by combining 210Pbex and 137Cs methods with sediment fingerprinting and measurements. Sci Rep 15, 18165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02512-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02512-y