Abstract

For the next-generation high temperature microreactors, yttrium dihydride (YH2) is an attractive solid state neutron moderator. Despite a number of recent investigations, the mechanism of hydrogen transport remains poorly understood. Experimental evaluations of diffusivity are inconclusive with large variations in diffusivities and activation energies. In this work, we perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations on YH2 for temperatures spanning 300 K to 1200 K. Our main finding is that YH2 shows a superionic-like behavior with hydrogen atoms hopping from one native site to another above a characteristic temperature of 800 K. This correlated motion results in quasi-one-dimensional string-like displacements that enable the hydrogen atoms to diffuse rapidly. We confirm that the octahedral sites are mostly unoccupied, although channeling through them is the most favored pathway between lattice hops above 800 K. At the highest temperature of 1200 K, the string relaxation time is merely of the order of a few picoseconds, which indicates a liquid-like diffusive behavior. Based on the formation of spontaneous thermal vacancies, an order-disorder crossover temperature Tα ~ 800 K is established for YH2 with an activation energy of 0.83 eV for hydrogen diffusion in the superionic-like state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The persistent reliance on fossil fuels has resulted in arduous environmental challenges, notably air pollution and climate change driven by carbon emissions. Nuclear power continues to hold the pole position for generating carbon-free electricity all year round with the highest capacity factor among all the clean energy sources. In the United States, nuclear energy contributes to roughly one fifth of the total electric power generated with an estimated 24 Gt of avoided CO2 emissions over the past fifty years1. Most of the nuclear power in the United States comes from large light water reactors with a power rating of 1000 MWe or more built more than fifty years ago; construction of new plants has come to a standstill due to large upfront investments and protracted construction schedules. In recent years, there has been a shift to designing and building small modular reactors (SMRs) that are scalable, affordable and thermodynamically more efficient. A smaller subject of SMRs labeled as microreactors with a power rating of 20MWe2 are also being considered for deployment in areas that do not have access to the electric grid. These truck-transportable reactors require a compact reactor design that can be achieved by solid-state neutron moderators such as metal hydrides3. Yttrium dihydride (YH2) is a particularly suitable candidate due to its ability to retain hydrogen at temperatures exceeding 1000 °C and its remarkable thermal stability at elevated temperatures4,5. However, the mobility of hydrogen in YH2 introduces special challenges such as redistribution or loss at high temperatures that can adversely impact the neutronic behavior and potentially reduce the operational lifespan of the microreactors. It’s critical, therefore, to establish the hydrogen migration and retention mechanisms in YH2 to ensure safe reactor operational limits under normal and off-normal conditions6.

Hydrogen diffusivity in metal hydrides has been investigated using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy7 and neutron spectroscopy (NS)8,9 through inelastic neutron scattering; other techniques such as mechanical spectroscopy10 have also been reported. Both NMR and NS techniques are well-suited for probing hydrogen motion due to the gyromagnetic ratio of the proton for the former that is the largest among all known stable nuclei11, and the large incoherent neutron scattering cross section for the latter (~ 80 b), which is over ten times more than other common nuclei12. All the spectroscopic methods extract relaxation rates or times that are associated with hydrogen diffusion under various approximations. Most NMR methods rely on evaluating the spin-lattice (Γ1) and spin-spin (Γ2) relaxation rates, which are strongly sensitive to atomic motion such as translation and rotation; a third relaxation rate (Γ1ρ), which is associated with the relaxation of transverse component of magnetization, is also used to assess the atomic jump frequency11. The spin echo NMR technique, often employed with a pulsed field gradient (PFG-NMR)13, can estimate diffusivity directly without any reference to lattice paths or correlations while spin-lattice relaxation measurements need additional information usually supplied by jump diffusivity models11. In inelastic neutron scattering (INS) or quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS), which is a limiting case of INS, the broadening of the quasi-elastic peak provides the jump distances and diffusivities of mobile species in translational diffusion9,14 typically using Gaussian diffusion models.

While hydrogen is known to have high mobilities in hydrides, the mechanism of transport is not well-elucidated. In recent years, group II metal hydrides such as BaH2 have been shown to be superionic conductors resulting from a (Ni2In) hexagonal structure at high temperatures. The current evidence for superionic-like transport in group III or IV dihydrides is suggestive but not conclusive15,16,17,18. An anomalous increase in the nuclear spin relaxation time at high temperatures has been interpreted as a transition to a superionic-like state with correlated motion among hydrogen atoms17 although objections have been raised for using only the spin-lattice (Γ1) relaxation8,19. Alternate explanations involving the presence of hydrogen molecules or atom pairing at high temperatures20, deemed unlikely by Cotts21, or the presence of unidentified impurities have also been offered22.

Diffusivity is strongly sensitive to the stoichiometry; as a general trend, the diffusivity increases with increasing hydrogen concentration in YHx, which is opposite to that observed in ZrHx as shown in several investigations8,13. Using neutron spectroscopy, Stuhr and coworkers8 evaluated a diffusivity of O(10− 9) m2/s for hydrogen atoms at a temperature ~ 1250 K with YH1.97. This work is notable because of liquid-like diffusivity, albeit at high temperatures, obtained with a stoichiometry that is nearly two. More interesting is a crossover behavior ~ 870 K where the diffusivity starts increasing at a faster rate with a small but conspicuous change in activation energies. Curiously, this transition which went undetected previously, appears to conform with a peak in the specific heat at a slightly lower temperature of ~ 800 K as well as a change in behavior for thermal expansivity observed in more recent measurements with YH1.9223. A peak in the specific heat, or other thermodynamic response functions such as compressibility and thermal expansivity, is a signature of a second-order phase transition that is associated with Type II superionic conductors24. Commonly known as the λ transition, a sharp rise and drop in the specific heat is observed at a characteristic temperature (Tλ) and is usually accompanied by a change in the ionic conductivity25,26. Stoichiometric-dependent peaks in the specific heat reported by Trofimov et al.27 appear to suggest that this transition temperature decreases with increasing hydrogen content in YHx. These new observations give a certain plausibility to the original speculation by Barnes and coworkers16,17 that the long correlation time for proton dipolar interactions in NMR measurements may signify an onset of strongly correlated motion among the hydrogen atoms and the diffusive motion may be analogous to that in Type II fast ion conductors.

Verifying the existence of superionic-like diffusion in YHx is challenging due to the inherent limitations in interpreting data and various experimental uncertainties. Electronic structure simulation methods such as those based on density functional theory (DFT)28 along with energy landscape sampling methods29,30 are useful for identifying potential pathways for diffusion. However, these methods primarily provide kinetic rates based on the potential energy barriers between presumed lattice/defect sites and do not typically incorporate thermal fluctuations that play a key role in correlated diffusive transport. In this work, we use ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations based on DFT to probe the complex diffusive dynamics of hydrogen atoms in YH2 at finite temperatures.

Building upon previous molecular dynamics (MD) analysis on superionic fluorites25,26,31, we show that the hydrogen atoms start diffusing in a string-like manner beyond a characteristic temperature (Tα) of ~ 800 K. Correlated motion of hydrogen atoms across the tetrahedral (tet) sites by thermal activation is shown as the primary mechanism of diffusion at high temperatures. Unlike speculated in the early investigations8,13,16, the occupancy of octahedral (oct) sites is minimal, which is consistent with the assessment made in a more recent experimental-computational study28. The oct sites, however, are dynamically favored as plausible transition state points connecting two neighboring tet sites at high temperatures. Based on the formation of spontaneous thermal vacancies and string relaxation times, an order-disorder transition temperature Tα ~ 800 K, similar to that in fluorite superionic conductors25,26,31, is established for YH2 with a possible superionic-like transition occurring at Tλ ~ 1000 K.

Results and analysis

YH2 has a fluorite structure and belongs to the cubic Fm̅3m space group. The Y atoms form a fcc lattice with the H atoms occupying the tet sites as shown in Fig. 1(a). In an alternative representation, the H atoms are positioned in a simple cubic lattice with the Y atoms occupying alternate cube centers that are also the oct locations of the fcc lattice – see Fig. 1(b); this leaves two empty oct sites that can potentially accommodate the H atoms.

In this work, we use AIMD simulations as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)32,33 of YH2 for temperatures between 300 and 1200 K focusing on the mobility of hydrogen atoms. The details are given in the Methods section.

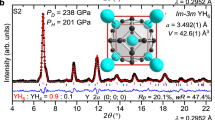

Validation/verification of the AIMD simulations

To validate our simulations, the structural and dynamical features are compared against available experimental data; verification is provided by comparison with past simulation data. Fig. 2(a) delineates the variation of lattice parameter with temperature. At 300 K, a lattice parameter of 5.231 Å with the PBE functional is only 0.6% higher than the experimental value of 5.201 Å34 (at 295 K); it also matches well with data from Chapman et al.35 with the same functional. With the AM05 functional, our AIMD simulations underpredicts the lattice parameter at 295 K slightly, but are nearly identical to the simulation data from Chapman et al.35 using the same functional. Given the greater computational expense with the AM05 functional, and the relatively good prediction with the PBE functional for the structural properties (see supplementary information), the rest of the results presented here are with the PBE functional.

Next, we compare the dynamic structure factor integrated over wavevectors (q) ranging from 2 to 13 Å−1 from neutron scattering experiments35 against simulation data in Fig. 2(b). The AIMD data, although noisy at shorter wavevectors due to limited number of atoms in the simulation supercell (324) and lack of statistical averaging, is able to predict the first peak location and relative amplitude with good fidelity. While the second peak position is well-captured, there is a greater decay in the amplitude suggesting more thermal relaxation at larger frequencies with the AIMD simulations.

Validation/verification of the AIMD simulations, (a) lattice parameter from the current simulations for different temperatures compared to experimental data34 (295 K) and previous AIMD simulations35, (b) comparison of dynamic structure factor for YH2 integrated over wavevectors (q) ranging from 2 to 13 Å−1 from inelastic neutron scattering (INS) experiments35 at 800 K against current AIMD prediction.

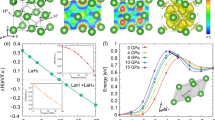

Linear thermal expansion and enthalpy

The temperature dependence of linear thermal expansion (LTE) and enthalpy difference (relative to 300 K) are shown in Fig. 3. The LTE is computed based on the change in lattice parameter normalized to that at 300 K. The current simulations are performed at 0 pressure; so, the enthalpy is identically equal to the internal energy. Interestingly, a change in slope at 800 K can be seen in both LTE and the enthalpy variation, which is indicative of two different responses – one at low temperatures (≤ 800 K) and another at higher temperatures (> 800 K). To explore this transition further, the radial distribution function \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\) which depicts the local arrangement of H atoms at various temperatures is delineated in Fig. 4(a). At 400 K, \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\) exhibits well-defined peaks indicating an ordered lattice structure. As the temperature increases, the magnitude of the peaks diminishes significantly and the sharper peaks beyond the second neighbor merge to form fewer and more diffusive peaks reflecting a transition towards a more disordered state.

To identify a more specific temperature for a plausible transition, we compute the Wendt-Abraham (WA) parameter, which is defined as the ratio of the magnitude of the first minimum to the maximum of the first peak in \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\): \({R^{WA}}={g_{min}}/{g_{max}}\)36. Previously, this parameter has been used as a criterion for identifying a transition to an amorphous phase36. More recently, Celtek et al.37 proposed that the squared WA parameter, \({R^{MWA}}={\left( {{g_{min}}/{g_{max}}} \right)^2}\), is a more accurate predictor of the transition temperatures37. From Fig. 4(b), it can be observed that \({R^{MWA}}\) has a smooth variation across the temperatures. However, a low temperature and a high temperature regime is clearly discernible with a crossover at ~ 800 K. Thus, the structural (LTE, radial distribution function) and thermodynamic (enthalpy) metrics strongly suggest an order-disorder transitioning in YH2 at ~ 800 K. In the next sections, we will investigate the dynamical changes across this temperature.

Analyzing the motion of H atoms

There are several space-time correlation functions that can be used to inspect the dynamical behavior of the hydrogen atoms with AIMD. First, we use a simpler method to map their motion. Making an analogy with the fluorite superionic conductors, the crossover temperature Tα marks an order-disorder transition where the mobile atoms leave their native lattice sites26,31,38. Thus, vacancies (and interstitials) are spontaneously created; these are identified as dynamic Frenkel pairs in fluorites24. To identify such vacancies, we utilize the Wigner-Seitz cell method39 to count the number of dynamic vacancies forming at each tet site, which is then averaged over the simulation time. Fig. 5(a) depicts the average vacancy concentration at different temperatures. Below 800 K, and during the simulation time of 30 ps, no significant number of vacancies are observed at the tet sites. With the temperature increasing above 800 K, a notable increase in the number of vacancies is observed, which indicates that H atoms are being thermally displaced from their original positions. Although there is a significant number of vacancies (as high as ~ 10%) at 1200 K, the oct sites, as shown in Fig. 5(b), are meagerly occupied. The displaced H atoms thus are spatially distributed across the domain.

To qualitatively assess the path of the displaced H atoms, we examine the spatial distribution of the H atoms. The YH2 supercell is first discretized into a grid of 303 (27,000) equi-sized cells with each H atom assigned to one of these cells based on its spatial coordinates. Fig. 6(a) – (d) represents contour plots that depict the probability of locating H atoms on the (110) plane for temperatures ranging from 800 K to 1200 K. Expectedly, the highest probability of H atom occupancy, regardless of the temperature, is for the tet sites represented by the dark green regions. At 800 K, in accordance with the average concentration in Fig. 5(a), most of the H atoms are vibrating about their native tet sites with some evidence of displacement towards the oct sites. At 900 K, the probability contours clearly delineate the tendency of the displaced H atoms to move into the oct sites and out; this channeling is strengthened with increasing temperature. While not completely demonstrated, a discernible pathway through the oct sites appears to connect the neighboring tet sites, possibly facilitating a rapid diffusion of H atoms within the YH2 lattice.

At the highest temperature of 1200 K, there is evidence of atoms making a tortuous path through and along the edges of the oct sites, which is strikingly similar to the convoluted migration path of anions coupled with large amplitude vibrations in fluorites40. The oct sites in YH2, unlike in fluorites superionic conductors, tend to accommodate a larger number of mobile atoms with increasing temperature as shown in Fig. 5(b). The probability map of anions in fluorites thus is more homogeneous25 compared to YH2, which shows a small but significant propensity to escort the displaced H atoms through the oct sites. The rather small probability strongly suggests that the oct sites are merely transition states and not true local minima in the potential energy landscape – a conclusion that is reached in a recent study using DFT simulations albeit at 0 K29.

Van-Hove self-correlation

The pathways of H atoms are better illustrated through the Van Hove self-correlation function Gs(r,t)25,41, which gives the probability of finding a H atom in the neighborhood of a given displacement and time given that it was located at the origin initially. For an isotropic simple liquid, the spatial Fourier transform of Gs, which is the density correlator, at long (and short) times can be shown to be proportional to an exponentially decaying function of the mean square displacement \(\left\langle {{\mathbf{r}^2}\left( t \right)} \right\rangle\), which in turn in proportional to the self-diffusivity of the species42,43. Within this approximation, Gs approaches a Gaussian function at long times. Neutron scattering evaluates self-diffusivity by measuring the incoherent scattering function, which is then fitted to a Lorentzian that corresponds to the Gaussian approximation for Gs44.

Fig. 7 depicts the Van Hove self-correlation function at 20 ps for temperatures ranging from 800 K to 1200 K (left axis). At 800 K, as shown in panel (a), Gs is mostly bounded indicating that H atoms are mostly vibrating at the tet sites. A short emergent tail suggests that a few atoms are moving to the nearby locations, which is consistent with the insignificant number of thermal vacancies generated at this temperature shown in Fig. 5(a). Along with the Gs, the radial distribution function \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\) is also shown in Fig. 7 (right axis). At 800 K, the H atoms are mostly placed at the geometric nearest neighbor (tet) sites (a/2)[1, √2, √3…], where a is the lattice parameter (~ 5.2 Å). As temperature increases, the minor shoulder at a disappears with the outer peaks merging together at ~ 6 Å. Quite remarkably, multiple peaks also appear for Gs as shown in panels (b) to (d) at higher temperatures and the Gs peaks align more or less precisely with the peaks observed in \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\). Although Gs is evaluated at 20 ps, the behavior can be observed at longer times; in the next section, we show that the relaxation time for correlated motion is of the order of few ps at 1200 K. The close correspondence between the peaks in Gs and \({g_{HH}}\left( r \right)\) demonstrates that the H atoms jump from one lattice (tet) site to another simultaneously. This cooperative motion, which becomes more pronounced with increasing temperature, is the basis of diffusive motion in YH2 above a crossover temperature of 800 K. Although speculated before16,17, the multiple peaks in Gs draw out the collective motion among the H atoms unambiguously.

It is apparent that Gs does not have a Gaussian profile as commonly assumed in diffusion modeling or for interpreting experimental data. Instead, it decays with distance in a somewhat exponential manner that suggests the presence of dynamic heterogeneity (DH) or spatially-separated clustering of fast and slow atoms45. DH is commonly observed in supercooled liquids, colloids, and granular materials46 and also in superionic conductors based on our previous work26,31. A common feature that is associated with DH is the emergence of low-dimensional or quasi-one-dimensional pathways for the diffusing species. In the next section, we will provide evidence for cooperative string-like motion of the mobile H atoms at high temperatures.

String-like pathways for H atoms

We follow the procedure of an earlier work by Annamareddy and Eapen26 and define strings as a set of ions constituted by pairs of mobile atoms where one atom gets replaced another over a certain time interval47,48. To test the presence of string-like motion, the most mobile H atoms are analyzed (20%); our main result in shown in Fig. 8(a). At 800 K or lower, the string pathways are not well-formed, which is consistent with the incipient generation of thermal vacancies. At 900 K, string formation is conspicuous and with increasing temperature, the number of participating atoms in the strings increases reaching a maximum at 1000 K (nearly 80%) followed by decreasing participation. Notably, the relaxation time monotonically decreases with increasing temperature reaching a few picoseconds at the highest temperature, which is suggestive of fast liquid-like diffusive behavior. Remarkably, the cooperative motion among the H atoms in completely analogous to that in fluorite superionic conductors26,31 and our current results provide unequivocal support for a superionic-like diffusive process in YH2 above a crossover temperature of 800 K. The hydrogen atoms typically show large amplitude oscillations before making a diffusive hop and there are several ways to visualize this motion49,50. In Fig. 8(b) we have depicted a snapshot of simultaneous hops of hydrogen atoms at 1000 K that appear as string-like displacements; detailed analysis of the string metrics such as the distribution of string lengths and lifetimes will be reported in a future publication.

From the results thus far, there is considerable evidence for an order-disorder transition at Tα ~ 800 K, which is similar to that observed for fluorite superionic conductors25,26,31. As mentioned previously, a second order phase transition marked by a theoretical discontinuity in the thermodynamic response functions (such as specific heat) is also operational in fluorites; more demanding simulations, however, at several more temperatures are needed for such evaluations. Nevertheless, there is one key evidence that foretells a superionic-like transition temperature (Tλ). In earlier studies on fluorites, Tλ is observed to coincide approximately with the peak participation in the string formation26. Based on the variation shown in Fig. 8(a), it appears that Tλ is likely to be in the vicinity of 1000 K. We will leave it to a future study with larger simulation systems and enhanced statistical sampling for probing this second order thermodynamic transition and evaluating other string metrics such as the mean string length, probability distributions and dynamic heterogeneity.

Hydrogen diffusivity

Self-diffusivity of hydrogen in YH2 using mean square displacements (MSD) and velocity autocorrelation (VAC) from AIMD simulations (solid symbols). Error bars for MSD and VACF are based on the standard error of the mean across 300 and 2,400 time origins, respectively. The error bars for diffusivity from MSD are less the symbol size. The open square symbols are experimental data on YH1.97 using neutron spectroscopy (NS)8 while the open circles represent data from pulsed field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (PFG–NMR)13 with YH1.91. A crossover can be noted in the NS data at ~ 870 K.

The self-diffusivity of the hydrogen atoms is evaluated by two equivalent methods, one based on the mean square displacement (MSD) of the diffusing atoms and the other based on the velocity autocorrelation (VAC) function. The former falls into the Einstein formalism while the latter come under the Green-Kubo formalism43. As delineated in Fig. 9, both methods yield similar results with an average activation energy of 0.83 eV. We also note that the electronic density of states does not change significantly with temperature, and electronic temperature has a minimal effect on hydrogen diffusion.

Two sets of experimental data are also shown – data on YH1.97 using neutron spectroscopy8 and data on YH1.91 from pulsed field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance13 measurements. Diffusivity is strongly dependent on stoichiometry and as previously elucidated, the diffusivity typically increases with more hydrogen content8,13 with the exception of one recent experimental study51. The closest stochiometric match is with YH1.97 used by Stuhr and coworkers8 in their neutron spectroscopic (NS) investigation. Interestingly, the NS data can be demarcated into high temperature and low temperature regimes with a crossover at ~ 870 K, which is somewhat close to the estimate from the current AIMD simulations. More strikingly, the diffusivity data from NS experiments is of the same order of magnitude as that from AIMD simulations albeit with a larger activation energy. Below 800 K, the AIMD simulations do not generate reliable mean square displacements and thus the Tα crossover is not established from the diffusivity data alone. It is likely that below the crossover temperature, a different activated mechanism may be more dominant as shown in TiHx15. The PFG–NMR measurements on YH1.91 reveal a considerably lower diffusivity that may be attributed to a lower stoichiometry. The sparsity of AIMD diffusivity data does not allow for an unambiguous identification of possible superionic transition temperatures. Future work with larger systems and more enhanced phase space sampling will draw out the transition temperatures more clearly.

Discussion

The observed activation energy of 0.83 eV includes energy for generating the thermal vacancies and for diffusion across the tet sites. A previous DFT calculation at 0 K predicts a diffusion barrier of 0.64 eV for a tet-oct pathway29, which is smaller than the current value; however, when the formation energy of the vacancies is included, the total activation energy becomes more than 2 eV. Transition state calculations based on a static energy landscape thus overestimate the average energy/migration barrier. At high temperatures, the effective barrier will include both enthalpic and entropic effects. As observed in the AIMD simulations, H atoms take a plethora of trajectories; with increasing temperatures, there are large amplitude vibrations followed by displacements that do not necessarily be described by a single reaction coordinate. The hopping itself in many instances is a complex collective process that involves the participation of several diffusing atoms simultaneously. The effective diffusion barrier thus needs to be assessed in a free energy landscape perspective that involves both vibrational and configurational entropy, the latter, which is non-trivial to estimate. When thermal energy itself is sufficient to generate a large number of displaced atoms, a static rigid potential energy landscape loses its traditional meaning; instead, a free energy landscape may be more appropriate as a dynamic or undulating construct that accommodates several competing and statistically different pathways.

Thermal effects may be incorporated in an ad hoc manner in the traditional landscape sampling methods by incorporating random displacements as done by Novoselov and Yanilkin15 in their investigation of hydrogen diffusion in titanium dihydrides that showed distinct low and high temperature behaviors. Accelerator molecular dynamics (AMD) methods52 are also better suited for analyzing activated diffusion mechanisms when the final state points are not known a priori. Nevertheless, methods such as AMD still rely on transition state theory that presume separate vibrational and diffusive timescales53. The dynamical trajectories from AIMD simulations reveal a somewhat tightly coupled vibrational and diffusive motion that may render the landscape methods less applicable above the order-disorder transition temperature. A fundamental partitioning of entropy into separate diffusive and vibrational contributions may also lead to erroneous results. The methods we have used here (MSD and VAC), on the other hand, do not presume any specific pathway or depend on the transition state theory, and thus can be considered as more reliable predictors of complex atomic diffusion processes within the simulation timescale. Given the close association between atomic vibrations and diffusion, it would be interesting to assess the role of specific phonons branches54,55,56 in the transport processes, particularly above Tα.

The diffusion process identified in our study involves cooperative motion of many atoms, which is nearly identical to that in fluorite superionic conductors. In an earlier work, Annamareddy and Eapen26 introduced the concept of thermal jamming to explain the dynamic origin of superionicity in fcc materials, which have the highest atomic packing density. Jamming can occur when accessible sites are energetically unfavorable such as the oct sites in fluorites or when mobile ions exceed the number of favorable sites. Jamming to a more perfect fcc structure through cation disorder is also seen to be responsible for increased oxygen diffusion in Gd2Zr2O757. At low levels of cation disorder, the oxygen atoms assume a defected fluorite lattice position with seven atoms sharing the eight available locations. With increasing cation disorder, the oxygen atoms tend to assume a nearly perfect cubic lattice structure with random occupancy, which enables a rapid increase in the diffusivity through concerted jumps across the lattice sites as in perfect fluorites with minimal transit through the oct sites57. In YH2 too, the oct sites are revealed to act as transitional states and not as true minima. Given the similarities, the thermal jamming perspective can be applied to YH2 to explain the large increase in H diffusivity with temperature. Based on the thermal jamming concept, we expect the collective string-like hopping process to diminish for sub stochiometric compositions (x < 2) and vice versa for super stochiometric compositions (x > 2). Indeed, most experimental data on YHx portray this general trend and the rapid rise with increasing x can be attributed to the system being driven to the jammed state (x ≥ 2) without the need to presume an increased occupancy at the oct sites as done in the past.

Conclusion

Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations are conducted to explore the diffusional properties of hydrogen in YH2 at high temperatures. An order – disorder transition takes place at Tα ~ 800 K above which hydrogen atoms diffuse through a collective string-like mechanism. With the temperature increasing above 800 K, spontaneous thermally-generated vacancies are observed, which indicates that H atoms are being thermally displaced from their original positions. Rapid increase in the diffusivity is noted above 800 K through cooperative hops across the native tet sites with an activation energy of 0.83 eV; at the highest temperature of 1200 K, the diffusivity approaches that of a liquid state. Our study reveals several close similarities between the dynamics of the hydrogen atoms in yttrium metal hydride and anions in fluorite superionic conductors. We further confirm that the oct sites are mostly unoccupied even though channeling through them is the most favored pathway between lattice hops suggesting that oct sites are merely transitional states and not true energy minimas. Our work lays the groundwork for future investigations of the complex hydrogen dynamics in metal hydrides at high temperatures.

Methods

AIMD simulations

All the calculations were performed using the AIMD method implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP); specifically, the core-valence electron interactions were treated with the projected augmented wave method (PAW)33,58,59, with PAW potentials sourced from the VASP PAW PBE 54 library. As in a previous DFT investigation on YH2, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the formulation of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerh (PBE) was employed for the exchange-energy correlation60,61; several test runs with AM05 functional62 yielded very similar structural properties (see supplementary information). For yttrium, valence electron configuration 4s24p64d25s1 includes semicore effects. For hydrogen, the valence electron configuration is 1s1. Computations were performed on a \(3 \times 3 \times 3\) YH2 supercell having 324 atoms. Partial electronic occupancies were handled using the first-order Methfessel–Paxton smearing method63 with a smearing width of 0.2 eV, which helps improve convergence by smoothing the electronic density of states near the Fermi level. A plane wave basis cutoff of 500 eV and a Monkhorst-pack grid of \(1 \times 1 \times 1\) centered at Γ point within the Brillouin zone were sufficient to have an error of 2 meV/atom or less between configurations. The convergence for electronic loop was set at 10− 6 eV. The initial atomic positions, based on the fluorite lattice structure, were relaxed using static DFT calculation to minimize forces below 10− 2 eV/Å. For the AIMD simulations, an NPT ensemble was used with the Langevin thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat64,65. The AIMD simulations were conducted with a time step of 1 fs at zero pressure for temperatures ranging from 300 to 1200 K. After obtaining the relaxed lattice parameters, a canonical NVT ensemble was used for 30 ps with a Nose-Hoover thermostat with other parameters remaining unchanged.

String analysis

We define strings as a set of ions constituted by pairs of mobile atoms where one atom gets replaced by another over a certain time interval47,48. Two atoms, i and j, are considered to form part of a string if their relative displacement satisfies one of the following conditions \(\left| {{{\varvec{r}}_i}\left( t \right) - {{\varvec{r}}_j}\left( 0 \right)} \right|<\delta\) or \(\left| {{{\varvec{r}}_j}\left( t \right) - {{\varvec{r}}_i}\left( 0 \right)} \right|<\delta\); in this analysis, we set the displacement threshold δ as 1 Å. The string analysis is performed for the most mobile atoms in the system (top 20%) that are the most likely to exhibit cooperative, string-like motion.

Data availability

Data generated from the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

CO2 emissions. Avoided by nuclear by country or region, 1971–2022. Int. Energy Agency (2023).

Black, G., Shropshire, D., Araújo, K. & van Heek, A. Prospects for nuclear microreactors: A review of the technology, economics, and regulatory considerations. Nucl. Technol. 1–20 (2022).

Vetrano, J. B. Hydrides as neutron moderator and reflector materials. Nucl. Eng. Des. 14, 390 (1971).

Shivprasad, A. P. et al. Advanced Moderator Material Handbook (FY23 Version). (Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Los Alamos, NM (United States), United States (2023).

Hu, X. & Terrani, K. A. Thermomechanical properties and microstructures of yttrium hydride. J. Alloys Compd. 867, 158992 (2021).

Cinbiz, M. N., Taylor, C. N., Luther, E., Trellue, H. & Jackson, J. Considerations for hydride moderator readiness in microreactors. Nucl. Technol. 209, S136–S145 (2023).

Barnes, R. G. In Hydrogen in Metals III: Properties and Applications (ed Helmut Wipf). (Springer, 1997).

Stuhr, U., Steinbinder, D., Wipf, H. & Frick, B. Hydrogen diffusion in f.c.c. TiHx and YHx: two distinct examples for diffusion in a concentrated lattice gas. EPL 20, 117–123 (1992).

Sköld, K. in Hydrogen in Metals I: Basic Properties (eds Georg Alefeld & Johann Völkl). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 267 (1978).

Wipf, H., Kappesser, B. & Werner, R. Hydrogen diffusion in titanium and zirconium hydrides. J. Alloys Compd. 310, 190 (2000).

Cotts, R. M. Hydrogen diffusion studies using nuclear magnetic resonance. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 76, 760 (1972).

Ramirez-Cuesta, A. J., Jones, M. O. & David, W. I. F. Neutron scattering and hydrogen storage. Mater. Today. 12, 54 (2009).

Majer, G., Gottwald, J., Peterson, D. T. & Barnes, R. G. Model-independent measurements of hydrogen diffusivity in the yttrium dihydrides. J. Alloys Compd. 330–332, 438–442 (2002).

Gissler, W. & Rother, H. Theory of the quasielastic neutron scattering by hydrogen in bcc metals applying a random flight method. Physica 50, 380 (1970).

Novoselov, I. I. & Yanilkin, A. V. Hydrogen diffusion in titanium dihydrides from first principles. Acta Mater. 153, 250 (2018).

Barnes, R. G. et al. Dynamical evidence of hydrogen sublattice melting in metal-hydrogen systems. J. Less-Common Met. 129, 279–285 (1987).

Barnes, R. G. et al. Dynamical evidence for a change in hydrogen-diffusion behavior in transition-metal hydrides at high temperatures. Phys. Rev. B. 35, 890 (1987).

Barnes, R. G. et al. Normal and anomalous nuclear spin-lattice relaxation at high temperatures in Sc-H(D), Y-H, and Lu-H solid solutions. Phys. Rev. B. 51, 3503 (1995).

Barnfather, K. J. et al. A study of high temperature hydrogen diffusion in YH1.98 and V0.25Nb0.75H0.20*. Z. Phys. Chem. 164, 935–940 (1989).

Baker, D. B., Conradi, M. S., Norberg, R. E., Barnes, R. G. & Torgeson, D. R. Explanation of the high-temperature relaxation anomaly in a metal-hydrogen system. Phys. Rev. B. 49, 11773 (1994).

Cotts, R. M. Would hydrogen pairing at high temperatures account for nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation anomalies in metal hydrides? J. Less-Common Met. 172–174, 467 (1991).

Phua, T. T. et al. Paramagnetic impurity effects in NMR determinations of hydrogen diffusion and electronic structure in metal hydrides. Gd3+ in YH2 and LaH2.25. Phys. Rev. B. 28, 6227–6250 (1983).

Shivprasad, A. P. et al. Thermophysical properties of high-density, sintered monoliths of yttrium dihydride in the range 373–773 K. J. Alloys Compd. 850, 156303 (2021).

Hull, S. Superionics: crystal structures and conduction processes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 67, 1233 (2004).

Annamareddy, A. & Eapen, J. Disordering and dynamic self-organization in stoichiometric UO2 at high temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 483, 132–141 (2017).

Annamareddy, A. & Eapen, J. Low dimensional string-like relaxation underpins superionic conduction in fluorites and related structures. Sci. Rep. 7, 44149 (2017).

Trofimov, A. A., Hu, X., Wang, H., Yang, Y. & Terrani, K. A. Thermophysical properties and reversible phase transitions in yttrium hydride. J. Nucl. Mater. 542, 152569 (2020).

Mehta, V. K. et al. A density functional theory and neutron diffraction study of the ambient condition properties of sub-stoichiometric yttrium hydride. J. Nucl. Mater. 547, 152837 (2021).

Tunes, M. A. et al. Challenges in developing materials for microreactors: A case-study of yttrium dihydride in extreme conditions. Acta Mater. 280, 120333 (2024).

Sundar, A., Huang, Y., Yu, J. & Cinbiz, M. N. The impacts of charge transfer, localization, and metallicity on hydrogen retention and transport capacity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 47, 20194–20204 (2022).

Annamareddy, V. A., Nandi, P. K., Mei, X. & Eapen, J. Waxing and waning of dynamical heterogeneity in the superionic state. Phys. Rev. E. 89, 010301 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758 (1999).

Daou, J. N. & Vajda, P. Hydrogen ordering and metal-semiconductor transitions in the system YH2 + x. Phys. Rev. B. 45, 10907 (1992).

Chapman, C. W. et al. Thermal neutron scattering measurements and modeling of yttrium-hydrides for high temperature moderator applications. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 157, 108224 (2021).

Wendt, H. & Abraham, F. F. Empirical criterion for the glass transition region based on Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 1244 (1978).

Celtek, M., Sengul, S., Domekeli, U. & Guder, V. Dynamical and structural properties of metallic liquid and glass Zr48Cu36Ag8Al8 alloy studied by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 566, 120890 (2021).

Hutchings, M. T. et al. Investigation of thermally induced anion disorder in fluorites using neutron scattering techniques. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 17, 3903 (1984).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Mohn, C. E., Stølen, S., Norberg, S. T. & Hull, S. Oxide-ion disorder within the high temperature δ phase of Bi2O3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 155502 (2009).

Van Hove, L. Correlations in space and time and born approximation scattering in systems of interacting particles. Phys. Rev. 95, 249 (1954).

McQuarrie, D. A. Statistical Mechanics (University Science Books, 2000).

Boon, J. P. & Yip, S. Molecular Hydrodynamics (Dover, 1991).

Boothroyd, A. T. Principles of Neutron Scattering from Condensed Matter (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Ediger, M. D. Spatialy heterogeneous dynamics in supercooled liquids. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 51, 99 (2000).

Chaudhuri, P., Berthier, L. & Kob, W. Universal nature of particle displacements close to glass and jamming transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 060604 (2007).

Gebremichael, Y., Vogel, M. & Glotzer, S. C. Particle dynamics and the development of string-like motion in a simulated monoatomic supercooled liquid. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 4415–4427 (2004).

Donati, C. et al. Stringlike cooperative motion in a supercooled liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2338 (1998).

Sau, K., Ikeshoji, T., Kim, S., Takagi, S. & Orimo, S.I. Comparative molecular dynamics study of the roles of anion–cation and cation–cation correlation in cation diffusion in Li2B12H12 and LiCB11H12. Chem. Mater. 33, 2357–2369 (2021).

Xu, M., Ding, J. & Ma, E. One-dimensional stringlike cooperative migration of lithium ions in an ultrafast ionic conductor. Appl Phys. Lett 101 (2012).

Cakmak, E. et al. Hydrogen motion in near stoichiometric yttrium dihydride at elevated temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 593, 154972 (2024).

Voter, A. F., Montalenti, F. & Germann, T. C. Extending the time scale in atomistic simulation of materials. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 32, 321–346 (2002).

Kushima, A., Eapen, J., Li, J., Yip, S. & Zhu, T. Time scale bridging in atomistic simulation of slow dynamics: viscous relaxation and defect activation. Eur. Phys. J. B. 82, 271 (2011).

Raj, A. & Eapen, J. Phonon dispersion using the ratio of zero-time correlations among conjugate variables: computing full phonon dispersion surface of graphene. Comput. Phys. Commun. 238, 124 (2019).

Raj, A. & Eapen, J. Deducing phonon scattering from normal mode excitations. Sci. Rep. 9, 7982 (2019).

Raj, A. & Eapen, J. Exact diagonal representation of normal mode energy, occupation number, and heat current for phonon-dominated thermal transport. J. Phys. Chem. 151, 104110 (2019).

Annamareddy, A. & Eapen, J. Decoding ionic conductivity and reordering in cation-disordered pyrochlores. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 379, 20190452 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B. 48, 13115 (1993).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1997).

Ernzerhof, M. & Scuseria, G. E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 5029 (1999).

Mattsson, A. E. et al. The AM05 density functional applied to solids. J Chem. Phys 128 (2008).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B. 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: A molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1196–1199 (1980).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Acknowledgements

Funding from Idaho National Laboratory LDRD and NUC faculty summer program are gratefully acknowledged (YH and JE). This work is also partly supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) under the contract DE-AC05-00OR227 (MNC and JY). The authors also thank useful discussions with A. P. Shivprasad and W. P. Scarlett.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH performed the simulations, analyses and prepared the first draft of the manuscript; all the authors contributed to writing the final manuscript. The project was conceived by JE, MNC and JY. Since the manuscript is co-authored by UT-Battelle, LLC, and partially supported by the US DOE, the US government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (http://energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Yu, J., Cinbiz, M.N. et al. Superionic-like diffusion in yttrium dihydride. Sci Rep 15, 18144 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02515-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02515-9