Abstract

Moderate dietary restriction (DR) is known to extend lifespan, but its long-term safety remains unclear. In this study, silkworms of P50 were divided into libitum feeding (AL) and DR groups, with the DR group receiving 65% of the AL group’s intake. Using the contemporary DR cohort as the parent generation, the identical dietary restriction methodology is perpetuated across successive generations to establish a multi-generational DR model. We recorded body weight, lifespan, spawning amount, and cocoon shell rate at each generation, and analyzed tissue sections of the G6 generation. Biochemical indices of hemolymph were assessed in the G0 and G3 generations, and the expression levels of genes associated with DR metabolism were analyzed using quantitative PCR. The result showed that DR initially caused weight loss, which then stabilized, and significantly extended lifespan. Biochemical indicators showed that silkworm’s antioxidant capacity improved significantly in DR group, with notable differences between the current (G0) and successive (G3) generations. Gene expression related to oxidative stress was significantly altered depending on there function in G3 compared to G0. This suggests that long-term moderate DR can extend lifespan and reduce weight and fat, mainly due to enhanced antioxidant capacity. Additionally, animals demonstrated adaptability to prolonged moderate DR, indicating its feasibility across generations in insects. Our study confirms that boosting antioxidant capacity is a healthy, life-extending strategy under dietary restriction and highlights the adaptability of animals to such diets over generations, supporting the development of safe, long-term dietary plans for humans and large animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the elevation of living standards, the prevention of diseases and the extension of healthy lifespan have gradually become issues of particular concern in the global scientific/medical communities. Moderate dietary restriction (DR), which is generally considered not less than 60% of the normal amount, is by far the most effective and healthy intervention measure for lifespan extension, which has been verified in multiple model organisms as well as silkworm1,2,3,4,5. Scientific DR has been shown to effectively manage weight6, enhance cardiometabolic health5, and slow the progression of neurodegenerative diseases7. Additionally, DR can modulate gut microbiota to improve immune aging8, etc. Current evidence supports the potential health benefits of long-term, moderate DR in healthy young and middle-aged individuals, with no significant increase in reported adverse events9,10. A 15-year observational study demonstrated the long-term benefits of DR13.This evidence indicates that the implementation of prolonged moderate DR may confer certain health advantages. However, extended DR has been associated with decreased metabolic parameters in rodents, including reductions in body temperature, resting metabolic rate, markers of oxidative stress, and fasting insulin levels14. Additionally, DR typically results in diminished reproductive15.Studies on nematodes have demonstrated that parental DR can influence the longevity and fitness of offspring, exhibiting notable cross-generational effects16. Consequently, it remains uncertain whether organisms can achieve a balance and adapt to prolonged dietary restriction while considering the associated costs to healthy survival and reproduction.

Given the extended human life cycle and the ethical constraints on certain types of research17, it is challenging to assess the feasibility of sustaining long-term DR in humans. So studies on the transgenerational effects of DR have predominantly utilized model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. B.mori, a representative invertebrate model within the Lepidoptera order, has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its unique advantages2,18,19,20. The application of the silkworm in nutritional restriction research dates back to the early 20th century21. More recently, it has been extensively adopted as a model for studies on dietary restriction2,22,23,24,25,26. Similar to nematodes and fruit flies, silkworms present fewer ethical concerns compared to mammalian models27,28. Furthermore, the moderate size of individual silkworms and their organs facilitates the extraction of various tissues for physiological and biochemical analyses. Additionally, the controlled laboratory environment allows for precise regulation of feeding duration and food intake. The silkworm exhibits a moderate life cycle, produces multiple offspring, and possesses a well-defined genetic background. A particularly significant attribute is the ability to preserve silkworm eggs across generations, allowing for the simultaneous incubation and rearing of different generations and treatments. This facilitates the analysis of intergenerational differences. Consequently, the silkworm is considered an ideal model organism for studying the effects of DR across multiple generations.

In recent years, substantial research efforts have been directed towards elucidating the mechanisms by which food restriction extends healthspan and lifespan. It has been demonstrated that the body adapts to nutritional changes by modulating the neuroendocrine system, mitigating inflammation, and preventing oxidative stress damage3,29,30,31.The regulation of these signaling pathways has been thoroughly reviewed by Cara L. Green et al.10, the nutritional signaling pathways primarily encompass insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), AKT signaling, and epigenetic mechanisms, among others. These evidences furnish the molecular basis for our analysis of the interrelationship between these phenomena and natural processes, subsequent to the development of a cross-generational DR model. Based on contemporary research, moderate DR demonstrates potential biological health benefits and is implicated in various signaling pathways. However, there is a lack of data to assess the health risks associated with long-term DR, and the feasibility of maintaining balanced nutrition under prolonged DR as a safe strategy for life extension remains uncertain. Therefore, we utilized the model organism B.mori, leveraging its advantages as a medical research model to establish an animal model of DR acrossing more than four generations, feed amount to approximately 65% that provided to the AL group by adjusting the feeding schedule. and analyzed the effects of moderate DR on life indicators, main biochemical indices and genes related to DR metabolism. Based on current global life expectancy statistics(World Population Prospects (un.org), Life expectancy at birth, total (years) | Data (worldbank.org)), the generational span of silkworms, when converted to the equivalent time for four human generations, is approximately 300 years. The findings demonstrated that silkworms exhibit a degree of adaptability to prolonged moderate DR, particularly in terms of reproduction and survival. Long-term moderate DR was found to extend lifespan and decrease both body weight and fat content, primarily due to enhanced antioxidant capacity. These results lay the groundwork for the formulation of safe, long-term moderate dietary programs for humans and large animals.

Materials and methods

Establishment of the across-generation DR model and life indices survey in silkworm

The B. mori P50 strain was bred and preserved by the key laboratory of silkworm and mulberry genetic improvement. Diapause-terminated eggs (induced by HCl exposure) were incubated in indoor natural light at 25 °C. After hatching, silkworm larvae were reared with fresh mulberry leaves at 25 ± 1 °C. At the second instar stage, the larvae were randomly divided into two groups. The AL group was given food twice a day and allowed uninterrupted feeding during the entire day. The DR group was given mulberry leaves once a day and allowed to feed for 16 h; there was no food available for the other 8 h. Given that DR extends lifespan, it’s impractical to match daily feed amounts between AL and DR groups. Following Chinese sericulture standards32, we adjusted the DR group’s feed to about 65% of the AL group’s by modifying the feeding schedule. Each group consisted of three replicates, with each replicate containing 100 silkworms. Post-oviposition, a subset of the eggs underwent immediate acid treatment and were subsequently maintained for breeding purposes, while another subset was kept for later use without treatment. This feeding regimen was consistently applied across three generations within a single year. In the following spring, both the G0 and G3 generations were concurrently fed to facilitate a comparative analysis of the physiological effects resulting from across-generational food restriction. The daily food intake, body weight, age, elapsed time, and other indices were investigated at each generation (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the testes and fat body from G6 AL and DR specimens were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (E672002-0100, BBI, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, paraffin-embedded sections were prepared and analyzed (Powerful Biology, Wuhan, China).

Measurement of physiological and biochemical indices

Hemolymph samples, comprising mixed male and female specimens were collected respectively from the 5th instar and pupal stages of the G0 and G3 generations within both AL and DR groups. These samples were stored in centrifuge tubes pre-treated with phenylthiourea and subsequently kept at -80℃ for the following analysis. For the detection of trehalose, the hemolymph samples were first processed by taking 100 µL and adding 0.9 mL of extraction solution. The mixture was thoroughly combined and allowed to stand at room temperature for 45 min, during which it was oscillated 3 to 5 times. Following this incubation period, the mixture was cooled and centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at room temperature. After diluting 12 µL of supernatant fivefold with distilled water, the trehalose content was quantified using a trehalose assay kit (BC0335, Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the operating instructions. The total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) was assessed by diluting 5 µL of hemolymph tenfold with distilled water and following the instructions provided with the assay kit (BC1315, Solarbio, Beijing, China). Free fatty acids (FFA) and uric acid (UA) were directly measured in the hemolymph according to the respective kit instructions (KTB2230, Abbkine, Wuhan, China) and (KTB1510, Abbkine, Wuhan, China). Each biochemical index was analyzed in triplicate.

Selection of potential genes and quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Based on the references, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and the SilkDB 3.0 silkworm genome database (https://silkdb.bioinfotoolkits.net/) were utilized to preliminarily screen 26 genes potentially related to DR metabolism. Primers for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were subsequently designed (Table 1). Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol method (9109, Takara, Beijing, China), the separation of organic and inorganic phases was achieved using chloroform, followed by RNA precipitation with isopropyl alcohol. Subsequently, the chloroform and isopropyl alcohol were washed with 75% ethanol. The RNA concentration was then quantified (NanoDrop 2000,Thermo Fisher, USA) using dissolved RNA precipitation, with 1 µg RNA serving as the standard., cDNA synthesis was performed with the HiFiScript gDNA Removal RT MasterMix kit (CW2020M, CWBIO, Jiangsu, China) according to operating instructions, employing Bmrp4933,34,35 as the internal reference gene. Utilizing 1.5µL 4-fold diluted cDNA (obtained by reverse transcription of 1ug mRNA) as template in 20 µL reaction systerm, the cycling program was established in accordance with the kit instructions (Q711, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s; followed by a final denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 60 °C for 60 s, and a final denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s. The mRNA expression levels of each gene were quantified using a real-time quantitative PCR instrument (ABI 7500, Thermo Fisher, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. The significance of key life indices was assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Additionally, comparisons between physiological and biochemical indicators, as well as individual gene expressions, were analyzed using a bidirectional ANOVA with multiple comparison tests.

Results

The silkworm exhibits a certain degree of adaptability to successive generations of moderate DR

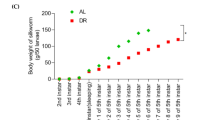

Following an extended period of moderate DR, a significant decrease in average body weight was observed during the late larval stage. However, with the progression of generations, the timing and magnitude of significant differences between the AL and DR groups were both delayed and diminished (Fig. 2a). The trend in body weight differences between the AL and DR groups remained consistent across all generations, and no significant intergenerational differences were detected (Fig. 2b). All generations subjected to DR exhibited a significant extension in lifespan (Including larval stage, pupal stage and adult stage) (Fig. 3a), and this life-extending effect did not diminish appreciably in the successive generations (Fig. 3b). Although fecundity (spawning amount) and economic traits (cocoon shell rate) were reduced, these adverse effects of DR on spawning amount and cocoon shell rate intensified in the second generation (G1) and began to attenuate in the third generation (G2). However, when exposed to adverse environmental conditions, the differences between the groups showed a slight resurgence. For instance, the fourth generation of eggs subjected to a low temperature of 5℃ for over 90 days exhibited a lesser impact compared to the second generation (Figs. 4 and 5).Studies have demonstrated that dietary restriction (DR) can reduce reproductive rates37. However, prolonged DR may lead to an evolutionary reallocation of resources towards reproduction and growth37,38,39, potentially decreasing somatic cell growth rate in favor of enhancing reproductive capacity40. In the case of silkworms, eggs allocate a portion of their resources to basic energy consumption and improve cold tolerance during overwintering41,42. The glycogen stored in silkworm eggs is converted into sorbitol and glycerol, which function as antifreeze agents, aiding survival under cold winter conditions43. Consequently, the observed decline in fertility by the third generation (G3) is understandable. In addition, we examined tissue sections from the G6 generation AL and DR groups and observed a reduction in the number of sperm bundles in the DR group (Fig. 6a & d). Additionally, the fat body exhibited decreased fat density and thinner cells in both the 5th instar and the pupal stage (Fig. 6b, c, e, f), aligning with the observed decline in weight and fecundity in the DR group. This observation suggests that although the status of successive multi-generational DR tissues was slightly worse than that of the AL group, moderate DR across successive generations can effectively extend lifespan, reduce body weight and fat, and minimize economic traits, while still allowing for safe reproduction and generational continuity in the silkworm. Consequently, the feasibility of moderate DR across successive generations in insects is demonstrated.

The impact of across-generations of moderate DR on the body quality of silkworms. (a) The absolute weight difference between DR and AL in each generation from G0 to G3. (b) Comparison of weight differences between DR and AL groups across G0 to G3 generations. G0: the first generation; G1: the second generation; G2: the third generation; G3: the fourth generation. Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001;*** p <0.001*p < 0.05.

The effects of across-generations of moderate DR on the longevity of silkworms. (a) The lifespan differences between G0 to G3 generations of DR and AL groups. (b) The differential life extension effects of DR compared to the AL group across generations G0 to G3.Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001;*p < 0.05.

The impact of across-generations of moderate DR on spawning amount of silkworm. (a)The absolute difference in spawning amount between the G0-G3 generations of DR and AL groups; (b) The relative reduction in egg production between the G0-G3 generations in the DR group compared to the AL group. Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001;*** p < 0.001*p < 0.01.

Effect of across- generations of moderate DR on cocoon shell rate of silkworms. (a) The absolute difference in cocoon shell rate between the G0-G3 generations of DR and AL groups; (b) The relative reduction in cocoon shell rate between the G0-G3 generations in the DR group compared to the AL group. Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001;**p < 0.01*p < 0.05.

Effect of across- generations of moderate DR on physiological state of tissues of silkworms, Bombyx mori. (a) The absolute difference in cocoon shell rate between the G0-G3 generations of DR and AL groups; (b) The relative reduction in cocoon shell rate between the G0-G3 generations in the DR group compared to the AL group. Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001;**p < 0.01*p < 0.05.

The following descriptions pertain to tissue paraffin sections: (a) G6 AL testis at the fifth day of fifth instar ; (b) G6 AL fat body at the fifth day of the fifth instar; (c) G6 AL fat body at the third day of the pupal stage ; (d) G6 DR testis at the fifth day of fifth instar; (e) G6 AL fat body at the fifth day of the fifth instar; (f) G6 AL fat body at the third day of the pupal stage. Sections (c) and (f) are presented at 100 μm magnification, while the remaining sections are at 200 μm magnification.

The silkworm improves its antioxidant capacity and other biochemical indices to adapt to across-generational dietary restriction

Physiological and biochemical activities are the basic processes of living organisms. By measuring physiological and biochemical indices, we can analyze the life activities of silkworms and thus understand the effects of moderate DR on their life activities.

The antioxidant capacity of hemolymph is one of the indices for evaluating healthy diets. Our results show that the antioxidant capacity of DR groups significantly increases regardless of the current (G0) or successive (G3) generations, regardless of the fifth instar or the pupal stage, and the G3 are significantly higher than the G0 generation (Fig. 7a). This may be the essence of sustained diet restriction for healthy longevity.

Free fatty acids are derived from carbohydrates and are the substances needed for sustained activities. Therefore, the results are consistent with the existing conclusions .Where the DR group increases the source and storage (mainly occurs at 5th instar) of free fatty acids under limited energy intake conditions, and fully utilizes free fatty acids at pupal stage, Despite the overall decrease in energy storage and utilization capacity in DR group, the storage and utilization of free fatty acids are significantly increased in the G3compared to that in the G0 generation(Fig. 7b).

Uric acid is a product of purine metabolism and accumulating too much indicates the onset of diseases. There is no significant difference in uric acid content between the AL and DR groups in the middle 5th instar, as most of the uric acid is excreted from the body during larval stage metabolism (Fig. 7c). However, the uric acid content in the pupal stage rises sharply due to various metabolic processes occurring within the body, but the pupae do not excrete it, leading to a sharp rise in uric acid content in the body. Since the DR group has a lower energy intake, the corresponding uric acid content also decreases, and the body is actually healthier. Trehalose is the main circulating sugar in insect hemolymph. In the DR group with lower food intake at 5th instar, sucrose is mainly used to synthesize sorbitol and glycerol, and limited energy intake leads to a decrease in trehalose content (Fig. 7d). However, in the energy conversion and utilization stage of the pupa, sugar is converted into trehalose for growth and development in greater amounts. However, it is important to highlight that no significant differences were observed in the changes of uric acid and trehalose levels between the group subjected to multiple generations of DR and the group with DR only in the first generation. This may suggest that the body strives to achieve a balance of intake, excretion, and utilization through its intrinsic regulatory mechanisms.

In summary, the body ensures healthy longevity in a restricted diet by balancing sugar and lipid metabolism and enhancing antioxidant capacity. Furthermore, with the accumulation of generations of DR, especially for the total antioxidant capacity and free fatty acid level, the balance ability is gradually enhanced.

This figure illustrates the primary biochemical indices in silkworms subjected to dietary restriction compared to those reared under normal conditions. The hemolymph was the analyzed tissue, with the following parameters measured: (a) total antioxidant capacity, (b) free fatty acid levels, (c) uric acid levels, and (d) trehalose levels. The experimental groups are denoted as follows: G0-AL represents the first generation of libitum feeding, G0-DR indicates the first generation of dietary restriction, G3-AL signifies the fourth generation of libitum feeding, and G3-DR denotes the fourth generation of dietary restriction. The developmental stages assessed include the middle 5th instar (3rd or 4th day of the 5th instar) and the middle pupal stage (Day 5 of the pupal stage).Significance levels are indicated as follows:**** p < 0.0001;*** p < 0.001**p < 0.01.

The level of activation of oxidative stress and other pathway genes in across- generations of DR groups is significantly changed in the silkworm

The genetic code stored in DNA is translated through gene expression, and the characteristics of gene expression produce the phenotype of the organism. Therefore, the regulation of gene expression is crucial for the development of the organism. We screened 26 DR metabolism-related genes reported in the literature, of which 9 showed significant differences between G0 and G3, among which activating transcription factor of chaperone (ATFC), biogenesis of lysosome-related organelle complex 1 subunit 1 (BLOS1), forkhead box O (FOXO), fibroblast growth factor 16 (FGF16), s-adenosyl methionine synthetase (SAMS) are related to oxidative stress, while diacylglycerol-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) and the main constituent protein of mTORC2 (RICTOR) mainly participate in sugar and lipid metabolism, and transcription factor EB (TFEB), forkhead box L (FOXL22) are key genes for autophagy and longevity(Fig. 8). In the feeding period at fifth instar, except for RICTOR, the expression of 8 genes in the G0 DR group was significantly higher than that in the G3 DR group, and the difference between G3 DR and AL was smaller than that in G0, indicating that the silkworm genes are gradually adapting to the amount of nutrient intake (Fig. 8a). In the energy allocation period during the pupal stage, however, the expression of most genes in the G3 DR group was significantly higher than that in the G0 DR group, and the difference between G3 DR and AL was significantly higher than that in G0 (Fig. 8b), indicating that the body regulates gene expression to improve the utilization of limited resources during the energy conversion and utilization stage. These data suggest that the body can gradually adapt to energy intake through gene regulation and enhance its antioxidant capacity, but due to nutritional limitation, the adjustment in energy conversion and utilization regulation is larger with the increase of dietary restricted generations.

Differential gene expression related to dietary restriction metabolism. (a) Comparative expression analysis of key genes during the feeding period at 5th instar (specifically on the 3rd or 4th day) between the DR and AL group. (b) Comparative expression analysis of key genes at the middle pupal stage (day 5) between the DR and AL group. G0-AL represents the first generation of libitum feeding, G0-DR indicates the first generation of dietary restriction, G3-AL signifies the fourth generation of libitum feeding, and G3-DR denotes the fourth generation of dietary restriction. Significance levels are indicated as follows: **** p < 0.0001; *** p < 0.001; * p < 0.05.

Discussion

Caloric restriction, reducing energy intake by 10–50% without nutrient deficiency, has shown life-extending benefits in rodents and primates44,45. A 15-year study indicated long-term benefits but lacked data on adverse effects13. Due to reduced metabolic levels in rodents14, evidence is insufficient to confirm long-term nutritionally balanced caloric restriction as a safe strategy for extending healthy life. This study utilized the silkworm, Bombyx mori to create a across-generation DR model. Despite reductions in body weight, reproductive capacity, and economic indicators, silkworms exhibited life extension and safely passed through generations. Adverse effects diminished with increased dietary restriction, demonstrating the silkworm’s adaptability to long-term moderate DR. Epigenetics significantly influences the adaptive potential of individuals and populations, with adaptations to environmental and nutritional conditions observed across multiple generations in various species46,47,48,49,50,51,52. Based on initial evidence, we will continue modeling to assess the accuracy of the body’s adaptation to long-term moderate DR.

Physiological and biochemical indices reveal life activity patterns, aiding in understanding the impact of moderate DR on silkworms. This study examined changes in total antioxidant capacity, free fatty acids, uric acid, and trehalose in B.mori over several generations of moderate DR, focusing on antioxidants, glycolipid metabolism, energy use, and excretion. Antioxidant capacity indicates diet health53. Free fatty acids are essential for sustained activity54,55. Uric acid, the end product of purine metabolism, can indicate diseases like gout and nephritis when elevated due to excessive intake and poor excretion53,56. Trehalose, a key sugar in insect hemolymph, is linked to stress responses and insect growth and development57,58. In middle 5th instar, the body absorbs and produces energy by breaking down fat and converting glycogen into sorbitol and glycerol, resulting in low trehalose formation and free fatty acid accumulation. The body mitigates oxidative damage from these fatty acids by boosting antioxidant capacity, a process significantly enhanced by across-generation DR. During the middle pupal stage, trehalose and free fatty acids in the DR group showed opposite trends due to the interplay of glucose and lipid metabolism compared to 5th instar. This led to increased total antioxidant capacity and uric acid, contributing to health and longevity. These effects were notably amplified by multiple generations of food restriction. Our current data indicate that the diapause of silkworms is influenced by dietary restrictions across generations. Typically, the accumulation of trehalose during the pupal stage is observed during diapause egg production59,60, a phenomenon that contrasts with our findings. Given the critical role of hormones in diapause regulation61,62,63, we investigated the differences in diapause hormone, juvenile hormone, and ecdysone between DR and AL populations. However, no consistent significant differences were observed. This discrepancy may be attributed to the metabolic balance between glucose and lipid metabolism under conditions of nutritional restriction. It is hypothesized that this variation could represent an adaptive mechanism for coping with nutritional limitations in silkworms. Further investigation is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Gene expression regulation is crucial for organism development. Recent research has focused on how food restriction extends health and lifespan, revealing that the body adapts to nutritional changes by adjusting the neuroendocrine system, reducing inflammation, and preventing oxidative stress2,3,29,30,31. Cara L. Green et al. comprehensively summarize the regulation of these signaling pathways in their review10.Based on those conclusions, we screened 26 genes linked to DR metabolism and found 9 with significant differences between G0 and G3, primarily related to oxidative stress and glycolipid metabolism. At the time of energy intake and conversion in pupae, these gene differences showed opposite trends between the G0 and G3 DR groups compared to that in 5th instar. At the middle 5th instar, the expression of 8 genes in the G0 DR group was significantly higher than that in the G3 DR group, and the difference between G3 DR and AL was smaller than that between G0 DR and AL; On the contrary, in the middle pupal stage, the expression of most genes in G0 DR Group was significantly lower than that in G3 DR Group,, and the difference between G3 DR and AL was significantly higher than that between G0 DR and AL, indicating that silkworm genes can gradually adapt to the amount of nutrient intake, and can improve the utilization of limited resources through gene expression regulation in the energy conversion and utilization stage. With the increase of restricted feeding generations, gene regulation can enhance antioxidant capacity and gradually adapt to across-generation restricted feeding to achieve healthy longevity. Of course, as the modeling continues and the research deepens, we will strive to overcome the non-genetic, heritable stress changes in physiological indicators, and we hope to obtain targets for the body to adapt to across-generational dietary restriction through large-scale screening of metabolomics and transcriptomics. This endeavor is expected to inform the development of dietary restriction-simulated drugs and foods, as well as the formulation of safe and health-promoting dietary programs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that moderate dietary restriction across generations leads to reductions in body weight, reproductive capacity, and economic traits in silkworms; however, these adverse effects attenuate over time. Notably, lifespan extension is both evident and enduring. Additionally, there is an observed increase in antioxidant capacity and the expression of oxidative stress-related genes with successive generations. The overarching regulatory mechanisms are encapsulated in the simulation diagram (Fig. 9). This evidence suggests that sustained moderate dietary restriction may contribute to lifespan extension, reduction in body weight and fat, and the development of specific reproductive and generational adaptability in animals. These findings offer empirical support for the development of healthier long-term nutritional restriction programs. However, the significant impacts of prolonged dietary restriction on organisms, particularly in response to environmental and nutritional conditions, often manifest over several or even multiple generations.

In this diagram, pink denotes physiological and biochemical indices, while light green signifies related genes. The red upward arrow indicates that the biochemical indices of the Dietary Restriction (DR) group, compared to the Ad Libitum (AL) group, exhibit an upward trend across various instars. Conversely, the black downward arrow signifies a downward trend in the biochemical indices of both the DR and AL groups across different instars. Additionally, the black horizontal line represents that the biochemical indices of both groups remain relatively unchanged during the middle of the fifth instar.

Data availability

Most of the analytical data are provided in the article. More original datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Napoleão, A., Fernandes, L., Miranda, C. & Marum, A. P. Effects of calorie restriction on health span and insulin resistance: classic calorie restriction diet vs. Ketosis-Inducing Diet. Nutrients. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041302 (2021).

Wang, M. S., Tan, Y., Yasen, Z., Fan, A. & Shen, B. Metabolomics analysis of dietary restriction results in a longer lifespan due to alters of amino acid levels in larval hemolymph of Bombyx mori. Sci. Rep. 13, 6828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34132-9 (2023).

Loo, J., Shah Bana, M. A. F., Tan, J. K. & Goon, J. A. Effect of dietary restriction on health span in Caenorhabditis elegans: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 182, 112294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2023.112294 (2023).

Krittika, S. & Yadav, P. The Seesaw of diet restriction and lifespan: lessons from Drosophila studies. Biogerontology 22, 253–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-021-09912-3 (2021).

Xie, D. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of caloric restriction-induced changes in the metabolome profile of mice. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 19 (1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-022-00674-4 (2022).

Zhong, W. W. et al. High-protein diet prevents fat mass increase after dieting by counteracting Lactobacillus-enhanced lipid absorption. Nat. Metab. 4, 1713–1731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-022-00687-6 (2022).

Fontana, L., Ghezzi, L., Cross, A. H. & Piccio, L. Effects of dietary restriction on neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disease. J. Exp. Med. 218 (2), e20190086. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20190086 (2021).

Sbierski-Kind, J. G. et al. Effects of caloric restriction on the gut Microbiome are linked with immune senescence. Microbiome 10 (1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01249-4 (2022).

Sergei, V. et al. Eric Ravussin5, William E. Kraus. Safety of two-year caloric restriction in non-obese healthy individuals. Oncotarget 7, 19124–19133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.005 (2016).

Green, C. L., Lamming, D. W. & Fontana, L. Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00411-4 (2022).

Colman, R. J. et al. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat. Commun. 5, 3557. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4557 (2014).

Mattison, J. A. et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 489, 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11432 (2012).

Most, J., Tosti, V., Redman, L. M. & Fontana, L. Calorie restriction in humans: An update. Ageing Res. Rev. 39, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.005 (2017).

Fontana, L. The scientific basis of caloric restriction leading to longer life. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 25, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e32831ef1ba (2009).

Andrew, W., McCracken, G. A., Hartshorne, L., Tatar, M. & Mirre, J. P. Simons the hidden costs of dietary restriction: Implications for its evolutionary and mechanistic origins. Sci. Adv. 21, eaay3047. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay3047 (2020).

Ivimey-Cook, E. R. et al. Transgenerational fitness effects of lifespan extension by dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Biol Sci 288 20210701, (1950). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0701 (2021).

Pifferi, F. & Aujard, F. Caloric restriction, longevity and aging: Recent contributions from human and non-human primate studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 95, 109702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109702 (2019).

Chen, Y. H. et al. Dual roles of myocardial mitochondrial AKT on diabetic cardiomyopathy and whole body metabolism. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02020-1 (2023).

Song, J. et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide improves dopamine metabolism and symptoms in an MPTP-induced model of Parkinson’s disease. BMC Med. 20, 412. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02621-9 (2022).

Ma, L. et al. Subchronic toxicity of magnesium oxide nanoparticles to Bombyx mori silkworm. RSC Adv. 12, 17276–17284. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra01161a (2022).

Kellogg, V. L., VARIATIONS INDUCED IN, R. G. B. & LARVAL, PUPAL AND IMAGINAL STAGES OF BOMBYX MORI BY CONTROLLED VARYING FOOD SUPPLY. Science 18(467), 741–748, doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.18.467.741 (1903).

Pan, Y. et al. Dietary restriction alters the fatbody transcriptome during immune responses in Bombyx mori. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 223, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpb.2018.06.002 (2018).

Song, J. et al. Variation of lifespan in multiple strains, and effects of dietary restriction and BmFoxO on lifespan in silkworm, Bombyx mori. Oncotarget 8 (5), 7294–7300. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14235 (2017).

Gan, L., Liu, R., Long, F., Zhang, J. & Xu, S. The expression of Serine proteinases (SPs) and Serine protease inhibitor (Serpins) genes in silkworms, Bombyx Mori, treated with hormones and subject to food restriction. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 51 (5), 1255–1267. https://doi.org/10.7679/j.issn.2095/1353.2014.149 (2014). (In chinese).

Lu, Y. et al. Dietary restriction affects expression of Sir2 and other Life-Span related genes and prolongs Life-Span in model organism silkworm Bombyx mori. Sci. Seric. 48 (6), 0505–0512 (2022). (In chinese).

Tan, Xue, P. & Xu, J. Effects of diet restriction on life span, reproductive performance And some physiological indexes of Bombyx mori. China Seric. 40 (2), 12–19 (2019). (In chinese).

Nwibo, D. D., Hamamoto, H., Matsumoto, Y., Kaito, C. & Sekimizu, K. Current use of silkworm larvae (Bombyx mori) as an animal model in pharmaco-medical research. Drug Discov Ther. 9, 133–135. https://doi.org/10.5582/ddt.2015.01026 (2015).

Jiangbo Song, J. Z. & a., F. D. Advantages and limitations of silkworm as an invertebrate model in aging and lifespan research. OAJ Gerontol. Geriatric Med. 4 (4), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.19080/OAJGGM.2018.04.555641 (2018).

Kenneth, A. et al. Brownridge III,JenniferN.Beck,Jacob Rose, Melia Granath-Panelo,Grace Qi, AkosA.Gerencser,Jianfeng Lan,Alexandra Afenjar, Geetanjali Chawla, RachelB.Brem Campeau, HugoJ.Bellen Nicholas T. Seyfried, LisaM.Ellerby, Birgit Schilling & Pankaj Kapahi OXR1 maintains the retromer to delay brain aging under dietary restriction. Nat Commun 15, 467, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44343-3

Lim, C. Y., L., H. T., C.Wang, F. Y. & Ching, T. T. SAMS-1 coordinates HLH-30/TFEB and PHA-4/FOXA activities through histone methylation to mediate dietary restriction-induced autophagy and longevity. Autophagy 19, 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2068267 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Gaur, U., Cao, Z., Hou, S. T. & Zheng, W. Dopamine D1- and D2-like receptors oppositely regulate lifespan via a dietary restriction mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Biol. 20, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-022-01272-9 (2022).

Sericulture Institute, C. A. O. A. S. J. U. o. S. A. T. The Sericultural Science in China. 1125 (Shanghai Scientific & Technical, (2020). (In chinese).

Borchers, A. & Pieler, T. Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs. Genes (Basel). 1, 413–426. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes1030413 (2010).

Mitsumasu, K., Azuma, M., Niimi, T., Yamashita, O. & Yaginuma, T. Changes in the expression of soluble and integral-membrane trehalases in the midgut during metamorphosis in Bombyx mori. Zoolog Sci. 25, 693–698. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.25.693 (2008).

Anjiang Tan, G. F. et al. Transgene-based, female-specific lethality system for genetic sexing of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. PNAS 110, 6766–6770. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1221700110 (2013).

Qihao, H. U. et al. The expression characteristics of Fox transcription factor in the testes and the function of BmFoxL2 in the development of testes in silkworm. J. Environ. Entomol. 44, 146–152 (2022). (In chinese).

Singh, P., Mishra, G. & Omkar Are the effects of hunger stage-specific? A case study in an aphidophagous Ladybird beetle. Bull. Entomol. Res. 111, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485320000309 (2021).

Zajitschek, F. et al. Evolution under dietary restriction decouples survival from fecundity in Drosophila melanogaster females. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 1542–1548. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly070 (2019).

Zajitschek, F. Z., Canton, S. R., Georgolopoulos, C., Friberg, G. & Maklakov, U. Evolution under dietary restriction increases male reproductive performance without survival cost. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283, 20152726. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.2726 (2016).

Huang, Z. Y. et al. Evolution under dietary restriction increases reproduction at the cost of decreased somatic growth. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 78, 1135–1142. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glad102 (2023).

Short, C. A. & Hahn, D. A. Fat enough for the winter? Does nutritional status affect diapause? J. Insect Physiol. 145, 104488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2023.104488 (2023).

Low Temperature Biology of Insects. (Cambridge University Press, (2010).

Sinclair, B. J. & Marshall, K. E. The many roles of fats in overwintering insects. J. Exp. Biol. 221 https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.161836 (2018).

Sarah, J. et al. Christopher Hine, Filomena Broeskamp, Lukas Haberin,,,, Donald K. Ingram, Michel Bernier, and Rafael de Cabo. Effects of Sex, Strain, and Energy Intake on Hallmarks of Aging in Mice. Cell Metab 23, 1093–1112, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.027

Liao, C. Y., Rikke, B. A., Johnson, T. E., Diaz, V. & Nelson, J. F. Genetic variation in the murine lifespan response to dietary restriction: from life extension to life shortening. Aging Cell. 9, 92–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00533.x (2010).

Liu, Y. N., Chen, R. M., Pu, Q. T., Nneji, L. M. & Sun, Y. B. Expression plasticity of transposable elements is highly associated with organismal Re-adaptation to ancestral environments. Genome Biol. Evol. 14 https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evac084 (2022).

Fitz-James, M. H. & Cavalli, G. Molecular mechanisms of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-021-00438-5 (2022).

Oded Rechavi, L. H. Z., Anava, S., Hannon, J. & Hobert, O. e.,Wee Siong Sho Goh, Sze Yen Kerk,Gregoryand Starvation-induced transgenerational inheritance of small RNAs in C. elegans. Cell 158, 277–287, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.020

Cahenzli, F. & Erhardt, A. Transgenerational acclimatization in an herbivore-host plant relationship. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280, 20122856. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2856 (2013).

Greer, E. L. et al. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 479, 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10572 (2011).

Sano, H. Inheritance of acquired traits in plants: Reinstatement of Lamarck. Plant. Signal. Behav. 5, 346–348. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.5.4.10803 (2010).

Goldberg, A. D., Allis, C. D. & Bernstein, E. Epigenetics: A landscape takes shape. Cell 128, 635–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006 (2007).

Paganoni, S. & Schwarzschild, M. A. Urate as a marker of risk and progression of neurodegenerative disease. Neurotherapeutics: J. Am. Soc. Experimental Neurother. 14, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0497-4 (2017).

Schembri Wismayer, D. et al. Effects of acute changes in fasting glucose and free fatty acid concentrations on indices of β-cell function and glucose metabolism in subjects without diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 325, E119–e131. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00043.2023 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Integrating transcriptomics and free fatty acid profiling analysis reveal Cu induces shortened lifespan and increased fat accumulation and oxidative damage in C. elegans. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022 (5297342). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5297342 (2022).

George, J. & Struthers, A. D. The role of urate and Xanthine oxidase inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Ther. 26, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-3466.2007.00029.x (2008).

Tellis, M. B., Kotkar, H. M. & Joshi, R. S. Regulation of Trehalose metabolism in insects: from genes to the metabolite window. Glycobiology 33, 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwad011 (2023).

Assoni, G. et al. .Arosio, D. Trehalose-based neuroprotective autophagy inducers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 40, 127929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.127929 (2021).

Xiao, Q. H., He, Z., Wu, R. W. & Zhu, D. H. Physiological and biochemical differences in diapause and non-diapause pupae of sericinus Montelus (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Frontiers Physiology Nov. 2:13, 1031654. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.1031654 (2022).

Li, Y. N., Liu, Y. B., Xie, X. Q., Zhang, J. N. & Li, W. L. The modulation of Trehalose metabolism by 20-Hydroxyecdysone in Antheraea pernyi (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) during its diapause termination and Post-Termination period. J. Insect Sci. 1:20 (5), 18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieaa108 (2020).

Hutfilz, C. Endocrine regulation of lifespan in insect diapause. Front. Physiol. 13, 825057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.825057 (2022).

Guo, S. et al. Steroid hormone ecdysone deficiency stimulates Preparation for photoperiodic reproductive diapause. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009352 (2021).

Jiang, X., Huang, S. & Luo, L. Juvenile hormone changes associated with diapause induction, maintenance, and termination in the beet webworm, Loxostege sticticalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 77, 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.20429 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32072791) to X.S., the earmarked fund for CARS-Sericulture (CARS-18-ZJ0107) to Y.Z.. M.W. and X.S. designed the research project. S.X. conducted most of the experiments. M.W., X.M., J.W. and S.Z. conducted some of the experiments. M.W. and S.X. prepared the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. and X.S. designed the research project. S.X. conducted most of the experiments. M.W.,X.M., J.W. and S.Z. conducted some of the experiments. M.W. and S.X. prepared the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure

The authors declear that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, S., Wang, M., Mo, X. et al. Moderate dietary restriction across generations promotes sustained health and extends lifespan by enhancing antioxidant capacity in Bombyx mori. Sci Rep 15, 17533 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02528-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02528-4