Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the root and root canal morphology of maxillary first premolars (M1Ps) globally using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), comparing results with Vertucci’s and Ahmed et al.‘s classification systems. CBCT images were obtained for various purposes such as orthodontic treatment planning, tooth impaction, implant surgery, and trauma cases. M1Ps were evaluated in three planes to determine root and root canal morphology, and root bifurcation levels were assessed using integrated software. Prevalence variations between countries and overall prevalence were analyzed using meta-analysis software. A total of 6,600 patients (13,200 bilateral M1Ps) were examined. According to Vertucci’s classification, Type IV (59%), Type II (12%), Type I (9%), and Type III (8%) were the most common configurations. Based on Ahmed’s classification,2MP B1 P1 was the most prevalent configuration (53%), followed by 1MP1 (9%),1MP1–2–1 (8%), and 1MP2−1-1 (7%). The prevalence of 2MP B1 P1 by gender revealed a pooled prevalence of 58% in males and 50% in females. No significant difference was found across age ranges (p > 0.05). Ahmed’s classification system provided a more comprehensive analysis by successfully classifying all cases, whereas Vertucci’s system failed to categorize 1.8–2.7% of the cases. Significant bilateral symmetry in root morphology was noted. There are regional and gender-specific differences in the root canal morphology of M1Ps. Ahmed et al.‘s classification system was more comprehensive, effectively categorizing all observed morphologies compared to Vertucci’s system, which had limitations and left some morphologies unclassified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The root and root canal morphology of maxillary premolars has been a subject of significant interest and extensive research in endodontics1 They frequently exhibit complex anatomical differences that pose difficulties in diagnosis and treatment2 The maxillary first premolar (M1P) typically has two roots (buccal and palatal), while the second premolar generally has a single root. However, variations occur, such as three roots in the first premolar or additional canals in the second premolar3 The canal systems can be complex; M1Ps often have two canals (buccal and palatal), but the buccal canal can split, leading to three canals4 A precise understanding of the internal structure of these teeth is therefore essential for achieving successful endodontic treatment, reducing treatment failures, and enhancing prognostic outcomes5.

Vertucci introduced a widely used classification system in 1984, categorizing root canal systems into eight types, from simple single canals to more complex systems6 Despite its simplicity and clarity, Vertucci’s classification has limitations in accounting for all anatomical variations. More recently, Ahmed et al. introduced a more comprehensive classification system in 2017 to overcome certain limitations of Vertucci’s method. This system provides information on the number of roots, the presence of additional canals, and the complexities of canal interconnections. This recent classification system offers a comprehensive framework that accommodates the extensive anatomical heterogeneity observed in clinical practice7.

Conventional radiography techniques, although beneficial, frequently fall short of capturing the complexity of the root canal system due to their limitations in providing a two-dimensional representation8 The introduction of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has greatly improved the capacity to observe and evaluate dental structures in three dimensions, providing unmatched precision and detail9 Its application in research has facilitated a more accurate and comprehensive assessment of root canal morphology, paving the way for studies like the one proposed in this paper.

Studies have shown that population-specific anatomical characteristics can influence the prevalence of specific root canal configurations10 Such variations underscore the necessity of conducting multicenter cross-sectional studies to capture a broad and representative understanding of root canal morphology across different demographics. Although a recent multinational study11 focused on investigating the root canal morphology of M1Ps on a global scale, its evaluation was limited to the use of Vertucci’s classification. The primary objective of the present study is to globally assess the root and root canal morphology of M1Ps using CBCT and to compare the findings across two classification systems—Vertucci’s and Ahmed et al.’s. This comparative analysis aims to reveal the strengths and limitations of each system in describing the anatomical complexity of M1Ps. Furthermore, this study seeks to identify potential geographic and ethnic variations in root canal morphology, contributing to a comprehensive global understanding of endodontic anatomy.

Materials and methods

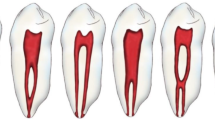

This multinational cross-sectional study, conducted from June 2023 to April 2024, received ethical approval from Necmettin Erbakan University’s ethical committee (protocol number:2023/286). Each researcher adhered to their country’s ethical requirements and obtained individual approvals. A comprehensive analysis of the root and canal morphology of permanent maxillary first premolars was conducted using Vertucci’s and Ahmed’s classification systems12 (Fig. 1). This study, carried out by a multidisciplinary team of Endodontics and Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology experts from diverse regions, followed guidelines from the American Society of Endodontists and Oral and Maxillofacial Radiologists13 Additionally, the study design and reporting were conducted in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines to ensure methodological transparency and completeness (Supplemental Table 1).

Power analysis

The formula \(n=\frac{{{Z^2}P(1 - P)}}{{{d^2}}}\) was employed for determining the required sample size. Based on a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), 5% precision, and 50% expected prevalence (which was adjusted to maximum due to its unpredictability), a minimum of 384 teeth (equivalent to 192 CBCT images) was deemed necessary for inclusion from each country.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included CBCT images that were acquired for a variety of purposes, such as treatment planning for orthodontic therapy, tooth impaction, implant surgery, or trauma cases. The images were accompanied by demographic data, including information about the gender and age of the individuals. Scans that included fully-formed teeth were specifically chosen for the study. Only CBCT images of high quality that provided coverage of the bilateral maxillary first premolars, allowing visualization of individual roots, canals, as well as the entire pulp chamber and apex, were included in the analysis.

The following factors were excluded: teeth that had undergone previous endodontic treatment, teeth where the entire pulp chamber to the apex couldn’t be visualized, immature teeth with open apex, teeth with large metal restorations or crowns/bridges/implants that obscured the anatomy, teeth with metal- or fiber-posts, evidence of previous apicectomy or apical/periodontal surgery altering the original tooth anatomy, extensive resorption leading to alterations in root number or canal configuration, calcification, scatter impeding proper visualization, and unilaterally or bilaterally missing M1Ps.

Study population

A total of 13,200 maxillary first premolars from 22 countries were included in this study (Table 1). The data were derived from CBCT images collected across six continents, ensuring a geographically diverse representation. Participating countries included Europe (Germany, Poland, Spain, Portugal, Croatia, Greece), Asia (Turkey, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, India, Singapore, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria), Africa (Egypt, South Africa, Libya), South America (Colombia, Ecuador), North America (United States), and Oceania (Australia). Demographic information, such as the age and gender of the individuals, was also collected alongside the CBCT images.

Calibration, intra- and inter- reliability

To ensure consistency across all participating researchers, a structured calibration process was implemented prior to data collection. The CBCT methodology followed Fernandes, et al.14, and the classification systems adhered to Ahmed, et al.12. Two researchers (G.D.B and G.M) developed standardized training materials, including multiple video tutorials. One example of these training videos is publicly accessible at [https://youtu.be/JBlQ40xpVgo?si=GJJKi8vZHns8oTK2].

After this initial training, researchers from each country analyzed 20 identical CBCT datasets (40 teeth per examiner, total = 800 teeth), with 10 cases deliberately selected for their complexity to assess classification accuracy in challenging cases. Intra- and inter-reliability were tested using Kappa and Fleiss’ Kappa tests.

If any researcher demonstrated low agreement levels, additional training was provided, followed by a second evaluation to ensure consistency. A final re-evaluation was conducted after four weeks to verify intra-reliability. All collected data were centralized, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus among senior examiners to maintain standardization across all countries.

Analysis of scans

CBCT scans of M1Ps were evaluated in coronal, sagittal, and axial planes to discern root and canal morphology. Expert examiners in each country adjusted visualization settings and used tools like noise reduction and filters to enhance image quality. The root bifurcation level was determined using a CBCT software ruler, dividing it into three parts: coronal (cementum-enamel junction to one-third of root length), central (one-third to two-thirds of root length), and apical (two-thirds to apex).

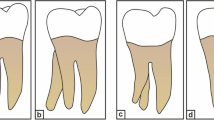

In classifying the number of roots, a tooth with a distinct single root (including a bifid root apex tip, which was considered single-rooted) is categorized as a single-rooted tooth. Regardless of partial or complete root separation, a tooth with bifurcated roots was classified as double-rooted. A double-rooted M1Ps with a deep buccal developmental groove in the buccal root (without obvious root separation) was also considered double-rooted. Furthermore, regardless of partial or complete separation, a tooth with three roots was categorized as a three-rooted tooth.

In order to evaluate the level of root canal divergence and merging, CBCT scans were analyzed in three sections using the software ruler: coronal, middle, and apical. The coronal section spanned from the cemento-enamel junction to one-third of the root length, the middle section spanned from one-third to two-thirds of the root length, and the apical section spanned from two-thirds of the root length to the radiographic apex. This method was used for assessment based on a previous publication15.

The data collected from various countries was aggregated into a unified spreadsheet to streamline the process of verifying discrepancies, which was done by the study coordinator. Subsequently, this data was exported to statistical software for analysis. Additionally, a visual representation of the CBCT examinations is depicted in Fig. 1. Furthermore, Table 1 furnishes comprehensive details about the exposure parameters and the source of the devices utilized in each country.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Jamovi Software (Version 2.3.21) and RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration). Each participating country independently analyzed its CBCT data according to a strictly standardized protocol to ensure consistency across centers. The individual prevalence results from each country were subsequently synthesized using meta-analytical techniques.

Given the multinational and multicenter nature of the study, substantial heterogeneity across datasets was anticipated. This heterogeneity stemmed not only from statistical variance but also from clinical and methodological diversity—such as differences in CBCT devices, voxel sizes, imaging protocols, and population characteristics. Additionally, despite implementing a calibration process to enhance inter- and intra-observer reliability, observer-related variability could not be completely eliminated.

To accommodate both measured and unmeasured sources of variation and to provide a generalizable pooled prevalence estimate, a random-effects meta-analysis was performed using the DerSimonian and Laird method. In this model, fixed effects correspond to the root canal configuration types (as defined by Vertucci and Ahmed classifications), which are consistent variables across all datasets. In contrast, random effects represent the different study populations (i.e., country-level datasets), reflecting the assumption that the true prevalence of root canal configurations may vary between populations due to factors not captured in the model.

Importantly, the choice of a random-effects model was not solely based on the presence of statistical heterogeneity (quantified via the I2 statistic), but also on the clinical and methodological heterogeneity inherently present in a large-scale, multicenter study. This modeling approach enables a more conservative and realistic estimation of the pooled prevalence.

Subgroup analyses were performed to further explore potential sources of heterogeneity. These included comparisons across geographic regions, gender, age groups, and voxel size categories (≤ 150 μm vs. >150 μm). The standard error (SE) of prevalence estimates for each country was calculated using the epidemiological formula √(p(1–p)/n), where “p” represents the observed prevalence and “n” the sample size.

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Higgins I2 statistic, with I2 values exceeding 50% considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity. Forest plots were used to visually display prevalence estimates along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), facilitating comparison between individual country-level findings and the overall pooled prevalence.

Results

A total of 6,600 CBCT images (300 per country) were analyzed, evaluating 13,200 maxillary premolar teeth. Of these, 55.7% were female and 44.3% male, with a median age of 34 years (Supplemental Table 2). Inter-observer agreement was substantial for both Vertucci (κ = 0.71) and Ahmed classifications (κ = 0.61), and intra-reliability showed almost perfect or substantial agreement (k > 0.73).

Type IV and 2MP B1 P1 according to the Vertucci and Ahmed classifications, respectively, were found to be the most common root canal morphologies in both right (V:60.3%, A:54.6%) and left (V:56.8%, A:51.6%) M1Ps. The study revealed that while there are 12 different types in the expanded Vertucci classification system, a small percentage of the upper right (1.8%) and left (2.7%) premolar teeth could not be classified using this system. Notably, none of the cases was found to be unclassified using the Ahmed classification system, which encompasses 40 different types (Table 2).

The prevalences of Vertucci Type I and 1MP1 displayed notable variation across regions, with an overall pooled prevalence of 9% (95% CI: 0.07–0.11) and high heterogeneity (I2 = 97.7%) (Fig. 2a). Africa had a pooled prevalence of 6% (95% CI: -0.01–0.13), but in Asia, the pooled prevalence was also 7% (95% CI: 0.04–0.09). Australia reported a prevalence of 17% (95% CI: 0.14–0.20), whereas Europe demonstrated a lower pooled prevalence of 6% (95% CI: 0.04–0.09). North America reported a prevalence of 9% (95% CI: 0.06–0.11). South America displayed significantly higher values, with a pooled prevalence of 29% (95% CI: 0.26–0.31), primarily due to higher rates observed in Colombia and Ecuador (Supplemental Fig. 1).

(A) Distribution and prevalence rates of a root canal configuration of Vertucci Type I and 1MP1 across countries and continents, with shades representing prevalence ranges. The forest plot depicts the prevalence by continent with confidence intervals. (B) Geographic distribution and prevalence rates for Vertucci Type II (1MP2 − 1−1 and 1MP2−2−1), showing a similar breakdown as panel A, with specific country and continental data alongside a forest plot of overall prevalence rates. The maps were created using MapChart (https://www.mapchart.net/).

The prevalence of Vertucci Type II (1MP2−1−1 and 1MP2−2−1) displayed notable variation across regions, with an overall pooled prevalence of 12% (95% CI: 0.09–0.14) and high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) (Fig. 2b). Africa had a pooled prevalence of 9% (95% CI: 0.04–0.15), while Asia reported a similar prevalence of 10% (95% CI: 0.05–0.14). Australia demonstrated a prevalence of 14% (95% CI: 0.11–0.17). In Europe, the pooled prevalence was 13% (95% CI: 0.07–0.19), with considerable variation among countries. North America reported the highest prevalence at 16% (95% CI: 0.13–0.19). In South America, the pooled prevalence was 14% (95% CI: 0.06–0.21), with Colombia and Ecuador showing high values (Supplemental Fig. 2).

The prevalences of Vertucci Type III and 1MP1–2−1 were found to be globally variable, with a total pooled prevalence of 8% (95% CI: 0.06–0.09) and substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 98%) (Fig. 3a). In Africa, the pooled prevalence was 4% (95% CI: 0.01–0.07), but Asia exhibited a higher pooled prevalence of 12% (95% CI: 0.06–0.18). Australia showed a prevalence of 11% (95% CI: 0.09–0.14), while Europe displayed a pooled prevalence of 3% (95% CI: 0.02–0.05). North America had a prevalence of 4% (95% CI: 0.03–0.06), and South America exhibited a broader range, with a pooled prevalence of 13% (95% CI: -0.09–0.35), driven by relatively high rates in Ecuador (24% (95% CI: 0.21–0.28)) compared to Colombia (2% (95% CI: 0.01–0.03)) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

(A) Distribution of configuration Vertucci Type III and 1MP1–2−1 prevalence by country, with shading to indicate prevalence percentage ranges. The associated forest plot shows overall prevalence by continent. (B) Prevalence rates of Vertucci Type IV 2MP B1P1 and 1MP2 by region, with a comparable layout to panel (A), including country-level data and a forest plot indicating distribution across continents. The maps were created using MapChart (https://www.mapchart.net/).

The prevalence of Vertucci Type IV2MP B1 P1 and 1MP2 exhibited substantial regional variation, with an overall pooled prevalence of 59% (95% CI: 0.51–0.67) and high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%) (Fig. 3b). Africa had a pooled prevalence of 66% (95% CI: 0.54–0.78), while Asia showed a prevalence of 56% (95% CI: 0.44–0.69). Australia demonstrated a lower prevalence of 38% (95% CI: 0.34–0.41). Europe had a high pooled prevalence of 69% (95% CI: 0.57–0.81), with considerable variation among countries. North America reported a prevalence of 52% (95% CI: 0.48–0.55). South America exhibited the lowest pooled prevalence at 36% (95% CI: 0.18–0.54), with Colombia and Ecuador contributing to this variation (Supplemental Fig. 4).

The prevalence of2MP B1 L1, as shown in Fig. 4a, varies significantly across different regions, with a total pooled prevalence of 53% (95% CI: 0.45–0.61) and substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89.4%). Africa exhibited a pooled prevalence of 57% (95% CI: 0.49–0.65), but Asia demonstrated a slightly lower pooled prevalence of 54% (95% CI: 0.41–0.66). In contrast, Australia reported a lower prevalence at 38% (95% CI: 0.34–0.41). Europe had considerable variability, with a pooled prevalence of 60% (95% CI: 0.46–0.74), ranging from 39% (95% CI: 0.35–0.42) in Spain to 89% (95% CI: 0.86–0.91) in Croatia. North America showed a prevalence of 52% (95% CI: 0.48–0.55), while South America reported the lowest pooled prevalence at 29% (95% CI: 0.19–0.40) (Supplemental Fig. 5).

(A) Distribution of configuration 2MP B1P1 prevalence by country, with shading to indicate prevalence percentage ranges. The associated forest plot shows overall prevalence by continent. (B) Prevalence rates of 1MP2−1−1 by region, with a comparable layout to panel A, including country-level data and a forest plot indicating distribution across continents. The maps were created using MapChart (https://www.mapchart.net/).

The prevalence of 1MP2−1−1 shows notable variability across regions, with a total pooled prevalence of 7% and high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) (Fig. 4b). In Africa, the pooled prevalence was 9% (95% CI: 0.04–0.15), with Egypt at 5% (95% CI: 0.03–0.07) and South Africa at 8% (95% CI: 0.06–0.10), reflecting moderate diversity within the region. Asia had a pooled prevalence of 5% (95% CI: 0.03–0.07). Australia reported a prevalence of 14% (95% CI: 0.11–0.17), while Europe displayed a pooled prevalence of 8% (95% CI: 0.04–0.11), with higher values observed in Germany (23% (95% CI: 0.19–0.26)) and lower rates in Croatia (2% (95% CI: 0.01–0.03)). North America showed a prevalence of 16% (95% CI: 0.13–0.19) and South America exhibited a pooled prevalence of 6% (95% CI: -0.03–0.14) (Supplemental Fig. 6). Detailed analyses of the most common ten root configurations were presented in Supplemental Tables 3–4.

The prevalence of 2MP B1 P1 by gender shows that males have a pooled prevalence of 58% (95% CI: 0.50–0.65), while females have a slightly lower pooled prevalence of 50% (95% CI: 0.42–0.58) (Fig. 5a, Supplemental Fig. 7). For individuals under 40 years, prevalence is stable at 54–55%, then levels at 54% for ages 40–50. It declines to 50% for ages 50–60 and 49% for those over 60. The overall pooled prevalence is 53% (95% CI: 0.49–0.56) (Fig. 5b, Supplemental Fig. 8).

(A) Comparison of prevalence for 2MP B1L1 by gender. (B) Prevalence comparison for the same configuration across different age ranges. (C) Gender-based comparison of single root prevalence, emphasizing male and female distributions. (D) Geographic comparison of single root prevalence by continent, showing regional differences with prevalence rates and confidence intervals.

The prevalence of single root conditions was 38% (95% CI: 0.31–0.46) in males and 43% (95% CI: 0.37–0.49) in females, indicating a slightly higher, but not significant, prevalence in females (p > 0.05) (Fig. 5c, Supplemental Fig. 9, Table 3). Regionally, the prevalence varied: Africa had 39% (95% CI: 0.31–0.47), Asia 43% (95% CI: 0.31–0.54), Australia 60% (95% CI: 0.56–0.64), Europe 38% (95% CI: 0.24–0.52), North America 37% (95% CI: 0.33–0.41), and South America 69% (95% CI: 0.58–0.80), with particularly high values observed in Colombia and Ecuador, which contributed significantly to the overall prevalence in South America (Fig. 5d, Supplemental Fig. 10, Table 3).

The similarity between the left and right sides was 75.5% for Ahmed and 79.2% for Vertucci classifications, with strong associations (Cramer’s V > 0.53) (Supplemental Table 5). Root bifurcation was most commonly found in the middle region at approximately 46% while merging was most prevalent in the coronal (37.1%) and middle (27–31%) regions (Table 4).

The subgroup analysis evaluated the effect of voxel size on the prevalence of the most common configurations, specifically Vertucci Type I, II, III, IV, 2MP B1P1, and 1MP2−1−1. Despite high heterogeneity across all meta-analyses, no significant difference was found between the ≤ 150 and > 150 voxel size subgroups (P > 0.05) (Supplemental Figs. 11–16).

Discussion

This study provides a detailed global assessment of M1P root and canal morphology, offering insights into anatomical variations across 22 countries. The findings highlight significant variability in root and canal configurations. While most M1Ps had two roots and two canals, consistent with previous studies16, variations such as three roots or additional canals further underscore their complexity. Geographical differences were also noted, with three-rooted premolars more common in Asian populations compared to European and American groups10, suggesting ethnic and genetic influences on dental anatomy17,18,19.

The most common root canal morphologies for M1Ps were Type IV according to Vertucci’s classification and 2MP B1 P1 according to Ahmed’s classification. Type IV was found in 60.3% of right and 56.8% of left premolars, while 2MP B1 P1 was noted in 54.6% of right and 51.6% of left premolars, consistent with previous studies20,21 This pattern highlights a predominant root canal configuration. The present study also revealed differences in the coverage and comprehensiveness of the two classification systems. The modified/expanded Vertucci classification, which included 12 types, could not categorize a small percentage of premolars (1.8% right, 2.7% left), indicating its limitations in accounting for all anatomical variations22,23 However, the classification system proposed by Ahmed et al. in 2017, comprising 40 types, successfully classified all examined cases, demonstrating greater detail and inclusivity compared to other systems24,25 This comprehensive coverage is beneficial in clinical settings where precise anatomical identification is crucial26.

This study found significant regional variations in the four most common root canal morphologies. South America had a notably higher prevalence of the 1MP1 configuration (27%) compared to other continents, aligning with previous studies27 This may be due to environmental, evolutionary, or genetic factors unique to South American populations. The study also revealed distinct prevalence patterns in different countries: 1MP1–2−1 was most prevalent in Ecuador (24%), while 1MP1–2−2 was common in Jordan (17%), Yemen (17%), and Australia (18%). Germany had a higher prevalence of 1MP2−1−1 (21%), and Syria showed a higher frequency of 1MP2−1−2 (8%). These findings highlight the importance of recognizing regional differences in dental anatomy for clinical practice. Additionally, significant intercontinental and regional differences were observed in the prevalence of the ten most common root canal morphologies in upper left M1Ps. Variations were noted in the seven most frequent morphologies across continents, except for 1MP2−1−2, 1MP2−2−1, and 1MP2. For instance, the1MP1 morphology was considerably more prevalent in South America (30%) compared to other continents. Similar migration routes from Asia might explain the resemblance in single-rooted configurations between the Americas, Oceania, and Asia28.

The study also found significant differences in the prevalence of the 2MP B1 P1 and 2MP B2 − 1 P1 morphologies. The 2MP B1 P1 Type was observed less frequently in South America (30%), particularly in Ecuador (23%), highlighting regional variations that could influence endodontic treatment strategies. In contrast, the 2MP B2 − 1 P1 Type was more commonly seen in Asian countries (5%), especially in Uzbekistan (8%) and Kazakhstan (8%). These findings are parallel with studies among Asian countries.29,30,31 3MP MB1 DB1 P1 morphology was more frequently observed in the USA (7%), which aligns with studies showing varied root canal configurations in North American populations32.

The study revealed relatively gender differences in the prevalence of the 2MP B1 P1 morphology in M1P teeth, with males showing a higher prevalence than females. This aligns with previous research suggesting that males often have more complex root canal systems due to differences in tooth size, root development, and hormonal influences5,33,34 These findings highlight the need to consider gender-specific anatomical characteristics in endodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Contrary to some studies reporting age-related changes in root canal morphology due to secondary dentin deposition and pulp chamber calcification35,36,37,38, this study found no significant differences across age groups. The lack of age-related differences could be due to the narrow age range of participants or the specific morphology examined, which may be less affected by age-related changes.

The study found significant bilateral symmetry in dental anatomy, consistent with previous research39,40 Similar patterns of root canal configurations on both sides of the maxillary arch were demonstrated by Diab, et al.41 and Allawi, et al.42, which have been attributed to mirrored developmental processes. Recognizing this symmetry is crucial for endodontic diagnosis and treatment planning, as it can help predict the canal morphology of the contralateral tooth and simplify procedures43.

The study found significant geographic variations in the prevalence of double and triple roots in maxillary premolars. Croatia exhibited the highest prevalence of double roots (88–89%), while Ecuador showed the lowest (24–25%). The higher prevalence of double roots in males and certain regions like Croatia suggests that endodontists should be particularly vigilant when treating these populations to ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid complications from missed or incomplete root canal treatments. These variations may be influenced by genetic, environmental, and dietary factors, as well as differences in dental care practices, access to healthcare, and socioeconomic status44,45.

Canal bifurcation presents a significant challenge, especially in the middle and apical sections of the root15,46 This study found that bifurcation most commonly occurs in the middle third of the root, with an incidence of approximately 46%, consistent with previous research21,47 Ahmed, et al.46 noted the complexity of canal configurations in this region, complicating endodontic procedures. Clinicians should meticulously trace the lamina dura and periodontal ligament space on periapical radiographs with a mesial/distal shift or use CBCT if necessary to determine bifurcation levels accurately48,49 This is crucial for complete cleaning and shaping during root canal treatment. In addition, merging of root canals was most prevalent in the coronal (37.1%) and middle (27–31%) regions. This contrasts with previous studies indicating that merging frequently occurs in the middle third, forming a single canal extending toward the apex15 These findings underscore the importance of thorough radiographic assessment and careful instrumentation to address the anatomical variability and ensure successful endodontic treatment.

Despite its advanced capabilities, CBCT imaging may miss minute anatomical details due to resolution limits. The large sample size might not fully represent all populations, especially those underrepresented. Observer interpretation variations could introduce subjectivity in classifying root canal morphologies. The cross-sectional design also limits the ability to observe changes over time or to establish causal relationships. Additionally, potential confounding factors such as dental restorations or previous treatments were not accounted for. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs, include more diverse populations, and utilize higher-resolution imaging to address these limitations.

While the Ahmed classification system demonstrated superior comprehensiveness and inclusivity compared to Vertucci’s system, it is not without limitations. First, its complexity—featuring 40 different configurations—may pose challenges for clinical practitioners and researchers, who may find it less practical for routine use. Furthermore, although our study demonstrated high inter- and intra-observer reliability, the intricate nature of the classification system may still lead to variability in interpretation, particularly among less experienced examiners. Finally, despite its inclusiveness, certain rare or region-specific morphologies might not be fully encompassed within the system, highlighting the need for potential updates to address global anatomical variations comprehensively.

In addition to the limitations of the classification system, the study’s multinational cross-sectional design also presents challenges that should be acknowledged. While this approach provides valuable insights by capturing a diverse range of populations and regional variations, variations in imaging protocols, observer expertise, and equipment across different countries—despite rigorous standardization efforts—may introduce potential biases or inconsistencies in data collection and analysis. Logistical challenges, such as ensuring uniform adherence to study protocols and addressing ethical and administrative requirements across multiple countries, may further impact the study’s efficiency. Finally, the inclusion of diverse populations increases the likelihood of heterogeneity, which, while offering a broader perspective, complicates the pooling of data for meta-analyses and reduces the precision of pooled estimates.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this multinational study, root and canal morphology of M1Ps revealed significant anatomical variations across diverse populations. Notable findings include higher prevalence of double roots in Croatia, three-rooted premolars in the USA, and gender-specific differences with males exhibiting a greater frequency of double roots. These insights underscore the importance of considering demographic factors in endodontic diagnostics and treatment planning, particularly in globally diverse patient populations.

Our study specifically evaluated the effectiveness of two root canal classification systems—Vertucci’s and Ahmed et al.’s. The Ahmed classification, comprising 40 distinct canal configurations, was found to be more comprehensive, as it successfully classified all observed anatomical morphologies. In contrast, the expanded Vertucci classification (12 configurations) was unable to categorize approximately 2% of the analyzed cases, leaving these rare morphologies unclassified. Therefore, the Ahmed system demonstrated superior performance in addressing the anatomical complexity observed across global populations.

Although our findings support the use of Ahmed’s classification in complex anatomical cases, its extensive nature may pose practical challenges in routine clinical practice. Therefore, further studies are recommended to refine existing classification systems, enhance diagnostic accuracy through improved imaging methods, and develop tailored endodontic treatment strategies based on the detailed anatomical insights gained from global data.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available considering that we have not required consents to publish this data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Karobari, M. I. et al. Micro computed tomography (micro-CT) characterization of root and root Canal morphology of mandibular first premolars: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 24 (1), 1 (2024).

Aljawhar, A. M., Ibrahim, N., Abdul Aziz, A., Ahmed, H. M. A. & Azami, N. H. Characterization of the root and Canal anatomy of maxillary premolar teeth in an Iraqi subpopulation: a cone beam computed tomography study. Odontology 112 (2), 570–587 (2024).

Versiani, M. A., Pereira, M. R., Pécora, J. D. & Sousa-Neto, M. D. Root Canal anatomy of maxillary and mandibular teeth. In: (eds Versiani, M. A., Basrani, B. & Sousa-Neto, M. D.) The Root Canal Anatomy in Permanent Dentition. Berlin: Springer; 181–239. (2019).

Versiani, M. A. et al. Effects of root Canal enlargement on unprepared areas and coronal dentine thickness of three-rooted maxillary first premolars with different root configurations: a Stepwise micro-CT study. Int. Endod J. 55 (11), 1262–1273 (2022).

Karobari, M. I. et al. Exploring age and gender variations in root Canal morphology of maxillary premolars in a Saudi subpopulation: a cross-sectional CBCT study. BMC Oral Health. 24 (1), 1–10 (2024).

Vertucci, F. J. Root Canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 58 (5), 589–599 (1984).

Karobari, M. I. et al. Root and root Canal morphology classification systems. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 1–6 (2021).

Ng, Y. S. Comparison between conventional dental radiography and CBCT. In: (ed Ng, Y. S.) Cone Beam CT in Dentistry: an Atlas for Dentists and Medical Radiologists. Berlin: Springer; 271–330. (2023).

Boquete-Castro, A., Lopez, A. P., Martins, A. S., Lorenzo, A. S. & Perez, P. R. Applications and advantages of the use of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics: an updated literature review. Saudi Endod J. 12 (2), 168–174 (2022).

Martins, J. N., Gu, Y., Marques, D., Francisco, H. & Caramês, J. Differences in root and root Canal morphologies between Asian and white ethnic groups analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 44 (7), 1096–1104 (2018).

Martins, J. N. et al. Worldwide assessment of the root and root Canal characteristics of maxillary premolars: a multicenter cone-beam computed tomography cross-sectional study with meta-analysis. J. Endod. 50 (1), 31–54 (2024).

Ahmed, H., Versiani, M., De-Deus, G. & Dummer, P. A new system for classifying root and root Canal morphology. Int. Endod J. 50 (8), 761–770 (2017).

Fayad, M. I. et al. Use of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics: 2015 update. J. Endod. 41 (9), 1393–1396 (2015).

Fernandes, N. A., Herbst, D., Postma, T. C. & Bunn, B. K. The prevalence of second canals in the mesiobuccal root of maxillary molars: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Aust Endod J. 45 (1), 46–50 (2019).

Martins, J. N., Marques, D., Mata, A. & Caramês, J. Root and root Canal morphology of the permanent dentition in a Caucasian population: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Int. Endod J. 50 (11), 1013–1026 (2017).

Mirza, M. B. Evaluating the internal anatomy of maxillary premolars in an adult Saudi subpopulation using two classifications: a CBCT-based retrospective study. Med. Sci. Monit. 30, e943455 (2024).

Karunakaran, J. V. et al. Root form and morphology of human permanent maxillary first premolars of an Indo-Dravidian population based in Southern India: an in vitro study. J. Pharm. Bioall Sci. 12 (Suppl 1), 601–606 (2020).

Przesmycka, A. et al. Root and root Canal diversity in human permanent maxillary first premolars and upper/lower first molars from a 14th–17th and 18th–19th century Radom population. Arch. Oral Biol. 110, 104603 (2020).

Buchanan, G. D. et al. A study of mandibular premolar root and Canal morphology in a black South African population using cone-beam computed tomography and two classification systems. J. Oral Sci. 64 (4), 300–306 (2022).

Elkady, A. & Allouba, K. Cone-beam computed tomographic analysis of root and Canal morphology of maxillary premolars in a Saudi subpopulation. Egypt. Dent. J. 59, 3419 (2013).

Saber, S. E. D. M., Ahmed, M. H., Obeid, M. & Ahmed, H. M. A. Root and Canal morphology of maxillary premolar teeth in an Egyptian subpopulation using two classification systems: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Int. Endod J. 52 (3), 267–278 (2019).

Olczak, K., Pawlicka, H. & Szymański, W. Root form and Canal anatomy of maxillary first premolars: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Odontology 1–11. (2022).

Mağat, G., Uzun, S. & Buchanan, G. D. Evaluation of maxillary first molar Teeth’s mesiobuccal root and root Canal morphology using two classification systems among a Turkish population: a cone-beam computed tomography study. J. Endod Restor. Dent. 1 (1), 8–14 (2023).

Buchanan, G. D., Gamieldien, M. Y., Tredoux, S. & Vally, Z. I. Root and Canal configurations of maxillary premolars in a South African subpopulation using cone-beam computed tomography and two classification systems. J. Oral Sci. 62 (1), 93–97 (2020).

Taha, N. A., Makahleh, N. & Hatipoglu, F. P. Root Canal morphology of anterior permanent teeth in a Jordanian population using two classification systems: a cone-beam computed tomography study. BMC Oral Health. 24, 170 (2024).

Ahmed, H. et al. Application of a new system for classifying root Canal morphology in undergraduate teaching and clinical practice: a National survey in Malaysia. Int. Endod J. 53 (6), 871–879 (2020).

Martins, J. N., Marques, D., Francisco, H. & Caramês, J. Gender influence on the number of roots and root Canal system configuration in human permanent teeth of a Portuguese subpopulation. Quintessence Int. 49 (2), 103–111 (2018).

Hanihara, T. Geographic structure of dental variation in the major human populations of the world. Anthropol. Perspect. Tooth Morphol. Genet. Evol. Var. 66, 479 (2013).

Gupta, S. et al. Root and Canal morphology of maxillary first premolar teeth in a North Indian population using clearing technique: an in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 18 (3), 232–236 (2015).

Tian, Y. Y. et al. Root and Canal morphology of maxillary first premolars in a Chinese subpopulation evaluated using cone-beam computed tomography. Int. Endod J. 45 (11), 996–1003 (2012).

Peiris, R. Root and Canal morphology of human permanent teeth in a Sri Lankan and Japanese population. Anthropol. Sci. 116 (2), 123–133 (2008).

Cleghorn, B. M., Christie, W. H. & Dong, C. C. The root and root Canal morphology of the human mandibular first premolar: a literature review. J. Endod. 33 (5), 509–516 (2007).

Ok, E. et al. A cone-beam computed tomography study of root Canal morphology of maxillary and mandibular premolars in a Turkish population. Acta Odontol. Scand. 72 (8), 701–706 (2014).

de Lima, C. O., de Souza, L. C., Devito, K. L., do Prado, M. & Campos, C. N. Evaluation of root Canal morphology of maxillary premolars: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Aust Endod J. 45 (2), 196–201 (2019).

Martins, J. N., Ordinola-Zapata, R., Marques, D., Francisco, H. & Caramês, J. Differences in root Canal system configuration in human permanent teeth within different age groups. Int. Endod J. 51 (8), 931–941 (2018).

Karobari, M. I. et al. Assessment of root Canal morphology of maxillary premolars: a CBCT study exploring age and gender variations. Research Square [Preprint]. 19 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3449226/v1 (2023).

Li, J., Li, L. & Pan, Y. Anatomic study of the buccal root with furcation groove and associated root Canal shape in maxillary first premolars by using micro-computed tomography. J. Endod. 39 (2), 265–268 (2013).

Hatipoğlu, F. P. et al. Prediction of root Canal lengths and pulp volume of the maxillary permanent first molar based on stature, crown diameters, and facial morphometry. Anat. Sci. Int. 98, 454–462 (2023).

Li, Y. H. et al. Symmetry of root anatomy and root Canal morphology in maxillary premolars analyzed using cone-beam computed tomography. Arch. Oral Biol. 94, 84–92 (2018).

Felsypremila, G., Vinothkumar, T. S. & Kandaswamy, D. Anatomic symmetry of root and root Canal morphology of posterior teeth in Indian subpopulation using cone-beam computed tomography: a retrospective study. Eur. J. Dent. 9 (4), 500–507 (2015).

Diab, H. et al. A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) study of root anatomy, Canal morphology and bilateral symmetry of permanent maxillary premolar teeth among the Qatari subpopulation. Open Dent. J 16(1). (2022).

Allawi, S., Madarati, A. A. & Al-Tayyan, M. Evaluation of roots and root canals’ morphology of maxillary premolars in a Syrian subpopulation using cone-beam computed tomography. Saudi Endod J. 13 (2), 168–176 (2023).

Hatipoğlu, F. P. et al. Assessment of the prevalence of middle mesial Canal in mandibular first molar: a multinational cross-sectional study with meta-analysis. J. Endod. 49 (5), 549–558 (2023).

Kinaston, R. et al. The dentition: development, disturbances, disease, diet, and chemistry. In: (ed Ortner, D. J.) Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 749–797. (2019).

Ribeiro, D. et al. Intrauterine hormone effects on tooth dimensions. J. Dent. Res. 92 (5), 425–431 (2013).

Ahmed, H. M. A. & Cheung, G. S. P. Accessory roots and root canals in maxillary premolar teeth: a review of a critical endodontic challenge. Endod Pract. Today. 6 (1), 7–18 (2012).

Awawdeh, L., Abdullah, H. & Al-Qudah, A. Root form and Canal morphology of Jordanian maxillary first premolars. J. Endod. 34 (8), 956–961 (2008).

Lammertyn, P. A., Rodrigo, S. B., Brunotto, M. & Crosa, M. Furcation groove of maxillary first premolar, thickness, and dentin structures. J. Endod. 35 (6), 814–817 (2009).

Utar, M. & Sarıçam, E. Comparative analysis of push-out bond strength between prefabricated solid glass fiber post and bundled glass fiber-reinforced resin post. J. Endod Restor. Dent. 2, 27–31 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to commemorate Dr. Suha Alfirjani, who contributed significantly to this study by collecting theresearch data before her untimely passing. Dr. Alfirjani was a distinguished endodontist and a devoted educator.Her dedication, insight, and passion for endodontics are deeply embedded in this work and will continue toinspire those who follow in her path.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.P.H. designed the study. Ö.H. performed the data analysis and revised the draft. The manuscript was written by F.P.H. and M.I.K. G.D.B. and G.M. revised the final draft of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to data collection. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the relevant ethics committees in each participating country. Ethical approvals were obtained from the following institutions: Germany: Ethik-Kommission Westfalen-Lippe, Münster; Approval No. 2023-355-f-N. Uzbekistan: LECV; Approval No. 2023/04-1716. Croatia: Research Ethics Committee of Dental School University of Zagreb; Approval No. 05-PA-30-20-9/2023. United States: University of Mississippi Medical Center; Approval No. UMMC-IRB-2024-197. Spain: CEIMG; Approval No. 2023/293. Colombia: CIEIH-CES; Approval No. Ae1135/229. Kazakhstan: REC; Approval No. 2023/1634. Portugal: CEFMUC; Approval No. CE_006.2020. Singapore: SingHealth CIRB; Approval No. 2023/2407. Greece: Athens Dental Association; Approval No. 2152/29.11.2023. South Africa: Approval No. 375/2023. Turkey: N.E.Ü Faculty of Dentistry; Approval No. 2023/286. Each participating center obtained institutional ethical approval before the commencement of data collection. This study involved retrospective analysis of anonymized CBCT datasets, and no additional radiographic exposure was required beyond routine diagnostic procedures. All ethical regulations regarding patient data protection and privacy were strictly followed.

Consent for publication

For our multinational online survey, informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation. Consent was gathered electronically at the beginning of the survey, where participants were informed about the purpose of the study, their rights as participants, and the voluntary nature of their participation. By proceeding with the survey, participants explicitly indicated their consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pertek Hatipoğlu, F., Magat, G., Karobari, M.I. et al. Root and canal configurations of maxillary first premolars in 22 countries using two classification systems: a multinational cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 19290 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02669-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02669-6