Abstract

Wheat plays a vital role in Pakistan’s economy and food security, making accurate yield forecasting essential for planning and resource management. Traditional approaches—such as manual field surveys and remote sensing—have been widely used, but their effectiveness in capturing yield variation across different growth stages remains uncertain. This study explores a multi-phase approach to wheat yield prediction by dividing the crop cycle into four key stages and analyzing data from 2017 to 2022. Using the Google Earth Engine platform, the analysis integrates satellite imagery, seasonal weather variables, and soil information. A range of machine learning and deep learning models were tested to assess their predictive performance. The results show that combining diverse data sources with advanced AI techniques significantly improves prediction accuracy, with model performance reaching R2 values between 0.4 and 0.88. Among the tested models, those capable of capturing spatial and temporal patterns reduced prediction errors most effectively. These findings demonstrate the value of integrating environmental data and AI methods for enhancing crop yield forecasting across complex agricultural regions. This study presents a comparative analysis of AI-based approaches against conventional methods, demonstrating their superiority in three key areas: (1) improved computational efficiency through optimized learning architectures, (2) enhanced spatial generalizability by capturing complex, nonlinear patterns, and (3) greater prediction stability under varying conditions. Our findings underscore the transformative potential of AI models, offering a more reliable and scalable alternative for predictive tasks in our framework. This research offers a robust framework for forecasting wheat yields, aiding decision-makers in improving food security and agricultural planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheat is one of the most widely grown cereals in the twenty-first century1,2, contributing a disproportionate number of calories and protein to the world’s food supply. In the grain circulation market, preventing famine and food security, the accuracy of crop output predictions is vital by3. Predicting how much food a crop will yield can also aid fertilization efforts by4. Business, national food policy, and security planning all benefit from accurate predictions of crop yields. Reliable crop estimates enable the government to make informed decisions on imports and exports, contributing to a stable and sufficient national food supply. Countries like Pakistan, which are facing significant challenges due to population growth and the impact of climate change, find these estimations particularly important5. These forecasts drive GDP growth and serve as the primary contributor to trade surpluses, ensuring food supply in urban and rural areas. Recognizing its paramount importance, many planners and officials acknowledge the significance of timely and accurate agricultural data. Staple crops like wheat, rice, maize, sugarcane, and cotton are pivotal, prompting policymakers to continually seek the most up-to-date and precise information about their cultivation and output6. There are two harvest times in Pakistan. The first is pronounced "Kharif," and the second is "Rabi." Planting of Kharif takes place between April and June, while harvesting occurs from October through December. This season involves harvesting various cereals, pulses, and cereal grains. Conversely, “Rabi” crops such as tobacco, barley, rapeseed, wheat, gram, and mustard are cultivated from October to December and harvested afterward. Wheat is the primary staple food harvested during the “Rabi” season. Grain production contributes to a 1.7% increase in the agricultural sector’s value and the overall national economy. The wheat yield grew, rising from 24.349 million tons in 2017 to 24.946 million tons in 2018. This year, the cultivated area expanded to 8825 km2, compared to 8678 km2 in 2017. Increased output can be attributed to better crop health, more land, and higher yields1,7. Agricultural yield prediction has been the focus of many researchers for decades. Shanahan8, Fontana et al.9 leading to the development of process-oriented crop growth and empirical statistical models. Traditional statistical methods for yield prediction2,10,11. Rely on regression equations connecting weather variables (temperature, precipitation, etc.) with reported yields over many time and space scales. Since yield-regulating variables vary by location, crop variety, and growing season, the validity of the regression results was heavily questioned12. Because of their limited spatial generalizability, these models are cumbersome to apply to more expansive places. However, process-based crop models like the DSSAT13, APSIM14, MCWLA9,15, and WOFOST16 are used all over the world to simulate and predict yields. These models can more precisely predict crop yields. Still, they are time-consuming, expensive, and difficult to spread to a broader region or developing country due to their required inputs (such as meteorological conditions, fertilizers, irrigations, soil, and hydrological factors)12,17,18. Both of the above approaches rely heavily on favorable weather conditions. Vegetation growth state indicators such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and the enhanced vegetation index (EVI) may also be useful in yield prediction19,20. As remote sensing technology advances, these markers have become more widely available at finer temporal and spatial scales21. In several data mining and agricultural analytics tasks22,23, such as classifying crop types24,25 and forecasting crop yields26, machine learning methods have proven to be remarkably effective. Given its prowess in dealing with datasets with many dimensions12,22, crop output is affected by several factors that fluctuate over area and time. This suggests that yield prediction models benefit from applying machine learning techniques. Recent investigations27 from all around the world corroborate this hypothesis. However, the actual yield could not be determined until harvest28,29 because the factors were selected based on the growing season. Very little research has been done using temporal training parameters to predict Pakistan’s winter wheat output. Predicting future crop yields is considerably aided by identifying the best period to record winter wheat’s progress30. There have been scant large-scale data mining studies on predicting Pakistani wheat yields. Macroeconomic policymakers need a comprehensive framework or model for yield forecasting. Furthermore, more studies are required on variations in yield prediction accuracy between regions, as most recent studies have focused on the impact of climate change on yield31. While previous research has increased yield prediction accuracy from spatial and temporal domains, most of these studies have only focused on partial regions due to the complexity of the data process18,32. Predictions of agricultural output on a large scale necessitate a vast amount of data and data processing, which can be expensive. Regarding petabyte-scale data sets, Google Earth Engine (GEE) is a free cloud-based computing platform that stores and manages them33,34. We used the GEE platform to develop machine learning and deep learning models for forecasting winter wheat yield in Pakistan because of the limitations of earlier studies. Twenty variables were incorporated into our models, with inputs from weather, soil, vegetation, and management techniques. To predict winter wheat yield at the county level, we utilized a variety of machine learning and deep learning algorithms, including a support vector machine (SVM), a minor absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), a random forest (RF), a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

Contributions:

-

Develop a comprehensive framework for predicting winter wheat yields.

-

Evaluate and select the most effective machine learning and deep learning algorithms for accurate yield predictions.

-

A decision-support tool is supplied to help farmers and decision-makers anticipate agricultural yields based on climatic conditions in their zones, allowing them to resist climate change and secure future food safety successfully.

-

Investigate regional variations in yield prediction accuracy and assess the relative importance of variables across different geographic regions.

Integrating multiple AI models for wheat crop yield prediction in Pakistan can improve accuracy, robustness, and adaptability to varying climatic, soil, and economic conditions.

Different AI models can be integrated and compared based on their strengths:

-

(a)

Machine Learning Models

-

1.

Linear Regression (LR)—Baseline model for understanding yield trends.

-

2.

Random Forest (RF)—Handles non-linearity and feature importance well.

-

3.

Support Vector Machine (SVM)—Effective for small datasets with complex relationships.

-

4.

Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM)—Performs well on tabular data with feature interactions.

-

1.

-

(b)

Deep Learning Models

-

1.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)—Capture complex patterns in yield prediction.

-

2.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—For analyzing satellite images of crop growth.

-

3.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs, LSTMs, GRUs)—Useful for time-series climate and soil data.

-

1.

-

(c)

Hybrid and Ensemble Models

-

1.

Stacked Model (LR + RF + ANN)—Combines predictions from different models.

-

2.

CNN + LSTM—CNN for feature extraction from satellite images, LSTM for time-series yield trends.

-

1.

This study aims to integrate proximal sensing data from multi-site, multi-year field experiments along with publicly available weather data to evaluate machine learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms for predicting district level winter wheat yield. Feature selection plays a crucial role in reducing computational costs, enhancing predictive accuracy, and improving the interpretability of data and results. Additionally, selecting appropriate time aggregation intervals (e.g., weekly, monthly, or growing season) for dynamic features such as average temperature can help balance model complexity, mitigate overfitting risks, and ensure compatibility with alternative weather data sources. While artificial intelligence (AI) has shown promise in improving agricultural forecasting, many existing studies focus on limited data types, relying solely on either satellite imagery or historical climate data—without fully integrating multi-phase crop growth patterns or high-resolution environmental variables. Additionally, few have explored how model performance varies across distinct stages of crop development. This study addresses these gaps by segmenting the wheat growth cycle into four phases and combining meteorological, satellite, and soil data using advanced machine learning techniques. By doing so, it offers a more nuanced and accurate prediction model for wheat yield across Pakistan.

Accordingly, this study aims to address the following key questions: (1) Which ML & DL algorithm delivers the highest accuracy for district-level winter wheat yield prediction? (2) What are the most influential factors in the prediction process? (3) Which feature selection techniques and aggregation intervals yield the most informative feature subset?

Section “Related work” presents some of the most recent research in the Field of DL and ML crop yield prediction. The Material and methods are presented in Section “Material and methods”. In Section “Machine-learning methods for estimating crop yield”, Machin learning methods, and Section “Deep-learning methods for estimating crop yield”, Deep Learning methods and experimental evaluation are offered. Section “Metrics for model evaluation” describes metrics for evaluation, Section “Results and discussion” describes results and discussion, and the research concludes in Section “Conclusions”.

Related work

Numerous recent studies have focused on factors associated with forecasting agricultural yields, employing various approaches and datasets in these analyses. Agriculture yields were predicted using MODIS NDVI data by3. They stressed the need to investigate factors like soil water availability. Soil salinity, matric potential, and the efficiency with which crops use water were the subjects of investigation by4. Their research provides new insight into the importance of soil conditions. Soil surface management and the amount of precipitation in dryland areas were also the focus of He et al.'s study5. Their research makes understanding the impact of these variables on soil water storage capacity and winter wheat yields easier. The spatial and temporal trends of North China’s winter wheat production potential and yield gap were also studied by Chen et al.6. This study9 examined how MODIS NDVI and EVI images correlate with harvest success. The impact of heat stress and temperature patterns on the development and maturation of winter wheat was also studied by10 and12. Their research shows how easily unfavorable conditions can harm wheat. High-temperature effects on wheat senescence in India were studied by35. Their research provides new insight into the impact of harsh weather on crop development. Remote sensing imaging for estimating crop yields has been studied by8, and a radiation utilization efficiency and leaf area index has been constructed and described by14. Heat stress, according to a theory by Semenov and Shewry15, might increase wheat’s susceptibility to disease in Europe. Researchers17 examined how high temperatures after anthesis affected leaf senescence and grain filling in several wheat varieties. Finally, Mutanga18 used narrow-band vegetation indicators to address the issue of biomass estimation saturation. Environmental parameters such as climatic conditions, temperature, rainfall, vegetative index, soil type, texture, and nutrients significantly impact crop production prediction. Deep learning approaches will provide a prediction value based on environmental inputs19. Machine learning is a viable way to improve yield prediction based on various factors. It is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) concerned with learning. Machine learning (ML) may learn from data by recognizing patterns and connections. The models must be trained in datasets representing earlier experience-based outcomes. Deep learning methods for crop yield prediction are becoming increasingly popular. Deep learning is a type of machine learning that can predict outcomes from a wide range of raw data configurations. Deep learning algorithms, for example, may create a probability model from 10 years of field data and provide insights regarding crop yield under different climatic conditions. Deep learning employs artificial neural networks (ANNs) to mimic humans’ thinking and learning. The authors of this study20 predicted agricultural yield in Rajasthan’s 33 districts. The authors used four machine learning and one deep learning method to compare model performance. An Artificial Neural Network was combined with a regression approach to estimate agricultural yield. In terms of photos, soil qualities, and environmental conditions, where the inputs and obtained labels were. Crop photos were acquired regularly and assessed based on the level of periodic growth. To anticipate the percentage of yield, the level of growth is measured to identify the correctness of growth concerning height, disease, and various development phases21. The CNN approach is mainly used in deep learning to process cropped images. The images in the convolution neural network were analyzed pixel by pixel in a matrix format, and the resulting filter was referred to as a convolution. The value for estimation for yield prediction would be calculated after crop photos were recorded at each stage and validated with the amount of growth based on regression and computation36. A deep Neural Network is an ANN that employs numerous hidden layers in addition to the output layer. DNN was mainly used instead of multivariate characteristics to connect the complex terminals. Plant genotype and other plant growing features are mapped with the climate in this approach to estimate crop production. Where the plant’s genotype interacts with the crop’s chemical substances, which form the plant’s soul. The maize and rice crops were harvested, and their genotypes were mapped and trained with the DNN. It was entirely based on classification prediction, and the estimation accuracy was 64%23,24. A deep Neural Network is an ANN that employs numerous hidden layers in addition to the output layer. DNN was mainly used instead of multivariate characteristics to connect the complex terminals. Plant genotype and other plant growing features are mapped with the climate in this approach to estimate crop production. Where the plant’s genotype interacts with the crop’s chemical substances, which form the plant’s soul. The maize and rice crops were harvested, and their genotypes were mapped and trained with the DNN. It was entirely based on classification prediction, and the estimation accuracy was 64%25,26. A hybrid network includes a neural network as well as machine learning techniques. Crop management requires crop monitoring utilizing a wireless sensor network to monitor temperature and humidity to predict rainfall, aiding irrigation systems27,28. The input data were trained using a self-learning system that measures and predicts with an accuracy of 89%29. Multi-temporal data and satellite photos were used to improve the climatic conditions and rainfall prediction. It was identified using a Bayesian classifier and analyzed using a multilayer feed-forward network, which forecasts rainfall with an accuracy of up to 87.7%. According to the above literature review, this problem has been examined in the literature from several perspectives. Most of the work in this sector uses machine learning algorithms to assist farmers with crop prediction to increase yield and overall productivity. However, many research studies have not explored a real-world problem for classification and performance evaluation. Furthermore, the authors failed to provide explicit notifications regarding the accuracy of the obtained data. In30, the authors offered analysis and performance ratings with 99.45% accuracy, but only on 22 selected crops and not actual data. Table 1 shows factors used in different techniques and limitations in existing techniques for crop yield prediction.

Traditional machine prediction techniques often utilize methods such as linear regression, decision trees, and ensemble learning. Linear regression, a straightforward and widely used machine learning approach, models the relationship between crop yield and various influencing factors by fitting a linear equation. Factors such as historical weather data, soil quality, and crop varieties can be integrated into a linear regression model to predict crop yields. Decision trees, on the other hand, use a tree-like structure to make predictions by segmenting and analyzing the dataset. They can establish relationships between crop yield and influencing variables to generate predictions. Ensemble learning, a more advanced approach, enhances prediction accuracy and stability by combining the outputs of multiple base models. Techniques like random forests and gradient boosting trees, which aggregate multiple decision tree models, are commonly applied in crop yield prediction for better results. However, traditional machine learning methods often face certain limitations when addressing these challenges. These methods usually rely on manual feature extraction, which increases the need for human involvement31.

In this context, deep learning has become a widely adopted technology in the agricultural sector, as it effectively manages spatiotemporal data dependencies and automatically extracts essential features, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering.

Deep learning utilizes multi-layer neural networks that can learn abstract features from large datasets in supervised, semi-supervised, or unsupervised settings. This approach emphasizes uncovering the relationships between functional attributes and interaction factors, which is essential for precise crop yield prediction32.

This research, taken as a whole, sheds light on the various elements that influence crop yield predictions, a crucial part of agricultural output that is often overlooked. Table 1 shows a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art methods.

Material and methods

Proposed approach

For this investigation, location data for the location under study, located at 423 feet (129 m) above sea level, were available for this analysis. It is in the semiarid Multan District of Punjab, Pakistan, and has 437 acres and an area of 3721 square kilometers, as reported by Crop Report Services Punjab. Every year, we see an average of 304 mm of rain and a temperature of 26.2 degrees Celsius. Summers are wetter than winters in terms of precipitation. The framework’s flow diagram Fig. 1 Shows a decline in November and a rise in January.

Multan’s top layer of soil is composed of fine sand, known as silt, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Multan’s mixed-cutting zone cultivates sugarcane, maize, wheat, and rice. In Fig. 1, the scientific model involves collecting a raster Landsat image from the satellite USGS, calculating NDVI values, collecting factor datasets from various sources, and applying ML and DL techniques to predict wheat crop yield. It rains heavier in the summer than in winter. Data Source From 2017 to 2022, researchers gathered information on the region’s weather and climate and its soil and crop yields and distribution. Table 2 presents a summary of all the input variables. We started by resampling the data to have a spatial resolution of districts and a temporal resolution of months. Then, more cover was added based on where the winter wheat was planted. Ultimately, we arrived at district-level averages for all the Multan. ArcGIS and the GEE platform were used to bulk up the analysis.

While the focus on Multan provides valuable localized insights, the reliance on region-specific data limits the generalizability of the findings. To strengthen the robustness and applicability of the proposed models, external validation across diverse agro-climatic zones in Pakistan is essential. Future studies should incorporate data from additional regions to assess model performance under varying environmental and cultivation conditions. This broader testing will help ensure that the approach is scalable and adaptable to other areas beyond Multan.

The study’s focus on the Multan district restricts its generalizability because the findings are based on localized data that may not represent the diverse agricultural, climatic, and socio-economic conditions of other regions in Pakistan or globally. Variations in soil types, weather patterns, crop varieties, farming practices, and access to resources can significantly influence the outcomes, making it challenging to apply the study’s conclusions universally without additional region-specific validation.

Remote sensing data

We collected data on the normalized difference between the vegetation index (NDVI) and the vegetation index (VI). The ever-changing plant life can be monitored with a vegetation index. Multiple studies have linked harvest success to NDVI2,3. The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is a single number derived from measurements in the red, near-infrared, and blue spectral bands. The Vegetation index for the Multan district of Pakistan was calculated using satellite data captured by the Landsat8-9 satellite at a spatial resolution of 250 250 m (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) shown in Fig. 2 Every 30 days; we refresh this data set. We annualized the monthly sequential NDVI using the maximum synthesis method (MVC).

Shows calculated NDVI values every month from 2017 to 2022 winter wheat cropping season. (This figure is created using ArcGIS 10.2 software, which is an Esri product, utilizing our dataset and Google imagery for their generation that is openly available at that URL https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcwatch/the-best-of-arcgis-10-2).

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and remote sensing technologies play a crucial role in modern agricultural prediction models, particularly for crop yield estimation. These tools offer valuable, high-resolution, real-time data on vegetation health, growth, and stress, which are essential for accurate predictions. However, their integration into predictive models, particularly in crop yield forecasting, is often underexplained, which can reduce the understanding of their significance. The importance of NDVI and remote sensing in crop yield prediction cannot be overstated. These technologies provide real-time, high-resolution, and spatially detailed data, which is essential for accurate predictions. Their integration into predictive models, particularly through time-series analysis, data fusion, and deep learning, enhances the robustness and precision of crop yield forecasts. However, further explanation of how to effectively incorporate these technologies into predictive models will improve model transparency and reliability, ultimately benefiting farmers and policymakers by providing better tools for agricultural decision-making and planning.

Climate data

Parameters of the climate, such as temperature and rainfall, have a significant impact on crop yields37,38. Extreme heat and drought39,40,41 are two ways global climate change harms agricultural production, as shown in Fig. 1. Monthly maximum and minimum temperatures, the drought index, and precipitation totals were used to make projections for the winter wheat harvest. Downloadable weather data from the Pakistan Meteorological Department, Government of Pakistan, is available via the POWER Data Access Viewer (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-viewer/), the most common and vital component of any agricultural production. To obtain country-specific climate variables for 2017 through 2022, the Terra Climate datasets were processed on the GEE platform. We have created Figs. 2 and 3 using ArcGIS 10.2 software, which is an Esri product, utilizing our dataset and Google imagery for their generation that is openly available at that url https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcwatch/the-best-of-arcgis-10-2.

Land use land cover of study area Multan South Punjab Pakistan from 2017 to 2022. (This figure is created using ArcGIS 10.2 software, which is an Esri product, utilizing our dataset and Google imagery for their generation that is openly available at that URL https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcwatch/the-best-of-arcgis-10-2.)

Soil data

The soil, specifically the soil water and the soil’s physical and chemical qualities, plays a significant role in crop yield by4. For instance, increased soil moisture can boost yields in dryland regions where winter wheat is grown5. Soil factors such as organic carbon content and pH were measured between 0 and 30 cm. The Punjab Soil Fertility Authority collected the data in Multan but could have benefited from better organization.

Wheat yield data and planting area

Using data from the Crop Report Services CRS Punjab Government Department and some unpublished county-level data from the Pakistan Statistical Bureau, we calculated the average annual yield of winter wheat in Multan district, Pakistan, in kilograms per hectare (ha) for the years 2017 through 2022. The data that exceeded the biophysically possible yields (3SD) was thrown out after we calculated the mean and SD of the yield time series at each site6. Using the extracted wheat phenology, we located pixels throughout a 6-year time span that were optimal for growing winter wheat at each of the three crucial phenology stages (green-up, anthesis, and maturity).

Identify the better time window for the training settings of wheat

Due to the abundance of information available at different points in a crop’s growth cycle, knowing when to take measurements of wheat characteristics to make an accurate yield prediction is crucial42. To assess the sensitivity of several environmental factors affecting wheat yields to the length of the growing season, we conducted a randomized controlled trial. Wheat in Pakistan is planted in September and harvested between the first and second weeks of April. To determine the best time for training machine learning models, we looked at data from 2017 to 2022. The scene is set during the first growth season (November–October), and it is concluded during the harvest season (April–May) (Fig. 2). October and May, October and April, November and May, and November and April are halves.

Field verification data is collected directly from ongoing experiments, farms, or trials. It is used for fine-tuning models and validating their predictions in real-world conditions.

Real-Time Climate Data: On-site weather stations provide precise temperature, humidity, and rainfall measurements. Better resolution than historical climate data.

Soil Tests: Field-specific soil nutrient analysis. pH, organic matter, and moisture content.

Water Measurements: Irrigation scheduling data from farmers. Real-time water quality tests (salinity, contaminants).

Crop Monitoring: Growth stage observations. Pests and disease incidence.

Yield Data: Actual measured yield during harvest. Verified yield data for specific field plots.

Remote Sensing and Drones: High-resolution images for monitoring plant health. Field-level mapping for CNN applications.

Quality Checks and Validation of Data Sources is Data reliability, particularly from Punjab Soil Fertility Authority (PSFA) and other sources, requires rigorous validation. The following steps ensure accuracy:

-

(a)

Cross-Verification with Independent Datasets

-

Soil Data: Compare PSFA reports with data from Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) and FAO Soil Maps.

-

Climate Data: Validate Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) data against global datasets like ERA5 (ECMWF Reanalysis) and NASA POWER.

-

-

(b)

Data Consistency Checks

-

Perform time-series consistency analysis to detect anomalies in historical data.

-

Use spatial interpolation techniques (e.g., Kriging) to estimate missing values.

-

-

(c)

Outlier Detection and Removal

-

Use Z-score and IQR (Interquartile Range) methods to identify outliers in numerical data.

-

Apply domain expertise (e.g., unrealistic wheat yield spikes in historical records).

-

-

(d)

Ground-Truthing with Field Surveys

-

Conduct farmer interviews and collect on-ground GPS-tagged soil samples to validate lab-reported fertility data.

-

Compare NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) trends from satellite images with observed crop growth.

-

While Multan District is well-documented, its representativeness for other wheat-growing regions in Pakistan must be elaborated. Consider the following points:

(a) Agro-Climatic Zone Classification Multan falls in the Irrigated Plains Zone, a primary wheat-producing region. However, wheat is also grown in: Rainfed Areas (Barani Zones): Potohar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Southern Semi-Arid Regions: Sindh and Balochistan. (b) Justification for Selection Multan has diverse soil conditions, ranging from loamy to sandy loam, making it comparable to Punjab, Sindh, and KP. Irrigation dependency: Multan relies on both canal irrigation and groundwater, similar to Faisalabad, Sahiwal, and Bahawalpur. (c) Expanding the Study Area Validate models in additional districts like Sargodha (Punjab), Dera Ismail Khan (KP), and Sukkur (Sindh). Train on multisource datasets to generalize the model beyond Multan.

If the data sources, such as soil data from the Punjab Soil Fertility Authority, lack proper validation or quality checks, it raises concerns about the reliability and accuracy of the data used in the study. Without clear documentation of the data collection processes, verification methods, or quality assurance measures, there is a risk of using incomplete, biased, or inaccurate information, which can compromise the study’s conclusions and limit its credibility.

Machine-learning methods for estimating crop yield

In this paper, we deployed three different high-powered machine-learning techniques. The first 6 years, from 2017 to 2022, were used to establish all variables and serve as training data. We normalized all dataset variables using the z-score method before developing any models. All procedures were implemented using GEE and ArcMap 10.3. Figure 3 shows the district of Multan’s land use area for wheat and other crops.

Support vector machine (SVM)

SVM is a supervised, non-parametric approach that uses marginal kernels43. When minimizing errors without overfitting the model, SVM regression uses a kernel function to map the input onto a high-dimensional feature space, where a linear regression model is subsequently built. Among the most crucial hyper-parameters to tweak are the kernel functions used in the model (Fig. 4).

Support vector machine (SVM) algorithm44.

This right here is the weight vector, often known as the bias. Separating the data into training and testing sets allows us to Evaluate the performance of the SVM model. During training, the SVM approach modifies the hyperplane’s initial point to minimize the gap between expected and actual harvests. The effectiveness of the trained model is evaluated by applying it to test brand-new data. SVM’s processing cost grows with data size. Hence, it may behave differently when working with massive datasets. A backup plan for estimating wheat output is helpful in such cases, and systems like Random Forest provide just that—district of Multan, GEE Landsat 8 Collection 2, Level 1 TOA. The analysis relied on photos captured in the reflective mode. Clouds have been digitally removed from a time-lapse of wheat growth starting in March 2017 and continuing through 2022. After defining a search area (ROI), spatial characteristics of wheat fields can be retrieved from satellite imagery. In addition, when the data is in numeric form, and we want to predict the target attribute, we can use SVM for the regression model. SVM regression aims to determine the function f(x) shown in Eq. 1, which has a non-conformity since the obtained target Yield value is against the trained data. It can be explained as when the errors are more significant than then, we can’t accept the mistake, but the error has been neglected in the case of fewer errors. Chosen for their ability to handle complex, high-dimensional data and provide robust performance even in cases with limited data. The decision to use SVM stems from its effectiveness in high-dimensional spaces, where crop yield prediction may involve various non-linear relationships.

Random forest (RF)

Noise-tolerant tree predictors are compiled in a random forest44,45. All trees in the forest follow the same distribution because they are all constructed from randomly chosen variable sets and dataset samples. They will generate many distinct trees and vote on the most common types. Therefore, throughout the past decade46,47, RF has demonstrated its capacity to manage high-dimensional datasets without overfitting. The relative importance of measured variables may be quantified with RF, and it is an efficient method for selecting relevant variables13, as shown in Fig. 548. Step 1 of the Random Forest Algorithm randomly selects K instances from the provided training dataset. The second stage is developing decision trees for the sampled cases. Third, decide how many estimators you want to make (N). Repeating Steps 1 and 2 becomes Step 4. Fifth, we ascertain each estimator’s forecast for the novel occurrence. RF employs several trees and “bagging” to combine decision trees into a single model. It uses bootstrapping to select K samples at random from the original dataset. These training data are used to construct decision trees to develop the RF model.

Random forest (RF) classifier process diagram48.

Selected for its ability to handle large datasets, account for feature interactions, and provide insights into feature importance. RF’s flexibility in accommodating both numerical and categorical data makes it suitable for integrating diverse environmental factors like soil type, weather conditions, and satellite imagery.

Lasso regression (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression)

Lasso Regression’s feature selection functionality is a significant selling point. The model eliminates certain predictors from the final prediction equation by nullifying specific coefficients. This ensures that only relevant features contribute to the output, while unnecessary ones are successfully deleted, which increases the model’s interpretability. Suppose we use Lasso Regression to estimate wheat yields. In that case, we might learn which aspects of the environment (such as soil quality, weather information, and land cover) affect wheat production. During the feature selection phase, variables with non-zero coefficients after shrinkage are included in the model. The purpose of the process is to decrease prediction errors. The tuning parameter for regularization quantity control was obtained in this study using tenfold cross-validation. The path length (min_lambda/max-lambda) was set to 0.001, and 100 default settings were evaluated throughout the regularization phase to identify the best lambda value49. The research area’s agricultural productivity can be better understood using this feature selection technique.

Deep-learning methods for estimating crop yield

In this paper, we used three different deep-learning techniques, the details of which are provided below.

Convolutional neural network (CNN)

The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning model initially developed for image processing. We analyzed satellite data using CNN to estimate wheat yields and discovered regional patterns associated with wheat productivity19. The multiple convolutional layers comprising the CNN architecture are responsible for automatically learning and extracting relevant features from incoming images (Fig. 6). These attributes are fed into fully connected layers to forecast yield. Because of their structure, CNNs require a vast quantity of training data to converge—the advantage of CNNs in agricultural yield prediction over standard machine learning methods.

Convolutional neural network (CNN) work process for crop yield prediction of wheat19.

CNNs are designed to process grid-like data structures, making them ideal for analyzing spatial data such as satellite images, heatmaps, or other visual agricultural datasets.

They can automatically extract and learn spatial patterns, such as texture or land use, which are crucial for tasks like crop monitoring, soil quality assessment, or identifying vegetation types.

Recurrent neural network

A recurrent neural network (RNN) is a deep learning model developed especially for processing time series and other forms of sequential input. We used RNN to examine historical heat yield data for trends and temporal connections, as shown in Fig. 7. The RNN’s recurrent nodes enable time-dependent learning by storing data and feeding it back into the network at each time step. The basic structure of RNN is similar to the ANN, with the difference that the results of the previous step are also entered as input along with the new input at every step. In other words, the hidden layer takes input from the prior layer and uses its previous value to produce output for the next layer.

Recurrent neural network (RNN)23 work process for crop yield prediction of wheat.

RNN is an artificial neural network with a directed graph representing node temporal dependencies. As a result, we created a unique RNN model to capture the temporal dynamic behaviour of crop yield due to genetic improvement.

RNNs are designed to handle sequential or time-series data by capturing temporal dependencies and patterns.

Variants like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, allowing them to process long-term dependencies effectively.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

The Artificial Neural Network, or ANN, is a flexible model of deep learning that may be used for various tasks, including regression and classification. Within the scope of our research, we utilized ANN to estimate wheat yields by feeding it information regarding spatial features and historical yields (Fig. 8). The architecture of an ANN comprises several hidden layers connected via nodes. Because of these hidden layers, ANN can learn the intricate relationships and patterns in the data to create accurate yield estimates. Three sorts of parameters are commonly used to define an ANN for crop yield prediction:

-

1.

The pattern of connections between distinct layers of neurons

-

2.

The learning procedure for upgrading the interconnectivity weights

-

3.

The activation function translates the weighted input of a neuron to its output activation.

Working process of artificial neural network (ANN)50 for crop yield prediction.

Justifying the selection of specific ML/DL models requires a clear discussion of the dataset characteristics, task complexity, and the strengths and weaknesses of each model in the given context. Below is a structured justification for choosing CNN over RF and ANN over LSTM for field-scale winter wheat yield prediction.

F/XGBoost Predicting yield from tabular field data because High interpretability and efficiency for structured data. CNN Predicting yield from remote sensing images because of its Captures spatial features automatically, unlike RF. ANN Yield prediction using seasonal summary features because of its Handles static and aggregated features effectively and LSTM Yield prediction with sequential time-series data because of Captures long-term dependencies but requires high computational resources in51.

Metrics for model evaluation

When deciding between the three ML and DL methods, cross-validation (CV) is a popular tool for algorithm selection due to its ease of use, general applicability, and ability to prevent over-fitting7. Favoring the model with the most minor relative estimation error is common practice. Five-sample cross-validation was used to pick the best models for this analysis. We compared the machine learning model’s accuracy using several metrics, including the root-mean-square error (RMSE) in Eq. 3, the coefficient of determination (R2), and the mean absolute error (MAE).

The variables yi, yi, fi, and f i indicate the observed and predicted winter wheat yields, whereas n denotes the number of samples used in the machine learning model (i = 1, 2,…, n). Predictive ability increases as R2 in Eq. 2 approaches 1. Less of a gap exists between actual and predicted yields when the RMSE in Eq. 3 and MAE in Eq. 4 have smaller values. To evaluate the accuracy of the model’s predictions, we computed the root-mean-squared error, correlation, and mean absolute error. Research52,53,54 demonstrates that the Global Moran’s I measure for assessing the spatial autocorrelation of prediction errors supports model generalizability throughout the geographical domain. In the range of − 1 to 1, the global Moran’s I value can indicate a tendency towards clustering or spreading out, respectively. Spatial randomness is displayed by values close to zero, and more uncertainty suggests a more robust model55. This research used ArcGIS 10.3 and GEE to estimate the wheat yield.

Results and discussion

This section presents experimental setup and results. It is obtained using the three ML and DL models for wheat crop yield prediction in the focused region. To investigate the unique contribution of remote sensing data during a given timeframe, inputs from various times for both all-month climate data and remote sensing data are included. The distinction between using climate and remote sensing data jointly during the growth season and using climate data alone or remote sensing data exclusively is highlighted. We developed a comprehensive yield prediction model using weather, satellite remote sensing, and soil data to offer a framework for yield prediction for food sanctuary decision-making. Let’s examine why CNN, Random Forest, and SVM fared better than RNN and Lasso Regression in estimating wheat yield based on the stated RMSE values and ranking. Results can be categorized into the following sections.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using SVM.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using RF.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using LASSO.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using CNN.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using RNN.

-

Performance analysis of the proposed method using ANN.

Model performance with SVM

We trained an SVM model on the training dataset using GEE’s SVM classifier19. The SVM algorithm aims to find an optimal hyperplane that separates the wheat yield data points based on their spatial attributes. It learns to predict wheat yield values from the input features, such as soil characteristics, weather conditions, and land cover. The SVM model is applied to the Landsat 8 imagery to predict wheat yield across the study area. The classified map displays the spatial distribution of wheat yield values, providing valuable insights into crop productivity variations. The results are visualized using a color palette representing different wheat yield levels. Over the analyzed 6-year period, from 2017 to 2022, wheat cultivation in Multan District exhibited fluctuating trends in area and yield. Despite these variations, the wheat yield per acre showed a more stable pattern, ranging from 35 monads per acre in 2019 to 41 monads per acre in 2018. This suggests that although the cultivated area changed over the years, the productivity per acre remained relatively consistent. Total yield, which accounts for the area and per acre yield, experienced similar fluctuations. The total yield reached its highest point in 2018, at 932.01 tons, and dipped to its lowest in 2022, at 639.80 tons. Notably, the total yield in 2022 decreased even though yield was relatively high at 37 months per acre. This indicates that the reduction in the cultivated area significantly impacted the overall wheat production. To analyze the trends in wheat yield, we compiled wheat production data for the years 2017–2022. Table 3 presents the wheat area (in acres), yield per acre (tons), and total yield (tons) for each year. The data is also depicted in Fig. 9. We examine the overall increase in wheat yield over the 6 years and explore the factors contributing to this growth.

The time series analysis reveals a substantial increase in wheat yield in Multan District from 2017 to 2022, driven by improved wheat varieties, agricultural practices, and favorable climatic conditions. Table 4 compares SVM-predicted data with the data from our benchmark crop report services that CRS provided.

Figure 10 compares SVM and CRS of all indicators like area per acre, yield per acre, and total production in tones from 2017 to 2022.

Model performance with random forest RF

The trained Random Forest model is applied to the Landsat 8 imagery to predict wheat yield across the Multan District.

The resulting classified map visually represents the spatial distribution of predicted wheat yield values. We employ a color palette to distinguish different levels of wheat productivity. We compile wheat production data for 2017 to 2022 to assess wheat yield trends. Table 4 presents the wheat area (in acres), yield per acre (tons), and total yield (tons) for each year. We analyze the temporal variations and growth in wheat yield to gain insights into the factors contributing to increased productivity.

While SVM and Random Forest provided accurate predictions, each method has strengths and weaknesses. SVM excelled in capturing complex relationships in smaller datasets, delivering precise yield estimates based on spatial attributes.

On the other hand, Random Forest offered robustness and scalability, making it a reliable choice for larger datasets and extensive agricultural analyses. Over the analyzed 6-year period, from 2017 to 2022, as shown in Table 5, wheat cultivation in Multan District exhibited fluctuating trends in area and yield. Despite these variations, the wheat yield per acre showed a more stable pattern, ranging from 30 monads per acre in 2019 to 36 in 2018. This suggests that although the cultivated area changed over the years, the productivity per acre remained relatively consistent. Total yield, which accounts for the area and per acre yield, experienced similar fluctuations. The total yield reached its highest point in 2018, at 721.02 tons, and dipped to its lowest in 2022, at 496.08 tons, as shown in Table 5. Notably, the total yield in 2022 decreased even though yield was relatively high at 37 months (Fig. 11). This indicates that the reduction in the cultivated area significantly impacted overall wheat production.

Figure 12 compares RF and CRS of Area per acre in tones from 2017 to 2022.

Model performance with LASSO

A time series of wheat yield data for 2017 to 2022 is analyzed to examine yield trends and growth in wheat production. The table presents the wheat area (in acres), yield per acre (tons), and total yield (tons) for each year, allowing us to observe the changes in wheat productivity over time. Table 6 compares LASS and CRS of all indicators like area per acre, yield per acre, and total production in tones from 2017 to 2022.

The successful application of Lasso Regression for wheat yield estimation showcases the potential of regression-based machine learning methods in agriculture. Future research can explore integrating additional data sources, such as weather data and soil samples, to enhance model accuracy. Moreover, investigating the combination of Lasso Regression with other machine learning and deep learning techniques can further improve wheat yield estimation in the Multan District and beyond. Over the analyzed 6-year period, from 2017 to 2022, as shown in Table 6, wheat cultivation in Multan District exhibited fluctuating trends in area and yield. Despite these variations, the wheat yield per acre showed a more stable pattern, ranging from 28.63 monads per acre in 2019 to 33.51 per acre in 2018. This suggests that although the cultivated area changed over the years, the productivity per acre remained relatively consistent. Total yield, which accounts for the area and per acre yield, experienced similar fluctuations. The total yield reached its highest point in 2018, at 623.55 tons, and dipped to its lowest in 2022, at 428.10 tons, as shown in Table 6. Notably, the total yield in 2022 decreased even though yield was relatively high at 37 months per acre (Figs. 13, 14). This indicates that the reduction in the cultivated area significantly impacted overall wheat production.

Model performance with CNN

In deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are state-of-the-art tools best suited to processing visual data. We used CNN to examine satellite images and locate spatial patterns associated with wheat yield estimation. Multiple convolutional layers in the CNN architecture automatically learn and extract features from the input images. These traits are then input into fully linked layers, which forecast yield. Area pre-acres, yield per acre, and total production in tones are just some of the parameters from 2017 to 2022 that are compared between CNN and CRS in Table 7 and shown in (Figs. 15, 16).

Over the analyzed 6-year period, from 2017 to 2022, as shown in Table 7, wheat cultivation in Multan District exhibited fluctuating trends in area and yield. Despite these variations, the wheat yield per acre showed a more stable pattern, ranging from 36.35 monads per acre in 2019 to 41.25 monads per acre in 2018. This suggests that although the cultivated area changed over the years, the productivity per acre remained relatively consistent.

Total yield, which accounts for the area and per acre yield, experienced similar fluctuations. The total yield reached its highest point in 2018, at 883.58 tons, and dipped to its lowest in 2022, at 604.60 tons, as shown in Table 7. Notably, the total yield in 2022 decreased even though yield was relatively high at 37 months per acre. This indicates that the reduction in the cultivated area significantly impacted the overall wheat production.

Model performance with RNN

Let’s look at why the provided RMSE values and ranking suggest that CNN, Random Forest, and SVM are the best methods for estimating wheat production, while RNN and Lasso Regression are the worst. With an RMSE of 0.9264, SVM ranked third best. Regarding classification and regression, SVM is a very effective method. It functions optimally when categories or data points can be easily distinguished from one another. It could have found some valuable patterns in the data for estimating wheat yield, but not as successfully as CNN or Random Forest. Prediction errors could have been more significant because SVM failed to recognize the data’s subtle spatial or temporal patterns. With an RMSE of 0.9576, Random Forest came in second to CNN regarding accuracy. The Random Forest method of ensemble learning mixes the outputs of several different prediction trees shown in Fig. 17. It excels in capturing intricate connections in the data and dealing with many attributes.

Model performance with ANN

The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is a versatile deep learning model extensively employed in diverse regression and classification tasks. In our investigation, we harnessed the power of ANN to address the wheat yield estimation challenge, furnishing it with both spatial attributes and historical yield data. The architecture of our ANN encompasses multiple hidden layers featuring interconnected nodes. These concealed layers empower the ANN to acquire intricate relationships and patterns embedded within the data, facilitating accurate predictions of the wheat yield shown in Fig. 18.

Table 8 the predictive performance of the six models using both factors.

However, compared to CNN, it might not have been able to handle the data’s spatial or sequential nature as effectively, leading to slightly higher prediction errors. Lasso Regression achieved the highest RMSE value of 0.0432 among the worst-performing methods. Lasso Regression is a linear regression model with L1 regularization, which helps in feature selection and can deal with high-dimensional data. However, complex tasks like wheat yield estimation might not have the expressive power to capture non-linear relationships and complex patterns in the data, resulting in higher prediction errors. In summary, CNN, Random Forest, and SVM performed better in wheat yield estimation because they can handle complex patterns and relationships in the data. In contrast, RNN and Lasso Regression might not have been as effective in capturing the data’s spatial, temporal, or non-linear characteristics, leading to higher prediction errors. The success of CNN can be attributed to its inherent ability to learn intricate spatial patterns, which is especially valuable when dealing with image-like data, such as crop fields. The CNN model achieved the lowest RMSE value of 0.0600, which means its predictions were an exact match with the observed values. This indicates that the CNN model could capture complex patterns and features in the data, leading to highly accurate predictions.

CNNs are well-known for their ability to learn spatial and temporal patterns, making them suitable for tasks involving images, sequences, and time-series data like wheat yield estimation. The model might have effectively learned meaningful representations from the input data, leading to superior performance. Table 9 shows the overall accuracy of all six methods regarding R2, MAE, and RMSE.

After all results and comparisons, it concluded that SVM. And RF produced the best result in this study area within stud area factors like temperature, precipitation, humidity, Soil, etc. Table 5 compares all techniques with CRS data of Total production in the whole district of Multan from 2017 to 2022.

Figure 19 shows the accuracy in percentage in the scenario of the study area. With the current factor, results show CNN and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) outperform traditional machine learning models in wheat crop yield prediction, particularly when satellite imagery or spatial data (NDVI, EVI, soil moisture maps) is involved.

Traditional ML models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) rely on structured tabular data (temperature, rainfall, soil fertility, etc.), while CNNs can analyze spatial patterns in remote sensing images. Unlike manual feature selection in ML models, CNNs automatically learn important visual patterns from images, reducing human bias. When combined with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, CNNs can process both spatial and temporal data. CNNs work well with large-scale datasets, unlike models like Support Vector Machines (SVM), which struggle with high-dimensional data.

RF is the best classifier, with 98% and 97% returns. After that, SVM was also the best and returned 93%. Results show that LASSO has the lowest accuracy, 80%, for our study area, as shown in Fig. 19. Table 10 compares all six methods with CRS, which is the benchmark in this study.

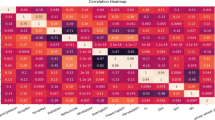

Important factor selection

According to previous studies, the analysis employed only two yields from the year before. As a result, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC)56 between each data set. Both the water-related and the temperature-related climatic variables were classified separately. The group-specific correlation coefficients are shown in Fig. 14, which shows that one is closer to the other and 0 is less close.

The NDVI had a favorable relationship with overall yield, while the temperature-related components had a negative relationship57. The remaining two categories showed positive and negative correlations.

Correlation between factors in wheat crop yield prediction refers to the statistical relationship between various environmental, agronomic, and biological variables and the yield of wheat. These factors can influence each other and collectively determine the final crop yield. Understanding these correlations can help optimize wheat production by identifying the most significant factors and their interactions58.

Temperature versus Yield: Positive correlation within optimal range; negative correlation during extremes.

Rainfall versus Soil Moisture: Positive; rainfall increases soil moisture unless excessive, causing waterlogging.

Temperature versus Rainfall: Weak or inverse correlation in some regions; high temperatures can coincide with dry conditions.

Soil pH versus Nutrient Availability: Strong correlation; optimal pH ensures better nutrient uptake.

Organic Matter versus Soil Moisture: Positive correlation; organic matter improves water retention.

NPK Nutrients versus Yield: Positive; higher nutrient levels typically improve yield, up to saturation.

Irrigation versus Soil Moisture: Strong positive correlation.

Irrigation Frequency versus Yield: Bell-shaped curve; optimal irrigation increases yield, but excessive irrigation decreases it.

Drainage versus Yield: Positive correlation in regions prone to waterlogging.

Temperature versus Soil Moisture: Negative; high temperatures often reduce moisture through evaporation.

Rainfall versus Irrigation: Inverse correlation; high rainfall reduces the need for irrigation.

Soil Moisture versus Yield: Positive; adequate moisture improves crop health.

Key variables and their impacts for wheat crop yield prediction

The impacts of various variables on wheat crop yield prediction are categorized based on their influence on the crop’s growth, development, and productivity. These variables can be broadly classified into climatic, soil, agronomic, and biotic factors, each with distinct effects

Temperature: Optimal temperatures promote growth; extreme heat or cold reduces yield.

Impacts photosynthesis and respiration rates. Critical during specific growth stages, like germination and flowering.

Rainfall: Essential for maintaining soil moisture but can cause waterlogging if excessive. Seasonal distribution is more critical than total rainfall.

Humidity: Affects evapotranspiration and disease prevalence.

Solar Radiation: Drives photosynthesis; low radiation during key phases can limit yield.

pH: Determines nutrient availability. Impacts microbial activity on the soil.

Nutrients (NPK): Directly influence plant growth and grain formation.

Organic Matter: Improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient supply.

Soil Texture: Influences drainage and root penetration.

Irrigation Frequency: Adequate irrigation prevents water stress and boosts yield.

Water Quality: High salinity or contaminants can harm plant health.

Drainage: Ensures proper root aeration and prevents waterlogging.

Model performance for estimating yields in different time windows

Meteorological data, satellite observations, and soil characteristics were combined to predict yields and support food supply decisions. What makes each machine-learning and deep-learning algorithm distinct has been studied. The top three machine learning algorithms are LASSO, SVM, and RF, and the top three deep learning algorithms are ANN, CNN, and RNN. Our findings further reinforce the previous research that longer time series better capture the diversity of growth conditions for yield estimation59, as different environmental parameters associated with winter wheat production were sensitive to the growing season. Our study’s time range could be employed at Pakistani wheat planting sites, although crop phenology may determine the best month combination. Winter wheat heading season in this study runs from February to March. Remote sensing vegetation indicators like NDVI can reveal crop physiology at different stages60,61. Precipitation, soil moisture, and drought index heavily influence wheat production prediction. Climate parameters may provide more spatial and temporal information for yield prediction than NDVI in early growth phases when they are least associated. When weather was significant, and NDVI contributed later to growth, yield models predicted winter wheat yields effectively. When remote sensing vegetation indices and climatic parameters are incorporated, early and late-season climate variables may improve yield projections62. Because they better captured the complexity of growing conditions, longer-term predictors predicted yield better. Results support the claim that complex and variable factors affect wheat growth and production. The black-box nature of machine learning limits our plant physiology results. Input–output correlations can be explained using agricultural process models63. Table 10 shows the Overall comparison of Wheat crop Production in Tones of SVM, RF, LASSO, CNN, RNN, and CRS of Multan district from 2017 to 202264.

Accuracies comparison of proposed method with existing studies

Table 10 shows the accuracy of the testing data from training the six models independently using the complete and selected variables to compare model performance and evaluate factor selection. Table 9 illustrates the RMSE (kg/acre), MAE, and R2 of SVM, ANN, LASSO, RF, CNN, and RNN district yield forecasts65,66,67. The findings were averaged to account for initialization randomness and DL model training data loss. Each row indicates the model’s projections for a given year based on data from prior years. County-scale winter wheat RMSE and R2 were constant during the study. In 2017, the CNN model had a very high RMSE of 2.2667, 39.05 per acre (15.8% of the average yield). All six models had an average R2 of 0.85 and an average RMSE of 768 kg/ha for district-level winter wheat yield from 2017 to 202268. This was especially true for the RF and SVM models (average R2 = 0.582 and RMSE = 658.39 and 848.17 tones, respectively). Figure 15 further showed that various models meeting the criteria were able to achieve yields that were consistent with predictions. According to the results, SVM (a), RF (b), and CNN (d) statistical models had the highest degree of agreement out of the six statistical models, while the ANN (e) and RNN (f) methods had the lowest degree of agreement shown in Fig. 3 It also shows the overall accuracy of all methods in Fig. 4. We also found that the LASSO and SVM models overestimated yields while underestimating yields in some high-yield scenarios. It isn’t easy to anticipate the yield variance because there are so few high-yield samples.

Integrating multisource data is pivotal across diverse fields62,63, particularly in crop yield prediction, as it enhances accuracy by amalgamating varied information streams. The wheat yield in the Multan region has been increasing over the past few years, but several factors can affect it. These factors include Wheat, which is a cool-season crop, so it is sensitive to high temperatures. The optimum temperature for wheat growth is between 15 and 25 degrees Celsius. If temperatures are too high during the growing season, it can lead to reduced yields, for example, according to a study by Pakistan Agricultural. Research Council found that wheat yields decreased by 10% for every degree Celsius above 25 degrees Celsius48,69,70. Wheat requires a moderate amount of rainfall to grow. The average annual rainfall in the Multan region is about 300 mm. If there is too little rain, the crop will not be able to produce a good yield. However, too much rain can also be a problem, leading to flooding and waterlogging, damaging the crop. For example, an International Rice Research Institute study found that wheat yields decreased by 10% for every 100 mm of rainfall above the optimum level of 500 mm. The monsoon is a seasonal wind system that brings rain to Pakistan. The monsoon pattern has been changing recently, with some years being wetter than others71,72. This can significantly impact wheat yields, as a wetter year will typically lead to higher yields. For example, a study by the Pakistan Meteorological Department found that wheat yields in the Multan region increased by 20% in the wettest year of the study period (2010) compared to the driest year (2009).

Pakistani wheat yields will be affected by climate change. Droughts and floods are increasing across the country. These disasters can harm crops and lower production. According to the World Bank, climate change might reduce Pakistani wheat harvests by 20% by 2050. Increased wheat yields require fertilizers. Too much fertilizer can harm the environment and damage soil. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization determined that Pakistani wheat yields could drop by 10% if fertilizer use continues73.

The practices used by farmers can also have a significant impact on wheat yields. For example, if farmers do not use good irrigation practices, the crop may not receive enough water. The soil may deplete nutrients if farmers do not use good crop rotation practices74. For example, a study by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center found that wheat yields in Pakistan could increase by up to 15% if farmers adopted better irrigation practices.

The arrogant attitude of farmers: Some farmers are reluctant to adopt new agricultural technologies, such as improved seeds and irrigation systems. This can lead to lower yields. For example, a Pakistan Agricultural Research Council study found that wheat yields in Pakistan could increase by up to 10% if farmers adopted improved seeds. Some farmers may not be aware of the latest agricultural practices or technologies. This can also lead to lower yields75. For example, a study by the World Bank found that wheat yields in Pakistan could increase by up to 5% if farmers were more aware of the latest agricultural practices.

Its accuracy must be evaluated to determine how well a proposed wheat crop production prediction framework performs compared to alternative ML and DL approaches. Table 10 compares the proposed strategy to the state of the art to demonstrate the approach’s generalizability. The proposed deep and Machine Learning model outperformed state-of-the-art methods significantly. The recommended technique and the state-of-the-art procedures both have some degree of inaccuracy. Wheat prediction methodologies currently used in the literature were used to evaluate the suggested method. Compared to recent investigations, as shown in Table 11, the proposed technique achieved the highest accuracy (99%). The new proposed framework outperforms state-of-the-art approaches by a wide margin, achieving 98% accuracy with only 20 parameters while reducing processing costs to an absolute minimum.

The paper claims the proposed methods are novel and sufficiently demonstrates gaps in existing research, it likely provides a thorough review of prior studies, identifies their limitations, and highlights unexplored or underdeveloped areas. This analysis establishes a clear context for the need for the proposed methods, showing how they address specific shortcomings or expand upon previous work. By bridging these gaps, the study justifies its contribution to advancing the field.

The paper discusses the future challenges and development trends in crop yield estimation. These challenges go beyond data acquisition and model selection, particularly concerning the impact of climate change. Climate conditions are a significant factor influencing crop yield, but as climate change is a gradual and ongoing process, historical data may not accurately reflect current climate conditions, which can affect model prediction accuracy. To improve predictions, models need to adapt to changing climate trends and integrate new climate data.

Additionally, genetic factors play a long-term role in crop yield, with advancements in breeding technology leading to the evolution of crop varieties. Historical data may not fully account for the effects of these new varieties or genetic improvements on yield. Therefore, when relying on historical data for predictions, it is crucial to consider these genetic changes. To address this, dynamic updating mechanisms or incremental learning methods can help models adjust parameters as genetic data evolves, ensuring they remain responsive to the latest information. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) outperformed other models primarily due to its ability to effectively capture spatial patterns in data, which is particularly important for tasks like image-based crop yield prediction. CNNs are designed to recognize and extract hierarchical features from grid-like data, such as satellite imagery or spatially distributed environmental factors. By learning spatial hierarchies through convolutional layers, CNNs can identify local patterns (e.g., soil type, vegetation cover) and their spatial relationships more efficiently than models that don’t explicitly consider the spatial structure of the data. This makes CNNs well-suited for integrating and processing remote sensing data, where spatial dependencies are critical. Additionally, CNNs can automatically learn relevant features without the need for manual feature engineering, enhancing their ability to generalize across different regions and environmental conditions, leading to improved performance over models like SVM or Random Forest.

Looking ahead, further optimization of deep learning algorithms will enhance their predictive power and robustness. This will involve the development of deeper, more complex neural network architectures and customized algorithms tailored to the specific growth characteristics of crops, ultimately improving yield prediction accuracy.

Conclusions

In this paper, we utilized diver’s data sources, machine learning algorithms, and deep learning models to forecast winter wheat yields at the district level in south Punjab, Pakistan. Employing RF, SVM, and CNN models significantly enhanced the accuracy of wheat yield predictions, with RF exhibiting the most robust generalization capabilities. The Random Forest RF model effectively reliably anticipated wheat yields in Pakistan before the harvest season. Comparatively, CNN projected a 15% increase in wheat yield over other models. Furthermore, RNN and ANN models showcased 22% and 2% reduced prediction errors compared to the CNN. Our investigation into window selection revealed consistently high forecast accuracy during model development. We also observed that algorithms performed differently across various agricultural zones, with geography affecting production prediction accuracy. NDVI emerged as the most effective predictor for winter wheat output. We are confident that the generic framework built to anticipate winter wheat production using numerous data sources and the GEE platform holds promise for application in forecasting other crop yields in Pakistan and beyond. Our future endeavors involve exploring waterlogged and saline areas, wheat cultivation near riverbanks, and expanding our assessment to numerous districts in Punjab and other provinces of Pakistan to estimate wheat production. The study provides evidence to guide policymakers in formulating targeted, data-based interventions to improve agriculture, food supply reliability, and climate adaptability across Pakistan. Meanwhile, farmers can directly benefit from more accurate, locally-tailored crop yield predictions, better resource management, and climate adaptation strategies, ultimately improving their livelihood and the country’s agricultural sustainability.

Limitations of the Proposed Models are CNN models require significant GPU power (especially when processing high-resolution satellite images). Real-time predictions for small-scale farmers may be challenging. Model performance may decrease when applied to diverse regions due to differences in soil type, irrigation access, and farmer practices. Yield is influenced not just by climate and soil but also by farmer decisions (e.g., choice of wheat variety, pest control methods). Current models do not include socio-economic factors (e.g., access to credit, government subsidies).

Data availability

The data will be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code will be available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Ministry of Finance | Government of Pakistan |. Accessed: Oct. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey_1920.html

Huang, J., Wang, H., Dai, Q. & Han, D. Analysis of NDVI data for crop identification and yield estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 7(11), 4374–4384 (2014).

Mkhabela, M. S., Bullock, P., Raj, S., Wang, S. & Yang, Y. Crop yield forecasting on the Canadian Prairies using MODIS NDVI data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151(3), 385–393 (2011).

Khataar, M., Mohammadi, M. H. & Shabani, F. Soil salinity and matric potential interaction on water use, water use efficiency and yield response factor of bean and wheat. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 2679 (2018).

He, G. et al. Soil water storage and winter wheat productivity affected by soil surface management and precipitation in dryland of the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 171, 1–9 (2016).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Tao, F., Wang, P. & Wei, X. Spatio-temporal patterns of winter wheat yield potential and yield gap during the past three decades in North China. Field Crop Res. 206, 11–20 (2017).

Arlot, S. & Celisse, A. A survey of cross-validation procedures for model selection. Statist. Surv. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-SS054.short (2010).

Shanahan, J. F. M. D. J. Use of remote-sensing imagery to estimate corn grain yield. Agronomy J. 93, 583 (2001).

Fontana, D. C., Potgieter, A. B. & Apan, A. Assessing the relationship between shire winter crop yield and seasonal variability of the MODIS NDVI and EVI images. Appl. Gis 3(7), 1–16 (2007).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Tao, F., Palosuo, T. & Rötter, R. P. Impacts of heat stress on leaf area index and growth duration of winter wheat in the North China Plain. Field Crop Res. 222, 230–237 (2018).

Slafer, G. A. & Savin, R. Developmental base temperature in different phenological phases of wheat (Triticum aestivum). J. Exp. Bot. 42(8), 1077–1082 (1991).

Garg, D., Sareen, S., Dalal, S., Tiwari, R. & Singh, R. Grain filling duration and temperature Pattern influence on the performance of wheat genotypes under late planting. Cereal Res. Commun. 41(3), 500–507 (2013).

Jones, J. W. et al. The DSSAT cropping system model. Eur. J. Agron. 18(3–4), 235–265 (2003).

Tripathi, A. M. et al. The evaluation of radiation use efficiency and leaf area index development for the estimation of biomass accumulation in short rotation poplar and annual field crops. Forests 9(4), 168 (2018).

Semenov, M. A. & Shewry, P. R. Modelling predict that heat stress, not drought, will increase the vulnerability of wheat in Europe. Sci. Rep. 1(1), 66 (2011).

Webber, H. et al. Simulating canopy temperature for modeling heat stress in cereals. Environ. Model. Softw. 77, 143–155 (2016).

Zhao, H., Dai, T., Jing, Q., Jiang, D. & Cao, W. Leaf senescence and grain filling affected by post-anthesis high temperatures in two different wheat cultivars. Plant Growth Regul. 51(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-006-9157-8 (2007).

Mutanga, O. S. A. K. Narrow band vegetation indices overcome the saturation problem in biomass estimation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 25, 3999 (2004).

Jhajharia, K., Mathur, P., Jain, S. & Nijhawan, S. Crop yield prediction using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Proc. Comput. Sci. 218, 406 (2023).

Carew, R., Smith, E. G. & Grant, C. Factors influencing wheat yield and variability: Evidence from Manitoba, Canada. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 41(3), 625–639 (2009).

Dharani, M. K. et al. Review on crop prediction using deep learning techniques. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1767, 012026 (2021).