Abstract

With the aging population trend becoming increasingly pronounced, the health issues of elderly individuals living alone have become a focal point of societal concern. This study aims to investigate guardians of the elderly’s acceptance of intelligent care systems for the elderly. This system integrates millimeter-wave radar and image recognition technologies to monitor the health status of seniors in real time and automatically alert their children in emergency situations. To evaluate the market acceptance of this emerging technology, we employed a Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) approach and constructed an acceptance model for the intelligent care system. Survey data were collected from 386 respondents in China. The results indicate that users of this system are more concerned with task completion rather than ease of use. Enhancements in information trust significantly promote perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), and behavioral intention to use (BI). Individuals with higher risk perception sensitivity exhibit greater perceptions of the system’s usefulness and ease of use. Aesthetics emerged as a significant factor influencing PU, PEOU, and BI, second only to information trust. When the system is perceived as well-designed, it is also deemed acceptable. An aesthetically pleasing system is not only considered useful but also easier to use. Interestingly, opinions from social circles did not directly impact BI or PEOU. they only influenced perceived usefulness. Moreover, higher privacy security requirements correlate with lower perceptions of the system’s usefulness. Overall, improvements in perceived usefulness, information trust, and aesthetics significantly enhance user acceptance of the system. These findings provide theoretical support for developing more appealing intelligent care systems for the elderly and contribute new perspectives on understanding the key factors driving the adoption of such systems. Additionally, they enrich and refine the knowledge base within the TAM framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

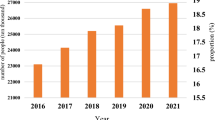

The aging population in China is becoming increasingly severe, and more families are facing the challenge of caring for elderly relatives, especially those living alone. According to the results of the Seventh National Population Census, China’s population aged 60 and above has reached as high as 264 million, accounting for 18.7% of the total population—and both the number of elderly people and their proportion in the population are continuing to rise. China is on the verge of entering a moderately aged society1. Home-based elderly care services supported by community resources are becoming the mainstream model of elderly care worldwide2,3. In China, a family- and community-centered elderly care model has emerged, with 90% of the elderly opting for home-based elderly care services and 7% receiving community-based care4. With the deepening of aging, the demand for home-based elderly care services is also growing rapidly.

In modern society, both the elderly and their children tend to prefer having their own “independent spaces.” The elderly generally desire to live independently with appropriate support rather than relying on institutional care5,6. Additionally, due to work or spousal reasons, some children are forced to live in different cities from their parents, further complicating face-to-face caregiving. Under the influence of multiple factors, Chinese family sizes are becoming smaller, and the traditional multi-generational household structure is changing. This transformation has led to the disintegration of the traditional model of elder care, where children personally take care of their elderly parents. The role of the family as the primary caregiver is also evolving7. Some researchers argue that the traditional model of family-based elder care is becoming unsustainable8. Family care is transitioning from a labor-intensive, traditional model to a smart model that leverages smart home technologies to enhance the quality and efficiency of care. Mitigating the social burden by ubiquitous usage of Intelligent Care systems for older adults are critically important.

Elderly individuals are at a high risk of death or serious injury due to falls, and this risk increases with age9. According to statistics from the CDC, one-third of adults aged 65 and older experience a fall each year, with 61% of these falls occurring at home10. The consequences of falls among the elderly can be severe, including fractures, head injuries, and traumatic brain injuries. More critically, a single fall can potentially lead to the death of an elderly person. Both internal and external factors contribute to the increased risk of falls among the elderly. Internal factors related to the elderly themselves, such as physiological aging, cognitive and functional decline, and non-adherence to fall prevention recommendations, make them more susceptible to falls. Additionally, external environmental and social factors also significantly influence the risk of falls. For example, living alone, the presence of obstacles such as stairs, and a lack of awareness among family members about fall risks11,12. Guardians of the elderly who are highly perceptive of potential risks can help reduce the probability of accidents occurring at home13. Therefore, implementing age-friendly home modifications to enhance the safety of the living environment is crucial for reducing the incidence of falls and other accidental injuries.

Obtaining a quick assistance after a fall reduces the risk of hospitalization by 26% and the death by 80%10. Therefore, it is crucial to promptly detect falls and quickly administer appropriate medical interventions. Preventing falls and ensuring timely detection and assistance after a fall have become key issues in the field of geriatric health. Fall detection sensor technology provides strong support for elderly health monitoring. Intelligent care systems are becoming indispensable support tools in modern households. Remote monitoring technologies14,15 and intelligent care systems16 can observe and record the activities of family members. Additionally, machine learning techniques can be employed to predict falls among the elderly17. Wearable devices can track various physiological health metrics, providing continuous health data18,19. The development and introduction of smart healthcare monitoring devices have made it more convenient to continuously monitor users’ health conditions20,21. These devices can continuously monitor one or more physiological parameters, and collect and store data, thereby helping users and their families better understand their health status and providing valuable diagnostic information for healthcare providers22.

Requena23 conducted a systematic review of the development of sensor technologies used to monitor falls in the elderly. Early technologies (2000–2005) utilized contact sensors24 and accelerometers25, primarily focusing on fall detection and simple activity monitoring26. The second phase (2006–2010) introduced triaxial accelerometers27 and wireless networks28, enabling advanced remote monitoring. During this period, sensors were capable of capturing real-time data, allowing for immediate intervention in cases of falls or changes in mobility29. The third phase (2011–2015) integrated advanced environmental sensors30, laying the foundation for the development and widespread adoption of applications that enable real-time health monitoring while preserving the independence of older adults in their daily activities. The fourth phase (2016–2024) has seen the expansion of monitoring capabilities through the integration of Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies31,32. Monitoring devices in this phase have also been functionally enhanced to capture interaction patterns in multi-resident environments33 and to provide proactive, personalized support services to the elderly34.

Research has shown that the use of smart monitoring systems at home can provide elderly individuals with a greater sense of security without disrupting their independent living35. Importantly, the presence of intelligent care systems not only offers 24/7 safety assurance for the elderly but also alleviates the economic and psychological burdens on family members8. Through such intelligent devices, younger generations can better safeguard their elderly relatives and reduce the wastage of social resources. Therefore, the use of intelligent care products may serve as an alternative or complementary solution to in-person caregiving, providing significant support for the independent living of the elderly36. In 2024, the global market value of medical intelligent nursing devices is estimated at approximately USD 4.5 billion and is projected to reach USD 10.2 billion by 203337. Among these, intelligent monitoring devices account for 40% of the market. Driven by continuous technological advancements, intelligent care systems are experiencing dynamic and sustained growth38.

Indeed, while there are numerous theoretical benefits, the widespread application of ICS also come with a series of challenges. The foremost challenge is conducting user acceptance surveys for ICS technology. User acceptance refers to an individual’s willingness to use or attempt to use a system or service, which is foundational for the successful promotion of any system39. For ICS in its optimization development phase, ensuring high user acceptance is crucial. To ensure that the final product is widely accepted by users, it is essential to fully consider the actual user experience during the technology application process. Factors such as the clarity and aesthetic appeal of interface design, the effectiveness of privacy protection measures, and psychological factors like trust in the provided information can all become barriers to user acceptance of care systems. Without systematic user acceptance surveys, it may be impossible to accurately identify which factors directly impact users’ willingness to use the system. This could result in failing to prioritize improvements on the most critical functions or optimizing user experience, ultimately leading to applications that do not meet user needs, wasting development time, and causing financial losses. Previous studies have applied the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explore the user’s attitudes toward the use of wearable health monitoring devices40, with most research focusing on the elderly as the primary respondents41,42. These studies primarily examined the acceptance of smart wearable systems43. However, limited attention has been given to the technology acceptance of non-contact Intelligent Care Systems (ICS) from the perspective of other user groups, such as the children or grandchildren of older adults. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate these users’ attitudes toward the acceptance of non-contact ICS products.

To understand users’ acceptance of ICS, it is essential to examine relevant user characteristics. Although market reports do not disclose detailed demographic data on the age distribution of ICS purchasers and users, it is possible to infer the demographic profile based on product positioning in China. ICS is primarily designed for remote monitoring of elderly individuals’ health status, daily activities, and fall detection, as well as for alerting caregivers when necessary. As a result, these data-collecting devices are typically installed in the rooms of older adults. However, the actual users of ICS are often the caregivers—typically the children or grandchildren of the elderly individuals. Based on this user profile, we infer that the majority of actual users are middle-aged children or younger adult grandchildren, generally ranging from 18 to 60 years old. Individuals within this age range usually have a stable income, purchasing power, and a relatively high level of acceptance of new technologies. They are capable of operating smart devices proficiently or can become proficient after minimal training. Nevertheless, due to demanding work schedules, they may be unable to provide constant physical companionship to elderly family members and thus rely on intelligent systems for remote caregiving. In addition, a small proportion of elderly individuals in good health—especially those who are living alone or as part of an empty-nest household—may purchase ICS for themselves or their spouses. Lastly, some long-term care institutions and community-based elderly care service centers may procure ICS in bulk for broader deployment.

Based on this, the theoretical scope of this study is explicitly limited to the decision-making context of guardians rather than the care recipients (the elderly), aiming to explore guardians’ acceptance and usage behavior toward ICS. This study seeks to understand guardians’ attitudes toward ICS and identify the factors that may influence their acceptance of such systems. Grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), this research constructs a comprehensive framework by expanding relevant variables to explain and predict users’ acceptance of this new care technology. Through surveys and empirical analysis, this study further reveals the status of ICS acceptance within the Chinese family context. The findings provide meaningful implications and insights for technology developers and promoters to enhance the acceptance of ICS among families with elderly members. These insights will contribute to the development of user-centered systems and improve the download and adoption rates of ICS.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to explore the following four key issues:

-

1.

The acceptance level of intelligent care systems among Chinese users.

-

2.

Specific factors that influence Chinese users’ behavioral intention to use toward these systems.

-

3.

The intrinsic relationships among these influencing factors.

-

4.

Key requirements and needs of users for intelligent care systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, the next section provides the theoretical background of the study. Then, Sect. “Proposed model” presents the proposed model, influencing factors, and hypotheses. Following that, Sect. "Questionnaire development and measurement" discusses the research methodology and experimental procedures. Finally, Sect. “Results” presents the research findings, Sect. “Discussion” discusses these results, and Sect. "Conclusion, research limitations, and future work" concludes with the implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

Related research

Intelligent Care Systems (ICS)

ICS is crucial for promptly reporting health threats to caregivers when they arise in elderly individuals. Existing research predominantly focuses on the technical aspects, particularly on methods for detecting falls among the elderly. Established detection methods include those based on wearable sensors, image recognition, and UWB (Ultra-Wideband) radar technologies.

Fall detection systems based on wearable devices predominantly utilize gyroscopes44, pressure sensors45,46, and accelerometers47,48. These inertial sensors are embedded in watches, belts, shoes, or clothing to collect data, which is then analyzed to determine the user’s posture49. Common fall detection algorithms include threshold-based methods and machine learning approaches50,51. Upon detecting a fall, an alert is triggered, and the system automatically responds by notifying caregivers. This technology is mature and offers high detection accuracy52. However, wearable devices may cause discomfort to elderly users, potentially limiting their daily activities. Additionally, these devices require frequent charging, and there is a risk of accidental activation or malfunction, which can significantly increase the difficulty for elderly individuals to learn and use the devices in their daily lives53.

Methods based on image recognition typically employ RGB cameras54 or depth cameras55 to capture human motion, determining whether a fall has occurred by analyzing images and videos. The core of these methods lies in collecting data via sensors and using advanced image processing algorithms for feature extraction and classification. Li56 proposed a novel fall detection algorithm that combines the extraction of local and global features, significantly enhancing detection accuracy. Additionally, Wu57 optimized visual detection algorithms by introducing a dual-modal network approach using weakly supervised learning, effectively reducing the workload of data annotation while improving the efficiency and practicality of the algorithm. These non-contact detection technologies not only eliminate the discomfort associated with wearable devices for elderly users but also provide more convenient and efficient solutions for fall detection. However, systems based on RGB cameras have certain limitations. For instance, camera performance is constrained under low-light conditions, and their field of view may be limited. Moreover, there is a risk of privacy breaches during the image acquisition process53.

Fall detection systems based on UWB (Ultra-Wideband) radar technology operate by emitting high-frequency pulse waves and receiving the electromagnetic wave signals reflected from the human body and the surrounding environment58. This system can distinguish fall events from other daily activities, such as walking, standing, sitting, and squatting based on differences in the received signals59,60. As a non-contact fall detection technology, UWB radar offers significant advantages in home safety monitoring for the elderly: it requires no wearable devices and provides enhanced privacy protection. However, in environments with multiple people or pets, the accuracy of UWB radar detection may be compromised due to interference. To address this issue, Lu61 proposed optimizing the installation location of the system, suggesting that UWB radars be installed on the ceiling to minimize external interference and thereby improve the accuracy of fall detection. Furthermore, He53 proposed a novel non-contact fall detector that integrates MEMS infrared sensors with radar sensors for dual detection, which has improved the accuracy of fall detection near the bed for elderly individuals.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is widely used to assess how likely consumers are to accept or reject new technologies37,62.TAM was proposed by Davis and is based on the Theory of Reasoned Action(TRA)39. The main advantage of adopting TAM is its simple structure. TAM only includes two core influencing factors—Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)39. This simplicity has also become the fatal weakness of TAM because it ignores many other determinants in the process of technology acceptance63. However, it allows researchers to integrate additional constructs based on specific research contexts and needs, thereby creating new theoretical models that more effectively elucidate technology acceptance behaviors in particular fields64. Therefore, TAM possesses significant advantages of adaptability, inclusiveness, and scalability, making it widely used for examining user acceptance of software systems and technology usage. These factors help predict if users will want to adopt new technologies. The model has been tested many times in healthcare and can effectively explain why people choose to use new technologies65,66.

To provide a more comprehensive explanation of users’ acceptance of new technologies, many researchers have tried to integrate various influencing factors into TAM. This has led to the development of extended models such as TAM262, The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)67,68, the expanded UTAUT269,70, and hybrid models combining TAM with other predictive variables. Hybrid models consider not only perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use but also introduce additional factors like social influence71, enjoyment72, unexpected perception13,73, information trust74,75, and aesthetics76. Moreover, the factors influencing intention continue to expand, further enriching our understanding of technology acceptance mechanisms. These models offer researchers tools to capture potential users’ opinions and attitudes more accurately. By incorporating a wider range of factors, these models provide deeper insights into what drives user acceptance and usage behavior.

Proposed model

Proposed model

Acceptance of a specific technology can be defined as the psychological determinants of a user’s behavioral intention to use the technology either after never experiencing it or after actually using it. The measurement projects in the field of health monitoring technology covered by existing research institutes have not mentioned non-contact intelligent health monitoring technology, which leads to the lack of tailor-made research factors in the acceptance studies of ICS. Therefore, based on the TAM model, this study extends and proposes a conceptual model applicable to the acceptance of ICS.

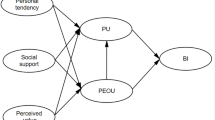

The model of this study consists of the original TAM model and five additional constructs, including Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Behavioral Intention to Use (BI), Perceived Accident (PAC), Information trust (IQU), Privacy Security (PSC), Social Influence (SIN), and Aesthetics (AES). BI is the dependent variable, and the other variables are independent variables. When adding variables, we mainly considered the following factors. ICS is designed for families with elderly people. Threats to the health of the elderly can trigger negative emotions in caregivers13,74,73, thereby affecting the behavioral intentions of users43. In various online systems, technical trust is an important factor in predicting users’ behavioral intentions 778. Users believe that the accuracy of the information provided by the system will affect the user’s behavioral intention75,78. The risk of privacy leakage is also a factor that users will definitely consider74,78. Furthermore, the viewpoints of others may influence the decisions of caregivers, and this factor needs to be taken into account in the research74. Finally, vision is the first intuitive perception. Aesthetics may affect users’ judgment of technical performance76,79. The theoretical basis for incorporating new factors into the TAM framework is introduced in detail in 3.2.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of intelligent care system acceptance, including hypotheses. We hypothesize that perceived accident, information trust, information privacy, social influence, and aesthetics significantly impact the acceptance of intelligent care systems. We propose that these factors, along with perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, collectively influence attitude. Specifically, the perceived accident, information trust, information privacy, social influence, and aesthetics serve as external stimuli. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are both processes of stimulus internalization. Attitude reflects the user’s response to the technology’s acceptability. Hence, perceived usefulness and ease of use are treated as the “Organism” in the model. “Response” represents the result of a behavioral intention formed after users receive external stimuli and undergo the internalization process.

Factors and hypotheses

Original TAM model

This study builds on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) proposed by Davis (1989) to construct a model of users’ acceptance of intelligent care systems. The TAM model has been validated in numerous studies and is capable of explaining individuals’ intentions to accept technology in intelligent care systems39. The foundational structure of the model includes Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Perceived Usefulness (PU), and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI). In this model, PU and PEOU positively influence BI. Moreover, PEOU can increase PU. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses.

H1

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

H2

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

H3

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU).

Perceived Accident(PAC)

In the Extended TAM model, “Perceived Accident” is not a standard term. The inclusion of PAC in TAM is mainly based on the theoretical basis of Risk Perception Theory and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). In this paper, by adding the variable of security risk belief, it further affects the core constructs of TAM – PU & PEOU, thereby exerting an effect on attitude and behavioral intention80. In high-risk scenarios such as transportation, medical care, and autonomous driving, safety risk becomes a key independent variable75. It has been shown in prior health technology research to influence users’ motivation to adopt preventive systems. It conceptually links to Perceived Usefulness, as a system perceived to reduce accidents is seen as more valuable. Perceived Accident, in the context of guardians (children or grandchildren) concerning the elderly living alone, refers to their view on the likelihood and severity of negative consequences resulting from falls. The level of guardians regarding elderly individuals’ risk of falling may influence their behavioral intention to use toward intelligent care systems, and their perceptions of the system’s usefulness and ease of use. After an elderly person experiences a fall, guardians tend to worry more about the possibility of future falls12. Experimental data show that guardians who perceive the severity of falls as higher also exhibit greater attention to improving home safety environments11. Groups with higher perceived vulnerability are more likely to intend to use health monitoring systems21. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Accident (PAC) and Perceived Usefulness (PU).

H5

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Accident (PAC) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H6

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Accident (PAC) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

Information trust (IQU)

“Information Trust” refers to the degree of confidence users have in the reliability, accuracy, and integrity of the information provided by a technological system or source. This trust impacts their willingness to rely on and use the technology for decision-making or other purposes81. In most contexts, there is a trustor, i.e., the person giving the trust, and a trustee, i.e., the person that is trusted. In the recent past, the trustee can also be a non-human object, often a technology of some sort77. When users trust the quality and reliable source of the information provided by the system, they are more likely to believe that the system can bring practical value, and thus the PU level is improved82. High trust means that users have confidence in the stability of the system, reduce the sense of usage obstacles, and thereby increase PEOU82. After trust is integrated into PU and PEOU, the classic TAM path remains unchanged, resulting in a positive correlation between IQU and BI. In the study on patients’ acceptance of remote diagnosis and treatment, trust significantly positively affects PU and PEOU, and influences the acceptance of use through BI. The credibility of information is very important in highly sensitive scenarios7.Consumers generally have an optimistic attitude toward intelligent detection technologies but also express concerns about the accuracy and security of these technologies83. Users’ trust in the information provided can significantly affect their acceptance of the technology, particularly among elderly users77. When users lack knowledge about the technology, they may question its accuracy. A lack of trust in the information provided can become a barrier to accepting the technology84,85. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7

Information trust (IQU) has a positive impact on Perceived Usefulness (PU).

H8

Information trust (IQU) has a positive impact on Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H9

Information trust (IQU) has a positive impact on Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

Privacy Security (PSC)

In this study, ‘Privacy Security’ refers to users’ apprehension about their personal information being accessed or damaged unauthorizedly, impacting their trust and willingness to participate with the technology. In health-related products, data security and protection are considered indispensable77. Privacy security is identified as one of the primary barriers to the acceptance of new technologies86,87. Users’ concerns primarily revolve around issues such as invasion of personal space (physical privacy), being monitored and intruded upon (psychological and social privacy), fear of access and misuse of personal information, and concerns about the security of data storage85,88. In the context of accepting intelligent products, privacy concerns make users cautious about using technology and sharing personal information. Privacy issues related to health information can even lead individuals to avoid certain healthcare services. In sensitive areas, if service providers fail to address customers’ privacy concerns, it can significantly negatively impact consumers’ attitudes and behaviors toward the service89. Users are unlikely to find usefulness in technologies that may infringe on their privacy, and concerns over user privacy can decrease perceived ease of use89. Alsyouf90 added privacy and security variables to TAM and found that security had a direct positive impact on BI, while privacy played a moderating role in the relationship between PEOU and BI. When users are worried about data leakage or system security vulnerabilities, they may question the functional value provided by the platform, thereby reducing the PU level. High-risk perception will increase users’ concerns during the usage process, thereby reducing PEOU. After considering privacy and security to form PU and PEOU, based on the TAM framework, PSC ultimately influences its usage attitude and behavioral intention. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses.

H10

There is a negative correlation between Privacy Security (PSC) and Perceived Usefulness (PU).

H11

There is a negative correlation between Privacy Security (PSC) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H12

Privacy Security (PSC) has a negative impact on Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

Social Influence (SIN)

“Social Influence” refers to the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new technology, which affects the individual’s intention to adopt and use the technology. This encompasses the impact of social norms and pressures from peers, colleagues, and family on technology acceptance decisions. Venkatesh and Davis62 first introduced the concept of “subjective norm” in the extended TAM2 model. “Subjective norm” refers to the extent to which an individual perceifies that significant others believe he/she should use a certain technology. They found that subjective norms act on technology acceptance behavior by influencing perceived usefulness and behavioral intent. That is to say, when individuals perceive that an important reference object believes they should adopt a new system, they will incorporate the opinions of the reference object into their own belief structure. The opinions of government, media, friends, and family can significantly influence people’s acceptance of intelligent products78. Chen91have found that elderly individuals’ willingness to use smart systems is largely affected by the views of others. However, some studies indicate that during the early stages of product or system development, users often lack information about utilizing such new technologies. In these cases, the relationship between social influence and users’ perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, and attitude may not be significant21,92. Incorporating SIN into the TAM framework can explain users’ behaviors during the process of technology acceptance more comprehensively, especially in technology application scenarios with strong social nature or high collaboration. For the intelligent care system, since it involves all family members, this leads us to believe that SIN has an impact on PU, PEOU and BI. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses.

H13

There is a positive correlation between Social Influence (SIN) and Perceived Usefulness (PU).

H14

There is a positive correlation between Social Influence (SIN) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H15

Social Influence (SIN) has a positive impact on Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

Aesthetics (AES)

“Aesthetics” refers to the visual appeal and design attractiveness of the technology interface, which can influence users’ satisfaction and their willingness to accept and use the technology. It encompasses elements such as layout, color scheme, and overall user interface design that contribute to a positive user experience. Aesthetics have become an important dimension in the field of user experience76. Existing research indicates that aesthetics influence users’ perceptions of a product’s usefulness and ease of use93. The visual aesthetics of an interface are a strong determinant of user satisfaction and enjoyment94,95. Cyr96 found that visual design aesthetics significantly influence perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Aesthetics have a significant positive impact on perceived usefulness79,97, while their effect on perceived ease of use is present but less significant98. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses.

H16

There is a positive correlation between Aesthetics (AES) and Perceived Usefulness (PU).

H17

There is a positive correlation between Aesthetics (AES) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H18

There is a positive correlation between Aesthetics (AES) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

Questionnaire development and measurement

Materials

This study employed an advanced intelligent care systems tailored for the elderly market in China. The system integrates image recognition technology with radar sensors to create a non-contact fall detection solution. Specifically, it analyzes data collected by sensors to monitor the activity states of elderly individuals (standing, lying, sitting, squatting). Upon detecting a fall, the system promptly calls the primary caregiver for assistance. Beyond fall detection, the system also records breathing and heart rate during sleep and supports remote video calls with family members. All sensors are housed within a plastic casing designed for aesthetic appeal and portability. The casing features only three physical call buttons to minimize accidental operations by the elderly, while all settings can be managed via a companion app designed for their children. The interface used in the guardian (children or grandchildren) mainly includes viewing the health status of the elderly, the daily activities of the elderly, and remote videos. When the elderly fall, the system will automatically call the guardian. The application program interface and sensors of QLKH Intelligent Care Systems are shown in Fig. 2.

Questionnaire development and Pre-testing

The questionnaire was structured into two main sections. Section one collected basic demographic information from respondents, including their gender, age, educational background, and experience with similar technologies. Section two focused on evaluating the system across eight dimensions, including PU、PEOU、PAC、IQU、PSC、SIN、AES、BI. All dimensions utilized in our model have been validated in various research contexts. For each dimension, at least three standardized questions were formulated. Responses to these evaluative questions were measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (7). The questionnaire also included reverse-phrased items. These items are designed to promote careful consideration, helping to filter out less thoughtful answers.

The survey consisted of four steps. First, participants were randomly recruited online and on-site. All eligible respondents had an equal probability of being selected, which helps minimize sampling bias and enhance the objectivity of the data collection process. We aimed to ensure diversity in participants’ demographics by distributing the questionnaire widely across different regions in China through multiple online platforms and community groups. As a result, the final sample includes participants of varied age groups, genders, educational levels, and geographic locations, which provides a reasonably diverse foundation for analysis. Participants will be briefed on the purpose of the study, the expected time investment, and the compensation. They read this introduction to the experiment and signed an informed consent form. Next, participants accessed the task page by clicking on a provided link or scanning a QR code, where they read the task instructions. Then, they watched a 2-minute introductory video about the intelligent care system to familiarize themselves with it. The 2-minute video provides a comprehensive introduction to the product and system. The video content starts from downloading and installing, then the APP operation interface displayed in the video shows the entire operation process. After the user performs each operation, the APP interface will provide feedback on the user’s operation. After 2-minute video watching, we provide an App download link to participants. Participants can experience the QLKH application or choose to skip the software experience step directly (the experimenter did not force every user to complete short hands on experience), and then we invite participants to click on the questionnaire link to complete the online survey. The questionnaire is filled in anonymously, and no sensitive personal information is involved in the filling process to ensure that the privacy of participants is protected. This work was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Nursing and Behavioral Medicine Research of the School of Nursing, Central South University (Ethics Review number: E202258). Data for this study was collected from August 5 to August 16, 2023.

In the pre-test phase, we engaged five domain experts and thirty-five randomly selected participants to review the questionnaire. Experts have deeply experienced this system and are responsible for evaluating content validity, ensuring the theoretical rigor and conceptual coverage of the this study. Random participants mainly learned about this system by watching videos. Their feedback is used for face validity assessment, verifying the comprehensibility and suitable of the items. Based on the feedback received from both experts and participants, particularly regarding the feedback for wording of the questions, we made detailed revisions and adjustments. The finalized questionnaire can be found in Appendix A.

Results

This study received a total of 400 questionnaires and conducted data analysis using SPSS and AMOS software. After applying screening criteria, 14 responses were excluded due to completion time under 1 min (n = 2), excessive answer repetition (over 85% similarity across items, n = 9), missing data (n = 0), and statistical outliers identified via SPSS (n = 3). This resulted in a final dataset of 386 valid responses used for analysis. Our questionnaire contains 32 items, requiring a minimum of 320 responses. We successfully collected 386 valid responses, which exceeds the threshold and satisfies statistical requirements for robust analysis99,100. Thus, all subsequent analyses are based on these 386 valid datasets.

Sample characteristics

The demographic information of the research participants is presented in Table 1, providing an overview of the characteristics of the sample. The demographic results show that the participants in this survey were 146 males and 240 females. The majority of participants are concentrated in two age groups, 18 to 30 years old (60.06%) and 31–50 years old (20.21%). Randomly recruited participants fit the age profile of the primary purchasers of the product and the primary users of the system. These participants are guardians of the elderly (children or grandchildren). The demographic results show that the most participants held a bachelor’s degree or higher, accounting for 90.67% of the sample. Participants gained some understanding of the test product either by watching our introductory video or through personal experience, with 84.46% of users having some knowledge of the product.

Normality test

The normality of the data was assessed using kurtosis and skewness tests. Ideally, in a normality test, both kurtosis and skewness should approach zero101. However, since real-world data rarely perfectly conform to a normal distribution, it is generally accepted that if the absolute value of skewness is less than 3 and the absolute value of kurtosis is less than 10, the data can be considered approximately normally distributed102. As shown in Table 2, the skewness and kurtosis values indicate that the data from this survey conform to a normal distribution.

Reliability analysis

Reliability analysis is a statistical process used to assess the consistency and stability of a measurement tool or test. Ensuring the quality of measurement results is a prerequisite for subsequent analyses. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the internal consistency of each dimension. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater reliability. The reliability analysis results are presented in Table 3. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.907, and the Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale ranged from 0.819 to 0.955, all exceeding 0.8. These high values indicate that the scales used in this study have excellent internal consistency and reliability, making them suitable for further Validity Analysis.

Validity analysis

Validity analysis assesses whether a measurement tool or test accurately measures the concept or attribute it is intended to measure. To assess the questionnaire’s validity, we conducted both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) were used to evaluate the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that variables are inter-correlated, while the KMO value was 0.916, well above the threshold of 0.7, suggesting excellent suitability for factor analysis. These results confirm that the questionnaire data are highly appropriate for further analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis

In the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), we used rotated factors for principal component extraction103. After rotation, these 8 factors were clearly defined. The EFA results indicate that all items are loaded onto their respective dimensions with factor loadings greater than 0.6, as shown in Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis

For confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the survey data were imported into Amos to construct a variable model for validity testing. According to the results presented in Table 5, All indicator factor loadings should be significant and exceed 0.7, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for each dimension exceeded 0.5, and the Composite Reliability (CR) values were all above 0.8, meeting the criteria for convergent validity104. These findings collectively indicate that each dimension exhibits good convergent validity and composite reliability, confirming that the model is suitable for further research analysis.

Discriminant validity analysis

Based on the analysis results presented in Table 6, the standardized correlation coefficients between each pair of dimensions in this discriminant validity test were all less than the square root of their respective AVE (Average Variance Extracted) values. This indicates that each dimension has good distinctiveness from the others, confirming that the measurement variables have passed the discriminant validity test.

Model fit analysis

Based on the model fit test results presented in Table 7, the CMIN/DF is 2.488, which falls within the desirable range of 1–3. The RMSEA is 0.062, indicating a good fit within acceptable limits. Additionally, the NFI, RFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI all achieved values above 0.9, reflecting excellent levels of fit105. These results collectively suggest that the theoretical model fits the actual data well.

In this analysis, Pearson correlation analysis was employed to explore the relationships between various variables. According to the analysis results presented in Table 8, out of the 18 hypotheses tested in this study, 12 were supported by the sample data, while 6 were not supported (refer to Fig. 3). Specifically, when the absolute value of the t-value (C.R.) is greater than 1.96 and the p-value is less than 0.05, it indicates that the path influence between latent variables is significant, and the hypothesis is considered valid. Based on this criterion, the unsupported hypotheses are as follows.

H2

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

H6

There is a positive correlation between Perceived Accident (PAC) and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

H11

There is a negative correlation between Privacy Security (PSC) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H12

Privacy Security (PSC) has a negative impact on Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

H14

There is a positive correlation between Social Influence (SIN) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU).

H15

Social Influence (SIN) has a positive impact on Behavioral Intention to Use (BI).

*: p < 0.05;**: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study proposes an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to investigate the factors influencing users’ acceptance of intelligent care systems. By formulating and validating hypotheses, we deepen the understanding of the original TAM constructs—Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), and Behavioral Intention to Use (BI)—and reveal the significant impacts of five additional constructs: Perceived Accident (PAC), Information trust (IQU), Privacy Security (PSC), Social Influence (SIN), and Aesthetics (AES). Our findings confirm that six critical factors significantly influence user acceptance. Overall, our data support the Intelligent Care System Acceptance Model, with 12 hypotheses accepted and 6 rejected.

Original TAM model

The study confirms PU as one of the most powerful predictors of technology acceptance. There is a significant positive correlation between PEOU and PU (β = 0.344, p < 0.001), validating that for a technology to be deemed easy to use, it must also be useful106. The hypothesis that PU influences BI was strongly supported (β = 0.369, p < 0.001). However, PEOU does not have a significant direct impact on BI (β = 0.026, p > 0.05). This discovery is different from the traditional TAM model, where PEOU usually directly affects BI. Instead, consistent with previous research by Klingberg107, Alsisi108, and Park109. We guess that PEOU affects BI through PU. Thus, this study speculates that this is related to the type of system. Users of health monitoring systems are more concerned with the successful completion of tasks rather than ease of use. This is particularly true for fall detection technologies that pertain to the health of elderly individuals.

Specifically, this may be because guardians of the elderly are more concerned with the practical utility of technology rather than the simplicity of operation. When guardians believe that the use of ICS can effectively achieve the goal of elderly living independently at home (improving the quality of life of family members, clearly understanding the health level of elderly, strengthening intergenerational communication, etc.), they may be more willing to try and continue to use this system. This positive usefulness may enhance users’ confidence, making them believe that using a healthcare system is a worthwhile investment. On the other hand, if users feel that using a health care system will not consume too much time and effort, or if the system’s interface is user-friendly and easy to operate, resulting in less burden during use, this may make them believe that the system can help them. And we speculate that the guardian has a high level of education and acceptance of digital technology, so they will not give up using this system even it is difficult to operate. We suspect that this is the reason why PEOU has no significant impact on BI. A higher PEOU means that users believe that they do not need to spend a lot of resources (such as time and effort) to get benefits, thereby enabling them to achieve higher PU. A higher PU means that users perceive the system to be helpful for the health management of the elderly, which can further enhance their intention to use the system.

Information trust (IQU)

IQU emerged as a strong determinant of both PU and PEOU (β = 0.439, p < 0.001; β = 0.457, p < 0.001). IQU is positively correlated with BI (β = 0.439, p < 0.001). This discovery strengthens the expansion logic of exogenous variables in the TAM model. In health monitoring systems, users are most concerned about the accuracy and reliability of information. IQU positively correlates with BI(β = 0.351, p < 0.001), indicating that improving product performance regarding information accuracy can enhance perceptions of usefulness and ease of use. While rarely mentioned in TAM or UTAUT models, information accuracy significantly influences usefulness, ease of use, and behavioral intention to use in practical applications. This is consistent with Felber110, qualitative research highlighting stakeholders’ emphasis on reliability. It significantly influences practical applications of PU, PEOU, and BI. The research concludes that IQU should be considered as a predictive indicator. We have also verified from a quantitative perspective of investigation and research that ‘improving the performance of products in terms of information accuracy may make users more willing to try and continue using this system.

Specifically, in the context of healthcare, accurate information feedback not only enhances users’ confidence in system operation, but also strengthens their recognition of the actual effectiveness of the system, thereby promoting the formation of usage intention. If the guardian believes that the system can provide real and effective data, they are more likely to believe that the system can improve the user’s predicament. For system developers, improving information accuracy should be the core strategy for optimizing user experience and promoting technology adoption, emphasizing the decisive role of “data quality” in the acceptance process of healthy technology. We suggest that R&D personnel should focus on improving the accuracy of sensors, reducing system false alarms, or setting up information verification mechanisms. Guardians are often the “recommenders” and “promoters” in technology adoption progress. Their trust in the accuracy of information is the key that drives them to use the system. System developers need to ensure that guardians feel the information they obtain is reliable.

Aesthetic (AES)

AES, aside from IQU, is a significant factor influencing PU and PEOU. It encompasses the aesthetic appeal of the product and the visual experience of app interfaces. When applications or products are perceived as aesthetically pleasing, they are also considered more useful and easier to use. This aligns with findings by Li98, who noted a strong correlation between aesthetics and trust. Therefore, aesthetics should be considered as a predictive indicator.

This study confirms that aesthetics (AES) is a significant predictive factor within the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), especially in the context of elderly healthcare systems. AES has a significant positive influence on perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), and behavioral intention (BI) (β = 0.204, p < 0.001; β = 0.283, p < 0.001; β = 0.274, p < 0.001). It encompasses both the aesthetic appeal of the product and the visual experience of application interfaces. We found that when applications are more aesthetically designed, users are more likely to perceive them as useful (PU) and easy to use (PEOU). This finding highlights the crucial role of visual interface design in shaping users’ cognition and behavioral intention, indicating that aesthetics is not merely a superficial attribute but a functional factor that influences technology acceptance96. This is similar to the findings of Li98, who noted a strong correlation between aesthetics and trust in mobile commerce. Therefore, aesthetics should be considered a predictive indicator.

Moreover, this study presents some novel insights. While previous research has predominantly focused on younger users for education applications, our study extends the role of aesthetics to elderly healthcare systems, particularly among guardians who make usage decisions on behalf of older adults. For this group, high-quality visual design not only enhances their perceptions of professionalism but may also strengthen trust and willingness to adopt the system. This suggests that in high-risk contexts such as healthcare, aesthetics can influence technology evaluation by triggering emotional trust, which is a more complex cognitive-to-emotional process. Furthermore, although previous studies often treated aesthetics as a secondary or indirect factor, our findings reveal that AES has a significant and direct effect on both PU and PEOU. This suggests its potential to be elevated to a core construct within the TAM framework. This finding contributes to the theoretical development of technology adoption models by emphasizing the growing importance of design-related variables (such as visual experience), especially in care scenarios that require high levels of trust and empathy.

From a practical standpoint, we recommend that system developers incorporate aesthetic interface design from the early stages of development—not as an ornamental addition, but as a strategic design element that enhances usability and ease of use.

Perceived accident (PAC)

PAC shows a positive correlation with PU and PEOU (β = 0.096, p < 0.05; β = 0.131, p < 0.05), but has no significant effect on BI (β = 0.086, p > 0.05). The data results validated the impact path of PAC as an external variable on the core factors of TAM. In the context of the use of elderly health care systems, PAC has a significant positive impact on both PU and PEOU. This finding is consistent with existing literature11,111, supporting that in high perceived risk scenarios, users are more inclined to value the functional value and ease of operation brought by technology. This indicates that when caregivers perceive that elderly living alone face a higher risk of falls or sudden health events, they are more likely to recognize the potential of technological systems in risk mitigation. However, there is significant inconsistency in the research on the relationship between PAC and BI112. We need discuss possible cultural and contextual explanations for this divergence in the Chinese caregiving environment. We believe this is related to the subject of the investigation (whether it is a guardian or an elderly). We speculate that in the context of elderly care, although risk perception can enhance the PU and PEOU of the system to a certain extent, it is not sufficient to directly drive caregivers’ willingness to use it. As mentioned earlier, PU is a key factor influencing BI. Individuals with higher perceived risk tend to have a greater PU and PEOU. Compared to those with lower perceived risk, individuals who believe that the elderly living alone face higher health risks are more likely to perceive that care systems can play a role in mitigating the risk of sudden death among the elderly living alone. However, this new technology of care systems may not have gained sufficient trust from the participants, leading to higher requirements for PU and PEOU among those with high-risk perceptions.

The reason why we speculate that PAC is not related to BI is that in the context of family health care, guardians’ concerns about health events such as falls among the elderly are more manifested as moral responsibility or emotional concern rather than a clear motivation for the use of technology. This means that PAC stimulates “consciousness” or “alertness”, but is not sufficient to be directly transformed into “behavioral intention”. We suggest that when promoting the system, a “risk-averse” information strategy can be adopted, emphasizing the role of the system in preventing falls or sudden health problems, thereby enhancing users’ perception of the value of the system. Furthermore, although users consider the system useful (PU) and easy to use (PEOU), they still do not show a strong intention to use it (BI). This indicates that relying solely on functional design and operational convenience is not sufficient. Developers should consider adding emotional trust building mechanisms, such as reliable brand endorsement, usage safety feedback mechanisms, professional nursing staff recommendation systems, etc., to smooth out the closed-loop path from cognition to action.

Privacy security (PSC)

PSC does not directly affect PEOU and BI(β = 0.064, p > 0.05; β = 0.055, p > 0.05), but has a relatively significant negative correlation with PU(β=−0.116, p < 0.01). This suggests that users are less concerned about privacy risks associated with video recording in intelligent care systems. Although the impact of PSC on BI cannot be entirely ruled out78.

The lack of significant relationship between PSC and BI indicates that for elderly caregivers, although they are concerned about data privacy issues, this does not directly affect their willingness to use the system. This may be because in the high-risk elderly population, health monitoring is seen as an urgent or necessary need, so caregivers are more likely to adopt a pragmatic attitude that balances functionality and privacy protection113. This behavioral motivation reflects that privacy issues may be intentionally ignored or tolerated under the drive of emotional or moral responsibility.

There is no significant relationship between PSC and PEOU, indicating that although users have privacy concerns about the system, they do not consider it as part of operational difficulty or usage barriers. In other words, even if users do not trust the system, they can still consider it easy to use. This indicates that PSC and PEOU may be independent dimensions of each other. Privacy concerns are a form of “risk awareness” rather than an evaluation of the difficulty of using the system.

The negative correlation between PSC and PU indicates that individuals who are highly concerned about privacy consider the usefulness of this system to be low. Xiao114 pointed out that privacy concerns are obstacles in the adoption process of health monitoring technology. Privacy risks may weaken users’ recognition of the system. If users suspect that the system may leak sensitive health data or lack confidence in data access and control, they may believe that the system cannot truly improve care efficiency and instead has exposure risks. Perceived privacy and security have no significant impact in our model, which contrasts with many studies indicating that privacy issues are a key barrier. There is a possibility that the existing system has already ensured privacy and security, allowing elderly and their families to use it with confidence. For example, videos are only stored on local SD memory cards, and authorization from the first caregiver is required before others can view the videos. Before each video viewing, the app automatically scans to determine if there are any privacy related scene involved. Therefore, users are confident in the privacy and security of the product, resulting in a low correlation between privacy and security and usage intention. Therefore, users may view it as a ‘basic function’ rather than a ‘decision variable’, leading to a weakened direct impact of privacy and security on usage intentions.

This result also reminds technology developers to turn to other user experience pain points after privacy optimization. In terms of improving privacy protection, the privacy protection of the system can be used as a promotional factor. Enable users to directly experience the privacy explanation and functional demonstration of the system, help them understand how the system protects privacy, and strengthen trust and value perception through professional explanations. In addition, theoretically, in family scene or elderly care fields, model design should consider modeling PSC as a antecedent variable of PU.

Social influence (SIN)

“The hypothesis that SIN positively influences BI and PEOU” was not supported (β=−0.050, p > 0.05; β=−0.006, p > 0.05). This indicates that opinions from social circles (peers, family members, media) do not directly impact intentions to use intelligent care systems. In the context of the use of elderly ICS, the direct driving effect of SIN on user adoption intention may be replaced by other factors. This finding is not entirely consistent with previous studies emphasizing the positive impact of social norms, family opinions, or professional advice on users’ adoption of technology37. We make speculations from three aspects. A possible explanation for the insufficient impact of SIN on BI and PEOU found in this study is that some participants are early adopters of new technologies, and they are influential to other potential adopters21. Early adopters are often younger and more educated, as reflected in our sample (18–30 years: 65.54%; bachelor’s degree or higher: 90.67%)115. Additionally, SIN plays a lesser role in healthcare decisions, where perceptions are more likely influenced by professionals like doctors and nurses. Finally, the minimal influences of SIN for older users can be attributed to IQU discussed earlier. Elderly users desire greater data accuracy and security, making them less willing to share their personal sensitive health data with peers, friends, or relatives92. However, we found that SIN shows a positive correlation with PU (β = 0.100, p < 0.05). SIN can indirectly affect BI through PU.

This discovery has implications for the extension of the TAM model. In home scene or elderly care fields, model design should consider modeling SIN as an antecedent variable of PU. From a practical application perspective, in the process of promoting the system, emphasis should be placed on improving PU and PEOU, rather than relying solely on social reputation or advertising, especially in high-risk, low fault tolerance medical care contexts.

Conclusion, research limitations, and future work

Conclusion

Our research aims to develop and test an extended TAM model (An Extended Technology Acceptance Model) to better understand the acceptance and behavioral intentions of family members (mainly children and grandchildren of elderly) towards using elderly ICS. his study introduces five external variables based on TAM, which are the PAC、IQU、PSC、SIN、AES, and systematically analyzed their impact on the core variables of TAM.

This study focuses on addressing two key limited areas of existing research at the theoretical level. On the one hand, existing research on elderly health care systems mostly focuses on the perspective of the elderly. However, the system is a shared system used by elderly and other family members. The unique cognitive mechanism of elderly guardians (children and grandchildren) as direct users still needs to be explored. On the other hand, it theoretically enhances the explanatory power and adaptability to specific contexts of mature TAM models, further supplementing the theoretical model. This study provides new perspectives for broader technological acceptance research. Eventually, our research provides actionable insights for system designers, technology developers, and policy makers who aim to increase product adoption and improve user centered design.

The results enrich the structure of the TAM model and propose a theoretical path that is more suitable for the application scenarios of elderly ICS technology in home environments. Specifically, IQU and AES have significant positive effects on PEOU, PU, and BI, indicating that they are important antecedent variables with theoretical significance in technology adoption. It is worth noting that although PAC significantly improved PEOU and PU, it had no direct impact on BI, PAC primarily enhances cognitive assessment rather than directly driving behavior. Furthermore, there is a negative relationship between PSC and PU, while the impact of SIN on PU is relatively weak. PSC has no effect on both PEOU and BI. Similarly, SIN has no effect on either PEOU or BI. This result challenges the common assumptions about social impact and privacy concerns in traditional research, indicating that there may be contextual differences in the mechanisms of action between SIN and PSC in the sensitive field of elderly health care.

At the practical level, the results of this study have important practical guidance value for developers of elderly ICS, medical service providers, and system promoters. Especially, understanding the unique concerns and preferences of elderly guardians (rather than elderly users) can help improve product functionality, interface design, and communication strategies. The significant positive effects of IQU and AES on all key variables of TAM indicate that attention should be paid to the accuracy of information content and the aesthetic performance of user interface design from the early stage of system development. Valuing information accuracy can be reflected in improving the accuracy, transparency, and interpretability of sensors, reducing system false alarms, and increasing the establishment of information verification mechanisms. The emphasis on interface design should be reflected in not treating “AES” as a decorative add-on, but rather as a strategic design element to enhance usability and user-friendliness. For instance, important alert messages could be highlighted with more prominent colors and fonts to improve information readability. Ordinary notifications could include timestamps to enhance users’ trust and perception of information accuracy. Moreover, aesthetic design attracts users and adds value to the system. Clear interface layouts and operation methods that align with user habits can increase users’ understanding of application functionalities, thereby enhancing their perceptions of the system’s usefulness and user-friendliness. The significant effect of PAC on PU and PEOU indicates that a “risk averse” information strategy can be adopted for system promotion. Emphasize the role of the system in preventing falls or responding to sudden health issues in promotion, thereby enhancing its perceived value. System developers should balance functionality and emotional support in interface design. For instance, enhancing health information feedback, higher system controllability, and friendly interaction mode can significantly boost user engagement.

Research limitations, and future work

This study extends the TAM structure and enriches empirical research on user acceptance of ICS. However, it also has limitations. In this study, we recruited participants by means of random sampling. Furthermore, we mainly focus on young participants, who are usually more familiar with digital technologies and more inclined to adopt new technologies. Therefore, the research results may not fully reflect the acceptance and usage habits of ICS among different age groups in China. Stratified sampling will be used in future studies to further enhance generalization. In addition, during the actual investigation and testing, we did not mandate participants to use the ICS in the pre testing stage, but instead replaced it with watching videos. Because the video can provide a detailed display of the entire system operation process and feedback. Learning about the system through videos is more efficient, but it sacrifices participants’ hands on experience in a way. Future research should consider incorporating brief system trial sessions to allow users to directly experience the technology before providing feedback. Finally, the model is based on TAM. Although its simplicity indicates robustness, it also exposes the possibility of overlooking other potential variables, such as self-efficacy and perceived value, which were not considered in this study and may be a direction for future research. Future studies may build on this research by testing additional variables or developing hybrid models that better capture the complexity of user acceptance in intelligent care technologies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

China, N. B. o. S. o. The 7th National Population Census Bulletin (No.5) – Age Composition, (2021). https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-05/13/content_5606149.htm

Bangerter, L. R., Fadel, M., Riffin, C. & Splaine, M. The older Americans act and family caregiving: perspectives from federal and state levels. Public. Policy Aging Rep. 29, 62–66 (2019).

LaW, M. o. HGovernment of Japan,. (2020).

Health, D. o. A. Aging is not just a problem for older people, (2021). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/lljks/s7786/202110/44ab702461394f51ba73458397e87596.shtml

Fausset, C. B., Kelly, A. J., Rogers, W. A. & Fisk, A. D. Challenges to aging in place: Understanding home maintenance difficulties. J. Hous. Elder. 25, 125–141 (2011).

Eckert, J. K., Morgan, L. A. & Swamy, N. Preferences for receipt of care among community-dwelling adults. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 16, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J031v16n02_04 (2004).

Shafei, I., Khadka, J. & Balasubramanian, M. Smart homes: pioneering age-friendly environments in China for enhanced health and quality of life. Front. Public. Health. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1346963 (2024).

Ho, A. Are we ready for artificial intelligence health monitoring in elder care? BMC Geriatr. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01764-9 (2020).

WHO. Falls fact sheet. (2021).

Daher, M., Diab, A., Najjar, M. E. B. E., Khalil, M. A. & Charpillet, F. Elder tracking and fall detection system using smart tiles. IEEE Sens. J. 17, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2016.2625099 (2017).

Ang, S. G. M., O’Brien, A. P. & Wilson, A. Investigating the psychometric properties of the Carers’ Fall Concern instrument to measure carers’ concern for older people at risk of falling at home: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 15 https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12338 (2020).

Ang, S. G. M., O’Brien, A. P. & Wilson, A. Carers’ concerns about their older persons (Carees) at risk of falling - a mixed-methods study protocol. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3632-6 (2018).

Songthap, A., Suphunnakul, P. & Rakprasit, J. Factors affecting home environmental safety management for fall prevention for older adults in Northern Thailand. BMC Geriatr. 23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04419-7 (2023).

Wang, H., Qin, D., Fang, L., Liu, H. & Song, P. Addressing healthy aging in China: practices and prospects. Biosci. Trends. 18, 212–218. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2024.01180 (2024).

Hyvari, S., Elo, S., Kukkohovi, S. & Lotvonen, S. Utilizing activity sensors to identify the behavioural activity patterns of elderly home care clients. Disabil. Rehabilitation-Assistive Technol. 19, 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2022.2110951 (2024).

Wong, A. M. K. et al. Technology acceptance for an intelligent comprehensive interactive care (ICIC) system for care of the elderly: A Survey-Questionnaire study. Plos One. 7 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040591 (2012).

Zhou, Z., Wang, D., Sun, J., Zhu, M. & Teng, L. A machine Learning-Based prediction model for the probability of fall risk among Chinese Community-Dwelling older adults. Computers Inf. Nursing: CIN. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000001202 (2024).

Galambos, C., Craver, A., Pelts, M. D., Jun, J. & Rantz, M. LIVING WITH INTELLIGENT SENSORS: OLDER ADULT AND FAMILY MEMBER PERCEPTIONS. Gerontologist 56, 287–287 (2016).

Dollard, J. et al. Patient acceptability of a novel technological solution (Ambient intelligent geriatric management System) to prevent falls in geriatric and general medicine wards: A Mixed-Methods study. Gerontology 68, 1070–1080. https://doi.org/10.1159/000522657 (2022).

Lunney, A., Cunningham, N. R. & Eastin, M. S. Wearable fitness technology: A structural investigation into acceptance and perceived fitness outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 65, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.007 (2016).

Beh, P. K., Ganesan, Y., Iranmanesh, M. & Foroughi, B. Using smartwatches for fitness and health monitoring: the UTAUT2 combined with threat appraisal as moderators. Behav. Inform. Technol. 40, 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2019.1685597 (2021).

Bloss, R. Wearable sensors bring new benefits to continuous medical monitoring, real time physical activity assessment, baby monitoring and industrial applications. Sens. Rev. 35, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/sr-10-2014-722 (2015).

Requena, C., Plaza-Carmona, M., alvarez-Merino, P. & Lopez-Fernandez, V. Technological applications to enhance independence in daily activities for older adults: a systematic review. Front. Public. Health. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1476916 (2024).

Orr, R. J. & Abowd, G. D. in CHI’00 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems. 275–276.

Mathie, M. J., Coster, A. C., Lovell, N. H. & Celler, B. G. Accelerometry: providing an integrated, practical method for long-term, ambulatory monitoring of human movement. Physiol. Meas. 25, R1 (2004).

Sixsmith, A. & Johnson, N. A smart sensor to detect the falls of the elderly. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 3, 42–47 (2004).

Bourke, A. K., O’brien, J. & Lyons, G. M. Evaluation of a threshold-based tri-axial accelerometer fall detection algorithm. Gait Posture. 26, 194–199 (2007).

Alemdar, H. & Ersoy, C. Wireless sensor networks for healthcare: A survey. Comput. Netw. 54, 2688–2710 (2010).

Virone, G. et al. Behavioral patterns of older adults in assisted living. IEEE Trans. Inf Technol. Biomed. 12, 387–398 (2008).

Kaye, J. A. et al. Intelligent systems for assessing aging changes: home-based, unobtrusive, and continuous assessment of aging. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Social Sci. 66, i180–i190 (2011).

Muangprathub, J. et al. A novel elderly tracking system using machine learning to classify signals from mobile and wearable sensors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 12652 (2021).

Huang, Z., Li, J. & He, Z. Full-coverage unobtrusive health monitoring of elders at homes. Internet Things. 26, 101182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2024.101182 (2024). https://doi.org:.

Ramos, R. G., Domingo, J. D. & Zalama, E. Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Daily human activity recognition using non-intrusive sensors. Sensors 21, 5270 (2021).

Igarashi, T., Nihei, M., Inoue, T., Sugawara, I. & Kamata, M. Eliciting a user’s preferences by the self-disclosure of socially assistive robots in local households of older adults to facilitate verbal human–robot interaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 11319 (2022).

Pol, M. et al. Older People’s perspectives regarding the use of sensor monitoring in their home. Gerontologist 56, 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu104 (2016).

van Hoof, J., Kort, H. S. M., Rutten, P. G. S. & Duijnstee, M. S. H. Ageing-in-place with the use of ambient intelligence technology: perspectives of older users. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 80, 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.02.010 (2011).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B. & Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27, 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540 (2003).

VMR. Medical Intelligent Nursing Device Market Insights, (2025). https://www.verifiedmarketreports.com/product/medical-intelligent-nursing-device-market/?utm_source=chatgpt.com/

Davis, F. & Perceived Usefulness Perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13, 319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008 (1989).

Wang, Y. et al. The willingness to continue using wearable devices among the elderly: SEM and FsQCA analysis. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02336-8 (2023).

Alaiad, A. & Zhou, L. The determinants of home healthcare robots adoption: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 83, 825–840 (2014).

Postema, T., Peeters, J. & Friele, R. Key factors influencing the implementation success of a home Telecare application. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 81, 415–423 (2012).

Li, J., Ma, Q., Chan, A. H. S. & Man, S. S. Health monitoring through wearable technologies for older adults: smart wearables acceptance model. Appl. Ergon. 75, 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2018.10.006 (2019).

Bourke, A. K. & Lyons, G. M. A threshold-based fall-detection algorithm using a bi-axial gyroscope sensor. Med. Eng. Phys. 30, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.12.001 (2008).

Kim, I. et al. Implementation of a real-time fall detection system for elderly Korean farmers using an insole-integrated sensing device. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 48, 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10739149.2019.1648293 (2020).

Wei, L., Changhong, W., Stevens, M. C., Redmond, S. J. & Lovell, N. H. Low-power operation of a barometric pressure sensor for use in an automatic fall detector. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference 2016, 2010–2013 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/embc.2016.7591120

Nahian, M. J. A. et al. Towards an Accelerometer-Based elderly fall detection system using Cross-Disciplinary time series features. Ieee Access. 9, 39413–39431. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3056441 (2021).