Abstract

Rosacea is treated among others by doxycycline and sodium bituminosulfonate dry substance (SBDS). We addressed the molecular mechanism(s) underlying the therapeutic benefit of SBDS and doxycycline. Therefore, we investigated whether SBDS or doxycycline regulates the expression of signal molecules relevant for inflammatory and angiogenic effects. Cyclooxygenase 1 (COX1) and COX2 activity assays were assessed in primary human monocytes. The release of nitric oxide (NO) and their synthesizing enzyme inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), VEGF and LL37 release were determined in lung epithelial cells A549, mast cells HMC 1.2 or in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs), respectively. The IC50 values of SBDS for the inhibition of recombinant human COX-1 and COX-2 were 1.9 and 8.3 µg/ml, respectively. In an inflammatory state (COX-2 expression) 100 µg/ml SBDS reduced PGE2 and TXB2 release in primary human monocytes. 25 µg/ml SBDS inhibited the mRNA and protein expression of iNOS. Moreover, 50 µg/ml SBDS and 30 µg/ml doxycycline inhibited the release of VEGF in an inflammatory state in HMC 1.2 cells. Both drugs did not affect LL37 release. Doxycycline did not affect intracellular NO levels and iNOS expression. SBDS and doxycycline mediate anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic effects through similar but also different signaling molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rosacea is a prevalent, chronic facial inflammatory disorder that affects about 5% of the global population1. It is characterized by symptoms such as papules, pustules, telangiectasia, and temporary flushing or persistent erythema accompanied by burning and stinging sensations2. These symptoms often lead to social phobia and stress among patients3,4. Rosacea is believed to be influenced by various factors, including bacterial proteases, heat, stress/irritants, and UVB radiation5. These factors activate the immune system, leading to inflammation, pain, dilation of blood vessels, and the formation of new blood vessels in the skin. As a result, the clinical symptoms of rosacea are initiated and intensified.

The pathophysiology of rosacea remains to be elucidated, but numerous factors are known to contribute. Among these, a dysregulation of immune cells specifically macrophages and mast cells as well as tissue cells such as keratinocytes are clearly implicated6. In lesions of rosacea patients an increased level of cytokines (e.g., IL8, TNFα), cyclooxygenases (COX), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cathelicidin as well as an increased number of immune cells and differentiated keratinocytes were detected7,8,9,10. It is hypothesized that macrophages activated by external stimuli leading to an increased release of eicosanoids, cytokines, chemokines, VEGF and thereby contributing to rosacea development8,11. Mast cells attracted by chemokines may release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and promoting thereby angiogenesis12. Neutrophils and keratinocytes activated by the pro-inflammatory environment release the anti-microbial peptide LL-3713. LL-37 was recently linked to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)14. Nitric oxide (NO) product of iNOS can specifically induce intestinal mucosal inflammation and alter physiological processes in the skin, including vasodilation, inflammation, and immunomodulation, leading to the clinical manifestations of flushing and erythema associated with rosacea15. Moreover, ROS induce production of VEGF16, which together with IL-1β and TNF-α, contribute to the vascular hyperreactivity seen in rosacea17. In summary, a variety of factors that activate the immune system, induce connective tissue damage (e.g. ROS), vascularization (e.g. VEGF) or vasodilation (e.g. eicosanoids) drive the development of rosacea18.

The importance of these factors in the development of rosacea becomes evident from the modes of action of approved drugs for rosacea. Common treatments are doxycycline, topical azelaic acid and sodium bituminosulfonate dry substance (SBDS), among others. It was shown that topical azelaic acid inhibits expression of KLK5 and cathelicidins in keratinocytes and/or in treated rosacea patients6. SBDS inhibits in neutrophils the release of LL37, VEGF, elastase, ROS and inhibits the activity of KLK5, 5-LO and MMP919. Doxycycline inhibits the production and activity of MMP9, inhibits the activity of KLK5, and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine release and the synthesis of ROS6.

In rosacea, patients experience redness of the skin due to inflammation, angiogenesis, and vasodilation6. These symptoms can be treated with SBDS and doxycycline20,21. SBDS is an non-biological complex drug (NBCD) derived from sulphur-rich oil shale with anti-inflammatory properties19. A comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to an electron ionization high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer (GC × GC-HR-ToF–MS) analysis revealed the structural class of the thiophenes as the most abundant in SBDS22. In 1953, the formulation SBDS was introduced onto market, and is approved in Germany and indicated for the treatment of rosacea.

The clinical effectiveness of tetracyclines such as doxycycline in the treatment of rosacea has been mainly attributed to their anti-inflammatory action, inhibitory effects on angiogenesis, leukocytic chemotaxis, inflammatory cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinase23. Doxycycline (40, 100 and 200 mg/day) is approved for the treatment of rosacea23. 100 mg doxycycline administrated once lead to a plasma cmax of about 1.5 µg/ml24.

A direct comparison of doxycycline and SBDS regarding its effect on signal molecules in in vitro experiments is missing. Moreover, some of the signaling molecules are derived from more than one cell type for example LL37 is released by keratinocytes and neutrophils, while VEGF is released by mast cells and neutrophils25,26. To understand how SBDS and doxycycline can mediate anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects, we conducted experiments on mast cells, keratinocytes, epithelial cells, and macrophages. We analyzed various signal molecules like NO, PGE2, TXB2 and proteins like iNOS, COX-1, COX-2, VEGF, LL37 involved in the synthesis or breakdown of anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory signaling molecules.

Results

SBDS inhibited COX-1 and COX-2 activity

Ammonium bituminosulfonate (Ichthyol®) inhibits the prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase isolated from sheep vesicular gland with an IC50 value of 300 µg/ml27. However Schewe et al. did not specify whether COX1 and/or COX2 was investigated. Therefore, we tested whether SBDS can affect the activity of human cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme responsible for synthesizing the precursor lipid PGH2 which is metabolized by PGE synthase or thromboxane synthase to PGE2 and TXB2, respectively. We performed an activity assay using recombinant human COX-1 and COX-2. The IC50 values for COX-1 and COX-2 were determined to be 1.9 ± 0.1 µg/ml and 8.3 ± 1.1 µg/ml, respectively (Fig. 1a/b). SBDS completely inhibited COX-1, whereas COX-2 activity was inhibited to about 70%.

SBDS inhibited COX-1 and COX-2 and did not affect LL-37. (a/b) SBDS in a concentration range from 0.1–1000 µg/ml were tested with a COX-1 (a) or COX-2 (b) activity assay. The experiments were performed in three replicates. The IC50 values were calculated using a non-linear fitting model (GraphPad Prism Software 9.2.0). (c) For the cellular COX-1 assay, primary human CD14+ monocytes were treated with SBDS or vehicle for 60 min. To start COX-1 reaction its substrate arachidonic acid was added. (d) For the cellular COX-2 assay, primary human CD14+ monocytes were pretreated with ASA to block COX-1 activity and COX-2 expression was induced by LPS treatment for 16 h. Subsequently monocytes were treated with SBDS or vehicle for 30 min. To start COX-2 reaction its substrate arachidonic acid was added. The products PGE2 and TXB2 were determined by ELISA. To obtain fold induction the PGE2 and TXB2 levels of samples treated with SBDS were related to control samples. The experiment was achieved with monocytes from three different donors. (e/f) NHEKs were preincubated for 3 h with SBDS at the indicated concentrations and stimulated with 2.5 µg/ml LPS (f; striped bars) or left untreated (e; blank bars) for 6 h. The release of LL-37 was determined by ELISA. The experiments were performed in three replicates. To calculate statistical significance Mixed-effects analysis with Dunnett`s multiple comparisons test was used. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 indicate statistical significance between treated samples and vehicle samples. Abb. COX, cyclooxygenase; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TXB2, thromboxane 2.

To investigate if the inhibition of COX-1 by SBDS can also be observed in a cellular set-up, primary human monocytes which constitutively express COX-1 were used. The enzyme was activated by the addition of its substrate arachidonic acid. The human primary monocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of SBDS and levels of PGE2 and TXB2 were measured. The positive control acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (20 µg/ml) inhibited COX-1 using PGE2 as read-out to 73% and using TXB2 as read-out to 92%. 1 µM SC-650 inhibited COX-1 using PGE2 or TXB2 as read-out to 52% and 76%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 1a). Interestingly, 100 µg/ml of SBDS inhibited the release of PGE2, while 500 µg/ml was required to inhibit TXB2. However, the reduction in PGE2 was only about 30%, whereas TXB2 was reduced by about 60% (Fig. 1c).

For the cellular COX-2 assay, primary human monocytes were stimulated with LPS (lipopolysaccharide) to induce COX-2 expression and pretreated with ASA to inhibit constitutively expressed COX-1. COX-2 was activated by the addition of its substrate arachidonic acid. As expected, the COX-1 inhibitor SC-560 (5 µM) did not inhibit COX-2 using PGE2 or TXB2 as read-out. The positive control NS-398 (5 µM) inhibited COX-2 using PGE2 as read-out to 63% and using TXB2 as read-out to 69%. 5 µM diclofenac inhibited COX-2 using PGE2 or TXB2 as read-out to 82% and 92%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 1b). Interestingly, at a concentration of 100 µg/ml, SBDS reduced the level of PGE2, and 50 µg/ml of SBDS reduced the level of TXB2. 500 µg/ml SBDS reduced PGE2 levels by about 70% and TXB2 levels by about 90% (Fig. 1d). These findings suggest that SBDS has a stronger inhibitory effect on the release of PGE2 and TXB2 in an inflammatory (COX-2) environment compared to a normal (COX-1) environment within a cellular system.

SBDS did not affect LL-37 release in NHEKs

Innate immune activation leads to upregulation of keratinocyte-derived toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) promoting the expression of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, which is subsequently activated to bioactive LL-37 by kallikrein 5 (KLK-5) protease, leading to erythema and angiogenesis28. Recently, we demonstrated that SBDS inhibited KLK5 the enzyme that metabolizes cathelicidin to LL-37 with an IC50 value of 7.6 µg/ml19. Moreover, we observed that SBDS reduced the release of LL-37 in neutrophils. Besides neutrophiles also keratinocytes are main producers of LL-375, therefore we investigated if SBDS also inhibits the release of LL-37 in keratinocytes. We used non-toxic concentrations of SBDS (0–20 µg/ml), identified by a viability assay (Supplemental Fig. 2a). Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) were pretreated with SBDS and stimulated with the TLR2 agonist LPS or left unstimulated. Astonishingly, SBDS had no influence on LL-37 release in NHEKs independent of the activation status (Fig. 1e/f). These data indicate that the effect of SBDS on the inhibition of LL-37 release is cell type dependent.

SBDS inhibited iNOS expression in A549 cells

Since SBDS inhibited the release of LL-37 an inducer of reactive oxygen species in some cell types, we investigated whether SBDS also affects the NO synthesis. We used non-cytotoxic concentrations of SBDS, identified by a viability assay (Supplemental Fig. 3a). We observed an IC50 value of 9 µg/ml for NO inhibition in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages (Supplemental Fig. 3b). To translate this effect into the human system we used A549 lung epithelial cells, since there is no known stimuli to induce NO release ex vivo in human macrophages29. Non-cytotoxic concentrations identified by a viability assay were applied (Supplemental Fig. 2b). We investigated whether SBDS could alter iNOS expression by treating A549 cells with various concentrations of SBDS. 50 µg/ml SBDS inhibited the basal iNOS mRNA expression (Fig. 2a), whereas 2.5 µg/ml SBDS significantly inhibited cytokine mix-induced iNOS mRNA expression (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, also the cytokine mix-induced iNOS protein expression was significantly reduced by 25 µg/ml, whereas the basal iNOS level was not influenced by SBDS (Fig. 2c-e). Astonishingly, the inhibition of iNOS did not translate into a reduction of intracellular NO levels in cytokine mix stimulated A549 cells (Fig. 2f/g).

SBDS did inhibit iNOS expression and VEGF release. (a-g) The iNOS mRNA (a/b), protein (c-e) expression and iNO levels (f/g) were determined in A549 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ and 5 ng/ml TNFα or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of SBDS in the indicated concentrations. (a/b) iNOS and GADPH mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. iNOS levels were normalized to GAPDH. SBDS treated samples were related to control samples. (c) iNOS and actin levels were determined by western blot technique. (d/e) The optical densitometry analysis was achieved with Image Lab 6.0 software. The iNOS levels were normalized to actin. SBDS treated samples were related to control samples. (f/g) iNO levels were determined by staining of NO with 5 µM DAF-FM-DA and analysing by flow cytometry. The MFI of SBDS-treated samples were related to control samples. (h-k) The VEGF mRNA (h/i) and protein (j/k) expression was determined in HMC 1.2 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 25 ng/ml PMA and 200 nM calcium ionophore A23187 or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of SBDS in the indicated concentrations. (h/i) VEGF and GADPH mRNA expression were determined by qPCR. VEGF levels were normalized to GAPDH. SBDS treated samples were related to control samples. (j/k) VEGF levels collected from the supernatant were determined by ELISA. The VEGF level of SBDS treated samples were related to control samples. The experiments were repeated three - five times. To calculate statistical significance two-way ANOVA with Dunnett`s multiple comparisons test was used. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 indicate statistical significance between treated samples and vehicle samples. Abb. CM, cytokine mixture; DOX, doxycycline; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; iNO, intracellular nitric oxide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

SBDS inhibited VEGF release

Next, we investigated the effect of SBDS on VEGF release and the expression of VEGF mRNA in mast cells, since in rosace mast cells release VEGF and contribute thereby to angiogenesis30. Recently, it was suggested that mast cells which release VEGF play a role in connecting innate immunity, nerves, and blood vessels in the rosacea development. Moreover, an increased number of mast cells were observed in rosacea lesions30. Therefore, we examined whether SBDS may affect the VEGF release in the mast cell line HMC 1.2. Non-cytotoxic SBDS concentrations were used (Supplemental Fig. 2c). HMC 1.2 cells were treated with SBDS and stimulated with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and calcium ionophore to produce/release VEGF. SBDS did not induce the VEGF mRNA expression (Fig. 2h), nor did inhibit the PMA/calcium ionophore-induced VEGF mRNA expression in HMC 1.2 cells (Fig. 2i). Mast cells store VEGF intracellularly, which is then released upon stimulation31. SBDS did not affect the release of VEGF in unstimulated cells (Fig. 2j), whereas 50 µg/ml SBDS inhibited the PMA/Ca ionophore-induced VEGF release (Fig. 2k). These data indicate that SBDS prevents the exocytosis of VEGF stored in vesicles in an inflamed state.

Doxycycline inhibited VEGF release

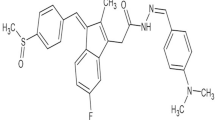

To compare the mode of actions of SBDS and doxycycline, we also investigated the impact of doxycycline on various signaling molecules. We previously determined an IC50 value of 7.6 µg/ml for SBDS in inhibiting KLK519. In contrast, doxycycline revealed an IC50 value of 42.4 µg/ml (Fig. 3a). Non-cytotoxic doxycycline concentrations were used for the cellular assays (Supplemental Fig. 2a-c). Doxycycline did not affect the basal and LPS-induced release of LL-37 in NHEKs (Fig. 3b/c). Interestingly, doxycycline did not influence intracellular NO levels, iNOS protein and iNOS mRNA expression in both basal and inflammatory state in A549 cells (Fig. 3d-j). 30 µg/ml doxycycline induced the synthesis of VEGF mRNA in unstimulated HMC 1.2 cells (Fig. 3k), but did not influence PMA and calcium ionophore stimulated VEGF mRNA expression (Fig. 3l). However, 30 µg/ml doxycycline inhibited VEGF release induced by PMA and calcium ionophore in HMC 1.2 cells (Fig. 3n). These findings indicate that doxycycline inhibits VEGF signaling in the inflammatory state.

Effects of doxycycline on KLK5, LL37, iNOS, iNO and VEGF. (a) Human recombinant KLK5 was preincubated with doxycycline for 5 min and incubated with its fluorogenic substrates for 5 min and the product was detected spectrophotometrically. The IC50 values was calculated using a non-linear fitting model (GraphPad Prism Software 9.2.0). (b/c) NHEKs were preincubated for 3 h with doxycycline at the indicated concentrations and stimulated with 2.5 µg/ml LPS (c; striped bars) or left untreated (b; blank bars) for 6 h. The release of LL-37 was determined by ELISA. (d-j) The iNOS mRNA (d/e), protein (f-h) expression and iNO levels (i/j) were determined in A549 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ and 5 ng/ml TNFα or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of doxycycline in the indicated concentrations. (d/e) iNOS and GADPH mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. iNOS levels were normalized to GAPDH. Doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (e-h) iNOS and actin levels were determined by western blot technique. (g/h) The optical densitometry analysis was achieved with Image Lab 6.0 software. The iNOS levels were normalized to actin. Doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (i/j) iNO levels were determined by staining of NO with 5 µM DAF-FM-DA and analysing by flow cytometry. The MFI of doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (k-n) The VEGF mRNA (k/l) and protein (m/n) expression was determined in HMC 1.2 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 25 ng/ml PMA and 200 nM calcium ionophore A23187 or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of doxycycline in the indicated concentrations. (k/l) VEGF and GADPH mRNA expression were determined by qPCR. VEGF levels were normalized to GAPDH. Doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (m/n) VEGF levels collected from the supernatant were determined by ELISA. The VEGF level of doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. The experiments were repeated three – five times. To calculate statistical significance two-way ANOVA with Dunnett`s multiple comparisons test was used. *p < 0.05 indicate statistical significance between treated samples and vehicle samples. Abb. CM, cytokine mixture; DOX, doxycycline; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; iNO, intracellular nitric oxide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Combination therapy of Doxycycline and SBDS had no beneficial effect on signal molecules

Since combination treatments such as oral doxycycline (40 mg once/day) and azelaic acid 15% gel are also effective, safe, and well-tolerated in rosacea patients20, we investigated whether combining doxycycline and SBDS has any beneficial in vitro effects. We used non-effective concentrations of SBDS (2.5 µg/ml) and doxycycline (5 µg/ml) to investigate if the compounds have synergistic effects. The combination therapy had no effect on the release of LL37 (Fig. 4a), did not affect iNOS mRNA in the basal state and protein expression (Fig. 4b-d) as well as the iNO levels in the basal and inflammatory state (Fig. 4e). But it reduced the iNOS mRNA level in the inflammatory state and the basal level of VEGF (Fig. 4b/4f). These findings suggest that the combination therapy does not have huge beneficial effects on the investigated signaling molecules.

Combination treatment of SBDS and doxycycline has no effect on LL37, iNOS, iNO and VEGF. (a) NHEKs were preincubated with 2.5 µg/ml SBDS and 5 µg/ml doxycycline for 3 h and stimulated with 2.5 µg/ml LPS (striped bars) or left untreated (blank bars) for 6 h. The release of LL-37 was determined by ELISA. b-d) The iNOS mRNA (b) and protein (c/d) expression was determined in A549 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ and 5 ng/ml TNFα or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of 2.5 µg/ml SBDS and 5 µg/ml doxycycline. (b) iNOS and GADPH mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. iNOS levels were normalized to GAPDH. SBDS and doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (c) iNOS and actin levels were determined by western blot technique. (d)The optical densitometry analysis was achieved with Image Lab 6.0 software. The iNOS levels were normalized to actin. SBDS and doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. (e) iNO levels were determined by staining of NO with 5 µM DAF-FM-DA and analysing by flow cytometry. The MFI of doxycycline and SBDS treated samples were related to control samples. (f) The VEGF protein expression was determined in HMC 1.2 cells stimulated (striped bars) with 25 ng/ml PMA and 200 nM calcium ionophore A23187 or unstimulated (blank bars) in presence or absence of 2.5 µg/ml SBDS and 5 µg/ml doxycycline. VEGF levels collected in the supernatant were determined by ELISA. The VEGF level of SBDS and doxycycline treated samples were related to control samples. The experiments were performed in biological triplicates. To calculate statistical significance two-way ANOVA with Dunnett`s multiple comparisons test was used. *p < 0.05 indicate statistical significance between treated samples and vehicle samples. Abb. Ca, calcium ionophore; CM, cytokine mixture; DOX, doxycycline; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; iNO, intracellular nitric oxide; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PMA, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

SBDS reduced the release of inflammatory mediators (PGE2 and TXB2) and the synthesis of iNOS. SBDS and doxycycline reduced the release of the growth factor VEGF in an inflammatory state. Our data confirmed the anti-inflammatory potential of SBDS and doxycycline by the use of various signal molecules released by relevant cell types. An aim of the study was to compare the effects and the molecular mechanism of SBDS and doxycycline. In Table 1 literature data and our results of both agents on several signal molecules are summarized.

SBDS and doxycycline treatment of rosacea patients led to an improvement of symptoms potentially by reducing inflammation and vasodilation. Signal molecules that are responsible for vasodilation or vasoconstriction among others are NO, PGE2 and TXA2 (Fig. 5). NO mediates flow-mediated vasodilation, opposes vasoconstrictor effects, counteracts vascular stiffness and lowers blood pressure32. PGE2 can mediate either vasodilatory or vasoconstrictive effects depending on the receptor it interacts with. When PGE2 interacts with EP1 and EP3, it induces vasoconstriction, while it promotes vasodilatation when binding to EP2 and EP4 receptors33. TXA2 stimulates TXA2 receptor to induce vasoconstriction34,35. Interestingly, SBDS inhibited in murine macrophages NO release and in human lung epithelial cells iNOS expression in an inflammatory state, but had no effect on NO synthesis in human lung epithelial cells. Moreover, SBDS inhibited the vasoconstrictor TXB2 (stable metabolite of TXA2) and the vasodilator PGE2 in human monocytes. Since SBDS led to a reduction of redness in rosacea patients, these data indicate that the effect of SBDS on NO and TXB2 in vitro are potentially not relevant for the in vivo observed effect. The inhibition of PGE2 can potentially contribute to the clinical effects of SBDS, but for a final conclusion the expression levels of the EP receptors in rosacea would be needed. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of SBDS on the reduction of redness in rosacea patients may also stem from its impact on inflammatory molecules produced by other cell types present in the skin and/or lesions, such as neutrophils36 Previous studies have already demonstrated that SBDS inhibits VEGF, LL-37, ROS, and Ca2+ release in neutrophils19.

Potential contribution of SBDS and doxycycline in inflammatory and vascular-modifying pathways (created with Biorender). Macrophages release the vasoconstrictive TXB2. the vasodilatory NO and PGE2, which mediates either vasodilatory or vasoconstrictive effects depending on the interacting EP receptor. SBDS impairs the release of NO in murine macrophages and the release of PGE2 and TXB2 in human primary macrophages. Cytokines released by macrophages activate neutrophils and keratinocytes, which among others, release the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. KLK5 is responsible for cleaving the inactive precursor protein hCAP18 to form the active antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Both SBDS and doxycycline inhibit KLK5. SBDS specifically inhibits the release of LL-37 in neutrophils. LL-37 promotes the release of VEGF from neutrophils and mast cells. SBDS reduced the release of VEGF from both neutrophils and mast cells, while doxycycline reduced the release of VEGF from mast cells. Inhibitory arrows for macrophages are depicted in light purple, for neutrophils in blue, for the enzyme KLK5 in red, and for mast cells in yellow.

We observed a decrease in iNOS expression for SBDS; however, this does not correspond to a reduction in iNO levels. Several factors may explain this observation: (1) The dye DAF-FM-DA used is not specific for NO and may react with other cellular molecules or directly with a component of SBDS, as it is known to react with thiols37 One structural class of SBDS identified by two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to an electron ionization high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer consists of benzenethiols22 (2) SBDS may react with intracellular molecules to indirectly generate NO. (3) SBDS may influence the cellular redox state, thereby stabilizing the bioactivity of existing NO. Hoyt et al. observed for 30 µg/ml doxycycline an inhibition of NO release in murine lung epithelial cells38. In human lung epithelial cells, doxycycline did not affect NO synthesis. However, in rosacea patients treated with doxycycline a reduction of iNOS in the inflammatory infiltrate was observed39. It was not investigated whether TXB2 release is influenced by doxycycline, however Attur et al. showed that doxycycline induced an increase of COX-2 expression and PGE2 release in LPS-treated macrophages indicating that potentially also TXB2 a metabolite of PGH2 (product of COX-2 synthesis and precursor of TXB2) is increased. Since the production of PGH2 by COX-2 is the rate limiting step in prostaglandin synthesis, an increase in COX-2 is linked to an increase of the 5 majors bioactive prostaglandins (PGE2, PGI2, PGD2, PGF2, and TXA2) through their respective tissue-specific synthases, when they are expressed40. In macrophages thromboxane synthase is expressed (https://www.proteinatlas.org) and therefore a doxycycline induced increase of COX-2 may be linked to an increase in TXB2. In summary, SBDS and doxycycline potentially mediate their vasoconstrictive effects via different signal molecules.

We observed varying inhibitory effects of SBDS in the cellular system compared to the activity assay with recombinant protein. In the cellular assay, SBDS appears to have a greater impact on COX-2 than on COX-1, which contradicts the results from the activity assay. We hypothesize that this discrepancy may be due to the availability and metabolism of SBDS. However, the differing effects of SBDS on intracellular versus recombinant COX-2 and COX-1 can only be explained by these factors if different components of SBDS are responsible for inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2. This implies that the component inhibiting COX-1 has low permeability, while the component inhibiting COX-2 has high permeability.

In rosacea patients treated with doxycycline a reduction of cathelicidin LL37 was detected39. SBDS (IC50 = 8 µg/ml) and doxycycline (IC50 = 42 µg/ml) inhibited the activity of KLK5, the enzyme that processes the cathelicidin precursor protein (hCAP)18 to LL3719. This may translate to an inhibition of LL37 release in neutrophils by 50 µg/ml SBDS19, whereas in NHEKs no inhibition of LL37 was observed (Fig. 5). Also, doxycycline up to 30 µg/ml did not reduce the release of LL37 in NHEKs. However, Kanada et al. evaluated the ability of doxycycline to inhibit processing of cathelicidin by the addition of full-length recombinant cathelicidin hCAP18 to NHEKs and found that 225 µM doxycycline inhibits the release of LL3741. These data indicate that the inhibition of LL37 by SBDS and doxycycline seems to be cell type or concentration dependent. The inhibition of LL37 could be a mechanism how both drugs improve the clinical features of rosacea such as erythema, telangiectasia and inflammation, since in a mouse model a LL37 injection led to such clinical features possibly through the enhanced expression of IL1, IL6 and MMP9 in mast cells42,43. Additionally, LL-37 increases cytokine and chemokine liberation from leukocytes and has chemotactic effects on a large number of immune cells44.

In an inflammatory state, both doxycycline and SBDS inhibited the release of VEGF from mast cells, but have no effect on VEGF mRNA synthesis (Table 1; Fig. 5). VEGF is stored in vesicle in various cell types such as human neutrophils, human basophils, murine macrophages and human ovarian carcinoma cell lines CABAI and A278045,46,47,48. Our findings in mast cells confirm previous results obtained in neutrophils that SBDS prevents the release of primary and secondary granules and also demonstrate this effect in mast cells19. In a basal state, SBDS and doxycycline seems to increase VEGF in mast cells (Figs. 2j and 3m). Interestingly, 10 µg/ml doxycycline has been shown to upregulate VEGF mRNA in murine cardiomyocytes and reduce it in murine endothelial cells, with no change in protein levels49. The VEGF mRNA upregulation in cardiomyocytes may contribute to the cardioprotective effects of doxycycline after myocardial infarction in rats and the reduced adverse post-myocardial infarction left ventricular remodelling in patients50,51. On the other hand, doxycycline has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in endothelial cells, which aligns with the decreased VEGF mRNA expression observed in endothelial cells49,52. Moreover, in rosacea patients treated with doxycycline a reduction of VEGF was observed39. The potential effect of increased VEGF mRNA in mast cells needs to be further studied. In summary, the effect of doxycycline appears to be dependent on the cell type.

SBDS and doxycycline appear to exert its anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and vasodilating effects in rosacea via different mechanisms and potentially target different cell types. Both inhibit the release of VEGF. Additionally, SBDS blocks the eicosanoid signaling. Our data suggest that SBDS possibly regulates anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic processes by suppressing PGE2 and the release of VEGF, respectively. Doxycycline may mediate its anti-angiogenic effect by suppressing VEGF. In summary, SBDS and doxycycline may have VEGF as target in common.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

A549 cells were obtained from Cell Bank of the JCRB (Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources)/HSRRB (Human Science Research Resources Bank) and cultured in DMEM F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HMC1.2 were purchased from Merck KGaA (SCC062, Darmstadt, Germany) and cultured in Iscove`s modified Dulbecco`s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 1.2 mM α-thioglycerol, 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. NHEK were purchased from PromoCell (C-12005, Heidelberg, Germany) and cultured in Keratinocyte Growth Medium 2 supplemented with 0.06 mM CaCl2 and 12.3 mM supplemental mix. RAW264.7 macrophages were a gift from Prof. Grösch (Goethe University Frankfurt) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Primary human monocytes were cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Doxycycline was dissolved in water and further diluted in media. SBDS was dissolved in water or DMSO (COX-1/COX-2 assay) and further diluted in media. Oil shale-derived SBDS was provided by the Ichthyol-Gesellschaft. Orangu™ was purchased from Hiss Diagnostics GmbH (Freiburg, Germany). COX-1, COX-2 assay and TXB2 ELISA were obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, USA). PGE2 ELISA were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences GmbH (Lörrach, Germany).

COX-1 and COX-2 activity assay

The assay was performed as described by the supplier. The COX-1 and COX-2 assay measures PGF2α by SnCl2 reduction of PGH2 produced in the COX reaction. PGF2α was quantified via a competitive ELISA. Increasing concentrations of SBDS (0–1000 µg/ml) were incubated with the recombinant human COX-1 or COX-2 for 10 min. Reaction was started by the addition of arachidonic acid, after 2 min SnCl2 was added to reduce PGH2 to PGF2α. PG-acetylcholinesterase conjugate was held constant while the concentration of the produced PGF2α varied. PGF2α and PG-acetylcholinesterase conjugate competed with the binding to PG antiserum. An increasing PGF2α concentration led to a reduced binding of PG-acetylcholinesterase conjugate. PG-acetylcholinesterase conjugate and PGF2α bound to PG antiserum, which was captured by a mouse monoclonal anti-rabbit antibody that had been attached to the well. After washing of the plate, the substrate (Ellman`s reagent) of the acetylcholinesterase was added and the product of this reaction was measured at 412 nm. The intensity of the absorbance was proportional to the amount of PG-acetylcholinesterase conjugate, which was inversely proportional to the amount of PG produced by COX-1.

Cellular COX-1 and COX-2 assay

The COX-1 assay was performed as described by Demasi et al.53. Briefly, monocytes were isolated from buffy coat by positive selection using CD14+ microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as described previously54. 4 × 105 monocytes were pretreated with 10 µg/ml acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in 200 µl RPMI medium (10% FCS), with SBDS (0, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 µg/ml), 1 µM SC-560 or with vehicle (DMSO, Water) in 200 µl RPMI medium (10% FCS) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed once with 200 µl RPMI 10%FCS and once with 200 µl RPMI w/o FCS. 100 µM arachidonic acid (dissolved in EtOH and buffered with KOH) in 240 µl RPMI medium (without FCS) were added for 15 min at 37 °C. The supernatants were stored at −80 °C and the PGE2 and TXB2 level were determined by ELISA as described by the supplier.

The COX-2 assay was performed as described by Demasi et al.53. Briefly, 1 × 106 monocytes were pretreated with 10 µg/ml ASA in 200 µl RPMI medium (10% FCS) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed twice with 200 µl RPMI medium (10% FCS). 10 µg/ml LPS in 200 µl RPMI medium (10% FCS) was added and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C to induce COX-2 expression. The cells were washed twice with 200 µl RPMI medium (without FCS). Cells were treated with SBDS (0, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 µg/ml), 5 µM NS-398, 5 µM SC-560, 5 µM Diclofenac or with vehicle (DMSO, Water) in 200 µl RPMI medium (without FCS) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed twice with 200 µl RPMI medium (without FCS). 100 µM arachidonic acid (dissolved in EtOH and buffered with KOH) in 240 µl RPMI medium (without FCS) were added for 15 min at 37 °C. The supernatants were stored at −80 °C and PGE2 and TXB2 level were determined by ELISA as described by the supplier.

LL-37 detection assay

40.000 NHEKs were seeded in 96 well plates and preincubated with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 25 µg/ml of SBDS, 0, 1, 5, 10, 20 µg/ml doxycycline or vehicle for 3 h at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere. 2.5 µg/ml LPS was added or the cells were left untreated and incubated for 6 h at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere. The supernatant was collected and LL-37 was determined by ELISA, as recommended by the supplier (Hycultec GmbH, Beutelsbach, Germany). For analysis, the absorbance values from standard and from samples were corrected with that of the samples without cells. The concentration of LL-37 was extrapolated using the standard curve.

iNOS mRNA detection

0.25 × 106 A549 cells were pretreated with SBDS (0, 2.5, 25, 50 µg/ml) or doxycycline (0, 15, 30 µg/ml) in FCS-free DMEM/F 12 medium for 3 h and stimulated with a cytokine mixture consisting of 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ und 5 ng/ml TNFα or left unstimulated for 18 h at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were washed, harvested and mRNA (RNAeasy Kit from Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was isolated. 1 µg of mRNA were transcribed in cDNA by First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) as recommended by the supplier. iNOS and GAPDH mRNA were determined by qPCR with EvaGreen® Master Mix (Bio&Sell, Feucht/Nürnberg, Germany). iNOS forward primer: 5`GTGCTCTTTGCCTGTATGC; iNOS reverse primer: 5`CAGCTCAGCCTGTACTTATCC; GAPDH forward primer: 5`GCACCACCAACTGCTTAG; GAPDH reverse primer: 5`CCATCACGCCACAGTTTC. The data were analyzed by 2−ΔΔCT method a relative quantification strategy for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) data analysis. The Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software was used. The mRNA expression levels were normalized to the reference gene glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and related to the control samples.

iNOS protein detection

1.75 × 106 A549 cells were pretreated with SBDS (0, 2.5, 25, 50 µg/ml) or doxycycline (0, 15, 30 µg/ml) in FCS-free DMEM/F 12 medium for 3 h and stimulated with a cytokine mixture consisting of 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ und 5 ng/ml TNFα or left unstimulated for 24 h at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were washed, harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer (ChemCruz/Santa Cruz Biotechnologie, Inc., Dallas, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitors (2 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM Natrium orthovanadate und protease inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid. 100 µg protein were separated by SDS page and blotted. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk powder suspended in TBS-T buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride, 0.05% Tween 20) (at room temperature), stained with an anti-iNOS (1:500; 20609 S, Cell Signaling, Danvers, USA) for 2 days (at 4 °C) and mouse anti-actin (1:1000; CL594-66009, Proteintech Group Inc., Rosemont, USA) antibody for 2 h at room temperature. As second antibody goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alex Flour™ 488 (1:10000; A11008, Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific/Waltham, USA) were applied for 1 h at room temperature. The images of the blots were acquired with ChemiDocTM MP (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). Optical densitometry was determined by the Image Lab 6.0 software. The adjusted volume intensity of iNOS were related to actin. The relative iNOS levels from treated samples were related to vehicle treated samples.

Intracellular NO level

1 × 104 A549 cells were pretreated with SBDS (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50 µg/ml) or doxycycline (0, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30 µg/ml) in FCS-free DMEM/F 12 medium for 3 h and stimulated with a cytokine mixture consisting of 5 ng/ml IL1β, 5 ng/ml IFNγ und 5 ng/ml TNFα or left unstimulated for 24 h. Intracellular NO (iNO) was stained with 5 µM DAF-FM-DA for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed three times with 100 µl Dulbecco´s Phosphate Buffered Saline and analysed by flow cytometry. MFI values of SBDS or doxycycline treated values with DAF-FM-DA were corrected with MFI values from cells treated with the substances without DAF-FM-DA. The corrected MFI values of SBDS or doxycycline treated cells were related to the corrected MFI values of vehicle-treated samples to obtain the relative iNO value.

VEGF assay

25.000 or 500.000 HMC 1.2 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate (protein analysis) or 6-well plate (mRNA analysis), respectively, and treated with SBDS (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 25 µg/ml), doxycycline (0, 1, 5, 10, 20 µg/ml) or vehicle in medium with 5% FCS for 3 h at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere. To investigate whether SBDS can prevent VEGF release/synthesis, HMC 1.2 mast cells were stimulated with 25 ng/ml PMA and 200 nM calcium ionophore A23187 for 6 h (mRNA) or 20 h (protein). To investigate whether SBDS induces VEGF release/synthesis, cells were left unstimulated for 6 h (mRNA) or 20 h (protein) at 37 °C/5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cells from the 6-well plate were centrifuged (300 g, 5 min, RT) and harvested for mRNA analysis. mRNA (RNAeasy Kit from Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was isolated and 1 µg of mRNA were transcribed in cDNA by First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) as recommended by the supplier. VEGF and GAPDH mRNA were determined by qPCR with EvaGreen® Master Mix (Bio&Sell, Feucht/Nürnberg, Germany). VEGF forward primer: 5` GGGCAGAATCATCACGAAG; VEGF reverse primer: 5` CTCGATCTCATCAGGGTACTC; GAPDH forward primer: 5`GCACCACCAACTGCTTAG; GAPDH reverse primer: 5`CCATCACGCCACAGTTTC. The data were analyzed by 2^-ΔΔCt method using the Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software. The mRNA expression levels were normalized to the reference gene glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and related to the control samples.

Supernatant from the 96-well plate was collected and the concentration of VEGF determined by ELISA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), as recommended by the supplier. For analysis, the absorbance values from standard and from test samples were corrected with the blank (standard: assay buffer; samples: medium with test substances), since the values of the controls decreased with increasing concentration of test substances. The concentration of VEGF was extrapolated using the standard curve.

KLK5 assay

The KLK5 assay was performed as previously described19. Briefly, recombinant humane KLK5 enzyme (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) and the fluorogenic substrate Boc-V-P-R-AMC substrate (Boc: t-Butyloxycarbonyl; AMC: 7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin) (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) were used. rhKLK5 was diluted in 1 M NaH2PO4 pH 8 and doxycycline (0.48 µg/ml – 480 µg/ml) or water (background control (C) with enzyme without compound) was added and incubated for 5 min at RT. 100 µM Boc-V-P-R-AMC substrate was added and incubated for 5 min at RT. The fluorescence was detected with the Multimode Plate Reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany) (Ex380 nm/Em460 nm). The inhibition was calculated with the following equation: (1 - (A - B1)/(C - B2)) * 100. A = RFU Test sample; B1 = basal RFU without enzymes with compound; B2 = basal RFU without enzymes with vehicle; C = RFU vehicle control with enzymes. The test samples (A) were corrected for the RFU of samples without enzyme but with test substance (B1), due to the high background signal of the test substance that was concentration dependent.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as means ± standard errors. The data were analysed with one-way ANOVA and or two-way ANOVA and with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. For all calculations and creation of graphs, GraphPad Prism 8 was used and p < 0.05 was considered the threshold for significance.

Data availability

Data will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ASA:

-

Acetylsalicylic acid

- COX:

-

Cyclooxygenase

- DAF-FM DA:

-

4-Amino-5-Methylamino-2',7'-Difluorofluorescein Diacetate

- eNO:

-

Extracellular nitric oxide

- EP:

-

Prostaglandin E receptor

- FCS:

-

Fetal calf serum

- fMLP:

-

Formyl-Methionyl-Leucyl-Phenylalanine

- GAPDH:

-

Glycerinaldehyd-3-phosphat-dehydrogenase

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- iNO:

-

Intracellular nitric oxide

- iNOS:

-

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KLK5:

-

Kallikrein 5

- 5-LO:

-

5 Lipoxygenase

- LTB4:

-

Leukotriene B4

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MMP9:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

- NHEK:

-

Normal human epidermal keratinocyte

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PGE2 :

-

Prostaglandin E2

- PMA:

-

Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SBDS:

-

Sodium bituminosulfonate dry substance

- TXB2:

-

Thromboxane B2

- TNFα:

-

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Gether, L., Overgaard, L. K., Egeberg, A. & Thyssen, J. P. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 179, 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16481 (2018).

Steinhoff, M., Schauber, J. & Leyden, J. J. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 69, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.045 (2013).

Chang, H. C., Huang, Y. C., Lien, Y. J. & Chang, Y. S. Association of rosacea with depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.008 (2022).

Halioua, B., Cribier, B., Frey, M. & Tan, J. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with rosacea. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 31, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13748 (2017).

Buddenkotte, J. & Steinhoff, M. Recent advances in Understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res 7 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16537.1 (2018).

Woo, Y. R., Lim, J. H., Cho, D. H. & Park, H. J. Rosacea: molecular mechanisms and management of a chronic cutaneous inflammatory condition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17091562 (2016).

Casas, C. et al. Quantification of demodex folliculorum by PCR in rosacea and its relationship to skin innate immune activation. Exp. Dermatol. 21, 906–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12030 (2012).

Buhl, T. et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in Rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135, 2198–2208. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.141 (2015).

Deng, Z. et al. Keratinocyte-Immune cell crosstalk in a STAT1-Mediated pathway: novel insights into Rosacea pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.674871 (2021).

Moura, A. K. A., Guedes, F., Rivitti-Machado, M. C. & Sotto, M. N. Inate immunity in rosacea. Langerhans cells, plasmacytoid dentritic cells, Toll-like receptors and inducible oxide nitric synthase (iNOS) expression in skin specimens: case-control study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 310, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-018-1806-z (2018).

Liu, Y., Zhou, Y., Chu, C. & Jiang, X. The role of macrophages in rosacea: implications for targeted therapies. Front. Immunol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1211953 (2023).

Grutzkau, A. et al. Synthesis, storage, and release of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor (VEGF/VPF) by human mast cells: implications for the biological significance of VEGF206. Mol. Biol. Cell. 9, 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.9.4.875 (1998).

Meyer-Hoffert, U. & Schroder, J. M. Epidermal proteases in the pathogenesis of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 15, 16–23, (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/jidsymp.2011.2

Zheng, Y. et al. Cathelicidin LL-37 induces the generation of reactive oxygen species and release of human alpha-defensins from neutrophils. Br. J. Dermatol. 157, 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08196.x (2007).

Joura, M. I., Brunner, A., Nemes-Nikodem, E., Sardy, M. & Ostorhazi, E. Interactions between immune system and the Microbiome of skin, blood and gut in pathogenesis of rosacea. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 68, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1556/030.2021.01366 (2021).

Kuroki, M. et al. Reactive oxygen intermediates increase vascular endothelial growth factor expression in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1667–1675. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI118962 (1996).

Gerber, P. A., Buhren, B. A., Steinhoff, M. & Homey, B. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J. Investig Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 15, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/jidsymp.2011.9 (2011).

Maden, S. & Rosacea An overview of its etiological factors, pathogenesis, classification and therapy options. Dermato 3, 241–262. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermato3040019 (2023).

Schiffmann, S. et al. Sodium Bituminosulfonate used to treat Rosacea modulates generation of inflammatory mediators by primary human neutrophils. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 2569–2582. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S313636 (2021).

Del Rosso, J. Q. et al. Two randomized phase III clinical trials evaluating anti-inflammatory dose Doxycycline (40-mg Doxycycline, USP capsules) administered once daily for treatment of rosacea. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 56, 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.021 (2007).

Koch, R. & Wilbrand, G. Dark sulfonated shale oil vs placebo in the systemic treatment of rosacea. J. Euro. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 12 (2 Suppl.). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.1999.tb00920.x (1999).

Schwalb, L. et al. Analysis of complex drugs by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry: detailed chemical description of the active pharmaceutical ingredient sodium Bituminosulfonate and its process intermediates. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 415, 2471–2481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-022-04393-w (2023).

Sharma, A. et al. Rosacea management: A comprehensive review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 21, 1895–1904. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14816 (2022).

Kees, F., Dehner, R., Dittrich, W., Raasch, W. & Grobecker, H. [The bioavailability of Doxycycline]. Arzneimittel-Forschung 40, 1039–1043 (1990).

Wang, L. et al. The theranostics role of mast cells in the pathophysiology of Rosacea. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 6, 324. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2019.00324 (2019).

Taichman, N. S., Young, S., Cruchley, A. T., Taylor, P. & Paleolog, E. Human neutrophils secrete vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62, 397–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlb.62.3.397 (1997).

Schewe, C., Schewe, T., Rohde, E., Diezel, W. & Czarnetzki, B. M. Inhibitory effects of sulfonated shale oils (ammonium bituminosulphonates, Ichthyols) on enzymes of polyenoic fatty acid metabolism. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 286, 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00374208 (1994).

Yamasaki, K. et al. TLR2 expression is increased in rosacea and stimulates enhanced Serine protease production by keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131, 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2010.351 (2011).

Fang, F. C. & Vazquez-Torres, A. Nitric oxide production by human macrophages: there’s NO doubt about it. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282, L941–943. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00017.2002 (2002).

Wozniak, E. et al. The role of mast cells in the induction and maintenance of inflammation in selected skin diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087021 (2023).

Blank, U. et al. Vesicular trafficking and signaling for cytokine and chemokine secretion in mast cells. Front. Immunol. 5, 453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00453 (2014).

Andrabi, S. M. et al. Nitric oxide: physiological functions, delivery, and biomedical applications. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 10, e2303259. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202303259 (2023).

Wang, L., Wu, Y., Jia, Z., Yu, J. & Huang, S. Roles of EP receptors in the regulation of fluid balance and blood pressure. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 875425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.875425 (2022).

Chen, H. Role of thromboxane A(2) signaling in endothelium-dependent contractions of arteries. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 134, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.11.004 (2018).

Farrukh, I. S., Michael, J. R., Summer, W. R., Adkinson, N. F. Jr & Gurtner, G. H. Thromboxane-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction: involvement of calcium. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 58, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1985.58.1.34 (1985).

Zhao, Z. et al. N2-Polarized neutrophils reduce inflammation in Rosacea by regulating vascular factors and proliferation of CD4(+) T cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 142 (e1832), 1835–1844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2021.12.009 (2022).

Li, J., LoBue, A., Heuser, S. K., Leo, F. & Cortese-Krott, M. M. Using diaminofluoresceins (DAFs) in nitric oxide research. Nitric Oxide. 115, 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2021.07.002 (2021).

Hoyt, J. C., Ballering, J., Numanami, H., Hayden, J. M. & Robbins, R. A. Doxycycline modulates nitric oxide production in murine lung epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 176, 567–572. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.567 (2006).

Picosse, F. et al. A comparative exploration of immunohistochemical markers in patients with papulopustular rosacea undergoing treatment with oral isotretinoin versus Doxycycline. Int. J. Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.17420 (2024).

Norregaard, R., Kwon, T. H. & Frokiaer, J. Physiology and pathophysiology of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 in the kidney. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 34, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.krcp.2015.10.004 (2015).

Kanada, K. N., Nakatsuji, T. & Gallo, R. L. Doxycycline indirectly inhibits proteolytic activation of tryptic kallikrein-related peptidases and activation of Cathelicidin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.14 (2012).

Kim, M. et al. Recombinant erythroid differentiation regulator 1 inhibits both inflammation and angiogenesis in a mouse model of rosacea. Exp. Dermatol. 24, 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12745 (2015).

Muto, Y. et al. A. Mast cells are key mediators of cathelicidin-initiated skin inflammation in rosacea. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 2728–2736. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.222 (2014).

Schauber, J. & Gallo, R. L. Expanding the roles of antimicrobial peptides in skin: alarming and arming keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700761 (2007).

Gaudry, M. et al. Intracellular pool of vascular endothelial growth factor in human neutrophils. Blood 90, 4153–4161 (1997).

de Paulis, A. et al. Expression and functions of the vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors in human basophils. J. Immunol. 177, 7322–7331. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7322 (2006).

Taraboletti, G. et al. Bioavailability of VEGF in tumor-shed vesicles depends on vesicle burst induced by acidic pH. Neoplasia 8, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.05583 (2006).

Gangadaran, P. et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from macrophage promote angiogenesis in vitro and accelerate new vasculature formation in vivo. Exp. Cell. Res. 394, 112146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112146 (2020).

Merentie, M. et al. Doxycycline modulates VEGF-A expression: failure of doxycycline-inducible lentivirus ShRNA vector to knockdown VEGF-A expression in Transgenic mice. PLoS One. 13, e0190981. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190981 (2018).

Cerisano, G. et al. Early short-term Doxycycline therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction to prevent the ominous progression to adverse remodelling: the TIPTOP trial. Eur. Heart J. 35, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht420 (2014).

Frka, K. et al. Lentiviral-mediated RNAi in vivo Silencing of Col6a1, a gene with complex tissue specific expression pattern. J. Biotechnol. 141, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.02.013 (2009).

Su, W. et al. Doxycycline-mediated Inhibition of corneal angiogenesis: an MMP-independent mechanism. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 783–788. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10323 (2013).

Demasi, M., Caughey, G. E., James, M. J. & Cleland, L. G. Assay of cyclooxygenase-1 and 2 in human monocytes. Inflammation research: official journal of the European Histamine Research Society… et al.] 49, 737–743, doi:10.1007/s000110050655 (2000).

Schiffmann, S. et al. Comparing the effects of rocaglates on energy metabolism and immune modulation on cells of the human immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065872 (2023).

Samtani, S., Amaral, J., Campos, M. M., Fariss, R. N. & Becerra, S. P. Doxycycline-mediated Inhibition of choroidal neovascularization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 5098–5106. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.08-3174 (2009).

Franco, G. C. et al. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity by Doxycycline ameliorates RANK ligand-induced osteoclast differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Cell. Res. 317, 1454–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.03.014 (2011).

Attur, M. G., Patel, R. N., Patel, P. D., Abramson, S. B. & Amin, A. R. Tetracycline up-regulates COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 production independent of its effect on nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 162, 3160–3167 (1999).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

This work was supported by the Landesoffensive zur Entwicklung wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz (LOEWE) Research Centre for Novel Drug Targets against Poverty-Related and Neglected Tropical Infectious Diseases (DRUID, project E6 for S.S.) (LOEWE/1/10/519/03/03.001(0016)/53), the LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (TBG) (LOEWE/1/10/519/03/03.001(0014)/52), the Fraunhofer Cluster of Excellence Immune mediated diseases (CIMD), the Leistungszentrum innovative Therapeutics (TheraNova) and partially funded by Ichthyol-Gesellschaft Cordes, Hermanni & Co. (GmbH & Co.) KG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS and AR designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. MH, SB and SL performed the research and analyzed the data. AS and AZ designed research. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The study was partially financed by Ichtyhol-Gesellschaft Cordes, Hermanni & Co. (GmbH & Co.) KG. All authors do not have any competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rein, A.S., Henke, M., Brünner, S. et al. Influence of sodium Bituminosulfonate and Doxycycline on signal molecules relevant for rosacea symptoms. Sci Rep 15, 17894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02796-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02796-0