Abstract

Self-compassion, which refers to compassion directed toward oneself, is associated with mental health and well-being. Traditionally, self-compassion has been measured and quantified using rating scales such as the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) and Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS). In recent years, interest in quantifying psychology using text described by people and state-of-the-art natural language processing methods, such as BERT, has increased. In this study, short open-ended free texts were collected from participants asking about their thoughts (general thoughts and those about themselves and others) and behaviors in three challenging situations. Then, a regression model was developed to predict the self-compassion scores (i.e., SCS and CEAS) from free texts with BERT. The self-compassion scores quantified by free texts and BERT highly correlated with the SCS score and certain criterion-related validity. Furthermore, the results suggest that thoughts, behaviors, and levels of self-compassion differ across situations and that the SCS score is related to both cognition (thoughts) and behaviors. The method of psychological quantification using free text may be less prone to priming or bias than measurement using questionnaires. Thus, future studies are encouraged to apply this natural-language-based approach to more diverse samples and other psychological constructs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We experience various difficulties in our daily lives. How we feel and think in such situations varies among individuals. For example, one person may feel lonely in a challenging situation, envious of others, and frustrated by their inadequacy. However, one can also accept oneself with one’s weaknesses and shortcomings and turn compassion toward oneself in such a situation.

In psychology, self-compassion refers to people’s compassion toward themselves when experiencing difficulties, failures, or realizing their inadequacies1. Individuals who have high self-compassion are less likely to experience psychopathology and emotional distress such as depression and stress2 and have more positive emotions and life satisfaction3. Interventions that foster self-compassion, such as Mindful Self-Compassion program and Compassion-Focused Therapy, have also been found to improve well-being and happiness4. Over the past decade or so, self-compassion research has increased exponentially. It is now being conducted in various disciplines, including psychology, psychiatry, nursing, and education5.

Psychological constructs such as self-compassion help in understanding human psychology and behavior and have traditionally been often quantified using self-report rating scales. For example, the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)6 is the most widely used rating scale to measure individual differences in people’s trait self-compassion. The SCS consists of three subscales for compassionate response (CS) and three for uncompassionate response (UCS). The CS subscale consists of three sub-scales: Self-Kindness, which means to value oneself and show kindness even in times of distress; Common Humanity, which means to believe that one is not alone in one’s distress; and Mindfulness, which refers to having a balanced attitude in times of suffering and not being distracted by it. The subscale for UCS is the psychological opposite of each of the three CSs. They are Self-Judgement, which refers to criticizing oneself when suffering; Isolation, which refers to thinking that one is the only one suffering; and Over-identification, which refers to becoming confused and occupied with distressing thoughts and feelings when suffering.

Another measures of self-compassion is the Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS)7. The CEAS measures the engagement in facing and addressing one’s suffering in difficult situations and the action taken to alleviate one’s suffering. The CEAS and SCS are measures that reflect different aspects of self-compassion. For example, the CEAS does not include the elements of Self-Kindness and Common Humanity that the SCS emphasizes5, while the CEAS emphasizes the behavioral aspects of compassion, such as trying to reduce one’s suffering.

Until now, most self-compassion research has been based on rating scales such as the SCS and CEAS, but in recent years, psychology has been growing in the quantification of constructs using open-ended responses and natural language. What motivates this kind of research is the fact that when people express their emotions in their everyday lives, they use natural language rather than numerical scales like rating scales, so the quantification of psychology through natural language measures has high ecological validity8,9,10. People report that they can recall and express their feelings more clearly and accurately when answering open-ended questionnaires than when answering numerical rating scale questions11. In recent years, many psychologists have come to believe that it is important to utilize and develop methods for quantifying psychological constructs that make use of language reports and free descriptions, which have fewer restrictions on expression and allow for a high degree of freedom in responses9,11,12,13,14. This kind of research interest is also spreading to a wide range of fields, including not only psychology but also more accurate assessment in the fields of psychiatry and mental health15,16,17, as well as employee personnel evaluation and well-being improvement in a working environment18,19.

Several attempts have been made to estimate writers’ attitudes (positive/neutral/negative) and basic emotions (e.g., anger/sadness/joy) using natural language as a cue particularly in field of informatics20,21. In recent years, further attempts have been made to estimate and quantify individual differences (latent variables) in more complex psychological constructs17. Kjell et al.8 asked participants, “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your life in general?” The results show that free-text statements obtained from participants can be analyzed using latent semantic analysis to predict their life satisfaction scores8. Kjell et al. also found that participants were asked the prompt, "In the past two weeks, were you depressed or not depressed?", using a method similar to latent semantic analysis, and showed that it could predict participants’ depression to a moderate or higher degree22.

More recently, the deep learning model Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)23, which uses the Transformers architecture widely known for its use in ChatGPT, is increasingly used to quantify psychology. The BERT is an NLP method with machine learning (deep learning). The main difference with GPT-based models is that GPT-based models are better at generating language (e.g., written responses to questions). Conversely, BERT-based models are better at predicting by regression to some numerical value or at classification tasks. In a study quantifying psychological constructs using BERT, Kjell et al. showed that analyzing free statements to the same prompts about life as just described by BERT yielded higher predictive accuracy than traditional latent semantic analysis (r = 0.74)9. Wang et al. also showed that text data on Sina Weibo, a social networking service used primarily in the Chinese-speaking world, predicted psychiatric depression severity and that BERT was more accurate than conventional prediction models such as convolutional neural networks and long and short-term memory neural network24. Tanana et al. showed that BERT achieves higher prediction accuracy in an emotion estimation task based on dialogue recording text in psychotherapy settings, compared to previously used word dictionary-based methods25. Additionally, Simchon et al. showed that BERT could predict posters’ personality traits with moderate accuracy by analyzing content posted on the bulletin board social site Reddit (r = 0.33)26. Recently, we demonstrated that the score of a rating scale measuring attitudes toward ambiguity can be predicted from free descriptions with moderate accuracy (r = 0.41)13.

Despite the growing interest in this research from the perspectives of psychology, psychiatry, informatics, and social implementation, the use and development of methods for quantifying psychology through natural language processing is still in its infancy, and the number of psychological constructs that can be estimated using free descriptions is limited. Apart from basic concepts such as basic emotions20,21 and the Big Five personality traits26,27, the number of psychological constructs that can be estimated from free-form responses is limited to a few, such as depression, anxiety22, life satisfaction/life harmony9, and attitudes towards ambiguity13. To date, there is no natural language processing methods that can quantify self-compassion from free descriptions. Considering that self-compassion is being studied extensively not only in psychology but also in applied fields such as psychiatry, mental health, and working environment5, it is important to develop a method to quantify self-compassion from free descriptions.

We focused on self-compassion, which has been the focus of much research and intervention in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. This study examined the possibility of estimating people’s trait self-compassion from free participant descriptions. Previous studies have used prompts in which participants can answer in a Yes/No manner such as "Are you satisfied with your life or not?" and "In the past two weeks, have you been depressed or not depressed?"8,9,22 or using text data with a large sample size or long description length24,25,26. In this study, we tested whether it is possible to develop a predictive model using a relatively small number of data (approximately 1,000) to accurately predict questionnaire (i.e., SCS and CEAS) scores by collecting short open-ended text data from participants, in which they cannot answer in a Yes/No manner. We used BERT as the model for our predictions. BERT’s bidirectional transformer architecture has the advantage that it can consider both the context before and after a word, and by adjusting the model through fine-tuning, it is possible to obtain embedding representations specific to the collected text. Past research has demonstrated that BERT is superior to other NLP models in its ability to predict psychological constructs from free texts8,9,13,24,27. Additionally, we also checked whether SCS and CEAS predictive scores showed the same correlation patterns with psychopathology and well-being scales (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Satisfaction with Life Scale, and others) as the true scores of the SCS and CEAS questionnaires. This study contributes to the field by demonstrating the feasibility of using a state-of-the-art language model, BERT, to quantify self-compassion from short free-text descriptions with high accuracy. Unlike traditional rating-scale-based methods, this approach offers a more flexible alternative for psychological assessment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. “Methods” section outlines the methods, including participant recruitment, data collection, and the BERT model development. “Results” section presents the relationship between self-compassion scores quantified by BERT and traditional rating scales, highlighting the predictive accuracy and criterion-related validity. “Discussion” section discusses the implications of our findings, limitations, future research directions, and conclusions.

Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Education at Kyoto University (CPE-601) and conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We obtained informed consent from the study participants before their participation. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

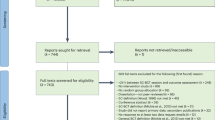

This survey was conducted online. Participants were recruited through CrowdWorks (https://crowdworks.jp), an online crowdsourcing platform primarily populated by Japanese nationals. This study used a large crowd worker pool from a crowdsourcing service because fine-tuning the BERT model requires a relatively large data size (see below). To participate in the survey, participants had to be native speakers of Japanese and at least 18 years old. No exclusion criteria were enforced for participants. Participants responded to open-ended questions (in Japanese), rating scales, and demographic data according to the procedures described in the next section. As the survey was administered through Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com), participants who completed the survey to the end were guaranteed to have answered all questions. Therefore, none of the 823 participants who completed the survey had missing values. From these 823 participants, we excluded participants who answered incorrectly on the attention check, who answered from the same IP address, and one who reported a glitch in keyboard entry, resulting in a final sample of 780 participants.

Regarding the demographic data on the participants, gender was 357 males, 418 females, and five unknown. The mean age was 43.0 years, with a standard deviation of 10.6 years, a minimum of 19 years, and a maximum of 75 years. The final education level was middle school (n = 11), high school (n = 186), junior college/technical college (n = 103), university (n = 423), graduate school (n = 46), and unknown (n = 11).

The main objective of this study was to construct a BERT regression model to predict the scores of rating scales (i.e., SCS and CEAS) from open-ended text data obtained from participants. No clear standard exists for the sample size required to construct a BERT model; it depends on the task BERT solves. However, Sun et al. showed that while a larger sample size improves accuracy, a sample of 100–1000 cases may be sufficient for practical use28. Therefore, we aimed to collect data from about 800 cases in this study.

Survey procedure

Participants were presented with 12 open-ended prompts (described below), one at a time, and asked to write an open-ended response. After each prompt, the participant had to type a free-response statement of at least 40 characters, and 45 seconds had to elapse before moving on to the next response. Participants then responded to rating scales (see below). The survey also measured several rating scales not used in this study (see Supplementary Methods). Finally, demographic data (gender, age, and last education) were collected to complete the survey.

Prompts presented to participants

Twelve prompts, which consisted of four questions in three situations, were presented on the screen. Table 1 shows an English translation of the Japanese prompts presented to the participants. The situations were set up referencing the SCS items: a situation in which the participants are experiencing suffering, a situation in which they have realized their shortcomings or inadequacies, and a situation in which they have made a big mistake. Regarding the four questionnaire statements, three of them related to the cognitions that the SCS was assumed to be primarily measuring (i.e., general thoughts, thoughts about oneself, and thoughts about others), and one related to the behaviors that the CEAS was supposed to measure (how one acts in difficult situations).

The specific prompts used in this study were designed to capture various dimensions of self-compassion. These prompts were developed based on the constructs measured by the SCS and the CEAS, which emphasize cognitive and behavioral aspects of self-compassion. Specifically, Question 1 (see Table 1) was designed to reflect mainly the Mindfulness component of the SCS and the degree of engagement with suffering in the CEAS by asking about general thoughts in difficult situations. Questions 2 and 3, which ask about thoughts about oneself and others, reflect mainly Self-Kindness and Common Humanity of the SCS. Finally, Question 4 is related to actions to alleviate suffering, which CEAS particularly emphasizes. Also, the fact that our prompts involve three different difficult situations reflects a situational approach to measuring self-compassion29,30, asking participants about their thoughts and actions when they experience suffering, notice their shortcomings, or make mistakes. These situations were chosen because they are typical and common triggers for self-compassion5,6 and provide a rich context for eliciting a variety of meaningful responses.

Rating scales

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

The SCS is the most widely used measure of people’s trait self-compassion. The original version of this scale was developed by Neff6. The Japanese version of the SCS, translated by Arimitsu (2014) and confirmed for internal consistency, retest reliability, and construct validity, consists of 26 items with six subscales, as in the original version31. Each of the six subscales is composed of three sub-scales: Self-Kindness (five items, e.g., “I try to be loving towards myself when I’m feeling emotional pain”), Self-Judgement (five items, e.g., “I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies”), Common Humanity (four items, e.g., “When things are going badly for me, I see the difficulties as part of life that everyone goes through”), Isolation (four items, e.g., “When I think about my inadequacies, it tends to make me feel more separate and cut off from the rest of the world”), Mindfulness (four items, e.g., “When something upsets me, I try to keep my emotions in balance”), and Over-identification (four items, e.g., “When I’m feeling down, I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that’s wrong”). Participants respond to these items using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The subscale score is calculated by averaging the response values for each item. Higher scores indicate greater self-compassion for the Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness subscales. Conversely, higher Self-Judgement, Isolation, and Over-identification subscale scores indicate less self-compassion. The total score of the SCS is obtained by averaging the scores for Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness subscales and the inverted scores for the Self-Judgement, Isolation, and Over-identification subscales, respectively. The total SCS score indicates that the higher the score, the higher the self-compassion.

Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS)

The CEAS is a questionnaire designed to measure self-compassion, compassion for others, and compassion received from others, and only the self-compassion subscale was used in this study. The original version of this scale was developed by Gilbert et al.7; the Japanese version of the CEAS, translated by Asano et al.32 and confirmed for internal consistency, retest reliability, and construct validity, consists of seven items. The CEAS consists of items measuring engagement in self-compassion (three items, e.g., “I am motivated to engage and work with my distress when it arises”) and action (four items, e.g., “I direct my attention to what is likely to be helpful to me”). Participants respond to these items using a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 10 (always). The original version of the CEAS consists of the engagement and action subscales. However, the Japanese version has been confirmed to have a one-factor structure for all seven scale items. Thus, only the scale’s total score was used for analysis in this study. The total CEAS score is calculated by taking the average of the response values for all seven items.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a scale used to assess people’s level of depression. The original version of this instrument, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), was developed by Spitzer et al.33. The PHQ was initially designed to diagnose and evaluate a variety of psychiatric symptoms, including depression, and the PHQ-9 consists of nine questions related to depression and major depressive disorder. This study used the Japanese version of the PHQ-9. Its reliability and validity were confirmed by Muramatsu et al.34. The scale consists of nine items (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”), and participants are asked to indicate how often they experienced the symptoms indicated in each item in the past week using a four-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), or 3 (nearly every day).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS is a scale used to assess people’s daily perceived stress. The original version of this scale was developed by Cohen et al.35. In this study, we used the Japanese version of the PSS, which was translated into Japanese by Sumi36. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the PSS have been confirmed. The scale consists of 10 items (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?”). Participants responded on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) to indicate how often they experienced each item in the past month.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

The PANAS is a scale used to assess negative and positive emotions that people experience daily. Watson et al.37 developed the original version of the scale. In this study, we used the Japanese version of the PANAS, which was translated into Japanese by Sato and Yasuda38 and confirmed for reliability and validity. The PANAS consists of eight items for each of the negative (e.g., “Distressed”) and positive (e.g., “Interested”) affect subscales, and participants responded to each item on a six-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS is a scale used to assess people’s life satisfaction. Diener et al.39 developed the original version of this scale. In this study, we used the Japanese version of the SWLS, which was translated into Japanese by Sumino40 and confirmed for reliability and validity. The scale consists of five items (e.g., “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”); participants responded to the extent to which each item applies to them on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Data analysis

Calculation of descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients

First, the number of characters in the free texts and the sample statistics for each rating scale (mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha) were calculated, followed by the correlations between the rating scales.

Development of BERT regression models

We then developed BERT regression models to predict the SCS total scores, the six SCS subscale scores, and CEAS total scores from free texts. The models were developed using (a) free texts for each of the 12 prompts, (b) free texts combined with each of the three situations, and (c) free texts combined with each of the four questions. Thus, for each questionnaire (SCS total, SCS subscales, and CEAS total), 12 + 3 + 4 = 19 prediction models were developed. Examples of free texts and combined texts described by a participant (translated into English) are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

In building the BERT regression model, one can use the pre-trained embedding as is or after fine-tuning. Previous research suggests that fine-tuned models have fewer errors than pre-trained ones when texts consist of many negative affect words41. Because we expected the texts we collected to contain many negative emotional words, we followed the strategy of fine-tuning BERT’s pre-trained model. Our model was developed by fine-tuning a Japanese pre-trained model (https://huggingface.co/cl-tohoku/bert-base-japanese-v3) with the collected free text data. We used the latest version of the model pre-trained on a large Japanese dataset (CC-100 and Wikipedia). We implemented a program for fine-tuning using Python's Transformers package. The optimizer for fine-tuning was AdamW. The learning rate scheduler is linear decay. The mean square error was used as the loss function. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to measure developed models’ accuracy between a questionnaire score’s true and predicted values. Hyperparameters tried during fine-tuning were {2e−5, 3e−5, 4e−5, 5e−5} for learning rate, {8, 16} for batch size, and {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} for the number of epochs. The warm-up rate was set to 0.1. Thus, we calculated 4*2*5 = 40 hyperparameter combinations. As the text length for all participants was below the BERT processing limit of 512 tokens, no truncation was performed. (However, only when the texts were combined did the number of tokens exceed 512 for one participant. Therefore, the model was developed after excluding this participant from the predictions based on the combined texts.) In this study, text length was not normalized. This is because normalizing text length through truncation could introduce artificial patterns that do not naturally exist in free descriptions. Moreover, the length of participants’ responses itself may carry psychological information in the context of this task. For instance, the extent to which individuals elaborate on their thoughts or provide detailed accounts could reflect underlying traits such as self-awareness or cognitive processing styles. Normalizing text length could potentially strip away this valuable information, so we decided not to normalize text length.

The nested k-fold cross-validation (nested CV) was used to find the optimal combination of hyperparameters and to evaluate the developed models’ accuracy. Although a nested CV is computationally more expensive than a classical k-fold CV, it has less bias in estimation accuracy42. It is particularly effective in machine learning on relatively small samples43. Importantly, a nested CV allows one to estimate the model’s predictive accuracy for data independent of the data used to develop the model while preventing over-training or over-fitting. In this study, k = 5. In nested five-fold CV, the dataset is initially shuffled and then split into five sub-datasets. The subsequent process consists of an outer loop and inner loops. In an outer loop, the entire data set is divided into model development data and test data, and the accuracy of the model developed with the development data is estimated with the test data. In an inner loop, the development data is divided into training and validation data. The optimal combination of hyperparameters is selected, and the model is developed using this combination. Details of the algorithms performed in the outer and inner loops are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Assessing the accuracy of the developed models

The developed models’ accuracy was evaluated using the median of the five correlation coefficients between true and predicted scores (n = 780/5 = 156) obtained in the outer loop of nested CV. An uncorrelated test (df = 154) for the median correlation coefficient was performed to obtain a p-value and 95% confidence interval. P < 0.05 was considered a significant prediction. The widely used Cohen44 guideline for interpreting effect sizes was used to evaluate the accuracy of the predictions: low accuracy when 0.10 < r < 0.30, moderate accuracy when 0.30 < r < 0.50, and high accuracy when 0.50 < r.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations of questionnaire scales

The descriptive statistics (M, SD, and Cronbach’s alpha) and correlations for each variable are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Examples of free texts

Supplementary Table 3 provides examples of free and combined texts described by a participant.

Length of free texts

The median and range (minimum and maximum) of the length (the number of characters) of participants’ free texts and their combined texts are presented in Supplementary Table 4. The median length of participants’ free texts for each prompt was approximately 50–55 characters. Some participants wrote much longer (up to 250–400 characters).

Prediction of the SCS total score

The Pearson correlation coefficients and their confidence intervals between the predicted scores and the true values when the SCS total scores were predicted using each text (12 texts), combined texts per situation (three texts), and combined texts per question (four texts), are presented in Table 2.

Predictions by text were generally able to predict the SCS total score with moderate or better accuracy (r > 0.30) for all texts. Predictions made by the texts on Question 2 (thoughts about oneself) achieved high accuracy (r > 0.50) in most cases. Prediction accuracy with the text for the prompt of Situation 2 (when realizing one’s flaws) x Question 2 was particularly high (r = 0.57).

Predictions based on texts combined by situation (right-most column in Table 2) were all more accurate than a single text for that situation. Similarly, predictions based on texts combined by question (the bottom row of Table 2) were all more accurate than a single text for that question. In particular, the combined text for Question 2 achieved considerably higher prediction accuracy (r = 0.67).

Prediction of the subscale scores of the SCS

The Pearson correlation coefficients and their confidence intervals between the predicted scores and the true values, when the six SCS subscales scores were predicted using combined texts per situation (three texts) and combined texts per question (four texts) are presented in Table 3. Prediction results by each text were omitted. Each combined text predicted each subscale score of the SCS with moderate or better accuracy. For almost all subscales, the combined text of Question 2 (Thoughts about oneself) showed the best prediction accuracy.

Prediction of the CEAS score

Table 4 provides the Pearson correlation coefficients and their confidence intervals between the predicted scores and the true values when the CEAS total scores were predicted using each text (12 texts), combined texts per situation (three texts), and combined texts per question (four texts).

Predictions by each text were generally of medium accuracy for Questions 1 (general thoughts) and 4 (actions). Predictions based on Question 2 (thoughts about oneself) had low to moderate accuracy, while that of Question 3 (thoughts about other people) was generally low.

Predictions by text combined by situation (right-most column in Table 4) were all more accurate than a single text for that situation, as were predictions of SCS total score. Similarly, predictions based on the text combined per question statement (the bottom row of Table 4) all achieved higher accuracy than a single text for that question statement. The combined text for Questions 1, 2, and 4 predicted CEAS scores moderately well. Conversely, the prediction accuracy of Question 3 remained low.

Relationship between the true and predicted scores of the SCS/CEAS and other variables

Table 5 presents the correlation coefficients between the BERT prediction scores of the SCS and CEAS and other variables and those between the true scores of the SCS and CEAS. We used the prediction scores from the text that achieved the highest prediction accuracy (r) in each of SCS and CEAS (SCS: Question 2 combined text (r = 0.67); CEAS: Situation 1 combined text (r = 0.42)).

The correlation pattern (i.e., the sign or significance of the correlation coefficients) between the SCS/CEAS BERT prediction scores and the other variables was similar to the true scores on the SCS/CEAS. However, the absolute values of the correlation coefficients between the predicted scores and the other variables tended to be smaller than the absolute values of the correlation coefficients between the true scores.

Discussion

People often use verbal expressions to express their psychological states10. Recently, the estimation and quantification of psychology using verbal expressions have attracted attention in psychology, informatics, and psychiatry. Considering these research trends, this study attempted to predict participants’ trait self-compassion by developing a BERT regression model using a relatively small size (about 1000) of short open-ended descriptive data, which has a higher degree of freedom in responding than in previous studies. Consequently, we developed a model that predicted SCS scores with high accuracy (r = 0.67) and CEAS scores with moderate accuracy (r = 0.42).

Correlations between rating scales

Among the SCS subscales, a positive correlation was found between those related to CS and those related to UCS. An inverse association was found between subscales reflecting CS and those reflecting UCS. This result was similar to previous studies6. The CEAS also showed a strong positive correlation with the subscales reflecting CS of the SCS and a moderate negative correlation with the subscales reflecting UCS. This finding also replicated the results of a previous study7. Furthermore, self-compassion was negatively associated with psychopathology and other measures (i.e., depression, stress, negative affect) and positively associated with well-being-related measures (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction), consistent with previous studies2,3,7.

Prediction of the SCS total score

In terms of the prediction of total SCS scores by each text, the texts related to Questions 1 (general thoughts), 2 (thoughts about self), 3 (thoughts about others), and 4 (actions) all predicted SCS scores with moderate to high accuracy. The prediction accuracy of the texts for Question 2 was relatively high, with the highest prediction accuracy (r = 0.57) obtained with free texts for the prompt of Situation 2 (when noticing one’s shortcomings) x Question 2. Notably, relatively high accuracy was achieved although each of the 12 texts was short, with a minimum of 40 characters and a median of 50–55 characters, and the prompts asking for free texts had a degree of freedom in their responses (i.e., they could not be answered with Yes/No).

Predictions of SCS total scores by texts combined with situations were more accurate than predictions by text alone. This result is consistent with Kjell et al.9, suggesting that combining multiple free texts about different things, such as thoughts about oneself, others, and actions, increases the amount of information in the texts (or, more precisely, the amount of information that contributes to predicting the total SCS score) more than the individual free texts.

Predictions by the combined texts for each question text also showed improved accuracy compared to each text. For example, compared to the prediction accuracy with a single text (r = 0.57) for Situation 2 × Question 2, the prediction accuracy with the combined text for Question 2 (r = 0.67) improved by approximately 0.1 points, or 12.4% in terms of variance explained. Thus, we can assume that even when the free texts about different situations were combined for each question text, more information was obtained from the combined texts that were useful to predict the total SCS score. This result suggests that the descriptions of these situations within the same individual may have differed to a certain extent and that the variance between the descriptions may have contributed to the prediction of SCS scores. If most participants had given similar responses in different situations, combining texts about them would not have increased useful information for prediction. This fact suggests that the degree of self-compassion within individuals may differ in different situations. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that the factor loadings of the SCS questions differ between items related to general life challenges and personal inadequacy5. Moreover, the results are consistent with previous research showing that the degree of self-compassion varies within individuals depending on the situation and context30.

Interestingly, the combined text of Question 4, asking about behavior, predicted the SCS total score with higher accuracy than r = 0.50. The majority of the SCS scale items are related to cognition in distressing situations and, in contrast to the CEAS, there appear to be few items that directly measure behavior. Nevertheless, the free-response statements about behavior predicted the SCS total score with relatively high accuracy. This result suggests that people’s behaviors after distressing situations are significantly related to their self-compassion, measured by the SCS. This result would be consistent with previous meta-analyses showing that self-compassion, as measured by the SCS, is associated with adaptive coping45 and health-promoting behaviors46.

Prediction of the SCS subscales scores

The combined texts could predict each subscale score with moderate to high accuracy. Predictions based on the combined texts of Question 2 tended to be higher than predictions based on the combined text of the other questions. Predictions by Question 2 predicted all subscales with a high accuracy of about r = 0.5–0.6. Overall, predictions of SCS subscale scores tended to be less accurate than predictions of the SCS total score. This result may reflect that the SCS subscale scores were less reliable than the total ones (see alpha coefficients in Supplementary Table 1) or because self-compassion, as a superordinate concept of the subscales, was better suited for free-text prediction than the constructs that the subscales were measuring.

The prediction accuracies of certain SCS subscales varied. For example, the Self-Judgement and Over-Identification subscales exhibited higher prediction accuracies than others. This result aligns with the relatively high reliability (as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients; see Supplementary Table 1) of these subscales, which are the prediction targets. In contrast, despite its high alpha coefficient, the Self-Kindness subscale did not show high predictive accuracy. This may be due to cultural factors specific to the Japanese context. In Japan, where self-criticism or self-effacement is sometimes socially acceptable and adaptive47, attitudes and behaviors reflecting self-kindness may be less familiar or less explicitly expressed in free-text responses. Consequently, the model may have struggled to identify consistent signals for predicting this subscale. This highlights the need for further exploration of how cultural norms influence the expression of self-compassion traits.

Prediction of the CEAS total score

Predictions by each text predicted CEAS total scores with low to moderate accuracy. Moderate (r > 0.30) predictive accuracy was achieved by the texts for Questions 1 and 4. The CEAS measures engagement in recognizing and confronting distress under challenging situations and action to relieve that distress. Question 1 asks about general thoughts in difficult situations and is presumed to be related to engagement; Question 4, which asks about behaviors, is presumed to be related to action. Thus, the predictive accuracy of the texts for these two questions was high. Unlike Questions 1 and 4, the prediction accuracy of Question 3, which asked about thoughts toward others, remained low. This finding suggests that the association between CEAS scores and perceptions of other people in situations in which one is suffering is weak. The CEAS does not include items on common humanity/isolation as in the case of the SCS5. The fact that the predictive accuracy of each question is different for SCS and CEAS indicates that the two scales have different relationships with cognitions and behaviors in challenging situations.

Predictions based on the situation-specific combined texts improved in accuracy over predictions based on a single free text. This trend is similar to the SCS results, suggesting that combining open-ended texts from different questions may have increased the information used to predict CEAS scores. Similarly, combining the free texts for each question improved accuracy over predicting by a single free text. This finding is similar to those obtained when predicting the SCS total score. It is also consistent with the result30 that the degree to which self-compassion occurs depends on the context and situation.

Relationship between the true and predicted scores of the SCS/CEAS and other variables

The correlation patterns between the predicted SCS and CEAS scores and other variables (depression, stress, negative and positive affect, and life satisfaction) were similar to that found for the true scores of each questionnaire scale (although the absolute values of the correlation coefficients tended to be smaller than the true scores). This result suggests that the scores quantified from the free texts have a certain criterion-relevant validity.

The study’s contribution

This study showed that BERT can predict participants’ trait self-compassion with high accuracy by analyzing short open-ended statements collected by presenting prompts asking about thoughts and actions in challenging situations. The text data used in the study were collected by prompts with more open-ended responses than in previous studies, and highly accurate prediction of psychological constructs was found to be possible even with short open-ended responses that cannot be answered with a Yes/No answer and with relatively small training data (about 1000). Furthermore, the prediction scores obtained by BERT were shown to have a certain criterion-relevant validity. Furthermore, as in previous studies9, we found that combining the participants’ free descriptions resulted in higher accuracy, indicating that when quantifying psychological constructs based on free descriptions, it is better to collect several different descriptions.

Traditionally, rating scales have been widely used in psychological research to measure psychological constructs. However, in the real world, when people express their psychological states, they usually use natural language with a degree of freedom10. Moreover, people believe that open-ended responses allow them to recall their psychology more clearly and express it more accurately than rating scales and that some people prefer open-ended responses to questionnaires11. Of course, questionnaire scales have the advantage of being quick and easy to administer. This study demonstrates that quantifying human psychology objectively based on open-ended statements is possible. Furthermore, its results suggest that methods for quantifying psychology through open-ended statements can complement conventionally used rating scales9.

The prompts used in this study ambiguously asked about thoughts and actions in challenging situations. They were characterized by their lack of presenting the concept of self-compassion directly. However, a rating scale such as the SCS measures self-compassion by presenting the concept of self-compassion itself (e.g., "be kind to yourself") and then asking the participants to rate themselves on whether they fit the concept. Presenting the self-compassion concept in this way may serve as a kind of priming to participants or cause them to have some preconceived notion48. In East Asia, including Japan, where self-criticism is sometimes considered a virtue and the SCS score is lower than the West49, self-compassion is an unfamiliar concept and may serve as a more robust primer. Additionally, in contexts such as experiments and interventions, direct use of questionnaire measures, such as the SCS, may raise the issue of demand characteristics50, in which participants may take on the experimenter’s intentions. A natural language measure such as the one used in this study does not directly present the concept of self-compassion to participants. Thus, participants may find it challenging to guess what is being measured, thus reducing the priming and demand characteristics problems. Therefore, quantification of self-compassion through natural language, in addition to conventional rating scales, is expected to be used in future surveys, experiments, and interventions.

Furthermore, analysis with BERT can reveal whether the rating scales (and their scores) are associated with free descriptions of people’s behavior and other aspects51. The present study also found results suggesting that thoughts and actions in difficult situations and the degree to which self-compassion occurs may differ from situation to situation to a certain degree and that the SCS score is significantly related not only to cognition (thoughts) but also behavior. Additionally, the CEAS, unlike the SCS, was found to be less related to thoughts about others and oneself (compared to general thoughts). This finding revealed how the two scales reflect different aspects of self-compassion. Thus, this study also made a theoretical contribution regarding self-compassion based on the texts described by the participants themselves.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the theoretical understanding of the benefits of combining multiple textual inputs for psychological prediction tasks compared to individual text analysis. While individual texts provide valuable information, combining multiple texts increases the diversity and richness of input data, which can enhance predictive accuracy. This approach leverages the variability across different contexts, reflecting the multifaceted nature of psychological constructs such as self-compassion. For instance, the combination of texts from varied situations, such as experiences of suffering, personal shortcomings, and significant mistakes, captures the various situational aspects of self-compassion. This finding aligns with the conceptualization of self-compassion as a dynamic trait that varies across contexts and situations52. By aggregating multiple perspectives from the same individual, we can achieve a more comprehensive and nuanced measurement, which is difficult to obtain from isolated texts.

As demonstrated in this study, the framework for psychometric measurement using free-response methods can be applied to self-compassion and various other psychological constructs. This approach is still in its infancy, and the psychological constructs that can be measured using free-response methods are limited to a few. It is hoped that in the future, more psychological constructs can be measured using free-response methods.

Limitations and future directions

One limitation of this study is the relatively small dataset for fine-tuning the BERT model. While small datasets can risk overfitting or limited generalizability, we mitigated these issues by employing a nested cross-validation approach rather than standard cross-validation. Unlike standard cross-validation, nested cross-validation is computationally intensive but provides a more robust estimation of model performance42,43. This method reduces the risk of overfitting and minimizes the potential for overestimating the model’s accuracy when applied to unseen data. However, the current dataset was collected from a specific population of Japanese crowd-sourcing platform users aged 18 to 70. It may not represent a broader and more diverse demographic and psychological population. Additionally, expression related to self-compassion may vary across cultures. For example, in East Asian cultures, including Japan, self-compassion may be influenced by social norms that sometimes value self-effacement and humility47. Such cultural factors could affect how participants articulate their thoughts and behaviors in challenging situations, thereby shaping the free-text data used to train the model. The BERT model fine-tuned on Japanese free-text data may perform differently when applied to data from individuals in cultures with different norms and values surrounding self-compassion. Thus, future research could expand to larger and more diverse datasets, including samples from different demographic backgrounds, cultural contexts, clinical groups, and psychological profiles, which would improve the robustness and applicability of BERT-based predictions and ensure that the utility of the model extends beyond the specific sample used in this study.

While BERT has demonstrated superior performance in recent studies quantifying psychological constructs8,9,13,24,27, this study did not directly compare its performance to other NLP models or simpler alternatives. BERT’s bidirectional transformer architecture and fine-tuning capabilities make it highly effective for capturing complex linguistic patterns in free-text responses. It was selected as the primary model for this research. Previous research has suggested that fine-tuning is useful for prediction tasks involving texts with a high prevalence of negative affect words41, we adopted an approach involving fine-tuning the pre-trained BERT model. However, future research can explore the potential of alternative models. For example, methods such as latent semantic analysis or pre-trained language models without fine-tuning53 could be considered. These approaches often require less computational resources and might provide comparable predictive accuracy in certain scenarios. Investigating such alternatives would offer practical insights, especially for researchers seeking a balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

Conclusion

This study provides novel insights into quantifying self-compassion using free descriptions and BERT. This methodological approach complements traditional rating-scale-based measures by offering a more flexible alternative for psychological assessment, paving the way for broader applications. This approach could be extended to other psychological constructs, offering a robust framework for analyzing free-text data in future studies and providing a valuable tool for researchers and practitioners. Future research should explore the application of this methodology across diverse populations and psychological constructs to further validate and refine its utility. Expanding the dataset size and diversity could also improve predictive accuracy and generalizability.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2, 85–101 (2003).

MacBeth, A. & Gumley, A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 545–552 (2012).

Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O. & Garbade, S. The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 7, 340–364 (2015).

Ferrari, M. et al. Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness 10, 1455–1473 (2019).

Neff, K. D. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 74, 193–218 (2023).

Neff, K. D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2, 223–250 (2003).

Gilbert, P. et al. The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. J. Compassionate Health Care https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3 (2017).

Kjell, O. N. E., Kjell, K., Garcia, D. & Sikström, S. Semantic measures: Using natural language processing to measure, differentiate, and describe psychological constructs. Psychol. Methods 24, 92–115 (2019).

Kjell, O. N. E., Sikström, S., Kjell, K. & Schwartz, H. A. Natural language analyzed with AI-based transformers predict traditional subjective well-being measures approaching the theoretical upper limits in accuracy. Sci. Rep. 12, 3918 (2022).

Tausczik, Y. R. & Pennebaker, J. W. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 29, 24–54 (2010).

Sikström, S., Pålsson Höök, A. & Kjell, O. Precise language responses versus easy rating scales—Comparing respondents’ views with clinicians’ belief of the respondent’s views. PLoS ONE 18, e0267995 (2023).

Herderich, A., Freudenthaler, H. H. & Garcia, D. A computational method to reveal psychological constructs from text data. Psychol. Methods https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000700 (2024).

Hitsuwari, J., Okano, H. & Nomura, M. Predicting attitudes toward ambiguity using natural language processing on free descriptions for open-ended question measurements. Sci. Rep. 14, 8276 (2024).

Zhou, H., Wang, M., Yang, Y. & Majka, E. A. Face masks facilitate discrimination of genuine and fake smiles—But people believe the opposite. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2024.104658 (2024).

Crema, C., Attardi, G., Sartiano, D. & Redolfi, A. Natural language processing in clinical neuroscience and psychiatry: A review. Front. Psychiatry 13, 946387 (2022).

Malgaroli, M., Hull, T. D., Zech, J. M. & Althoff, T. Natural language processing for mental health interventions: A systematic review and research framework. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 309 (2023).

Kjell, O. N. E., Kjell, K. & Schwartz, H. A. Beyond rating scales: With targeted evaluation, large language models are poised for psychological assessment. Psychiatry Res. 333, 115667 (2024).

Kumar, B., Nagpal, A., Singh Bisht, Y., Sreenivasgoud, P., Qureshi, K. & Lourens, M. Using natural language processing for biometric identification optimizatoin. In 3rd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE) 993–998 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACITE57410.2023.10182448 (IEEE 2023).

Sharma, R., Kharade, M. A., Kamthe, S. S., Vasudevan, A. R. & Dalvi, S. Sentiment analysis: Decoding workspace emotions. In MIT Art, Design and Technology School of Computing International Conference (MITADTSoCiCon), 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1109/MITADTSoCiCon60330.2024.10575174 (IEEE, 2024).

Bollen, J., Mao, H. & Zeng, X. Twitter mood predicts the stock market. J. Comput. Sci. 2, 1–8 (2011).

Pang, B., Lee, L. & Vaithyanathan, S. Thumbs up? Sentiment classification using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the ACL-02 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing – EMNLP, 79–86 https://doi.org/10.3115/1118693.1118704 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002).

Kjell, K., Johnsson, P. & Sikström, S. Freely generated word responses analyzed with artificial intelligence predict self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and worry. Front. Psychol. 12, 602581 (2021).

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pretraining of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In NAACL HLT Proceedings of the Conference vol 1 (2019) Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies 2019–2019.

Wang, X. et al. Depression risk prediction for Chinese microblogs via deep-learning methods: Content analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 8, e17958 (2020).

Tanana, M. J. et al. How do you feel? Using natural language processing to automatically rate emotion in psychotherapy. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 2069–2082 (2021).

Simchon, A., Sutton, A., Edwards, M. & Lewandowsky, S. Online reading habits can reveal personality traits: Towards detecting psychological microtargeting. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad191 (2023).

Pradnyana, G. A., Anggraeni, W., Yuniarno, E. M. & Purnomo, M. H. Fine-tuning IndoBERT model for big five personality prediction from Indonesian social media. In International Seminar on Intelligent Technology and Its Applications (ISITIA) 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISITIA59021.2023.10221074 (IEEE 2023).

Sun, C., Qiu, X., Xu, Y. & Huang, X. How to fine-tune BERT for text classification?. Lect Notes Comput. Sci. 11856, 194–206 (2019).

Miyagawa, Y. & Taniguchi, J. Development of the Japanese version of the Self-Compassionate Reactions Inventory. Jpn. J. Psychol. 87, 70–78 (2016).

Zuroff, D. C. et al. Beyond trait models of self-criticism and self-compassion: Variability over domains and the search for signatures. Pers. Individ. Dif. 170, 110429 (2021).

Arimitsu, K. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale. Jpn. J. Psychol. 85, 50–59 (2014).

Asano, K. et al. The development of the Japanese version of the compassionate engagement and action scales. PLoS ONE 15, e0230875 (2020).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K. & Williams, J. B. W. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282, 1737–1744 (1999).

Muramatsu, K. et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire, Japanese Version: Validity according to the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychol. Rep. 101, 952–960 (2007).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396 (1983).

Sumi, K. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Jpn. J. Health Psychol. 19, 44–53 (2006).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070 (1988).

Sato, A. & Yasuda, A. Development of the Japanese version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scales. Jpn. J. Pers. 9, 138–139 (2001).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75 (1985).

Sumino, Z. Jinsei ni taisuru manzoku syakudo (the Satisfaction With Life Scale) nihongoban sakusei no kokoromi [Attempt to develop a Japanese version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale] 192. In Annual convention of the Japanese Association of Educational Psychology vol. 36 (1994).

Ganesan, A. V., Matero, M., Ravula, A. R., Vu, H. & Schwartz, H. A. Empirical evaluation of pre-trained transformers for human-level NLP: The role of sample size and dimensionality. Proc Conf 2021, 4515–4532. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.naacl-main.357 (2021).

Varma, S. & Simon, R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinform. 7, 91 (2006).

Vabalas, A., Gowen, E., Poliakoff, E. & Casson, A. J. Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size. PLoS ONE 14, e0224365 (2019).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science (Routledge Academic, 1988).

Ewert, C., Vater, A. & Schröder-Abé, M. Self-compassion and coping: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 12, 1063–1077 (2021).

Phillips, W. J. & Hine, D. W. Self-compassion, physical health, and health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 15, 113–139 (2021).

Aruta, J. J. B. R., Antazo, B. G. & Paceño, J. L. Self-stigma is associated with depression and anxiety in a collectivistic context: The adaptive cultural function of self-criticism. J. Psychol. 155, 238–256 (2021).

Sheng, H., Wang, R. & Liu, C. The effect of explicit and implicit online self-compassion interventions on sleep quality among Chinese adults: A longitudinal and diary study. Front. Psychol. 14, 1062148 (2023).

Arimitsu, K., Hitokoto, H., Kind, S. & Hofmann, S. G. Differences in compassion, well-being, and social anxiety between Japan and the USA. Mindfulness 10, 854–862 (2019).

Orne, M. T. On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. Am. Psychol. 17, 776–783 (1962).

Nilsson, A. H., Hellryd, E. & Kjell, O. Doing well-being: Self-reported activities are related to subjective well-being. PLoS ONE 17, e0270503 (2022).

Zuroff, D. C., Fournier, M. A., Patall, E. A. & Leybman, M. J. Steps toward an evolutionary personality psychology: Individual differences in the social rank domain. Can. Psychol. 51, 58–66 (2010).

Kjell, O., Giorgi, S. & Schwartz, H. A. The text-package: An R-package for analyzing and visualizing human language using natural language processing and transformers. Psychol. Methods 28, 1478–1498 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editing company Editage (https://www.editage.com/) for their work.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research and JSPS KAKENHI- (JSPS KAKENHI Grant 22H01103) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors were involved in the study design and contributed to the final manuscript. H.O. performed the data collection and analysis. H.O. drafted the manuscript under the supervision of D.K. and M.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okano, H., Kawahara, D. & Nomura, M. Advancing psychological assessment: quantifying self-compassion through free-text responses and language model BERT. Sci Rep 15, 25778 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02801-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02801-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Decoding the mind of self-compassion through a topic modeling analysis of 9000+ free-text narratives

Scientific Reports (2025)