Abstract

This study examines the exergy analysis and exergy destruction of a solar still (SS) at varying seawater depths (1, 2, and 3 cm) with and without silicon carbide (SiC) as an energy enhancement material. The SS with SiC addition achieved daily production rates of 5.64 kg, 5.1 kg, and 3.06 kg at seawater depths of 1, 2, and 3 cm, respectively. In contrast, the SS without SiC addition achieved daily production rates of 4.68 kg, 3.9 kg, and 3.2 kg, respectively. The addition of SiC increased the yield by about 20% at a seawater depth of 1 cm and by 31% at a seawater depth of 2 cm but decreased the yield by 4% at a seawater depth of 3 cm. The thermal efficiencies of SS with SiC at 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm are 44.2%, 39.9%, and 23.8%, respectively. In contrast, the thermal efficiencies of SS without SiC are 35.7%, 29.7%, and 24.3%, respectively. Likewise, the exergy efficiency of the SS containing SiC was 3.99%, 3.41%, and 1.76% at seawater depths of 1, 2, and 3 cm, respectively, while that of the SS without SiC reached 2.98%, 2.35%, and 1.8%, respectively. The most significant exergy loss in the SS basin was observed at 1 cm seawater depth, with values of 4231 W/m² and 4459 W/m² for SS with and without SiC, respectively. Furthermore, the most significant energy loss in saline water at a 3 cm seawater depth was 1640 W/m² for SS with SiC and 1546 W/m² for SS without SiC, while the smallest energy loss in saline water at a 1 cm seawater depth was 1138 W/m² and 626 W/m², respectively. The study concluded that maximum energy loss occurred in salt water at a seawater depth of 3 cm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is an essential resource that makes our existence on earth. Humans and all living things, including plants, depend on water for survival. Particularly, humans require fresh drinking water for a better and healthier life. Although the world is surrounded by sea, fresh water is very scarce globally. The contaminants found in groundwater, rivers, lakes, and other sources must be removed, and potable water must be ensured for human consumption. Water can be purified simply by boiling, filtering, or other methods for home consumption1. In addition, Water purifiers, such as Reverse Osmosis, are used to remove salts from hard water2. An SS is equipment that uses the sun’s solar energy to purify the desalinated brackish water. This can be applied to various fields, including domestic, industrial, and other settings. It is more suitable for dry areas with ample sunshine3. The SS works through the vaporisation and condensation process to remove the impurities from the contaminated water. The vapour condenses on the cooler surface through sunlight and accumulates as purified water4.

Continuous research is being conducted to develop practical methods for enhancing the output of SS. A comparison of the results obtained with previous research is also being conducted to enhance understanding and productivity. These researchers focus on enhancing productivity, increasing energy and exergy effectiveness, and minimising the cost of production. Various research studies have also been conducted about the influence of different altitudes and climatic conditions during summer and winter and how they impact productivity. Hence, different SS types have been explored, like Single Slope SS (SSSS), Double Slope SS (DSSS), Inclined Still, Trapezodial SS, etc. and simple SS has been modified with the usage of wick fabrics, phase change substances, pin fined heat, steel wool fibres, glass cooling system, glass cover, air cooling system, etc. In general, it is observed that research on solar steam (SS) is being carried out more frequently in countries such as Egypt, India, and Iran, where the availability of solar energy is greater during the summer5.

Like every product, a SS has its pros and cons. The cost of constructing the SS is comparatively less, and the working of the still does not depend on power and fuel. SS is considered as the most effective method to purify sea water. More significantly, due to the immense volume of water contained in the ocean, it is practically limitless, making desalination an entirely drought-resistant water resource. This is also more suitable where the ground water is very hard and salty. It can be utilised by individuals and a small community where other purification sources are impossible. Water purification by this method is time-consuming, and water production is slow. Care should be taken when disposing of removed salts and other impurities, chemicals, etc., obtained from brackish water. Despite all this, SS is considered more environmentally friendly, harnessing sustainable energy sources that produce no detrimental by-products.

Sharshir et al.6 conducted research comparing the yield of Conventional Pyramid SS (CPSS) and Altered Pyramid SS (APSS). The APSS is categorised into APSS-A connected to six evacuated tubes and condenser, APSS-B same as APSS-A with 1 wt% CB nanoparticles, APSS-C equivalent to APSS-B attached to ultrasonic foggers in the basin. The research was conducted in Kafrelsheikh, Egypt, between 8:00 am and 7:00 pm in June and July 2021. The potable water yield by CPSS was 3.59 L, whereas APSS-A, APSS-B, and APSS-C yielded 6.86 L, 8.15 L, and 9.28 L, respectively, showing corresponding increases in production of 91.09%, 132.86%, and 162.15%. The augmented energy and exergy efficacies of the three APSS-A, B, C were found to be 18.48%, 45.26%, 28.22%, 75.43% and 34.26%, 81.51%, which, in contrast, resulted in the decreased cost of production to 2.78%, 15.15% and 32.04%, respectively. The analysis showed that APSS-C is the most recommended method, as it yielded a higher output at a lower cost than the traditional and other methods—the optimum price of production obtained from APSS-C was $0.14/L.

An experiment on the output of Conventional SS (CSS) with a different approach to connecting SSSS to the evaporation chamber, brackish water liner, and glass cover was conducted by Fang et al.7. In this process, lenses were fixed on the three walls, and a reflector on the rear surface of the evaporation chamber aimed to provide more evaporation in the SSSS. The research was conducted in Hangzhou, China, on July 24, 2017. It was observed that the SSSS yielded 2.5 L/m2, which was about 32% more than the yield of 1.9 L/m2 of SS, and the production rates of the two methods were almost equal at $0.043 and $0.042, respectively. This method reduced carbon dioxide emissions. Additionally, the energy and exergy efficiencies of CSS and SSSS were 13.05% and 6.60%, respectively, and 2.25% and 0.96%, indicating that SSSS provided an augmented percentage of 97.73% and 43.713%, respectively.

Yousef and Hassan8 have compared the productivity of various types of passive SSs such as CSS, SS with Phase Change Substance (SS-PCS), SS with PCS implanted in a pin fin heat sink (SS-PCS-PF), SS with PCS combined with Steel Wool Fibre in the basin (SS-PCS-SWF), SS with SWF only in the basin (SS-SWF) and SS with pin fined heat sink in the basin (SS-PF). The experiments used the same model of two passive SSSS assembled at New Borg El-Arab City in Egypt. The output of CSS, SS-PCS, SS-PCS-PF, SS-PCS-SWF, SS-SWF, SS-PF, were 3.26, 3.572, 3.81, 3.685, 4.08 and 3.78 kg/m2, respectively with an increased productivity of 10, 17, 13, 25, and 16% than the CSS. An increased output of 23% was attained in this study compared to 2.89 kg/m2 obtained in the previous research conducted. It was also noticed that the CSS output is very low compared to all other SSs. It was also observed that SS-SWF provided the maximum output of all different types of SSs. The energy and exergy efficiencies of CSS, SS-PCS, SS-PCS-PF and SS-PCS-SWF, SS-SWF, SS-PF, were 2.283, 2.5, 2.66, 2.58, 2.856 and 2.646 kWh and 0.1461, 0.1528, 0.1569, 0.1598, 0.1869 and 0.1683 kWh per with an escalation of 5%, 7%, 9%, 28%, and 15%, than the CSS.

The yield of CSS and CSS associated with Parabolic Trough Solar Collector (CSS-PTSC), CSS, wire mesh and PTSC (CSS-WM-PTSC), CSS with steel wire mesh in the basin (CSS-WM), Sand and PTSC (CSS-SD-PTSC) CSS added with sand in the basin (CSS-SD) and CSS, at various water levels were analysed by Hassan et al.9. The research was conducted between May 06–18, 2017 and July 02–15, 2017 during summer and winter, respectively, in Sohaig, Egypt. The yield produced during hot season by the CSS-PTSC, CSS-WM, CSS-WM-PTSC, CSS-SD, CSS-SD-PTSC were recorded as 3.96, 4.32, 4.67, 7.74, 8.15, and 8.77 kg/m2 which showed an increased productivity of 81.7%, 92%, 91.4%, 101%, 104.8%, and 102.1% in comparison to cold season. The CSS produced a low output of 3.96 kg/m2 and 2.18 kg/m2, whereas CSS-SD-PTSC provided a maximum output of 8.77 kg/m2 and 4.34 kg/m2 in hot and cold periods, respectively, at a minimum cost of production. The energy and exergy yield was 216.6% and 325% higher, respectively, in CSS-SD-PTSC than in CSS.

Sharshir et al.10 have carried out an analysis during July–August, 2021 at Kafrelsheikh (31.1030° N, 30.9397° E) about the working of Trapezoidal SS (TSS) having five number of slopes and adding a hanged wick structure to TSS namely ASS-1, ATSS-1 attached with a glass cooling system ATSS-2, ATSS-2 linked to a four flat reflectors. The per-day yield of TSS, ATSS-1, ATSS-2, and ATSS-3 were found to be 3.2, 11.1, 12.31 and 15.18 L/m2, with corresponding thermal efficacy of 33%, 45.8%, 52.5%, and 64.6% and exergy efficiency of 144%, 156.9% and 213.8%. A maximum output was obtained from ATSS-3 with a minimum cost of $0.0143/L, which was 368.5% more than the TSS. This was followed by enhanced yields of about 270.78% and 252.4% obtained from ATSS-2 and ATSS-1, respectively.

Research on the Cascade SS Desalination System with various insulation and PCS was conducted by Khanmohammadi and Khanmohammadi11. Matlab software was used to find out the productivity of thermal, economic, and environmental factors. It was revealed that the maximum output 9.24 kg/m2 per day could be attained when Cascade SS Desalination System with nePCS II and Phenolicfoam were used as PCS and insulation materials such as the glass wool, fiber glass, and cellular glass gave an output of 9.2, 9.0, and 8.9 kg/m2. The yearly thermal energy and exergy of the above insulation type materials are 827.91 kWh, 827.32 kWh, 827.62 kWh, 821.3 kWh, 49.84 kWh, 49.77 kWh, 49.81 kWh, and 49.407 kWh, respectively.

Yousef et al.12 carried out experiments on two consecutive days, 05.09.2017 and 06.09.2017, in Borg El-Arab City, Egypt, to find the yield CSS through the addition of hollow cylindrical pin copper fins and steel wool fibres inside the basin of the TSS. The copper fins were added to enhance thermal conductivity, and the SWF acted as a wick material to augment the surface area for evaporation. The potable water produced by CSS was 3.26 kg/m2, significantly less than the outputs of 3.78 kg/m2 and 4.08 kg/m2 provided by CSS with Copper Fins and CSS with SWF, respectively, thereby indicating an increase in production of 16% and 25%, respectively, over the CSS. The energy efficacies of these SSs were 42%, 45.5%, and 52.5%, respectively, indicating an increase of 13% and 25% by CSS with copper fins and SWF. The production rate of the above-mentioned stills is $0.0427, $0.0416, and $0.0343, respectively. The results revealed that the maximum yield was achieved with the CSS associated with SWF, at the minimum cost of production and CO2 emission, compared to the other two types of SS.

Pal et al.13 have constructed and fabricated altered basin type SSSS (ABSSSS), altered basin type DSSS (ABDSSS), altered basin type single slope multi-wick SS (ABSSMWSS) and altered basin type double slope multi-wick SS (ABDSMWSS) to study the impact of productivity on the modifications carried out in the SS. The research was conducted in the region of Prayagraj, India, based on its unique nature. It was observed that the yearly productivity of ABSSSS, ABDSSS, ABSSMWSS, and ABSSMWSS with jute wick and black cotton fabric and ABDSMWSS with jute wick and black cotton wick were found to be 861.55 kg, 1551.48 kg, 1172.03 kg, 1311.32 kg, 2324.74 kg and 2583.99 kg, respectively. It was also noted that the output and exergoeconomic values were maximum for ABDSMWSS with a black cotton wick and MBSSMWSS, respectively.

The output of four types of SSs in Alexandria, Egypt, during the summer season has been investigated by Abd Elbar et al.14. The CSS was converted to CSS-PV, CSS-PV-BSWF and CSS-PV reflector, with the addition of a photovoltaic (PV) module on the rear side of the SS, PV and black steel wool fibers in the basin, and PV as a reflector only, respectively. Since this process does not require extra space, this model is more suitable for cases with limited space. The outputs obtained from CSS, CSS-PV, CSS-PV-BSWF, and CSS-PV reflectors were 2.429, 2.6719, 3.187, and 2.52688 kg/m2, with enhanced productivities of 10%, 31.48%, and 3.04% compared to CSS, respectively. Compared to other types of SS, the results showed that CSS with a PV reflector is the best method for producing potable water. The energy and energy efficiencies were also increased by 10%, 31.48%, 43.16%, 30.72%, 49.14%, and 680.7%, respectively.

Lovedeep15 examined the workings of passive DSSS and DSSS amalgamated with aluminium oxide (Al2O3), titanium oxide (TiO2), and copper oxide (CuO)—water-based nanofluids. Much research is being carried out on nanofluids since it is considered an advanced technology process. The study was conducted in Delhi, considering the variations that arise due to the change in the weather every month. The output, thermal energy and exergy of the DSSS, DSSS added with Al2O3, TiO2 and CuO-water based nanofluids were 1241.89 kg, 1101.64 kWh, 82.29 kWh; 1483.65 kg, 1396.51 kWh, 113.25 kWh; 1370.86 kg, 1314.93 kWh, 103.32 kWh; 1307.21 kg, 1244.43 kWh, 92.164 kWh, respectively. The results showed an escalated output of 19.10%, 10.38% and 5.25% and energy and exergy increase of 26.75%, 37.77%; 19.36%, 25.55%; and 12.96%, 11.99% obtained from Al2O3, TiO2 and CuO-water based nanofluids.

The influence of utilising an air-cooled SS (ACSS) and a water-cooled SS (WCSS) on 02.12.2019 in Tehran, Iran, was studied by Shoeibi16. The water temperature was enhanced by connecting the heat surfaces of the thermoelectric part and water tank. The water from the WCSS was pumped to the hot water tank. The yearly output of ACSS, WCSS and amalgamation of WCSS to CFD at a temperature of 290 K, glass thickness of 0.001 m, and velocity of 3 m/s was recorded. It was noted that the yearly output of WCSS-CFD was a maximum of 468.4 L with the minimum production cost rate of $0.201/L, whereas the ACSS and WCSS showed an output of 212.8 L and 385.5 L, respectively. The study revealed that the temperature and velocity directly impact the production of the WCSS.

Parsa et al.17 have compared the yield of Active SS (ASS) and CSS at highland surfaces of Tochal and Tehran which were about 3964 m and 1171 m above the sea level during the period from July 24–30, 2018. Two SS of same type were chosen for this study in which ASS were attached with thermoelectric module and PV panel. The yearly productivity of ASS and PSS at Tochal and Tehran were 2122.8 L, 2971.8 L, 717.36 Land 916.15 L which showed an enhanced output was obtained at Tehran than Tochal of about 39.96% and 27.7% respectively. The cost of production of water was found maximum of $0.0079/L in PSS at Tehran and minimum of $ 0.0372/L in ASS at Tochal. The energy efficiency was maximum and minimum at PSS in Tehran, and it was also found that the energy parameters showed higher values in Tehran than in Tochal during the research period.

The yield of CSS of the same parameters with one CSS connected with a PCM storage tank (SSSS-PCM) was investigated by Yousef and Hassan18. The potable water yield from CSS and CSS-PCM during summer and winter were 3.26, 2.126, 3.572, and 2.2 kg/m2, respectively. The corresponding energy and exergy efficacies of CSS-PCS were increased by 10% and 3%, respectively. The yield of CSS-PCS was higher than that of CSS in both summer and winter. It was also observed that the output of both the SSs was higher in the hot period than in the cool climatic conditions. Adding PCM to CSS helps produce more water to a greater extent than CSS.

Sahota and Tiwari19 have conducted research on DSSS connected with an ‘N’ number of PV Thermal Flat Plate Collectors (DSSS-N-PV/T-FPC). The DSSS-N-PVT-FPC was further classified into three dimensions as with no heat exchanger, with coiled heat exchanger and passive DSSS which were termed as DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-A, DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-B and DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-C respectively. The analysis was carried out in Delhi, and the research was conducted by amalgamating DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-A, B, and C with Al2O3, TiO2 and CuO-water based nanofluids. The results showed the productivity, energy and exergy of DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-A with Water, Al2O3, TiO2 and CuO-water were recorded as 3663.23 kg, 3825.31 kg, 3743.93 kg, 3961.24 kg; 2391.22 kWh, 2673.7 kWh, 2526.99 kWh, 2785.78 kWh and 412.77 kWh, 537.14 kWh, 506.13 kWh, 592.07 kWh, respectively. Similarly DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-B with Water, Al2O3, TiO2 and CuO-water were found to be 2735.01 kg, 3084.26 kg, 2863.33 kg, 3250.99 kg; 1711.11 kWh, 2058.08 kWh,1866.45 kWh, 2291.79 kWh; 287.65 kWh, 388.93 kWh, 355.06 kWh, 439.79 kWh and with DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-C were 1241.89 kg, 1483.65 kg, 1370.86 kg, 1307.21 kg; 1101.64 kWh, 1396.51 kWh, 1314.93 kWh, 1244.43 kWh; 82.29 kWh, 113.25 kWh, 103.32 kWh, 92.164 kWh respectively. From the above results, it is clear that the output yield from water is lower than that of DSSS-N-PVT-FPC-A and B; this may be due to the influence of nano fluids.

Tiwari et al.20 investigated the integration of a PV/T-FPC with Active SSSS. The experiment was conducted in IIT, Delhi, between August 2013 and July 2014. The results acquired were examined and compared with the research work of other scholars. The study revealed that the thermal efficacy of the present model was 16.67%, which was comparatively lower than the previous two research proposals considered, yielding 23.2% and 13.4%. Also, it was observed that daily and daily overall thermal, exergy, electrical efficacy of the present model and other two previous research study results provided 5.04%, 4.59%, 7.45%; 18%, 13.8%, 5.3%; 10.6%, 10.14%, 3.6% and 18%, 13.8%, 5.3% respectively showed an escalated results. Meanwhile, the overall thermal efficiency of the above three proposals was recorded at 53.4%, 53.1%, and 28.5%, which exceeded the percentages reported in previous studies.

Singh et al.21 did an investigation with DSSS connected with “N’ number of similar evacuated tubular collectors (DSSS-N-ETC) with previous research experiments with ‘N” similar, DSSS with PV/T FPC (DSSS-N-PVT-FPCs) Compound parabolic Concentrator Collectors (DSSS-N-CPCs) and traditional DSSSS. The DSSS is fabricated with a glass-reinforced polemic and features a 2 m² basin area, with the water level maintained at 0.14 m. The study focused on clear sky, partly cloudy day, partly cloudy, and cloudy days in the region of Delhi. MATLAB computations were also used to get the results. The yearly productivity of the experiment was found to be a maximum of 6099.85 kg, more than the previous research outputs of 5959.83 kg, 4757.70 kg and 1555.79 kg, respectively. Also, the output was at its maximum during May because of the peak summer climate. DSSS-PVT-FPCs was considered better than DSSS-N-ETC and DSSS-CPCs in terms of enviro-economic factors. The present study has provided high productivity at a low production rate, i.e. Rs. 0.47 per kg compared to previous experimented results.

Singh and Tiwari22 have undergone research on active SSSS and DSSS, each integrated with ‘N’ number of PV/T and Compound Parabolic Concentrator Collectors PVT-CPC, which may be termed as SSSS-N-PVT-CPC and DSSS-N-PVT-CPC. The study aimed to determine the results of productivity, energy, exergy, and cost factors for the SSSS-N-PVT-CPC and DSSS-N-PVT-CPC, which were carried out in Delhi. The water level was maintained at 0.14 m, and the numerical details, including temperature and solar radiation, were provided by the Meteorological Department of India, Pune. MATLAB software was used for computation. It was observed that DSSS-N-PVT-CPC has given a better yield of about 8% more than SSSS-N-PVT-CPC, and also, the exergo and energy efficiency of DSSS-N-PVT-CPC was of 15.64% and 7.67% greater than SSSS-N-PVT-CPC.

The productivity of a Parabolic Dish Concentrator Box SS attached to a thermoelectric cooling channel was investigated by Nazari and Daghigh23. The heat radiation, temperature, and airflow were considered. The experiment was conducted in different approaches such as Case-A, Case-B, Case-C, Case-D connected with natural way of sucking the vapour in the channel without fan, sucking of vapour with fan at different rates such as 100, 200, 300 L/min respectively. The speed of the fan showed a significant change in the results obtained. The study was conducted in Kermanshah, Iran, from November 9, 2020, to November 18, 2020. The productivity, energy, and exergy efficiency were enhanced by increasing the flow of water vapour through the thermoelectric cooling channel. It was observed that the yearly productivity in this study reached a maximum of 5628 L/m², obtained by Case-D, followed by 5379 L/m², 5001.5 L/m², and 4483 L/m² for Case-C, Case-B, and Case-A, respectively. Similarly, the energy and exergy efficiencies obtained were in the order of 575 kWh, 110.11 kWh; 550 kWh, 105.8 kWh; 511 kWh, 98.16 kWh; 458 kWh, 87.73 kWh, for Cases D, C, B, and A, respectively. The cost of production was found to be optimal at Cae-D, at $0.056 L/m2.

Recently, numerous researchers have explored methods to enhance the performance of SSs using various materials. These include waste and low-cost materials24,25, nanomaterials26,27, wick materials28 and hybrid configurations29,30. Various materials have been explored to increase the daily water yield of SSs, including: Jute31, Paraffin wax32,33, Nanoparaffin34, Metal matrix structures35, Sand and black wool fibers36, Kanchey Marble37, Pumice stone38, Magnetic field39, Quartzite40, Gravel41,42, Crushed gravel sand43. These materials have great potential to improve the efficiency of SSs, helping to increase water production and thermal performance. These research works motivated us to study the effect of SiC in SSs. The enhanced thermophysical properties of SiC material may improve the conventional SS performance.

Experimental setup

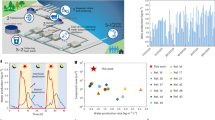

Two CSSs were manufactured using 2 mm thick mild steel sheet. Figure 1 shows the schematic view of the CSS with and without SiC. Subsequently, a 4 mm thick transparent commercial glass was positioned at a 32° angle over the still. SiC was placed at the bottom and covered with a cloth in one of the CSSs. In the period from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM, the measurements were made. Data on yield, solar intensity, air temperature, water temperature (Tw), and glass temperature (Tg) were collected every hour from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM to analyse the thermal behaviour of both stills. During the test days, the conventional and SS-containing SiC water level stayed 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM. Figure 2 displays a photograph of the CSS and the CSS with SiC. Table 1 gives properties of SiC.

Schematic view of the CSS with and without SiC (MS power point 2019, https://answers.microsoft.com/en-us/msoffice/forum/all/microsoft-office-2019-download-link/acf676f5-95d3-4487-8858-52758b1b9ef8).

Result and discussion

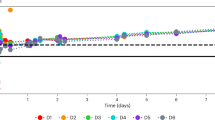

Solar radiation was measured every 1 h between 8 h and 19 h for 3 days. The variation in solar radiation intensity corresponding to local time is shown in Fig. 3. The solar radiation intensity attained a maximum value of about 1000 W/m2 during 12 h, irrespective of the day. The solar radiation intensity increased steadily from 8 h to 12 h and then steadily fell from 12 to 19 h.

The cumulative yield obtained for each hour between 8 and 19 h on the day with maximum solar radiation is displayed in Fig. 4. For both CSS and CSS SiC systems with varying water seawater depths, the cumulative yield change over time is plotted. The cumulative yield for CSS SiC with a seawater depth of 2 cm is approximately 720 mL, while the yield for CSS with a seawater depth of 1 cm is around 490 mL. The yield on CSS was significantly increased with increasing seawater depth. Conversely, for every 1 cm increase in seawater depth, the cumulative yield in CSS SiC increased; however, for every 3 cm of seawater depth, the yield drastically decreased. Including SiC particulates, which have a high heat storage capacity, may cause a noticeable increase in CSS SiC’s heat storage capacity. This phenomenon consequently decreased the yield by altering the rate at which water in the still evaporated and condensed.

Figure 5 displays the cumulative yield for various SSs. The maximum cumulative yield for CSS SiC at a seawater depth of 2 cm is approximately 2880 mL/m2 per day. When the seawater depth was increased from 1 to 3 cm, the cumulative yield for CSS increased significantly; however, the CSS SiC system exhibited a rise-and-fall trend. At a seawater depth of 2 cm, CSS SiC yields the maximum cumulative yield of approximately 2880 mL/m2 per day. This is nearly 25% higher than the CSS yield at the same seawater depth. The addition of SiC still significantly increased the cumulative yield, thereby improving both heat storage and evaporation capacity.

The hourly water temperature readings for the CSS and CSS SiC systems at different seawater depths are displayed in Fig. 6. The maximum water temperature was reached after 12 h, regardless of the seawater depth in any system. This is because 12 h is when the sun’s radiation intensity peaks. For every system, the temperature curves rose at sunrise, peaked at 12 h, then began to decline and reached a minimum at 19 h for all seawater depths. The most significant temperature of water that CSS could achieve was 71 °C at a seawater depth of 1 cm, and in CSS SiC, the temperature was 70 °C at the same seawater depth. The maximum water temperature decreases slightly in both systems with increasing seawater depth. This could be explained by the fact that higher rates of condensation and evaporation resulted from more water, which led to a slight cooling of the basin water.

Figure 7 shows the temperature variation of the glass cover over time. The temperature variation trend for glass covers is comparable to water temperatures. It rose in the early morning and fell in the late afternoon. For all seawater depths in both SSs, the peak occurred at 12 h. The system’s maximum glass cover temperature rose as the seawater depth increased. The peak temperature for the glass cover was 55 °C for CSS and 56 °C for CSS SiC at a seawater depth of 3 cm and 2 cm, respectively. At 12 h, the temperature difference between the glass cover and the water is between 12 and 15 °C. Due to heat loss and increased evaporation rate, increased seawater depth transferred heat from the saline water to the glass cover.

Figure 8 displays the hourly change of the evaporative heat transfer coefficient. At 12 h, the evaporative heat transfer coefficient reached its peak. For a seawater depth of 1 cm in CSS and CSS SiC, the maximum evaporative heat transfer coefficients were 50 W/m2 K and 52 W/m2 K, respectively. The reduction of the evaporative heat transfer coefficient was observed with increased seawater depth. When the seawater depth is increased from 1 to 3 cm, the evaporative heat transfer coefficient in both the CSS and CSS SiC systems decreases by nearly 28%.

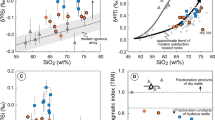

Figure 9 illustrates how energy efficiency and exergy efficiency change with seawater depth. An increase in seawater depth significantly decreased the energy and energy efficiency of the CSS and CSS SiC systems. In CSS, energy efficiency dropped from 35.67 to 24.3% for water depths between 1 and 3 cm, and similarly, for seawater depths between 1 and 3 cm, energy efficiency dropped from 2.98 to 1.8%. A comparable trend of variation was also noted in the CSS SiC case. The temperature of the saline water and basin directly relates to the SS’s energy and energy efficiency. For both systems, these temperatures peak at 12 h at a water seawater depth of 1 cm, and the efficiencies also showed this. Higher temperatures demonstrated that the maximum amount of solar intensity was absorbed.

An indication of energy losses occurring in any of the SS’s components is energy destruction. Figure 10 shows the energy destruction of the basin, saline water, and glass cover for different seawater depths in both SSs. For both SSs, the rate of energy destruction of the glass cover and basin decreases as seawater depth increases; however, the trend is the opposite for saline water. When compared to a glass cover and salted water, the basin experiences the greatest energy destruction. The glass cover, basin, and saline water in CSS have been found to have the highest estimated energy destruction values of 598, 4231, and 1640 W/m2, respectively, at seawater depths of 1 cm, 1 cm, and 3 cm. For the glass cover, basin, and saline water in CSS SiC, the highest exergy destruction has been estimated to be 724, 4459, and 1546 W/m2, respectively, for seawater depths of 1 cm, 1 cm, and 3 cm. An increase in seawater depth lowers energy loss by increasing evaporation rates and heat storage capacity. However, because of the material’s higher thermal conductivity and greater capacity for heat storage, there are also more heat losses in the basin.

Table 2 provides specifics regarding the yield obtained in earlier studies. From the table, the DSSS-N-PVT-FPCs have given an escalated output of 6099.85 kg/year with a low cost of production when compared with the previous year’s research analysis (Singh et al. 2019), which is recorded as the highest yield in India. A study (Saeed Nazari and Roonak Daghigh 2022) conducted in Iran on the influence of the speed of air on a parabolic Dish concentrator Box SS attached to a thermoelectric cooling channel in different modes showed the highest productivity of 5628 L/m2. The impact of seal level was investigated (Seyed Masoud Parsa et al. 2020) at different altitudes of Tochal (3964 m) and Tehran (1171 m) using ASS and PSS which revealed that both the stills showed an enhanced output in Tehran. The results also indicated that the production of CSS is always lesser than the SS attached, altered/integrated with other components/usage of wick and PCM, etc. In this study, an SS with SiC at 1 cm produces a maximum of 5.64 kg daily.

Water quality measurement

The water sample for the experiments was tested before and after the testing periods and compared to the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). The TDS and pH are within the BIS water quality standards. The Table 3 below indicates the water quality analysis for CSS with and without Sic.

Conclusion

This study presents the exergy analysis and exergy destruction of a SS at 1, 2, and 3 cm seawater depth with and without SiC. The study’s primary conclusions are listed below.

-

The daily yield of an SS at 1, 2, and 3 cm seawater depth with and without SiC was 5.64, 5.1, and 3.06 kg, 4.68, 3.9, and 3.2 kg, respectively.

-

At 1, 2, and 3 cm seawater depth, the thermal efficiencies of the SS containing SiC are 44.2, 39.9, and 23.8%, while those of the SS without SiC are 35.67, 29.69, and 24.3%, respectively.

-

Exergy efficiency values for SS containing SiC at 1, 2, and 3 cm seawater depth are 3.99, 3.41, and 1.76%, respectively, while those of the SS without SiC at 1, 2, and 3 cm seawater depth are 2.98, 2.35, and 1.8%, respectively.

-

At water depths of 1 cm, 1 cm, and 3 cm, the glass cover, basin, and saline water in CSS and CSS with SiC were determined to have the most excellent estimated energy destruction values, at 598, 4231, and 1640 W/m2, and 724, 4459, and 1546 W/m2, respectively.

Future scope

Nano-sized SiC can be used as sensible heat storage materials.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Muthu Manokar Athikesavan.

Abbreviations

- SS:

-

Solar still

- CSS:

-

Conventional SS

- CPSS:

-

Conventional pyramid SS

- SWF:

-

Steel wool fibers

- APSS:

-

Altered pyramid SS

- SSSS:

-

Single Slope SS

- SS-PCS:

-

SS with phase change substance

- SS-PCS-PF:

-

SS with PCS embedded in a pin fin heat sink

- SS-PCS-SWF:

-

SS with PCS incorporated with steel wool fibers in the basin

- SS-SWF:

-

SS with SWF only in the basin

- SS-PF:

-

SS with pin fined heat sink in the basin

- CSS-PTSC:

-

CSS associated with parabolic trough solar collector

- CSS-WM:

-

CSS with steel wire mesh in the basin

- CSS-WM-PTSC:

-

CSS, wire mesh and PTSC

- CSS-SD:

-

CSS added with sand in the basin

- CSS-SD-PTSC:

-

CC, Sand and PTSC

- TSS:

-

Trapezoidal SS

- ATSS-1:

-

Altered TSS with hanged wick structure

- ATSS-2:

-

Altered TSS with a glass cooling system

- ATSS-3:

-

Altered TSS with four flat reflectors

- ABSSSS:

-

Altered basin type single slope SS

- ABSSMWSS:

-

Altered basin type double slope SS

- ABDSSS:

-

Altered basin type single slope multi-wick SSl

- ABDSMWSS:

-

Altered basin type double slope multi-wick SSl

- CSS-PV:

-

CSS with photovoltaic module

- CSS-PV-BSWF:

-

CSS with PV and black steel wool fibers

- CSS-PV reflector:

-

CSS with PV used as a reflector only

- DSSS:

-

Double slope SS

- ACSS:

-

Air cooled SS

- WCSS:

-

Water cooled SS

- WCSS-CFD:

-

WCSS-computational fluid dynamic

- ASS:

-

Active SS

- SSSS-PCS:

-

SSSS-PCS storage tank

- PSS:

-

Passive SS

- PVT:

-

Photovoltaic thermal

- FPC:

-

Flat plate collector

- PVT-FPC-A:

-

PVT-FPC with no heat exchanger

- PVT-FPC-B:

-

PVT-FPC with coiled heat exchanger

- PVT-FPC-C:

-

PVT-FPC-PSS

- DSSS-N-ETC:

-

DSSS-evacuated tubular collectors

- DSSS-N-PVT-FPCs:

-

DSSS-PVT flat plate collectors

- DSSS-N-CPCs:

-

DSSS-compound parabolic concentrator collectors

- N:

-

Number (Nth)

- PVT-CPC:

-

PVT compound parabolic concentrator collectors

References

Lal, S. & Batabyal, S. K. Potato-based microporous carbon cake: solar radiation induced water treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (5), 108502 (2022).

Lal, S. & Batabyal, S. K. Activated carbon-cement composite coated polyurethane foam as a cost-efficient solar steam generator. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134302 (2022).

Lal, S., Sundhar, K. & Batabyal, S. K. Solar driven interfacial evaporator using waste tissue papers charred with sulfuric acid for water production. Sol. Energy. 270, 112374 (2024).

Lal, S., Gowthaman, T., Ghosh, S. & Batabyal, S. K. Integrating atmospheric water harvester with hydrovoltaics: simultaneous freshwater production and power generation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 357, 130086 (2025).

Taamneh, Y. et al. Extraction of drinking water from modified inclined solar still incorporated with spiral tube solar water heater. J. Water Process. Eng. 38, 101613 (2020).

Sharshir, S. W. et al. 4-E analysis of pyramid solar still augmented with external condenser, evacuated tubes, nanofluid and ultrasonic foggers: a comprehensive study. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 164, 408–417 (2022).

Fang, S., Mu, L. & Tu, W. Application design and assessment of a novel small-decentralized solar distillation device based on energy, exergy, exergoeconomic, and enviroeconomic parameters. Renew. Energy. 164, 1350–1363 (2021).

Yousef, M. S. & Hassan, H. Assessment of different passive solar stills via exergoeconomic, exergoenvironmental, and exergoenviroeconomic approaches: a comparative study. Sol. Energy. 182, 316–331 (2019).

Hassan, H., Yousef, M. S., Fathy, M. & Ahmed, M. S. Assessment of parabolic trough solar collector assisted solar still at various saline water mediums via energy, exergy, exergoeconomic, and enviroeconomic approaches. Renew. Energy. 155, 604–616 (2020).

Sharshir, S. W. et al. Comprehensive thermo-enviroeconomic performance analysis of a preheating-assisted trapezoidal solar still provided with various additives. Desalination 548, 116280 (2023).

Khanmohammadi, S. & Khanmohammadi, S. Energy, exergy and exergo-environment analyses, and tri-objective optimization of a solar still desalination with different insulations. Energy 187, 115988 (2019).

Yousef, M. S., Hassan, H. & Sekiguchi, H. Energy, exergy, economic and enviroeconomic (4E) analyses of solar distillation system using different absorbing materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 150, 30–41 (2019).

Pal, P. et al. Energy, exergy, energy matrices, exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic assessment of modified solar stills. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101514 (2021).

Abd Elbar, A. R., Yousef, M. S. & Hassan, H. Energy, exergy, exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic (4E) evaluation of a new integration of solar still with photovoltaic panel. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 665–680 (2019).

Lovedeep, S. & Tiwari, G. N. Energy matrices, enviroeconomic and exergoeconomic analysis of passive double slope solar still with water based nanofluids. Desalination 409, 66–79 (2017).

Shoeibi, S., Rahbar, N., Esfahlani, A. A. & Kargarsharifabad, H. Energy matrices, exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic analysis of air-cooled and water-cooled solar still: experimental investigation and numerical simulation. Renew. Energy. 171, 227–244 (2021).

Parsa, S. M. et al. Energy-matrices, exergy, economic, environmental, exergoeconomic, enviroeconomic, and heat transfer (6E/HT) analysis of two passive/active solar still water desalination nearly 4000m: altitude concept. J. Clean. Prod. 261, 121243 (2020).

Yousef, M. S. & Hassan, H. Energy payback time, exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic analyses of using thermal energy storage system with a solar desalination system: an experimental study. J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122082 (2020).

Sahota, L. & Tiwari, G. N. Exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic analyses of hybrid double slope solar still loaded with nanofluids. Energy Convers. Manag. 148, 413–430 (2017).

Tiwari, G. N., Yadav, J. K., Singh, D. B., Al-Helal, I. M. & Abdel-Ghany, A. M. Exergoeconomic and enviroeconomic analyses of partially covered photovoltaic flat plate collector active solar distillation system. Desalination 367, 186–196 (2015).

Singh, D. B. Exergo-economic, enviro-economic and productivity analyses of N identical evacuated tubular collectors integrated double slope solar still. Appl. Therm. Eng. 148, 96–104 (2019).

Singh, D. B. & Tiwari, G. N. Exergoeconomic, enviroeconomic and productivity analyses of basin type solar stills by incorporating N identical PVT compound parabolic concentrator collectors: a comparative study. Energy Convers. Manag. 135, 129–147 (2017).

Nazari, S. & Daghigh, R. Techno-enviro-exergo-economic and water hygiene assessment of non-cover box solar still employing parabolic dish concentrator and thermoelectric peltier effect. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 162, 566–582 (2022).

Attia, M. E. H. et al. Phosphate bed as energy storage materials for augmentation of conventional solar still productivity. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy 40(4), e13581. (2021).

Prasad, A. R. et al. Energy and exergy efficiency analysis of solar still incorporated with copper plate and phosphate pellets as energy storage material. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28 (35), 48628–48636 (2021).

Balachandran, G. B. et al. Investigation of performance enhancement of solar still incorporated with Gallus gallus domesticus Cascara as sensible heat storage material. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28 (1), 611–624 (2021).

Benoudina, B. et al. Enhancing the solar still output using micro/nano-particles of aluminum oxide at different concentrations: an experimental study, energy, exergy and economic analysis. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 29, e00291. (2021).

Essa, F. A., Omara, Z. M., Abdullah, A. S., Kabeel, A. E. & Abdelaziz, G. B. Enhancing the solar still performance via rotating Wick belt and quantum Dots nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 27, 101222 (2021).

Manokar, A. M. et al. Enhancement of potable water production from an inclined photovoltaic panel absorber solar still by integrating with flat-plate collector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22 (5), 4145–4167 (2020).

Thalib, M. M. et al. Energy, exergy and economic investigation of passive and active inclined solar still: experimental study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 145 (3), 1091–1102 (2021).

Sakthivel, M., Shanmugasundaram, S. & Alwarsamy, T. An experimental study on a regenerative solar still with energy storage medium—Jute cloth. Desalination 264 (1–2), 24–31 (2010).

Ansari, O., Asbik, M., Bah, A., Arbaoui, A. & Khmou, A. Desalination of the brackish water using a passive solar still with a heat energy storage system. Desalination 324, 10–20 (2013).

Hafs, H. et al. Numerical simulation of the performance of passive and active solar still with corrugated absorber surface as heat storage medium for sustainable solar desalination technology. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 14, 100610 (2021).

Elfasakhany, A. Performance assessment and productivity of a simple-type solar still integrated with nanocomposite energy storage system. Appl. Energy. 183, 399–407 (2016).

Sathish, D., Veeramanikandan, M. & Tamilselvan, R. Design and fabrication of single slope solar still using metal matrix structure as energy storage. Mater. Today Proc. 27, 1–5. (2020).

Hassan, H. & Abo-Elfadl, S. Investigation experimentally the impact of condensation rate on solar still performance at different thermal energy storages. J. Energy Storage. 34, 102014 (2021).

Saravanan, N. M., Rajakumar, S. & Moshi, A. A. M. Experimental investigation on the performance enhancement of single basin double slope solar still using kanchey marbles as sensible heat storage materials. Mater. Today Proc. 39, 1600–1604. (2021).

Bilal, A., Jamil, B., Haque, N. U. & Ansari, M. A. Investigating the effect of pumice stones sensible heat storage on the performance of a solar still. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 9, 100228 (2019).

Rufuss, D. D. W. et al. Combined effects of composite thermal energy storage and magnetic field to enhance productivity in solar desalination. Renew. Energy. 181, 219–234 (2022).

Nagaraj, S. K., Nagarajan, B. M. & Ponnusamy, P. Performance analysis of solar still with Quartzite rock as a sensible storage medium. Mater. Today Proc. 37, 2214–2218. (2021).

Sakthivel, M. & Shanmugasundaram, S. Effect of energy storage medium (black granite gravel) on the performance of a solar still. Int. J. Energy Res. 32 (1), 68–82 (2008).

Dhivagar, R., Mohanraj, M. & Belyayev, Y. Performance analysis of crushed gravel sand heat storage and biomass evaporator-assisted single slope solar still. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28 (46), 65610–65620 (2021).

Elashmawy, M. Improving the performance of a parabolic concentrator solar tracking-tubular solar still (PCST-TSS) using gravel as a sensible heat storage material. Desalination 473, 114182 (2020).

Acknowledgements

https://submission.springernature.com/submission/bd90888c-cb1a-49bb-8cc1-d8006cef2150/review.

Funding

There is no funding received for the research work carried out.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Emmanuel Agbo Tei - Writing original manuscript, review & editing Sivakumar V - Writing original manuscript, review & editingRasool Mohideen - review & editingMuthu Manokar Athikesavan– Software, review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tei, E.A., Sivakumar, V., Mohideen, R. et al. An experimental study examined how seawater depth affects the perormance of solar stills with and without silicon carbide. Sci Rep 15, 19242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02915-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02915-x