Abstract

Jeffbenite is a magnesium aluminosilicate phase (nominally Mg3Al2Si3O12) found naturally in close association with diamonds. It has been synthesized at pressures as low as 6.5 GPa. We report here the synthesis of crystalline jeffbenite solid solutions at ambient pressure, through the controlled crystallization of glass. The resulting glass-ceramic materials can have between 20 and over 60 wt% crystalline jeffbenite. X-ray diffraction, 27Al NMR, Raman spectral analysis, density, and elastic property evaluation all support the identification of this phase precipitating from glass. A mechanism for the nucleation and formation of this high-pressure phase, at ambient pressure conditions, is presented. Glass-ceramics based on jeffbenite may be transparent or opaque, have high modulus and hardness, and can be strengthened by ion exchange for a possible range of technical uses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Jeffbenite is high-pressure phase that occurs naturally in close association with diamond, often as an inclusion, and has been used as a geological marker for determining depth and pressure of formation1,2,3,4,5,6. It is a dense tetragonal phase of space-group: I-42d (#122)2. The nominal formula of jeffbenite is identical to the Mg-garnet pyrope, namely Mg3Al2Si3O12, with the formula per unit cell being four times that: Mg12Al8Si12O48. In terms of lattice sites, in decreasing size, the structure can be represented as M14VIII M38V IM28VI T14IV T28Iv O48. For an Mg-Fe jeffbenite, the M1 site, a capped tetrahedral site or distorted octahedral site, is largest at 21.42 Å3. The M3 site is 11.66 Å3; M2 is 10.86 Å3. The T2 at 2.219 Å3 and T1 sites at 2.174Å3 are the smallest. The M1 and M3 sites are predominantly occupied by Mg and Fe, (some Al substitution in M3 is accepted), where M2 is largely Al-occupied. The T1 and T2 sites are taken largely by Si, however T2 can be a site for Al3+. In terms of average cation to oxygen distance, M1 is about 2.36 Å, M3 is 2.08 Å , M2 is 2.02 Å, T2 is 1.65 Å and T1 is 1.6 3Å2,5. Several naturally occurring jeffbenites have been described in the literature, having TiO2, Cr2O3, FeO, Fe2O3, CaO, and MnO substitutions. Small amounts of Na2O can also be present as well6. From atomic radii considerations, it would seem that Zr4+, Ti4+, Zn2+, Ca+ 2, Mg2+ and perhaps Na1+ could enter the distorted tetrahedral M1 site. The M3 site could potentially accept Zn2+. These considerations will become important as our work is discussed.

Several varieties of jeffbenite have been synthesized using high pressure conditions (6–15 GPa) in the laboratory, namely iron-rich and titania-rich varieties3,7,8,9. In contrast to early reports concerning the depth and pressure of formation of natural jeffbenite, ab initio calculations suggest that stoichiometric jeffbenite would be stable at relatively low temperatures, and pressures as low as 2.4 GPa6. This is supported by the larger molar volume of jeffbenite compared to the Mg-garnet pyrope referenced above; the molar volume argument would suggest a lower pressure formation of jeffbenite compared to pyrope but indeed in the GPa range.

We have been able to synthesize jeffbenite crystalline phases in a glass-ceramic as the result of the controlled crystallization of MgO*Al2O3*SiO2*ZrO2 precursor glasses, using prescribed heat treatments of the glasses. Significantly, the crystallization of the jeffbenite phase takes place at ambient pressure. These glasses contain major amounts of SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, Na2O and ZrO2. In the precursor glass compositions, TiO2 can partially replace some of the ZrO2, ZnO may replace some of the MgO, and K2O may replace Na2O, either partially or completely. We observed that the presence of ZrO2 in the glasses is necessary for the precipitation of the jeffbenite phase. After the heat treatment of the amorphous glass that leads to crystallization of the desired phase, the alkaline oxides are believed to form an aluminosilicate residual glass phase that metastably co-exists with the jeffbenite. The resulting multiphase glass-ceramic material can be between 15 and 75 wt% jeffbenite, with the balance comprised of residual glass and fine grained ZrO2, depending on the initial glass composition. The presence of the residual glass is important for ion-exchange strengthening, typically K+ for Na+, carried out in a KNO3 bath.

Methods

In this section the glass melting, heat treatment procedures, and characterization methods are described.

Glass melting and heat treatments

The glasses were melted from oxide and carbonate batch materials in platinum crucibles at 1600–1650°C, typically for 16 h. Patties of glass, about 1 kg, were then poured into steel molds and then placed in at annealing oven between 600 and 750°C. Pieces were cut from the glass and reheated in a laboratory furnace between 750–900°C, to form a glass-ceramic. There are normally two holding periods at different temperatures within this range: a lower nucleation hold followed by a higher crystallization hold. These holds are normally between ½ and 6 h. Exact durations and temperatures for the schedules are shown in Table 1, with the precursor glass composition. In all cases the glass samples were loaded into a cold furnace and ramped to the nucleation and crystallization temperatures at 5° C/minute. After the crystallization hold, the furnace was turned off and the samples were left to cool in the furnace; no prescribed cooling schedule was employed.

Characterization of the materials

The glass-ceramics were studied by both X-ray diffraction (XRD) and high temperature XRD (HTXRD) to identify the phases, the weight% of each phase, and the crystal size, the latter two by Rietveld analysis. Powder XRD was completed by Cu radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) on a Bruker D8 Endeavor diffractometer equipped with a Lynxeye detector. Samples were ground into fine powders using a ring mill and backloaded into standard powder diffraction holders. Diffraction scans were collected from 5 to 80 degrees two theta with a 0.5-degree fixed divergence slit. Phase ID was completed using MDI JADE Pro 9.0 (https://www.icdd.com/mdi-jade/) combined with PDF-5 + 2024 (https://www.icdd.com/pdf-5/). Rietveld analysis was completed using Topas Version 6 (https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/diffractometers-and-x-ray-microscopes/x-ray-diffractometers/diffrac-suite-software/diffrac-topas.html). Repeatability of the quantification was +/- 1.2%. HTXRD was completed by Cu radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) in an air atmosphere on a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean diffraction system equipped with an Anton Paar HTK1200N furnace and a PIXcel detector. Polished sample discs were prepared to fit into Al2O3 sample holders. Heating rates were 10 °C/min up to data collection temperatures, then samples were held isothermally during data collection period of 15 min. Data was evaluated utilizing MDI JADE combined with PDF-5 + and Topas software.

Young’s modulus, shear modulus and Poisson’s ratio were measured on the precursor glass and glass-ceramics via resonant ultrasound spectroscopy (RUS) according to ASTM E2001-13 (Standard Guide for Resonant Ultrasound Spectroscopy for Defect Detection in Both Metallic and Non-metallic Parts) on 10 × 8 × 6 mm samples with ground surfaces.

Fracture toughness was evaluated using the chevron-notched short bar method in accordance with ASTM E1304–97(2014): Standard Test Method for Plane-Strain (Chevron-Notch) Fracture Toughness of Metallic Materials.

Density was measured using Archimedes method in accordance with ASTM C693: Standard Test Method for Density of Glass by Buoyancy.

Vickers hardness was measured on precursor glass and glass-ceramic. Vickers indents were made using a Mitutoyo HM220 microhardness tester with a 200 g load, at a load rate of 20 g/s, and a dwell time of 15 s. Indentation diagonals were measured on a Nikon Optifot-2 microscope at 500X. Vickers hardness was calculated by \(\:{H}_{v}=\frac{1854.4*F}{{L}^{2}}\), where Hv is Vickers hardness, F is the applied load in grams, and L is the average diagonal length in µm.

Structural analyses of the precursor glass, nucleated glass, and final glass-ceramics were conducted using 27Al NMR. 27Al magic-angle spinning (MAS) and triple-quantum magic-angle spinning (3QMAS) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was conducted using an Agilent DD2 spectrometer and 700/54 Premium Shielded 16.4 T superconducting magnet, with a 27Al resonance frequency of 182.34 MHz. Glasses and glass-ceramics were crushed using an agate mortar/pestle and loaded into 3.2 mm low-Al content zirconia rotors for sample spinning at 22.0 kHz. 27Al MAS NMR data were collected under direct polarization using radio-frequency pulse widths of 0.6 µs, corresponding to a tip angle of p/12. A recycle delay of 5 s was chosen for signal averaging of 1000 transients. MAS NMR spectra were processed using commercial software, without apodization, and shift referenced to aqueous aluminum nitrate at 0.0 ppm. 27Al MAS NMR data were fitted in DMFit (https://nmr.cemhti.cnrs-orleans.fr/dmfit/), using the Czjzek lineshape function to account for distributions in the quadrupolar coupling constant and chemical shielding10. Neighboring satellite transition spinning sidebands were fit and used to describe an underlying contribution from the AlO4 resonances, and a weak background peak from Al in the zirconia rotors was also included in the fits.

27Al 3QMAS NMR data were taken with a hypercomplex pulse sequence with a Z filter11. Solid 3p/2 and p/2 pulse widths were optimized to 2.8 and 1.1 µs, respectively. The Z-filter was performed using a delay of 45.5 µs (one rotor cycle) and a soft reading pulse of 20 µs. 72 to 480 acquisitions at each of 100 t1 points were collected with recycle delays of 1–2 s. These data were processed and sheared using Agilent VnmrJ 4.2 (https://www.agilent.com) without additional line broadening and referenced to an external standard of aqueous aluminum nitrate at 0.0 ppm.

Electron microscopy by both SEM and TEM techniques was used to study the microstructure and partitioning of elements into the various phases. For SEM, a polished cross section of the glass-ceramic sample was prepared, and a conductive carbon coating was applied to reduce charging. Electron microscopy data was collected using a Zeiss Gemini 500 instrument operated at 5 kV. For TEM, samples were prepared by an in-situ FIB lift-out procedure using 30 keV Ga-ion beam of the FEI Quanta 3D 600 FEG dual beam FIB-SEM system. The final thinning was done using 5 keV ions to minimize amorphization. Electron microscopy data was collected using an aberration corrected FEI Titan Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) instrument equipped with Fishcione Annular Dark Field (ADF) detector, Super-X detector with four electron Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) sensors, Gatan Orius SC200D retractable CCD camera for TEM-mode diffraction. The microscope was operated at 200 keV.

The stress optic coefficient was measured at 546 nm using a diametral compression technique described in ASTM C770, with a measurement uncertainty of +/- 0.6 nm/cm/MPa. Glass and glass-ceramic discs, 12.7 mm in diameter and 7 mm in thickness with polished flats were used for the measurement.

Chemical strengthening and stress characterization

Ion exchange of the glass-ceramics was conducted by immersing polished samples (0.6 mm thick) in molten KNO3 held at 450 °C for various times.

Stress profiles resulting from ion exchange were characterized using a GlasStress SCALP-0512, a polariscope which uses scattered light in conjunction with a laser of modulated polarization state to provide through-thickness stress distribution. From the measured scattered light signal, the SCALP calculates optical retardation along the laser beam path, which is converted to ion exchange induced stress, with knowledge of the material stress optic coefficient.

Results and discussion

In this section the properties and characterization of the precursor glasses, the resulting glass ceramics, and the jeffbenite crystalline phase produced in the glass-ceramic are described.

Characterization of the jeffbenite crystalline phase

The jeffbenite-containing glass-ceramics reported here were produced using glass-ceramic melt-quench-reheat techniques13,14,15. The clear, annealed precursor glasses were subjected to various heat treatment schedules (ceram schedules) comprised of a nucleation step and subsequent crystalline growth step. The temperatures for these are nominally between 700 °C and 950 °C, holding for four hours at each step. Compositions, crystallization schedules and some property data of the precursor glasses and resulting glass-ceramics are shown in Table 1.

Comparison of the precursor glass properties with the glass-ceramic properties shows increases in Young’s modulus, density, fracture toughness, and hardness. The transformation from the precursor glass to the jeffbenite-containing glass-ceramic is accompanied by significant shrinkage of the material. This may be as high as 9% by volume. This is not surprising, as the density of natural jeffbenite is high, 3.57 g/cc16, whereas the precursor glass densities are on the order of 2.9 g/cc.

X-ray diffraction was used to characterize the phase composition and amounts of crystalline phases. The x-ray diffraction spectra for the glass-ceramics are shown in Fig. 1. Along with the major phase of jeffbenite, nanocrystalline ZrO2, with broad diffraction peaks is almost always present in the XRD spectrum, along with residual glass, which appears as a halo. Analysis of the XRD line widths suggests jeffbenite crystallite sizes on order of 20–50 nm, consistent with producing fairly transparent materials, albeit with some visible haze. As shown in Table 1, the weight fraction of jeffbenite in the glass-ceramics ranged from 15 to 62%.

In Table 2a summary of the d-spacings and cell volumes associated with the jeffbenite crystals in the glass-ceramics is compared to naturally occurring jeffbenite. The peaks in the glass-ceramic correspond quite well to the naturally occurring jeffbenite, noting that the jeffbenite produced in the glass-ceramic does not have the same chemistry as the naturally occurring crystal. This will lead to small differences in d-spacings when comparing the two. Further, it is noted that the reported [3 2 5] peak of naturally occurring jeffbenite appears to be split into a doublet in the glass-ceramics. The chemistry of the jeffbenite phase in the glass-ceramics will be addressed later, however, it is proposed that some incorporation of zirconium into the jeffbenite, perhaps into the M1 site, can be responsible for this splitting. Table 2 also shows that the cell volumes of the jeffbenites contained in the glass-ceramics are larger than that of the mineral.

Raman characterization of Composition 6, Table 1, both in precursor glass form and as the glass-ceramic, is compared to the literature5 for a naturally occurring single crystal jeffbenite (Fig. 2). While not an exact match for the single crystal jeffbenite, correspondence between the major peaks in the spectra of the glass-ceramic and the mineral is consistent with jeffbenite formation from the precursor glass. Also note that the main peaks associated with jeffbenite appear only upon ceramming the precursor glass. Differences between the spectral data for the mineral and the glass-ceramic can arise because the jeffbenite formed in the glass-ceramic is not the same stoichiometry as the single crystal; further, the small grain size and presence of the residual glass broaden the lines associated with the structural units.

Element mapping using SEM and TEM was used to estimate partitioning between the jeffbenite crystals and the residual glass in Composition 1. In this case, ceram conditions were used to increase the crystallite size, which aided in the analysis. Figure 3 shows the grey scale SEM image along with Mg, Al, Zr, Si, Na and K element maps. The darkest phase shown in the SEM image is the residual glass phase; the bright white star-like crystals are ZrO2, as shown by comparison with the Zr map, and the mid-grey blocks are the jeffbenite crystals, homogenously dispersed in the glass phase. The Mg map clearly shows high Mg in the crystalline jeffbenite phase, with little Mg partitioned into the residual glass. The Al map indicates that aluminum is more strongly partitioned into the glassy phase than in the crystal phase in this particular composition. The Si map appears to show silicon in both major phases; from the bulk composition, and jeffbenite stoichiometry, one would expect a higher Si level in the residual glass. The potassium map reveals that essentially all the potassium is in the residual glass; this is consistent with the size argument for various cations offered above. Inspection of the sodium map suggests there is more sodium in the glassy phase, however, there could be some in the crystals, as is reported for naturally occurring jeffbenite. Sodium partitioning is less conclusive than that shown by the potassium map.

Cation mapping of a jeffbenite glass-ceramic, Composition 1, Table 1. The elemental EDS maps correspond to the grey-scale SEM images.

Nucleation and crystallization in jeffbenite glass-ceramics

This section presents x-ray diffraction data, in-situ x-ray diffraction data, and 27Al NMR results, revealing the structural changes that occur on heat treatment to produce the jeffbenite-containing glass-ceramic.

Nucleation

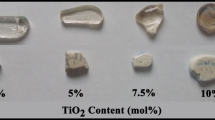

Zirconia (ZrO2) is a well-known nucleating agent for bulk internal crystallization in glass17,18. We have found that it is required for the nucleation of jeffbenite from a precursor glass matrix. This nucleation usually requires from 5 to 10 wt% ZrO2 added to the glass batch. Typically, after crystallization of the glass to produce the glass-ceramic there are one or two zirconia phases present: a tetragonal ZrO2 phase in which some TiO2, up to about 20 mol%, may replace zirconia. Solid solution between ZrO2 and ZrTiO4 is well known19.

There is also a cubic phase, that does not correspond to pure ZrO2 by XRD analysis; in fact, the lattice spacing of the cubic ZrO2 identified here is significantly smaller than that of pure cubic ZrO220. It is expected that enough MgO is present to stabilize the cubic phase, with roughly 16 mol % incorporation possible21. Some TiO2 and small amounts of SnO2 may also be present in this phase. While significant amounts of Mg can be incorporated, the effect on the lattice size with the substitution is negligible22. However, the presence of TiO2 can shrink the ZrO2 lattice considerably, consistent with parameters found in this study23. The size of the substituted cubic ZrO2 phase estimated from XRD line broadening is about 7–10 nm.

In-situ HTXRD was used to study the nucleation process using Composition 2, Table 1. A polished disc of precursor glass was heated from room temperature to 775 °C, with the XRD spectrum measured after holding at temperature from time zero to 10 h. As Fig. 4 illustrates, a phase identified as a cubic zirconia is observed to develop by 0.75 h at 775 °C, reaching the maximum amount with roughly two hours at temperature. No other crystalline phases are precipitated during this nucleating heat treatment step. Symbols representing jeffbenite also appear on the graph, demonstrating that no detectable crystalline jeffbenite is formed at this temperature within 10 h of hold time.

However, holding for continued time at 775 °C shows jeffbenite appearing at roughly 15 h (Fig. 5).

The amount of jeffbenite and cubic phase formed as a function of hold time in this experiment is plotted in Fig. 6. The graph shows that a significant amount of jeffbenite (right axis) is formed even at this relatively low temperature. More significantly, however is the relationship between the evolution of the ZrO2 phase and the jeffbenite phase, noting that the jeffbenite begins to precipitate roughly when the amount of ZrO2 reaches its maximum.

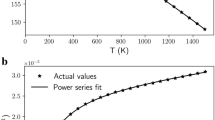

The HTXRD experiments also reveal structural changes in the cubic ZrO2 species during nucleation and early crystallization of the jeffbenite phase. This is illustrated by Fig. 7 where the d-spacings of the main substituted c-ZrO2 [111] and main jeffbenite peaks [204] are shown as a function of time at 775 °C. The c-ZrO2 lattice moves to smaller d-spacing with time at temperature, reaching a fairly constant level after about 5 h. At about 16 h of hold time there is sufficient jeffbenite appearing in the XRD spectrum to determine its lattice spacing. Note that the difference in lattice spacings of the two phases is relatively close, about 3.6%. The shrinking of the c-ZrO2 lattice with time may be related to it incorporating Ti, Mg, and/or Sn.

With respect to the c-ZrO2 phase, it is known that both TiO2 and MgO can form limited solid solution with ZrO2, especially in the cubic form19,21,23. We have found experimentally that a significant replacement of ZrO2 by TiO2 increases transparency, with a corresponding decrease in jeffbenite crystal size ( to < 25 nm). We suggest that the first crystalline nuclei, high in ZrO2, are actually a Mg-stabilized cubic form of ZrO2. This is not, in itself, unanticipated, because the precursor glasses contain > 30 mol % MgO. However, this cubic phase without TiO2 contains a main diffraction peak [111] of 2.91 Å, smaller than the main jeffbenite peak: [204] at 2.67 Å, an 8.2% discrepancy. When TiO2 replaces a significant percentage of the cubic zirconia, the main peak decreases to 2.75 Å, not surprising considering the smaller ionic radius of Ti compared to Zr.

It should be said that in many cases of internal nucleation in glass, amorphous phase separation precedes the precipitation of crystalline nuclei, often seen after annealing of the precursor glass. This may be the case here, but it would have to be extremely fine, as high magnification electron microscopy of the original glass appears featureless.

Crystallization

After nucleation, typically occurring in the temperature range of 700– 800 °C, crystallization of jeffbenite starts to form at or above 775 °C and is usually complete after 4 h at 850 °C. Notably, if one uses a glass of nominal precursor glass composition of Mg3Al2Si3O12, little if any jeffbenite is produced. However, with glass compositions like those in Table 1, jeffbenite is always the major crystalline phase, forming between 775 and 900 °C.

Again, appealing to in-situ HTXRD studies, one can observe the evolution of the phase assemblage of Composition 2 (Table 1) as it develops from nucleation, where the XRD spectrum was measured after holding the material for one hour at temperature intervals between 850 °C and 1000 °C (Fig. 8). As was shown in Fig. 3, a phase identified as cubic zirconia, presumably substituted, is present from the nucleation step performed at 780 °C. Subsequent jeffbenite formation is found by increasing the temperature to 850 °C. The amount of cubic zirconia decreases as the temperature is increased and eventually tetragonal zirconia, the more stable form of the oxide, appears around 950 °C, at the expense of the cubic form. Jeffbenite is the major phase, reaching a maximum at 950–970 °C. In all jeffbenite glass-ceramics studied, the jeffbenite breaks down, typically in the 900–1050 °C range after about 1 h of heat treatment time, producing the more the stable phases in the magnesium silicate system: enstatite (MgSiO3) and forsterite (Mg2SiO4). This transformation also occurs at somewhat lower temperatures if the glass-ceramic is held for longer times. This behavior is typical of metastable phases crystallized from glass. It’s noted that both these phases have been produced in other bulk nucleated glass-ceramics, without the formation of jeffbenite13,15.

The cubic Zr(Ti, Sn, Mg)O2 species is usually a minor phase accompanying the jeffbenite during crystallization, the amounts being generally small or in some cases like Composition 4 (Table 1) even undetectable in the glass-ceramic. This compares to the large amounts of TiO2 and ZrO2 in the bulk composition, indicating that these components might enter the jeffbenite phase, as well as precipitate as the oxides (see the element map in Fig. 3 showing discrete ZrO2 crystals). These components, especially ZrO2, are largely insoluble in typical alkali aluminosilicate residual glasses.

In the system described above where ZnO is substituted for MgO, or Zn2+ ⇔ Mg2+, (Composition 4) the unit cell dimensions are seen to increase from a typical value of 788 Å3 found in Composition 2 to 800 Ᾰ3 with the Zn2+ substitution. The XRD pattern is shown in Fig. 9. Notably, there are no obvious ZrO2 lines in this XRD pattern, but there appears to be peak at 2θ = ~32°, at the same point where the main line of earliest cubic ZrO2 phase to precipitate was observed in Figs. 3 and 4.

XRD of Zn-containing jeffbenite glass-ceramic Composition 4 (Table 1) cerammed at 780 °C-4, 850 °C-4 h.

For the glass compositions studied here, a potential solid solution within the jeffbenite composition space is as follows: (Zr, Ti)O2 + MgO ⇔ Al2O3, or in cation form (Zr, Ti)4+ + Mg2+ ⇔ 2Al3+. In this case, the solid solution would be Mg3 + x(Zr, Ti)xAl2−2xSi3O12. We believe, based on calculations involving the bulk composition and weight% jeffbenite formed, that x can range between 0.2 and 0.7, a typical value being 0.5, suggesting the following stoichiometry: Mg3.5(Zr, Ti)0.5AlSi3O12.

It is interesting to note that in Composition 5 (Table 1), the sum of ZrO2 + TiO2 is 11.0 wt%, while in the Rietveld analysis, the total of cubic and tetrahedral ZrO2 oxide solid solutions, (Zr, Ti)O2, is only 5.0 wt%. It appears that about half of the ZrO2 + TiO2 resides in the jeffbenite phase in this composition. In the Zr elemental map of Composition 1 (Fig. 4), one can see bright areas of the ZrO2 oxide phase and darker, but significant Zr in the larger jeffbenite crystals and black areas of residual glass with no zirconia. These observations support the solid solution proposal for jeffbenite given above.

With the highly coordinated aluminum in jeffbenite, aluminum NMR is well-suited for its characterization in jeffbenite-containing glass-ceramics and the corresponding precursor glass. Figure 10 reveals the Al speciation from 27Al MAS NMR studies of the precursor glass of Composition 2 (Table 1), along with the nucleated material, and the glass-ceramic resulting from the full heat treatment.

The large broad peak near 60 ppm 27Al NMR shift in the precursor glass spectrum corresponds to tetrahedral 27Al, typical in aluminosilicate glasses. A second resonance, appearing on the shoulder of the tetrahedral Al, is consistent with AlO5 species. There is also a small peak near 0 ppm chemical shift, which corresponds to octahedral Al, rare in silicate glasses but not surprising in this composition system from which jeffbenite, spinel and sapphirine, all with octahedral Al, can form. Octahedral Al begins to appear during the nucleation step (dashed line); this higher coordination occurs without precipitating jeffbenite, as was shown in Fig. 3, suggesting that there is structural rearrangement of the glass structure to the denser jeffbenite-like structure during nucleation. The fully cerammed glass-ceramic contains a significant amount of AlVI represented by the dot-dash curve. The large increase in the 6-coordinated aluminum upon crystallization is due to its presence in the octahedral site in crystalline jeffbenite2,5.

This particular glass-ceramic is roughly 62:2:36 (wt) jeffbenite: zirconia: residual glass (Table 1). The jeffbenite in this composition is subaluminous in comparison to natural jeffbenite, with about half the Al2O3 replaced by MgO + Zr(Ti)O2, according to the solid solutions described earlier. The atomic % of octahedral Al after nucleation at 4 h is ~ 15%; the fully cerammed glass-ceramic is estimated to have ~ 42% atomic % octahedral Al. While the 42 atomic % is not exactly the value obtained from Rietveld analysis, the correspondence is reasonable.

The 4-coordinated aluminum in the glass-ceramic spectrum (Fig. 10) is assigned to the aluminum partitioned into the residual glass. The slight shift in its resonance from the precursor glass spectrum is consistent with the residual glass of the glass-ceramic being essentially an alkali aluminosilicate glass that is now diminished in MgO, as that oxide has been partitioned into the jeffbenite.

Note that in the suggested solid solution of jeffbenite in the glass-ceramic described above, the Al2O3 level is dramatically decreased relative to both nominal and analyzed natural jeffbenite; this could result in less octahedrally-coordinated Al in the glass-ceramic-derived jeffbenite. This relaxation of the demand of having a significant amount of higher coordinated Al in the jeffbenite reported here may contribute to the success of the low-pressure synthesis in these materials. It is known that octahedrally coordinated Al is uncommon in silicate minerals formed at low geological pressure, a notable exception being mullite, Al6Si2O13, which has only 40 mol percent SiO2.

Possible mechanism of formation of jeffbenite from glass

This section proposes a templating mechanism for forming the high pressure jeffbenite at ambient pressure, where a particular structure of a zirconium-containing phase acts as a nucleation site.

The formation of jeffbenite crystals, largely consistent with observation of precipitation of tiny ZrO2-rich particles during nucleation, begs the question: how is a dense phase like jeffbenite formed in a glass by simple heat treatment in the 750–950°C range, at ambient pressure, especially since it has only been synthesized at pressures above 6 GPa in compositions based on an average of Ti-containing jeffbenite. These pressurized compositions contained in wt%: 8.9 Fe2O3, 3.6 TiO2 and 3.1 Cr2O3, in addition to the normal components: MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2. The jeffbenite occurred with enstatite (MgSiO3) and pseudobrookite (Fe2TiO5) at 6.3 GPa and in higher amounts with garnet at 9.6 GPa9.

As suggested by the HTXRD and Al NMR data, the answer to the ambient pressure synthesis may involve a particular geometric match between the presumed nucleating phase of ZrO2 and the jeffbenite structure. This “templating” may then initiate structural reorganization of the glass network, leading to precipitation of the jeffbenite crystal. The data of Figs. 5 and 6 illustrate that the jeffbenite forms only after the presumed substituted c-ZrO2 is formed. Figure 8 shows the proximity d-spacings of the [111] plane of c-ZrO2 and the main jeffbenite peak [204] plane, a 3.6% difference. This result suggests that the precipitation of the jeffbenite crystal at 1 atm pressure might be enabled by templating of the [204] face of the jeffbenite crystal onto the [111] face of the c-ZrO2 nucleus.

Theoretical calculations describing the pressure-temperature (P-T) phase diagram of part of the MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 system have recently been made6. The results suggest that stoichiometric jeffbenite (Mg3Al2Si3O12) can be stable at pressures of only 2.4 GPa, at temperatures less than 1100 K. This diagram is reproduced in Fig. 11. The fact that jeffbenite crystallizes from the compositions reported in Table 1 at ambient pressure and 800 °C, although under non-equilibrium conditions, supports the general validity of the P-T diagram as calculated.

Pressure–temperature stability field of the pure Mg end-members, jeffbenite and pyrope, calculated using Perple_X356.

Properties of the jeffbenite glass-ceramics

This section contains material property characterization and optical characterization of the jeffbenite-containing glass-ceramics, as well as results on how the materials can be chemically strengthened.

Mechanical properties

Young’s modulus, shear modulus, Poisson’s ratio and fracture toughness were determined for a number of compositions. Table 1 compares the values for several of these, both for the precursor glass and after heat treatment, as the glass-ceramic. Inspection of the table shows that all the values increase upon precipitation of the crystalline phase. A larger data set is shown in Fig. 12, where Young’s modulus as a function of wt% jeffbenite in the glass-ceramic, determined by the Rietveld method, is plotted showing a general trend of increasing modulus with increasing crystalline content.

The trend is consistent with the idea that the measured elastic modulus of the glass-ceramic is the composite modulus of the jeffbenite crystalline phase (presumably high, based on density and bulk modulus of the mineral3,6, and the residual glass. However, making a proper estimate of the upper and lower bounds of the elastic modulus in a polycrystalline material to compare to the data shown here requires knowledge of the elastic coefficients of each phase; these are not available for jeffbenite.

An interesting composition is represented by the open symbol, corresponding to Composition 6 (Table 1). This composition is estimated to be the Mg3.5(Zr, Ti)0.5Ti0.2AlSi3O12 solid solution stoichiometry, a stoichiometric composition where some (MgO+(Zr, Ti)O2) replaces Al2O3, and that contains only ZrO2 and TiO2 nucleating agents as other oxides. This composition achieves ~ 60 wt% crystallinity after heat treatment, with an elastic modulus of the glass-ceramic determined to be 168 GPa.

Figure 13 shows the relationship between fracture toughness of the glass-ceramic and wt% jeffbenite precipitated, with a modest positive correlation.

Due to microstructural influences, glass-ceramic materials can often have high fracture toughness, even greater than 2 MPa√m13,24. The values reported here, while higher than many glasses and higher than the corresponding precursor glasses, are on the low end for glass-ceramics. This may be due to the relatively small grain sizes and limited interlocking of the microstructure, a mechanism that is often operative in tough glass-ceramics13.

Chemical strengthening

The glass-ceramic materials described here contain sodium, which can be available for chemical ion exchange with other alkali metals. Of practical concern is the exchange of the sodium ion with a larger ion, potassium for example, which results in the production of compressive stress on the surface of the part. This process is well-known for strengthening glass25 and glass-ceramics26 to improve mechanical performance.

Two compositions were ion exchanged by immersing 0.6 mm thick x 25 × 25 mm parts with polished flats into a molten bath of KNO3 at 450 °C for different times. The resulting stress profiles were then measured using SCALP. Central tension (CT) is the maximum value of tension at the center of the part and is a metric that is used to evaluate the stress profile. Compositions 1 and 2 in Table 1 were studied. Both compositions can undergo ion exchange, with significant values of CT (Fig. 14). Composition 1 glass-ceramic has interionic diffusivity that is sufficiently fast such that the maximum in central tension can be reached in 15 h with a bath temperature of 450 °C. This is similar to other glasses and glass-ceramic materials.

Referencing the composition maps of Fig. 3, where a high degree of Na ion partitioning is seen in the residual glass phase, it’s then clear that the potassium for sodium ion exchange takes place in the residual glass phase and not in the jeffbenite crystalline phase.

Optical properties

Glass-ceramics made from Compositions 1 and 2, Table 1, are optically transparent, albeit with some haze, despite a large difference in refractive indices between jeffbenite (1.77), zirconia (2.18) and the more siliceous residual glass, estimated at around 1.5. These differences would produce significant Rayleigh scattering except at very small crystal size15,27. The low optical anisotropy of jeffbenite (0.012)28 likely does not contribute to the optical haze that is observed in some compositions. Figure 15 is an electron micrograph of Composition 2, revealing aggregates of crystals of jeffbenite, their crystallize size calculated from XRD line-broadening to be roughly 25 nm. The reason for the aggregation of the fine jeffbenite nanocrystals is not known but may be related to the original positioning of the zirconia nuclei.

Left, SEM micrograph of transparent jeffbenite glass-ceramic from Composition 2, Table 1, revealing white zirconia nuclei, grey jeffbenite apparently in attached planar and linear groupings (light grey) enclosing areas of residual glass represented by the darker regions. Note 100 nm scale bar. Also shown (right) is a polished sample (0.6 mm thick) of a jeffbenite glass-ceramic.

Given the small grain size in the jeffbenite glass-ceramics and the low optical anisotropy of the crystal itself, composition studies were carried out to understand whether transparency was being limited by the presumably large refractive index mismatch between the crystalline phases and the residual glass. The largest refractive index difference in the glass-ceramic is between the ZrO2 crystallites and the residual glass. This may be limiting transparency, however the ZrO2 crystallites are much smaller than the wavelength of light and are present in low volume fraction. These observations would suggest that this mechanism is not the primary one limiting transparency in these materials. Given the presumably large refractive index difference between the jeffbenite crystals and the residual glass, composition studies were undertaken where small additions of oxides that would likely be excluded from the crystals and so partition into the glass were investigated. Here the purpose was to raise the refractive index of the glass closer to that of the jeffbenite. Additions of SrO, BaO, and La2O3 did not, however, yield improvements in transparency. Work is continuing to understand the optical properties of these glass-ceramics.

Conclusions

Jeffbenite, a phase known to occur in nature under high pressure conditions, can be produced at ambient pressure in a glass-ceramic material, being precipitated from a glass precursor. X-ray diffraction, Raman spectral characterization, and 27Al NMR are all consistent with the production of the jeffbenite phase at ambient pressure. Further, the properties of the final glass-ceramic are consistent with the formation of this high-pressure phase, having relatively high density and high elastic modulus. The flexibility of the precursor glass composition permits the production of a range of jeffbenite stoichiometries. The jeffbenite compositions reported here likely have cation substitutions that differentiate them from the naturally occurring material. Those substitutions may allow this high-pressure phase to be stabilized at the lower forming pressure reported here. A mechanism for formation of jeffbenite from glass at 1 atm pressure is presented. A nucleation process relying on formation of a doped cubic ZrO2 phase, with subsequent templating of the jeffbenite is suggested. Glass-ceramics based on jeffbenite may be transparent or opaque, have high modulus and hardness, and can be strengthened by ion exchange for a possible range of technical uses.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Also, they are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Harris, J. T. et al. A new tetragonal silicate mineral occurring as inclusions in lower mantle diamonds. Nature 387, 486–488 (1992).

Finger, L. & Conrad, P. G. The crystal structure of tetragonal almandine-pyrope phase: a re-examination. Am. Mineral. 85, 1804–1807 (2000).

Wang, F. et al. High pressure crystal structure and equation of state of ferromagnesian jeffbenite: implications for stabilitywith transition zone and uppermost lower mantle, Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 176, 93–105 (2021).

Anzolini, C., Drewitt, J., Lord, O. T., Walter, M. J. & Nestola, F. New stability field of jeffbenite (ex TAPP): Possibility of super-deep origin. Am. Geophys. Union (2016).

Nestola, F. et al. Tetragonal almandine-pyrope-phase, TAPP, finally a name for it, the new mineral Jeffbenite. Mineral. Mag. 80 (7), 1219–1232 (2016).

Nestola, F., Prencipe, M. & Belmonte, D. Mg3Al2Si3O12 Jeffbenite inclusions in super-deep diamonds is thermodynamically stable at very shallow Earth’s depths. Sci. Rep. Nat. Port. 13 (2023).

Smyth, J. R. et al. Ferromagnesian jeffbenite synthesized at 15 GPa and 1200C. Am. Mineral. 107, 405–412 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Thermoelastic properties of Fe3+-rich Jeffbenite and applications to superdeep diamond barometer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, GL106908 (2023).

Armstrong, L. & Walter, M. Tetragonal Almandine Pyrope phase (TAPP): retrograde Mg-perovskite from subducted oceanic crust? Eur. J. Mineral. 24, 587–597 (2012).

Massiot, D. Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid state NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Chem. 40, 70–76 (2002).

Amoureux, J. P., Fernandez, C. & Steuernagel, S. ZFiltering in MQMAS NMR. J. Magn. Reson. A. 123, 116–118 (1996).

GlasStress Estonia.

Holand, W. & Beal, G. H. (eds) Glass-Ceramic Technology 3rd Edn (The American Ceramic Society and Wiley, 2020).

Beall, G. H. Chain silicate glass-ceramics. J. Non-Crystalline Solids. 129, 163–173 (1991).

Beall, G. H. & Duke, D. A. Transparent glass-ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 4, 340–352 (1969).

Jeffbenite Mineral information, data, and requirements Mindat.org/min 46574. https://www.mindat.org/min-46574.html.

Tashiro, T. & Wada, M. Glass-ceramics crystallized with zirconia Advances in Glass Technology, Plenum, New York, 18–19 (1963).

Beall, G. H., Karstetter, B. R. & Rittler, H. L. Crystallization and chemical strengthening of stuffed β-quartz glass-ceramics. J. Amer Ceram. Soc. 50, 67–74 (1967).

Levin, E. & McMurdie, H. Phase diagrams for ceramists: Fig. 4452 (ZrO2-TiO2). Natl. Bureau Stand. Am. Ceram. Soc. (1975).

Ploc, R. A. The lattice parameter of cubic ZrO2 on zirconium. J. Nucl. Mater. 99, 124–128 (1981).

Duwez, P., Odell, F. & Brown, F. H. Stabilization of zirconia with Calcia and Magnesia. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 35, 107–113 (1952).

Kurakhmedov, A. E. Study of the effect of doping ZrO2 ceramics with MgO to increase the resistance to polymorphic transformations under the action of irradiation. Nanomaterials 11, 3172–3183 (2021).

Zhao, M. & Pan, W. Effect of lattice defects on thermal conductivity of Ti-doped Y2O3-stabilized ZrO2. Acta Mater. 5496–5503, 61 (2013).

Honma, T., Maeda, K., Nakane, S. & Shinozaki, K. Unique properties and potential of glass-ceramics. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan. 130, 545–551 (2022).

Gy, R. Ion exchange for glass strengthening. Mater. Sci. Eng., B. 149, 159–165 (2008).

Beall, G. H. et al. Ion exchange in glass ceramics. Front. Mater. 3:41, (2016).

Dunch, T. & Jackson, S. D. Rayleigh scattering with material dispersion for low volume fraction transparent glass ceramics. Opt. Mater. Express. 12, 2595–3609 (2022).

Anthony, J. W., Bideaux, R. A., Bladh, K. W. & Nichols, M. C. Handbook of Mineralogy: Jeffbenite (Mineral Data Publishing, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bryan Wheaton for the HTXRD work and fruitful discussion, Randy Youngman for the NMR data, Galan Moore for Raman, Sarah Roberts for SEM, and Aram Rezikyan for TEM. Thanks also to Amanda Reese and Dan Brown for ceram and characterization work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H.B. did the glass composition work, directed ceram studies, and worked on mechanistic studies. J.P.F. participated in ceram and characterization work. C.M.S. participated in material characterization and mechanism of jeffbenite formation studies. G.H.B. and C.M.S. wrote the manuscript with J.P.F. editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, C.M., Beall, G.H. & Finkeldey, J.P. Formation of the high pressure jeffbenite phase from glass at ambient pressure. Sci Rep 15, 18813 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02967-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02967-z