Abstract

The degree of overlap between the mechanisms underlying attention control and motor planning remains debated. In this study, we examined whether microsaccades—tiny gaze shifts occurring during fixation—are modulated differently by covert attention and motor intention. Eye movements were recorded using high-precision eye-tracking. Our results reveal that whereas in a covert attention task, microsaccade direction was biased toward the attended location, in a motor planning task, microsaccades were not directionally biased toward the cued location. Further, the rate of microsaccades over time varied between the two tasks and whereas in the attention task a clear correlation emerged between microsaccade rate and visual detection reaction times across subjects, there was no relationship between microsaccade rate and reach/saccade reaction times. This study advances our understanding of the relationship between attention and motor processes, suggesting that the mechanisms governing microsaccade generation are differentially influenced by motor planning versus spatial covert attention engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is known that visual resolution drops drastically as we move away from the center of gaze. Normally saccades are used to compensate for this limitation and to sample the visual scene with the high-resolution fovea. However, peripheral information can also be enhanced through covert spatial attention independently of eye movements. Covert attention, as an inner eye, focuses processing resources at the attended location in the visual periphery1,2. The problem of whether covert attention and motor planning share the same processes has a relatively long history and has been intensely debated. It has been proposed that allocation of attention is inherently intertwined with the process of motor planning towards the attended location3, and that spatial attention and motor planning share the same neural substrates4. Neurophysiological and neuroimaging data seem to support this idea, as neural circuits underlying eye movements5,6 and upper limb ones7,8,9,10,11,12,13 are also involved in directing covert spatial attention. However, a recent study14 showed that attention and motor planning occur within predominantly distinct neuronal populations. Other studies discuss these processes as potentially capable of being behaviorally decoupled3,15,16,17, and their obligatory yoking as pathological18. Still, to this date the coupling of attention and motor planning is under debate.

It is known that, even if saccades do not occur during fixation when covert attention is allocated, the eye is constantly in motion and small saccades of less than half a degree, microsaccades, are performed. Microsaccades occur frequently in a variety of everyday tasks, from reading19,20,21 to exploring fine details22,23,24,25 (for a review on this topic see26,27. Although covert attention can be shifted without performing a microsaccade28,29,30, it has been demonstrated that the direction of microsaccades is influenced by the direction of covert attention shifts28,29,31,32,33,34. Hence, microsaccades have been considered as a useful indicator of the direction of covert attention in standard spatial cueing tasks31,32,34,35. Previous research has shown that microsaccade rate can be influenced by motor preparation for both manual responses36 and saccades37,38. However, a direct comparison of the microsaccadic behavior during covert attentional shifts and during movement planning with different effectors has yet to be explored.

Here, to understand whether covert attention and motor planning modulate microsaccades in distinct ways, we examined microsaccades directional bias, rate and interaction with reaction times during covert attention allocation and during motor planning. We used a state-of-the-art, high-precision digital dual Purkinje image (dDPI) eye-tracker39 to monitor gaze position at the finest scale during fixation. In the first experiment, covert spatial attention was directed prior to the visual detection of a peripheral target. The second experiment included the same sequence of experimental epochs as the first, with the addition of a motor planning phase, followed by the execution of either saccadic or reaching movements toward a cued peripheral location. Our results indicate that motor planning and covert spatial attention differently modulate microsaccade rate and directionality over time. Remarkably, spatially biased microsaccades toward the cued location are absent during the planning of a motor action.

Results

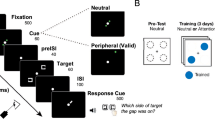

We conducted two experiments: the first one (Fig. 1A), a perceptual detection endogenous attention task, required participants to allocate spatial covert attention and detect a low contrast stimulus (Fig. 1A–B). In the second experiment (Fig. 1C), a motor preparation and execution task, participants received a spatial information about where to plan an action, followed by information about which movement to plan; then, they executed either a saccade or a reaching movement toward the target. Trials were divided into different epochs; in the encoding epoch, two differently colored circles were presented 5° away from a central grey fixation point for 500 ms (Fig. 1A and C). In the subsequent direction cue epoch (500–1200/1500 ms from trial start), the fixation point changed color and participants covertly attended to the circle of the corresponding color. The first two epochs were the same in both experiments. Following the cuing phase in the perceptual detection experiment, a black low-contrast target appeared for 50 ms in one of the two circles (target epoch), and participants had to respond by releasing a button as soon as they detected the target. In the motor preparation experiment, instead, a 50 ms auditory cue instructed participants to plan either a saccade (low tone) or a reaching (high tone) toward the cued target (in saccade trials, toward the circle on the screen, while in reach trials toward a button on a board) (motor planning epoch 1200/1500–2200/2500 ms from trial start). The movement was then executed after a second 50 ms auditory cued was delivered. We investigated microsaccade dynamics during covert attention allocation and during motor preparation (Fig. 1D).

Experimental paradigm. (A) Perceptual Detection Experiment: Participants were instructed to maintain fixation on a central marker. Two differently colored parafoveal circles (1-deg diam) simultaneously appeared 5 degrees to the right and to the left of the fixation point for 500ms (encoding epoch). Then, the circles turned gray, while the central marker changed color, thereby serving as a cue for directing covert attention to the corresponding side (direction cue epoch, 700-1000ms). The cue was valid in 80% of trials. A low-contrast target then appeared in one of the two circles, and participants had to release a button as soon as the target was detected. (B) Valid and invalid trials in the Perceptual Detection Experiment. (C) Motor Preparation Experiment: the first two epochs were identical to those in the Perceptual Detection Exp. with the exception of cue validity (100% validity). After the direction cue epoch, an auditory cue instructed participants to prepare either a reach or a saccade toward the covertly attended target (motor planning epoch). A second auditory cue served as a go signal to perform the action. (D) An example of fixational eye movements during the course of a typical trial.

Microsaccade rate remains constant during motor planning

Consistent with31,32,36,40, in the perceptual detection task (Fig. 2, green line), microsaccade rate showed a stereotypical pattern. After an initial ≈ 150 ms suppression, microsaccade rate peaked around 200 ms following stimuli onset when participants were required to encode the spatial information from the color of the two peripheral circles (encoding epoch). A similar pattern was also seen when covert spatial attention was spatially allocated following the central cue instruction (direction cue epoch). Toward the end of this epoch, the rate of microsaccades was gradually suppressed. In the motor preparation experiment (Fig. 2, brown line), the microsaccade rate paralleled the pattern observed in the detection experiment. However, despite the encoding and direction cue epoch being identical in the two experiments, in the motor preparation experiment microsaccade rate was not suppressed to the same degree at the end of the direction cue epoch (one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance, [F > 18.069, p < 0.001]). The rate remained stable around 1 microsaccade/s and remained approximately constant in the subsequent epochs. Therefore, there was a significant suppression when participants anticipated a low-contrast target for visual detection, but not when they anticipated an auditory cue to guide their motor action planning. In the motor planning epoch microsaccade rate remained constant and was not modulated by whether a reach or a saccade had to be planned (one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance, [F < 1.76, p > 0.05]).

Time course of microsaccade rate. (A) Microsaccade rate in both experiments during the Encoding and the Direction cue epochs. (B) Microsaccade rate in the reach and saccade planning epoch of the motor preparation experiment. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The asterisk marks a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001, one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance).

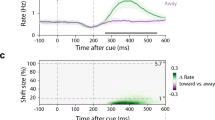

Microsaccades attention-related directional bias is absent during motor planning

The bias of microsaccade direction toward the covertly attended location is a hallmark of covert attention. In line with previous work31,32,40, we observed this bias in the direction cue epoch. To investigate how microsaccade direction changed over time, microsaccades were categorized into three groups: ‘Toward’ (aligned with the direction of the cue), ‘Away’ (opposite to the direction of the cue), and ‘Other’ (microsaccades oriented vertically, either up or down) (see Fig. 3, left and method for detail). During covert spatial attention allocation in both experiments, microsaccade directionality was biased toward the cued location (Fig. 3A–B). Consistent with previous findings41, this bias occurred when microsaccade rate peaked (around 200 ms following stimuli onset) in the direction cue epoch.

However, even though the direction cue epoch was identical in the two experiments, we observed a different time course of the effect. In the detection experiment, from 240 to 340 ms after the direction cue onset (the time frame of covert endogenous attentional shifts2,42, the probability of microsaccades being directed toward the cued hemispace was highest, (Fig. 3A, one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance: Toward vs. Away [F > 11.927, p = 0.009]; Toward vs. Other [F > 12.145, p < 0.001]). Interestingly, in the motor preparation experiment, this microsaccade directional bias occurred earlier, from 160 to 260 ms (Fig. 3B, one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance: Toward vs. Away [F > 12.125, p = 0.005]; Toward vs. Other [F > 11.179, all p < 0.01]).

Our findings show that, not only did the microsaccade rate remain constant in this period, but also no microsaccade bias in the cued direction was observed during both saccade and reach planning (Toward vs. Away, Fig. 3C–D, [all F < 8.99, all p > 0.05]). Therefore, these results support the idea that motor planning and any possible attention involvement in this period do not influence microsaccade directionality.

Microsaccade direction over time. Microsaccade direction was binned into three categories. The probability of microsaccade direction falling in each category is depicted in the graphs together with the corresponding microsaccade rate over time as a reference. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks mark a statistically significant difference (one-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance). (A) Perceptual detection experiment, direction cue epoch. (B) Motor preparation experiment, direction cue epoch. (C) Motor preparation experiment, motor planning epoch (reach trials). (D) Motor preparation experiment, motor planning epoch (saccade trials). In each graph, periods with a significant difference between the probability of having microsaccades: (i) directed towards the cued location and directed to the opposite hemifield (black continuous line); (ii) directed towards the cued location and directed to other locations (black dashed line); (iii) directed to the opposite location and directed to other locations (grey dashed line), are highlighted.

Microsaccades directed toward the attended location are not associated with faster reach/saccade reaction times

Consistent with previous research1,43, we found that reaction times in the perceptual detection experiment were modulated by cue validity (one-way repeated measure ANOVA [F(1,6) = 11.107, partial eta squared = 0.649, p = 0.016]; Friedman’s test, p = 0.008; Fig. 4A), with RTs in valid trials (mean RT = 387.56 ms, standard deviation = 83.48) significantly faster than those in invalid trials (mean RT = 452.45 ms, standard deviation = 99.21). Given that previous research has linked the microsaccade directional bias to covert attention shifts31,32,40,44, we expected beneficial effects on manual detection reaction times to occur only within the time window in which the microsaccade direction bias was present. To test whether microsaccade directionality was related to response reaction times, in the valid trials of both experiments, we selected the first microsaccade after the onset of the directional bias. The onset of the directional bias was defined as the time window in which the probability of microsaccades being directed toward the cued hemispace was statistically different from the probability of microsaccades in the opposite direction of the cued location and in other directions (Fig. 3A–B). We then categorized the trials based on the direction of the first microsaccade in these windows as congruent, incongruent, or other (see methods for details), depending on whether its direction aligned with the side of the subsequent target appearance. In agreement with a previous study44, we found a small but consistent modulation of RT based on the microsaccade directionality in the perceptual detection experiment (one-way repeated measure ANOVA [F(2,12) = 5.059, partial eta squared = 0.457, p = 0.026]; Friedman’s test, p = 0.018; Fig. 4B), with RTs in microsaccade congruent trials (RT = 385.39 +/- 76.81 ms) being lower than RTs in trials characterized by incongruent microsaccades (RT = 397.11 +/- 80.98 ms) (p = 0.029, Newman Keuls post hoc test), and lower than RTs in other trials (RT = 399.41 +/- 83.34 ms) (p = 0.03, Newman Keuls post hoc test). In the motor preparation experiment, the reaction time was affected by the direction of microsaccades during the direction cue epoch of reach trials (one-way repeated measure ANOVA [F(1,12) = 4.691, partial eta squared = 0.439, p = 0.031]; Friedman’s test p = 0.054; Fig. S1A). Although there was no reduction of RTs when microsaccades were directed toward the cued location (all p > 0.05, Newman-Keuls post hoc test, Fig. 4C), microsaccade directionality significantly affected RTs in incongruent trials. Specifically, reaction times were faster in incongruent trials (345.85 ± 76.05 ms) compared to other trials (372.85 ± 101.79 ms) (p = 0.03, Newman-Keuls post hoc test, Fig. S1A). No other significant effects were found in any other epoch, for either saccade or reach trials (one-way repeated measure ANOVAs [all F < 0.782, all partial eta squared < 0.115, all p > 0.48]; all Friedman’s test p > 0.368; Fig. S1B–D).

Detection reaction times and microsaccade directionality. (A) The effect of cue validity on median reaction times (gray lines represent single subjects) in the perceptual detection experiment. (B) The effect of microsaccade directionality on the RT gain (expressed as a difference in RT between trials with microsaccade congruent vs. incongruent, congruent vs. other and incongruent vs. other) during covert allocation of attention (direction cue epoch) in the perceptual detection experiment. Gray lines represent single subjects, and error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks mark a statistically significant difference for the repeated measures ANOVA.

A relationship between microsaccade rate and RT across subjects is present exclusively when covert attention is engaged for visual detection

The results described above show that microsaccade direction can be considered an index of the direction of covert attention allocation but not as an index of the upcoming movement direction during motor preparation. Yet, it is possible that microsaccade rate reflects an overall higher readiness to respond to external stimuli. To determine whether the overall microsaccade rate across subjects was associated with the overall reaction time in the task, we examined if the microsaccade rate (valid trials only) can predict RTs differences across subjects (Fig. 5) by fitting a linear regression model (RTs ~ microsaccade rate) in each epoch of the experiment. Interestingly, we found that only during the direction cue epoch of the perceptual detection experiment the microsaccade rate was highly predictive of the reaction time across subjects (R2 = 0.68, p = 0.022): those subjects with an overall higher microsaccade rate were also characterized by faster detection reaction times (Fig. 5). No significant effects were found in either the encoding epoch of the detection experiment (R2 = 0.026, p = 0.73), or in any of the epochs in the motor preparation experiment with reach/saccade RTs (all R2 < 0.25, all p > 0.25). Therefore, these results indicate that microsaccade rate per se does not index response preparedness, but it is related with response preparedness when covert attention is engaged in a visual perception context.

Discussion

The debate on whether attention and motor planning involve the same neural substrates and control mechanisms is still ongoing. Here we examined how microsaccades, often present during fixation, and previously shown to be associated with covert shifts of attention19,28,29,31,32,33,34, are modulated when attention vs. motor planning of different effectors is engaged. Our results show that participants shifted covert attention to the instructed side after the onset of an attentional cue, even before knowing the type of movement they would need to plan. In the subsequent motor planning phase, there was no evident microsaccade directional bias, suggesting a possible difference in how covert attention and motor planning may influence microsaccade generation. These results also raise potential questions about the actual relationship between microsaccades and attention. Recent studies have shown that shifts in covert spatial attention can occur without eliciting a microsaccade28,29,30, and that microsaccades become a less reliable indicator of attention in complex or ambiguous contexts45. When the spatial cue provides purely spatial coordinates for a motor action that is not yet known, as it happens in our motor planning experiment, microsaccades show a directional bias toward the cued position after the cue onset. During motor planning, when information about the motor action to be planned is provided, the directional bias vanishes, and as discussed earlier, microsaccade rate remains constant during this epoch. It is therefore possible that microsaccades are more indicative of an encoding of spatial coordinates rather than visuospatial attention itself.

Another important aspect to consider is the temporal occurrence of the directional microsaccade bias in the direction cue epoch of both experiments. Consistent with previous findings41, this bias occurred when microsaccade rate peaked around 200 ms after the direction cue onset, when spatial covert attention is supposed to shift2,42. However, in the motor preparation experiment, the SPM clusters started diverging about 100 ms earlier (Fig. 3). A potential explanation for this difference could be the variation in the direction cue validity between the two experiments (80% valid in the perceptual detection experiment and 100% in the motor preparation one), with the 100% valid cue likely being less ambiguous, leading to an earlier onset of the bias. A recent study45 investigated a conventional change detection task using blocks with different cue reliability and found that cues with 100% validity significantly affected the direction of microsaccades. In this study, as the reliability of the cue decreased, the bias in the directionality of microsaccades became less clear. Although both tasks in our experiments exhibited a clear directional bias, it is still possible that cue validity played a role in influencing the onset time of this bias. Future research may focus on this aspect, in order to gain a deeper understanding of how cue validity impacts microsaccades patterns.

We reported not only differences in microsaccade directionality, but we also found that the microsaccade rate was modulated differently during motor planning and covert attention allocation. Whereas microsaccade rate peaked after the attention cue onset, no peak in microsaccade rate was observed during motor planning, in both saccade and reaching trials. Moreover, we observed a difference in microsaccade rate between the two experiments around 1000 ms after the direction cue onset (Fig. 2). In the perceptual detection experiment, the rate of microsaccades gradually became completely suppressed, while in the motor preparation experiment, it stabilized around 1 microsaccades/s. Modulations of microsaccade rate based on expectations have been reported in other studies46,47, showing that oculomotor inhibition occurs before temporally expected targets, including auditory ones. However, in our study, both stimuli at the end of the direction cue epochs of the two experiments had identical temporal onset (i.e., temporal expectation was the same). Therefore, we do not think that this difference was driven by temporal expectation; rather, our data suggests two possible explanations. On one hand, it is likely that the oculomotor suppression was primarily driven by the visual nature of the upcoming stimulation, due to the visual perceptive suppression shown in relation to microsaccades48, an effect similar to the well-known saccadic suppression49,50,51,52,53,54 or the oculomotor freezing55. It may have been more efficient for participants to suppress microsaccades in anticipation of an upcoming detection of a visual stimulus compared to an upcoming discrimination of an auditory cue for motor planning. This explanation accounts for our findings, in keeping with previous studies36,37,38,40,56,57, and highlights the crucial role of using an auditory cue for the motor planning epoch to avoid biasing the microsaccade rate with the sudden onset of visual stimuli in our motor preparation experiment. On the other hand, we cannot rule out the possibility that the difference in microsaccade rate between our two experiments could be related to an inhibitory effect of the motor planning. Although early planning is possible before knowing whether to perform a reach or saccade, we believe that motor planning in this experiment primarily occurred after the motor cue onset rather than during the initial direction cue. Planning both actions during the direction cue epoch and then suppressing one is not an energy-efficient strategy, as it requires both motor planning and subsequent inhibition. Since only one movement needs to be executed, and trials when subjects performed saccades during the motor planning phase were discarded, a more efficient and parsimonious approach would be to delay motor planning until the motor cue is presented. This strategy eliminates the need for unnecessary motor suppression, streamlining the process. Further, subjects were not prompted to perform a motor action as fast as possible and were encouraged to be accurate when executing their motor action. Therefore, there was no incentive for subjects to plan distinct motor actions in parallel during the direction cue epoch. Neurophysiological evidence also supports this view, showing that “set-related cells” in the premotor and motor cortices58,59,60 become active only after a go-signal, gradually increasing their activity until movement execution.

An important consideration is that presaccadic attention, which enhances visual performance before an eye movement17,61,62,63, may have been involved during the motor preparation phase in saccade trials. However, our analysis showed comparable microsaccade patterns in saccade and reach trials. Moreover, a recent study64 suggests that psychophysical designs like ours might capture a strengthening of sensory representations rather than direct measures of presaccadic attention.

Our results also show that target detection improved when microsaccades were directed congruently toward the target. This result is consistent with other studies44 and supports the idea that microsaccades act as markers of shifts in covert spatial attention31,32,33. However, this effect was absent when motor planning was involved. Further, when the correlation between microsaccade rate and RT across subjects was examined, an inverse correlation between detection RT and microsaccade rate (faster RT when microsaccade rate was higher) was found exclusively in the perceptual detection experiment.

To conclude, the debate on whether attention and motor planning involve the same neural substrates and control mechanisms is still ongoing3,4,14,15,16,17,43,64,65,66,67,68,69. Historically, it has been suggested that spatial attention and motor planning share the same neural substrates, implying that the two systems cannot be separated4. While nowadays there is substantial evidence to contradict this theory3,14,15,16,17,43,69, the topic remains ambiguous due to several studies arguing against the idea of separating control mechanisms for action and attention65,66,67. Here we focused on microsaccades, a well-known marker of spatial attention28,31,32,33,35,70, to investigate their patterns and characteristics across two distinct experimental contexts: one focused on visual detection and the other on motor preparation. Our findings revealed distinct microsaccade patterns when attention vs. motor planning is involved. Further, the relationship between microsaccades and reaction times differed significantly in conditions involving attention and perceptual detection; a clear relationship between microsaccade rate and visual detection times was observed only in the spatial cueing phase whereas microsaccade rate during motor planning was not associated with the following reach and saccade reaction times.

Limitations of the study

The generalizability of our findings to natural conditions in which fixation is not enforced has yet to be assessed. Enforced sustained fixation on an impoverished visual stimulus (a fixation marker) is far from approaching the natural alternation of fixations and saccades. It would be important for future research to evaluate whether the findings reported here extend to these conditions. It would also be crucial to determine the extent to which the directional modulation of microsaccades observed after the cue and stimuli onset is influenced by the strong visual transient generated by flashing stimuli on a blank background, also in itself an unnatural condition. Finally, because this is a psychophysical study probing microsaccade behavior, it cannot directly address any questions about how reach/saccade planning and covert attention are linked mechanistically, but it can only show how these two processes differentially modulate microsaccades.

Materials and methods

Participants

Fourteen healthy observers participated in this study. Participants were divided into two groups: one group of seven took part in the perceptual detection experiment (4 females and 3 males; average age: 26.14 ± 2.59 years; age range: 22–30 years); 6 participants from the first experiment and a seventh one participated in the motor preparation experiment (4 females and 3 males; average age: 26.29 ± 2.37 years; age range: 23–30 years). In both experiments participants were naive about the purpose of the study and were compensated for their participation. All procedures were approved by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. The experimenter reviewed and explained the material in the consent form to the participant before conducting the experiment. The form was signed only after the participant fully understood the material and voluntarily agreed to take part in the study. Consent was obtained from all participants in the study. To qualify, participants had to possess at least 20/20 acuity in both eyes (after correction through contact lenses if needed), as assessed by correct identification of at least 75% of the optotypes in the 20/20 line of a standard Snellen test.

Apparatus

In both experiments, stimuli were displayed on an LCD monitor (ASUS ROG SWIFT PG259QN) at a refresh rate of 360 Hz and spatial resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. Participants performed both experiments 1 and 2 binocularly. A dental-imprint bite bar and a headrest were used to minimize head movements. The movements of the right eye were measured by means of a custom-made digital Dual-Purkinje Image (dDPI) eye-tracker, a system with arcminute resolution39. The eye position signals were sampled at 340 Hz. Stimuli were rendered by means of EyeRIS, a custom-developed system71.

In both experiments, a custom-made keyboard featuring three equally spaced 4 × 4 cm buttons was placed underneath the experimental table. The central button was located 13 cm away from both the left and right buttons and served to start trials, while lateral buttons were used only in the motor preparation experiment as reaching targets.

Experimental design

Every session started with the initial setup of the bite bar. A magnetized helmet was used to position participant’s head. Both experiments were performed in blocks of 100 trials. Participants underwent as many trial batteries as necessary to collect at least 100 microsaccades per condition (valid/invalid for the perceptual detection experiment and reach/saccade for motor preparation experiment; total number of trials in the perceptual detection experiment: 15,700, total number of trials in the motor preparation experiment: 8,700; total number of trials among the two experiments: 24,400). Before the start of each block a two-phases calibration procedure was performed. During the first phase, participants sequentially fixated on each of the nine points of a 3-by-3 grid. In the second phase, observers refined the pixel-to-pixel mapping, given by the automatic calibration. They fixated again on each of the nine points while the location of the line of sight was displayed in real-time on the screen. Participants pressed a button on a keyboard set under the experimental table to correct the predicted gaze location, shifting the real-time display to align with the grid point for each fixation, if necessary. These corrections were then incorporated into the transformation of the gaze position as well. This dual-step calibration procedure allows more accurate localization of gaze position than standard single-step procedures. The manual calibration procedure was repeated for the central fixation marker before each trial to compensate for possible drifts in the electronics as well as unpreventable head movements.

In the perceptual detection experiment (Fig. 1A) participants initiated each trial (grouped in blocks of 100) with a button-press, which triggered the simultaneous appearance of a central fixation point (black square, 10’x10’) and two differently colored circles (1° diameter) at 5° to the right and to the left of the fixation point (encoding epoch, 500 ms). In each trial, the circles were assigned with two colors randomly drawn from a set of four: blue (RGB: 21, 165, 234), orange (RGB: 234, 74, 21), green (RGB: 133, 194, 18) and purple (RGB: 197, 21, 234). Participants were instructed to maintain fixation on the fixation point for the entire duration of the task. Then, the circles turned gray while the central square took on one of the two colors, thereby serving as a cue for directing covert attention to the direction of the target that matched the color previously presented in the peripheral circle (direction cue epoch, 700–1000 ms). A black low-contrast target (go signal) then appeared in one of the two circles, and participants had to respond by releasing the button as soon as they detected the target. The cue was valid (the target appeared in the cued circle) in 80% of trials and invalid (the target appeared in the opposite circle from the cued one) in the remaining 20%. We opted for a simple design with a button release to focus solely on detection reaction times, which are a good indicator of covert attention. Using a simple button-release design in this context has also two important advantages as it reduces motor planning and cognitive load, which may influence microsaccade dynamics differently between the two experiments, to a minimum. The contrast of the target was set for each participant using a staircase procedure, resulting in a low-contrast level correctly perceivable a 90% of trials based on the acceptable range of reaction times (higher than 100 ms or lower than l000 ms43.

In the motor preparation experiment (Fig. 1C) the first two epochs (encoding and direction cue) were identical to those in the perceptual detection experiment. After the direction cue epoch, a 50 ms auditory cue instructed participants to plan one of two actions: a low tone signaled a saccade trial (50% of the trials), and a high tone a reaching one (the other 50% of the trials). To isolate the processes behind cue direction encoding and covert attention from those controlling for motor preparation, and to determine the influence of the effector type on microsaccades, we separated the directional cue encoding and motor planning into two different epochs. In reaching trials, participants had to plan a goal-oriented motor action towards the cued button on the board; in saccade trials the motor action was a saccade towards the cued displayed target (motor planning epoch, 700–1000 ms). In reaching trials, participants were instructed to fixate on the central fixation point throughout the trial, including during movement execution. Reaching trials in which a saccade (> 30’ deg) occurred at any point during the trial (including movement execution) were discarded from the analyses. Then a second 50 ms auditory cue served as a go signal to execute the planned motor action.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Analysis of oculomotor data

Classification of eye movements was performed automatically and then validated by trained laboratory personnel. We used a MATLAB custom made toolbox for saccade detection. The algorithm first applies a first order Savitzky-Golay (SG) filter to the raw traces, instantaneous speed is then computed, and events exceeding a velocity threshold of 3 deg/s are identified as saccades. Saccades with amplitudes between 5’ and 30’ were classified as microsaccades (see Fig. 1D). Consecutive events occurring within 15 ms are merged into a single saccade, effectively accounting for potential post-saccadic overshoots72. Microsaccade and saccade onset was defined as the moment when a gaze shift reached a speed exceeding 3 deg/sec. Trials with no microsaccades were discarded (20.27% of the total trials), except for the microsaccade rate calculation. Trials were discarded if blinks or large saccades occurred at any time between 50 ms before the trial onset to the end of the trial and/or microsaccades starting/ending position was outside 1° radius from fixation point (37.21% of the total trials).

Analysis of microsaccade rate

Microsaccade rate was calculated in both experiments separately for each participant and smoothed using a sliding window of 100 ms with a sample rate of 1ms. The number of microsaccades per second was divided by the participant’s total number of trials with and without microsaccades and further divided by the length of the sliding window. One-way statistical parametric mapping analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPM1d73 Matlab package was applied on each experimental epoch to statistically compare the microsaccade rate of the two experiments (with factor Experiment, 2 levels, perceptual detection experiment and MP experiment) and of the reach and saccade trials (with factor Condition, 2 levels, reach and saccade). SPM1d ANOVA conducts a one-way ANOVA at each time point and determines critical F-threshold values to control the family-wise error rate across the entire series. Regions where the F-statistic exceeds this threshold are identified as “suprathreshold clusters”. By using Random Field Theory, this method effectively addresses the multiple comparisons problem, preserving statistical power while minimizing false positives. In these clusters, both the F-value height and temporal extent contribute to statistical significance (more information are available on the website: https://spm1d.org/index.html).

Analysis of microsaccade directionality

To analyze the directional probability of microsaccades over time, microsaccades were categorized into three groups: ‘Toward’ (aligned with the cued direction), ‘Away’ (opposite to the cued direction), and ‘Other’ (microsaccades oriented vertically, either up or down). The categorization was structured so that each category spanned 120° of the visual circular space. We also analyzed microsaccade directionality over time in the direction cue epoch using a more conservative categorization of horizontal microsaccades (see Fig. S2). Probability distributions were calculated separately for each participant and smoothed using a sliding window of 200 ms with a 20 ms step. We compared the distributions of microsaccades (Toward vs. Away, Toward vs. Other, Away vs. Other) using one-way statistical parametric mapping ANOVA with SPM1d package73, with factor Group.

Analysis of reaction times

In the perceptual detection experiment, reaction times were defined as the interval between the go signal and the button release, while in motor preparation one, as the interval between the go signal and the movement onset: button release (reaction time) or saccade onset (saccadic reaction times).

We always used medians of the reaction times. In the perceptual detection experiment, statistical comparisons between median RT of valid and invalid trials were conducted using one-way repeated measures ANOVA and one-way Friedman’s test with factor trial type (2 levels, valid, invalid). We assessed the influence of the congruence of microsaccade directionality on the reaction time with a one-way repeated measures ANOVA and one-way Friedman’s test with factor Congruence (3 levels, Congruent, Incongruent, Other). In both experiments, we selected the first microsaccade in the time window of the peak of ‘Toward’ microsaccades. We also divided trials according to the first microsaccade into ‘Congruent’, ‘Incongruent’ or ‘Other’ based on the congruence of the microsaccade direction with the side of the subsequent target appearance. In ‘Congruent’ trials the direction of the first microsaccade was the same as the side of the target appearance, while in ‘Incongruent’ trials the first microsaccade was directed opposite to the subsequent target appearance. ‘Other’ trials were trials where the first microsaccade was vertical. We analyzed the effect of the microsaccade directionality on reaction times during the movement planning of the motor preparation experiment with multiple one-way repeated measures ANOVA and one-way Friedman’s test with factors Congruence (3 levels, Congruent, Incongruent, Other). We used Newman Keuls post hoc tests for multiple comparisons. We also repeated this analysis using the first microsaccade during the direction cue epoch for both experiments, rather than the first microsaccade after the onset of the directional bias when the likelihood of microsaccades pointing toward the cue was highest. In this case, the results showed no significant effect (see supplementary materials).

To investigate whether the rate of microsaccades could be predictive of RTs we fit a linear regression model (RTs or SRTs ~ microsaccade rate) using the average microsaccade rate in each epoch for each participant.

Data availability

All data are available upon reasonable request due to logistical reasons including ongoing work and file sizes. This study used standard, custom-built MATLAB programmed scripts that are available from the lead contact upon request. Please contact Martina Poletti at martina_poletti@urmc.rochester.edu.

Change history

07 July 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incomplete, where a project funding number was omitted. It now reads: “Authors wish to thank Claire Corbeaux for verifying the manuscript’s English language proficiency.The authors also thank AP lab members of University of Rochester for helpful feedback and comments. This work was supported by EU Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101086206 - PLACES; NIH R01 EY029788 and NIH P30 EY001319; Progetto “Multisensory integration of locomotion-related visual and somatomotor signals- MulWALK", codice proposta: 2022BK2NPS_001 - CUP: J53D23010900006 Finanziato dall'Unione Europea - NextGenerationEU a valere sul Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR) – Missione 4 Istruzione e ricerca – Componente 2 Dalla ricerca all’impresa - Investimento 1.1, Avviso Prin2022 indetto con DD N. 104 del 2/2/2022.”

References

Posner, M. I. Orienting of attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 32, 3–25 (1980).

Carrasco, M. Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vis. Res. 51, 1484–1525 (2011).

Kowler, E., Anderson, E., Dosher, B. & Blaser, E. The role of attention in the programming of saccades. Vis. Res. 35, 1897–1916 (1995).

Rizzolatti, G., Riggio, L., Dascola, I. & Umiltá, C. Reorienting attention across the horizontal and vertical meridians: Evidence in favor of a premotor theory of attention. Neuropsychologia 25, 31–40 (1987).

Bollimunta, A., Bogadhi, A. R. & Krauzlis, R. J. Comparing frontal eye field and superior colliculus contributions to covert spatial attention. Nat. Commun. 9, 3553 (2018).

Krauzlis, R. J., Lovejoy, L. P. & Zénon, A. Superior colliculus and visual spatial attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 36, 165–182 (2013).

Galletti, C., Gamberini, M. & Fattori, P. The posterior parietal area V6A: An attentionally-modulated visuomotor region involved in the control of reach-to-grasp action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 141, 104823 (2022).

Galletti, C. et al. Covert shift of attention modulates the ongoing neural activity in a reaching area of the macaque dorsomedial visual stream. PLoS One 5, e15078 (2010).

Caspari, N., Arsenault, J. T., Vandenberghe, R. & Vanduffel, W. Functional similarity of medial superior parietal areas for shift-selective attention signals in humans and monkeys. Cereb. Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx114 (2018).

Caspari, N. et al. Covert shifts of spatial attention in the macaque monkey. J. Neurosci. 35, 7695–7714 (2015).

Ciavarro, M. et al. rTMS of medial parieto-occipital cortex interferes with attentional reorienting during attention and reaching tasks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00409 (2013).

Vandenberghe, R., Gitelman, D. R., Parrish, T. B. & Mesulam, M. M. Location- or feature-based targeting of peripheral attention. Neuroimage 14, 37–47 (2001).

Kelley, T. A., Serences, J. T., Giesbrecht, B. & Yantis, S. Cortical mechanisms for shifting and holding visuospatial attention. Cereb. Cortex 18, 114–125 (2008).

Messinger, A., Cirillo, R., Wise, S. P. & Genovesio, A. Separable neuronal contributions to covertly attended locations and movement goals in macaque frontal cortex. Sci. Adv. 7 (2021).

Khan, A. Z., Blohm, G., Pisella, L. & Munoz, D. P. Saccade execution suppresses discrimination at distractor locations rather than enhancing the saccade goal location. Eur. J. Neurosci. 41, 1624–1634 (2015).

Montagnini, A. & Castet, E. Spatiotemporal dynamics of visual attention during saccade preparation: Independence and coupling between attention and movement planning. J. Vis. 7, 8 (2007).

Li, H. H., Hanning, N. M. & Carrasco, M. To look or not to look: Dissociating presaccadic and covert spatial attention. Trends Neurosci. 44, 669–686 (2021).

Lhermitte, F. Utilization behaviour’ and its relation to lesions of the frontal lobes. Brain 106(Pt 2), 237–255 (1983).

Bowers, N. R. & Poletti, M. Microsaccades during reading. PLoS One 12, e0185180 (2017).

Kowler, E. & Anton, S. Reading twisted text: Implications for the role of saccades. Vis. Res. 27, 45–60 (1987).

Rima, S. & Schmid, M. C. Reading specific small saccades predict individual phonemic awareness and reading speed. Front. Neurosci. 15 (2021).

Ko, H., Poletti, M. & Rucci, M. Microsaccades precisely relocate gaze in a high visual acuity task. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1549–1553 (2010).

Shelchkova, N., Tang, C. & Poletti, M. Task-driven visual exploration at the foveal scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 5811–5818 (2019).

Intoy, J. & Rucci, M. Finely tuned eye movements enhance visual acuity. Nat. Commun. 11, 795 (2020).

Poletti, M., Listorti, C. & Rucci, M. Microscopic eye movements compensate for nonhomogeneous vision within the fovea. Curr. Biol. 23, 1691–1695 (2013).

Poletti, M. & Rucci, M. A compact field guide to the study of microsaccades: Challenges and functions. Vis. Res. 118, 83–97 (2016).

Poletti, M. An eye for detail: Eye movements and attention at the foveal scale. Vis. Res. 211, 108277 (2023).

Liu, B., Nobre, A. C. & van Ede, F. Functional but not obligatory link between microsaccades and neural modulation by covert spatial attention. Nat. Commun. 13, 3503 (2022).

Yu, G., Herman, J. P., Katz, L. N. & Krauzlis, R. J. Microsaccades as a marker not a cause for attention-related modulation. Elife 11 (2022).

Poletti, M., Rucci, M. & Carrasco, M. Selective attention within the foveola. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1413–1417 (2017).

Engbert, R. & Kliegl, R. Microsaccades uncover the orientation of covert attention. Vis. Res. 43, 1035–1045 (2003).

Hafed, Z. M. & Clark, J. J. Microsaccades as an overt measure of covert attention shifts. Vis. Res. 42, 2533–2545 (2002).

Lowet, E. et al. Enhanced neural processing by covert attention only during microsaccades directed toward the attended stimulus. Neuron 99, 207–214 (2018).

Yuval-Greenberg, S., Merriam, E. P. & Heeger, D. J. Spontaneous microsaccades reflect shifts in covert attention. J. Neurosci. 34, 13693–13700 (2014).

van Ede, F., Chekroud, S. R. & Nobre, A. C. Human gaze tracks attentional focusing in memorized visual space. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 462–470 (2019).

Betta, E. & Turatto, M. Are you ready? I can tell by looking at your microsaccades. Neuroreport 17, 1001–1004 (2006).

Krasovskaya, S., Kristjánsson, Á. & MacInnes, W. J. Microsaccade rate activity during the preparation of pro- and antisaccades. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 85, 2257–2276 (2023).

Watanabe, M., Matsuo, Y., Zha, L., Munoz, D. P. & Kobayashi, Y. Fixational saccades reflect volitional action preparation. J. Neurophysiol. 110, 522–535 (2013).

Wu, R. J. et al. High-resolution eye-tracking via digital imaging of purkinje reflections. J. Vis. 23, 4 (2023).

Laubrock, J., Engbert, R. & Kliegl, R. Microsaccade dynamics during covert attention. Vis. Res. 45, 721–730 (2005).

Laubrock, J., Kliegl, R., Rolfs, M. & Engbert, R. When do microsaccades follow Spatial attention? Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 72, 683–694 (2010).

Anton-Erxleben, K. & Carrasco, M. Attentional enhancement of Spatial resolution: Linking behavioural and neurophysiological evidence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 188–200 (2013).

Breveglieri, R. et al. Modulation of reaching by spatial attention. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 18 (2024).

Laubrock, J., Engbert, R., Rolfs, M. & Kliegl, R. Microsaccades are an index of covert attention. Psychol. Sci. 18, 364–366 (2007).

Willett, S. M. & Mayo, J. P. Microsaccades are directed toward the midpoint between targets in a variably cued attention task. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (2023).

Amit, R., Abeles, D., Carrasco, M. & Yuval-Greenberg, S. Oculomotor Inhibition reflects Temporal expectations. Neuroimage 184, 279–292 (2019).

Abeles, D., Amit, R., Tal-Perry, N., Carrasco, M. & Yuval-Greenberg, S. Oculomotor Inhibition precedes temporally expected auditory targets. Nat. Commun. 11, 3524 (2020).

Intoy, J., Cox, M. A. & Rucci, M. Control and coordination of fixational eye movements in the Snellen acuity test. J. Vis. 19, 145a (2019).

Burr, D. C., Morrone, M. C. & Ross, J. Selective suppression of the magnocellular visual pathway during saccadic eye movements. Nature 371, 511–513 (1994).

Burr, D. C., Holt, J., Johnstone, J. R. & Ross, J. Selective depression of motion sensitivity during saccades. J. Physiol. 333, 1–15 (1982).

Ross, J., Morrone, M. C., Goldberg, M. E. & Burr, D. C. Changes in visual perception at the time of saccades. Trends Neurosci. 24, 113–121 (2001).

Diamond, M. R., Ross, J. & Morrone, M. C. Extraretinal control of saccadic suppression. J. Neurosci. 20, 3449–3455 (2000).

Latour, P. L. Evidence of internal clocks in the human operator. Acta Psychol. 27, 341–348 (1967).

Volkmann, F. C., Riggs, L. A., White, K. D. & Moore, R. K. Contrast sensitivity during saccadic eye movements. Vis. Res. 18, 1193–1199 (1978).

White, A. L., Moreland, J. C. & Rolfs, M. Oculomotor freezing indicates conscious detection free of decision bias. J. Neurophysiol. 127, 571–585 (2022).

Bonetti, F., Valsecchi, M. & Turatto, M. Microsaccades Inhibition triggered by a repetitive visual distractor is not subject to habituation: Implications for the programming of reflexive saccades. Cortex 131, 251–264 (2020).

Rolfs, M., Laubrock, J. & Kliegl, R. Shortening and prolongation of saccade latencies following microsaccades. Exp. Brain Res. 169, 369–376 (2006).

Affan, R. O. et al. Ramping dynamics in the frontal cortex unfold over multiple timescales during motor planning. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.05.578819 (2024).

Hanes, D. P. & Schall, J. D. Neural control of voluntary movement initiation. Science 274, 427–430 (1996).

S P Wise & K H Mauritz. Set-related neuronal activity in the premotor cortex of rhesus monkeys: effects of changes in motor set. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 223, 331–354 (1985).

Rolfs, M. & Carrasco, M. Rapid simultaneous enhancement of visual sensitivity and perceived contrast during saccade Preparation. J. Neurosci. 32, 13744–13752 (2012).

Li, H. H., Pan, J. & Carrasco, M. Different computations underlie overt presaccadic and covert spatial attention. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1418–1431 (2021).

Deubel, H. & Schneider, W. X. Saccade target selection and object recognition: Evidence for a common attentional mechanism. Vis. Res. 36, 1827–1837 (1996).

Huber-Huber, C., Steininger, J., Grüner, M. & Ansorge, U. Psychophysical dual‐task setups do not measure pre‐saccadic attention but saccade‐related strengthening of sensory representations. Psychophysiology 58 (2021).

Sheliga, B. M., Riggio, L. & Rizzolatti, G. Spatial attention and eye movements. Exp. Brain Res. 105 (1995).

Tipper, S. P., Lortie, C. & Baylis, G. C. Selective reaching: Evidence for action-centered attention. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 18, 891–905 (1992).

Tucker, M. & Ellis, R. On the relations between seen objects and components of potential actions. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 24, 830–846 (1998).

Brandolani, R., Galletti, C., Fattori, P., Breveglieri, R. & Poletti, M. Time course of microsaccades directionality during an endogenous attention task. J. Vis. 24, 381 (2024).

Breveglieri, R. et al. Role of the medial posterior parietal cortex in orchestrating attention and reaching. J. Neurosci. 45, e0659242024 (2025).

de Vries, E. & van Ede, F. Microsaccades track location-based object rehearsal in visual working memory. eNeuro 11 (2024).

Santini, F., Redner, G., Iovin, R. & Rucci, M. EyeRIS: A general-purpose system for eye-movement-contingent display control. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 350–364 (2007).

Deubel, H. & Bridgeman, B. Perceptual consequences of ocular lens overshoot during saccadic eye movements. Vis. Res. 35, 2897–2902 (1995).

Pataky, T. C., Vanrenterghem, J. & Robinson, M. A. Zero- vs. one-dimensional, parametric vs. non-parametric, and confidence interval vs. hypothesis testing procedures in one-dimensional Biomechanical trajectory analysis. J. Biomech. 48, 1277–1285 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Claire Corbeaux for verifying the manuscript’s English language proficiency. The authors also thank AP lab members of University of Rochester for helpful feedback and comments. This work was supported by EU Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101086206 - PLACES; NIH R01 EY029788 and NIH P30 EY001319; Progetto “Multisensory integration of locomotion-related visual and somatomotor signals- MulWALK”, codice proposta: 2022BK2NPS_001 - CUP: J53D23010900006 Finanziato dall’Unione Europea - NextGenerationEU a valere sul Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR) – Missione 4 Istruzione e ricerca – Componente 2 Dalla ricerca all’impresa - Investimento 1.1, Avviso Prin2022 indetto con DD N. 104 del 2/2/2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ri.B., Ro.B., C.G. and M.P. designed research; Ri.B. performed research; Ri.B. and M.P. analyzed data; Ri.B. and Ro.B wrote the first draft of the paper; P.F. and M.P. acquired funding; all authors revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the Research Subjects Review Board at the University of Rochester and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brandolani, R., Galletti, C., Fattori, P. et al. Distinct modulation of microsaccades in motor planning and covert attention. Sci Rep 15, 19580 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03000-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03000-z