Abstract

Urban land density analysis is central to urban expansion research. Different mathematical models have unique strengths and limitations in exploring land density, yet there is little systematic comparison between them. This paper addresses this gap by analyzing land use data from 2000 to 2020 in Zhengzhou City, using two models: the Gaussian function and the inverse S function. It quantifies changes in land density and expansion trends, while also comparing the models’ applicability across expansion directions. The findings are as follows: (1) Both models show strong overall fitting abilities. However, the Gaussian model offers a more detailed understanding of urban expansion due to its multi-dimensional parameter settings. (2) In determining urban boundaries and zoning, the Gaussian model is more convenient, reflecting wave-like diffusion patterns that better match actual urban growth trends. (3) In terms of expansion direction, the urban compactness index reveals spatial heterogeneity. The inverse S function performs well, showing a clear compactness trend, while the Gaussian function’s fitting degree is weaker, with less distinct compactness patterns. Overall, these two models complement each other in analyzing urban land density, unveiling the form and mechanisms of urban expansion, and providing valuable insights for sustainable urban development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the acceleration of global urbanization, urban expansion has become a key focus for geography, urban planning, environmental science, and related fields. In 2024, the “Government Work Report” highlighted that the urbanization rate of the resident population in China had reached 66.2%, achieving the goal set in the “14th Five-Year Plan” ahead of schedule. It is projected that the urbanization rate will reach 70% by 2030, reflecting significant progress in the urbanization process1. According to the United Nations’ World Urbanization Prospects report, the global urbanization rate stood at only 30% in 1950, which has increased to 57% by 2023 and is projected to reach 68% by 20502. Urbanization is typically accompanied by the continuous expansion of urban construction land, leading to substantial changes in urban land density, this process that also triggers complex environmental changes, social transformations and economic challenges3. While traditional urban geography mainly focuses on the study of macro laws such as urbanization, town systems, and spatial morphology, the drastic increase in the complexity of the urban system makes it difficult to meet the demand for traditional empirical qualitative analysis. Therefore, the application of new technical methods to analyze trends in urban expansion, particularly in relation to changes in urban land density, has become a key topic in urban studies.

Urban expansion is a primary means through which humans continuously utilize land, a process that has persisted since the formation of cities4. In recent years, as research on urban expansion has deepened, the methods employed have become increasingly diverse5, typically focusing on quantifying urban form and tracing its dynamic growth6. For example, studies have examined urban land density functions across diverse regional contexts, with cases spanning Berlin, Rome, Madrid, and other globally representative cities7. With the robust support of remote sensing technology and geographic information systems, researchers can capture subtle changes in urban land use and conduct in-depth analyses of key urban expansion characteristics, such as scale, speed, and direction8. For example, landscape indicators, sprawl patterns, sprawl rates, and eight-direction sector zoning are used to quantify the spatial and temporal patterns of sprawl in the six major cities in the Yangtze River Delta and to verify the applicability of diffusion-coalescence theory (DCT) to different urban development patterns9. In addition, model construction plays a vital role in uncovering the internal mechanisms of urban expansion. Using tools like the geographical detector10,11, geographically weighted regression model12, gray correlation model13, and random forest model14, studies have confirmed that economic development, population growth, and urbanization are the primary drivers of urban expansion15. Large cities, characterized by dense populations and frequent changes in land use, are focal points for urban expansion research16. Consequently, in-depth studies of urban expansion trends in large cities provide valuable insights into general urban expansion laws and phenomena, offering more accurate guidance for urban planning and management.

In recent years, research on urban land density has gained more attention than population density in exploring urban expansion dynamics17. Some studies have found that new urban land density decreases exponentially from the city center to the periphery over time18. The bilinear model has been shown to fit the distance decay characteristics of urban land density across different gradients, highlighting the differences between inner city and suburban land density changes19. Notably, the inverse S function and Gaussian function models, developed by Jiao and Yang, are representative of urban land density studies, offering new perspectives on the spatial processes of urban expansion and demonstrating strong potential in urban planning research. In 2015, Jiao et al. found that as cities expand20, urban land density extends from the center outward, exhibiting a distinctive “anti-S rule”21. They proposed an anti-S function to accurately define the boundaries of the main urban area, subdividing it into four key zones: the urban core, inner urban area, suburbs, and fringe areas22. By analyzing model parameters, they revealed the compactness and expansion trends of each zone, providing new methods for understanding the physical spatial processes of urban development and offering strong theoretical support for sustainable urban growth.

Subsequent studies using the inverse S function model have analyzed the spatial distribution characteristics of urban land density across different spatial scales, such as global, national (China’s provinces), regional (The Huaihe River Basin), and metropolitan (Zhengzhou)23. These studies dynamically track urban expansion24 trajectories and reveal that social and economic activities are more compact than physical spaces7. They also confirm that spatial expansion often outpaces population growth, leading to a transition from compact to dispersed urban forms25. This research provides both theoretical and empirical support for understanding the spatial structure’s evolution during urbanization. In 2022, Yang et al. introduced a novel perspective by using urban land density diffusion patterns to examine the physical space of urban expansion26. By leveraging the Gaussian model, they successfully simulated the year-on-year diffusion trend of urban land density and analyzed the speed and direction of urban expansion, as well as interactions between different regions. This methodology offers insights into the spatial relationships between urban zones. In a related study, Gui et al. employed the Gaussian function to assess the relationship between terrain conditions and urban sprawl27, while Guo et al. used it to simulate spatial distributions of urban land demand. Their research predicts the macro form of urban development using geographical micro-process models28. Li et al. applied the Gaussian function to analyze the spatial correlation between the gradient intensity of expansion in mountainous towns and land subsidence rates, revealing connections between urban expansion and geological risks29. Yang et al. further simulated patterns of human activity across 234 cities in China, using the Gaussian function to forecast future changes in human activity intensity. Both models—the inverse S function and the Gaussian function30—offer unique advantages for studying urban expansion, but further research is needed to determine which model more accurately captures the characteristics and heterogeneity of urban spatial expansion. This research can provide a more robust scientific basis for urban planning and management.

According to the 2022 “Statistical Yearbook of Urban Construction,” Zhengzhou’s urban population reached 7.109 million, and its urbanization rate was 79.4%. That same year, the city’s central built-up area covered 774.32 square kilometers, ranking 15th nationwide. From 2000 to 2020, the built-up area increased by approximately 703 square kilometers, highlighting the city’s rapid development. Zhengzhou’s growth is supported by the “eastward expansion, westward expansion, southward extension, and northward connection” strategy, which has spurred not only spatial growth in all directions, but also comprehensive economic, social, and cultural development. By observing the spatial and temporal changes in land use in Zhengzhou from 2000 to 2020, it is found that the development of the built-up area of the city exhibits significant monocentric radial expansion characteristics, i.e., a balanced and stable spatial expansion trend with the core urban area as the base to the surroundings. As a national central city and a core transportation hub in central China, Zhengzhou has both typical mega-city scale characteristics and a distinctive monocentric spatial structure, which makes it an ideal case for exploring the trend of urban expansion and the laws of spatial evolution.

The inverse S function model and the Gaussian function model have not yet been systematically compared in studies of urban land density to analyze their respective focal points and comparative advantages. Therefore, building upon the analytical framework for urban land density established by Jiao Limin’s research team and Yang Jianxin et al., this study selects Zhengzhou City as the research subject. Leveraging the similarity between the inverse S function model and the Gaussian function model, and adopting the integrated research perspective of “fitting curve-urban zoning-compactness,” this work aims to achieve the following objectives: (1) determine which model more accurately reflects the city’s real urban expansion trends, (2) assess the models’ efficacy in defining urban areas and expressing parameters, and (3) compare compactness indicators across different spatial divisions. Using two mathematical models to simulate the spatial and temporal change characteristics in the process of urban expansion, we analyze the advantages and limitations of both in the study and use them to reveal the spatial and temporal dynamic change laws of Zhengzhou city’s rapid expansion. This will provide urban planners with various analytical tools to help them gain insights into the complex evolution of the urban system, offer detailed guidance for planning decision-making, and push forward the rapid development of the science of urban planning.

Data sources and preprocessing

Overview of the study area

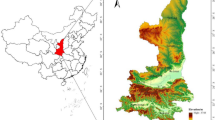

Zhengzhou is a prefecture-level city, provincial capital, and megacity in Henan Province. As a key city in China’s “13th Five-Year Plan” for central region development, it lies in north-central Henan between 112°42′ and 114°14′E and 34°16′ and 34°58′N, covering 7,567 square kilometers. A temperate continental monsoon climate prevails in the area, with high topography in the southwest and low terrain in the northeast. Zhengzhou has seen substantial, orderly urban expansion, following a pattern of gradual growth from the city center outward31. As of 2023, Zhengzhou has 13.008 million population, with an urbanization rate of 80%. The urban area spans 1,128.78 square kilometers, of which the built-up area is 933.38 square kilometers, accounting for 82.7%. The built-up area increased by 733.18 square kilometers from 2000 to 2020, with growth between 2010 and 2020 outpacing the previous decade by 2.5 times. Studying Zhengzhou’s urban expansion offers valuable insights for balancing development and environmental resources, promoting sustainable urban growth (Fig. 1).

Overview of the study area (Approval number: [GS(2019)1822]). The Base map are from “Geospatial Data Cloud”, https://www.gscloud.cn. Created by ArcGIS 10.8 software, http://desktop.arcgis.com/cn/).

Data source

The land use data (30 m resolution) from 2000 to 2020 used in this study come from the China Land Cover Dataset released by Wuhan University, based on Landsat data from Google Earth Engine. These data classify land into categories like farmland, forest, grassland, water, impervious surface, and wetland32. Other data sources include the Urban Expansion Atlas and Zhengzhou Statistical Bureau, while administrative boundary data were obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud.

Pretreatment

Following past research, the central business district is defined as the city center20,33. As a typical monocentric city, Zhengzhou is in sharp contrast to multi-centered cities such as Wuhan and Hangzhou. Land use data from 2000 to 2020 show that the built-up area of Zhengzhou exhibits an obvious monocentric radial expansion pattern, and its urban spatial growth is mainly centered around the core urban area, which continues to expand outward in a stable manner. Therefore, in this study, based on the city center coordinates from the Urban Expansion Atlas, 26 concentric rings were drawn using the circle layer method34, with each ring having a width of 1 km35. The setup mainly refers to the buffer ring setup standards of Jiao et al. for 28 provincial capitals and municipalities in China, and 26 concentric buffer rings with 1-kilometer intervals were finally adopted as the analysis unit through the preliminary experimental verification20. These concentric circles extend outward to cover the entire functional urban area and outer ring road33. The urban land density was calculated as the ratio of built-up area in each ring to the total land area20,36. Similarly, the density of newly developed land was calculated by assessing the increase in impervious surfaces26. Large water bodies were excluded from these calculations as they are not used for urban development.

Research method

Construction of urban expansion model based on inverse S function

Anti-S function model

The inverse S function is used to accurately model the spatial variation of urban land density20. The calculation formula is as follows:

where f (r) is the urban land density, r is the distance from the city center, exp is the Euler number, a, c and d are constants, a represents the slope of the curve in the middle section, and its value range is usually between 2 and 6, c is the asymptote, and the two asymptotes of the fitting curve are f = 1 and f = c, d is the main urban area, which is the approximate boundary of the urban fringe area.

Nonlinear least squares optimization implemented in Origin software was employed for scatterplot generation and regression analysis. The platform’s integrated visualization tools, coupled with robust regression algorithms and detailed statistical outputs (including parameter estimates, adjusted R², and residual diagnostics), ensured methodological consistency across both conventional curve fitting and Gaussian distribution modeling.

Partitioning based on inverse S function model

Previous studies have used 50% as the threshold to differentiate between the internal and external land density of a city33,37. The zoning scheme of the inverse S function model is based on the main urban area division proposed by Jiao et al., which follows the trend of urban land density changes across concentric circles. The zoning criteria are characterized by the first and second derivatives of the inverse S function. The first derivative describes the rate of decline in urban land density, while the second derivative captures changes in that decline rate20. This method provides deeper insights into the “anti-S rule” of urban land density from the city center to the periphery.

The trend of the urban land density decline rate (i.e., the first derivative) increases from the center to the periphery, reaching a maximum before decreasing to a minimum. The location with the greatest rate of change serves as the basis for dividing the inner city and the suburbs. The second derivative, which tracks the change rate of the density decline, has two extreme points, and the locations with the largest attenuation rate changes are used to divide the core area, inner urban area, suburbs, and marginal areas (Fig. 2). In this process, the derivatives are calculated using functional parameters (a, c, d) combined with code operations in MATLAB R2018a software. Leveraging its efficient numerical computation capabilities and robust visualization support, MATLAB R2018a enable us to quickly and accurately determine the boundary values for each urban area, thereby segmenting the urban area into four concentric zones: the urban core area (0 < r < r1), inner urban area (r1 < r < r0), suburban area (r0 < r < r2), and the urban fringe (r2 < r < d).

Construction of urban expansion process model based on Gaussian function

Gaussian function model

The Gaussian function is applied to model the spatial variation of new urban land density26, and its calculation formula is as follows:

where den (r) is the density of new urban land, r is the distance from the city center, exp is the Euler number, a, b and c are the amplitude, mean and standard deviation parameters, respectively. Parameter a represents the peak height of the curve, parameter b represents the peak position of the curve, parameter c represents the width of the curve, and the radius of the main urban area can be determined by parameter b + 2c.

Partitioning based on Gaussian function model

The zoning scheme for the Gaussian function is based on the new urban land density variation across concentric circles, as proposed by Yang et al. The first derivative of the Gaussian function fitting curve features two extreme points and a zero point20, indicating that the new urban land density curve has two inflection points and one peak. The coordinate values of these points are derived from the functional parameters (a, b, c). The peak occurs at a distance from the city center equal to b, and the inflection points are at distances of b - c and b + c from the center (Fig. 3). The outer boundary is located at a distance of b + 2c, forming the final zoning scheme26.

Based on these feature points, the city is divided into four concentric zones: core area, inner city, suburbs, and urban fringe. The core area is within the b - c concentric ring, the inner city spans the b - c to b rings, the suburban area covers the b to b + c rings, and the urban fringe extends from b + c to b + 2c. These zones define the full extent of the main urban area, with a total radius of b + 2c.

Measure the compactness of the city

Compactness index based on inverse S function

Some studies describe urban compactness by analyzing the shape of the city38. In urban land density studies, the steepest slope of the inverse S function curve, which corresponds to the urban and suburban areas, is selected to reflect overall land density, and the Cp index is derived to characterize city compactness20. The calculation formula is:

where Cp is the compactness index of the city. The smaller the Cp value is, the more compact the space is, and vice versa. r1 and r2 are the derivative parameters of the inverse S function, respectively. The meaning of a and d parameters is the same as above.

Compactness index based on Gaussian function

From an intuitive standpoint, a densely urbanized area should have a relatively narrow inner city and suburban zone39, where new urbanized land is concentrated, marking the most intense urban expansion area40,41. Gaussian function studies on new urban land density, the ratio of the width of the urban and suburban areas to the main urban radius is used to represent urban expansion compactness26. The calculation formula is:

where k is the compactness of urban expansion. The smaller the k value is, the higher the space compactness is, and vice versa. b and c are the functional parameters of Gaussian function respectively, and the meaning is the same as above.

The direction division of urban space

Zhengzhou’s central urban districts include Huiji District, Jinshui District, Guancheng Hui District, Erqi District, and Zhongyuan District42, located in different directions from the city center. The northeast extends from Jinshui District to Zhongmu County, the southeast from Guancheng Hui District to Zhongmu County, the south from Erqi District to Xinmi City and Xinzheng City, the west from Zhongyuan District to Xingyang City, and the north from Huiji District, separated from Jiaozuo and Xinxiang by the Yellow River. This paper combines the administrative boundaries of these five districts to divide the study area into five sectors: southeast, northeast, north, west, and south (Fig. 4).

A schematic diagram of fan-shaped division of built-up areas in Zhengzhou City in 2020 (Created by ArcGIS 10.8 software, http://desktop.arcgis.com/cn/).

Using the concentric circles method, the urban land density and new urban land density in each sector are calculated. The Cp and k compactness indices from the two models are then used to analyze the changes in urban form in each direction43, allowing for a comparison of the spatial heterogeneity of urban expansion across different directions.

Results and analysis

Analysis of inverse S function model

Inverse S function fitting

Urban land density reflects the overall trend of construction land development across the city. A study of Zhengzhou’s urban land density from 2000 to 2020 shows that land density is highest in the core area, with the development of the core driving surrounding economic growth. Consequently, the core area reaches saturation first, with density approaching 1. Density decreases most rapidly near the city center, where development is fastest. The urban fringe represents the city’s boundary, where land density is the lowest and remains mostly unchanged within a year. Overall, urban land density decreases gradually from the center to the periphery, fitting the “anti-S rule” and reflecting the outward shift of urban expansion over time44,45,46.

The nonlinear least squares method was used to analyze urban land density trends47, and the inverse S function was used for fitting. The average R2 value was 99.55%, indicating a significant fitting effect. Parameter a describes the steepness of the curve’s middle section, and its value decreased from 5.314 to 5.006 between 2000 and 2020, showing a smoother curve. Parameter c reflects the city’s development intensity, increasing by 0.02173 from 2000 to 2008 and by 0.14626 from 2008 to 2020, indicating rapid peripheral development. Parameter d, which describes the horizontal expansion of the main urban area, increased from 16.621 to 26.428 over the 20 years, showing the continuous spatial expansion of the main urban area (Table 1).

The 20-year fitting curve (Fig. 5) shows that the core area is about 5 km from the city center, where urban land density is saturated. From 5 km to 17 km, the curve smooths over time, with the inner city and suburbs showing significant growth. The urban fringe is located 17 km from the center, with little change before 2008, but a significant increase to 0.35 by 2020.

Breaking down the curve by 5-year intervals (Fig. 6) shows the greatest growth between the inner city and suburbs. The fastest regional growth occurred between 2010 and 2015, with the urban fringe showing the most significant jump during this period.

Division of the main urban area

The derivative of the inverse S function is analyzed using the functional parameters (a, c, d) as variables (Fig. 7). From 2000 to 2020, the boundary lines of each urban district (urban core, urban area, suburban area, and urban fringe) steadily expanded outward, without any significant short-term fluctuations. Overall, urban expansion has remained stable and orderly over time.

Based on the zoning rules and the spacing between the curves, it is evident that the inner city and suburban zones are similar in size, each expanding by 1.4 km over the 20-year period. The core and fringe areas, however, show the most significant growth, with the core area expanding by about 3.5 km and the fringe by 4 km. The radius of the main urban area increased by approximately 10 km during this period, reflecting significant expansion and aligning with the growth of the parameter d value.

Gaussian function model analysis

Gaussian function fitting

The new urban land density is primarily used to illustrate the evolving distribution of construction land across different regions of the city. Analyzing changes in the form and density of new construction land in Zhengzhou from 2000 to 2020 reveals that, during the early stages of urban development, new urban land density decreased from the city center outward. This trend reflects the concentration of newly developed land in the city center, which established the urban core. In the middle to later stages of development, as urban land became increasingly occupied, the availability of land for development in the core area diminished, leading to saturation. Consequently, the density of new urban land in the core eventually fell to zero. At this point, development in surrounding areas accelerated, resulting in a peak in new urban land density, typically located in the inner city and suburban areas48, which cover the urban-rural transition zone49,50,51. This suggests that urban construction land in these areas expands in a more organic or infill-oriented manner52. Meanwhile, the urban fringe area, farthest from the core, developed more slowly, reflecting rural expansion.

In line with urban development principles, the Gaussian function is applied to fit new urban land density, achieving an average fit (R2) of 84.47%, indicating a strong correlation. In this model, parameter a represents the peak of the function, with larger values corresponding to higher peaks, and vice versa. Over 20 years, the annual growth of a varied, with the most significant increase of 0.059 occurring in 2006–2007. Parameter b indicates the horizontal axis position of the peak, with larger values representing peaks farther from the city center. From 2000 to 2020, b increased from 9.196 to 18.439, indicating the city’s center of gravity shifting outward. Parameter c determines the width of the partition, with larger values reflecting broader regions. Over the same period, c increased from 2.877 to 7.182, indicating a significant expansion of each partition (Table 2).

By reviewing the Gaussian fit curves from the past 20 years (Fig. 8), it becomes evident that the pre-2008 curve fit was generally higher than average, with the fastest-growing areas located in the city’s urban and suburban regions. During this period of rapid growth, new urban land density reached as high as 0.073 in one year, while peripheral areas saw almost no growth. After 2008, curve fluctuations intensified, with a noticeable increase in built-up land in the periphery. From 2014 to 2020, growth in the fringe areas equaled that of the inner city and suburbs.

Division of main urban area

Observing the time series diagram of the main urban area (Fig. 9), it is clear that while there were fluctuations in boundary growth over the past 20 years, the overall trend was one of continuous expansion. Prior to 2008, the city’s boundaries expanded steadily outward. After 2008, this outward expansion became more rapid and irregular, reflecting the intensification of internal and external urban development53.

In 2017, there was an anomalous expansion of the main urban area’s boundaries, with the radius reaching 39.18 km. Excluding this anomaly, the average radius before and after this period was approximately 30 km. The anomaly may have occurred because when new urban land density in marginal areas matches that of internal city areas, the Gaussian function may not accurately model the data.

Analysis on the heterogeneity of urban expansion direction

Comparison of partition fitting degree

The urban land density in each sector direction aligns well with the characteristics of the inverse S function, with the average fit (R2) exceeding 90% in all directions. The southeast, northeast, west, and south directions had an average fit of more than 95% (Fig. 10a). The Gaussian function fit for new urban land density was less precise, with better fits in the southeast, northeast, and west (over 65%) but lower in the south and north (59% and 49.4%, respectively) (Fig. 10b). Overall, the inverse S function provided a higher fit.

Overall compactness comparison

When examining city compactness through the Gaussian and inverse S functions54,55, the Cp index derived from the inverse S function remained between 0.2 and 0.3 from 2000 to 2020, showing no significant changes, indicating sustained compact expansion. The k index from the Gaussian function fluctuated between 0.3 and 0.5, with the smallest value in 2002, suggesting that year had the most compact expansion. The largest k value, observed in 2017, indicates a looser expansion that year, suggesting a slight trend toward a less compact urban form. Despite differences between the two models, both indicate that Zhengzhou’s urban expansion remained relatively compact over the 20-year period (Fig. 11).

Comparison of partition compactness

A closer look at spatial heterogeneity across the five fan-shaped directions (northeast, west, north, south, southeast) reveals significant differences in compactness (Cp) based on the inverse S model. The northeast and north directions shifted from compact to loose, while the southeast and south grew more compact. The west direction experienced small fluctuations (compact-loose-compact) (Fig. 12a). The Gaussian model showed more volatility, particularly in the north and south, while the northeast and west followed trends similar to the inverse S model. In contrast, the southeast transitioned from compact to loose, differing from the inverse S model (Fig. 12b).

When comparing the average compactness across both models, the inverse S model indicated more compact expansion across all directions. However, the order of compactness varied slightly between the two. In the inverse S model, compactness increased in the following order: north, northeast, southeast, south, and west. In the Gaussian model, the order was north, northeast, southeast, west, and south (Fig. 12c).

Discussion

Functions essential characteristics

In the process of observing Figs. 2 and 3, it is found that the derivatives of the Gaussian function model and the inverse S-function model approximately correspond to each other. However, from a mathematical point of view, this is not the case. The inverse S-function directly describes the distribution of the total density of urban land with distance, and the farther away from the center, the density tends to be close to 0, which shows the cumulative saturation characteristics. The shape of its derivative curve is similar to the Gaussian curve, but mathematically speaking, it is only used to describe the rate of change of total density20. The Gaussian function mainly depicts the distribution characteristics of the new urban land density, which is the “bell-shaped” pattern where the new density is largest within a certain range from the center and gradually declines outward26. Its derivative curve mainly describes the sensitivity of the change in the new density. Therefore, the core difference between the two is that the physical meaning of the modeling object is different, and the local similarity in the mathematical form does not change the difference in the nature of its modeling. It is necessary to clarify whether the modeling goal is “total density” or “new density” to avoid the similarity of the graphs leading to the misuse of the theory.

Typically, urban growth is touch-and-go, and using a derivable function does not fully model this physical characteristic56. Given the complexity of urban expansion, we need a tool to approximate the dynamics of urban growth and to find a general pattern of development that can be applied among large, medium, and small cities, etc., from the research process. Functional models can provide a universal tool to analyze the spatial dynamics of cities of different scales by capturing the inherent order (e.g., the inverse S model is based on the decreasing center-periphery law, and the Gaussian model combines the bell-shaped distribution with the improvement of population density) and assist in the identification of the structured expansion mechanism under the disordered appearances.

Functional model characterization

From the perspective of mathematical modeling, the parameter settings of the inverse S-function model do not directly correspond to the physical characteristics of the city, but rather express the spatial heterogeneity of the city abstractly through mathematical functions57. This modeling method can effectively portray the unique “central agglomeration-peripheral diffusion” pattern of China’s urbanization process: in the administrative planning, the core area of the city shows a high-intensity development trend, while the rural settlements show a distribution pattern of distance attenuation. Since Chinese cities generally lack clear spatial growth boundaries, their expansion process is often manifested as a radial spreading pattern with the administrative center as the origin58. The nonlinear fitting of the inverse S function can reflect the spatial continuity characteristics of such borderless spreading, and also quantitatively analyze the difference in density gradient between the central urban area and the peripheral areas, which provides methodological support for the quantitative study of the dynamic evolution of urban spatial structure.

The application of the Gaussian function model in the study of urban expansion mainly draws on the theoretical basis of the urban population density function. The study shows that the density of land in the new city exhibits a bell-shaped distribution, which is similar to the characteristics of urban population density. After examining more than a dozen functions previously used to analyze the population density gradient, the Gaussian function family is selected and evaluated, and the classical Gaussian function, which is intuitive and simple in mathematics, is finally adopted59,60. In 1951, Clark proposed that the urban population density function has only two parameters, which has a small error in smaller partitions, and may be too large in larger partitions61. The Gaussian function can characterize the extreme value of land density, the location of expansion hotspots and spatial compactness through the parameters a (peak), b (peak position) and c (curve width), which are more accurate in portraying the large-scale spatial characteristics compared with the traditional model. Therefore, the Gaussian function can provide key information for the spatial process of urban expansion and become an important tool for studying urban expansion.

Urban expansion trend

Both the inverse S and Gaussian models offer insights into the physical evolution of urban expansion. Structurally, the Gaussian function is incrementally based, and the Gaussian model highlights the fluctuations and occasional irregularities, which may be external influences or sampling biases. To verify its robustness, this study further conducts a multi-period validation experiment with a time window of five years, and the results show that the volatility feature persists, corroborating the sensitivity of the urban system to external perturbations and its nonlinear evolutionary mechanism (Fig. 13)62. The inverse S model reveals a stable, long-term trend of continuous urban growth. These findings align with previous studies on land urbanization in different scale levels around the world63, where short-term fluctuations are often smoothed out over time. For example, the case study of mega-cities found that the phenomenon of short-term fluctuation flattening was observed in Shanghai, New York, Tokyo and other global cities, among which New York showed a Gaussian type disturbance during the reconstruction period after Hurricane Sandy, but its urban expansion from 1990 to 2020 still followed the inverse S curve64,65; A comparative study of small and medium-sized cities found that, although land urbanization in emerging growth centers such as Khon Kaen and Udon Thani in Thailand is strongly influenced by regional policies, However, the goodness of fit of the 20-year expansion trajectory is still significantly higher than that of the short-term volatility phase, confirming the dominance of the long-term trend66. Therefore, we believe that the inverse S model is more suited for examining long-term urban expansion at a macro level, while the Gaussian model is more effective for analyzing short-term, micro-level fluctuations.

Model parameters and partitions

In terms of operational simplicity, the Gaussian model is easier to apply, with its parameters b and c sufficient for defining four urban zones. The inverse S model, however, requires additional calculations using its first- and second-order derivatives, typically performed via MATLAB R2018a.

The Gaussian model’s parameters convey more information than those of the inverse S model. Parameter b identifies urban development hotspots, a reflects growth rates, and c determines partition width. Together, parameters b and c can divide the main urban area and define its boundaries26. In contrast, the inverse S model’s parameter a primarily reflects regional expansion intensity, and parameter c represents the city’s overall background value. Parameter d aligns with the b + 2c value in the Gaussian model to mark the main urban boundary. The inverse S model often requires supplementary tools to derive more meaningful insights20.

Ultimately, due to differences in their zoning rules, the two models display varying characteristics in dividing urban areas. The Gaussian model sets a fixed partition width, resulting in a balanced layout. The inverse S model, however, designates the core and fringe areas with the largest and most equivalent ranges, while the inner city and suburban areas have smaller, more similar sizes. These distinctions reflect different regional roles in urban development.

The Gaussian model’s simplicity and rich parameter data make it particularly useful for simulating future urban development, while the inverse S model offers more in-depth long-term insights28.

Spatial heterogeneity of expansion direction

From an overall analysis, the compactness indicators of both models suggest that Zhengzhou has experienced a relatively compact development trend over the past 20 years, though with slight differences. The inverse S function model remains stable without significant change, while the Gaussian function model exhibits fluctuations and a slight overall increase, indicating a trend toward reduced compactness.

When analyzing expansion in different directions, the inverse S function effectively fits urban land density in five directions, demonstrating strong performance43. However, the Gaussian function’s fitting degree, while significant overall, is not as strong when examined directionally. The inverse S function’s compactness (Cp) curve shows a consistent, stable trend across all directions. In the southeast and northeast, significant changes in Cp values suggest rapid expansion along Jinshui District and Guancheng Hui District, toward Zhongmu County. The northward expansion of Huiji District appears less compact. The westward expansion toward Xingyang City shows relatively high compactness with only minor fluctuations, while the southward expansion, toward Xinmi and Xinzheng Cities, indicates a trend toward increasing compactness67. By contrast, the Gaussian function’s fitting in the five directions is poor and highly volatile, making it less suitable for determining directional expansion trends. Thus, the inverse S function offers a more reliable tool for studying the spatial heterogeneity of urban expansion.

From this process, it can be inferred that Zhengzhou’s expansion varies across directions. Topography, traffic, and policy factors contribute to this difference. The Yellow River to the north limits development in that direction. In contrast, the southeast, home to industrial zones and Zhengzhou Airport, shows significant economic activity, drawing people, logistics, and information, which drives rapid regional development. The east and west have ample land and favorable geological conditions for large-scale urban development, though policy preferences focus on specific areas such as the aviation economy, eastern, and southern new towns, leading to uneven resource distribution. Western areas have received less attention, resulting in slower development and less expansion.

Other applications

In addition to the above studies on fitting curves of urban land density, urban zoning, and comparative analyses of compactness, we have observed that urban land density exhibits broad applicability across other domains, offering novel perspectives for scholarly inquiry. For instance, cities can be stratified by economic conditions and integrated with topographical heterogeneity to conduct macro-micro comprehensive analyses of urban land density from three dimensions: scale, topography, and economy. Such an approach facilitates exploration of the aggregation patterns in urban spatial expansion68; Focus on the different expansion modes in urban development, and evaluate the sustainability of urban expansion through the combination of land consumption and population growth rate69. In summary, integrating macro-scale density attenuation with micro-scale morphological indicators enables a holistic examination of urban expansion patterns through the “structure-process-impact” analytical framework. This multidimensional methodology provides a more robust comparative lens, advancing deeper investigations into critical issues related to urban land density.

Limitations and deficiencies

While Zhengzhou’s large-scale urban expansion makes it suitable for this research, the study’s focus on a single city raises questions about the models’ applicability in cities of varying sizes. Expanding the research to include other cities could clarify whether the differences between the two models hold across contexts. Therefore, in order to further explore the applicable boundaries of the model in cities of different sizes, future research will focus on smaller cities, which are significantly different from megacities in many ways. Given the relatively limited geographical scope of small city centers, the intensity of their expansion is often more likely to be significantly affected by a single factor, such as topographic conditions, economic development, population distribution, or policy direction. This high sensitivity may lead to the deviation of the traditional “anti-S-shaped” distribution of urban land density from the center to the periphery, and may also lead to a significant increase in the intensity of Gaussian disturbance in the short term.

Additionally, since expansion rates and scales differ by direction, future studies should explore the motivations and mechanisms driving these differences, to better understand the complexity and diversity of urban expansion.

Conclusions

This study uses the inverse S function and Gaussian function models to analyze Zhengzhou’s central urban area from 2000 to 2020. The aim is to understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of urban expansion and spatial heterogeneity by direction, while also comparing the advantages and disadvantages of both models. The key conclusions are:

-

1.

Both models capture the general trend of urban expansion, but with some differences. While the Gaussian function model captures the basic trend and multi-dimensional details of urban expansion more effectively due to its parameter structure, both models perform well in this regard.

-

2.

Although the zoning rules differ, both models divide the city into core, inner, suburban, and fringe areas. The Gaussian model is more intuitive and convenient, showing a wave-like diffusion from the center outward, which aligns with the real-world dynamics of urban development. The inverse S function smooths over this volatility, revealing a more stable and steadily increasing trend.

-

3.

The urban compactness indicators exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity. The inverse S function performs exceptionally well across all five directions, with an average fitting degree (R2) above 90%. Its compactness curves are clear and stable. In contrast, the Gaussian function struggles in the north-south directions, with R2 values of only 59% and 49.4%, limiting its capacity to capture spatial evolution comprehensively.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Li, Y., Qiao, X., Wang, Y. & Liu, L. Spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of remotely sensed regional heat Islands from 2001 to 2020 in Zhengzhou metropolitan area. Ecol. Indic. 155, 111026 (2023).

Ma, D. et al. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of urbanization and carbon emission efficiency coupling coordination: from the perspective of global countries. J. Environ. Manag. 360, 121153 (2024).

Seto, K. C., Fragkias, M., Guneralp, B. & Reilly, M. K. A meta-analysis of global urban land expansion. PLoS ONE. 6, e23777 (2011).

Zhao, K., Zhang, A. & Xu, W. Driving forces of urban construction land expansion: an empirical analysis based on provincial panel data. Resour. Sci. 33, 935–941 (2011).

Xie, H., Zhang, Y. & Duan, K. Evolutionary overview of urban expansion based on bibliometric analysis in web of science from 1990 to 2019. Habitat Int. 95, 102100 (2020).

Zhou, S., Li, M. & Xie, J. Evaluating urban–Rural gradients and urban forms in metropolitan areas: A local climate zone approach with future Spatial simulation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 112, 105636 (2024).

Zheng, M., Huang, W., Xu, G., Li, X. & Jiao, L. Spatial gradients of urban land density and nighttime light intensity in 30 global megacities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Quantifying urban expansion and its driving forces in Chengdu, Western China. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 26, 1057–1070 (2023).

Fang, C. & Zhao, S. A. Comparative study of spatiotemporal patterns of urban expansion in six major cities of the Yangtze river Delta from 1980 to 2015. Ecosyst. Health Sustain.. 4, 95–114 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Spatial differentiation characteristics and driving factors of urban polycentricity in the Yangtze river Delta region based on a geographic detector. Geocarto Int. 38, (2023).

Wang, H., Wan, Q., Huang, W. & Niu, J. Spatial heterogeneity characteristics and driving mechanism of land use change in Henan Province, China. Geocarto Int. 38, (2023).

Na, L., Shi, Y. & Guo, L. Quantifying the spatial nonstationary response of influencing factors on ecosystem health based on the geographical weighted regression (GWR) model: an example in inner Mongolia, China, from 1995 to 2020. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 73469–73484 (2023).

Wang, Y., Huang, Y. & Zhang, Y. Coupling and coordinated development of digital economy and rural revitalisation and analysis of influencing factors. Sustainability 15, 3779 (2023).

Tarek, Z. et al. Soil erosion status prediction using a novel random forest model optimized by random search method. Sustainability 15, 7114 (2023).

Gao, J., Wei, Y. D., Chen, W. & Chen, J. Economic transition and urban land expansion in provincial China. Habitat Int. 44, 461–473 (2014).

Loseva, A. V., Pudova, M. V. & Samus, D. A. The role of megacities in achieving sustainable development goals. Vestnik Nsuem. 233–243 (2019).

Zhao, R., Jiao, L., Xu, G., Xu, Z. & Dong, T. The relationship between urban spatial growth and population density change. Acta Geogr. Sin. 75, 695–707 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of rapid urban growth in the Nanjing metropolitan region of China. Landsc. Ecol. 22, 925–937 (2007).

Guérois, M. & Pumain, D. Built-up encroachment and the urban field: A comparison of forty European cities. Environ. Plan. A. 40, 2186–2203 (2008).

Jiao, L. Urban land density function: A new method to characterize urban expansion. Landsc. Urban Plan. 139, 26–39 (2015).

Xu, G., Zheng, M., Wang, Y. & Li, J. The urbanization of population and land in China: Temporal trends, regional disparities, size effect and comparisons of measurements. China Land. Sci. 36, 80–90 (2022).

Jiao, L. et al. The characteristics and patterns of spatially aggregated elements in urban areas of Wuhan. Acta Geogr. Sin. 72, 1432–1443 (2017).

Qiao, X., Liu, L., Yang, Y., Gu, Y. & Zheng, J. Urban expansion assessment based on optimal granularity in the Huaihe river basin of China. Sustainability 14, 13382 (2022).

Yang, Y., Zhang, H., Qiao, X., Liu, L. & Zheng, J. Urban expansion in major grain producing area from 1978 to 2017: A case study of Zhengzhou metropolitan area, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 33, 1–20 (2023).

Lu, H., Shang, Z., Ruan, Y. & Jiang, L. Study on urban expansion and population density changes based on the inverse S-shaped function. Sustainability 15, 10464 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Urban development wave: Understanding physical spatial processes of urban expansion from density gradient of new urban land. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 97, 101867 (2022).

Gui, B., Bhardwaj, A. & Sam, L. Revealing the evolution of spatiotemporal patterns of urban expansion using mathematical modelling and emerging hotspot analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 364, 121477 (2024).

Guo, Y., Jiao, L., Yang, X., Li, J. & Xu, G. Simulating urban growth by coupling macro-processes and micro-dynamics: A case study on Wuhan, China. GISci. Remote Sens. 60, (2023).

Li, Z., Zhou, L., Gao, H., Wang, W. & Wei, W. Spatial correlation characteristics between gradient development and land subsidence in typical mountainous towns. Adv. Earth Sci. 39, 752–765 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Spatial diffusion waves of human activities: evidence from harmonized nighttime light data during 1992–2018 in 234 cities of China. Remote Sens. 15, 1426 (2023).

Cai, E., Bi, Q., Lu, J. & Hou, H. The spatiotemporal characteristics and rationality of emerging megacity urban expansion: A case study of Zhengzhou in central China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, (2022).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 M annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 13, 3907–3925 (2021).

Schneider, A. & Woodcock, C. E. Compact dispersed, fragmented, extensive? A comparison of urban growth in twenty-five global cities using remotely sensed data, pattern metrics and census information. Urban Stud. 45, 659–692 (2008).

Jiao, L. & Dong, T. Inverse S-shape rule of urban land density distribution and its applications. J. Geomatics. 43, 8–16 (2018).

Bagan, H. & Yamagata, Y. Landsat analysis of urban growth: how Tokyo became the world’s largest megacity during the last 40 years. Remote Sens. Environ. 127, 210–222 (2012).

Arnold, C. L. & Gibbons, C. J. Impervious surface coverage: the emergence of a key environmental Indicator. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 62, 243–258 (1996).

Sudhira, H. S., Ramachandra, T. V. & Jagadish, K. S. Urban sprawl: metrics, dynamics and modelling using GIS. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 5, 29–39 (2004).

Angel, S., Parent, J. & Civco, D. L. Ten compactness properties of circles: measuring shape in geography. Can. Geogr. 54, 441–461 (2010).

Jiao, L. et al. Geographic micro-process model: Understanding global urban expansion from a process-oriented view. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 87, 101603 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. A constraint-based approach for identifying the urban-rural fringe of polycentric cities using multi-sourced data. Int. J. Geogr. Inform. Sci.. 36, 114–136 (2022).

Wang, W., Jiao, L., Dong, T., Xu, Z. & Xu, G. Simulating urban dynamics by coupling top-down and bottom-up strategies. Int. J. Geogr. Inform. Sci. 33, 2259–2283 (2019).

Dai, K., Shen, S., Cheng, C. & Song, Y. Integrated evaluation and attribution of urban flood risk mitigation capacity: A case of Zhengzhou, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 50, 101567 (2023).

Yu, J., Jiao, L. & Dong, T. Macrocosmic and microcosmic views to the analysis on the directional heterogeneity of urban expansion progress. Geogr. Geo-Information Sci. 35, 90–96 (2019).

Xu, G. et al. How does urban population density decline over time?? An exponential model for Chinese cities with international comparisons. Landsc. Urban Plan. 183, 59–67 (2019).

Dong, T., Jiao, L., Xu, G., Yang, L. & Liu, J. Towards sustainability?? Analyzing changing urban form patterns in the united States, Europe, and China. Sci. Total Environ. 671, 632–643 (2019).

Xu, G. et al. Understanding urban expansion combining macro patterns and micro dynamics in three southeast Asian megacities. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 375–383 (2019).

Bensic, M. Fitting distribution to data by a generalized nonlinear least squares method. Commun. Stat-Simul. C. 43, 687–705 (2014).

Sahana, M., Hong, H. & Sajjad, H. Analyzing urban Spatial patterns and trend of urban growth using urban sprawl matrix: A study on Kolkata urban agglomeration, India. Sci. Total Environ. 628–629, 1557–1566 (2018).

Chakraborty, S., Maity, I., Dadashpoor, H., Novotnẏ, J. & Banerji, S. Building in or out?? Examining urban expansion patterns and land use efficiency across the global sample of 466 cities with million + inhabitants Habitat Int. 120, 102503 (2022).

Airgood-Obrycki, W., Hanlon, B. & Rieger, S. Delineate the U.S. suburb: an examination of how different definitions of the suburbs matter. J. Urban Aff. 43, 1263–1284 (2021).

Tian, Y. & Qian, J. Suburban identification based on multi-source data and landscape analysis of its construction land: A case study of Jiangsu Province, China. Habitat Int. 118, 102459 (2021).

Shi, Y., Sun, X., Zhu, X., Li, Y. & Mei, L. Characterizing growth types and analyzing growth density distribution in response to urban growth patterns in peri-urban areas of Lianyungang City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 105, 425–433 (2012).

Liu, F., Zhang, Z. & Wang, X. Forms of urban expansion of Chinese municipalities and provincial capitals, 1970S–2013. Remote Sens.. 8, 930 (2016).

Li, Y., Xiong, W. & Wang, X. Does polycentric and compact development alleviate urban traffic congestion? A case study of 98 Chinese cities. CIities. 88, 100–111 (2019).

Marshall, S., Gong, Y. & Green, N. In Urban Compactness: New Geometric Interpretations and Indicators. (ed. D’Acci, L.) 431–456 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

He, Q., Song, Y., Liu, Y. & Yin, C. Diffusion or coalescence?? Urban growth pattern and change in 363 Chinese cities from 1995 to 2015. Sustain. Cities Soc. 35, 729–739 (2017).

Yu, J., Hu, Q. & Li, J. Combining visual intelligence and social-physical urban features facilitates fine-scale seasonality characterization of urban thermal environments. Build. Environ. 266, 112088 (2024).

Tian, Y. & Mao, Q. The effect of regional integration on urban sprawl in urban agglomeration areas: A case study of the Yangtze river delta, China. Habitat Int. 130, 102695 (2022).

Newling, B. E. The spatial variation of urban population densities. Geogr. Rev. 59, 242–252 (1969).

Chen, Y. & Batty, M. A wave-spectrum analysis of urban population density: entropy, fractal, and spatial localization. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2008, 576–597 (2008).

Clark, C. Urban population densities. J. R. Stat. Soc. (1951).

Yang, Y., Dong, Z., Zhou, B. & Liu, Y. Smart growth and smart shrinkage: A comparative review for advancing urban sustainability. Land 13, 660 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. A wave-shaped diffusion law for physical spatial processes of land urbanization: evidence from 234 prefecture-level cities in China. China Land. Sci. 37, 119–130 (2023).

Jiao, L. et al. Urban expansion dynamics and urban forms in three metropolitan areas—Tokyo, New York, and Shanghai. Prog. Geogr. 38, 11 (2019).

Sonet, M. S., Hasan, M. Y., Kafy, A. A. & Shobnom, N. Spatiotemporal analysis of urban expansion, land use dynamics, and thermal characteristics in a rapidly growing megacity using remote sensing and machine learning techniques. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 156, 79 (2025).

Keeratikasikorn, C. A. Comparative study on four major cities in northeastern Thailand using urban land density function. Geo-spat Inf. Sci. 21, 93–101 (2018).

Qiao, X., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, L. & Zhao, S. The influence of climate and human factors on a regional heat Island in the Zhengzhou metropolitan area, China. Environ. Res. 249, 118331 (2024).

Shukla, A., Jain, K., Ramsankaran, R. & Rajasekaran, E. Understanding the macro-micro dynamics of urban densification: A case study of different sized Indian cities. Land Use Policy. 107, 105469 (2021).

Salem, M., Tsurusaki, N., Xu, X. & Xu, G. Revealing the transformation of spatial structure of greater Cairo: insights from satellite imagery and geospatial metrics. J. Urban Manag.. 13, 565–579 (2024).

Acknowledgements

we express our gratitude to anonymous reviewers and editors for their professional comments and suggestions.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 41971274) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42271283).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G. and X.Q.; methodology, H.G.; software, Y.Y. and Q.Z.; validation, L.L. and H.G.; formal analysis, J.Z. and L.L.; investigation, H.G.; resources, X.Q.; data curation, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.; writing—review and editing, X.Q.; visualization, H.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Qiao, X., Yang, Y. et al. Modeling urban land density with Gaussian and inverse S functions by analyzing urban expansion in Zhengzhou City. Sci Rep 15, 18116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03009-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03009-4