Abstract

Increasing insecticide resistance in malaria vectors threatens the efficacy of current control tools, however knowledge of metabolic and cuticular mechanisms is widely lacking in Ghana. We examined the metabolic and cuticular resistance mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes from coastal and sahel zones of Ghana. WHO susceptibility tests and synergist assays were performed on F0 field collected An. gambiae s.l. Gene expression profiles of eight key metabolic and cuticular genes were determined using qRT-PCR. Moderate to high pyrethroid resistance (< 70%) were observed across all the sites. Piperonyl butoxide significantly increased susceptibility to pyrethroids across all sites and insecticides, implicating P450s. Gene expression analysis revealed overexpression of metabolic and cuticular resistance genes in field An. gambiae populations compared to the susceptible Kisumu strain. CYP6M2 and CYP6P3 were the most overexpressed metabolic genes in pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes, compared to the pyrethroid susceptible mosquitoes in the coastal (FC: 122.28 and 231.86, p < 0.05) and sahel (FC: 344.955 and 716.37, p < 0.001) zones respectively. CYP4G16 (previously associated with cuticular resistance) was significantly overexpressed in only resistant mosquitoes (FC: 3.32–30.12, p < 0.05). Overexpression of metabolic and cuticular resistance genes in local malaria vectors highlights the need to intensify insecticide resistance management strategies to control malaria in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vector control remains the mainstay of malaria control and elimination efforts in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)1. Over the last decade, the widespread deployment of insecticide-based vector control tools such as long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) has significantly reduced malaria transmission in SSA2,3. However, increasing insecticide resistance in malaria vectors poses a significant threat to malaria control efforts4,5,6. High insecticide resistance has been reported in many countries in SSA, with varying resistance profiles often mediated by the widespread use of insecticides in agriculture and public7,8,9. Several studies in Ghana have reported increasing resistance to multiple insecticide classes, including pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates in local malaria vector populations10,11.

Target site resistance and metabolic resistance are the two main mechanisms of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors12. However, other resistance mechanisms, namely cuticular and behavioral resistance have been involved in the development of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors13,14. Knockdown resistance (KDR) mutations in the target site for insecticides such as L1014 F, L1014S and N1570Y have been involved in pyrethroid resistance in African malaria vectors10,15. Knockdown resistance mutation, L1014 F has been found to be nearing fixation in local malaria vectors in Ghana10,11, signifying that other resistance mechanisms may be involved in the development of insecticide resistance.

Major metabolic enzymes such as cytochrome P450 s (CYP450s) monoxygenases, glutathione-s-transferases and esterases have been implicated in insecticide resistance in malaria vectors12,16,17. Overexpression of these metabolic enzymes especially CYP450 s has been linked to pyrethroid resistance in malaria vectors18,19. Overexpression of CYP6P3, CYP6P4, CYP6Z1, CYP6Z2, CYP6M2, and CYP9K1 has been linked to pyrethroid resistance in An. gambiae12,20. A study by Dadzie et al.21 showed that the use of Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) significantly enhanced the susceptibility of An. gambiae s.l mosquitoes in Ghana. Piperonyl butoxide is a synergist that inhibits metabolic enzyme, cytochrome P450 s (CYP450s) monoxygenases. This suggests that metabolic resistance may be involved in the resistance observe in local malaria vectors in Ghana.

Very little attention has been given to cuticular resistance in malaria vectors in SSA. Cuticular resistance involves modifications in the mosquito’s exoskeleton, making it more difficult for insecticides to penetrate and reach target sites22. A study by Wood et al.23 found that significantly greater cuticle thickness in permethrin resistant mosquitoes compared to susceptible ones. A study by Yahouedo et al.24 also found some cuticle genes, CPLCG3, CPR124 and CPR129 to be overexpressed in resistant An. gambiae mosquitoes and possibily involed in cuticular resistance. The overexpression of the cytochrome P450, CYP4G16 has been associated with cuticle reinforcement in resistance24.

Understanding the role of metabolic and cuticular resistance in local malaria vectors in Ghana will help in enhancing the effectiveness of current vector control tools for malaria elimination. Currently, there is paucity of data on the specific metabolic and cuticular genes that may be involved in insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Ghana. The coastal and sahel zones of Ghana exhibits significant variations in climate, agricultural practices, insecticide use and malaria transmission dynamics, factors that could influence the selection pressure and development of resistance in local mosquito populations25. Therefore, a comparative study of insecticide resistance mechanisms in An. gambiae s.l. populations from these regions is essential to identify localized resistance profiles and inform tailored control strategies. This study aims to investigate the phenotypic, metabolic, and cuticular mechanisms of insecticide resistance in An. gambiae s.l. in coastal and sahel ecological zones of Ghana. (Fig. 1)

Results

Phenotypic resistance in Anopheles gambiae S.l

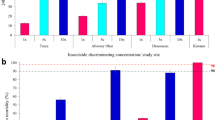

Anopheles gambiae from all study sites in the coastal and sahel zones showed high to moderate resistance to all the pyrethroids insecticides. Resistance to permethrin was also detected in each site: [Coastal sites, Tuba (15%), Opeibea (0), Nima (5%) and Teshie (30%) and Sahel sites, Libga (80%), Kpalsogu (30%), Kulaa (40%) and Tamale (15%) with significant variations in mortalities across the sites (χ2 = 183.057, df = 7, p < 0.001). Low mortality rates to deltamethrin [Coastal sites (10–35%) and Sahel sites (25–70%)] were also observed in all the sites (χ2 = 112.672, df = 7, p < 0.001). Mortality rates to alphacypermethrin were significantly lower in the Anopheles gambiae populations from Nima (0%) compared to all the other sites ((χ2 = 96.868, df = 7, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In the coastal zone, all mosquitoes from Opeibea, Nima and Teshie were resistant to malathion (70–80%) except in Tuba, which showed suspected resistance (95%). However, in the Sahel savannah sites, An. gambiae were all susceptible to malathion (> 98%). Similarly, Anopheles mosquitoes were susceptible to pirimiphos methyl in all the sites with 100% mortality rates observed in all sites except Libga (99%) and Tamale (99%). Mosquitoes were resistant to bendiocarb in all the sites (0 to 89%) except in Kulaa (95%) and Tamale (90%) (Fig. 2). Chi-square analysis showed significant differences in mortalities to the pyrethroids, bendiocarb and malathion between ecological zones and study sites (p < 0.05).

Synergist assays

Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) increased the susceptibility of An. gambiae to pyrethroids across all the sites and insecticides. In the coastal zone, pre-exposure of An. gambiae to PBO increased susceptibility to deltamethrin [Tuba (15–85%), Opeibea (0 to 10%), Nima (10–90%) and Teshie (35–60%)], permethrin [Tuba (15–65%), Opeibea (10 to 35%), Nima (5 to 45%) and Teshie (30 to 60%) and alphacypermethrin [Tuba (20–85%), Opeibea (5 to 35%), Nima (15 to 50%) and Teshie (0 to 55%)]. Despite the increase in mortality, there was no complete restoration of susceptibility observed for An. gambiae in the coastal zone (Fig. 3a).

For An. gambiae s.l mosquitoes from the Sahel zone, pre-exposure to PBO led to partial restoration of susceptibility to deltamethrin in all the sites except for Kulaa (70 to 100) where there was complete restoration of susceptibility. Increased mortality after pre-exposure to permethrin was observed in all the Sahel sites [Libga (80–95%), Kpalsogu (30% to 85), Kulaa (40–95%) and Tamale (15–95%). There was complete restoration of susceptibility to alphacypermethrin after pre-exposure to PBO in Kpalsogu (25–100%) and Kulaa (50–100%) but partial restoration of susceptibility in the other Sahel sites (Fig. 3b). For all Synergist-insecticide combinations, there was a significant difference in mortality between study sites (p < 0.05).

Species distribution of Anopheles gambiae S.l mosquitoes from the study sites

A subsample of 400 An. gambiae s.l. from all the study sites was randomly selected and used to discriminate the sibling species. Anopheles coluzzii was the most abundant species (41.75%, 167/400) followed by Anopheles arabiensis (28.75%, 115/400), Anopheles gambiae s.s. (27.75%, 111/400) and the least were the hybrids of An. coluzzii and An. gambiae s.s. (1.7%, 7/400). An. arabiensis was only detected in the Sahel zone in significant numbers especially in Tamale (84%, 42/50) and Kulaa (82%, 41/50). Table 1 shows the species discrimination of Anopheles gambiae s.l. across the study sites.

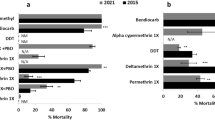

Gene expression profiles of An. gambiae S.l. Across ecological zones

Two hundred and forty (240) An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes were tested for the expression of cytochrome P450 genes (CYP6P3, CYP6M2, CYP9K1 and CYP4G16), one GST gene (GSTE2) and three cuticular genes (CLPCG3, CPR124, CPR129) relative to the housekeeping gene RPS7 and compared to Kisumu. In the coastal zone, significantly higher Fold Changes (FC) of the CYP6M2, CYP6P3, GSTE2, CYP416 and CLPCG3 were observed in the pyrethroid resistant mosquitoes compared to susceptible mosquitoes (Fig. 4). The highest overexpression in the coastal zone was observed for CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 with their resistant group having an average fold change of 231.86 and 122.23 respectively. There were no significant differences in the fold change of CYP9K1, CPR124 and CPR129 in the resistant and susceptible mosquitoes from the coastal zone (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fold expression of metabolic and cuticular genes in An. gambiae populations from the Coastal zone of Ghana. (a – b) shows the gene expression profiles of metabolic genes (a) and cuticular genes (b) respectively. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean. * P < 0.05, ns = not significant.

Gene expression profiles of An. gambiae s.l mosquitoes from the Sahel zone of Ghana showed significant differences in fold changes between phenotypically resistant and susceptible for all the genes tested (P < 0.05). Like the coastal zone, the highest overexpression was observed in CYP6P3 (fold change: 716.37) and CYP6M2 (fold change: 344.96) in the resistant group of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes (Fig. 5).

Fold expression of metabolic and cuticular genes in An. gambiae populations from the Sahel zone of Ghana. (a – b) shows the gene expression profiles of metabolic genes (a) and cuticular genes (b) respectively. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean. * P < 0.05, ns = not significant.

Gene expression profiles across the different study sites

Significant gene expression levels between the Coastal zone and Sahel zone were only observed in the GST gene, GSTE2 (t (70) = 2.007, P = 0.048) and cuticular gene, CPR129 (Mann–Whitney Z = −4.198, P < 0.001). Differential expression levels of metabolic and cuticular genes were observed across all the sites. Metabolic genes CYP6M2, CYP6P3 and CYP6P3 were significantly overexpressed in mosquitoes from all the sites compared to the susceptible Kisumu strain (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The metabolic gene CYP4G16, which is also involved in cuticular resistance was only found to be significantly overexpressed in only resistant An. gambiae mosquitoes from Tuba, Teshie, Libga, Kulaa and Tamale (FC: 3.32–30.12, P < 0.05) (Table 2). More information on the fold changes, means and standard deviations of the CT-values compared to kisimu strain are found in Supplementary Data S1.

Discussion

Understanding the role of metabolic and cuticular resistance in local malaria vectors is important to help in current insecticide resistance management efforts and malaria elimination in Ghana. This study investigated the phenotypic, metabolic and cuticular mechanisms of resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.l. across the coastal and sahel ecological zones of Ghana. Mosquitoes were resistant to all tested pyrethroids, deltamethrin, permethrin and alphacypermethrin while remaining susceptible to pirimiphos-methyl across all study sites. The metabolic genes CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 were highly expressed in both the Coastal and Sahel zones, while cuticular gene expression varied by region, with CYP4G16 most expressed in these two zones. Pre-exposure to piperonyl butoxide (PBO) increased mosquito mortality to pyrethroids across all sites. Additionally, pyrethroid resistant mosquitoes exhibited higher levels of both metabolic and cuticular resistance genes compared susceptible mosquitoes.

The expressions of key metabolic genes (CYP9K1, CYP6M2, CYP6P3, and GSTE2) were found to be upregulated in field An. gambiae s.s. compared to the susceptible colony, Kisimu strain. Significant differential expression of these metabolic genes observed between pyrethroid resistant and susceptible mosquitoes suggests that these genes may be involved in pyrethroid resistance in An. gambiae populations in Ghana. This may have serious implications on the effectiveness of pyrethroid based vector control interventions such as LLINs across Ghana. CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 were found to be overexpressed at a significantly higher fold change compared to GSTE2 and CYP9K1 in both resistant and susceptible An. gambiae populations relative to the susceptible Kisumu strain across the coastal and sahel zones of Ghana. This findings is in line with literature as CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 are considered as the main pyrethroid metabolizing enzymes in several An. gambiae populations in West Africa26,27,28. Another study by Adolfi et al.29 found CYP6P3 overexpression to confer resistance to both pyrethroids and carbamates. Our findings suggests that these two genes, CYP6P3 and CYP6M2 are greatly involved in metabolic resistance mechanisms of local malaria vectors in Ghana. However, higher expression of CYP9K1 and GSTE2 was observed in the resistant An. gambiae mosquitoes compared to the susceptible, showing that these genes may also be playing a role in resistance. CYP9K1 has been found in pyrethroid resistant mosquitoes and have been found to metabolize pyrethroids20,30. The glutathione-S-transferase GSTE2 has also been associated with DDT and pyrethroid resistance31,32. Given the prominent role of mixed-function oxidases (MFOs) in pyrethroid resistance and evidence of increased insecticide susceptibility with insecticide-PBO combinations, it is important for the Ghana National Malaria Elimination Program (NMEP) to deploy dual active ingredient LLINs to help in the management of insecticide resistance in local malaria vectors.

Higher expression of cuticular genes CYP4G16, CPR124, CPR129, and CPLCG3 was observed in resistant An. gambiae s.l mosquitoes compared susceptible mosquitoes, suggesting that cuticular mechanisms may also be involved in the observed resistance. Similarly, over-expression of CPLCG3 and CPR129 have been found to be associated with insecticide resistance through cuticle remodeling, affecting insecticide penetration rates in An. coluzzii24. The cytochrome P450, CYP4G16, consistently over-expressed in pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles mosquitoes has been recently found to be involved in cuticular hydrocarbon production and cuticle reinforcement in resistance in Anopheles gambiae22,24.

The insecticide resistance profile of An. gambiae s.l mosquitoes varied across all the study sites. Resistance to pyrethroids was widespread across all the sites. This suggests that mosquitoes from both regions are likely exposed to similar selection pressures, potentially due to the widespread use of pyrethroids in public health and agriculture. Previous studies in Ghana have also documented high levels of pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.l11,33, correlating this resistance with reduced efficacy of pyrethroid-based long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) as pyrethroids are the primary active ingredient in aerosol sprays, mosquito coils, and repellents, as well as LLINs34.

Mosquitoes were found to be fully susceptible to the organophosphate, pirimiphos-methyl in all the sites. This may be linked to the shift from pirimiphos-methyl to clothianidin for Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) in the Sahel savannah zone since 202135. This change may have contributed to the restoration of susceptibility to pirimiphos-methyl in the region. In the coastal savannah zone, the absence of IRS activities may also be contributing to the observed susceptibility of vector species in this study. A study in Ghana by Baffour-Awuah et al.34 also reported the susceptibility of Anopheles gambiae s.l populations to pirimiphos-methyl, suggesting that this insecticide remains effective for malaria control interventions across these sites.

This widespread pyrethroid resistance has serious implications on the efficacy of current pyrethroid based tools such as LLINs in Ghana. The ability of the synergist PBO to restore full or partial susceptibility to permethrin, deltamethrin and alphacypermethrin suggests that mixed-function oxidases (MFOs) contribute to the observed resistance. Similar findings have previously been observed in Ghana and west Africa21,36. This highlights the incorporation of the synergist, PBO, into pyrethroid-based vector control tools to increase the susceptibility of local malaria vectors to pyrethroids, especially in high pyrethroid sites.

Anopheles coluzzii was the most predominant species identified in all the study sites. Anopheles coluzzii prefers permanent larval habitats such as irrigated fields and breeds year-round37, which likely explains its dominance in the study sites as also reported in Ghana by Chabi et al.38. Anopheles arabiensis was exclusively found in the sahel savannah zone, consistent with findings from other studies in Ghana that showed its adaptation to arid environments39,40. Although sibling species rarely interbreed, hybrids of An. coluzzii and An. gambiae s.s. were found in low proportions, as observed in other studies in Ghana10,41. Insecticide resistance patterns varies with the species of the An. gambiae complex and gene expression profiles may vary from one species to the other42,43. A big limitation of our study was that differential gene expression profiles of metabolic and cuticular genes were not done according to species.

The over-expression of both metabolic and cuticular genes in resistant An. gambiae mosquitoes from the study sites indicates that multiple resistance mechanisms (metabolic and cuticular resistance) may be involved in insecticide resistance in An. gambiae s.l populations from Ghana. The gene expression profile of metabolic and cuticular genes varied across the study sites. Hence, there may be variations in the metabolic and cuticular genes involved in the development of insecticide resistance from one site to another. This highlights the need for further studies to determine the insecticide resistance status of local malaria vectors and the mechanisms involved to help in the development of targeted control strategies for malaria control and elimination in Ghana.

Methods

Study sites

The study was carried out in eight sites in the southern and northern parts of Ghana, from which larval collections were made during the rainy and dry seasons from June 2023 to September 2023. The sites were Opeibea (5°35′46.42″N, 0°11′01.43″W), Tuba (5°30’46” N, 0°23’20"W), Teshie (5°35’0"N 0°5’0"W), Nima (5°35’0"N 0°12’0"W), Kpalsogu (9°33′45.2″N, 1°01′54.6″W), Libga (9°35′32.26′′N, 0°50′48.8′′W), Tamale (9° 25’ 58.5084’’ N and 0° 50’ 54.4272’’ W) and Kulaa (9°26′59″N, 0°43′44″W) (Fig. 1). Opeibea, Tuba, Nima and Teshie are in the Greater Accra region in the southern part of Ghana. Opeibea and Tuba are urban irrigated agricultural sites with high herbicide, pesticide, and fertilizer use, creating abundance of mosquito breeding sites, potentially influencing insecticide resistance11. Teshie and Nima serve as controls, with poor drainage and stagnant water favoring Anopheles mosquito breeding, particularly during the rainy season.

Kpalsogu and Libga are rural communities in Northern Ghana. These sites are near irrigation dams, supporting year-round farming and mosquito breeding. Due to a high malaria burden in these sites, Kpasolgu and Libga were selected for annual IRS by the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) and Ghana National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) since 2008, though IRS in Libga was discontinued after 201444. Tamale and Kulaa are primarily residential and industrial areas with limited farming but also have mosquito breeding sites during the rainy season.

Larval collection and rearing

Anopheles mosquito larvae were collected from their breeding habitats mainly ponds, dug out wells, swamps, drainage ditches, puddles within each of the study sites. Anopheles larvae sampled were transported to the insectary at the Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, where they were raised to adults under stable conditions (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C, 80 ± 4% relative humidity). The larvae were fed on TetraMin Baby fish food (Tetra Werke, Melle, Germany). Emerged adults were fed on a 10% sugar solution until use in WHO susceptibility bioassays or synergist bioassays.

Insecticide susceptibility testing on adult mosquitoes

Susceptibility tests using WHO tubes were conducted according to the WHO protocol45 to determine phenotypic resistance. Two to 5-day-old female mosquitoes were exposed to papers impregnated with the pyrethroids permethrin (0.75%) and deltamethrin (0.05%), Alphacypermethrin (0.05%), the organophosphates pirimiphos-methyl (0.25%), malathion (5%) and the carbamate bendiocarb (0.1%). In each test, 120 mosquitoes were exposed to the insecticide-impregnated papers, and oil-impregnated papers as controls. Each test comprised six replicates (four treatments and two controls). Mosquitoes were exposed for 1 h and the knockdown was recorded every 10 min during the 60-min exposure period. Mortality was recorded after a 24-h recovery period. Alive (resistant) and dead (susceptible) mosquitoes were separately stored in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes with silica gel and some kept in RNA later for subsequent molecular tests.

Synergist assays with PBO

Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) synergist assay was performed to establish the role of cytochrome P450s in the development of resistance in the Anopheles mosquitoes. This synergist assay was performed according to WHO criteria6 using unfed females aged 2–5 days. Each test had four replicates of 20 female Anopheles mosquitoes, with each pre-exposed to 4% PBO impregnated test papers for one hour to suppress oxidase enzymes6. After pre-exposure to PBO, the mosquitoes were immediately exposed to each of the three pyrethroids (0.05% deltamethrin, 0.75% permethrin and 0.05% alphacypermethrin) separately for another hour. Two control tubes were run in parallel at any time of the testing. Knockdown was recorded during the 60 min period and mortality after 24 h.

Morphological and molecular identification of Anopheles mosquitoes

Mosquitoes used for the susceptibility tests were morphologically identified using identification keys by Gillies and Coetzee46. A subset of 400 An. gambiae mosquitoes used for the susceptibility tests were further distinguished molecularly using PCR and RFLP-PCR. The legs of each mosquito were used for DNA extraction. Four sets of primers (Anopheles gambiae, An. arabiensis, An. melas, and universal primer) were used in PCR for the identification of members of the An. gambiae s.l. species complex. Anopheles gambiae s.l were distinguished into their sibling species (Anopheles gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii) by PCR-RFLP using the method of Fanello et al.47.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis for metabolic and cuticular resistance determination

Pyrethroid resistant and susceptible An. gambiae s.l from the susceptibility tests for each site and the KISUMU susceptible lab strain were used to investigate the role of metabolic and cuticular genes in resistance. The mosquitoes were stored in RNA later at − 20 °C and grouped in pools of 10 in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Total RNA was extracted from three pools of mosquitoes (pyrethroid resistant, pyrethroid susceptible and unexposed groups) using the ZYMO Quick-RNA™ Miniprep Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was synthesized using Protoscript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit, New England Biolabs (United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The total RNA and synthesized cDNA were stored at − 80ºC.

Quantitative RT-PCR for metabolic and cuticular gene products

The study analyzed four Cytochrome P450 genes (CYP6P3, CYP6M2, CYP9K1 and CYP4G16) because of their importance in detoxification, one GST gene (GSTE2) and three Cuticular genes (CLPCG3, CPR124, CPR129) using well-described protocols14,24,26,48. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad RT-PCR machine. Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 10 µl consisting of 5 µl SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 10 µM of each primer and 2.0 µl of cDNA. The qPCR assay was performed on the Bio-Rad Opus 96 PCR System (Bio-Rad) with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s). Standard curves for all primer sets were carried out using Kisumu cDNA as a reference.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26) to compare bioassay mortalities for each insecticide among study sites. Homogeneity tests of percentages and averages were performed using standard chi-square tests with a 5% significance level threshold. The resistance or susceptibility status of the tested mosquito populations was evaluated following WHO criteria45. The CT values obtained were used in determining the expression levels of the selected genes using the delta CT method49.The house keeping gene S7 (VectorBase: AGAP010592) was used as an internal control. The fold expression of the genes was calculated using the formula, Fold change = 2 −∆∆CT with normalization against the ribosomal protein S7.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

WHO. World Malaria Report 2022. World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2022).

WHO. Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030: A Strategic Approach To Tackle Vector-Borne Diseases (World Health Organization, 2017).

Yankson, R., Anto, E. A. & Chipeta, M. G. Geostatistical analysis and mapping of malaria risk in children under 5 using point-referenced prevalence data in Ghana. Malar. J. 18, 1–12 (2019).

Hemingway, J. et al. Averting a malaria disaster: will insecticide resistance derail malaria control? Lancet 387, 1785–1788 (2016).

Donkor, E. et al. A bayesian spatio-temporal analysis of malaria in the greater Accra region of Ghana from 2015 to 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1–15 (2021).

WHO. Standard operating procedure for determining the ability of PBO to restore susceptibility of adult mosquitoes to pyrethroid insecticides in WHO tube tests. World Health Organ. 29, 283–286 (2022).

Tchouakui, M. et al. Fitness cost of target-site and metabolic resistance to pyrethroids drives restoration of susceptibility in a highly resistant Anopheles gambiae population from Uganda. PLoS One. 17, 1–15 (2022).

Toé, K. H., N’Falé, S., Dabiré, R. K., Ranson, H. & Jones, C. M. The recent escalation in strength of pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles Coluzzi in West Africa is linked to increased expression of multiple gene families. BMC Genom. 16, 1–11 (2015).

Ibrahim, S. S. et al. Molecular drivers of insecticide resistance in the Sahelo Sudanian populations of a major malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii. BMC Biol. 125, 1–23 (2023).

Hamid-Adiamoh, M. et al. Insecticide resistance in indoor and outdoor-resting Anopheles gambiae in Northern Ghana. Malar. J. 19, 1–12 (2020).

Pwalia, R. et al. High insecticide resistance intensity of Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) and low efficacy of pyrethroid LLINs in Accra, Ghana. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 1–9 (2019).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Evaluating insecticide resistance across African districts to aid malaria control decisions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 22042–22050 (2020).

Yusuf, M. A. et al. Biochemical mechanism of insecticide resistance in malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae S.l in Nigeria. Iran. J. Public. Health. 50, 101–110 (2021).

Balabanidou, V., Grigoraki, L. & Vontas, J. Insect cuticle: a critical determinant of insecticide resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 27, 68–74 (2018).

Chouaïbou, M., Kouadio, F. B., Tia, E. & Djogbenou, L. First report of the East African Kdr mutation in an Anopheles gambiae mosquito in Côte D’Ivoire. Wellcome Open. Res. 2, 1–8 (2017).

King, S. A. et al. The role of detoxification enzymes in the adaptation of the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae (Giles; diptera: Culicidae) to polluted water. J. Med. Entomol. 54, 1674–1683 (2017).

Abdullahi, A. & Yusuf, Y. Response of Anopheles gambiae detoxifcation enzymes to levels of physico-chemical environmental factors from north-west Nigeria. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 7, 93–104 (2015).

Riveron, J. M. et al. Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Vectors: An Update at a Global Scale. in Towards Malaria Elimination - A Leap Forward. (2018). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78375.

Stica, C. et al. Characterizing the molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae in Faranah, Guinea. Malar. J. 18, 1–15 (2019).

Vontas, J. et al. Rapid selection of a pyrethroid metabolic enzyme CYP9K1 by operational malaria control activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115, 4619–4624 (2018).

Dadzie, S. K. et al. Evaluation of piperonyl butoxide In enhancing the efficacy of pyrethroid Insecticides against resistant Anopheles gambiae S.l. In Ghana. Malar. J. 16, 1–11 (2017).

Balabanidou, V. et al. Cytochrome P450 associated with insecticide resistance catalyzes cuticular hydrocarbon production in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 113, 9268–9273 (2016).

Wood, O. R., Hanrahan, S., Coetzee, M., Koekemoer, L. L. & Brooke, B. D. Cuticle thickening associated with pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 1–7 (2010).

Yahouédo, G. A. et al. Contributions of cuticle permeability and enzyme detoxification to pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Kudom, A. A., Anane, L. N., Afoakwah, R. & Adokoh, C. K. Relating high insecticide residues in larval breeding habitats in urban residential areas to the S.l.ction of pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae S.l. (Diptera: Culicidae) in Akim Oda, Ghana. J. Med. Entomol. 55, 490–495 (2018).

Mavridis, K. et al. Rapid multiplex gene expression assays for monitoring metabolic resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 1–13 (2019).

Müller, P. et al. Field-caught permethrin-resistant Anopheles gambiae overexpress CYP6P3, a P450 that metabolises pyrethroids. PLoS Genet. 4 (11), e1000286 (2008).

Stevenson, B. J. et al. Cytochrome P450 6M2 from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae metabolizes pyrethroids: sequential metabolism of deltamethrin revealed. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 492–502 (2011).

Adolfi, A. et al. Functional genetic validation of key genes conferring insecticide resistance in the major African malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 116, 25764–25772 (2019).

Kouadio, F. P. A. et al. Relationship between insecticide resistance profiles in Anopheles gambiae sensu Lato and agricultural practices in Côte D’Ivoire. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05876-0 (2023).

Mitchell, S. N. et al. Metabolic and target-site mechanisms combine to confer strong DDT resistance in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS One. 9, e92662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092662 (2014).

Riveron, J. M. et al. A single mutation in the GSTe2 gene allows tracking of metabolically based insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector. Genome Biol. 15, R27. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r27 (2014).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Escalating pyrethroid resistance in two major malaria vectors Anopheles funestus and Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) in Atatam, Southern Ghana. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 799. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07795-4 (2022).

Baffour-Awuah, S. et al. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Kumasi, Ghana. Parasit. Vectors. 9, 1–8 (2016).

The PMI VectorLink Project. Annual Entomological Monitoring Report for Northern Ghana. 1–49 (Abt Associates Inc., 2021).

Owuor, K. O. et al. Insecticide resistance status of indoor and outdoor resting malaria vectors in a Highland and lowland site in Western Kenya. PLoS One. 16, 1–15 (2021).

Kudom, A. A. Larval ecology of Anopheles coluzzii in cape Coast, Ghana: water quality, nature of habitat and implication for larval control. Malar. J. 14, 447. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0989-4 (2015).

Chabi, J. et al. Insecticide susceptibility of natural populations of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae (sensu stricto) from Okyereko irrigation site, Ghana, West Africa. Parasit. Vectors. 9, 1–8 (2016).

Akorli, J. et al. Microsporidia MB is found predominantly associated with Anopheles gambiae S.s and Anopheles coluzzii in Ghana. Sci. Rep. 11, 18658. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98268-2 (2021).

Hinne, I. A., Attah, S. K., Mensah, B. A., Forson, A. O. & Afrane, Y. A. Larval habitat diversity and anopheles mosquito species distribution in different ecological zones in Ghana. Parasit. Vectors. 14, 1–14 (2021).

Dery, D. B. et al. Patterns and seasonality of malaria transmission in the forest-savannah transitional zones of Ghana. Malar. J. 9, 314. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-314 (2010).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Evaluating insecticide resistance across African districts to aid malaria control decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117, 22042–22050 (2020).

Gueye, O. K. et al. Insecticide resistance profiling of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae populations in the Southern Senegal: role of target sites and metabolic resistance mechanisms. Genes (Basel). 11, 1403 (2020).

Coleman, S. et al. A reduction in malaria transmission intensity in Northern Ghana after 7 years of indoor residual spraying. Malar. J. 16, 324 (2017).

WHO. Manual for Monitoring Insecticide Resistance in Mosquito Vectors and Selecting Appropriate Interventions (World Health Organization, 2022).

Coetzee, M. Key to the females of Afrotropical anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar. J. 19, 1–20 (2020).

Fanello, C., Santolamazza, F. & Della Torre, A. Simultaneous identification of species and molecular forms of the Anopheles gambiae complex by PCR-RFLP. Med. Vet. Entomol. 16, 461–464 (2002).

Sadia, C. G. et al. The impact of agrochemical pollutant mixtures on the selection of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae: insights from experimental evolution and transcriptomics. Malar. J. 23, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04791-0 (2024).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Centre for Vector-borne Disease Research (CVBDR) team at the Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Ghana Medical School, for the support and technical advice during this project. We also appreciate all the natives in the various study sites who offered field assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the West African Genetic Medicine Centre (WAGMC) of the University of Ghana and the National Institute of Health (R01 A1123074 and D43 TW 011513). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDD, IAB and YAA conceived and designed the study. MDD, IAB and YAA were responsible for the study design, supervised the data collection, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MDD, AA, IKS and JDA performed the data collection, laboratory work and analysis. MDD, AA and JDA drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

for this study was obtained from the University of Ghana, College of Health Sciences (CHS) Ethics and Protocol Review Committee (EPRC) (reference number: CHS-Et/M.2-P4.4/2023–2024). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the community members and village leaders prior to sampling as approved by the University of Ghana, College of Health Sciences (CHS) Ethics and Protocol Review Committee (EPRC).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dortey, M.D., Abdulai, A., Sraku, I.K. et al. Exploring the metabolic and cuticular mechanisms of increased pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae S.l populations from Ghana. Sci Rep 15, 18800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03066-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03066-9