Abstract

Cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) is a brown liquid obtained from cashew nut waste, with several applications as a renewable feedstock for polymeric industries. To obtain it, cashew nuts must undergo thermal pre-treatment processes to soften cashew nut shell (CNS) and extraction operations to separate CNSL from CNS. Although it is well known that CNSL is mainly composed of phenolic lipids, the chemical identity of minor components has not been widely explored. Thus, this study analyzed the lipid profile of CNSL using untargeted lipidomics aimed to understand the effects of CNSL extraction and cashew nut pre-treatment methods. Here, based on multivariate analysis we elucidated the differences between CNSL extracted by Soxhlet or mechanical pressing from CNS pre-treated by roasting or steaming. It was found that CNS pre-treatment displays a significant effect on CNSL regardless of the method used most likely related to lipid thermal degradation in raw nut samples. Similarly, it was found that extraction methods cause variances on lipid profile due to solvent selectivity in soxhlet method. Thus, the study expands the knowledge related to chemical differences in terms of lipid profile associated with CNSL processing, demonstrating that performing pre-treatment on CNS affects CNSL indistinctively of the method implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cashew (Anacardium occidentale) is one of the most consumed nuts around the world, with a global market size that is expected to reach USD 10.5 billion by 20311. This nut has become a promising crop for developing countries in tropical areas such as India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Nigeria and Colombia due to its soil condition and high land availability2,3.

To obtain cashew kernels that can be sold in the market, producing countries must process raw cashew nut. This involves doing a thermal pre-treatment to harvested and dried cashew nuts to soften the cashew nut shell (CNS); which is typically done either by roasting (Hot oil bath for 1.5 min) or steaming (High pressure steam for 30 min). Then cashew nuts are opened and cashew kernels are recovered, sorted and packaged4,5,6,7. However, the process involves a significant by-product generation since 75% of raw cashew nut weight is constituted by CNS as the main agro-industrial residue8.

Unlike other nut-shells, CNS has a thick honeycomb-like structure on its mesocarp that comprises a brown caustic oil-like fluid known as cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL). This substance represents 30–40% of CNS weight and has exhibited potential as a raw material to design more sustainable polymeric resins and additives, surfactants, lubricants, fuels and bioactive agents6,9,10,11,12,13. Thus, research has been done related to efficient alternatives to recover CNSL from residual CNS, where solvent extraction and mechanical extraction methods are the most explored and implemented processes among the producing countries14,15,16,17,18,19. The productive process of cashew kernel and its by-products is illustrated in Fig. 1.

CNSL oily nature has been attributed to four phenolic lipids known as anacardic acid, cardanol, cardol and 2-methylcardol, which have been reported as the main constituents of CNSL and differ significantly from the polar nature of other nut-shells extractives such as walnut, almond or pine nut20,21. While phenolic lipids from CNSL have been mostly studied as starting point for many biobased chemical products for industrial applications, their bioactivity has also gained attention for their potential to develop active ingredients for cosmetical and pharmaceutical uses. For instance, some authors have examined the effect of different isomers of anacardic acid from CNSL and its effect on biological activities, where anacardic acid triene showed high antioxidant and bioactive capacities against Artemia salina as well as inhibitory potential of the HAT enzyme activity of p300 and p300/CBP-associated factor in vitro and 64 times more antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria than salicylic acid22,23,24. Similarly, cardol has demonstrated bioactivity as a tyrosinase inhibitor by binding to the enzyme’s active site in mushroom cells and as an antiviral agent by targeting and inhibiting the envelope proteins of the dengue virus25,26,27.

There have been reports that explore CNSL composition beyond these phenolic lipids targeting potential bioactive molecules. For instance, some authors have found that CNSL samples contain hydrocarbons and components such as octacosene, sigmasterol, β-Sitosterol and triacontene28,29. Phytochemical screening has also been made on cashew nut waste, showing that CNS solvent extract contains flavonoids, saponins, certain proteins and glycosides30. Additionally, the presence of sugars, furans, phytosterols, flavonoids and fatty acid esters have been detected in solvent and water extractives of cashew shell according to other researches14. Nevertheless, other lipid species with potential bioactive capacity or key role on cashew metabolic cycles are still unknown. Furthermore, although most of the authors agree that chemical composition can be affected as a response of the extraction method selected (in terms of phenolic lipids and other components percentages), the possible relationships of CNSL processing steps (pre-treatment and extraction) with the potential species from a full lipid fingerprint of CNSL is yet to be studied.

A full lipid fingerprint through lipidomic analysis have been key to understand the effect of processing and use of edible oils from several nuts and seeds. For example, the effect of cooking methods on the chemical profile of peanut seeds has been investigated via metabolomics approach, where 630 metabolites were identified, allowing to conclude that baking process was able to preserve most of the metabolites comparing with roasting and boiling process31. Other researchers have shown the changes on lipid profile of hazelnut oil during storage, where major differences are identified on triacylglycerols, diacylglycerols, phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidyl ethanol and ceramide32. For the case of cashew, only cashew nut kernel edible oil has been analyzed through lipidomics analysis, where 141 lipids are identified including 102 glycerides and 39 phospholipids33. This demonstrates that the use of a lipidomics approach could contribute to the annotation of a full lipid profile of CNSL that could explain the effects of processing beyond physicochemical properties. However, to date, no study has been made to generate a robust lipid profile of non-edible CNSL from cashew nut shell using lipidomics analysis. Additionally, there has been poor research that understands the implication of cashew processing steps on the lipid composition of CNSL beyond phenolic lipids, especially regarding pre-treatment of cashew nut. Thus, the present article aims to understand the effect of cashew nut pre-treatment and extraction methods on the lipid profile of CNSL by a non-targeted lipidomics approach.

Results and discussion

Lipid profile of CNSL

787 features were observed in the samples of CNSL extracted by Soxhlet (SX) and mechanical pressing (P), where 27 different lipid compounds were annotated on level 3 (Putative compounds matching molecular formula and/or MS/MS data) (Table 1); which were categorized in Fatty acyls (6), glycolipids (4), glycerophospholipids (11), prenol lipids (4), sphingolipids (1) and sterol lipids (1).

According to the results, glycerophospholipids and fatty acyls are the groups that exhibit the largest amount of lipids identified. This result corresponds to previous studies, where it has been shown that glycerophospholipids and fatty acyls represent the most predominant fraction of lipid species from cashew nut. Although, it has been mentioned that the glycerophospholipid phosphatidylinositol (PI, 16:0/18:2, 18:1/18:1) is strongly involved in the development stages of cashew nut, specifically acting as a signaling lipid to inhibit cell apoptosis; phosphatidylserines (PS) and phosphatidylcholines (PC) have shown higher abundance on cashew kernel oil34,35.

For the case of CNSL the glycerophospholipids that are most abundant are PC, which are also highly present in other nuts species such as walnut, almond and cashew kernel itself33,36,37. According to the genome scale metabolic reconstruction of Anacardium occidentale, biosynthesis of PC is identified through the reaction of CDP-choline with 1,2 Diacylglycerol and shows to be a key connecting point for the biosynthesis of lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), fatty acids (FA), phosphatidic acids (PA) and diacylglycerols (DG) through the enzymatic reactions catalyzed by phospholipases PLA1, PLA2, PC and PD. These resulting lipids are also found in CNSL samples (Table 1), which confirms the reactions identified in the metabolome reconstruction. This abundancy of PC on CNSL samples could be related to its metabolic function on cashew fruit. Previous research has shown that PC is a major phospholipid that contributes to the vegetable cells membrane integrity and adaptability to the environment38. Similarly, it has been shown that PC turnover products such as PA and phosphocholine and its complexes with phospholipases can act as signaling metabolites able to aid plant defense response39. Since CNSL is located in the mesocarp of cashew nut, the presence of PC and its turnover metabolites PA, DG and LPC could be related to the protective function of cashew nut shell, which through these lipids could trigger biochemical defense and cellular adaptability.

Some of the turnover lipids from PC that are also present on CNSL samples according to lipidomic assay are FA and fatty alcohols (FOH) which could be derived from the enzymatic hydrolysis of PC with PLA1 or PLA2 to form FA and subsequent reaction with the enzyme Ω-hydroxylase to generate FOH considering the presence of these enzymes and reactions in the metabolome reconstruction. Nevertheless, the FOHs present are identified as Annonacin A (FOH 35:4;O6) and Squamone (FOH 35:5;O6) which belong to the group known as annonaceous acetogenins(AGEs). Some studies have shown that FOH serve as lipid protective layers on the aerial parts of plants which might be the case for cashew nut40. However, since the lipids identified belong to AGEs, it could be argued that these lipids not only exhibit lipid protection layer to cashew nut but also cytotoxicity as a defense mechanism according to previous studies of the bioactive potential of AGEs41.

Prenol lipids have been also identified in CNSL after lipidomic assay. Starting by Gibberellin A29, a phytohormone that is involved in diterpenoid biosynthesis as the product of the oxidation of Gibberellin A20 in presence of 2-Oxoglutarate according to the reactions identified in the metabolic reconstruction. It has been previously reported that Gibberellin A7 is actively involved in the color changes of the flowering process of cashew nut42. Since cashew nut starts growing after flowering stages and both Gibberellin A7 and A29 belong to diterpenoid biosynthesis, it could be inferred that the lipid identified in CNSL samples is a phytohormone that might contribute to cashew nut growth and development.

Other prenol lipids identified in CNSL samples are decaprenyl-methoxy-methyl-benzoquinone and hexaprenyl-dihydroxybenzoic acid where both belong to ubiquinone and other terpenoid quinones biosynthesis pathway according to Anacardium occidentale metabolome reconstruction. These lipids show to be highly correlated since polyprenyl-dihydroxybenzoic acids are precursors of polyprenyl benzoquinones in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone. These last metabolites have shown to be key electron carriers on plant respiratory chain as well as being key metabolites in plant growth and development43. Available KEGG data suggests that quinones also participate on the biosynthesis of carotenoids and gibbellerins, which can correlate to the other prenol lipids identified in CNSL samples. Thus, prenol lipids identified act as biomarkers that give evidence of the possible metabolic routes related to cashew nut flowering, growth and development.

Evaluation of the effect of extraction and pre-treatment methods by multivariate analysis

To observe the effect of processing (pre-treatment and extraction) on the lipid profile of CNSL, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied on samples of CNSL extracted either by Soxhlet(SX) or Pressing (P) whose nut was pre-treated either by roasting (R) or steaming (S). The total variance of the data explained by the PCA model built was 90.85%, with 73.61% from PC1 and 17.24% from PC2. According to PCA scores plot (Fig. 2), clear separation between raw nut and pre-treated CNSL clusters is evidenced along the axis of PC1. This shows that CNSL from nuts that have had some kind of pre-treatment (either R or S) show variances on its lipid profile compared with CNSL recovered from raw nuts.

Similarly, a separation of SX and P samples clusters is exhibited along the axis of PC2, which indicates that extraction method can cause variability on lipid profile of CNSL. It is worth noticing that there is no clear cluster separation in the scores plot related to the difference in pre-treatment methods in neither the axis of PC1 or PC2, which leads to the conclusion that this factor has little effect on CNSL lipid profile. Nonetheless, performing pre-treatment on CNSL shows a significant effect on the lipid profile since samples of CNSL from raw nut present a considerably isolated cluster.

On one hand, based on the heatmap, it can be evidenced that CNSL from raw nut show higher content of triglycerides (TGs), glycerophospholipids, decaprenyl-methoxy-methyl-benzoquinone and fatty alcohols (Fig. 3). On the other hand, samples of CNSL extracted by pressing after pre-treatment of the nut (roasting or steaming) show a less diverse lipid profile, where free fatty acids, glycerophospholipids, prenol and sterol lipids exhibit higher relative abundance compared with raw nut samples. Figure 3 also shows that some of the glycerophospholipids PC are still present in the pre-treated samples (SP, RP, SSX and RSX) but with reduced relative abundance. This phenomenon could be attributed to thermal degradation of TGs, FOH and glycerophospholipids due to the pre-treatment conditions, which leads to generation of free FA (from thermal hydrolysis) or oxidized forms of the lipids. Nonetheless, the higher thermal stability of PC compared to TGs upon heat-induced oxidation processes could explain the conservation of some of these glycerophospholipids on pre-treated samples44,45.

Other lipidomic and metabolomic studies have shown that shells, husks and kernels of certain edible nuts usually exhibit predominant accumulation of triglycerides and phospholipids; which is comparable to the results exhibited on the heatmap for raw nut CNSL samples. For instance, it has been reported that seeds from Macadamia ternifolia show accumulation of long chain TG in mature growth stages where they play a key role on seed germination. It is also demonstrated that phospholipids tend to have higher relative abundance on early growth stages of Macadamia ternifolia, where they are involved in signal transduction during abiotic stress to protect the nut against possible harmful conditions46. Similarly, literature has demonstrated that walnut (Juglans regia) husk exhibit predominance of TG, FA and PC on its lipid profile; which only differentiate from the kernel due to a higher amount of terpenoids, oxylipins and dicarboxylic fatty acids that protect the kernel from oxidation, fungal infections and abiotic stess47. Additionally, it has been observed in the mesocarp of Elaeis guineensis that this structure has a strong relationship with the metabolic cycles of lipid and fatty acid biosynthesis; which could imply that lipids such as TG, FA are likely to be present on the mesocarp of nuts prior to a migration into the kernel on the growth stages of the seed48. Results found for raw nut CNSL agree with previous research since TG and PC show the highest relative abundance in the annotated profile; which could mean that compounds from CNSL (found in mesocarp of CNS) participate on triglyceride and phospholipid biosynthesis, that then accumulate on cashew kernel on the mature growth stage. While pre-treatment conditions could lead to thermal degradation of triglycerides and formation of free fatty acids, the results suggest that raw nut CNSL is not only rich on phenolic lipids (anacardic acid, cardol and cardanol) but potentially a good source of triglycerides to be used on cosmetic formulations and lubrication industries49.

In the case of Soxhlet extracted CNSL, we found that samples display higher relative abundance of prenol lipids, sterol lipids and some glycerophospholipids (Fig. 3). Prenol and sterol lipids can be seen in higher relative abundance most likely due to the capability of organic solvents to recover components that are firmly fixed to cellular tissues and are not easily recoverable by pressing50. Since prenol and sterol lipids show higher polarity compared to other lipid species such as triglycerides and long chain FA due to the presence of aromatic and hydroxyl groups on its molecular structure; the use of a polar solvent on the extraction (acetone)could have favored the recovery of these species. This result suggests that soxhlet extraction with polar solvent might be a suitable strategy to recover CNSL with higher content of prenol and sterol lipids. Thus, new potential bioactive agents could be derived from CNSL (beyond phenolic lipids) since previous research has demonstrated that the types of prenol and sterol lipids annotated for CNSL in this study (gibbellerins, benzoquinones, benzoic acids and glucopyranosides) could generate potentially biobased surfactants and dyes for chemical industry and can exhibit interesting properties for biotechnological applications such as antimutagenic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antifungal and antibacterial activity51,52,53,54.

Furthermore, the higher relative abundance of LPC evidenced in soxhlet extracted samples compared with the pressed CNSL samples could be attributed to a possible enzymatic hydrolysis reaction of phosphatidylcholines (PC), since previous research indicate that this reaction tends to occur when the reagents are allowed to be in a polar solvent such as ethanol or acetone (the one used in extraction method), generating LPC as a result55. Since phospholipases PLA1 and PLA2 were identified in the metabolic reconstruction, this scenario shows to be highly plausible. Therefore, it could be argued that pressing extraction method favors the recovery of CNSL with higher relative abundance of PC and FA (possibly derived from TG thermal degradation) compared to soxhlet samples. This result suggests that pressed CNSL has the potential to be a useful feedstock since PC (also known as lecithin) is one of the most used natural surfactants for food and cosmetic industries as well as for pharmaceutical and medical purposes to treat respiratory distress; while FAs are widely used as a starting point to generate surfactants, polymeric additives, fuels and rheology modifiers56,57,58.

Identification of key lipids affected by pre-treatment and extraction processes by partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA)

Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was performed to elucidate the differences between the extraction methods and the effect of pre-treatment in CNSL lipid profile with maximized co-variances. Samples of CNSL from raw nut were compared one by one with pre-treated CNSL samples extracted either by SX or P. (Detailed figures can be found in supplementary material). Additionally, CNSL samples with the same pre-treatment (either R or S) were compared according to the extraction method to identify the detailed effect of this processing step in lipid profile of CNSL.

Comparative analysis between raw-nut CNSL and the rest of the samples show clear separation of the clusters in the component 1 as illustrated in Fig. 4 which compares raw nut CNSL with the samples extracted by Soxhlet from roasted CNS (RSX). For the PLS-DA analysis exhibited in Fig. 4, component 1 explains 99.8% of the variance, however, for all the comparisons of raw nut vs. pre-treated CNSL (from either roasting and steaming), the component 1 explains more than 95% of the variance (Complete PLS-DA plots can be found in supplementary material). This confirms that pre-treatment has an effect over lipid profile of CNSL since raw-nut samples shown considerable differences in lipid profile as evidenced in PCA analysis.

PLS-DA also helped to identify the metabolites which had greater contribution to the variance between the samples through VIP scores plot (Figures found in supplementary material). Results show four common metabolites with the greatest VIP scores in the comparison between raw-nut CNSL and the pre-treated CNSL samples. Similarly, other four common metabolites with significant contribution to VIP scores were identified in the comparison between SX and P extracted CNSL by either R or S pre-treatment processes. Table 2 shows the names of the main metabolites in the comparison between raw-nut CNSL and pre-treated CNSL as well as in the comparison between Soxhlet extracted and pressed CNSL.

PLS-DA analysis shows that the metabolite with the greatest contribution to the variance between raw-nut and pre-treated CNSL has an experimental mass of 905.7568 Da. By comparing the mass with the information available in HDMB and PubChem metabolite databases, it could be inferred that the metabolite belongs to the glycerophospholipid group. However, it was not possible to accurately identify this compound in the samples. VIP scores plot show that this unknown metabolite is more abundant in raw-nut CNSL. If the metabolite corresponded to a glycerophospholipid, the result would support the findings of the heatmap of the samples, since raw-nut CNSL showed a greater amount and variety of glycerophospholipids than in the rest of the samples. Nonetheless, more detailed analysis of that detection should be done to accurately confirm the nature of this metabolite.

Mosinone A was identified as the second metabolite which contributes the most to the variance between raw-nut and pre-treated CNSL. Results show that raw-nut CNSL had higher abundance of mosinone A, which suggests that there might be degradation processes due to pre-treatment. Mosinone A belongs to the group AGEs, and it has been acknowledged to be responsible of the regulation of stability and integrity of cellular membranes, as well as an ATP regulator59. Although some research has hypothesized that acetogenins are sensitive to degradation at temperatures above 50 °C, thermal stability of the molecule has not been widely explored yet60. According to the lipid profile of CNSL found in Table 1, mosinone A is not the only AGE present in the samples since isoannonacin A and squamone are also identified. Nevertheless, these compounds show also a decrease in abundance in CNSL samples after pre-treatment according to the heatmap (Fig. 3). This phenomenon supports the results evidenced in PLS-DA, which shows that pre-treatment might be triggering degradation of this metabolite as a result of the high temperature of the process. While this hypothesis must be researched in terms of thermal stability of acetogenins and fatty alcohols, the presence of AGEs in raw nut CNSL represent a significant opportunity since this kind of molecules have exhibited in previous research antitumor properties, cytotoxicity and obesity mitigation potential61,62,63. Thus, new potential research fields can be further explored for CNSL as a source of bioactive molecules.

Similarly, raw-nut CNSL shows higher relative abundance of triglycerides when compared with pre-treated CNSL. Specifically, it was identified that TG 57:9 and TG 50:6,2O had significant contribution to the variance and were more predominant in raw nut samples. This phenomenon could be attributed to thermal degradation due to high temperature processes. Since both roasting and steaming involves heating of cashew nut and its internal structures, it might be possible that triglycerides present in the sample are being transformed into free FA due to hydrolysis. Studies suggest that heating processes favors oxidation of double bonds in the aliphatic chains of triglycerides from vegetable oils, which can lead to hydrolysis and generation of free FA due to catalysis aided by hydrolytic enzymes, which are common on vegetable cells of nuts45. This result agrees with the findings of the heatmap (Fig. 3), where the differences between raw-nut and pre-treated CNSL lipid profile is strongly influenced by triglycerides degradation.

Through PLS-DA it was also possible to elucidate the effect of extraction methods over lipid profile of CNSL. Results show clear separation of clusters of SX and P extracted CNSL from R and S CNS over the first component, which explained more than 73.8% of the variance (Plots found in supplementary material). The key metabolites with higher contribution to the variance of this comparison according can be seen in Table 2, where 4 main lipids where identified.

In the first place, glycerophospholipid PA 17:1 was identified as a characteristic metabolite from SX samples, since VIP scores show that P extracted and even raw-Nut CNSL had lower amount of this metabolite compared with SX. This result is comparable with the findings of heatmap since SX samples also show high relative abundance of PA 31:3, which also belongs to the family of PA. This kind of metabolites are commonly found in cell membranes as structural elements that allow selective mass transfer, which might also be the case for CNS vegetable cells. Since pre-treatment and extraction methods favors rupture of vegetable cells of CNS to recover CNSL, it might be possible that these processing steps lead to an increased concentration of glycerophospholipids in the samples due to cell membrane rupture. For the case of PA, the increased relative abundance found in SX samples could be attributed to the polarity of the solvent used (acetone) since PA is a simpler and smaller phospholipid than PC or LPC and has a polar nature, making it suitable to be selectively recovered by the solvent involved in the extraction59,64. P extraction does not involve any polar extractant as SX extraction, which could explain PA concentration differences in the samples.

On the other hand, triglycerides TG 56:9 and TG 54:7 were identified to be predominantly on P extracted CNSL compared to SX extracted samples according to VIP scores. Although heatmap showed that the sample with higher amounts of triglycerides is raw-nut CNSL, in the comparison of pre-treated CNSL (P and SX extracted) TG 56:9 and TG 54:7 showed to be key metabolites that contribute to the variance between these samples. Higher relative abundance of these metabolites on P extracted CNSL could be also attributed to the solvent polarity of SX extraction, since polar solvents like acetone tend to recover mainly polar substances from the biomass65. Triglycerides are not considerably polar compared to other lipids such as phospholipids; thus, it might be possible that SX extracted CNSL had more selectivity towards polar phospholipids, which resulted in a sample less concentrated in triglycerides when compared to P extracted CNSL66.

Finally, jasmolone glucoside is identified as one of the metabolites that contributes the most to the variance between P and SX extracted CNSL. This metabolite belongs to the family of terpenes and has been reported to be present in plants leaves such as tea (Camellia sinensis), basil (Ocimum basilicum) and Saussurea pulchella.67,68,69. Considering that Anacardium occidentale metabolic reconstruction includes jasmonic acid biosynthesis, it could be inferred that jasmolone glucoside could be involved in this metabolic pathway as part of the plant hormones and signaling metabolites. For the case of CNSL, higher relative abundance of jasmolone glucoside were observed in P extracted CNSL independently of the pre-treatment method used in CNS. This might be related to solvent evaporation after SX extraction, which could have led to a decrease in the relative concentration of the metabolite in the purified SX extracted CNSL due to terpenes volatility. Being part of the family of terpenes it could be inferred that this molecule might exhibit high bioactivity in terms of antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory capacity70. Nonetheless, since there are few reports related to this metabolite, its behavior related to extraction process and bioactive potential is still a challenge to be studied.

Conclusions

This study explored the lipid profile of CNSL beyond phenolic lipids using untargeted lipidomics analysis aimed to understand the effect of pre-treatment and extraction methods. It was found that CNSL lipid profile is mainly constituted of fatty acyls, glycerophospholipids, triglycerides, sterol lipids and prenol lipids; where annonaceous acetogenins (mosinone A, isoannonacin A and squamone) and jasmolone glucoside stand out as key lipids from raw nut and pressed CNSL respectively that contribute to the variance among the different samples.

Also, the study showed that pre-treatment of CNS has a considerable effect on lipid profile of CNSL since raw nut samples were significantly different from the rest of the extracted CNSL in terms of triglyceride, phospholipids and fatty alcohols relative abundance, mainly due to thermal degradation of the metabolites identified. Similarly, extraction methods exhibited significant differences in the lipids identified, where soxhlet extracted CNSL showed higher amounts of phospholipids LPC and PA, prenol lipids and sterol lipids. However, no significant difference was observed in the lipid profile between roasting and steaming pre-treatments. These results allow to understand the effects of not only extraction but pre-treatment processes on CNSL detailed lipid profile; proving that beyond phenolic lipids, raw nut CNSL could be a good source of triglycerides for fuel and lubricating industries, while soxhlet extracted CNSL could be a potential feedstock for sterol and prenol lipids with high bioactivity, and pressed CNSL could be a starting point for surfactant, fuels and polymeric additives production. While further research is still required regarding extraction optimization (in terms of efficiency, selectivity and yield), effect of cashew clones and crop conditions as well as the identification of a major part of the features present on CNSL; this research expands the existent knowledge and potential opportunities for this by-product.

Materials and methods

Cashew nut shells

Cashew nut shells (CNSs) from varieties Yopare, Mapiria, Yucao and regional 8315 were kindly provided by cashew processing farms from Vichada, Colombia. CNSs were sorted according the pre-treatment method implemented by the supplier. Thus, roasted (R) CNSs were provided by “Marallano Vichada” after roasting pre-treatment of the nut in hot CNSL during 2 min. Steamed (S) CNSs were provided by “Florez Rojas Finca Agroturística” after a high-pressure steam pre-treatment during 30 min.

CNSs were dried in a convection oven at 50 °C for 27 h and were ground in a mill (mean particle size: 2.35 mm).

CNSL extraction

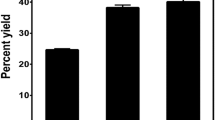

CNSL was extracted by two different methodologies: Soxhlet apparatus (SX) and mechanical pressing (P). For the first method, 20 g ground CNS were placed in a porous thimble inside a Soxhlet siphon. Acetone (PanReac AppliChem 211007, Darmstadt, Germany) was refluxed over the CNS as the extraction solvent for 30 h until the extraction was completed. Ketonic extract was concentrated in a rotary evaporator to recover CNSL. Samples were dried in a convection oven for 72 h at the boiling temperature of the solvent (56 °C) and subsequently placed in a desiccator for 48 h to eliminate solvent traces in final CNSL which was stored at − 4 °C28.

For mechanical pressing method, CNSs were placed inside the press vessel of a vertical hydraulic press. Then, the piston was located over CNS to generate compression and pressure was increased to 3000 psi leading to CNSL releasing from CNS. CNSL was collected in glass flasks and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min at 25 °C to separate suspended solids and was finally stored at − 4 °C for further analysis. Hydraulic pressing method was also used to recover CNSL from cashew nuts without pre-treatment or shelling (raw nut) as a blank sample for comparison.

Sample preparation for lipidomic analysis

20 mg of each CNSL sample were added to 500 µl of MeOH: MTBE (Sigma Aldrich 293210 and 6.06007, St Louis MO, USA) 1:1 and were stirred in a vortex for 1 min. The samples where then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm during 10 min at room temperature and the supernatant was collected and filtered through PTF 0.2 μm filters. Finally, the samples were diluted 10 times before chromatographic analysis.

Instrumental analysis conditions

Agilent technologies 1260 liquid chromatography system coupled with a mass analyzer Q-TOF 6545 and electrospray ionization was used to perform the analysis in positive mode (Agilent technologies, Inc). 1 µl of each sample were injected in a InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC-C8 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 2.7 μm) at 60 °C with a gradient elution composed by 5mM aqueous ammonium formate solution (Phase A) (Sigma Aldrich 70221, St Louis MO, USA) and 5mM ammonium formate solution in MeOH: IPA 85:15 (Phase B) (Sigma Aldrich 6.06007 and I9516, St Louis MO, USA) with a constant flow of 0.4 mL/min. Mass spectroscopy detection was performed in positive ESI mode in full scan mode from 100 to 1700 m/z and MS/MS from 100 to 1700 m/z. Throughout the whole analysis mass correction was made using reference masses: m/z 121.0509 (C5H4N4), m/z 922.0098 (C18H18O6N3P3F24). QTOF instrument was operated in 4 GHz (high resolution mode). Chromatographic elution gradient started with 75% of Phase B and increased until 96% of B at 23 min. Conditions were kept steady until minute 36 where it increased up to 100% of B until minute 41. Then, the system returned to the initial conditions in 1 min, staying in equilibrium for 9 min71.

LC-MS-QTOF lipidomic data analysis

The compounds were manually analyzed and inspected using Agilent Mass Hunter Profinder 10.0 software using recursive molecular extraction algorithm with the conditions from Table 3.

Results were filtered based on reproducibility, where molecular characteristic with variation coefficient (VC) above 20% in quality control samples (QC) were excluded. Additionally, results were filtered based on the presence of the characteristics in the 100% of the samples of each group.

To verify the quality of the data unsupervised analysis was made using principal component analysis (PCA) to evaluate stability of the analytic platform. It was confirmed good clustering between QC samples, which demonstrated that the analytic system was robust during sample processing.

The most abundant characteristics of each group were identified tentatively using criteria such as monoisotonic mass, isotopic distribution, adduct formation and molecular formula. This was achieved by consulting online databases such as Lipid MAPS, using CEU Mass mediator tool. To confirm the identity of the metabolites, annotations were made based on MS/MS spectrum and using MS/MS libraries such as MSDIAL 4.9 or in silico online spectrum such as CFM ID 4.071.

Metabolomic reconstruction of Anacardium occidentale

To support the analysis of the lipidomic assay results, metabolomic reconstruction of the species Anacardium Occidentale was performed. The genome was obtained from National Center of Biotechnology information (NCIB) database, and was annotated using Augustus model on galaxy Genome Annotation software. The metabolome reconstruction was built using RAVEN and KEGG database to identify possible metabolites and reactions derived from the species genome72.

Multivariate analysis

To understand the effect of nut pre-treatment and extraction methods on the lipid profile of CNSL, a heatmap of the lipid profile for each sample was created using the function clustergram of software MATLAB R2022b72.The analysis was complemented with Principal component analysis (PCA) that was performed using pca function on software MATLAB R2022b72. Finally, partial least square discriminant analysis(PLS-DA) was performed to elucidate the influence of key metabolites on the comparison between raw nut and pre-treated CNSL as well as Soxhlet extracted and pressed CNSL. This analysis was performed with MetaboAnalyst 6.0 tool.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Cashew Market Analysis. Outlook, Share to [2020–2030]. https://straitsresearch.com/report/cashew-market

Food and agriculture organization of the united nations. Countries by commodity. Countries Commodity (2021). https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/countries_by_commodity

Orduz Rodríguez, J. O. & Rodríguez Polanco, E. Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) a crop with productive potential: technological development and prospects in Colombia. Agron. Mesoam. 33, (2022).

Engmann, F. N., Yong-Kun, M., Abano, E. & Owusu, J. The effect of pre-treatment methods on the yield and taste of cashew kernels (Anacardium occidentale L.) high hydrostatic pressure processing view project wine production from mulberry fruit view project the effect of pre-treatment methods on the yield and taste of cashew kernels (Anacardium occidentale L.). Afr. J. Food Sci. 6, 487–493 (2012).

Ogunsina, B. S. & Bamgboye, A. I. Effect of moisture content, nut size and hot-oil roasting time on the whole kernel out-turn of cashew nuts (Anacardium occidentale) during shelling. Niger. Food J. 30, 57–65 (2012).

Prasad, K. Review on applications, extraction, isolation and analysis of cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL). Pharma Res. J. 06, 21–41 (2011).

Tawa, R., Ebun, O. & Isiaka, A. Effect of roasting on some physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) oil. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 4, (2015).

Mario, C. et al. Manejo Postcosecha De Pseudofruto De Marañón (Servicio nacional de aprendizaje-SENA, 2017).

Campaner, P., D’Amico, D., Longo, L., Stifani, C. & Tarzia, A. Cardanol-based novolac resins as curing agents of epoxy resins. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 114, 3585–3591 (2009).

Bhaumik, S. et al. Tribological investigation of r-GO additived biodegradable cashew nut shells liquid as an alternative industry lubricant. Tribol Int. 135, 500–509 (2019).

Kumar, S., Dinesha, P. & Rosen, M. A. Cashew nut shell liquid as a fuel for compression ignition engines: a comprehensive review. Energy Fuels. 32, 7237–7244 (2018).

Muroi, H., Nihei, K., Tsujimoto, K. & Kubo, I. Synergistic effects of anacardic acids and methicillin against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12, 583–587 (2004).

Roy, A. et al. CNSL, a promising Building blocks for sustainable molecular design of surfactants: a critical review. Molecules 27, 1443 (2022).

Cruz Reina, L. J. et al. Compressed fluids and Soxhlet extraction for the valorization of compounds from Colombian cashew (Anacardium occidentale) nut shells aimed at a cosmetic application. J. Supercrit. Fluids 192 (2023).

Pralhad Ashok N. T. Extraction of CNSL using screw press.

Gandhi, T., Patel, M. & Kumar Dholakiya, B. Studies on effect of various solvents on extraction of cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) and isolation of major phenolic constituents from extracted CNSL. J Nat. Prod. Plant. Resour 135–142 (2012).

Gandhi, T. S., Dholakiya, B. Z. & Patel, M. R. Extraction protocol for isolation of CNSL by using protic and aprotic solvents from cashew nut and study of their physico-chemical parameter. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 15, 24–27 (2013).

Kinetic Energy. Palm Kernel oil screw press machine cashew nut shell oil machine with oil filter-data sheet. https://wuhanhdc.en.made-in-china.com/product/eyinISHlEqWD/China-Palm-Kernel-Oil-Screw-Press-Machine-Cashew-Nut-Shell-Oil-Machine-with-Oil-Filter.html

Feitosa, J. P. A., Rodrigues, F. H. A., França, F. C. F., Souza, J. R. R. & Ricardo, N. M. P. S. Comparison Between physico-chemical properties of the technical cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) and those natural extracted from solvent and pressing. (2011).

Lubi, M. C. & Thachil, E. T. Cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL)—a versatile monomer for polymer synthesis. Des. Monomers Polym. 3, 123–153 (2000).

Queirós, C. S. G. P. et al. Characterization of Walnut, almond, and pine nut shells regarding chemical composition and extract composition. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 10, 175–188 (2020).

Morais, S. M. et al. Anacardic acid constituents from cashew nut shell liquid: NMR characterization and the effect of unsaturation on its biological activities. Pharmaceuticals 10, (2017).

Yan, B. et al. Chapter 18 - Epigenetic drugs for cancer therapy. in Epigenetic Gene Expression and Regulation (eds Huang, S., Litt, M. D. & Blakey, C. A.) 397–423 (Academic, Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-799958-6.00018-4. (2015).

Hamad, F. B. & Mubofu, E. B. Potential biological applications of bio-based anacardic acids and their derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 8569–8590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16048569 (2015).

Zhuang, J. X. et al. Irreversible competitive inhibitory kinetics of Cardol triene on mushroom tyrosinase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 12993–12998 (2010).

Kanyaboon, P. et al. Cardol triene inhibits dengue infectivity by targeting Kl loops and preventing envelope fusion. Sci Rep 8, (2018).

Lomonaco, D. et al. Study of technical CNSL and its main components as new green larvicides. Green Chem. 11, 31–33 (2009).

Yuliana, M., Tran-Thi, N. Y. & Ju, Y. H. Effect of extraction methods on characteristic and composition of Indonesian cashew nut shell liquid. Ind. Crops Prod. 35, 230–236 (2012).

Andrade, T. D. J. A. D. S. et al. Antioxidant properties and chemical composition of technical cashew nut shell liquid (tCNSL). Food Chem. 126, 1044–1048 (2011).

Nyirenda, J., Zombe, K., Kalaba, G., Siabbamba, C. & Mukela, I. Exhaustive valorization of cashew nut shell waste as a potential bioresource material. Sci Rep 11, (2021).

Xiao, Y. et al. Impact of different cooking methods on the chemical profile of high-oleic acid peanut seeds. Food Chem 379, (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Comprehensive lipidomics analysis of the lipids in hazelnut oil during storage. Food Chem 378, (2022).

Liu, Y., Li, L., Xia, Q. & Lin, L. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties, Lipid Composition, and Oxidative Stability of Cashew Nut Kernel Oil. Foods 12, (2023).

Zhao, L. et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses provide insights into metabolic networks during cashew fruit development and ripening. Food Chem 404, (2023).

Olaleke Aremu, M. et al. Lipid profile and health attributes of Mango (Mangifera indica L.) seed kernel and cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) nut kernel: A comparative study lipid profile of plants’ kernel oils. J. Hum. Health Halal Metrics. https://doi.org/10.30502/JHHHM.2022.364887.1061 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of lipid profile in dried and fresh walnut kernels by UHPLC-Q-exactive orbitrap/MS. Food Chem. 386, (2022).

Hou, J. et al. Spatial lipidomics of eight edible nuts by desorption electrospray ionization with ion mobility mass spectrometry imaging. Food Chem. 371, (2022).

Botella, C., Jouhet, J. & Block, M. A. Importance of phosphatidylcholine on the chloroplast surface. Prog Lipid Res. 65, 12–23 (2017).

Zhao, J. Phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in plant defence response: from protein–protein and lipid–protein interactions to hormone signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 1721–1736 (2015).

Rowland, O. & Domergue, F. Plant fatty acyl reductases: enzymes generating fatty alcohols for protective layers with potential for industrial applications. Plant Sci. 193–194, 28–38 (2012).

Chen, Y. et al. Antitumor activity and toxicity relationship of annonaceous acetogenins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 58, 394–400 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Huang, W., Zhao, L., Xiao, L. & Huang, H. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome reveals the mechanism of the flower coloration in cashew Anacardium occidentale. Sci. Hortic. 324, 112617 (2024).

Liu, M. & Lu, S. Plastoquinone and ubiquinone in plants: biosynthesis, physiological function and metabolic engineering. Front Plant. Sci 7, (2016).

Zhao, X. & Xia, Y. Characterization of fatty acyl modifications in phosphatidylcholines and lysophosphatidylcholines via radical-directed dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 32, 560–568 (2021).

Shi, R. et al. Combined transcriptome and lipidomic analyses of lipid biosynthesis in Macadamia ternifolia nuts. Life 11, (2021).

Shi, R. et al. Combined transcriptome and lipidomic analyses of lipid biosynthesis in Macadamia ternifolia nuts. Life 11, 1431 (2021).

Abbattista, R., Feinberg, N. G., Snodgrass, I. F., Newman, J. W. & Dandekar, A. M. Unveiling the hidden quality of the walnut pellicle: a precious source of bioactive lipids. Front Plant. Sci 15 (2024).

Hassan, H. et al. Integrative tissue-resolved proteomics and metabolomics analysis of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) fruit provides insights into stilbenoid biosynthesis at the interface of primary and secondary metabolism. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 60, 103308 (2024).

Akinoso, R., Adegoroye, E. O. & Sanusi, M. S. Effects of roasting on physicochemical properties and fatty acids composition of Okra seed oil. Measurement: Food. 9, 100076 (2023).

Wu, P. et al. Extraction process, chemical profile, and biological activity of aromatic oil from Agarwood leaf (Aquilaria sinensis) by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. J. CO2 Utiliz. 77, (2023).

Zdarta, A. et al. Biological impact of octyl d-glucopyranoside based surfactants. Chemosphere 217, 567–575 (2019).

Carcamo-Noriega, E. N. et al. 1,4-Benzoquinone antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis derived from Scorpion venom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 12642–12647 (2019).

Thompson, G. R. & Grundy, S. M. History and development of plant sterol and Stanol esters for Cholesterol-Lowering purposes. Am. J. Cardiol. 96, 3–9 (2005).

Martínez, M. J. A. & Benito, P. B. Biological activity of quinones. in 303–366 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1572-5995(05)80036-5

Baeza-Jiménez, R., López-Martínez, L. X., Otero, C., Kim, I. H. & García, H. S. Enzyme-catalysed hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine for the production of lysophosphatidylcholine. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 88, 1859–1863 (2013).

Cerone, M. & Smith, T. K. A brief journey into the history of and future sources and uses of fatty acids. Front Nutr 8, (2021).

van Nieuwenhuyzen, W. Production and utilization of natural phospholipids. in Polar Lipids 245–276 (Elsevier). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-63067-044-3.50013-3. (2015).

van Hoogevest, P. & Wendel, A. The use of natural and synthetic phospholipids as pharmaceutical excipients. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 116, 1088–1107 (2014).

Criado-Navarro, I., Mena-Bravo, A., Calderón-Santiago, M. & Priego-Capote, F. Determination of glycerophospholipids in vegetable edible oils: proof of concept to discriminate Olive oil categories. Food Chem 299, (2019).

Craycroft, D. Heat stability of annonaceous acetogenin activity in pawpaw (Asimina triloba) fruitpulp. in (2018).

Gurgul, A. & Che, C. Feature-based molecular networking and MS2LDA analysis for the dereplication of adjacent bis‐tetrahydrofuran annonaceous acetogenins. Phytochem. Anal. 36, 317–325 (2025).

Al Kazman, B. S. M., Harnett, J. E. & Hanrahan, J. R. Identification of annonaceous acetogenins and alkaloids from the leaves, pulp, and seeds of Annona Atemoya. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2294 (2023).

Han, B. et al. Annonaceous acetogenins mimic AA005 targets mitochondrial trifunctional enzyme alpha subunit to treat obesity in male mice. Nat. Commun. 15, 9100 (2024).

Stillwell, W. Membrane Polar Lipids. in An Introduction to Biological Membranes 63–87. Elsevier, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-63772-7.00005-1

Thouri, A. et al. Effect of solvents extraction on phytochemical components and biological activities of Tunisian date seeds (var. Korkobbi and Arechti). BMC Complement. Altern. Med 17, (2017).

Jaramillo, J. E. C. C., Bautista, M. P. C., Solano, O. A. A., Achenie, L. E. K. & Barrios A. F. G. Impact of the mode of extraction on the lipidomic profile of oils obtained from selected Amazonian fruits. Biomolecules 9, (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal comparisons against liquid-state fermentation of primary dark tea, green tea and white tea by Aspergillus cristatus. Food Res. Int. 172, (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Study on the comprehensive phytochemicals and the anti-ulcerative colitis effect of Saussurea pulchella. Molecules 28, (2023).

Teles, V., de Sousa, L. G., Vendramini, G. V., Augusti, P. H., Costa, L. M. & R. and Identification of metabolites in Basil leaves by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging after cd contamination. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 1, 21–28 (2021).

Herrera-Rocha, F. et al. Bioactive and flavor compounds in cocoa liquor and their traceability over the major steps of cocoa post-harvesting processes. Food Chem. 435, 137529 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. RAVEN 2.0: a versatile toolbox for metabolic network reconstruction and a case study on Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006541 (2018).

The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB version: 9.13.0 R Preprint at (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation and the OCAD of ACTeI, who carried out the feasibility, prioritization, and approval of this research with resources from the General Royalties System - SGR in the Call No. 6 of the Project “USE OF AGROINDUSTRIAL BY-PRODUCTS OF CASHEW PROCESSING IN VICHADA DEPARTMENT- BPIN 2020000100571”. Likewise, we thank the government and the community of the department in general for their interest and participation in the activities carried out to date.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.G.B., J.L. and G.O. conceived the study; G.O. and J.L performed the experiments; J.L. and G.O. analysed the data; A.F.G.B performed computational modeling; J.L wrote the manuscript; A.F.G.B., O.A, A.P, C.H, C.A.G and A.M validated the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

León, J., Ortiz, G., Barrios, A.F.G. et al. Understanding the effects of pre-treatment and extraction methods on lipid fingerprint of cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) by non-targeted lipidomics analysis. Sci Rep 15, 18103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03071-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03071-y