Abstract

Assembly of the low-pressure turbine rotor (LPTR) of an aero-engine requires the principal shaft to be inserted along the center of the aero-engine shaft hole precisely. The application of appropriate sensors is imperative for ensuring these aspects. In this paper, a custom automated assembly system (AAS) is developed for the LPTR assembly. First, we describe the overall structure and operation of the AAS. The sensor technology employed in the system is also described in detail, including its composition and principle of operation. Second, the kinematic model of attitude adjustment unit (AAU) is established based on the pose of the aero-engine and the LPTR. The kinematic equation of the AAS is developed based on the position closure approach which is more compact and coordinate free unlike the D-H method. Furthermore, the working principle of the integrated management control system of the working parts is introduced. Finally, the one-time assembly success rate and the assembly time are tested to verify the performance of the AAS. The results showed that the one-time assembly success rate and the assembly time both improvement compared to manual. Therefore, the application of many types of sensors is beneficial for the automation and precision assembly of the AAS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aero-engine is a highly complex, precision-driven, and integrated mechanical system that demands exceptional performance and stability1. Assembling is a key manufacturing step that affects the quality and stability of aero-engine products. The problems faced by aero-engine assembly include a wide variety of parts, complex shapes, significant differences in dimensions, different assembly needs, high operational accuracy requirements and tight space. At present, the assembly of aero-engine parts is still mainly manual, which leads to poor assembly positioning accuracy, low efficiency, undesirable quality assurance, and prone to accidents. To attain the high-quality assembly of aero-engine, many researchers have conducted studies on the aero-engine assembly equipment2,3,4, such as: assembly robot5, automated assembly system6, and assembly machine7,8. The development of new assembly equipment can effectively improve the automation and assembly efficiency of aviation machinery9. Moreover, precise measurement of part orientation, detection of relative part positions and contact forces, and control of the appropriate torque of the bolts, as well visualization of the assembly process, are important means to improve the assembly accuracy10,11. Therefore, it is extremely important to obtain the above data by using a variety of types of sensors.

The primary consideration in aero-engine assembly is the measured attitude and the position of the parts to be assembled. Visual inspection, laser scanners, structured light projectors, and multi-sensor fusion are common methods used to inspect parts12,13,14. Visual inspection uses a multiview camera to acquire 3D point cloud data of the part, and 3D image processing algorithms (point cloud matching, feature extraction, etc.) are used to determine the part position. Laser scanners (laser range finder, Lidar, etc.) acquire the 3D contour of the part and determine its position through point cloud data processing. Structured light projectors project a specific grating onto the surface of the part, capture the deformed grating pattern through a camera, and use algorithms to reconstruct the 3D contour to determine its position15,16.

Aero-engine assembly requires installation and mating between components in accordance with assembly processes and specifications17. When mating, tiny errors or uncertainties may generate large contact forces, causing deformation or even damage to the parts. Therefore, the assembly of parts requires real-time and high-precision acquisition of contact force. Sensors for collecting contact force between parts mainly include pressure sensors, strain gauge sensors, acoustic wave sensors, and force-sensitive resistors18. The accuracy and efficiency of force control directly affect the quality of assembly products as well as the production efficiency. Therefore, it is a high requirement for the acquisition of contact force in the assembly process. Among them, pressure sensors are frequently used for the detection of contact force with simple structure and appropriate stability19.

It is extremely important to maintain reliable and efficient connections between aero-engine parts20. The great majority of parts on the aero-engine need screw fasteners for connection and fixation. The screw fastening connection technology is more basic, widely used, and standardized in the production process by its advantages of high precision, easy assembly, and easy disassembly21. The quality of screw connections directly affects the stability of aero-engine assembly22. The reliability of bolted connections is related to the torque to be applied. Therefore, it is critical to detect the torque of screws in aero-engine assembly.

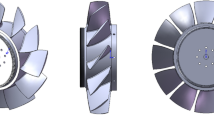

In the assembly operation of aero-engine parts, the LPTR assembly is the vital process to the aero-engine for enhanced precision and quality of assembly which greatly affects the performance of the aero-engine23,24. The LPTR mainly consists of a rotor-impeller and a principal shaft. The assembly method involves inserting the principal shaft of LPTR into the aero-engine hole, and then fastened to the other end of the principal shaft with a large nut to fix the LPTR and the aero-engine together25. In addition, to prevent the bolt loosening, a retaining ring spacer is used to set the tightened large nut and the principal shaft together. The LPTR and the aero-engine are assembled with a small installation space clearance, and a high concentricity must be maintained throughout the assembly process26. Meanwhile, the retaining ring spacer needs to be precisely matched with the keyway of the large nut and the keyway of the principal shaft, which has become a key challenge in the LPTR assembly27,28. Therefore, the research on AAS for LPTR is still to be explored29,30. To solve the assembly problem of LPTR, our paper developed an AAS for the LPTR assembly31,32. Various types of sensors are used for the attitude detection of the assembled parts, contact force measurement, visualization of the assembly process, and screw torque detection.

The vision and distance sensors are used to detect the positioning of the LPTR and the aero-engine. A force sensor is used to detect the force and position of the LPTR as it is inserted into the aero-engine hole, which can avoid damage caused by the assembly process and enhance the level of AAS automation. In addition, A micro camera to acquire the real-time positions of the principal shaft, nut, and retaining ring spacer in real-time, and accurately fix the nut and retaining ring spacer on the principal shaft. Furthermore, a dynamic torque sensor is used to monitor the tightening force of the screw in real time, which is of extreme importance for the assembly of aero-engines.

The main contributions of our paper are as follows:

-

Automated Assembly System for Aero-Engine LPTR, a multi-unit AAS was developed, integrating attitude adjustment, fixation, nut fastening, and detection modules to automate LPTR assembly. The system replaces error-prone manual operations with synchronized robotic workflows, addressing challenges in precision and confined-space assembly..

-

Multi-Sensor Fusion Framework, vision, laser, grating, torque, and angle sensors were fused to enable real-time pose detection (accuracy: \(\pm 0.05\) mm), contact force monitoring, and torque control. This closed-loop system reduces collision risks and ensures compliance with tight tolerances (rotational accuracy: \(\pm 0.1^{\circ }\)).

-

Position-Closure Kinematic Model, a coordinate-free kinematic model replaced conventional D-H methods, simplifying alignment calculations for the LPTR-aero-engine interface. The approach enhances adaptability to geometric variations while maintaining computational efficiency.

-

Validated Performance Gains, experiments demonstrated a 90% first-pass success rate (+28.57% vs manual) and 35% faster assembly (156 min/unit). These metrics confirm the system’s industrial viability for high-stakes aerospace manufacturing.

The structure of the paper is as follows: in section 2, we provide the overall structure of the AAS and the sensor system. In addition, the motion function of the principal shaft docking with the aero-engine is carried out and the control system is designed. Subsequently, the operational performance is presented in section 3 and the discussion is provided in section 4. Finally, the paper is summarized in section 5.

The assembly steps and the AAS components. (A) shows the assembled LPTR. (B) shows the AAS structure for the LPTR assembly. The structural diagrams were created using (SolidWorks Professional 2023).

Materials and methods

The structure of the AAU. (A) is the driving principal. (B) is the exploded view. The structural diagrams were created using ( SolidWorks Professional 2023).

Aero-engine assembly primary role is fastening the aero-engine parts and LPTR together by the axial tension of the LPTR principal shaft33,34. In this section, we present the detailed structure of the AAS. Figure 1A illustrated the assembly steps and the AAS components. The LPTR has a disk structure at one end and a spline structure at the other end. During the assembly, the LPTR passes through the aero-engine shaft hole, then, the LPTR principal shaft is fastened with a large nut with a keyway. After the large nut is fastened in place. A retaining ring spacer is used to prevent loosening by using with a keyway that fits into the keyway of the large nut. Then the retaining ring spacer is fastened to the retaining ring groove at the end of the principal shaft by a stop washer.

Figure 1B shows the AAS structure. The AAU clamps the disk end face of the LPTR by a concentric chuck. The position and attitude of the LPTR are adjusted by a 3-DoFs movement mechanism which are mutually perpendicular and a 3-DoFs rotation mechanism. The assembly frame (AF) function is to immobilize the aero-engine which has 1-DoFs movement mechanism and 2-DoFs rotation mechanism. The movement mechanism is used for adjusting the distance between the aero-engine and the ground, and the rotation mechanism are used for adjusting the pitch attitude of the aero-engine and the rotation concerning the axis, respectively. The detection unit (DU) has 2-DoFs movement mechanism. Besides, it has a visual localization sensor, laser distance sensor, and grating type sensor35. Detection of aero-engine and LPTR position can be realized, and specific position and attitude date can be obtained since they are essential for the accurate docking of the LPTR and the aero-engine. The nut fastening unit (NFU) can hold the large nut, retaining ring spacer, and stop the washer from docking with the principal shaft from the other end of the LPTR insertion and tighten it appropriately36. Furthermore, the NFU has a builtin micro-camera, which provides visualization for rapid and accurate assembly of the large nut, retaining ring spacer, and stop washer. In addition, the detection torque function when fastening the large nut can realize precise control of the large nut fastening torque, which can improve the assembly accuracy and efficiently.

The AAS assembly process is as follows. Before assembly operations, the aero-engine is temporarily fixed by manually bolting to the bolt holes on the outer surfaces of the aero-engine parts. Firstly, the AF height is lowered, and after the temporarily attached aero-engine is fixed to the AF by bolts. The AF height is raised to the normal height. Secondly, the disk end of the LPTR is secured to the end of the AAU by a concentric chuck. Thirdly, the DU is moved between the aero-engine and the shaft end of the LPTR. On the one hand, pose detection of the aero-engine is performed by a laser distance sensor by detecting the aero-engine shaft hole through a visual localization sensor. On the other hand, the principal shaft is scanned by the grating-type sensor to obtain the deviation of the actual pose of the principal shaft from the theoretical pose, and to calibrate the pose of the principal shaft. Furthermore, under the action of the control system, the principal shaft is inserted into the aero-engine shaft hole according to the data obtained by the DU. Finally, the NFU is assembled, and the large nut is tightened before assembling the retaining ring spacer and elastic retaining ring to complete the assembly task.

Structural design

Design of the AAU

Figure 2 shows the structure of the AAU. To describe the structure of the AAU conveniently, the coordinate system \(o_s-x_sy_sz_s\) is established by taking the plane \(o_s-x_sy_s\), the initial point of the screw of the \(y_s\) mobile platform as the \(o_s\), and the direction of the movement of the slide rods as the \(x_s\) axis, as shown in Fig. 2A.

The AAU is composed of three mobile platforms and three rotary platforms. The mobile platforms are \(x_s\) mobile platform, \(y_s\) mobile platform, and \(z_s\) mobile platform that move along the \(x_s\), \(y_s\) and \(z_s\) axes, respectively. The rotating platforms are \(x_s\) rotating platform, \(y_s\) rotating platform, and \(z_s\) rotating platform that rotate around the \(x_s\), \(y_s\) and \(z_s\) axes, respectively. The \(x_s\) mobile platform is connected to the \(y_s\) mobile platform and the \(y_s\) mobile platform is connected to the AAU pedestal by two slide rods, which are driven by motor 1 and motor 2 directly connected to the screws to make linear movements along the \(x_s\) and \(y_s\) axes, respectively. The \(z_s\) mobile platform is connected to the \(y_s\) mobile platform by four symmetrical slide rods and is driven by two coordinated motor 4-1 and motor 4-2 directly connected to the screws to move linearly along \(z_s\). The \(z_s\) rotating platform is connected to motor 3 through the rotating bearings fixed to the \(z_s\) mobile platform. The \(y_s\) rotating platform is connected to motor 6 through a rotating bearing fixed on the \(z_s\) mobile platform. The \(x_s\) rotating platform is fixed to the \(z_s\) moving platform and is driven by motor 5. Furthermore, the three rotating axes are at the same point. There is a vacancy release pin, a force sensor, and a quick coupler in the adapter board and \(x_s\) rotating platform, as shown in Fig. 2B. The vacancy release pin is released before the LPTR is inserted into the aero-engine shaft hole, and the adapter board is connected to the \(x_s\) rotating platform. The adapter board is connected by four quick couplers with a certain degree of deflection, combined with the force sensor to control the contact force, to avoid the collision between the LPTR and the aero-engine shaft hole. The adapter board can be changed according to the different types of LPTR quickly, which can improve the assembly efficiency and applicability range. The adjustment range of the AAU parameters are presented in Table 1.

Design of the AF

The AF structure is displayed in Fig. 3. Figure 3A shows the overall structure which is fixed on the ground and mainly consists of a move table, a turn table, and a circular frame. The move table is connected to the AF pedestal through slide rods. Motor 9 drives the screw through a reducer, which then drives the move table to move perpendicularly to the ground, as shown in Fig. 3B. The turn table consists of a shell and a rotating shaft. The shell is connected to the move table, and the rotating shaft is connected to the output shaft of motor 7 fixed on the shell in the form of a turbine worm gear. The center axis of the turn table is perpendicular to the move table and is driven by motor 7 to do rotating movement. The rotating table is fixed on the rotating axis of the turn table, and a circular guideway is provided in the direction perpendicular to the rotating axis of the turn table. The rotating frame is driven by motor 8 through a rightangle reducer to rotate in the circular guideway. The AF fixes the aero-engine to the rotating frame by bolting. Therefore, the aero-engine can move in three directions in the move table, the turn table, and the rotating table which range are 0-1 250 mm, 0-\(180^\circ\), and 0-\(360^{\circ }\), respectively.

The structure of the AF. (A) is the overall structure perspective diagram. (B) is the explosion diagram. The structural diagrams were created using ( SolidWorks Professional 2023).

Design of the NFU

Figure 4A shows the NFU structure which is mainly composed of a power-assisted manipulator, a quick change interface, and a tightening device. The power-assisted manipulator provides an auxiliary force by a pneumatic cylinder, so that the position of the tightening device can be easily adjusted manually. The quick change interface allows for quickly changing the tightening device to meet the needs of many types of aero-engine assembly.

Figure 4B illustrates the tightening device structure. of the NFU. The tightening device consists of a nut tightening shaft, a dynamic torque sensor, a spline sleeve, and a spline positioning shaft. The tightening device is nested inside the nut tightening shaft and can be adjusted relative to the tightening shaft. The spline positioning shaft is embedded inside the nut tightening shaft and can be rotated relative to each other. One end of the spline positioning shaft is connected to the hand-wheel, another end has a spline that is adapted to the large nut and is equipped with a micro camera inside. The nut tightening shaft is connected through a gear to a reduction gear driven by motor 10. The torque and rotation angle of the nut tightening shaft are detected by the dynamic torque sensor and angle sensor. The positioning pin is used to connect or disconnect the spline positioning shaft and the nut tightening shaft37. The NFU has two important roles, one is to assemble the large nut and the other is to assemble the retaining ring spacer accurately so that it fits with the spline of the large nut. During assembly of the large nut, the positioning pin is released to disconnect the spline positioning shaft from the nut tightening shaft. Secure the large nut to the splined end of the spline positioning shaft and adjust the tightening device so that it accurately seats the large nut against the LPTR principal shaft. Meanwhile, the positioning pin is inserted to connect the spline positioning shaft and the nut tightening shaft, and then turn on the automatic tightening system of the large nut. The large nut will be screwed into the principal shaft under the drive of motor 10, and the dynamic torque sensor and angle sensor will detect the torque and angle to reach the LPTR principal shaft.

Here, the micro camera captures the relative position error between the principal shaft spline and the large nut spline, and the position difference values are obtained after image processing automatically. Motor 10 rotates the large nut again according to the position difference value, to make its keyway aligned with the nearest keyway of the principal shaft. Then withdrew the tightening device, fixing the retaining ring spacer at the spline end of the spline positioning shaft, and then go deep into the aero-engine shaft hole again. The convex groove of the retaining ring spacer is assembled on the large nut and the principal shaft groove under the guidance of the micro camera. Finally, following the same method, the stop washer is installed to complete the assembly of the principal shaft.

The structure of the NFU. (A) is the overall structure. (B) is the tightening device structure. The structural diagrams were created using ( SolidWorks Professional 2023).

Design of the DU

The main function of the DU is to inspect the position and orientation of the LPTR and the aero-engine. Figure 5 presents the DU structure. The frame is fixed on the ground by slide rails. Motor 11 drives the frame through the screw to move the total DU, and the upper part of the frame is positioned by four slide rails, and the detection device is driven by the lifting driver, which consists of a camera, an optical grating transducer, and three laser distance sensors. The laser distance sensors are equally spaced around the camera, and the spacing between the three-lasers distance sensory and the camera is adjustable, so that the detection accuracy is highest when the diameter is slightly smaller than the end face of the aero-engine. The camera is locating the center of the aero-engine shaft hole. The laser distance sensors are used to measure the distance of the sensor itself perpendicular to the aero-engine end face, and the pose of the aero-engine end face is calculated according to the distance. The optical grating transducer can scan the LPTR driven by the frame which can give the pose of the LPTR.

Sensor system

The main functions of the sensors are the detection of LPTR and aero-engine position and attitude, measurement of contact forces, detection of torque, and visualization of the operating process. These sensors have a vital role in aero-engine assembly.

Accurate detection of the position and orientation of the assembled parts is a key challenge to be solved in the assembly operation. Contact and non-contact measurement sensors are the two commonly used detection methods. Non-contact measurement is more widely used. In this paper, we use vision, laser distance, and optical grating transducer sensors for the structural dimension measurement of the assembly parts. A camera and three laser distance sensors are used to detect the position and orientation of the aero-engine. Based on the design values, the detection device moves the camera and the laser distance sensors to the same position as the center point of the aero-engine. The camera takes images of the aero-engine end face. After the image is processed by binarization and feature detection, the position of the aero-engine can be obtained from the position of the detection device. Then, the detection device is driven by the lifting driver to align the center point of the camera to the same position as the center point of the aero-engine shaft hole. At this point, the laser distance sensors measure the relative distance between their own position and the aero-engine end face. Based on the distance parameters, the aero-engine position can be calculated. Due to the elongated shape of the LPTR, the aforementioned method is unsuitable for attitude detection of such objects. Therefore, an optical grating transducer (with a distance range of 50-250 mm and an accuracy of ±0.09%) is employed for measuring the LPTR. The transducer is positioned at a relative \(90^{\circ }\) angle, enabling the collection of distance measurements in mutually perpendicular planes. Based on these values, the position and orientation of the LPTR can be calculated, as detailed in the following section. Meanwhile, the posture of the aero-engine is derived from the readings of three laser distance sensors.

During the insertion of the principal shaft into the aero-engine shaft hole, the clearance between them is very small. Even minor errors can lead to assembly failure. If the force between the principal shaft and the aero-engine is not detected during the assembly process, accidental factors can easily lead to their collision damage. We have installed a force sensor in the AAU to detect the force between the principal shaft and the aero-engine in real time. By setting the threshold value, the force sensor can send a warning if something unexpected occurs. The LPTR and the aero-engine are connected together by a large nut, and the torque of this nut is a key factor affecting the stability of the connection. To address this issue, we use a dynamic torque sensor to monitor the torque of the nut in real time. During the tightening process, the installation condition can be judged by the threshold value of the dynamic torque sensor and the trend of the torque change. To prevent the large nut from loosening, a retaining ring spacer is used, and a stop washer prevents the spacer from loosening. Both the retaining ring spacer and the stop washer need to be assembled in the aero-engine shaft hole.

The assembly workspace is confined and challenging to observe, and aligning the retaining ring spacer with the large nut renders this process both intricate and time-consuming. To address this issue, we employ a micro camera to capture the angular discrepancy between the retaining ring spacer and the large nut in real time, thereby providing a continuous visual representation of the assembly process. Additionally, an angle sensor is used to adjust the retaining ring spacer based on the angular difference detected by the micro camera, enabling operators to swiftly complete the installation of both the retaining ring spacer and the stop washer.

The structure of the DU. The structural diagrams were created using ( SolidWorks Professional 2023).

Kinematic analysis

The traditional D-H method for analyzing robot motion requires the establishment of an accurate coordinate system and many matrix operations. It makes the robot motion analysis more complicated. In this paper, the theoretical methods employed to describe the kinematics of assembly robots that utilize position closure. Distinguish from the D-H method commonly utilized in research, this theoretical method is not coordinate-dependent, making it easily adaptable to geometric changes. Additionally, the kinematic equations are more concise and straightforward to relate to the robot’s structure. We analyzed the clearance tolerance range for the LPTR clearance fit area, which is 0.155-0.16 mm. Taking into account the cumulative manufacturing process errors, the design tolerance threshold standard has been set with three times the precision of the clearance tolerance range. The motion positioning accuracy between the LPTR spindle and the aero-engine shaft bore is specified to be \(\le \pm\)0.05 mm, with a repeat positioning accuracy of \(\le \pm\)0.03 mm and a rotational axis accuracy of \(\le \pm\)0.1 °. These values are considered acceptable for the application. For the selection of actuators and sensors in the system’s kinematic mechanism, components with moderate cost were chosen, ensuring that the overall system manufacturing cost remains acceptable to the user.

An absolute coordinate system \(\ \left\{ G\right\}\) is established with the DU at the leftmost side as the point \(\ o\), the horizontal plane as the \(\ o-xy\), the direction of movement of the DU as the x-axis, the y-axis perpendicular to the x-axis on the horizontal plane, and the z-axis in the vertical direction (Fig. 6)38. The position of \(p_1\) in the coordinate system \(\ \left\{ M\right\}\) is:

Where: \(\theta _1\), \(\theta _2\), and \(\theta _3\) are the angles of rotation of the AAU about the z, y, and x-axes, respectively; \(l_3\) is the distance from the origin of the coordinate system \(\left\{ M \right\}\). to the endpoint of the LPTR on the central axis. \(\varvec{p}_1\) is the center point of the spline end of the LPTR.

When:

There is:

Equation 3 can be written as:

When:

There is:

Equation 6 can be written as:

Here, we can obtain Eq. 8 from Eq. 5:

From Eq. 8, we can get: \(c_{2x}=l_3\), \(c_{2y}=0,c_{2z}=0\). Substituting the values of \(c_2\) into Eq. 7, we get:

Substituting Eq. 9-Eq. 11 into Eq. 4, we get:

Squaring Eqs. 12 and 13, respectively and then summing them gives:

Squaring Eqs. 9 and 11, respectively and adding them together gives:

From Eqs. 15 and 16, we can obtain:

From Eqs. 12 and 13, we can obtain:

This is obtained by substituting the above values into Eq. 7:

At that, all the unknown quantities are obtained.

The relative coordinate system \(\left\{ M \right\}\) and the absolute coordinate system \(\left\{ G \right\}\) get the relationship as:

Where: \(l_1\), \(l_2\), and \(d_1\) are the displacements of the relative coordinate system \(\left\{ M\right\}\) concerning the x, y, and z-axes of the absolute coordinate system \(\left\{ G\right\}\), respectively.

It is obtained from Eq. 20 :

From Eq. 21 we can know:

So far, the inverse kinematic functions of the AAU are obtained, and the position of \(\varvec{p}_1\) can be adjusted by obtaining the coordinates of \(\varvec{p}_1\)39. To accurately align the aero-engine shaft hole with the LPTR, it is necessary to make the endpoints of the LPTR principal shaft coincide with the leftmost endpoint of the aero-engine shaft hole, that is, the \(\varvec{p}_1\) and \(\varvec{p}_2\) are in the same point, and to ensure that the angles of the LPTR in the x-axis and z-axis remain the same before the alignment.

That is:

Where: \(\varvec{p}_2\) is the end point of the aero-engine shaft hole in the x-axis.

The position of \(\varvec{p}_2\) can be obtained from \(\varvec{p}_3\) in the DU. The DU is calibrated before inspection to ensure that the three distance sensors are in the same plane. In addition, the position of the DU can be obtained by calibrating the DU drive back to the home position and then recording the movement parameters when running to the operating position. The position of \(\varvec{p}_3\) is:

Where: \(\varvec{p}_3\) is the center point of the DU camera in the plane o-yz. \(l_8\), \(l_7\) and \(d_4\) are the displacements of \(\varvec{p}_3\) in the x, y, and z-axes, respectively.

The position of \(\varvec{p}_2\) is:

Where: \(l_4\), \(l_5\), and \(d_2\) are the displacements of \(\varvec{p}_2\) on the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis, respectively.

All the information of \(\varvec{p}_3\) is known. The camera of DU can ensure that \(\varvec{p}_2\) and \(\varvec{p}_3\) are in the same line in the direction of the x-axis. Then there is: \(p_{2x}=p_{3x}\), \(p_{2y}=p_{3y}\). Furthermore, the distance \(d_l\) between \(\varvec{p}_2\) and \(\varvec{p}_3\) in the x-axis is obtained from the distance sensor.

This gives the position of \(\varvec{p}_2\) as:

The LPTR angle in the x and z-axes can be obtained from the aero-engine angular deviation in the x and z-axes. Once the aero-engine is loaded into the AF, the drive is recovered to the initial position. That is, when \(\theta _4\) and \(\theta _5\) angles are set to \(0^{\circ }\) and \(d_2\) is the middle of the design stroke40. The DU gradually moves towards the shaft hole, with the camera at the center of the three distance sensors(\(o_l\)).

One of the sensors is in the z-axis and the position of the shaft hole is detected by the image processing method. So that the camera and the shaft hole are colinear in the x-axis direction and at distance of \(d_l\), at which point the distance between itself and the aero-engine end face is measured by three equally laser distance sensors distributed around the circumference, as shown in Fig. 5.

The distances are \(d_{l1}\), \(d_{l2}\), \(d_{l3}\), and the horizontal angle (the same as \(\angle o\)-xz) and vertical angle (the same as \(\angle o\)-yz) of the aero-engine end face offset from the plane o-xy can be obtained as:

During fixing the LPTR to the AAU, the LPTR pose is not consistent with the theoretical value due to assembly error. Therefore, DU is required to correct the LPTR pose. Before detection, \(\theta _1\), \(\theta _2\), and \(\theta _3\) are set at zero position, DU is the same in y-axis and z-axis as the coordinate system \(\left\{ M\right\}\), and DU scans the LPTR along the x-axis by the optical grating transducer41. Figure 7 shows the schematic diagram of the LPTR attitude detection. Figure 7A is the projection of the LPTR in the plane o-xy, and Fig. 7B is the projection of the LPTR in the plane o-xz.

Where: \(l_m\) is the length of the LPTR; \(a_y\) and \(e_y\) are the positional differences between the LPTR and the detected LPTR ends in the plane o-xy; \(\theta _e\) is the angle of deviation between the LPTR and the detected LPTR in the plane o-xy; \(a_x\) and \(e_x\) are the positional differences between the LPTR and the detected ends of the LPTR in the plane o-xz; \(\theta _a\) is the angle of deviation of the LPTR from the detected LPTR in the plane o-xz.

When set \(\theta _1=\theta _l+\theta _e\), \(\theta _2=\theta _v+\theta _a\), the angular deviation between the axis of the LPTR and the axis of the aero-engine shaft hole can be ensured to be the same. Then, make the \(\varvec{p}_1\) same as the \(\varvec{p}_2\), and the accurate insertion of the LPTR into the shaft hole can be achieved. Combined with the deviation of the position of the LPTR, it can be obtained:

Control system of the AAS

The control system uses a host computer integrated control software, which consists of an integrated management module, a calibration module, an acquisition module, a control module, and a database42,43. The integration management module analyses data from the calibration module, the control module, the database, and the acquisition module are coordinates the work of these modules. The calibration module can calibrate the acquisition module to avoid errors caused by errors in the acquisition module itself. The calibration module is applied to improve the accuracy of the assembly. The acquisition module is recording the assembly process in real time. The acquired data is sent to the integration management module to realize the data required for real-time control of the assembly process. The control system controls the motion of the AAS. It can automatically analyze the motion that the AAS should take according to the data acquired by the acquisition module.

The control system can adjust the LPTR pose and the aero-engine automatically, and complete the assembly operation. The database is used to save the assembly parameters required for each type aero-engine. The data is provided to the integration management module to further control other subsystems to perform their work. In addition, the database can record the data generated during the assembly process to facilitate assembly quality traceability. The structural components and relationships of the control system is shown in Fig. 8. According to the AAS operation design parameters, the required paraments such as LPTR insertion depth, large nut torque, rotation angle, distance sensor, and others have obtained from the database and the assembly operation steps are also set44,45.

Firstly, the DU is calibrated by moving it to a predetermined reference position. Its actual position is then verified and adjusted using a laser tracker, and the unit’s laser ranging and optical grating sensors are concurrently calibrated. Subsequently, the calibration of the AAU is conducted, focusing on both its position and angle control systems. A similar calibration procedure is performed on the AF to ensure accurate positional and rotational alignment. Finally, the position control system of the NFU and its dynamic torque sensor are calibrated. The user employs the instrument to detect the sensors of the AAS one by one to see if they are consistent with the design values. Another is that the integration management module controls the acquisition module to return to the initial position, through the measurement instrument to get the frame and lifting driver of the detection unit at the zero-position difference parameter, detection device plane, and frame plane difference parameter46. The integration management module controls the correction of the acquisition module based on the different parameters. The calibration can eliminate the errors generated by the sensor and assembly operation.

After fixing the LPTR and the aero-engine. The acquisition module starts to detect the pose of the aero-engine and the difference between the actual and theoretical position of the LPTR. After the integration management module modifies the difference between the actual and theoretical pose of the LPTR, it calculates and analyses the pose in which the LPTR can be accurately inserted into the hole according to the pose of the aero-engine. Then, the control module drives the AAU to complete the operation of inserting the LPTR into the shaft hole according to the data from the integration management module. During the insertion process, the builtin force sensor of the AAU monitors the contact force between the LPTR and the aero-engine in realtime, and alerts in time if the contact force exceeds the threshold, so as to correct the principal shaft insertion operation. Finally, after placing the large nut, motor 10 is actuated to tighten the large nut according to the set parameters. The dynamic torque sensor and angle of rotation of the large nut are detected by the dynamic torque sensor and angle sensor together. The comprehensive working algorithm is shown in algorithm 1.

Results

One-time assembly success rate

One-time assembly success rate is an important indicator of the effectiveness of AAS in aero-engine assembly operations47. The main considerations of assembly success rate are whether the LPTR and the aero-engine shaft hole can be successfully aligned, whether the LPTR can be successfully inserted into the shaft hole, and whether the large nut is correctly tightened. Ten tests are conducted using the developed AAS for aero-engine assembly at the same test conditions. The tests are conducted over three days from 5th December to 7th December 2023. The same aero-engine, LPTR and operators are engaged in the tests. The one-time assembly success rate indicators are divided into two categories. The AAS can automatically complete the LPTR assembly in normal operation. After the assembly is completed, disassembly and inspection of the mating surfaces of each part have no obvious signs of collision or friction interaction, indicating that the assembly quality meets the process requirements. Furthermore, after running on the aero-engine test bench, these indicators are monitored through vibration, abnormal noise to check whether they are qualified. In total of 10 tests, 9 batches passed the assembly debugging while one batch is failed. The one-time assembly success rate of manual assembly and AAS is shown in Fig. 9A.

Assembly time

The assembly time of aero-engines is an important means of evaluating the efficiency of the AAS48. The aero-engine assembly time includes the fixed time of the aero-engine to be assembled, the fixed time of the LPTR, the inspection time, the assembly time, the bolt inspection and positioning time, and the tightening time. Before the tests started, the AAS is adjusted to the working state. The aero-engine and LPTR to be assembled are placed in the area to be assembled. The aero-engine to be assembled in the tests are all the same type, with an LPTR diameter of 49.98 mm and a total length of 1200 mm. The diameter of the aero-engine shaft hole is 50 mm, and the end face diameter is 682 mm circular. The tests are conducted 6 times, and the assembly time is from the beginning to the completion assembly. To minimize experimental errors, the same operators are used during the tests. The tests are conducted over two days from 13th December to 14th December 2023, with three batches of tests per day. If the assembly fails, it will not be counted in the test statistics. The results are shown in Fig. 9B. The maximum, minimum, and average assembly times are 162, 148, and 156 min/unit, respectively.

Discussion

Aero-engines, representing highly complex and precision-engineered equipment, are manufactured by a limited number of nations and regions, resulting in a concentrated research landscape for aero-engine assembly equipment. Current aero-engine assembly practices are predominantly manual, supplemented by limited mechanization primarily focused on positioning individual components, with subsequent component installations performed manually11. In contrast, the AAS developed for principal shaft assembly operations represents a more integrated approach. The AAS encompasses an AAU, an AF, and a nut tightening unit, working collaboratively to automate the principal shaft installation process. Furthermore, the AAS architecture and control system incorporate a quick coupler and a universal control system, enabling rapid adaptation to diverse aero-engine types and facilitating flexible integration within the broader assembly workflow. This design consideration for post-assembly operations enhances the system’s overall flexibility and applicability.

For aero-engine assembly equipment applied in actual production, one-time assembly success and assembly time are the most important concerns of users. The AAS has a one-time assembly success rate of 90% and an average assembly time of 156 min/unit. Given the significant differences in the targeted aero - engines, it is infeasible to directly compare the AAS with existing research. Thus, this paper only conducts a comparative analysis between the AAS and manual assembly. Manual assembly largely depends on the operator’s experience and subjective judgment. Manual assembly mainly relies on operating experience and subjective judgment. When the LPTR is inserted into the aero-engine hole, it is difficult to ensure the insertion force. It will cause damage to the aero-engine hole machine spline and other parts. A total of 10 assembly tests, 9 are successful and 1 is a failure. The one-time assembly success rate of the manual assembly is about 70%. Compared with manual assembly, AAS for aero-engine assembly increases the one-time assembly success rate by about 28.57%. We carefully analyzed the reason for the failure because the micro camera incorrectly detected the position of the retaining ring spacer. There is no detection method set to detect the error. However, the subsequent tightening device conducted the normal tightening operation. The AAS uses the automated method for aligning the LPTR and the aero-engine holes during the assembly process, which can improve the accuracy of the assembly. In addition, the AAS employes automation for the LPTR assembly, which also improves the accuracy of the assembly. The average assembly time for the AAS is 156 min/unit, which reduced 84 minutes less per unit compared to manual operation. Therefore, the assembly efficiency of the AAS is significantly improved compared to manual operations.

In general, one-time assembly success rates and overall assembly efficiency show significant improvement compared to manual operations, primarily due to the integration of various sensor technologies. These sensors offer several key advantages: They provide precise measurement of component position and orientation, enabling accurate control of relative positioning during assembly. Real-time process monitoring through these sensors helps prevent assembly failures by detecting and responding to unexpected situations immediately. The visual feedback provided by sensors gives operators comprehensive real-time insights into the assembly process, facilitating faster and more confident execution. By quantifying critical parameters such as contact force and torque, sensors ensure consistent assembly quality across production batches, enhancing overall product reliability.

The kinematic modeling of the AAS assembly robots diverges from conventional methods. Instead of the coordinate-dependent D-H method commonly employed in robotics research, the AAS leverages position closure theory. Taking the alignment of the LPTR with the aero-engine shaft hole as an example, the LPTR spindle position must be precisely adjusted to match the shaft hole location. When employing the position-closure method, we analyze the kinematic relationships by directly correlating the movements of each device with the output position of the main shaft. By establishing equations based on geometric constraints, it becomes possible to determine the required actuator displacements and rotations. This approach simplifies the analysis process by avoiding the complexities inherent in the D-H method, such as repeatedly establishing multiple coordinate frames and performing extensive matrix multiplications at each step.This coordinate-free approach offers enhanced adaptability to geometric variations and results in more concise kinematic equations that directly reflect the robot’s structural configuration, simplifying both analysis and implementation38.

Accurate and reliable assembly of aero-engines necessitates precise detection of part attitude, contact force, and applied torque19. While laser trackers are conventionally used for part attitude detection, their susceptibility to accuracy degradation due to part movement and inherent inflexibility pose challenges. Vision-based methods are emerging as a promising alternative8, though ensuring consistent positioning accuracy remains a concern. To address these limitations and optimize assembly for both cylindrical aero-engine components and elongated LPTRs, a hybrid sensor approach is proposed. For aero-engine attitude determination, vision is employed to identify end faces, complemented by three laser distance sensors for precise spatial positioning. For LPTRs, optical grating transducers are utilized for dimensional measurement. Simultaneously, contact forces during LPTR insertion are critical, and while force sensors offer high accuracy and reliability for force measurement13, a six-dimensional force sensor is strategically implemented to capture both the magnitude and direction of contact forces. Finally, for large nut connections where preload is paramount for structural reliability, the limitations of solely relying on torque-preload linearity are acknowledged. To overcome this, a dynamic torque sensor, in conjunction with an angle sensor, is proposed to enable more robust and accurate preload control, particularly in regimes where the linear torque-preload relationship becomes unreliable25. This integrated sensor-based approach aims to enhance the precision and reliability of aero-engine assembly operations by strategically leveraging diverse sensing modalities tailored to specific measurement requirements.

Existing research on aero-engine assembly technology presents various limitations. Sun et al. examined turbofan engine assembly technology trends from a macro perspective, without addressing specific assembly system construction or parameter details1. Wang et al. proposed a vision-guided automatic assembly system for low-pressure turbine shafts, primarily focusing on vision sensing applications7. Wei concentrated on the structural and control system design of automatic bolt-tightening equipment for aero-engines, neglecting the comprehensive assembly process22. Feng et al. investigated industrial robot-based engine automatic assembly systems, which demonstrated insufficient performance in high-precision and complex assembly tasks due to limitations in robot versatility45. In contrast, the AAS proposed in this paper is specifically designed for aero-engine LPTR assembly tasks. It integrates multi-sensor fusion technologies including vision, laser ranging, optical gratings, dynamic torque, and angle measurements. The system establishes a kinematic model based on position-closed methodology and features optimized motion and control systems. Experimental validation demonstrates that the AAS achieves significant advantages in one-time assembly success rate (90%) and assembly time (156 min/unit), substantially enhancing system integrity, assembly process coordination, and precision and reliability for adapting to complex assembly conditions.

Consequently, the utilization of multiple sensors as described above enables safer aero-engine assembly processes. However, the employment of diverse sensor types introduces certain challenges in their control, particularly in aspects such as communication and debugging. Moreover, sensor calibration has emerged as a laborious task within the assembly operations. In future research, we will explore the integration of machine learning algorithms into the AAS. These algorithms will be utilized to analyze and model operational data collected from the system. By learning from extensive historical datasets, the machine learning models will be capable of identifying potential failure modes within the system and predicting failures before they occur. When anomalous patterns are detected, the system can automatically implement appropriate adjustments or trigger alerts, thereby enhancing the overall reliability and stability of the assembly process. This predictive maintenance approach represents a significant advancement toward intelligent manufacturing systems for aerospace components. Futhermore, we plan to undertake spindle assembly operations for various types of aeroengines, thereby further enhancing the applicability of the AAS. We will also establish a comprehensive dataset from the factory’s aero-engine assembly processes. Through statistical data analysis, this dataset will be used to evaluate the assembly performance of the AAS, analyze the causes of assembly failures, and provide empirical evidence for its further improvement.

Conclusions

The AAS is developed for LPTR assembly that integrates vision, laser distance sensors, optical grating transducer, dynamic torque sensor, and angle sensor. The overall structure, operation, and sensor system are described. Then, the kinematic model of the AAU is analyzed and the control system is presented. Furthermore, the tests are employed to validate the performance of the developed AAS. The test results showed that the one-time assembly success rate is 90%, which is 28.57% higher than that of manual assembly. The average assembly time is 162 minutes, which is about 35% shorter than that of the manual assembly. Hence, the AAS with multiple types of sensors can enable high-efficiency and high-quality aero-engine assembly operations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guiqing, S., Tong, W. & Yuhong, L. Advanced process and equipment for turbofan engine assembling. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 22, 72–77 (2017).

Song, D., Kan, Z. & Wenhe, L. Stability of lateral vibration in robotic rotary ultrasonic drilling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 145, 345–352 (2018).

Institution, B. S. Test code for machine tools: Part 2: Determination of accuracy and repeatability of positioning numerically controlled axes. ISO (2006).

Wang, L., Wang, D., Wang, B. & Li, W. Development of an oscillating grinding machine tool based on error analysis. Sci. China-Technol. Sci. 63, 912–922 (2020).

Guo, D., Han, Y. & Zhang, Y. Demand of aeroengine development for manufacturing technology. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 22, 68–72 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Robot positioning system for assembly of thin-walled rotating composite components of aero-engine. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 63, 42–49 (2020).

Wang, J., Chen, K., Jiang, L. et al. Research on automatic assembly system of aero engine low pressure turbine shaft based on visual guidance. Mach. Des. Res. 37, 94–100+104 (2021).

Liu, Y., Zhou, J. & Zhang, X. Application and prospect of additive manufacturing technology in manned space engineering. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 49, 83–91 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Analysis and prediction for spindle thermal bending deformations of a vertical milling machine. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 16, 1549–1558 (2020).

Xu, J., Lin, H. & Guo, H. Multi-layer wave-shaped topology and thermal design method for aero-electric propulsion motors. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 50, 1806–1818 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. A systematic development method for cyber-physical machine tools. J. Manuf. Syst. 48, 13–24 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Design and analysis of automatic tightening device for non-standard screw connection. In Mechanisms and Machine Science Vol. 155, 13–28 (2024).

Luo, M. et al. Investigation on the interface damage in drilling low-stiffness cfrp/ti stacks. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 32, 2211–2221 (2019).

Wang, D., Wang, L. & Wu, J. Physics-based mechatronics modeling and application of an industrial-grade parallel tool head. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 148, 107158 (2021).

Luo, M., Hah, C. & Hafeez, H. M. Four-axis trochoidal toolpath planning for rough milling of aero-engine blisks. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 32, 2009–2016 (2019).

Mu, X. et al. Feasibility analysis of the replacement of the actual machining surface by a 3d numerical simulation rough surface. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 150, 135–144 (2019).

Tingelstad, L. & Egeland, O. Robotic assembly of aircraft engine components using a closed-loop alignment process. In Procedia CIRP Vol. 23, 110–115 (2014).

Li, M. et al. Assembly accuracy prediction and optimization of aeroengine rotor under the separation condition of assembly and measurement. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 120, 3103–3112 (2022).

Jayaweera, N., Webb, P. & Johnson, C. Measurement assisted robotic assembly of fabricated aero-engine components. Assem. Autom. 30, 56–65 (2010).

Wang, H. Research on assembly technology of low pressure turbine rotor of aeroengine. J. North China Univ. Technol. 31, 77–83 (2019).

Shang, K. et al. Coaxiality prediction for aeroengines precision assembly based on geometric distribution error model and point cloud deep learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 71, 681–694 (2023).

Zhao, B. & Chen, L. Design of aero-engine rotor assembly simulation test system. Exp. Technol. Manag. 39, 114–117 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Research on optimizing-assembly and optimizing-adjustment technologies of aero-engine fan rotor blades. Adv. Eng. Inform. 51, 101506 (2022).

Ding, S. & Zheng, X. Variation analysis considering the partial parallel connection in aero-engine rotor assembly. Energies 15, 1–23 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Aero-engine rotor assembly process optimization based on improved harris hawk algorithm. Aerospace 10, 28 (2023).

Liu, J., Ma, C. & Wang, S. Data-driven thermal error compensation of linear x-axis of worm gear machines with error mechanism modeling. Mech. Mach. Theory 153, 104009 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. A method to minimize stage-by-stage initial unbalance in the aero engine assembly of multistage rotors. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 20, 193–207 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Establishment and application of the clearance fit joints model in rotor system assembly process of aero engine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 235, 176–186 (2021).

Wang, L., Wang, D. & Wang, B. Error compensation method of servo-axis of cnc machine tools based on markov predictive model. In Proceedings of 2019 Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-Paris) Vol. 19, 1–8 (2019).

Yan, B., Guo, H. & Yang, B. Numerical method of blade disk coupling torsional vibration considering the interface contact state. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 50, 1531–1537 (2024).

Xiaodong, H., Jin, X. & Huixu, D. A flexible positioning device for power turbine unit assembly (2020).

Xiaodong, H., Jin, X. & Lisheng, C. An automatic docking device and method for aero-engine component assembly (2020).

Tan, T. et al. Stiffness analysis and application of parallel manipulator tool head for robotic belt grinding. J. Manuf. Process. 86, 618–631 (2023).

Wang, T., Zhang, L. & Zhang, J. Dynamic response of rotating disk under electromagnetic force considering the effect of structural parameters. J. Vib. Control 28, 2632–2641 (2022).

Liu, N., Jiang, H. & Zhou, Y. Coupling effects of heat conduction and thermal expansion of adjacent thin-walled components for aeronautical engine assembly. J. Aerosp. Eng. 34, 04021079 (2021).

Altug, P. et al. Rotor balancing with turbine blade assembly using ant colony optimization for aero-engine applications. Int. J. Turbo Jet Eng. 38, 125–134 (2021).

Sun, Q. et al. Assembling deviation estimation based on the real mating status of assembly. Comput. Aided Des. 115, 244–255 (2019).

Hassen, N., Yun, H. C. & Doik, K. Analysis of parasitic motion with the constraint embedded jacobian for a 3-prs parallel manipulator. Mech. Mach. Theory 164, 104409 (2021).

Jochen, R. & Schwarz, S. Assessment of aero engine assemblability during preliminary design. In Procedia CIRP Vol. 57, 473–478 (2016).

Ai, Y. & Zhang, F. Application of principal component analysis in relational research between aeroengine assembly parameters and its vibration. In 2008 Fourth International Conference on Natural Computation Vol. 4, 95–99 (2008).

Shen, Y., Liu, Y., Zhou, F. et al. Research and application of aero-engine interface measurement technology. In 2021 International Conference of Optical Imaging and Measurement (ICOIM), 262–266 (2021).

Mei, Y. et al. Digital twin of large-scale coaxiality measuring instrument with six dimensions: Realizing the unification of aeroengine rotors measurement and assembly. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 20, 4504–4516 (2023).

Xue, W., Jianfeng, L., Ruxiao, C., Mengying, X. & Luyao, X. Research on design and planning of pulsating aero-engine assembly line based on plant simulation. In 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC) Vol. 1, 591–595 (2020).

Li, K. et al. A novel online chatter detection method in milling process based on multiscale entropy and gradient tree boosting. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 135, 106385 (2020).

Zhixin, F., Ligang, D. & Xuelei, W. Research of automatic engine assembly system based on industrial robot. In 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA) Vol. 3, 156–160 (2023).

Klocke, F. et al. Turbomachinery component manufacture by application of electrochemical, electrophysical and photonic processes. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 63, 703–726 (2014).

Xinwei, W., Hongxia, P., Heng, Z. & Xuehui, A. A diesel engine assembly quality detection method based on cross-point frequency response and static and dynamic information fusion. In 2022 Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-2022 London), 58–62 (2022).

Li, J. et al. A digital twin-based on-site quality assessment method for aero-engine assembly. J. Manuf. Syst. 71, 565–580 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Huixu Dong for his comments and to Hassen Nigatu for his kinematic analyses.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Aecc South Industry Company Limited, Turboshaft Engine Assembly Frame project. Grant Number: N-19120463.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Xiaodong Huang; Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Zhenyu Liu; Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Gaokun Shi; Visualization, Writing - review editing, Jianrong Tan.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Liu, Z., Shi, G. et al. Construction and performance verification of an automated assembly system for aero engine principal shaft enabled by multi sensor fusion. Sci Rep 15, 18822 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03142-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03142-0