Abstract

Plant biodiversity offers a valuable source of bioactive molecules to address critical global challenges including antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a major health threat. Wild edible plants (WEPs) have recently gained attention for their ability to accumulate specialized metabolites that are emerging for their efficacy against AMR. Although many studies suggest their potential use in combating infectious diseases, knowledge about the biochemical properties of these plants, their chemical profile and antibacterial activities, remains highly limited. In this scenery, the aim of this study was a bioprospecting of the chemical and antioxidant profile, the antibiofilm and bactericidal properties of six WEPs, largely distributed in Italy and historically used as food, namely: Silene alba, Silene vulgaris, Chenopodium album, Sonchus oleraceus, Glechoma hederacea and Diplotaxis erucoides. We applied an integrated approach, combining analytical chemistry, plant biochemistry and microbiology. These WEPs revealed notable antibiofilm and bactericidal abilities, anti-adherence and cell wall damage properties. These activities were strongly linked to the presence of phenolic compounds and to the antioxidant abilities of these plants. S. alba, S. oleraceus, and G. hederacea showed the highest efficacy. Our findings might encourage their consumption or use, which could improve dietary plant biodiversity, human health, and fight the rise of AMR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mediterranean countries hosts a huge plant biodiversity, with Wild Edible Plants (WEPs), also referred to as Phytoalimurgic plants, constituting a significant component1. These plants represent an important cultural heritage at regional level, and they have historically served as vital food resources during periods of famine, owing to their high content of micronutrients essential for human health2. Moreover, their documented resilience to climate change underscores their adaptive potential3. Recently the biodiversity of plant specialized metabolites4 (also known as secondary metabolites) has received growing attention as a promising source of new solution to today’s health challenges, such as the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) which poses a critical emerging global threat5,6. More and more frequently pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria are increasingly responsible for complications in the postoperative course of nosocomial infections, primarily due to the formation of bacterial biofilm, colonizing the implantable medical devices7,8. This issue is of particular concern for several reasons: i) modern medicine practices often involve immune suppression; ii) the misuse and overuse of antibiotics over the past five decades have accelerated resistance development; iii) the dietary imbalances prevalent in Western diets negatively affect immune health. Further, a recent study revealed that certain antidepressant drugs might exacerbate the development of AMR9. Additionally, climate changes, like the increase of temperatures, may contribute to the spread of AMR, as it has been recently suggested10,11.

Within this framework, phytotherapy may offer a promising adjunct to conventional antibiotics for the treatment of both susceptible and resistant strains of microorganisms.

In Italy and in other Mediterranean countries, the antimicrobial properties of WEPs are known since ancient times, and today a growing number of people are rediscovering them as natural remedies to the most common infections12,13.

The six WEP species examined in this work, namely Silene alba, Silene vulgaris, Chenopodium album, Sonchus oleraceus, Glechoma hederacea and Diplotaxis erucoides, have been described in ethnobotanical studies for their traditional use in rural regions (Table 1), mostly Mediterranean3, and for their known medicinal properties.

Previous studies have shown that extracts from S. alba14, S.vulgaris15, C. album16, S. oleraceus17 and G. hederacea18 display variable values of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) only against planktonic S. aureus. Differently, D. erucoides has been studied for its potential inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-219.

However, none of these plants was investigated for their capacity to inhibit Staphylococcus aureus wild type and Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) mature biofilm formation, nor for their potential to damage the bacterial cell wall. Notably, biofilm formation is an important virulence determinant, and allows bacteria to give rise to AMR colonies, even in opportunistic human pathogens20.

The discovery of new drugs from natural sources inevitably should rely on the application of a multifaceted approach, combining botanical, phytochemical, biological, and molecular techniques21. Therefore, in this work we further chacterized the overall metabolic and antioxidant profiles of six WEP species, along with their antibiofilm and antimicrobial properties. Antibacterial properties were thus connected to the chemical composition of each species, as well as their total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity.

This multifaceted bioprospecting highlighted that S. alba, S. vulgaris, C. album, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea possess notable antibiofilm and antimicrobial properties, which appear to be closely correlated with their phenolic composition and antioxidant activities. In contrast, D. erucoides and C. album, displayed only antibiofilm properties, consistent with their lower phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity.

This work could be included in the strategies for the valorization of WEPs, an essential activity to preserve edible plant biodiversity. In addition, these data might help improving the western eating habits and propose these species both as a daily diet healthy component, and as a valuable phytotherapeutic tool to contribute to counteract the onset of antibiotic-resistance in pathogenic bacteria.

Results

Total phenolic and ascorbate content

Although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, several phenolic compounds may have significant antibacterial properties, even though they are well-known for their antioxidant activity22. In this context, we monitored the content of total phenolic compounds in the considered plant extracts. The total phenolic content revealed that the extract obtained from G. hederacea leaves presents the highest phenolic content, followed by the extracts obtained from S. oleraceus and S. alba (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, S. vulgaris, C. album and D. erucoides showed low levels of total phenolic compounds, with S. vulgaris having the lowest amount. In particular, the phenolic content of S. vulgaris was approximately 6% of that observed in G. hederacea (Fig. 1a).

Antioxidant related analysis of the six WEPs extracts. a. Total phenol content (n = 5); b. Total ascorbate content (n = 5); c. DPPH scavenging capacity (n = 6); d. TEAC scavenging capacity (n = 6); e. FRAP scavenging capacity (n = 6); Values are means ± SD. Different statistical difference (p < 0.05) are based on Kruskal Wallis and Dunn’s Multiple comparison test.

The content of total ASC in the plant extracts revealed that S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea show significantly higher levels of total ASC in comparison to S. vulgaris, C. album and D. erucoides (Fig. 1b).

Antioxidant activity

The results of the antioxidant activity of the plant extracts determined as DPPH, TEAC and FRAP scavenging activity, are shown in Fig. 1c, d and e, respectively.

The three different methods employed reveled different antioxidant capacity among the six WEPs. This variation is expected, as each method is based on the scavenging capacity against different reactive species. The FRAP method measures the extract capacity to reduce ferric ion (Fe3+) to ferrous ion (Fe2+)23 while TEAC and DPPH methods assay the extract antioxidant capacity against a cationic radical and a free radical, respectively24. The antioxidant activity measured by DPPH assay ranged from approximately 22 to 2 μmol TE/g DW with S. alba, S. oleraceus, G. hederacea and S. vulgaris characterized by having the highest ABTS values and D. erucoides and C. album by the lowest ABTS values (Fig. 1.c). We observed the same trend by measuring the TEAC scavenging activity (Fig. 1d). In this case, the antioxidant activity ranged from approximately 100 to 10 μmol TE/g DW. S. alba, S. oleraceus, G. hederacea and S. vulgaris were characterized by the extracts with the highest antioxidant values, as opposed to C. album and D. erucoides which showed very low antioxidant activity measured by this assay (Fig. 1d).

The FRAP scavenging activity varied significantly among the plant extracts, ranging from approximately 135 to 5 μmol TE/g DW. As reported in Fig. 1e, the extracts from S. oleraceus and G. hederacea exhibited similar FRAP values, which were significantly higher (p < 0.0001) than those of the other plant extracts, with values of 133.54 μmol TE/g DW and 109.05 μmol TE/g DW, respectively. In contrast to these plant species, D. erucoides showed the lowest FRAP activity, measuring 5.53 μmol TE/g DW. Similarly, low FRAP values were observed in C. album, and S. vulgaris, while S. alba represented the intermediate boundary between the extracts with the lowest and the highest capacity to reduce ferric to ferrous ions (Fig. 1e).

Polyphenolic profiles

We initially analyzed the polyphenolic profile of the six species by UPLC-PDA. To assess the possible presence of polyphenol families in the extracts, we examined in detail the UV spectra of the obtained peaks. As it is shown in the PDA chromatograms reported in Fig. 2, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea are the species with the highest number of peaks (Fig. 2b and c), while in C. album and D. erucoides chromatograms the number and the intensity of the peaks are very low (Fig. 2e and f). These results were found to be consistent with the total phenolic content and antioxidant activities reported in Fig. 1 for the aforementioned species. On the other hand, both Silene species revealed the presence in each extract of a predominant compound along with other minor peaks (Fig. 2a and d), in accordance with the low total phenolic content (TPC) of both extracts (Fig. 1a) but not in agreement with their high antioxidant activities (Fig. 1c, d and e).

UPLC-PDA chromatograms of the examined extracts monitored at 320 nm. Quantified peaks are numbered as listed in Table 2. The chromatograms are shown with different labels on the y-axis to highlight both the more abundant compounds present in Silene alba and Sonchus oleraceus and the lower amount of polyphenols present in the Glechoma hederacea, Silene vulgaris, Chenopodium album and Diplotaxis erucoides extracts compared to the two species described above.

Based on these results, we performed a more in deep characterization of the polyphenolic profile using LC-HRMS only in S. alba, S.oleraceus, G. hederacea and S. vulgaris (Table 2). However, by carefully studying the UV spectra of each peak in the chromatograms of C.album and D.erucoides, it can be assumed the presence in these extracts of compounds belonging to the class of phenolic acids, flavanols and flavones, but in significantly lower concentrations as compared to the other four species (Fig. 1a, Fig. 2e and f).

LC-HRMS analysis highlighted that in S. alba and S. vulgaris the most intense peaks were isovitexin 2"-O-glucoside and vitexin, respectively (Table 2a and d). Most of the other compounds identified in both Silene extracts were apigenin derivatives (as isovitexin 2"-O-glucoside, vitexin, etc.) or luteolin derivatives (as isoorientin, etc.), all belonging to the flavonoid class, in accordance with the recent findings of Jakimiuk et al. (2022)25, who reported the flavonoids as the main bioactive compounds contained in Silene species14,25. According to these authors, mainly flavones were identified in the examined Silene extracts, although a small quantity of flavanols were also found in S. alba extract (Table 2a).

Concerning Sonchus oleraceus, we identified 18 compounds, including phenolic acids and flavonoids. Among flavonoids, we detected quercetin and kaempferol derivatives (flavanols) as well as luteolin and apigenin related compounds (flavones) (Table 2b). These results are in line with the literature data26,27, although we found differences in the amounts of the individual compounds. Actually, quantitative analysis revealed the presence of large amount of chicoric acid, quercetin-3-glucoside and neo-chlorogenic acid in the extract under investigation. The reason for these differences is likely to be that the occurrence of secondary metabolites in plants is influenced not only by the plant species but also by the harvesting season, geographical area of the sampling, differences in climatic conditions and in the nature of soil where the plants have grown. Moreover, the extraction procedure, the drying process and the storage of plants also play a key role in their phytochemical profile.

In the Glechoma hederacea extract, we identified 12 phenolic compounds (Table 2c), all belonging to the phenolic acids and flavanols families. Quantitative data highlighted the presence in the extract of significant quantities of chlorogenic acid and its isomers whereas rutin alongside quercetin and kaempferol derivatives were some of the detected compounds among the flavanols family. As in the case of S. oleraceus, the reported data is in line with the literature data but with some differences due to the reasons stated above28.

Biofilm inhibiting capacity

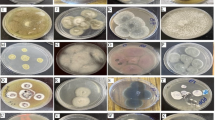

We then wanted to ascertain whether the hydroalcoholic extracts of the six WEP species displayed anti-biofilm properties on S. aureus sessile growth, being the biofilm formation the crucial step to give raise to AMR. We determined the Minimal Biofilm Inhibiting Concentration (MBIC) of the six extracts on S. aureus wild type attached culture, as shown in Fig. 3.

Mature biofilm inhibiting capacity of the six WEPs extracts vs S. aureus wild type, ATCC 25923. For all the six extracts, the MBIC inducing the highest biofilm reduction was 0.25 mg/mL. This MBIC induced roughly a fourfold biofilm reduction for all the species but G. hederacea, which induced a 2.0-fold biofilm reduction. n = 5. Effect of the extracts: Left axis label (black color) reports the biofilm fold-reduction values vs the solvent, to subtract the effect, even if minimal, of the solvent used for the extracts. Effect of Solvent, Gentamicin and Rifampicin: right axis label (blue color) reports biofilm fold-reduction, respective values of 1.0-, 0.8- and 0.7-fold, vs the untreated bacteria, inside the dashed blue frame. We used Gentamicin and Rifampicin at MIC values of 5 µg/ml. Different statistical difference (p < 0.05) are based on Mann Whytney U test.

We allowed the biofilm to develop for 96 h to obtain a mature biofilm, which is the most difficult form of bacterial growth to eradicate29, given the self-produced matrix composed of extra-cellular polymeric substances stratified over time.

For all the six extracts, the MBIC inducing the highest biofilm reduction was 0.25 mg of dry extract/mL of solvent (left axis label reports the biofilm fold-reduction values vs the solvent (Ethanol 60%), to subtract the effect, even if minimal, of the solvent used for the extracts). This MBIC induced roughly a fourfold biofilm reduction for all the species but G. hederacea, which induced a twofold biofilm reduction.

To exclude any antimicrobial activity of the solvent, we calculated the biofilm fold-change induced by WEPs extracts vs the solvent, which did not induce any change when used alone (1.0-fold vs untreated bacteria, right axis label (blue color) reports the biofilm fold-reduction values vs the untreated bacteria). The effect of Gentamicin and Rifampicin (biofilm fold-reduction values of 0.8- and 0.7-fold reduction vs the untreated bacteria, used at MIC of 5 μg/ml) was much less pronounced in comparison with that induced by the WEPs extracts (Fig. 3).

MIC and MBC

We then carried out the MIC and MBC determination of the six WEPs hydroalcoholic extracts on S. aureus wild type and MRSA strains in planktonic growth, to ascertain their efficacy in bacteria growing in liquid culture media. We analyzed a range of concentrations from 0.5 to 2.8 mg of dry extracts/mL of solvent.

The achieved results (Table 3) highlight that S. alba and S. vulgaris were, respectively, the most and the least effective extract, among the four species that exhibited inhibiting and bactericidal power.

The other two WEP species, C. album and D. erucoides, did not display antimicrobial properties over the range of concentrations tested. In particular, the highest concentration tested (2.8 mg of dry extracts/mL of solvent) was equivalent to that of the undiluted extracts of C. album and D. erucoides.

Cell wall damage evaluation

In order to assess whether the extracts antibiofilm and bactericidal effects could be due to a damage to the bacterial cell wall, we used the Propidium Iodide (PI) staining of the WEP-treated bacteria. PI staining is not a vital one, since it is not able to enter in viable bacterial cells, with an intact cell wall30. On the contrary, in killed bacteria, it passes through injured cell membranes and stains the nuclei31. According to numerous studies, PI positive staining indicated damaged plasma membranes31,32. In Fig. 4b. we show, again, that the three extracts with the greater antibacterial activity (S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea), used at the MIC concentration, caused the higher cell wall damage, whereas there was no impact on the cell wall of untreated bacteria, or bacteria treated with the solvent (Fig. 4a). The other three WEPs extracts (S. vulgaris, C. album and D. erucoides, Fig. 4c) caused a much smaller cell wall damage. The analysis of mean fluorescence confirms a strong differences between the most and lowest active species, by setting a cut off the mean fluorescence value at 10,000 (Fig. 4d).

MRSA Bacterial Cell wall damage evaluation by Propidium Iodide staining. The phase contrast of the wells is on the left panel, and the fluorescence signal is on the right panel for each line. a. untreated bacteria (upper panel) and bacteria treated with solvent (lower panel); b. bacteria treated with S. alba (upper panel), with S. oleraceus (middle panel) and G. hederacea (lower panel) extracts; c. bacteria treated with S. vulgaris (upper panel), C. album (middle panel) and D. erucoides (lower panel) extracts; d. mean fluorescence values of the samples. n = 6 for Solvent and Untreated bacteria, and n = 4 for all the others datasets. Different statistical difference (p < 0.05) are based on Kruskal Wallis and Dunn’s Multiple comparison test.

Anti-adherence properties of the six WEPs hydroalcoholic extracts

We performed a Zone Of Inhibition (ZOI) agar-based assay33 in order to assess whether the observed anti-biofilm effect could be due to the anti-adherence effect of the WEPs extracts. This assay was performed to ascertain whether the WEPs extracts administration, at a reduced MIC (1/50 of the MIC value), might be able to inhibit the initial S. aureus and MRSA bacterial adhesion to a substrate, which is the very early step for the following biofilm formation34. The analyses performed on the six species confirmed that S. vulgaris, C. album and D. erucoides did not induce an anti-adherence effect (data not shown), while G. hederacea, S. alba and S. oleraceus induced a clear anti-adherence effects.

In Fig. 5, we show that the extracts of G. hederacea, S. alba and S. oleraceus induced the higher ZOI in the growth of both S. aureus and MRSA. The mean inhibition halos diameter in the three experiments performed was, for G. hederacea, 19 mm vs S.aureus and 15 mm vs MRSA; for S. alba, 15 mm vs S. aureus and MRSA and, for S. oleraceus, 18 mm vs S. aureus and 20 mm vs MRSA.

It is interesting to note that this result is coherent with that of the MIC-MBC assessment, in which the very same three species displayed the most powerful effect on the bacterial planktonic growth (Table 3). It is also worth noting that, in this case, the effective extract concentration is rather low, being it 1/50 of the MIC value, suggesting that a smaller amount of plant extract is needed to induce an adherence inhibition zone on MH agar plate, as compared to the inhibition of planktonic growth at 24 h in liquid culture.

Disc-diffusion assay and antibiotic bacterial resistant colonies occurrence

We then used the disc-diffusion assay to assess the growth inhibition diameter induced by the three most bactericidal and adhesion-inhibiting WEPs extracts (Fig. 6a). To gain a better understanding of the results of co-administration with the selected antibiotics, we decided to reduce the MIC value of the extracts by half (1/2 MIC).

MRSA ZOI pattern after administration of S. alba, G. hederacea and S. oleraceus WEPs Extracts, both alone or in combination with the two Antibiotics to which the S.aureus wild type and MRSA resulted resistant (Ampicillin and Amoxicillin, see Figure S1). a. picture of a representative experiment, out of three, of the growth inhibition diameter induced by the three extracts alone at 1/2 of their MIC (blue line), or in combination with Ampicillin and, respectively, Amoxicillin (red line); the administration of each antibiotic alone is indicated by a grey line. b. different statistical differences are based on Kruskal Wallis, p < 0.05, with particular attention to Antibiotics (n = 9) vs Antibiotics plus Extracts (n = 3) inhibition diameter lengths; c. appearance of ABR colonies, after 120 h, between Antibiotic alone (Ampicillin), and Antibiotic co-administration with Extracts. The green drop drawing indicates the extract administration on the Antibiotic disc.

We selected the antibiotics by searching The Antimicrobial index Site (https://antibiotics.toku-e.com/#:~:text=The%20Antimicrobial%20Index%20is%20a,worldwide%20scientific%20community%20at%20large) for drugs with a known MIC and MBC on S. aureus. We then used Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Discs with Ampicillin (30 μg/disc) and Amoxicillin (10 μg/disc) at their respective MIC value for S. aureus 25923, the two antibiotics to which the two S.aureus strains resulted resistant (see Figure S1).

For each WEP extract, on the same agar plate, we compared the growth inhibition diameter induced by the extract (blue line), by the Antibiotic (grey line), and by the co-administration of the extract on the antibiotic disc (red line). The graph in Fig. 6b shows the values of the subtraction of the blue circles (only extract) from the red ones (extract plus antibiotic).As shown in Fig. 6a, all the three extracts co-administration with antibiotics increased the growth inhibition diameter (ranging from 21 to 54% increase in mm), as compared with the extract, or the antibiotic, when administered alone (Table 4a). Although we cannot define this result a proper synergy, it might suggest that the extracts co-treatment with the antibiotics could have made S.aureus and MRSA bacteria more susceptible to these drugs, as shown by the statistical analysis in Table 4a.

We then wondered also whether the inhibition zones contained bacteria that were either inhibited or killed. To this end, we plated the agar, collected inside the inhibition zones (Figure S2b), on a fresh MH agar plate, without any compound.

Concerning S. alba and G. hederacea, the bactericidal effect prevailed in the co-administration (no bacterial growth was already evident with the extract alone, after 24 h on a fresh plate), whereas, regarding S. oleraceus, the co-administration strengthened both the extract (with which few CFU were present in extract alone fresh plate) and the Antibiotics (where bacterial growth was evident when they were administered alone, after 24 h on a fresh plate, Table 4b).

Finally, after 120 h culture, we determined the possible occurrence of ABR colonies in MRSA, in Antibiotic vs Extract-Antibiotic treated bacteria. As it is shown (Fig. 6c), in the case of Ampicillin, after 120 h of culture, the growth inhibition zone was recolonized by Amp-Resistant MRSA bacteria. Differently, no bacterial colonies were found in the combination of the extracts (green drop) with Amp on the very same disc, thus confirming that death of the bacterial cells treated with the hydro-alcoholic WEPs’ extracts.

Discussion

Plant specialized metabolites, commonly referred to as phytochemicals, are emerging for their effectiveness in combating antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens35. Recent research has shifted focus from the health properties of individual bioactive metabolites to the potential of phytocomplexes, where diverse secondary metabolites act synergistically to exert a therapeutic effect, including antioxidant or anti-inflammatory activities36. Our study embraced the latter type of approach, aiming to reveal the healthy features of these WEPs, inspired by the concept of food synergy37. By providing a comprehensive profile of these WEPs, we intended to encourage the increase of their consumption in the daily diet and to promote their potential as adjuvant to antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial infections.

Medicinal plants have been reported to inhibit both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Furthermore, their composition, consisting of hundreds of different molecules makes it challenging for bacteria to develop resistance to these natural compounds. In addition, their antioxidant properties have a positive effect on the human immune system, enhancing its ability to combat infections38.

In this scenario, we outlined the whole antimicrobial and phytochemical profile of six WEPs hydro-alcoholic extracts, among which the ethanolic extracts of S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea showed remarkable antimicrobial properties against S. aureus and MRSA, both in planktonic culture and in mature biofilm. This is what makes them so interesting, because bacteria do not always respond equally to antimicrobials in both growth modes. All six WEPs hydro-alcoholic extracts demonstrate a higher efficacy in reducing biofilm formation compared to the antibiotics Gentamicin and Rifampicin (Fig. 3). The limited effectiveness of Gentamicin and Rifampicin in reducing biofilm formation is unsurprising, given the significantly higher level of antibiotic resistance in biofilm than in younger sessile cultures39. A more detailed investigation into the effects of the hydro-alcoholic extracts of the six WEPs on S. aureus and MRSA revealed that S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea exhibit stronger antimicrobial effects than the other three species. Specifically, these extracts induce a higher MRSA cell wall damage than the other species (Fig. 4) and display clear anti-adherence properties (Fig. 5), whereas the other three species do not alter the bacterial adherence capacity (not shown). Interestingly, preventing bacterial adhesion to surfaces is the critical first step in avoiding biomaterial-associated infections34. Moreover, S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea also demonstrate a clear bactericidal effects, with bacterial colonies treated with their hydro-alcoholic exhibiting reduced antibiotic resistance (Fig. 6c).

For three out of the six species (S. alba, S. vulgaris and D. erucoides) this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study analyzing their antimicrobial properties vs MRSA.

Glechoma hederacea has been previously studied, but only against S. aureus wild type strains, where it was found to be either inactive as industrial tincture40 or bacteriostatic as a fractionated aqueous extract41.

This underlines the complexity of comparing extracts obtained through different extraction methods.

S. oleraceus was only tested against S. aureus42, while only one study43 employed a fractionated extract against a clinical isolate of MRSA.

An apparent paradox occurs for C. album, a widely studied WEP species, compared to the other five species examined in our study44. In the literature, C. album was described as antibacterial only against S. aureus16.

Differently, in our experiment, C. album did not show similarly strong antibacterial activity. However, previous studies on C. album utilized a different solvent and used plants harvested from diverse countries, including South Africa, India and the inland area of Kilis in Turkey. Otherwise, our C. album samples were harvested in the Mediterranean region of central Italy, characterized by a more temperate climate. It is known that climatic conditions during plant growth, as well as the timing of harvest, strongly influence the phytochemical composition and the content of antioxidant molecules, which in turn influence the antimicrobial properties.

The comparison of antioxidant properties, total phenolic content and phenolic profiles of the six WEPs provides insight into their antimicrobial capacity. Phenolic compounds in S. oleraceus and G. hederacea, two of the three most effective WEPs, were significantly higher, both in quantity and diversity, compared to the other examined species (Table 2a,b,c,d). These species were characterized by the presence of various polyphenols classes like phenolic acids, flavonoids and flavones.

These findings are consistent with the high antioxidant and antimicrobial properties showed by these plants (Fig. 1c-e, Figs. 3,4,5,6). Notably, both extracts contained chlorogenic acid, a polyphenol that has recently been shown to disrupt the S. aureus outer membrane and increase both outer and plasma membrane permeability45. This increased permeability could have easily played a role in the cell wall damage induced by the extracts of these two species (Fig. 4).

On the other hand, the low TPC observed in both the analyzed Silene species is not in accordance with their high antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, particularly in the case of S. alba, one of the three species exhibiting the strongest antimicrobial properties. It is important to note that there are significant differences in both the specific phenolic compounds present and their concentrations between the two Silene species (see the different scale in Fig. 2 and Table 2).

In these species the most active phenols might be apigenin and luteolin derivatives (as isovitexin 2"-O-glucoside, vitexin, isoorientin, etc.) which are known to have very high biological activities (anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties)46,47. In particular, Luteolin48 was reported able to destroy the integrity of the cell membrane and to possess a strong inhibitory effect on the biofilm formation. A recent study on the properties of a Cajanus cajan extract49, found that the presence of various isovitexin derivatives in the extract was associated with the death of S. aureus bacteria, as evidenced by PI staining analysis. Thus, isovitexin-associated PI positive staining confirms cell wall damage and subsequent permeabilization. Interestingly, isovitexin is the main peek present in S. alba (Fig. 2, Table 2).

In Silene, as well as in the other WEPs species, it cannot be excluded that other specialized metabolites contribute to the observed antimicrobial properties.

Notably, the tree most active WEPs are characterized by higher level of ASC and a greater capacity to reduce ferric to ferrous ions compared to the other three species (Fig. 1b and e). In the last years, several papers have highlighted the antibacterial effects of ASC, which can modify the antimicrobial activity of various antibiotics50. In addition to its antioxidant properties, ASC can also act as pro-oxidant. Ferric ions are involved in the Fenton reaction, one of the most dangerous spontaneous reaction occurring in aerobic environment that produces toxic oxygen-derived radical species51. Therefore, the elevated levels of ASC and ferric ion production may contribute to the antimicrobial properties of the three most effective WEPs.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, Chenopodium album and Diplotaxis erucoides did not display a great biological activity, except for bacterial biofilm inhibition. According to this outcome, both extracts showed low TPC and lower antioxidant activities compared to the other analyzed extracts (Fig. 1). Moreover, Figs. 1 and 2 clearly shows that these two extracts have a very low content of phenolic compounds.

As suggested by the concept of food synergy37,52,53, we suppose that there is a relationship between the different phytochemical groups identified and the antimicrobial activity of the analyzed WEPs extracts.

Conclusion

In Fig. 7, we grouped all the findings of this study, to identify a common trait that could potentially classify an antimicrobial plant extract. At a first glance, the presence of active polyphenols, the ascorbate content and the iron reducing capacity seems to be related to the ability of causing adhesion inhibition and cell wall damage to S. a. and MRSA. This trait characterizes the three most antimicrobial WEPs species S. alba, S. oleraceus and G. hederacea. The bactericidal effects of the hydro-alcoholic extracts and their capacity of reducing antibiotic resistance make these WEPs of particular interest.

Summary picture of the properties displayed by the six WEPs species, in decreasing order of bactericidal power, determined by MIC-MBC assay and polyphenols UV absorbance at 320 nm. In green, we annotated the extracts displaying: a) an MBIC = 0.25 mg/mL; b) a MIC < 2.8 mg/mL; c) an MBC ≤ 2.8 mg/mL; d) a disc-diffusion and e) an anti-adherence inhibition halos ≥ 10 mm; f) an IP stain with the mean fluorescence signal > 10,000; g) a total Ascorbate ≥ 6 nmol/g DW; h) a FRAP and a i) TEAC assay ≥ 50 μmTE/g DW and a l) DPPH assay ≥ 10 μmTE/g DW.

It is also worth noting that all the six extracts inhibited the S. aureus mature biofilm, supporting the established knowledge that the bacterial cell wall composition of the sessile growth is very dissimilar in respect with the planktonic one,39. To cite some studies, Williams39describes significant physiological adaptation occurring the early phase of the attached growth, like bacterial colony size, protein content, which are smaller in attached vs planktonic S. aureus cultures. Belley reported that the lipoglycopeptide Oritavancin sterilized biofilms of MSSA, MRSA, at minimal biofilm eradication concentrations (MBEC). Importantly, MBECs for Oritavancin were within 1 doubling dilution of their respective planktonic broth MICs. The study also showed that the attached culture displayed a lower membrane potential as compared with the planktonic one54. Another previous study characterized the composition of attached and planktonic bacterial culture composition, showing that the first is composed by 10% of viable cells, and the second is close to 100% viable cells55.

These differences, among others, might explain the reported diverse response of biofilm and liquid culture of bacteria to the very same extract of Chenopodium album and Diplotaxis erucoides. We might figure out that these two species, that we found poorer of phenolic compounds than the other four species, evidently contained enough specialized metabolites to affect, at a low concentration (1/20 MIC), the mature bacterial biofilm (96 h), mostly composed of non-viable cells.

However, in future studies such a finding will deserve further examination of the bacterial cell wall integrity and the cell membrane permeability upon treatment with our WEPs extracts. Furthermore, it will be useful to analyze whether these WEPs extract induce ROS generation in treated bacteria.

Finally, the three most efficacious species are still largely used in Italian regional recipes, hence our results might well encourage their further consumption, thus improving dietary plant biodiversity and contributing to the maintenance of human health and the contrast of bacterial ABR insurgence.

This work could actually help promoting the valorization of WEPs, an essential activity to preserve edible plant biodiversity. In addition, these data might help improving the western eating habits and propose these species as, both, a nutraceutical for the daily diet and a valuable phytotherapeutic tool to counteract the onset of antibiotic-resistance in pathogenic bacteria.

Methods

Plant materials

S. alba, S. vulgaris, C. album, S. oleraceus, and G. hederacea were kindly provided by the Phytoalimurgic Garden in Veneto Region, Padua University. Diplotaxis erucoides was harvested in the Garden of Simples (http://www.isb.cnr.it/orto-dei-semplici/) and identified according to EuroMed PlantBase (https://europlusmed.org). The six WEPs species analyzed in this study are listed in Table 1. All of them are edible and known as medicinal wild herbs, as annotated by the Acta Plantarum botanical website (https://www.actaplantarum.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=14081; 47,922; 83,179; 3300; 7645; 5732). The aerial part of each species is shown in Suppl. Mat. Figure S1.

Preparation of plant extracts

Stems and leaves of the plants were chopped under liquid N2 and then macerated in 60% ethanol–water at a 1:5 plant to solvent ratio for 15 days at room temperature in the dark, according to the method reported in European Pharmacopeia in 200656 (EMA, 2006).

Notably, plants material (20 g) was macerated with 100 mL of the hydroalcoholic solvent.

The extract was then filtered using a sterile cotton tissue, sterilized using a 0.22 μm Polyethersulfone (PES) filter and then stored at – 80 °C until use. Aimed at determining the extract amount per mL of solvent, a precise aliquot (1 mL) of each one was freeze-dried after ethanol removal under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

Total phenolic content and ascorbate quantification

Total phenolic content was assayed according to the Folin–Ciocalteau method57, with minor modification, using gallic acid as standard. A volume of 1580 µL of a mixture of methanol/water (50:50) and 100µL of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent were added to 20 µL of sample extract (or standard solution) and incubated at room temperature for 8 min. Then, 300 μL of Na2CO3 (20%w/v), were added. The solution mixture was incubated for 2 h in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance at 765 nm, was measured in a 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany) using a multifunctional microplate reader (Tecan Infinite M200PRO multiplate reader, Männedorf, Switzerland). The results are expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g of dry weight (DW). Total ascorbate content (reduced and oxidized forms) was measured according to Cimini et al.58. In both cases, three biological replicas were carried out, and for each biological replicate, at least three technical replicates were made.

Antioxidant capacity assays

For all antioxidant assays, the extract was centrifuged at 14,000 × g (rcf) for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was collected. For the experiments, three biological replicas were carried out, and for each biological replicate, at least three technical replicates were made. Results are expressed as µmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per g of dry weight.

DPPH (1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay was analyzed as previously reported by Tonto et al. (Tonto et al., 2023)59. Trolox was used as a standard for calibration curve construction in the range of 10–200 mg L−1.

FRAP (Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power) assay was based upon the methodology previously described by Tonto et al.59. Trolox was used as a standard for calibration curve construction in the range 20–200 mg L−1.

TEAC (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity) assay was evaluated as previously described by Tonto et al.59 (Tonto et al., 2023). Trolox was used as a standard for calibration curve construction in the range of 10–700 µM.

LC-HRMS analysis

An Agilent 1290 UHPLC system coupled to a Thermo Fisher Q-Exactive Focus Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (HESI) interface was employed for the plant extracts analysis. Samples were injected (2 µL) and chromatographically separated using a reversed-phase C18 HSS T3 ACQUITY column 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm particle size (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). A gradient profile was applied using water (eluent A) and acetonitrile (eluent B), both acidified with 0.1% formic acid as mobile phases. A multi-step elution dual-mode gradient was developed as reported in Supp. Mat. The column was maintained at 60◦C and a flow rate of 0.40 mL/min was used.

The extracts were analyzed both in positive and negative ionization mode with a DDA approach: positive and negative scan spectra were acquired in a range from 66,7 to 1000 m/z, the full MS resolution was 70,000 FWHM, AGC target 3e6, maximum IT 200 ms and with a profile spectrum data type. Additional information on the HESI source settings, LC-HRMS data analysis and quantification of the main phenolic compounds can be found in Supplementary material.

Bacterial strains and mature biofilm formation

We determined the WEPs extracts antibiofilm activity on mature biofilm of collection strains of Staphylococcus aureus (S.aureus or S. a.) wild type, ATCC N°25923, and Methicillin-resistant S. a. (MRSA), ATCC N° 33591, in a BSL2 laboratory, as previously shown60, see Supp. Mat. Briefly, S. a. and MRSA biofilms were left to grow for 4 days at 37 ◦C. On the fifth day, the wells were emptied, washed with PBS and the WEPs extracts were added at concentrations ranging from 2.8 to 0.25 mg dry extract/ml. The plates were then left at 37 ◦C overnight and the biofilm formation was observed the following day. Each plate contained untreated bacteria, as positive control, and Mueller–Hinton broth without bacteria, as negative one. We analyzed each experimental condition in triplicate.

Crystal violet and demolition assay on S. aureus biofilm

We measured the biofilm demolition on 96 wells/plate (flat bottom) by Crystal Violet (CV) assay, as previously shown60 (see Supp. Mat.). On the fifth day of culture, we proceeded as previously shown. Briefly, the wells were washed again with PBS before 100 μl of 0.1% CV solution were added. After 45 min at room temperature, the plates were emptied and washed with distilled water to remove excess CV. For biofilm quantification, 50 μl of 95% ethanol were added to the wells to solubilize all biofilm-associated dye and the absorbance at 630 nm was determined using a microplate reader. We analyzed each experimental condition in triplicate.

Minimal inhibiting concentration (MIC)-Minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) determination

To assess the MIC and MBC values of the six WEPs extracts, we used the microdilution assay61. The six hydroalcoholic extracts were used in a concentration range between 0.5 and 2.8 mg of dry extracts/mL of solvent (see Supp. Mat.). Briefly, the supernatant from transparent wells, cultured for 20 h in MH broth, was collected on a plastic tube and used for the MIC-MBC assay. Samples were serially diluted in PBS/0.05% Tween 80 and 20 μL drops were applied to MH agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C to determine CFU number. Each plate contained untreated bacteria, as positive control, and Mueller–Hinton broth without bacteria, as negative one. We analyzed each experimental condition in triplicate.

Bacterial cell wall damage assay by propidium iodide uptake

We put the S. aureus and MRSA strains in culture for 16 h in a Chamber Slides (1 μ-Slide 8 Well IbITreat, IBIDI GmbH, Germany) with the extracts at the respective MIC value. The following day, a Propidium Iodide solution (1 mg/mL, Invitrogen) was added in each Chamber slide well, at the final concentration of 1 μg/mL. After 5 min staining, we analyzed the samples by a fluorescent microscope with an Olympus FV1200 confocal laser scanning microscope, as previously shown60 (see Supp. Mat.). Each plate contained untreated bacteria, as positive control, and Mueller–Hinton broth without bacteria, as negative one. We analyzed each experimental condition in triplicate.

Anti-adherence and disc-diffusion assay

We spread on Muller-Hinton (MH) agar plates 500 μL of S. aureus and MRSA cultures, adjusted to an approximate cell density 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL, and dried them under the sterile flow bench for 15 min. We then dropped 10 μL of the WEP extracts (at 1/50 of the MIC value identified) on the inoculated agar surface and dried them as previously described33. To exclude the solvent contribution to the inhibiting effect, we also dropped 10 μL of the solvent on a control plate (negative control). Finally, we incubated the plates for 16 h at 37 °C. The anti-adherence activity was expressed as the mean of the diameter of inhibition halos (mm) produced by each extract. We did not used a positive control, given that an empty sterile disc could not induce any growth inhibition diameter. Blue circle indicates the growth inhibition diameter induced by each extract; grey indicates the growth inhibition diameter induced by the Antibiotic, and red circle the one induced by the co-administration of the extract on the antibiotic disc. We then measured the values of the subtraction of the blue circles (only extract) from the red ones (extract plus antibiotic).

The disc-diffusion assay was performed following Kirby-Bauer protocol62, using the Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Discs (ASTD) Kairo-Safe (TS, Italy). We analyzed each experimental condition in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using the software GraphPad Prism version 5.0 and Stata software. Data were analyzed by Kruskal Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test and Mann Whytney U comparison test (p < 0.05).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin susceptible S. aureus

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin resistant S. aureus

- MBIC:

-

Minimal biofilm inhibiting concentration

- MIC:

-

Minimal inhibiting concentration

- MBC:

-

Minimal bactericidal concentration

- WEP:

-

Wild edible plant

- ATCC:

-

American type culture collection

- TPC:

-

Total phenolic content

- TEAC:

-

Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity

- DPPH:

-

2 2 Diphenyl 1 picrylhydrazyl

- FRAP:

-

Ferric reducing antioxidant power

- ASC:

-

Ascorbate

- BSL2:

-

Bio safety level 2

- UPLC-PDA:

-

Ultra high performance liquid chromatography-photodiode array detector

- LC-HRMS: :

-

Ultra high performance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry

References

Ciancaleoni, S. et al. A new list and prioritization of wild plants of socioeconomic interest in Italy: toward a conservation strategy. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 45, 1300–1326. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.1917469 (2021).

Zuin, M.C., Zanin, G. Il Giardino Fitoalimurgico per la valorizzazione delle piante spontanee. Agribusiness Paesaggio e Ambiente. IX (1). http://hdl.handle.net/11577/2274889 (2006).

Bacchetta, L. et al. (on behalf of the Eatwild Consortium). A manifesto for the valorization of wild edible plants. J. Ethnopharmacol 191, 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.061 (2016).

Wang, M., Zhang, S., Li, R. & Zhao, Q. Unraveling the specialized metabolic pathways in medicinal plant genomes: a review. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1459533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1459533 (2024).

Ismail, S., Masi, M., Gaglione, R., Arciello, A. & Cimmino, A. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of specialized metabolites isolated from Centaurea hyalolepis. Peer J. 12, e16973. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16973 (2024).

O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. (2016) The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance Wellcome Trust and HM Government. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf

Materazzi, A. et al. Phage-Based Control of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Galleria mellonella Model of Implant-Associated Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 14514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314514 (2022).

Ciofu, O., Rojo-Molinero, E., Macià, M. D. & Oliver, A. Antibiotic treatment of biofilm infections. APMIS 125, 304–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12673 (2017).

Ding, P., Lu, J., Wang, Y., Schembri, M. A. & Guo, J. Antidepressants promote the spread of antibiotic resistance via horizontally conjugative gene transfer. Environ Microbiol. 24, 5261–5276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.16165 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Association between antibiotic resistance and increasing ambient temperature in China: An ecological study with nationwide panel data. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 14, 100628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100628 (2022).

MacFadden, D., McGough, S., Fisman, D., Santillana, M. & Brownstein, J. Antibiotic Resistance Increases with Local Temperature. Open Forum Inf. Dis. 4(1), S179 (2017).

Heinrich, M. & Prieto, J. M. Diet and healthy ageing 2100: will we globalise local knowledge systems?. Ageing Res. Rev. 7, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.002 (2008).

Lone, B. A. et al. Evaluation of anthelmintic antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of Chenopodium album. Trop Anim. Health Prod. 49, 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1364-y (2017).

Zengin, G. et al. Functional constituents of six wild edible Silene species: A focus on their phytochemical profiles and bioactive properties. Food Biosci. 23, 75–82 (2018).

Gatto, M. A. et al. Activity of extracts from wild edible herbs against postharvest fungal diseases of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 61, 72–82 (2011).

Akgunlu, S. Research on selected wild edible vegetables: Mineral content and antimicrobial potentials. Ann. Phytomed-An Int. J. 5, 50–57 (2016).

Petropoulos, S. A. et al. Bioactive compounds content and antimicrobial activities of wild edible Asteraceae species of the Mediterranean flora under commercial cultivation conditions. Food Res. Int. 119, 859–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.069 (2019).

El-Aasr, M. et al. LC-MS/MS metabolomics profiling of Glechoma hederacea L. methanolic extract; in vitro antimicrobial and in vivo with in silico wound healing studies on Staphylococcus aureus infected rat skin wound. Nat. Prod. Res. 9, 1–5 (2002).

Guijarro-Real, C., Plazas, M., Rodríguez-Burruezo, A., Prohens, J. & Fita, A. Potential In Vitro Inhibition of Selected Plant Extracts against SARS-CoV-2 Chymotripsin-Like Protease (3CLPro) Activity. Foods 10, 1503–1515 (2021).

Roy, S., Chowdhury, G., Mukhopadhyay, A. K., Dutta, S. & Basu, S. Convergence of Biofilm Formation and Antibiotic Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Front. Med. 9, 793615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.793615 (2022).

Sen, T., Samanta, S.K. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 147, 59–110 (2015) https://doi.org/10.1007/10_2014_273 in: Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology 147, (Series Editor: T. Scheper Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014).

Bouarab-Chibane, L. et al. Antibacterial properties of polyphenols: characterization and QSAR (Quantitative structure–activity relationship) models. Front. Microbiol. 10, 829–852 (2019).

Müller, L., Fröhlich, K. & Böhm, V. Comparative antioxidant activities of carotenoids measured by ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), ABTS bleaching assay (αTEAC), DPPH assay and peroxyl radical scavenging assay. Food Chem. 129, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.045 (2011).

Gulcin, I. Antioxidants and Antioxidant Methods: An Updated Overview. Arch. Toxicol. 94, 651–715. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11082248 (2020).

Jakimiuk, K., Wink, M. & Tomczyk, M. Flavonoids of the Caryophyllaceae. Phytochem. Rev. 21, 179–218 (2022).

Nobela, O. et al. Tapping into the realm of underutilised green leafy vegetables: Using LCIT-Tof-MS based methods to explore phytochemical richness of Sonchus oleraceus (L.) L. South African J. Bot. 145, 207–212 (2022).

Sergio, L. et al. Bioactive phenolics and antioxidant capacity of some wild edible greens as affected by different cooking treatments. Foods 9, 1320–1339 (2020).

Sile, I. et al. Wild-grown and cultivated glechoma hederacea L.: Chemical composition and potential for cultivation in organic farming conditions. Plants 11, 819–842 (2022).

Mao, R. et al. The Marine Antimicrobial Peptide AOD with Intact Disulfide Bonds Has Remarkable Antibacterial and Anti-Biofilm Activity. Mar. Drugs. 22, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/md22100463 (2024).

Boulos, L., Prévost, M., Barbeau, B., Coallier, J. & Desjardins, R. LIVE/DEAD BacLight : application of a new rapid staining method for direct enumeration of viable and total bacteria in drinking water. J. Microbiol. Methods. 37, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00048-2 (1999).

Yu, J., Hong, C., Yin, L., Ping, Q. & Hu, G. Antimicrobial activity of phenyllactic acid against Klebsiella pneumoniae and its effect on cell wall membrane and genomic DNA. Braz. J. Microbiol. 54, 3245–3255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-023-01126-8 (2023).

Decker, T., Rautenbach, M., Khan, S. & Khan, W. Antibacterial efficacy and membrane mechanism of action of the Serratia-derived non-ionic lipopeptide, serrawettin W2-FL10. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e0295223. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.02952-23 (2024).

Montefusco-Pereira, C. V. et al. Coupling quaternary ammonium surfactants to the surface of liposomes improves both antibacterial efficacy and host cell biocompatibility. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 149, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2020.01.013 (2020).

Extremina, C. I., Fonseca, A. F., Granja, P. L. & Fonseca, A. P. Anti-adhesion and antiproliferative cellulose triacetate membrane for prevention of biomaterial-centred infections associated with Staphylococcus epidermidis. Int J. Antimicrob. Agents. 35, 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.017 (2010).

Berida, T. I. et al. Plant antibacterials: The challenges and opportunities. Heliyon 10, e31145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31145 (2024).

Visioli, F. Science and claims of the arena of food bioactives: comparison of drugs, nutrients, supplements, and Nutraceuticals. Food Funct 13, 12470–12474. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2fo02593k (2022).

Koss-Mikołajczyk, I., Kusznierewicz, B. & Bartoszek, A. The relationship between phytochemical composition and biological activities of differently pigmented varieties of berry fruits; Comparison between embedded in food matrix and isolated anthocyanins. Foods 8, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8120646 (2019).

Cappelli, G. & Mariani, F. A Systematic review on the antimicrobial properties of mediterranean wild edible plants: We still know too little about them, but what we do know makes persistent investigation worthwhile. Foods 10, 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092217 (2021).

Williams, I. et al. Flow cytometry and other techniques show that Staphylococcus aureus undergoes significant physiological changes in the early stages of surface-attached culture. Microbiol. (Reading) 145(Pt 6), 1325–1333. https://doi.org/10.1099/13500872-145-6-1325 (1999).

Coss, E., Kealey, C., Brady, D. & Walsh, P. A laboratory investigation of the antimicrobial activity of a selection of western phytomedicinal tinctures. Europ. J. Integrative Med. 19, 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2018.02.008 (2018).

Šeremet, D. et al. Studying the functional potential of ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea L.) extract using an in vitro methodology. Int. J. Mol. Sci 24, 16975–16994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316975 (2023).

Xia, D. Z., Yu, X. F., Zhu, Z. Y. & Zou, Z. D. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of six edible wild plants (Sonchus spp.) in China. Nat. Prod. Res. 25, 1893–1901 (2011).

Al-Hussaini, R. & Mahasneh, A. M. Microbial growth and quorum sensing antagonist activities of herbal plants extracts. Molecules 14, 3425–3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14093425 (2009).

Three invasive plants. Arsene, M.M.J., et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity, antibioresistance reversal properties, and toxicity screen of ethanolic extracts of Heracleum mantegazzianum Sommier and Levier (giant hogweed), Centaurea jacea L. (brown knapweed), and Chenopodium album L. (Pigweed). Open Vet J. 12, 584–594. https://doi.org/10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i4.22 (2022).

Lou, Z., Wang, H., Zhu, S., Ma, C. & Wang, Z. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of chlorogenic acid. J. Food Sci. 76, M398-403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02213.x (2011).

Adamczak, A., Ożarowski, M. & Karpiński, T. M. Antibacterial Activity of Some Flavonoids and Organic Acids Widely Distributed in Plants. J. Clin. Med. 9, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010109 (2020).

Peng, Y. et al. Absorption, metabolism, and bioactivity of vitexin: recent advances in understanding the efficacy of an important nutraceutical. Crit. Rev. In Food Sci. Nutrit. 61, 1049–1064 (2021).

Qian, W. et al. Mechanisms of action of luteolin against single- and dual-species of Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae and its antibiofilm activities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 193, 1397–1414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-020-03330-w (2021).

Zu, Y. G. et al. Chemical composition of the SFE-CO extracts from Cajanus cajan (L.) Huth and their antimicrobial activity in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 17, 1095–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2010.04.005 (2010).

Kwiecińska-Piróg, J. et al. Vitamin C in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentration of aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones alters Proteus mirabilis biofilm inhibitory rate. Antibiotics 8, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics8030116 (2019).

Gaglani, P. et al. A pro-oxidant property of vitamin C to overcome the burden of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: A cross-talk review with Fenton reaction. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1152269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1152269 (2023).

Esposito, T. et al. Activity of Colocasia esculenta (Taro) Corms against Gastric Adenocarcinoma Cells: Chemical Study and Molecular Characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010252 (2023).

Baranowska, M. et al. Interactions between bioactive components determine antioxidant, cytotoxic and nutrigenomic activity of cocoa powder extract. Free Radical Biol. Med. 154, 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.04.022 (2020).

Belley, A. et al. Oritavancin kills stationary-phase and biofilm Staphylococcus aureus cells in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 53, 918–925. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00766-08 (2009).

Brown, M. R., Allison, D. G. & Gilbert, P. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics: a growth-rate related effect?. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 22, 777–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/22.6.777 (1988).

European Medicines Agency 2006a. Guideline on Quality of Herbal Medicinal Products/Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products (CPMP/QWP/2819/00 Rev 1). http://www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003370.pdf, accessed in Dec (2023).

Singleton, V. L. & Rossi, J. A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Viticult 16, 144–158 (1965).

Cimini, S., Locato, V., Giacinti, V., Molinari, M. & De Gara, L. A multifactorial regulation of glutathione metabolism behind salt tolerance in rice. Antioxidants 11, 1114 (2022).

Tonto, T. C. et al. Methodological pipeline for monitoring post-harvest quality of leafy vegetables. Sci. Rep. 13, 20568–20583. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47873-4 (2023).

Prevete, G. et al. Resveratrol and resveratrol-loaded galactosylated liposomes: Anti-adherence and cell wall damage effects on staphylococcus aureus and MRSA. Biomolecules 13, 1794–1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13121794 (2023).

Balouiri, M., Sadiki, M. & Ibnsouda, S. K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 6, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005 (2016).

CLSI, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disc Susceptibility Tests, Approved Standard, 7th ed., CLSI document M02-A11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087, USA, (2012).

Acknowledgements

We are in debt with Dr. M.C. Zuin, responsible of the Phytoalimurgic Garden in Veneto Region, Padua University (https://www.research.unipd.it/handle/11577/2432488), for having provided us with plant material and seeds of the six WEPs species analyzed in the present study. We are also grateful with Dr. Giuliana Papoff for her generous assistance with the confocal microscope.

Funding

CNR Biomemory (https://biomemory.cnr.it/); CNR FOE-2021 DBA.AD005.225; NRRP, Next Generation EU project: i) Project code PE00000003, “ON Foods—Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security – Working ON Foods”; ii) Project code PE00000007: “One Health Basic andTranslation Research Actions addressing unmet Needs on Emerging Infectious Diseases, INF-ACT”. This research was also partially funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU – under the National Biodiversity Future Center. This project belongs to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU; Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP C83 C22000530001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: FM, LDG; Data curation. ED, IN, SC, LR; Formal analysis: ED, IN, SC, FM, LR, VR; Funding acquisition: FM, LDG; Investigation: VR, ED, LR, SC, FM; Methodology: IN, ED, SC, VR, FM; Roles/Writing—original draft: FM, ED, SC, LDG; and Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donati, E., Ramundi, V., Nicoletti, I. et al. Bioprospecting of six polyphenol-rich Mediterranean wild edible plants reveals antioxidant, antibiofilm and bactericidal properties against Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep 15, 28765 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03166-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03166-6