Abstract

Group recommendation aims to recommend relevant items that cater to the preferences of a group of users. Its quality is greatly influenced by the conformity psychology exhibited by both individual users and the group as a whole. However, current techniques often overlook the subtleties and dynamics of conformity. To enhance the accuracy and interpretability of group recommendation, we propose a novel self-supervised Conformity-aware Group Recommendation model named ConfGR, which leverages multi-motif HyperGraph Convolution Networks (HGCN) to seamlessly integrate two crucial perspectives of conformity: social selection and social influence. Specifically, we first design social-motif HGCN and retail-motif HGCN respectively to dynamically capture the changes in members’ conformity within different groups. Then we develop groupon-motif HGCN and a cross-group line graph to collaboratively learn groups’ conformity. Finally, we integrate self-supervised learning into the training of our model to jointly enhance group embeddings under different motifs by finding the best trade-off between members’ conformity and groups’ conformity. We evaluate our model on three real-world datasets and the experimental results show the superiority of our model compared to state-of-the-art group recommendation models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Group recommendation aims to provide suggestions that satisfy the preferences of the majority of the individuals within the group, which is important for many applications such as e-business, crowdfunding1, and social events2. For example, recommending a group an appropriate product can improve the success rate of group buying and bring higher revenue to e-business platforms. Suggesting suitable projects to crowdfunding investors can help them reach their funding goals. These wide applications have demanded group recommendation.

Group members’ activities are commonly affected by their conformity psychology, which can enhance the quality of group recommendation. Conformity is defined as a state of social psychology making people’s behaviors influenced by others in the group. In reality, the representation of a group should involve synergies of common interests as well as compromises on some personal tastes, i.e. two perspectives that constitute conformity: social selection and social influence. Social selection means the choices people make according to their own personal preferences, and social influence refers to the changes people make under the influence of others in the social network3,4. A recent case study focusing on Singles’ Day Shopping Festival highlights an intriguing phenomenon5. As individuals become part of a group during the event, their thoughts and emotions tend to converge towards a common direction, which is what we often call ‘following the herd’. This convergence is evident in the individuals’ conformist behavior within the group. As an example, the Tmall Singles’ Day witnessed a remarkable peak of 544,000 transactions per second in 2019, demonstrating the profound influence of conformity on collective consumer behavior. Therefore, conformity psychology does have a significant impact on group users’ online consumption behavior. Thus it can be exploited for enhancing group recommendations. Different group members may have different levels of conformity. Users’ conformity may change due to their group changes too. Hence, it is crucial to devise dynamic conformity-aware group recommendation models.

Motivating example

We study the problem of conformity-aware group recommendation. Given a group of users and the historical interaction data, we aim to automatically learn the conformity psychology for both the group and its members, and return a list of items that satisfy their conformity psychology. For conformity-aware group recommendation, three key issues need to be addressed. First, we need to design a member representation learning that dynamically reflects members’ conformity psychology. It is inevitable that a member’s conformity may fluctuate due to the diverse influences exerted by other group members. For example, Helen (a pizza enthusiast) and her friends form a pizza-loving group, with Helen’s preferences taking the lead. However, when dining with her parents, the group opts for lighter fare favored by seniors, as their influence now dominates the choice. A good model should be able to capture the dynamic changes of each member’s conformity and provide explanations on which perspective of conformity is responsible for the generation of recommendations. Second, we need to design a group representation learning that well captures groups’ conformity. Sometimes a group’s general preference may be different from its members’ preferences, especially when there are large differences in preferences among members. The group’s preference independent of member interests cannot be predicted by aggregating members’ preferences. For instance, consider a scenario within a family where the child has a preference for children’s songs, whereas the parents lean towards country music. Nevertheless, when they collectively listen to music, due to the influence of other families with similar tastes, they might ultimately choose a light music track that differs from each individual’s preferred genre. Thus modeling the group’s conformity from the group level is a valuable research issue. Finally, we need to design an adaptive strategy that captures the interactions between members’ and groups’ conformity. For instance, if a family collectively opts to listen to light music, this choice is likely to foster a mutual appreciation for this genre among all family members, and conversely. Overlooking these interactions could potentially compromise the quality of recommendation.

Our approach and contributions

Previous group recommendation methods can be categorized into memory-based methods6,7,8,9,10,11 and model-based methods12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. However, none of them considers the effects of the conformity psychology, nor supports the model’s interpretability from the perspective of conformity. Therefore, we propose a self-supervised Conformity-aware Group Recommendation model (ConfGR) using multi-motif HyperGraph Convolution Networks (HGCN) to seamlessly integrate two crucial perspectives of conformity: social selection and social influence. As shown in Fig. 1, we fully exploit the interaction data to model members’/groups’ conformity. Via these interaction data, we define three categories of motifs (retail-motif, social-motif and groupon-motif) to concretize different types of high-order relations. Retail-motifs represent high-order retail relations extracted from user-item interaction data. For example, motifs such as “co-purchasing” (users A and B both buy items X and Y) or “sequential browsing” (user A views item X, then Y, followed by user B doing the same) capture latent retail patterns. These are derived by analyzing transaction sequences, item co-occurrences, and temporal proximity in purchase logs. Social-motifs reflect high-order social relations inferred from user-user interaction data, including friendships, followings, or collaborative activities (e.g., co-rating items, commenting on each other’s posts). Quantification involves social network analysis metrics (e.g., clustering coefficients, centrality measures) and probabilistic modeling of interaction likelihoods. Groupon-motifs capture high-order group relations derived from group-item interaction data, such as collective purchasing (e.g., a group buying a bundle of items) or shared preferences within communities. These are identified by clustering group behaviors (e.g., average purchase frequency per group) and item-group affinity scores. For each category of motifs, a motif-induced hypergraph is constructed and encoded by HGCN. Specifically, with retail-motif HGCN and social-motif HGCN, a novel member representation learning is proposed to model member-level social selection and social influence. Then, with groupon-motif HGCN, a new group representation learning is proposed to model group-level social selection and social influence. Finally, a self-supervised learning is proposed to provide groups recommendation maximally meeting the conformity of both members and groups. We summarise our contributions as follows.

-

We design social-motif HGCN and retail-motif HGCN respectively to learn and aggregate members’ representations. With these HGCN, the changes in members’ conformity within different groups can be captured dynamically to better support the model’s interpretability.

-

We design groupon-motif HGCN and a cross-group line graph to learn groups’ representations. By collaboratively learning groups’ conformity, groups’ preferences independent of member interests can be predicted.

-

We incorporate self-supervised learning into the training of our model to jointly enhance group embeddings under different motifs by finding the best trade-off between members’ conformity and groups’ conformity.

-

We evaluate our model on three real-world datasets and the experimental results show the superiority of our model compared to state-of-the-art group recommendation models.

Related work

We review existing literature on three topics closely related to our work, including memory-based group recommendation, model-based group recommendation,and self-supervised learning for recommendation.

The memory-based methods focus on rating aggregation or preference aggregation. The former involves calculating the individual ratings of all members in a group regarding a particular item. Subsequently, these individual ratings are combined to determine the overall preference rating for the group. The general aggregation strategies include the average satisfaction6, the least misery7, the maximum satisfaction8, the subgroup interest contribution and the subgroup activeness9. Though intuitive, these pre-defined aggregation rules are not adaptable to different groups. Instead of simply aggregating the individual ratings, the preference aggregation-based methods10,11 aggregate member profiles as a group profile and then apply individual recommendation models to generate recommendations. For instance, in10, the characteristics of TV programs watched by an individual are leveraged to form a feature vector for each member’s profile. Subsequently, the profiles of all members within a group are aggregated to create a comprehensive group profile. In11, the user’s rating vector on various items serves as his/her individual profile. When aggregating these profiles within a group, a straightforward linear combination is employed. However, these member profiles rely on explicit features which are usually limited or unavailable. In addition, these methods consider the users in a group separately, which overlooks their interactions. As a result, member/group profiles may not be effectively represented.

Model-based approaches, especially GNNs and GATs, are reshaping recommender systems by modeling complex relational dynamics

26,27,28,29. For group recommendation, the model-based approaches are also adopted to analyze user interactions to build user-item latent factors. In12, a neural group recommender is proposed, which uses sub-attentional networks to dynamically learn the impact weights of group members. In15, a group recommender system is designed that integrates an attention network with neural collaborative filtering30 to dynamically compute item-specific weights for group members. In16,17, an attention mechanism and a bipartite graph embedding model are designed to learn users’ local and global social influence. In18 the social followee relationship among members is employed as a means to represent their preferences. In13 social user associations and distinctions across groups are captured to learn and aggregate members’ preferences. To model the complex high-order relations among members, hypergraphs19,20,21,22,23,25,31,32,33 have been widely used to capture member/group preference. For instance, in19, a hierarchical hypergraph convolutional network is introduced to comprehensively capture both inter-group and intra-group interactions among members. Similarly,20 presents a GNN-based group recommender that leverages hyperedge embedding to learn group preferences. Furthermore,21 proposes a dual channel hypergraph convolutional network specifically designed for group recommendation. Additionally,25 introduces a group recommendation model that relies on dual-level hypergraph representation learning. However, despite their advancements, these approaches fundamentally fail to systematically model the dynamics of conformity psychology, a critical social mechanism that underpins group decision-making. First, these methods treat user-user or group-item interactions as static context-free signals, ignoring the context-dependent, non-linear evolution of conformity pressure. Second, conformity is typically reduced to implicit latent factors (e.g., attention weights or graph embeddings), which conflate it with generic social influence or collaborative filtering signals, rather than formalizing it as a distinct, dynamic process driven by group composition changes. Third, the lack of conformity-aware interpretability frameworks means that existing models cannot explain why a group’s recommendation deviates from individual preferences, rendering their outputs black-box decisions in socially sensitive scenarios (e.g., group travel planning, team project selection).

To address the issue of data sparsity in recommender systems, several studies (e.g.13,19,34,35,36,37,38,39,40) have explored the use of self-supervised learning. In34, \(S^3\)-Rec adopts self-supervised training strategies to pre-train the model, leveraging the inherent structure and patterns within the data. Similarly,36 employs a self-supervised Q-learning technique to fine-tune a next-item recommendation model. GroupIM13 is the first model to leverage self-supervised learning for group recommendation tasks. It aims to maximize the mutual information between users and groups, optimizing their representations. Moreover, in19,24 some graph augmentation strategies are considered as the self-supervision signals in group recommendation. Existing self-supervised learning approaches in recommender systems (e.g., mutual information maximization, graph augmentation) rely on statistical correlations (e.g., user-item co-occurrences, graph structural similarities) to generate signals, treating social influence as an implicit latent dependency. This passive reliance on data patterns limits their ability to explain why users change preferences (e.g., a user suddenly aligning with group ratings without clear rationale). In contrast, our conformity-based self-supervision explicitly models conformity pressure as a social mechanism by quantifying the deviation between individual preferences and group consensus. This enables it to proactively capture dynamic preference shifts driven by social conformity (e.g., a user’s rating adjusting to align with peers after observing group trends), bridging the gap between statistical learning and interpretable social dynamics in group recommendations.

Our proposed model: ConfGR

In this section, we first present the overarching architecture of our proposed model. We then elaborate on its three core components (Member-level Representation Learning, Group-level Representation Learning and Enhancing Recommendation with Self-Supervision). Finally, we conduct a computational complexity analysis to quantify the model’s scalability and efficiency.

As shown in Fig. 2, we propose a conformity-aware group recommendation framework. Given a group g and the historical user-item, user-user, group-item and group-user interactions (denoted as \({\mathscr {R}}^I\), \({\mathscr {R}}^U\), \({\mathscr {R}}^G\), \({\mathscr {R}}^A\), respectively), our framework predicts the rating \({\hat{y}}_{gv}\) of g to each item v (v is new to g) and outputs the top-k recommendations with top ratings. It contains three major components, member-level representation learning, group-level representation learning, and enhancing recommendation with self-supervision. The member-level representation learning component learns member-level social selection (SS) and social influence (SI) based on user-item, user-user and group-item interactions. Through members’ conformity aggregation, the member-level representations are fused into the groups’ representations. The group-level representation learning component takes group-item and group-user interactions as the input and learns the groups’ representations from the perspective of group-level SS and SI respectively. The component of enhancing recommendation with self-supervision integrates self-supervised learning into the model training, which jointly enhances group embeddings under different motifs. The notations used in this paper are listed in Table 1.

Member-level representation learning

Heterogeneous network

Given a user set U (\(\vert \textit{U}\vert\)=m), an item set V (\(\vert \textit{V}\vert\)=n), a group set G (\(\vert \textit{G}\vert\) = k), user-item interactions \({\mathscr {R}}^I\), user-user interactions \({\mathscr {R}}^U\) and group-user interactions \({\mathscr {R}}^A\), we can construct a heterogeneous network \({\mathscr {G}}\). It is a weighted graph \({\mathscr {G}}\)=(\({\mathscr {V}}\), \({\mathscr {E}}\), \({\mathscr {R}}^I\), \({\mathscr {R}}^U\), \({\mathscr {R}}^A\)), where \({\mathscr {V}}\) is the vertex set to denote the union set of users U and items V, \({\mathscr {E}} \sqsubseteq (U\times V)\cup (U\times U)\) is the edge set to denote user-item interactions and user-user interactions. \({\mathscr {R}}^I\) and \({\mathscr {R}}^U\) are the functions defined on \({\mathscr {E}}\). \({\mathscr {R}}^I(i, j)\) (\(i \in U\), \(j \in V\)) is used to describe the interaction between a user i and an item j, whose value reflects how much i likes j. \({\mathscr {R}}^U(i, j)\) (\(i \in U\), \(j \in U\)) is used to denote the social relationship (e.g., friendship or followee) between two users i and j. And \({\mathscr {R}}^A(i, j)\) (\(i \in U\), \(j \in G\)) indicates whether a user i belongs to a group j. For example, the left part of Figure 3 shows a heterogeneous network containing 6 users (forming 3 groups {\(u_1\), \(u_2\)}, {\(u_2\), \(u_3\)} and {\(u_2\), \(u_3\), \(u_5\)}) and 7 items. The yellow edges represent the user-item interactions such as ‘purchasing’, while the blue edges mean the user-user interactions to denote the social relationship.

Retail-motif/Social-motif hypergraph

Users/items demonstrate correlations both within and across groups. It is crucial to define the interactions among them appropriately. The above heterogeneous network \({\mathscr {G}}\), which only supports pairwise relationships (i.e. user-item, user-user, or user-group), is not suitable for this case. Thus, based on \({\mathscr {G}}\), we construct a retail-motif hypergraph \({\mathscr {G}}^I = ({\mathscr {V}}^I, {\varepsilon }^I)\) and a social-motif hypergraph \({\mathscr {G}}^U = ({\mathscr {V}}^U, {\varepsilon }^U)\), to capture the high-order user-item and user-user interactions respectively. \({\mathscr {V}}^I\) (or \({\mathscr {V}}^U\)) is the vertex set \(U \cup V\) (or U), and \(\varepsilon ^I\) (or \(\varepsilon ^U\)) is the hyperedge set containing k (or \(k'\), \(k' \le k\)) hyperedges. Each hyperedge contains the vertices from \({\mathscr {V}}^I\) (or \({\mathscr {V}}^U\)) related to the same group, i.e. the group members and the interacted items (or users) by them. Two incidence matrices \({H^I} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{(m+n)\times k}\) and \({H^U} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{m\times k'}\) are used to describe \({\mathscr {G}}^I\) and \({\mathscr {G}}^U\) respectively, where \(h_{\textit{v}\epsilon } = 1\) if the hyperedge \(\epsilon\) contains the vertex v, otherwise \(h_{\textit{v}\epsilon } = 0\). The diagonal matrices \({D}^I\) and \({D}^U\) are used to denote the degrees of vertices in \({\mathscr {V}}^I\) and \({\mathscr {V}}^U\) respectively, with the entries \({d^I}_{\textit{v}} = \sum _{\epsilon \in \varepsilon ^I}{{w}_\epsilon {h}_{\textit{v}\epsilon }}\) and \({d^U}_{\textit{v}} = \sum _{\epsilon \in \varepsilon ^U}{{w}_\epsilon {h}_{\textit{v}\epsilon }}\). Here the weight \({w}_\epsilon\) is described by the diagonal matrix \({W^I} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{k \times k}\) or \({W^U} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{k' \times k'}\). Besides, two diagonal matrices \({B^I}\) and \({B^U}\) are used to denote the degrees of hyperedges in \(\varepsilon ^I\) and \(\varepsilon ^U\) respectively, with the entries \({b^I}_\epsilon\) = \(\sum _{v \in {\mathscr {V}}^I}{{h}_{v\epsilon }}\) and \({b^U}_\epsilon\) = \(\sum _{v \in {\mathscr {V}}^U}{{h}_{v\epsilon }}\). For example, the right part of Fig. 3 shows such two hypergraphs. For the group {\(u_1\), \(u_2\)}, its members and their interacted items (i.e. \(v_2\), \(v_3\) and \(v_6\)) are explicitly connected within the same hyperedge \(\varepsilon _1^I\) in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\). Similarly, {\(u_1\), \(u_2\)} and their interacted user \(u_6\) belong to the same hyperedge \(\varepsilon _2^U\) in \({\mathscr {G}}^U\).

Social selection-based member modeling

Social selection-based member modeling aims to learn member latent factors from the perspective of social selection (i.e. member-level social selection), denoted as \(x_i\) for member \(u_i\). Member-level social selection reflects whether a member interacts with an item by his/her own background knowledge or personal preferences, which is often indicated by the member’s interacted items. For example, a pizza lover likes visiting pizza restaurants and a skiing enthusiast prefers browsing information about ski tools. Thus, it is helpful to derive member-level social selection from the user-item interactions. From the constructed \({\mathscr {G}}^I\), we can capture the high-order retail relations, i.e. retail-motifs. Thus, with the above constructed \({\mathscr {G}}^I\) as input, we design retail-motif HGCN to encode member-level social selection. We adopt two-stage aggregation to learn member-level social selection from \({\mathscr {G}}^I\). The first stage is intra-hyperedge aggregation, which learns intra-hyperedge member latent factor \(x_i^I\) within one hyperedge in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\). The second stage is cross-hyperedge aggregation where cross-hyperedge user latent factor \(x_i^C\) is learned in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\).

Intra-hyperedge Aggregation. Intra-hyperedge aggregation learns the intra-hyperedge member latent factor \(x_i^I\) by considering the other members in \(u_i\)’s group and the items they interact with. Referring to the spectral hypergraph convolution32, we use Eq. (1) to mathematically represent this aggregation:

where \(\epsilon\) means the hyperedge representing the target group, \((x_i^I)^{l}\) denotes \(u_i\)’s embedding in the l-th HGCN, \(x_j^I\) denotes the embedding of the j-th vertex (i.e. member or item) contained in \(\epsilon\), and \(\Theta\) is the parameter matrix between two convolutional layers. The incidence matrix \({H^I}\) is used to describe whether a hyperedge in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\) contains a vertex v. Thus, we can also define the above function by using the value of \(h_{j\epsilon }\). Here the left side of Eqn. 1 explicitly aggregates features from vertices directly connected to the group hyperedge \(\epsilon\), modeling localized group interactions. And the right side achieves the same aggregation, aligning with hypergraph theory where edges can connect arbitrary numbers of vertices.

Cross-hyperedge Aggregation. The same member may belong to several different groups. His/her social selection may be different in different groups. Cross-hyperedge aggregation learns the cross-hyperedge member latent factor \(x_i^C\) by aggregating all the above intra-hyperedge latent factor \(x_i^I\)s. We model the cross-hyperedge member embedding \(x_i^C\) as the weighted sum over the member’s intra-hyperedge embeddings in different hyperedges (as in Eq. 2):

where \(\epsilon\) means the hyperedge representing one of \(u_i\)’s groups, and \(w_\epsilon\) denotes \(\epsilon\)’s weight. Similarly, we use the value of \(h_{i\epsilon }\) from the incidence matrix \({H^I}\) to indicate whether a hyperedge \(\epsilon\) in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\) contains \(u_i\). All the intra-hyperedge embeddings within the hyperedges containing \(u_i\) will be aggregated together. Here \((x_i^C)^{(l+1)}\) is the member-level social selection \((x_i)^{(l+1)}\). Eqn. 2 is used to learn the member’s global latent factor \((x_i^C)^{(l+1)}\) by aggregating their intra-hyperedge embeddings \((x_j^C)^l\) across all groups they belong to. Referring to the row normalization21, we rewrite Eq. (2) as the matrix form:

where \({D^I}\) denotes the vertex degree matrix for \({\mathscr {G}}^I\), \({H^I}\) means the hyperedge degree matrix for \({\mathscr {G}}^I\), \({W^I}\) is the weight matrix of hyperedges, and \({B^I}\) is regarded as the hyperedge degree matrix. \({D^I}\) and \({B^I}\) play a role of the normalization. Initially, each hyperedge in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\) is assigned the same weight. Via the above two-stage aggregation, the member-level social selection can be learned. Eq. (3) generalizes standard graph convolution (as shown on the right side) to hypergraphs, enabling multi-way group interactions without assuming pairwise vertex relations.

Social influence-based member modeling

In addition to social selection, members’ behaviors may be affected by social influence from other members as well. We need to learn member latent factors from the perspective of social influence (i.e. member-level social influence), denoted as \(z_i\) for member \(u_i\). Member-level social influence is reflected in the changes members make under the influence of others in the social network. Thus, we use the constructed \({\mathscr {G}}^U\) to capture the high-order social relations, i.e. soical motifs. With the above constructed \({\mathscr {G}}^U\) as input, we design social-motif HGCN to encode member-level social influence. Similar to social selection-based member modeling, we also adopt two-stage aggregation (i.e. intra-hyperedge aggregation and cross-hyperedge aggregation) to learn member-level social influence. Intra-hyperedge aggregation aims to learn intra-hyperedge member latent factor \(z_i^I\) within one hyperedge in \({\mathscr {G}}^U\), while cross-hyperedge aggregation aims to learn cross-hyperedge user latent factor \(z_i^C\) (i.e. the final \(z_i\)) in \({\mathscr {G}}^U\). First, for each hyperedge containing \(u_i\) in \({\mathscr {G}}^U\), we aggregate \(u_i\)’s neighbors belonging to the same hyperedge as \(u_i\) to encode intra-hyperedge member latent factor \(z_i^I\). It is natural that a member’s social influence may vary due to the changes of his/her social groups. We need to learn the cross-hyperedge member latent factor \(z_i^C\) by aggregating all the intra-hyperedge member latent factors. The member-level social influence can be represented as the matrix form (as in Eq. 4):

where \({D^U}\) denotes the vertex degree matrix for \({\mathscr {G}}^U\), \({H^U}\) means the hyperedge degree matrix for \({\mathscr {G}}^U\), \({W^U}\) is the weight matrix of hyperedges, and \({B^U}\) is regarded as the hyperedge degree matrix. Similar to Eqn. 3, Eqn. 4 generalizes standard graph convolution (as shown on the right side) to hypergraphs too.

Members’ conformity aggregation

Members’ conformity aggregation aims to capture members’ conformity to represent member preferences, and then aggregate them together to represent group preferences. Empirically, member preferences are related to his/her individual interest, as well as the influence from other members. In order to capture members’ conformity, member-level social selection and member-level social influence need to be integrated together. Thus, we propose two attention mechanisms to assign weights to them (shown in Fig. 4).

Intuitively, the greater a member’s interest is on an item, the greater the impact of his/her social selection is. We use an attention mechanism to learn the weight of member-level social selection. The weight indicates the extent to which members adhere to their individual interests (as in Eq. 5):

where \(\Pi _{uv}^*\) denotes the attention weight of u’s interaction with the target item v, \(\sigma\) is the activation function, and h, W, b are learnable parameters. We use \(\Pi _{uv}^*\) to weight the user-item interaction in contributing to member u’s latent factor when characterizing u’s social selection from his/her interaction history in \({\mathscr {G}}^I\). Therefore, \(\Pi _{uv}^*\) can be interpreted as the contribution of member-level social selection to member u’s latent factor.

Besides, we use the other attention mechanism to learn the weight of member-level social influence, which is used to measure the extent to which group members are influenced by their peers when making decisions. First, we use \(Z_{{\overline{u}}}\) to represent the set of latent factors of u’s peers. Then, the weight of member-level social influence is calculated as Eq. (6):

where \(h_{i}, W_{1}, W_{2}, b_{i}\) are learnable parameters, \(\sigma\) is the activation function, and CONCAT(\(\cdot\)) is the function to connect all the member latent factors in \(Z_{{\overline{u}}}\). \(\Pi _{u{\overline{u}}}^*\) can be interpreted as the contribution of member-level social influence to member u’s latent factor.

In order to capture members’ conformity, we propose to combine the above two member latent factors to the final member latent factor (denoted as \({\mathscr {M}}_u\)), where \(x_u\) and \(z_u\) are combined together. Due to the two attention mechanisms, the dynamic changes in each member’s conformity can be captured better. Finally, the group is represented as a vector \(g^{U}\) by aggregating all the embeddings of its members, i.e. \(g^{U}=\sum _{u \in g}{{\mathscr {M}}_u}=\sum _{u \in g}{{\Pi _{uv}x_u}+\Pi _{u{\overline{u}}}z_u}\).

Group-level representation learning

In this section, we first construct a groupon-motif hypergraph to describe the high-order groupon relations from group-item interactions. Then, by collaboratively learning the two group-level social effects, we get the final group representation.

Groupon-motif hypergraph

To capture the high-order groupon relations, we construct a groupon-motif hypergraph \({\mathscr {G}}^G = ({\mathscr {V}}^G, {\varepsilon }^G)\) based on group-item interactions. Here \({\mathscr {V}}^G\) is the union of the group set G and the item set V, and \(\varepsilon ^G\) is the hyperedge set. Each hyperedge in \(\varepsilon ^G\) contains the vertices in \({\mathscr {V}}^G\) that are associated with a certain group, including that group and its interacted items, as well as other groups that have interacted items in common with that group. Similar to the retail-motif hypergraph and the social-motif hypergraph, we also need to construct one incidence matrix \({H^G}\) and three diagonal matrices (\({D}^G\), \({W^G}\) and \({B^G}\)).

Social selection-based group modeling

Group preferences are not only related to members’ preferences but also to the group’s intrinsic interests. The goal of social selection-based group modeling is to learn group latent factors from the perspective of social selection (i.e. group-level social selection), denoted as \(p_i\) for group \(g_i\). Group-level social selection determines whether a group interacts with an item by its intrinsic preferences. The groupon-motif hypergraph \({\mathscr {G}}^G\) describes the high-order groupon relations. Therefore, with \({\mathscr {G}}^G\) as input, we design groupon-motif HGCN and adopt two-stage aggregation (i.e. intra-hyperedge aggregation and cross-hyperedge aggregation) to learn group-level social selection. Similar to Eqn. 2, we model the group embedding \(p_i\) as the weighted sum over the group’s intra-hyperedge embeddings in different hyperedges, i.e. \(P^{(l+1)} = ({D^G})^{-1} {H^G} {W^G} ({B^G})^{-1} ({H^G})^{T} P^{l}{\Theta }^{l}\).

Social influence-based group modeling

It aims to learn group latent factors from the perspective of social influence (i.e. group-level social influence), denoted as \(q_i\) for group \(g_i\). Since a user can be a part of several groups concurrently, groups with a greater number of shared members tend to exhibit similar preferences at the group level, leading to a stronger social influence among them. In order to describe the group-level social influence, we define a cross-group line graph based on the group-user interactions. Given the group-user interactions, the cross-group line graph \({\mathscr {G}}^L = ({\mathscr {V}}^L, {\varepsilon }^L, W^L)\) includes a number of nodes and edges. In the line graph \({\mathscr {G}}^L\), each node represents a distinct group, and an edge exists between two nodes if the corresponding groups have at least one common member. It models groups as individual nodes and connects them based on shared membership. In contrast to the social-motif hypergraph, which illustrates the social influence at the member level, the cross-group line graph captures the cross-group relationships, also known as group-level social influence. This allows us to understand not only how individuals influence each other but also how groups interact and influence each other through their shared members. Intuitively, the social influence between two groups is related to the following two factors: (1) the larger the number of common members, the stronger the social influence; (2) the smaller the total number of members in groups, the stronger the social influence. Therefore, we assign each edge (\(v_i^L\), \(v_j^L\)) a weight \(W_{i,j}^L\), where \(W_{i,j}^L\) = \(\vert {g_i}\cap {g_j}\vert /\vert {g_i}\cup {g_j}\vert\). Given a group \(g_i\), for its every neighboring group \(g_j\), we adopt a MEAN aggregator to aggregate their common members’ latent factors (i.e. \({\mathscr {M}}_u\)) to represent \(g_j\). In order to represent group latent factors from the perspective of social influence, we aggregate the representations of \(g_i\)’s neighboring groups from the cross-group line graph, i.e. \(q_i = \sum _{j \in {\mathscr {N}}(i)}{W_{ij}^LAggre\{{\mathscr {M}}_u,\forall u \in g_i\cap g_j\}}\). Here Aggre serves as the aggregation function to aggregate the member-level representations of individuals who belong to both groups \(g_i\) and \(g_j\). The weight \(W_{ij}\) is assigned based on the similarity between these two groups, reflecting the strength of their relationship.

To derive the final representation of group, we consolidate the latent factors from two perspectives of social effects: \(g^{G}=\omega p + (1-\omega )q\). Here, \(\omega\) is a hyper-parameter, regulating the influence of each perspective in the aggregation process.

Enhancing recommendation with self-supervision

In this section, we integrate self-supervised learning into model training, which enhances the above two levels simultaneously by finding the best trade-off between users’ and groups’ conformity.

The self-supervised task

We leverage contrastive learning to enhance the discriminative and generalizable power of group embeddings. To achieve this, we treat two levels of the same group instance as a positive pair, while considering levels of different group instances as negative samples. By contrasting and optimizing these group embeddings, we aim to maximize the consistency between positive pairs while minimizing the agreement between negative pairs. To operationalize this learning objective, we design a discriminator function that takes two group embeddings as input and evaluates their consistency. The discriminator is trained to assign higher consistency scores to positive pairs compared to negative samples. This process effectively maximizes the mutual information between the group embeddings representing the same group instance. Specifically, we adopt a cross-entropy loss function to measure the agreement between positive and negative samples (as in Eq. 7):

where \(g_i^U\) and \(g_i^G\) constitute a positive pair, \(\widetilde{g_j}\) is a negative sample and \(f_{{\mathscr {D}}}\) is the discriminator function that evaluates the consistency between two embeddings. We implement the discriminator as \(f_{{\mathscr {D}}}\left( g_i^U, g_i^G\right) =\sigma \left( g_i^U {W}_{{\mathscr {D}}}(g_i^G)^ T\right)\), where \({W}_{{\mathscr {D}}}\) is the discriminator network, and \(\sigma\) is the logistic sigmoid non-linearity function to convert raw values into the probability that \(g_i^U\) and \(g_i^G\) are consistent.

Two recommendation tasks

Besides the self-supervised task, our model includes two recommendation tasks. For the user recommendation task, we use Multi-Layer Perception (MLP) to predict the rating of an item v for a user u according to u’s preferences. By member-level representation learning, the member-level embeddings of u and v have been learned (i.e. \({\mathscr {M}}_u\) and \({\mathscr {M}}_v\)), which are used for rating prediction of the user recommendation task. We first concatenate \({\mathscr {M}}_u\) and \({\mathscr {M}}_v\) together, then feed the fused embedding into MLP layers to get the predicted rating \({\hat{y}}_{uv}\). Similarly, for the group recommendation task, we also use MLP to predict the rating \({\hat{y}}_{gv}\) according to g’s group preferences.

Because our approach relies on implicit interactions to recommend the top-K items for groups, we utilize pairwise learning to fine-tune our model’s parameters. However, group-item interactions are often sparse, making it challenging to effectively train our model. To address this issue, we incorporate user-item interactions into the training process, enabling us to optimize both group and individual recommendation tasks simultaneously. This approach leverages the richer information available from user-item interactions to enhance the learning of group preferences, ultimately leading to improved recommendation quality. Here we define two distinct loss functions, one for group-item interactions (\({\mathscr {L}}_{G}\)) and another for user-item interactions (\({\mathscr {L}}_{U}\)). These loss functions are tailored to optimize our recommendation model’s performance on both types of interactions. For group-item interactions, we have \({\mathscr {L}}_{G} = \sum _{(g,v,v^{'} \in {\mathscr {O}})}({\hat{y}}_{gv}-{\hat{y}}_{gv^{'}}-1)^{2}\), where \({\mathscr {O}}\) represents the set of training instances for groups. Each instance \((g,v,v^{'})\) in this set indicates that group g has interacted with item v but not with item \(v^{'}\). The loss function \({\mathscr {L}}_{G}\) penalizes the model when it predicts a higher preference score for an item \(v^{'}\) that the group g has not interacted with, compared to an item v that the group has interacted with. Similarly, for user-item interactions, we have \({\mathscr {L}}_{U} = \sum _{(u,v,v^{'} \in \mathscr {O}^{'})}({\hat{y}}_{uv}-{\hat{y}}_{uv^{'}}-1)^{2}\), where \(\mathscr {O}^{'}\) represents the set of training instances for individual users.

Two-phase model training

To optimize the parameters of the ConfGR model, we combine the loss functions of the above three tasks: the self-supervised task (\({\mathscr {L}}_{GG}\)), the group recommendation task (\({\mathscr {L}}_{G}\)), and the user recommendation task (\({\mathscr {L}}_{U}\)). The combined loss function is expressed as \({\mathscr {L}} = \lambda {\mathscr {L}}_{GG} + {\mathscr {L}}_{G} + {\mathscr {L}}_{U}\), where \(\lambda\) serves as a hyper-parameter to strike a balance between the self-supervised task and the two recommendation tasks. We employ a two-phase training scheme that involves pre-training followed by fine-tuning. In the pre-training phase, we focus on the self-supervised task, updating the model parameters to initialize them effectively. Specifically, we leverage the self-supervised task to pre-train the group embeddings on two different levels. This pre-training step ensures that the parameters are well-suited for subsequent recommendation tasks. Subsequently, in the fine-tuning phase, we utilize the pre-trained model parameters as a starting point and fine-tune them for the recommendation tasks. To enhance the learning process, we adopt a joint training strategy that jointly updates the loss functions of the recommendation tasks. This allows the pre-trained group embeddings to be further optimized under the influence of the objective functions \({\mathscr {L}}_{G}\) and \({\mathscr {L}}_{U}\), ensuring that they are tailored to improve the performance of the model.

Complexity analysis

In this section, we discuss the complexity of our proposed model. The trainable parameters of our model can be categorized into two groups: user/item/group embeddings and gate parameters. Given a user set U (\(\vert \textit{U}\vert\)=m), an item set V (\(\vert \textit{V}\vert\)=n), a group set G (\(\vert \textit{G}\vert\) = k), we only focus on learning the 0-th layer embeddings. Then the number of parameters for user/item/group embeddings is \(m \times d /n\times d/k\times d\). Here, d is the embedding dimension. For gate parameters, we incorporate a total of five gates into our model. Four of these gates are specifically designed for member-level/group-level representation learning, while the remaining one is utilized for self-supervision. Each gate is equipped with parameters of size (d + 1) \(\times d\). By summing up the parameters from all the categories, the overall model size can be approximated as (m+n+k+5d)d. As min(m,n,k)\(>>d\), our model can be considered relatively lightweight in terms of parameter count. The computational cost mainly derives from hypergraph convolution. For the hypergraph convolution that spans L layers, the propagation cost is bounded by O(|\(H^+|\times d\times L\)), where |\(H^+\)| represents the number of non-zero elements in the hypergraph adjacency matrix H. In our specific case, |\(H^+\)| is determined as the maximum value among |\(H^U(H^U)^T\)| and |\(H^I(H^I)^T\)|, corresponding to user or item hypergraph structures.

Experiments

In this section, we perform experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness of ConfGR. We aim at answering the following research questions. RQ1: Does the proposed ConfGR outperform other state-of-the-art methods for group recommendation? RQ2: Does the proposed ConfGR benefit from our well-designed components, i.e. member-level representation learning (MRL), group-level representation learning (GRL), and enhancing recommendation with self-supervision (SSL)? RQ3: How do the key hyper-parameters impact the performance of ConfGR? RQ4: How about the interpretability of ConfGR in the real-world group recommendation scenario?

Experimental setup

In reality, groups are typically categorized into two types: persistent groups and occasional groups13,41,42. For occasional groups, the group-item interactions are too sparse to learn the groups’ preferences straightforwardly. To address this sparsity issue, we incorporate three additional types of interaction data beyond just group-item interactions. To validate it, we conduct experiments on three datasets: Mafengwo18, Weeplaces13, and Douban-Event16, which can better simulate different levels of sparsity. For Mafengwo, we select groups, each consisting of at least two members and visiting at least three venues. The followee information is crawled to capture the user-user interactions. For Weeplaces, we follow the method adopted by13 to construct group-item interactions and user-user interactions by leveraging users’ check-in records and social relationships. For Douban-Event, we follow the approach detailed in16 to obtain the event attendance lists and social friends for each user. Given that Douban-Event lacks explicit group information, we infer implicit group activities by identifying users who visit the same venue or participate in the same event, treating their collective activities as those of the group. Table 2 denotes the basic statistics of the three datasets. We select three datasets with distinct group size distributions and cross-domain coverage. For example, Weeplaces contains primarily small groups (average size = 2.9 members), while Mafengwo includes larger groups (average size = 7.19 members). Douban-Event spans entertainment events (e.g., concerts, exhibitions), whereas Mafengwo focuses on travel-related groups (e.g., family tours, backpacker communities). We further quantified interaction sparsity (average items per group): Douban-Event exhibits the highest sparsity (average items/group = 1.48), while Mafengwo and Weeplaces are denser (3.61 and 2.95 items/group, respectively). Subsequently, we randomly divide each dataset into training, validation, and test sets, with a ratio of 70%, 10% and 20%, respectively.

To justify the effectiveness of our model, we compare it with the following methods. (1) NCF30 treats a group as a virtual user, disregarding member-specific information. This serves as a baseline to assess whether traditional collaborative filtering techniques can be directly applied to group recommendation. (2) AGREE15 employs an attentive preference aggregator to compute group member weights and jointly trains over user-item and group-item interactions. (3) SoAGREE18 incorporates the social followee information via an attention network to enhance the representation of group/user. (4) SIGR16 utilizes a deep social influence learning framework to learn the social influence of each group member. (5) CAGR17 adopts a self-attentive mechanism to represent groups and leverages social networks to enhance user representation learning. (6) MoSAN12 adopts sub-attention to learn each member’s representation and computes final group representations by summing them. (7) GroupIM13 uses an attention mechanism to aggregate members’ preferences as group preferences. (8) \(S^{2}\)-HHGR19 integrates both hypergraph learning and self-supervised learning to learn group preferences. (9) ConsRec23 explores consensus behind group behavior data and adopts a hypergraph neural network to generate member-level aggregation. (10) DHRL25 utilizes dual-level HGCN to learn members’/groups’ representation, which is proposed in our previous work.

ConfGR is implemented using the Pytorch framework and trained by exploiting the pairwise loss as the optimization objection. The embedding layer is initialized using the Glorot initialization strategy, as proposed in43. The remaining layers are randomly initialized to follow a Gaussian distribution, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.1. To evaluate the recommendation performance, we utilize the HR@\(\textit{k}\) and NDCG@\(\textit{k}\) metrics44, with \(\textit{k}\) set to {5, 10, 20}.

Overall performance: RQ1

We compare the experimental results of ConfGR with the baselines (shown in Table 3). We note the following key observations: First, most attention network-based methods (i.e. AGREE, SoAGREE, SIGR, CAGR, MoSAN, GroupIM, \(S^{2}\)-HHGR, DHRL and ConfGR) outperform the method without attention mechanisms (i.e. NCF), which demonstrates the superiority of attention mechanisms. Second, SIGR, CAGR, SoAGREE and ConfGR consider user-user interactions and achieve better performance than AGREE which ignores such interactions. Compared with SIGR, CAGR and SoAGREE, ConfGR achieves better performance for two reasons. For one thing, it considers more fine-grained social information to represent members/groups. For another, it integrates self-supervised learning to enhance member-level and group-level group embeddings simultaneously, rather than treating them as two independent tasks. Third, \({S}^{2}\)-HHGR, ConsRec, DHRL and ConfGR are better than most models, which verifies the effectiveness of hypergraphs to describe the high-order relations. ConfGR outperforms \(S^{2}-\)HHGR, which indicates that only considering the groups’ representations at the member level can not fully reflect group preferences. Furthermore, while methods such as \({S}^{2}\)-HHGR, ConsRec and DHRL solely focus on social selection, ConfGR achieves superior results due to the enhanced expressivity offered by its multi-motif HGCN which comprehensively capture both social selection and social influence. This demonstrates the importance of considering multiple social effects for effective group recommendation.

Ablation study: RQ2

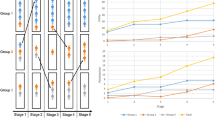

We conduct ablation studies to evaluate the contribution of three core variants: (1) ConfGR-MRL considers group-level preferences, but ignores member-level preferences. (2) ConfGR-GRL considers member-level preferences, but ignores group-level preferences. (3) ConfGR-SSL removes the self-supervised group representation learning module. From the results shown in the left two subfigures of Fig. 5, we have the following observations. First, ConfGR significantly outperforms others on the three datasets in terms of HR@10 and NDCG@10, indicating that MRL, GRL and SSL in our model are beneficial for achieving better performance. Second, when compared to ConfGR-MRL, the performance of ConfGR-GRL demonstrates a significant decline, suggesting that it is indeed crucial to explore the correlation between groups through group-item and group-group interactions. It further implies that the social influence among groups can be beneficial in addressing the issue of sparse group-item interactions.

To study the influence of the conformity on group recommendation performance, the following variants are designed. (1) MRL\(\_\)SS removes the part of member-level social selection modeling. (2) MRL\(\_\)SI removes member-level social influence modeling. (3) GRL\(\_\)SS removes group-level social selection modeling. (4) GRL\(\_\)SI removes group-level social influence modeling. As shown in the right two subfigures of Fig. 5, ConfGR significantly outperforms others in all three datasets on HR@10 and NDCG@10, which verifies the necessity of capturing members’ and groups’ conformity. First, MRL\(\_\)SS performs worse than others, which verifies the importance of learning members’ preferences from user-item interactions. Second, compared with Weeplaces and Douban-Event, group-item interactions in Mafengwo are more sufficient. This enables us to capture more information about group-level social selection. GRL\(\_\)SS discards it, resulting in its performance decreasing significantly in Mafengwo. Third, both MRL\(\_\)SI and GRL\(\_\)SI are worse than ConfGR, which indicates that capturing social influence is indeed necessary.

Impact of hyper-parameters: RQ3

We analyze the effect of hyper-parameters on our model’s performance, and due to space constraints, we only exhibit the results for HR@10 and NDCG@10 metrics (shown in Fig. 6). Similar trends are observed for other values of k. First, we test the performance of ConfGR by varying the values of layer depth from 1 to 4. The results are presented in Fig. 6a. With the increase of convolutional layers, the performance increases and then decreases. One possible reason is that an excessive number of layers may result in the issue of over-smoothing. ConfGR exhibits optimal performance when the layer depth is set to 3. Second, Fig. 6b shows the impact of the number of negative samples. As it increases from 5 to 10, there is a generally upward trend in performance. However, when it exceeds 10, the performance starts to decrease. It means a limited number of negative samples can facilitate the recommendation task, whereas an excessive amount of negative samples can potentially hinder its accuracy. Third, we explore the impact of varying learning rates and batch sizes on the performance of ConfGR. Figure 6c illustrates the performance of our model by varying learning rates. Initially, as the learning rate increases, the performance enhances, but further increments lead to a decline in performance. Figure 6d exhibits the performance of our model when considering distinct batch sizes. We observe that when the batch size is 512, the performance becomes very stable. Therefore, we determine the optimal values for the learning rate and batch size to be 0.05 and 512, respectively. We set the embedding size to 32 after performing a grid search {16, 32, 64, 128} and the magnitude \(\lambda\) of self-supervised learning to 0.9 from {0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1}.

Case study: RQ4

To analyze the model interpretability of our ConfGR, we select some real cases on Mafengwo. Figure 7 shows a group \(g_{172}\) on Mafengwo, and \(v_{2105}\) is a recommended item. For members \(u_{854}\) and \(u_{1191}\), their social selection (SS) is more dominant than their respective social influence (SI), i.e. \(\Pi _{uv}^*\)>\(\Pi _{u{\overline{u}}}^*\). This indicates that they have higher decision-making abilities compared with other members. Therefore, the group preference tends to be consistent with their individual preferences. This would explain why \(v_{2105}\), which \(u_{854}\) and \(u_{1191}\) are interested in, becomes the recommendation result for the group. However, for members \(u_{809}\), \(u_{2116}\) and \(u_{2117}\), the rates of their SS are lower than their respective SI, i.e. \(\Pi _{uv}^*<\Pi _{u{\overline{u}}}^*\), indicating that they may be easily influenced by their peers and compromise with others. This would explain why they can still accept the target item \(v_{2105}\) even though they are not particularly interested in it. Thus our model can provide explanations that the SS effect of \(u_{854}\) and \(u_{1191}\), and the SI effect of \(u_{809}\), \(u_{2116}\) and \(u_{2117}\) jointly promote the generation of recommendation.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a novel explainable group recommendation method for conformity-aware group recommendation. First, we design social-motif HGCN and retail-motif HGCN to learn and aggregate members’ representations, which can dynamically capture the changes in members’ conformity within different groups. Then we develop groupon-motif HGCN and a cross-group line graph to collaboratively learn groups’ conformity. We also integrate self-supervised learning into the model training to jointly enhance group embeddings under different motifs. Our model enables real-time conformity-aware recommendations (e.g., dynamically adjusting group offers on e-commerce platforms based on members’ real-time interactions). The explainable motifs (e.g., visualizing “social leader” vs. “retail follower” roles) enhance user trust by providing transparent insights into group recommendations. For future work, we will (1) incorporate review text via a multi-modal attention mechanism to generate conformity-aware explanations, (2) design counterfactual explanation generators using reinforcement learning to optimize group interventions, and (3) optimize beyond-accuracy objectives (e.g., diversity and coverage).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer algorithms originated during the current study can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rakesh, V., Lee, W. & Reddy, C. K. Probabilistic group recommendation model for crowdfunding domains. In Proceedings of WSDM’16 (Bennett, P. N., Josifovski, V., Neville, J. & Radlinski, F. eds.) . 257–266 (2016).

Liu, X., Tian, Y., Ye, M. & Lee, W. Exploring personal impact for group recommendation. In Proceedings of CIKM’12. 674–683 (2012).

Zhang, K. & Pelechrinis, K. Understanding spatial homophily: The case of peer influence and social selection. In Proceedings of WWW’14. 271–282 (ACM, 2014).

Crandall, D. J., Cosley, D., Huttenlocher, D. P., Kleinberg, J. M. & Suri, S. Feedback effects between similarity and social influence in online communities. In Proceedings of SIGKDD’08. 160–168 (2008).

Zhang, Z. How does conformity psychology affect online consumption behaviors in China? In Proceedings of SDMC’21. 266–274 (2021).

Baltrunas, L., Makcinskas, T. & Ricci, F. Group recommendations with rank aggregation and collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of RecSys’10. 119–126 (2010).

Amer-Yahia, S., Roy, S. B., Chawla, A., Das, G. & Yu, C. Group recommendation: Semantics and efficiency. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2, 754–765 (2009).

Boratto, L. & Carta, S. State-of-the-art in group recommendation and new approaches for automatic identification of groups. Inf. Retrieval Min. Distrib. Environ. 324, 1–20 (2011).

Qin, D., Zhou, X., Chen, L., Huang, G. & Zhang, Y. Dynamic connection-based social group recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 32, 453–467 (2020).

Yu, Z., Zhou, X., Hao, Y. & Gu, J. Tv program recommendation for multiple viewers based on user profile merging. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 16, 63–82 (2006).

McCarthy, J.F. & Anagnost, T.D. MUSICFX: An arbiter of group preferences for computer supported collaborative workouts. In Proceedings of CSCW’00. Vol. 348 (2000).

Tran, L.V. et al. Interact and decide: Medley of sub-attention networks for effective group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGIR’19. 255–264 (2019).

Sankar, A. et al. Groupim: A mutual information maximization framework for neural group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGIR’20. 1279–1288 (2020).

Yuan, Q., Cong, G. & Lin, C. COM: A generative model for group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGKDD’14. 163–172 (2014).

Cao, D. et al. Attentive group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGIR’18. 645–654 (2018).

Yin, H. et al. Social influence-based group representation learning for group recommendation. In Proceedings of ICDE’19. 566–577 (2019).

Yin, H., Wang, Q., Zheng, K., Li, Z. & Zhou, X. Overcoming data sparsity in group recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 34, 3447–3460 (2022).

Cao, D. et al. Social-enhanced attentive group recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 33, 1195–1209 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Double-scale self-supervised hypergraph learning for group recommendation. In Proceedings of CIKM’21. 2557–2567 (2021).

Guo, L., Yin, H., Chen, T., Zhang, X. & Zheng, K. Hierarchical hyperedge embedding-based representation learning for group recommendation. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 40, 1–27 (2021).

Jia, R., Zhou, X., Dong, L. & Pan, S. Hypergraph convolutional network for group recommendation. In Proceedings of ICDM’21. 260–269 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Thinking inside the box: Learning hypercube representations for group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGIR’22. 1664–1673 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Consrec: Learning consensus behind interactions for group recommendation. In Proceedings of WWW’23. 240–250 (2023).

Li, K., Wang, C., Lai, J. & Yuan, H. Self-supervised group graph collaborative filtering for group recommendation. In Proceedings of WSDM’23. 69–77 (2023).

Wu, D., Kou, Y., Shen, D., Nie, T. & Li, D. Dual-level hypergraph representation learning for group recommendation. In Proceedings of WISA’22. 546–558 (2022).

Alaoui, D. E. et al. Deep graphsage-based recommendation system: Jumping knowledge connections with ordinal aggregation network. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 11679–11690 (2022).

Alaoui, D. E. et al. Contextual recommendations: Dynamic graph attention networks with edge adaptation. IEEE Access 12, 151019–151029 (2024).

Alaoui, D. E. et al. Comparative study of filtering methods for scientific research article recommendations. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 8, 190 (2024).

Alaoui, D. E. et al. A novel session-based recommendation system using capsule graph neural network. Neural Netw. 185, 107176 (2025).

He, X. et al. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of WWW’17. 173–182 (2017).

Yoon, S.-E., Song, H., Shin, K. & Yi, Y. How much and when do we need higher-order information in hypergraphs? A case study on hyperedge prediction. In Proceedings of WWW’20. 2627–2633 (2020).

Feng, Y., You, H., Zhang, Z., Ji, R. & Gao, Y. Hypergraph neural networks. In Proceedings of AAAI’19. 3558–3565 (2019).

Yu, J. et al. Self-supervised multi-channel hypergraph convolutional network for social recommendation. In Proceedings of WWW’21. 413–424 (2021).

Zhou, K. et al. S3-rec: Self-supervised learning for sequential recommendation with mutual information maximization. In Proceedings of CIKM’20. 1893–1902 (2020).

Sun, F. et al. Bert4rec: Sequential recommendation with bidirectional encoder representations from transformer. In Proceedings of CIKM’19. 1441–1450 (2019).

Xin, X., Karatzoglou, A., Arapakis, I. & Jose, J. M. Self-supervised reinforcement learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of SIGIR’20. 931–940 (2020).

Yao, T. et al. Self-supervised learning for large-scale item recommendations. In Proceedings of CIKM’21. 4321–4330 (2021).

Xie, X. et al. Contrastive learning for sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of ICDE’22. 1259–1273 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Liao, W., Li, X. & Wang, X. Multi-view self-supervised learning on heterogeneous graphs for recommendation. Appl. Soft Comput. 174, 113056 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Mixed-curvature knowledge-enhanced graph contrastive learning for recommendation. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121569 (2024).

He, Z., Chow, C. & Zhang, J. GAME: learning graphical and attentive multi-view embeddings for occasional group recommendation. In Proceedings of SIGIR’20. 649–658 (2020).

Zhang, S., Zheng, N. & Wang, D. GBERT: Pre-training user representations for ephemeral group recommendation. In Proceedings of CIKM’22. 2631–2639 (2022).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of AISTATS’10. 249–256 (2010).

He, X., Chen, T., Kan, M.-Y. & Chen, X. Trirank: Review-aware explainable recommendation by modeling aspects. In Proceedings of CIKM’15. 1661–1670 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62072084, 62472204 and 62172082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yue Kou conceptualized and designed the model, and prepared the original manuscript draft. Dong Li designed and executed the performance tests, and analyzed the computational results. Derong Shen provided essential theoretical insights and contributed to algorithm improvements. Tiezheng Nie contributed to the development and fine-tuning of the algorithm.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kou, Y., Li, D., Shen, D. et al. A self-supervised group recommendation model with conformity awareness. Sci Rep 15, 35937 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03241-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03241-y