Abstract

Metaphor translation is a complex cognitive process. Previous studies have generally relied on traditional testing methods that primarily focus on completed translation works. The use of dynamic and procedural experimental methods for detection is still lacking. Going beyond previous studies, the current research utilizes eye-tracking and EEG technology to simultaneously record and analyze eye movement indicators and alpha band activity during the metaphor translation process. Eye movement indicators reflect cognitive effort in the context of source text (ST) comprehension, while the alpha band reflects divergent thinking during the translation output stage of the target text (TT). The participants were professional and student translators. The results indicate that the translators exert more cognitive effort in the metaphor translation process compared to the non-metaphor translation process. Additionally, they demonstrate more effective divergent thinking during metaphor translation tasks than during non-metaphor translation tasks. Furthermore, professional translators require less cognitive effort and maintaining a more stable level of divergent thinking. These empirical results suggest that metaphor translation requires not only linguistic abilities for cognitive processing but also divergent thinking skills to find the most appropriate translation solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metaphor is widely used in language, with approximately 70% of expressions in English being metaphorical1. This ubiquity makes metaphor a crucial aspect of language and translation studies. However, translating metaphors presents unique cognitive and linguistic challenges due to their reliance on conceptual mappings and cultural connotations2. Dagut (1987) first raised the issue of metaphor translatability, and since then, metaphor translation has been extensively studied as an essential topic within translation research3. It not only tests the validity of translation theories but also provides insights into the cognitive mechanisms underlying translation processes4,5. One key question that has gained increasing attention is whether translating metaphors requires greater cognitive effort than translating non-metaphorical expressions. Cognitive effort in translation is a critical factor influencing processing efficiency and translation quality6. Investigating the cognitive effort involved in metaphor translation can deepen our understanding of how translators process and produce language under different cognitive loads7,8.

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) suggests that cognitive resources are limited, and tasks requiring higher processing complexity, such as metaphor translation, may increase intrinsic cognitive load, thereby affecting performance and decision-making9,10. Metaphors often involve complex conceptual mappings, where abstract ideas are expressed through more concrete, familiar terms, requiring the translator to engage in deeper inferential reasoning and conceptual reconfiguration. This process of abstract thinking and conceptual reshaping imposes a heavier cognitive load as the translator must recognize figurative meanings, interpret cultural nuances, and often reframe these meanings in a way that aligns with the linguistic and cultural norms of the target language. Translating metaphors often involves additional inferential reasoning and conceptual reconfiguration, leading to greater cognitive demand compared to translating literal expressions11. Individual differences in cognitive load arise from variations in long-term memory knowledge and abilities12. Therefore, in the process of metaphor translation, different translators may experience varying levels of cognitive load. Metaphor translation requires translators to engage in a mental process that involves understanding the metaphor’s figurative meaning, processing it within the context of both the source and target languages, and finding a way to reconstruct the metaphor in the target language while preserving its impact and meaning. This additional mental processing, which often requires drawing on knowledge from different domains, increases the cognitive resources needed and contributes to the heightened intrinsic cognitive load. The translation process, which encompasses “the comprehension of the source text (ST), the production of the target text (TT), and the translation from the ST to the TT”13, is a cognitive endeavor that requires a diverse set of skills, including rapid reading, language comprehension, and translation output abilities14,15. Reading and comprehending the ST serve as the prerequisite and foundation of translation, making it essential to investigate the cognitive effort involved in this aspect of the translation task16. Given these theoretical perspectives, we hypothesize that metaphor translation imposes a higher cognitive burden on translators than non-metaphorical translation, potentially leading to longer processing times and increased cognitive workload.

The translation process involves the cognitive activities of translators. Recording and analyzing these cognitive activities in real time has become essential for studying the translation process17,18. Eye-tracking technology, an emerging tool for translation studies, offers high ecological validity and temporal resolution19,20. During the translation process, eye-tracking reveals when translators shift their attention from the ST to the TT, and it helps observe their choice of translation strategies and cognitive effort in generating translations21,22. Simultaneously, by tracking translators’ eye movements, we can effectively analyze the collaborative process of reading and understanding the ST and producing the TT23,24, with a focus on translators’ attention allocation and decision-making processes in generating the TT25,26. Fixation, regression, and pupil diameter are common indicators used to measure cognitive effort13,27. These eye movement indicators provide an objective and scientific record of how translators process the translated content. By observing and analyzing these eye movement indicators, we can accurately determine which information is received and processed during the reading and comprehension of the ST. This enables us to effectively infer the translator’s cognitive effort as they process the structural and semantic information of the ST. Metaphor translation results in significantly longer fixation times and more regressions than non-metaphorical translation, indicating an increased cognitive load28,29. Pupil dilation—an established physiological indicator of cognitive effort—was greater when participants translated figurative expressions compared to literal ones, supporting the hypothesis that metaphor translation imposes higher cognitive demands30. When translating metaphorical expressions, participants spent more time fixating on source text segments, reflecting the greater mental effort required to decipher metaphors31. Moreover, metaphorical content leads to more complex visual attention patterns, including more frequent re-reading of metaphorical expressions in the source text, suggesting that the cognitive load involved in metaphor translation is significantly higher than that of literal translation32. While existing research provides valuable insights into the cognitive load of metaphor translation, most studies primarily focus on its overall cognitive demands and overlook the influence of individual differences among translators—such as translation experience—on eye movement patterns. Individual differences play a crucial role in shaping cognitive processes12, and translators with different levels of experience may encounter varying cognitive loads when processing metaphorical translations. Therefore, it is essential to consider these differences in eye movement research. This study accounts for individual differences by selecting participants from two distinct groups: professional translators with extensive experience and students with no practical translation experience. Based on existing theories of cognitive effort in translation, we hypothesize that professional translators would exhibit lower cognitive effort (e.g., shorter fixation durations, fewer regressions, and smaller pupil dilations) when translating both metaphorical and non-metaphorical texts compared to students with no practical translation experience. Additionally, by analyzing key eye movement indicators—such as fixation, regression, and pupil dilation—this study aims to uncover differences in cognitive effort between metaphorical and non-metaphorical translations among translators with varying experiences.

Furthermore, translation is a creative endeavor, and among the mental faculties engaged in this process, divergent thinking plays a pivotal role33,34. Divergent thinking skills enhance the expressiveness, vividness, and naturalness of the translation. Since a metaphor involves two distinct entities and serves as a mapping between the source domain and the target domain, divergent thinking is essential in metaphor translation to identify the similarities between them and establish a connection35. The translation process necessitates the engagement of divergent thinking, which is crucial in identifying and resolving complex translation challenges. During the translation process, students can fully exercise their divergent thinking by considering different angles and approaches comprehensively36,37. This enhances their understanding of the text and fosters a flexible mindset, ultimately improving the quality of the translation. The effective use of divergent thinking in translation encourages translators to explore optimal translation expressions from multiple dimensions and perspectives38. Therefore, it is essential to explore divergent thinking during the metaphor translation process.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is one of the most effective tools for identifying and analyzing cognitive processing39. Divergent thinking, being a dynamic and flexible cognitive processing, can be captured and analyzed through EEG experiments. Synchronization within the alpha band can serve as an indicator of an active cognitive process40. When EEG exhibits alpha band activity, imagination and inspiration continue to emanate, resulting in a significant enhancement in judgment and comprehension of stimuli41. Jausïovec (2000) utilized EEG data to examine the alpha band power during divergent thinking tasks42. The findings revealed that participants with high divergent thinking skills exhibited greater alpha band power, particularly in the frontal lobe regions. Fink et al. (2006) further investigated the synchronization of the alpha band in participants engaged in divergent thinking tasks43. The results indicated that responses exhibiting higher novelty were accompanied by increased synchronization within the alpha band. Furthermore, Jung-Beeman et al. (2004) pointed out that, in comparison to non-insight solutions, insight solutions exhibited a higher level of alpha band power44. In this study, we primarily focused on the dynamics of alpha band power, which is closely related to divergent thinking. This analysis aims to elucidate the metaphor translation process during the output stage of the TT. We hypothesize that fully engaging in divergent thinking for creative translation processing can activate alpha band activity. Additionally, by analyzing alpha band activity, this study aims to uncover differences in divergent thinking between metaphorical and non-metaphorical translations among translators with varying experiences.

The fundamental characteristic of thinking in metaphor translation is bilingual cognition, which involves both the comprehension of the source language and the accurate transfer of meaning into the target language. This requires a flexible mode of transformative thinking, involving the interaction, integration, and transformation of cognition in both the source and target languages45. This study will simultaneously examine translators’ cognitive effort during the comprehension process of the source language, as well as their divergent thinking in the process of accurately conveying meaning into the target language, thereby providing more direct and comprehensive evidence for understanding the metaphor translation process.

Materials and methods

Participants

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 to estimate the minimum required sample size. Assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level of α = 0.05, and a power of 0.80, the analysis indicated that a total of 34 participants (17 per group) would be sufficient. To ensure adequate statistical power and account for potential data loss, a total of 40 participants (20 per group) were ultimately recruited. These included 20 professional translators (with an average of three years of translation experience) and 20 student translators (translation majors from a university with no practical translation experience). They had normal vision or corrected-to-normal vision, and no neurological or psychiatric disorders. The experiment received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the university (Ethics Committee of Biology and Medicine in Dalian University of Technology (protocol code: DUTSICE240112-02, 12, January, 2024). Prior to the formal experiment, we conducted a brief pre-experiment. Participants were provided with a reading passage (unrelated to the experimental task content). The time taken to complete the reading was recorded. Based on this time, we calculated each participant’s reading speed (defined as the number of words read per minute). Additionally, several comprehension questions were administered to assess their reading comprehension rate (defined as the number of correctly answered questions divided by the total number of questions). We recorded the reading speed and reading comprehension rate for both groups. The results revealed no significant differences in either reading speed (t = 1.961, p > 0.05) or reading comprehension rate (t = 0.526, p > 0.05). These findings suggest that all participants read at comparable speeds and possessed similar comprehension abilities during the translation tasks.

Experimental materials

We selected a total of 16 English sentences, eight of which contained metaphorical expressions, while the other eight did not. The sentences were of comparable length, ranging from 30 to 50 words, and contained no novel vocabulary or technical terminology. Considering working memory and prior exposure to metaphors, we took into account participants’ familiarity with the text type and topic when selecting the experimental texts. We chose topics that were unfamiliar to all participants to minimize potential biases in the experimental results caused by differences in topic familiarity. To ensure a comprehensive assessment of readability and difficulty, we employed both expert judgment and objective textual complexity measures. Two experts were invited to rate the source texts using a 7-point Likert scale to assess their readability and difficulty, with the scale ranging from 1 (very incoherent) to 7 (highly coherent). This standardized approach helped ensure consistency in expert evaluations. Here are two example sentences: Metaphorical sentence: Life is a canvas, where every choice we make adds a new stroke, crafting a masterpiece that reflects our journey—both the vibrant moments and the more subtle, challenging shades of grey; non-metaphorical sentence: She felt overwhelmed by her emotions and uncertain about the future, yet she remained hopeful, believing that time and circumstances would eventually guide her to a better place. Both experts rated the metaphorical sentence as 5, while their ratings for the non-metaphorical sentence were 5 and 6, respectively. The experts’ ratings showed that the average score for 8 metaphorical sentences was 4.5, while the average score for 8 non-metaphorical sentences was 5. Following Cohen (1960)46, we calculated Cohen’s kappa to assess inter-rater agreement, obtaining a kappa value of 0.81, indicating a high degree of consistency between the experts. To further validate the classification of sentence difficulty, we applied a clustering algorithm to the expert ratings, which grouped both metaphorical and non-metaphorical sentences into the “medium” category. In addition to expert ratings, we employed objective textual complexity measures, including lexical diversity (e.g., Type-Token Ratio), syntactic complexity (e.g., mean dependency distance), and word count. The analysis revealed no significant differences in lexical diversity (t = 0.95, p > 0.1), syntactic complexity (t = 0.103, p > 0.5), and word count (t = 1.05, p > 0.2). These results confirm that the selected sentences were comparable in readability and difficulty.

These texts were then presented on a computer screen, with the font set to Times New Roman, size 24, ensuring uniform visual presentation. The text layout featured 10–13 words per line and double spacing between lines, facilitating readability and reducing fatigue for participants during the experiment. As presented in Fig. 1, we defined Areas of Interest (AOIs) for both metaphorical and non-metaphorical content. Metaphorical content was designated as the (AOI) M, while non-metaphorical content was designated as the (AOI) N. These AOIs were used to extract key gaze parameters (e.g., fixation, regression count, pupil diameter) to investigate cognitive processing.

Experimental procedure

The experiment was conducted in a sound-proof laboratory. Initially, we provided the participants with a brief written explanation of the experiment, including the experimental setup, steps, and the translation tasks to be completed. Each translation task had a time limit of 2 min, requiring participants to respond immediately upon formulating an answer, ensuring that memory capacity was controlled. Additionally, to prevent potential influences on cognitive effort measures, participants were not allowed to revise their translations after completion. Before the experiments, the participants were additionally given warm-up tasks, to help them get used to the experimental setting, the computer, the eye tracker, and the EEG recorder, etc. The order of the translation tasks was reversed for different participants in order to counter the possibility of “retest” or “acclimatization” effect influencing the data. The performance of each participant was recorded on video.

In this experiment, eye movements were recorded using the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 eye tracker, and divergent thinking was recorded using the EMOTIV EPOC X. The eye tracker and EEG recorder were synchronized for measurement via the E-Prime psychological programming software. The participant sat on a chair, facing the PC at a distance of 60 cm, and performed the translation tasks while wearing the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 and EMOTIV EPOC X. During this time, both eye-movement and EEG data were recorded. The eye-movement data were imported into Tobii Studio software on the PC. The EMOTIV EPOC X sent data to the PC via a Bluetooth connection, accessed by the EmotivPRO 3.6.9 software installed on the PC. Data packets were transmitted every second, and by analyzing these packets, numerical data of the alpha band were extracted. The averaged alpha band power was calculated using Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT).

The translation task starts with the presentation of the ‘○’ symbol (Fig. 2). Participants are required to pay close attention to the ‘○’ symbol for a duration of 15 s. After the ‘○’symbol disappears, the translation task will be displayed on the computer screen. The participant then reads the translation task, and the eye-movement indicators, including number of fixations, mean fixation duration, regression count and pupil diameter will be recorded. After having an idea, they will press “ENTER” on the computer keyboard. At this time, the words “Please answer” will be displayed on the computer, and the participants will begin to describe their ideas. Once the narration of ideas is completed, participants press the “ENTER” button again to confirm their ideas. After 5 seconds, the next translation task description will appear on the computer screen again. Each task must be completed within 2 minutes, and the process will be repeated until the final translation task is finished and the eye-movement and EEG data collection is complete.

A longer reference window provides a more stable estimate of resting-state EEG activity and reduces transient fluctuations47,48. Meanwhile, cognitive processing relevant to attention and memory typically occurs within 1s time frame, making it suitable for event-related EEG analysis49. Therefore, in the process of participants performing translation tasks, this experiment selected two time periods of EEG signals for data analysis: Reference (pre-stimulus) interval (10s): 10 s for paying attention to the ‘○’ symbol (2500ms-12500ms); Activation interval (1s): 1 s before hitting “ENTER” after coming up with an idea (1250–250ms before enter). In the reference interval and activation interval, alpha band power (µV2) was calculated by filtering the EEG signals with FFT filters. In order to investigate the changes of the task-related power (TRP) in the alpha band, in each translation task, the (log-transformed) power in the activation interval minus that during the reference interval according to the formula as follows:

If the alpha band power decreased from reference interval to activation interval, the TRP value is negative; If the alpha band power increased from reference interval to activation interval, the TRP value is positive50.

In addition, retrospective interviews were conducted to gather more information on how the translators responded to the translation tasks. The interview questions were designed to explore key findings from the eye-tracking and EEG data. To minimize recall bias, these interviews were conducted immediately after all translation tasks were completed, recorded, and later analyzed for content.

Results and discussion

Quantitative analysis

Eye-movement indicators analysis

We used four values of number of fixations (unit: number), mean fixation duration (unit: s), regression count (unit: times/s), and pupil diameter (unit: mm) as indicators of cognitive effort. Based on the statistical comparison in Fig. 3, t-test was conducted (Table 1). The results show that the four eye-movement values were all significantly higher for the metaphor translation compared to the non-metaphor translation (Number of fixations, t = 16.534, p < 0.001; Mean fixation duration, t = 3.331, p < 0.01; Regression count, t = 5.801, p < 0.001; Pupil diameter, t = 2.121, p < 0.05). It can be seen that metaphor expressions require more cognitive effort during the understanding stage of ST. According to the criteria proposed by Cohen (1988)51 and Sawilowsky (2009)52, the effect size for number of fixations was huge; for regression count, large; and for both mean fixation duration and pupil diameter, medium. It can be seen that metaphor expressions require more cognitive effort during the understanding stage of ST.

The experimental results are consistent with previous research findings53,54,55. The number of fixations and the mean fixation duration reflect the difficulty and depth of cognitive processing. A higher number of fixations indicates greater cognitive processing difficulty, while a longer mean fixation duration suggests deeper cognitive processing. Both are directly proportional to the cognitive effort level of translators56. A higher number of fixations and a longer mean fixation duration during the metaphor translation process indicate that translators exert more cognitive effort. Regression count refers to the number of regressions per second57, which describes the translation process where the eye movement goes in the opposite direction to the source text (ST). The significant increase in regression count by translators during the metaphor translation process indicates that they often employed more meticulous strategies when processing information. Pupil diameter is an eye-tracking indicator used to infer “cognitive processing” and “cognitive load"58. Changes in pupil diameter are considered an indicator of shifts in cognitive effort59. A greater change in pupil diameter indicates that more cognitive effort is being invested in a given translation task. The translators have a larger pupil diameter during the metaphor translation process, suggesting they are expending more cognitive processing effort.

In summary, the results indicate that, compared to non-metaphor translation, the translators encounter greater difficulty with metaphor translation tasks and invest more cognitive effort during the metaphor translation process. In this process, the cognitive effort of the translators significantly increases, as metaphors typically carry deep meanings that rely not only on their literal sense but also on implied emotions, cultural contexts, and symbolic significance. The translators must conduct a thorough analysis of the metaphorical meanings in the source language and understand the multiple layers of meaning behind them. This understanding is often more complex than straightforward language conversion and requires the translators to engage in repeated reflection and judgment throughout the translation process.

TRP in the alpha band analysis

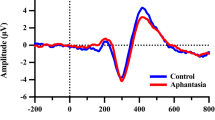

Based on the statistical comparison in Fig. 4, a t-test was conducted (Table 2). The results show that TRP exhibits significant differences between metaphor and non-metaphor translation. Translators showed significantly greater alpha band power increases during metaphor translation compared to non-metaphor translation (t = 9.525, p < 0.001), and the effect size was huge. The results indicate that, during the process of metaphor translation, the translators need to employ divergent thinking more extensively.

The emergence of alpha bands in the brain may indicate that an individual is in a state conducive to divergent thinking60. The results show that the translators exhibited stronger alpha band power increases during metaphor translation, suggesting they were more prone to divergent thinking in this process. This implies that the translators find metaphor translation relatively challenging and fully utilized divergent thinking in their translation tasks. The experimental findings further substantiate the conclusion that metaphor translation poses a formidable challenge in the field of translation61,62.

We also conducted an analysis of TRP values across the entire brain region. Figure 5 shows that all alpha TRP values across the brain were positive, indicating an increase in alpha power from the reference interval to the activation interval. Furthermore, the translators in the metaphor translation process exhibited higher alpha TRP values compared to those in the non-metaphor translation process. These discrepancies were predominantly observed in the anteriofrontal lobe (AF), frontal lobe (F), frontocentral lobe (FC), and temporal lobe (T) regions. Notably, the TRP values in the AF regions were higher than those in other regions for both metaphor and non-metaphor translation, with the metaphor translation showing even higher TRP values in the AF regions compared to the non-metaphor translation.

The alpha TRP values in the AF regions were consistently higher than in other brain regions. Furthermore, non-metaphor translation exhibited greater task-related synchronization of alpha band activity compared to metaphor translation. AF regions play a pivotal role in the development of divergent thinking skills63. The significance of the AF regions in divergent thinking stems from their involvement in cognitive control functions64. During cognition and thinking, the increased alpha wave power generated by the AF regions aids in a deeper analysis of the information being processed65. Divergent thinking requires cognitive abilities such as memory, concentration, and, especially, cognitive flexibility, which is regarded as the core of divergent thinking66. These cognitive abilities are generally associated with the AF regions of the brain. The significant differences in the AF regions suggest that the translators exhibited higher levels of activation during divergent thinking in metaphor translation processes, while during non-metaphor translation, the activation was not as pronounced.

These findings suggest that the translators employ divergent thinking more effectively during metaphor translation. The metaphor translation process requires a greater involvement of divergent thinking, as metaphors often cannot fully convey their meaning through literal translation or simple word substitution. Divergent thinking helps the translators break free from traditional linguistic frameworks and flexibly explore various possible translation solutions, ensuring that the metaphor’s meaning, emotions, and cultural connotations are accurately conveyed and creatively expressed in the target language.

Comparison of professional and student translators

The statistical comparison is shown in Fig. 6. Additionally, we conducted a between-groups analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Prior to performing the ANCOVA, Levene’s test was conducted to assess the homogeneity of variance between professional and student translators. The results indicated equal variances (p > 0.05), confirming the appropriateness of ANCOVA. Translation proficiency was included as a continuous covariate. Table 3 lists the results of descriptive statistical analysis of the professional and student translators in the metaphor translation and non-metaphor translation. After controlling for language proficiency, except for mean fixation duration (metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 1.245, p > 0.05, η2 P = 0.063; non-metaphor translation tasks: F(1,37) = 3.982, p > 0.05, η2 P = 0.097), significant differences were found between the two groups in number of fixations (metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 9.872, p < 0.01, η2 P = 0.211;non-metaphor translation tasks:F(1,37) = 14.327, p < 0.001, η2 P = 0.279) regression count:(metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 12.653, p < 0.01, η2 P = 0.255; non-metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 9.125, p < 0.01, η2 P = 0.198); pupil diameter (metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 15.782, p < 0.001, η2 P = 0.299; non-metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 6.542, p < 0.05, η2 P = 0.150); TRP: (metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 8.457, p < 0.01, η2 P = 0.186; non-metaphor translation: F(1,37) = 10.874, p < 0.01, η2 P = 0.227). The effect sizes for number of fixations, regression count, pupil diameter and TRP was large; for mean fixation duration, medium.

The results indicate that translators of varying experiences demonstrate differing degrees of cognitive effort and divergent thinking, regardless of whether they are engaged in the translation of metaphorical or non-metaphorical tasks. Professional translators expend less cognitive effort than student translators in metaphor translation, both during the comprehension stage of the ST and the translation production stage of the TT in the translation process, and they exercise divergent thinking more effectively. In metaphor translation, the higher efficiency exhibited by professional translators—characterized by shorter mean fixation durations, fewer fixations, lower regression counts, smaller pupil diameters, and greater increases in alpha band power—is primarily attributed to their extensive translation experience rather than solely their language proficiency. Students without translation experience may possess a high level of language proficiency; however, due to their lack of translation practice, they exert significantly greater cognitive effort than professional translators. Translation experience is a key factor influencing both translation efficiency and cognitive effort. Therefore, translation instruction should emphasize practical training to help students gain experience. Providing more metaphor translation exercises and feedback can further support students in mastering translation techniques. Additionally, most individuals are unfamiliar with metaphorical expressions and seldom use them, whereas non-metaphorical expressions are relatively straightforward for most people, facilitating comprehension and translation. Consequently, regardless of translators’ experience levels, they may spend relatively less time translating non-metaphorical expressions and more time on metaphorical expressions. As a result, there are no significant differences in mean fixation duration between professional and student translators when translating both metaphorical and non-metaphorical expressions.

Qualitative analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of how translators responded to the translation tasks, we conducted retrospective interviews immediately after all tasks were completed. The interview data were then integrated and analyzed alongside the eye-tracking and EEG results.

The interview results show that some translators exhibited longer fixation durations during the metaphor translation process, which resulted from their greater investment of cognitive resources in the translation task. For instance, one translator stated, “I fixated longer on the metaphorical translation sentence because I was generating multiple translation possibilities in my mind and then selecting the most appropriate expression after comparison.” Another translator noted, “When I translate a metaphorical sentence, I initially grasp the overall meaning quickly, but I examine it several more times to ensure I identify the most accurate expression, rather than relying on a literal translation.” These findings suggest that the longer fixation durations were not a consequence of the difficulty of metaphors, but rather the outcome of translators actively engaging their cognitive resources for deeper processing.

Some translators exhibited both a higher number of fixations and regression counts during the metaphor translation process. The interview results revealed that these translators often employed more meticulous strategies when processing information, adjusting their expressions to improve translation quality. For instance, one translator stated, “I repeatedly check the sentence structure to ensure that the translation is both faithful and fluent.” Another translator remarked, “For certain expressions, I hesitate initially, so I revisit the original text multiple times to confirm that my understanding is accurate.” These findings suggest that the higher number of fixations and regression counts were the result of translators adopting more cautious and thorough translation strategies, continuously verifying and refining their translations, thereby investing greater cognitive effort.

Some translators exhibited a significant increase in pupil diameter during the metaphor translation process. The interview results revealed that these translators consistently emphasized engaging in more profound cognitive processing during the translation tasks. For example, one translator stated, “Sometimes, I try to translate a sentence in my mind using different expressions to determine which one feels more natural.” Another translator remarked, “I am not merely translating words; I am considering the entire meaning of the sentence, including the author’s intent.” These findings suggest that the increase in pupil diameter was a reflection of translators actively allocating cognitive resources to perform complex semantic transformations and optimize expression.

Finally, EEG data revealed that some translators exhibited increased alpha band activity during the metaphor translation process, a phenomenon typically linked to creative cognitive processing. The interview results indicated that these translators generally emphasized the application of creativity and flexibility, often engaging in meaning transformation rather than adhering strictly to a literal translation. For instance, one translator stated, “Some sentences sound awkward if translated word-for-word, so I try to find an alternative expression to make it sound more natural.” Additionally, another translator remarked, “When I translate, I try not to be constrained by the literal meaning of the original text but instead consider how to express it in a more fluent and contextually appropriate way.” These findings suggest that the enhanced alpha band activity reflects the translators’ effective use of divergent thinking, enabling them to flexibly shift between various expression possibilities.

In summary, the interview results corroborate the interpretation of the eye-tracking and EEG data, indicating that a longer fixation duration, a higher number of fixation and regression counts, and a larger pupil diameter during the metaphor translation process reflect greater cognitive effort invested by the translators. The enhanced alpha band activity observed during the metaphor translation process further reflects the translators’ effective use of divergent thinking.

Limitations and future research direction

This study investigates professional and student translators’ cognitive efforts and divergent thinking in both metaphor and non-metaphor translation processes, providing comprehensive and objective data to support the study of the metaphor translation process. However, certain limitations should be noted. Firstly, this study is relatively small in scale. The limited number of participants may restrict the extent to which the experimental conclusions can be generalized. In the future, it will be necessary to conduct an experiment with a larger sample size to analyze the results further, enhancing the overall generalizability of our findings. Secondly, this study exclusively focuses on English-to-Chinese translation, and differing conclusions may emerge in the context of Chinese-to-English translation. Future investigations could explore translation processing orientations more comprehensively. Thirdly, it’s worth noting that the laboratory setting differs significantly from real-world translation environments. In actual translation scenarios, emotional states and personality traits may interact to influence translation processing. Future research could consider designing laboratory settings that more closely mimic real translation environments. By simulating translation sites with the presence of an audience, participants could engage in experiments under conditions resembling their normal working environments.

Conclusions

This study employs a combination of eye-tracking and EEG technology to monitor and analyze brain activity patterns during the metaphor translation process in real time. Eye-tracking technology captures the eye movements of translators as they read the source text, revealing their attention allocation and information processing strategies. Meanwhile, EEG technology provides direct evidence of changes in translators’ divergent thinking by recording alpha band activity in the cortical regions of the brain. The research results indicate that, compared to non-metaphor translation, the translators invest more cognitive effort in metaphor translation and engage more in divergent thinking. Additionally, both metaphor and non-metaphor translation show that professional translators expend less cognitive effort and exhibit better divergent thinking than student translators. These findings provide valuable insights into the cognitive processing involved in metaphor translation and suggest concrete applications for translation training pedagogy and practice activities. For translation training pedagogy, translation programs could incorporate targeted exercises to foster divergent thinking, particularly in metaphor translation. These exercises could include translating metaphors from various genres, analyzing metaphorical expressions in different languages, and encouraging students to explore creative solutions for metaphor translation. Translation teachers could also apply cognitive load management techniques to help students cope with the increased cognitive demands of metaphor translation, such as scaffolding translation tasks and gradually increasing their complexity as students develop their skills. For translation practice activities, the study highlights the importance of recognizing the cognitive challenges posed by metaphor translation, particularly the increased cognitive effort and divergent thinking required. To address these challenges, the translators can benefit from targeted strategies such as structured brainstorming sessions, comparative analyses of metaphorical expressions across languages, and guided exercises in reinterpreting metaphors creatively. Additionally, incorporating real-world translation tasks that involve metaphorical language, along with expert feedback and peer discussions, can help the translators develop more effective problem-solving skills and enhance their ability to handle complex metaphorical content efficiently.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author Ting Liu on reasonable request via e-mail liuting@dufe.edu.cn.

References

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by 3–35 (University of Chicago Press, 1980).

Schäffner, C. & Shuttleworth, M. Metaphor in translation: possibilities for process research. Target 25, 93–106 (2013).

Dagut, M. More about the translatability of metaphor. Babel 33, 77–83 (1987).

Newmark, P. A Textbook of Translation 67–77 (Prentice Hall International, 1988).

Toury, G. Descriptive translation studies and beyond 32–35 (John Benjamins, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 1995).

Rojo, A. Translation Meets cognitive science: The imprint of translation on cognitive processing. Multilingua 34, 721–746 (2015).

Fantinuoli, C. Interpreting and technology: The upcoming technological turn. in Interpreting and Technology (ed Fantinuoli, C.) 1–12 (Language Science, Berlin, 2018).

Braun, S. Technology and interpreting. in The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Technology (ed O’Haganed, M.) 271–289 (Routledge, London, 2020).

Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 12, 257–285 (1988).

Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 55, 37–76 (2011).

Burmakova, E. A. & Marugina, N. I. Cognitive approach to metaphor translation in literary discourse. Proc.-Social Behav. Sci. 154, 527–533 (2014).

Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory and individual differences. Learn. Individual Differences. 110, 102423 (2024).

Olalla-Soler, C. Practices and attitudes toward replication in empirical translation and interpreting studies. Target 32, 3–36 (2020).

Alves, F. Translation process research at the interface-paradigmatic, theoretical, and methodological issues in dialogue with cognitive science, expertise studies, and psycholinguistics. Psycholinguistic Cogn. Inquiries Transl. Interpret. 17–40 (2015).

Sun, S., Li, T. & Zhou, X. Effects of thinking aloud on cognitive effort in translation. Linguist. Antverpiensia 19, 132–151 (2020).

Alves, F. & Jakobsen, A. L. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Cognition 66–78 (Routledge, 2021).

Ma, X., Han, T. & Li, D. A cognitive inquiry into similarities and differences between translation and paraphrase: Evidence from eye movement data. PLOS ONE 17, e0272531 (2022).

O’Brien, S. Eye-tracking and translation memory matches. Perspectives: Stud. Translatol. 14, 185–205 (2007).

Ren, J., Luo, C., Yang, Y. & Ji, M. Can translation equivalents in L1 activated by L2 produce homophonic interference: an eye movement study of cross-language lexical activation in Chinese english learners. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 52, 743–761 (2023).

Sjørup, A. C. Metaphor comprehension in translation: Methodological issues in a pilot study. in Looking at Eyes: Eye-Tracking Studies of Reading and Translation Processing (eds Göpferich, S., Jakobsen, A. L., Mees, I. M.) Vol. 36 53–77 (Copenhagen Studies in Language, 2008).

Jia, J., Wei, Z., Cheng, H. & Wang, X. Translation directionality and translator anxiety: Evidence from eye movements in L1-L2 translation. Front. Psychol. 14, 1120140 (2023).

O’Brien, S. The borrowers: Researching the cognitive aspects of translation. in Interdisciplinarity in Translation and Interpreting Process Research 5–17 (John Benjamins, Amsterdam, 2015).

Nitzke, J. Problem Solving Activities in post-editing and Translation from Scratch: A multi-method Study11–23 (Language Science, 2019).

Muñoz-Martín, R. Cognitive and psycholinguistic approaches. in The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies (eds Millán, C. & Bartrina, F.) 241–256 (Routledge, New York, 2015).

Marcus, M. Eye tracking sentences in language education. Diacritica 36, 6–36 (2022).

Su, W. C. & Li, D. F. Identifying translation problems in English-Chinese sight translation: An eye-tracking experiment. Transl. Interpret. Stud. 13, 110–134 (2019).

Porras, M. M. et al. Eye tracking study in children to assess mental calculation and eye movements. Sci. Rep. 14, 18901 (2024).

Sjørup, A. C. Cognitive effort in metaphor translation: An eye-tracking and key-logging study [D]. Ph.D. dissertation. (Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, 2013).

Lu, Z. An eye-tracking study on attention resources allocation in the process of sight-translation of english to Chinese metaphors. Foreign Lang. Res. 5, 72–79 (2021).

Hvelplund, K. T. Eye tracking and the translation process: Reflections on the analysis and interpretation of eye-tracking data. MonTI Special Issue — Minding Translation. 1, 201–223 (2014).

Lu, Z. & Zheng, Y. Y. The cognitive processing model of metaphor in sight translation-evidence from eye-tracking and target text analysis. Foreign Lang. Teach. Research. 54, 115–127 (2022).

Zheng, B. H. & Zhou, H. Revisiting processing time for metaphorical expressions: An eye-tracking study on eye-voice span during sight translation. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 50, 744–759 (2018).

Shreve, G. M., Angelone, E. & Lacruz, I. Cognitive effort, syntactic disruption, and visual interference in a sight translation task. In Translation and Cognition (Eds Shreve, G. M., Angelone, E.) (John Benjamins Publishing Company, New York, 2010).

Yu, G. Z. Yu Guangzhong’s Translation Experience (Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press (FLTRP), 2014).

Dorst, A. G. Translating metaphorical mind style: Machinery and ice metaphors in Ken Kesey’s one flew over the Cuckoo’s nest. Perspectives 27, 875–889 (2019).

Nida, E. A. & Taber, C. A. The Theory and Practice of Translating (Shanghai Foreign Language Education, 2004).

Chu, C. S. Intersubjectivity of literary translation from the perspective of integrated dynamic translation. J. Anhui Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2, 63–66 (2014).

Redifer, J. L., & Christine, L. Selfefficacy and performance feedback: Impacts on cognitive load during creative thinking. Learn. Inst. 71, 101395 (2021).

Kalita, B., Deb, N. & Das, D. An EEG: Leveraging deep learning for effective artifact removal in EEG data. Sci. Rep. 14, 24234 (2024).

Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 29, 169–195 (1999).

Liu, C. L., Yu, H. L., Chao, Q. Y., Jia, Q. Y. & Wen, G. H. Alpha ERSERD pattern during divergent and convergent thinking depends on individual differences on meta control. J. Intell. 11, 74 (2023).

Jausïovec, N. Differences in cognitive processes between gifted, intelligent, creative, and average individuals while solving complex problems: An EEG study. Intelligence 28, 213–237 (2000).

Fink, A., Grabner, R. H. & Benedek, M. Divergent thinking training is related to frontal electroencephalogram alpha synchronization. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2241–2246 (2006).

Jung-Beeman, M. et al. Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. Plos Biol. 2, 500–510 (2004).

Huang, Z. L. On outlook and progress of translation thinking research. Foreign Lang. Res. 6, 103–107 (2012).

Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–46 (1960).

Hajihosseini, A. & Holroyd, C. B. Frontal midline theta and N200 amplitude reflect complementary information about expectancy and outcome evaluation. Psychophysiology 50, 550–562 (2013).

Berchicci, M., Lucci, G., Pesce, C., Spinelli, D. & Di Russo, F. Prefrontal hyperactivity in older people during motor planning. NeuroImage 62, 1750–1760 (2013).

Luck, S. J. An Introduction To the Event-Related Potential Technique (MIT Press, 2014).

Pfurtscheller, G. Quantification of ERD and ERS in the time domain. in Event-Related Desynchronization. Handbook of Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, Revised Edition (eds Pfurtscheller, G., Lopes da Silva, F.H.) Vol. 6 89–105 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1999).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn (Erlbaum, 1988).

Sawilowsky, S. S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods. 8, 597–599 (2009).

Koglin, A. An empirical investigation of cognitive effort required to post-edit machine translated metaphors compared to the translation of metaphors. Transl. Interpret. 7, 126–141 (2015).

Hong, W. & Rossi, C. The cognitive turn in metaphor translation studies: A critical overview. J. Translation Stud. 5, 83–115 (2021).

W, Y. The impact of directionality on cognitive patterns in the translation of metaphors. in Advances in Cognitive Translation Studies: New Frontiers in Translation Studies 201–220 (Springer, Singapore, 2021).

Kuperman, V. & Van Dyke, J. A. Effects of individual differences in verbal skills on eye-movement patterns during sentence reading. J. Mem. Lang. 65, 42–73 (2011).

Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 3, 372–422 (1998).

Oliva, M. Pupil size and search performance in low and high perceptual load. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 19, 366–376 (2019).

van der Wel, P. & van Steenbergen, H. Pupil dilation as an index of effort in cognitive control tasks: A review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 2005–2015 (2018).

Klimesch, W., Schimke, H. & Pfurtscheller, G. Alpha frequency, cognitive load and memory performance. Brain Topogr. 5, 241–251 (1993).

Nurbayan, Y. Metaphors in the Quran and its translation accuracy in Indonesian. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 8, 710–715 (2019).

Eleonora, F. The english translation of Grazia Deledda’s La madre and the relevance of culture in translating landscape metaphor. Cadernos De Tradução 40, 112–130 (2020).

Shamay, T. S. G., Adler, N., Aharon, P. J., Perry, D. & Mayseless, N. The origins of originality: the neural bases of creative thinking and originality. Neuropsychologia 49, 178–185 (2021).

Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 167–202 (2001).

Wu, X., Yang, W. & Tong, D. A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on divergent thinking using activation likelihood estimation. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 36, 2703–2718 (2015).

Dietrich, A. The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychol. Bull. Rev. 11, 1011–1026 (2004).

Funding

This research was funded by Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (“An empirical study on the translation process based on neural mechanisms and situated cognition”; Grant number: 21YJC740036); Scientific Research Project of The Educational Department of Liaoning Province of China (Grant number: LJKR0210);Research Project on Undergraduate Teaching Reform for General Higher Education Institutions of Liaoning Province of China (Grant number: No.254 in 2021 from The Educational Department of Liaoning Province); Research Project on Undergraduate Teaching Reform for General Higher Education Institutions of China National Textile and Apparel Council (Grant number: 2021BKJGLX343) ; Research Project on Graduate Education and Teaching Reform of Liaoning Province of China (Grant number: LNYJG2024303); Education Science Research Project under the ‘14th Five − Year Plan’ of Liaoning Province of China (Grant number: JG24DB124).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L.: Methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition. Y.W.: conception and design of the work, analysis of data. Z.W.: writing—review and editing, resources, visualization. H.Y.: supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Biology and Medicine in Dalian University of Technology (protocol code: DUTSICE240112-02, 12, January, 2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Wang, Y., Wang, Z. et al. Exploring cognitive effort and divergent thinking in metaphor translation using eye-tracking and EEG technology. Sci Rep 15, 18177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03248-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03248-5