Abstract

The role of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) in combination with endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) for the treatment of large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke has been evaluated exclusively outside the US, in randomized clinical trials which failed to demonstrate non-inferiority of skipping IVT. Because practice patterns and IVT dosing differ within the US, and prior observational US-based cohorts suggested improved clinical outcomes in patients who received IVT before EVT, a US-based evaluation is needed. This is a quasi-experimental study of a large US cohort using a regression discontinuity design (RDD) that enables the estimation of causal effects when randomization is not feasible. In this multi-center prospective cohort of patients undergoing EVT, we observed a sharp drop (65%) in the probability of receiving IVT at the cutoff of IVT eligibility time window while there were no significant differences in potential confounders including age, NIHSS, and ASPECTS at the cutoff. We found no association between IVT treatment and functional independence (mRS 0–2) at 90-days in patients undergoing EVT, nor in the secondary outcomes of excellent outcomes (mRS 0–1) at 90 days, mortality, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, first pass reperfusion, or final reperfusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and adult disability in the U.S., and of all strokes, 87% are ischemic strokes1. In acute ischemic stroke (AIS), rapid restoration of cerebral blood flow to the affected area before irreversible tissue damage is key to reducing mortality and long-term disability. Treatments involve dissolving the clot with intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) or removing it mechanically using endovascular therapy (EVT). Current guidelines recommend administration of IVT before EVT in all eligible patients with large-vessel anterior circulation stroke (LVO AIS). However, since IVT needs to be given within 4.5 h after symptom onset and the effect of EVT is highly time-dependent, with better outcomes associated with earlier treatment2,3, the use of IVT in combination with EVT for the treatment of LVO AIS has been an area of active study recently. Proposed benefits to skipping IVT include lower cost, lower risk of hemorrhage and potentially changing pre-hospital routing rules to bring all possible LVO patients to EVT-performing hospitals. As an example, the treatment of myocardial infarction shifted from combination of angiography and IVT towards direct coronary intervention two decades ago. This shift in practice was driven by a growing body of evidence indicating that this approach can be both safe and effective in certain patient populations.

Six recent randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a recent meta-analysis conducted in Europe, Asia and Canada studied whether EVT alone is as effective in achieving functional independence at 90 days compared to combination EVT plus IVT for the treatment of LVO AIS4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Two studies conducted in China identified non-inferiority for the EVT-alone approach6,7, but the remaining four trials failed to demonstrate non-inferiority4,5,8,9. A meta-analysis of 2313 individual patient data from these six RCTs did not establish non-inferiority of EVT alone compared with EVT plus IVT in patients11. One study identified reduced rates of reperfusion in patients treated without thrombolysis and produced point estimates that directionally favored combination therapy with improved clinical outcomes5. Importantly, due to regulatory challenges an RCT on this question has been unfeasible in the US, leaving the question of whether combination therapy with IVT is associated with improved outcomes unanswered in this population.

Prior analyses that were inclusive of US-based populations have consisted of non-randomized studies or data from RCTs studying EVT vs. medical management, and a meta-analysis of these data suggested improved rates of functional independence as well as reperfusion in patients treated with combination therapy12,13. Given the confounding effects of tPA contra-indications on the likelihood of these two outcomes and the limitations of retrospective studies, a more rigorous study design to address this topic is needed in a US-based cohort. To address this question and the differences in practice patterns in Europe and Asia compared to the US, we conducted a quasi-experimental cohort study using a large, diverse US cohort with regression discontinuity (RD) analysis. RD is a statistical design that enables the estimation of causal effects, and is particularly relevant when randomization is not feasible, as in this case. Considering the overall results of the randomized clinical trials, we hypothesized that combination therapy with IVT will not demonstrate superiority in functional independence relative to EVT alone, nor will we observe a difference in rates of reperfusion in patients with LVO AIS.

Methods

Overview of RD design (RDD)

RDD is a quasi-experimental method and valid alternative to a RCT for estimating treatment effects by using observational data14. Similar to RCTs, this methodology addresses bias through its design, minimizing the need to measure and control for confounders. In RDD, treatment allocation occurs according to the value of a chosen continuous variable, known as the “running variable” and the probability of exposure to an intervention changes markedly at a certain threshold. Whether an individual lies immediately above or immediately below the threshold is considered effectively random, leading to quasi-random treatment assignment for those close to the threshold. As individuals just above or just below this threshold should differ minimally other than in their receipt of treatment, any discontinuity of the outcome can be interpreted as evidence of a causal effect of the treatment on the outcome. With this design, analysis can be independent of both measured and unmeasured confounding effects15,16,17,18,19,20,21. This study design has been used to address multiple clinical questions, particularly in settings where randomization is not feasible, and its internal and external validity have been confirmed with direct comparisons against traditional RCTs22,23. Moreover, RDD can provide evidence of “real world” effects of treatments, avoiding potential biases introduced by a trial environment.

In this study, the running variable was time from last known well to hospital arrival. We chose this variable as we expected to observe a precipitous drop in the probability of IVT treatment given guideline-based recommendations allowing treatment up to, but not after, 4.5 h from last known well. Study participants that present just before or after the chosen cutoff will have very different chances of receiving IVT but should be largely balanced for other relevant covariables and confounders15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Study population

The study used the data from the SVIN Registry and adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. The SVIN Registry is an ongoing prospective, single-arm, multicenter, observational registry evaluating AIS patients at 12 centers across the US undergoing EVT since 2018. Full details on the registry and its structure have previously been published25. Briefly, the registry was designed to capture a full spectrum of clinical, imaging, and procedural characteristics encountered in clinical practice. All consecutive patients with LVO AIS treated with EVT at participating centers are included.

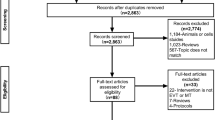

Centers with a thrombectomy database instituted before the inclusion in the SVIN Registry were offered to have their database re-coded by a data analyst to match with the SVIN Registry data dictionary. Therefore, the dataset included patients undergoing EVT for LVO AIS before the inclusion in the SVIN Registry (n = 7035). Our analysis was restricted to cases prospectively collected after the inclusion in the registry (n = 3609). Exclusion criteria were set based on consistency with prior RCTs exploring the same study question (S. Fig. 1). Patients were excluded if they were transferred from a non-EVT performing hospital (n = 1803), in-hospital AIS (n = 229), wake-up stroke (n = 336) or unknown last known well (n = 115) or missing or invalid hospital arrival time (n = 80). In addition, patients who were treated with IVT beyond the 4.5-h guideline-based window (n = 50) or had documented exclusions to IV thrombolysis (concurrent use of anti-coagulation, contraindicated lab values, and recent history of hemorrhage, surgery, trauma, or bleeding) were excluded (n = 253). Finally, given the RD study design, in which only patients presenting close to the cutoff time in the running variable contribute to the overall analysis, we excluded patients who presented after 6 h of last known well (n = 224).

Exposures and outcomes

The primary exposure was treatment with IVT prior to EVT for LVO AIS. All participating centers except for 1 administered alteplase as the standard dose of 0.9 mg/kg, with a 10% bolus dose followed by 1-h continuous infusion throughout the study period. One center administered tenecteplase at a single dose of 0.25 mg/kg intravenous.

The primary outcome in this study was functional independence at 90 days, measured by the 7-point modified Rankin scale (mRS 0–2). This outcome is the standard outcome for EVT-related studies and was also used by the related RCTs. Secondary outcomes included excellent outcome (mRS 0–1) at 90 days, death by 90 days, post-procedural symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) defined using ECASS-II criteria, or the presence of any intracranial hemorrhage (ICH)26. We also evaluated the rates of first pass reperfusion after the first thrombectomy attempt and the final EVT reperfusion grade, which were defined as eTICI 2b to 327.

Study design and statistical analysis

In RD, the assignment can be “sharp” or “fuzzy.” If deterministic, the regression discontinuity takes a sharp design; if probabilistic, the regression discontinuity takes a fuzzy design. Because not all patients below the threshold of time receive IVT in practice, we used a fuzzy RD analysis to estimate the treatment effect of IVT on 90-day functional independence in patients undergoing EVT with time from last known well to hospital arrival as a running variable28,29. The cutoff in this variable was chosen by determining the median time from hospital arrival to initiation of thrombolysis and subtracting this number from the guideline-based cutoff of 4.5 h or 270 min from last known well. In this cohort, the median time from arrival to thrombolysis initiation was approximately 30 [IQR 21–45] minutes. As such, the cutoff in the running variable was chosen a priori to be 240 min. To determine whether there was evidence of systematic manipulation around the cutoff, we carried out McCrary’s manipulation test and found no evidence of density discontinuity around the 240 min cutoff (S. Fig. 2)30,31. Relevant covariables that may be associated with outcomes were determined a priori and analyzed for the presence of any discontinuity at the running variable cutoff. These covariables included age, NIHSS, and baseline ASPECTS.

For each outcome, we reported mean values of them below and above the cutoff and discontinuity at the cutoff, which can be interpreted as the intention-to-treat (ITT) effect of arriving within the eligible time window. The treatment effect was complier local average treatment estimated from two-stage least squares regression approach, where we fitted two linear regressions for the exposure and outcome in relation to the running variable and divided the discontinuity in the probability of outcome at the threshold by the discontinuity in the probability of treatment at the threshold. Discontinuity was measured as the distance between the two linear regressions at the cutoff using local linear regression with separate lines fit on either side of the cutoff in the running variable. In the local linear approach, a bandwidth on either side of the discontinuity is selected, and the linear regression is limited to this region. Doing so reduces the potential bias that may be introduced by variability in curves at time points remote from the cutoff point. Optimal bandwidth size was determined automatically using previously published data-driven methods32,33.

In sensitivity analyses, we manually selected different sizes of the bandwidth by 30 min interval instead of automatic bandwidth selection. We also replaced the local linear regressions with global polynomial regressions of varying degrees. Optimal bandwidth selection and RD estimates were performed using the rdrobust command in STATA (version 17, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX)33,34. The effect of IVT treatment on the primary and secondary outcomes measures are presented as risk difference, with 95% confidence intervals. Baseline characteristics were compared by the receipt of IVT using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables.

Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05 and all analyses were conducted using Stata 17 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Our final cohort from the SVIN Registry included 519 subjects that met inclusion criteria (S. Fig. 1). The distribution of patients in the final cohort for this analysis by year of enrollment and by site are presented in S. Table 1. The cohort includes data from all 12 participating sites across the US and enrollments were from EVT procedures performed from 2018 – 2021.

Among the included study population, the median age was 71 (IQR 60–80), 51.7% were female and median NIHSS was 17 (IQR 12–22). There were no significant differences between the subgroups treated with IVT and those without with a few exceptions (Table 1). Patients treated with IVT tended to present earlier after last known well and have higher ASPECTS and lower prevalence of atrial fibrillation.

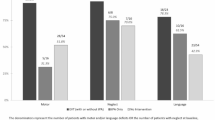

As shown in Fig. 1, we observed a sharp decrease in the probability of receiving IVT at the pre-specified cutoff point of 240 min from last known well to hospital arrival. The discontinuity in risk difference at this cutoff (measured by the difference in intercepts between the linear regressions before and after the cutoff) was -64.7% (95% CI -98.9 to -30.4. Importantly, we did not observe any substantial discontinuities at this cutoff point in other key confounding variables including age (−5.2 years (95% CI −18.1 to 7.8 years)), NIHSS (0.6 points (95% CI −4.6 to 5.7)), and ASPECTS (−1.2 of an ASPECTS level (95% CI −3.7 to 1.4 of an ASPECTS level)). This finding implies that the two groups were well balanced on either side of the cutoff, supporting the assumptions of the RD design and the likelihood that the analysis is balanced on measured and unmeasured confounders. Data on the primary endpoint was available in 444 subjects (85.5%).

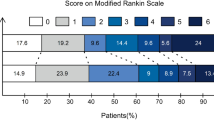

Figure 2 demonstrates the local linear regressions used in the RD analysis of the primary outcome. In local linear approach, we observe no significant discontinuity in the probability of functional independence (risk difference 1.4%, 95% CI, −69.2 to 71.9%) at the threshold and fuzzy RD analysis of the primary outcome demonstrated no association of IVT treatment with the probability of functional independence (risk difference -2.2%, 95% CI −119.7 to 115.2) in patients undergoing EVT (Table 2). For secondary outcomes, we observed non-significant differences in the effect of IVT on excellent functional outcome, sICH mortality, any ICH, first pass reperfusion rate, and final reperfusion grade but none of these were statistically significant (Table 2 and S. Fig 3).

In sensitivity analyses, we repeated analysis for the primary outcome using different manually selected bandwidths. Given the fact that the efficacy of IV thrombolysis is time-dependent, and the likelihood of benefit decreases closer to the 4.5-h time limit, we performed these sensitivity analyses with bandwidths incorporating earlier time points. We found no statistically significant effect of IVT (S. Table 2). When we repeated analysis with polynomial order with varying degrees, no significant effect of IVT on the primary outcome was observed as well (S. Table 2).

Discussion

In this multicenter cohort including 12 EVT centers across the US, we found no association between functional independence at 90 days and treatment with IVT in patients undergoing EVT for LVO AIS. Thrombolytic therapy was also not associated with symptomatic ICH or improved rates of reperfusion. These findings are overall consistent with the prior clinical trials performed outside the US, which failed to demonstrate superiority or non-inferiority of EVT alone versus in combination with thrombolysis. Our results represent novel evidence to support these trial data using a large, diverse US-based cohort.

Six RCTs showed similar results, but there were important differences. While the two Chinese trials concluded that an EVT-only approach was non-inferior, the other four studies performed in Europe, Australia, Japan, and Canada did not4,5,6,7,8,9. SWIFT-DIRECT found decreased rates of substantial reperfusion in patients who did not receive thrombolysis, whereas the other studies did not. Further, some trials required specific devices to be used for the thrombectomy procedure, while others had no restrictions5. The SKIP trial administered alteplase at the standard dose in Japan, of 0.6 mg/kg, as opposed to the 0.9 mg/kg dose used in the US4. Thus, while these studies provide a wealth of information on this topic, their results may not be readily generalizable to a US-based population. In addition, due the fact that race and ethnicity may influence this treatment effect, as implied by the differences in results between the Chinese and non-Chinese trials, AIS care in the US can be vastly different from these other regions.

To date, the highest quality data that included US-based populations were from retrospective cohort studies and meta-analyses of these studies combined with data from RCTs designed for other purposes. In many of the retrospective analyses, IVT was not associated with improved outcomes, but in some IVT treatment demonstrated superior rates of functional independence and substantial reperfusion relative to EVT-alone12,35. A recent large meta-analysis found overall benefit and identified improved rates of final reperfusion lower rates of mortality with IVT treatment in conjunction with EVT36. These differences, however, were not upheld in the RD design, and this difference highlights the need to account for confounding variables with this study question. Given the fact that an RCT was not feasible in the US, this quasi-experimental design provides meaningful data in a US-based cohort.

One advantage of this study design relative to RCTs is the inclusion of consecutive patients treated in routine clinical practice, without strict parameters surrounding EVT eligibility. In the previous RCTs, cohorts were limited by age, occlusion location, ASPECTS, type of thrombectomy device, and other parameters. On the other hand, this study had a much more pragmatic design. While one disadvantage of using a registry cohort is the increased frequency of missing data (14% missing 90-day mRS) relative to more structured RCTs, results drawn from registry obtained in routine clinical practice may be more easily generalizable compared to those from rigid RCT environments.

Due to its design, RD analyses can minimize bias from confounding variables to a greater extent than previous non-randomized studies. Here, we found no evidence of discontinuity among key potential confounding variables, a finding that supports RD methodology in the ability to balance co-variables to a comparable degree as randomization. It is also likely that unmeasured or unanticipated confounding variables would also be balanced. Further, our exposure variable (IVT treatment) showed a sharp discontinuity at the pre-specified cutoff point. The magnitude of this discontinuity is similar or greater to those used in other RD studies, further validating the RD approach to this study question23,37. However, one of the limitations of the RD design is its dependence on a subset of patients near the cutoff point. In this analysis, while the overall cohort size was larger, the primary analysis was performed on a smaller cohort adjacent to the cutoff point, resulting in wider confidence intervals.

It is worth noting that the rate of functional independence observed in this study (41%) is slightly lower than several of the clinical trials11. This percentage in the trials ranged from 36 to 65%. This difference is again likely secondary to the pragmatic nature of the dataset, which captures all consecutive EVTs at participating sites including those with pre-stroke disability, who may have greater pre-existing disability and for other reasons may have been ineligible for previous trials38.

Our study has several limitations. It is possible that with a larger sample size, we may have been able to resolve a very small discontinuity in function independence with IVT treatment. On the other hand, we saw no signal of effect in the primary analysis nor the multiple associated sensitivity analyses. Further, it is possible that at time points more distant from the cutoff point, there is a greater effect of IVT treatment on outcome in patients undergoing EVT39. This is particularly relevant as the benefit of tPA is strongest when administered soon after stroke onset. This finding has been demonstrated in prior studies involving patients treated in mobile stroke units, in which alteplase administered within the “golden hour” is more efficacious, as well as in the IRIS meta-analysis40,41. It is worth noting that in multiple recent real-world EVT registries, the majority of tPA eligible patients present much closer to the end of the 4.5-h eligibility window. The recent COMPLETE study of 650 EVT patients reported onset to arrival of nearly 200 min, and the US-based STAR registry of nearly 6500 patients reported an average onset to EVT initiation time of 4.3 h in IV tPA treated patients, implying onset to hospital arrival of at least 3 hours42,43. In addition, in our sensitivity analysis that expanded the bandwidth to cover earlier time points, we saw so no difference in our results. As such, the findings of this study likely apply to the majority of EVT patients in clinical practice.

Here, we examine the benefit of IVT in patients undergoing EVT for LVO AIS in a US-based cohort, and we find no association of IVT on clinical outcomes nor hemorrhage rates, consistent with findings of RCTs performed outside the US. We also find no association with recanalization rates, nor first pass reperfusion.

Data availability

The dataset used in this analysis is available to all members of the SVIN Registry consortium. Membership into the consortium is open to all research institutions as detailed on the consortium bylaws24. Any further inquiries can be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 145(8), e153–e639 (2022).

Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 50, e344–e418 (2019).

Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischaemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379(9834), 2364–2372 (2012).

Suzuki, K. et al. Effect of mechanical thrombectomy without vs with intravenous thrombolysis on functional outcome among patients with acute ischemic stroke. JAMA 325(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23522 (2021).

Fischer, U. et al. Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous alteplase plus thrombectomy in patients with stroke: an open-label, blinded-outcome, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 400(10346), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00537-2 (2022).

Zi, W. et al. Effect of endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous alteplase plus endovascular treatment on functional independence in patients with acute ischemic stroke. JAMA 325(3), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.23523 (2021).

Yang, P. et al. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. New Engl. J. Med. 382(21), 1981–1993. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2001123 (2020).

LeCouffe, N. E. et al. A randomized trial of intravenous alteplase before endovascular treatment for stroke. New Engl. J. Med. 385(20), 1833–1844. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2107727 (2021).

Mitchell, P. J. et al. DIRECT-SAFE: A randomized controlled trial of DIRECT endovascular clot retrieval versus standard bridging therapy. J. Stroke 24(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2021.03475 (2022).

Masoud, H. E. et al. Brief practice update on intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke: A statement from society of vascular and interventional neurology guidelines and practice standards (GAPS) committee. Stroke Vasc. Intervent. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1161/svin.121.000276 (2022).

Majoie, C. B. et al. Value of intravenous thrombolysis in endovascular treatment for large-vessel anterior circulation stroke: individual participant data meta-analysis of six randomised trials. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01142-x (2023).

Mistry, E. A. et al. Mechanical thrombectomy outcomes with and without intravenous thrombolysis in stroke patients. Stroke 48(9), 2450–2456. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.117.017320 (2018).

Du, H. et al. Intravenous thrombolysis before mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Hear Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 10(23), e022303. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.022303 (2021).

Chaplin, D. D. et al. The internal and external validity of the regression discontinuity design: a meta-analysis of 15 within-study comparisons. J. Polic. Anal. Manag. 37(2), 403–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22051 (2018).

Maciejewski, M. L. & Basu, A. Regression discontinuity design. JAMA 324(4), 381–382. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3822 (2020).

van Leeuwen, N. et al. Regression discontinuity was a valid design for dichotomous outcomes in three randomized trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 98, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.02.015 (2018).

Moscoe, E., Bor, J. & Bärnighausen, T. Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: a review of current and best practice. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.021 (2015).

Bor, J., Moscoe, E., Mutevedzi, P., Newell, M. L. & Bärnighausen, T. Regression discontinuity designs in epidemiology. Epidemiology 25(5), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000138 (2014).

Venkataramani, A. S., Bor, J. & Jena, A. B. Regression discontinuity designs in healthcare research. BMJ 352, i1216. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1216 (2016).

Oldenburg, C. E., Moscoe, E. & Bärnighausen, T. Regression discontinuity for causal effect estimation in epidemiology. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 3(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-016-0080-x (2016).

Maas, I. L. et al. The regression discontinuity design showed to be a valid alternative to a randomized controlled trial for estimating treatment effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 82, 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.11.008 (2017).

Boon, M. H., Craig, P., Thomson, H., Campbell, M. & Moore, L. Regression discontinuity designs in health. Epidemiology (Camb. Mass) 32(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000001274 (2021).

Goulden, R., Rowe, B. H., Abrahamowicz, M., Strumpf, E. & Tamblyn, R. Association of intravenous radiocontrast with kidney function. JAMA Intern. Med. 181(6), 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0916 (2021).

SVIN Registry. https://www.svin.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3553. (Accessed 29 August 2023).

Haussen, D. C. et al. The society of vascular and interventional neurology (SVIN) mechanical thrombectomy registry: Methods and primary results. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1161/svin.121.000234 (2022).

Hacke, W. et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet 352(9136), 1245–1251 (1998).

Liebeskind, D. S. et al. eTICI reperfusion: defining success in endovascular stroke therapy. J NeuroIntervent. Surg. 11(5), 433. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014127 (2019).

Imbens, G. W. & Lemieux, T. Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. J. Econ. 142(2), 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.001 (2008).

Cattaneo, M. D., Idrobo, N. & Titiunik, R. A Practical Introduction to Regression Discontinuity Designs (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Cattaneo, M. D., Jansson, M. & Ma, X. Manipulation testing based on density discontinuity. Stata J. 18(1), 234–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1801800115 (2018).

McCrary, J. Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. J. Econ. 142(2), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.005 (2008).

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D. & Farrell, M. H. Optimal bandwidth choice for robust bias-corrected inference in regression discontinuity designs. Econ. J. 23(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/ectj/utz022 (2019).

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., Farrell, M. H. & Titiunik, R. Regression discontinuity designs using covariates. Rev. Econ. Stat. 101(3), 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00760 (2019).

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., Farrell, M. H. & Titiunik, R. Rdrobust: Software for regression-discontinuity designs. Stata J. 17(2), 372–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x1701700208 (2017).

Rai, A. T. et al. Intravenous thrombolysis before endovascular therapy for large vessel strokes can lead to significantly higher hospital costs without improving outcomes. J NeuroIntervent. Surg. 10(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012830 (2018).

Wang, Y., Wu, X., Zhu, C., Mossa-Basha, M. & Malhotra, A. Bridging thrombolysis achieved better outcomes than direct thrombectomy after large vessel occlusion. Stroke 52(1), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.031477 (2021).

Sukul, D. et al. Association between medicare policy reforms and changes in hospitalized medicare beneficiaries’ severity of illness. JAMA Netw. Open 2(5), e193290. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3290 (2019).

Siegler, J. E. et al. Endovascular vs medical management for late anterior large vessel occlusion with prestroke disability. Neurology 100(7), e751–e763. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000201543 (2023).

Kaesmacher, J. et al. Time to treatment with intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy and functional outcomes in acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA 331(9), 764–777 (2024).

Mackey, J. et al. Golden hour treatment with tPA (tissue-type plasminogen activator) in the BEST-MSU study. Stroke 54(2), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.039821 (2023).

Kaesmacher, J. et al. Time to treatment with intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy and functional outcomes in acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA 331(9), 764–777. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.0589 (2024).

Akbik, F. et al. Bridging thrombolysis in atrial fibrillation stroke is associated with increased hemorrhagic complications without improved outcomes. J. NeuroIntervent. Surg. 14(10), 979–984. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017954 (2022).

Zaidat, O. O. et al. Endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke with the penumbra system in routine practice. Stroke 53(3), 769–778. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.121.034268 (2022).

Funding

Dr. Sheth reports grant funding from the NIH (R01NS121154). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

YK and SS designed and performed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. SSM, RA, and AI performed data extraction and cleaning and contributed to the draft of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to data collection and provided feedback on the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Salazar-Marioni, S., Abdelkhaleq, R. et al. Comparison of thrombectomy alone versus bridging thrombolysis in a US population using regression discontinuity analysis. Sci Rep 15, 18757 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03249-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03249-4