Abstract

In-situ synthesis of g-C3N4 containing nitrogen vacancies and cyano group via one-pot method using urea as the precursor. The structural, morphological or electrochemical properties of synthesized photocatalysts were characterized by XRD, BET analysis, TEM, FTIR, UV-DRS, PL, XPS and EPR. It was found that the nitrogen vacancy was successfully introduced into g-C3N4. Compared to pure g-C3N4, the (200) crystal plane in XRD of synthesized g-C3N4 showed slight red-shift, and the BET surface areas had changed from 27.5 to 35.7 m2·g−1, which could provide more reaction center and active site. TEM confirmed that g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 were porous materials, and FTIR, XPS as well as EPR could prove the presence of nitrogen vacancies and cyano group. The UV-Vis absorption edge of VN-g-C3N4 demonstrated briefly red-shift, PL intensity and lifetime of carriers declined in comparison with pure g-C3N4. Electrochemical test results showed that enhanced charge separation efficiency and low recombination rate of charge carriers of VN-g-C3N4. The photocatalytic activity of the photocatalysts was researched by RhB degradation and ACT removal under visible light irradiation, the results showed the rate of RhB degradation on the VN-g-C3N4 was 81%, which was 1.4-fold as high as that of g-C3N4 in visible light. The degradation contribution from the active species were h+ (67.3%) >1O2(63.0%)>•OH (49.4%) >•O2− (20.3%) > e− (20.1%) > H2O2(0.2%), and VN-g-C3N4 exhibited excellent ACT removal rate, which was 1.6-fold higher than that of pure g-C3N4 in visible light. This study provides an efficient photocatalyst for the treatment of toxic wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of modern society, environmental issues are becoming increasingly severe. Organic pollutants such as pharmaceuticals and dyes, closely related to human life, are widely present in the environment1. Acetaminophen, the most widely used over-the-counter pain reliever and antipyretic globally, has an annual consumption of hundreds of thousands of tons. It enters the environment in large quantities through human waste, industrial wastewater, and the disposal of expired drugs. The accelerated advancement of modern society has exacerbated environmental challenges. Persistent organic pollutants, including pharmaceutical compounds and synthetic dyes, which are intrinsically linked to human activities, have become ubiquitous in ecosystems. Notably, acetaminophen (paracetamol), the globally predominant over-the-counter analgesic and antipyretic, is consumed at an annual rate exceeding hundreds of thousands of metric tons2. This pharmaceutical agent permeates environmental systems primarily through domestic sewage, industrial effluents, and improper disposal of pharmaceutical waste. Acetaminophen and its partially degraded products possess biological toxicity and accumulative properties, potentially causing damage to liver and kidney functions upon long-term low-dose exposure. Furthermore, prolonged exposure may elevate the risk of chronic illnesses, posing a threat to human health. Photocatalytic technology offers an eco-friendly approach to efficiently degrade acetaminophen. By harnessing light to activate photocatalysts, this technology generates reactive oxygen species that rapidly oxidize and thoroughly mineralize acetaminophen3. The reaction proceeds under ambient temperature and pressure, requiring neither high temperatures nor high pressures. It boasts low energy consumption, high safety standards, and operates on light energy without generating secondary pollution. The photocatalysts are reusable, thereby reducing costs and minimizing waste. Additionally, this technology boasts a broad application scope, capable of treating pollutants present in various environmental media and at different concentrations.

As a metal-free polymeric semiconductor photocatalyst, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) had been attracted intensive attention4. The g-C3N4 was composed of tris-triazine (C6N7) unit. Its abundant source, non-toxic, inexpensive, excellent thermal and chemical stability, easy preparation process and narrow band gap structure (~ 2.7 eV vs. NHE)5, which beneficially promoted it as an appropriate visible-light responsive photocatalyst for organic pollutants removal6, photocatalytic hydrogen production7, photocatalytic nitrogen fixation8, CO2 photoreduction9 and photocatalytic NOx removal10. However, it still suffered from unavailability of sunlight beyond 460 nm, small BET surface area and high recombination rate of electron-hole pairs owing to the absence of active sites11. To address these challenges, several modification methods have been employed. Among these, bandgap engineering is a prevalent technique for enhancing the properties of g-C3N4 materials. This approach can improve the light absorption capacity of g-C3N4, extend the light absorption into longer wavelength regions, and facilitate charge separation and transmission. During the photocatalytic process, photogenerated electrons and holes tend to recombine, which diminishes photocatalytic efficiency. Bandgap engineering can alter the energy band structure to create an appropriate energy level distribution, thereby inhibiting charge recombination and extending charge lifetimes. Furthermore, bandgap engineering can enhance both the photocatalytic reaction rate and selectivity; additionally, the introduction of defects can increase the number of active sites. By adsorbing reactant molecules to lower the activation energy, this method can further promote photocatalytic reactions and enhance photocatalytic activity12. Dong et al. designed and prepared g-C3N4 with stacked coral like magnetic sulfur doped nitrogen vacancies by combining polymerization and precipitation. The 0.1 g/L photocatalyst could photocatalytic degradation 5 mg/L of 2,4,6-TCP to 95% within 60 min under visible light. This high removal rate was attributed to nitrogen vacancies, which widened the visible light absorption range and shortened the electron transfer path13. Li et al. successfully synthesized g-C3N4 with nitrogen vacancy network structure for photodegradation of Propylparaben. Compared with bulk g-C3N4, it shows larger specific surface area, stronger light absorption capacity, higher charge carrier transfer and separation efficiency. According to the characterization results and density functional theory calculations, nitrogen vacancies can capture electrons and promote the adsorption of oxygen. The Propylparaben removal rate of the best sample is 94.3%, which is 3.37 times higher than that of the bulk g-C3N414. Nguetsa Kuate et al. synthesized black g-C3N4 photocatalyst by one-step calcination of urea and phloroglucinol B for the degradation of tetracycline in seawater under visible light irradiation. The experimental results showed that the photocatalytic degradation rate of tetracycline was 92% within 2 h at room temperature, which was 1.3 times that of pure g-C3N4. This excellent photocatalytic degradation can be attributed to the reduction of charge transfer distance due to the thickness of ultra-thin nanosheets, the separation of photogenerated carriers promoted by cyano defects and the enhancement of photocatalytic activity due to the photothermal effect of the material15.

The enhancement of specific surface area and the formation of defects serve as pivotal factors in boosting the catalytic activity of materials. An increased specific surface area offers more active sites, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity for reactants. Meanwhile, the emergence of defects alters the electronic structure of the materials, accelerating the separation and migration of carriers. Together, these two factors synergistically elevate the catalytic efficiency from the perspectives of adsorption and reaction kinetics. Inspired by the above, we prepared g-C3N4 material with rich defects via one-pot in-situ synthesis, and thoroughly discussed the mechanism of photocatalytic reaction of g-C3N4 material with rich nitrogen vacancies and cyano group. The precursor was heat-treated under nitrogen atmosphere and then forming nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups, which could validly narrow the bandgap, enhance visible light absorption, and promote the separation of photo-generated electrons/holes. Therefore, the g-C3N4 with rich nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups could greatly improve photocatalytic performance for Acetaminophen and RhB degradation.

Experiment

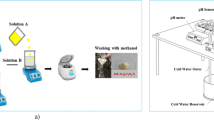

Synthesis of catalysts

Bulk g-C3N4 was synthesized by thermal polymerization of urea under air condition. 6 g urea and 1 mL deionized water were fully mixed and placed in a covered crucible, heated to 100 ℃ at a heating rate of 0.5 ℃/min and kept at 100 ℃ for 1 h, then continued heating to 500 ℃ at a heating rate of 5 ℃/min and kept at 500 ℃ for 2 h at air condition. The synthesis method of g-C3N4 with rich nitrogen vacancies was similar to Bulk g-C3N4, The only difference was the reaction atmosphere was nitrogen instead of air. The g-C3N4 with rich nitrogen vacancies was labelled as VN-g-C3N4.

Characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were tested to determine the phase structures of prepared materials using Rigaku D/max2200PC diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method was carried out on ASAP2020, the specific surface area and pore size were analyzed by nitrogen adsorption-desorption test. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were performed by a Bruker-VERTEX80v spectrometer. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-ARM300 F) measurement was performed to check the microstructure of the samples. UV-vis diffuse reflectance absorption spectrum in the range of 200–800 nm was recorded on Cary 5000, of which BaSO4 was used as reference. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) and VBXPS were collected on an AXIS SUPRA utilizing the reference of C1 s (284.6 eV) with an excitation source of 150 W Al Kα X-rays (1486.6 eV). The photoluminescence (PL) spectra and time-resolved fluorescence decay spectra of catalysts were analyzed by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Edinburgh Instruments, FS5) equipped with xenon lamp source (150 W) at an excitation wavelength of 340 nm.

Photocatalytic and electrochemical test of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements, photocurrent intensity response measurements and Mott–Schottky curve were measured by an electrochemical workstation (CHI600E, China) based on a conventional three electrode cell. 10 mg of catalyst on glassy carbon electrode substrate (1 cm×1 cm) was used as working electrode. The graphite electrode and Ag/AgCl electrodes were used as counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The Na2SO4 aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte (0.2 mol L−1, 200 mL). The frequency range was from 10−2 Hz to 105 Hz, and the amplitude of the applied sine wave potential in each case was 5 mV for the EIS measurements. Incident light was obtained from a 300 W xenon lamp. The photocatalytic activity of catalsyts was tested by degradation of RhB in an aqueous solution under 40 W LED white lamp. Firstly, catalsyts samples (30 mg) were mixed with RhB aqueous solution (50 mL, 30 mg/L). After stirring for enough time in dark to achieve adsorption equilibrium, the catalyst was collected and placed again in the RhB solution with same concentration to test the photocatalytic properties. The percentage of degradation was recorded as C/C0, where C and C0 referred to the absorbance of the RhB solution after a certain time interval (30 min) and the initial absorbance corresponding to concentration, respectively. Acetaminophen (ACT) was degraded under 8 W LED lamp. Firstly, the photocatalyst (10 mg) was mixed with ACT aqueous solution (10 mg/L, 50 ml) to achieve adsorption equilibrium, and then the photocatalyst was centrifuged collected and put into the solution under the same conditions to test the photocatalytic performance.

The detection of free radicals and trapping experiments of active species under visible-light

The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiment was tested on Bruker EMX-plus instrument, which discovered the free radicals in reaction. Samples for EPR measurement were executed by using DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-l-pyrroline N-oxide), DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP) as the spin trapping agent (reagent concentration 0.1 mol L−1, catalyst concentration 50 mg/L.) under visible light. We used isopropanol (IPA), Catalase (CAT), L-Histidine, P-benzoquinone (PBQ), Triethanolamine (TEOA) and AgNO3 as quenchers of hydroxyl (•OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), singlet oxygen (1O2) super oxygen (•O2−), holes (h+) and electron (e−), respectively. Catalysts (30 mg) containing different trapping agents (0.01 mol/L) were distributed in 50 ml RhB solution (30 mg/L) for characterizing photocatalytic performance.

Results and discussion

The microstructure, composition and morphology of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 samples were measured by XRD. Figure 1a presented two characteristic XRD peaks of samples, the strong diffraction (002) peak at about 2θ = 27.2° was associated with the interlayer stacking of aromatic systems and the low-angle (100) peak at 2θ = 13.1° was corresponded to repeating motifs of in-plane tri-s-triazine units structure for g-C3N4 (JCPDS NO.87–1526)16. VN-g-C3N4 exhibited the same typically characteristic peaks as that of g-C3N4, which confirmed its basic triazine framework of g-C3N4 without changing the basic structure of during N2 treatment. Compared with g-C3N4, the XRD peaks of VN-g-C3N4 was broadened and weakened, suggesting that the in-plane orderly structure clearly decreased and the interlayer stacking became less order. Partially enlarged image (Fig. 1b) was observed as the peak at 27.2° has shifted to 27.7°. According to the Bragg diffraction equation, the slight shift of peak (002) to the positive direction could be decreased in interlayer stacking distance from 0.328 to 0.322 nm, which might be due to the N-atomic variation in the plane. The structural properties of materials were analyzed by the N2 adsorption-desorption measurement. Figure 1c showed that all the isotherms were type IV with hysteresis loops of type H3 at a relative pressure range of 0.6–1.0, demonstrating the presence of mesoporous. The BET surface area gradually subjoined from 27.5 m2 g−1 (g-C3N4) to 35.7 m2 g−1 (VN-g-C3N4). The increase of BET surface area might be owing to the nitrogen-vacancy defects in the structural units. The Barret-Joyner-Halenda analysis of pore size distributions from 2 to 30 nm for g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 in Fig. 1d, showing the introduction of nitrogen vacancies significantly increased specific surface area and provided abundant active reaction sites for photocatalytic reaction.

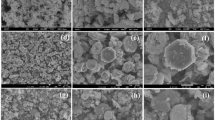

Figure 2 showed the TEM images of the g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4, porous morphology was observed on the g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 surface. The porous structure was beneficial for photogenerated electron and hole transmission, extended carrier life and excellent capture ability. The surface of g-C3N4 sample (Fig. 2a) was fully glossy. However, the surface of VN-g-C3N4 sample (Fig. 2b) showed the state of intertwined nanosheets, demonstrating the presence of nitrogen vacancy on the VN-g-C3N4 surface. The SAED pattern revealed that bright continuous concentric rings owing to diffraction by the (002) planes of VN-g-C3N4. Therefore, we could inferred nitrogen vacancy were formed in the heat-treatment process at nitrogen atmosphere.

FTIR spectra was a very useful tool for analysis of variable chemical structure in material. As shown in Fig. 3, the VN-g-C3N4 sample showed the typical FTIR patterns which was similarly to that of g-C3N4, suggesting the basic atomic structure of g-C3N4 was still remained after the different atmosphere. The broad peak at 3000–3500 cm−1 was originated from N-H stretching vibration or O-H adsorbed hydroxyl species and amino group from precursor17. The bond strength of VN-g-C3N4 was enhanced, suggesting more content of N-H or O-H in VN-g-C3N4. The peaks in the region from 850 to 1800 cm−1 corresponded to skeletal vibration of C-N-C, C-N and C = N in aromatic ring. The sharp absorption peak at 812 cm−1 owing to the bending mode of the 3-s-triazine unit, illustrating the existence of the basic melon units with NH/NH2 groups. Compared with g-C3N4, the peak of VN-g-C3N4 was weaken trend, indicating it had less heptazine rings. The presence of nitrogen vacancy broke the structure of the triazine skeleton and decrease the content of NH/NH2 groups. A distinct peak at 2175 cm−1 of VN-g-C3N4 had stronger than that of g-C3N4, which corresponded to asymmetric stretching vibration of cyano-groups18. The terminal C ≡ N triple bond carried positive charge and acted as electron acceptor for accelerating the charge transfer, which was formed during the opening of s-triazine heterocycles and the lattice N loss. The formation of nitrogen vacancy and cyano groups could improve the photocatalytic performance.

Figure 4a-b showed the UV–Vis DRS and the calculated bandgap for the g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4. In Fig. 4a, compared with g-C3N4, the absorption edges of VN-g-C3N4 displayed a slight red-shift. The band gap values in Fig. 4b showed that the band gap of samples narrowed from 2.63 eV (g-C3N4) to 2.56 eV (VN-g-C3N4). A narrower band gap was achieved, which should be due to the introduction of nitrogen vacancies. To know the separation and transfer efficiency of photoexcited electron-hole pairs, the steady PL results under the excitation wavelength of 340 nm were shown in Fig. 4c. The peak at about 470 nm was stemmed from the direct electron (e−) and hole (h+) recombination of band transition. Wherein VN-g-C3N4 with a amount of nitrogen vacancies clearly exhibited much lower intensity than g-C3N4, indicating that the recombination of carriers of VN-g-C3N4 could be basically inhibited after introduction of nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups, since the nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups could trap photogenerated electrons for promoting the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes19. Besides, to comprehend the charge-separation kinetics, the exciton lifetime was calculated by fitting the time-resolved PL decay curves (Fig. 4d) and the average lifetime (τav) was depended on the following equation, where B and τ denoted the relative amplitude and decay lifetimes, respectively.

The parameters in this equation were given in Table 1. The short lifetime (τ1) was owing to electrons trapped in shallow states and the long lifetime (τ2) corresponded to deep states before the recombination with the holes in the VB. The τav for VN-g-C3N4 (8.40 ns) was shorter than that of g-C3N4 (10.87 ns), indicating enhanced electron and hole dissociation. The outstanding decrease in PL intensity and lifetime of carriers was attributed to the nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups, which might improve the efficiency of charge carrier transfer and enhance photocatalytic reaction activity.

The XPS analysis was performed to further investigate the chemical bond valence information of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4. The survey spectra was shown in Fig. 5a. For g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4, the total peak of C 1 s (Fig. 5b) was consisted of three peaks: C–C/C = C (284.6 eV), C–NH/C–OH (286.2 eV) and N = C–N (288.1 eV). The N 1 s peak of g-C3N4 in the high-resolution spectra (Fig. 5c) was composed of three peaks, which corresponded to N–2 C (398.6 eV), N–3 C (399.8 eV) and N–H (401.1 eV). It was interesting that N–3 C peak of VN-g-C3N4 slightly negatively shifted from 399.8 to 399.5 eV, which might be due to the formation of cyano. It was noteworthy that the peak ratio between N–2 C and N–3 C significantly declined from 2.785 for g-C3N4 to 1.578 for VN-g-C3N4, indicating the loss of N–2 C during thermal polymerization under nitrogen atmosphere. Figure 5d showed the O 1 s spectra peak at 532.3 eV was ascribed to the hydroxyl or adsorbed water. The peak intensity at 532.3 eV of VN-g-C3N4 was stronger than that of g-C3N4, showing that the VN-g-C3N4 could easily absorb dye molecules during the dye degradation owing to the presence of nitrogen defects. The existence of lone electron-pair in photocatalysts was further verified by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. If there were nitrogen vacancy in g-C3N4-based materials, a single Lorentzian line with a g value around 2.0025 could be observed in EPR spectroscopy, which can be attributed to the unpaired electrons on sp2-carbon atoms within the π-conjugated aromatic rings20. Figure 5e showed the EPR signal intensity of VN-g-C3N4 was sharply decreased in comparsion with g-C3N4, which might be owing to oxygen atom replaced nitrogen atom forming covalent bonds with C and reducing the number of unpaired electrons. Based on the results of XPS and EPR, as illustrated in Fig. 5f, the structural schematic of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 was derived from urea as the primary substance under varying atmospheric conditions.

To further comprehend the charge transfer and separation efficiency, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and transient photocurrent responses were tested by electrochemical workstation. As shown in Fig. 6a, The semicircle of high frequency in the Nyquist plot implied a charge transfer process, and the diameter of the semicircle reported the charge transfer resistance. The smaller diameter of the VN-g-C3N4 suggested a quicker charge transfer process after introducing cyano groups and nitrogen vacancies, showing that cyano groups and nitrogen vacancies acted active center for reducing the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 displayed positive photocurrents by several on-off cycles. Moreover, the photocurrent intensity of VN-g-C3N4 was higher than g-C3N4, indicating VN-g-C3N4 had more charge separation efficiency by introducing cyano groups and nitrogen vacancies (Fig. 6b). Figure 6c demonstrated the Mott-Schottky plots of the functional relationship of 1/C2 and applied potential. The positive Mott-Schottky plots slope suggested that g-C3N4 and VN-C3N4 were classified as a n-type semiconductor. The intercept of Mott-Schottky plot at the abscissa was considered as the flat band position, which was − 1.28 V and − 1.15 V (versus NHE) for g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4, respectively. The flat band level was approximately equal to the conduction band minimum22. According to flat band level and Eg, the energy-band structure diagram of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 were shown in Fig. 6d. As shown in the figure, the valence band position, conduction band position, and band gap width of g-C3N4 are 1.35 eV, −1.28 eV, and 2.63 eV, respectively. Similarly, the valence band position, conduction band position, and band gap width of VN-g-C3N4 are 1.41 eV, −1.15 eV, and 2.56 eV, respectively.

Rhodamine B dye was selected as the simulated degradation material in this experiment. The photocatalytic activity of samples were tested via RhB degradation as found in Fig. 7a. Adsorption for 1 h in the dark environment to achieve the adsorption–desorption equilibrium before the photodegradation. The RhB removal rate of g-C3N4 was about 58% in 120 min. In comparison, the RhB photodegradation of VN-g-C3N4 was significantly improved after the appearance of nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups, VN-g-C3N4 presented 81% of RhB removal in 120 min. The rate constant for RhB degradation by VN-g-C3N4 was about 1.4 times that of g-C3N4. Thus, the formation of nitrogen vacancies and cyano groups were beneficial for providing more active sites for charge separation efficiency and photocatalytic reaction.

Wherein, c0 represents the initial concentration of the reactant, ct denotes the reaction time, t signifies the concentration of the reactant at a given time, and k stands for the apparent first-order rate constant.According to the results of RhB removal results, the relevant kinetic characteristics constants were shown in Fig. 7b. RhB photocatalytic degradation reaction was conformed with first-order reaction kinetic equation23. k for g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 were 0.0072 and 0.0132 min−1, respectively. Figure 7c illustrates the degradation rate of g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 after being irradiated in an ACT solution for 2 h. In the absence of a photocatalyst, the degradation rate achieved through visible light irradiation over 2 h is merely 2%. The degradation rate of g-C3N4 stand at 56.3%. However, by introducing defects, the degradation rate of VN-g-C3N4 in 2 h reaches 94.6%, representing a significant increase of 47 times compared to the case without photocatalyst and 1.6 times higher than that of g-C3N4 prior to modification. This phenomenon can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, nitrogen vacancies disrupt the crystal and electronic structures, altering the energy bands and thereby expanding the visible light absorption range, leading to the generation of more photogenerated carriers. Secondly, acting as electron trapping centers, they inhibit carrier recombination and optimize migration pathways to enhance migration efficiency. Simultaneously, an increase in surface active sites enhances the adsorption and activation of reactants, reducing the activation energy of the reaction. Furthermore, by regulating oxygen adsorption, it facilitates the formation of superoxide radicals, singlet oxygen, and other highly oxidative reactive oxygen species, ultimately enhancing the photocatalytic performance of the material in a comprehensive manner.

Degradation of RhB over VN-g-C3N4 with IPA, CAT, L-Histidine, PBQ, TEOA and AgNO3 as quenchers (a). EPR spectra of superoxide radicals (•O2−) (b) hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (c), and singlet oxygen (1O2) (d) spin-trapped by DMPO, DMSO and TEMP, respectively. EPR conditions: reagent concentration 0.1 mol L−1, catalyst concentration 50 mg/L.

To further understand the RhB photodegradation process, isopropanol (IPA), Catalase (CAT), L-Histidine, P-benzoquinone (PBQ), Triethanolamine (TEOA) and AgNO3 were used as quenchers for hydroxyl (•OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), singlet oxygen (1O2) super oxygen (•O2−), holes (h+) and electron (e−), respectively. As shown in Fig. 8a, the degradation rate of RhB dropped to 31.0%, 60.1% and 60.3% after the addition of IPA, PBQ and AgNO3, respectively. The removal of RhB suggested no obvious change while the introduction of CAT into the system. However, when TEOA and L-Histidine were added as scavengers for h+ and 1O2, the RhB degradation was declined from 80.4 to 13.1% and 17.4%, respectively. Thus h+ and 1O2 had played an important role in RhB removal. In order to determine which active group played important role in the photocatalytic process, DMPO, DMSO and TEMP were chosen to investigate •OH, •O2− and 1O2 radicals. Under dark conditions, no signals of •OH, •O2− or 1O2 radicals could be surveyed in any of the g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 systems (Fig. 8b-d).

Under the light conditions, •O2− could not be detected in either g-C3N4 or VN-g-C3N4 systems, indicating •O2− was not major active group in photocatalytic reaction. •OH signal was appeared in g-C3N4 system but not in VN-g-C3N4 system, •OH signal of g-C3N4 system exhibited a 1:2:2:1 quadruple EPR signal, which was ascribed to DMPO − OH substance21. g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 had low valance band and could insufficiently oxidize water to •OH (Eθ(•OH/H2O) = + 2.34 V vs. NHE)24, suggesting •OH in VN-g-C3N4 system couldn’t be further formed by O2. 1O2 signal was found in both g-C3N4 and VN-g-C3N4 systems, which exhibited a 1:1:1 triple EPR signal due to the presence of TEMPO obtained by the oxidation of TEMP by 1O225. However, the EPR intensity of 1O2 signal for VN-g-C3N4 was much weaker than g-C3N4, which showed there were much more 1O2 content in g-C3N4 due to nitrogen vacancy could effectively capture electrons and limit the movement of photogenerated electrons26. thus, the schematic diagram of pollutant degradation and formation pathways of free radicals of VN-g-C3N4 in the photocatalytic system was described in Fig. 9a-b. The oxygen species adsorbed on the material’s surface combine with photogenerated electrons to produce superoxide radicals, which then undergo oxidation by holes to transform into singlet oxygen active species. These active species catalyze the oxidation of pollutants within the system, effectively degrading them.

Conclusions

In summary, g-C3N4 containing nitrogen vacancies and cyano group was successfully synthesized by one-pot method using urea as the precursor. Compared with normal g-C3N4, the degradation rates of RhB and ACT were increased by 1.4 times and 1.6 times, respectively, indicating that the improvement in photocatalytic efficiency is attributed to enhaned BET surface area and introduction of nitrogen vacancy and cyano group, which broadened the spectrum and increased electron transfer efficiency. The capture experiment of active species shows that h+ and 1O2 are the main active species. Therefore, this study provides an effective reference for designing stable, safe, and efficient photocatalysts and treatment processes to remove highly toxic organic pollutants in water environments.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ammar, S. H. et al. Enhancing visible-light-based photodegradation of antibiotics over facile constructed BiVO4/S-doped g-C3N4 heterojunctions in an airlift photocatalytic reactor[J]. J. Water Process. Eng. 65, 105900 (2024).

Ali, A. H. & Alwared, A. I. Solar-photocatalytic degradation of Paracetamol using Zeolite/Fe3O4/CuS/CuWO4 Pn heterojunction: synthesis, characterization and its application[J]. Sol. Energy. 290, 113383 (2025).

Hameed, M. S. et al. Assembly of 2D/2D Bi2WO6/Boron-doped g-C3N4 Z-type heterojunction photocatalysts for efficient antibiotic adsorption and degradation[J]. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 180, 108591 (2024).

Ali, F. D. et al. Boosting visible-light-promoted photodegradation of Norfloxacin by S-doped g-C3N4 grafted by NiS as robust photocatalytic heterojunctions[J]. J. Mol. Struct. 1312, 138611 (2024).

Abdulmajeed, Y. R. et al. Photocatalytic improvement mechanism of SnO2/Sn-doped gC3N4 Z-type heterojunctions for visible-irradiation-based destruction of organic pollutants: Experimental and RSM approaches[J]11101096 (Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 2025).

Zhou, B. et al. Enhanced Fenton-Like catalysis via interfacial regulation of g-C3N4 for efficient aromatic organic pollutant degradation[J]. Environ. Pollut. 356, 124341 (2024).

Yan, Y. et al. Engineering of g-C3N4 for photocatalytic hydrogen production: A Review[J]. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (16), 8842 (2024).

Dang, H. et al. Construction of P-N charge-transfer Bridge in porous g-C3N4 for highly efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic N2 fixation[J]. Appl. Surf. Sci. 653, 159307 (2024).

Qaraah, F. A. et al. One-step fabrication of unique 3D/2D S, O-doped g-C3N4 S-scheme isotype heterojunction for boosting CO2 photoreduction[J]. Mater. Today Sustain. 23, 100437 (2023).

Xia, Y. et al. Promoting the photocatalytic NO oxidation activity of hierarchical porous g-C3N4 by introduction of nitrogen vacancies and charge channels[J]. Appl. Catal. B. 344, 123604 (2024).

Kumar, P. et al. Multifunctional carbon nitride nanoarchitectures for catalysis[J]. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52 (21), 7602–7664 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Progress in preparation, identification and photocatalytic application of defective g-C3N4[J]. Coord. Chem. Rev. 510, 215849 (2024).

Dong, Z. et al. Enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation to 2, 4, 6-trichlorophenol with magnetic sulfur doping constructed nitrogen vacancies in g-C3N4: spectrum broaden, photogenerated electron acceleration and degradation pathway shorten[J]. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12 (5), 113772 (2024).

Li, Y. W. et al. Solar-induced efficient Propylparaben photodegradation by nitrogen vacancy engineered reticulate g-C3N4: morphology, activity and mechanism[J]. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159247 (2023).

Nguetsa Kuate, L. J. et al. Photothermal-assisted photocatalytic degradation of Tetracycline in seawater based on the black g-C3N4 nanosheets with cyano group defects[J]. Catalysts 13 (7), 1147 (2023).

Yao, Q., Chen, K. & Oh, W. C. Direct Z-scheme photocatalytic removal of ammonia via the narrow band gap BiOCl/g-C3N4 hybrid catalyst upon visible light irradiation[J]. Fullerenes Nanotubes Carbon Nanostruct. 32 (6), 621–629 (2024).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Facile synthesis of N vacancy g-C3N4 using Mg-induced defect on the amine groups for enhanced photocatalytic• OH generation[J]. J. Hazard. Mater. 449, 131046 (2023).

Song, S. et al. Single-color and two-color femtosecond pump–probe experiments on graphitic carbon nitrides revealing their charge carrier kinetics[J]. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127 (22), 10617–10628 (2023).

Wei, D. et al. Dual defect sites of nitrogen vacancy and cyano group synergistically boost the activation of oxygen molecules for efficient photocatalytic decontamination[J]. Chem. Eng. J. 462, 142291 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Precise Defect Engineering with Ultrathin Porous Frameworks on g-C3N4 for Synergetic Boosted Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution[J]632665–2675 (Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2024). 6.

Zhu, D. & Zhou, Q. Nitrogen doped g-C3N4 with the extremely narrow band gap for excellent photocatalytic activities under visible light[J]. Appl. Catal. B. 281, 119474 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Fabrication of Z-scheme Bi7O9I3/g-C3N4 heterojunction modified by carbon quantum Dots for synchronous photocatalytic removal of cr (VI) and organic pollutants[J]. J. Hazard. Mater. 446, 130663 (2023).

Lu, Z. et al. Flexible roles of TiO2 in enhancing carrier separation for the high photocatalytic performance of water treatment under different spectrum sunlight[J]. J. Water Process. Eng. 66, 106021 (2024).

Xi, Y. et al. Engineering an interfacial facet of S-scheme heterojunction for improved photocatalytic hydrogen evolution by modulating the internal electric field[J]. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13 (33), 39491–39500 (2021).

Maksimchuk, N. V. et al. Resolving the mechanism for H2O2 decomposition over Zr (IV)-Substituted Lindqvist tungstate: evidence of singlet oxygen Intermediacy[J]. ACS Catal. 13 (15), 10324–10339 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Mechanism insight into enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production by nitrogen vacancy-induced creating built-in electric field in porous graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets[J]. Appl. Surf. Sci. 631, 157544 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by General Research Project of Basic Science (Natural Science) in Higher Education Institutions of Jiangsu Province (No. 23 KJB430035), outstanding young backbone teachers in the Blue and Blue Project in Jiangsu Provincein in 2025 (BI Xiang) and excellent teaching team in the Blue Project of Jiangsu Province universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiang BI, Gao-Hui DU and Li-Zhong WANG wrote the main manuscript text and Dong-Hua ZHAI prepared Fig 7. Hui YANG and Lei WANG prepared literature research and conclusion verification. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bi, X., Wang, LZ., Zhai, DH. et al. In-situ synthesis of g-C3N4 with nitrogen vacancy and cyano group via one-pot method for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Sci Rep 15, 19864 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03286-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03286-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Synergic Combination of g-C3N4/V2O5/PANI Ternary Nanocomposite for Energy and Environmental Applications

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)