Abstract

In this study, the structural, electronic, optical, mechanical, and phonon properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl, F) halide perovskites were investigated using first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Structural stability was confirmed via the Birch–Murnaghan equation of state, revealing a cubic perovskite structure for both compounds. LiSbCl3 exhibited a larger lattice parameter (5.5345 Å) compared to LiSbF3 (4.6784 Å) due to the heavier chlorine atoms. Electronic band structure analysis confirmed their metallic nature, characterized by a continuous band of energy states. Optical analysis demonstrated strong ultraviolet absorption and reflection, with LiSbCl3 displaying a high dielectric constant (11.25 at 0.10 eV) and an optical conductivity peak of 4684 Ω−1 cm−1 at 10.54 eV, whereas LiSbF3 exhibited a lower dielectric constant (2.99 at 4.48 eV) and a conductivity peak of 1579 Ω−1 cm−1 at 13.44 eV. Mechanical stability analysis indicated that LiSbCl3 is ductile with a positive shear modulus (8.39 GPa), while LiSbF3 is mechanically unstable with a negative shear modulus (− 16.68 GPa). These findings highlight the potential of LiSbCl3 for energy storage, optoelectronic, and photonic applications, while further optimization is required for LiSbF3 to enhance its mechanical stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the world’s population and economy expand, so does the need for energy1. However, the fossil fuels used to meet this demand are quickly running out, and their combustion releases harmful CO2 emissions2,3,4,5,6. This situation calls for new, clean, and reliable energy sources. Perovskite materials (ABX3) have shown promise for use in photovoltaics (PV), the most common type of solar technology7,8,9,10,11,12. Perovskites have unique properties that make them efficient at generating electricity from sunlight13,14,15,16,17. One type of perovskite, organic–inorganic halide perovskite (OIHP), has recently received a lot of attention for its potential in PV technology.

Perovskite materials stand out in solar energy technology due to their exceptional properties for converting sunlight into energy18,19,20,21. Initially discovered for their piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties in the 1990s22, perovskites have since become widely used in solar cells as absorber layers. Their potential has also expanded to applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and renewable energy conversion devices, showcasing their versatility and high efficiency. As a result, perovskite materials have become a major focus of global research and development, contributing to the pursuit of sustainable energy solutions. Lead-based perovskites had potential but were too harmful to the environment and human health23,24,25. They could contaminate water and soil, and damage people’s health26,27,28,29. To address this issue, researchers have been looking for different materials to use in perovskites instead of lead. To make solar cells and other electronics safer and more eco-friendly, researchers have started using non-toxic metals like tin Sn2+, germanium Ge2+, antimony Sb3+, and bismuth Bi3+ instead of lead Pb2+ in perovskite materials30,31,32,33. These lead-free materials are better for the environment and work just as well in solar cells, light detectors, and lights25,28,34,35.

Additionally, there are promising new materials being explored, such as lithium-based halide perovskites29,36,37,38,39, lead-free perovskites40,41,42,43,44, and fluoro/chloro-perovskites45,46,47,48,49, which have shown great potential for use in energy conversion and electronic applications.

These materials have advantageous properties for solar cells, thermoelectric devices, LEDs, and transistors. They have ideal band gaps, high thermoelectric performance, absorb visible light, and have stable structures. For instance, Mohammad Sohail et al., have found that Tl-based fluoroperovskites have a stable structure, large band gaps (5.7 eV and 5.6 eV), and strong optical qualities, making them useful for semiconductor and optoelectronic applications50. Similarly, cubic perovskites such as CdYF3 and CdBiF3 (studied by Nasir Rahman and colleagues), CdXF3 (where X is either Y or Bi) materials are structurally strong, resistant to deformation, and flexible51. CdYF3 has an indirect band gap of 2.056 eV, while CdBiF3 has a direct band gap of 1.027 eV. These materials also have a high shear resistance, a combination of ionic and covalent bonding, and intricate dielectric and optical properties. This makes them promising candidates for next-generation electronic devices.

Asif Hosen has shown that the compound Sr₃BCl3 (B = As, Sb) becomes more conductive and gets a smaller energy gap between its electronic bands when pressure is applied. This makes these materials suitable for applications in optoelectronics. Pressure also improves their mechanical stability and optical properties, making them adaptable for use in various advanced devices52.

Research has investigated the properties of RbSrM3 (M = Cl, Br) halide perovskites using density functional theory. Riaz et al. found that RbSrCl3 and RbSrBr3 have direct band gaps of 7.73 eV and 6.79 eV, respectively, along with promising optical and mechanical qualities53. Rashid et al. observed that rubidium-based halide perovskites (RbSnX3 (X = Cl, Br)) exhibit reduced band gaps and enhanced optical properties at high pressure, while maintaining mechanical stability and ductile characteristics54.

We are studying two unique materials, of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) which are part of a new group of compounds made with halides and fluorine. We chose these materials because they have a special combination of properties related to their structure, electrical behavior, and ability to interact with light. They also meet the growing need for energy solutions that are both efficient and good for the environment. of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) perovskites have ideal electrical properties, are chemically stable, and can withstand external forces well. These materials have unique properties that make them ideal for capturing sunlight in solar cells and manipulating light in optoelectronic devices. By deeply understanding these properties, we can create new materials that will advance the development of clean energy technologies like solar panels and light-based electronics.

Computational methodology

DFT simulations using the Wien2k code were carried out to analyze the structural, optoelectronic, and elastic traits of LiSbF3 and LiSbCl355. A plane-wave basis was used. For structural and elastic properties, the GGA method with the PBE functional was utilized. However, for electronic and optical properties, the TB-mBJ potential was employed, as it offers a more precise depiction of the electronic band structure25,56,57,58.

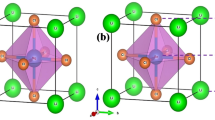

Using a conjugate gradient algorithm, the crystal structures and atomic arrangements of the compounds under study were determined. The optimized crystal parameters were then employed to construct equations of state (EOS) utilizing various formalisms, including Birch-Murnaghan59, Vinet-Rose, Poirier-Tarantola, and EOS2.

To make sure the energy levels obtained are stable and accurate, the size of the local atomic region (muffin-tin radius, RMT) was carefully chosen. For lithium and fluorine atoms, RMT was set to 2.5 atomic units (a.u.), while for antimony, it was 2.19 a.u. The product of RMT and the energy cutoff for the plane waves (Kmax) was approximately 7. A Monkhorst–Pack grid60 with 6 × 6 × 6 points was used to sample the Brillouin zone. The energy cutoff was − 6.0 Rydberg (Ry), and a dense k-point mesh of 2000 points was employed. This ensured that the energy difference between consecutive iterations was less than 0.001 Ry, ensuring reliable and accurate results.

Results and discussions

Structural properties

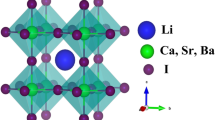

LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) form cubic crystal structures with well-defined symmetry (space group 221). LiSbCl3 also has a cubic structure (Pm-3m), but with a larger lattice parameter (a = 5.5345 Å) due to the presence of larger chlorine atoms. The atomic arrangement includes lithium at (0, 0, 0), antimony at (0.5, 0.5, 0.5), and chlorine atoms at specific coordinates [(0, 0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0, 0.5), (0.5, 0.5, 0)] shown in Fig. 1. The radii of these atoms within the Wigner–Seitz unit cell are 2.5 Å for lithium, 2.5 Å for antimony, and 2.28 Å for chlorine. This structure has 48 symmetry operations, contributing to its high symmetry and stability. The computed lattice constants were cross-validated with previous DFT studies and available experimental results, which confirm the reliability of our calculations.

LiSbF3 has a precise cubic shape with a lattice parameter of 4.6784 Å. Within the crystal lattice, the atoms are arranged as follows: Lithium at the center (0, 0, 0), Antimony at the midpoint (0.5, 0.5, 0.5), Fluorine at the midpoints of each face (0, 0.5, 0.5), (0.5, 0, 0.5), and (0.5, 0.5, 0) shown in Fig. 1. The corresponding radii of atomic spheres (Wigner–Seitz radii) are: Lithium: 2.5 Å, Antimony: 2.19 Å, Fluorine: 1.98 Å The high symmetry of the cubic structure is supported by the existence of 48 symmetry operations. Furthermore, these compounds have specific bulk properties. LiSbCl3 has a bulk modulus of 27.2730 GPa, and its equation of state, described by the Birch–Murnaghan equation (Eq. 1),

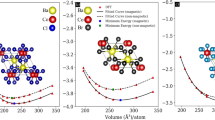

Table 1 lists estimates for the ground state energy (E0), volume (V0), bulk modulus (B), its pressure sensitivity (B'), and equilibrium lattice constant (a0) calculated using the GGA approximations. When a system reaches its E0 minimum, it becomes structurally stable as this state has the lowest energy. The corresponding volume is called V0. The fitting results indicate that both compounds have a sharp energy–volume curve (Fig. 2), meaning that the energy reaches its minimum at a specific volume.

The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) in Eq. 2 evaluates the stability of perovskite structures63.

For both LiSbF3 and LiSbCl3, t is approximately 0.708, indicating stability due to the similarity in ionic radii of their components. Despite the larger size of chloride ions, structural parameters compensate, resulting in identical t values. This t value, slightly below the ideal range, suggests minor structural distortion but supports stable perovskite phases. This stability makes these materials promising lead-free alternatives for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications.

The Birch–Murnaghan equation was chosen for its reliability in describing the pressure–volume relationship in these materials, enabling determination of equilibrium lattice parameters and calculation of bulk modulus. This equation confirms structural stability by predicting equilibrium volume and providing bulk modulus values, indicating material stiffness. Its suitability lies in handling large volume changes and wide applicability, making it ideal for studying LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) halide perovskites structural stability and potential applications.

Band structures

By studying the structure of the electron energy bands of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) which is displayed in Fig. 3, it’s evident that these materials behave like metals because their conduction and valence bands overlap. This overlap is a key feature of metals since it means that even in extremely cold conditions, electrons can move freely, enabling easy electrical conduction.

LiSbCl3 and LiSbF3 have distinct electrical properties. Figure 3 shows how their energy bands overlap a lot. This creates a lot of energy states at the Fermi level, making these compounds excellent electrical conductors. The overlap between the conduction band (mainly Sb-p states) and valence band (containing Cl–p or F–p states) at the Fermi level results from the electron-rich nature of antimony and strong hybridization of Sb orbitals with halogens. This interaction leads to the delocalization of electrons within the crystal lattice, a characteristic of metals. The intrinsic electron configuration and orbital interactions in the crystal lattice give these materials their metallic properties, making them promising candidates for applications in energy systems, electronic circuits, and devices that require high electrical conductivity and low resistance.

Density of states (DOS)

Analyzing the Density of States (DOS) for LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) unveils their electronic structures and confirms their metallic character displayed in Fig. 4. Both compounds exhibit a substantial number of states at the Fermi level (EF), a characteristic of metallic systems. Non-zero states at EF indicate an abundance of charge carriers, rendering these materials highly conductive. The DOS breakdown shows the influence of individual atomic orbitals, showcasing the impact of specific elements on the materials’ electronic and conductive properties.

In LiSbCl3, the atoms are arranged in such a way that the electrons available near the Fermi level (the energy level at which electrons flow) are mostly derived from the antimony (Sb-5p) atoms. However, there is also a noticeable contribution from the chlorine (Cl-3p) atoms. These Sb-5p and Cl-3p orbitals interact strongly, leading to the formation of wide bands of energy levels. These bands make it easy for electrons to move around within the material, giving it a metallic character. Below the Fermi level, there is a prominent cluster of energy levels corresponding to where the Cl-3p and Sb-5p orbitals overlap. Above the Fermi level, the energy levels are mainly from the Sb-5p orbitals. The continuous distribution of energy levels across the Fermi level means that LiSbCl3 has no bandgap (the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands), allowing for the smooth flow of electrons.

LiSbF3 exhibits metallic properties due to a high number of electron energy states at its energy reference level. The flow of electric current is mainly controlled by antimony’s (Sb) 5p states. Fluorine’s (F) 2p states have a significant impact on the lower energy range. The bonding of Sb 5p and F 2p orbitals allows electrons to move more freely, contributing to the metallic nature. Just below the energy reference, there is an energy peak resulting from a mix of Sb 5p and F 2p orbitals. Above the energy reference, the energy states of the conduction band are continuously distributed. The blending of the valence and conduction bands at the energy reference emphasizes LiSbF3's metallic behavior. Fluorine’s higher electronegativity than chlorine in LiSbF3 enhances F-2p state influence, leading to refined electronic interactions and heightened metallicity. The density of states (DOS) analysis provides deeper insight into the metallic behavior of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F). The DOS profile reveals a significant contribution from the Sb-5p orbitals near the Fermi level, indicating their dominant role in electrical conductivity. Additionally, the Cl-3p and F-2p orbitals exhibit considerable hybridization with Sb-5p states, reinforcing the metallic nature of these materials. This strong interaction suggests enhanced carrier mobility, which is crucial for electronic and optoelectronic applications.

Compared to LiSbF3, LiSbCl3 has slightly wider density of states peaks, indicating more spread-out electron states. This difference might affect their electrical conductivities and transport abilities. In both materials, antimony’s 5p states play a major role in both the valence and conduction bands, emphasizing the crucial role of antimony in their electronic characteristics. The strong mixing with halide p-orbitals makes them structurally stable and improves their conductivity.

The confirmed metallic nature of these compounds suggests promising practical applications. Their high electrical conductivity makes them suitable for use in electronic devices such as interconnects, transparent conductors, and high-frequency electronic components. Furthermore, the metallicity and strong electronic interactions could be leveraged for catalytic applications, particularly in electrocatalysis and photocatalysis, where efficient charge transfer is essential. These findings open new pathways for utilizing LiSbX3 (X = Cl, F) in advanced electronic and catalytic applications, broadening their potential impact in energy and material science research.

Optical properties

Real part of dielectric function

The ability of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) to store energy under an electric field is revealed by the real part of their dielectric function (Ɛ1) shown in Fig. 5a. LiSbCl3 has a high dielectric constant of 11.25 at low energies (0.10 eV), indicating a strong polarization response. As the energy increases, the dielectric constant decreases to 3.21 at 3.74 eV and becomes negative ( − 1.32) at 13.58 eV, signaling a transition to metallic behavior. LiSbF3 has a lower dielectric constant, reaching a peak of 2.99 at 4.48 eV and becoming slightly negative ( − 0.12) at 13.54 eV. Despite their differences, both materials hold potential for use in photonic and electro-optical applications, especially in devices that require frequency selectivity.

LiSbCl3's increased ability to polarize and its enhanced interaction with electrical fields makes it an ideal candidate for energy storage devices like supercapacitors with high capacitance and more effective dielectric components.

Imaginary part of dielectric function

The optical absorption properties of LiSbCl3 and LiSbF3 can be inferred from the imaginary part of their dielectric functions (Ɛ2) in Fig. 5b, which reflect electronic transitions between energy bands. LiSbCl3 has a notable peak at 0.47 eV, suggesting significant photon absorption in the low-energy range. This is supported by additional peaks at 10.52 eV and 12.28 eV, indicating absorption at higher energies. LiSbF3, on the other hand, shows a primary peak at 0.25 eV, with subsequent decreases at 6.04 eV and 8.83 eV, indicating a different absorption pattern compared to LiSbCl3.

These materials’ absorption peaks align with electron energy level changes, suggesting their usefulness in UV–visible light detectors and energy absorption.

The high dielectric constant of LiSbCl₃, particularly its value of 11.25 at low energies, suggests a strong polarization capability, making it highly attractive for advanced capacitor and photonic device designs. In capacitor applications, this large dielectric constant can lead to enhanced energy storage capacity, improved charge retention, and higher capacitance density, which are critical for developing miniaturized, high-performance energy storage systems such as supercapacitors and embedded capacitors in integrated circuits. Furthermore, in photonic devices, the strong dielectric response enables better control of light-matter interactions, which is essential for designing optical modulators, waveguides, and tunable photonic crystals. The ability of LiSbCl₃ to exhibit a transition to metallic behavior at higher photon energies also opens possibilities for dynamic, frequency-dependent applications, where devices can switch between insulating and conducting states depending on the operating frequency. Thus, by carefully engineering device architectures around its dielectric and optical properties, LiSbCl₃ could be exploited to develop next-generation capacitive energy storage elements and highly responsive photonic components.

Optical conductivity

The optical conductivity (σ(ω)) of LiSbCl3 reveals insights into its band structure and charge carrier behavior. At 10.54 eV, it reaches a peak conductivity of 4684 Ω −1 cm−1, indicating the excitation of charge carriers across energy bands. However, at 12.50 eV, the conductivity falls to 4449 Ω−1 cm−1, and experiences a further drop to 1244 Ω−1 cm−1 at 7.25 eV shown in Fig. 6a. Unlike LiSbCl3, LiSbF3 exhibits a notable peak conductivity of 1579 Ω−1 cm−1 at 13.44 eV shown in Fig. 6a. However, at lower energies of 6.00 eV and 8.96 eV, its conductivity drops. This difference suggests moderate photon-induced charge movement. Due to their high conductivity within certain energy ranges, these materials have the potential for use in optoelectronic devices like UV sensors and high-frequency electronics.

Optical absorption

The absorption coefficient (α(ω)) measures how well materials block light at different energies. This information is important for understanding their electronic properties and the energy required for electrons to move from one energy level to another. LiSbCl3 can strongly absorb light at higher energies (12.80 eV), which corresponds to interactions with high-energy photons. This suggests that it could undergo transitions to empty states in the conduction band. However, it absorbs less light at lower energies (10.74 eV and 7.38 eV), indicating limited absorption in the visible and near-infrared regions shown in Fig. 6b. LiSbF3, on the other hand, has its highest absorption (82 cm−1) at 13.52 eV. At lower energies (10 eV and 6.11 eV), it absorbs less light (55 cm−1 and 45 cm−1, respectively) shown in Fig. 6b. These characteristics make both materials suitable for coatings that block ultraviolet light.

Refractive index

Investigating the refractive index n(ω) of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) to understand their optical qualities shown in Fig. 7. LiSbCl3 has a peak refractive index of 3.37 at 0.12 eV, which gradually decreases to 1.27 at 12.16 eV. LiSbF3, on the other hand, exhibits a maximum refractive index of 3.15 at 0.12 eV, declining to 1.06 at 12.08 eV. These properties indicate its potential for applications such as optical fibers and anti-reflective coatings.

LiSbCl3's higher refractive index allows it to manipulate light effectively in lenses, optical fibers, and waveguides. This is due to its electronic structure and ability to interact with electric fields. On the other hand, LiSbF3's lower refractive index makes it ideal for optical systems requiring minimal light distortion, like transparent displays and laser protection systems.

Reflectivity

The light-reflecting properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) used to see how well they work as optical coatings and mirrors shown in Fig. 8. LiSbCl3 reflects a lot of light at high-energy ultraviolet wavelengths (0.56 reflectivity at 13.60 eV), making it a good choice for these applications. LiSbF3, on the other hand, has a lower reflectivity (0.28 at 0.11 eV) and doesn’t reflect as much light at higher energies.

LiSbCl3 has high reflectivity, making it suitable for coatings in UV and visible light. Its strong light interaction is due to its electronic structure and ability to modify light’s polarization. LiSbF3 has low reflectivity, making it ideal for anti-reflective coatings. Its low reflectivity helps reduce light loss, improving light transmission in devices like solar panels and optical equipment.

Extinction coefficient

The light-blocking properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) were measured using the extinction coefficient (κ(ω)), a value that indicates how much light is absorbed and scattered by the material displayed in Fig. 8. LiSbCl3 has a higher extinction coefficient than LiSbF3, meaning it blocks more light. It has two main peaks: one at 0.56 eV, where it blocks up to 1.75 times light, and another at 12.78 eV, where it blocks up to 1.35 times more light. This means it effectively absorbs and blocks light in the ultraviolet and visible ranges. LiSbF3 has a lower extinction coefficient, with peaks at 0.33 eV (1.39 times) and 13.54 eV (0.60 times). While it does not block as much light as LiSbCl3, it still shows promising absorption capabilities. Both LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) are suitable for applications where UV-blocking films or optoelectronic absorbers are required.

Energy loss function

The energy loss function (ELF) measures the energy lost by fast-moving electrons in a material and is linked to plasmon resonance, where materials’ surfaces exhibit collective electron oscillations. We calculated the ELF for LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) to study their energy loss properties. LiSbCl3 has ELF peaks at 0.70 and 1.09 eV, and a minimum at 7.62 eV. LiSbF3, on the other hand, has stronger plasmonic activity, with peaks at 1.60, 1.26, and 0.74 eV shown in Fig. 9. The higher ELF of LiSbF3, particularly at high energies, makes it promising for plasmonic applications like surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) and energy harvesting.

In contrast, LiSbCl3 shows a less concentrated electron localization, as indicated by its lower electron localization function (ELF) peak of 0.50 at 13.40 eV. This signifies a greater spread of electrons, which promotes plasmonic activity. As a result, LiSbCl3 is well-suited for various advanced plasmonic applications, such as guiding light waves, fabricating photonic devices, and developing biosensors.

The characteristics of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) optically make it suitable for optoelectronic applications. The dielectric constants represented high values, especially in the case of LiSbCl3, indicating very strong polarization effects, which in turn affect excitonic binding energy. Further understanding of excitonic effects may thus provide insight into the interaction of carriers within these materials.

These values of high optical conductivity indicate that the compounds can be used for transparent conducting films, photodetectors, and photovoltaic cells. Their narrow bands suggest that LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) should be well-suited to make UV-sensitive photodetectors and protect coatings; strong absorption in the ultraviolet range suggests the same. The same refractive index and reflectivity values in these materials promise good antireflective coatings in solar energy applications.

The strong UV absorption observed in LiSbX₃ (X = Cl, F) primarily originates from their electronic band structures, where significant interband transitions occur at higher energies. In both compounds, the presence of antimony (Sb) with its highly polarizable p-orbitals, combined with the strong electronegativity of the halogens (Cl and F), leads to enhanced electronic transitions when interacting with UV photons. These transitions are evident from the peaks in the imaginary part of the dielectric function and the absorption coefficient at energies above 10 eV, indicating efficient photon absorption in the ultraviolet region. Traditional halide perovskites typically absorb strongly in the visible region (1.5–3.5 eV), while LiSbX₃ materials extend well into the deep-UV range (> 10 eV). This behavior suggests that LiSbX₃ materials could offer unique advantages for UV-blocking coatings, UV photodetectors, and plasmonic applications where deep-UV sensitivity is critical, distinguishing them from conventional halide perovskites more suited for visible-light optoelectronics. Our findings are consistent with previously studied perovskites materials64,65,66,67,68.

Elastic properties

The elastic properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) in their cubic P phase provide essential information about their mechanical behavior under stress and strain. These properties (shown in Table 2), including the stiffness coefficients C11, C12, and C44, as well as derived parameters such as bulk modulus (B), shear modulus (G), Poisson’s ratio (ʋ), young modulus (E).

\({\text{P}}_{\text{X}}^{\text{Cauchy}}\), and anisotropy index (A), are critical for assessing structural stability, bonding characteristics, and potential applications in advanced materials.

The elastic properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) provide a comprehensive understanding of their mechanical behavior. LiSbCl3 exhibits superior mechanical stability, with a higher uniaxial compressive resistance (C11 = 62.15 GPa) compared to LiSbF3 (C11 = 41.63 GPa). In contrast, LiSbF3 demonstrates a greater resistance to uniform compression, as indicated by its higher bulk modulus (B = 47.90 GPa) than LiSbCl3 (B = 25.77 GPa). However, the significantly lower shear modulus (G) and B/G ratio of 2.28 for LiSbF3 indicate its brittle nature, while LiSbCl3, with a B/G ratio of 10.05, is ductile.

The Poisson’s ratio (ν) values further support these findings, with LiSbCl3 (ν = 0.27) exhibiting slightly lower ductility compared to LiSbF3 (ν = 0.30). The Cauchy pressure (C12−C44) shows distinct bonding characteristics, where LiSbCl3 has a positive Cauchy pressure (3.2 GPa), indicating dominant ionic bonding, while LiSbF3 exhibits a negative Cauchy pressure ( − 15.77 GPa), confirming metallic bonding and structural instability. Additionally, the anisotropy index (A) highlights major differences in elastic behavior; LiSbCl3 has a near-isotropic structure (A = 0.16), whereas LiSbF3 has a significantly higher anisotropy index (A = 1.53), reinforcing its mechanical instability.

These findings confirm that LiSbCl3 is mechanically stable and ductile, while LiSbF3 is mechanically unstable and prone to failure under stress. Possible routes to enhancing mechanical stability might involve strain engineering, doping with other species such as Ge or Bi, or applying an external pressure. Other halide perovskites have been stabilized through these methods and documented in the literature. The goal would be to make LiSbF3 a more viable option for energy and optoelectronic applications through just such modifications.

3D and 2D visualizations showcase the mechanical properties of LiSbCl3, focusing on Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio displayed in Fig. 10. The 3D Young’s modulus plot reveals a highly anisotropic behavior, showcasing regions of varying stiffness extending along specific crystallographic directions. Meanwhile, the 2D Young’s modulus plot in the xy-plane exhibits a fourfold symmetry (Fig. 10b), highlighting directional dependence and significant elastic anisotropy within the plane.

The 3D plot shows a flower-like structure, indicating variations in shear resistance depending on the direction. The 2D projection reveals a four-fold symmetric lobed structure, highlighting the compound’s anisotropic shear behavior. The 3D plot shows a delicate petal-like shape, indicating strong anisotropy in how the material expands or contracts in response to forces applied in different directions. The 2D projection shows a four-lobed pattern in the xy-plane, indicating varying Poisson’s ratios depending on the direction of loading.

The mechanical properties of LiSbF3 also reveal anisotropy but with distinct characteristics compared to LiSbCl3 as shown in Fig. 11. The 3D plot of the Young’s modulus (Fig. 11a) shows a more uniform, cubic-like shape, suggesting less pronounced anisotropy in stiffness. Its 2D projection in the xy-plane (Fig. 11b) is nearly square-shaped, further emphasizing moderate elastic anisotropy in this compound.

Unlike LiSbCl3, the mechanical properties of LiSbF3 exhibit anisotropy with different characteristics. The Young’s modulus (Fig. 11a) shows a more regular, cube-like shape, suggesting weaker anisotropy in stiffness. Its 2D projection (Fig. 11b) is nearly square, emphasizing moderate elastic anisotropy. The shear modulus (Fig. 11c, d) has a less complex, rounded shape (3D) and smoother variations (2D), indicating a more uniform distribution of shear resistance compared to LiSbCl3.

The Poisson’s ratio of LiSbF3 displays subtle differences depending on the direction of applied force. The 3D representation shows a flower-like shape that is less pronounced compared to the ratio for LiSbCl3. The 2D representation reveals a lobe-shaped structure, indicating a weaker variation in the lateral strain response in different directions.

Phonon dispersion analysis

Phonon dispersion relations of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F), as shown in the Fig. 12, reveal much about their lattice dynamics, vibrational properties, and structural stability. These calculations of phonon band structures have been done along the high-symmetry directions in the Brillouin zone, expressing the R, Γ, X, and M points. The total absence of any imaginary phonon frequencies throughout the Brillouin zone indicates strong evidence of dynamical stability in both materials, against the view that a negative frequency could signal structural problems or possible phase changes.

In LiSbF3, phonon frequencies are seen up to about 9 THz, which indicates relatively strong interatomic bonding, especially in view of the presence of light fluorine atoms, contributing to higher vibrational frequencies. The dispersion curve shows a clear distinction between the lower frequency acoustic branches and the higher frequency optical branches, indicating strong mass contrast between lithium, antimony, and fluorine atoms. There is some mixing among the optical branches, indicating some interaction of different vibrational modes in the crystal lattice.

In the same way, the phonon dispersion of LiSbCl3 follows the same trend except for slightly lower maximum phonon frequencies as compared to those of LiSbF3, which can be ascribed to the larger atomic mass of chlorine relative to fluorine. The heavier Cl atoms lower the vibrational frequencies due to lowered bond stiffness and lowered force constants. The acoustic branches in both compounds were monotonic and continuous without the presence of soft phonon modes further confirming the mechanical stability of the structures.

The unique characteristics of phonon dispersion in these materials suggest possible differences in their thermal transport behavior. Because phonon propagation is usually fast in a lighter atom, LiSbF3 is likely to possess higher lattice thermal conduction than LiSbCl3, which, on the other hand, has lower phonon frequency, thereby enhancing phonon scattering and reducing thermal conductivity and making it a better candidate for thermoelectric applications.

In general, the phonon dispersion study of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) offers valuable insights into their vibrational properties, stability, and functional applications. These will provide a strong basis for further study in theory and experimentation on thermoelectric, optoelectronic, and materials science applications in which lattice dynamics are crucial for material performance.

Conclusion

-

Using computer simulations, this research examines the structure, electronic behavior, optical, elastic, and phonon properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F). Goldschmidt tolerance factors and bulk modulus calculations reveal that both have high-symmetry cubic crystal structures.

-

Studies of the electronic properties reveal that LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) are metals. Their exceptional electrical conductivity stems from the powerful overlap between antimony’s 5p and halogen p orbitals, allowing electrons to move freely. Despite their shared metallic nature, differences in their density of states indicate variations in how they conduct electricity and transport charges.

-

Optical properties shows that LiSbCl3 has high dielectric constants, reflectivity, and strong light absorption making it ideal for applications where high polarization response, light blockage, and electromagnetic interference shielding are crucial. While, LiSbF3's lower dielectric values, extinction coefficients, and refractive index make it suitable for optical systems where transparency, low reflectivity, and minimal light distortion are required.

-

LiSbCl3 has stable mechanical properties that make it a good choice for situations where moderate stiffness and durability are needed. However, LiSbF3 is not stable mechanically. Its negative G and G/B values indicate this. This makes it not suitable for structural or mechanical uses.

-

LiSbX3 (X = Cl or F) show promise as substitutes for lead in solar energy and electronics. They have remarkable properties that suit them for specific purposes, including coatings with excellent conductivity, UV-blocking materials, and energy-saving devices. Further research should investigate their thermal and mechanical characteristics to enhance their range of applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pancini, L. et al. A fluorescent sensor to detect lead leakage from perovskite solar cells. Mater. Adv. 4(11), 2410–2417 (2023).

Hamideddine, I., Zitouni, H., Tahiri, N., El Bounagui, O. & Ez-Zahraouy, H. A DFT study of the electronic structure, optical, and thermoelectric properties of halide perovskite KGeI3–xBrx materials: Photovoltaic applications. Appl. Phys. A 127, 1–7 (2021).

Geleta, T. A. & Imae, T. Nanocomposite photoanodes consisting of p-NiO/n-ZnO heterojunction and carbon quantum dot additive for dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4(1), 236–249 (2021).

Perera, F. P. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ. Health Perspect. 125(2), 141–148 (2017).

Naseer, M. et al. Engineering of metal oxide integrated metal organic frameworks (MO@MOF) composites for energy and environment sector. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 313, 117909 (2025).

Ishfaq, M. et al. First principles investigation of structural, electronic, optical, transport properties of double perovskites X2TaTbO6 (X= Ca, Sr, Ba) for optoelectronic and energy harvesting applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 197, 112432 (2025).

Messekine, S. et al. A comprehensive study of mechanical, optoelectronic, and magnetic insights into terbium orthovanadate TbVO4 via first-principles DFT approach. J. Solid State Chem. 310, 123007 (2022).

Zanib, M. et al. A DFT investigation of mechanical, optical and thermoelectric properties of double perovskites K2AgAsX6 (X= Cl, Br) halides. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 295, 116604 (2023).

Geleta, T. A. & Imae, T. Influence of additives on zinc oxide-based dye sensitized solar cells. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 93(4), 611–620 (2020).

Kong, L. et al. Enhanced red luminescence in CaAl12O19: Mn4+ via doping Ga3+ for plant growth lighting. Dalt. Trans. 49(6), 1947–1954 (2020).

Hamideddine, I., Jebari, H. & Ez-Zahraouy, H. Insights into optoelectronic behaviors of novel double halide perovskites Cs2KInX6 (X= Br, Cl, I) for energy harvesting: First principal calculation. Phys. B Condens. Matter 677, 415699 (2024).

Apurba, I. K. G. G. et al. Strain effect on the physical properties of novel Mg3NI3 perovskite material: First principle DFT analysis. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 197, 112435 (2025).

Meinardi, F. et al. Doped halide perovskite nanocrystals for reabsorption-free luminescent solar concentrators. ACS energy Lett. 2(10), 2368–2377 (2017).

Ke, W., Spanopoulos, I., Stoumpos, C. C. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Myths and reality of HPbI3 in halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 4785 (2018).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Enhanced luminescence and stability of cesium lead halide perovskite CsPbX3 nanocrystals by Cu2+-assisted anion exchange reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 123(4), 2353–2360 (2019).

Khan, N. U. et al. Investigation of structural, opto-electronic and thermoelectric properties of titanium based chloro-perovskites XTiCl3 (X = Rb, Cs): A first-principles calculations. RSC Adv. 13(9), 6199–6209. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ra00200d (2023).

Ullah, S. et al. Density functional quantum computations to investigate the physical prospects of lead-free chloro-perovskites QAgCl3 (Q= K, Rb) for optoelectronic applications. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 25(3), 1–13 (2024).

Abraham, J. A. et al. A comprehensive DFT analysis on structural, electronic, optical, thermoelectric, SLME properties of new double perovskite oxide Pb2ScBiO6. Chem. Phys. Lett. 806, 139987 (2022).

Behera, D. & Mukherjee, S. K. Optoelectronics and transport phenomena in Rb2InBiX6 (X= Cl, Br) compounds for renewable energy applications: A DFT insight. Chemistry (Easton) 4(3), 1044–1059 (2022).

Behera, D. et al. First-principle investigations on optoelectronics and thermoelectric properties of lead-free Rb2InSbX6 (X= Cl, Br) double perovskites: For renewable energy applications. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(6), 520 (2023).

Behera, D. & Mukherjee, S. K. First-principles calculations to investigate structural, optoelectronics and thermoelectric properties of lead free Cs2GeSnX6 (X= Cl, Br). Mater. Sci. Eng. B 292, 116421 (2023).

Zheng, J., Huan, C. H. A., Wee, A. T. S. & Kuok, M. H. Electronic properties of CsSnBr3: Studies by experiment and theory. Surf. Interf. Anal. An Int. J. devoted to Dev. Appl. Tech. Anal. Surf. Interf. Thin Film 28(1), 81–83 (1999).

Teixeira, C. O., Castro, D., Andrade, L. & Mendes, A. Selection of the ultimate perovskite solar cell materials and fabrication processes towards its industrialization: A review. Energy Sci. Eng. 10(4), 1478–1525 (2022).

Selmani, Y., Labrim, H. & Bahmad, L. Structural, optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of the new perovskites LiMCl3 (M= Pb or Sn): A DFT study. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(9), 1416 (2024).

Khan, I. et al. First principle study of structural and optoelectronic properties of ZnLiX3 (X= Cl or F) perovskites. Res. Phys. 66, 108019 (2024).

Hao, F., Stoumpos, C. C., Cao, D. H., Chang, R. P. H. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Lead-free solid-state organic–inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 8(6), 489–494 (2014).

Jeong, M. J., Jeon, S. W., Kim, S. Y. & Noh, J. H. High fill factor CsPbI2Br perovskite solar cells via crystallization management. Adv. Energy Mater. 13(23), 2300698 (2023).

Ullah, A. et al. Unlocking the physical properties of RbXBr3 (X= Ba, Be) halide perovskites for potential applications: DFT study. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 173, 113879 (2025).

Guji, K. W., Geleta, T. A., Bouri, N. & Rivera, V. J. R. First principles study on the structural stability, mechanical stability and optoelectronic properties of alkali-based single halide perovskite compounds XMgI3 (X= Li/Na): DFT insight. Nanoscale Adv. 6(17), 4479–4491 (2024).

Moghe, D. et al. All vapor-deposited lead-free doped CsSnBr3 planar solar cells. Nano Energy 28, 469–474 (2016).

He, S., Guo, S., Cao, F., Yao, C. & Wang, G. A sodium bismuth titanate-based material with both high depolarization temperature and large pyroelectric response. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0100540 (2022).

Linh, N. H., Tuan, N. H., Dung, D. D., Bao, P. Q. & Cong, B. T. Alkali metal-substituted bismuth-based perovskite compounds: A DFT study. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 4(3), 492–498 (2019).

Zhao, C., Cheung, C. F. & Xu, P. High-efficiency sub-microscale uncertainty measurement method using pattern recognition. ISA Trans. 101, 503–514 (2020).

Jameel, M. H. et al. A comparative DFT study of electronic and optical properties of Pb/Cd-doped LaVO4 and Pb/Cd-LuVO4 for electronic device applications. Comput. Condens. Matter 34, e00773 (2023).

Wickleder, C. Spectroscopic properties of SrZnCl4: M2+ and BaZnCl4: M2+ (M= Eu, Sm, Tm). J. Alloys Compd. 300, 193–198 (2000).

Alqorashi, A. K. First principle insights on optoelectronic, mechanical, and thermoelectric properties of double perovskites Li2ScAu(Br/I)6 for energy harvesting applications. Phys. Scr. 99(8), 85982 (2024).

Mustafa, G. M. et al. Optoelectronic and transport properties of lead-free double perovskites Li2AgTlX6 (X= Cl, Br): A DFT study. Phys. B Condens. Matter 680, 415831 (2024).

Alburaih, H. A. et al. Opto-electronic and thermoelectric properties of double perovskites Li2CuGaX6 (X= Cl, Br, I) for energy conversion applications: DFT calculations. J. Mater. Res. 39(8), 1207–1216 (2024).

Nazir, S. et al. Study of Mechanical, Optoelectronic, and thermoelectric aspects of lithium-based double perovskites Li2AgSbX6 (X= Cl, Br, I) for energy harvesting applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 309, 117651 (2024).

Younas, B. et al. Mechanical, optoelectronic, and thermoelectric performance of Li-based double perovskites Li2CuSbZ6 (Z= Cl, Br, I) first-principles calculations. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-024-03146-9 (2024).

ur Rehman, Z. et al. A DFT study of structural, electronic, mechanical, phonon, thermodynamic, and H2 storage properties of lead-free perovskite hydride MgXH3(X= Cr, Fe, Mn). J. Phys. Chem. Solids 186, 111801 (2024).

Hossain, M. K. et al. Deep insights into the coupled optoelectronic and photovoltaic analysis of lead-free CsSnI3 perovskite-based solar cell using DFT calculations and SCAPS-1D simulations. ACS Omega 8(25), 22466–22485 (2023).

Liu, S., Qin, B., Wang, D. & Zhao, L. Investigations on the thermoelectric transport properties in the hole-doped La2CuO4. Zeitschrift für Anorg. und Allg. Chemie 648(15), e202200036 (2022).

Liu, D., Peng, H., Li, Q. & Sa, R. A DFT study of the stability and optoelectronic properties of all-inorganic lead-free halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 161, 110413 (2022).

Jehan, A. et al. Investigating the structural, elastic, and optoelectronic properties of LiXF3(X= Cd, Hg) using the DFT approach for high-energy applications. Opt. Quant. Electr. 56(2), 169 (2024).

Miran, H. A. & Jaf, Z. N. A systematic DFT study on the optoelectronic and elastic characteristics of H-induced KMnF3 perovskite. Brazilian J. Phys. 55(2), 1–14 (2025).

Apurba, I. K. G. G. et al. Tuning the optoelectronic, mechanical, and thermodynamic properties of lead-free Mg3NF3 perovskite with tunable strain through DFT study. Phys. B Condens. Matter 699, 416879 (2025).

Khan, N. U. et al. Investigation of structural, opto-electronic and thermoelectric properties of titanium based chloro-perovskites XTiCl3 (X= Rb, Cs): a first-principles calculations. RSC Adv. 13(9), 6199–6209 (2023).

Ayyaz, A. et al. Exploring energy harvesting potential of lithium-based halide perovskites Li2CuSbZ6 (Z= Cl, Br): First principles approach. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 185, 108968 (2025).

Sohail, M. et al. First-principal investigations of electronic, structural, elastic and optical properties of the fluoroperovskite TlLF3 (L= Ca, Cd) compounds for optoelectronic applications. RSC Adv. 12(12), 7002–7008 (2022).

Rahman, N. et al. First principle study of structural, electronic, optical and mechanical properties of cubic fluoro-perovskites:(CdXF3, X= Y, Bi). Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136(3), 1–11 (2021).

Hosen, A. Investigating the effects of hydrostatic pressure on the physical properties of cubic Sr3BCl3 (B= As, Sb) for improved optoelectronic applications: A DFT study. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35855 (2024).

Riaz, M., Ali, S. D., Sadiq, M., Ali, M. & Ali, S. M. Exploring the potential of inorganic cubic halide perovskites RbSrM3 (M= Cl, Br) for advanced optoelectronic applications: A DFT study. Chem. Phys. 577, 112141 (2024).

Rashid, M. A., Saiduzzaman, M., Biswas, A. & Hossain, K. M. First-principles calculations to explore the metallic behavior of semiconducting lead-free halide perovskites RbSnX3 (X= Cl, Br) under pressure. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137(6), 649 (2022).

P. Blaha, K. Schwarz, G. K. H. Madsen, D. Kvasnicka, & J. Luitz, “wien2k,” An Augment. Pl. wave+ local orbitals Progr. Calc. Cryst. Prop., vol. 60, no. 1, (2001).

Camargo-Martínez, J. A. & Baquero, R. Performance of the modified Becke-Johnson potential for semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B—Conden. Matter Mater. Phys. 86(19), 195106 (2012).

Koller, D., Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Improving the modified Becke-Johnson exchange potential. Phys. Rev. B 85(15), 155109 (2012).

Ullah, A. et al. DFT study of structural, elastic and optoelectronic properties of binary X2Se (X= Cd, Zn) chalcogenides. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 174(Part1), 113985 (2025).

Murnaghan, F. D. The compressibility of media under extreme pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 30(9), 244 (1944).

Chaba Mouna, S. et al. Structural, electronic, and optical characteristics of BaXCl3 (X = Li, Na) perovskites. Mater. Sci. Eng. B https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2024.117578 (2024).

Rahman, N. et al. Appealing perspectives of the structural, electronic, elastic and optical properties of LiRCl3 (R= Be and Mg) halide perovskites: a DFT study. RSC Adv. 13(27), 18934–18945 (2023).

Husain, M. et al. Examining computationally the structural, elastic, optical, and electronic properties of CaQCl3 (Q= Li and K) chloroperovskites using DFT framework. RSC Adv. 12(50), 32338–32349 (2022).

Bartel, C. J. et al. New tolerance factor to predict the stability of perovskite oxides and halides. Sci. Adv. 5(2), 10693 (2019).

Priyambada, A. & Parida, P. Effect of Hubbard U on the electronic and magnetic properties of Ca2VMoO6 double perovskite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 570, 170478 (2023).

Manzoor, M. et al. First-principles calculations to investigate structural, dynamical, thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of CdYF3 perovskite. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1217, 113928 (2022).

Shahzad, M. K. et al. Investigation of structural, electronic, mechanical, & optical characteristics of Ra based-cubic hydrides RbRaX3 (X= F and cl) perovskite materials for solar cell applications: First principle study. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18407 (2023).

Husain, M. et al. DFT-based computational investigations of structural, mechanical, optoelectronics, and thermoelectric properties of InXF3 (X= Be and Sr) ternary fluoroperovskites compounds. Phys. Scr. 98(7), 75905 (2023).

Behera, D. et al. Studies on optoelectronic and transport properties of XSnBr3 (X= Rb/Cs): A DFT insight. Crystals 13(10), 1437 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Izzat Khan, Amir Ullah, Wafa Mohammed Almalki, Nasir Rahman, Mudasser Husain, Mohamed Hussien wrote the manuscript. Vineet Tirth, Khamael M Abualnaja, Mohammad Sohail prepared figures. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, I., Ullah, A., Almalki, W.M. et al. Probing the physical properties of LiSbX3 (X = Cl, F) halides perovskites for optoelectronic applications. Sci Rep 15, 18837 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03320-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03320-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Tuning optoelectronic properties in BaNaH3X (X = Ni, Pd, Pt) perovskite hydrides: a DFT-based analysis

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2026)

-

Unveiling the Electronic, Optical, and Mechanical Properties of Lithium-Based Perovskites for Next-Generation Solar Cells

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)