Abstract

The development of dielectric ceramics for energy storage applications requires suppression of interfacial polarization (IFPs) and elevation of grain resistance to obtain high energy storage density and foster breakdown strength. The present study illustrates a strategy for reducing IFPs via increasing configurational entropy (ΔS) and optical band-gap (Eg) engineering of (Ba0.95−xNdxBi0.05)(Ti0.9Zr0.1)O3 (0.0 < Nd < 0.1) (abbreviated BBZTNx) ceramics. The disrupted ferroelectricity long-range order of BBZT can be fostered by increasing ΔS via Nd addition into the A-site of the lattice. Increasing ΔS from 0.5R to 0.9R can induce a stable perovskite structure and decrease the polarity of material at the highest content of Nd ions. The optical properties revealed that Eg increased from 3.2 to 3.35 eV as Nd increased from 0.0 to 0.1. The augmented difference between ionic radius at A-sites as Nd increases leads to a reduction in the grain size and an increase in the resistance of grain (Rg). These cascade influences result in the suppression of IFPs and bolster the breakdown strength (Eb). The Eb increased from 200 kV/cm to 300 kV/cm as Nd increased from 0.0 to 0.1, which is about five times higher than pure BT. The best energy storage properties can be achieved at 0.05 of Nd with 2.75 J/cm3 of Wrec and 93% of ƞ at moderate E = 200 kV/cm. The present study illustrates a strategy for comprehensive suppression of IFPs and enhancement of Eb of perovskite structure ceramics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dielectric ceramic capacitors are widely used in electronic integration circuits due to ultra-high power density, ultra-fast charge/discharge rates, and excellent thermal and cycle stability1,2. Although lead-free (BaTiO3)-based ceramics have been extensively used in the above applications, they are facing restrictions from some booming high-temperature applications such as electric vehicles, deep-well gas exploration, and aerospace power electronics, which require capacitors in operation temperatures exceeding 150 °C3,4,5. One of the key parameters that restricts BT-based capacitors from working at high temperatures is the low phase transition temperature (~ 130 °C), where the dielectric properties and capacitance change dramatically against the applied temperature6. One possible solution for this issue is adopting relaxor ceramics, which possess a temperature-insensitive dielectric constant over a wide temperature range due to their diffuse phase transition of particular the typical relaxor materials exhibit a slim hysteresis loop, “electric field dependence polarization (P-E loops) along with the highly dynamic polar nanoregions (PNRs), resulting in simultaneously high recoverable energy density (Wrec) and high energy storage efficiency (η)7,8,9. The relaxor characteristics in BT ceramics can be achieved by replacing or substituting Ba2+, Ti4+, or both with monovalent cations, where the ferroelectric to relaxor phase transition can occur above 0.3 for doping by hetero-valent cations. In the heterovalent class, the activation energies for PNR coupling are much higher than those of classical relaxors so, the relaxor phase can be achieved at lower contents of doping, such as Sc3+, Bi3+, La3+, Nd3+, and so on10,11,12,13,14,15. These kinds of materials are attractive for energy storage applications due to preventing long-range dipoles under high applied fields, leading to a field along with delayed polarization saturation16. For enhancement of the energy storage performance of BT ceramics, a number of strategies have been used by researchers, such as reducing the grain size, domain engineering effect, and elevating the optical band gap17,18,19,20. Recently, high entropy have attracted great attention to boost and augment the energy storage capacity of oxide ceramics. The configurational entropy (ΔS) of perovskite ceramics can be calculated by the following equation:

Where xa, xb, and xc are the mole fractions of cations presented at the A, B, and O sites, while R is the universal gas constant. Materials with ΔSconfig higher than 1.5R are defined as high-entropy materials; materials with entropy lower than R can be classified as low-entropy. High-entropy design has been proven effective for improving the energy storage performance of capacitors21. Recent studies reported that the improvement of entropy for perovskite ceramics can induce ferroelectric-relaxor crossover and form dynamic (PNRs). This strategy can enhance the random field and suppress residual polarization (Pr)22. While the increasing entropy led to an increase in the volume fraction of a cubic phase, then decreasing of the saturation polarization (Pmax). Recently the high-entropy strategy has being proved to be a promising method to boost the dielectric breakdown strength via increase in atomic disorder. The atomic disorder in oxide systems induced induces notable lattice distortion, impedes element diffusion, and triggers a synergistic cocktail effect from multi-component properties. On the other hand, the entropy strategy provides a quantitative measure to assess the heterogeneity of local components, thereby facilitating the optimization of breakdown strength through the manipulation of relaxation characteristics in ferroelectric ceramics. The Eb of perovskite systems can be enhanced by increasing the number of elements randomly distributed on the same lattice site resulting in highly relaxor degree.

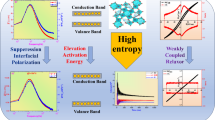

Therefore, the energy storage performance of oxide ceramics can be enhanced by boosting dielectric breakdown strength (Eb)23. The enhancement of Eb can be achieved via suppression of interfacial polarization strategy, which considers a powerful method for obtaining ultra-high Eb. The interfacial polarization can be caused by the difference between the resistance of grains (Rg) and the resistance of grain boundaries (Rgb). The Rgb value is much larger than Rg therefore, the enhancement of resistance of grains is highly needed for pinching the interfacial polarization, then enhanced Eb24. The increasing of IFPs can lead to generate non-uniform distribution of electric field resulting in electrical spark and restricting high Eb. Therefore, the suppression of interfacial polarization is a focus in the development of superior energy storage performance. As is well known, the resistance of grain is acceptable to show a resistance much lower than the resistance of grain boundary. This provides a heuristic hint to reduce the IFPs via increasing grain resistance. This can be achieved by intentionally compositing highly insulative components with wide band-gaps during the design process of perovskite structure. Changyuan Wang. et al. reported that the almost overlapped imaginary part of impedance peak (Zʹʹ) and imaginary component of modulus peak (Mʹʹ) indicate that the interfacial polarization tends to disappear, and the electric field is uniformly distributed24. On the other hand, another study reported that the IFPs intensity can be calculated by the difference between grain and grain boundary activation energies (Δϕ)25. Numerous ions with various radii and valence states were introduced in the (K0.2Na0.8)NbO3 matrix to enhance ΔSconfig and form multi-phase nano-clusters. The local stress and electric fields were enhanced due to the high-entropy strategy, resulting in improved Wrec of 10.06 J/cm3 and η of 90.8% in this lead-free bulk ceramic26. In brief, a high-entropy strategy can be used as a guide to develop dielectric materials with ultrahigh comprehensive energy storage properties. Furthermore, the elevation of the band gap is a key parameter for the improvement of the ESPs by increasing the grain resistance. Heightening the band gap means increasing the required energy for transferring the electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, which can restrict the concentration of carriers charge into the conduction band, then reducing the conductivity and enhancing breakdown strength27. Based on the above explanation, several oxides such as Bi2O3, Nd2O3 and ZrO2 were introduced into the matrix of BaTiO3 to breakdown the long-range ferroelectric order, forming polar nano-regions of relaxor phase and increase their dielectric breakdown strength. This will perform via different strategies such as suppression of interfacial polarization, elevation of grain resistance, high optical band-gap and increasing configurational entropy. The addition of rare earth elements with lower ionic radius (Nd3+ = 1.27Ắ) compared to (Ba2+ = 1.61Ắ) is aims to reduce the tolerance factor, enhance the relaxor phase, suppress dielectric loss (tan δ), and increase energy storage efficiency. Our results reveal that the entropy strategy notably depresses the interfacial polarization of BT-based ceramics as shown in Fig. 1. This enhancement culminates in exceptional entropy from ΔS = 0.0 for pure BT to 0.89R of ΔS for BBZTN0.1 sample.

Experimental and measurements

(Ba0.95−xBi0.05Ndx)(Ti0.9Zr0.1)O3 ceramics (x = 0.0, 0.025, 0.050, 0.075, and 0.1) were fabricated using the solid solution technique. High purity of BaCO3, Bi2O3, Nd2O3, TiO2, and ZrO2 was used as starting materials to produce the target ceramics. The powders were mixed using zirconia balls and absolute ethanol to get a homogeneous solution. After mill time was over, the powder was dried, sieved, and calcined at 1100 oC for 2 h. The calcined powder was pressed into a disc with a 10 mm in diameter and 1 mm thickness after mixing with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The pressed samples were sintered in an alumina crucible at 1325 oC as a sintering temperature for 2 h as a dwell time. X-ray diffractometer (Smartlab-3kw, Rigaku Ltd, Japan) was used to show the phase formed and analyze the crystal structure. A scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-6510, JEOL, Japan) was used to examine the surface morphology. The optical properties and reflectance spectra for crushed ceramics were obtained by UV-Vis spectrophotometer (JASCO V-670 UV–Vis spectrophotometer). The electrical measurements were performed using a computerized LCR meter. The ferroelectric properties were measured by Precision Premier II from Radiant Technologies. For measurement breakdown strength, the sample thickness was reduced to 0.2 mm while the diameter of electrode is 2 mm given 0.0314 cm2 of area.

Schematic diagram of suppressing interfacial polarization via high-entropy, grain resistance, and optical band-gap design for superior Eb and ESPs in BBZT ceramics.The schematic diagram was generated using Powerpoint software 2019 available at website “https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/download-office”. Made by Amira A Kamal.

Structure properties

Figure (2-a) displays x-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) for all present ceramics (Ba0.95−xBi0.05Ndx)(Ti0.9Zr0.1)O3 (0.0 < Nd < 0.1) at ambient temperature. The patterns confirm the present pure single-phase perovskite structure, which indicates both Nd, Bi, and Zr ions have successfully diffused into the BT lattice to form the BBZTN homogeneous solid solution. Only the tiny secondary phase has been seen close to 2θ = 28.45o on the sample Nd = 0.075 corresponding to the TiO2 rutile phase. Pure BBZT ceramic shows an orthorhombic phase (O-phase) confirmed by splitting peaks around 2θ = 45o (Fig. (2-b)). The intensity of splitting peaks decreased by increasing the amount of Nd3+, and a completely single peak was detected at the BBZTN0.1 sample. The creep to single peak denotes decreases in the volume fraction of O-phase and increases the crystal lattice symmetry of samples at high Nd-content. To confirm the patterns, tend to a stable perovskite structure by increasing the amount of Nd; the tolerance factor (\(\:\tau\:\)) was calculated using the equation28:

Where \(\:\tau\:\) is the tolerance factor, RA, RB, and RO represent the ionic radius of ions at A, B, and oxygen-sites, respectively. The ionic radii of Ba, Bi, and Nd with CN = 12 are 1.61, 1.45, and 1.27 Ắ, respectively, while the ionic radii of Ti = 0.605 Ắ and Zr = 0.72 Ắ with CN = 6, and the ionic radius of O is 1.44 Ắ29,30. As the ionic radius of Nd3+ is smaller than the ionic radius of Ba2+, the \(\:\tau\:\) value decreased from 1.047 to 1.035, which shifted close to 1.0. This signified that the crystal structure will have more cubic symmetry at high content of Nd, and this is beneficial for increasing breakdown strength (Eb) and later enhanced energy storage performance. The configurational entropy (ΔS) was calculated using Eq. 3, and the results show increasing the ΔS value from 0.5R to 0.9R as Nd-content increased from 0.0 to 0.1. This shows that the enhancement of entropy can induce more stable perovskite structure which can confirmed by creep of \(\:\tau\:\) values towards 124. As is well known, high entropy led to an increase in the volume fraction of the cubic phase, reflecting a decrease in the polarity of materials24. Rietveld refinements of XRD patterns were performed based on the O-phase (space group P2 mm) resulting from BT and the C-phase (space group Pm3 m) resulting from BZT using Full-proof software and the results were displayed in Fig. 3(a-e) with the enlarged peak at 45 of 2-theta to distinguish the splitting and single peak, particularly this angle. The results showed that as entropy increased, the volume fraction of the O-phase decreased while the volume fraction of the C-phase increased, saying the system creeps to high lattice symmetry. The volume fraction of each phase was calculated after achieving good reliability factors of Rwp and Rp < 2%, and the results were displayed in Fig. (3-f). The ratio of the volume fraction of the O-phase to C-phase is close to 1 at Nd = 0.05, which denotes that the coexistence of phases can be achieved at this concentration of Nd. This will reflect a great enhancement of dielectric and ferroelectric properties at this point. The weak polar phase (i.e., high volume fraction of C-phase) is conducive to enhancing Eb by reducing the Pr value, resulting in a conducive environment to enhance comprehensive breakdown strength and ESP31. Figure (4-a) displays the values of (\(\:\tau\:\)) and ΔS as a function of Nd-content. The calculations show that as Nd increased, the \(\:\tau\:\) decreased while ΔS increased, confirming the increase in the lattice crystal symmetry and weak polarity of BBZT ceramics at high Nd. The microstructure of BBZTN sintered polished ceramics, along with the distribution of particle size estimated by ImageJ software, was displayed in Fig. (4. b-f). The image shows uniform fully dense microstructure with very few voids attributed to the volatility of Bi2O3 at high sintering temperatures. The average grain size of BBZT is within the sub-microscale and decreases with increasing entropy. Given their remarkable refractory behavior that, Bi oxide is extensively employed as grain growth inhibitors to mitigate the average grain size32,33. The average grain size clearly observed decreased as Nd-content increased which could be back to (i) lower ionic radius of Nd3+ compared to Ba2+ induced shrinkage of lattice, (ii) the substitution of isovalent Ba2+ by trivalent Nd3+ cations results in a charge misfit, which can be balanced by creating barium vacancies resulting in reducing in grain size as well, (iii) addition Bi2O3 as semiconductor element along with lower melting temperature can be used as sintering aid for reducing sintering temperature which induced inhibition of grain grow. The lattice distortion induced by the elevated configurational entropy can substantially impede atomic diffusion, thereby further diminishing the average grain size (G) can be achieved at high content of Nd addition27. Based on the contraction relation between breakdown strength and grain size \(\:{E}_{b}\alpha\:\frac{1}{G}\), the Eb can be elevated and enhanced by reduction grain size27. On the other hand, the low sintering temperature (1325 oC) results in suppression of the grain growth compared to pure BT (1450 oC)34 of sintering, which denotes that both Bi2O3 and Nd2O3 can be used as a sintering aid as well. The suppression of particle size to submicron scale is beneficial for the suppression of interfacial polarization and enhances the breakdown strength of BBZT-based Nd ceramics.

Dielectric and entropy properties

The dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss (tan δ) of (BBZTNx) (x = 0.0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, and 0.1) sintered ceramics were measured in a wide range of temperature (−75oC to 250oC) using liquid nitrogen to detect the phase transition of each compound. All measurements were performed at four different frequencies (0.5, 1, 10, and 100 kHz) to investigate the evolution of ferroelectric and relaxor behavior, and the results were depicted in Fig. 5(a-e). It is worth noticing that in the absence of Nd ions, the dielectric curve shown presents three distinct phases depending on the applied temperature. From − 75 to −5oC, the material shows a ferroelectric phase, and a ferroelectric to relaxor phase crossover was detected at depolarization temperature (Td). From Td up to 85 oC above RT, the material undergoes the relaxor phase while relaxor to paraelectric phase transition was seen at Tm (the temperature corresponding to maximum permittivity)27. The present ferroelectric phase at low T (−75 to −5oC) could be owing to the formation of O-phase (P2 mm space group) of BBZT, where the domain size is in the microscale with long-range order; however, the present relaxor phase above RT could be attributed to a co-existence phase of tetragonal BT (P4 mm space group) and cubic BZT (Pm3 m space group)34. The dielectric loss showed the lowest value at higher frequencies below Td, while inverse behavior was seen above Td, where higher loss corresponds to higher frequency. This behavior could be owing to presenting the static polar regions effect at low T while the dynamic polar nano-regions are dominated at high T, which results from an oxygen vacancies effect35. While the compositions are based on Nd3+, there is no detection of Td in the measured range of T, showing the material creep to relaxor phase even below RT. The maximum permittivity (εmax) increased as Nd-content increased, and the maximum value (4825, 500 Hz) was achieved at Nd = 0.05 as shown in Fig. 5(f). The increase in dielectric constant as Nd-content increases can be explained as the ionic radius of Nd3+ is smaller than the ionic radius of Ba2+, resulting in contraction of the grain size and volume cell. The largest dielectric constant at 0.05 of Nd addition could be due to the coexistence phases of the C-phase and O-phase at room temperature, which signified enhancing the dielectric constant values more than the other compositions. Meanwhile, the decrease in dielectric constant above 0.05 could be due to the introduction of multi-ions into the lattice positions, viz., A or B-sites can increase the entropy, disrupt the LRO of the ferroelectricity phase, and decrease the polarity. Suppression of dielectric constantly results in enhanced dielectric breakdown strength. The mean ionic radius of ions at the A-site of BBZT is 1.596 Ắ, while the mean ionic radius of ions at the A-sites of BBZTN0.1 is 1.441 Ắ. The augmented difference between ionic radii at the A-sites can lead to an increase in the lattice distortion, consequently affecting polarization and the dielectric constant. Along with the dielectric constant (εr), the dielectric loss was measured at the same parameters of (εr); the tan δ was seen to be high at higher frequencies at (T < 150 oC) and high at low frequencies above 150 oC. This reflects static and dynamic polar nano-regions effects as well36. The addition of Nd3+ to BBZT induces suppressed dielectric loss by reducing interfacial polarization and space charge effect of the dielectric loss, 20 Hz was to be observed suppressed from 0.04 for Nd-free ceramic to 0.005 for BBZTN0.1 ceramics at RT, which is conductive to improving dielectric breakdown strength and enhancing the energy storage properties of BBNZT ceramics. To further investigate the ferroelectric and relaxor degree, the variation of permittivity as a function of T at 1.0 kHz as applied frequency at high T after Tm can be fitted with the modified Curie-Weiss Eq. 537:

Where γ is depicting the diffusion phase transition, C is a constant, ε is the dielectric constant at temperature T, and εm is the largest dielectric constant at Tm. The γ value can reflect the ferroelectric degree. If the value is equal to 1, the material undergoes ideal ferroelectric, while the material can be described as an ideal relaxor state if γ = 2. The fitting results confirm the γ values are found within range (1–2) and indicate the (ε - T) curve can undergo the modified Curie-Weiss law. The diffusion γ value of pure BBZT ceramic is 1.67: meanwhile, it was seen increasing to 1.84 at BBZT-based 0.025 of Nd ions, then decrease to 1.83 at 0.05 of Nd, then again increase and have a maximum value of 1.864 at Nd = 0.1. The increase in γ at 0.1 indicates improvement of the relaxor phase and thermal stability of the material, while the sharp dielectric peak and decreasing γ value at 0.05 could be back to the coexistence of O and C-phases. The values of γ corresponding to Nd content were displayed in Fig. 5(f). The figure also shows the variation of experimental density measured by the Archimedes method of BBZTNx as a function of Nd-content. The values shown in the density increased as Nd content increased, where it rose from 5.06 to 5.44 gm/cm3 when Nd addition increased from 0.0 to 0.1. The increase in density via increasing Nd ions is back to a higher density of Nd2O3 (7.24 gm/cm3) than the density of BaO (5.72 gm/cm3). Furthermore, the relative density (\(\:{\rho\:}_{Relative}=\frac{{\rho\:}_{calculated}}{{\rho\:}_{theoritical}}\) (%)) increased as entropy increased, where it was increased from 95.6–98% when entropy increased from 0.5R to 0.9R. The above results reflect that the rising of ΔSconfig is successful to breaking the LRO ferroelectric, giving enhancement to SRO and PNRs, which is considered good evidence for improvement in breakdown strength38. On the other hand, by increasing ΔSconfig, both Pmax and Pr will gradually decrease, which signifies weakened ferroelectricity, enhanced relaxor phase, and superior Eb. The suppression of interfacial polarization (IFPs) plays a significant role in elevating the energy storage performance of ceramics. This is because the main parameters are related to ESPs, such as grain size (G), optical band gaps (Eg), breakdown strength (Eb), and diffused phase transition (γ), which directly affect IFPs values. The Niqyest plot of impedance (Zʹ \(\:\&\:\)Z”) of sintered ceramics with (0.0 and 0.1) of Nd-content was recorded at different temperatures (450, 500, 600, and 650 oC), frequency range (20 Hz − 5 MHz with 20000 Hz as frequency step), and the data were depicted in Fig. 6(a, c). As clearly seen, cole-cole plots of present ceramics are achieved semicircles in all applied temperatures, which denote that both Rg and Rgb have contributed to the plot. The diameter of semicircles increased via increasing the amount of Nd ions, as shown in Fig. 6)e). The variation of Z” and M” as a function of frequency of 0.0 and 0.1 was calculated, and the data were displayed in Fig. 6(b, d). Both components show maxima peaks at certain frequencies and indicate the present Rg and Rgb effects. The interface polarization of ceramics has almost decreased as peaks overlapping between Z” and M” decreased. Figure 6(f) represents the variation of Δf and the diameter of radius as a function of ΔS. Clearly observed, the difference frequency between Z” and M” peaks decreased monotonically while the radius of the cole circuit increased as Nd-content and ΔS increased, which means reducing the interfacial polarization and enhancing the resistance grain of the insulator. The present results strongly indicate that the high-entropy material can effectively reduce the interfacial polarization effect, subsequently enhancing the breakdown strength and energy storage performance.

The optical absorption coefficient α of BBZTNx (x = 0.0, 0.05, and 0.1) as a function of various wavelengths was evaluated using the Kubelka–Munk relationship39:

where R is the diffused reflectance and F(R) is the Kubelka–Munk function, which is related to the absorbance (A). α is the linear absorption coefficient, which could be evaluated by using the following expression40,41:

where d is the thickness. The energy (E) dependence of \(\:\alpha\:\:\)obeys the Tauc and Menth formula in the following form42,43,44:

where \(\:{E}_{g}\) is the bandgap energy, and A is a proportionality constant that depends on the transition probability and is associated with the effective masses related to the bands. The exponent (\(\:\gamma\:\)) depends on the transition nature (m = 2 for direct and 1/2 for indirect semiconductor). Figure 7 (a) shows the plotted relation between \(\:{\left(F\left(R\right)E\right)}^{1/2}\) and \(\:{\left(F\left(R\right)E\right)}^{2}\) against (E) for BBZTNx ceramics. The optical energy gap is obtained by extrapolating the linear portion of the curve to the energy axis or by calculating the intercept/slope ratio. All the plots show straight-line portions supporting the interpretation of the direct (\(\:{E}_{g}^{dir}\)) and indirect (\(\:{E}_{g}^{dir}\)) band-gaps for all ceramics under study as represented in Fig. 6(b). As predicted, the introduction of Nd ions to BBZT can increase the Eg values, resulting in an increase in the insulator degree of the material, low concentration of electrons at the conduction band subsequently enhances Eg. The increase in Eg is owing to the wider band gap of Nd2O3 (Eg = 5.6 eV)45 compared to the band gap of BaO (Eg = 4.4 eV)25. The band gap of BBZT increased from 3.2 eV to 3.35 eV as the content of Nd ions increased from 0.0 to 0.1, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The Eg of BBZT is lower than the Eg of pure BT due to the presence of Bi3+, where the Eg of Bi2O3 is 2.58 eV, which lies in the semiconductor band gap.

Ferroelectric properties at low T

To investigate the ferroelectric and relaxor phases of BBZTNx ceramics and confirm dielectric properties below and above room temperature, P-E hysteresis loops of three different samples (0.0, 0.05, and 0.1) of Nd content were performed in a wide low-temperature range (−75 to 50 oC) using liquid nitrogen media and a cryostat sample holder. Pure BBZT sample was divided into two regions based on the dielectric curve as presented in Fig. 8 (a, b). The first region was selected to measure the P-E loop from − 75 to 0.0 oC while the material exhibits long-range order ferroelectric phase below depolarization temperature (Td) according to the (ε-T) curve, while the second region was selected from 25 to 125 oC above room temperature where the material undergoes to the relaxor phase. As clearly seen, the first region shows increases in both Pmax and Pr as temperature increases, which reflects the increase in the domain size by domain wall displacement and enhancement of the ferroelectric phase. This could be present and dominated by the O-phase of BT below room temperature, where the largest polarity of the B-O bond can be achieved at Td. This is confirmed by obtaining the maximum values of Pmax and Pr at Td. By increasing T above Td, both Pmax and Pr decrease as T increases, which confirms the material undergoes the relaxor phase from 0.0 to 125 oC. These results completely agree with permittivity behavior. The compositions that depend on Nd ions (0.05 and 0.1) were measured in only one region based on dielectric behaviors where only one phase transition has been detected in the full range of T as depicted in Fig. 8 (c, d). Similar behavior of both has been observed where Pmax and Pr decreased as T increased, indicating a present relaxor phase with decreasing polarity as T increases, resulting in a weak B-O bond. The high degree of relaxor phase was achieved at 0.1 compound, while the largest Pmax and Pr were obtained at 0.05 composition due to the largest permittivity values compared to the other compositions. For instance, at T = −75 oC, Pmax increased from 3.7 to 13.2 µC/cm2 when Nd content increased from 0.0 to 0.05, and then it decreased from 13.2 to 7.48 µC/cm2 if Nd increased from 0.05 to 0.1. These results reflect that the superior energy storage properties of this system at low temperatures (< RT) can be obtained at 0.05 of Nd-content.

Ferroelectric and esps properties at RT

Figure 9 (a, b) illustrates bi-polar polarization (P), and current (I) hysteresis loops dependent on electric field (E) at ambient temperature and 10 Hz waveform, and the applied field was 50 kV/cm. Clearly observed, the addition of Nd ions clearly affects ferroelectric properties. Pure BBZT with low entropy shows a ferroelectric short-range order P-E loop attributed to forming O-phase at RT. As configurational entropy (ΔS) increases by the addition of Nd ions, Pmax increased while Pr decreased, and the P-E loops tend to slim loop, assuring the break of the LRO of the domain structure and enhancing weakly coupled polar nano-regions (PNRs) of the relaxation phase. The maximum value of Pmax was achieved at Nd = 0.05, attributed to C-O coexistence phases. By increasing the amount of Nd higher than 0.05, a decrease in Pmax was observed, and the lowest value was obtained at 0.1. The decrease in polarization at high entropy signifies an increase in the volume fraction of the cubic phase compared to the O-phase, and this is beneficial for improving breakdown strength and subsequently enhancing ESPs. Meanwhile, the current loop of pure BBZT is characterized by a sharp current peak at Ec corresponding to the domain switching effect, while Imax observed shifted to lower electric fields and decreased with more broadness as Nd-content increased. This evidence reflects the ferroelectric to relaxor phase transition caused by Nd addition. For investigation of energy storage parameters, including Wrec and ƞ of BBZT ceramics as a function of Nd ions, the unipolar P-E loop of all present ceramics was measured at 50 kV/cm, and the data were displayed in Fig. 9(c). The dramatic reduction in both Pmax and Pr values reflects the destruction of the ferroelectric phase and the growth of the relaxor phase. Based on unipolar P-E loops, Wrec and ƞ of BBZTNx ceramics were deduced as a function of Nd-content, and the results were depicted in Fig. 9(e). However, both Pmax, Pr, and ΔP values dependent on Nd-content were displayed in Fig. 9(d). The results show that the maximum values of Pmax and ΔP were achieved at a 0.05 sample, which confirms dielectric and bi-polar ferroelectric properties. Figure 9(e) depicts the unipolar P-E loop of three different compositions (0.0, 0.05, and 0.1) at breakdown strength based on ΔP values in Fig. 9(d). It is worth noticing that the Eb increased from 200 kV/cm to 300 kV/cm as ΔS increased from 0.54 to 0.9. The Eb of BBZTN0.1 is about four times higher than the Eb of pure BT, where ΔS of BT is 0.0. Figure 9(f) showed Wrec and ƞ for 0.0, 0.05, and 0.1 at E = 200 kV/cm for comparison of how the entropy affects the energy storage properties of BBZTN ceramics. The results confirm the most energy storage properties can be achieved at 0.05, where the largest Wrec = 2.75 J/cm3 with excellent ƞ = 93% was obtained which higher than other reported materials such as NBT-based ceramics as shown in Table 146, NBT-AN-based ceramics47, BNKT-based ceramics48, NBT-BZ ceramics49 and NBT-based ceramics50. However, the maximum 96% of ƞ was achieved for BBZTN0.1 sample, attributed to negligible non-180 domain switching and linearity hysteresis loop where the charging and discharging curves nearly coincide with each other’s.

Conclusion

In summary, based on pristine BT ceramics, A- and B-site cation disorder caused by Bi, Nd, and Zr ions were designed by solid-solution techniques to increase their configurational entropy and breakdown strength. Dielectric and optical properties were investigated, and the results revealed that the grain resistance and optical band gap increased as ΔS increased. Breakdown strength was increased to 300 kV/cm at the BBZTN0.1 sample, which is denotes five times higher than pure BT. The ESPs reflect that the most Wrec was achieved at Nd = 0.05 due to O&C co-existence phases at ambient temperature. Superior ƞ ~ 95% was obtained at 0.1 of Nd attributed to suppression of interfacial polarization and elevation grain resistance. This study shows that the high-entropy design and suppression of interfacial polarization can improve the breakdown strength and energy storage performance of perovskite structure ceramics.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

23 August 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Affiliations 1 and 2 were not listed in the correct order. The correct affiliations are: Affiliation 1. Ferroelectric & Piezoelectric Lab, Physics Department, Faculty of Science, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt. Affiliation 2: Applied Colleage at Khulais, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Sarjeant, W. J., Zirnheld, J. & MacDougall, F. W. Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 26[5], 1368–1392 (1998).

Furman, E. et al. High-Temperature, High-Power capacitors: the assessment of capabilities. SAE Int. J. Aerosp, 1 (2008). [1] 822 – 31.

Li, H. et al. Dielectric polymers for high-temperature capacitive energy storage. Chemical Soc. Reviews, 50 (2021). [11] 6369 – 400.

Zeb, A. & Milne, S. J. High temperature dielectric ceramics: a review of temperature-stable high-permittivity perovskites. Journal Mater. Science: Mater. Electron. 26[12] 9243–9255 (2015).

Li, Q. et al. High-Temperature dielectric materials for electrical energy storage. Annual Rev. Mater. Research, 48 (2018). [48, 2018] 219 – 43.

Duran, P. & Moure, C. Piezoelectric ceramics. Mater. Chem. Phys. 15[3], 193–211 (1986).

Yang, L. et al. Perovskite lead-free dielectrics for energy storage applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 102, 72–108 (2019).

Wang, G. et al. Electroceramics for High-Energy density capacitors: current status and future perspectives. Chemical Reviews 121[10] 6124–6172 (2021).

Yao, Z. et al. Homogeneous/Inhomogeneous-Structured dielectrics and their Energy-Storage performances. Adv. Mater. 29[20], 1601727 (2017).

Jian, W. & Zhong-Hui, S. Modeling-guided Understanding microstructure effects in energy storage dielectrics. Microstructures 1[1] 2021006 (2021).

Li, F., Zhang, S., Damjanovic, D., Chen, L. Q. & Shrout, T. R. Local structural heterogeneity and electromechanical responses of ferroelectrics: learning from relaxor ferroelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28[37], 1801504 (2018).

Zhou, L., Vilarinho, P. M. & Baptista, J. L. Dependence of the structural and dielectric properties of Ba1-xSrxTiO3 ceramic solid solutions on Raw material processing. Journal Eur. Ceramic Society, (1999). 19[11] 2015-20.

Shvartsman, V. V., Zhai, J. & Kleemann, W. The dielectric relaxation in solid solutions BaTi1-xZrxO3. Ferroelectrics 379[1] 77–85 (2009).

Lei, C., Bokov, A. A. & Ye, Z. G. Ferroelectric to relaxor crossover and dielectric phase diagram in the BaTiO3–BaSnO3 system. Journal Appl. Phys. 101[8] 084105 (2007).

Beuerlein, M. A. et al. Current Understanding of Structure–Processing–Property Relationships in BaTiO3–Bi(M)O3 Dielectrics, Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 99[9] 2849-70 (2016).

Nayak, S. et al. Effect of A-site substitutions on energy storage properties of BaTiO3-BiScO3 weakly coupled relaxor ferroelectrics, Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 102[10] 5919-33 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Grain-orientation-engineered multilayer ceramic capacitors for energy storage applications. Nature Mater. 19[9] 999–1005 (2020).

Guanfu, L., Liang, C. & He, Q. Energy storage properties of NaNbO3-based lead-free superparaelectrics with large antiferrodistortion. Microstructures 3[2] 2023009 (2023).

Amira, A., Kamal, S. A., Hussein, A. & Salem Abd El-razek Mahmoud, enhancement of entropy induced suppression of interfacial polarization to bolster breakdown strength in (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 - Based ceramics Ceramics International, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.01.036

Amira, A. et al. Simultaneously enhanced of energy storage and energy harvesting performances of [(Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3–BaTiO3] ceramics by addition of SrTiO3 2024. Phys. Scr. 99 055946 .

Sarkar, A. et al. High-Entropy oxides: fundamental aspects and electrochemical properties. Advanced Materials, (2019). 31[26] 1806236

Chen, L. et al. Large energy capacitive High-Entropy Lead-Free ferroelectrics. Nano-Micro Lett. 15[1] 65 (2023).

Yan, B., Chen, K. & An, L. Design and Preparation of lead-free (Bi0.4Na0.2K0.2Ba0.2)TiO3-Sr(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3 high-entropy relaxor ceramics for dielectric energy storage. Chem. Eng. J. 453, 139921 (2023).

Wang, C., Cao, W., Liang, C., Zhao, H. & Wang, C. Equimolar high-entropy for excellent energy storage performance in Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-based ceramics. Energy Storage Mater. 70, 103534 (2024).

Cao, W. et al. Interfacial polarization restriction for ultrahigh Energy-Storage density in Lead-Free ceramics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33[29], 2301027 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Giant energy-storage density with ultrahigh efficiency in lead-free relaxors via high-entropy design. Nature Commun. 13[1] 3089 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Optimizing high-temperature energy storage in tungsten bronze-structured ceramics via high-entropy strategy and bandgap engineering. Nature Commun. 15[1] 5869 (2024).

Babeer, A. M., Ali, A. F. & Kamal, A. A. and A. E.-r. Mahmoud, A-site disorder induced ferroelectric to relaxor phase transition of Na(Nb0.75Ti0.25)O3 ceramics by Bi3+ for ultra-high energy storage properties, Materialia, 33 102009 (2024).

Babeer, A. M., Ezzeldien, M., Ali, A. F. & Mahmoud, A. E. Moderation of [Bi3+/Na1+] molar ratio for enhancement of dielectric and energy storage properties of NaNbO3 ceramics, Physica Scripta, 99[5] 055901 (2024).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Enhanced energy storage and temperature-stable dielectric properties in (1-x)[(Na0.4K0.1Bi0.5)0.94Ba0.06TiO3]-xLa0.2Sr0.7TiO3 lead-free relaxor ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 985, 174016 (2024).

Rehman, M. U. et al. Enhanced Energy Storage Performance of MnO2-Modified 0.92BaTiO3–0.08Bi(Mg0.5Ce0.5)O3 Ceramics for Capacitor Applications, ACS Applied Electronic Materials, 5[8] 4564-75 (2023).

Cao, L., Yuan, Y., Li, E. & Zhang, S. Relaxor regulation and improvement of energy storage properties of Sr2NaNb5O15-based tungsten bronze ceramics through B-site substitution. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 127846 (2021).

Zhao, P. et al. Novel Ca doped Sr0.7Bi0.2TiO3 lead-free relaxor ferroelectrics with high energy density and efficiency. Journal Eur. Ceramic Society, (2020). 40[5] 1938-46.

Mahmoud, A. E., Ezzeldien, M. & Parashar, S. K. S. Enhancement of switching/un-switching leakage current and ferroelectric properties appraised by PUND method of (Ba1-xCax)TiO3 lead free piezoelectric near MPB. Solid State Sci. 93, 44–54 (2019).

Ezzeldien, M., Mohamed, W. S., Al-Qaisi, S., Ameen, I. G. & Mahmoud, A. E. Enhancement of energy storage and pyroelectric properties of (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-SrTiO3-BaTiO3 ceramics by addition of (Ba0.9B0.1)TiO3 glass-phase, Physica Scripta, 99[10] 105935 (2024).

Ezzeldien, M., Beagan, A. M., Alvi, P. A. & Mahmoud, A. E. Effect of ZrO2 addition on the BO6 vibration modes of [(Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3 – SrTiO3 – BaTiO3] perovskite structure for enhancement energy storage properties. Results Phys. 58, 107445 (2024).

Mahmoud, A. E., Kamal, A. A., Ezzeldien, M. & Babeer, A. M. [Bi3+/Zr4+] induced ferroelectric to relaxor phase transition of BaTiO3 ceramic for significant enhancement of energy storage properties and dielectric breakdown strength. Applied Phys. A, 1306415 (2024).

Umesh, B. et al. Synthesis and characterization of spherical and rod like nanocrystalline Nd2O3 phosphors. Journal Alloys Compd. 509[4] 1146–1151 (2011).

Kubelka, P. New contributions to the optics of intensely Light-Scattering materials. Part I. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 38(5), 448–457 (1948).

Yakuphanoglu, F., Mehrotra, R., Gupta, A. & Muñoz, M. Nanofiber organic semiconductors: the effects of nanosize on the electrical charge transport and optical properties of bulk polyanilines. Journal Appl. Polym. Science, 114 (2009). [2] 794 – 99.

Aly, K. A. Swanepoel method for estimating the film thickness and complex index of refraction by using only the lower envelope: special case. Mater. Chem. Phys. 310, 128458 (2023).

Aly, K. A., Abousehly, A. M., Osman, M. A. & Othman, A. A. Structure, optical and electrical properties of Ge30Sb10Se60 thin films. Physica B: Condens. Matter 403[10] 1848–1853 (2008).

Yakuphanoglu, F. Electrical characterization and device characterization of ZnO microring shaped films by sol–gel method. Journal Alloys Compounds, 507 (2010). [1] 184 – 89.

Lee, S., Woodford, W. H. & Randall, C. A. Crystal and defect chemistry influences on band gap trends in alkaline Earth perovskites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92[20], 201909 (2008).

Wang, C. et al. Ultrahigh Energy-Storage density of BaTiO3-Based ceramics via the interfacial polarization strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 15[, 42774–42783 (2023).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Kyung-Hoon cho, enhanced temperature stability of dielectric permittivity and energy storage properties of BNT-based lead-free relaxor ceramics. Ceram. Int. 51, 12049–12059 (2025).

Zheng, S., Li, Q., Chen, Y., Yadav, A. K. & Wang, W. Enhanced energy storage density with excellent temperature-stable dielectric properties of (1-x)[(Bi0.5Na0.5)0.94Ba0.06TiO3]-xAgNbO3 leadfree ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 911, 165019 (2022).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Enhanced energy storage properties and excellent fatigue resistance of Pb-free Bi0.47Na0.376K0.094Ba0.06Nb0.024Ti0.97 – x(Ta0.24Sn0.7)xO3 relaxor ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 923, 166324 (2022).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Enhanced storage energy density and fatigue free properties for0.94Bi0.50(Na0.78K0.22)0.50Ti1-x(Al0.50Nb0.50)xO3-0.06BaZrO3 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 46, 17044–17052 (2020).

Yadav, A. K. et al. High energy storage density and stable fatigue resistance of Na0.46Bi0.46Ba0.05La0.02Zr0.03Ti0.97-xSnxO3 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 46, 5681–5688 (2020).

H. et al. Leadfree BaTiO3-Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-Na0.73Bi0.09NbO3 relaxor ferroelectric ceramics for high energy storage. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 3303–3311 (2017).

Chen, C. S. et al. Improved energy storage in antiferroelectric AgNbO3-modulated 0.925Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3–0.075BaTiO3 relaxor ferroelectric ceramics. Ceram. Int. 48, 35452–35460 (2022).

Ma, W. et al. Enhanced energy-storage performance with excellent stability under low electric fields in BNT–ST relaxor ferroelectric ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 281–288 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Energy storage properties of (Bi0.5Na0.5)0.93Ba0.07TiO3 lead-free ceramics modified by La and Zr co-doping. J. Materiomics. 2, 87–93 (2016).

Shi, P. et al. Large energy storage properties of lead-free (1-x)(0.72Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-0.28SrTiO3)-xBiAlO3 ceramics at broad temperature range. J. Alloys Compd. 784, 788–793 (2019).

Cao, W. et al. High-energy storage density and efficiency of (1 – x)[0.94 NBT–0.06 BT]–xST lead-free ceramics. Energy Technol. 3, 1198–1204 (2015).

Xu, Q. et al. Structure and electrical properties of lead-free Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-based ceramics for energy-storage applications. RSC Adv. 6, 59280–59291 (2016).

Yao, M., Pu, Y., Zhang, L. & Chen, M. Enhanced energy storage properties of (1-x)Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-xBa0.85Ca0.15Ti0.9Zr0.1O3 ceramics. Mater. Lett. 174, 110–113 (2016).

Si, F., Tang, B., Fang, Z., Li, H. & Zhang, S. Enhanced energy storage and fast chargedischarge properties of (1-x)BaTiO3-xBi(Ni1/2Sn1/2)O3 relaxor ferroelectric ceramics. Ceram. Int. 45, 17580–17590 (2019).

Li, W. B., Zhou, D., Xu, R., Pang, L. X. & Reaney, I. M. BaTiO3–Bi(Li0.5Ta0.5)O3, lead-free ceramics, and multilayers with high energy storage density and efficiency. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 5016–5023 (2018).

Jayakrishnan, A. R., Karthik Yadav, P. V., Silva, J. P. B. & Sekhar, K. C. Microstructure tailoring for enhancing the energy storage performance of 0.98[0.6Ba(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3-0.4(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3]-0.02BiZn1/2Ti1/2O3 ceramic capacitors. J. Sci. : Adv. Mater. Devices. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2019.12.001 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. (UJ-24-DRK-524-1). Therefore, the authors thank the University of Jeddah for its technical and financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amira. A. Kamal: Samples Preparation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Resources, Review & editing.Asmaa Al-Rasheedi: Review & editing.K.A.Aly: Methodology, Review & editing.Abd El-razek Mahmoud: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamal, A., Al-Rasheedi, A., Aly, K.A. et al. Suppression of interfacial polarization via enhancement of entropy, grain resistance and optical band-gap strategies in perovskite ceramics. Sci Rep 15, 22371 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03386-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03386-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancement of Energy Storage Properties of (Ba,Sr)Nb2O6–AgNbO3 Composite Ceramics via Entropy and Interfacial Polarization Strategies

Journal of Electronic Materials (2025)