Abstract

Absorber materials are developed to reduce electromagnetic radiation and ensure the compatibility of the operation of electronic equipment in environments subject to interference. This work presents the development of a low-cost textile electromagnetic absorber for 4G and 5G technologies, operating at frequencies of 2.5 GHz and 3.5 GHz. The proposed electromagnetic absorber utilizes a 1 mm-thick Denim substrate, with a graphite composite used in the agricultural and commercial polyvinyl acetate glue industry, with the relationship of 25 wt%. The measurements were carried out in a Vector Network Analyzer, model E5071C Agilent Technologies, with the characterization of the Denim substrate, the glue, and the identification of the best parameters for the construction of the absorber. In the project, three low-cost textile absorbers prototypes were fabricated, with G1 = 0.25 mm, G2 = 0.35 mm, and G3 = 0.5 mm of thickness layers of the composite deposited on a Denim fabric. The results indicate that the absorber prototypes G2 presents great results in the frequency range of 4G and 5G band, with a maximum absorption of 26.6 dB in 3.94 GHz, with a structure 98.83% thinner than the commercial absorber LF-75. The variation in absorption performance may be attributed to the different mechanisms by which the absorbers operate: the commercial absorber LF-75 primarily interacts with the magnetic field, whereas the textile prototype predominantly affects the electric field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Materials that absorb electromagnetic radiation are designed to capture incident energy and dissipate it through the Joule effect or mutual phase cancellation of incident and reflected waves1. Military-grade electromagnetic absorbers are used in stealth technology to camouflage aircraft, tanks, and ships by reducing their radar signature2. The increasing use of electronic devices has increased radiation pollution and electromagnetic interference, resulting in harmful biological effects on the human body and failures in electronic systems3. With the development of electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) and protection standards across industries such as transportation, telecommunications, and medicine, electromagnetic absorbers have become essential for ensuring the proper operation of devices and systems that emit electromagnetic energy. The expansion of terrestrial and satellite wireless communications, 5G and 6G mobile networks, Industry 4.0, the Internet of Things (IoT), smart farms, smart cities, and smart grids—all of which demand low interference and high electromagnetic compatibility—has driven significant advancements in the research and development of electromagnetic wave-absorbing materials2.

The absorption property of electromagnetic waves from absorbers is obtained from the electrical characteristics of conductivity, permittivity, and permeability of the materials. The properties can be used alone or in combination to achieve better absorption. Absorber materials can be classified according to the absorption mechanism, being divided into resistive, dielectric and magnetic1,2. The resistive type absorber acts based on the interaction of the incident wave with the conductivity and permittivity parameters of the material, using the components carbon black, graphite, silicon carbide or metal-based material. The dielectric type operates on the loss in the process of polarization and dielectric relaxation, using barium titanate, ferroelectric ceramics, and materials containing carbon, such as rubber, urethane, or polystyrene foams. Magnetic type acts on resonance and hysteresis losses, using ferrite and ferrocarbonyl.

A combination of different types of materials can be employed in order to improve the absorption efficiency of the absorber4. According to5,6,7, the suspension of graphite powder in a liquid, water, alcohol, petroleum oil, or others, mixed in quantity with a polymeric binder is generally called colloid of graphite. The colloidal graphite coating applied to a surface will produce the formation of a conductive material through direct contact with the graphite particles due to the complete evaporation of the liquid; the resulting material can be used as electromagnetic shielding. The choice of the types of graphite and polymer used in the colloid, associated with their dosages and the preparation method, are important in determining the frequency response of the absorber.

Several works seek to develop electromagnetic wave absorbers at different frequencies and with different types of techniques and materials. In the work of8 low-cost absorbers composed of rose-derived porous carbon and magnetic cobalt (Co)/nickel (Ni) nanoparticles (RC/Co and RC/Ni) were synthesized by simple impregnation and carbonization methods, which produced a minimum reflection of − 47.89 dB at 13.60 GHz and an effective attenuation width of 4.08 GHz for the RC/Co absorber with a thickness of 1.56 mm, while the RC/Ni absorber with a thickness of 1.58 mm obtained a minimum reflection of − 45.36 dB at 12.88 GHz at an effective width of 3.02 GHz. In the work of9 a textile absorber coated with polyvinylidene fluoride, filled with graphene nanoplates, was proposed, operating in the 8–18 GHz band, with results below − 5 dB reflection coefficient throughout the range and bandwidth of -10 dB. In the work of10, an absorber with a thickness of 4 mm was developed, consisting of a composite of Fe3O4 and graphite operating in the C band, 4–8 GHz, with a maximum return loss of – 40.6 dB, and − 29.82 dB in the Ku band, 12–18 GHz. In11 a microwave absorber made from biomass derivatives was developed, a hybrid of Co3Fe7 alloy nanoparticles anchored in porous carbon nanosheets, with a reflection loss of − 22.3 dB in the band Ku. In the work of12, was developed a microwave absorber from the manganese/cobalt urea complex and reduced and nitrogen-doped graphite oxide, by the hydrothermal method, in the range of 2 GHz to 8 GHz, with reflection losses of − 103 dB at 2.9 GHz. The work of13 evaluated absorbers using the morphologies of intercalated graphite, expanded graphite, and exfoliated graphite, operating in the X band, 8–12 GHz, and in the Ku band, 12–18 GHz, with a maximum attenuation of -22.5 dB for samples of 2 mm. An absorber constructed with carbon black/epoxy resin and ferrite/epoxy resin double-layer nanocomposites was developed by14 operating in the frequency ranges of 8–18 GHz, and reflection loss of -24.0 dB. In the project by4, three absorbers were developed, with graphene/ferrite, graphene/conductive polymer, and graphene-based ternary composites, operating in the 2–8 GHz bands, with a maximum attenuation of -18dB at 18 GHz. An absorber with metamaterial behavior, composed of graphite, was developed by6, operating in the 12.7–18 GHz bands with an absorption rate below − 10 dB. In15, a cobalt sulfide-polyvinylidene fluoride absorber composite was presented, operating in the 2–18 GHz bands, with a maximum absorption of -43 dB at 6.6 GHz. In16 a single-layer microwave absorber with metal support based on polyaniline/expanded graphite reinforced novolac phenolic resin composites in the range of 8.2 GHz to 12.4 GHz was presented, with a reflection loss of -32 dB at 9.7 GHz and − 10 dB at a width of 2.4 GHz, in the thickness of 3 mm. A microwave absorber produced with two layers of composites in two combinations, cobalt ferrite/epoxy and graphite/epoxy was developed in17, operating from 8 GHz to 18 GHz, with reflection loss results of − 12.8 dB at 8 GHz and − 15 dB at 10 GHz. In the work of18, a ternary composite of titanium oxide/polyaniline/graphene oxide was synthesized by in situ oxidation polymerization, obtaining reflection loss of -51.74 dB at 9.67 GHz, with − 10 dB at a width of 3.91 GHz at 3.12 mm thickness, and loss of -15.28 at 10.28 GHz, with − 10 dB at a width of 4.76 GHz at 2.5 mm thickness. In19 a compound of natural microcrystalline graphite and low-density polyethylene prepared by the extrusion calendering method was presented, obtaining an attenuation of -5 dB at 6.79 GHz and − 10 dB at 3.02 GHz, with respective reflectivity values of -12.44 dB and − 20.46 dB.

In this work, an electromagnetic wave absorber is developed using a composite of graphite and commercial white glue based on polyvinyl acetate (PVAc), applied to a denim. In addition to this Introduction, this work consists of three more sections. In “Material and methods” section, the Materials and Methods used in the development of the project are presented. “Results and discussions” section presents the results and discussions of the developed low-cost textile prototype, and “Final considerations” section presents the final considerations of the proposed work.

Material and methods

Electromagnetic absorbers are characterized according to the magnitudes of electrical permittivity (\(\:\epsilon\:\)), magnetic permeability (\(\:\mu\:\)) and conductivity (\(\:\sigma\:\)), angular frequency of the incident wave (\(\:\omega\:\)), with \(\:\omega\:=2\pi\:f,\) and \(\:f\) is the resonance frequency of the system, the loss tangent \(\:tg\left(\delta\:\right)\:\)and the impedance (\(\:z\)) of the material. Interaction of electromagnetic waves incident on a material, depending on the frequency, can cause electrical and magnetic losses, identified by complex permittivity \(\:\left({\epsilon\:}_{c}\right)\) and complex permeability \(\:\left({\mu\:}_{c}\right)\). The performance of an absorber is associated with the sizing of area, thickness, choice of the type of material, and the different systems operating frequency ranges. The absorber proposed in this work considers the dielectric response, permittivity, conductivity, loss tangent, and angular frequency as important parameters for determining the device.

In the process of absorption of electromagnetic energy by the absorbers, are considering the components of the magnetic field and electric field, which, when incident on the structure, are transforming into an electric current density, a potential difference and heat by the Joule effect.

A non-perfect dielectric has a loss caused by finite conductivity and polarization of isolated or combined modes in the material. According to Ohm’s law, the electric field in the dielectric produces a conduction current density, given by:

where E is the electric field incident on the material, which results in energy dissipation as heat, and, as a result, attenuation of the incident wave because of conductivity loss20. The inability of the dipoles of the dielectric molecules caused polarization loss to follow the rate of change of the applied electric field. If the relaxation time for the dipoles to return to their initial random state is less than or comparable to the rate of electrical oscillation of the field, then there will be no loss. However, when the rate of the electric field oscillates much faster than the relaxation time, polarization cannot follow the frequency oscillation, resulting in energy dissipation as heat21. Conductivity and polarization losses can be called the effective conductivity of the dielectric, given by20:

were \(\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\) is the imaginary part of the complex permittivity, which is related to the interaction of the electric field with the material, and the real component, given by:

The dielectric constant indicates how much energy from an external field was stored in dielectric loss because of polarization, and the complex permittivity can be obtained by20:

using Maxwell’s equation, it is possible to relate the intrinsic values of the material to the incident electric field, indicated by:

The loss tangent is a measure that expresses how much of the electric field incident on a material is dissipated and how much is stored, which can be obtained from (5). Loss tangent is the relationship between the losses of a material and its electric field storage capacity (6). The angle δ is called the loss angle of the medium and can vary from \(\:{0}^{0}\le\:\delta\:<{90}^{0}\). Although there is no well-defined boundary between good conductors and lossy dielectrics, a dielectric medium has \(\:tg\:\delta\:\ll\:1\), and a good conductor has \(\:tg\left(\delta\:\right)\gg\:1\), with the loss tangent given by22,23:

In an electromagnetic absorber, it is desirable that most of the incident wave is dissipated. The loss tangent is an important parameter in the evaluation of absorbing materials. Therefore, the estimated values of the imaginary part of permittivity and conductivity are important in determining absorption. \(\:\sigma\:\ll\:\omega\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\:\)must also be considered for microwave frequencies. Thus, (6) can be simplified by:

In this work, a low-cost, flexible textile absorber is developed, based on graphite colloid and glue, on a Denim substrate for the range from 2 GHz to 3.5 GHz. The activities carried out were distributed in the following stages: selection, separation, and characterization of the materials used in the development of the project. The materials used in the project are graphite, as a component that will act on the electric field component of the wave, PVA glue, which acts as a binder, and Denim, which is a dielectric material.

The absorption mechanism of the absorber can be explained by propagation theory, in which electromagnetic waves are consumed within the material through one or more pathways, such as electrical loss, magnetic loss, dielectric loss, and polarization loss24. According to25 when an electromagnetic wave falls on an absorber, most of the power should be absorbed by the material, providing the minimum of reflected waves in the media. In the absorber proposed by25, Fig. 1a, absorption is the result of the loss of power through the Joule effect on the surface or in the multiple internal reflections of the absorber, because of the interaction of the incident electromagnetic waves with the free and polarized charges of the material. Depending on the application mode of the absorber, a conductive plate can be introduced at the end of the material to reduce the power of the transmitted wave and increase the interactions of the reflected waves in the internal part of the absorber. Figure 1b shows the proposed textile absorber, with the indication of level with thickness of \(\:{\delta\:}_{G}\) of the graphite and glue composite, deposited on the denim textile material of thickness \(\:{\delta\:}_{T}\). The objective is to increase the efficiency of electromagnetic absorption, with the reduction of the production cost, by using low-cost, low-cost, lightweight, flexible and thin absorber. The textile absorber is resistive, with loss tangent defined by (6), in which the composite, graphite and glue, contributes with the conductivity (\(\:\sigma\:\)) and imaginary permittivity (\(\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}})\). portions.

Principle of electromagnetic absorption adapted by25: (a) generic absorber; (b) textile absorber.

The graphite

Graphite is an allotrope of carbon and does not fit into any of the traditional classification schemes for metals, ceramics, and polymers26. In the structure of graphite, carbon atoms are located at the vertices of hexagons arranged in regular planes or “blades”. In these planes, each carbon bonds strongly to three others through three strong bonds and one weak bond through Van der Waals forces. The structural arrangement allows one plane to slide over another, which is why graphite is a soft and brittle material, used in brake shoes, lubricating powders, welding electrodes, motor brushes, and pencils. The length of the sides of the hexagon is 0.142 nm and the spacing distance between the planes is 0.335 nm27.

The electrical conductivity of graphite is explained because, with sp2 hybridization, there is an electron left in the p orbital that does not participate in hybridization. This electron forms a π bond with another carbon atom in the plane, thus producing two bonds between them, formed by the sp2 orbitals and the p orbitals. The electrons involved in the π bond can move in an electron cloud over each plane of the graphite, but there is no displacement of electrons between the planes28. The graphite can be considered a semimetal, a electrical conductor in the basal plane and an insulator normal to the basal plane. Free electrons are highly mobile, and their movement in response to the presence of an applied electric field in a direction parallel to the plane is responsible for the relatively low resistance, that is, high conductivity, which implies an electrical resistivity on the order of \(\:{10}^{-5}\:{\Omega\:}m\) in the plane, and of \(\:{10}^{-2}\:{\Omega\:}m\) between the planes26.

PVAc glue

According to7, polymers are classified as insulators and conductors. In the category of insulating polymers are polystyrene, polyvinylidene fluoride, polypropylene, polymethyl methacrylate, polyvinyl alcohol or PVA, polyethylene, polyvinylpyrrolidone and epoxy. Conductive polymers are those that achieve electronic properties when doped. However, its synthesis, cost, and availability commercial use. Examples of this category are polyaniline, polypyrrole, and poly-3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene.

PVA and PVAc are polymers produced from the vinyl acetate monomer, in which PVA is the result of the polymerization of PVAc, as the vinyl alcohol monomer does not exist in stable form29,30. PVA is a water-soluble synthetic product used in the construction, pharmaceutical, and biomedical industries, with molecular formula (C2H4O)n. PVAc, with a molecular formula of (C4H6O2)n, is used in adhesive formulations of glues and as binders in the paper and paint industries31. In this work used a commercial white glue, a product based on PVAc, and not pure PVAc and PVA, for reasons of availability and lower cost, which does not require additional preparation in the laboratory.

Dielectric material characterizations

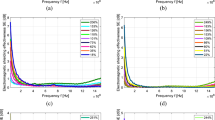

In project development were carried the dielectric characterizations of the permittivity, ε’, and loss tangent, \(\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}/\epsilon\:{\prime\:}\), of the Denim by the open coaxial probe method. Based on empirical tests carried out with PVAc-based white glue with a thickness of less than 1 cm, it can be assessed that the glue only acts as a binder in the process, not contributing to the variation in the dielectric characteristics of the colloid.

The measurements were performed on the IFPB Telecommunications Measurements Laboratory, João Pessoa campus, with the vector network analyzer (VNA) model E5071C adapted with a WR-90 calibration kit manufactured by Agilent Technologies32. Figure 2 shows the characterization of Denim, with the measurement setup, Fig. 2a, and the results of permittivity and loss tangent, Fig. 2b, in the 2 to 4 GHz bands. Denim presented permittivity with \(\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}<0.9\) and average of 0.23, and loss tangent \(\:{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}/{\epsilon\:}^{{\prime\:}}<0.98\:\)and average of 0.2.

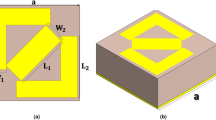

Development of the textile electromagnetic absorber

The powdered graphite colloid added to the liquid glue was prepared using a mechanical shaker at room temperature. The mixture in colloidal form was passed onto one surface of the Denim substrate. After drying, it was noted that the fabric remained flexible, as seen in Fig. 3, with the preparation of the graphite colloid, Fig. 3a, and the textile absorber, Fig. 3b. For the project, three low-cost textile prototypes were built, with colloid thicknesses of G1 = 0.25 mm, G2 = 0.35 mm, and G3 = 0.5 mm, with the relationship of 25 wt% of graphite, which demonstrated the initial absorption effect of electromagnetic waves.

Measuring the reflection (S11) and transmission (S21) parameters

Measuring the reflection (S11) and Transmission (S21) parameters of the textile absorbers were carried out at the Telecommunications Measurements Laboratory of the Federal Institute of the Paraiba (IFPB), using the Vectorial Network Analyzer (VNA) model E5071C Agilent Technologies and Double Ridge Guide Horn Antenna model SAS-57 by A.H. Systems inc. The measurements of S11 and S21 were carried out using the free space electromagnetic characterization method, in which two antennas connected to the VNA, in the distance of the far field33. The absorbers were fixed to an acrylic support positioned between the two antennas, as observed in Fig. 4. The measurement results of the low-cost textile prototypes were compared with a commercial absorber, the LF 75, 30 mm thick, made of polyurethane and ferrite, by Soliani EMC company, Fig. 4b.

Results and discussions

In the analysis of electromagnetic wave low-cost textile absorber prototypes were performed measurements of resistance, with is the inverse of conductance, reflection and transmission of the electromagnetic wave, with the comparison of the results with the commercial absorber LF75 30 mm thick.

The electrical resistance of materials

Electrical resistance can be used as a parameter to approximate conductivity, as conductivity (σ) is the inverse of resistance (R), thus, \(\:\sigma\:=1/R\). Electrical resistance measurement was performed with the Minipa model ET 2042-E multimeter, in the \(\:600\:{\Omega\:}\) range. Figure 5 shows the measured results of electrical resistance of low-cost textile prototypes and commercial absorbers. The absorbers present a difference in resistance depending on the distance between the terminals, demonstrating that the bottom of the textile absorbers remains without conductivity. From the electrical resistance results, it is observed that the prototype G3 obtained resistance of \(\:196\:{\Omega\:}\), and the LF-75 of\(\:\:310\:{\Omega\:}\), with a value closer to the commercial absorber, even with a difference in thickness of 29.5 mm. Calculating the conductivity values, considering the highest values, we have the results of G1 = 0.041 S/m, G2 = 0.167 S/m, G3 = 0.005 S/m, and LF-75 = 0.003. Thus, the G3 absorber had 40% greater conductivity than the LF-75, with a total thickness of 95% less.

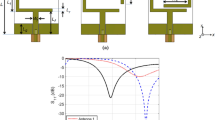

Result of reflection coefficient parameters (S11)

Figure 6 shows the comparison of the reflection coefficient (S11) parameter of the low-cost textile prototype textile absorber and the LF-75 absorber with 30 mm thickness, in the range of 1 GHz to 10 GHz. In the evaluation of reflection results, it is possible to observe that the low-cost textile prototypes G2 and G3 present greater compatibility with the LF-75 absorber. The G3 low-cost textile prototype absorber, Fig. 6(c), presented similar results in the range of 1 GHz to 8 GHz, indicating that the colloid with 0.5 mm obtained reflection results of the commercial absorber, Fig. 6(d), in the range proposed in the project, of 2 GHz to 4 GHz, covering the 5G band technology.

Results of transmission coefficient parameter (S21)

Figure 7 shows the comparison of the transmission coefficient parameter of the low-cost textile prototype absorbers and the LF-75 commercial absorber. The results of the textile prototypes show absorption curves close to the commercial absorber LF-75, with greater absorption of the prototypes G1 and G2 at frequencies from 3.5 GHz to 4.5 GHz, from 8.5 to 9.5 GHz, and lower absorption related to the prototype G3, at frequencies from 3.5 to 6.5 GHz, Fig. 7a. Figure 7b shows the comparison of the absorber at the 4G and 5G frequencies, from 2 GHz to 4 GHz. In the comparison with the commercial absorber LF-75, the G2 absorber prototype presented the best response at the frequencies of 2 to 3 GHz, and the G1 prototype at the frequencies of 3 GHz to 4 GHz.

Figure 8 compares the electromagnetic energy-absorbing, in dB, of the low-cost textile prototype absorbers and the LF-75 commercial. As observed in Fig. 8a, the commercial absorber LF-75 presented greater stability at frequencies from 1 GHz to 10 GHz, with absorption between 3 and 10 dB. The prototype absorbers G1 and G2 presented greater absorption values between frequencies from 2 GHz to 4.5 GHz, and the prototype G1 presented greater absorption at frequencies from 7.5 GHz to 9.5 GHz, with a maximum of 45 dB at 8.74 GHz. From Fig. 8b, it is possible observed that the absorber prototype G2 presented significant results at the range of 2 GHz to 4 GHz, with a maximum of 26.6 dB in 3.93 GHz. The textile absorber prototype presented significant results in a range of 3.0 GHz to 4.0 GHz, with 21 dB in 3.4 GHz, and 34.5 dB in 3.85 GHz.

From the results, it is possible to understand that the G1 and G2 absorber prototypes presented results close to the commercial absorber LF-75 at frequencies from 2 GHz to 4 GHz. Greater absorption is observed in the textile prototype G2, with an average of 10.2 dB, and a maximum of 26.6 dB at 3.93 GHz, in a structure 98.83% thinner than the commercial absorber LF-75.

Final considerations

This work presents the development of a low-cost textile planar microwave absorber designed to operate in the 4G and 5G frequency bands. The prototype absorber consists of a composite of powdered graphite and polyvinyl acetate-based glue, applied to a Denim fabric substrate. The dielectric characterization of the prototypes was conducted using a Vector Network Analyzer, model E5071C from Agilent Technologies. The results were compared with those of a commercial polyurethane and ferrite-based foam absorber (LF-75) with a thickness of 30 mm. As part of the project, three low-cost textile absorber prototypes were fabricated, with G1 = 0.25 mm, G2 = 0.35 mm, and G3 = 0.5 mm-thick composite layers. The results indicate that the G1 and G2 prototypes exhibited absorption performance comparable to the commercial LF-75 absorber in the 2 GHz to 4 GHz frequency range. The G2 prototype demonstrated the highest absorption, with an average of 10.2 dB and a peak absorption of 26.6 dB at 3.93 GHz, while being 98.83% thinner than the LF-75 commercial absorber.

Data availability

The author of the manuscript “Electromagnetic Textile Absorber Applied to 4G and 5G Bands” declares himself the creator of the datasets supporting the research work. The owner authorizes the use of the data without restrictions.The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Scientific Reports Files repository, https://uemabr-my.sharepoint.com/:f:/g/personal/paulofernandes_professor_uema_br/ElGFraf1Sq5Pn4OH_EEmRjEBpmXDRRIMZg6i8YX3wgR_vg?e=FUzbb2.

References

Duan, Y. & Guan, H. Microwave Absorbing Materials (Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd, 2017).

Morais, D. H. 5G NR, Wi-Fi 6, and Bluetooth LE 5: A Primer on Smartphone Wireless Technologies (Springer, 2023).

Shivamurthy, R. B. J., Gowda, B., Kumar, S. B. B. & Chandra, S. M. Flexible linear Low-density polyethylene laminated aluminum and nickel foil composite Tapes for electromagnetic interference shielding. Eng. Sci. (2023).

Chang, M., Liu, A., Zhang, F. & Liu, J. Graphene-based Absorbing Material, in International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT) (Guangzhou, 2019).

Chung, D. D. L. Review: Electrical applications of carbon materials. J. Mater. Sci. 39, 2645–2661 (2004).

Chen, X. et al. A Graphite-Based metamaterial microwave absorber. IEEE Antennas. Wirel. Propag. Lett. 18, 1016–1020 (2019).

Aswathi, M. K., Rane, A. V., Ajitha, A. R., Thomas, S. & Jaroszewski, M. EMI shielding fundamentals, in Advanced Materials for Electromagnetic Shielding: Fundamentals, Properties and Applications, (eds Thomas, M., Rane, S. & Jaroszewski, A.) 1–8 (Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2019).

Wang, W. et al. Rose-derived porous carbon and in situ fabrication of Cobalt/Nickel nanoparticles composites as High-Performance electromagnetic wave absorber. Engi. Sci. (2024).

D’Aloia, A. G., Bidsorkhi, H. C., Bellis, G. & Sarto, M. S. Graphene based wideband electromagnetic absorbing textiles at microwave bands. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compatib. 64(3), 710 – 711 (2022).

Wang, L., Su, S. & Wang, Y. Fe3O4 – Graphite composites as a microwave absorber with bimodal microwave absorption.5, 17565–17575 (2022).

Zhao, H., Jin, C., Lu, P., Xiao, Z. & Cheng, Y. Biomass-derived ultralight superior microwave absorber towards X and Ku bands. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 626, 13–22 (2022).

Ghosh, K. & Srivastava, S. K. Fabrication of Ndoped reduced graphite oxide/MnCo2O4 nanocomposites for enhanced microwave absorption performance. Langmuir J. - ACS Publ. 2213–2226 (2021).

Batista, A. F. et al. Investigation of different graphite morphologies for microwave absorption at X and Ku-band frequency range. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 19064–19073 (2020).

Ibrahim, I. R. et al. A study on microwave absorption properties of carbon black and Ni0.6Zn0.4Fe2O4 nanocomposites by tuning the matching-absorbing layer structures. Sci. Rep. 10(3135), 1–14 (2020).

Wu, Q. et al. Enhanced Wave Absorption and Mechanical properties of Cobalt Sulfide/PVDF Composite Materials 1–12, (Julho, 2019).

Mahanta, U. J., Gogoi, J. P., Borah, D. & Bhattacharyya, N. S. Dielectric characterization and microwave absorption of expanded graphite integrated polyaniline multiphase nanocomposites in X-band. 26, 194–201 (2019).

Ismail, I. et al. Single and double-layermicrowave absorbers of cobalt ferrite. J.Supercond. Novel Magn. 32, 935–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-018-4749-x (2019)

Jia, Q. et al. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2/polyaniline/graphene oxide bouquet-like composites for enhanced microwave absorption performance. J. Alloys Compd. 710 717–724 (2017).

Xie, W. et al. Electromagnetic absorption properties of natural microcrystalline graphite. Mater. Des. 90, 38–46 (2016).

Wentworth, S. M. Eletromagnetismo Aplicado: Abordagem Antecipada Das Linhas De Transmissão 1st edn (Bookman, 2009).

Ahmad, Z. Polymeric dielectric materials, in Dielectric Materials, 1st ed., (ed Silaghi, M. A.) 3–26 (InTech, Rijeka, Croatia2012).

Hayt, W. H. Jr & Buck, J. A. Eletromagnetismo 8th edn (Bookman, 2013).

Sadiku, M. N. O. Elementos De Eletromagnetismo 5th edn (Bookman, 2012).

Cheng, L. et al. Current advances and future perspectives of MXenebased electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Springer Nat. 172, 1–18 (2023).

Azis, M. F., Ismail, R. S., Muhammad, I. & Elmahaishi, F. D. A review on electromagnetic microwave absorption properties: Their materials and performance. J. Mater. Res.Technol. 20, 2188–2120 (2022).

Callister, W. D. & Rethwisch, D. G. Ciência E Engenharia Dos Materiais 10th edn (LTC, 2021).

Chung, D. D. L. Review graphite. J. Mater. Sci. 475–1489(2002).

Pieson, H. O. Handbook of Carbon, Graphite, Diamond and Fullerenes Properties: Processing and Applications (Noyes, 1995).

Patachia, S., Valente, A. J. M., Papancea, A. & Lobo, V. M. M. Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) [PVA]- Based Polymer Membranes (Nova Science Publishers, Inc, 2009).

Ebewele, R. O. Polymer Science and Technology (CRC Press LLC, 1996).

Minge, M. & Amann, O. Biodegradability of Poly(vinyl acetate). Adv. Polym. Sci. 245, 137–172 (2011).

Keysight Measurement of Dieletric Material Properties. [Online]. (2020). Agosto https://www.keysight.com/us/en/assets/7018-01284/application-notes/5989-2589.pdf.

ROHDE & SCHWARZ. maio) Measurement of Dieletric Material Properties. [Online]. (2012). https://cdn.rohde-schwarz.com/pws/dl_downloads/dl_application/00aps_undefined/RAC-0607-0019_1_5E.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Graduate Program in Electrical Engineering (PPGEE) of UFMA, the CAPES, PDPG-AMAZONIA-LEGAL, Process nº. 88887.003296/2024-00, Graduate Program in Mechanical Engineering (PPGMEC) of Federal Institute of Maranhão (IFMA) for financial support for the development of the project, the Graduate Program in Computation Engineering and Systems (PECS) of UEMA, the Foundation for Support of Research and Scientific and Technological Development of Maranhão (FAPEMA), the Measurement Telecommunication Laboratory of IFPB, João Pessoa Campus, for the availability of measuring equipment, and the Nacional Grafite Company for the samples provided for testing, in the execution of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H.B.C., first author, carrying out the experiments and writing the main text, E.C.C.S., analysed the results, P F.S.J., conceived and conducted the experiments, G.M.F., support for carrying out experiments, K.C.R.M., T.C.A., W.P.M., M.A.M., R.S.G., L.M.S.F., T.C.P., (B) A.S.R., (C) A.M.Cruz, acted as consultants for the Project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvalho, P.H.B., Santana, E.E.C., Barros Filho, A.K.D. et al. Electromagnetic textile absorber applied to 4G and 5G bands. Sci Rep 15, 18768 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03490-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03490-x