Abstract

The impact of prolonged treatment delays on the survival outcomes of patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) remains controversial. Patients were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The association between diagnosis-to-treatment interval (DTI) and survival was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models and competing risk regression.4700 (6.1%) experienced treatment delays and 28,934 (37.8%) died due to cancer-specific causes. Treatment delays were associated with a worse overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) of patients with cancer in the lip/oral cavity (OS: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.16, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08–1.24; CSS: aHR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.06–1.24), oropharynx (OS: aHR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.12–1.28; CSS: aHR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.10–1.28), and larynx (OS: aHR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.13–1.30; CSS: aHR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.33). However, treatment delay did not find significance on OS and CSS in patients with cancers of the hypopharynx, nasopharynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, or salivary glands at the time cutoff of 2 months for delayed treatment. Prolonged treatment delays were associated with an increased risk of mortality in patients with lip/oral cavity, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers, and should be focused on in order to improve patient prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2020, head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) ranked seventh in prevalence among malignant tumors worldwide1. In the US, HNSCC accounts for 3.4% of malignancies, with 15,400 deaths expected in 2023, increasing slightly from 3.3% of malignancies and 11,260 deaths in 20092,3,4. HNSCC involves malignancies originating from anatomic subsites, including the lip/oral cavity (OC), oropharynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx, larynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, and salivary glands3,5. HNSCC is a relatively locally advanced and fast-growing disease compared with other tumors6. However, the waiting time for treatment increased in this population between 2004 and 20197. Previous studies showed that delays in treatment may affect survival outcomes. Thus, the impact of treatment delay on survival is an aspect of concern.

The diagnosis-to-treatment interval (DTI) is defined as the interval from the final diagnosis to the start of treatment8,9. Delays in treatment are common and are increasing in HNSCC10,11. While several studies demonstrated no association between DTI and survival in patients with HNSCC12,13,14,15,16,17,18, others reported that prolonged DTI increased the probability of all-cause mortality9,10,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. The prognosis of patients with cancer is influenced by several factors owing to tumor heterogeneity. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) may accurately predict the prognosis of patients with HSCC28,29. However, these results remain controversial, and few studies have investigated CSS in patients with HNSCC. A large cohort and long-term follow-up study is needed to confirm the association between DTI and survival in patients with HNSCC.

Importantly, many of the studied cohorts included only some of the tumor types, and it has been difficult to draw consistent conclusions. This study included tumors from seven sites and examined the effects of treatment delays on overall survival (OS) and CSS rates of patients with HNSCC.

Materials and methods

Data source

Data from patients diagnosed with HNSCC were collected between 2000 and 2015 from 17 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database (SEER) registries. The patients were followed up until November 2022. In this retrospective observational study, we evaluated seven cancers diagnosed as HNSCCs (OC, oropharynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx, larynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, and salivary glands)5,9,27. Patients with HNSCC were defined using malignant histology and subsite codes for head and neck cancers (Supplementary Table 1). This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting Guidelines for cohort studies30. This study did not require approval by our institutional review board, as the SEER program database is available to the public for research purposes and no identifying information was collected regarding any patient.

Patient and variables

We retrospectively identified patients diagnosed with HNSCC between 2000 and 2015. The selection process is shown in Fig. 1. The demographic parameters considered included age at diagnosis, sex, race, marital status, year of diagnosis, site, stage, grade, median income, rural–urban status, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, examined nodes, and positive nodes. The cancer stage was categorized according to the SEER historic stage A codes and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging definitions as localized, regional, distant, and other5. The AJCC TNM stages were also considered in the subgroups. Patients were included in the study if their primary cancer was HNSCC. We excluded patients who were < 18 or > 85 years of age, diagnosed with multiple cancers, with unknown cancer stage, with unknown surgery, with unknown radiation, missing household income and county information, and with unknown CSS. Patients with treatment delays > 6 months and those who died within 30 days after diagnosis due to immortal time bias were also excluded30,31.

Definition of DTI and statistical analyses

DTI was defined as a time from diagnosis to first treatment of > 2 months, based on tumor features and prior literature10,19,20,32. Timely (0–2 months) and delayed (3–6 months) treatment groups were categorized according to the timing of DTI. Data were analyzed using Free Statistics software version 1.8 (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation). Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical data. The Kaplan–Meier (K–M) and cumulative incidence function (CIF) curves were plotted. Cox regression analysis was used to assess OS. Fine–Gray competing risk regression analysis was used to assess CSS. The multivariate risk model was built using a forward selection procedure with variables with two-sided P < 0.05, which was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

In our study, among 164,080 patients with HNSCC, 76,487 were analyzed (Fig. 1). The DTI composition of the cohort was 93.9% with timely treatment and 6.1% with delayed treatment. The median age was 60 years, and more than two-thirds (n = 58,325, 76.3%) of the patients were male. Whites (n = 62,988, 82.4%) constituted most of the cases. The most frequent subsites were the OC (n = 20,027, 26.2%), the oropharynx (n = 25,738, 33.7%), and the larynx (n = 20,461, 26.8%). The most common stages were regional (44.2%) diseases, followed by other (23.5%), and localized (20.7%) diseases. Most of the patients received surgery (52.6%) and radiation (76.0%), and less than half of them elected chemotherapy (47.0%) as the first-line treatment. In total, cancer-specific death (CSD) and cause-other death (COD) occurred in 28,934/76,487 (37.8%) and 16,149/76,487 (21.1%) patients with HNSCC, respectively. The median follow-up times were 86 months (entire cohort), 91 months (timely treatment group), and 37 months (delayed treatment group). By November 2022, 41.1% of patients were still living, with a higher survival rate among the timely treatment group and more deaths due to the primary tumor among patients in the delayed treatment group (Table 1).

Prevalence and delayed treatment

The proportion of patients receiving delayed treatment increased slightly. Similarly, an increasing proportion of cases with treatment delays were observed in cancers of OC, oropharynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx, larynx (Supplementary Fig. 1). Univariate Cox and competing risk regression analyses were conducted by selecting all variables listed (Supplementary Table 2). In multivariable Cox analysis, delayed treatment was associated with a higher risk of death (adjusted HR [aHR] = 1.18; 95% CI 1.14–1.23; P < 0.001, Supplementary Table 3). Given the causes of death for this patient population, we used competing risk models to estimate the CSS, in which delayed treatment was associated with an increased hazard of death (aHR = 1.16; 95% CI 1.12–1.22; P < 0.001, Supplementary Table 3).

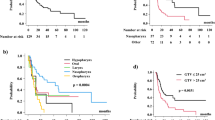

We further assessed which tumor subsites affected survival. Treatment delay was associated with worse OS in OC, oropharynx, and larynx cancers in univariate and multivariable analysis (OC: aHR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.24; oropharynx: aHR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.12–1.28; larynx, aHR = 1.21; 95% CI 1.13–1.30). We observed similar results in CSS (aHRs, 95% CI OC: 1.15, 1.06–1.24, oropharynx: 1.19, 1.10–1.28, and larynx cancers: 1.21, 1.10–1.33), respectively (Table 2). In subgroup analysis according to the confounders of age, sex, race, surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy showed that delayed treatment was associated with increased risk of death in most subgroups, with HRs > 1.00 in OC, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers (Supplementary Fig. 2). We observed similar results between delayed treatment and CSS (Fig. 2) but not between treatment delay and overall survival (OS) or cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients diagnosed with hypopharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, nasal cavity and sinuses, or salivary gland cancer (Supplementary Table 4).

K–M survival and CIF curves compare the survival of patients with different types of tumors showing a survival benefit for OC, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers with timely treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3, Fig. 3). However, DTI did not significantly impact survival in patients with delayed treatment in hypopharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, nasal cavity and sinuses, and salivary gland cancers (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5).

Impact of delayed treatment in tumor subsite and stage

Based on the results of the subsite analysis, we further analyzed the association between treatment delay and patient survival at different stages. After adjusting for confounders, we observed associations between DTI and survival patterns in patients with stage III–IV oropharyngeal cancer (OS: aHR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.17–1.37, P < 0.001; CSS: aHR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.08–1.30, P < 0.001) and stage I–II laryngeal cancer (OS: aHR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.14–1.53, P < 0.001; CSS: aHR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.20–1.85, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 5). We observed no significant associations between treatment delay and survival patterns in patients with OC, early-stage oropharynx, advanced larynx, hypopharynx, nasopharynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, or salivary gland cancers (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

The association between DTI and survival of HNSCC remains controversial (Supplementary literature review) in previous studies, and most of these focus on OS or had smaller sample sizes and might overestimate the relationship. The current study focused on overall trends in DTI of HNSCC, and the association of DTI with OS and CSS. The key findings are as follows: First, in this population-based cohort, we found that 6.1% of patients with HNSCC experienced treatment delays exceeding 2 months. Second, CSD occurred in 37.8% of patients with HNSCC, with a higher rate in the delayed treatment group compared with the timely treatment group. Third, the survival of patients with delayed treatment was worse than that of patients with timely treatment for OC, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers. Fourth, we observed no significant difference between prolonged DTI and survival among patients with HNSCC at other anatomical sites, including the hypopharynx, nasopharynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, and salivary glands at the time cutoff of 2 months for delayed treatment.

DTI is one phase of time-to-treatment. The association between treatment delay and poor outcomes has not been consistently reported in recent systematic reviews of patients with HNSCC8,33. Therefore, we sought to report the results from 17 registries in the SEER database of patients with HNSCC, including 7 cancer subsites, as well as to identify cancer subsites for treatment delay to facilitate future intervention. Previous studies reported that 20–50% of patients experience treatment delay depending on the treatment delay time 20,24,34. Based on our threshold of 2 months, 4700 (6.1%) of our patients experienced treatment delay. This lower proportion in our study compared to previous reports may be due to the higher proportion of younger patients who were treated actively; however, further studies are needed to confirm this point. The median age of the population reported in prior study was similar to the population included here, and the location of the tumors was predominantly OC35. Among these patients in our study, the largest proportion had oropharyngeal tumors. This may be associated with the categorization of the included ICD codes. The proportion of all tumors receiving delayed treatment increased slightly in 15 years. Consistent with previous results32, we also found that economic income was associated with treatment delay, which was more pronounced in middle- and high-income patients. Previous studies have reported CSD in up to 82% of patients with head and neck carcinoma29,36,37. COD influences long-term survival prognosis; therefore, it should be considered when assessing survival outcomes 28,38. Few studies have focused on the relationship between delayed treatment and CSS. In head and neck cancer, the causes of death in 34.5% of patients were attributable to causes other than primary cancer39. The results of the current study show that CSD occurred in 37.8% of patients with HNSCC with at least 7 years of follow-up. And the proportion of CSD was slightly higher in the delayed treatment group.

The controversy surrounding the impact of DTI on survival rates has led to discussions highlighting its varying relevance among different forms of head and neck cancer. Retrospective studies have shown no significant differences between treatment initiation and survival in patients with HNSCC12,14,15,18. This can be partly explained by the short duration of the DTI. Timely treatment may be especially important for patients with oral, tongue, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx cancers, and a delay time of 2 months was the optimal threshold-based tumor doubling time in prior studies10,20,40. New research findings have indicated lower survival rates among patients diagnosed with cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and larynx if treatment is postponed21,22,25,27,41. These studies focused on the relationship between delayed treatment and OS. The number of positive nodes is also an index of prognosis in patients with surgically treated HNSCC42,43. In the present study, we incorporated this factor and observed CSS in 21.1% of patients with HNSCC. Moreover, multivariate analysis also showed the negative impact of treatment delays on both OS and CSS. We further analyzed the association between treatment delay and survival in patients with oral cavity, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers. Subgroup analyses revealed a significant impact of delayed treatment on CSS in patients, who were younger, white, undergoing surgery, and radiation therapy. Prior results also supported our conclusion that the effect of treatment delay was relatively significant in younger or surgical populations, but this difference was not significant24. Previous studies have found that treatment delays with radiotherapy also affect survival in patients with HNSCC, a finding that is consistent with our study, which however further analyzed CSS44.

To study the relationship between treatment interval and survival more precisely, we focused on tumor-specific survival. We found that prolonged DTI significantly affected the OS and CSS of patients with OC and oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancers but not in those with nasopharyngeal cancer. A previous study found that a longer treatment delay was a significant prognostic factor for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma45. It had also been suggested that the treatment of nasopharyngeal cancer was not affected by the delayed treatment time and was more dependent on the subsequent treatment modalities46. Consistent with our findings, earlier studies also found no significant difference between DTI and survival in hypopharynx, nasal cavity and sinuses, and salivary gland cancers13,47,48. In the current study, we also focused on the relationship between DTI and survival at different stages of OC, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers. Patients with advanced oropharyngeal and early laryngeal cancers had worse survival rates after delayed treatment. A previous study from Italy showed a stronger association between delayed treatment and poor prognosis for laryngeal cancer24. Earlier surgery or radiotherapy alone might significantly improve the prognosis in early-stage disease, and delayed treatment may increase the risk of tumor progression49,50. Advanced laryngeal cancer was treated with a combination of modalities that might have reduced the reliance on time delayed for treatment. Previous evidence also indicates that the time to treatment initiation influences overall survival in HPV + oropharynx cancer7,23. Our study also revealed that delayed treatment affects survival in oropharyngeal cancer. The limitation is that the HPV status of patients in the database cannot be determined. Previous literature research revealed that CSS is affected by anatomical site, especially for oropharyngeal tumors38. We also found that the specific survival of not only oropharyngeal tumors was affected by DTI, but also oral and laryngeal tumors. These relevant factors require further exploration. Prolonged intervals of > 2 months were not associated with cancers at other stages. This finding is contrary to those of earlier reports of prolonged treatment in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma51. However, this mechanism requires further investigation. Some factors, including the potential causes of increased wait times and the waiting time between diagnosis and treatment, and the survival of this group of patients should be identified and improved.

This study has few limitations. First, because this investigation relied on retrospective data, the potential biases introduced by the accuracy of the cancer registry and patient medical records pertaining to HNSCC must be considered. Second, treatment after tumor recurrence is difficult to obtain and may affect survival. Third, the absence of these two variables outweighed the time to treatment initiation with respect to survival52. Fourth, DTIs in the database were recorded in months rather than based on days, and more detailed cut-off values were difficult to identify. In spite of these limitations, this study could still be used as a clinical reference.

Conclusion

The results of our study highlight that 6.1% of patients with HNSCC experience treatment delays. A reduced delay from diagnosis to treatment may help to improve survival in lip/oral cavity, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers, especially in advanced oropharyngeal and early laryngeal cancers.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are available at www.seer.cancer.gov.

Abbreviations

- HNSCC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell cancer

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

- DTI:

-

Diagnosis-to-treatment interval

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- CSS:

-

Cancer-specific survival

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249 (2021).

Jemal, A. et al. Cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 59(4), 225–249 (2009).

Bean, M. B. et al. Small cell and squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: Comparing incidence and survival trends based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data. Oncologist 24(12), 1562–1569 (2019).

Siegel, R. L. et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 73(1), 17–48 (2023).

Hardy, S. J. et al. Stroke death in patients receiving radiation for head and neck cancer in the modern era. Front. Oncol. 13, 1111764 (2023).

Jensen, A. R., Nellemann, H. M. & Overgaard, J. Tumor progression in waiting time for radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 84(1), 5–10 (2007).

Tasoulas, J. et al. Time to treatment patterns of head and neck cancer patients before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Oral Oncol. 146, 106535 (2023).

Schutte, H. W. et al. Impact of time to diagnosis and treatment in head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 162(4), 446–457 (2020).

Schoonbeek, R. C. et al. Determinants of delay and association with outcome in head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 47(8), 1816–1827 (2021).

Murphy, C. T. et al. Survival impact of increasing time to treatment initiation for patients with head and neck cancer in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 34(2), 169–178 (2016).

Murphy, C. T. et al. Increasing time to treatment initiation for head and neck cancer: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Cancer 121(8), 1204–1213 (2015).

Jensen, J. S. et al. Impact of time to treatment initiation for patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: A population-based, retrospective study. Acta Oncol. 60(4), 491–496 (2021).

Morse, E. et al. Hypopharyngeal cancer treatment delays: Benchmarks and survival association. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 160(2), 267–276 (2019).

Richardson, P. A. et al. Treatment patterns in veterans with laryngeal and oropharyngeal cancer and impact on survival. Laryngoscope Investig Oto. 3(4), 275–282 (2018).

Morse, E. et al. National treatment times in oropharyngeal cancer treated with primary radiation or chemoradiation. Oral Oncol. 82, 122–130 (2018).

Fujiwara, R. J. T. et al. Treatment delays in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma and association with survival: Treatment delays in oral cavity cancer. Head Neck 39(4), 639–646 (2017).

van Harten, M. C. et al. The association of treatment delay and prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients in a Dutch comprehensive cancer center. Oral Oncol. 50(4), 282–290 (2014).

Caudell, J. J., Locher, J. L. & Bonner, J. A. Diagnosis-to-treatment interval and control of locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 137(3), 282–285 (2011).

Rygalski, C. J. et al. Time to surgery and survival in head and neck cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28(2), 877–885 (2021).

Liao, D. Z. et al. Association of delayed time to treatment initiation with overall survival and recurrence among patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in an underserved urban population. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145(11), 1001 (2019).

Goel, A. N. et al. Survival impact of treatment delays in surgically managed oropharyngeal cancer and the role of human papillomavirus status. Head Neck 41(6), 1756–1769 (2019).

Morse, E. et al. Treatment delays in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A national cancer database analysis. Laryngoscope 128(12), 2751–2758 (2018).

Grønhøj, C. et al. Impact of time to treatment initiation in patients with human papillomavirus-positive and -negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Oncol. 30(6), 375–381 (2018).

Polesel, J. et al. The impact of time to treatment initiation on survival from head and neck cancer in north-eastern Italy. Oral Oncol. 67, 175–182 (2017).

Liao, C.-T. et al. Association between the diagnosis-to-treatment interval and overall survival in Taiwanese patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 72, 226–234 (2017).

Sharma, S. et al. Clinical impact of prolonged diagnosis to treatment interval (DTI) among patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 56, 17–24 (2016).

van Harten, M. C. et al. Determinants of treatment waiting times for head and neck cancer in the Netherlands and their relation to survival. Oral Oncol. 51(3), 272–278 (2015).

Davies, L. et al. Key points for clinicians about the SEER oral cancer survival calculator. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 149(11), 1042 (2023).

Tang, X. et al. A novel prognostic model predicting the long-term cancer-specific survival for patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 20(1), 1095 (2020).

Min, Y. et al. Survival outcomes following treatment delays among patients with early-stage female cancers: a nationwide study. J Transl Med. 20(1), 560 (2022).

Wagle, N. S. et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in treatment delay among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21(5), 1281-1292.e10 (2023).

Kompelli, A. R., Li, H. & Neskey, D. M. Impact of delay in treatment initiation on overall survival in laryngeal cancers. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 160(4), 651–657 (2019).

Lauritzen, B. B. et al. Impact of delay in diagnosis and treatment-initiation on disease stage and survival in oral cavity cancer: A systematic review. Acta Oncol. 60(9), 1083–1090 (2021).

Shaikh, N. et al. Factors associated with a prolonged diagnosis-to-treatment interval in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 166(6), 1092–1098 (2022).

Frank, M. H. et al. Differences in the association of time to treatment initiation and survival according to various head and neck cancer sites in a nationwide cohort. Radiother. Oncol. 192, 110107 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Nomogram predicting cancer-specific death in parotid carcinoma: a competing risk analysis. Front. Oncol. 11, 698870 (2021).

Hu, M. et al. A competing risk nomogram for predicting cancer-specific death of patients with maxillary sinus carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 698955 (2021).

Brouwer, A. F. et al. Time-varying survival effects for squamous cell carcinomas at oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck sites in the United States, 1973–2015. Cancer 126(23), 5137–5146 (2020).

Shen, W., Sakamoto, N. & Yang, L. Cancer-specific mortality and competing mortality in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A competing risk analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22(1), 264–271 (2015).

Waaijer, A. et al. Waiting times for radiotherapy: consequences of volume increase for the TCP in oropharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother. Oncol. 66(3), 271–276 (2003).

Tsai, W.-C. et al. Influence of time interval from diagnosis to treatment on survival for oral cavity cancer: A nationwide cohort study. PLOS ONE 12(4), e0175148 (2017).

Qian, K. et al. The number and ratio of positive lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors for patients with major salivary gland cancer: Results from the surveillance, epidemiology, and End Results dataset. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 45(6), 1025–1032 (2019).

Roberts, T. J. et al. Number of positive nodes is superior to the lymph node ratio and American Joint Committee on Cancer N staging for the prognosis of surgically treated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer 122(9), 1388–1397 (2016).

Fortin, A. et al. Effect of treatment delay on outcome of patients with early-stage head-and-neck carcinoma receiving radical radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 52(4), 929–936 (2002).

Chen, P.-C. et al. The impact of time factors on overall survival in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A population-based study. Radiat. Oncol. (Lond. Engl.) 11, 62 (2016).

Wei, X. et al. Association between time from diagnosis to treatment and survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A population-based cohort study. Curr. Probl. Cancer 48, 101060 (2024).

Goel, A. N. et al. Treatment delays in surgically managed sinonasal cancer and association with survival. Laryngoscope 130(1), 2–11 (2020).

Morse, E. et al. Treatment times in salivary gland cancer: National patterns and association with survival. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 159(2), 283–292 (2018).

Obid, R., Redlich, M. & Tomeh, C. The treatment of laryngeal cancer. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. North Am. 31(1), 1–11 (2019).

Xiao, R. et al. Increased pathologic upstaging with rising time to treatment initiation for head and neck cancer: A mechanism for increased mortality. Cancer 124(7), 1400–1414 (2018).

Metzger, K. et al. Treatment delay in early-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma and its relation to survival. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 49(6), 462–467 (2021).

Ho, A. S. et al. Quantitative survival impact of composite treatment delays in head and neck cancer. Cancer 124(15), 3154–3162 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (National Cancer Institute) for developing the SEER database. We thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (No. 2022JQ-960).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH and ML conceive and design the study. DH, YY and RL are responsible for table and figure. YY and RL participated in the data analysis and performed the statistical analysis. DH, YY, and ML helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The data analyzed and used in this study was obtained from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database in accordance with the SEER data use agreement. Therefore, this study did not require approval of ethical board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, D., Yang, Y., Li, R. et al. Effect of delayed treatment on survival of patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer. Sci Rep 15, 18366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03500-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03500-y