Abstract

Myelomeningocele (MMC) and myeloschisis (MS) are considered as the most severe forms of spina bifida aperta characterized by incomplete closure of the neural tube during the first trimester of pregnancy. Open maternal-fetal surgery has been identified as a promising alternative for the repair of MMC/MS. The main goal of this study was the isolation and characterization of stem cells derived from MMC/MS amniotic fluid samples. Human amniotic fluid samples were obtained from pregnant women who underwent surgery for fetal spina bifida repair. We applied fluorescence activated-cell sorting (FACS) to immunoselect stem cells from heterogeneous populations of amniocytes based on cKIT (CD117) expression. The cKIT+ amniocytes were then contrasted with cKIT− and unselected amniocytes in order to characterize the phenotype of these cells. cKIT-expressing amniocytes exhibited spindle-shape morphology, while amniocytes negative for cKIT were round-shaped. qRT-PCR analysis revealed significant upregulation of mean mRNA levels of KIT and CD90 genes and downregulation of CK8 gene in cKIT-expressing amniocytes, compared to the negative and unsorted cells. The expression of pluripotency antigens was comparable in sorted cKIT+ and cKIT− amniocytes and in unselected cells. Our results are of pivotal importance for the future application of amniotic fluid derived stem cells in spina bidfida repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The amniotic fluid is a clear, yellow liquid surrounding the human fetus in the amniotic sac1. During embryogenesis, it acts as a water cushion protecting the developing fetus from mechanical injuries and trauma2,3. The volume and composition of amniotic fluid fluctuate significantly during ongoing gestation, and in the late embryogenesis, amniotic fluid is composed mainly of fetal urine and gastrointestinal secretions1,4,5,6.

In healthy, physiological pregnancies amniotic fluid is a source of heterogeneous cell types, the majority of which are terminally differentiated and exhibit limited proliferation and differentiation potentials. Early research studies suggested that adherent cells of the human amniotic fluid can be classified into 3 different groups: amniocytes or amniotic fluid specific cells, epithelioid cells, and fibroblastic cells7,8. In 2003, Prusa et al., discovered the presence of OCT4+ cells (0.1–0.5%) in the early mid trimester amniotic fluid9. OCT4 is a nuclear transcription factor responsible for the maintaining of differentiation potential and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (ESCs)10,11,12,13. In 2007, De Coppi et al., developed a protocol for the isolation of stem cells from amniotic fluid based on the expression of cell surface antigen cKIT (CD117) using magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS)14. Some researchers attributed pluripotency to these cKIT-expressing amniotic fluid stem cells (AFSCs), as they exhibit high in vitro proliferation potential15, have the ability to differentiate into cells of mesoderm-derived (fat, cartilage, muscle) and non-mesodermal cell lineages (endothelial, hepatic, neuronal) in vitro2,14, as well as do not form teratomas following in vivo injection14. Therefore, amniotic fluid represents an attractive source of stem cells with potential application in distinct aspects of medicine. However, recently the pluripotency of AFSCs has been questioned16.

Congenital malformations myelomemingocele (MMC) and myeloschisis (MS) belong to the open spina bifida defects (spina bifida aperta, in short SBA) and are considered as the most severe and most frequent forms of spina bifida with the prevalence of about 1 per 3000 live births worldwide17,18,19. MMC is characterized by the incomplete closure of vertebral arches around spinal cord during the first trimester of pregnancy. As a consequence, the spine and meninges around spine protrude beyond the level of skin forming a cerebrospinal fluid filled cystic sac on the back of the fetus20. In the MS, the architecture of the malformation is analogous, but without the sac. Patients affected with MMC or MS suffer from very severe neurological deficits, including the paralysis in the lower extremities, bladder and bowel dysfunction, skeletal deformities, as well as hydrocephalus and Chiari II malformation21.

Nowadays, open maternal-fetal surgery has been identified as a promising alternative for the repair of MMC/MS. Importantly, fetal repair of MMC/MS has been shown to minimize the neural damage consequently leading to improved clinical outcome in affected individuals. However, there is a tremendous need to further improve and develop the clinical treatment modalities. A promising and pivotal option for the in utero management of MMC/MS is the application of stem cell therapy. Scientists have already applied stem cells derived from various sources in animal pre-clinical experimental models for spina bifida. For instance, neural stem cells22, amniotic fluid stem cells23,24, bone marrow stem cells25,26, umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells27,28, as well as placental stem cells29 have been extensively investigated for their ability to cover and regenerate the damaged spinal cord in spina bifida animal models.

Interestingly, the incomplete closure of the spinal cord in the MMC/MS may significantly affect the cellular composition of amniotic fluid. It has been suggested that amniotic fluid from lamb foetuses with open neural tube defect contains neural progenitor cells expressing both Nestin and SOX230. Interestingly, these cells were not present in the corresponding healthy lamb fetuses. Similarly, the amniotic fluid derived from fetal rats with retinoic acid induced MMC contains neuro-epithelial cells which were not present in the healthy control rat fetuses31. However, most of these studies come from animal models, and little is known about the cellular composition and the presence of stem cells in the amniotic fluid derived from human fetuses affected with an open spina bifida defect.

Therefore, the main goal of this study was the in depth characterization of stem cells derived from human amniotic fluid of pregnancies with SBA. These AFSCs could be potentially applied for the development of complex, tissue-engineered skin/cartilage autologous or allogenic substitutes that would revolutionize the in utero treatment of open spina bifida defects.

Results

Isolation of cKit+ cells from amniotic fluid samples obtained from pregnancies with spina bifida aperta

Human amniocytes were isolated and cultured from amniotic fluid samples (n = 17) obtained from pregnancies diagnosed with SBA according to the scheme presented in Fig. 1a. Five to six days after isolation, small colonies constituting 5 to 10 cells were observed on the cell culture dish. During in vitro culture, these colonies expanded and exhibited differences in the cell morphology (Fig. 1b–e). As depicted in Fig. 1, amniocytes with a round shape (Fig. 1b–c; white arrows) as well as cells with a spindle shaped morphology could be distinguished (Fig. 1d–e; blue arrow).

Isolation of amniocytes from amniotic fluid of SBA pregnancies. (a) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure. Amniotic fluid was obtained during prenatal operations for spina bifida aperta defects (MMC/MS). Amniotic fluid samples were centrifuged and cells were plated on plastic cell culture dishes. After expansion, amniocytes were stained for cKIT and sorted using FACS in order to obtain cKIT+ and cKIT- cell fractions. Sorted cells were expanded in vitro and analysed using qRT-PCR and flow cytometry. Created with BioRender.com. (b–e) Morphology of amniocytes derived from pregnancies diagnosed with SBA at passage 0 (P0), before FACS. Please note the existence of (b, b’, c, c’) round shaped cells (white arrows) as well as (d, d’, e, e’) spindle-shape cells (blue arrows). Insets represent higher magnifications. Scale bars: 500 μm.

Previous studies have shown that the amniotic fluid contains a population of stem cells that could be detected using the cell surface antigen cKIT14. Accordingly, we used cKIT as a marker to select stem cells from the heterogeneous population of our SBA-derived amniocytes.

Amniocytes, isolated from 17 biologically independent donors, were stained at passage 0 (P0) for cKIT and sorted by FACS. The list of all donors used in the study is presented in Table 1. During the sorting, we excluded doublets (Fig. 2a–b) as well as dead cells (Fig. 2c). In order to eliminate background signals, we used a PE isotype (negative) control (Fig. 2d). On average 9.2 ± 7.4% of the amniocytes expressed cKIT (Fig. 2e). The purity of cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes after sorting is presented in Fig. 2f and g. Interestingly, the percentage of cKIT positive cells varied significantly between different donors. The heatmap in Fig. 2h represents the percentage of cKit-expressing amniocytes in individual donors. Importantly, in the heatmap, the donors are listed according to the level of MMC/MS defect to facilitate correlation between lesion position and the percentage of cKIT+ cells in the amniotic fluid.

Separation of cKIT+ amniocytes derived from amniotic fluid of SBA pregnancies by FACS. (a–d) The hierarchical gating strategy involved (a) selection of population of interests and exclusion of cell debris, (b) exclusion of cell doublets, and (c) elimination of dead cells using ZombieAqua staining. (d) Isotype control was used to detect the background signal. (e–g) cKIT was used to sort out stem cells from heterogeneous population of SBA-derived amniocytes. 9.15 ± 7.40% of amniocytes (n = 17) were positive for cKIT. The purity of cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes after sorting is presented in (f) and (g), respectively. (h) Heatmap representing the percentage of cKIT-expressing amniocytes in individual donors (n = 17). The donors were listed according to the level of MMC/MS lesion (thoracic, lumbar, or sacral). Increased percentages are shaded in red while decreased percentages are shaded in green. (i–j) Morphology of cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes after sorting. Please note and spindle-shaped phenotype of cKIT+ amniocytes (white arrows) and the presence of both spindle-shaped (white arrows) and round cells (blue arrows) in cKIT- amniocytes. Scale bars: 500 μm.

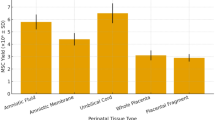

Moreover, we conducted a comprehensive analysis to correlate the level of MMC/MS lesion with both defect size and the percentage of cKIT+ cells present in the amniotic fluid (Suppl. Figure 1a, b). Our findings indicate that defects situated in the thoracic region (3167 ± 2807mm2) exhibit larger sizes when compared to defects in the lumbar (1007 ± 560.6mm3, p ≤ 0.05) and sacral (661 ± 218.7mm3, p ≤ 0.05) regions of the fetus’s back (Suppl. Figure 1a). Interestingly, no significant size disparity was observed between defects located in the sacral and lumbar regions (p˃0.05). Additionally, our study revealed a noteworthy trend, suggesting that higher, thoracic level defects (12.2 ± 3.9%) tend to be associated with a higher percentage of cKIT-expressing cells in the amniotic fluid in comparison to defects localized in the lumbar (8.6 ± 6.7%) and sacral (8.4 ± 9.5%) regions (Suppl. Figure 1b). However, it is important to note that these observed differences did not reach statistical significance in our analysis (p > 0.05). Our study also showed that the gender of fetus does not influence the percentage of cKIT+ cells in the amniotic fluid (Suppl. Figure 1c). Accordingly, we detected that in the amniotic fluid of male and female fetuses, the percentage of cKIT+ cells accounts for 7.4 ± 4.8% and 11.6 ± 9.9%, respectively (p > 0.05).

cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes were expanded in 2D culture after sorting and used for further experiments. Interestingly, these two sorted cell groups exhibited distinct cell morphologies when cultured in vitro. The cKIT+ amniocytes displayed a fibroblast-like, elongated, spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 2i, white arrows). By contrast, in the population of cKIT- amniocytes both spindle-shaped (white arrows) and round-shaped (blue arrows) cells were present (Fig. 2j).

Characterization of cKIT+ amniocytes by qRT-PCR

Previously published data suggest that cKIT+ amniocytes derived from mid-trimester amniotic fluid of healthy pregnancies express mesenchymal (CD90, CD44, CD105) as well as pluripotent stem cell markers (NANOG, OCT4, KLF4)9,14. To evaluate the phenotype of SBA derived cKIT+ amniocytes, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of selected genes. The mean mRNA levels of CD90 were 2.5 times lower in cKIT- and 2.6 lower in unsorted amniocytes, than in cKIT+ cells (Fig. 3a, p ≤ 0.05). Additionally, we detected the comparable mRNA expression of CD90 in cKIT+ amniocytes and Adipose Derived Stem cells (ASCs, p > 0.05) (Fig. 3a).

Characterization of SBA-derived amniocytes by qRT-PCR. (a–c) Relative mRNA expression of mesenchymal stem cell genes: (a) CD90, (b) CD105, and (c) CD44 in cKIT+, cKIT-, and unsorted amniocytes. Please note the mean mRNA level of CD90 was 2.5 times lower in cKIT- and 2.6 lower in unsorted amniocytes, compared to the cKIT+ cells. (d) Relative mRNA expression of epithelial gene CK8 in cKIT+, cKIT-, and unsorted amniocytes. The mean mRNA expression of CK8 was significantly upregulated in cKIT- and usorted amniocytes, in comparison to the cKIT+ cells. (e–h) Relative mRNA expression of pluripotent stem cell genes: (e) KIT, (f) KLF4, (g) NANOG and (h) OCT4 in cKIT+, cKIT-, and unsorted amniocytes. cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes showed downregulation of KIT gene, in comparison to the cKIT+ cells. Please note that KLF4, NANOG and OCT4 genes were expressed on comparable level in analyzed amniocytes groups. Donor-matched cKIT+, cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes are derived from eight donors (n = 8). ASCs were used as a control (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used to calculate significance. Stars indicate statistical significance, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001, ns p > 0.05.

Notably, both CD105 and CD44 mRNA were not reduced in cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes, compared to the cKIT+ amniocytes (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3b-c). Of note, mean CD105 and CD44 mRNA levels were 9 times (p > 0.05) and 4.5 times (p > 0.05) higher in ASCs in comparison to the cKIT+ amniocytes (Fig. 3b-c).

The mean CK8 mRNA levels were 12.2 times higher in cKIT- amniocytes (p ≤ 0.01), and 10.4 higher in unsorted amniocytes (p ≤ 0.05) than those observed in cKIT+ cells (Fig. 3d). As expected, the expression of CK8 gene in cKIT+ and ASCs was comparable (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3d).

The mean mRNA expression of KIT was 4.7 times lower in cKIT- cells (p ≤ 0.01), and 4.7 times lower in unsorted amniocytes (p ≤ 0.01) than in cKIT+ cells (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, the expression of KIT gene in cKIT+ amniocytes and ASCs was comparable (Fig. 3e, p > 0.05).

We have not observed the reduction of mean mRNA levels of pluripotency genes, namely KLF4, NANOG, and OCT4, in cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes, compared to the cKIT-expressing cells (Fig. 3f-h, p > 0.05). The mean mRNA levels of KLF4, NANOG, and OCT4 in cKIT+ amniocytes and ASCs were similar (Fig. 3f-h, p > 0.05).

Characterization of cKIT+ amniocytes by flow cytometry

To better characterize the phenotype of the SBA derived cKIT+ amniocytes, the expression of various mesenchymal and pluripotent stem cell markers were analysed in the cultured cells at P2-P4 on protein level by flow cytometry. Subsequently, the phenotype of cKIT+ amniocytes was compared to the phenotype of cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes. Human ASCs were used as a control. The mean percentages of positive cells in each group are presented on graphs (Fig. 4a-h).

Characterization of SBA-derived amniocytes by flow cytometry. (a–c) Mean percentage of cells expressing mesenchymal stem cell antigens: (a) CD90, (b) CD105, and (c) CD44 in cKIT+, cKIT−, and usorted amniocytes. The expression of CD90 was upregulated in cKIT+ amniocytes in comparison to the unsorted cells. Please note that all amniocytes subpopulations exhibited comparable expression of CD105 and CD44. (d) Mean percentage of cKIT+, cKIT−, and unsorted amniocytes expressing epithelial marker PanCK. Comparable expression of PanCK was detected in all analyzed amniocytes subgroups. (e–h) Mean percentage of cKIT+, cKIT−, and unsorted amniocytes expressing pluripotency markers: (e) cKIT, (f) KLF4, (g) NANOG, and (h) OCT4. Please note the upregulated expression of cKIT in sorted cKIT+ amniocytes and low expression of this cell surface marker in cKIT− and unsorted cells. KLF4, NANOG, and OCT4 were expressed on similar level in all amniocytes subpopulations. Donor-matched cKIT+, cKIT− and unsorted amniocytes are derived from eight donors (n = 8). ASCs were used as a control (n = 2). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 8). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used to calculate significance. Stars indicate statistical significance, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001, ns p > 0.05.

Considering mesenchymal stem cell markers, cKIT+ amniocytes showed a high number of cells positive for CD90 and CD44, but a low number of CD105-expressing cells. In particular, 96.6 ± 5.3% of the cKIT+ amniocytes, 69.4 ± 28.1% of cKIT- (p > 0.05), and 62.6 ± 28.0% of unsorted amniocytes (p > 0.05) were positive for CD90 (Fig. 4a). Additionally, almost all human ASCs were positive for CD90 (96.8 ± 1.7%, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4a).

Surprisingly, we found very low number of cells expressing CD105 in all analyzed amniocytes groups (Fig. 4b). In particular, a subpopulation of 2.0 ± 2.2% of cKIT+, 2.1 ± 1.9 of cKIT- (p > 0.05), and 2.9 ± 4.8% of unsorted amniocytes (p > 0.05) was positive for CD105. By contrast, 17.5 ± 3.6% (p > 0.05) of ASCs showed expression of CD105.

The number of cells expressing CD44 was relatively high and comparable in all amniocytes groups and in ASCs (Fig. 4c, cKIT+: 96.8 ± 3.8%, cKIT-:96,4 ± 6.1% (p > 0.05), unsorted: 94.1 ± 2.5% (p > 0.05), ASCs: 99.95 ± 0.05% (p > 0.05).

The epithelial marker, Pan Cytokeratin (PanCK), was expressed in similar and moderate number of cells in all analyzed amniocytes subpopulation (Fig. 4d). The mean percentage of PanCK-expressing cells in cKIT+ amniocytes was 42.3 ± 36.2%, in cKIT- amniocytes was 54.1 ± 31.7% (p > 0.05), and in unsorted was 73.2 ± 24.9% (p > 0.05). Moreover, we detected a low fraction of ASCs expressing of PanCK (1.4 ± 0.2%, p > 0.05).

In addition, we found significantly higher portion of cells expressing cKIT in sorted cKIT+ amniocytes (27.8 ± 20.2%), in comparison to the negative (2.5 ± 4.6%, p ≤ 0.01) and unfractioned cells (1.1 ± 1.0%, p ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 4e). Not surprisingly, cKIT expression in ASCs was marginal (1.1 ± 0.3%, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4e).

Interestingly, KLF4 was expressed in nearly all ASCs (97.6 ± 0.5%, p > 0.05), while the expression of this marker was significantly reduced in the cKIT+ (11.35 ± 23.2%), cKIT- (4.3 ± 5.2%, p > 0.05), and in unsorted amniocytes (4.6 ± 6.2%, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4f).

NANOG and OCT4 were expressed on moderate number of cells in analyzed amniocytes subgroups, while the expression of these pluripotency markers was almost undetectable in ASCs (Fig. 4g-h). Approximately 1/3 of cKIT+ amniocytes were positive for NANOG (Fig. 4G). NANOG was also expressed in 25.9 ± 22.1% of cKIT- cells (p > 0.05), and in 19.5 ± 19.9% of unsorted cells (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4g). There was no significant difference in the NANOG expression between cKIT+ amniocytes and ASCs (0.5 ± 0.1%, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4g).

The mean percentage of cells positive for OCT4 in cKIT+ amniocytes was 71.5 ± 38.5% (Fig. 4h). The expression of this marker was also moderate in cKIT- (18.1 ± 23.7, p > 0.05) and in unsorted amniocytes (44.6 ± 35.2%, p > 0.05). As expected, there was almost no expression of OCT4 in ASCs (0.3 ± 0.4, p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4h).

Supplementary Fig. 3 summarizes the expression of all analyzed antigens in sorted cells of 8 individual donors; (-) refers to low expression (1–5%), (+/-) refer to moderate expression (6–50%), (+) indicates high expression (above 50%).

Chondrogenic differentiation of cKIT+ amniocytes

cKIT+ AFSCs were differentiated into chondrocytes in vitro. After 4 weeks in chondrogenic differentiation medium (containing TGFβ3), Alcian Blue (Fig. 5a-j) as well as Safranin O (Fig. 5k-t) histological stainings were performed to detect the presence of cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in differentiated cells.

Differentiation potential of SBA-derived cKIT+ AFSCs into chondrogenic lineage in vitro in a 2D system. (a–f) Alcian Blue staining of SBA-derived cKIT+, cKIT−, and unsorted amniotic fluid cells cultured in (a, c, e) expansion medium as well as (b, d, f) 4 weeks after induction with chondrogenic differentiation medium. After chondrogenic differentiation cKIT+ cells displayed blue-stained deposits of GAGs. By contrast, Alcian Blue stain was less intense in cKIT− and unsorted amniocytes. (g, h) ASCs and (i, j) human chondrocytes were used as a positive control. (k–t) Safranin O staining of SBA-derived cKIT+, cKIT−, and unsorted amniotic fluid cells cultured in (k, m, o) expansion medium as well as (l, n, p) 4 weeks after induction with chondrogenic differentiation medium. Safranin O staining was less pronounced in cKIT− and unsorted amniocytes as compared to the cKIT+ AFSCs following the chondrogenic induction. (q, r) ASCs and (s, t) human chondrocytes were used as a positive control. Insets represent macroscopic pictures of cells on culture plastic stained with Alcian Blue/Safranin O. Scale bars: 500 μm. (u–v) Quantification of (u) Alcian Blue and (v) Safranin O positively stained area in donor matched cKIT+ AFSCs, cKIT− amniocytes, unsorted amniocytes before and following chondrogenic induction. ASCs and chondrocytes were used as a control. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 2). Two-way Anova with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test was used to calculate significance. Stars indicate statistical significance, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001, ns p > 0.05.

As shown in Fig. 5, a monolayer of chondrogenically differentiated cKIT+ AFSCs demonstrated a strong positive Alcian Blue staining in vitro (Fig. 5b), suggesting an enhanced production of acidic mucopolysaccharides and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which were not detected in non-differentiated cKIT+ AFSCs cultured in expansion medium (Fig. 5a). Similarly, Safranin O staining, detecting sulfated proteoglycans, was the most intense in chondrogenically induced cKIT+ AFSCs suggesting an extensive production of cartilage matrix by those cells (Fig. 5k, l). By contrast, Safranin O and Alcian Blue stainings were less pronounced in cKIT- (Fig. 5c, d, m, n) and unfractioned (Fig. 5e, f, o, p) amniocytes indicating that these cells showed a reduced production of GAGs and are less potent than cKIT+ cells. ASCs (Fig. 5g, h, q, r) and human chondrocytes (Fig. 5i, j, s, t) were used as positive control showing extensive production of cartilage ECM following chondrogenic induction. Importantly, the intensity of Alcian Blue and Safranin O stainings in human chondrocytes were comparable to that observed in cKIT+ AFSCs after chondrogenic differentiation. Supplementary Fig. 2a-j illustrates the bright field pictures of the morphology of the cells before and following the chondrogenic induction.

Quantification of Alcian Blue staining revealed a significantly higher percentage of positively stained area in the differentiation condition compared to the expansion phase (Fig. 5u). Before chondrogenic differentiation (expansion), the percentage of Alcian Blue-positive staining remained low across all groups (cKIT+: 16.0 ± 1.7%, cKIT-: 12.4 ± 5.1%, unsorted: 16.6 ± 1.4%, ASCs: 14.3 ± 11.2%, chondrocytes: 12.6 ± 1.8%). In contrast, chondrogenic differentiation led to a substantial increase in Alcian Blue staining, with the highest percentage observed in cKIT+ AFSCs (93.2 ± 4.4, p < 0.0001), and chondrocytes (95.4 ± 1.9%, p < 0.0001). The remaining groups also exhibited a significant increase in Alcian Blue staining compared to their respective non-differentiated controls conditions (cKIT-: 59.2 ± 3.0%, unsorted: 61.9 ± 5.0%, ASCs: 60.0 ± 5.8%, p < 0.0001), though to a lesser extent than the cKIT+ AFSCs, and chondrocytes. Similar results were obtained for the quantification of Safranin O positively stained area (Fig. 5v). In the non-differentiated controls (expansion), the percentage of Safranin O stained area remained relatively low in all analyzed cell groups (cKIT+: 36.0 ± 0.5%, cKIT-: 11.9 ± 1.4%, unsorted: 23.3 ± 1.1%, ASCs: 32.3 ± 4.0%, chondrocytes: 41.0 ± 1.9%). Following the chondrogenic induction, the percentage of Safranin O stain increased to 86.2 ± 4.3% for cKIT+ AFSCs (p < 0.0001), to 64.2 ± 0.4% for cKIT- amniocytes (p < 0.0001), to 49.2 ± 1.5% for unsorted amniocytes (p < 0.001), to 57.3 ± 1.6% for ASCs (p < 0.001), and to 98.5 ± 2.1% for chondrocytes (p < 0.0001). It is also worth to highlight that following the chondrogenic induction, the Safranin O positively stained area was significantly higher in cKIT+ AFSCs, compared to that area observed in cKIT- amniocytes (p < 0.0001), unsorted cells (p < 0.0001) and ASCs (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

The present study evaluated and characterized the human AFSCs derived from non-healthy, spina bifida aperta (SBA) pregnancies (MMC and MS) by focusing on gene and protein expression changes. The following aspects need to be addressed in further details.

Primarily, we detected in human amniotic fluid samples derived from SBA pregnancies 9.2 ± 7.4% of cKIT-expressing amniocytes. This in contrast to the study of Coppi at al., reporting that about 1% of cells in amniotic fluid of healthy human pregnancies express cKIT14. In addition, we have observed high variations in cKIT expression between different SBA donors and consequently high values of standard deviation. It is important to mention, that the number of cKIT positive amniocytes found in the amniotic fluid of healthy human pregnancies strongly depends on the gestational week32. Particularly, cKIT+ AFSCs appear already at 7th gestational week and their concentration peaks at week 20 with approximately 90 × 104 cells per fetus33,34. Importantly, in our settings, we used human amniotic fluid of advanced gestational age (between 23 and 26 gestational week) which may significantly influence the number of cKIT-expressing stem cells.

In addition, the cellular composition of amniotic fluid may be affected by the SBA defect itself. It was previously published, that amniotic fluid derived from rat fetuses with open neural tube defect contains a population of cells characterized by the expression of early stem/progenitor cell markers, which was not detected in the amniotic fluid of corresponding healthy (control) rat donors30. Quantitative amniotic cell profiling in rodents showed the significant increase of the number of mesenchymal stem cells in the animals with spina bifida at embryonic day 19 (E19) in comparison to the healthy controls35. Moreover, it has been shown that the induction of MMC in a sheep model leads to the increase of the number of PAX3-positive progenitor cells24.

In addition, the SBA, as a neural tube defect, occurs at different degrees of severity. The main predictors of severity of MMC/MS lesion are level and size of the defect36. We hypothesize the severity of the SBA (particularly the size of the defect) may also influence the cellular composition of human amniotic fluid. Indeed, we have observed that there is a specific trend showing that the defects located in the thoracic region are associated with the higher percentage of cKIT-expressing cells in the amniotic fluid. Therefore, we speculate that this relatively high number of cKIT+ amniocytes from amniotic fluid of human SBA fetuses in our analysis could be an effect of two factors: (i) advanced gestational age as well as (ii) the presence of SBA defect and degree of its severity.

In addition, in vitro cultivation of cKIT+ AFSCs has been observed to result in the partial loss of cKIT protein expression within these cells. This is consistent with the study of Wysoczynski et al., who showed that cKIT expression is lost during in vitro expansion of cKIT+ cardiac mesenchymal stem cells37. This phenomenon underscores the dynamic nature of cellular markers, which can be influenced by the microenvironment provided during in vitro culture. It is important to note that in vitro cultivation may potentially lead to changes in marker expression. Additionally, while FACS sorting is a valuable tool for isolating specific cell populations, it is not infallible, and the presence of negative cells within a supposedly cKIT positive population cannot be entirely excluded. Cascario et al. showed that FACS allows for the enrichment of cKIT+ AFSCs from the heterogenous populations of amniocytes38. Furthermore, they revealed that after selection approximately 55% of cKIT+ cells express cKIT protein.

The cellular phenotype of mid-gestation AFSCs is situated between embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) as AFSCs display markers of both ESCs and MSCs. Accordingly, it was previously described by various groups, that healthy fetus derived cKIT+ AFSCs can be readily expanded in vitro and are positive for typical MSCs markers, including CD90, CD105, and CD44, CD29, CD73, but lack the expression of CD34, and CD4514,34,39,40,41. In contrast to MSCs, the AFSCs express also some of the pluripotency-associated antigens, including NANOG and OCT4 9. In our study, we compared the expression of typical mesenchymal and pluripotent stem cell markers in cKIT+, cKIT- and unsorted amniocytes isolated from late second trimester amniotic fluid of SBA fetuses. In addition, we used ASCs as a control as these cells are considered as somatic MSCs that should lack pluripotency markers. Although the CD90 protein was expressed at comparable level in all amniocytes groups, we found significantly higher mRNA expression of this marker in cKIT+ amniocytes, in comparison to the negative and unsorted cells. Most importantly, the level of CD90 mRNA in cKIT+ amniocytes was comparable to that observed in ASCs. There are many reports describing the expression of CD90 in MSCs of different sources, especially in an undifferentiated cell state42,43,44,45. In addition, it has been reported that fibroblastoid cells of amniotic fluid express higher levels of CD90 than the epitheloid cells46, which is in accordance with our data. Particularly, we have observed that cKIT+ amniotic fluid cells exhibit a spindle shape, fibroblastoid phenotype with upregulated mRNA expression of CD90 and downregulation of CK8, which confirm a mesenchymal phenotype of these cells.

We have also observed that discrepancy in CK8 expression in cKIT+ AFSCs on the protein and mRNA level. Here, we would like to highlight the fact that in our flow cytometry analysis, we utilized a panCK marker comprising a cocktail of antibodies recognizing the majority of human cytokeratins thereby capturing a broader spectrum of cytokeratin expression. Conversely, our qRT-PCR analysis focused specifically on CK8 expression. Additionally, it is plausible that there might be post-transcriptional or post-translational regulatory mechanisms at play, leading to the observed protein expression patterns differing from mRNA levels.

The pluripotency of amniocytes is still controversial with various publications stating contradictory results16,47,48. The transcription factors Nanog, OCT4 and SOX2 have been shown to be the important regulators of pluripotency13. Wang et al. revealed that, in contrast to the cKIT- amniocytes, cKIT+ AFSCs derived from healthy fetuses of 16–22 gestational week have a strong expression of NANOG and OCT449. This is in contrast to our data, showing a comparable moderate expression of pluripotency markers in all analyzed amniocytes groups. It is worth to mention here that according to previously published results the healthy cKIT+ AFSCs from early fetal development represent a more undifferentiated phenotype compared to the cells of advanced pregnancy48. Moschidou et al. discovered, that similarly to the 1st trimester cKIT+ AFSCs, mid-trimester cells express OCT4, but in contrast to the 1st trimester cells they lack the expression of NANOG48. Since we used amniocytes of fetuses with SBA isolated during the end of the second trimester, the expression of the pluripotency markers could already be decreased. Moreover, some publications question the existence of pluripotent stem cells in the amniotic fluid. Vlahova et al., suggested that mid-trimester AFSCs are entirely negative for both NANOG and OCT4 and highlighted the necessity of using appropriate positive controls when characterizing the stemness in cells16.

In addition, we would like to point out that according to our data the expression of OCT4 in cKIT+ amniocytes on protein level was significantly higher than in adult ASCs which are known as multipotent, somatic mesenchymal stem cells. This finding confirms the notion that cKIT+ amniocytes from amniotic fluid of SBA fetuses could share the specific features with both somatic multipotent MSCs (expression of MSCs markers) and pluripotent ESCs (expression of OCT4).

The main limitation of this study is that it includes exclusively amniotic fluid samples from individuals diagnosed with open spina bifida defect. While this provided valuable insights into the cellular composition and the presence of stem cells in spina bifida amniotic fluid samples, the absence of healthy control samples poses a limitation in terms of comparative analysis. Healthy amniotic fluid samples from physiological pregnancies can only be acquired during amniocentesis procedures. However, these procedures have declined in modern medicine due to the advancements in non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)49, making it extremely challenging to include healthy samples in the research analysis. Furthermore, amniocentesis is generally performed between 18 and 20 gestational week. In this study, amniotic fluid samples were acquired during prenatal surgeries to close MMC/MS defect which is usually performed at 23–26 week of gestation. Therefore, the inclusion of healthy amniotic fluid from earlier gestation age samples is also questionable as the embryonic development stage of these cells differs from that of cells isolated from spina bifida-associated amniotic fluid samples. Nevertheless, the data generated in this study holds considerable potential for advancing the application AFSCs in the field of tissue engineering, specifically in addressing spina bifida. These AFSCs could be potentially differentiated into chondrocytes. This opens up avenues for the development of fetal tissue-engineered cartilage grafts, which, when applied for in utero treatment of spina bifida, may offer enhanced protection to the spinal cord. Notably, AFSCs have been previously employed in cellular therapies for MMC in animal models. For instance, Fauza et al. investigated the application of AFSCs in so called transamniotic stem cells therapy (TRASCET). In this model, AFSCs were observed to selectively migrate to the neural tube defect, offering partial coverage to the spinal cord in experimental syngeneic fetal rat models of MMC50,51,52. Additionally, AFSCs have been used to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) which in turn have been applied for the development 3D tissue engineered skin constructs53. This artificial skin was then successfully applied to cover and protect the open spine in fetal rat model of MMC. In our study, we showed that amniotic fluid from individuals diagnosed with open spina bifida presents a promising and supplementary reservoir of stem cells. These cells could be potentially used in both autologous and allogeneic therapeutic approach to treat MMC defects, particularly in situations where the availability of amniotic fluid samples from healthy donors is limited.

In conclusion, this is to our best knowledge the first study characterizing the human cKIT+ amniocytes isolated from amniotic fluid of fetuses suffering from SBA. We have shown that the isolation of stem cells from spina bifida derived amniotic fluid samples is feasible and that these cells may share characteristics with both somatic and embryonic stem cells. Our findings are of pivotal importance for future regenerative medicine application of AFSCs for the in utero management of SBA defect.

Materials and methods

Human samples

Human amniotic fluid samples from fetuses with spina bifida aperta (MMC or MS) were obtained during open fetal-maternal surgeries after patients gave their written informed consent. The operations were performed at University Children’s Hospital in Zurich. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Kanton Zurich (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2015–0247 and BASEC No. PB_2020–00066). Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of details of patients involved in this study, including gestation time, spina bifida defect type, lesion level, as well as cystic sac’s dimensions (width, length, and height). The study encompasses a total of 17 patients, with 2 diagnosed with MS (SBA5 and SBA12), and the remaining 15 diagnosed with MMC. The average gestational age across all subjects is 178 days ± 6 days. Notably, 3 amniotic fluid samples were collected from fetuses with a defect located in thoracic region, 7 amniotic fluid samples from fetuses with lumbar region defects, and another 7 samples from sacral region defects. To better represent the size of the MMC/MS lesions, the sac’s length and width were multiplied and the results are presented as the area of the defect base (mm2. Among all fetuses involved in the study 10 were males and 7 were females.

Human subcutaneous adipose tissue samples were obtained from fat lipoaspirates from human adult healthy donors from abdominal body location. The lipoaspirates were obtained from the White House, Center for Liposuction Zurich, after receiving the written informed consent from the patients. Experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Kanton Zurich (BASEC request No. 2018 − 00269).

Human articular chondrocytes were purchased from Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany).

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Isolation of human amniocytes

The amniocytes were isolated from amniotic fluid samples as previously described with modifications14. Briefly, 50 ml of amniotic fluid were placed in 50 ml tubes (Falcon, USA) and centrifuged for 10 min at 300 g. The supernatant was aspirated and the pellet was re-suspended in 10 ml of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% of penicillin/streptomycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland). The cell suspension was plated on cell culture dishes. The amniocyte cultures were left undisturbed for 4–5 days under a humidified atmosphere at 37° С with 5% СО2 to allow appropriate cell adherence. Subsequently, the cells were washed 3 times with DPBS (Sigma Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) to remove cell debris and the fresh medium was added. The amniocytes were grown in culture at 37° С with 5% СО2 until large colonies appeared. The medium was changed every second day.

Isolation of human adipose derived stem cells (ASCs)

The adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) were isolated from lipoaspirates as previously described54,55. Briefly, the lipoaspirates were transferred into 50 ml Falcon tubes (Falcon, USA), diluted in Modified Eagle’s Medium (αMEM, ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland), and digested in 0.075% collagenase type II (355 U/mg, Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) for 60 min at 37 °C under constant mechanical shaking. Afterwards, the suspension was centrifuged for 15 min at 350 g, and the supernatant containing oil, cell debris, and serum was aspirated. Further, 5 ml of αMEM medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) was added and the resulting pellet was re-suspended. The cell suspension was then filtered through a 100 μm strainer (Falcon, USA) and centrifuged for 15 min at 350 g. To lyse the erythrocytes, prewarmed ACK lysis buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) was added to the cell suspension and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. The lysis of the erythrocytes was repeated until the red blood cells were not evident in the cell pellet. After centrifugation for 10 min at 350 g, the stromal vascular faction (SVF) was re-suspended in complete medium consisting of αMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% HEPES, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin-streptomycine-glutamin (100x) solution (all from ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland), stained with trypan blue (Sigma), and counted by using a Neubauer chamber. We routinely isolated 1.6 -0.9 × 105 nucleated cells from 1 ml of a fat liposuction biopsy. For monolayer expansion, SVF cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 103 cells/cm2 onto tissue culture plates, cultured at 37° С with 5% СО2 in complete medium supplemented additionally with 5 ng/ml FGF-2 (R&D Systems, Zug, Switzerland) and passaged at a density of 3 × 103 cells/cm2 when confluent. ASCs at P3-P4 were used for further experiments.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of cKit+ amniocytes

Amniocytes at passage 0 (P0) were harvested using 0.5% Trypsin/EDTA (ThermoFisher, Basel, Switzerland). Cell suspensions were stained with ZombieAqua Viability Kit (1:600, Biolegend, London, United Kingdom) to eliminate dead cells as well as with cKIT-PE antibody (clone 104D2, 1:10, Dako, Baar, Switzerland) for 20 min at 4 °C. In addition, cells were stained with PE isotype control (mouse IgG1, 1:10, Dako, Baar, Switzerland) in order to eliminate background signal. After incubation, cells were washed in FACS buffer (DPBS + 0.5% BSA + EDTA; all ThermoFisher, Basel, Switzerland) and sorted using BD FACSAria™ III Cell Sorter (Flow Cytometry Facility, University of Zurich). Cells were sorted into two different groups: cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes. Eventually, the sorted amniocytes were plated on cell culture dishes, expanded, and used for further experiments.

In vitro expansion of sorted cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes

Following FACS separation, cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes were centrifuged, resuspended in expansion medium containing high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% of penicillin/streptomycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) and counted using Trypan Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) by an automated cell counter. Cells were seeded on cell culture dishes at the density of 3 × 103 cells/cm2. Cells were cultured in expansion medium composed of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% of penicillin/streptomycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) until they reached 70–80% confluence. If necessary, cKIT+, cKIT-, and unfractioned amniocytes were further passaged using 0.5% Trypsin/EDTA (ThermoFisher, Basel, Switzerland). Cells at a maximum passage of 4 were used for further experiments. Unfractioned amniocytes were cultured using same settings and used as a control.

In vitro expansion of human articular chondrocytes

Human chondrocytes were cultured as previously described56. Briefly, human articular chondrocytes were thawed, centrifuged, and seeded on tissue culture plates at density of 1.0 × 105 cells/cm2. Chondrocytes were cultured in high glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS, 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid, 1% ITS premix premix (5 µg/mL insulin, 5 µg/mL transferrin, and 5 ng/mL selenious acid), 10 µg/ml gentamycin, 40 µg/ml L-proline (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

Flow cytometry analysis

For evaluation of the phenotype of sorted cells, cKIT+ (n = 8), cKIT- (n = 8), and unfractioned (n = 8) amniocytes at passage 2–4 were harvested from culture plates using 0.5% Trypsin/EDTA (ThermoFisher, Basel, Switzerland). As control, human ASCs (n = 3) were stained using the same settings. Subsequently, cells were washed once with FACS buffer (DPBS + 0.5% BSA + EDTA), and then incubated for 20 min with appropriate labeled or non-labeled antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used: cKIT-PE (clone 104D2, 1:10, Dako, Baar, Switzerland), CD105-Alexa Fluor 488 (clone 43A3, 1:50, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), CD44-PE (clone BJ18, 1:50, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), CD90-FITC (clone 5E10, 1:20, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), NANOG-Alexa Flour 647 (clone 16H3A48, 1:50, London, United Kingdom), OCT4-Brilliant Violet 421 (clone 3A2A20, 1:50, London, United Kingdom), KLF4 (polyclonal, 1:100, ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland), PanCK (clone AE1/AE3, 1:100, Dako, Baar, Switzerland). The following secondary antibodies and isotype controls: PE isotype control (mouse IgG1, 1:10, Dako, Baar, Switzerland), isotype control Alexa Fluor 647 (clone MOPC-21, mouse IgG1, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), Brilliant Violet 421 isoytpe control (clone 16H3A48 mouse IgG2b, 1:50, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), PE isotype control (clone MOPC-21, mouse IgG1, 1:50, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), Alexa Fluor 488 isotype control (clone MOPC-21, mouse IgG1, 1:20, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom), Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:200, Abcam, Lucerne, Switzerland), FITC secondary antibody (1:100, Dako, Baar, Switzerland). In order to eliminate dead cells, cells were additionally stained with ZombieAqua Viability Kit (1:600, BioLegend, London, United Kingdom). To detect intracellular epitopes, cells were in addition permeabilized using 10% saponin (ThermoFisher, Basel Switzerland). The non-labeled antibodies were visualized using appropriate FITC or Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies. Following the washing in FACS buffer (DPBS + 0.5% BSA + EDTA), cells were fixed using 2% PFA and measured using SR II Fortessa 4 L with HTS (Flow Cytometry Facility, University of Zurich). Data were analysed using FlowJo software (BD Life Sciences).

Hierarchical steps during gating strategy involved: (a) identification of the cell population of interest using forward versus side scatter (FSC vs. SSC) gating, (b) exclusion of cell doublets using forward scatter height versus forward scatter area (FSC-H vs. FSC-A) (c) exclusion of dead cells using Zombie Aqua staining, (d) gating on cKIT+ and cKIT- amniocytes.

qRT-PCT

Total RNA was extracted from sorted (P2-4) cKIT+ (n = 8), cKIT- (n = 8), and unfractioned (n = 8) amniocytes as well as from adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) (n = 2) using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity was measured using an Epoch spectrophotometer (Take3 micro-volume plate, BioTek, Lucerne, Switzerland). Only pure RNA with absorption ratios A260/A280 ~ 2.0–2.1 and A260/A230 ~ 2.1–2.3 were used for qRT-PCR. RNA was stored at − 80 °C until further use. 1000ng of RNA from each sample was used for cDNA synthesis using GoScript Reverse Transcriptase Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Dubendorf, Switzerland). SYBR Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) was used to perform qRT-PCR analysis. The level of gene expression in each sample was normalized to the corresponding housekeeping gene values and is presented as a fold change relative to the values of reference sample. Primers were purchased from Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland) and the sequences are presented in Table 2. The qRT-PCR was performed using QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland). We calculated the relative mRNA expression using the delta delta Ct method (2−ΔΔCt)57. cKit+ amniocytes were used as a reference sample and GAPDH was used as housekeeping gene. All samples were analyzed in triplicates.

Differentiation of cKIT+ amniocytes into chondrocytes

Chondrogenic differentiation was performed as previously described58. Briefly, cKIT+ AFSCs, as well as cKIT−, and unsorted amniocytes at P2-P4 were seeded onto 5 cm cell culture dishes and cultured in expansion medium containing high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% of penicillin/streptomycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) until they reached 90% confluency. Subsequently, regular expansion medium was removed and replaced with chondrogenic differentiation medium composed of high glucose DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 5% FBS, 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid, 40 µg/ml L-proline, 1% ITS + premix (5 µg/mL insulin, 5 µg/mL transferrin, and 5 ng/mL selenious acid), 10 ng/mL TGF-β3, and 10 µg/mL gentamycin (all from ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were cultured in chondrogenic differentiation medium for 4 weeks in vitro. ASCs and human chondrocytes were cultured using the same settings and used as positive control.

Alcian blue and safranin O stainings

Alcian Blue and Safranin O histological stainings were performed to detect the chondrogenic differentiation according to the previously published protocols58,59.

For Alcian Blue Staining, chondrogenically induced cKIT+ AFSCs, cKIT−, and unsorted amniocytes as well as ASCs and chondrocytes were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature and stained with 1% Alcian Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) in glacial acetic acid for 30 min. Subsequently, cells were washed in distilled water and visualized under a light inverted microscope.

For Safranin O staining, chondrogenically induced cKIT+ AFSCs, cKIT-, and unsorted amniocytes as well as ASCs and chondrocytes were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% Safranin O (ThermoFisher Scientific, Basel, Switzerland) in distilled water for 30 min. After removal of Safranin O solution, the cells were washed in distilled water and visualized under a light inverted microscope. The positively stained Alcian Blue/Safranin O area was quantified using Fiji software as previously described in60.

Statistical analysis

All results are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 4.0 (Graph Pad software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Comparisons between groups were performed using (i) Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric statistical test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for graphs presented in Figs. 3 and 4 and (ii) one-way Anova with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for graphs presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 and (iii) two-way Anova with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test for graphs presented in Fig. 5. ns indicates p > 0.05 (not significant). * indicates p ≤ 0.05 (significant). ** indicates p ≤ 0.01 (very significant). *** indicates p ≤ 0.001 (extremely significant). **** indicates p ≤ 0.0001 (extremely significant).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Shamsnajafabadi, H. & Soheili, Z. S. Amniotic fluid characteristics and its application in stem cell therapy: A review. Int. J. Reproductive Biomed. 20, 627–642 (2022).

Loukogeorgakis, S. P., De Coppi, P. & Concise Review Amniotic fluid stem cells: The known, the unknown, and potential regenerative medicine applications. Stem Cells 35, 1663–1673 (2017).

Underwood, M. A., Gilbert, W. M. & Sherman, M. P. Amniotic fluid: Not just fetal urine anymore. J. Perinatol. 25, 341–348 (2005).

Van Dyke, D. L. & Milunsky, A. Amniotic fluid constituents, cell culture, and neural tube defects. in Genetic Disorders and the Fetus 140–196 (Wiley, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119676980.ch3.

Tsai, M. S., Lee, J. L., Chang, Y. J. & Hwang, S. M. Isolation of human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from second-trimester amniotic fluid using a novel two-stage culture protocol. Hum. Reprod. 19, 1450–1456 (2004).

Beall, M. H., van den Wijngaard, J. P. H. M., van Gemert, M. J. C. & Ross, M. G. Amniotic fluid water dynamics. Placenta 28, 816–823 (2007).

Gosden, C. M. Amniotic fluid cell types and culture. Br. Med. Bull. 39, 348–354 (1983).

Parolini, O., Soncini, M., Evangelista, M. & Schmidt, D. Amniotic membrane and amniotic fluid-derived cells: Potential tools for regenerative medicine? Regen. Med. 4, 275–291 (2009).

Prusa, A. R., Marton, E., Rosner, M., Bernaschek, G. & Hengstschläger, M. Oct-4-expressing cells in human amniotic fluid: A new source for stem cell research? Hum. Reprod. 18, 1489–1493 (2003).

Cananzi, M., Atala, A. & De Coppi, P. Stem cells derived from amniotic fluid: New potentials in regenerative medicine. Reprod. BioMed. Online 18, 17–27 (2009).

Scholer, H. R., Balling, R., Hatzopoulos, A. K., Suzuki, N. & Gruss, P. Octamer binding proteins confer transcriptional activity in early mouse embryogenesis. EMBO J. 8, 2551–2557 (1989).

Nichols, J. et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 95, 379–391 (1998).

Niwa, H., Miyazaki, J. I. & Smith, A. G. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat. Genet. 24, 372–376 (2000).

De Coppi, P. et al. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 100–106 (2007).

Arnhold, S. et al. Amniotic-fluid stem cells: Growth dynamics and differentiation potential after a CD-117-based selection procedure. Stem Cells Int. 2011, 715341 (2011).

Vlahova, F. et al. Human mid-trimester amniotic fluid (stem) cells lack expression of the pluripotency marker OCT4A. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–15 (2019).

Sahni, M., Alsaleem, M. & Ohri, A. Meningomyelocele. StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2022).

Meuli, M. et al. In utero surgery rescues neurological function at birth in sheep with spina bifida. Nat. Med. 1, 342–347 (1995).

Zepf, J. et al. Subsequent pregnancy outcomes after open in utero spina bifida repair. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 49, 442–450 (2022).

Muraszko, K. M. & Hervey-Jumper, S. L. Myelomeningocele. in Operative Pediatric Surgery 7th edn 975–984 (CRC, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1201/b13198-113.

Meuli, M. & Moehrlen, U. Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele: A critical appraisal. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 23, 103–109 (2013).

Marotta, M. et al. Isolation, characterization, and differentiation of multipotent neural progenitor cells from human cerebrospinal fluid in fetal cystic myelomeningocele. Stem Cell. Res. 22, 33–42 (2017).

Shieh, H. F. et al. Transamniotic stem cell therapy (TRASCET) in a rabbit model of spina bifida. J. Pediatr. Surg. 54, 293–296 (2019).

Ceccarelli, G. et al. Molecular signature of amniotic fluid derived stem cells in the fetal sheep model of myelomeningocele. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 1521–1527 (2015).

Nguyen, L. T. et al. Outcomes of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell administration in the treatment of neurologic sequelae in children with spina bifida. Stem Cell. Res. Ther 14, (2023).

Wei, X. et al. Intra-amniotic mesenchymal stem cell therapy improves the amniotic fluid microenvironment in rat spina bifida Aperta fetuses. Cell Prolif 56 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Combining bone collagen material with hUC-MSCs for applicationto spina bifida in a rabbit model. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep. 19, 1034–1050 (2023).

Guilbaud, L. et al. In utero treatment of myelomeningocele with allogenic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in an ovine model. Curr. Res. Transl. Med 70 (2022).

Wang, A. et al. Placental mesenchymal stromal cells rescue ambulation in ovine myelomeningocele. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 659–669 (2015).

Turner, C. G. et al. The amniotic fluid as a source of neural stem cells in the setting of experimental neural tube defects. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 548–553 (2013).

Zieba, J., Miller, A., Gordiienko, O., Smith, G. M. & Krynska, B. Clusters of amniotic fluid cells and their associated early neuroepithelial markers in experimental myelomeningocele: correlation with astrogliosis. PLoS One 12, (2017).

Shaw, S. W. S. et al. Human amniotic fluid stem cells have better potential in early second trimester of pregnancy and can be reprogramed to iPS. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 56, 770–774 (2017).

Cananzi, M. & De Coppi, P. CD117 + amniotic fluid stem cells: State of the art and future perspectives. Organogenesis 8, 77–88 (2012).

Ditadi, A. et al. Human and murine amniotic fluid c-Kit + Lin- cells display hematopoietic activity. Blood 113, 3953–3960 (2009).

Pennington, E. C. et al. The impact of gestational age on targeted amniotic cell profiling in experimental neural tube defects. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 37, 65–69 (2015).

Eghwrudjakpor, P., Wokocha, S. & Eneh, A. Predicating outcome following surgery for myelomeningocele: A upth experience. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 5, 103–105 (2005).

Wysoczynski, M. et al. A new method to stabilize C-Kit expression in reparative cardiac mesenchymal cells. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 4, 212831 (2016).

Casciaro, F. et al. Effect of the enrichment in c-kit stem cell potential of foetal human amniotic fluid cells: Characterization from single cell analysis to the secretome content. Biomedicines 11 (2023).

Moschidou, D. et al. Human mid-trimester amniotic fluid stem cells cultured under embryonic stem cell conditions with valproic acid acquire pluripotent characteristics. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 444–458 (2013).

Di Trapani, M. et al. Immune regulatory properties of CD117pos amniotic fluid stem cells vary according to gestational age. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 132–143 (2015).

Schiavo, A. A. et al. Endothelial properties of third-trimester amniotic fluid stem cells cultured in hypoxia. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 6, 209 (2015).

Baghaei, K. et al. Isolation, differentiation, and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 10, 208–213 (2017).

Ritter, A. et al. Characterization of adipose-derived stem cells from subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues and their function in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 6, 34475–34493 (2015).

Kern, S., Eichler, H., Stoeve, J., Klüter, H. & Bieback, K. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells 24, 1294–1301 (2006).

Shang, Y., Guan, H. & Zhou, F. Biological characteristics of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells and its therapeutic potential for hematological disorders. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 1096 (2021).

Roubelakis, M. G. et al. In vitro and in vivo properties of distinct populations of amniotic fluid mesenchymal progenitor cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 15, 1896–1913 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Human amniotic fluid-derived c-kit + and c-kit - stem cells: Growth characteristics and some differentiation potential capacities comparison. Cytotechnology 64, 577–589 (2012).

Moschidou, D. et al. Molecular signature of human amniotic fluid stem cells during fetal development. Curr. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 8, 73–81 (2013).

Kim, S. M. et al. Change in rates of prenatal tests for chromosomal abnormality over a 12-year period in women of advanced maternal age. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 61, 453–460 (2018).

Turner, C. G. et al. Intra-amniotic delivery of amniotic-derived neural stem cells in a syngeneic model of spina bifida. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 34, 38–43 (2013).

Dionigi, B. et al. Partial or complete coverage of experimental spina bifida by simple intra-amniotic injection of concentrated amniotic mesenchymal stem cells. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 69–73 (2015).

Kunisaki, S. M. Amniotic fluid stem cells for the treatment of surgical disorders in the fetus and neonate. Stem Cells Transl Med. 7, 767–773 (2018).

Kajiwara, K. et al. Fetal therapy model of myelomeningocele with three-dimensional skin using amniotic fluid cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell. Rep. 8, 1701–1713 (2017).

Klar, A. S. et al. Characterization of vasculogenic potential of human adipose-derived endothelial cells in a three-dimensional vascularized skin substitute. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 32, 17–27 (2016).

Klar, A. S. et al. Tissue-engineered dermo-epidermal skin grafts prevascularized with adipose-derived cells. Biomaterials 35, 5065–5078 (2014).

Fisch, P. et al. Combining bioengineered human skin with bioprinted cartilage for ear reconstruction. https://doi.org/10.3929/ETHZ-B-000590550 (2023).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Michalak-Mićka, K., Büchler, V. L., Zapiórkowska-Blumer, N., Biedermann, T. & Klar, A. S. Characterization of a melanocyte progenitor population in human interfollicular epidermis. Cell. Rep. 38, 110419 (2022).

Ruhl, T. & Beier, J. P. Quantification of chondrogenic differentiation in monolayer cultures of mesenchymal stromal cells. Anal. Biochem. 582, 113356 (2019).

Gutiérrez, M. L., Guevara, J. & Barrera, L. A. Semi-automatic grading system in histologic and immunohistochemistry analysis to evaluate in vitro chondrogenesis. Univ. Sci. 17, 167–178 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are particularly grateful to the Fondation Gaydoul as well as to Children’s Research Center of the University Children’s Hospital Zurich for their support.

Funding

This project has received funding from the Fondation Gaydoul, Olga Mayenfisch Stiftung, Fondation Schmieder Bohrisch as well as Heidi-Ras Stiftung.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.M., T.B., U.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study, K.M.M, N.H., N.O.K, M.E., A.K, T.B., U.M. performed the acquisition and analysis of data, K.M.M drafted the manuscript, tables, and figures. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Michalak-Micka, K., Huerlimann, N., Ochsenbein-Kölble, N. et al. Isolation and characterization of human cKIT positive amniotic fluid stem cells obtained from pregnancies with spina bifida. Sci Rep 15, 20008 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03518-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03518-2