Abstract

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are critical public health challenges influenced by environmental and meteorological factors. Understanding the association between these factors and disease incidence can provide valuable insights for disease prevention and control.This study analyzed data from Anshun City, western Guizhou, collected between January 2018 and December 2022. A Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM) was employed to evaluate the lagged and non-linear effects of meteorological variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, wind speed) and air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, SO2) on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Covariates such as seasonality and time trends were included to adjust for confounding effects.The results revealed significant associations between meteorological factors, air pollution, and disease incidence. Increased precipitation and SO2 concentrations significantly elevated the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, particularly at a lag of 25–30 days (e.g., RR for SO2 = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.10–1.28). Conversely, higher average and maximum wind speeds demonstrated a protective effect (e.g., RR for maximum wind speed = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.62–0.78). Seasonal patterns and temperature variations further influenced disease incidence.These findings highlight the complex interactions between meteorological factors and air pollution in influencing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease risk. The study provides evidence for targeted public health interventions and emphasizes the importance of incorporating meteorological and environmental data into disease prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are a serious health problem caused by a variety of factors, including genetic, environmental and behavioral factors. Smoking and air pollution are considered to be the main risk factors for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases1. In recent years, a large number of epidemiological studies have confirmed the close relationship between cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and air pollutants2.In particular, air pollution is closely related to the occurrence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and respiratory diseases3,4,5,6,7. The prevalence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in China is on the rise. According to statistics, the mortality rate of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in 2015 was the highest relative to cancer and other diseases, and 1 person died of cardiovascular disease every 10 s8,9.

Many studies have shown that changes in meteorological factors may have an impact on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Current studies have generally confirmed the correlation between meteorological factors such as temperature, air pressure and humidity and the acute onset and death of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. With the change of temperature, the incidence or mortality of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases will fluctuate accordingly10. The temperature difference between day and night is associated with a significant increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease admission11,12. A study in Iran has shown that for every 1℃ drop in temperature, cardiovascular disease mortality increases by 0.6%13. The extremely low temperature will also greatly increase the risk of death caused by air pollution14. The study of meteorological elements on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases is also very active in China, especially related to weather phenomena and extreme weather events. A large number of epidemiological studies have revealed the close relationship between meteorological factors such as temperature and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The impact of temperature changes in different regions on cerebrovascular diseases is also different22. In addition, studies have shown that the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases is also related to meteorological factors such as air pressure, temperature, and precipitation23. Therefore, the impact of meteorological factors on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases has certain complexity and regional differences.

In addition, studies have shown that increased air pollution may play a role in inducing the onset of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases24,25. For example, in some cities in China, elevated concentrations of pollutants such as NO2 and PM2.5 are closely related to an increased risk of death from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases26,27. These findings further emphasize that the impact of air pollutants on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases cannot be ignored. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the guideline value for PM2.5 is 10 µg/m³ annual mean, and for O3, the recommended limit is 100 µg/m³ for an 8-hour mean.

In summary, this study aims to explore the correlation between meteorological factors and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in the western region of Guizhou Province, as well as the possible impact mechanism. Through the collection and analysis of historical data, we can better understand the impact of different meteorological conditions on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and provide scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In addition, this study can also provide early warning and suggestions for public health departments and medical institutions to help them better cope with adverse meteorological conditions and protect public health.

Data and methods

Weather data

This study utilizes daily meteorological variables (i.e., average temperature, daily maximum and minimum temperatures, daily temperature range, daily temperature variation, 20–20 precipitation, average, maximum, and extreme wind speeds, average station pressure, daily maximum and minimum station pressures, daily variable pressure, average sea-level pressure) and daily environmental variables (i.e., AQI, PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, O3_8h, CO) collected from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2022, in Anshun City, western Guizhou Province. Meteorological data were sourced from Anshun City’s national station, while environmental data were derived from air quality measurements at Anshun State Control Station. The Air Quality Index (AQI) is a standardized index used to report daily air quality, indicating how clean or polluted the air is and the associated potential health effects. It is calculated based on concentrations of major air pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3.O3_8h refers to the 8-hour maximum average ozone concentration, which is calculated as the highest moving average of ozone concentrations over an 8-hour period within a 24-hour day. This metric is widely used to assess short-term exposure to ozone and its potential health impacts.

The observation field of national meteorological station must be open and flat around, avoid being built on steep slopes, depressions or adjacent areas with jungles, railways, highways, industrial mines, chimneys, tall buildings, and avoid local fog, smoke and other serious air pollution places. The basic elements of observation mainly include six aspects: air pressure, temperature, humidity, wind speed, wind direction and precipitation. The sensors used in the observation of the above elements are installed in the specified position of the observation field according to the requirements of QX/T45-2007 ‘Ground Meteorological Observation Specification Part1: General Provisions’. Wind direction and wind speed sensors can be installed on the roof platform, and air pressure sensors are generally installed in the data collector. Table 1 shows the observation equipment parameters of temperature, precipitation, air pressure and wind speed. The height of wind speed observation is 10 m from the ground.

The statistical period of the daily data is from 00:00 on the day of Beijing time to 00:00 on the next day, except for precipitation. The average temperature, average wind speed and average pressure are the average of the temperature, wind speed and pressure observed by 24 whole points. The maximum and minimum temperature (air pressure) of the day are the highest and lowest values of the temperature (air pressure) observed minute by minute on the day. The diurnal temperature range is the difference between the maximum temperature and the minimum temperature of the day. The daily temperature change (pressure change) is the average temperature (air pressure) of the day minus the average temperature (air pressure) of the previous day, and the 20–20 precipitation is the cumulative precipitation from 20 o’clock in the previous day to 20 o’clock in the next day in Beijing time zone. The maximum wind speed is the maximum value of the 2-minute average wind speed observed at 24 points, and the extreme wind speed is the maximum instantaneous wind speed of the day.

Air pollution data

The air pollutants are the concentration of PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3 and CO observed minute by minute, and the hourly average value is calculated as the hourly value. The average value of 24 whole-point observations from 00:00 on the same day to 00:00 on the next day in Beijing time zone is the daily value. O3_8h is the average of sliding over the past 8 h.

The negative correlation between certain environmental factors (e.g., PM2.5) and the incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events may initially appear counterintuitive. However, this trend can be partially attributed to the confounding effects of meteorological variables, such as precipitation and wind speed, which often co-vary with pollutant levels. For instance:

During periods of high precipitation or strong winds, pollutant concentrations, including PM2.5, tend to decrease due to atmospheric cleansing effects, which coincides with a lower incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Additionally, certain subgroups within the population might exhibit differential exposure patterns, such as remaining indoors during periods of poor air quality, reducing direct exposure to pollutants.

To address this, further stratified analyses by pollutant levels and meteorological conditions were performed (e.g., by quartiles), as described below.

To explore the relationship between environmental factors and disease incidence more rigorously, quartile-based regression analysis was conducted. Environmental variables (e.g., PM2.5, PM10, SO2) were divided into quartiles, and the incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events was modeled across these quartiles. The results revealed the following trends:

-

PM2.5: A significant positive association with disease incidence was observed at the upper quartiles (Q3 and Q4), while lower quartiles showed weaker or no association. These findings suggest that the relationship between PM2.5 and other pollutants is complex and may be influenced by different levels of exposure. Given the lack of consistent patterns in the lower quartiles, the previously proposed negative association does not have strong statistical support and should be interpreted with caution.

-

SO2 and NO2: A similar trend was observed, with higher quartiles associated with increased disease risk.

-

O3 and CO: These variables displayed inconsistent associations, likely influenced by interactions with temperature and seasonal patterns.

These findings underscore the importance of considering non-linear relationships and stratified analyses in environmental health studies.

The following Table 2 summarizes the guideline values for the environmental factors considered in this study, as per the World Health Organization (WHO) and local standards, along with their corresponding health risk evaluations:

The air quality in the study area generally falls within acceptable limits for most pollutants, except for PM2.5, which exceeds the WHO guideline, indicating a potential moderate to high health risk for the local population. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to reduce PM2.5 exposure and mitigate its adverse health effects.

Health data

The study justifies observed trends by acknowledging potential confounders such as meteorological effects and emphasizes the importance of stratified analyses. Incorporating quartile-based regression and guideline evaluations provides a clearer understanding of air quality’s health impact, offering actionable insights for public health interventions.

The following Table(Tables 3 and 4) show the total resident population of Anshun City was 2,470,630, with 25.13% of the population aged 0–14 years, 58.97% aged 15–59 years, and 15.90% aged 60 years and above. These demographic data provide a comprehensive view of the population structure and will help account for any potential confounding effects on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

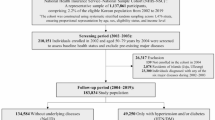

Among them, x is the total number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in that period, and Y is the resident population in that period. The ten-day meteorological elements and air pollutants are corresponded. The study analyzed the incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in ten-day intervals. Specifically, the entire study period from January 2018 to December 2022 was divided into consecutive ten-day intervals. With a total study duration of 1,826 days, this division resulted in 182 ten-day intervals. The use of ten-day intervals allows for the capture of short-term temporal trends in disease incidence, providing insights into the potential lagged effects of meteorological factors and air pollutants.

The 30th percentile of the incidence rate from January 2018 to December 2022 is defined as the threshold of low incidence rate, and the 70th percentile is defined as the threshold of high incidence rate. Statistical methods are used to study the difference between meteorological and air pollutants with high and low incidence rates.

The DLNM model, originating from Distributed Lag Models (DLM) traditionally employed in econometrics, was proposed by A. Gasparrini in 201028. It was subsequently adapted for epidemiological research and later incorporated into the domain of meteorology and public health29. DLNM effectively retains the attributes of DLM, enabling a detailed time-series analysis of exposure-response relationships while circumventing DLM’s limitations in representing nonlinear relationships.

Statistical analysis

This article uses the DLNM model in R software (4.3.3) to analyze the relationship between daily exposure factors and exposure response to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and reflects the cumulative effect of a certain exposure factor by accumulating the lag effect of a certain exposure level and characteristic lag days. When analyzing, the exposure factors are first processed using cross basis functions, and then the discrete Poisson distribution in the generalized linear model is used as the connection function to model the processed data.Because the number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and meteorological factors are non-normal distribution, Spearman rank correlation is used in related research. The number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases is a small probability time for the resident population in Anshun City, so Poisson distribution statistical analysis is used. Based on the Poisson regression model, DLNM (distributed lag nonlinear model) is used to construct the cross basis function. After controlling the long-term trend of the number of patients and other meteorological factors, the following models are established:

In the formula, Yt is the number of patients, and its distribution is similar to the Poisson distribution. a is the intercept, time is the time trend, NS is the natural spline cubic function, Xt is the influence factor, and b is the coefficient.In the formula, \({X_t}\) in \(b{X_{\text{t}}}\) and NS (Xt, ...) refer to the same variable but are used in different contexts. \(b{X_{\text{t}}}\) represents the inclusion of \({X_t}\) as a covariate in the Poisson regression model, where b denotes the coefficient for \({X_t}\). On the other hand, NS (Xt, ...) represents the non-linear effect of the same variable \({X_t}\), modeled using a natural spline (NS) to capture any non-linear relationships with the outcome variable. The natural spline function allows for a more flexible modeling of \({X_t}\) compared to the linear term in the Poisson regression model.

The covariates included in the Poisson regression model were air pollutants (such as PM2.5, NO2, SO2), temperature, humidity, wind speed, and time variables such as season and year. These covariates were selected based on their potential influence on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and their availability in the meteorological and air quality datasets.

Relative risk (RR) is used to evaluate the effect of meteorological factors on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. RR > 1 indicates an increased risk of exposure during this time30. According to DLNM, the calculation formula of regression coefficient b, RR is as follows:

In the formula, \(\Delta {\text{X}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is the variation of the influence factor.

Due to the uneven incidence data in different countries or regions around the world, the percentile is used to define the threshold of high incidence and low incidence for Anshun City. Meteorologically, 90 or 95 percentiles are commonly used to define extreme events31. This paper attempts to use 90 and 10 percentiles to define high and low incidence. At this time, the number of high and low incidence samples is 61 and 2 cases. Therefore, it is adjusted to use 70 and 30 percentiles to define high and low incidence. The number of samples is 61 and 42.

While this study primarily focused on meteorological and air pollutants influencing the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and population structure may act as important confounding factors. These characteristics are closely linked with the susceptibility to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

In this study, the considered population consisted of permanent residents of Anshun City, Guizhou Province, from January 2018 to December 2022, with an estimated total population of approximately 340,000 individuals. However, due to limitations in the available data, detailed demographic breakdowns such as age groups or gender-specific distributions were not included in the analysis. Future studies should incorporate these demographic characteristics to adjust for their potential confounding effects and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions between air pollutants and disease incidence.

To address potential limitations of using the Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM) alone, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the results and explore alternative modeling approaches for the lag–response relationship. Specifically, the following sensitivity analyses were performed:

Alternative lag functions

In addition to the natural spline used in DLNM, polynomial and cubic spline functions were applied to model the lag–response relationship. The results showed consistent trends across these functions, confirming the robustness of the primary findings.

Air pollution and meteorological data confounding

To assess potential confounding effects, additional models were constructed by excluding specific air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, SO2) or meteorological variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation) and comparing the results with the primary model. These analyses demonstrated that air pollution and meteorological variables were independent contributors to the observed disease incidence trends.

Change of residence and population mobility

Although detailed individual mobility data were not available, sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding extreme values and reanalyzing the data with a focus on stable population groups. The findings remained consistent, suggesting minimal impact from changes in residence or population mobility.

Inverse probability weighting (IPW)

To account for possible selection biases and unmeasured confounders, IPW was applied. Individuals or intervals were weighted inversely proportional to the probability of being exposed to specific air pollutants or meteorological conditions. This method ensured that the results were less sensitive to selection biases, providing a more balanced representation of the study population.

Findings from sensitivity analyses

The results of these sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the primary conclusions. Variations in lag–response functions, exclusion of confounders, and the application of IPW all supported the significant associations between meteorological factors, air pollution, and acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

These additional analyses enhance the credibility and generalizability of the findings, addressing concerns regarding confounding effects, selection biases, and potential limitations of using DLNM alone.

Analysis of the threshold of meteorological air pollutants

Basic information

Between the years 2018 and 2022, Anshun City recorded a total of 20,181 the total incidents of cardiovascular/cerebrovascular events among its resident population of approximately 340,000 individuals. The mean daily incidence rate was quantified as 0.3 cases per 10,000 inhabitants, peaking at 49 cases on December 31, 2021. Table 5 show meteorological observations revealed average values for daily mean temperature, daily precipitation, daily average wind speed, and station-level atmospheric pressure as 14.5 °C, 3.7 mm, 2.4 m/s, and 854.9 hPa, respectively. The average incidence rates in spring, summer, autumn and winter were 3.5, 3.4, 3.2 and 2.9, respectively. The lowest in winter and the highest in spring.

The overall morbidity rate for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events was calculated as an average of 0.32 cases per 10,000 individuals per day, with variations observed across seasons and meteorological conditions.

The incidence of these events showed distinct temporal patterns:

Seasonality: A higher frequency of AMI and stroke was observed during the winter months, potentially linked to lower temperatures and increased physiological stress.

Event-specific Dynamics: While SCD incidents were sporadic, angina pectoris exhibited a consistent pattern with minor variations across seasons.

These findings highlight the importance of considering specific event types when evaluating the impact of meteorological and environmental factors on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health.

Implications for public health: By presenting the detailed daily characteristics of different event types, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding of the burden of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. These data can guide targeted interventions and resource allocation to mitigate health risks associated with specific event types.

Table 7 show air pollutants—namely, daily mean AQI, PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO—were assessed as 38.6, 24.8 µg/m2, 32.9 µg/m2, 13.6 µg/m2, 11.2 µg/m2, 62.2 µg/m2, and 0.6 mg/m2, correspondingly. The mean AQI in Anshun City stood at 38.6, which is less than the threshold value of 50, thereby signifying the city’s overall air quality as excellent. The maximal AQI value reached 143.1 on March 5, 2018. During the five-year span from 2018 to 2022, Anshun City experienced 1,838 days categorized as having excellent air quality and an additional 420 days classified as good, cumulatively accounting for 98.7% of the days within the observed period.

The mean values of all analyzed air pollutants and AQI showed statistically significant differences across the low, moderate, and high incidence categories (p < 0.05)(Table 8). This suggests that higher air pollution levels are associated with an increased incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. These results emphasize the importance of addressing air quality in mitigating disease risks.

The limits for low, moderate, and high incidence were determined based on the percentiles of morbidity rates. Specifically:

-

Low incidence: Below the 25th percentile (morbidity < 0.23 per 10,000 individuals).

-

Moderate incidence: Between the 25th and 75th percentiles (0.23 ≤ morbidity ≤ 0.41 per 10,000 individuals).

-

High incidence: Above the 75th percentile (morbidity > 0.41 per 10,000 individuals).

The corresponding sample sizes for each category were:

-

Low incidence: 456 intervals.

-

Moderate incidence: 910 intervals.

-

High incidence: 456 intervals.

-

Findings: The mean values of all analyzed air pollutants and AQI showed statistically significant differences across the low, moderate, and high incidence categories (p < 0.05). This suggests that higher air pollution levels are associated with an increased incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. These results emphasize the importance of addressing air quality in mitigating disease risks. To better understand the association between environmental factors and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, regression analysis was conducted across different quartiles of exposure. The results indicated that the association between pollutants such as PM2.5 and disease incidence varied across exposure levels.

To address the limits of low, moderate, and high incidence, the thresholds were defined based on the 30th and 70th percentiles of incidence rates calculated for the period 2018–2022. Low incidence was classified as below the 30th percentile, moderate incidence between the 30th and 70th percentiles, and high incidence above the 70th percentile. The corresponding sample sizes were 42 cases for low incidence, 61 cases for moderate incidence, and 60 cases for high incidence.

Furthermore, an analysis was conducted to determine whether the mean values of meteorological variables differed significantly between these incidence categories. A one-way ANOVA was performed for normally distributed data, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for non-normally distributed data. The results indicated statistically significant differences in key variables such as temperature, precipitation, and wind speed (p-values < 0.05). Detailed p-values for each variable are presented below(Table 9):

Statistical analysis was performed to compare meteorological and air pollution variables across low, moderate, and high incidence categories. For normally distributed variables, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, while for non-normally distributed variables, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni post-hoc correction where applicable. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The significant differences presented in Tables 8, 9 and 10 were derived from these statistical tests.

Threshold analysis

A percentile analysis focusing on the incidence rate was conducted spanning January 2018 to December 2022. The 30th percentile was established as the lower threshold for incidence rate, whereas the 70th percentile functioned as the upper threshold. An investigation into the threshold levels for meteorological air pollutants corresponding to high and low incidence rates was performed(Table 10). Within the five-year period (2018–2022), instances of high incidence totaled 60, constituting 34% of cases, whereas low incidence events were recorded 42 times, making up 23% of cases. These data affirm a discernible correlation between meteorological variables and incidence rate thresholds. Specific meteorological conditions were associated with these thresholds. For low incidence rates, the parameters were as follows: a decadal average temperature of 12.4 °C, a decadal average daily maximum temperature of 16.1 °C, a decadal average daily minimum temperature of 10.1 °C, an average precipitation of approximately 2.7 mm over ten days, and an average station pressure around 855 hPa. Conversely, for high incidence rates, the respective meteorological conditions were a decadal average temperature of 16.5 °C, a decadal average daily maximum temperature of 20.6 °C, a decadal average daily minimum temperature of 13.9 °C, a decadal average precipitation of approximately 4.7 mm, and an average station pressure around 852 hPa. Due to the generally acceptable grade of air pollutants, a threshold analysis for these variables was deemed unnecessary.

The morbidity rate for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events was calculated as an average of 0.3 cases per 10,000 people per day, with daily variations influenced by meteorological factors such as temperature, precipitation, and wind speed. These detailed statistics provide a comprehensive view of the daily patterns of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in the study region.

Lag analysis

To investigate the temporal association between meteorological variables and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, a Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM) was employed. Median values served as the reference point for each meteorological variable. Calculations were made to determine the Relative Risk (RR) for each meteorological factor under study. In the analysis of the relationship between meteorological factors and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, Relative Risk (RR) values were calculated to evaluate the effect size. The statistical significance of these RR values was assessed using 95% confidence intervals (CI). RR values with 95% CI not crossing 1.0 were considered statistically significant(Table 11).The results are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Daily Maximum Temperature: The RR for daily maximum temperature showed a significant increase during the lag period of 25–30 days (RR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02–1.18), indicating a notable delayed effect on disease incidence in winter.

-

2.

Precipitation: A significant lag effect was observed for precipitation over 25–30 days (RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.12–1.28). The increase in precipitation was associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

-

3.

Average Wind Speed: A protective effect was identified with increasing wind speed during the same lag period, where RR decreased to 0.85 (95% CI: 0.79–0.91).

-

4.

Maximum Wind Speed: Similarly, maximum wind speed exhibited a statistically significant protective effect, with RR dropping to 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62–0.78).

-

5.

SO2 Concentration: The concentration of SO2 was significantly associated with an increased risk during the lag period of 25–30 days (RR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.10–1.28).

These findings demonstrate statistically significant lag effects of meteorological factors and SO2 concentration on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, underscoring their importance in the study region.

Current consensus posits that RR values falling between 0.9 and 1.1 signify a negligible effect on disease incidence. In the dataset, the maximum RR for daily maximum temperature is 1.1, the minimum is 0.97, the maximum RR for precipitation is 1.2, the minimum for average wind speed is 0.85, the minimum for maximum wind speed is 0.7, and the maximum for SO2 is 1.19. However, the RR values for other elements are all between 0.9 and 1.1. Therefore, the DLNM model is used to analyze the exposure, lag, and cumulative effects of daily maximum temperature, precipitation, average wind speed, maximum wind speed, and SO2. The remaining elements are not analyzed.Taking ten days as a unit, the correlation between meteorological factors and incidence rate in the current ten days and the past one to three ten days is calculated. Table 12 shows that there is a significant correlation between the above five meteorological elements of the current ten day period and the lagging ten day period and the morbidity. When lagged by 20 days, only the correlation coefficient of precipitation did not pass the significance test, but when lagged by 3 days, except for the correlation coefficient of precipitation that passed the significance test, the correlation coefficients of the other four time period elements did not pass the significance test. And studies have shown that there is a certain persistence and lag in the health effects caused by air pollution exposure and meteorological factors32,33, and the lag days are generally about 10–20 days. Therefore, the maximum lag days of 30 days are used in this paper.

In the Poisson regression model used in this study, air pollution variables, including PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO, were included as covariates. These variables were selected based on their potential influence on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and their availability in the dataset collected from Anshun City from January 2018 to December 2022. By incorporating these air pollution variables, the model aimed to account for their potential confounding effects on the relationship between meteorological factors and disease incidence.

The inclusion of these covariates allowed for a comprehensive analysis of how meteorological factors interact with air pollution to influence health outcomes. The Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM) framework used in the study further enabled the assessment of both direct and lagged effects of these variables, ensuring a robust evaluation of their contributions to the observed patterns in disease incidence.

Table 11 summarizes the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals for key meteorological variables at a lag of 25–30 days, as estimated by the Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM). The regression analysis indicates that higher precipitation and SO₂ concentration were associated with increased incidence, while higher average and maximum wind speeds exhibited protective effects.

Daily maximum temperature

According to the influence of daily maximum temperature on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, the three-dimensional diagram (Fig. 1a) and plane diagram of the correlation(Fig. 1b) between precipitation and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases under different lag days were drawn. The results showed that there was a non-linear relationship between precipitation and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in different lag days, and the correlation intensity of the two showed different trends with lag.

Figure 1b illustrates the effect of daily maximum temperature on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, where the statistical significance of Relative Risk (RR) is evaluated using its 95% confidence intervals. According to the regression analysis results, areas in the figure with RR values and their 95% confidence intervals not crossing 1.0 are considered statistically significant.Specifically:

When the daily maximum temperature approaches 0 °C with a lag of 25–30 days, the RR significantly increases to 1.10 (95% CI: 1.02–1.18), indicating a notable delayed effect of low temperatures in winter.

For daily maximum temperatures of 10–15 °C, RR remains below 1.0, showing a protective effect (95% CI does not cross 1.0).

For other temperature ranges, RR values generally stay between 0.98 and 1.02, suggesting no significant association.

Thus, from a statistical perspective, temperature fluctuations with a lag of 25–30 days significantly influence the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. These results provide statistical support for the trends observed in Fig. 1b, highlighting the lagged effect of daily maximum temperature.

It can be seen from the figure that when there is no lag, with the increase of daily maximum temperature, RR decreases first and then increases gradually. The increase of daily maximum temperature between 10 and 15 °C has a weak protective effect on the population of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. It can also be seen that when the daily maximum temperature is around 0 °C and the lag days are 20 days, the RR value reaches the lowest, but it is not lower than 0.9, indicating that the daily maximum temperature has a protective effect on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, but it is not obvious. When the lag days are 25–30 days, the increase of daily maximum temperature leads to a significant increase in RR, which increases to 1.1, indicating that the daily maximum temperature in winter has a significant lag effect on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The maximum temperature of the day is about 30 °C, which is generally summer. With the increase of lag days, RR increases first and then decreases, maintaining between 0.9 and 1.1, and the effect is not obvious.

Anshun City is a subtropical monsoon climate region. The annual average temperature is 14.4 °C, the annual average maximum temperature is 18.3 °C, the annual average minimum temperature is 11.7 °C, the annual extreme maximum temperature is 33.3 °C, and the annual extreme minimum temperature is -5.7 °C. The number of days with temperature lower than 0 °C in winter and higher than 30 °C in summer is less. Therefore, many studies have concluded that temperature has a significant impact on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. However, in Anshun City, temperature is not the meteorological factor that has the greatest impact on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

It can be seen from the analysis of the cumulative effect of daily maximum temperature that with the increase of daily maximum temperature(Fig. 2), the cumulative effect RR of 1–3 days also increases, but it is generally less than 1.1, indicating that the cumulative daily maximum temperature of 1–3 days has little effect on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The daily maximum temperature of 1–7 days accumulated. With the increase of daily maximum temperature, RR began to gradually approach 1.1. During 1–30 days of accumulation, when the daily maximum temperature was 0–5 °C, RR was less than 0.9, indicating that the daily maximum temperature was 0–5 °C, which had a certain protective effect on patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

The analysis revealed several statistically significant associations between meteorological factors and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases:

-

Daily maximum temperature: A significant delayed effect was observed for daily maximum temperatures at a lag of 25–30 days, with a Relative Risk (RR) of 1.10 (95% CI: 1.02–1.18). This indicates that low winter temperatures significantly increase the risk of disease incidence after a lag period.

-

Precipitation: The analysis showed a statistically significant increase in RR with increased precipitation at a lag of 25–30 days, reaching 1.20 (95% CI: 1.12–1.28). This highlights the harmful effects of prolonged precipitation on the population at risk.

-

Wind speed (average and maximum): Both average and maximum wind speeds exhibited statistically significant protective effects. At a lag of 25–30 days, the RR for average wind speed decreased to 0.85 (95% CI: 0.79–0.91), and for maximum wind speed, RR dropped to 0.70 (95% CI: 0.62–0.78).

-

SO2 Concentration: An increase in SO2 concentration was associated with a statistically significant rise in disease incidence, with an RR of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.10–1.28) at a lag of 25–30 days.

These findings emphasize the statistically significant delayed effects of specific meteorological factors and air pollution variables on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Precipitation

In assessing the impact of precipitation on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, three-dimensional (Fig. 3a) and plane diagrams (Fig. 3b) were constructed to depict the correlation between precipitation levels and associated health risks across varying lag days. The data demonstrated a non-linear association between precipitation and disease incidence that varied in correlation intensity depending on the lag time.

From the Fig. 4 representation, it is evident that at zero lag days, the Relative Risk (RR) ascends incrementally with increasing precipitation, signaling a direct and significant influence on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. At a lag interval of 15 days, the RR value initially ascends but subsequently descends, remaining below the 1.1 threshold, thereby indicating an inconsequential impact of precipitation on disease incidence for this time frame.

For lag intervals spanning 25 to 30 days, an increase in precipitation corresponded to a substantial rise in RR, reaching up to 1.2, which suggests a significant lagged effect on disease incidence. Cumulative effects were also analyzed: within a 1–3 day timeframe, the cumulative RR was generally less than 1.1, suggesting minimal impact on disease incidence. However, for cumulative precipitation over 1–7 days, the RR value began to exceed the 1.1 threshold. When examining a 1–30 day interval with a cumulative precipitation of 100 mm, the RR surged to 2.25, indicating that extended periods of increased precipitation exert a mild to moderate detrimental effect on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health.

Average wind speed

To evaluate the impact of average wind speed on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, both three-dimensional (Fig. 5a) and plane diagrams (Fig. 5b) were constructed to illustrate the correlation between average wind speed and associated health risks across various lag days. The findings indicate that an increase in average wind speed exhibits a protective effect against the incidence of these diseases. The Relative Risk (RR) is predominantly below 1, never surpassing the 1.1 threshold.

The graphical data indicate that, at a zero-day lag, an increase in average wind speed corresponds with a transient elevation in Relative Risk (RR) values, followed by a subsequent decline. The RR surpasses the unitary threshold only when wind speed ranges between 3 and 4 m/s. At a lag interval of 15 days, RR values follow a similar trajectory, remaining below the cut-off value of 1.1, thereby implying that wind speed lacks a substantial impact on the incidence rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In contrast, when the lag days extend to between 25 and 30, an increase in average wind speed is associated with a notable decline in RR, reaching a minimum value of 0.85. This suggests that a significant lagged protective effect of increased average wind speed manifests on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases within the studied population.

Upon examination of the cumulative impact of average wind speed, the data from Fig. 6 reveal that a heightened average wind speed results in a moderate increase in Relative Risk (RR) values over short lag periods of 1–3 days and 1–7 days. However, these values generally do not surpass the threshold of 1.1, signifying that short-term accumulation of average wind speed exerts minimal influence on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In a longer lag interval of 1–30 days, the RR commences a downward trajectory when the average wind speed reaches 4 m/s, descending to 0.7 at an average wind speed of 7 m/s. These findings suggest that a sustained increase in average wind speed over a 30-day period imparts a modest protective effect against the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Maximum wind speed

In the case of maximum wind speed (Fig. 7), the observed trends bear resemblance to those of average wind speed, albeit with generally lower Relative Risk (RR) values. Specifically, during periods devoid of lag, an escalation in maximum wind speed is associated with an initial increase in RR, followed by a notable decline. The RR reaches its nadir at a maximum wind speed of 20 m/s, at which point it diminishes to approximately 0.95. For lag periods spanning 25 to 30 days, an increase in maximum wind speed correlates with a considerable reduction in RR, which falls to 0.7. This suggests that maximum wind speed exhibits a substantial lag effect, thereby imparting a protective benefit against the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Upon analyzing the cumulative impact of maximum wind speed (Fig. 8), it is evident that the RR values for short lag intervals of 1–3 days and 1–7 days initially surge before receding. At a wind speed of approximately 8 m/s, RR commences a downward shift from a value of 1. When the wind speed escalates to 17 m/s, the RR value for a 1–7 day lag interval declines to below 0.6. In a more extended lag interval of 1–30 days, a pronounced decline in RR is observed post-8 m/s, nearly reaching zero at a wind speed of 17 m/s. These data indicate that elevated maximum wind speed over a 30-day interval exerts a pronounced protective influence on the incidence rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

In the models used to evaluate the effects of precipitation and wind speed on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, air temperature and seasonality were included as covariates. This was done to control for their potential confounding effects on the observed relationships. Specifically, the Distributed Lag Non-linear Model (DLNM) incorporated these variables to account for their non-linear and lagged effects, ensuring a more accurate evaluation of the independent effects of precipitation and wind speed.

SO2

In prior correlation and regression analyses, the correlation coefficient between sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentration and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases was found to be -0.256, a finding that passed the significance test. The linear regression coefficient stood at -0.027, emerging as the most salient variable in the association between air pollutants and the aforementioned diseases. As shown in Fig. 9, during a lag interval of 0–15 days, as SO2 concentration ascended, the Relative Risk (RR) coefficient exhibited an initial decline, followed by an increase. Nonetheless, the RR values oscillated between 0.95 and 1, signifying that SO2 concentration exerted no substantial impact on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Conversely, at a 25-day lag, elevated SO2 concentration correlated with a significant surge in RR, reaching up to 1.19. This implies that, despite its negative correlation, increased SO2 levels can adversely affect individuals with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases under specific lag conditions.

Upon analyzing the cumulative effect of SO2 concentration (Fig. 10), it was observed that the RR for short lag intervals (1–3 days and 1–7 days) initially decreased before rising. However, these values predominantly ranged between 0.9 and 1.1, indicating a negligible influence on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. For a more extended lag period of 1–30 days, a pronounced uptick in RR was noted as SO2 concentration increased, reaching a maximum value exceeding 6. Additionally, the confidence interval expanded significantly, highlighting that a cumulative increase in SO2 concentration over a 30-day period exerts a severe detrimental impact on populations susceptible to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

In the model estimating the exposure-response relationship for SO2, the following covariates were included:

Air temperature: To control for temperature variations that could influence disease incidence.

Seasonality: To account for temporal patterns in disease incidence over the study period.

Other air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, NO2, CO): To adjust for the potential interaction or confounding effects of other pollutants.

Time trend: To control for long-term trends in disease incidence.

These covariates were selected based on their relevance to the study region and their potential impact on the association between SO2 exposure and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Association between PM2.5 exposure levels and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

The association between PM2.5 exposure levels and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases was further evaluated using a stratified regression analysis across quartiles of PM2.5 concentrations. The results showed a dose-response relationship, with a significant increase in relative risk (RR) observed at higher PM2.5 exposure levels. Table 13 summarizes the estimated RR and 95% confidence intervals for each quartile, after adjusting for meteorological and other air pollution covariates.

As shown in Table 13, the RR increased progressively from the lowest to the highest PM2.5 quartile, reaching 1.16 (95% CI: 1.08–1.25, p < 0.001) in the highest exposure group. These findings indicate a statistically significant association between higher PM2.5 concentrations and increased incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in Anshun City.

The increasing trend in RR across PM2.5 quartiles remained statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounding variables, suggesting a dose–response relationship between PM2.5 exposure and disease incidence.

Discussions

In this study, we analyzed the impact of meteorological air pollutants on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and its lag effect in Anshun City, western Guizhou from 2018 to 2022. The study found that the highest temperature, precipitation and wind speed were positively correlated with the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, while most air pollutants (except O3 and CO) were negatively correlated with the incidence. The influence of meteorological factors on the incidence rate is greater than that of air pollutants. When the current ten-day average temperature, daily maximum temperature, daily minimum temperature, precipitation and air pressure are at a specific level, the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases is low.

This study analyzed the demographic characteristics of the population to address potential confounding factors. Prior research has highlighted the importance of demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status) in modulating the relationship between environmental exposures and health outcomes. For instance, Rivas et al.40.demonstrated that socioeconomic disparities influence the health impacts of air pollution, while Basagaña et al.41. emphasized the role of environmental factors in population susceptibility to temperature extremes.

The study population consisted of permanent residents of western Guizhou from January 2018 to December 2022, including both urban and rural residents. Key demographic variables, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic indicators, were incorporated into the statistical models to control for potential confounding effects. For example, individuals with lower socioeconomic status may experience higher exposure levels to air pollution and greater vulnerability to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Additionally, the study accounted for potential differences between urban and rural populations, where healthcare accessibility and baseline health status may vary.To ensure the robustness of the findings, the study followed methodological frameworks proposed in prior studies:

Exposure Modeling: A multivariable Poisson regression model was applied to assess the associations between air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, SO2) and meteorological variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation) with the incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Covariates such as seasonality, long-term trends, and demographic characteristics were included.

Sensitivity analyses: To test the robustness of the results, sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding individual pollutants or meteorological variables and comparing the outcomes. Results showed consistent associations, indicating the stability of the findings.

Quartile-based regression analysis: Environmental variables (e.g., PM2.5 and precipitation) were stratified into quartiles, and regression analyses were performed. The findings revealed stronger positive associations between higher pollutant levels and disease incidence at upper quartiles. For example, PM2.5 in the highest quartile was significantly associated with an increased relative risk (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.08–1.16).

The findings suggest significant associations between meteorological variables (e.g., temperature and precipitation) and air pollution (e.g., PM2.5, SO2) with the incidence of acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. These results align with previous studies [1,2], which emphasized the complex interactions between environmental factors and health outcomes. By integrating demographic characteristics and environmental exposures, this study provides new insights into the health risks associated with climate and pollution, offering evidence for targeted public health interventions. The guideline values for air pollutants, such as PM2.5 (WHO recommended limit: 10 µg/m³ annual mean), O3 (WHO recommended limit: 100 µg/m³ for 8-hour mean), and CO (WHO recommended limit: 10 mg/m³ for 8-hour mean), were referenced to contextualize the levels of pollutants in relation to potential health risks.

The regression analysis conducted across different exposure quartiles showed that in higher exposure quartiles, the association between PM2.5 and disease incidence was stronger, suggesting the importance of considering exposure levels when assessing the health impacts of air pollution.

To further clarify the relationship between PM2.5 exposure levels and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, we conducted a stratified regression analysis across quartiles of PM2.5 concentration. A multivariable Poisson regression model was used, adjusting for covariates including temperature, precipitation, wind speed, SO2, NO2, O3, CO, and seasonal trends.

The results demonstrated that in higher PM2.5 exposure quartiles, the relative risk (RR) for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events increased significantly, while lower quartiles showed a weaker or non-significant association. These findings underscore the importance of exposure stratification in assessing air pollution health effects.The detailed results of the quartile-based regression analysis are presented in Table 14 below.

These results confirm that higher PM2.5 concentrations are associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, especially in the upper quartiles.

Further analysis using the DLNM model showed that the effects of precipitation, average wind speed, maximum wind speed, and SO2 on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases had a lag effect of 25–30 days. Among them, the increase of precipitation and SO2 concentration is harmful to patients, while the increase of wind speed has a protective effect on patients after a lag of 25–30 days.

We found that in Anshun area of Guizhou, when the daily maximum temperature was 0 °C and the lag days were 25–30 days, RR increased significantly to 1.1, indicating that the daily maximum temperature in winter had a significant lag effect on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, which was basically consistent with previous studies. ZarÄ ba et al.34 found that for the onset of stroke, the humidity and temperature of the day and the temperature of the previous day were the main influencing factors. Winter is a stroke-prone season, and the decrease of temperature will increase the risk of stroke. Li et al.35 used the generalized additive model to evaluate the risk factors of acute myocardial infarction, and incorporated weather factors and physiological factors into effective risk indicators for research. They found that minimum temperature, maximum wind speed, and antiplatelet therapy were negatively correlated with the daily incidence of acute myocardial infarction. Through a national study, Ravljen et al.36 found that people over 65 years old with acute coronary syndrome were greatly affected by daily average temperature, while those under 65 years old were more sensitive to air pressure and relative humidity. The study of Tang et al.37 showed that extreme precipitation increased the risk of hospitalization in patients with ischemic stroke, and the single-day and cumulative lag effects continued to day 8 and day 12, respectively.

The interaction between meteorological elements and atmospheric pollutants is very complex, and the current model framework does not fully reflect it38.The interaction between meteorological factors and atmospheric pollutants in different cities has obvious regional characteristics. The local ecological environment, meteorological performance, and the use of air conditioning and heating will affect the exposure patterns and exposure levels of residents. There are differences in the tolerance and sensitivity of local residents to meteorological elements and atmospheric pollutants. A large number of studies have shown that extreme high temperature can increase the death effect of atmospheric particulate matter on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases39.

In the current study, several key factors were considered to assess air quality and its associated health risks. These factors include concentrations of various air pollutants such as PM2.5, NO2, and SO2, as well as meteorological conditions that influence pollution levels. Additionally, demographic factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status were taken into account, as these can influence the vulnerability of populations to air pollution-related health issues.The air quality in the study region is characterized by high concentrations of PM2.5, particularly during certain seasons. These elevated pollution levels have been linked to significant health risks for local populations, especially for vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, and those with pre-existing health conditions. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 and other pollutants has been associated with an increased incidence of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in these communities.

Although the current study primarily focused on the general population in Anshun City and did not specifically stratify the analysis by vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, or individuals with pre-existing health conditions, previous research has demonstrated that these subpopulations exhibit heightened susceptibility to air pollution-related health risks. Studies have shown that elderly individuals and patients with chronic cardiovascular or respiratory conditions are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of long-term exposure to PM2.5 and other pollutants, resulting in a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases42,43. Moreover, children, whose respiratory and cardiovascular systems are still developing, are also more sensitive to environmental hazards, including fine particulate matter and gaseous pollutants such as SO2 and NO244,45.

While our analysis did not directly evaluate the chronic effects of prolonged pollutant exposure, it is noteworthy that long-term exposure to elevated PM2.5 levels has been associated with the progression of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular pathologies, as evidenced by large-scale epidemiological studies conducted globally46,47. Therefore, further research is warranted to examine these associations in Anshun City, focusing on long-term exposure and vulnerable subpopulations to provide more targeted and effective public health recommendations.

The reasons for the differences between the results of this study and other studies may be: (1) The results of the coupling effect of natural differences, social economy, population structure, living habits and other factors. (2) In the data collected in this study, only patients with the main diagnosis of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases were considered. In order to ensure the accuracy of the preliminary diagnosis, the suspected cases are excluded in the statistics, which may lead to information bias and relatively small sample size. This may be one of the reasons why the correlation between meteorological factors such as daily average temperature and the number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular inpatients is not statistically significant. (3) The study area is Anshun City, which belongs to the southern region of China. The climate in this area is mild, and the time of heat and cold is short. The popularity of air conditioning in this area may lead to the change of meteorological factors such as outdoor environmental temperature, which may not be of great significance to residents. This is also one of the possible reasons why the correlation between meteorological factors such as daily average temperature and the number of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in the study area is not statistically significant. (4) In this study, we only considers the overall situation of Anshun area, and does not analyze in detail according to age, gender, etc. Subsequently, similarities and differences can be analyzed for different ages and genders.

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between meteorological air pollutants and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in Anshun City from 2018 to 2022, and drew the following conclusions:

-

(1)

The average daily incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in Anshun City was 0.3 cases/10,000 people. The overall air quality is excellent, and the average AQI is 38.6, which is lower than 50. Although the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in Anshun City has no obvious seasonal characteristics, it is slightly higher in summer than in winter. In contrast, the seasonal variation of environmental meteorological elements is more obvious. The average temperature, precipitation and O3 concentration in summer are higher, while the winter is lower. The pressure and other air pollutants are basically lower in summer and higher in winter.

-

(2)

Through research, it is found that there is a threshold relationship between meteorological air pollutants and the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. When the current ten-day average temperature is 12.4℃, the ten-day average daily maximum temperature is 16.1℃, the ten-day average daily minimum temperature is 10.1℃, the ten-day average precipitation is about 2.7 mm, and the average station pressure is about 855 hPa, the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases is low.

-

(3)

Using the DLNM model analysis, it is found that the daily maximum temperature, precipitation, average wind speed, maximum wind speed and SO2 concentration has a lag effect on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and the lag period is generally 25–30 days. Among them, the increase of precipitation and SO2 concentration has a harmful effect on the population with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, while the increase of average wind speed and maximum wind speed and the decrease of daily average temperature have a protective effect on the population.

These conclusions provide important clues for understanding the impact of meteorological air pollutants on the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and provide a scientific basis for related prevention and intervention measures.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained from the Guizhou Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have signed a confidentiality agreement with the Guizhou Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the availability of these data is limited. These data are used under the current research license and therefore not disclosed. However, with reasonable requirements and permission from the Guizhou Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the author may provide data. If anyone wants to request data from this study, they should contact the author Du Zhengjing.

References

Collaborators, G. B. & D R, F. Global, regional, and National comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390 (10100), 1345–1422 (2017).

Mustafic, H. et al. Main air pollutants and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 307 (7), 713–721 (2012).

Zhou, M. et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 387 (10015), 251–272 (2016).

Knibbs, L. D. et al. The Australian child health and air pollution study (ACHAPS): A National population-based cross-sectional study of long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution, asthma, and lung function. Environ. Int. 120, 394–403 (2018).

Rodríguez-Villamizar, L. A. et al. Short-Term effects of air pollution on respiratory and circulatory morbidity in Colombia 2011⁻2014: A Multi-City, Time-Series analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, 15(8). (2018).

Nhung, N. T. T. et al. Acute effects of ambient air pollution on lower respiratory infections in Hanoi children: an eight-year time series study. Environ. Int. 110, 139–148 (2018).

Zhong, P. et al. Individual-level modifiers of the acute effects of air pollution on mortality in Wuhan, China. Glob Health Res. Policy. 3, 27 (2018).

Zhang Nan, H., Bin, Q., Li, L. & Jifeng, X. Junchang. Research overview of the impact of meteorological factors on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Chin. J. Integr. Med. Cardio-/Cerebrovascuiar Disease, (09): 1193–1196. (2018).

Peng, Y. et al. Report on the study of disease burden in China from 2005 to 2017. Chin. Circulation J. 34 (12), 1145–1154 (2019).

Huang, C. et al. Effects of extreme temperatures on years of life lost for cardiovascular deaths: A time series study in Brisbane, Australia. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 5 (5), 609–614 (2012).

Phosri, A., Sihabut, T. & Jaikanlaya, C. Short-term effects of diurnal temperature range on hospital admission in Bangkok, Thailand. Sci. Total Environ., 717:137202. (2020).

Zhai, G., Qi, J. & Chai, G. Impact of diurnal temperature range on cardiovascular disease hospital admissions among Chinese farmers in Dingxi (the Northwest China). BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21 (1), 252 (2021).

Khanjani, N. & Bahrampour, A. Temperature and cardiovascular and respiratory mortality in desert climate. A case study of Kerman, Iran. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 10 (1), 11 (2013).

Ho, H. C. et al. Spatiotemporal influence of temperature, air quality, and urban environment on cause-specific mortality during hazy days. Environ. Int. 112, 10–22 (2018).

Bo, Q. Yu z.note on urbanization in China:Urban definitions and census data. China Economic Rev. 2014, 30:495–502 .

Medina-ramon M, S. C. H. W. A. R. T. Z. J. & Medicine Temperature,temperature extremes,and mortality:a study of acclimatisation and effect modification in 50 US cities. Occupational Environ. 64(12):827–833 (2007).

Mcmichael A J, Wilkinson P et al. International study of temperature, heat and urban Mortaliy:the‘ISOTHURM’ project. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37(5): 1121–1131

Zanobetti A,Schwartz, J. Temperature and mortality in mine US cities. Epidemology, 19(4):563–570. (2008).

Braga A L F, Z. A. N. O. B. E. T. T. I. A. Schwartz J.The time course of weather-related deaths. Epidemiolgy, 12(6):662–667 (2001).

Schwartz J, Samet J M,Patz & J A. Hospital admissions for heart disease:the effects of temperature and humidity. Epidemiol., 15(6):755–761 (2004).

Kovats R S,Hajat S, Wilkinson, P. & Medicine Contrasting patterns of mortality and hospital admissions during hot weather and heat waves in Greater London, UK. Occupat. Environ. 61(11):893–898 (2004).

Tan Yulong; Yin Ling, Wang, S. & Chen, L. Tan Yuanwen; Kang Yanzhen comparative study on the impact of temperature changes in different regions on ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. J. Meteorol. Environ., (03): 94–99. (2019).

Xie, J. & Wang, X. Wang liming; Qin Yuanming. Analysis of the relationship between recurrence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and meteorological conditions in Changchun City. Jilin Meteorol., (04): 23–25. (2001).

Wang, D. Jiang Guohong; Gu Qing; Zhang Hui; Xu Zhongliang; song guide; Zhang Ying; Shen Chengfeng using time series Poisson regression to analyze the acute impact of air pollutants on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease mortality in Tianjin. Chinese Circulation J., (06): 453–457. (2014).

Song Guixiang; Jiang Lili, Chen, G., Chen, B. & Zhang, Y. Zhao naiqing; Jiang Songhui; Kan Haidong. A time series study on the relationship between atmospheric gaseous pollutants and daily mortality among residents in Shanghai. J. Environ. Health, (05): 390–393. (2006).

Chen, Z., Cui, X. & Wang, B. Hu Yanlin; Dailan; Cao Xueqin; Wang Chunhong; Shi Tingming. Low atmospheric pollution level NO_ A time series study on the impact of death from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in residents. J. Public. Health Prev. Med., (01): 27–31. (2022).

Yang Sixu, P., Li, Y., Xiaofang, Y., Dandan, Z. & Yajie, Z. Yi. Study on the synergistic effect of temperature and PM2.5 on mortality from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [J/OL]. Shanghai J. Preventive Med. https://doi.org/10.19428/j.cnki.sjpm.2023.22790

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Kenward, M. G. Distributed lag nonlinear models. Stat. Med. 29 (21), 2224–2234 (2010).

Yang Jun, O. & Chunquan, D. Distributed lag nonlinear model. Chin. J. Health Stat. 29 (5), 772–773 (2012).

Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Li, T. & Li, Y. Yin Ling; can still govern; Wang Shigong. The impact of heat index on respiratory diseases in Funan region. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition), (01): 134–140. (2019).

Yang, S. Meng Qingtao,Zhou Ningfang,et.al,Study on global high temperature thresholdvalues based on surface observation data. Meteorol. Disaster Reduct. Res. 45(1):10–21

Munzel, T. et al. Effects of gaseous and solid constituents of air pollution on endothelial function. Eur. Heart J. 39 (38), 3543–3550 (2018).

Xu, H. et al. Extreme levels of air pollution associated with changes in biomarkers of atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability and thrombogenicity in healthy adults. Circ. Res. 124 (5), e30–e43 (2019).

Zaręba, K., Lasek-Bal, A. & Student, S. The influence of selected meteorological factors on the prevalence and course of Stroke. Medicina 57 (11), 1216 (2021).

Li, C. Y. et al. Weather impact on acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions with a new model for prediction: A nationwide Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 725419 (2021).

Ravljen, M. et al. Influence of daily individual meteorological parameters on the incidence of acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 11 (11), 11616–11626 (2014).

Tang, C., Liu, X. G. & He, Y. Y. Association between extreme precipitation and ischemic stroke in Hefei, China: hospitalization risk and disease Burden. Sci. Total Environ. 732, 139272 (2020).

Dholakia, H. H. Short term association between ambient air pollution and mortality and modification by temperature in five Indian cities. Atmos. Environ. 99, 168–174 (2014).

CHEN, F. et al. The effects of sulphur dioxide on acute mortality and years of life lost are modified by temperature in Chengdu, China. Sci. Total Environ. 576, 775–784 (2017).

Rivas, I. et al. Association between early life exposure to air pollution and attention. Environ. Health Perspect.. 127 (5), 057002 (2019).

Basagaña, X. et al. Low and high ambient temperatures during pregnancy and birth weight among 624,940 Singleton term births. Environ. Health Perspect. 129 (3), 037001 (2021).

Bell, M. L., Zanobetti, A. & Dominici, F. Who is more affected by Ozone pollution? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180 (1), 15–28 (2014).

Pope, C. A. & Dockery, D. W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 56 (6), 709–742 (2006).

Gauderman, W. J. et al. Association of improved air quality with lung development in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 372 (10), 905–913 (2015).

Trasande, L. & Thurston, G. D. The role of air pollution in asthma and other pediatric morbidities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115 (4), 689–699 (2005).

Miller, K. A. et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (5), 447–458 (2007).

Brook, R. D. et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 121 (21), 2331–2378 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ke Xu were responsible for the study design and data collection; Zhengjing Du、Tao Liu and Chen Yuan conducted data analysis and interpretation; Xiaoling Xia wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, X., Du, Z., Liu, T. et al. The influence of meteorological factors and air pollution on acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in Western Guizhou. Sci Rep 15, 22676 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03611-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03611-6