Abstract

Climate change significantly influences the distribution of parasitic species, posing threats to ecosystems and economies. This study examines the potential range expansion of Loranthus europaeus, a parasitic plant impacting European forestry. We assessed the impact of predicted climate change for 2041–2060 and 2061–2080 using MaxEnt modeling based on current occurrence data of L. europaeus, and the main host plant genus oak Quercus, as well as bioclimatic variables. Our model demonstrated high predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.92). The most important variables for Europe range were range of Quercus genus. Key environmental factors included isothermality (bio3) and mean temperature of wettest quarter (bio8). Under SSP126 and SSP245 scenarios, our results predict significant range expansions into northern and eastern Europe, with increases of 43.5% and 53.9% by 2041–2060. Conversely, southern Europe may see contractions of 16.4–20.6%. Projections for 2061–2080 indicate further expansions up to 65.8% in northern Europe, alongside contractions up to 29.8% in southern regions, including Turkey and Greece.These shifts highlight the influence of climate change on L. europaeus distribution and underscore the need for adaptive management strategies to mitigate potential ecological and economic impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change significantly influences the geographic ranges of plant species, with profound implications for biodiversity conservation1,2,3. Species migration in response to climate change depends on factors such as life history traits and dispersal syndromes4,5. Evidence from pollen and subfossil materials indicates that even after thousands of years, plant species have not fully occupied their potential ranges due to dispersal limitations2,6,7,8. However, current climate change rates pose unprecedented risks of biodiversity loss. Climate change acts as a potent force driving the proliferation of alien and pest species, intensifying ecological disruptions, and presenting formidable challenges to ecosystems globally9,10. Fluctuations in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events create conducive environments for non-native species to establish and spread into new territories10,11. Moreover, climate alterations weaken historical barriers that once constrained the expansion of these species, accelerating their range shifts12.

Recent advancements in climate modeling have forecasted rapid temperature increases alongside a heightened frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts, cold snaps, and heatwaves, coupled with localized reductions in rainfall13. These ongoing shifts in climate dynamics are driving alterations in the geographical ranges of organisms, necessitating adaptations to new environmental conditions. Consequently, these changes are reshaping spatial distributions and compelling species to adjust to novel climatic niches. Projections suggest that many species will undergo distributional shifts towards higher elevations and latitudes in response to escalating temperatures12. Furthermore, climate change is altering the dynamics between plants and their biotic stressors, leading to an expansion in the range of pathogens and pests. This phenomenon increases the vulnerability of forests to ensuing stresses, heightening their susceptibility to disturbances related to climate change14. Trees and forests, known for their long-term functionality, are particularly at risk. Understanding these evolving dynamics is crucial for effective species and habitat management12, as well as for planning future forest management strategies15,16. Many biotic and abiotic factors were not considered significant for forest management17. One such factor is the common mistletoe (Viscum album L.), a semi-parasitic plant whose economic impact as a forest pathogen, particularly among coniferous trees, has been overlooked. Previously, mistletoe was regarded as enhancing forest biodiversity18. However, there is now a notable increase in the presence of V. album in European forests, leading to increasingly severe losses19. Modeling conducted by Walas et al.l19 suggests that the potential range of mistletoe is shifting north-eastward, with mountainous regions experiencing elevational shifts. This expansion of mistletoe presence poses a significant threat to pine-dominated forests, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, potentially accelerating tree dieback.

Another mistletoe species found in Europe is Loranthus europaeus (Jacq.) (Santalales: Loranthaceae)20. This mistletoe parasitizes various forest tree species but poses a particular risk to oaks21. Currently, L. europaeus is widely distributed across southwestern Europe, southern Russia, Anatolia, Iran, Iraq, and isolated areas in Asia Minor and Ukraine22,23,24. Its presence has also been confirmed in Germany, particularly in relict sites in Saxony where favourable warm air currents from the Elbe valley aid its establishment25. It has been observed mainly on various species from oak Quercus spp. L. genus and less frequently on sweet chestnut Castanea sativa Mill., but also has been occasionally found on other woody plants like Acer campestre L., Betula pendula Roth., Carpinus betulus L., Colutea arborescens L., Crataegus monogyna Jacq., Fagus sylvatica L., Fraxinus ornus L., Prunus spinosa L., Robinia pseudoacacia L. and Olea europaea L21,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Research by Kubov et al.l35 highlights that the invasion of L. europaeus poses a serious threat to the physiology and growth of sessile oaks (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.). Infected trees show a 20–30% reduction in growth, increased crown dieback, and heightened susceptibility to pathogens, particularly in older stands, thereby compromising forest durability and productivity amidst changing climates. Forest protection procedures against L. europaeus are currently undefined due to the plant’s specificity, population dynamics influenced by climate change, and its interactions with birds. Numerous bird species, such as the mistle thrush (Turdus viscivorus L.)36, the Bohemian waxwing (Bombycilla garullus L.)37, and the Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius L.)38, feed on its fruit and aid in its dispersal over long distances34,39. For instance, Slovakia lacks specific protection measures and emphasizes the need for ongoing monitoring35 Understanding the phenology of L. europaeus is crucial for its control40, especially given potential shifts in its flowering and fruiting patterns due to climate change, impacting animal migrations and activities41. Climate changes could potentially expand the distribution of mistletoe32,42,43, possibly doubling its population within 16 years due to early maturation—fruiting as early as 3 years old44. Frost days per year, with an isotherm of 110 days, may limit mistletoe expansion in the Czech Republic and Moravia45, with late spring frosts also posing constraints46. Loranthus europaeus currently thrives in southeastern Europe due to its high heat requirements, but its northward migration is anticipated along valleys such as the Danube, Inn, and Elbe with rising temperatures47.

Despite the comprehensive documentation available regarding the presence and abundance of L. europaeus, primarily derived from short-term studies48,49,50,51,52, as well as predictions of its local spread32,34,43,49,53,54, there remains a notable absence of research examining the potential future Eurasian range of this species. Such studies are imperative to understand the dynamics of its spread, especially concerning forests vulnerable to this semi-parasitic plant, particularly in the context of climate change. Therefore, we hypothesized that this species could potentially benefit from projected climate changes and might pose a future threat to forest health in Europe. Hence, the objective of this analysis was twofold: firstly, to assess the current and projected future occurrence range of L. europaeus in Europe during the 2040–2060 and 2060–2080 periods, and secondly, to underscore the urgent need for predictive modeling to inform effective forest management strategies aimed at mitigating the adverse impacts of this species, exacerbated by changing climatic conditions.

Materials and methods

Occurrence data

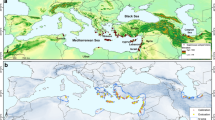

To model the potential distribution of L. europaeus, we collected occurrence data from various sources (A.1.), including field surveys, herbarium and literature records, and online databases such as GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). The dataset was curated to remove duplicates and ensure accuracy, resulting in a comprehensive dataset of georeferenced occurrence points across Europe (Fig. 1). This dataset provided the foundation for modeling the species’ current and future distribution patterns. In total, we collected 997 distribution records for L. europaeus and 49,684 for Quercus genus, each with geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude), and entered them into a spatially referenced database.

To reduce sampling bias caused by uneven data density across regions where some areas are over-sampled and others under-sampled56, we retained only one randomly selected occurrence per species within each 0.25° grid cell. This approach, commonly used in previous studies57,58,59, helped ensure a more balanced spatial representation of species and regions in the dataset compared to the original data input.Following resampling, the dataset comprised 2631 occurrences for Quercus spp. and 290 for L. europaeus, which were deemed sufficient for MaxEnt analyses60. The analyses covered the area of Europe, limited by longitude from − 10° to 45° and latitude from 33° to 72°. Utilizing presence-only data, we employed the MaxEnt algorithm to model species distributions. This method relies on pseudoabsences instead of absence data, with predictions based on comparing presence patterns to background data61,62. By including background points, the model becomes more conservative, requiring stronger signals to counteract the presence of background points61.

Predictors of the potential distribution

Initially, we employed all 19 bioclimatic variables to model the global distribution of Quercus species as described by Dyderski et al.l58. In the context of large-scale species distribution modeling, it is deemed appropriate to incorporate all bioclimatic variables63,64,65. Subsequently, for L. europaeus, we utilized a reduced set of bioclimatic variables following an assessment of collinearity among them. Multicollinearity was mitigated by eliminating variables exceeding collinearity thresholds of |r| > 0.7. A total of five bioclimatic variables, along with the predicted distribution of L. europaeus, were considered for model development (Table 1). The raster resolution utilized in the analyses was set at 2.5’. These bioclimatic variables were sourced from the WorldClim 2.1 database (www.worldclim.org), providing high-resolution climate data necessary for accurate species distribution modeling66.

Potential niche modeling

We used MaxEnt (Maximum Entropy Modeling) to predict the current and future potential distribution of L. europaeus. MaxEnt is a widely used method for species distribution modeling due to its robustness in handling presence-only data and its ability to provide accurate predictions. The analysis was conducted using default settings, with 80% of resampled data points allocated to the training set and 20% to the validation set. For each species, we selected 10,000 pseudoabsences (background points). The quality of the MaxEnt model was assessed using the AUC (area under the receiver operator curve), which measures the overlap between true and predicted occurrences. The MaxEnt analysis generated raster maps indicating the probability of each species occurring in each grid cell. Threshold values for presence/absence maps were calculated to optimize sensitivity (proportion of true positives) and specificity (proportion of true negatives), aiming to balance false negatives and false positives67. Additionally, MaxEnt provided the percentage contribution of variables to the potential distribution model.

Data analysis was performed using R software (R Core Team,68, with MaxEnt models developed using the ‘dismo’ package69 For geospatial analyses and data processing, we utilized the ‘raster’70 and ‘sf’71 packages. The potential range saturation, indicating the proportion of sampled points and grid cells suitable for species occurrence, was calculated as a result.

Predicted changes in species distributions

Our future climate projections are derived from the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report and the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) elucidated by Riahi et al. (2017). The utilization of SSPs serves to account for uncertainties in potential mitigation strategies. Specifically, we employed four SSPs: SSP126 (representing sustainability, akin to RCP2.6), SSP245 (illustrating a moderate, middle-of-the-road scenario akin to RCP4.5), SSP370 (characterizing regional rivalry, absent in the 5th report), and SSP485 (depicting fossil fuel-based development or business-as-usual, akin to RCP8.5). Across these SSPs, data from four global circulation models (GCMs) were incorporated: IPSL-CM6A-LR (France), MRI-ESM2-0 (Japan), CanESM5 (Canada), and BCC-CSM2-MR (China). Our predictions were based on maps corresponding to future climate scenarios. To mitigate uncertainty associated with particular General Circulation Models (GCMs), we averaged the predicted climatic suitability for each Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) across the four GCMs under study72,73. By applying threshold values (true/false) on the maps, we calculated potential distribution shifts by adjusting values from 1 to 2. Subsequently, we performed the following calculation to estimate potential range changes: (i) areas unsuitable for colonization in all climate scenarios (0–2*0 = 0); (ii) areas optimal for colonization under future climatic conditions (0–2*1=-2); (iii) currently optimal areas projected to be lost in the future (1–2*0 = 1); (iv) currently optimal areas expected to remain suitable in the future (1–2*1=-1)59.

Results

The Quercus genus potential distribution had moderate performance expressed by AUC 0.81 predicted for Europe assessed using a validation dataset. The threshold of occurrence probability, assessed as the point with the highest sum of sensitivity and specificity, was at 0.57. The most important variables for Quercus genus in Europe were bio7 (45.6%), bio1 (20.9%) and bio4 (15.8%) (B. 1.).

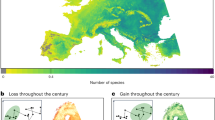

The L. europaeus potential distribution had good performance expressed by AUC 0.92 predicted for Europe assessed using a validation dataset. The threshold of occurrence probability, assessed as the point with the highest sum of sensitivity and specificity, was at 0.37. The most important variables for Europe range of L. europaeus were bio3 (41.2%), probability of occurrence Quercus ssp. (30.5%) and bio8 (20.5%). The rest bioclimatic variables explain in total 7.8% (bio15–4.7%, bio18–1.6%, bio19–1.5%). Our analysis uncovered that although the majority of current L. europaeus habitats, notably in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Austria, and Italy, are situated within favourable climatic conditions (Fig. 2). Notably, the Poland, east Germany, Slovakia, Denmark, the southern part of Sweden and some eastern part of Belarus, and Ukraine also represent suitable environments for L. europaeus expansion. Conversely, areas in far northern-east Europe, Portugal, southern Spain, southern Turkey, and Greece fall outside the range of climatic suitability.

Under the whole scenario, the species are expected to remain present in most regions during period 2041–2060 (Fig. 3) and 2061–2080 (Fig. 4). Predictions for the 2041–2060 scenarios of SSP126 and SSP245 indicate a range expansion of 43.5% and 53.9% (Fig. 5), respectively, in northern Europe (northern Poland, and Baltic state), and central and east part of Europe, especially Ukraine and Romania (Fig. 3). Conversely, there is a projected range contraction of 16.4% for SSP126 and 20.6% for SSP585 in the southern part of Europe, particularly in the Balkans and Italy, as well as in the southern regions of Sweden (Fig. 3). Projection for 2061–2080 timeline indicated significant range expansion from 46.3% for SSP126 to 65.8% for SSP585 is anticipated (Fig. 5), particularly in northern Europe, including Finland and Russia, and in the northeast part of Europe, notably in northern France and the UK (Fig. 4). Concurrently, range contraction under SSP126 to SSP585 scenarios is estimated to be between 15.9 and 29.8% (Fig. 5), concentrating in the southern parts of Europe, such as Italy, the Balkans, and extending into Turkey (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Our study presents potential species distribution range for the ecologically and economically significant parasite Loranthus europaeus. Previous research30,32,40,54,74,75 has highlighted its impact, but our results represent the first comprehensive modeling of its distribution across the entire European range. Loranthus europaeus, known for its westward migration to Europe, currently thrives in Central Asia, Anatolia, South Russia, and Southwestern Europe22. Our findings indicate that L. europaeus could potentially expand further, which has significant implications for local ecosystems and economies. Its impact on the forestry economy is particularly notable, as it can cause dieback in host tree species, leading to substantial economic losses. The dieback of host trees not only reduces timber yield but also affects biodiversity and forest health, underscoring the need for effective management strategies to mitigate the spread and impact of this parasitic species. The extent and impact of damage caused by L. europaeus have been evaluated locally in various regions. For example, in Iran, up to 78% of forest trees are affected by this mistletoe54. In Slovakia, during the 1980s, mistletoe infestation covered 34% of oak forest areas74. In Kosovo, the presence of L. europaeus in sessile oak stands reached 14.65%33. In Croatia, around 7% of oak populations were infested in 2002/200331, while in Turkey, only 2.3% of sessile oaks were affected31, in Podyjí National Park, Czech Republic (2011–2015) 6.9–9.7% of Q. petraea shoots were colonized by L. europaeus53. Sayad et al.52 reported that the infection rate in the oak forests in Zagros in Irak was 23%. Additionally, Ilić76 indicates that L. europaeus has become a new problem in the management of oak stands, a situation exacerbated by climate change in the Motajica Mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The results of our research, alongside the aforementioned studies, demonstrate that the occurrence of L. europaeus is not only a local issue. We anticipate an expansion in the range of this species, which underscores the growing concern.

The distribution of L. europaeus is influenced by more than just the presence of its host; other factors can also limit its occurrence. Our results indicate that environmental conditions are likely the most significant factors shaping the range of L. europaeus. The climatic variables with the highest impact on potential distribution models for L. europaeus are the mean temperature of the wettest quarter (bio8), isothermality (bio3), and host plant distribution. MaxEnt modeling, previously used by Walas et al.l19 to predict the range of another parasitic plant, Viscum album, suggests that temperature is the key variable, while precipitation is less important. This is likely because rainfall has an indirect impact, given that L. europaeus, like V. album, extracts water from the xylem of its host. This underscores temperature as the most critical atmospheric factor influencing the distribution of L. europaeus. The anticipated increase in average annual temperature is predicted to facilitate the further spread of this species in the coming decades47,77. The northern limit of the geographical distribution of mistletoe has been primarily influenced by climatic conditions, particularly winter and spring frosts46. According to Rejmánek45, the average number of frosty days per year is a limiting factor for the occurrence of L. europaeus, with the isotherm of 110 frosty days per year restricting its spread.

Currently, the actual range of L. europaeus is considerably smaller than that of its primary host, Quercus sp. in Europe. Numerous examples demonstrate that the presence of L. europaeus in forests poses a significant threat to forest durability and productivity in the context of climate change. This species, akin to Viscum album subsp. austriacum, likely survived the glacial period in the Iberian Peninsula and subsequently recolonized other parts of Europe from this region19. However, there remains potential for the expansion of L. europaeus, as its current estimated range exceeds its observed distribution. Our model for the occurrence of L. europaeus resembles the predicted range of V. album subsp. austriacum as described by Walas et al.l19. The reduced range of L. europaeus in the north may be attributed to its heightened sensitivity to lower temperatures and specific terrain features, such as those along the borders of Poland and Slovakia, and Poland and the Czech Republic. The harsh climates of the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains could also act as barriers to the spread of L. europaeus. The anticipated distribution patterns are derived from correlation models based on environmental variables61,78, which may not always directly correspond to the physiology and ecology of the species under study66. Bioclimatic variables and their projections do not encompass extreme weather events, such as late spring frosts or summer droughts, whose occurrence, albeit unpredictable, is on the rise due to climate change. These events have the potential to impede the reproductive success of plants by causing damage to their generative organs, resulting in decreased fitness and heightened mortality rates, a phenomenon more extensively documented in trees79,80,81,82.

Future projections indicate that populations of Loranthus europaeus in the southernmost regions of the Balkan Peninsula may face extinction; however, the decline in suitability is projected to be less rapid in southwestern Europe. This variation can be attributed to the significant influence of continentalism on the distribution of this subspecies. Concurrently, the potential range is expected to remain relatively stable in the central part of Europe, with some countries such as Belarus, Germany, and Poland likely experiencing even higher suitability than at present, possibly due to anticipated increases in winter temperatures. Our findings suggest that akin to V. album subsp. austriacum, L. europaeus could become a substantial factor negatively impacting forests in Central Europe19. Sayad et al.l52 have a similar opinion, claiming that as a result of ongoing climate change and fragmentation of tree stands, L. europaeus has the potential to be more numerous and widespread in the forests of western Iran (Zagros).

Under current conditions, L. europaeus already presents a significant challenge in oak stands and chestnut plantations51, and this problem may be exacerbated by climate change, which could weaken host trees19. The presence of L. europaeus notably exacerbates tree stress during dry summer seasons, as infestation by this species reduces water and mineral nutrient availability. Mistletoe exhibits higher stomatal conductance and transpiration rates than the host tree, leading to a notable loss of water and affecting tree growth83,84,85. Affected hosts exhibit a 20–30% reduction in growth due to L. europaeus infestation75. This issue primarily affects older stands32. Additionally, Dolezal and Klimešová79 observed over a 50% increase in crown dieback in pedunculate oak Quercus robur L. trees with more than five L. europaeus individuals per tree.

Loranthus europaeus may be a primary factor predisposing oak trees, in particular, to the adverse effects of drought, initiating a decline process in which additional stressors, such as pests and diseases, could eventually lead to tree mortality. Mistletoe weakens oaks, resulting in gradual crown decline, especially in stands over 50 years old, rendering them more vulnerable to pathogens such as Armillaria spp. (Fr.) Staude or Ophiostoma spp. Syd. & P. Syd86. The potential range of the L. europaeus may also be influenced by human activity. Potentially, an increase in the abundance of L. europaeus is associated with the planting of its hosts. For example, in Poland, the reconstruction of coniferous (pine) forests in favour of deciduous species, such as oaks87,88,89, may facilitate the spread of this mistletoe. Additionally, the Common Agricultural Policy promotes the introduction of buffer strip and the creation of agroforestry systems90,91 with a dominant share of deciduous trees, including those species susceptible to L. europaeus. All these activities will increase the availability of host plants, which is a key factor in the distribution of L. europaeus.

Furthermore, the condition of oak stands in Poland has been deteriorating year by year. Oak decline, a complex process leading to increased mortality of this species, has been observed in Europe for many years. Previous studies suggest that climate conditions, especially drought, may be one of the most important factors triggering this phenomenon92. On the other hand, it is forecasted that the range of many oak species will change, with the range of many species expanding northward93, which is also confirmed by the results of our modeling of the range of trees belonging to the Quercus genus. Climate change will also favour the development of populations of the alien oak species in Europe, Quercus rubra L94, which is also susceptible to L. europaeus. The weakening of native oak populations, changes in their range, and the increase in the area of alien species may promote the expansion of the range of L. europaeus northward.

Recommendations

The findings presented in this study provide insight into the expected changes in the distribution of L. europaeus. The potential range of L. europaeus is projected to shift northward and to higher altitudes in mountainous regions of Europe. This shift may have detrimental effects on forest ecosystems in Central and Eastern Europe, potentially accelerating the decline of deciduous tree species, mainly from genus Quercus. Conversely, southern populations of mistletoe may face local extinction. These projected range changes are primarily informed by climatic data; however, it is important to note that other factors not included in modeling such as seed dispersal by birds and pollination by insects also influence mistletoe spread. Nonetheless, our understanding of L. europaeus seed dispersal and germination remains limited, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Data availability

The research was based partially on the following datasets from the GBIF database: GBIF.org (3 March 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.f3m9gq.

References

Giesecke, T., Hickler, T., Kunkel, T., Sykes, M. T. & Bradshaw, R. H. W. Towards an Understanding of the holocene distribution of Fagus sylvatica L. J. Biogeogr. 34, 118–131 (2007).

Giesecke, T., Brewer, S., Finsinger, W., Leydet, M. & Bradshaw, R. H. W. Patterns and dynamics of European vegetation change over the last 15,000 years. J. Biogeogr. 44, 1441–1456 (2017).

Seppä, H. et al. Trees tracking a warmer climate: the holocene range shift of Hazel (Corylus avellana) in Northern Europe. Holocene 25, 53–63 (2015).

Peterken, G. F. A method for assessing woodland flora for conservation using indicator species. Biol. Conserv. 6, 239–245 (1974).

Sádlo, J., Chytrý, M., Pergl, J. & Pyšek, P. Plant dispersal strategies. Preslia 90, 1–22 (2018).

Skov, F. & Svenning, J. Potential impact of Climatic change on the distribution of forest herbs in Europe. Ecography 27, 366–380 (2004).

Svenning, J. & Skov, F. Limited filling of the potential range in European tree species. Ecol. Lett. 7, 565–573 (2004).

Svenning, J. & Skov, F. Could the tree diversity pattern in Europe be generated by postglacial dispersal limitation? Ecol. Lett. 10, 453–460 (2007).

Pörtner, H. O. et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 380 (2023).

Villa, F., Cimatti, M. & Di Marco, M. Biodiversity and environmental impact from climate change: causes and consequences. in Biodiversity Laws, Policies and Science in Europe, the United States and China. Springer Nature, 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56218-1_6 (2024).

Pfenning-Butterworth, A. et al. Interconnecting global threats: climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet. Health. 8, e270–e283 (2024).

Rubenstein, M. A. et al. Climate change and the global redistribution of biodiversity: substantial variation in empirical support for expected range shifts. Environ. Evid. 12, 7 (2023).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report : Longer Report.

Sturrock, R. N. et al. Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathology 60, 133–149 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02406.x

Chakraborty, D., Móricz, N., Rasztovits, E., Dobor, L. & Schueler, S. Provisioning forest and conservation science with high-resolution maps of potential distribution of major European tree species under climate change. Ann Sci 78 (2021).

Dyderski, M. K. & Jagodziński, A. M. Seedling survival of Prunus serotina Ehrh., Quercus rubra L. and Robinia pseudoacacia L. in temperate forests of Western Poland. For. Ecol. Manag. 450, (2019).

Trumbore, S., Brando, P. & Hartmann, H. Forest Health and Global Change. https://www.science.org (2015)

Iszkulo, G. et al. Mistletoe as a threat to the health state of coniferous forest. Sylwan 164, 226–236 (2020).

Walas, Ł. et al. The future of Viscum album L. in Europe will be shaped by temperature and host availability. Sci. Rep. 12, 17072 (2022).

Nickrent, D. L. Santalales (Including Mistletoes). In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0003714.pub2 (2011).

Mostaghimi, F., Seyedi, N., Banj Shafiei, A. & Correia, O. How do leaf carbon and nitrogen contents of oak hosts affect the heterotrophic level of Loranthus Europaeus?? Insights from stable isotope ecophysiology assays. Ecol. Indic. 125 (2021).

Shavvon, R. S., Mehrvarz, S. S. & Golmohammadi, N. Evidence from micromorphology and gross morphology of the genus Loranthus (Loranthaceae) in Iran. Turk. J. Bot. 36, 655–666 (2012).

Glatzel, G. et al. Foliar habit in mistletoe–host associations. Botany 95, 219–229 (2017).

Krasylenko, Y. A., Gleb, R. Y. & Volutsa, O. D. Loranthus Europaeus (Loranthaceae) in Ukraine: an overview of distribution patterns and hosts. Ukr. Bot. J. 76, 406–417 (2019).

Hempel, W. Die verbreitung der Wildwachsenden Gehölze in Sachsen. Gleditschia 7, 43–72 (1979).

Bartha, D. Loranthus Europaeus JACQ.-A Felsőoktatási Rendszer K + F + I Szerepvállalásának növelése intelligens Szakosodás Által Sopronban És Szombathelyen view project https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2020.2560 (2007).

Bratanova-Doncheva, S., Mirtchev, S. & Lyubenova, M. Dendrochronological investigation of mistletoe growth impact (Loranthus Europaeus L.) on European chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in South West Bulgaria. Acta Hort. 693, 367–370 (2005).

Elias, P. K Výskytu Imelovcovitých (Loranthaceae) Na Slovensku. The Occurrence of Loranthaceae in Slovakia https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315669450 (1985).

Eliáš, P. Hostiteľské dreviny Imelovcovitých (Loranthaceae) Na Slovensku host Woody species of mistletoes (Loranthaceae) in Slovakia. Bull. Slov. Bot. Spol.. 24, 175–180 (2002).

Idžojtić, M. et al. Žuta Imela (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq.) i Bijela Imela (Viscum album L.) Na Području uprave Šuma Podružnice Bjelovar. Sumar. List. 130, 101–111 (2006).

Kumbasli, M. et al. Hosts and distribution of yellow mistletoe (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq. (Loranthaceae)) on Northern Strandjas oak Forests-Turkey. Sci. Res. Essays. 6, 2970–2975 (2011).

Millaku, F. & Krasniqi, E. The Spread and the Infection Frecuency of the Gollak (Kosovo) Forest with the Species Hemipariastic Mistletoe (Loranthus Europa… View Project Bioaccumulation and Translocation of Major and Trace Metals from Various Plants in the Territory of Kosovo View Project (2011).

Üstüner, T. Türkiye’nin Doğu Akdeniz ve İç Anadolu Bölgeler’inde görülen Yarı Parazit Bitki Türlerin Konakları ve Simptomlarının Araştırılması. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Doğa Bilimleri Dergisi. https://doi.org/10.18016/ksudobil.350489 (2018).

Zebec, M. & Idojtić, M. Hosts and distribution of yellow mistletoe, Loranthus Europaeus Jacq. In Croatia. Hladnikia 19, 41–46 (2006).

Kubov, M. et al. Drought or severe drought?? Hemiparasitic yellow mistletoe (Loranthus europaeus) amplifies drought? stress in sessile oak trees (Quercus petraea) by altering water status and physiological responses. Water (Basel). 12, 2985 (2020).

Beres, I. & Ardelean, G. Sturzii (Genul turdus) în ornitocenozele din depresiunea maramureş. https://biblioteca-digitala.ro (2002).

Schröpfer, L., Hudec, K. & Vačkař, J. Invaze Brkoslava Severního (Bombycilla garrulus) Na Území České republiky V Zimě 2008/09. Sylvia 46, 23–40 (2010).

Gelter, H. P. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. VI. Warblers Stanley Cramp The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. VII. Flycatchers to Shrikes Stanley Cramp C. M. Perrins. Auk 111, 247–249 (1994).

Glatzel, G. & Geils, B. W. Mistletoe ecophysiology: Host-parasite interactions. Botany 87, 10–15 https://doi.org/10.1139/B08-096 (2009).

Hosseini, A. IPA-Under creative commons license 3.0 new mechanical methods and treatments for controlling of leafy mistletoe (Loranthus Europaeus jacq.) on Persian oak trees (Quercus persica). Int J. Environ. Sci 5 (2015).

Fontúrbel, F. E. Mistletoes in a Changing World: A Premonition of a Non-Analog Future? www.nrcresearchpress.com (2020).

Ebermann, R. & Lickl, E. The posible role of peroxidase isoenzymes in the infection of english oak by Loranthus Europaeus. Phytopathology 75, 1102–1104 (1985).

Rozkošný, J. et al. Poloparazitická Rastlina imelovec Európsky (Loranthus Europaeus jacq) a Kvantifikácia Jeho Vplyvu Na Rast a fyziologické procesy Dubov Na LS Duchonka. Acta Fac. For. Zvolen. 61, 7–20 (2019).

Kubíček, J. & Martinková, M. Relationship between host and his hemiparasite. In Vliv abiotických a biotických stresorů na vlastnosti rostlin. ČZU in Prague (2010).

Rejmánek, M. Loranthus Europaeus L. ve Východních Čechách a Zákonitosti Jehorozšíření V Československu. Zprávy České Bot. Spol.. 4, 15–20 (1969).

Eliáš, P. Úhyn Imelovca (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq.) Na Severnej Hranici Rozšírenia V Európe: Slovensko. In Dreviny V Mestskom Prostredí a V Krajine. Aktualne Trendy Dendrologického Výskumu a Praxe. Slovak University of Agriculture, Nitra, 1–3 (2007).

Schmidt, O. Die Eichenriemenblume – bald Auch in Bayern? LWF Aktuell. 72, 33–33 (2009).

Ahmed, S. H. & Rocha, J. B. Antioxidant properties of water extracts for the Iraqi plants Phoenix dactylifera, Loranthus Europeas, Zingiber officinalis and Citrus Aurantifolia. Mod. Appl. Sci. 3 (2009).

Eliáš, P. Ecophysiological, population-biological and production-ecological studies of yellow mistletoe (Loranthus europaeus JACQ.) in an oak-hornbeam forest (Brief Survey). In adaptabilita a rastová vitalita drevín v zmenených podmienkach prostrediatechnická Univerzita vo Zvolene Technická Univerzita vo Zvolene, Zvolen, 28–38 (2020).

Idžojtićđ, M., Pernarč, R., Lisjakč, Z., Zdelarč, H. & Ancić’, M. Hosts of yellow mistletoe (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq.) and intensity of infestation on the area of the forest administration Požega. Šumarski List. Br. 129, 3–17 (2005).

Lushaj, B. M. & Lushaj, A. B. Lisbon,. The infection of yellow mistletoe on the sweet chestnut of Albania. In 28th International Horticultural Congress (2010).

Sayad, E., Boshkar, E. & Gholami, S. Different role of host and habitat features in determining Spatial distribution of mistletoe infection. Ecol. Manag. 384, 323–330 (2017).

Kubíček, J., Špinlerová, Z., Michalko, R., Vrška, T. & Matula, R. Temporal dynamics and size effects of mistletoe (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq.) infection in an oak forest. Austrian J. For. Sci. 135, 119–135 (2018).

Saraj, B. S., Kiadaliri, H., Kafaki, S. B. & Akhavan, R. Spatial variability of forest infection with yellow mistletoe (Loranthus europaeus) in Zagros forests of Iran using IDW and kriging methods. Cumhuriyet Univ. Fac. Sci. Sci. J. (CSJ). 36, 1782–1793 (2015).

Muller, K. Świat Roślinny. Dzieło Poświęcone Miłośnikom Przyrody (Drukarnia ‘Czasu’ Kirchmayera, 1867).

Rocchini, D. & Garzon-Lopez, C. X. Cartograms tool to represent Spatial uncertainty in species distribution. Res. Ideas Outcomes 3 (2017).

Anibaba, Q. A., Dyderski, M. K. & Jagodziński, A. M. Predicted range shifts of invasive giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 825, 154053 (2022).

Dyderski, M. K., Paź, S., Frelich, L. E. & Jagodziński, A. M. How much does climate change threaten European forest tree species distributions? Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 1150–1163 (2018).

Puchałka, R. et al. Black locust (Robinia Pseudoacacia L.) range contraction and expansion in Europe under changing climate. Glob. Chang. Biol. 27, 1587–1600 (2021).

van Proosdij, A. S. J., Sosef, M. S. M., Wieringa, J. J. & Raes, N. Minimum required number of specimen records to develop accurate species distribution models. Ecography 39, 542–552 (2016).

Elith, J. et al. A statistical explanation of maxent for ecologists. Divers. Distrib. 17, 43–57 (2011).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Modell. 190, 231–259 (2006).

Booth, T. H. Why Understanding the pioneering and continuing contributions of < scp > bioclim to species distribution modelling is important. Austral. Ecol. 43, 852–860 (2018).

Booth, T. H., Nix, H. A., Busby, J. R. & Hutchinson, M. F. <scp > bioclim: the first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and relevance to most current < scp > maxent studies</scp >. Divers. Distrib. 20, 1–9 (2014).

O’donnell, M. S. & Ignizio, D. A. Bioclimatic Predictors for Supporting Ecological Applications in the Conterminous United States Data Series. http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod (2012).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km Spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Fielding, A. H. & Bell, J. F. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environ. Conserv. 24, 38–49 (1997).

R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ (2022).

Hijmans, R. J., Phillips, S., Leathwick, J. & Elith, J. Species Distribution Modeling. https://github.com/rspatial/dismo/issues/ (2020).

Hijmans, R. J. et al. raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. https://rspatial.org/raster (2020).

Pebesma, E. Simple features for R: standardized support for Spatial vector data. R J. 10, 439 (2018).

Goberville, E., Beaugrand, G., Hautekèete, N., Piquot, Y. & Luczak, C. Uncertainties in the projection of species distributions related to general circulation models. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1100–1116 (2015).

Thuiller, W., Guéguen, M., Renaud, J., Karger, D. N. & Zimmermann, N. E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 10, 1446 (2019).

Elias, P. Quantitative ecological analysis of a mistletoe Loranthus Europaeus Jacq. Population in an oak-hornbeam forest: discrete unit approach. Ekol. Bratisl.. 7, 3–17 (1988).

Janssen, T. & Wulf, A. Zur Bedeutung Von Misteln Im Forstschutz Ein Vergleich Nordamerikanischer Und Europäischer Arten: Schaden, Kontrolle, Gefahrenpotential Und Quarantäneaspekte Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung Der Zwergmistelgattung Arceuthobium = On the Significance of Mistletoes for Forest Protection Parey Buch, 369 (1999).

Ilić, N. Sušenje hrasta kitnjaka [Quercus petraea (Mattuschka) Lieblein] i pojava imele loranthus europaeus jacq. Na planini motajici Decline of Sessile Oak [Quercus petraea (Mattuschka) Lieblein] and Occurrence of the Mistletoe Loranthus europaeus Jacq. on Mountain Motajica. (2009).

Aprent, R. Ein beitrag Zur aktuellen verbreitung von Loranthus Europaeus in der Steiermark. Joannea Bot. 14 (2017).

Phillips, S. J., Dudík, M. & Schapire, R. E. A maximum entropy approach to species distribution modeling. in Twenty-first international conference on Machine learning - ICML ’04 ACM Press, New York, USA, 83 https://doi.org/10.1145/1015330.1015412 (2004).

Dolezal, J. & Klimešová, J. Oak decline in Southern Moravia: the association between climate change and early and late wood formation in Oaks. Preslia 82, 289–306 (2010).

Klisz, M. et al. Coping with central European climate – xylem adjustment in seven non-native conifer tree species. Dendrobiology 88, 105–123 (2022).

Sangüesa-Barreda, G. et al. Warmer springs have increased the frequency and extension of late-frost defoliations in Southern European Beech forests. Sci. Total Environ. 775, 145860 (2021).

Zohner, C. M. et al. Late-spring frost risk between 1959 and 2017 decreased in North America but increased in Europe and Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 12192–12200 (2020).

Glatzel, G. Mineral nutrition and water relations of hemiparasitic mistletoes: a question of partitioning. Experiments with Loranthus Europaeus on Quercus petraea and Quercus robur. Oecologia 56, 193–201 (1983).

Schulze, E. D., Turner, N. C. & Glatzel, G. Carbon, water and nutrient relations of two mistletoes and their hosts: A hypothesis. Plant. Cell. Environ. 7, 293–299 (1984).

Ullmann, I. et al. Diurnal courses of leaf conductance and transpiration of mistletoes and their hosts in central Australia. Oecologia 67, 577–587 (1985).

Treštić, T., Dautbašić, M. & Mujezinović, O. Uticaj Hrastove Imele (Loranthus Europaeus Jacq.) Na Stabilnost Sastojina Hrasta Kitnjaka. Rad. Šumar. Fak. Univ. U Sarajev. 36, 87–93 (2006).

Andrzejczyk, T., Dzwonkowski, M., Pawłowski, M. & Działak, R. Effect of lateral shelter on a height growth of sessile oak (Quercus petraea) and common Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) in young growth phase. Sylwan 158, 723–732 (2014).

Andrzejczyk, T. & Sewerniak, P. Gleby i Siedliska Drzewostanów Nasiennych Dębu Szypułkowego (Quercus robur) i Dębu Bezszypułkowego (Q. petraea) W Polsce. Sylwan 160, 674–683 (2016).

Dyrekcja Generalna Lasów Państwowych. Raport o stanie lasów w polsce 2022 https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/informacje/publikacje/informacje-statystyczne-i-raporty/raport-o-stanie-lasow (2023).

Baranowska, M., Korzeniewicz, R., Kończak, S. & Janik, Ł. Ziemkowska M. Gatunki inwazyjne W Zadrzewieniach Na Przykładzie Czeremchy Amerykańskiej. Zag. Doradz. Rol.. 3, 48–63 (2022).

Czarnecka, A. & Rędzińska, K. Wprowadzanie Zadrzewień Śródpolnych Jako Elementów Zielonej infrastruktury Obszarów Wiejskich W Scaleniach Gruntów. Prz. Geodezy. 1, 14–19 (2022).

Tulik, M. & Bijak, S. Are Climatic factors responsible for the process of oak decline in Poland? Dendrochronologia (Verona). 38, 18–25 (2016).

Mauri, A. et al. EU-Trees4F, a dataset on the future distribution of European tree species. Sci. Data. 9, 37 (2022).

Puchałka, R. et al. Forest herb species with similar European geographic ranges May respond differently to climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 905, 167303 (2023).

Funding

The publication was financed by: the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education as part of the Strategy of the Poznan University of Life Sciences for 2024–2026 in the field of improving scientific research and development work in priority research areas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marlena Baranowska: Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Original Draft. Adrian Łukowski: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft. Robert Korzeniewicz: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Wojciech Kowalkowski: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Łukasz Dylewski: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baranowska, M., Łukowski, A., Korzeniewicz, R. et al. Predicting parasitic plants Loranthus Europaeus range shifts in response to climate change. Sci Rep 15, 18932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03631-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03631-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The effect of Loranthus europaeus Jacq. on certain morphological and chemical properties of Quercus infectoria G.Olivier wood

Wood Science and Technology (2026)