Abstract

This study presents an enhanced YOLOv8n framework for wind turbine surface damage detection, achieving 83.9% mAP@0.5 on the DTU dataset—a 2.3% improvement over baseline models. The architecture replaces standard convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions (DWConv) to optimize computational efficiency without compromising detection accuracy. The C2f module is restructured by integrating MobileNetV2’s MBConv blocks with efficient channel attention (ECA), which improves gradient flow and enhances discriminative feature extraction for sub-pixel defects. Furthermore, a newly added P2 detection layer enhances multi-scale defect recognition in complex environments. Cross-dataset evaluations validate the model’s robustness and adaptability, with 15.2–16.3% mAP@0.5 improvements in blade damage detection and a 3.1% accuracy gain in agricultural defect identification. Although the performance on steel surface datasets varies, the systematic integration of DWConv, MBConv, and ECA mechanisms establishes a methodological advancement for industrial vision applications. The proposed framework demonstrates an effective trade-off between precision and efficiency, contributing to real-world computer vision solutions for wind energy infrastructure maintenance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous development of society, renewable and sustainable energy sources have become key trends in energy development. Wind energy, as an efficient and clean source of energy, plays a crucial role in the transformation of the energy structure. Wind energy utilization dates back more than 3,000 years1. In 1891, the Danish inventor Poul LaCour successfully constructed the first windmill for electricity generation. In 1941-42, the windmill constructed by the Danish company F.L. Smidth was regarded as the prototype of the modern wind turbine. The development of propeller-driven aircraft during World War I contributed to the practical application of modern aerodynamic theory, which, in turn, spurred innovation in the design of high-speed wind turbine blades. Following World War II, the global demand2 for energy surged, thereby accelerating the development of wind turbines. Large-scale wind turbines emerged, but their widespread adoption was limited due to unstable performance3 and poor economic efficiency, which hindered their short-term application. It was not until the early 1970s, when the oil crisis occurred, that the focus shifted back to renewable energy, with wind power receiving significant attention. By the 1950s, scientists began exploring the design4 and construction of wind turbines, accumulating valuable experience. While wind power technology was not fully mature at the time, it laid a solid foundation for future advancements.

As the advantages of wind energy, a clean and renewable energy source, became more widely recognized, wind power has become a key component of sustainable development. Unlike traditional energy sources, wind power ensures long-term resource5 sustainability. However, wind turbines are typically located in remote areas with complex environments and harsh conditions, where extreme weather and geographical challenges present significant obstacles to equipment operation and maintenance. The primary causes of wind turbine failures can be attributed to two factors: material defects6 during the manufacturing process and the impact of complex environmental factors on turbine performance. When equipment malfunctions and is not promptly repaired, operational and maintenance costs increase, and the equipment may become inoperable. More seriously, if not addressed6 in time, wind turbine blades may detach, which, in extreme cases, could result in injuries or fatalities. Therefore, timely and effective maintenance is crucial. To ensure the proper functioning of wind turbines, various detection methods, including vibration monitoring, acoustic emission monitoring, strain monitoring, ultrasonic testing, thermal imaging, and machine vision, have been proposed and applied for fault diagnosis in wind power equipment. However, these methods exhibit notable limitations in practical applications. Contact sensors are expensive to deploy, optical detection is highly susceptible to environmental lighting interference, and acoustic emission devices increase the complexity of data processing due to their high sampling rates. Moreover, traditional damage detection methods rely on costly and6 bulky sensors, which face challenges when applied in large wind farms, particularly in offshore or dynamic environments. Specifically, when detecting damage to wind turbine blades, traditional hardware methods struggle to meet on-site real-time detection needs due to the high-speed rotation of blades, remote installation, and the fact that significant wear is often required before damage becomes detectable. Thus, the development of high-precision, low-cost intelligent detection systems has become a critical technological breakthrough in improving the economic efficiency of wind farms.

With the rapid development of computer vision technology, deep learning methods have become indispensable for wind power equipment damage detection and maintenance, offering innovative solutions to these challenges. In the application of deep learning to wind turbine detection, the first step involves using image acquisition devices6 to capture images of the equipment. However, due to the limitations of ground-based equipment in capturing comprehensive images of wind turbines, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology has become a crucial tool for image collection in recent years. UAVs overcome these limitations by enabling more comprehensive and efficient image capture. However, early UAV technology was underdeveloped, and the accuracy and stability of the captured images were inadequate for high-precision detection. To address this, researchers have proposed techniques such as image deblurring and stitching to enhance image quality. For instance, Li1 introduced an adaptive contrast enhancement algorithm based on dark channel and unsharp masking to improve image clarity in high-haze areas. Experimental results demonstrate that this method removes haze more effectively, thereby improving contrast. However, these techniques still face challenges such as high computational complexity and slow detection speeds, which hinder real-time damage detection in wind turbine blade maintenance.

As deep learning continues to evolve, it has been applied to the analysis of sensor data for wind power equipment detection. Unlike traditional data analysis methods, deep learning automatically identifies complex patterns in sensor data, thereby improving fault prediction and diagnosis. While this method increases efficiency and accuracy, particularly for diagnosing complex issues such as bearing faults, it often fails to detect minor surface damage in a timely manner. This limits the effectiveness of structural-based detection methods, particularly when sensor installation may cause additional damage or affect equipment performance.

Non-destructive testing (NDT)2 methods, such as ultrasonic testing, have become essential for diagnosing damage in wind power equipment. While NDT methods are capable of detecting internal damage, they require sensor installation and are susceptible to environmental noise and other complexities. This has led to a shift in focus towards dynamic, real-time NDT methods. With the maturation of UAV technology, a new solution has been found: UAVs are capable of capturing high-resolution images while adapting to complex environmental conditions, particularly in remote or hard-to-reach areas. Researchers have begun utilizing UAVs for detecting damage to wind turbine blades, thereby opening new avenues for real-time damage monitoring. Although UAVs provide high-quality image data, deep learning algorithms continue to face challenges such as high computational and training costs, as well as limited real-time performance, which restrict their use in practical maintenance. For example, P.M3. proposed the Cascade Mask R-DSCNN model in 2023, which outperforms existing WTB defect detection methods. However, it still requires two minutes to process 50 images, which is too slow for real-time4 wear damage detection. As target detection technologies continue to develop, YOLO series algorithms have become mainstream tools in wind power equipment damage detection due to their efficient real-time performance. Researchers have begun applying YOLO algorithms to wind turbine damage detection. In 2023, Wang5 proposed the UCD-YOLO model, based on YOLOv5, for ultrasonic wind turbine damage recognition. However, the model still struggled with detecting damage at the blade base. Yang6 later proposed the YOLOv5s_MCB model, which performs high-precision, low-energy real-time detection on embedded devices. However, it only detects surface defects and fails to identify internal ones. In 2024, Zhang7 introduced the EV-YOLOv8 model, which demonstrates excellent fault detection results, but still requires improvement in balancing efficiency and accuracy. Wang8 further proposed an improved YOLOv8 algorithm, which showed promise in blade damage detection. However, it primarily focused on blade damage, overlooking other components. Zou9 introduced an improved YOLOv8 algorithm in 2025, developing a mobile app named WTBs for real-time, high-precision blade damage detection on Android devices. However, this method does not address more complex damage types or improve robustness and generalization in dynamic environments, thereby limiting its application in broader scenarios.

Despite advancements in these methods, existing algorithms still exhibit significant limitations in full-scale wind power equipment damage detection, particularly in multi-scale feature extraction, real-time performance, and accuracy. Most current methods for surface damage detection in wind power equipment rely on YOLO algorithms, with YOLOv8 being one of the more mature algorithms in the series, striking a good balance10 between speed and accuracy. However, single-stage detection algorithms, such as YOLO, continue to face substantial challenges in wind turbine damage detection. For example, blade surface damage (e.g., cracks, corrosion) typically manifests as elongated, discontinuous microstructures, which can be easily disrupted by composite surface textures. This results in missed detections or mislocalizations under complex outdoor conditions (e.g., lighting changes, rain, snow) or in dim indoor spaces. Moreover, high-precision models, such as Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet, exhibit computational complexities that prevent them from meeting real-time requirements on UAV/robot platforms.

Although similar studies have applied YOLO-based models or other object detection frameworks to wind turbine blade defect detection, challenges remain in achieving high detection accuracy on real-world datasets with complex background noise and small-scale defects. Many existing approaches either focus on generic object detection7 or struggle to achieve competitive performance on specialized industrial datasets. Consequently, YOLOv8n is selected as the base framework for targeted improvements in this study. YOLOv8n’s cross-scale feature fusion mechanism performs well for multi-scale targets. However, experiments conducted on wind turbine damage datasets reveal that its mAP is only 76.2% when directly applied, failing to meet industrial detection standards.

Additionally, several key limitations remain unresolved in recent literature. Firstly, lightweight variants such as DSC-YOLOv8 rely heavily on depthwise separable7 convolutions, which reduce parameter count but weaken channel interactions—leading to the loss of subtle damage features in dense texture regions. Secondly, attention mechanisms like SE-Net8 introduce over 2 million additional parameters, significantly increasing model size and making them difficult to deploy on embedded or UAV-based platforms. Lastly, recent models such as EV-YOLOv8 overlook the challenge of aerial image resolution adaptation, resulting in high missed detection rates9 for small or partially occluded damage targets. These shortcomings highlight the need for a more balanced solution that preserves fine-grained features, ensures attention efficiency, and adapts to the practical constraints of aerial inspection scenarios.

To address these issues, this study proposes a novel and application-oriented framework—YOLO-Wind—based on YOLOv8n, with targeted enhancements for accuracy, feature representation, and deployment efficiency9. These innovations are specifically tailored to tackle the practical challenges9 of small damage detection under noisy, high-altitude UAV imagery.

(1) Depthwise Separable Convolution (DWConv) Module: To address the high computational cost associated with traditional convolutional operations, this study introduces DWConv in place of standard convolution layers. By significantly reducing the number of parameters and computations, DWConv enables a more lightweight model design while maintaining robust feature extraction capabilities. This modification greatly enhances the adaptability of YOLOv8n to real-world, resource-constrained scenarios, such as edge deployments in wind power monitoring systems.

(2) MobileNetV2 Bottleneck Layer Structure (MBConv): We incorporate the MBConv module into the C2f structure to construct a more compact yet powerful feature extraction backbone. This integration not only optimizes gradient propagation but also enhances multi-scale feature representation, which is crucial for accurately detecting subtle and irregular damage patterns on wind power equipment surfaces. Compared to conventional backbone structures, the MBConv-based design offers a superior balance between efficiency and detection accuracy.

(3) Efficient Channel Attention Mechanism (ECA): To further improve the model’s sensitivity to fine-grained damage features, an ECA module is introduced. Unlike more complex attention mechanisms, ECA introduces minimal overhead while effectively enhancing inter-channel feature dependencies. This results in a notable boost in detection accuracy, particularly in challenging conditions where damage features may be small, sparse, or low contrast.

(4) P2 Detection Layer: A novel P2 detection layer is added to enrich the model’s ability to capture shallow, high-resolution features. This addition is especially beneficial for detecting small-scale defects that are often missed in standard multi-scale detection schemes. By extending the detection pyramid, the model achieves stronger multi-resolution performance, addressing a key limitation of existing YOLO-based approaches.

While this study does not focus on extreme lightweight compression, the increase in model parameters introduced by the proposed enhancements remains modest and does not significantly hinder deployment on edge devices such as UAVs or embedded platforms. The resulting model demonstrates substantial improvement10 in detection accuracy and robustness, enabling more reliable identification of early-stage surface damage. This improvement has the potential to reduce maintenance costs, prevent equipment failure, and enhance the efficiency of predictive maintenance workflows. These enhancements are synergistically designed to overcome the aforementioned limitations and are validated to deliver superior performance. In summary, this study proposes a precision-enhanced YOLOv8n-based detection model for wind power equipment damage inspection, combining improved accuracy with practical deployability for real-world scenarios.

Related work

YOLOv8

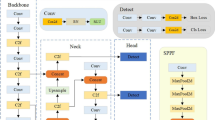

YOLOv8 (see Fig. 1), as a representative framework for single-stage object detection algorithms, consists of three core components: the feature extraction network (Backbone), the feature fusion layer (Neck), and the detection head (Head). The Backbone utilizes an enhanced CSPDarknet structure, alternating between standard convolution (Conv) modules and C2f modules for multi-scale feature extraction. The C2f module employs a Cross Stage Partial (CSP) connection strategy, facilitating the retention of shallow detailed features while enhancing deeper semantic representations. The Neck section employs the Path Aggregation Network (PANet) to facilitate both top-down and bottom-up multi-scale feature fusion. Its key component, the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module, expands the receptive field through parallel max-pooling operations, significantly improving the model’s capacity to detect objects at various scales.

The Head section employs a decoupled detection head design to process multi-scale feature inputs (P3, P4, P5) from the Neck layer. Tasks are divided into three independent branches for classification, location regression, and object confidence. Specifically, the classification branch applies a 1 × 1 convolution layer and a Softmax activation function to generate category probabilities for each object; the regression branch utilizes a 3 × 3 convolution layer with a linear activation function to estimate bounding box coordinates, including center point offsets and scaling factors for width and height; and the object confidence branch determines whether each candidate box contains an object. Each branch is specifically assigned to its designated task.

The feature inputs are initially processed through a basic convolution module to align the channel dimensions (from 256 to 128) and are subsequently fed into each branch for optimization. By decoupling the gradient propagation paths for classification, regression, and confidence tasks, optimization conflicts inherent in traditional coupled designs are effectively mitigated, resulting in enhanced detection performance and stability.

Efficient channel attention mechanism

In recent years, the channel attention mechanism, which dynamically adjusts feature channel weights, has emerged as a crucial technique for enhancing the discriminative power of deep models. Efficient Channel Attention (ECA-Net, Wang et al.11, 2020), in particular, directly captures cross-channel interactions using 1D convolution, thereby mitigating performance loss caused by dimensionality reduction, and has demonstrated significant advantages in lightweight models. Early studies, such as SENet (Hu et al.12, 2018), introduced the global channel attention module, which models inter-channel dependencies through fully connected layers. However, the dimensionality reduction employed in these methods results in feature information loss and a significant increase in the number of parameters (e.g., ResNet-50 adds approximately 2.5 million parameters).

In recent years, the channel attention mechanism, which dynamically adjusts feature channel weights, has emerged as a crucial technique for enhancing the discriminative power of deep models. Efficient Channel Attention (ECA-Net, Wang et al.11, 2020), in particular, directly captures cross-channel interactions using 1D convolution, thereby mitigating performance loss caused by dimensionality reduction, and has demonstrated significant advantages in lightweight models. Early studies, such as SENet (Hu et al.12, 2018), introduced the global channel attention module, which models inter-channel dependencies through fully connected layers. However, the dimensionality reduction employed in these methods results in feature information loss and a significant increase in the number of parameters (e.g., ResNet-50 adds approximately 2.5 million parameters).

To meet the demand for lightweight models, subsequent studies have simplified the attention structure. For instance, MobileViT (Mehta et al.12, 2021) employs a local channel interaction strategy to reduce computational cost. However, its static weight allocation is insufficient for adapting to complex and dynamic detection scenarios, such as small targets and background interference in wind turbine blade damage detection. To balance performance and efficiency in attention mechanisms, Wang et al.11 proposed Efficient Channel Attention (ECA-Net). The ECA module reduces parameter count by over 90% compared to SENet and has been validated for effectiveness in ImageNet classification tasks.

The ECA module was designed to balance performance and computational cost in traditional channel attention mechanisms. Other channel attention methods typically capture inter-channel relationships using global average pooling (GAP) and fully connected (FC) layers; however, this often necessitates dimensionality reduction to manage model complexity. Although dimensionality reduction reduces computational load, it disrupts the direct correspondence between channels and their associated weights, thereby impacting performance. The ECA module eliminates the need for dimensionality reduction, preserving the direct correspondence between channels and weights, thereby enhancing both the effectiveness and efficiency of the channel attention mechanism.

The ECA module (see Fig. 2) introduces a strategy for local cross-channel interaction, employing 1D convolution to capture local dependencies. The size of the convolution kernel is dynamically adjusted based on the number of channels, enabling different network architectures to flexibly adapt the range of interactions. This adjustment reduces computational cost and improves efficiency, thereby eliminating the need for manual tuning. Compared to traditional attention mechanisms, the ECA module substantially reduces model complexity.

The lightweight design of the ECA module enables performance enhancement while maintaining low computational cost. Consequently, ECA exhibits high efficiency on large-scale datasets. It has also demonstrated outstanding performance in tasks such as object detection and instance segmentation, further validating its adaptability and efficiency. Overall, the ECA module enhances model efficiency while preserving low computational complexity by incorporating efficient local cross-channel interactions and adaptive convolution kernel sizes. Its lightweight architecture renders it an optimal choice for real-time tasks in practical applications.

Although ECA has demonstrated high efficiency in general object detection tasks (e.g., the COCO dataset), its potential for industrial detection tasks involving small, dense targets and high environmental noise remains insufficiently explored. Existing research primarily focuses on general object detection scenarios, lacking a comprehensive exploration of ECA’s potential in industrial detection tasks with dense small targets and strong environmental noise. For instance, in wind turbine blade damage detection, direct integration of traditional ECA into the backbone network may result in excessive smoothing of fine-grained texture features, thereby hindering the distinction of damaged areas from background interference (e.g., clouds and vegetation in UAV aerial images). Furthermore, existing methods frequently neglect the collaborative optimization of channel attention and multi-scale feature extraction modules, thereby restricting the ability to detect small defects in complex environments.

Proposed algorithm

This study introduces a more efficient algorithm for wind turbine damage detection, named YOLO-Wind, as illustrated in the structural diagram (see Fig. 3). Initially, the standard convolution module in YOLOv8 is replaced with depthwise convolution (DWConv), enhancing both computational efficiency and feature extraction capabilities. Furthermore, the bottleneck layer (MBConv) from MobileNetV2 and the ECA attention module are integrated into the C2f module, significantly enhancing the model’s detection accuracy. Additionally, the three-input layer of YOLOv8 is expanded to four inputs through the introduction of the P2 detection layer, enriching semantic feature information and improving detection performance. This modification allows the model to more effectively process multi-scale feature inputs from the Neck section, thereby further enhancing both detection accuracy and adaptability.

DWConv module structure

Standard convolutional modules in YOLOv8 extract hierarchical features from input images. In this study, we replace them with depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational overhead while maintaining fine-grained spatial sensitivity, particularly relevant to detecting wind turbine defects. Unlike traditional convolution, which applies a single kernel across all channels, depthwise convolution (see Fig. 4) processes each channel separately. For instance, with a 3 × 3 convolutional kernel, depthwise convolution applies independent convolutions to each channel rather than combining all channels at once. This means that each channel is convolved using a dedicated kernel, thus avoiding inter-channel mixing. In this study, a 3 × 3 kernel size is selected for the depthwise convolution, following standard practice in lightweight convolutional architectures such as MobileNet. This size offers an effective trade-off between spatial feature extraction capability and computational efficiency. Larger kernels (e.g., 5 × 5) can capture broader context but significantly increase computation, while smaller kernels (e.g., 1 × 1) lack the spatial receptive field necessary for effective local pattern recognition. The 3 × 3 kernel thus provides sufficient spatial resolution to detect fine-grained damage features on wind turbine surfaces, while maintaining a lightweight structure suitable for edge deployment. After extracting spatial features from each channel, a 1 × 1 convolution (also known as pointwise convolution) is used to combine the extracted features across channels. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity by eliminating the need for dense cross-channel feature interactions, while still capturing important spatial patterns.

Depthwise convolution offers several advantages, including feature invariance, dimensionality reduction, and mitigation of overfitting, while drastically reducing computational costs and the number of model parameters. These properties make it especially suitable for resource-constrained environments, such as real-time image processing and object recognition tasks on mobile and embedded devices. In the context of wind turbine damage detection, leveraging depthwise convolution enables the model to achieve higher efficiency and real-time performance, without a significant loss in detection accuracy.

To enhance computational efficiency while preserving the spatial detail necessary for fine-grained damage detection, this study adopts a depthwise separable convolution structure composed of two sub-operations: pointwise convolution (1 × 1) and depthwise convolution (3 × 3). Traditionally, DWConv is implemented by first applying a depthwise convolution to extract spatial features for each individual channel, followed by a pointwise convolution to combine information across channels.

However, in this study, we deliberately reverse the standard order of operations and perform pointwise convolution first, followed by depthwise convolution. Unlike the conventional DWConv implementation, where spatial filtering precedes channel mixing, we reverse the order to first apply pointwise convolution followed by depthwise convolution. This design choice is based on the observation that early inter-channel semantic interaction helps guide spatial feature extraction in the presence of low-contrast textures, as is common in wind turbine blade images. Ablation studies (“Ablation experiment”) further confirm that this reversed ordering improves detection performance on small, texture-rich targets. This modification is made based on the specific feature distribution characteristics of the wind turbine blade damage dataset, which contains localized and sparse edge patterns over complex textured backgrounds. By initially performing a pointwise convolution, the model can establish inter-channel dependencies earlier, enabling richer semantic guidance before conducting spatial filtering via depthwise convolution. This reversed operation flow helps to retain cross-channel contextual cues when detecting subtle or partially occluded defects.

This implementation differs fundamentally from standard DWConv usage and represents a task-driven architectural innovation. While most prior work (e.g., DSC-YOLOv8) applies DWConv in a fixed conventional sequence, our model reconfigures the module flow to better align with the detection needs of small-scale, edge-focused industrial targets. Experimental comparisons show that this reversed DWConv ordering improves both detection precision and feature robustness under noisy, high-resolution conditions—particularly in the early-stage layers of the network.

This design choice highlights the originality of our approach, as it not only leverages the efficiency benefits of DWConv but also redefines its internal structure to enhance its suitability for UAV-based real-time wind turbine damage inspection tasks.

To quantitatively evaluate the efficiency of depthwise separable convolution (DWConv) over standard convolution, we analyze their respective computational complexities. Let the input feature map size be Dk×Dk×M, the kernel size be DF×DF, and the number of filters be N. For standard convolution, the total computational cost is:

In contrast, the computational cost of DWConv consists of two components:

Thus, the total cost of DWConv is: \(\:{D}_{k}\times\:{D}_{k}\times\:{D}_{F}\times\:{D}_{F}\times\:M+M\times\:N\times\:{D}_{k}\times\:{D}_{k}\)

By comparing (1) and (4), the relative computational savings of DWConv can be expressed as:

This shows that DWConv significantly reduces computational cost compared to standard convolution, especially when the number of filters N and kernel size DF are large. In our experiments, this optimization enables our model to maintain real-time inference speed on embedded platforms while achieving higher detection precision than baseline models.

MB-ECA-C2f module structure

In the original YOLOv8 model, the Conv and C2f modules are core components of the network. The C2f module is involved in both the Backbone and Neck sections, making it one of the most frequently used modules in the network structure. To improve the detection accuracy and efficiency of the baseline model for specific tasks, each component was fine-tuned and extensively tested. Experimental results demonstrate that even small improvements to the C2f module significantly enhance detection accuracy and efficiency for the target dataset. Specifically, the C2f module is responsible for multi-scale feature fusion in YOLOv8 and plays a crucial role in feature extraction. Modifying the C2f module optimized both feature extraction efficiency and computational performance. The Bottleneck structure in the C2f module was replaced with the MBConv module, which integrates depthwise separable convolution with the inverted residual structure14. This modification significantly reduces computational complexity while maintaining strong feature extraction capability.

In this study, the C2f module of YOLOv8 was improved by replacing the original Bottleneck module with the MBConv module and adding the ECA (Efficient Channel Attention) mechanism after each MBConv module. The MBConv module is based on depthwise separable convolution and the inverted residual structure. By decomposing standard convolution into depthwise separable convolution, computational complexity is reduced while preserving high feature extraction capability.

The MBConv module is an efficient convolution structure combining depthwise separable convolution and the bottleneck structure15. It is widely used to enhance computational efficiency and expressive power in neural networks. The MBConv module16 consists of four key components: standard convolution layers, depthwise separable convolution layers, the SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) attention module, and pointwise convolution layers. Each of these components plays a crucial role in feature extraction and computational optimization.

First, the standard convolution layer uses 1 × 1 convolution to project channel features, adjusting the number of channels and projecting information to higher or lower dimensions, thereby preparing the input for subsequent operations. This 1 × 1 convolution serves as the “bottleneck,” reducing computational complexity and eliminating redundant features.

Next, the depthwise separable convolution layer (3 × 3 convolution) extracts spatial features. Unlike traditional convolution, depthwise separable convolution separates the process into two stages: first, it independently convolves each input channel to extract spatial features; then, it combines features across channels with pointwise convolutions (1 × 1 convolutions). This method significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational load.

The choice of the 3 × 3 convolution kernel in the MBConv module is also a deliberate balance between feature expressiveness and computational efficiency. In contrast to smaller kernels (e.g., 1 × 1 or 2 × 2), which may lack the spatial context necessary to capture elongated or discontinuous damage patterns, the 3 × 3 kernel provides sufficient receptive field to detect localized texture variations such as cracks, corrosion edges, and abrasions. Larger kernels like 5 × 5 or 7 × 7, although offering broader context, significantly increase the computational cost and are less suitable for deployment on edge devices such as UAVs. Therefore, the 3 × 3 kernel is retained as the optimal design choice in this task-driven structure, ensuring strong spatial sensitivity while maintaining model compactness.

The SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) module aggregates contextual information along the channel dimension through global average pooling, thereby enhancing the model’s attention to important features. It compresses each channel’s spatial dimension using global average pooling, generates a global descriptor, and subsequently applies a fully connected layer to generate channel weights. These weights are multiplied element-wise with the original feature map, enhancing focus on relevant channels while suppressing irrelevant ones. The SE module enhances MBConv’s sensitivity to important channels, thereby improving the model’s expressive power.

Finally, the pointwise convolution layer (1 × 1 convolution) is used to expand channel features, thereby generating richer feature maps. This layer integrates channel-wise features after depthwise separable convolution, enabling the model to extract more complex features while further reducing computational complexity.

By decomposing traditional convolutions into depthwise separable convolutions, the MBConv module significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational complexity while efficiently extracting both spatial and channel features. Additionally, the SE module enhances the model’s channel selectivity, enabling it to focus on important features and improving performance in complex tasks. These attributes render the MBConv module particularly effective in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices.

In the “MB_ECA_C2f” module of this study, the MBConv module is combined with the ECA (Efficient Channel Attention) mechanism (see Fig. 5), further enhancing the model’s attention to critical features. The ECA module adapts attention across channels, thereby reducing computational burden and enhancing the model’s robustness and adaptability across tasks. This combination enables the MB_ECA_C2f module to maintain computational efficiency while achieving higher detection accuracy, thereby performing exceptionally well in tasks such as wind turbine damage detection.

Following each MBConv module, the ECA (Efficient Channel Attention) mechanism is introduced to further enhance the model’s feature extraction capabilities. The MBConv module efficiently extracts spatial features using depthwise separable convolution while reducing computational complexity, and the ECA mechanism enhances the model’s focus on critical features by adaptively adjusting channel attention. After the MBConv module extracts initial multi-scale features, the ECA module refines these features by applying weights, thus improving the model’s performance in handling complex features—particularly in accurately capturing damage features across various scales. This combination enables the model to precisely identify and locate damage in wind turbines while maintaining computational efficiency, thereby demonstrating greater adaptability and robustness in complex environments.

In summary, by replacing the Bottleneck module with the MBConv module and incorporating the ECA attention mechanism, the model’s feature extraction has been significantly enhanced. This improvement not only boosts the efficiency and accuracy of feature extraction but also enhances the model’s ability to focus on key features, enabling it to more accurately identify and locate wind turbine damage, particularly in challenging environments, thereby demonstrating enhanced stability and robustness.

A context-specific integration of MBConv and ECA is implemented within the C2f module to construct a lightweight, attention-augmented structure optimized for wind turbine surface damage detection. The unique characteristics of UAV-captured wind turbine images—such as high-resolution textures, small-scale elongated defects, and complex backgrounds (e.g., clouds, vegetation)—pose challenges that conventional backbone modules fail to address adequately.

To better adapt to these challenges, the original Bottleneck structure within the YOLOv8 C2f module is replaced with MBConv, enabling enhanced gradient propagation and feature expressiveness without increasing computational burden. In contrast to conventional SE modules, which introduce a high parameter count, the ECA mechanism is adopted in this study for its lightweight yet effective channel-wise attention. Its design enables precise enhancement of key features without incurring the memory cost of fully connected layers, making it highly suitable for UAV-based deployment scenarios.

More importantly, the MB_ECA_C2f module proposed in this work is not a simple reuse of existing components, but a task-driven redesign. By integrating MBConv and ECA into the YOLOv8 C2f module, a lightweight, attention-enhanced fusion structure is introduced to address the specific demands of wind turbine defect detection. This architecture is validated to outperform both baseline C2f modules and other attention-enhanced variants (e.g., MobileNet-C2f) on wind turbine datasets, achieving a superior balance between detection precision and computational efficiency.

Therefore, the C2f improvements presented in this work are not only effective in terms of mAP gains but also uniquely optimized for the specific demands of high-altitude, high-resolution, and texture-complex wind turbine inspection tasks, demonstrating clear originality and task relevance.

P2 small object detection layer

In the original YOLOv8 model17, the detection head consists of three scales (P3–P5), which limits the model’s ability to detect small objects in high-resolution aerial imagery. The model employs a three-scale detection head structure (P3–P5)18, where each prediction head corresponds to progressively downsampled feature maps: 80 × 80, 40 × 40, and 20 × 20, respectively. These feature maps are generated through multiple downsampling operations from the input image (640 × 640 resolution), with the deepest layer experiencing up to 32× downsampling. While this design improves detection efficiency and works well for large and medium-sized objects, it significantly degrades the representation of small targets, which are often overwhelmed or lost in the deep semantic layers. For an input image\(\:I\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:3}\), the feature map at scale s is generated through:

where Ds(·) denotes the backbone network’s downsampling operations with stride 2s-1. This results in severe information loss for small objects, as targets smaller than 10 × 10 pixels occupy less than 0.025% of the deepest feature map(F5):

This limitation becomes particularly problematic in UAV-based wind turbine inspection scenarios. UAVs typically capture images from high altitudes with wide coverage, resulting in small targets such as fine cracks, stains, and surface abrasions occupying only a few pixels. For example, in practical blade damage images, over 60% of annotated defects are smaller than 10 × 10 pixels, making them difficult to detect using the default three-scale architecture. Moreover, traditional Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs) in YOLOv8 tend to prioritize high-level semantic features, further diminishing the importance of fine-grained details essential for surface damage recognition.

To address these task-specific challenges, this study introduces an additional small-object detection head (P2)19 into the YOLOv8 architecture, resulting in a novel four-scale detection structure (P2–P5) (see Fig. 6). The P2 head operates on a 160 × 160 feature map and is specifically designed to enhance the detection of small objects down to 4 × 4 pixels in size. The head processes a 160 × 160 feature map(F2) derived from shallow layers with stride 4:

Experimental validation demonstrates that the P2 head improves small-object detection sensitivity through, where pi(r) is the precision-recall curve for small targets. Our method achieves \(\:\Delta mAP@0.5=+2.5\%\) compared to baseline, with 63% reduction in false negatives for sub-10px targets.

This is particularly critical for capturing minute blade damage features that would otherwise be lost in deeper layers. By incorporating the P2 head, the model retains more shallow-level texture and edge information, which improves its ability to localize and classify fine defects.

Unlike general-purpose detection models, the introduction of the P2 head in this study is not a generic architectural extension but a domain-specific innovation tailored for wind turbine surface damage detection. We extend the default YOLOv8 three-scale head by adding a P2 layer tailored for UAV-based inspection imagery. While similar multi-scale approaches exist, our four-scale design specifically enhances small-target detection under aerial conditions. Experimental results show that adding the P2 layer leads to a 2.5% improvement in mAP@0.5 and significantly increases detection precision on small-target categories such as “crack” and “dirt.” These improvements demonstrate that the model not only captures more detailed damage features but also reduces false negatives in cluttered aerial environments.

In summary, the P2 detection head enhances YOLOv8’s ability to detect small and fine-grained targets typical in wind turbine inspections. Its inclusion reflects both the originality and task-specific optimization of the proposed YOLO-Wind framework, providing a meaningful performance advantage in real-world wind energy maintenance applications.

Experiment

Datasets

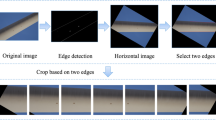

As wind turbines have only recently begun to be installed on a large scale, and UAV technology is still maturing, the existing data on wind turbine damage collected by UAVs remains limited. To address this gap, this study uses a publicly available dataset on wind turbine surface damage, sourced from Shihavuddin & Chen (2018)20, which is annotated with “dirty” and “damage” labels in YOLO format. The dataset comprises 13,000 images, nearly 3,000 of which contain instances of the “dirty” and “damage” categories. Notably, only 2,995 images have been manually annotated, and these annotated images and their corresponding labels are used in this study as the source of experimental data. In the experiments, the images were divided into training and validation sets in a 7:3 ratio. The training set contains 2,096 images, while the validation set includes 899 images, all of which are labeled with the “dirty” and “damage” categories. Both the images and labels are annotated in YOLO format to facilitate model training and validation.

Experimental environment and parameter configuration

The experiments were conducted on a system equipped with an RTX 2080 Ti (11GB VRAM) GPU and an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8255 C CPU with 12v CPUs, running Ubuntu 20.04. The programming environment is based on Python 3.8, utilizing the PyTorch 1.11.0 deep learning framework and CUDA version 11.3. The training hyperparameters (Table 1) were determined through iterative ablation studies:

To ensure efficient training and to prevent overfitting, an early stopping mechanism was applied. Specifically, training was terminated if the validation loss did not improve for 30 consecutive epochs (i.e., a patience value of 30). Although the maximum number of training epochs was set to 300, most training processes converged earlier due to this stopping criterion. This strategy allows the model to stop training automatically when performance plateaus, avoiding unnecessary computation while preserving model accuracy.

Evaluation metrics

The detection performance in this study is assessed using the following metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), Model Size, Frames Per Second (FPS), Mean Average Precision (mAP), and Mean Average Precision at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5).

Precision and Recall are defined as \(\:P=\frac{TP}{(TP+FP)}\) and \(\:R=\frac{TP}{(TP+FN)}\), respectively, where TP (True Positives) denotes correctly detected defects, FP (False Positives) represents background regions misclassified as defects, and FN (False Negatives) indicates true defects undetected by the model. The overlap between predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes is quantified by the Intersection over Union (IoU), expressed as:

with a detection considered valid if IoU ≥ 0.5.

The Average Precision (AP) for each category is calculated as the area under the Precision-Recall (PR) curve, formally given by:

which is approximated numerically through discrete interpolation across all unique recall levels. The overall MAP is derived by averaging the AP values of all N categories:

The mAP@0.5 specifically refers to the mAP computed at an IoU threshold of 0.5.

The PR curve illustrates the trade-off between precision and recall across varying confidence thresholds, while model efficiency is evaluated via FPS (frames processed per second) and Model Size (parameter count or storage footprint).

Model selection

In recent years, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) object detection framework has undergone rapid development, with newer versions such as YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11 introducing a variety of architectural innovations. Each version typically provides multiple sub-models of different sizes (e.g., normal, small, medium), designed to address various trade-offs between computational cost and detection performance.

Considering the limited size of the dataset used in this study and the practical requirement of deploying the model on resource-constrained edge devices—such as those used in wind turbine inspection systems—we selected the most lightweight variant of each version: YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv11n. Table 2 presents a comparison of these models in terms of architectural complexity and computational cost, measured by the number of layers, parameters, and GFLOPs.

From the table, it can be observed that YOLOv8n has the fewest layers among all the compared models, which benefits model simplicity and training stability. Although its parameter count (3.16 M) and FLOPs (8.7) are relatively higher than those of the newer YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv11n variants, YOLOv8n achieves better balance in practice due to its mature architecture and well-optimized implementation. The YOLOv9t model has a much deeper architecture (917 layers) while maintaining fewer parameters, which often results in longer training times and higher memory requirements. YOLOv10n and YOLOv11n present marginal improvements in latency and compression, but offer no significant advantage in detection accuracy or inference speed within the context of this study.

Furthermore, YOLOv8 benefits from full support by the Ultralytics framework and a wide range of applications across detection, classification, and segmentation. In contrast, the newer versions are still undergoing frequent updates, and their ecosystems remain relatively immature, which increases the difficulty of stable deployment and structural customization.

Based on these considerations, YOLOv8n is selected as the baseline model for this work. It provides a reliable and practical foundation for structural enhancement, and enables clearer assessment of the proposed architectural modifications. Choosing YOLOv8n allows the performance improvements introduced by our method to be more effectively quantified and generalized across real-world scenarios.

Results and analysis

DWConv position comparison

To evaluate the optimal deployment of the DWConv module within the model, we conduct a set of comparative experiments (Table 3) assessing four replacement strategies: (1) replacing all Conv modules in the Backbone; (2) replacing all Conv modules in the Neck; (3) replacing all Conv modules in the entire model; and (4) replacing all Conv modules except the first layer. While all configurations yield competitive detection results, the observed variation highlights the importance of structural position in balancing accuracy and feature representation.

Strategy 3, which indiscriminately applies DWConv across the entire network, results in only marginal improvements in mAP, but introduces a notable risk of degrading fine-grained feature encoding due to the loss of early spatial resolution and channel expressiveness. The reduction in early-stage spatial and channel information compromises the model’s ability to capture subtle, low-level textures, which are crucial for identifying surface-level defects such as cracks and abrasions. In contrast, Strategy 4, which applies DWConv to all layers except the first, preserves the initial feature extractor’s capacity to capture low-level patterns, such as edges and textures, by retaining the spatial sensitivity of the initial convolution layers. This configuration strikes a balance between computational efficiency and maintaining essential low-level feature capture, which is vital for detecting surface defects in high-resolution images. Depthwise convolutions, while efficient, inherently lack the full inter-channel mixing of standard convolutions, and thus are less suitable for early layers where local texture fidelity is critical.

The Neck section, which plays a critical role in aggregating multi-scale features and facilitating both top-down and bottom-up pathways, proves to be an optimal insertion point for DWConv (Strategy 2). At this stage, spatial information has already been encoded in the Backbone, making the Neck an ideal location to focus on semantic fusion and channel-wise weighting. By applying DWConv in this region, redundant spatial computations are minimized, while the model retains strong contextual learning, effectively enhancing the feature aggregation process. This approach offers computational efficiency without sacrificing the model’s ability to capture high-level semantic information, which is essential for object detection tasks. The improvement in precision from 0.829 (baseline) to 0.856 with Neck-only replacement also empirically supports this design choice.

Strategy 1, which replaces all Conv modules in the Backbone, offers moderate improvement in precision but sacrifices recall slightly. This configuration yields high performance on AP-dirt but shows limited improvement in AP-damage, suggesting that the Backbone is not the ideal location for applying DWConv. In contrast, Strategy 2, applying DWConv to the Neck, shows a slight increase in precision and recall, highlighting that this section is well-suited for refining multi-scale features without significant performance degradation. Strategy 4, which replaces all Conv layers except the first, strikes a good balance between retaining low-level feature extraction and enhancing higher-level features, with the best overall performance across all metrics. This indicates that early feature integrity is crucial for maintaining high detection accuracy.

Comparison of results for different convolution modules with DWConv

To evaluate the performance differences between the DWConv module and other popular lightweight convolution modules, and to assess its advantages in terms of detection accuracy and deployment feasibility, we conducted a comparative experiment using three representative convolution modules: the traditional standard Conv module (serving as the baseline), the Adaptive Kernel Convolution (AKConv), which dynamically adjusts kernel weights to capture deformed patterns, and the Depthwise Separable Convolution (DWSC), which significantly reduces computational complexity by separating spatial and channel interactions.

These modules were chosen based on their architectural popularity and distinctive design philosophies in lightweight model research. The standard Conv module serves as a baseline, offering full inter-channel interaction but at a higher computational cost. AKConv dynamically adjusts kernel weights to capture deformable patterns, which enhances flexibility but introduces added complexity and parameter overhead. In contrast, DWSC separates the spatial and channel interactions via depthwise and pointwise convolutions, significantly reducing computational complexity and enabling real-time performance, making it well-suited for edge device deployment scenarios.

As shown in Table 4, DWSC (3 × 3) achieves the best balance between accuracy and efficiency, with a notable improvement in mAP@0.5 (0.823) and mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.574), while maintaining high AP-damage (0.702) for detecting subtle defects. Although DWSC achieves reasonable precision, it slightly compromises performance in terms of precision when compared to DWConv (DWSC-opp). However, DWConv outperforms DWSC by exhibiting superior recall and overall detection robustness. This indicates that DWConv is better at capturing small and partially obscured targets under real-world imaging conditions, which are crucial for practical deployment scenarios. The modifications made to the DWConv module—such as enhancing early-stage feature extraction and preserving spatial sensitivity while reducing computational complexity—proved to be highly effective. These adjustments allow DWConv to maintain strong detection capabilities in both clear and challenging imaging environments, making it a more reliable choice for real-time applications.

DWConv is ultimately selected as the default replacement module in this study due to its optimal compromise between detection precision, robustness to noisy backgrounds, and computational cost. Its lightweight nature, along with proven performance in mobile applications (such as MobileNet), makes it an ideal choice for enhancing the backbone in UAV-based wind turbine inspection tasks. This study demonstrates that DWConv offers a more practical and deployment-friendly solution compared to more complex modules like AKConv, particularly when real-time performance and low computational overhead are critical for field applications.

Comparison of results for different C2f improvement methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the improvements made to the C2f module, the performance of the ECA (Efficient Channel Attention) mechanism was first compared. Since the MBConv module already integrates the SE attention mechanism, ECA was compared with four other widely used attention mechanisms: SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation), CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module), CA (Coordinate Attention), and Channel Attention. The experimental results (Table 5) indicate that the ECA module outperforms the other four attention mechanisms in both accuracy and computational efficiency. Notably, ECA demonstrated stronger focus and greater robustness, particularly in detecting small objects such as wind turbine damage.

Next, to thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of the enhanced C2f module and determine the optimal insertion position within the YOLOv8 architecture, we systematically conducted comparative experiments by inserting the MB_ECA_C2f module into different structural locations of the network, specifically in the Backbone, Neck, and across the entire network (Table 6).

The rationale behind evaluating multiple insertion positions is that each structural location has distinct roles in the YOLO framework. Specifically, the Backbone is primarily responsible for initial spatial feature extraction, capturing essential fine-grained details. In contrast, the Neck focuses on multi-scale feature fusion and channel-wise information integration, which are critical for recognizing targets across varying scales. Evaluating module placement in both regions separately helps to clearly understand where MB_ECA_C2f can yield the greatest performance improvement. Meanwhile, deploying the module throughout the entire network (Backbone and Neck simultaneously) examines whether a comprehensive enhancement might produce a synergistic improvement or, conversely, redundancy and computational overhead.

Experimental results from Table 6 show that placing the enhanced C2f module in the Backbone yields the highest Recall (0.78), demonstrating improved capability in detecting actual damage instances. However, inserting the module into the Neck region results in higher precision (0.856) and a marginal increase in mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.569), indicating better localization accuracy for detecting defects. This suggests that the Neck is more suited for fine-grained localization tasks, while the Backbone is more effective for general damage detection. On the other hand, applying the enhanced C2f module across the entire network (All positions) results in the highest overall performance balance, achieving the optimal combined mAP@0.5 score of 0.825. It also achieves the best AP values across various defect categories, such as AP-dirt (0.946) and AP-damage (0.705), further confirming the module’s ability to handle a wide range of defect detection tasks effectively.

These comparative experiments clearly illustrate the importance of analyzing structural placement, as the optimal location of the enhanced module directly influences its effectiveness in achieving the most relevant performance metrics. This ensures that the module performs optimally for practical wind turbine damage detection, where precision, recall, and defect localization are critical. The balanced results achieved by placing MB_ECA_C2f comprehensively suggest this approach effectively maximizes overall detection performance while maintaining acceptable computational cost for edge deployment.

The selection of these locations is driven by their functional roles in the network. The Backbone is primarily responsible for low- and mid-level feature extraction, where integrating the C2f module enhances local feature encoding and gradient flow across residual connections. However, placing too many complex modules early in the network risks overfitting or redundancy, especially when processing large receptive fields. In contrast, the Neck focuses on multi-scale feature fusion. Applying the improved C2f module here improves semantic aggregation and cross-resolution representation, which is beneficial for detecting small or occluded defects. Finally, applying the enhanced C2f module across the entire network provides the benefits of both early spatial feature encoding and late-stage semantic refinement.

Experimental results show that applying the improved C2f module to all positions yields the best precision (0.853), AP-damage (0.705), and mAP@0.5 (0.825), confirming that this placement strategy effectively balances spatial detail preservation and semantic abstraction. Although placing the module only in the Neck achieves slightly better recall (0.755 vs. 0.770), it sacrifices AP-damage performance, which is more critical for precise identification of surface defects.

Moreover, the architectural choice of the C2f module itself is driven by lightweight design considerations. The MBConv block enables inverted residual learning with fewer parameters, which improves gradient propagation and prevents overfitting in deeper layers. The ECA mechanism adds minimal computational cost while providing efficient local channel-wise attention, improving feature selectivity without the parameter overhead of more complex attention modules like SE or CBAM. In summary, the integration of the optimized C2f module throughout the network offers the best trade-off between accuracy and generalization, and its placement is justified by both empirical performance and structural suitability. This design enhances the model’s robustness in real-world wind turbine blade inspection tasks, where accurate detection of fine-grained surface damage is crucial under varying lighting and background conditions.

Exploratory experiment on detection head lightweighting improvements

This study significantly improved the model’s detection accuracy for wind turbine blade damage (mAP + 5.2%) through the integration of depthwise separable convolution (DWConv) with the MBConv module in the Backbone and Neck sections. Based on this similarity, it was hypothesized that the detection head module could also benefit from lightweighting by replacing standard convolutions with DWConv or depthwise separable convolution (DWSconv). The rationale is that the channel decoupling property of DWConv might reduce redundant cross-layer feature fusion in the detection head, particularly when dealing with high-resolution P2 features (512 × 512). The lightweight design could also mitigate the computational load associated with these high-resolution features.

In this experiment, all standard convolution layers in the YOLOv8 detection head were replaced with DWConv and DWSConv, with input-output channel numbers kept consistent, to evaluate the impact of depthwise separable convolutions on model performance. The results, shown in Table 7, reveal a noticeable drop in performance, with mAP decreasing from 83.9 to 83.4% and 83.2% respectively. This performance degradation suggests that while DWConv and DWSConv can reduce computational complexity, they may not be as effective in tasks requiring deep cross-layer feature fusion, such as detection head operations. Notably, the precision and recall are slightly reduced compared to the baseline Conv module, indicating that the lightweight nature of DWConv and DWSConv might sacrifice the model’s ability to accurately detect and localize defects in more complex scenarios.

The results indicate that while DWConv excels in the feature extraction stages (Backbone/Neck), its limitations in channel interaction make it less effective for the detection head, which requires deep cross-layer feature fusion to accurately localize and classify objects. DWConv’s channel decoupling property, while beneficial in reducing computational complexity, also limits its ability to integrate information from different layers, which is crucial for detection heads that need to fuse multi-scale and multi-level features. This finding aligns with the theoretical analysis by Li et al.21 (2024), who emphasized that detection heads need to preserve sufficient channel freedom to maintain feature diversity and coordination across layers. Excessive compression of channel dimensions with DWConv disrupts the balance between spatial and semantic features, leading to a decrease in detection accuracy, particularly for small or partially obscured targets.

To address the limitations identified with DWConv in the detection head, future work will explore heterogeneous lightweighting strategies that maintain high detection performance while reducing computational load. For example, following the approach by Jin et al.22 (2021), redundant channels could be dynamically deactivated based on feature importance, thus reducing unnecessary computational overhead. Furthermore, combining grouped convolutions with spatial attention mechanisms (Tao et al.23, 2023) may effectively reduce computational costs while preserving strong channel interactions. These optimizations may improve both accuracy and computational efficiency in future models.

Ablation experiment

Following the ablation experiments on the improvement modules, the optimal integration of each module within the current structure was determined. To further validate the effectiveness of these improvement combinations, ablation experiments were conducted to assess the contribution of each module at its optimal position. The results of the ablation experiments are presented in the figure.

To verify the optimal positioning and synergy of the improvement modules (DWConv replacement, MBConv-ECA integration, and the addition of the P2 layer in the detection head) within the model architecture, a progressive ablation experiment was designed:

(1) Independent module verification: Each improvement point was applied separately to the original YOLOv8 model to determine its optimal embedding position (e.g., DWConv replacing the standard convolution in the Backbone, ECA inserted after MBConv, etc.);

(2) Combination validation: Based on the optimal positions identified in the independent experiments, the improvement points were combined sequentially to test performance changes for two-way combinations and the full combination;

(3) Cross-module coupling analysis: The collaborative mechanism of the multiple modules was analyzed through feature visualization and gradient propagation path tracking.

As shown in Table 8, the application of each module independently improved detection accuracy. Among them, the four-layer detection head contributed the most (mAP + 1.3%), while the MBConv-ECA integration significantly improved object detection performance (AP + 0.9%). When combined in pairs, the combination of MB_ECA_C2f and the four-layer detection head resulted in the highest mAP gain (81.6%, + 2.1%). Finally, the full combination of all three modules achieved the optimal mAP of 83.9% (+ 2.5%), with FLOPs of 10.6G (an increase of only 29.3%), and the parameter count was controlled at 6.1 M (a 29.8% increase compared to the original model). These results demonstrate that while each module, when applied independently or in pairs, is effective, the combined optimization of all three modules achieves cross-layer feature complementarity, resulting in the best accuracy-efficiency balance for complex wind turbine detection scenarios.

Comparative experiments

To evaluate the performance advantages of the improved model, comparative experiments were conducted using a publicly available wind turbine surface damage dataset (containing 2,995 images). The improved model was compared with current mainstream detection frameworks, including the YOLO series, Faster R-CNN, and SSD. Three metrics were compared: AP (dirt), AP (damage), and mAP@0.5, as shown in the table. The experimental results (see Table 9), presented in Table 9, show that the improved YOLO-Wind model outperforms the other frameworks across all three metrics. Specifically, the model achieved an AP (dirt) of 0.942, an AP (damage) of 0.737, and an overall mAP@0.5 of 0.839, confirming its significant advantages in wind turbine damage detection tasks. In summary, the improved YOLO-Wind model not only significantly improves detection accuracy but also demonstrates greater robustness and adaptability, proving its superior performance in wind turbine damage detection tasks.

Comparison with existing lightweight YOLO methods

To evaluate the trade-off between model efficiency and detection performance, we conduct comparative experiments on several mainstream lightweight variants of YOLOv8n, including MobileNetV3, Depthwise Separable Convolution (DSC), SlimNeck, and EfficientViT_M0-based designs. Table X summarizes the results in terms of model size, parameters, FLOPs, FPS, and detection accuracy (mAP@0.5).

As shown in Table 10, the proposed YOLO-Wind model achieves the highest detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 0.839) among all methods, outperforming both the YOLOv8n baseline (0.816) and all lightweight variants. While MobileNetV3 and DSC significantly reduce parameter count (6.74 MB and 2.98 MB, respectively), they also show a degradation in detection precision (0.809 and 0.816), suggesting a loss of expressive capability.

In contrast, YOLO-Wind introduces only a modest parameter increase (3.31 MB, slightly higher than YOLOv8n’s 3.2 MB), while improving accuracy by + 2.3%. This confirms the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements, including the ECA modules and modified DWConv design. Furthermore, YOLO-Wind achieves a competitive FPS of 400, validating its real-time capability. Notably, although EfficientViT_M0 reaches the highest FPS (500), its accuracy remains lower (0.813), indicating that extreme lightweight design may sacrifice feature richness. In summary, YOLO-Wind offers a well-balanced solution that ensures precision gain without compromising deployability, and outperforms existing lightweight designs in both accuracy and practical efficiency under real-world UAV deployment constraints.

Results analysis

Confusion matrix results analysis

Based on the confusion matrix of the improved model for the dataset (Fig. 7), the model’s performance in wind turbine blade damage detection tasks can be comprehensively analyzed. The figure presents three categories: dirty, damage, and background. The relationship between the predicted results and the actual labels of each category provides valuable insights into the model’s performance.

The confusion matrix clearly indicates that the model performs well in identifying the damage category. Of the 2,068 instances that belong to the damage category, most were correctly classified as “damage.” However, 1,059 instances of damage were misclassified as background. This number of misclassifications indicates that, while the model performs well in detecting damage, it can become confused in some cases, particularly when the visual features of the damage resemble those of the background. Therefore, distinguishing between the detailed features of damage and those of the background is crucial for optimizing the model.

The model shows certain limitations in predicting the dirty category. Although the model correctly classified two instances as “dirty,” 167 instances were misclassified as “damage,” and 13 as background. This suggests that, although the model performs well in damage detection, it faces challenges in distinguishing dirt from other categories, particularly damage from background. This may be due to the visual similarity between dirt and the background in certain cases, making it difficult for the model to classify them accurately.

The model demonstrates relatively stable performance overall in the background category. The majority of background instances (633) were correctly classified. However, 11 background instances were misclassified as “dirty,” suggesting a possible similarity between the background and dirt, leading to some background instances being incorrectly classified as dirt.

In summary, the improved model excels in detecting the “damage” category but faces challenges in predicting the “dirty” and “background” categories, particularly distinguishing between the two. The main issue of misclassification arises between dirt and background, particularly the misclassification of dirt as damage. This may stem from the visual similarity between dirt and background or the morphological similarity between the damaged area and the background in the image.

In summary, the improved model has achieved strong results in wind turbine blade damage detection, especially in detecting damage. However, to further enhance the model’s performance, particularly in distinguishing between dirt and background, additional optimizations may be necessary, such as incorporating stronger feature extraction capabilities or applying image augmentation techniques to enhance small object recognition accuracy.

Loss value comparison and analysis

The comparison of the loss curves, shown in Fig. 8, reveals that the YOLO-Wind model outperforms the original YOLOv8 model in both the training and validation phases, particularly in optimizing deep focal mismatch. Specifically, YOLO-Wind exhibits a faster decrease in both train/dfl_loss and val/dfl_loss, with loss values eventually stabilizing at lower levels. This suggests that YOLO-Wind converges faster and is better suited for multi-scale object detection tasks. The model demonstrates strong optimization capabilities for deep focal mismatch, enabling more precise detection and optimization of multi-scale objects, thereby improving performance in complex feature handling.

However, YOLO-Wind and YOLOv8 exhibit similar performance in train/box_loss and val/box_loss, indicating comparable performance in object localization tasks. Although YOLO-Wind shows improvements in deep focal mismatch, no substantial gain in localization accuracy is observed. Similarly, the differences in train/cls_loss and val/cls_loss are minimal, indicating limited improvements in classification tasks.

Overall, YOLO-Wind excels in multi-scale object detection and deep focal mismatch optimization; however, improvements in object localization and classification accuracy remain modest. This suggests that while YOLO-Wind addresses deep focal mismatch more effectively and exhibits better adaptability to multi-scale features, further advancements in localization accuracy and classification tasks are required.

In the loss curves shown in Fig. 8, YOLO-Wind (orange line) demonstrates a faster loss decrease during both the training and validation phases compared to YOLOv8 (blue line). Specifically, in the train/box_loss, val/box_loss, train/dfl_loss, val/dfl_loss, train/cls_loss, and val/cls_loss curves, YOLO-Wind exhibits a faster decline in loss and reaches a lower stable loss value. This suggests that YOLO-Wind not only converges more quickly but also demonstrates higher optimization efficiency across all loss metrics. In contrast, YOLOv8 shows a slower loss decrease and higher final stable loss, suggesting that YOLO-Wind may have better adaptability or more effective training strategies for this task, resulting in more efficient parameter optimization. In conclusion, YOLO-Wind exhibits faster convergence and lower stable loss across all metrics, demonstrating superior performance compared to YOLOv8.

PR curve analysis

Fig. 9 illustrates the performance comparison between the baseline YOLOv8 model and the proposed YOLO-Wind across four key metrics: Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95.

As shown in the figure, both models exhibit convergence and performance stabilization after approximately 150 epochs. However, the proposed YOLO-Wind model consistently outperforms the baseline YOLOv8 in all metrics. In particular, YOLO-Wind achieves a slightly higher and more stable Precision curve in the later epochs, and a notably higher Recall, indicating improved capability in identifying more true defect instances.

The mAP@0.5 curve shows that YOLO-Wind achieves faster convergence during the early training phase and maintains a marginal but consistent performance advantage over the baseline. The advantage becomes more evident in the mAP@0.5:0.95 metric, where YOLO-Wind demonstrates better localization performance across a broader range of IoU thresholds, which is especially valuable for detecting small-scale or complex surface defects on wind turbine blades.

Although the absolute improvement margins may appear moderate, these gains are meaningful in real-world scenarios where minor accuracy enhancements can significantly reduce false negatives and improve inspection reliability. The improved stability, faster convergence, and enhanced fine-grained detection collectively validate the effectiveness of the architectural enhancements introduced in YOLO-Wind.

Data visualization results analysis

As shown in Fig. 10, the model performs well in detecting both wind turbine blade damage and dirt regions, accurately identifying most damage and dirt areas. For the damage regions, the model effectively identifies significant damage and assigns high damage scores, typically ranging from 0.8 to 0.9. This suggests that the model can detect severe damage, such as cracks or delaminations. However, some damage regions exhibit lower scores (e.g., 0.3), likely due to the subtle nature of the damage or quality issues with the images, where the damage is less visible and, therefore, misclassified as minor damage.

Additionally, the model detects several dirt regions, with scores typically ranging from 0.8 to 0.9, indicating its effective identification of dirt on the blade surface and providing accurate assessments. However, dirt can sometimes cause confusion in damage detection, particularly in heavily soiled areas, which can affect the precise marking of damage regions, leading to some misclassifications. For example, in some images, dirt regions with high scores may be mistakenly confused with damage regions, influencing the determination of damage.

Overall, the model performs well in most cases, particularly in the accurate detection of severe damage. However, its accuracy decreases when dealing with minor damage or dirt-covered areas, particularly when the damage is less severe or when the dirt is extensive. In these cases, the model’s detection results may be affected. Therefore, future improvements could focus on enhancing the model’s robustness in these mixed regions, enabling it to better distinguish between minor damage and dirt, thereby further improving the model’s overall performance.

Visual comparative analysis of model improvements

To further validate the superiority of the proposed YOLO-Wind model in real-world detection scenarios, a visualization comparison experiment was conducted using randomly selected samples from the Wind Turbine Surface Damage dataset. As shown in Fig. 11, three representative images were selected to provides a side-by-side visualization of detection attention maps from five models—YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, YOLOv8, and the proposed YOLO-Wind—across three challenging defect scenarios.

In case (a), which includes fine cracks with low contrast, all baseline models produce widespread or ambiguous attention areas, failing to localize the defect precisely. YOLO-Wind, in contrast, generates a sharply focused response directly on the crack edges, indicating superior fine-grained feature sensitivity.