Abstract

The infectivity and virulence of Metarhizium pingshaense was tested against three major pests: Chilo infuscatellus (sugarcane early shoot borer), C. sacchariphagus indicus (sugarcane internode borer) and C. partellus (sorghum stem borer). Bioassay studies indicated high pathogenicity of this fungus against all the three species with the highest mortality recorded in C. sacchariphagus indicus (96%), followed by C. infuscatellus (93%) and C. partellus (83%). The median lethal concentrations of M. pingshaense against late-instar larvae were 4.6 × 105, 1.7 × 105, and 9.5 × 105 conidia/ml for C. infuscatellus, C. sacchariphagus indicus, and C. partellus, respectively. Median survival times ranged from 5.3 to 6.9 days for C. infuscatellus, from 5.4 to 7.9 days for C. sacchariphagus indicus, and from 6.9 to 8.3 days for C. partellus, at the tested doses of 1 × 10⁸ and 1 × 10⁷ conidia/ml. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of cuticle-degrading enzymes by the fungus, which are critical virulence factors, confirmed the production of chitinases and lipases. Enzyme production significantly increased in media with insect cuticle, indicating substrate-dependent regulation. Genes encoding chitinase and protease were cloned, sequenced, and were found to be closely related to those of M. anisopliae. RT-PCR studies confirmed the temporal expression of these two virulence genes, which play a critical role in pathogenesis. There was a gradual upregulation of these genes in the fungus during infection of its original host, Conogethes punctiferalis with the progression of time rising up to 3000-fold compared to untreated insects. These findings highlight the potential of M. pingshaense as an effective biocontrol agent for a wide range of crambid pests, supporting its development as a broad-spectrum mycoinsecticide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lepidopteran borers, particularly those belonging to the Crambidae family, include some of the most destructive pests of agricultural and horticultural crops worldwide. Due to their cryptic nature, these pests often remain undetected during the early stages of infestation, posing significant challenges to their management1. Among the various genera within the Crambidae family, the genus Chilo Zincken comprises several species whose larval stages are major agricultural pests, affecting the yield of staple crops such as rice, sugarcane, maize, and sorghum. These pests cause considerable economic losses and are widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions, including Africa, Asia, Southern Europe, South America, and Oceania2. Prominent species of this genus include Chilo suppressalis (Asian rice borer), C. partellus (sorghum stem borer), C. infuscatellus (sugarcane early shoot borer), and C. sacchariphagus indicus (sugarcane internode borer)3,4,5,6. These pests primarily cause damage to crops by boring into plant stems, leading to dead-heart symptoms, resulting in reduction in quality and yield, causing substantial crop losses. Although chemical pest control options are available, their adverse effects on the environment and non-target organisms underscore the importance of biological control strategies as a more sustainable and eco-friendly solution for managing these pests.

Among the biological control agents (BCAs) available for the management of insect pests, entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) are considered promising alternatives to chemical pesticides. They are widely distributed across various ecosystems, possess a broad host range, and act as natural regulators of insect pests in the environment. Unlike bacteria and viruses, EPF do not need to be ingested by the insect to initiate infection; the mere attachment of a viable conidium on the cuticle surface of a susceptible host is sufficient to trigger infection, thus acting as contact biopesticides. Strains of various entomopathogenic fungal species belonging to the genera Metarhizium, Beauveria, Lecanicillium, and Isaria have been successfully developed as commercial mycoinsecticides worldwide for managing pests of agricultural, veterinary, and medical importance7. Among these, the genus Metarhizium Sorokīn is a highly diverse and globally distributed group of fungi, comprising over 60 described species. It is a well-known pathogen of several major crop pests and has been successfully utilized in various biocontrol programs8. At least 11 species from this genus have been commercially exploited, and more than 34% of the commercially available mycoinsecticides belong to this genus alone, indicating its insecticidal potential and applicability across diverse agro-ecosystems9,10.

Entomopathogenic fungi exhibit varying degrees of host specificity, ranging from broad-spectrum hyphomycetes pathogens like B. bassiana, M. anisopliae and I. fumosorosea that can infect hundreds of insect species across multiple orders11,12, to highly specialized pathogens like entomophthoralean fungi, which are more host-specific and are obligate pathogens13. The host range of a fungus is determined by a complex interplay of factors, including fungal genetics, host cuticular properties, environmental conditions, and host immune responses. The molecular basis of host specificity involves specific recognition patterns, enzyme production, the ability to overcome host defences, genome composition, and horizontal gene transfer14,15,16. Fungi with a broader host range have more gene content and a complex gene regulation to degrade diverse cuticle types, detoxify host-specific compounds, and synthesize toxins for different hosts16. Understanding host range is crucial for biological control applications, as it influences both the efficacy against target pests and the potential impacts on non-target organisms17.

The penetration of the insect cuticle by EPF is a critical step in initiating pathogenesis in insects. The insect cuticle is mainly composed of proteins, chitin, and lipids, which act as a protective shield against invading pathogens. Fungal pathogens employ a combination of physical pressure, exerted through the formation of an appressorium on the host’s cuticular surface, and an array of hydrolytic enzymes, such as proteases, chitinases, and lipases, to penetrate the host cuticle18,19. Proteases play a pivotal role by breaking down proteins in the cuticle, which serve as a primary nutrient source for fungal germination and growth20. Chitinases target chitin, a key structural component of the cuticle, to aid fungal invasion while releasing carbohydrates for fungal nutrition18,21,22. Lipases contribute by hydrolyzing ester bonds in lipids, fats, and waxes, thereby enhancing fungal attachment, penetration, and development23. These extracellular enzymes are expressed sequentially and act synergistically to ensure the successful breach of the insect integument, followed by colonization and proliferation within the hemocoel22. The expression of these enzymes underscores the virulence of EPF and highlights their potential use as commercial biopesticides17,24.

Despite the proven efficacy of EPF in managing pest populations, some limitations hinder their widespread adoption as reliable biocontrol agents. Many EPF strains exhibit a narrow host range, which limits their applicability across different pest species25. Moreover, environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and UV radiation can significantly affect fungal viability and infectivity under field conditions26,27. Repeated application of certain biocontrol agents may also lead to resistance development in pest populations, thereby reducing long-term efficacy28. The present study investigates the pathogenicity of Metarhizium pingshaense, a promising EPF species known for its broader host infectivity and increased tolerance to abiotic stress1,29 against Chilo spp. We report the infective potential of M. pingshaense, previously isolated from Conogethes punctiferalis1, against three major crambid stem borers: Chilo infuscatellus, C. sacchariphagus indicus, and C. partellus, which are globally significant agricultural pests.

The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate the physiological host range of the fungus by testing its pathogenicity and virulence against these pests through laboratory bioassays; (2) investigate the infection mechanism by estimating the cuticle-degrading enzymes (CDEs) produced by the fungus; and (3) analyze the expression of these enzyme associated genes in its original host, C. punctiferalis over the course of infection using molecular tools. We hypothesized that confamilial insect species may exhibit susceptibility to a fungal isolate derived from a member of the same family with a similar lifestyle. The findings are discussed in the context of the potential of the fungus as a broad-host-range pathogen and its prospects for development into a biopesticide for use in sustainable agricultural systems.

Materials and methods

Insects

Artificial rearing of Chilo spp.

Laboratory populations of three Chilo species: Chilo infuscatellus (Fig. 1A), C. sacchariphagus indicus (Fig. 1B), and C. partellus (Fig. 1C) were established from field-collected late instar larvae of each species, and the subsequent generation reared on an artificial diet was used for bioassays. Field-collected C. infuscatellus larvae were reared in plastic boxes (6.5 × 9.0 cm), fed with tender shoots of sugarcane, and maintained at 27 ± 2 °C, 60–70% relative humidity (RH), with a 12:12 h day-night photoperiod until pupation. Pupae were sexed and kept separately until adult emergence. Upon emergence, 10 pairs of adults were released into oviposition cages (50 cm × 50 cm × 75 cm) for mating and egg-laying. The insects were provided with sugarcane midribs for egg-laying and fed with 10% honey solution. Leaf bits with eggs were collected daily, surface-sterilized with 0.5% sodium hypochlorite for 60 s, and kept for larval emergence6. After emergence, neonate larvae were transferred to 15 ml glass vials (three neonates per vial) half-filled with artificial diet30 and maintained until they reached the fifth instar for further studies. Similarly, C. sacchariphagus indicus and C. partellus were field-collected and reared on their respective hosts, and the second-generation fifth instar larvae reared on artificial diet were used for bioassay studies.

Fungus source

Metarhizium pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 was originally isolated from naturally infected C. punctiferalis cadavers found in turmeric plants, as detailed elsewhere1. For bioassay experiments, a pure culture of this fungus, available in the Entomopathogenic Repository of ICAR-IISR, was utilized. Sequence data for various conserved gene regions of the fungus are accessible in the NCBI database, with the GenBank accession numbers MK537396 for the partial internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and MK583958 – MK583961 for the translation elongation factor (TEF), RNA polymerase II largest subunits (RPB1, RPB2), and DNA lyase (APN) respectively.

Preparation of fungal spore suspension

The fungus was grown on petri dishes (100 × 17 mm) containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) media at 26 ± 1 °C for 2 weeks. Conidia were harvested by scrapping the surface with a sterile scalpel and suspended in 10 mL of sterile 0.05% Triton-X 100. The spore suspension was passed through a double-layered muslin cloth to remove fungal debris, and the final spore concentration was adjusted to 109 conidia/ml using an improved Neubauer hemocytometer. Spore viability was checked prior to use, and it was found to be more than 95%. Bioassays for different insects were conducted each time with freshly prepared spore suspension.

Bioassays

Two sets of bioassay experiments were conducted for each insect species at a time (i) to determine the median lethal concentration (LC50) of the fungus, and (ii) to assess the median survival time (MST) of the insects infected by the fungus. The LC50 studies were conducted with four conidial concentrations: 105, 106, 107 and 108 conidia/ml, while two concentrations, 107 and 108 conidia/ml were tested for MST studies against early fifth instar of three Chilo spp. Groups of 10 insects of each Chilo spp. were dipped in each concentration of the fungus for 30 s and then transferred to plastic containers (500 ml) lined with a filter paper at the bottom placed above a layer of cotton. A similar number of insects treated with sterile 0.05% Triton® X-100 solution served as control. Each treatment was replicated three times, and the insects were treated with conidial suspensions prepared separately for each replication1. Treated insects were fed with natural diet, i.e., sugarcane shoots for C. infuscatellus and C. sacchariphagus indicus and sorghum shoots for C. partellus, and maintained at 28–32 ± 2 °C, 60–70% relative humidity, and a 12:12 h day: night photoperiod under ambient room conditions. Insect mortality in the experiments was recorded at 24 h intervals for LC50 studies and at 12 h intervals for MST studies, up to 15 days post-inoculation (p. i.). Dead insects were surface sterilized and re-isolated by inoculating them on PDA1. The experiments were repeated with freshly prepared fungal spore suspension to confirm the results.

Assay for cuticle degrading enzymes

The enzymatic activity of M. pingshaense was assessed using both qualitative (plate) and quantitative (broth) assays for chitinase, protease, and lipase. All experiments were conducted in triplicate unless stated otherwise.

Plate assays

To screen for extracellular enzyme activity, 6 mm agar plugs from 15-day-old fungal cultures grown on PDA were inoculated onto specific agar media and incubated at 26 ± 1 °C in a BOD incubator.

-

Chitinase: Chitin agar (pH 6.0) consisted of (g/L): 10 g colloidal chitin, 5 g (NH₄)₂SO₄, 0.5 g MgSO₄·7H₂O, 2.4 g KH₂PO₄, 0.6 g K₂HPO₄·3H₂O, and 15 g agar per litre31. Media without colloidal chitin served as control. Chitinolytic activity was indicated by a clear zone surrounding the fungal colony at 7 DAI.

-

Protease: Casein agar contained (g/l): 10 g casein, 1 g glucose, 1 g yeast extract, 1 g K₂HPO₄, 0.5 g KH₂PO₄, 0.1 g MgSO₄, and 20 g agar32. Control plates lacked casein. Proteolytic activity was indicated by the formation of a hydrolysis ring 24 h after incubation.

-

Lipase: Tributyrin agar (pH 8.0) was composed of 1% tributyrin, 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g NaCl, 0.1 g phenol red, and 20 g agar33. Lipolytic activity was identified by the presence of a clear halo zone 15 DAI.

Broth assays

For quantitative enzyme estimation, 6 mm mycelial discs were inoculated into 50 ml of specific broth media, and incubated at 120 rpm. Culture filtrates were collected at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 days after inoculation (DAI), filtered, and centrifuged to obtain crude enzyme. Protein content was determined by Lowry’s method using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard.

-

Chitinase: Cultures were grown in chitin broth (pH 5.5) containing 15 g colloidal chitin, 0.5 g yeast extract, 1 g (NH₄)₂SO₄, 0.3 g MgSO₄·7H₂O, and 1.36 g KH₂PO₄ at 26 ± 1 °C. Chitinase activity was measured using a modified method of Yanai et al.34. The reaction mixture, comprising 250 µl of 0.5% colloidal chitin, 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0), and 500 µl of enzyme solution, was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After brief centrifugation (2460 × g, 2 min, room temperature), 500 µl of the supernatant was mixed with 100 µl of 0.8 M boric acid. The pH was adjusted to 10.2 with KOH, followed by heating for 3 min in boiling water. After cooling, 3 ml of DMAB reagent (1 g p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in 100 ml glacial acetic acid with 1% v/v HCl) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Absorbance was read at 585 nm against a water blank. One unit of chitinase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that releases 1 µmol of N-acetylglucosamine per minute under the assay conditions.

-

Protease: Fungal discs were inoculated into basal salts medium containing 1 g/L casein35 and incubated at 28 ± 1 °C. Total protease activity was assessed using casein as a substrate and quantified by Folin–Ciocâlteu reaction36. Subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) activities were determined using N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide and N-Benzoyl-Phe-Val-Arg-p-nitroanilide, respectively37. Absorbance was recorded at 660 nm for total protease and at 410 nm for Pr1/Pr2 activity. One unit of protease or Pr1/Pr2 activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 mM tyrosine or p-nitroanilide per minute.

-

Lipase: Mycelial discs were inoculated in minimal broth (pH 5.0) containing 4 g NaNO₃, 2 g KH₂PO₄, 1 g MgSO₄·7H₂O, and 4% (v/v) coconut oil or olive oil (in separate experiments) and incubated at 26 ± 1 °C. On day 4, 0.25% Triton X-100 was added and filtrates were collected on 6, 8, 10, 12, and 15 DAI. Enzyme activity was measured using p-nitrophenyl palmitate (pNPP) as the substrate38. The release of p-nitrophenol was quantified spectrophotometrically at 420 nm. One unit of lipase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 µmol of p-nitrophenol per minute.

Assay for cuticle degrading enzymes in insect cuticle amended media

Extracellular enzyme production in media supplemented with insect cuticle of its original host, C. puntiferalis was conducted using the following composition (g/l): 0.02 g KH2PO4, 0.01 g CaCl2, 0.01 g MgSO4, 0.02 g Na2HPO4, 0.01 g ZnCl2 and 0.01 g yeast extract5. The media was supplemented with 1% cuticle extract from C. punctiferalis larvae, inoculated with mycelial disc (6 mm) of M. pingshaense, and maintained in an incubator at 26 ± 1 °C with shaking at 120 rpm. Media without cuticle extract served as the control. After 5 days of incubation, the culture filtrates were centrifuged at 9,838 g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was used as crude enzyme for the estimation of various CDEs as described above.

Cloning and sequencing of chitinase and protease genes

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

Genomic DNA of the fungus was extracted from approximately 500 mg of 1-week old culture using fungal genomic DNA extraction Kit (Chromous Biotech, India) following manufacturer’s instructions. Gene specific primers were used to amplify partial sequences chitinase and protease genes. Chitinase gene region was amplified using Meta_Chit1_comp forward (5ˊ-TCCCATGTTCTGTACTCGTTC-3ˊ) and Meta_Chit1_comp reverse (5ˊ-CCCTTGCTCTTGAGGTAGGTAAC-3ˊ)21. Protease gene was amplified using a degenerate primer set, Prot-IISR-F (5ˊ-GACTTCGTTTACGAGCACRCCWY-3ˊ) and Prot-IISR-R (5ˊ-RWAGTCCATGCCACTGAKGATRC-3ˊ) designed from the conserved gene region of Metarhizium spp. protease genes available in NCBI database. PCR reactions were carried out with 10–20 ng of template DNA in volumes of 25 µl containing 12.5 μl of 2 × PCR TaqMixture (HiMedia®, India), 0.75 μl each of (20 μM) forward and reverse primer pairs, after making the remaining volume with PCR grade water (HiMedia®, India). The PCR conditions for chitinase and protease genes were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min, 57 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min.

The amplified bands were excised, purified using QIAquick® gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and ligated into TA cloning vector pTZ57R/T, and transformed into competent Escherichia coli strain DH5α using Thermo Scientific™ InsTAclone™ PCR Cloning Kit. The selected recombinant plasmids after DNA extraction using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) was confirmed for inserts by PCR (M13 F & R primers) and double restriction endonuclease digestion (Eco RI & Hind III). Positive clones were sent to Eurofins Genomics, India, Pvt. Ltd., for bi-directional sequencing using the same set of PCR primers. Sequences were manually trimmed using BioEdit software and subjected to BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search to identify matching sequences deposited in GenBank database. The partial chitinase and protease gene sequences of M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 were submitted in GenBank with accession numbers, PP109068 and PP109069, respectively. The conserved domain of the ORF was analyzed using the Conserved Domain Search tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) available from NCBI.

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences of chitinase and protease genes of M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 and relevant sequences of other Metarhizium spp. from the GenBank database were aligned in Clustal W Multiple alignment tool separately prior to phylogenetic analysis. Neighbor-joining trees were constructed using Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model and Dayhoff plus Gamma (G) for chitinase and protease genes respectively, based on the lowest score values of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) available in MEGA X39. Bootstrapping was performed with 1000 replicates and the gaps in alignment were treated as missing data. Pochonia chlamydosporia var. chlamydosporia (Goddard) Zare et W. Gams (Metacordycipitaceae) was used as outgroup.

In vivo expression of Metarhizium pingshaense virulence genes in infected insects

The relative expression of two pathogenesis-associated genes, chitinase and protease, in C. punctiferalis infected by M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 was evaluated using reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR). For this study, laboratory-reared late fourth instar larvae of C. punctiferalis (n = 40) were treated with M. pingshaense spore suspension obtained from a 2-week-old culture grown on PDA, as described earlier in Section"Bioassays". The gene expression was estimated at different time intervals: 72, 96, and 120 h after treatment. Groups of 10 insects were dipped in 3 ml of spore suspension (1 × 108 conidia/ml) for 30 s and transferred to plastic containers (500 ml) containing turmeric pseudostem pieces placed on a filter paper layer above cotton. Insects treated with sterile 0.05% Triton® X-100 solution served as control and were used as the 0-h sample. Insects collected at different time intervals were individually immersed in RNA later™ stabilization solution (Invitrogen), stored at 4 °C overnight, and subsequently transferred to −20 °C for long-term storage. Total RNA was isolated from three infected and control samples using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA purity and concentration were assessed spectrophotometrically using a Nanodrop Microvolume Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific), and integrity was confirmed on a 1% agarose gel.

Reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) reactions were performed in a Rotor-Gene Q platform (QIAGEN) with 250 ng of total RNA, 12.5 µl QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), 1.0 µl each of gene-specific forward and reverse primers designed using Primer3web version 4.1.0 (https://primer3.ut.ee) from M. pingshaense protease and chitinase genes, 0.5 µl RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific™), and the remaining volume made up with PCR-grade water (HiMedia®, India). The qPCR primers used for protease were q-Prot-IISR-F1 (5ˊ-CGTAAGTTGTGCCGCCAAAA-3ˊ) and q-Prot-IISR-R1 (5ˊ-CCGTGGCCATCAGTTTGTTG-3ˊ), while those used for chitinase were q-Chit-IISR-F2 (5ˊ-ATTCTCTGGTGTTGGCGACG-3ˊ) and q-Chit-IISR-R2 (5ˊ-ACCCTTTGCCACGTCATCAT-3ˊ). The endogenous control, the actin gene, was detected using the primer pair q-Actin F2-CP (5ˊ-TCCATCATGAAGTGCGACGT-3ˊ) and q-Actin R2-CP (5ˊ-CTCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCGG-3ˊ). The 3-step cycling conditions for RT-qPCR were: reverse transcription for 30 min at 50 °C, polymerase activation for 15 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. Each target gene was analyzed with three biological replicates and two technical replicates. Primer efficiency was averaged across all PCR reactions for each primer, and the cycle threshold (Ct) value was averaged from the two technical replicates. The relative expression of each target gene was calculated using the ΔΔCT method40, in comparison with the control treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data from insect bioassays were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the general linear model (GLM). Mean comparisons were carried by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test (α = 0.05) in GraphPad Prism® Version 7.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California, USA. As there was no control mortality, Abbott’s correction was not applied for treatments. The median lethal concentration (LC50) of the fungus to kill the insects was done by probit analysis using IBM® SPSS® (Statistical Package for Social Science, IBM, Armonk New York, USA) Statistics Version 25.0 for windows. The web-based programme, Online Application for Survival Analysis 2 (OASIS 2), developed by Han et al.41 was used to ascertain the median survival time (ST50) of the insects in each treatment based on Kaplan–Meier survival distribution function. All the experiments were repeated to confirm the results.

Results

Laboratory bioassays

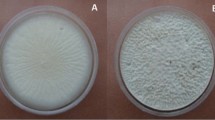

The fungus caused significant mortality in all the three tested Chilo species. The infected insects exhibited signs of mycosis typical of M. pingshaense (Fig. 2 A, B, C). No mortality was observed in the control group, where the insects pupated normally. In C. infuscatellus, larval mortality was significant across the tested doses (F = 116; P < 0.0001; df = 4, 10), ranging from 33.3 ± 3.3% to 93.3 ± 3.3% (mean ± SE) (Fig. 3A). For C. sacchariphagus indicus, larval mortality (mean ± SE) ranged from 43.3 ± 3.3% to 96.7 ± 3.3% at different doses, with significant differences observed among the doses tested (F = 50; P < 0.0001; df = 4, 10) (Fig. 3B). Similarly, in C. partellus, mortality varied significantly (F = 85.6; P < 0.0001; df = 4, 10), with mean mortality ranging from 26.7 ± 3.3% to 83.3 ± 3.3% (Fig. 3C).

The median lethal concentration (LC50) of the fungus against late instar larvae of three Chilo species was 4.6 × 105, 1.7 × 105, and 9.5 × 105 conidia/ml for C. infuscatellus, C. sacchariphagus indicus, and C. partellus, respectively. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) ranged from 1.4 × 105 to 1.1 × 106, 3.1 × 104 to 4.5 × 105, and 2.1 × 105 to 2.8 × 106 conidia/ml, respectively, for these three Chilo species (Table 1).

The median survival time (MST) of late instar larvae of three Chilo species differed significantly between the two tested doses (Log-rank test; P < 0.05). For C. infuscatellus, the MST at the highest dose of 1 × 108 conidia/ml was 5.3 days (± 0.38 SE), with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 4.7 to 6.0 days, while at the dose of 1 × 107 conidia/ml, the MST was 6.9 days (± 0.35 SE), with a 95% CI of 6.2 to 7.6 days (Table 2 and Fig. 4A). Similarly, for C. sacchariphagus, the MST at the highest dose of 1 × 108 conidia/ml was 5.4 days (± 0.28 SE), with a 95% CI of 4.8 to 5.9 days, whereas at the dose of 1 × 107 conidia/ml, the MST was 7.9 days (± 0.49 SE), with a 95% CI of 6.9 to 8.9 days (Table 2 and Fig. 4B). In the case of C. partellus, the MST at the highest dose of 1 × 108 conidia/ml was 6.9 days (± 0.37 SE), with a 95% CI of 6.2 to 8.0 days, whereas at the dose of 1 × 107 conidia/ml, the MST was 8.3 days (± 0.40 SE), with a 95% CI of 7.5 to 9.0 days (Table 2 and Fig. 4C).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for early fifth instar larvae of three Chilo species: (A) C. infuscatellus, (B) C. sacchariphagus indicus, and (C) C. partellus treated with Metarhizium pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 at concentrations of 1 × 107 and 1 × 108 conidia/mL. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05) according to the log-rank test.

Assay for cuticle degrading enzymes

Production of cuticle degrading enzymes in substrate specific media

In the preliminary chitinase plate assay, the fungus produced a clear zone around the colony 24 h after incubation by degrading the colloidal chitin exhibiting its potential to produce chitinases (Fig. 5A). Chitinase activity in liquid media amended with colloidal chitin gradually increased from 0.02 ± 0.003 U/mg at 3 DAI, reached its peak activity on 10 DAI (0.03 ± 0.003 U/mg) and then decreased afterward (Fig. 5B).

Qualitative and quantitative estimation of various cuticle-degrading enzymes produced by Metarhizium pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 on solid media and in broth amended with specific substrates. Chitinase activity assay showing (A) formation of a clear zone around the fungal colony on solid media amended with 0.1% colloidal chitin 7 days after inoculation (DAI) and (B) specific activity (U/mg) of chitinase in liquid media amended with 0.15% colloidal chitin at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 DAI. Protease activity assay showing (C) formation of a hydrolysis ring around the fungal colony on solid media amended with 1% casein 24 h after incubation and (D) specific activity (U/mg) of total protease, subtilisin-like (Pr1), and trypsin-like (Pr2) enzyme activities in basal salts medium amended with 0.1% casein at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 DAI. Lipase activity assay showing (E) appearance of a clear zone around the fungal colony on 1% tributyrin agar media 15 DAI and (F) specific activity (U/mg) of lipase in minimal broth media amended with 4% (v/v) olive or coconut oil at 6, 8, 10, 12, and 15 DAI.

Initial screening for protease activity by the fungus on casein agar plates showed rapid hydrolysis of casein, evidenced by the formation of clear hydrolysis ring around the colony within 24 h after inoculation (Fig. 5C). Total protease activity in liquid media amended with casein increased from 1.5 ± 0.17 U/mg on 3 DAI, and reached its peak activity on 5 DAI (11.1 ± 0.46), followed by a rapid decline in the activity over time (Fig. 5D). The mean peak activities of specific proteases, including Subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) enzymes, from culture filtrates were 8.4 ± 1.21 and 3.1 ± 0.50 U/mg, respectively, on 3 DAI, which rapidly decreased with the progress of time (Fig. 5D).

The fungus was also positive for the production of lipase, as indicated by the clear halo zone around the colony on tributyrin agar plates (Fig. 5E). Spectrophotometric analyses of the basal media amended with vegetable oils showed that the highest lipase production was recorded on 10 DAI, which was 0.97 ± 0.05 and 1.0 ± 0.28 U/mg, for coconut and olive oils, respectively. The production of lipases in the basal media declined gradually with the progress of time (Fig. 5F).

Production of cuticle-degrading enzymes in cuticle amended media

Experiments conducted to assay the production of various CDEs in basal media amended with 1% cuticle extract of C. punctiferalis confirmed the secretion of enzymes such as chitinases, proteases, and lipases by the fungus. The production of chitinase and lipase in the media reached 0.89 ± 0.05 and 0.39 ± 0.08 U/mg, respectively, on 5 DAI. The total protease produced was 51.4 ± 3.05 U/mg, while specific proteases like subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) enzymes, in the culture filtrates were 9.13 ± 0.52 and 3.76 ± 0.19 U/mg, respectively (Table 3).

Sequencing and characterization of chitinase and protease genes

Sequencing of chitinase gene of M. pingshaense using degenerate primers yielded an amplicon of size 870 bp, encoding for 290 amino acid residues. Analysis of the ORFs for conserved domain indicated that the sequenced chitinase gene belongs to the glycoside hydrolase family 18 protein (domain architecture ID 12,217,520), similar to chitinase, which catalyzes the random endo-hydrolysis of the 1, 4-beta-linkages of N-acetylglucosamine in chitin and chitodextrins. Protein homology search with the translated protein sequence of the of the partial chitinase gene showed highest similarity (97.6%) with M. anisopliae isolates, BRIP 53,293 and 53,284 (KJK82108 and KJK95695), respectively. Moreover, the sequence shared more than 90% similarity with chitinase genes of other Metarhizium species such as M. humberi (KAH0599693), M. robertsii (XP_007818874), M. brunneum (KAK9445903), M. majus (KIE02515), M. guizhouense (KID88770), M. acridum (XP_007815094) etc. The Neighbor-joining tree generated using deduced amino acid sequences of chitinase genes of various entomopathogenic fungi showed that the M. pingshaense chitinase sequence clustered with chitinase genes of various Metarhizium species with strong boot strap support, while being distinctly different from M. rileyi and the outgroup, P. chlamydosporia (Fig. 6).

Neighbor-joining tree based on amino acid sequences of the partial chitinase gene from different Metarhizium species, illustrating the relationship with the M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 chitinase gene. Numbers above or below the nodes represent bootstrap values generated from 1000 replications using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model, based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) scores in MEGA X. Pochonia chlamydosporia was used as the outgroup.

The subtilisin-like protease gene of M. pingshaense was amplified using gene-specific primers, resulting in an amplicon of 579 bp that encodes 149 amino acid residues. The amplified protein belongs to the conserved protein domain families S8 (subtilisin and kexin) and S53 (sedolisin) superfamilies, which include endopeptidases and exopeptidases. Protein homology search for the deduced amino acid sequence of the partial protease gene showed 97.99% similarity with Pr1 proteins of M. anisopliae (Accession nos. BAB70704, ACT66137, AAR26030, ACV71840, ACV71832, and XP_066817309) and M. humberi (KAH0601022). The protein sequence also shared more than 90% similarity with other Metarhizium species, such as M. robertsii (XP_007821864), M. brunneum (XP_014549317), M. acridum (AAR26026), M. majus (ACV71847), and M. guizhouense (KID91211), etc. Phylogenetic analysis of the protease genes indicated clustering of M. pingshaense with M. anisopliae and M. humberii with strong bootstrap support, while being distinctly different from M. album, M. rileyi, and the outgroup P. chlamydosporia (Fig. 7).

Neighbor-joining tree based on amino acid sequences of the partial subtilisin-like protease gene from different Metarhizium species, illustrating the relationship with the M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 protease gene. Numbers above or below the nodes represent bootstrap values generated from 1000 replications using the Dayhoff plus Gamma (G) model, based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) scores in MEGA X. Pochonia chlamydosporia was used as the outgroup.

In vivo expression of Metarhizium pingshaense virulence genes in infected insects

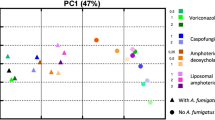

The relative expression of the chitinase and protease genes in C. punctiferalis infected by M. pingshaense was analyzed over time, at 72, 96, and 120 h post-infection (hpi). It was observed that the expression of virulence and pathogenesis-associated genes was significantly upregulated as the infection progressed in the insects. At 72 hpi, the relative expression of the chitinase gene remained low, showing no significant change compared to untreated control. By 96 hpi, an increase in gene expression compared to 72 hpi was observed. A significant up-regulation of chitinase gene was observed at 120 hpi, with levels rising more than 2900-fold compared to untreated control (F = 38.23; P < 0.0001; df = 3, 8) (Fig. 8A).

Relative expression levels of (A) chitinase and (B) protease genes in Conogethes punctiferalis infected by Metarhizium pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 at 72, 96, and 120 h post-infection. The relative expression of each target gene was calculated according the ΔΔCT method using actin gene as endogenous control. Values represent the mean of two technical and three biological replicates. Bars with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05).

Similarly, the relative expression of the protease gene in infected insects remained significantly low during the initial time points. A gradual increase in gene expression was observed up to 96 hpi but was not statistically significant. However, by 120 hpi, a substantial upregulation of the protease gene was observed, with expression levels rising more than 3000-fold compared to control, which was significantly higher than the earlier time points (F = 37.2; P < 0.0001; df = 3, 8) (Fig. 8B).

Discussion

Knowledge about the host range of EPF is essential for evaluating their economic potential and ensuring safety for non-target organisms17. While an organism’s ecological host range is assessed under field conditions, the physiological host range of EPF is primarily determined through laboratory assays. These assays assess pathogenicity and virulence based on host mortality, mean survival time, and mycosis17,42,43. Bioassays, in particular, are the most reliable way to test EPF’s virulence and host range35. In our studies, M. pingshaense demonstrated significant pathogenicity against all tested Chilo species, with mortality rates among late-instar larvae ranging from 83.0% to 96.0% at the highest tested doses. The highest mortality was observed in C. sacchariphagus indicus (96%), followed by C. infuscatellus (93%) and C. partellus (83%). Previously, this strain caused 86% mortality in its originally isolated host, C. punctiferalis1. In India, a strain of M. pingshaense has been reported to infect another significant crambid pest of rice, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis44. This fungus has also been reported to infect several economically important pests, including Ectropis obliqua and Myllocerinus aurolineatus on tea45,46, Anomala cincta on maize47, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus on palms48, termites49, and mosquitoes50. The ability of M. pingshaense to infect a diverse array of insect pests across multiple insect orders and agro-ecosystems underscores its broad host range, adaptability, significant commercial potential and suitability for inclusion in integrated pest management (IPM) strategies.

The virulence of EPF can be directly assessed through time-mortality and dose-mortality assays51. Requirement of lesser concentration of conidia and shorter time to kill the host has been attributed as key indicators to ascertain the virulence of an entomopathogen5,24. In our studies, the median lethal concentrations (LC50) of M. pingshaense against late-instar larvae of C. infuscatellus, C. sacchariphagus indicus, and C. partellus were 4.6 × 105, 1.7 × 105, and 9.5 × 105 conidia/ml, respectively. The median survival time (MST) for C. infuscatellus ranged from 5.3 to 6.9 days, for C. sacchariphagus indicus from 5.4 to 7.9 days, and for C. partellus from 6.9 to 8.3 days at the tested doses of 1 × 108 and 1 × 107 conidia/ml. Previous studies using the same strain of M. pingshaense against late-instar larvae of C. punctiferalis reported an LC50 of 9.1 × 105 conidia/ml and MST values between 4.7 and 6.4 days1, comparable to the current findings. These results suggest that the virulence of this fungus remains consistent across different host insects. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of B. bassiana and M. anisopliae against C. infuscatellus and C. sacchariphagus indicus infesting sugarcane52 and C. partellus infesting maize53. However, our study is the first to establish the infectivity and virulence of M. pingshaense against multiple Chilo species infesting various economically important crops.

Indirect assessment of virulence of EPF is usually done by measuring the activity of key enzymes involved in infection pathways, such as chitinases, total proteases and more specific proteases like subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) enzymes54, and lipases5,22,38. These enzymes are essential for penetrating the insect cuticle, a fundamental step towards successful pathogenesis55. Preliminary screening for the production of CDEs by EPF can be conducted using plate assays on solid media containing cuticular substrates. Plate assays provide a rapid and effective method to assess the production of CDEs by the fungus, which are essential for insect infection and colonization. The presence of clear halo zones around fungal colonies indicates substrate hydrolysis by the fungus, suggesting CDE production. In our plate assays, we observed clear zones around the fungal colony within 24 h, confirming the ability of the fungus to produce key enzymes essential for insect cuticle degradation through its enzymatic arsenal56.

In our quantitative assays, we observed higher production of proteases, followed by lipases and chitinases. In general, these CDEs are critical for the pathogenicity of EPF, playing a pivotal role in the invasion process57. Among these, proteases are particularly significant during the early phase of infection, facilitating pathogen penetration through the insect cuticle37,58 followed by the activity of chitinases and lipases24,57. In our study, the total protease activity steadily increased and reached its peak activity at 5 DAI, and declined sharply over time, which is in concordance with the earlier reports5,22,24,57. Whereas, specific proteases like subtilisin-like (Pr1) and trypsin-like (Pr2) enzymes, exhibited peak activities at 3 DAI, followed by a gradual decline over time. Interestingly, the peak Pr1 enzyme activity was 2.7 times higher than that of Pr2. Similar findings have been reported in I. fumosorosea22, B. bassiana35, M. anisopliae37,59, etc. Pr1 and Pr2 are the primary enzymes produced by EPF during the early stages of infection, aiding fungal hyphae in breaching the insect cuticle5. While Pr1 is the dominant protease, Pr2 acts as its promoter during the initial stages of cuticle colonization, playing a key role in insect penetration and significantly contributing to the pathogen’s virulence60,61.

Fungal hyphae penetrate the insect cuticle with the aid of proteases, followed by the secretion of chitinases, which enhances its penetration efficiency by degrading the host’s cuticular chitin. Chitin, an important component of the insect cuticle, acts as a primary barrier against pathogen invasion18. Therefore, the secretion of chitinases by fungi not only facilitates fungal invasion but also aids in assimilating the released carbohydrate nutrients from the host, promoting fungal growth and development21,22. Chitinases are generally believed to be induced later in the infection process, following the action of proteases, due to the sequential solubilization of cuticular components55. This sequential pattern was also evident in our studies, where differences in the peak activity and production levels of chitinases were observed. Unlike proteases, which peaked in activity at 3–5 DAI in synthetic media, chitinase activity peaked at 10 DAI, with comparatively lower production levels. Similar findings have been reported in other EPFs, such as I. japonica, I. fumosorosea, A. nominus, B. bassiana, and M. anisopliae22,24,55,62,63. The lower production and delayed peak activity of chitinases can be attributed to their role in degrading pro-cuticular chitin after the outer cuticular layers have been dissolved by proteases, reflecting their secondary role in the infection process55,57.

In addition to proteases and chitinases, lipases secreted by EPF have been demonstrated to play a significant role in their entomopathogenicity against various insect pests5,22,38,64. Since lipids are an integral part of insect cuticle, the production of lipolytic enzymes by EPF is essential for its successful penetration, growth, and development23. Unlike proteases and chitinases, lipases hydrolyze the ester bonds in the waxy cuticular components of the insect integument, as well as the lipoproteins and fats within the insect body, facilitating penetration and proliferation in the host23,64. In our study, we observed lipase production in synthetic media amended with vegetable oils, olive and coconut oil respectively, with the peak activity occurring at 10 DAI, similar to the timeline observed for chitinase activity. Notably, the production of lipases was 50 times higher than that of chitinases in our experiments. Higher lipase production by the fungus signifies its virulence potential, confirming the findings of the previous studies that demonstrated the direct role of lipases in EPF virulence23,38,65. Furthermore, lipase activity is not only essential during the initial phase of host cuticle penetration by EPF, but also plays a significant role in later stages, supporting fungal growth and proliferation within the host post cuticle degradation66.

The observed increase and subsequent decline in CDEs activity of M. pingshaense in our study may be attributed to multiple interconnected factors. The initial increase in enzyme activity may be attributed to the availability of specific substrates such as chitin, proteins, or lipids in the media that induce enzyme production by the fungus. With the depletion of the available substrates and accumulation of hydrolysis products such as N-acetylglucosamine, peptides, and fatty acids in the media, the enzyme activity declines triggering a feedback inhibition. This decline also coincides with fungal developmental transition from active proliferation phase to vegetative growth and reproduction, typically associated with reduced secondary metabolism67. Additionally, culture conditions such as pH shifts and nutrient imbalances may impair enzyme stability or induce autolysis, especially proteases68.

We also investigated the production of CDEs in synthetic media supplemented with the insect cuticle of C. punctiferalis as the sole carbon source to understand the role of cuticular components in enzyme production. Interestingly, we observed significantly higher levels of total proteases, specific proteases (Pr1 and Pr2), and chitinases in the insect cuticle-amended media 5 DAI. The production levels of these enzymes were 4.6, 2.6, 2.4, and 44.5 times higher, respectively, compared to in vitro studies using specific substrates such as casein and chitin. Previous research has also reported an increased production of CDEs by EPF like I. fumosorosea, B. bassiana, and M. anisopliae, when insect cuticular components from susceptible hosts were added to the growth medium5,22,64,69,70. A plausible explanation for this observation is the immediate recognition of the insect cuticular components by the EPF64, likely due to the stimulatory effect of the cuticular substrates, resulting in rapid conidial germination and development triggering the enzyme machinery into action71. Further, it is also to be noted that the higher secretion of these enzymes in media with cuticular components indicate the synergistic interaction between these CDEs during infection, proliferation, disintegration, and nutrient assimilation by the EPF72. Interestingly, we did not observe discernible differences in lipase production between media amended with vegetable oils and insect cuticle. This may be due to the estimation of the enzyme activity at an earlier time interval in cuticle amended media in our studies. Nevertheless, it has been well-documented that lipases play a limited role during the early stages of cuticle penetration, but are crucial during the later stages of fungal development, aiding in the utilization of the insect’s lipid reserves within the hemocoel5,73. Further, earlier studies have also reported the late production of lipases in media supplemented with insect cuticular components compared to proteases and chitinases, confirming the findings of our study24,55.

We sequenced and characterized the genes encoding two key CDEs, chitinase and protease, in M. pingshaense to understand their similarity and evolutionary relationships with other EPF. Based on the amino acid sequence similarity, the chitinase gene of M. pingshaense was found to be closely related to the glycoside hydrolase family 18 protein. Previous studies have shown that the chitinase gene of M. anisopliae also shares similarity with this protein family21,74. This was also evident from the BLAST homology search, which revealed high similarity between the deduced amino acid sequence of the chitinase gene of M. pingshaense and those of M. anisopliae and other Metarhizium species. Furthermore, it suggests that chitinase genes of Metarhizium species are highly similar to the glycoside hydrolase family 18 protein. Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed these findings, revealing a close evolutionary relationship among Metarhizium species75.

The characterized subtilisin-like protease gene of M. pingshaense was found to be closely related to subtilases derived from various entomopathogenic and nematophagous fungi. These subtilases belong to two families: the subtilisin-like protease S8 and the serine-carboxyl protease S5376, and plays a significant role in disrupting the physiological integrity of insect and nematode cuticles during penetration and colonization77,78,79. At least 11 subtilisins have been identified as being secreted by the broad host range pathogen M. anisopliae during its growth on insect cuticle, as revealed by expressed tag analyses80. In our study, the subtilisin-like protease gene of M. pingshaense shared a high degree of sequence similarity with the corresponding genes from M. anisopliae and M. humberi, which was further supported by phylogenetic analysis. The strong sequence similarity between the subtilisin-like protease gene of M. pingshaense and that of the generalist pathogen M. anisopliae may explain its ability to infect hosts beyond its original host species. However, this requires detailed molecular studies to identify the array of subtilisins secreted by M. pingshaense to compare them with those of M. anisopliae and other broad host range pathogens. Such studies will provide insights into the molecular and biochemical pathways that contribute to its wide host range.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) is a powerful tool for studying the gene expression of EPF within an infected insect host. Its high sensitivity enables the detection of fungal transcripts in mixed cDNA samples containing both insect and fungal material. Additionally, the ability to analyze insect gene expression from the same sample enhances its utility in tracking the progression of infection over time81. Entomopathogenic fungi secrete chitinases and proteases to hydrolyze chitin and proteins, which are major components of the insect cuticle, thereby paving way for the successful infection of the host. Therefore, the regulation of these enzymes is considered vital for the infection of a susceptible host19. In our in vivo studies, we observed a gradual increase in the expression of these two pathogenesis-related genes, chitinase and protease, during the course of infection. The expression of these genes was initially low during the early phase (0–72 h) but increased over time, peaking at 120 hpi. These findings are consistent with our biochemical assays, which also showed a steady increase in enzyme activity over time. The high expression of the protease gene during the later phase of infection suggests that it not only facilitates fungal penetration during the initial phase but also supports conidiation upon completion of the fungal life cycle within the host82,83. Similarly, the role of the chitinase enzyme in the later phase of infection is significant, as it helps create perforations in the peritrophic membrane of the gut, allowing the pathogen to penetrate host tissues22. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that the Pr1 gene, along with the chitinase gene of entomopathogenic fungi, serves as critical markers of fungal virulence against target pests84,85,86.

Overall, our studies indicate that the enzyme production profile of M. pingshaense aligns with that of other well-studied EPF, such as B. bassiana and M. anisopliae, which also produce CDEs like chitinases, proteases, and lipases as essential virulence factors19,37,55. However, gene expression analysis during infection of C. punctiferalis revealed a unique temporal pattern in M. pingshaense, where both chitinase and protease genes showed minimal expression at 72 hpi, followed by a moderate increase at 96 hpi and a dramatic upregulation by 120 hpi. In contrast, studies on M. anisopliae and B. bassiana have demonstrated that CDE gene expression and production is often rapidly induced upon contact with insect cuticle, with their expression occurring as early as 24 h post-infection of the host55,77,87. Conversely, studies also indicate late expression of virulence genes in B. bassiana, indicating strain-specific variations in gene expression83. The delayed but intensified expression in M. pingshaense suggests a tightly regulated, host-responsive activation of virulence genes, possibly reflecting a stealth-phase strategy early in infection to evade host immunity, followed by an aggressive degradation phase for cuticle penetration and nutrient acquisition. These findings collectively highlight the adaptive infection strategy of M. pingshaense and underscore its potential as a highly effective biocontrol agent.

In conclusion, our studies highlight M. pingshaense strain IISR-EPF-14 as a potential biocontrol agent against Chilo species, which are major pests of various crops, including sugarcane, rice, maize, sorghum, etc. Additionally, the studies have elucidated the underlying virulence mechanism of this pathogen, including the production of CDEs and the upregulation of related genes during host infection. The high expression levels of these virulence genes explain the high mortality rate caused by this fungus, even against late-instar larvae of Chilo spp. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential use of this pathogen against C. punctiferalis, a polyphagous pest of various crops1. Further, the additional ecological role played by this fungus in the environment by means of organic acid production and mineral solubilization thus promoting plant growth was recently reported88. These traits, typical of a promising biocontrol agent, make M. pingshaense an ideal candidate for biopesticide development and for use in sustainable agriculture. Future studies should focus on testing the physiological host range of this organism against insects from different orders, evaluating its ecological host range under field conditions, and assessing its impact on natural enemies. Moreover, it is essential to identify other genes and toxins involved in determining the pathogen’s host range and virulence through comprehensive molecular and biochemical studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Senthil Kumar, C. M., Jacob, T. K., Devasahayam, S., Geethu, C. & Hariharan, V. Characterization and biocontrol potential of a naturally occurring isolate of Metarhizium pingshaense infecting Conogethes punctiferalis. Microbiol. Res. 243, 126645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2020.126645 (2021).

Kfir, R., Overholt, W. A., Khan, Z. R. & Polaszek, A. Biology and management of economically important lepidopteran cereal stem borers in Africa. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 701–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145254 (2002).

Harris, K. M. Keynote address: Bioecology of Chilo Species. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 11, 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742758400021044 (1990).

Yonow, T., Kriticos, D. J., Ota, N., Van Den Berg, J. & Hutchison, W. D. The potential global distribution of Chilo partellus, including consideration of irrigation and cropping patterns. J. Pest. Sci. 90, 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-016-0801-4 (2017).

Shahriari, M., Zibaee, A., Khodaparast, S. A. & Fazeli-Dinan, M. Screening and virulence of the entomopathogenic fungi associated with Chilo suppressalis walker. J. Fungi 7, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7010034 (2021).

Punithavalli, M., Jebamalaimary, A. & Salin, K. P. Defensive responses of Erianthus arundinaceus against sugarcane shoot borer, Chilo infuscatellus (Snellen) (Crambidae: Lepidoptera). Int. J. Pest Manage. 70, 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2021.1980243 (2021).

Kumar, K. K. et al. Microbial biopesticides for insect pest management in India: Current status and future prospects. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 165, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2018.10.008 (2019).

Senthil Kumar, C. M. et al. Metarhizium indicum, a new species of entomopathogenic fungus infecting leafhopper, Busoniomimus manjunathi from India. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 198, 107919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2023.107919 (2023).

de Faria, M. R. & Wraight, S. P. Mycoinsecticides and Mycoacaricides: A comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control 43, 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.08.001 (2007).

Yapa, A. T., Thambugala, K. M., Samarakoon, M. C. & de Silva, N. Metarhizium species as bioinsecticides: potential, progress, applications & future perspectives. N. Z. J. Bot. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2024.2325006 (2024).

Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 17, 553–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583150701309006 (2007).

Wang, J.B., St. Leger, R.J. & Wang, C. Advances in genomics of entomopathogenic fungi. In Advances in Genetics pp. 67–105 https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.01.002 (2016).

Boomsma, J. J., Jensen, A. B., Meyling, N. V. & Eilenberg, J. Evolutionary interaction networks of insect pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 59, 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162054 (2014).

Wang, C. & Wang, S. Insect pathogenic fungi: Genomics, molecular interactions, and genetic improvements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62, 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035509 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Horizontal gene transfer allowed the emergence of broad host range entomopathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7982–7989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816430116 (2019).

St Leger, R. J. & Wang, J. B. Metarhizium: jack of all trades, master of many. Open Biol. 10, 200307. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.200307 (2020).

Rohrlich, C. et al. Variation in physiological host range in three strains of two species of the entomopathogenic fungus. Beauveria. PLoS ONE 13, e0199199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199199 (2018).

Fan, Y. et al. Increased insect virulence in Beauveria bassiana strains overexpressing an engineered chitinase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01974-06 (2007).

Ortiz-Urquiza, A. & Keyhani, N. Action on the surface: Entomopathogenic fungi versus the insect cuticle. Insects 4, 357–374. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects4030357 (2013).

Bidochka, M. J. & Khachatourians, G. G. Growth of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana on cuticular components from the migratory grasshopper Melanoplus sanguinipes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 59, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2011(92)90028-3 (1992).

Anwar, W. et al. Chitinase genes from Metarhizium anisopliae for the control of whitefly in cotton. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 190412. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190412 (2019).

Ali, S., Huang, Z. & Ren, S. Production of cuticle degrading enzymes by Isaria fumosorosea and their evaluation as a biocontrol agent against diamondback moth. J. Pest Sci. 83, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-010-0305-6 (2010).

Ali, S., Ren, S. & Huang, Z. Extracellular lipase of an entomopathogenic fungus effecting larvae of a scale insect. J. Basic Microbiol. 54, 1148–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201300813 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Analysis of the virulence, infection process, and extracellular enzyme activities of Aspergillus nomius against the Asian corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis guenée (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Virulence 10(1080/21505594), 2265108 (2023).

Zhang, D., Qi, H. & Zhang, F. Parasitism by entomopathogenic fungi and insect host defense strategies. Microorganisms 13, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020283 (2025).

Quesada-Moraga, E., González-Mas, N., Yousef-Yousef, M., Garrido-Jurado, I. & Fernández-Bravo, M. Key role of environmental competence in successful use of entomopathogenic fungi in microbial pest control. J. Pest Sci. 97, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-023-01622-8 (2024).

Lovett, B. & St Leger, R. J. Stress is the rule rather than the exception for Metarhizium. Curr. Genet. 61(253), 261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-014-0447-9 (2015).

Siegwart, M. et al. Resistance to bio-insecticides or how to enhance their sustainability: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 381. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00381 (2015).

da Corval, A. R. C. et al. Transcriptional responses of Metarhizium pingshaense blastospores after UV-B irradiation Front. Microbiol. 15, 1507931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1507931 (2024).

Taneja, S. L. & Nwanze, K. F. Mass rearing of Chilo spp. on artificial diets and its use in resistance screening. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 11(603), 616. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742758400021172 (1990).

Xia, J.-L. et al. Production of chitinase and its optimization from a novel isolate Serratia marcescens XJ-01. Ind. J Microbiol. 51, 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-011-0139-9 (2011).

Zhang, X., Shuai, Y., Tao, H., Li, C. & He, L. Novel method for the quantitative analysis of protease activity: The casein plate method and its applications. ACS Omega 6, 3675–3680. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c05192 (2021).

Khosla, K. et al. Biodiesel production from lipid of carbon dioxide sequestrating bacterium and lipase of psychrotolerant Pseudomonas sp. ISTPL3 immobilized on biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 245, 743–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.194 (2017).

Yanai, K. et al. Purification of two chitinases from Rhizopus oligosporus and isolation and sequencing of the encoding genes. J. Bacteriol. 174, 7398–7406. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.174.22.7398-7406.1992 (1992).

Cito, A. et al. Cuticle-degrading proteases and toxins as virulence markers of Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin. J. Basic Microbiol. 56, 941–948. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201600022 (2016).

Keay, L. & Wildi, B. S. Proteases of the genus Bacillus I. Neutral proteases. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 12, 179–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260120205 (1970).

St Leger, R. J., Cooper, R. M. & Charnley, A. K. Production of cuticle-degrading enzymes by the Entomopathogen Metarhizium anisopliae during Infection of Cuticles from Calliphora vomitoria and Manduca sexta. Microbiology 133(1371), 1382. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-133-5-1371 (1987).

Supakdamrongkul, P., Bhumiratana, A. & Wiwat, C. Characterization of an extracellular lipase from the biocontrol fungus, Nomuraea rileyi MJ, and its toxicity toward Spodoptera litura. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 105, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2010.06.011 (2010).

Kumar, S. et al. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Pfaffl, M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucl. Acid. Res. 29, e45. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 (2001).

Han, S. K. et al. OASIS 2: Online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget 7, 56147–56152. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.11269 (2016).

Hajek, A. E. & Goettel, M. S. Guidelines for evaluating effects of entomopathogens on non-target organisms. In: Field Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology 816–833 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5933-9_40

Fargues, J. & Remaudiere, G. Considerations on the specificity of entomopathogenic fungi. Mycopathologia 62, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00491993 (1977).

Kirubakaran, S. A., Abdel-Megeed, A. & Senthil-Nathan, S. Virulence of selected indigenous Metarhizium pingshaense (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) isolates against the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Guenèe) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 101, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2017.06.004 (2018).

Fu, N. et al. Identification and biocontrol potential evaluation of a naturally occurring Metarhizium pingshaense isolate infecting tea weevil Myllocerinus aurolineatus Voss (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Egypt J. Biol. Pest Control. 33, 101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00749-1 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Isolation of a highly virulent Metarhizium strain targeting the tea pest Ectropis obliqua. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1164511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1164511 (2023).

Peña-Peña, A. J., Santillán-Galicia, M. T., Hernández-López, J. & Guzmán-Franco, A. W. Metarhizium pingshaense applied as a seed treatment induces fungal infection in larvae of the white grub Anomala cincta. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 130, 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2015.06.010 (2015).

Cito, A. et al. Characterization and comparison of Metarhizium strains isolated from Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 355, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6968.12470 (2014).

Francis, J. R. Biocontrol potential and genetic diversity of Metarhizium anisopliae lineage in agricultural habitats. J. Appl. Microbiol. 127, 556–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14328 (2019).

Lovett, B. et al. Transgenic Metarhizium rapidly kills mosquitoes in a malaria-endemic region of Burkina Faso. Science 364, 894–897. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw8737 (2019).

Butt, T. M. & Goettel, M. S. Bioassays of entomogenous fungi. In Bioassays of Entomopathogenic Microbes and Nematodes 141–195 (CABI Publishing, UK, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851994222.0141

Goble, T., Almeida, J. & Conlong, D. Microbial Control of Sugarcane Insect Pests. In: Microbial Control of Insect and Mite Pests. 299–312 (Elsevier, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803527-6.00020-2

Tefera, T. & Pringle, K. L. Evaluation of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae for controlling Chilo partellus (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in maize. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 14, 849–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958315041000172707 (2004).

Mascarin, G. M., Kobori, N. N., Quintela, E. D. & Delalibera, I. The virulence of entomopathogenic fungi against Bemisia tabaci biotype B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and their conidial production using solid substrate fermentation. Biol. Control 66, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.05.001 (2013).

St Leger, R. J., Charnley, A. K. & Cooper, R. M. Cuticle-degrading enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi: Synthesis in culture on cuticle. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 48(85), 95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2011(86)90146-1 (1986).

Gebremariam, A., Chekol, Y. & Assefa, F. Extracellular enzyme activity of entomopathogenic fungi, Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae and their pathogenicity potential as a bio-control agent against whitefly pests, Bemisia tabaci and Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). BMC Res. Notes 15, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-022-06004-4 (2022).

Kang, S. C., Park, S. & Lee, D. G. Purification and characterization of a novel chitinase from the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 73, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1006/jipa.1999.4843 (1999).

Charnley, A. K. Fungal pathogens of insects: Cuticle degrading enzymes and toxins. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 47, 241–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2296(05)40006-3 (2003).

St Leger, R. J., Charnley, A. K. & Cooper, R. M. Characterization of cuticle-degrading proteases produced by the entomopathogen Metarhizium anisopliae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 253(221), 232. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(87)90655-2 (1987).

St Leger, R. J., Joshi, L., Bidochka, M. J., Rizzo, N. W. & Roberts, D. W. Biochemical characterization and ultrastructural localization of two extracellular trypsins produced by Metarhizium anisopliae in infected insect cuticles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62(1257), 1264. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.62.4.1257-1264.1996 (1996).

Gillespie, J. P., Bateman, R. & Charnley, A. K. Role of cuticle-degrading proteases in the virulence of Metarhizium spp. for the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 71(128), 137. https://doi.org/10.1006/jipa.1997.4733 (1998).

Kawachi, I. et al. Purification and properties of extracellular chitinases from the parasitic fungus Isaria japonica. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 92, 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80313-3 (2001).

Fang, W. et al. Cloning of Beauveria bassiana chitinase gene Bbchit1 and its application to improve fungal strain virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.1.363-370.2005 (2005).

da BeysSilva, W. O. et al. The entomopathogen Metarhizium anisopliae can modulate the secretion of lipolytic enzymes in response to different substrates including components of arthropod cuticle. Fungal. Biol. 114(911), 916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2010.08.007 (2010).

da BeysSilva, W. O., Santi, L., Schrank, A. & Vainstein, M. H. Metarhizium anisopliae lipolytic activity plays a pivotal role in Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus infection. Fungal Biol. 114(10), 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycres.2009.08.003 (2010).

Vidhate, R. P., Dawkar, V. V., Punekar, S. A. & Giri, A. P. Genomic determinants of entomopathogenic fungi and their involvement in pathogenesis. Microb. Ecol. 85, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-021-01936-z (2023).

Demain, A. L. Regulation of secondary metabolism in fungi. Pure Appl. Chem. 58, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198658020219 (1986).

Lopez-Llorca, L. V., Carbonell, T. & Gomez-Vidal, S. Degradation of insect cuticle by Paecilomyces farinosus proteases. Mycol. Prog. 1, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-006-0022-y (2002).

St Leger, R. J., Staples, R. C. & Roberts, D. W. Changes in translatable mRNA species associated with nutrient deprivation and protease synthesis in Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137(807), 815. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-137-4-807 (1991).

Qazi, S. S. & Khachatourians, G. G. Hydrated conidia of Metarhizium anisopliae release a family of metalloproteases. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 95, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2006.12.002 (2007).

Ment, D. et al. Metarhizium anisopliae conidial responses to lipids from tick cuticle and tick mammalian host surface. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.12.010 (2010).

St Leger, R. J., Cooper, R. M. & Charnley, A. K. Analysis of aminopeptidase and dipeptidylpeptidase IV from the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139(237), 243. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-139-2-237 (1993).

Hegedus, D. D. & Khachatourians, G. G. Production of an extracellular lipase by Beauveria bassiana. Biotechnol. Lett. 10, 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01024716 (1988).

da Silva, M. V. et al. Cuticle-induced endo/exoacting chitinase CHIT30 from Metarhizium anisopliae is encoded by an ortholog of the chi3 gene. Res. Microbiol. 156, 382–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2004.10.013 (2005).

Wattanalai, R., Boucias, D. G., Tartar, A. & Wiwat, C. Chitinase gene of the dimorphic mycopathogen Nomuraea rileyi. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 85, 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2003.12.007 (2004).

Li, J., Gu, F., Wu, R., Yang, J. & Zhang, K.-Q. Phylogenomic evolutionary surveys of subtilase superfamily genes in fungi. Sci. Rep. 7, 45456. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45456 (2017).

Gao, Q. et al. Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics of the model entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and M. acridum. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001264 (2011).

Wang, B., Liu, X., Wu, W., Liu, X. & Li, S. Purification, characterization, and gene cloning of an alkaline serine protease from a highly virulent strain of the nematode-endoparasitic fungus Hirsutella rhossiliensis. Microbiol. Res. 164, 665–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2009.01.003 (2009).

Lai, Y. et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics analyses reveal divergent lifestyle features of nematode endoparasitic fungus Hirsutella minnesotensis. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 3077–3093. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evu241 (2014).

Bagga, S., Hu, G., Screen, S. E. & StLeger, R. J. Reconstructing the diversification of subtilisins in the pathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Gene 324(159), 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.031 (2004).

Lobo, L. S. et al. Assessing gene expression during pathogenesis: Use of qRT-PCR to follow toxin production in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana during infection and immune response of the insect host Triatoma infestans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 128, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2015.04.004 (2015).

Small, C.-L.N. & Bidochka, M. J. Up-regulation of Pr1, a subtilisin-like protease, during conidiation in the insect pathogen Metarhizium anisopliae. Mycol. Res. 109, 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953756204001856 (2005).

Galidevara, S., Reineke, A. & Koduru, U. D. In vivo expression of genes in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana during infection of lepidopteran larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 136, 32–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2016.03.002 (2016).

Gao, B.-J. et al. Subtilisin-like Pr1 proteases marking the evolution of pathogenicity in a wide-spectrum insect-pathogenic fungus. Virulence 11, 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2020.1749487 (2020).

Fang, W. et al. Expressing a fusion protein with protease and chitinase activities increases the virulence of the insect pathogen Beauveria bassiana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 102, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.013 (2009).

Wang, Z. et al. Molecular cloning of a novel subtilisin-like protease (Pr1A) gene from the biocontrol fungus Isaria farinosa. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 48, 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13355-013-0208-0 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. In vitro transcriptomes analysis identifies some special genes involved in pathogenicity difference of the Beauveria bassiana against different insect hosts. Microb. Pathog. 154, 104824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104824 (2021).

Senthil Kumar, C. M. et al. Zinc solubilization and organic acid production by the entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium pingshaense sheds light on its key ecological role in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 923, 171348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171348 (2024).

Acknowledgements

CMSK acknowledges the funding support by Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment (KSCSTE) project, Development of a Metarhizium sp. based bio-pesticide formulation for the control of shoot borer, Conogethes punctiferalis infesting cardamom, ginger and turmeric (No. 466/2020/KSCSTE dated 23.06.2020) under the"Young Investigators Programme in Biotechnology"of Kerala Biotechnology Commission. The authors thank the Director, ICAR-IISR, Kozhikode, for necessary facilities. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped to improve the manuscript.

Funding

Kerala Biotechnology Commission,No. 466/2020/KSCSTE dated 23.06.2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMSK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review & editing, Validation. MS: Investigation, Data curation. MBR: Investigation; MP: Investigation. SDS: Investigation. CG: Investigation. PA: Investigation. TKJ: Writing—original draft, Validation. SD: Editing, Validation, Supervision. AIB: Validation, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Senthil Kumar, C.M., Samyuktha, M., Rajkumar, M.B. et al. Host range and virulence of Metarhizium pingshaense against Chilo species and expression of fungal virulence genes in Conogethes punctiferalis. Sci Rep 15, 18506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03643-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03643-y