Abstract

Deep well drilling in high-salinity geological formations presents significant challenges, including recurrent loss of drilling fluids and repeated plugging failures. These issues necessitate a reevaluation of conventional lost circulation materials (LCMs) and their performance metrics. Here, we investigate the behavior of commonly used bridging LCMs under high-salinity conditions characteristic of the Kuqa foreland in China’s Tarim Basin. Our comprehensive experimental study reveals that high-salinity environments substantially impact the stability of LCM formed plugging zones. We demonstrate that after exposure to formation water with 200,000 mg/L salinity at 150 °C for 24 h, millimeter-sized calcium carbonate LCMs exhibit significant physical and mechanical changes. These include color darkening, 4.79% mass loss, and a 13.75% reduction in friction coefficient. The compressive strength degradation rates at D90 for pre- and post-high-salinity treatment were 17.58% and 5.48%, respectively. Walnut shell LCMs showed more pronounced alterations, with color change from dark brown to black, 32.51% mass loss, and a 28.57% decrease in friction coefficient. Their compressive strength degradation rates at D90 were 3.53% and 28.76% for pre- and post treatment, respectively. Synthetic polymer LCMs, while maintaining color stability, experienced a 9.51% mass loss and a 20.86% reduction in friction coefficient, with compressive strength degradation rates of 2.40% and 22.96% for pre- and post-treatment, respectively. Our findings indicate that the frictional performance and compressive strength of LCMs are compromised in deep, high-salinity geological formations. This deterioration leads to shearing instability and particle size degradation, ultimately resulting in plug failure. This study provides crucial insights for the selection of LCMs capable of maintaining long-term pressure stability in challenging deep, high-salinity formations, potentially revolutionizing drilling practices in such environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-salinity geological formations, such as salt layers, hypersaline lacustrine oil reservoirs, massive salt strata, and deep high-salinity aquifer gas reservoirs, are widely distributed across the globe1,2,3,4. These formations, which have developed during various geological periods, can be found in sedimentary basins on every continent. Notable examples include the Honigsee salt cavern gas storage facility in Germany, the Eminence salt cavern gas storage facility in the United States, the extensive salt strata of the Tarim Basin in China, and the hypersaline lacustrine oil reservoirs in the Qaidam Basin5,6. These high-salinity geological formations play a critical role in both gas storage and the enhancement of oil and gas reserves. In the context of gas storage, salt cavern storage facilities are particularly suitable for storing gases such as natural gas due to their excellent sealing properties and stability. As for hydrocarbon resources, salt strata serve as effective cap rocks for oil and gas reservoirs, potentially trapping significant quantities of hydrocarbons beneath them. For instance, the Kuqa Depression in the Tarim Basin, China’s largest and most prolific deep hydrocarbon basin, is the primary natural gas production area, with geological reserves surpassing one trillion cubic meters. The thickness of the salt strata in this region ranges from nearly 4000 m to over 100 m7,8,9,10. Additionally, hypersaline lacustrine oil reservoirs and deep high-salinity hydrocarbon reservoirs comprise unique depositional environments rich in oil and gas resources. Such formations are key exploration targets for oil companies, exemplified by the high-salinity hydrocarbon reservoirs in the Tarim Basin and the hypersaline lacustrine oil reservoirs in the Qaidam Basin11,12,13,14,15,16.

Drilling engineering in high-salinity geological formations faces stringent geological conditions and numerous technical bottlenecks. Notably, wellbore lost circulation is one of the most common and challenging drilling complications to17,18,19,20,21. Wellbore lost circulation, defined as the substantial loss of drilling fluid into the surrounding formation, not only results in significant consumption of drilling fluid and Prolonged drilling times but also poses risks such as well collapse, blowouts, stuck pipe events, and even the catastrophic failure of the wellbore, leading to considerable engineering disasters. At present, the global drilling leakage rate accounts for about 20–25% of the total number of drillings, and the annual cost of plugging leakage is as high as $4 billion22. Accounts indicate that wellbore lost circulation constitutes approximately 70% of the total operational downtime attributed to drilling complications, incurring direct annual losses exceeding 10 billion CNY in China, with immeasurable indirect losses 37. It is a critical bottleneck impairing the efficiency and effectiveness of deep geological resource extraction Management23,24,25,26,27,28. The physical method of lost circulation prevention and plugging is currently the most widely employed technique in drilling engineering7,29. This method offers numerous advantages, including a wide range of available LCMs, simplicity of procedure, and manageable construction safety risks. It involves adding physical LCMs (such as particulate or fibrous materials) to the drilling fluid, which then forms a high-pressure barrier within the formation’s pores and fractures, temporarily or permanently isolating the wellbore from the formation to prevent drilling fluid loss manage28,30,31. Extensive research has been conducted on the optimization and selection of LCMs, which vary significantly in function and performance. Notably:

-

(1)

Geometric parameter optimization: The main concern is the spatial compatibility between lcm and fracture system. (Key parameters: particle size distribution (D50, D90), aspect ratio, sphericity.) Alsaba et al.28 and Razavi et al.32 proposed matching the particle size of LCMs with fracture dimensions experimentally, establishing the Mortadha and Omid bimodal selection criteria. Lei et al. investigated the principles of optimal material selection based on the formation mechanism of the plugging layer30. (Limitations: Static particle size matching ignores downhole dynamic conditions that lead to particle rearrangement and particle size degradation).

-

(2)

Mechanical parameter optimization: It mainly solves the mechanical stability problem of the plugging layer under the action of underground stress. (Key Characteristics: Compressive strength (> fracture closure stress), Friction coefficient, Elastic modulus).Beardmore et al.33 highlighted that particle size degradation occurs with particulate LCMs during circulation.

-

(3)

Chemical parameter optimization: Kang et al.34 underscored that high-salt treatment failure is a significant factor in the structural breakdown of plugging layers in deep wells. These insights contribute to refining the selection and application of LCMs in drilling operations, aiming to mitigate wellbore lost circulation and enhance the overall efficacy of deep geological resource exploration. Current restrictions: Most studies use short-term (< 2 h) compression tests and ignore the creep behavior over time. Limited data on friction coefficient degradation at high temperatures (> 120 °C).There is no established cyclic stress resistance test standard.

Drilling operations in high-salinity geological formations frequently encounter recurrent fluid losses, indicating that conventional metrics for evaluating LCMs—such as particle size distribution, geometric shape, and thermal resistance—are inadequate to meet the demands of drilling fluid loss control. The pressure stability of LCMs under conditions of high temperature, high in-situ stress, and high salinity has emerged as a key technical challenge in managing fluid losses within these formations34. Sider, for example, a block in the Kuqa Depression of the Tarim Basin, where the reservoir is at a depth of 7700 m, with a temperature of 168 °C and an average formation water salinity of 210,000 mg/L. During drilling operations in this block, multiple instances of drilling fluid loss occurred, ranging from 24.5 to 573.0 m3, with an average loss volume of 164.7 cubic meters. A single application of while-drilling plug setting initially mitigated fluid loss, but recurrent losses subsequently ensued, requiring 18 instances of while-drilling plug setting and three dedicated plug-setting operations, none of which effectively controlled the losses. Insufficient pressure capacity following plug-setting operations led to repeated fluid losses during subsequent activities, significantly hampering hydrocarbon extraction progress.

While prior studies (e.g., Alsaba et al.,28; Razavi et al.,32) established particle size optimization criteria for LCMs and Kang et al.34 addressed high-temperature aging, the combined effects of high salinity (200,000 mg/L), temperature (150 °C), and pressure on LCM stability remain poorly understood. This study bridges this gap by systematically evaluating LCM performance under conditions mirroring the extreme salinity of the Tarim Basin’s Kuqa Depression—a critical advancement for regions where recurrent losses persist despite conventional LCM use.

Unlike traditional evaluations focused on standalone metrics like particle size or thermal stability, this work introduces a holistic assessment of LCMs under high salinity, integrating mass loss, friction coefficient degradation, compressive strength changes, and microstructural analysis via SEM. This approach reveals previously undocumented interactions, such as salt precipitation enhancing calcium carbonate’s compressive strength (17.58% vs. 5.48% degradation pre-/post-salinity treatment) and walnut shell’s structural collapse due to dissolution pores (32.51% mass loss).

By employing SEM, this study uncovers micro-scale mechanisms driving LCM failure in saline environments. For instance, walnut shells develop honeycomb-like dissolution pores under salinity, directly linking structural degradation to friction coefficient reduction (28.57%). Such granular insights are absent in prior literature, which often relies on macroscopic performance metrics.

The findings challenge industry reliance on organic materials like walnut shells in high-salinity formations, demonstrating their unsuitability due to chemical instability. Conversely, synthetic polymers, despite minimal visual changes, exhibit significant friction degradation (20.86%), necessitating a paradigm shift toward inorganic or composite materials. These results provide a science-backed framework for optimizing LCM formulations in saline reservoirs, addressing a critical field challenge highlighted by repeated losses in the Kuqa Depression.

The development of a custom friction coefficient apparatus (COF-1) and compressive strength tester tailored for high-salinity conditions represents a methodological leap, enabling precise simulation of downhole shear and pressure dynamics. This contrasts with conventional lab setups that overlook salinity’s role in material degradation.

Materials and methods

Experimental sample

Bridging LCMs, filling materials, and deformable fibers collectively constitute the fracture plugging zone, with bridging LCMs forming the structural framework and occupying the largest volume fraction. In this study, we selected three commonly used bridging LCMs for high-salinity reservoir drilling in the Kuqa Depression of the Tarim Basin: millimeter-scale calcium carbonate (Fig. 1a), walnut shells (Fig. 1b), and polymer materials (Fig. 1c). These materials respectively represent three characteristic categories of bridging LCMs: inorganic mineral materials, plant-derived organic materials, and synthetic polymer materials.

For the experimental fluid, we prepared simulated formation water in the laboratory, matching the salinity data of deep well drilling fluids from a block in the Tarim Basin (Table 1). This setup ensured that the test conditions accurately reflected the high salinity conditions encountered in the field.

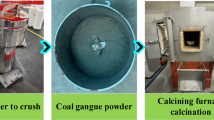

High-salinity treatment experiment for LCMs

The experimental procedure for high-salinity treatment of lost circulation materials (LCMs) is as follows: (1) Weigh 30.00 g of walnut shell LCMs using an analytical balance, and place it into an aging cell; (2) Pour the pre-prepared simulated formation water into the aging cell containing the LCMs, ensuring that the liquid completely submerges the material and isolates it from atmospheric oxygen. Place the aging cell into a roller oven set at 150 °C. After 24 h, retrieve the aging cell; (3). After allowing the aging cell to cool, remove the LCMs, rinse and dry it thoroughly at 80 ℃. Utilizing a Quanta 450 environmental scanning electron microscope, scan and analyze the microstructural changes of the LCMs before and after high-salinity treatment; (4) Take the same mass of millimeter calcium carbonate and polymer material and repeat steps 2–3.

Performance parameter testing of LCMs before and after high-salinity treatment

Mass loss rate

To assess the mass loss rate of the lost circulation materials (LCMs) subjected to high-salinity conditions, we measured the mass of the LCMs both prior to and following the salinity treatment. The mass loss rate was calculated using the following equation (Eq. 1):

where (M0) represents the initial mass of the LCMs in grams (g), and (Mt) denotes the post-treatment mass of the LCMs in grams (g).

Coefficient of friction testing

The coefficient of friction (COF) for three types of lost circulation materials (LCMs) was measured before and after high-salinity treatment using a custom-developed COF-1 friction measurement apparatus. The operational principle of the COF-1 apparatus is depicted in Fig. 2. The experimental procedure is outlined as follows: (1) Preparation of Friction Plates: The granular LCMs were first dried at 60 °C in an oven. One side of a steel plate was coated with an adhesive, and the dried granular LCMs were uniformly applied in a single layer. The adhesive-coated steel plate was then lightly pressed against a clean glass plate to ensure a flat surface, forming the granular LCMs friction plates. Two sizes of granular LCMs friction plates were prepared: lower plates measuring 5 cm by 3 cm and upper plates measuring 2 cm by 3 cm; (2) Assembly for Testing: The lower granular LCMs friction plate (Fig. 3a) was mounted on a stand with the LCMs-coated side facing upward. The pre-weighed upper granular LCMs friction plate (Figs. 3b, 4a–c) was placed horizontally at the left end of the lower plate; (3) Load Application: A weighted mass was gently placed at the center of the upper surface of the lower friction plate and secured. A fine steel wire was used to connect the slide to a spring, ensuring the wire remained slack; (4) Liquid Immersion: Lubricating fluid was slowly added to a temperature-controlled liquid bath until the liquid level submerged the contact interface; (5) COF Measurement: The COF measurement apparatus was activated to record the friction force versus displacement curves; (6) Calculation of Friction Coefficient: Using Eq. (2), the coefficient of friction was calculated, and the variations in the COF of the granular LCMs were plotted.

Schematic diagram of friction coefficient measuring system (COF-1)8.

Friction plate of particle plugging material: (a) friction plate of lower particle plugging material, (b) friction plate of upper particle plugging material8.

In Eq. (2), µs represents the surface friction coefficient between the granular LCMs (dimensionless); Ff is the friction force recorded by the force sensor (N); and (m) denotes the total mass and weight of the upper friction plate (kg).

Compressive strength testing

Using a self-developed drilling plugging rigid material compressive strength tester, we conducted compressive strength tests on the plugging materials before and after high-salinity treatment. The degradation rate of particle size distribution D90 was chosen as the evaluation metric for compressive strength. A schematic of the testing apparatus is depicted in Fig. 5. The compressive strength of the granular materials was evaluated through the following experimental steps: (1) Initial Particle Size Distribution Measurement: Measure the initial particle size distribution of the granular LCMs to determine the initial D90 value ((D90i)); (2) Sample Preparation: Spread a single layer of the granular LCMs onto the lower steel plate B, and place steel plate A on top of the granular LCMs; (3) Application of Pressure: Activate the hydraulic press to apply a constant vertical pressure of 30.0 MPa on steel plate A. Maintain this pressure for 30 min before shutting down the hydraulic press; (4) Material Recovery: Recover the granular LCMs, ensuring a mass recovery rate of at least 95%; (5) Post-Compression Particle Size Distribution Measurement: Measure the particle size distribution of the compressed granular LCMs to determine the post-compression D90 value ((D90_c)); 6) Calculation of D90 Degradation Ratio: Utilize Eqs. (5) and (6) to calculate the D90 degradation ratio (DDR) of the compressed granular LCMs.

Schematic diagram of pressure device of LCMs8.

Mechanical factors impacting shear instability

Shear instability in fracture plugging zones arises from the interplay of stress distribution, particle interactions, and boundary conditions. Key mechanical factors include:

Stress heterogeneity

Local stress concentration

Fracture surfaces exhibit natural roughness, leading to uneven stress distribution. Regions with higher asperity contact experience elevated shear stress, initiating localized failure.

Force chain dynamics

Granular LCMs form force chains that transmit stresses through the plugging zone. Weak or discontinuous force chains (e.g., due to particle degradation) reduce load-bearing capacity, accelerating shear failure35.

Particle morphology and friction

Shape and roughness

Angular particles (e.g., walnut shells) enhance interlocking and friction, whereas spherical particles (e.g., polymer beads) exhibit lower shear resistance.

Friction coefficient reduction

High-salinity aging reduces surface roughness (Section "Mechanism of the impact of high-salinity treatment on the friction performance of LCMs"), diminishing inter-particle friction and destabilizing force chains.

Confinement pressure

Lateral Constraint: In situ stresses provide lateral confinement that stabilizes the plugging zone. However, in deep formations (> 7000 m), elevated deviatoric stresses may exceed the critical shear strength of LCM assemblies.

Particle size degradation

Fragmentation under load

Compressive failure of LCMs (Section "Impact of high-salinity treatment on the compressive strength of LCMs") generates fines that fill voids, initially improving packing density. However, excessive degradation reduces particle interlock and weakens the force chain network.

Key assumptions in the analysis

Our analysis relies on the following assumptions, justified by experimental and field conditions:

Quasi-static loading

Assumption

Stress redistribution within the plugging zone occurs slowly relative to particle rearrangement timescales.

Justification

Drilling fluid pressure changes gradually during circulation, validating a quasi-static approach.

Homogeneous fluid pressure

Assumption

Fluid pressure acts uniformly across the plugging zone.

Justification

High-permeability fractures (width > 1 mm) in salt formations allow rapid pressure equilibration, as observed in field data from the Kuqa Depression.

Rigid particle behavior

Assumption

LCMs undergo negligible elastic deformation under stress.

Justification

Calcium carbonate and walnut shells have Young’s moduli > 10 GPa, making elastic strains (< 0.1%) negligible compared to fracture displacements (> 1 mm).

Isothermal conditions

Assumption

Temperature effects on mechanical properties (e.g., polymer viscoelasticity) are secondary to salinity effects.

Justification

Prior studies show that salinity-induced degradation dominates over thermal effects for the tested LCMs at 150 °C (Qiu et al., 2006; Kang et al.34).

The selection of specific parameters for evaluating the performance of lost circulation materials (LCMs) under high-salinity conditions was guided by the need to comprehensively assess the materials’ stability, mechanical integrity, and functional efficacy in deep, high-salinity geological formations. The following parameters were chosen based on their direct relevance to the operational challenges encountered in such environments:

Mass loss rate

Mass loss is a critical indicator of the chemical and physical stability of LCMs when exposed to high-salinity environments. In deep geological formations, LCMs are subjected to harsh conditions, including high temperatures and saline fluids, which can lead to chemical reactions, dissolution, or degradation of the materials. By measuring the mass loss rate, we can quantify the extent to which the materials are affected by these conditions. A high mass loss rate suggests that the material is susceptible to degradation, which could compromise the integrity of the plugging zone and lead to recurrent fluid losses. This parameter is particularly important for organic materials, such as walnut shells, which are prone to chemical reactions in saline environments.

Friction coefficient

The friction coefficient between LCMs and the fracture surfaces is a key factor influencing the stability of the plugging zone. In high-salinity environments, the friction properties of LCMs can be altered due to changes in surface morphology, chemical interactions, or the formation of salt precipitates. A reduction in the friction coefficient can lead to shear instability within the plugging zone, making it more susceptible to failure under pressure differentials. By measuring the friction coefficient before and after high-salinity treatment, we can evaluate how the materials’ frictional performance is affected, which is crucial for ensuring the long-term stability of the plugging zone in deep, high-salinity formations.

Particle size degradation (D90 compressive strength)

Particle size degradation, particularly the D90 compressive strength, is a critical parameter for assessing the mechanical integrity of LCMs under high-stress conditions. In deep geological formations, LCMs are subjected to significant fracture closure stresses, which can cause particle breakdown or size reduction. If the particles degrade too much, the plugging zone may lose its structural integrity, leading to failure. By measuring the D90 degradation rate, we can evaluate the compressive strength of the materials and their ability to withstand the high pressures encountered in deep wells. This parameter is especially important for inorganic materials like calcium carbonate, which are expected to maintain their structural integrity under high-stress conditions.

By focusing on these key parameters, this study aims to address the limitations of conventional LCM evaluation metrics, such as particle size distribution and thermal stability, which do not fully capture the challenges posed by high-salinity environments. The results of this research will provide valuable insights for optimizing LCM selection and improving the effectiveness of lost circulation control in deep, high-salinity geological formations.

Experimental results and discussion

Response characteristics of the mass loss of LCMs under high-salinity treatment

As shown in Fig. 6a–c, millimeter-sized calcium carbonate particles are bright white overall, walnut shells are dark brown, and synthetic polymer LCMs are black. After high-salinity treatment, the color of the millimeter-sized calcium carbonate darkened, the walnut shells changed from yellow to black, and the color transformation ranged from bright to dark with the production of black debris. The synthetic polymer LCMs showed no significant change in color (Fig. 6d–f). Figure 7 illustrates the changes in the mass of LCMs before and after the experiment. For walnut shells, their weight was 30.00 g before the experiment. After aging at simulated formation temperature for 24 h, their weight decreased to 25.95 g, with a mass loss rate of 13.51%. When considering the influence of the high-salinity formation environment, the mass loss rate further increased to 32.51%. For mineral-based LCMs such as calcium carbonate, the impact of salinity on mass loss rates was relatively lower, with a mass loss rate of 4.79% in high-salinity aging conditions. High-salinity aging affected the mass loss rate of organic polymeric LCMs to 9.51%. The experimental results indicate that various LCMs respond differently to high-salinity environments. Millimeter-sized calcium carbonate particles, walnut shells, and rubber granule materials exhibit differing changes in both color and mass. This suggests varied sensitivity of the saline-induced degradation and physical structure of different materials to salinity. The significant mass and color of walnut shells indicate that they are more prone to degradation or reaction in saline environments. This is attributed to the organic components in walnut shells, which are more susceptible to chemical reactions in the presence of salinity. In contrast, the relatively low mass loss rate of millimeter-sized calcium carbonate particles demonstrates better stability in saline environments. This is because calcium carbonate, given its mineral nature, is chemically more stable and less reactive with salinity. The pH of formation water is about 6.16, which is weakly acidic.

Morphology of Lost Circulation Materials (LCMs) before and after High-Salinity Treatment. (a) Inorganic rigid LCMs before treatment; (b) Organic rigid LCMs before treatment; (c) Synthetic polymer LCMs before treatment; (d) Inorganic rigid LCMs after treatment; (e) Organic rigid LCMs after treatment; (f) Synthetic polymer LCMs after treatment.

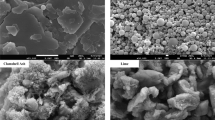

Microstructural response of LCMs to high-salinity treatment

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was conducted to observe the microstructural changes in lost circulation materials (LCMs) before and after high-salinity treatment. The SEM analysis revealed that millimeter-sized calcium carbonate particles exhibited a rough surface structure with uneven distribution and small micro cracks (Fig. 8a) as well as micron-sized debris particles (Fig. 8b). Since the calcium carbonate particles used in the experiment were derived from natural calcite minerals, calcite crystals typically demonstrate good cleavage. In the crystal structure of calcite, carbonate ions and calcium ions are connected by ionic bonds, forming a layered structure. The weaker intermolecular forces within the crystals make these layers prone to glide along specific crystal planes, resulting in cleavage. After high salt treatment, the surface of millimeter-sized calcium carbonate particles is covered by precipitated salt-assisted substances, partially repairing the surface defects. Walnut shell LCMs exhibited a relatively rough, multi-layered flaky structure on their surface (Fig. 9a,b). Following high-salinity treatment, numerous dissolution pores approximately 20 μm in diameter appeared on the walnut shell surfaces. These pores were spaced far apart, reducing the structural compactness and giving the overall structure a honeycomb-like appearance. The surface of the synthetic polymer LCMs was relatively smooth and dense (Fig. 10a,b). No significant microstructural changes were observed before and after high-salinity treatment, indicating that this material may possess good resistance to high-salinity conditions.

Mechanism of the impact of high-salinity treatment on the friction performance of LCMs

Figure 11 shows the change curves of the friction coefficients of three LCMs before and after High-Salinity Treatment. Overall, the friction coefficient curves of the LCMs exhibit a significant stick–slip characteristic, with the peak representing the maximum static friction coefficient. This peak divides the curve into two stages: static friction and sliding friction. The static friction stage reflects the transition of the fracture plugging zone from a stable state to an unstable state, while the sliding stage indicates the destabilization process of particle-type LCMs within the fracture. Figure 12 displays the changes in the average friction coefficients of the three types of LCMs. The average friction coefficient of walnut shells decreased from 0.7 before aging to 0.5 after aging, representing a reduction of 28.57%. The friction coefficient of millimeter-sized calcium carbonate decreased from 0.8 before aging to 0.69 after aging, amounting to a reduction of 13.75%. The friction coefficient of organic polymer materials decreased from 1.39 before aging to 1.10 after aging, reflecting a decline of 20.86%. Overall, the friction coefficients for organic polymers and organic plant-based LCMs exhibited significant decreases after high-salinity treatment.

The friction coefficient between LCMs is a critical parameter influencing the pressure-bearing capacity of the plugging zone. The shear strength of the fracture plugging zone itself is the main factor determining its stability under the pressure difference between the borehole and the fracture. Due to the uneven development of micro asperities on the fracture surface, the friction force between the fracture plugging zone and the fracture surface is not uniform, making regions with lower friction forces more prone to failure. Moreover, since the formation of the fracture plugging zone is a random process, the plugging zone structure exhibits some heterogeneity, with inherent structural weak points. During pressure-bearing, instability will first occur at these weak points. Local shear instability of the fracture plugging zone is the primary form of structural failure (Fig. 13a). Shear instability of the fracture plugging zone refers to the mode of structural failure occurring first at a weak point or weak area of the plugging zone under the differential pressure between the borehole fluid column and the fracture (Fig. 13b). When the friction coefficient of the LCMs is relatively low, the force chain network in the plugging zone is easily disrupted under minimal shear stress. To enhance the efficiency of loss control in saline formations, the impact of the salt resistance of LCMs on their friction performance should be considered when selecting formulations.

Shear instability mode of the fracture plugging zone36.

Impact of high-salinity treatment on the compressive strength of LCMs

The particle size of millimeter-grade organic LCMs is concentrated between 1700 and 4750 μm, with a D90 particle size distribution of 4451 μm (Fig. 14). The particle size distribution of inorganic material is concentrated between 550 and 1660 μm, with a D90 of 1470 μm (Fig. 15). The synthetic polymer material LCMs has a particle size distribution ranging between 2187 and 4365 μm, with a D90 of 4265 μm (Fig. 16). As shown in Fig. 15a, the particle size distribution curve of the organic LCMs slightly shifts to the left after being subjected to a fracture closure pressure of 30.0 MPa for 30 min. After high-salinity treatment and subsequent pressurization, the leftward shift of the particle size distribution curve becomes more pronounced, with a D90 degradation rate of 3.53% and 28.76% before and after high-salinity treatment, respectively (Fig. 15b). The particle size distribution curve of the inorganic LCMs shifts leftward under pressure, with an increased proportion of particles between 700 and 1000 μm, indicating that some initial millimeter-grade particles degrade to several hundred micrometers under fracture closure pressure. The D90 decreases from 1470 to 1212 μm, a reduction of 17.58% (Fig. 14a). After high-salinity treatment and subsequent compressive strength testing, the D90 degradation rate of the inorganic bridging material calcium carbonate is observed to decrease to 5.48% compared to untreated material, suggesting that high-salinity treatment enhances the compressive strength of inorganic rigid plugging materials, likely due to the encapsulation effect of precipitated salts on the inorganic surfaces (Fig. 14b). The synthetic polymer LCMs has high compressive strength with a D90 degradation rate of only 2.40% (Fig. 16a). However, the D90 degradation rate increases to 22.96% after high-salinity treatment (Fig. 16b). Overall, the compressive strength ranking of rigid plugging materials before and after high-salinity treatment is as follows: millimeter-grade calcium carbonate LCMs > synthetic polymer LCMs > walnut shell LCMs. Overall, the compressive strength ranking of rigid plugging materials before and after high-salinity treatment is as follows: millimeter-grade calcium carbonate LCMs > synthetic polymer LCMs > walnut shell LCMs (Table 2).

Schematic illustration of sealing failure due to compressive failure of the plugging zone. (a) Before failure; (b) After failure36.

For deep fractured rock masses, high fracture closure stress is a defining characteristic. The conditions of high fracture closure stress in the formation demand superior compressive strength from bridging materials (Fig. 17a). Should the compressive strength of these materials fall below the fracture closure stress, particle degradation of the bridging material may occur, leading to instability in the fracture plugging zone structure. In addition to sealing fractures, bridging materials with high compressive strength serve to maintain the fractures in an open state through the “stress cage” effect, thereby enhancing the stability of the fracture system. Walnut shell, cottonseed hulls, and similar walnut shell plugging materials remain extensively utilized for loss control in deep geological formations. However, organic rigid plugging materials like walnut shells tend to undergo aging reactions under conditions of high formation temperature and high salinity, which weaken their compressive strength. When the fracture closure stress surpasses the compressive strength of the fracture plugging zone, compressive failure of the plugging zone ensues, resulting in structural instability of the fracture sealing system (Fig. 17b). High temperatures can weaken the material structure, high salinity can lead to dissolution or precipitation affecting integrity, and pressure can cause particle degradation. The combined action reduces the compressive strength, resulting in failure.

Application of salt resistance evaluation in lost ciruclation control

In deep fractured rock drilling operations, the rational selection of loss control materials is crucial. However, current selections are predominantly based on experience and laboratory pressure resistance tests, often overlooking the specific environmental conditions of the formation. Particularly in high-salinity geological environments, dissolved salts may chemically react with plugging materials, altering their particle size distribution, compressive strength, and friction coefficient, thus impacting the effectiveness and stability of the sealing process. Consequently, evaluating the salt resistance of plugging materials is especially important. Salt resistance evaluation primarily involves testing the stability of plugging materials in highly mineralized fluids. This performance indicator supplements traditional evaluation methods—such as particle size distribution, acid solubility, compressive strength, and thermal resistance—providing a more comprehensive assessment of the material’s suitability under specific geological conditions. For instance, in highly saline deep formations of the Tarim Basin, commonly used plugging materials like walnut shells, millimeter-sized calcium carbonate, and cottonseed hulls continue to be widely employed in practice. However, their salt resistance often receives insufficient attention, leading to recurrent loss issues under high-salinity conditions. Additionally, optimizing the formulation of plugging materials is an effective strategy to enhance salt resistance. By adjusting the composition and ratio of materials and incorporating additives with high salt resistance, the performance of plugging materials in specific environments can be significantly improved. In summary, evaluating salt resistance is not only key to selecting and optimizing plugging materials but also essential for ensuring stability and safety in drilling operations within complex high-salinity environments. It is recommended that the drilling engineering field further research evaluation methods and optimization strategies for plugging materials under high-salinity conditions to reduce losses and improve drilling efficiency.

Conclusions

In this study, we systematically evaluated the performance of three lost circulation materials—organic materials, inorganic materials, and synthetic polymers—under high-salinity conditions, leading to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

Chemical and physical stability: The materials exhibited significant differences in saline-induced degradation and physical responses under saline conditions. Notably, the organic material walnut shell showed considerable mass loss and color change, indicating its susceptibility to chemical reactions and degradation in a saline environment. In contrast, millimeter-sized calcium carbonate demonstrated superior durability due to its stable mineral chemistry, exhibiting minimal mass loss. Synthetic polymers, while showing no significant color change, maintained high structural stability and experienced a decline in low friction performance, suggesting their potential suitability for high-salinity environments.

-

(2)

Friction and compressive strength: The frictional properties and compressive strength of lost circulation materials also varied with salinity. Organic materials, particularly after salt treatment, showed a significant decrease in friction coefficient, potentially compromising their load-bearing capacity within plugging zones. Conversely, inorganic materials displayed a degree of enhancement in compressive strength due to salt precipitation, indicating their superior performance in high-salinity conditions. These findings reveal the potential limitations and advantages of different materials in extreme environments and emphasize the importance of considering environmental factors in the selection and design of lost circulation materials.

-

(3)

Optimization and future research: To optimize lost circulation control strategies in deep fractured rock formations, it is recommended to further investigate and develop materials with high salt resistance and improved mechanical properties. Evaluating salt resistance should become a standard criterion in the selection and optimization process of lost circulation materials to ensure their sealing efficacy and structural stability in complex geological environments. These conclusions not only contribute to enhancing the safety and efficiency of field applications but also provide valuable scientific insights for the future development of lost circulation materials.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gou, Q. et al. Petrography and mineralogy control the nm-μm-scale pore structure of saline lacustrine carbonate-rich shales from the Jianghan Basin, Chian. Marine Petrol. Geol. 155, 106399 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. The role of underground salt caverns for large-scale energy storage: A review and prospects. Energy Storage Mater. 63, 103045 (2023).

Ozarslan, A. Large-scale hydrogen energy storage in salt caverns. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37(19), 14265–14277 (2012).

Thoms, R. L. & Gehle, R. M. A brief history of salt cavern use. In Proceedings of the 8th World Salt Symposium, 2, pp. 207–214 (Elsevier, 2000).

Onderka, V. Czech Republic 2006–2009 Triennium work Report. In Proceedings of the 24th world gas conference, (Argentina, 2009).

Selvadurai, A. P. S., Zhang, D. & Kang, Y. Permeability evolution in natural fractures and their potential influence on loss of productivity in ultra-deep gas reservoirs of the Tarim Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 58(162–177), 22 (2018).

Waber, H. N., Gimmi, T. & Smellie, J. A. T. Effects of drilling and stress release on transport properties and porewater chemistry of crystalline rocks. J. Hydrol. 405(3–4), 316–332 (2011).

Yan, X.et al. Plugging zone for wellbore strengthening in fractured reservoirs: Multiscale structure and structure characterization methods, Powder Technol. 370, 159–175 (2020).

Qin, P. et al. A unique saline lake sequence in the eastern Tethyan Ocean in responses to the PalaeoceneEocene thermal maximum: A case study in the Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin, NW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 250, 105594 (2023).

Zheng, Z. Q., Tian, S. X. & Jing, R., et al. Research progress of high temperature resistant loss circulation material while drilling. Exploration engineering (Rock & Soil Drilling and Tunneling), (2016).

Valsecchi, P. On the shear degradation of lost-circulation materials. SPE Drill. Complet. 29(03), 323–328 (2014).

Tan, Q. et al. The role of salt dissolution on the evolution of petrophysical properties in saline-lacustrine carbonate reservoirs: Pore structure, porosity–permeability, and mechanics. J. Hydrol. 618, 129257 (2023).

Sun, W., Li, W. & Zhang, D. Lost circulation monitoring using bi-directional LSTM and data augmentation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 225, 211650 (2023).

Calcada, L. A. et al. Evaluation of suspension flow and particulate materials for control of fluid losses in drilling operation. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 131, 1–10 (2015).

Singh, A. & Singh, S. CFD investigation on roughness pitch variation in non-uniform cross-section transverse rib roughness on Nusselt number and friction factor characteristics of solar air heater duct. Energy 128, 109–127 (2017).

Kang, Y., Chen, Q., Tian, J., Wang, Y. & Qin, C. Rapid assessment of water phase trapping on gas permeability reduction in typical tight gas reservoirs in China. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9, 168 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Spatial distribution of bed density in a Gas-solid Fluidized Bed Coal Beneficiator (GFBCB) using Geldart A− particles. Powder Technol. 436, 119349 (2024).

Aston, M., Alberty, M. W., Mclean, M. R., Jong, H. J. & Armagost, K. Drilling fluid for wellbore strengthening. In SPE Drilling Conference, (Dallas, Texas, USA, 2004).

E. F. Fracture Closure Stress (FCS) and Lost Returns Practices. In SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, (Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2005).

Van Oort, E., Friedheim, J. E., Pierce, T., Pierce, T. & Lee, J. Avoiding losses in depleted and weak zones by constantly strengthening wellbores. SPE Drill. Complet. 26(4), 519–530 (2011).

Feng, Y. C. & Gray, K. E. Modeling lost circulation through drilling-induced fractures. SPE J. 23(1), 205–223 (2017).

Lei, M. At present, the global drilling leakage rate accounts for about 20% to 25% of the total number of drillings, and the annual cost of plugging leakage is as high as $4 billion. Petrochemical intelligence network. (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Physical plugging of lost circulation fractures at microscopic level. Fuel 317, 123477 (2022).

Yang, C., Zhou, F. J. & Wei, F. Plugging mechanism of fibers and particulates in hydraulic fracture. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 176, 396–402 (2019).

Zhu, B. Y. et al. Experimental and numerical investigations of particle plugging in fracture-vuggy reservoir: A case study. J Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208(Part D), 109610 (2022).

Al-Saba, M. T., Nygaard, R. & Saasen, A., et al. Lost circulation materials capability of sealing wide fractures. In Paper presented at the SPE deepwater drilling and completions conference, (Galveston, Texas, USA, 2014).

Kang, Y., Xu, C., Tang, L., Li, S. & Li, D. Q. Constructing a tough shield around the wellbore: Theory and method for lostcirculation control. Pet. Explor. Dev. 41(4), 473–479 (2014).

Alsaba, M., Dushaishi, M. F. A., Nygaard, R., Nes, O. M. & Saasen, A. Updated criterion to select particle size distribution of lost circulation materials for an effective fracture sealing. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 149, 641–648 (2017).

Yan, Z. et al. Intrinsic mechanisms of shale hydration-induced structural changes. J. Hydrol. 637, 131433 (2024).

Lei, S. et al. Formation mechanisms of fracture plugging zone and optimization of plugging particles. Pet. Explor. Dev. 49(3), 684–693 (2022).

Yan, X. P., Huo, B. Z., Deng, S., Kang, Y. L. & He, Y. Clarify the effect of fracture propagation on force chains evolution of plugging zone in deep fractured tight gas reservoir based on photoelastic experiment. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212558 (2024).

Razavi, O., Vajargah, A. K., van Oort, E. & Aldin, M. Optimum particle size distribution design for lost circulation control and wellbore strengthening. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 35, 836–850 (2016).

Beardmore, D., Wade, Z., Evans, E. & Franks, K. Size degradation of granular lost circulation materials. In IADC/SPE drilling conference and exhibition, (San Diego, California, USA, 2012).

Kang, Y. et al. High-temperature aging property evaluation of lost circulation materials in deep and ultra-deep well drilling. Acta Petrolei Sinica 40(2), 215–223 (2019).

Yan, X. P. et al. The role of physical lost circulation materials type on the evolution of strong force chains of plugging zone in deep fractured tight reservoir. Powder Technol. 432, 119149 (2024).

Chengyuan, X., Xiaopeng, Y., Yili, K. & Lijun, Y. Structural failure mechanism and strengthening method of fracture plugging zone for lost circulation control in deep naturally fractured reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47(2), 430–440 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2806403), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240970), 2023 Science and Technology Innovation Talent Project of CNPC-CZU Innovation Alliance (CCIA 2023-10), the Postgraduate Research &Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX24 3249), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX25_1709). The authors would also like to acknowledge the useful suggestions from Professor. Yili Kang and Chengyuan Xu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XP.Y, LL.C, and BZ.H wrote the main manuscript text, and D.S contributed the ideas. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, X., Cao, L., Zhao, K. et al. Salt resistance property evaluation of lost circulation materials for wellbore strengthening in deep geological formations. Sci Rep 15, 19553 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03654-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03654-9