Abstract

Diabetes Mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder affecting a substantial global population leading to complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, foot problems, heart attacks, and strokes if left unchecked. Prompt detection and diagnosis are crucial in managing and averting these complications. This study compares the effectiveness of a Decision Tree Classifier and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) in predicting Diabetes Mellitus. The Decision Tree Classifier demonstrated superior performance, achieving a 97.7% accuracy rate compared to the ANN’s 94.7%. The Decision Tree Classifier also achieved higher precision (96.9% vs. 88.8%) and recall (96.5% vs. 90.2%) than the ANN, along with a balanced F1 score of 96.5% versus 90.2%. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) confirmed a stronger correlation between predictions and actual labels for the Decision Tree Classifier (87.4%) compared to the ANN (78%). Furthermore, the Area Under Curve (AUC) score of 96% for the Decision Tree Classifier was higher than that of ANN (78%). The relative importance feature analysis clearly established glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as the paramount factor in predicting diabetes mellitus. Diabetic patients showed markedly higher cholesterol and triglycerides, increasing cardiovascular risk, while High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) and Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) levels showed no significant difference between diabetics and non-diabetics. However, Very Low-Density Lipoprotein (VLDL) was significantly elevated, suggesting altered lipid transport in diabetes. Body Mass Index (BMI) was also notably higher in diabetics, reinforcing the link between obesity and diabetes risk. Principal Component analysis further highlighted five clusters of health-related variables, identifying age-related metabolic indicators (AGE, HbA1c, BMI), kidney function markers (creatinine (Cr), Urea), cardiovascular lipid profiles (Cholesterol, LDL), lipid transport (VLDL), and protective cardiovascular indicator (HDL). The study highlights the superiority of decision tree classifier in predicting Diabetes Mellitus, suggesting its potential for significant clinical applications in diagnosis and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes Mellitus is a chronic metabolic condition affecting a large global population in the world1. Timely detection and diagnosis are crucial for effectively managing and preventing complications resulting from this metabolic imbalance2,3. According to International Diabetic Federation (IDF) projections for 2045, it is anticipated that 1 in 8 adults, roughly 783 million individuals, will be affected by diabetes, representing about 46% increase4. The rise in type 2 diabetes cases is probably driven by urbanization, an aging population, less physical activity, and increased rates of overweight and obesity and Over 90% of the individuals with diabetes may have type 2 diabetes5. Diabetes prediction may be aided by clinical and sociodemographic factors such as glucose levels, family history, body mass index (BMI), and age6,7. According to research, machine learning algorithms, including Decision tree classifiers and ANN, have been effective in studying large diabetes datasets and delivering accurate predictions in the field8,9,10. Diabetes may be developed due to various reasons such as genetics, health habits, and external factors. Most often, diabetes is diagnosed by blood glucose levels; however, the blood glucose levels are affected by a number of factors including dietary intake, physical activity, level of stress, and medicinal drugs11. The use of artificial intelligence methods in prediction of diabetes may help to address the limitation of using blood glucose level as it is often affected by several factors. However, it is worth mentioning that demographic aspects such as family history of diabetes, age, and even BMI can also provide additional views on the risk of developing diabetes. Neural network and decision tree models are thought to be among the most rapid and user-friendly methods for learning from patterns in classified data12. Considered as classification and regression algorithms, decision trees and ANN have been gaining popularity in recent years for application in medicine due to their ease of use and interpretability13. The use of these algorithms in predicting the diabetes status may provide valuable support for early diagnosis and management of the disease in order to avoid the onset of complications such as cardiovascular disease, neuropathy, and retinopathy. The ability to predict diabetes using clinical parameters offers valuable opportunities to design personalized treatment plans, ultimately improving patient health outcomes. This study focuses on exploring the use of decision tree and ANN classifiers to assess diabetes diagnosis based on Biochemical and demographic parameters. The insights from this research could drive advancements in screening and diagnostic tools, enhancing patient care while easing the burden on healthcare systems.

Related works

This research takes a data-driven approach, utilizing decision tree classifiers and ANN to predict diabetes status based on biochemical indicators. The main goal is to extract actionable rules from these machine learning models to forecast whether a patient is diabetic14. A study uses the PIMA Indian Diabetes dataset for its predictive analysis and applies the Iterative Dichotomiser 3 (ID3) algorithm for classification15. Additionally, a novel method that combines decision trees and Naive Bayes within an ontology-based framework is proposed for both diabetes classification and prognosis16. To optimize the performance of these models, techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Genetic Algorithm (GA), and the Burota Package are employed for feature selection17. The research also explores different decision tree models, including LAD trees, Naive Bayes trees, and the Genetic J48 tree, with the Genetic J48 model proving to offer the best accuracy and efficiency18. The Decision Tree J48 algorithm, specifically, has been applied to predict diabetes based on biochemical parameters, providing greater efficiency and faster processing times for the dataset used19. A computational intelligence approach, integrating the Genetic Algorithm and Classification and Regression Trees (CART), has also been used, achieving a high classification performance of 96.05%20. Moreover, an ensemble learning model based on decision trees, specifically using the extra trees algorithm, has been shown to deliver exceptional accuracy, with a prediction accuracy of 99.2%21. In numerous studies, diabetes has been diagnosed and classified using ANN as predictive models. For instance, researchers presented a data-oriented approach of classifying diabetes by a model which incorporates flash glucose monitoring data, which has been found to be very specific and accurate in classifying different types of diabetes22. Su developed a predictive model of diabetic retinopathy based on ANN and its classification performance was better than that of traditional logistic regression models23. Raihan et al. developed predictive model for diabetes using ANN and achieved an average-weighted accuracy of about 99.69%24. Gulumbe et al. developed a model based on ANN for prediction of diabetes mellitus and found increased accuracy and better differentiation between diabetic and non-diabetic patients25. Nabiruma and kabari developed a diabetes diagnostic system with the use of a feed-forward neural network and achieved a success rate of 90%26. Training of the ANN models has been reported to use backpropagation algorithms25 and artificial backpropagation scaled conjugate gradient neural network27. The evaluations of these models were done using accuracy and mean squared error. Results confirm the effectiveness and the accuracy of the ANN models in predicting the occurrence of diabetes disease given the relevant data attributes. Furthermore, other non-invasive methods eg. iris image analysis has also been attempted for prediction of diabetes with training and testing data accuracy rates of 91.54% and 89.05% respectively28. A study compared three models including logistic regression, ANNs, and decision trees to predict diabetes using data from 735 patients and 752 controls in Guangzhou, China and reported that decision tree model performed best in accuracy, followed by logistic regression, while ANNs had the lowest accuracy29. Another study evaluated machine learning models for predicting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and prediabetes using the NHANES dataset. The ensemble model achieved AU-ROC scores of 83.1% (without lab data) and 83.9% (with lab data) for cardiovascular disease, with key predictors including age, blood pressure, weight, and chest pain occurrence. For diabetes, XGBoost performed best, scoring 86.2% (without lab data) and 95.7% (with lab data), with waist size, age, weight, leg length, and sodium intake as top predictors30. In prediabetes detection, the ensemble model scored 73.7% without lab data, while XGBoost achieved 84.4% with lab data. The results demonstrate machine learning’s potential in automating early disease detection based on survey data30. A study also explored machine learning (ML) models for predicting type 2 diabetes using common symptoms as features. Various models were evaluated based on Precision, Recall, F-Measure, Accuracy, and AUC metrics using tenfold cross-validation and data splitting. The results identified Random Forest and K-NN as the best-performing models, demonstrating ML’s potential in early diabetes diagnosis and risk prediction31. Research used machine learning and neural networks to predict diabetes using the Pima Indian Diabetes dataset. Seven machine learning algorithms were tested, with Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machine performing well. A neural network model with two hidden layers achieved the highest accuracy of 88.6%32.

Materials and methods

Dataset retrieval and description

The dataset that was used in this research comprises of 1000 patients who received treatment in the well-known Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital in Iraq33. The age of the patients ranges from 20 to 79 years. In this cohort, there were recorded 435 females and 565 males which has enhanced the dataset with a more critical demographic component. The diabetic patients within this cohort were carefully and precisely placed in to 3 groups: there were 837 who were Diabetic (Y), 103 who were Non-Diabetic (N) and 53 who were probable Diabetic (P). This stratification forms a crucial foundation for the subsequent analyses and predictions. The dataset is comprehensive, encompassing data on 11 important biochemical indicators. These include Blood Sugar Level, Age, Gender, Creatinine ratio (Cr), Body Mass Index (BMI), Urea, Cholesterol (Chol), Fasting lipid profile (including total, LDL, VLDL, Triglycerides (TG), and HDL Cholesterol), and HBA1C. Each of these indicators has been recorded from thorough clinical examinations, providing a robust foundation for our analytical endeavors. The summary of the description was given in Table 1.

Proposed methodology

The proposed methodology hinges on leveraging clinical datasets obtained directly from patients. To streamline our approach, we organized it into two distinct methods: the experimental approach and the data-driven approach (Fig. 1). The experimental approach entails the systematic collection of samples from patients, followed by sample processing and in-depth clinical investigation. This results into the classification of patients into three categories: diabetic, non-diabetic, and predicted diabetics. On the other hand, the data-driven approach is centered around comprehensive data handling. This encompasses tasks such as data input, rigorous processing, judicious model selection, meticulous modeling, and thorough performance evaluation, with a particular focus on achieving the lowest possible error value. This comprehensive approach ensures that our methodology is robust and reliable in predicting diabetic conditions.

Models used for prediction

Decision tree classification

Decision tree classification is machine learning algorithm, which make the use of a tree-like structure (Fig. 2) to classify data into known classes34. This tree consists of nodes representing some attribute of the data along with branches leading to the potential outcomes for each attribute35. At the terminal end of every branch is a leaf node that shows a class label for data; in other words, this class label is determined according to the path taken through the tree. The construction of a decision tree classification algorithm starts with the identification of the most informative attribute to be used as the root node. Datasets can be partitioned into subsets based on the various values of a specific attribute. At each node, the selected split criterion influences the arrangement of the class members. This process continues until the datasets achieve complete homogeneity or a predetermined stopping rule is met, such as reaching the maximum allowable leaf nodes or maintaining a consistent number of instances in each leaf node. Once the decision tree classification is constructed, it can be utilized to predict class labels for unseen instances by navigating from the root node to the leaves and evaluating the instance attribute values against the split criteria at each node36. The predicted class label corresponds to the class found in the leaf node where the instance concludes its path. The decision tree classification algorithm derives its strengths from its intrinsic simplicity, interpretability, and efficiency37. This algorithm is capable of accommodating both categorical and numerical data. For this algorithm, parameters such as a maximum depth of 4, a minimum of 8 samples per leaf, and cost-complexity pruning were set to prevent overfitting. Gini impurity criterion was applied for splitting with minimum split threshold adjusted to − 0.862, − 1.04, and 0.067, ensuring that each split meaningfully improved classification. Additionally, pruning was applied, leading to simplified final nodes where samples were grouped into classifications. The dataset was partitioned into two segments, with 80% allocated for training and 20% designated for testing. A summary of the datasets, including the training and testing sets, is presented in Table 2.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

An ANN is a computational model conceived from the way biological neural networks in the human brain work, and it is regarded as one of the central foundations of machine learning and artificial intelligence, conceived to imitate the learning capabilities of the human brain in recognizing patterns, making decisions, or executing tasks38. The basic structural unit of an ANN is the neuron, an abstract mathematical function that consumes input, processes it through several weights, applies an activation function, and produces output. Thus, neurons are organized into layers: an input layer for external information, one or several hidden layers for processing this information, and an output layer for generating results39. Training of an ANN involved exposing a set of labeled examples (training data) so it may learn the underlying relationships and patterns. In the training process, the network adjusts its internal weights to minimize the differences between its predicted outputs and the actual labels. This process is mostly achieved with optimization algorithms, for instance, gradient descent. ANNs can be classified based on the architectures, including, but not limited to, feedforward neural networks, recurrent neural networks, and convolutional neural networks, each suited to a certain specific type of tasks40. Feedforward neural networks are suited most to traditional tasks, such as classification and regression, while recurrent neural networks provide a more useful way of dealing with the features of sequential data, and convolutional neural networks are best used for tasks related to the recognition of images and patterns. The broad acceptance of ANN has marked the significant evolution of various other fields, such as computer vision, natural language processing and speech recognition. The effectiveness of ANN is enhanced by the adaptability and learning which help in solving complex problems and making them to have more applicability in machine learning41. ANN algorithms can handle many challenges, spanning from modeling brain function to resolving intricate computational issues. These algorithms make use of feedforward network, which can be trained to understand the relationship between the datasets. These inherent characteristics make them ideal for use in tasks like interpolation, classification, and optimization. ANN have effective in various task, including transformer fault diagnosis42, dynamic programming43, battery management systems44, and stellar spectra classification45. Several features such as distributed parallel processing, self-learning, self-adaptation, and nonlinear mapping, makes them to be algorithm of choice in artificial intelligence and data analysis. For the ANN analysis, the network architecture comprised three primary layers: an input layer with 10 neurons, two hidden layers containing 6 and 3 neurons, and an output layer with 2 neurons. It was fully connected, incorporating an intercept term in the first hidden layer to facilitate flexible decision boundaries. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using Random Search. The dataset was divided into two, 80% for training and 20% for testing. The summary of the datasets, training sets and testing sets were given in Table 2.

Models validation

A hold-out cross-validation method, in which the dataset was divided into two sets: training and validation. This validation, however, can also be accomplished with other validation methods, such as k-fold cross-validation, holdout, or leave one out. Since k-fold has a more complex procedure, holdout is often thought to be the most basic version of k-fold cross-validation46.

Evaluation metrics used for the models

The model evaluation criteria include level of accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and an impressive Area Under Curve (AUC) score shown from Eq. 1–5.

where TP: Number of true positives, TN: Number of true negatives, FP: Number of false positives, FN: Number of false negatives.

Statistical analysis

Independent t-test

This statistical method was used to determine whether the means of the two data sets (diabetes and non-diabetes) differ significantly. Specifically, an independent sample t-test (Eq. 6) was applied to compare the means of diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

where \({\overline{\text{x}}}^{1}\) and \({\overline{\text{x}}}^{2}\) are the sample means of diabetics and non-diabetics, S21 and S22 are the sample variances of diabetics and non-diabetics, n1 and n2 are the sample sizes of diabetics and non-diabetics.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique used to transform high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving as much variance as possible. It is widely used in data analysis, machine learning, and bioinformatics. PCA extracts K principal components by solving the characteristic equation of the correlation matrix of observed variables (Eq. 7). The eigenvalues, arranged in descending order, indicate the proportion of variance accounted for by each component47.

The principal component model is expressed as:

where Fi is the i-th principal component, Tij is the loading of the i-th component on the j-th variable, m is the number of principal components, k is the number of indicators.

Results

Results for decision tree and ANN

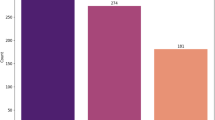

Across a broad range of important evolution metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, MCC and AUC score, The decision tree classifies consistently outperformed the rest of the models (Fig. 3). More specifically, the decision tree classifier recorded an accuracy of 97.7%, outperforming the ANN by 3%, which recorded an accuracy of 94.7%. This high Evaluation metric scores illustrated that the model is very effective in making accurate predictions, accurately classifying patients into clear diabetes and no diabetes classes. The decision tree classifier achieved a higher precision (96.9%) as compared to the ANN (88.8%), highlighting its exceptional performance in accurately classifying diabetes positive cases. The recall (sensitivity) of the Decision Tree Classifier was an outstanding 96.5%, demonstrating its ability to capture a large number of actual positive cases. Moreover, the F1 score exhibited a score of 96.5%, demonstrating that the model was robust in predictive power, while the ANN received a scored 90.2%. The high MCC additional indicated that the strong correlation between the prediction of Decision Tree Classifier and actual labels (MCC of 87.4%), surpassing the ANN (MCC of 78%). Additionally, the exceptional AUC score of 96% for the Decision Tree Classifier, compared to 78% for the ANN, highlighted the former’s exceptional discriminatory power in distinguishing between positive and negative cases.

The relative importance feature analysis clearly established HbA1c as the principal factor in predicting diabetes mellitus through the decision tree model. Subsequently, BMI and age emerged as secondary and third influential variables in the prediction process. This hierarchy of importance highlights the pivotal role of HbA1c levels in the accurate identification of diabetes mellitus, followed closely by BMI and age in significance. The confusion matrix (Tables 3 and 4) represents how well a decision tree Classifier and ANN performed in predicting three classes (N, P, and Y). This confusion matrix, therefore gives detailed information about the model’s accuracy in classifying variables, which is vital for assessing its effectiveness and identifying areas for potential improvement (Tables 3 and 4). The relative importance features presented the most important factors in predicting diabetes (Fig. 4). The visualization of these models are presented through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) graphs, which illustrate both the true positive rate and false positive rate (Fig. 5a,b). In this instance, the graphs demonstrate a perfect distinction between the analyzed classes. ROC graphs are widely employed in medical decision-making and have witnessed a surge in usage within machine learning and data mining research in recent years48,49. The data was visualized using Andrews curve plots, which project high-dimensional data into a 2D space50. These curves are generated by transforming data features into sinusoidal functions. Classification information has been visually represented through colors (Fig. 6a,b). In the context of pattern recognition, comparable patterns in the curves suggest similarity among data points in the high-dimensional space, while dissimilar patterns indicate differences in the feature space (Fig. 6a,b). The decision tree plot illustrates a hierarchical, tree-like structure comprising a root node, branches, internal nodes, and leaf nodes. In this particular case, BMI acts as the root, while the remaining biochemical indicators function as branches and internal nodes. The ultimate target, namely the diabetes status, is represented by the leaf nodes. According to the decision tree plot, the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) represent the most influential factor in determine status of diabetes (Fig. 7).

The accuracy of the neural network classification increases over 10 generations, with validation accuracy slightly surpassing training accuracy by the end, suggesting effective learning and generalization. The accuracy range is between 84 and 94%. The network uses a sigmoid activation function, smoothly mapping inputs from − 6 to 6 to outputs between − 1 and 1, which aids in adapting to data variations (Fig. 8). The network architecture includes three main layers: an input layer with 10 neurons, two hidden layers with 6 and 3 neurons, and an output layer with 2 neurons. It is fully connected, with an intercept term in the first hidden layer for flexible decision boundaries (Fig. 8).

Results for correlational analysis between the evaluated biochemical indicators

The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) heatmap provides a comprehensive visual representation of the relationships between the evaluated biochemical indicators (Fig. 9). This statistical measure quantifies the strength and direction of the linear association between two variables. A higher positive value on the heatmap signifies a more pronounced positive correlation, indicating that as one variable increases, the other tends to increase as well. Conversely, a higher negative value indicates a substantial negative correlation, suggesting that as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease.

Results of independent t-test of biochemical parameters between diabetic and non-diabetic patient

Age appears to correlate with diabetes prevalence, as diabetic patients in the study have a higher mean age (55.31 ± 7.55 years) than non-diabetic patients (44.23 ± 9.42 years) (Table 5), with a statistically significant p-value of less than 0.0002. This suggests that age might be a contributing risk factor for developing diabetes or could be associated with an increased likelihood of its onset.

Urea levels are marginally higher in diabetic patients (5.22 ± 3.02 mmol/L) compared to non-diabetics (4.68 ± 2.52 mmol/L), with a p-value of 0.0479, pointing to mild renal involvement in diabetes. However, Cr levels, while somewhat elevated in diabetic patients (69.87 ± 63.58 µmol/L) versus non-diabetics (62.80 ± 30.02 µmol/L), do not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0556), indicating that the renal impact may be subtle or variable across individuals.

The HbA1c levels show a stark difference, with diabetic patients exhibiting a significantly elevated mean HbA1c of 8.88 ± 2.26% compared to 4.56 ± 0.92% in non-diabetic patients, resulting in a p-value of less than 0.0022. This confirms HbA1c as a reliable indicator of diabetes, useful both in screening and ongoing glycemic management.

In terms of lipid metabolism, diabetic patients have markedly higher cholesterol (Chol) levels (4.95 ± 1.30 mmol/L) than non-diabetics (4.27 ± 1.28 mmol/L), with a p-value of less than 0.0001 (Table 5), suggesting lipid dysregulation in diabetes. Similarly, triglyceride (TG) levels are significantly higher in diabetics (2.45 ± 1.43 mmol/L) than in non-diabetics (1.63 ± 1.03 mmol/L), with a p-value of less than 0.0001 (Table 5). These differences highlight the increased cardiovascular risk associated with diabetes.

Interestingly, no significant difference is found in HDL levels between diabetic (1.21 ± 0.69 mmol/L) and non-diabetic (1.23 ± 0.51 mmol/L) groups (p = 0.7171), nor in LDL levels (diabetics: 2.62 ± 1.14 mmol/L; non-diabetics: 2.63 ± 0.98 mmol/L) with a p-value of 0.9236, suggesting that these lipid components may not be as impacted by diabetes as other lipid fractions. However, VLDL levels are notably higher in diabetics (2.02 ± 3.93 mmol/L) compared to non-diabetics (0.94 ± 1.48 mmol/L), with a p-value of less than 0.0012, indicating altered lipid transport linked to diabetes.

The BMI is considerably higher in diabetic patients (30.81 ± 4.32) than in non-diabetic individuals (22.37 ± 1.42), with a statistically significant p-value of less than 0.0022 (Table 5). This observation aligns with the well-documented relationship between obesity and diabetes risk, highlighting BMI as an essential factor in diabetes pathophysiology.

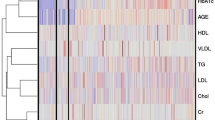

Results of principal component analysis

The component analysis revealed five distinct clusters of health-related variables (Fig. 10). RC1, associated with metabolic health and age, includes AGE, HbA1c, and BMI, linking it to age-related metabolic markers. RC2 focuses on kidney function, with high loadings of Cr (Creatinine) and Urea. RC3 represents a cardiovascular lipid profile, where Cholesterol and LDL are prominent, indicating a connection to cardiovascular risk. RC4, dominated by VLDL, suggests an emphasis on lipid transport and triglyceride association. Finally, RC5, with a strong association with HDL, serves as a protective cardiovascular indicator. Parallel analysis and the scree plot confirm these five components, each reflecting a unique health domain, thereby providing a structured approach to assess key health aspects, including metabolic age, kidney function, and cardiovascular health.

Discussion

This study clearly demonstrates the superior predictive performance of the decision tree classifier compared to the ANN in classifying individuals with and without diabetes. The results align with those of another study, which found that the J48 tree achieved a higher accuracy compared to the multilayer perceptrons in neural networks51. A study also reported that decision tree outperformed logistic regression and ANN in predicting diabetes in a Nigerian population52. A research uses four algorithms including decision tree, bagging with decision tree, random forest, and extra trees and concluded that the extra trees algorithm achieved the highest accuracy at 99.2% for early diabetes prediction53. Across a comprehensive range of performance metrics, the decision tree consistently outperformed the ANN, reinforcing its reliability and effectiveness in this specific predictive task.

Machine learning represents a cutting-edge method for assessing the status of diabetes through the use of clinical, biochemical, and demographic data. These algorithms effectively predict conditions such as diabetes by analyzing complex interrelationships among various medical parameters54. This capability enables insights that are nearly unattainable for human evaluators. Among the machine learning techniques, decision trees stand out as a particularly effective approach for diabetes prediction, as they can adeptly manage both categorical and continuous data, essential for medical applications where patient information can be quite varied30. A significant advantage of decision trees was their capacity to visualize and elucidate the decision-making process55, making them especially beneficial for healthcare professionals seeking to comprehend the factors influencing diabetes predictions. In contrast to artificial neural networks, which utilize neurons and layers for predictions, decision trees can readily identify the most significant predictors, allowing healthcare providers to prioritize their interventions. They are versatile tools that can be employed for both classification and regression tasks, which is particularly applicable in predicting diabetes status, where the outcome may be binary (diabetic or not) or continuous (such as blood glucose levels). Furthermore, decision trees are capable of handling missing data, a frequent challenge in medical datasets. Consequently, decision trees are an invaluable resource for predicting diabetes status due to their aptitude for accommodating diverse data types, identifying critical predictors, and providing a clear and interpretable decision-making framework56.

Feature importance analysis indicates that HbA1c is the most significant variable for predicting diabetes mellitus within the Decision Tree model, followed closely by Body Mass Index (BMI) and age. This hierarchical ranking of predictive features is consistent with existing literature that identifies HbA1c as a primary indicator of diabetes status57. Grasping the significance of each feature enhances the refinement of prediction strategies and emphasizes the variables that clinicians and researchers should prioritize in assessing diabetes risk. The effectiveness of the models was further illustrated through the use of confusion matrices (Tables 3 and 4) for three classes (N, P, and Y), providing a comprehensive breakdown of the classification accuracy of the models. The matrices reveal that the Decision Tree performed exceptionally well in accurately categorizing each class, highlighting its efficiency in classifying multiple diabetes-related categories. Additionally, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) graphs (Fig. 5a,b) provided a visual confirmation of the decision tree’s performance, showcasing a distinct separation between positive and negative cases, which is essential for informed medical decision-making. Andrews curve plots (Fig. 6a,b) were also utilized to visualize classification information, projecting high-dimensional data into 2D space and revealing patterns within the dataset. Similar patterns noted in the Andrews curves suggest analogous data points and highlight areas where the model successfully grouped similar cases together58.

The decision tree plot (Fig. 7) provides a hierarchical representation of the classification process59, with BMI positioned as the root node, while other variables such as HbA1c serve as crucial branches in the tree. This structure illustrates how the model prioritizes variables during the classification process. The plot emphasizes the pivotal role of HbA1c in determining diabetes status, showcasing the model’s interpretability and relevance in clinical practice. The interpretability and feature importance within the decision tree classifier are aligned with its appropriateness for medical prediction tasks60. Its consistent performance across various metrics establishes it as a trusted option for diabetes prediction, particularly in scenarios where accurate classification is of utmost importance61. In contrast, although the ANN achieved satisfactory results, its lower precision and AUC scores reveal constraints in its ability to capture nuanced patterns within the dataset. Future research could investigate the integration of decision trees with other algorithms (e.g., ensemble methods) to bolster robustness, further enhance performance, and potentially address limitations observed in the ANN model.

The observed trend in classification accuracy across epochs indicates a consistent enhancement in the performance of the neural network (Fig. 8), evident in both the training and validation sets62. Remarkably, towards the conclusion, the validation accuracy slightly surpasses the training accuracy, implying that the network is not overfitting but is instead generalizing effectively to unseen data. This behavior is indicative of effective model training and suggests that the network has adequately captured the inherent data patterns. The reported accuracy range of 84% to 94% aligns with the high-performance benchmarks for similar tasks, reinforcing the model’s robustness. The deployment of a sigmoid activation function is pivotal to its adaptability, as it facilitates a smooth, continual response to various input values63. This seamless transition, extending from − 1 to 1 as inputs progress from − 6 to 6, provides a stable gradient for backpropagation, ensuring effective learning within the network. The characteristics of the sigmoid function curve empower the network to flexibly respond to diverse data inputs, which is crucial for capturing intricate relationships and supports the observed enhancement in accuracy over epochs.

An independent T-test comparing biochemical parameters between diabetic and non-diabetic patients revealed significant differences, with age identified as a potential risk factor for diabetes64. Diabetic patients exhibited elevated urea levels; however, the differences in creatinine were not significant, indicating mild renal involvement65. The increased levels of HbA1c in diabetic patients confirmed its efficacy as a reliable marker for diabetes, consistent with findings from another study66. Furthermore, diabetic patients demonstrated markedly higher cholesterol and triglyceride levels, which heightens cardiovascular risk, whereas HDL and LDL levels did not show significant disparities between the groups67. Nonetheless, VLDL levels were significantly elevated, indicating alterations in lipid transport associated with diabetes. Additionally, the body mass index (BMI) was considerably higher in diabetic patients, further substantiating the connection between obesity and diabetes risk68.

The results derived from the component analysis (Fig. 10) provide important insights into the clustering of health-related variables, underscoring specific health domains represented by each component. RC1, which encompasses AGE, HbA1c, and BMI, indicates metabolic health factors associated with aging. This association suggests that as age increases, related variables, such as HbA1c and BMI, may exhibit corresponding trends that reflect metabolic changes due to aging64. RC2, characterized by creatinine (Cr) and urea, is explicitly indicative of renal function, as these markers serve as direct indicators of kidney health and waste filtration efficiency, emphasizing this component’s role in identifying renal impairments or stress. In RC3, Cholesterol and LDL levels suggest a focus on lipid profile as it relates to cardiovascular health risks. Elevated levels of LDL and total cholesterol are known to increase cardiovascular risk, and this component provides a valuable lens to assess lipid-related cardiovascular threats69. RC4, dominated by VLDL, points to lipid transport and triglyceride involvement, since VLDL is responsible for transporting triglycerides from the liver to peripheral tissues, thus connecting to metabolic processes involving fat transport and storage70. Finally, The RC5 high association with HDL positions it as a protective cardiovascular marker, as HDL is often referred to as “good cholesterol” due to its role in transporting cholesterol away from arteries and back to the liver for excretion71.

Clinical practice and research applications

The decision tree classifier demonstrates superior accuracy, precision, recall, and discriminatory power compared to the ANN, making it a valuable tool for the clinical diagnosis and management of Diabetes Mellitus. Its high Matthews Correlation Coefficient and AUC indicate reliable alignment with actual outcomes, suggesting its suitability for high-accuracy clinical decision-making.

Elevated HbA1c, BMI, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels can aid in screening individuals at high risk for diabetes, especially among middle-aged populations. These markers can also serve as essential indicators in the regular monitoring of diabetic patients to manage complications effectively. The lipid profile, particularly elevated triglycerides and VLDL, provides critical insights into cardiovascular risk, enabling healthcare providers to offer targeted advice on lifestyle changes and pharmacological interventions. Moreover, the relationship between BMI and diabetes highlights the value of patient education and lifestyle management. weight management programs focused on diet and exercise may help reduce diabetes risk or mitigate its progression in those already affected. The findings also have implications for pharmacological intervention, as medications targeting lipid abnormalities (e.g., statins for cholesterol and triglycerides) and glycemic control (e.g., drugs to lower HbA1c) could be prioritized based on specific biomarker levels to improve patient outcomes. Finally, these results may guide Preventative Healthcare initiatives. For example, healthcare systems could develop community-based programs for high-risk groups, especially targeting older adults and individuals with obesity, to provide preventive education, screening, and early interventions to curb the diabetes epidemic.

Conclusions

The decision tree classifier demonstrated superior performance over the ANN in predicting Diabetes Mellitus from biochemical indicators. These results highlight the significant potential for clinical applications of these models in the diagnosis and management of diabetes. Our findings confirm HbA1c as a reliable biomarker for diabetes diagnosis, with diabetics showing notably higher levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and VLDL, all of which elevate cardiovascular risk, though HDL and LDL levels did not differ significantly from non-diabetics. Elevated BMI in diabetics further emphasizes the link between obesity and diabetes. Principal Component Analysis identified five key health clusters: age-related metabolic indicators (AGE, HbA1c, BMI), kidney function markers (Cr, Urea), cardiovascular lipid profiles (Cholesterol, LDL), lipid transport (VLDL), and protective cardiovascular indicators (HDL).

Data availability

Dataset used in this study can found at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wj9rwkp9c2/1

References

Wu, Y.-Y., Xiao, E. & Graves, D. T. Diabetes mellitus related bone metabolism and periodontal disease. Int. J. Oral Sci. 7, 63–72 (2015).

Vashist, P., Singh, S., Gupta, N. & Saxena, R. Role of early screening for diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: An overview. Indian J. Community Med. 36, 247 (2011).

Zakir, M. et al. Cardiovascular complications of diabetes: From microvascular to macrovascular pathways. Cureus 15, e45835 (2023).

Diabetes Facts and Figures | International Diabetes Federation, (n.d.). https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed February 9, 2025).

Cho, N. H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281 (2018).

Ohlson, L.-O. et al. Risk factors for type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Thirteen and one-half years of follow-up of the participants in a study of Swedish men born in 1913. Diabetologia 31, 798–805 (1988).

Kyrou, I. et al. Sociodemographic and lifestyle-related risk factors for identifying vulnerable groups for type 2 diabetes: A narrative review with emphasis on data from Europe. BMC Endocr. Disord. 20, 1–13 (2020).

Chen, W., Chen, S., Zhang, H. & Wu, T. A hybrid prediction model for type 2 diabetes using K-means and decision tree. In: 2017 8th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), IEEE, 2017, pp. 386–390.

Charbuty, B. & Abdulazeez, A. Classification based on decision tree algorithm for machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2, 20–28 (2021).

Kavakiotis, I. et al. Machine learning and data mining methods in diabetes research. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 15, 104–116 (2017).

Murea, M., Ma, L. & Freedman, B. I. Genetic and environmental factors associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications. Rev. Diabet Stud. 9, 6 (2012).

Ziweritin, S. et al. A comparative analysis of neural network and decision tree model for detecting result anomalies. Open Access Libr. J. 9, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4236/OALIB.1108549 (2022).

Herrera-Viedma, E. et al. Decision trees: From efficient prediction to responsible AI. Front. Artif. Intell. 6, 1124553. https://doi.org/10.3389/FRAI.2023.1124553 (2023).

Bhattacharya, M. & Datta, D. Diabetes prediction using logistic regression and rule extraction from decision tree and random forest classifiers. In: 2023 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–7.

Thotad, P., Bharamagoudar, G. R. & Anami, B. S. Predictive analysis of diabetes mellitus using decision tree approach. In: 2022 2nd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–7.

Okikiola, F. M., Adewale, O. S. & Obe, O. O. An ontology-based diabetes prediction algorithm using Naïve bayes classifier and decision tree. In: 2023 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG), IEEE, 2023: pp. 1–11.

Sadhasivam, J., Muthukumaran, V., Raja, J. T., Joseph, R. B., Munirathanam, M. & Balajee, J. M. Diabetes disease prediction using decision tree for feature selection. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. IOP Publishing, 2021: p. 62116.

Dwivedi, K., Sharan, H. O. & Vishwakarma, V. Analysis of decision tree for diabetes prediction. Int. J. Eng. Techn. Res. 9, 3–6 (2019).

Posonia, A. M., Vigneshwari, S. & Rani, D. J. Machine learning based diabetes prediction using decision tree J48. In: 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS), IEEE, 2020: pp. 498–502.

Pekel, E. & Özmen, E. P. Computational intelligence approach for classification of diabetes mellitus using decision tree. In: Computational Intelligence and Soft Computing Applications in Healthcare Management Science, IGI Global, 2020, pp. 87–103.

Sen Kaya, O., Keser, S. B. & Keskin, K. Early stage diabetes prediction using decision tree-based ensemble learning model. Int. Adv. Res. Eng. J. IAREJ 7, 62–71 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Graph convolutional network enabled two-stream learning architecture for diabetes classification based on flash glucose monitoring data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 69, 102896 (2021).

Su, B. Using metabolic and biochemical indicators to predict diabetic retinopathy by back-propagation artificial neural network. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome Obes. 4031–4041 (2021).

Raihan, M., Alvi, N., Tanvir Islam, M. & Farzana, F. & Mahadi Hassan, M. Diabetes mellitus risk prediction using artificial neural network. In: Proceedings of International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence: IJCCI 2019, Springer, 2020, pp. 85–97.

Gulumbe, S. U., Suleiman, S., Badamasi, S., Tambuwal, A. Y. & Usman, U. Predicting diabetes mellitus using artificial neural network through a simulation study. Mach. Learn. Res. 4, 33 (2019).

Orukwo, J. O. & Kabari, L. G. Diagnosing diabetes using artificial neural networks. Eur. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 5, 221–224 (2020).

Bukhari, M. M. et al. An improved artificial neural network model for effective diabetes prediction. Complexity 2021, 1–10 (2021).

Putri, R. & Saputro, A. H. Prediction instrument of diabetes mellitus based on iridology image and artificial neural network: Initial findings. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Smart Instrumentation, Measurement and Application (ICSIMA), IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

Meng, X.-H., Huang, Y.-X., Rao, D.-P., Zhang, Q. & Liu, Q. Comparison of three data mining models for predicting diabetes or prediabetes by risk factors. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 29, 93–99 (2013).

Dinh, A., Miertschin, S., Young, A. & Mohanty, S. D. A data-driven approach to predicting diabetes and cardiovascular disease with machine learning. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 1–15 (2019).

Dritsas, E. & Trigka, M. Data-driven machine-learning methods for diabetes risk prediction. Sensors 22, 5304 (2022).

Khanam, J. J. & Foo, S. Y. A comparison of machine learning algorithms for diabetes prediction. ICT Express 7, 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ICTE.2021.02.004 (2021).

Rashid, A. Diabetes dataset. Mendeley Data 1 (2020).

Aghaei, S., Gómez, A. & Vayanos, P. Strong optimal classification trees. arXiv Preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2103.15965 (2021).

Srivastava, A., Han, E.-H., Kumar, V. & Singh, V. Parallel formulations of decision-tree classification algorithms. High Perform. Data Min. Scal. Algorithms Appl. Syst. 3, 237–261 (2002).

Yang, H. & Fong, S. Incremental optimization mechanism for constructing a decision tree in data stream mining. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 580397 (2013).

Liu, W., Fan, H. & Xia, M. Credit scoring based on tree-enhanced gradient boosting decision trees. Expert Syst. Appl. 189, 116034 (2022).

Agatonovic-Kustrin, S. & Beresford, R. Basic concepts of artificial neural network (ANN) modeling and its application in pharmaceutical research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 22, 717–727 (2000).

Emmert-Streib, F., Yang, Z., Feng, H., Tripathi, S. & Dehmer, M. An introductory review of deep learning for prediction models with big data. Front. Artif. Intell. 3, 4 (2020).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 8, 1–74 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. A review of machine learning in building load prediction. Appl. Energy 285, 116452 (2021).

Wu, Y. & Feng, J. Development and application of artificial neural network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 102, 1645–1656 (2018).

Chiu, C., Maa, C.-Y. & Shanblatt, M. A. An artificial neural network algorithm for dynamic programming. Int. J. Neural Syst. 1, 211–220 (1990).

Gao, Z., Chin, C. S., Woo, W. L., Jia, J. & Da Toh, W. Genetic algorithm based back-propagation neural network approach for fault diagnosis in lithium-ion battery system. In: 2015 6th International Conference on Power Electronics Systems and Applications (PESA), IEEE, 2015: pp. 1–6.

Kukreja, H., Bharath, N., Siddesh, C. S. & Kuldeep, S. An introduction to artificial neural network. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 1, 27–30 (2016).

Abba, S. I. & Usman, A. G. Simulation for response surface in the HPLC optimization method development using artificial intelligence models: A data-driven approach. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 201, 104007 (2020).

Zou, Q. et al. predicting diabetes mellitus with machine learning techniques. Front. Genet. 9, 416440. https://doi.org/10.3389/FGENE.2018.00515/BIBTEX (2018).

Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 27, 861–874 (2006).

Muppalaneni, N. B., Ma, M., Gurumoorthy, S., Kannan, R. & Vasanthi, V. Machine learning algorithms with ROC curve for predicting and diagnosing the heart disease. Soft Comput. Med. Bioinf. 63–72 (2019).

Andrews, D. F. Plots of high-dimensional data. Biometrics 28, 125–136 (1972).

Ahmad, A., Mustapha, A., Zahadi, E. D., Masah, N. & Yahaya, N. Y. Comparison between neural networks against decision tree in improving prediction accuracy for diabetes mellitus. in: Digital Information Processing and Communications: International Conference, ICDIPC 2011, Ostrava, Czech Republic, July 7–9, 2011, Proceedings, Part I, Springer, 2011: pp. 537–545.

Odukoya, O. et al. Development and comparison of three data models for predicting diabetes mellitus using risk factors in a Nigerian population. Healthc. Inf. Res. 28, 58. https://doi.org/10.4258/HIR.2022.28.1.58 (2022).

Sen Kaya, O., Keser, S. B. & Keskin, K. Early stage diabetes prediction using decision tree-based ensemble learning model. Int. Adv. Res. Eng. J. 7, 62. https://doi.org/10.35860/IAREJ.1188039 (2023).

Maniruzzaman, M., Rahman, M. J., Ahammed, B. & Abedin, M. M. Classification and prediction of diabetes disease using machine learning paradigm. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 8, 1–14 (2020).

Banerjee, M., Reynolds, E., Andersson, H. B. & Nallamothu, B. K. Tree-based analysis: A practical approach to create clinical decision-making tools. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 12, e004879 (2019).

Lv, X. et al. Unveiling diagnostic information for type 2 diabetes through interpretable machine learning. Inf. Sci. N. Y. 690, 121582 (2024).

Lugner, M., Rawshani, A., Helleryd, E. & Eliasson, B. Identifying top ten predictors of type 2 diabetes through machine learning analysis of UK Biobank data. Sci. Rep. 14, 2102 (2024).

Srivastava, J. N., Zacks, S., Sen, P. K. Journal of statistical planning and inference. Encycl. Stat. Sci. 6 (2004).

Vens, C., Struyf, J., Schietgat, L., Deroski, S. & Blockeel, H. Decision trees for hierarchical multi-label classification. Mach. Learn. 73, 185–214 (2008).

Bohlen, L., Rosenberger, J., Zschech, P., Kraus, M. Leveraging interpretable machine learning in intensive care. Ann. Oper. Res. 1–40 (2024).

Srinivasan, K. et al. Analyzing classification and feature selection strategies for diabetes prediction across diverse diabetes datasets. Front. Artif. Intell. 7, 1421751 (2024).

Foody, G. M. Impacts of sample design for validation data on the accuracy of feedforward neural network classification. Appl. Sci. 7, 888 (2017).

Langer, S. Approximating smooth functions by deep neural networks with sigmoid activation function. J. Multivar. Anal. 182, 104696 (2021).

Khan, H. M. R., Mende, S., Rafiq, A., Gabbidon, K. & Reddy, P. H. Methods needed to measure predictive accuracy: A study of diabetic patients. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1046–1053 (1863).

Anwar, A. et al. Correlation of blood urea and creatinine levels with thiamin levels in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients. Cureus 16, e57022 (2024).

Sherwani, S. I., Khan, H. A., Ekhzaimy, A., Masood, A. & Sakharkar, M. K. Significance of HbA1c test in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic patients. Biomark. Insights 11, S38440 (2016).

Schofield, J. D., Liu, Y., Rao-Balakrishna, P., Malik, R. A. & Soran, H. Diabetes dyslipidemia. Diabetes Therapy 7, 203–219 (2016).

Vekic, J., Zeljkovic, A., Stefanovic, A., Jelic-Ivanovic, Z. & Spasojevic-Kalimanovska, V. Obesity and dyslipidemia. Metabolism 92, 71–81 (2019).

Wazir, M. et al. Lipid disorders and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive analysis of current perspectives. Cureus 15, e51395 (2023).

Feingold, K. R. Lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 51, 437–458 (2022).

Chiesa, S. T. & Charakida, M. High-density lipoprotein function and dysfunction in health and disease. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 33, 207–219 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IZS, Conceptualization, Literature and datasets search, writing of first draft and original manuscript BSK, Conceptualization, Literature search, writing of first draft and original manuscript BI, Conceptualization, Literature search, writing of first draft and original manuscript MI, Conceptualization, Literature search, writing of first draft and original manuscript HAH, Conceptualization, Literature search, writing of first draft and original manuscript UMG, Conceptualization, Literature search, writing of first draft and original manuscript AGU, Software, data analysis, Validation, Literature search, editing, writing of the final manuscript AU, Data analysis and statistics, writing of first draft and original manuscript SIA, Data analysis, Project administration, validation, Proof reading and editing, writing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures conducted in this study adhered strictly to applicable guidelines and regulations, following the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol and methodology were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Experiments at the Specialized Center for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital. Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians prior to their involvement in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadiq, I.Z., Katsayal, B.S., Ibrahim, B. et al. Data-driven diabetes mellitus prediction and management: a comparative evaluation of decision tree classifier and artificial neural network models along with statistical analysis. Sci Rep 15, 19339 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03718-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03718-w