Abstract

This paper assesses the presentation of Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), Ridge Regression (RR), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) models in improving the photocatalytic destruction of antibiotic utilizing a UV/ZrO₂/NaOCl system. The GBR model indicated the strength of exhibited precision, with high R² and Explained Variance Score (EVS) esteems, however gave indications of overfitting. Remarkably, the RR model obtained had many significant values and the model had a high data fitness with an R² of 0.81; however, error bars were observed in some areas that could be optimized by fine-tuning. Feature significance examination indicated that X2, X1, and X5 fundamentally affected the model’s performance. At last, PSO was instrumental in finding the ideal limit mix to support removal performance. Altogether the presented models help to improve the photocatalytic degradation process and provide useful tools for further investigation in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic compounds, especially pharmaceutical substances, are emerging pollutants increasingly detected in water resources due to discharges from domestic wastewater, hospitals, and pharmaceutical industries. The compounds manage to stay in the environment as they both help create antimicrobial resistance and create significant health issues for aquatic life and people. Antibiotics represent a primary group of pharmaceutical contaminants which typically reach water systems through wastewater discharges and agricultural drainage. Their presence in aquatic environments can disrupt microbial communities, promote antibiotic resistance, and pose long-term ecological and health concerns1,2,3,4. As a broadly utilized anti-infection, tetracycline is exceptionally compelling in treating human and animal diseases. Because of minimal expense, simple accessibility, and practically widespread utilization in medication and mammalian, it is an exceptionally consumed anti-infection. The major impacts on the ecosystems include; antibiotic resistance and toxicity to aquatic life, impact on the functionality of aquatic ecosystems, and pollution of the soil content causing a decline in agricultural value5. Tetracyclines are known to form and promote the distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in microorganisms hindering their transfer to other bacteria with the result being drug resistance6. Antibiotic medication are additionally deadly to most sea-going living and concentrations as low as 0.5 µg/L repress the development and fruitfulness of these creatures. Besides, the presence of antibiotic medication in biological systems can upset the environmental equilibrium. There is potential for chemical contamination of agricultural soils due to the build-up of tetracycline realized through animal feces and sewage7. Tetracycline is released into the environment from hospitals and municipal wastewater discharge, livestock and agriculture practices, animal manure and sewage sludge, contaminated agricultural water, and usage of tetracycline in pharmaceutical industries8. This pollutant is relatively easy to prove present in water sources since the treatment plants cannot flush it out and its existence poses a threat of endangering the health of a particular community9. To prevent the proliferation of antibiotic resistant-gen, further toxicity of tetracycline on ecosystems, as well as the flow-through productivity of natural and prosthetic human ciliated tissues, the inhibitor needs to be eliminated from the environment. This can be achieved if one employs high-end treatment technologies, improved usage of antibiotics, and effective control of pollution outlets. Other features that make tetracycline different from other drugs include high chemical stability and non-degradable in the environment, first generation where antibiotic bacterial resistance is developed quickly has its specificity to toxic to aquatic life, commonly used in agricultural and animal feeding systems, resistant to some treatment processes and having impacts on changes in soil microbiology; persistency in the environment and deteriorating water and soil quality10. It remains that tetracycline is non-biodegradable, is characterized by a very slow half-life, and becomes a bioactive pollutant in the continuation of the sedimentation further and in the soil and water. Thus, being used in production, veterinary, and agricultural sectors, this antibiotic is easily introduced to the food chain being a major threat to health and the environment11.

Light-based catalytic processes demonstrate essential roles in water degrading organic compounds while using semiconductor catalysts under light exposure.Through these processes hydroxyl radicals transform complex persistent pollutants into harmless end products which include both CO₂ and water while showing great potential for resisting pharmaceuticals alongside other trace organic contaminants that do not respond well to conventional treatment methods. Photocatalysis is considered an eco-friendly and efficient approach for advanced water purification12,13,14,15. Tetracycline expulsion is done utilizing UV/ZrO2/NaOCl handle since it has a few preferences over other forms. The combination of UV radiation, ZrO2 (zirconium dioxide), and NaOCl (sodium hypochlorite) gives synergistic impacts that improve the productivity of tetracycline expulsion. UV radiation enacts ZrO2, advancing the generation of receptive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (O2•−), which are competent of breaking down the complex structure of tetracycline. ZrO2, as a semiconductor with solid photocatalytic properties, produces electron-hole sets beneath UV introduction, driving to the generation of dynamic oxygen species that viably corrupt tetracycline. Moreover, NaOCl, as a solid oxidizing operator, quickens the oxidation handle by creating chlorine radicals, assist encouraging tetracycline debasement. Thus, the found difference between the present and other processes is that the formation of by-products in the UV/ZrO2/NaOCl system is lower, while other advanced oxidation processes can produce toxic by-products, this system does not, which is why it is safer for the environment. Moreover, the review showed that ZrO2 is chemically steady; hence, it may be utilized in a few cycles. Sodium hypochlorite is also very easy to apply, it is cheap and this makes the process cheaper in most cases. UV/ZrO2/NaOCl is efficient for the removal of tetracycline from the water due to high efficiency and low production of toxic byproducts thus low impact on the environment16,17,18,19.

Employing Artificial Intelligence (AI) methods such as; GBR, RR, and PSO in the analysis and optimization of tetracycline removal employing the UV/ZrO2/NaOCl system presents several important benefits than the other optimization such as RSM20,21. These artificial intelligence based approaches are important in overseeing intricacy and information changeability that outcomes from varieties in the properties of tests and, consequently, lead to exceptionally precise forecasts and streamlining of how antibiotic medication is eliminated from tests22,23. GBR is a robust ensemble learning method for learning second-order polynomial regression models of interactions of the independent variables in predicting the removal efficiency of tetracycline24. GBR is particularly useful when the connection of variables like UV, ZrO2, and NaOCl are non-straight; features, which are not easily depictable utilizing statistical procedures. GBR can improve prediction accuracy by changing multiple weak models into a strong one, offering better generalization to unseen data and more precise estimates of tetracycline removal. Another type of regression, Ridge Regression, is used where there is multicollinearity and overfitting of the data. It introduces a penalty term to the model, which prevents overfitting and enhances the robustness of the regression model, especially when the dataset contains correlated variables. Ridge Regression is beneficial in determining factors influencing tetracycline removal efficiency and can provide improved reliability of predictions25. PSO is an optimization method that can proficiently look for ideal mixes of boundaries (e.g., UV power, ZrO2, and NaOCl) that amplify antibiotic medication removal while limiting expenses and by-products26. PSO is able to search the multidimensional solution space and arrive at the best set of parameters in comparison to the time-consuming grid search27. PSO is able to have a better capability to avoid local optima because it covers a larger area of solutions searching space to ensure global optima is arrived at. AI coupled methods make up an optimum solution for the tetracycline degradation process. GBR and RR offer exact displaying and expectation abilities, while PSO works to find the process’s optimal parameters. By utilizing these procedures the researchers can optimize the performance of the UV/ZrO2/NaOCl system in addition limit the expense of the examination and time accordingly making the cycle more proficient and nearer to certifiable circumstances.

This research creates its main advancement through artificial intelligence-driven optimization of tetracycline photocatalytic destruction using optimized UV/ZrO2/NaOCl reaction protocols. The study adopts Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) as a complex AI model through the use of Ridge Regression and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to evaluate data and enhance process parameter optimization resulting in better tetracycline removal. Advanced intelligence tools when merged with the photocatalytic system tend to enhance the prediction accuracy of complex nonlinear parameter models (UV intensity, ZrO2 concentration, NaOCl dose) alongside efficiency measurements. This type of work predicts that improvements to basic process parameters including UV intensity, ZrO2 concentration as well as NaOCl dose may be found by employing the PSO technique while seeking to explore the best reaction paths. PSO expands its search region past grid search techniques thus enabling researchers to locate optimal results with efficiency and accuracy. The study uses AI methods to enhance the UV/ZrO2/NaOCl system as a tetracycline removal method and simultaneously decreases operational expenses and experimental durations. Artificial intelligence systems through their optimized reaction paths generate improved operational performance for practical use. These techniques can be most effective applied for the general removal of pollutants, and in the liquid phase such as in water treatment systems particularly at the industrial levels, including water contaminated by sewage, etc. The main innovation through this research exists in unifying artificial intelligence with photocatalytic processes while optimizing parameters which leads to better performance at lower price points and improves real-world system applicability.

Materials and methods

Material

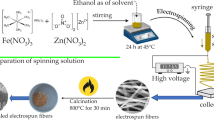

In this study, high purity Tetracycline (99%), Sodium hypochlorite (98%), and zirconium dioxide (98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich to conduct the experiments as reported in this research with high reliability and reproduction ability. The UV-Vis spectrophotometer assessed Tetracycline photocatalytic breakdown through a breakdown evaluation to determine degradation efficiency. To achieve uniform and standardized samples, an ultrasonic cleaner (GT SONIC-D27) was utilized, which offers 500 W of ultrasonic and heating power and operates at a frequency of 40 kHz (serial number GOD119 A7 F002).It was important to ensure adequate dispersion of the reactants and to do this the use of this device, made in China was essential. However, constant pH measurements and adjustments were taken using far more precise, made in Germany, pH/COND 720 INOLAB with serial No 07340498.These measures ensured the accuracy and reliability of the data collected throughout the study.

Experimental setup and photocatalytic process

The photocatalytic experiments were performed at batch type reactor model utilizing a locally fabricated polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) photoreactor that provides the best condition in terms of exposing the system to light and chemical interactions within the reaction mixture. The reactor installed a 6 W ultraviolet C (UVC) lamp (Philips) as the primary source of UV Radiation to trigger the photocatalytic processes. A water circulation system functioned to stabilize temperature while controlling lamp heat output from the entire testing duration. The UVC lamp was placed horizontally with its axis bisecting the plane of the reactor. The lamp faced the reactor wall in an symmetrical position at 1 cm distance to achieve uniform radiation of the reaction mixture which was essential for activated photocatalyst response and effective reactant interaction. The experiments required continuous mixing through magnetic stirring because it allowed dispersed photocatalyst particles to stay uniformly distributed along with reactants for achieving reliable experimental results. The samples were taken at regular time intervals from the reactor at convenient time intervals and were subjected to the following treatments. The particulate photocatalysts were first sedimented by centrifuging the samples at 3000 rpm. Research analysts evaluated photocatalytic degradation performance by looking into clear supernatant solutions to develop exact understandings of system reactions and processes.

Experimental setup and methodology

Gradient boosting regression (GBR)

Steps for implementing GBR28,29:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing.

Data Cleaning: The next step with the examinations of the results obtained in previous step is to realize, whether there are any empty values in the tables, and which of them have to be deleted or which of them have to be supplemented with another value.

Standardization or Normalization: If necessary, normalize or standardize the data so that all features are on a similar scale.

Encoding Categorical Variables: If there exist categorical variables they should be preprocessed like one hot encoding to make them take numeric form.

Step 2: Splitting Data into Training and Testing Sets.

Split the dataset into two parts: training data (used to teach/training of the model) and testing data {(used to assess the model). It is common to find the training data as 70% and testing data as 30% respectively.

Step 3: Building the GBR Model.

Selecting Hyperparameters: Hypers as the number of trees, the depth of the trees, learning rate and minimum samples split must therefore be selected.

Training of the model: The decision trees in Gradient Boosting are constructed one-by-one where each tree seeks to minimize the loss function on the training data.

Step 4: Model Evaluation.

Once the model is trained, explore performance of the model using testing data is as follows: Common performance measures includes : (R-squared) R²; Mean Squared Error (MSE); and/or Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

Step 5: Model Improvement.

As a second step if the model does not give desired accuracy, then using Cross-Validation for getting the best hyperparameters. The best parameters can be obtained using Grid Search or Random Search. However, switching of a value in n_estimators or even raising learning_rate may be used to enhance the model.

Steps for implementing ridge Regression30

Step 1: Data Preprocessing.

Data Cleaning: clean the dataset: As done in the previous steps, standardize the data as GBR is sensitive to scaling of features.

Step 2: Split data into training and testing data set Partition the data into groups of learning set and validation set as well.

Step 3: Building the RR Model.

Ridge Regression is a linear model which extend of is resistant to overfitting, a small value of a parameter referred to as alpha or lambda.

This model assumes a linear relationship between input variables and the output, and adds a penalty to the loss function to reduce model complexity.

Step 4: Choosing the Regularization Parameter (α).

The α parameter controls the amount of regularization applied.In the first case if α is larger the value of the model then the model is less complicated and if the value is smaller then the model is over determined.

To select the ideal value of, α, perform Cross-Validation.

Step 5: Model Evaluation.

It is worthwhile to assess the model value by applying some figures like R², MSE, RMSE and etc.

Step 6: Model Optimization.

If necessary, use Grid Search to optimize the α parameter.

Also, it is necessary to think about Polynomial Features for increasing the model’s degree of complexity if necessary.

Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

Steps for implementing PSO31:

Step 1: Define the Objective Function.

For PSO, define an objective function, typically an error function such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) or Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), which should be minimized.

One must look to identify the least error neural network model parameters.

Step 2: Set the PSO Parameters.

Number of Particles: Choose the number of particles in the swarm. Typically, this is between 20 and 50 particles.

Cognitive and Social Weights: These parameters influence the movement of particles. The cognitive weight (c1) reflects the importance of individual best positions, while the social weight (c2) reflects the importance of the global best position.

Maximum Iterations: Set the maximum number of iterations for the optimization process.

Maximum Velocity: The maximum speed at which particles can move through the solution space.

Step 3: Perform PSO Optimization.

The PSO algorithm starts with particles moving through the search space. Every particle has position and velocity and it updates its flying towards the local best known position and global best known position. In each version of the algorithm, the particles move to a new position depending on personal and learned knowledge of other particles.

Step 4: Model Evaluation.

Once the optimization is complete, assess the model utilising the optimum variables employ measurement such us RMSE or R².

Step 5: Results Analysis.

Analyze the results and check if the model has reached an optimal state. If necessary, fine-tune the PSO parameters and re-optimize the model.

The PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization) model applies its methodology to optimize model parameters that specifically refer to neural networks and alternative optimization tasks.The procedure for determining the optimal limit mix through PSO can be expanded to understand its real-world application:

Methodology in PSO model

1. Objective Function Definition: In PSO, the first step is to define the objective function that needs to be minimized.MSE and RMSE serve as common error functions for regression or classification operations where error reduction between model predictions and real data points stands as the main goal.The intended goal aims at reducing any discrepancies between model forecast predictions and real-world measurements using the objective function to direct particle solution paths to their optimal parameter set.

2. PSO Parameters Setting: Several key parameters are set to control the optimization process:

-

Number of Particles: An interrelated grouping of between 20 and 50 minimal particles serves as potential solutions in the optimization process.Each particle has a position (representing a set of model parameters) and a velocity (indicating the direction of movement).

-

Two imposed weights within PSO determine particle vulnerability to personal best position by c1 (cognitive) while other swarm positions have weighting factor c2 (social).These parameters are crucial in controlling how the swarm explores the solution space.

-

Maximum Iterations: This defines how many iterations the PSO will run to optimize the parameters.More computational resources are needed when using more iterations in the optimization process while increased iterations boost the potential for attaining an optimal solution.

-

Maximum Velocity: The set limit controls the movement speed of particles to stop them from missing optimal solutions and enables a smooth optimization process with proper convergence.

3. Performing PSO Optimization:

-

Movement and Updates: Each particle within the optimization process follows two position update practices.It uses its local pBest position as well as the global gBest position identified by the entire swarm.The updating process for particle velocity occurs through cognitive and social weights to determine the movement direction and speed of each particle.The system runs loops until the defined operational conditions become satisfied at the same time it searches for optimal solutions through improved positions.Each particle is seeking to find the combination of parameters that minimizes the error function (MSE, RMSE, etc.).

The PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization) model applies its methodology to optimize model parameters that specifically refer to neural networks and alternative optimization tasks.The procedure for determining the optimal limit mix through PSO can be expanded to understand its real-world application:

Methodology in PSO Model

-

1.

Objective Function Definition: In PSO, the first step is to define the objective function that needs to be minimized.MSE and RMSE serve as common error functions for regression or classification operations where error reduction between model predictions and real data points stands as the main goal.The intended goal aims at reducing any discrepancies between model forecast predictions and real-world measurements using the objective function to direct particle solution paths to their optimal parameter set.

-

2.

PSO Parameters Setting: Several key parameters are set to control the optimization process:

-

Number of Particles: An interrelated grouping of between 20 and 50 minimal particles serves as potential solutions in the optimization process.Each particle has a position (representing a set of model parameters) and a velocity (indicating the direction of movement).

-

Two imposed weights within PSO determine particle vulnerability to personal best position by c1 (cognitive) while other swarm positions have weighting factor c2 (social).These parameters are crucial in controlling how the swarm explores the solution space.

-

Maximum Iterations: This defines how many iterations the PSO will run to optimize the parameters.More computational resources are needed when using more iterations in the optimization process while increased iterations boost the potential for attaining an optimal solution.

-

Maximum Velocity: The set limit controls the movement speed of particles to stop them from missing optimal solutions and enables a smooth optimization process with proper convergence.

3. Performing PSO Optimization:

-

Movement and Updates: Each particle within the optimization process follows two position update practices.It uses its local pBest position as well as the global gBest position identified by the entire swarm.The updating process for particle velocity occurs through cognitive and social weights to determine the movement direction and speed of each particle.The system runs loops until the defined operational conditions become satisfied at the same time it searches for optimal solutions through improved positions.Each particle is seeking to find the combination of parameters that minimizes the error function (MSE, RMSE, etc.).

4. Model Evaluation:

-

The PSO algorithm terminates with the optimal parameters that allow the model to be evaluated through selected error metrics.The assessment of model optimality in this scenario utilizes either RMSE or R² as common error metrics.

-

oThe PSO algorithm functions to discover optimum parameter combinations which optimize model performance during the evaluation step.The chosen parameters produce reliable and accurate results for the model.

5.Results Analysis:

-

a.

The model evaluation produces outcome analysis to check the existing model against the intended perfect design.If the performance is not satisfactory, the PSO parameters (such as the cognitive/social weights, number of particles, or maximum iterations) may be adjusted and the process repeated.

-

b.

Practitioners can achieve optimal model types by adjusting accuracy-determining model parameters.This methodology provides them this capability.Determining the Optimal Limit Mix.

A model’s best efficiency and accuracy result from the most optimal combination of parameters which compose the limit mix.

In the context of PSO:

-

Optimization of Parameters: During the PSO algorithm multiple parameter value combinations are tested to find the minimal error function output where “optimal limit mix” represents the best parameter setting.

-

Exploration vs. Exploitation: Through the cognitive and social components of the PSO, particles explore the solution space (finding new, potentially better solutions) while exploiting their existing best-known solutions.The achievement of an optimal solution requires activities of exploration to match activities of exploitation at equal levels.

Practical Implications

The practical implications of using PSO for determining the optimal limit mix in models are significant:

-

Efficiency: PSO is an efficient optimization method that can significantly reduce the time and computational cost of finding optimal parameters compared to manual or grid search methods.

-

Global Search: PSO prevents local minima through swarm social interaction that maintains a global search which results in stronger potential solutions.

-

Adaptability: The PSO model demonstrates great flexibility when solving optimization problems which include parameter optimization for machine learning techniques and all other optimization requirements.

-

Scalability: The algorithm demonstrates scalability that enables its application to models which contain both several parameters and complex functional components.

This concludes that PSO model optimization operates by permitting the swarm’s repeated search for ideal parameter bundles.An error function (RMSE or MSE) forms the basis for determining the best limit mix through minimization processes which require analysis of results for assessing model performance.Through these methods, practical applications emerge in accuracy improvement together with reduced computational time alongside adaptable solutions for various optimization problems.

Analysis of the three models in terms of computational efficiency and ease of implementation

The linear design of Ridge Regression allows it to reach maximum computational speed which surpasses both Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). GBR requires extensive computation time because its algorithm performs successive decision tree constructions along with updates on large datasets. PSO represents the most time- and resource-intensive simulation model from among these three since it conducts population-based optimization through parameter space exploration. Ridge Regression is the simplest method for implementation since administrators need to adjust just one parameter (α) and this process can be executed through Scikit-learn libraries. Because GBR provides strong library support through XGBoost or LightGBM users can implement it easily by adjusting select essential hyperparameters. The implementation of PSO poses the greatest difficulty because users need to define an objective function alongside the search space and properly adjust various parameters including the number of particles as well as velocity and cognitive/social weights. Understanding evolutionary algorithms at a solid level is needed for this procedure. The selection of Ridge Regression happens when simplicity together with speed take precedence yet GBR delivers better accuracy with complex modeling factors while PSO provides optimal parameter adjustment in advanced nonlinear models at a higher computational cost.

Model criteria table

-

1.

GBR Model (Gradient Boosting Regressor):

-

Training Data:

-

Features (Independent Variables): X1 (pH), X2 (ZrO₂ amount), X3 (NaOCl amount), X4 (Tetracycline concentration), X5 (Contact time).

-

Target Variable (Dependent Variable): Removal (%) of Tetracycline.

-

-

Testing Data:

-

Features (Independent Variables): Same as training data (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5).

-

Target Variable (Dependent Variable): Removal (%) of Tetracycline.

-

-

Model Performance Metrics:

-

Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), R² Score.

-

-

-

2.

Ridge Regression Model:

-

Training Data:

-

Features (Independent Variables): X1 (pH), X2 (ZrO₂ amount), X3 (NaOCl amount), X4 (Tetracycline concentration), X5 (Contact time).

-

Target Variable (Dependent Variable): Removal (%) of Tetracycline.

-

-

Testing Data:

-

Features (Independent Variables): Same as training data (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5).

-

Target Variable (Dependent Variable): Removal (%) of Tetracycline.

-

-

Model Performance Metrics:

-

Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), R² Score.

-

-

-

3.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Model:

-

Optimization Objective:

-

The PSO algorithm was used to optimize the photocatalytic degradation process by adjusting the values of the independent variables (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5) to maximize the removal efficiency.

-

-

Features (Independent Variables):

-

X1 (pH), X2 (ZrO₂ amount), X3 (NaOCl amount), X4 (Tetracycline concentration), X5 (Contact time).

-

-

Objective (Dependent Variable):

-

The objective function was used to calculate the “Removal (%)” based on the particle’s position in the search space. The optimal solution was achieved when the particle positions yielded the maximum removal efficiency.

-

-

Optimization Metrics:

-

The best solution (optimal removal efficiency) was found using the PSO model through the fitness function, which considered all five variables. The optimal removal value and fitness curves were used to evaluate convergence and performance.

-

-

Results and discussion

GBR model

Performance evaluation of a gradient boosting regression (GBR) model on training and testing datasets

As shown in the presented chart (Fig. 1), there are actual and predicted values of the GBR model for both training and testing datasets, as well as such parameters that can be used to evaluate the success of the model as accuracy, mean absolute error, root mean square error, mean absolute percentage error, and in R-squared score. Evaluation metrics indicate successful performance because the training dataset reflects excellent value prediction between actual and predicted lines proving the model understands training data patterns. Nonetheless, from the information created by the framework in the testing dataset, while the model’s performance remains high, its accuracy is slightly lower when compared to its training dataset accuracy, this implies that a little overtraining might reduce the generalization of the model for any new data coming. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in the training dataset is 1.013 suggesting an average prejudice of 1.013 units while that of the testing is 0.02. Similarly, the MSE decreases notably from 2.78 in the training dataset to 0.0008 in the testing dataset, further highlighting better performance. From the training dataset, the RMSE was 1.6690 and in the testing dataset, it was 0.028, which proves that the overall error was minimized. The R² value in the training dataset reaches a strong 0.981 indicating effective data variability explanation but testing data reaches a perfect 1.0 which might indicate overfitting32. The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) reduces from 1.37% in the training dataset to 0.03% in the testing dataset, showing a significant improvement in prediction accuracy as a percentage error. The EVS measurement comparable to R² produces high values in both datasets which verifies that the model delivers excellent data variance explanation. Overall, the model performs exceptionally well in the training dataset, accurately learning its patterns, and shows strong performance in the testing dataset, though the perfect R² value of 1 might indicate potential overfitting22,33.

The Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) model shows outstanding results in this research yet Fig. 1 together with the performance report indicates signs of overfitting in the evaluations which received thorough attention. The practice of learning training data in extent causes models to lose their capacity for data generalization. In this research, despite the precise results on the test data, evidence of overfitting has been observed. The substantial variance between accuracy measurements on training and test data likely demonstrates overfitting tendencies which produce a 0.981 R² score during training. In contrast, the R² value for the test data reaches a perfect 1.0, which is theoretically unusual. The model likely extracted random data attributes leading to perfect accuracy because of overfitting. At the same time the cross-validation plot (Fig. S1 in the supporting information file) indicates that overfitting is taking place. The MSE value in the second fold is about 12.3, but it increases to 93.9 in the fifth fold. Across folds there exists high variability suggesting the model is unstable during an overfitting process which selects portions of input data. Another point is that in the test data, the MAE, MSE, and RMSE values have decreased unusually.For instance, the MSE decreased from 2.78 in training to just 0.0008 in testing. Under typical modeling conditions such excessive reduction in error rate is uncommon and indicates overfitting of the data. The default execution of GBR with high tree depth together with lacking specific constraints leads to a higher probability of overfitting the data. Inappropriate modifications of n_estimators, max_depth and learning_rate increase the overfitting risk according to this study. Early stopping with subsampling and parameter cross-validation should serve as protective measures according to the recommendation. Detailed examination of the model proves its remarkable success yet detects minor overfitting behavior as a model property. The model reaches stability and generalizability enhancement when employing proper modifications together with complexity control methods34,35.

Residual analysis for evaluating model performance in training and testing phases

Figure 2 shows the residual distribution as differences between predicted and actual values for training and testing datasets through box plots. Therefore, the analysis of such two plots will contribute the proper understanding of the results of the model between training and testing phases. The box plot sample residuals of the training data is more extensive than those of the testing data; this suggests that the model fits testing data with less error than training data. On the other hand, you get a box plot of the testing dataset depicting the residuals showing slightly more concentrated and slightly less spread meaning that the model did a rather better and consistent job of predictions for the testing dataset. The training dataset in the box plot shows slightly negative skewness because the tails point towards negative values indicating that model predictions exceed actual outcomes. Greater negative skewness in the testing dataset suggests that this tendency to overestimate is more pronounced in this phase. Indeed, residual distribution in the training dataset is slightly leptokurtic, or the tails are heavier than normal distribution. The testing dataset residual distribution appears platykurtic because it has less pronounced tails than a traditional normal distribution. The model performs well with the training data but depends heavily on training dataset patterns which produces higher prediction errors during new data applications. On the other hand, the model tests better on the testing dataset which gives a better residuals curve that shows better generalization to unseen data sets but it also indicates a more negatively skewed distribution which also shows the overestimation capability of the model to some extent. In any case, these results seem to paint the picture that in general, the model does better for the boxplot comparison of the testing dataset. However, the negative skews confirmed in both sets establish that there is a likely possibility that the model failed to predict some values in the best way33,36,37.

Comprehensive evaluation of model performance on training and testing datasets

Table S1 in the supporting information file presents a clear contrast of the presented model for training and testing datasets. The comparison of the strive evaluation with assorted statistical measures gives profound insight into the model’s ability, the model’s weakness, and the ability of the model to generalize the fresh data. The model predicts almost perfectly throughout the training set due to the residuals having a mean of 0.016. In the testing set the mean of the residuals is slightly negative, which implies that on average the model slightly underpredicts the values. The median of the training set is also small, which also confirms that most of the scores are located in the vicinity of the truth, and the median of the test set, which like the mean is slightly negative, similar to before, suggests a tendency to underestimate. The wide distribution of training set residuals along with varied mean squared error shows higher variability but testing set residuals have lower standard deviation indicating more stable prediction errors. From the training data set, the range of residuals is much broader, meaning that at least there is a possibility of coming up with some predictions with very large predicted errors, while for the testing data set the range of residuals is much narrower implying approximate equal predicted errors. The first and third quartiles and interquartile range (IQR) values further suggest that the residuals in the testing set have much less spread compared to the training set. For the case of skewness, the coefficient is slightly positive for the training set meaning the tail of the residuals distribution for the training set is more towards high positive residuals values while for the testing set the coefficient is slightly negative meaning the residuals distribution tail for the testing set is more towards negative low true values than they are estimated to be by the model. The kurtosis of the training set is greater than kurtosis of a normal distribution; i.e., the residual has more outliers than the normal distribution. The kurtosis of the testing set is littler than the kurtosis of a ordinary conveyance; i.e., the leftover has less exceptions than the typical conveyance. Measurements such as MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R² all demonstrate that the demonstrate performs superior on the testing set. The lower values of MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE within the testing set recommend less forecast mistakes. Moreover, the calculated R² esteem which is very close to one within the testing set can cruel that a critical portion of the fluctuation of the testing set information is clarified by the show. The comparison of the two sets shows that the model seems overfitting on the training set which means that this model has learned random patterns within the training data and fails to generalize previous experience in the testing set. The model delivers steady test results with a small pattern of deviation observed in prediction errors. The model tends to underestimate the true values in the testing set38,39.

Analysis of residuals distribution and model performance in training and testing sets

In Fig. 3, on the right of the horizontal axis, there is a label that shows the word residuals which represents the residual figures which is the difference between the actual figures and the forecasted figures. On the vertical axis each point is an observation with closeness of error magnitude. Zero and positive values indicate the model overestimated the figure but negative values show the model underestimated the figure. The vertical axis (Density) gives the probability density. With this distribution, it tell how many observations have this residual value for each point on the horizontal axis. In other words, the higher the graph at a point, the more observations have residuals close to that value. The position of the peak in the plot shows where most of the residuals are concentrated. Close to the zero value entails that the actual value yielded by the model is close to the actual value most of the time, as the top of the chart nearly touches the horizontal axis at 0. The breath of the peak reveals the spread of residuals. The spread of residual data indicates model inaccuracy when the peak distribution is broad. In the training set, the high spread of residuals (wide peak) indicates that the model did not fit the data well and the prediction errors are highly varied. A slight positive skew indicates the model tends to overestimate the values slightly. They also indicated that positive kurtosis implies that the residual distribution is likely to have fatter tails than the normal distribution indicating that some of the observations have relatively large errors. In the testing set, the low spread of residuals (narrow peak) shows the model performed much better on this set, with more stable prediction errors. A negative skew indicates the model tends to underestimate the values. Negative kurtosis suggests that the residual distribution is closer to a normal distribution. In the training set, the residues are highly scattered which means prediction errors include many variances. Some of the predictions are highly off. The testing set shows small variation in the residues. Hence the model was more accurate in predicting the results of this set. The probability distribution train has a slightly higher median than the middle of the distribution while the test has a slightly lower median the distribution of residuals is shifted positively, and the model tends to overestimate the values. Distribution of residuals is shifted negatively and the model tends to underestimate the values. This shows that the residual distribution in the training set has higher kurtosis than that of the normal distribution which implies that there are outliers in the data. The kurtosis of the testing set is the negative value showing that its residual distribution is less than that of the normal distribution, meaning that it is less outlier-rich. In both residual distributions, the mean is very close to zero showing that the model was getting very close correct values. The median values remain close to zero between both datasets as most predictions center around actual values. A higher standard deviation in the training set and lower in the testing set further indicates a greater error spread in the training set. The wide spread of residuals in the training set suggests the possibility of overfitting. This means the model has learned the random patterns in the training data, causing difficulty in generalizing to new data (testing set). The residuals in the testing set show much less spread, indicating the model performed more stably on this set. The model tends to underestimate actual values in the testing set40.

Evaluating machine learning model performance using the cumulative gain chart

Based on the presented material, a Cumulative Gain chart (Fig. S2 in the supporting information file) is a good instrument to analyze the results of machine learning models applied for classification or ranking concerns with the target to solve regression problems. The related results has been presented in the supporting information file.

Evaluating and tuning model parameters using the validation curve

It is one of the most effective graphs reflecting model assessment and its parameters optimization together with changes in the performance of a certain model with regard to training and validation data upon alterations of a definite parameter (Fig. 4). Here, each bar graph value on the Y axis gives the variations in the parameter n_estimators which refers to the total number of decision trees in a gradient boosting model. The number of decision trees used in the gradient boosting model is on the X-axis. The higher this number is, the more complex the model which is built. Labelled across the Y-axis we find values characterising the mean squared error by means of which the efficiency of a regression model is sometime quantified. Model performance improves when the value decreases because it shows lower prediction errors. The blue line represents the over-training error measure that the developed model provides over the training data set. The training error displays a pattern of reduction as you escalate the number of decision trees. This is so since as the model increases in complexity it retains more and more of the information present in the training data. The test measures how effectively the model applies its knowledge to distinct unviewed information. The blue and red colour shaded regions therefore show the range of errors, that is, how far we can be from the average error values. At the start of the chart, as the number of decision trees increases, both the training error and validation error decrease. However after some level the validation error starts increasing and training error starts decreasing. An overfit model causes this problem by matching the training data excessively which makes it unable to properly extend to new data. At the beginning of the chart, especially with a low number of decision trees, we may observe high training and validation errors. This demonstrates underfitting, where the show is as well basic to memorize the patterns within the information. The leading point to select the number of choice trees is the point at which the approval mistake is at its least. This point speaks to the leading adjust between show complexity and its capacity to generalize. Based on the given chart, we are able conclude that at first, as the number of choice trees increments, the show performs way better. Be that as it may, after coming to a certain point, overfitting happens, and the model’s execution on modern information decreases. The ideal number of choice trees is the point where the approval mistake is minimized. At this point, the model has a good ability to generalize to new data and avoids overfitting23,41.

Evaluating model performance through learning curves and model performance and overfitting analysis based on training set size and mean squared error (MSE)

A learning curve (Fig. S3 in the supporting information file) is a powerful instrument for the evaluation of the model’s performance on a given data set. The related results were presented in the supporting information file.

Examining the impact of various features on predicting the dependent variable using the gradient boosting regressor model

Table S2 found in the supporting information file displays the results from using Gradient Boosting Regressor models on a dataset. The models find widespread application for both regression and classification work and show excellent performance outcomes. The sections of the table incorporate Feature, which shows the name of each information component of the model (in this model, there are five highlights, X1 to X5), MAE (Mean Absolute Error), addressing the typical outright contrast between the anticipated qualities by the model and the genuine qualities (the more modest this worth, the more exact the model), MSE (Mean Squared Error), which is the normal of the squares of the distinctions among predicted and actual qualities, delicate to huge mistakes, RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), characterized as the square base of MSE for simpler understanding, MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), the typical outright rate distinction among anticipated and real qualities, helpful for contrasting models and various scales, R² (R-squared), the coefficient of assurance that demonstrates the amount of the change in the objective variable is made sense of by the model (a worth more like 1 demonstrates better model execution), and EVS (Explained Variance Score), like R², showing how well the model makes sense of the difference in the information. Measurement X2 produces the most significant impact on prediction outcomes based on its lowest MAE, MSE, RMSE and MAPE values combined with the highest R² and EVS results. Conversely, Feature X4 shows the least impact, indicated by its highest error values and lowest R² and EVS scores. Overall, the model’s performance is strong, as reflected in R² and EVS values close to 1, which suggest that the model effectively explains a large portion of the variance in the target variable, together with low MAE, MSE, and RMSE values indicating high accuracy38.

Ridge regression

Evaluation of prediction errors in training and testing phases

The heatmap plot presented in Fig. 5 is an effective means to compare actual and predicted values within the model and check the training/testing error. It displays the error distribution of the model and let one to make a rough evaluation of the performance of the model has X axis to plot the values which have been predicted by the model while a Y axis to plot the target variable’s real or observed values. The X-axis is the forecast of the model while the Y-axis is the actual (true) values of the target variable. Saturation level depends on the absolute error coefficient of actual and estimated values. The training visualization heatmap uses red color which indicates high errors while the testing uses dark blue and light blue indicating high and low errors respectively. The error distribution pattern in the heatmap was observed to be relatively sparse where lower actual values paired with higher predicted values. Flaws shown are higher for lower as well as higher actual values in the testing heatmap, suggesting overtraining is the model, and the model isn’t useful for new data42,43,44.

Assessment of model residuals for training and testing data

The residual scatter plots (Fig. 6) are the values where the merit of the pursuant predictive model is assessed. Residuals are the values obtained by actual observation minus the predicted value as related to a given model. These are located on the y-axis; the actual values of the dependent variable are located on the x-axis. The model evaluation plots demonstrate desirable characteristics of the model while showing the training data average at −0.00. This suggests the model neither overestimates nor underestimates on average. These ‘residuals’ however again can be seen as having a high standard deviation (5.29) thus suggesting that there is considerable inconsistency in some models, despite the small average error. The largest negative and positive errors emerge from the minimum and maximum residual values (−11.41 and 9.41 respectively).The RMSE (5.29) provides measure of the average size (magnitude) of the error and as expected is equal to the standard deviation of the residual since the residual has about a zero mean. For the testing data, the means of residuals are positive (2.48), which indicates the model is a little biased toward overestimation of the real values. The testing data residuals showed less variation than training residuals because their standard deviation amounted to 3.46. To compare, we can see the minimum and maximum residual values which show the range of errors minimum is −26, whereas maximum is 28. The RMSE likewise ends up being 4.26 which is lesser than that of training data. However, the positive mean residual proposes this improvement may be because of predictable misjudgment instead of better speculation. The examination recommends conceivable overfitting, as the model shows a propensity to perform better on training information while battling with inconspicuous information. High residual fluctuation in both datasets demonstrates space for model improvement. The x-hub of these plots is the actual upsides of the reliant variable (removal percentage in our case) and the y-pivot is the residuals of the informational index. Positive residuals demonstrate misjudgment by the model, though bad residuals show misjudgement. The singular focuses on the plot signify the perceptions while the scattering of these focuses offers detail on the circulation of model blunders. In the training scatter plot, the typical residual near zero shows that the model commonly neither misjudges nor underrates. The far reaching of focuses, nonetheless, features critical mistakes now and again. The flat red line at y = 0 fills in as a source of perspective for assessing residual dispersion. In the testing scatter plot, the positive mean residual mirrors a general misjudgment propensity. The focuses are less scattered than in the training plot, recommending more noteworthy consistency in new information expectations. The model performs moderately well on training information however will in general misjudge in testing information. The dispersion of residuals highlights that model can still be improved39,45.

Analysis and evaluation of ridge regression model performance using Bias plot and evaluation metrics

The Bias Plot (Fig. S4 in the supporting information file) is plot/tracing test that is applied to assess the true value of regression models with the help of two true values, enclosed by blue color line, and predicted values by red color line. The X-axis reflects the observation and thus is used for showing the order of data and value changes whereas the Y-axis shows the dependent variable. Views on perfect prediction errors can be assessed by using the horizontal line set at y = 0 as a baseline. The position of the blue and red lines near each other defines how accurate the model is with the nearer lines defining better predictions. Larger gaps between the lines suggest higher errors; a consistently higher red line shows overestimation, while a lower one indicates underestimation. Model improvement occurs when direct or methodical predictors appear between model lines. This is where lines are closer in the plot and is defined as random errors distribution and less noise, while the one that has a large gap or what is referred as systematic error distribution and noise is referred to as non-ideal conditions. Ridge regression frequently applies the Bias Plot to analyze the model’s performance in detail because the proximity of lines reveals the model’s accuracy level while random errors without patterns indicate unbiased results. The distributions of points above and below the lines prove the presence of more errors at some points. MAE of the model is measured at 4.29 which indicates that the error in the model has an average of nearly 4.29 units. The MSE of the model is 28 which means some of the predictions have large errors. RMSE is at 5.29 meaning an average error of about 5.29 units is found. Available data fits well with the model based on the 81% R-Square value which explains variable variance. On balance, the Ridge regression model gives relatively good results concerning accurate predictions indicated by a high R2 value nonetheless there are some discrepancies at a given point of the curve which can be amended after adjusting the various attributes of the model or applying data pre-processing procedures.

Analyzing the impact of alpha on ridge regression performance

Different alpha values that function as complexity management factors appear along the X-axis of Fig. 7. More choice of alpha reduces the model’s complexity and less influenced by the training data set. The y-axis is the average to the squared difference between prediction and dout which is show by MSE. The blue line which represents the training error increases gradually as alpha increases because a high value of alpha leads to the model being more simple so it can’t fit the details on the training data. The red line (testing error) indicates that as alpha increases, the testing error initially decreases due to reduced overfitting. However, if alpha becomes large the model becomes overly simplified, and the testing error is likely to rise. Overfitting happens in the left region because alpha is small which makes the model both complex and dependent on training data. The middle area of alpha values supports the model to detect critical patterns without compromising its simplicity needed to stop overfitting. In the right region where ‘alpha’ is large, the model is an extremely simplified version of the potential complexity held within the parameters of the dataset, resulting in oversimplified issues of underfitting that do not allow for adequate ability to perform on either training or testing data sets. The purpose of this plot is to find the most suitable alpha value that will be used in the model; the alpha that will give the lowest testing error overall. As is observed from the plot, the right alpha value can be easily inferred given by the lowest value of the testing error. Achieving optimal model performance through alpha selection remains essential for obtaining good outcomes because models need balanced complexity between intricate pattern recognition and overfitting prevention. Algorithmatic cross-validation equips professionals to enhance the precision of selecting the alpha value46.

The error bars in Ridge Regression results demonstrate how certain the model can predict its performance results. The vertical error bars appear during model evaluation conducted with cross-validation techniques that generate metrics through repeated calculations. The model overfits when alpha value falls too low since it becomes sensitive to small data variations producing unpredictable results across test sets with wider error measurement bars. Model simplification occurs when alpha value becomes too high leading to poor variable relationship understanding that produces increased error bars. The model stability improvement depends on selecting the best alpha value via grid search or cross-validation because the validation rounds produce R² values ranging between 0.88 and − 0.13. Enhancing model stability requires choosing the optimal alpha value through grid search or cross-validation. At the same time data preprocessing with normalization and outlier removal combined with train dataset expansion will minimize errors and variability. The model produces error bars when it overfits due to complexity or underfits due to oversimplified models yet both issues resolve through appropriate parameter adjustments and enhanced data quality.

Evaluating the performance of the ridge regression model in cross-validation

In the following section, the chart (Fig. S5 in the supporting information file) is demonstrated whereby the Ridge Regression model is tested during the cross-validation step. This chart displays the model’s performance score (here, R-squared or R²) for each of the 10 folds used in cross-validation (The related results were presented in the supporting information file).

The Ridge Regression model shows strong data fitness based on various statistical indicators obtained from error distribution analysis and residual testing and bias comparison and cross-validation testing. The R-squared (R²) value achieved 0.81 indicating the model properly explains 81% of the dependency variable fluctuations (removal percentage). This high R² value is a strong indicator of good fit between the model predictions and the actual observations. A statistical assessment using confidence intervals of the R² value was calculated through 10-fold cross-validation results. To calculate R² values each individual fold produced different results because they trained using separate subsets. The R² average across folds reaches approximately 0.79 while each permutation calculation varies between − 0.13 and 0.88.Negative R² levels indicate the model yielded worse predictions than basic mean forecasting in specific subsets. The fold results demonstrated positive R² figures greater than 0.7 thus demonstrating suitable model functioning throughout. Determination of the uncertainty level regarding cross-validation mean R² value required computing the 95% confidence interval. Since standard deviation across folds measured approximately 0.32 and the analysis used 10 folds the mean R² standard error becomes approximately 0.10. Using this standard error and assuming a normal distribution, the 95% confidence interval for the average R² value is calculated as 0.79 ± 1.96 multiplied by 0.10, resulting in a range from approximately 0.59 to0.99. This interval suggests that, with 95% confidence, the model’s R² falls between 0.59 and 0.99 for unseen data, reinforcing the claim of good predictive performance, although variability between folds reflects sensitivity to the training data. The error-based metrics confirm the conclusions obtained from other metrics. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is around 5.29 for training and 4.26 for testing, which indicates that on average, predictions deviate by about 5 units in training and 4 units in testing. The Mean Absolute Error reaches 4.29 while Mean Squared Error equals 28 indicating moderate prediction error values. The residual distribution demonstrates that the training mean (− 0.00) approaches zero while testing (2.48) shows a positive mean value which indicates a small overestimation bias on unobserved data. The low mean residual shows that additional improvements can be made but large deviations revealed by standard deviations of 5.29 for training and 3.46 for testing warrant attention. Ridge Regression model shows a successful fit to the dataset based on R² with high mean performance and regular confidence interval precision and suitable RMSE and MAE measurements.

Analyzing the effect of feature count on ridge regression performance

The number of features in the process has a definitive impact on the quality of the Ridge Regression model as displayed in Fig. 8. The chart contains two lines: the blue line (training error) shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) on data the model was trained on which means the error made by the model when it predicted target values for the input data it was trained on and also the green line is test error which means Mean Squared Error and gives the heart failure that the model makes predicting the target value of unseen data, not included in training. The plots on the horizontal axis are the number of features used in the model which is augmented into a mesh of functions, and the vertical axis plots the Mean Squared Error, which is a measure of the model’s error, a lower MSE value signifies the better the model is. The blue line is usually concave down since with increased features the learner can model the training set better. The green line declines initially when the number of features is increasing and this indicates better performance but as soon as features cross a certain limit the test error starts to climb. This phenomenon, called overfitting, occurs when the model becomes too closely tailored to the training data, resulting in poorer performance on new, unseen data34.

Understanding feature correlations in ridge regression

The graphical representation of correlation shows how two variables maintain a direct mathematical connection throughout their observing period (Fig. 9). It can be positive when both the variables increase similarly or decrease similarly it is a negative sign when a change in one is quite the opposite of the change in the other one and sign zero shows that there is no correlation between the variables correlation matrix gives the correlation between variables two by two in a tabular form. A correlation matrix on the other hand a two-way matrix that produces the correlation coefficient of each variable with every other variable. The visual system of heatmaps stands as a color-based representation that shows directional and intensity values for correlation matrix data. A heatmap will be used with the dataset for the Ridge Regression model. The heatmap consists of individual squares that display the correlation strength between every two elements in the dataset. The cells of the heatmap denote the correlation between features and the warmer the color towards red means that blue denotes cooler or negative correlations and the white aspect denotes no correlation. From the chart, these observations can be made. The relationship between X1 and X5 in the data demonstrates a notable positive correlation pattern so that X5 follows X1 value rises. There is a perfect negative correlation between the presence of feature X1 and the absence of feature X3 when there is an increase in the value of (X1) there is a corresponding decrease in the value of (X3). Features X2 and X4 when plotted exhibit a very poor positive correlation, therefore, suggesting that there is no strong positive linear relation between the two22,39,43,47.

The photocatalytic process is modulated by the pH (X1) parameter together with ZrO₂ amount (X2) and contact time (X5) parameters while their mutual relationship with tetracycline ionization state impacts the photocatalyst surface electrical charge. The pH parameter (X1) shapes both the photocatalyst surface charge as well as tetracycline ionization state in the photocatalytic method. Based on the correlation and interaction plots, pH shows a weak positive correlation with contact time (X5), and when the pH is higher than 5 and the contact time is less than 4 min, the removal efficiency of tetracycline increases significantly. Additionally, in the linear model, it is observed that increasing pH leads to a slight increase in removal efficiency, whereas increasing contact time decreases it. The decrease in degradation probably results from two factors: photocatalyst surface saturation and photocatalytic performance reduction over time. The ZrO₂ amount (X2), as the main photocatalyst material in the reaction, plays an important role in initiating and enhancing the photocatalytic oxidation reaction. However, the correlation between X2 and X5 is weak and positive, and with X3 (NaOCl), there is a weak negative correlation. The findings indicate ZrO₂ amount plays a role in reducing removal performance particularly when using elevated NaOCl levels since particles could aggregate or disturb electric charge transfer processes. Finally, contact time (X5) shows a weak positive correlation with pH (X1), but the linear relationships indicate that increasing contact time tends to decrease efficiency in most cases. Long contact time and low pH values lead to substantial decreases in the efficiency levels. On the other hand, optimal conditions where X1 is high and X5 is low are associated with higher removal efficiency. Therefore, the role of X5 needs to be carefully optimized to avoid decreasing performance. The integration of these three modified variables shapes how efficiently the photocatalytic process functions. When these variables (high pH and suitable ZrO₂ amount and contact time within moderate to low ranges) reach optimal adjustments then maximum tetracycline removal occurs.

Analyzing feature importance in ridge regression model

The feature importance chart (Fig. S6 in the supporting information file) is another useful resource if we want to know which design features affect the model most of all. As seen by the results, the bar in this kind of chart is colored uniquely to signify the function of each of them. The length of the bar demonstrates the level of that feature’s influence on the target variable. A horizontal axis has the feature names, X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5 whereas the vertical axis displays the importance degree, and a lighter color in the bar picture indicates a higher degree of importance. Usually any warm tone of colors like red or orange will reflect higher importance than the cooler color like blue or green. From the above chart, therefore, it is clear that feature X2 has the highest bar thus indicating that it impacts very much on the target variable. Both features X1 and X5 as predictors have also high importance; in other words, their bar heights are substantial defining the target variable. Features X3 and X4 are less important which is illustrated by the relatively short length of the bars that correspond to these features. Thus, claims the chart we are dealing with, in fact, the model is more dependent on features X1, X2, and X5 and changes to these features will drastically alter the target variable. Oppositely, feature X3 and feature X4 have relatively less impact on the target and it can be omitted or less prioritized in the subsequent modeling45.

Comparison of regression models performance using MSE

Several regression model performances demonstrate comparison in Fig. 10. Different models were compared based on the existing error. Out of all disparity calculation methods, Mean Squared Error (MSE) is used. The comparison of regression models frequently uses Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the evaluation measure due to its advantageous characteristics. First, MSE squares the errors which means large errors affect the total more, which allows for the identification of models with large mistakes. Further, MSE is continuous and can be differentiated since it involves squared functions useful mainly in optimization techniques such as gradient descent. Strange as it may seem, it is okay to have very large variations of the sizes of the bars in the following sense. A lower MSE means that predicted values are closer to the actual values of the x-axis. The general predictive accuracy indicator of MSE contains information about both model variance and bias. Finally, MSE is a widely recognized standard used extensively in model evaluation. The lower the MSE, the better is the model. MSE in simple words means how wrong is the model on average against other models. Based on the chart, the models are ranked in terms of accuracy as follows. The GBR model has the lowest MSE, demonstrating the best performance among the compared models. The AdaBoost, Random Forest, and Decision Tree models show average performance. The Support Vector Regression (SVR) and K-Nearest Neighbors models have weaker performance compared to the others. Model performance strongly depends on the nature of the data. Linear models like Linear Regression, Ridge Regression and Lasso Regression could be more suitable for the data in case the data set contains a strong linear relationship. In the case of complex relationships of features for instance Random Forest, Gradient Boosting could be used. The important thing about them is that they are pretty good at handling non linear relationships but could be heavier to handle and overfit more frequently when a large number of features is being used or if the data set used for development is comparatively smaller. Model performance relies heavily on parameter tuning because Ridge Regression needs its alpha parameter for preventing overfitting. If we want to be more specific, to compare the results received with two models utilized in this study, we get the following. The Gradient Boosting model outperforms Ridge Regression in all performance evaluation metrics, especially on the test data. In the following, a detailed comparison of these two models is presented based on various metrics. The two models used in this study were ridge regression and gradient boosting models, and comparing these two was of great importance. Based on the comes about gotten, the MSE esteem for training information and test information in ridge regression and gradient boosting models was evaluated as (28 and 18.15) and (2.79 and 0.00082), respectively. Too, the MAE esteem for training information and test information in ridge regression and gradient boosting models was assessed as (4.29 and 3.7) and (1.01 and 0.02), respectively. In expansion, the RMSE esteem for training information and test information in ridge regression and gradient boosting models was evaluated as (5.29 and 4.26) and (1.67 and 0.02), respectively. All these comes about demonstrate the supreme prevalence of the angle boosting demonstrate in precisely foreseeing the comes about. The gradient boosting show performs way better with lower blunders. In R-squared (R2, ridge regression has an R2 of 0.814 on the training information and 0.861 on the test information, showing a great demonstrate fit. In differentiate, the gradient Boosting show has an R2 of 0.981 on the training information and 0.999 on the test information, appearing great fit and exceptionally precise expectations. Gradient Boosting delivers superior performance to Ridge Regression because its entire prediction of test data demonstrates higher results together with robust evaluation metrics MSE, MAE, RMSE, and R2 scores. The Gradient Boosting model should be the preferred choice in this case for research and prediction accuracy48.

Particle swarm optimization model

Optimization performance analysis of the PSO algorithm

Due to its ability to optimize results within extensive search areas the PSO algorithm (Fig. 11) serves as a swarm optimization tool which achieves best solutions through collective efforts of present solutions. The depicted chart displays PSO algorithm convergence throughout different generations as the best fitness curve shows the optimal solutions found by the algorithm across each generation. During the initial convergence phase both best fitness results and mean fitness metrics show rapid improvements because the algorithm discovers better exploration areas. It is evident in the curve that initially the two graphs were in a state of decreasing improvement rates and, ultimately, both tended to a constant value to reach the best final solution and find optimal conditions. A final solution results when the curves approach constant values at points shown clearly in corresponding graphs. Solution quality increases proportionally to vertical axis values that represent fitness measurements. Fitness values continuously increase with smooth modification patterns in these curves because the optimization method strives to improve solution quality through convergent upward forms. The chart shows how PSO-based optimization successfully tackles optimization problems. However, to ensure the discovery of the global optimum, parameter tuning or alternative strategies, such as multiple algorithms running with different parameters, may be required31,49,50.

Analysis of objective function value distribution in optimization problems

The chart (Fig. S7 in the supporting information file) illustrates the frequency distribution of objective function values in an optimization problem. These results are related to PSO. Based on the provided code and the numerical data in the chart, a comprehensive analysis of the optimization algorithm’s performance can be conducted. The chart represents a normal distribution, indicating that most objective function values are concentrated around a central value and gradually decrease toward both ends (See Fig. S6 the supporting information file).

Interpretation of interaction relationships and their impact on removal efficiency in experimental data

The interpretation of interaction relationships with the dependent variable in 3D plots (Fig. 12), focuses on trends of changes, strength of relationships, and coloring based on Removal %. For the plot of X1 vs X5 vs Removal (%), a weak positive relationship between X1 and X5 suggests that as these variables increase, Removal % slightly increases, but the correlation is weak (0.12). Lighter colors indicate higher Removal %, with areas where X1 and X5 are medium or high potentially linked to higher Removal %. For the plot of X2 vs X3 vs Removal (%), the weak negative correlation (−0.14) between X2 and X3 means an increase in X2 likely decreases X3. The effect on Removal % is moderate to low due to the weak correlation. In the plot of X3 vs X4 vs Removal (%), the negative correlation (−0.21) between X3 and X4 suggests that as X3 increases, X4 decreases, with this relationship having a slightly stronger impact on Removal %. The plot of X4 vs X5 vs Removal (%) shows a moderate positive correlation (0.18), suggesting that as X4 increases, X5 increases, potentially influencing Removal %. The relationship network uncovers frail positive relationships between X1 and X5 (0.12) and negative relationships between X2 and X3 (−0.15), X3 and X4 (−0.21), and X1 and X4 (−0.21). Removal % has a weak negative correlation with X2 (−0.23). The linear relationship for interactions shows that for (‘X1’, ‘X5’), an increase in x1 increases Removal %, while an increase in X5 decreases it. For (‘X2’, ‘X3’), both increases in X2 and X3 decrease Removal %, with X2’s effect being stronger. For (‘X3’, ‘X4’), both X3 and X4 negatively affect Removal %, with X3 having a stronger impact. For (‘X4’, ‘X5’), both variables negatively impact Removal %, with X5’s effect being slightly stronger. The interaction analysis shows that in the region where X1 > 5 and X5 < 4, the Removal % is likely higher, while in the region where X1 < 4 and X5 > 6, the Removal % is likely lower. For the interaction between X2 and X3, in the region where X2 > 0.008 and X3 < 0.25, the Removal % may be higher, but in the region where X2 < 0.007 and X3 > 0.28, it will likely be lower. For the interaction between X3 and x4, in the region where X3 > 0.27 and X4 < 15, Removal % may increase, while in the region where X3 < 0.24 and X4 > 18, it is expected to decrease. In the interaction between x4 and X5, in the region where X4 > 15 and X5 < 3, Removal % is likely to increase, while in the region where X4 < 12 and X5 > 6, it will likely decrease. In conclusion, removal efficiency changes based on the conditions derived from the interactions and values of the variables. Favorable combinations (e.g., high X1 and low X5) increase Removal %, while unfavorable combinations (e.g., low X1 and high X5) decrease it22,51.

Histogram analysis of parameter optimization for model refinement