Abstract

This study investigates the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on Green Economic Efficiency (GEE) using panel data from 30 Chinese provinces spanning from 2011 to 2020. The empirical results demonstrate that AI significantly enhances GEE, with its effects varying across regions and governance types. Specifically, AI’s impact is stronger in economically advanced and technologically intensive provinces. In terms of policy governance, excessive Market-based Environmental Regulations (MER) diminish AI’s effect on GEE, while stronger Administrative-command Environmental Regulations (CER) and Informal Environmental Regulations (IER) amplify it. Technological governance, particularly Substantive Green Technological Innovations (SUG), reduces AI’s effectiveness due to high investment thresholds, whereas Symbolic Green Technological Innovations (SYG) increase AI’s impact on GEE. In legal governance, both Administrative Intellectual Property Protection (AIP) and Judicial Intellectual Property Protection (JIP) can reduce AI’s marginal effect, with AIP showing a stronger threshold effect. These findings empirically support the theoretical models of AI-driven green development, highlighting the varying roles of governance mechanisms in promoting GEE and offering actionable insights for policymakers to optimize governance frameworks for sustainable growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global economy continues to expand, environmental sustainability has become one of the most pressing challenges of the twenty-first century. Green Economic Efficiency (GEE), which integrates economic growth with environmental protection, has emerged as a key goal for sustainable development worldwide. The need to address resource depletion, pollution, and climate change has prompted global efforts to transition towards more sustainable economic practices. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been recognized as a transformative force in this process, offering solutions to optimize resource usage, reduce waste, and enhance environmental monitoring. However, the impact of AI on GEE is not uniform and is influenced by various governance frameworks. While global discourse on AI’s role in green development has largely focused on advanced economies, emerging markets, particularly China, offer unique insights into the integration of AI with GEE. As one of the world’s largest economies and a major contributor to environmental challenges, China faces significant opportunities and challenges in harnessing AI to drive green transformation.

GEE is a comprehensive metric that captures the interplay between economic output, resource utilization, and environmental degradation. It reflects a region’s or country’s capacity to achieve economic growth while internalizing environmental costs, thereby offering a more holistic and accurate measure of the ecological implications of economic activities. In the era of rapid digital transformation, AI has emerged as a critical enabler of sustainable green development and a catalyst for enhancing GEE. As a transformative general-purpose technology succeeding the internet, AI underpins the Fourth Industrial Revolution through its core capabilities in deep learning, pattern recognition, and autonomous decision-making. Its cross-sectoral integration enables not only the substitution of traditional technologies but also the acceleration of technological innovation via iterative upgrades and intelligent optimization1,2. AI plays a vital role in promoting cleaner production technologies, optimizing energy consumption, and improving industrial efficiency1,2. Notably, AI-driven improvements in energy structure and efficiency have been identified as major contributors to the slowdown of CO₂ emissions in recent years. Furthermore, AI enhances environmental awareness and promotes behavioral shifts towards low-carbon lifestyles, while also offering innovative solutions to address air pollution3,4. These multifaceted contributions position AI as a strategic force propelling the green economy and improving GEE5.

Despite growing interest in the environmental implications of AI, two significant research gaps remain. First, existing literature largely focuses on the general benefits of AI for green development, with limited exploration of its direct and potentially non-linear impacts on GEE, particularly under diverse governance structures. Second, prior studies tend to examine governance mechanisms—such as policy, regulatory, and institutional dimensions—in isolation, thereby overlooking the potential threshold and interaction effects that arise from their joint influence.

To bridge these gaps, this study constructs an integrated analytical framework that embeds AI within a multi-dimensional governance context to examine its heterogeneous and threshold effects on GEE. Using provincial panel data from 30 Chinese regions spanning 2011 to 2020, this research provides robust empirical evidence that deepens the understanding of AI’s nuanced role in promoting sustainable development. By capturing both direct and non-linear dynamics under differentiated governance regimes, the study offers novel insights into how technological and institutional factors can synergistically enhance green economic performance.

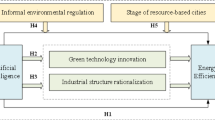

The key research questions addressed in this study are: First, how does AI influence GEE in different regions; Second, what role do governance mechanisms (policy, technological, and legal) play in shaping AI’s impact on GEE; Third how do regional characteristics, such as technological intensity and economic openness, affect the effectiveness of AI in promoting sustainable development. This study makes several notable theoretical contributions to the emerging literature on digital technologies and sustainable development. First, it establishes a novel and unified analytical framework that systematically integrates AI and GEE, thereby addressing a key gap in current research that often treats these domains in isolation. Second, with regard to the underlying mechanisms, the study explores the heterogeneous and non-linear effects of AI on GEE within a comprehensive governance framework. This framework incorporates three critical dimensions—environmental regulation, green technological innovation, and intellectual property protection—revealing how the effectiveness of AI in enhancing GEE is contingent upon the type and strength of governance mechanisms in place. Third, the study advances the literature by considering the spatial heterogeneity of AI’s impact on GEE across regions with varying levels of technological sophistication, institutional openness, and economic development. This multidimensional perspective enables a more nuanced understanding of how AI-driven green development unfolds in different subnational contexts.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section "Literature review" reviews the relevant literature and identifies key research gaps. Section "Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis" develops the theoretical framework and formulates the research hypotheses. Section "Research design" outlines the empirical strategy, including model specification, variable construction, and data sources. Section "Direct effects of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency" presents the baseline regression results on the direct effects of AI on GEE. Section "A mechanistic test of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency" investigates the non-linear and moderating roles of governance mechanisms in shaping the AI–GEE relationship. Section "Discussion and conclusion" concludes by summarizing the main findings and providing policy implications.

Literature review

This study draws upon multiple theoretical paradigms to construct an integrated governance framework that elucidates the mechanisms through which AI influences GEE. The policy governance dimension is grounded in the Porter Hypothesis, which posits that well-designed environmental regulations can stimulate innovation and partially or fully offset the costs of compliance by enhancing productivity and competitiveness6. Technological governance builds on theories of technological change, emphasizing the pivotal role of green innovation in promoting resource efficiency and environmental sustainability7. The legal governance dimension is informed by institutional theory, particularly the notion that robust intellectual property protection can incentivize innovation but may simultaneously constrain knowledge spillovers and the diffusion of green technologies8. By synthesizing these three strands—policy, technology, and law—into a unified analytical framework, this study moves beyond the fragmented perspectives prevalent in existing literature, offering a more holistic understanding of how governance moderates the AI–GEE nexus.

Recent scholarship has increasingly acknowledged AI’s transformative potential for sustainable development. Studies highlight AI’s catalytic role in accelerating green technological innovation and facilitating green economic transitions9. For instance, AI has been shown to reduce carbon intensity through its interaction with natural resource markets, optimize internal resource allocation, and reshape production systems toward greater efficiency. Industrial automation—exemplified by the deployment of robots—has contributed to lower pollutant emission intensity and improved energy efficiency, though it may also introduce negative spatial spillovers on carbon performance10. Moreover, AI-enabled applications, such as real-time environmental monitoring and predictive analytics, have strengthened urban sustainability governance and supported the achievement of green development objectives.

In parallel, technological advancement has been widely recognized as a core driver of GEE. Innovations in renewable energy and digital technologies have demonstrably improved urban green efficiency11. Research also shows that spatially concentrated technological progress enhances GEE, while digital finance facilitates this process by supporting green innovation and diffusion12. For example, Yang et al. (2021b) demonstrated that technological progress contributes to the decoupling of economic growth from carbon emissions and that internet penetration can mitigate haze pollution through innovation-driven mechanisms.

Beyond technological factors, scholars have examined the influence of various socio-economic determinants on GEE. Human capital mismatches have been found to significantly hinder improvements in green efficiency, whereas environmental regulation and openness exhibit non-linear, often U-shaped, effects on GEE13. Moreover, digital transformation has been shown to raise GEE by approximately 2.6%, and economic resilience appears to synergize with green development objectives14.

While the above studies provide valuable insights, notable gaps remain. Specifically, limited attention has been paid to the direct, heterogeneous, and potentially non-linear effects of AI on GEE. Furthermore, the moderating role of integrated governance—combining regulatory, technological, and legal dimensions—within the AI–GEE relationship has yet to be systematically investigated.

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to advance the literature by empirically assessing the impact of AI on GEE while simultaneously incorporating a multidimensional governance framework. By doing so, it not only enriches the theoretical understanding of AI-driven sustainable development but also offers practical implications for optimizing governance structures to amplify the green dividends of emerging technologies.

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

The direct impact of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency

From a technological perspective, the role of AI aligns with classical theories of technological progress, serving as the culmination of advancements in digital and information technologies. While AI shares foundational attributes with earlier digital innovations, it exhibits distinct capabilities—such as autonomous decision-making, adaptive learning, and real-time optimization—that significantly enhance its transformative potential15. First, AI improves production efficiency by automating complex tasks and enabling intelligent system coordination, thereby minimizing resource misallocation, reducing material and energy consumption per unit of output, and ultimately enhancing GEE16. Second, as a foundational and enabling technology, AI accelerates the innovation and deployment of clean energy technologies, reinforcing the green transition through technological upgrading17. Third, in the domain of energy management, AI applications enable the optimization of energy use patterns, facilitate precision-based energy allocation, reduce operational losses, and contribute to substantial gains in overall energy efficiency. Furthermore, AI-enabled systems streamline supply chains by forecasting demand, managing inventories, reducing logistical inefficiencies, and decreasing the carbon footprint associated with production and distribution processes.

From the standpoint of systemic economic efficiency, the pervasive adoption of AI reshapes industrial dynamics by blurring traditional sectoral boundaries and enhancing cross-sectoral connectivity. AI facilitates both horizontal and vertical integration of industries, catalyzing industrial clustering and cooperative development, particularly among green and high-tech sectors18. Empirical evidence indicates that AI adoption has led to the phasing out of outdated capacities and the reduction of pollutant emissions, contributing positively to regional green development trajectories. At a macroeconomic level, AI establishes intelligent economic circulation systems that significantly improve the efficiency of production factors and resource utilization. These intelligent systems help overcome barriers such as market segmentation and institutional frictions, thereby fostering coordinated advances in economic productivity, ecological sustainability, and energy conservation.

Taken together, these technological and systemic pathways suggest that AI may play a direct and significant role in enhancing GEE. Accordingly, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H1

AI directly contributes to improvements in GEE.

The non-linear effect of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under integrated governance

Integrated governance involves multiple stakeholders, including governments, enterprises, social organizations, and citizens, sharing resources and collaborating to address public affairs and maximize public interest. The integrated governance model breaks through the limitations of the traditional government’s single-subject management and emphasizes multiple subjects’ joint participation and synergy19. These stakeholders leverage their strengths to create complementary effects during the governance process. Social organizations and the public amplify their influence through media engagement, while companies invest in developing green technologies and AI. Judicial institutions safeguard the rights of innovators in the green economy by enacting and enforcing intellectual property laws. Collectively, these actions contribute to advancements in GEE facilitated by AI. Consequently, this paper explores how AI enhances GEE within the framework of collaborative governance involving policy, technology, and law.

The non-linear impact of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under policy governance

Amid growing concerns over resource depletion and environmental degradation, China has implemented a variety of environmental regulatory instruments to support green economic transformation. According to the Porter Hypothesis, well-designed environmental regulations can stimulate corporate innovation and enhance competitiveness, thereby offsetting compliance costs and promoting GEE. Understanding how environmental regulation influences AI-driven GEE is thus essential for achieving ecological modernization and China’s “dual carbon” goals. Environmental regulation encompasses a spectrum of instruments—administrative, market-based, and informal—each reflecting different governance logics. This study categorizes environmental regulation into three dimensions: MER, CER, and IER20.

MER leverages fiscal and financial incentives such as tax breaks, subsidies, and green finance to steer enterprises toward cleaner production and AI-enabled innovation. However, excessively stringent MER may elevate compliance burdens and crowd out long-term investments in AI and sustainability21. CER relies on mandatory environmental standards and enforcement to compel technological upgrading and investment in green technologies22, though weak enforcement may limit its effectiveness. IER, shaped by societal norms, media scrutiny, and public awareness, fosters environmental accountability and motivates firms to leverage AI for green innovation and reputational gains23. Based on this framework, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a

Excessively stringent MER may hinder AI-driven improvements in GEE.

H2b

CER positively moderates the relationship between AI and GEE.

H2c

IER enhances the effect of AI on GEE.

The non-linear impact of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under technical governance

As green technology innovation advances, the effect of AI on GEE exhibits notable heterogeneity. Building on Lian et al.24, green innovation can be classified into two forms: substantive green innovation (SUG) and symbolic green innovation (SYG), each reflecting distinct motivations and strategic orientations. SUG refers to deep technological breakthroughs involving long R&D cycles, high investment intensity, and substantial technical uncertainty. While SUG offers high-quality innovation capable of transforming production processes and improving resource efficiency, it is subject to cumulative and threshold effects. Without timely returns, excessive investment in SUG may crowd out other innovation efforts, raise production costs, and diminish firm competitiveness, thereby weakening the capacity of AI to enhance GEE25. In contrast, SYG involves incremental improvements or functional extensions of existing technologies without altering core technical foundations. These innovations typically require shorter development timeframes and lower financial input, enabling rapid implementation. Often policy- or market-driven, SYG allows firms to meet regulatory expectations, improve environmental branding, and enhance competitiveness without significantly compromising broader R&D agendas. SYG, by improving public visibility and profitability, may encourage further adoption of AI and green technologies, thereby amplifying AI’s positive effect on GEE. Although SYG tends to deliver faster short-term benefits, SUG has a more substantial long-term impact by fundamentally reshaping industrial practices and reducing environmental footprints [10]. Given the differential effects, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a

Excessive SUG weakens AI-driven improvements in GEE.

H3b

SYG strengthens AI-driven improvements in GEE.

H3c

The threshold effect of SUG on AI-empowered GEE is stronger than that of SYG.

The non-linear impact of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under legal governance

Intellectual property refers to exclusive rights granted to creators over their intellectual outputs. Effective IP protection ensures that rights holders can fully exercise these privileges. However, due to the high externality of green innovation, innovators often face challenges in preventing imitation or infringement by competitors, which undermines returns on innovation and discourages further investment in environmentally sustainable technologies26. Strengthening IP protection reduces these externalities by safeguarding innovators’ monopoly profits, thus incentivizing green innovation. Nonetheless, overly stringent protection may have adverse consequences. Excessive intellectual property enforcement can hinder the dissemination of technological achievements, reduce knowledge spillovers, and weaken collective innovation incentives (Song and Chen 2023). Grounded in the “economic man” assumption, rights holders are typically reluctant to share proprietary knowledge when monopoly privileges are overly protected, leading to technological lock-in and reduced innovation diffusion. This study distinguishes between two primary forms of IP protection: administrative intellectual property protection (AIP) and judicial intellectual property protection (JIP). AIP, typically enacted by government agencies, directly affects firms’ strategic decisions regarding innovation and green technology adoption. In contrast, JIP, administered by judicial bodies, addresses infringement cases and interprets IP law, but tends to exert less direct influence on corporate behavior due to its reactive nature. As such, the constraining effect of excessive AIP on AI-driven GEE is expected to be more pronounced than that of JIP. Based on this framework, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a

Excessive AIP weakens AI-driven improvements in GEE.

H4b

Excessive JIP weakens AI-driven improvements in GEE.

H4c

The threshold effect of AIP is stronger than that of JIP.

Research design

Data sources

This paper collects the panel data of 30 provinces in mainland China (Missing data for Tibet, not included in statistics) from 2011 to 2020 as the research sample. The data come from the patent database of the China Intellectual Property Office, the National Bureau of Statistics, the China Statistical Yearbook, and statistical bulletins issued by provinces.

Econometric model

To substantiate the enhancement of GEE by AI, the following econometric model is constructed:

In this model, \(Gee\) represents green economic efficiency, \(AI\) represents artificial intelligence, \(Control\) is control variable, \(u_{t}\) and \(\lambda_{i}\) represent time effects and individual effects, and \(\varepsilon\) is the random disturbance term.

Variable descriptions

Dependent variable: green economic efficiency

The traditional Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model is widely used to evaluate the efficiency of decision-making units; however, it cannot account for the impact of undesirable outputs on efficiency and fails to differentiate among multiple efficient units27. To address these limitations, Tone improved the DEA model by introducing a non-radial, non-angular super-efficiency DEA approach that incorporates undesirable outputs, known as the super-efficiency Slack-Based Measure (SBM) model based on undesirable outputs28. This model integrates relaxation variables and resolves the issue of distinguishing efficiency values greater than 1 in traditional SBM models, making it widely applicable in efficiency measurement. This paper draws on the research of Zhou et al.29 to measure GEE by adopting the super-efficient SBM model, including non-expected outputs, selecting labor force, capital, electricity, water resources, and natural gas resources as the input indexes, and selecting the GDP to represent the expected outputs, and selecting the “three wastes” are chosen to represent the non-desired outputs, as they are directly linked to industrial activities and reflect the environmental costs of economic growth30. Although CO2 emissions are important, we did not include them due to their broader, more diffuse nature(Ul Hassan31) (Table 1). The GEE is calculated as follows:

where \(G{\text{ee}}*\) denotes the value of GEE, \(n\) represents the number of the study area, \(k\) denotes the serial number of each province, \(m\) is the input of each province, \(s_{1}\) and \(s_{2}\) denotes the desired output and non-desired output of each province, respectively, \(x\) denotes the input indicator of each province for the period, \(y^{g}\) and \(y^{b}\) denote the desired output indicator and non-desired output indicator of each province during the period, respectively.

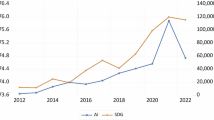

Core explanatory variable: artificial intelligence

Industrial robots are often used as a substitute variable for AI in manufacturing due to their close connection with AI applications. Industrial robots integrate automation and AI technologies to perform tasks such as assembly, welding, and material handling, often with increased precision and efficiency. They reflect the impact of AI in enhancing production efficiency, reducing human error, and optimizing resource use. Following the approach of Liu et al.32, this paper uses the number of industrial robots installed in each province to represent AI. The calculation method, shown in Eq. (4), reflects the relationship between robot stock and labor supply, potentially offering a more effective measure of AI33.

It is assumed that the distribution of industrial robots across Chinese provinces is uniform, meaning each province has the same industrial robot installation density. Thus, the industrial robot installation density = total national industrial robot installations/total national employment. Therefore, the industrial robot installations in each province = industrial robot installation density × employment in each province. The specific formula is as follows:

Formula (4), \(AI_{it}\) indicates the number of industrial robots installed in the \(i\) region during the \(t\) period; \(Robot_{t}\) indicates the total number of industrial robots installed nationally during the \(t\) period; \(L_{it}\) indicates the number of employed persons in the \(i\) region during the \(t\) period; \(L_{t}\) indicates the total number of employed persons nationally during the \(t\) period. To eliminate the effect of dimension, the natural logarithm is taken for the number of industrial robots installed in each province.

Control variables

This paper selects the following control variables to make the model estimation results more accurate: internet infrastructure conditions (\({\text{IIS}}\)), expressed using the logarithm of number of internet broadband access ports; level of economic development (\({\text{PGDP}}\)), expressed using the logarithm of per capita gross regional product; industrial structure (\({\text{ISU}}\)), expressed using the region’s share of the value added of the tertiary industry in the value added of the secondary sector; level of industrialization (\({\text{IL}}\)), described by the ratio of the current year’s industrial added value to the current year’s GDP10,34.

Policy governance: environmental regulation

Environmental regulation is categorized into three dimensions, each measured by distinct proxies. MER is proxied by the ratio of completed investment in industrial pollution control to industrial value added, capturing financial incentives and cost pressures that encourage firms to adopt green practices, consistent with the Porter Hypothesis35. CER is measured by the logarithm of granted environmental administrative penalties, reflecting the intensity of regulatory enforcement and compliance pressure on enterprises36. IER is constructed via entropy-weighted integration of indicators including per capita disposable income, educational attainment, population density, and age structure. These variables collectively capture public environmental awareness and societal participation in environmental governance, underscoring the normative and informal channels through which environmental outcomes are influenced37).

Technical governance: green technology innovation

Green patents intuitively reflect the extent and level of green technology innovation. Considering that granted patents have undergone authoritative certification, this paper uses the logarithm of granted green invention and utility patents to depict SUG and SYG24.

Legal governance: intellectual property protection

The number of cases closed refers to patent infringement cases adjudicated and concluded within a given period, serving as an indicator of the effectiveness and capacity of administrative or judicial institutions in enforcing intellectual property rights. Compared to the number of cases filed—which may be subject to selective reporting and greater uncertainty—closure data offers a more objective and stable measure. Accordingly, this study employs the logarithm of administratively closed patent infringement cases to proxy the level of AIP, and the logarithm of judicially closed cases to represent JIP38.

Direct effects of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency

Descriptive statistics

All variables are min–max normalization standardized to improve estimation accuracy and eliminate the effects of dimensions. Table 2 presents the variable descriptive statistics.

Benchmark regression analysis

The benchmark regression results are displayed in Table 3. The estimation results reported in Model (1)–Model (5) show that the regression coefficients and significance of the core explanatory variables and control variables did not change radically during the gradual approach to introducing the control variables. Considering control variables, for every 1% improvement in AI, GEE increases by about 0.281%, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that AI can improve GEE and preliminarily verify H1.

Robustness and endogeneity tests

To ensure the robustness of the results of the benchmark regression, this paper conducts robustness tests from three aspects: winsorize, changing estimation methods, and replacing core variables, with results shown in Table 4. First, for winsorize, using the method of deleting 1% extreme samples, the results are shown in column (1); the coefficient of AI is 0.281 and passes the 1% significance level test. Second, this paper employs the system GMM regression model for re-estimation, with results displayed in column (2). The regression coefficient for AI is 0.512, which is significant at the 1% level. Third, by changing the independent variable to the number of AI companies as a substitute, the results in column (3) show an AI regression coefficient of 0.595, tested by the 1% significance level. These robustness test results are aligned with the benchmark regression, further verifying the positive influence of AI on GEE. To address the endogeneity, this paper employs the two-stage instrumental variable least squares (IV-2SLS) method for testing. This paper uses the first lag of the dependent variable as an instrumental variable. The endogeneity test results in column (4) indicate that the instrumental variable is significantly at the 1% level and passes the weak identification test and the non-identification test, confirming the effectiveness of the instrumental variable selection.

Heterogeneity analysis

To assess the geographical heterogeneity of AI’s impact on green economic efficiency (GEE), the sample was grouped by economic region (Eastern, Central, Western), level of openness (coastal vs. non-coastal), and technology intensity (technology-intensive vs. non-technology-intensive), with results presented in Table 5. AI has a significant positive effect on GEE in the Eastern (0.331) and Central (0.209) regions, both significant at the 1% level, but shows no significant effect in the Western region. This suggests that the influence of AI on GEE is strongest in economically advanced regions. In coastal areas, AI also exerts a stronger effect (0.329, significant at the 1% level) compared to non-coastal areas (0.106), indicating that openness enhances the role of AI in promoting GEE. Similarly, the effect of AI is pronounced in technology-intensive regions (0.440, significant at the 1% level), while the impact is statistically insignificant in non-technology-intensive regions. These findings highlight that AI’s contribution to GEE is conditioned by regional economic development, openness, and technological capacity.

Spatial effects test of artificial intelligence empowering green economic efficiency

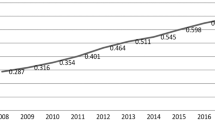

Moran’s I test

To recognize spatial effects, the first step is to use the Moran’s I index for testing spatial correlations (building an economic inverse distance spatial weight matrix W using the reciprocal of provincial capital distances, then integrating economic factors to construct an economic and geographical nested matrix), with results shown in Table 6. Moran’s I index of AI is over 0 and passes the significance test in most years, indicating that AI has strikingly positive spatial dependence properties. The Moran’I index of GEE is over 0 in both matrices. Most years, it passes the significance test, indicating that GEE demonstrates a clear positive spatial dependence property.

Spatial econometrics test

This study compares the suitability of the (SAR and the SEM using the LM tests and further applies Wald and LR tests to assess whether the SDM can be simplified to SAR or SEM. As shown in Table 7, under the geographic weight matrix, both the LM-lag and RLM-lag tests are significant at the 1% level, while the LM-error is only significant at the 5% level and the RLM-error is not statistically significant. For the nested economic-geographic matrix, the LM-lag is significant at the 5% level, and the RLM-lag at the 1% level, whereas the error-based tests remain insignificant. Furthermore, Wald and LR tests reject the null hypothesis that SDM can be reduced to SEM under the geographic weight matrix. Under the economic-geographic nested matrix, all tests confirm the appropriateness of the SDM specification. Based on these results, this study proceeds with SDM and SAR for subsequent spatial analysis.

Spatial econometrics regression

Table 8 presents the results of the spatial spillover effects across two weight matrices and various spatial models. The estimated coefficient of AI’s spatial effect on GEE is significantly positive, indicating that AI in a given region enhances the GEE of neighboring areas. This suggests that AI not only boosts local GEE but also exerts a spatial spillover effect, radiating and driving improvements in the GEE of neighboring regions.

A mechanistic test of artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency

Artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under policy governance

The results in Table 9 show that different threshold effects of various environmental regulation policies influence AI-empowered GEE. If the p-value is significant at the 10% level, it means that they passed the single or multiple threshold test, MER and CER satisfy the single threshold significance test, while IER meets the single and double threshold significance test criteria.

This paper further examines the threshold effects of heterogeneous environmental regulation, as presented in Table 10. When MER exceeds the threshold, the regression coefficient decreases from 0.441 to 0.238, weakening the positive impact of AI on GEE. This finding supports H2a. Conversely, when the intensity of CER surpasses the first threshold, the coefficient rises from 0.101 to 0.249, enhancing AI’s positive impact on GEE, which supports H2b. Similarly, for IER, when its intensity exceeds the first threshold but remains below the second, the coefficient increases from 0.123 to 0.269. Upon crossing the second threshold, the coefficient increases to 0.408, which is significant at the 1% level. These results indicate that a higher intensity of IER strengthens AI’s effect on GEE, supporting H2c.

Artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under technological governance

Table 11 results show that GEE enabled by AI is influenced by different threshold effects of heterogeneous green technology innovations. SUG has passed single and double threshold significance tests, while SYG has passed the single threshold significance test.

This study investigates the thresholds of heterogeneous green technologies innovation, as summarized in Table 12. When SUG’s intensity exceeds the first threshold but remains below the second, the coefficient decreases from 0.555 to 0.122. Beyond the second threshold, the coefficient rises to 0.319. These results indicate that the marginal effect of AI on GEE diminishes significantly after SUG surpasses the first threshold but partially recovers upon exceeding the second threshold. However, the effect remains weaker than observed before crossing the first threshold, supporting H3a. For SYG, when their intensity surpasses the first threshold, the coefficient increases from 0.084 to 0.249. This finding suggests that SYG enhances the marginal effect of AI on GEE, supporting H3b. Additionally, the threshold effects of SUG (0.433 and 0.197) are greater than those of SYG (0.165), supporting H3c.

Artificial intelligence on green economic efficiency under legal governance

The results in Table 13 illustrate that AIP and JIP get through the single threshold significance test, signalling that the efficiency of AI-empowered GEE is affected by the threshold effect of AIP and JIP.

This paper further examines the role of heterogeneous intellectual property protection thresholds, as depicted in Table 14. When the intensity of AIP exceeds the first threshold, the coefficient decreases from 0.423 to 0.165, significantly diminishing the marginal effect of AI on GEE. This finding supports H4a. Similarly, when the JIP surpasses the first threshold, the coefficient declines from 0.232 to 0.150, reducing AI’s marginal effect on GEE and supporting H4b. Moreover, the threshold effect of AIP (0.258) is greater than that of JIP (0.082), providing evidence for H4c.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

AI’s impact on GEE: the significant contribution of AI to enhancing green economic efficiency aligns with the findings of Luo and Feng39, Wang et al.40. However, it contrasts with the conclusions of Lee et al.41, who consider the initial application stage of AI. During this stage, AI may negatively affect the energy transition. Over time, as AI progresses beyond its early implementation phase, its positive impacts are expected to outweigh the adverse effects associated with technological development and scale, ultimately driving the energy transition. The stronger impact of AI in economically advanced and technologically intensive regions can be attributed to better infrastructure, higher levels of digitalization, and stronger human capital, all of which create a conducive environment for AI adoption. Regions with more openness to technological innovation, better institutional support, and higher R&D investment are better equipped to leverage AI technologies, which in turn enhances GEE42. This aligns with findings in the literature that highlight the role of technological infrastructure and human capital in determining AI’s effectiveness.

The role of policy governance: Policy governance is one of the most significant factors influencing the successful integration of AI into green economic strategies. the conclusion that variations in environmental regulation influence the marginal impacts of AI-empowered GEE aligns with the findings of Sun et al.43, Wang et al.44. However, it may diverge from the conclusions of You et al.45, who overlooked the cost impacts associated with environmental regulation. The regulatory environment created by government policies shapes the incentives, investments, and adoption patterns of AI technologies. MER are commonly used in many countries to regulate environmental impacts through market mechanisms like carbon pricing, emissions trading, and green subsidies46. However, our findings suggest that excessive reliance on MER can create obstacles to AI adoption. When the market is flooded with regulatory costs or when compliance is too complex, businesses may become hesitant to invest in AI technologies, which require substantial initial capital. In such cases, AI technologies may be viewed as an added financial burden rather than an opportunity for increasing GEE. In contrast, CER, which include direct government mandates and interventions, provide a clearer and more immediate signal for businesses to adopt AI47. These policies set explicit guidelines, goals, and timetables for environmental improvements, offering businesses the regulatory certainty and incentives needed to invest in AI. Such regulations also have the advantage of creating a more structured environment where AI technologies can be deployed in a controlled and measurable way, ensuring that environmental goals are met. Furthermore, IER, such as industry-specific guidelines or voluntary green standards, can also facilitate AI adoption by promoting sustainability initiatives without heavy-handed enforcement48. These types of regulations allow businesses to experiment with AI technologies while adhering to broadly defined environmental goals. Informal regulations can be particularly effective in regions with lower regulatory enforcement capacities, as they foster innovation while still encouraging green practices. The flexibility and adaptability of IER can create a dynamic space for AI technologies to evolve in response to industry needs and environmental challenges.

The role of technical governance: Technological governance plays a pivotal role in determining how effectively AI contributes to GEE. The conclusion regarding the marginal effect of heterogeneous green technology innovation on AI-empowered GEE aligns with the findings of Lian et al.24 and Chen et al.49. However, Wang et al.50 warn that green innovation may escalate corporate debt default risks, thereby affecting financial performance and reducing GEE. The varying effects observed in this study can be attributed to the differences in the types of technological innovations being adopted. SUG often require high capital investment and long-term infrastructure development, which can delay the implementation of AI technologies. In contrast, these innovations tend to have more profound and lasting impacts on GEE once they are fully integrated51. However, the high upfront costs and long implementation timelines can create significant barriers, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or less-developed regions24. SYG, on the other hand, involve lower initial investment and are typically easier to implement. They may not have as large an immediate impact on GEE, but they can create favorable conditions for AI adoption by introducing less resource-intensive innovations. This makes them more accessible for a wider range of industries and regions. SYG can serve as an important stepping stone, helping to lay the groundwork for more substantial green technological changes in the future52. The threshold effect of SUG is also influenced by the existing level of technological infrastructure and the ability of businesses to absorb the necessary capital and knowledge.

The role of legal governance: Legal frameworks also play a critical role in shaping AI’s impact on GEE, especially when it comes to intellectual property (IP) protection and innovation incentives. Excessive AIP and JIP may reduce the marginal effects of AI on GEE. Wang et al.53 and Hudson and Minea54 have highlighted the non-linear impact of intellectual property protection on the green innovation capabilities of the manufacturing sector and innovation at large. Hu et al.55 particularly underscore the importance of stringent regulatory enforcement of intellectual property protection levels to foster innovation. AIP are designed to safeguard AI innovations, but they can sometimes create rigid structures that hinder the flexibility needed for rapid technological adoption. Overly strict regulations can prevent businesses from adapting quickly to new developments in AI technology, thus reducing its ability to drive GEE56. In contrast, JIP is more supportive of AI adoption, as it ensures that companies are able to secure the intellectual property rights associated with their innovations. This creates incentives for further investment in AI and green technologies, as businesses are more likely to invest in research and development if they can capture the full benefits of their innovations57. JIP helps protect the intellectual property of AI-driven green technologies, making it more feasible for companies to integrate AI into their production systems. The presence of strong judicial IP protection is crucial for promoting innovation, as it provides businesses with the confidence to invest in AI technologies without fear of having their innovations copied or undermined.

Different geographical scopes: some have demonstrated that AI may enhance GEE in economies with development levels similar to China’s. For instance, Akram et al.58 found that AI supports high-quality economic development in emerging economies by facilitating energy transition and green technology innovation. Similarly, Salman et al.59 confirmed that technological progress has raised the carbon neutrality rates of G20 countries. On a global scale, other studies provide evidence that AI can enhance GEE. Tao33 reported that AI has boosted global green productivity. Additionally, Lee et al.41 confirmed that AI has promoted energy transition and reduced carbon emissions across 69 countries. Despite variations in countries and economic conditions, AI promotes green and sustainable development through technological advancements, thereby extending the conclusions of this paper.

Conclusion and practical implications

This study delves into the nuanced impact of AI on GEE within an integrated governance framework. The findings reveal several key insights: (1) Regional Impact of AI on GEE: AI significantly boosts GEE, with its most substantial effects observed in economically advanced and technologically intensive regions, particularly in eastern and coastal provinces. This demonstrates that AI’s influence on GEE is not uniform but is conditioned by regional economic openness and technological capacity. (2) Policy Governance: Excessive MER undermine the positive effect of AI on GEE, while CER and IER strengthen AI’s marginal impact. These findings highlight the importance of balanced and tailored regulatory approaches to maximize AI’s potential for sustainable growth. (3) Technological Governance: The study finds that SUG reduce AI’s effectiveness on GEE due to high investment requirements. In contrast, SYG enhance the effect, though their impact is more modest compared to SUG. This suggests that the nature and scale of technological innovations influence how AI can drive green efficiency. Legal Governance: Both AIP and JIP diminish AI’s impact on GEE, with AIP exhibiting a more substantial threshold effect. This underscores the need for balanced intellectual property policies that protect innovation without stifling the diffusion of green technologies.

First, policy governance should focus on offering clear incentives for AI adoption, such as subsidies and tax breaks for AI-driven green technologies. CER are more effective than MER in creating regulatory certainty, thus fostering innovation and reducing barriers for businesses. Additionally, IER such as voluntary green standards or industry guidelines, can complement formal regulations by encouraging companies to innovate without heavy-handed enforcement, thus fostering a more flexible and collaborative approach to sustainability. Second, technological governance should prioritize SYG in regions with limited resources, as they are less capital-intensive and facilitate early-stage AI adoption. For more developed regions, promoting SUG through R&D incentives and public–private partnerships is essential to accelerate AI-driven sustainability. Third, legal governance must strike a balance between protecting intellectual property through JIP while ensuring that AIP remain flexible enough to support rapid AI deployment, encouraging innovation without stifling it. Fourth, regional policies must address disparities by providing targeted support: economically advanced regions should focus on enhancing AI infrastructure and R&D, while less developed regions should prioritize AI skill development, financial support for SMEs, and access to AI-driven green technologies.

Limitations and prospects

This paper has shortcomings in the following aspects, which deserve to be supplemented and improved in subsequent studies. First, the research is limited to China, and future studies might consider expanding this geographical scope. Second, upon collecting all variable data, numerous missing values were identified after 2020. Additionally, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, substantial changes in policy and market conditions may have rendered data from the pandemic period incomparable with data from other periods. Consequently, the data has only been updated through 2020 to ensure availability and reliability. Third, environmental protection outputs are not included in the indicator system when assessing GEE. Future research should further investigate the direct impacts of AI on green economic efficiency, specifically through the lenses of industrial structure and green innovation. Fourth, this study primarily focuses on the efficiency of AI during the operational phase without comprehensively evaluating the entire lifecycle of AI models, including the resource-intensive training and deployment phases that may increase carbon emissions. Future research should assess the green economic efficiency across the whole lifecycle of AI models.

Data availability

The data used in this article are obtained through databases and third-party websites, and are available to readers, mainly related to the following databases: China statistical yearbook, the National Bureau of Statistics official website, website https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/, international industrial robots database https://ifr.org/, CNRDS China research data services platform www.cnrds.com.

References

Abulibdeh, A., Zaidan, E. & Abulibdeh, R. Navigating the confluence of artificial intelligence and education for sustainable development in the era of industry 4.0: Challenges, opportunities, and ethical dimensions. J. Clean. Prod. 437, 140527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140527 (2024).

Konya, A. & Nematzadeh, P. Recent applications of AI to environmental disciplines: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167705 (2024).

Adnan, M. et al. Human inventions and its environmental challenges, especially artificial intelligence: New challenges require new thinking. Environ. Challenges 16, 100976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100976 (2024).

Cai, D., Aziz, G., Sarwar, S., Alsaggaf, M. I. & Sinha, A. Applicability of denoising-based artificial intelligence to forecast the environmental externalities. Geosci. Front. 15(3), 101740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2023.101740 (2024).

Bibri, S. E., Alexandre, A., Sharifi, A. & Krogstie, J. Environmentally sustainable smart cities and their converging AI, IoT, and big data technologies and solutions: An integrated approach to an extensive literature review. Energy Inf. 6(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42162-023-00259-2 (2023).

Porter, M. E. & van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9(4), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.4.97 (1995).

Dao, N. B., Dogan, B., Ghosh, S., Kazemzadeh, E. & Radulescu, M. Toward sustainable ecology: how do environmental technologies, green financial policies, energy uncertainties, and natural resources rents matter?. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-024-02887-y (2024).

DiMaggio, P. J. & Powell, W. W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101 (1983).

Zhao, P., Gao, Y. & Sun, X. How does artificial intelligence affect green economic growth?—Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155306 (2022).

Zhou, W., Zhuang, Y. & Chen, Y. How does artificial intelligence affect pollutant emissions by improving energy efficiency and developing green technology. Energy Econ. 131, 107355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107355 (2024).

Huang, L., Zhang, H., Si, H. & Wang, H. Can the digital economy promote urban green economic efficiency? Evidence from 273 cities in China. Ecol. Ind. 155, 110977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110977 (2023).

Liu, Y. & Dong, F. How technological innovation impacts urban green economy efficiency in emerging economies: A case study of 278 Chinese cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 169, 105534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105534 (2021).

Shuai, S. & Fan, Z. Modeling the role of environmental regulations in regional green economy efficiency of China: Empirical evidence from super efficiency DEA-Tobit model. J. Environ. Manage. 261, 110227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110227 (2020).

Wang, J. & Zhou, X. Measurement and synergistic evolution analysis of economic resilience and green economic efficiency: Evidence from five major urban agglomerations. China. Appl. Geogr. 168, 103302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2024.103302 (2024).

Ahmed, I., Jeon, G. & Piccialli, F. From artificial intelligence to explainable artificial intelligence in industry 4.0: A survey on what, how, and where. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 18(8), 5031–5042. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3146552 (2022).

Tian, H., Zhao, L., Yunfang, L. & Wang, W. Can enterprise green technology innovation performance achieve “corner overtaking” by using artificial intelligence?—Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 194, 122732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122732 (2023).

Li, Q., Zhang, J., Feng, Y., Sun, R. & Hu, J. Towards a high-energy efficiency world: Assessing the impact of artificial intelligence on urban energy efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 461, 142593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142593 (2024).

Yang, H. C., Xu, X. Z. & Zhang, F. M. Industrial co-agglomeration, green technological innovation, and total factor energy efficiency. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(41), 62475–62494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20078-4 (2022).

Sedlacek, S., Tötzer, T. & Lund-Durlacher, D. Collaborative governance in energy regions—Experiences from an Austrian region. J. Clean. Prod. 256, 120256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120256 (2020).

Song, W., Han, X. & Liu, Q. Patterns of environmental regulation and green innovation in China. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 71, 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2024.07.006 (2024).

Koengkan, M., Fuinhas, J. A. & Kazemzadeh, E. Do financial incentive policies for renewable energy development increase the economic growth in Latin American and Caribbean countries?. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 14(1), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2022.2031849 (2024).

Chen, C., Hu, Y. H., Karuppiah, M. & Kumar, P. M. Artificial intelligence on economic evaluation of energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 47, 101358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101358 (2021).

Zhang, H., Tao, L. C., Yang, B. Y. & Bian, W. L. The relationship between public participation in environmental governance and corporations? environmental violations. Financ. Res. Lett. 53, 103676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103676 (2023).

Lian, G., Xu, A. & Zhu, Y. Substantive green innovation or symbolic green innovation? The impact of ER on enterprise green innovation based on the dual moderating effects. J. Innov. Knowl. 7(3), 100203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100203 (2022).

Fang, G., Gao, Z., Wang, L. & Tian, L. How does green innovation drive urban carbon emission efficiency? —Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Clean. Prod. 375, 134196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134196 (2022).

Hall, B. H. & Helmers, C. Innovation and diffusion of clean/green technology: Can patent commons help?. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 66(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.12.008 (2013).

Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 130(3), 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(99)00407-5 (2001).

Aparicio, J., Ortiz, L. & Pastor, J. T. Measuring and decomposing profit inefficiency through the Slacks-Based Measure. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 260(2), 650–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2016.12.038 (2017).

Zhou, C., Shi, C., Wang, S. & Zhang, G. Estimation of eco-efficiency and its influencing factors in Guangdong province based on Super-SBM and panel regression models. Ecol. Ind. 86, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.12.011 (2018).

Yasmeen, R., Padda, I. U. H. & Shah, W. U. H. Untangling the forces behind carbon emissions in China’s industrial sector—A pre and post 12th energy climate plan analysis. Urban Clim. 55, 101895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2024.101895 (2024).

Shah, U. H. Energy efficiency evaluation, technology gap ratio, and determinants of energy productivity change in developed and developing G20 economies: DEA super-SBM and MLI approaches. Gondwana Res. 125, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2023.07.017 (2024).

Liu, J., Chang, H. H., Forrest, J. Y. L. & Yang, B. H. Influence of artificial intelligence on technological innovation: Evidence from the panel data of china’s manufacturing sectors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 158, 120142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120142 (2020).

Tao, M. Digital brains, green gains: Artificial intelligence’s path to sustainable transformation. J. Environ. Manage. 370, 122679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122679 (2024).

Feng, C., Ye, X., Li, J. & Yang, J. How does artificial intelligence affect the transformation of China’s green economic growth? An analysis from internal-structure perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119923 (2024).

Xu, B. Environmental regulations, technological innovation, and low carbon transformation: A case of the logistics industry in China. J. Clean. Prod. 439, 140710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140710 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Li, R., Song, Y. & Sahut, J.-M. The impact of environmental regulation on the optimization of industrial structure in energy-based cities. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 68, 102154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.102154 (2024).

Shen, Q., Pan, Y. & Feng, Y. Identifying and assessing the multiple effects of informal environmental regulation on carbon emissions in China. Environ. Res. 237, 116931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116931 (2023).

Li, W. & Yuan, B. Intellectual property protection and M&A performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 64, 105395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105395 (2024).

Luo, Q. & Feng, P. Exploring artificial intelligence and urban pollution emissions: “Speed bump” or “accelerator” for sustainable development?. J. Clean. Prod. 463, 142739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142739 (2024).

Wang, Q., Zhang, F., Li, R. & Sun, J. Does artificial intelligence promote energy transition and curb carbon emissions? The role of trade openness. J. Clean. Prod. 447, 141298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141298 (2024).

Lee, C.-C., Yan, J. & Li, T. Ecological resilience of city clusters in the middle reaches of Yangtze river. J. Clean. Prod. 443, 141082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141082 (2024).

Li, L., Zhao, J., Yang, Y. & Ma, D. Artificial intelligence and green development well-being: Effects and mechanisms in China. Energy economics 141, 108094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.108094 (2025).

Sun, J., Zhai, N., Miao, J., Mu, H. & Li, W. How do heterogeneous environmental regulations affect the sustainable development of marine green economy? Empirical evidence from China’s coastal areas. Ocean Coast. Manag. 232, 106448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106448 (2023).

Wang, Z.-R., Fu, H.-Q. & Ren, X.-H. The impact of political connections on firm pollution: New evidence based on heterogeneous environmental regulation. Pet. Sci. 20(1), 636–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2022.10.019 (2023).

You, Z., Hou, G. & Wang, M. Heterogeneous relations among environmental regulation, technological innovation, and environmental pollution. Heliyon 10(7), e28196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28196 (2024).

Lu, H., Zhang, Y., Jiang, J. & Cao, G. Do market-based environmental regulations always promote enterprise green innovation commercialization?. J. Environ. Manage. 375, 124183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.124183 (2025).

Chen, Y., Du, K., Sun, R. & Wang, T. Can strict environmental regulation reduce firm cost stickiness? Evidence from the new environmental protection law in China. Energy Econ. 142, 108218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2025.108218 (2025).

Liu, X., Deng, L., Dong, X. & Li, Q. Dual environmental regulations and corporate environmental violations. Financ. Res. Lett. 62, 105230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105230 (2024).

Chen, C., Li, W.-B. & Zhang, H. How do property rights affect corporate ESG performance? The moderating effect of green innovation efficiency. Financ. Res. Lett. 64, 105476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105476 (2024).

Wang, X., Guo, Y. & Fu, S. Will green innovation strategies trigger debt default risk? Evidence from listed companies in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 62, 105216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105216 (2024).

Jiang, L. & Bai, Y. Strategic or substantive innovation? -The impact of institutional investors’ site visits on green innovation evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 68, 101904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101904 (2022).

Hu, Y., Jin, S., Ni, J., Peng, K. & Zhang, L. Strategic or substantive green innovation: How do non-green firms respond to green credit policy?. Econ. Model. 126, 106451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2023.106451 (2023).

Wang, Y., Shi, J. & Qu, G. Research on collaborative innovation cooperation strategies of manufacturing digital ecosystem from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. Comput. Ind. Eng. 190, 110003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2024.110003 (2024).

Hudson, J. & Minea, A. Innovation, intellectual property rights, and economic development: A unified empirical investigation. World Dev. 46, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.023 (2013).

Hu, X., Zhang, Z. & Lv, C. The impact of technological transformation on basic research results: The moderating effect of intellectual property protection. J. Innov. Knowl. 8(4), 100443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100443 (2023).

Abdin, J., Sharma, A., Trivedi, R. & Wang, C. Financing constraints, intellectual property rights protection and incremental innovation: Evidence from transition economy firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 198, 122982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122982 (2024).

Chen, D. & Chen, S. Promoting corporate independent innovation through judicial protection of intellectual property rights. China Econ. Q. Int. 4(3), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceqi.2024.09.002 (2024).

Akram, R., Li, Q., Srivastava, M., Zheng, Y. & Irfan, M. Nexus between green technology innovation and climate policy uncertainty: Unleashing the role of artificial intelligence in an emerging economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 209, 123820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123820 (2024).

Salman, M., Wang, G., Qin, L. & He, X. G20 roadmap for carbon neutrality: The role of Paris agreement, artificial intelligence, and energy transition in changing geopolitical landscape. J. Environ. Manage. 367, 122080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122080 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Writing—review & editing. YD: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Z., Deng, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency under integrated governance. Sci Rep 15, 25919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03817-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03817-8