Abstract

Engineered iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have potential applications in agriculture, but their effects vary depending on their composition, concentration, and plant species. In this study, we investigated the biological effects of iron oxide nanoparticles stabilized with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMA-IONPs) on Zea mays (corn). The nanoparticles were characterized by transmission and scanning electron microscopy (TEM, SEM), revealing an average diameter of 10.78 nm, and by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, which confirmed TMA binding and colloidal stability in an aqueous medium. Corn seeds were germinated directly in aqueous solutions of TMA-IONPs at six concentrations ranging from 7.6 to 45.6 mg/L. Seedlings were grown under controlled environmental conditions, and all analyses were performed on day seven of seedling development. The following parameters were assessed: germination rate; seedling growth (shoot and root length); chlorophyll content; antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase and peroxidase); and mitotic index in root meristematic cells. Concentrations up to 45.6 mg/L significantly enhanced germination, biomass accumulation, chlorophyll biosynthesis, and enzymatic antioxidant activity. The highest mitotic index was observed at 38 mg/L with a low incidence of chromosomal aberrations. These findings suggest that low concentrations of TMA-IONPs promote corn seedling growth by stimulating cell division and modulating oxidative stress response. Further research is required to assess the broader agricultural potential and safety of these nanoparticle formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given the limited natural resources essential for agriculture, technical intervention is increasingly required for sustainable crop production. This necessity has propelled the exploration of nanotechnology and nanomaterials in the plant sciences. Nanoparticles (NPs), typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm1, have been applied to enhance nutrient uptake, increase crop yields, and reduce the reliance on conventional agrochemicals2. Corn (Zea mays), a globally important cereal crop, has been widely used as a model plant to study the influence of various nanoparticles on plant growth and productivity. Studies have demonstrated improved germination, growth, and antioxidant responses in corn following treatment with zero-valent metal nanoparticles (Cu, Fe, Co) under both controlled and field conditions3.

Among the nanomaterials, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) such as iron oxides are of particular interest because of their intrinsic magnetic properties, high surface-to-volume ratio, and biocompatibility4. These features facilitate functionalization and enhance their performance in biological systems. MNPs have been reported to improve plant tolerance to abiotic stress factors, including salinity, particularly in crops such as corn and tomatoes5. Iron oxide nanoparticles, primarily magnetite (Fe3O4) and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), have gained attention because of their superparamagnetism, stability, and biocompatibility, which are strongly modulated by their surface coating6,7. Although generally considered safe, their phytotoxicity remains incompletely understood, as their biological effects are influenced by factors such as particle size, surface charge, coating material, and concentration8. Experimental inconsistencies across studies may stem from variations in nanoparticle synthesis, properties, and exposure protocols9,10. Scientific evidence suggests that MNPs can have dual effects on plant physiology: low concentrations tend to promote growth, whereas higher concentrations may induce oxidative stress and inhibit development2,11. A better understanding of these effects, particularly in relation to nanoparticle uptake, bioaccumulation, and genotoxicity, is essential for their application in agriculture.

The objective of this study was to investigate the concentration-dependent biological effects of a novel sample of iron oxide nanoparticles stabilized with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMA-IONPs) on Zea mays seedlings under controlled laboratory conditions. This study builds upon our previous findings12, which showed a stimulatory effect of low TMA-IONP concentrations on chlorophyll content and shoot length in Zea mays. In the present study, a different synthetic route was used, resulting in nanoparticles with a larger average size.

The influence of TMA-IONPs concentration on plant physiological and cytogenetic responses was assessed by evaluating the germination rate, seedling development, chlorophyll content, antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase and peroxidase), mitotic index, and chromosomal aberrations.

These findings contribute to a better understanding of the interactions between iron oxide nanoparticles and crop plants, serving as a basis for the development of safe and effective nanotechnological tools for agriculture.

Materials and methods

Reagents and biological materials

All reagents used in this study were of reactive grade and were utilized without additional purification. Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), 25% ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH), 25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution (N(CH3)4OH), 30% hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2), and pyrogallol were procured from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) were obtained from J.T. Baker Chemical Company, Holland, while absolute ethanol and glacial acetic acid were sourced from ChimReactiv SRL, Bucharest, Romania. Acetone was supplied by SILAL Trading-Chemical Reagent Company, Bucharest, Romania, and phosphate buffer (pH 7) was acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA.

Corn (Zea mays) seeds were judiciously chosen as the biological material for this study, given their profound economic significance within the realms of agriculture and the food industry. A local farmer from Săliște, Sibiu County, Romania, where the corn was locally sourced, supplied the experimental batch of intact corn seeds with consistent genetic characteristics and without visible defects, insect damage or malformation.

Synthesis and characterization of iron oxide nanoparticles

Iron oxide nanoparticles of TMA-IONPs were synthesized using a modified approach of controlled chemical co-precipitation of ferric and ferrous ions, with the addition of ammonia as an alkaline agent, following the synthesis protocol outlined in13. Ferrophase synthesis was conducted at approximately 80 °C temperature, with subsequent stabilization in a colloidal suspension with tetramethylammonium hydroxide through electrostatic interactions. The procedure for synthesizing the ferrophase was as follows: two slightly supersaturated solutions were prepared, with the first solution containing 4.16 g FeCl2·4H2O in 380 mL of water, and the second solution containing 10.44 g FeCl3·6H2O in 380 mL of water. These solutions, preheated to 80 °C, were combined in a one-liter vessel and continuously stirred using a magnetic stirrer. Once a well-homogenized solution was achieved, it was heated to 80 °C, and then a precipitating reagent (40 mL of 25% ammonia solution) was added at a constant flow rate of 1–2 mL per second, while the mixture was continuously stirred with a magnetic stirrer. During the precipitation reaction, the temperature was closely monitored to ensure that it remained above 70–80 °C. Subsequently, stirring was stopped, and the resulting precipitate was swiftly cooled and separated in a non-uniform magnetic field generated by a strong permanent magnet placed beneath the vessel. The clear liquid was decanted, and the sediment was then washed with approximately 1.5–2 L of warm distilled water in multiple stages to eliminate ammonium chloride byproducts from the precipitation. Throughout each wash, the precipitate was vigorously stirred along with the washing solution to ensure thorough cleaning. From the quantities of the substances used, 3.5 g of ferrophase was obtained. In general, it should be noted that the amount of ferrophase achieved by the chemical precipitation protocol cannot be strictly controlled because some precipitate is inevitably lost during the washing stages.

The wet ferrophase was blended with 7 mL of 25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide (N(CH3)4OH) and homogenized using a mechanical stirrer for 60 min at 500 rpm. Tetramethylammonium hydroxide acted as a stabilizing agent, preventing the agglomeration of the iron oxide nanoparticles. This is crucial for maintaining their magnetic properties and allowing them to be uniformly dispersed in different media such as aqueous solutions or organic solvents.

Subsequent to the experimental procedure, the morphology and diameter of the TMA-IONPs were ascertained through analysis of SEM and TEM images captured by a Hitachi HD2700 CFEG STEM device (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The instrument was con-figured to operate at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV, endowed with electron imaging capability. Diluted nanoparticle suspensions were deposited onto 400-mesh copper grids coated with carbon and allowed to air-dry prior to imaging.

The vibrational spectrum was acquired employing the ATR-FTIR technique, utilizing a Brucker—ALPHA device (Brucker, Karlsruhe, Germany). This non-destructive method employed a ZnSe crystal for data collection. The spectral resolution was set to 4 cm−1, and measurements were performed at ambient temperature (22 °C), encompassing the spectral range from 600 to 4000 cm−1.

Experimental design

Forty intact corn caryopses per sample (treated and control), similar in size, color, and free of visible defects, were placed in sterile glass Petri dishes (diameter 100 mm) on filter paper moistened with 15 mL of a TMA-IONP aqueous suspension at one of the six tested concentrations: 7.6, 15.2, 22.8, 30.4, 38.0, and 45.6 µg/mL. Seeds were germinated under controlled laboratory conditions at 23.0 ± 0.5 °C in complete darkness for 72 h. Seeds were considered germinated when the primary root (radicle) reached 2–3 mm in length.

After germination, the seedlings were kept in Petri dishes throughout the experiment. Starting from the first day post-germination, each dish was supplemented daily with 12 mL of freshly prepared TMA-IONPs suspension at the corresponding concentration for seven consecutive days. No replacement or removal of the previous solution was performed, and the seedlings were not rinsed to maintain continuous exposure conditions. All nanoparticle suspensions were prepared fresh each day to prevent oxidation and ensure colloidal stability.

Corn seedlings were maintained in a controlled climate chamber under standardized environmental conditions: a temperature of 23.0 ± 0.5 °C, a 14/10 h light/dark cycle, and 70% relative humidity. The control samples were treated identically, except that deionized water was used instead of the nanoparticle suspension.

Biological assays

The calculation of the germination percentage (GP) was based on the formula described in relationship (1), which was proposed by Dehnavi et al.14.

where n is the total number of seeds used per sample and Gs is the number of germinated seeds per sample after the treatment.

The measurements of seedling lengths, which were carried out after seven days of growth, were taken with great care using a ruler with a precision of 1 mm. The moisture content of the fresh tissue samples was determined using a MAC210 infrared thermobalance (RADWAG, Poland) at 105 °C with a precision of 10–3%.

The effect of TMA-IONPs on chlorophyll levels, depending on the concentration of nanoparticles in the culture medium, was investigated. Approximately 0.1 g of fresh tissue from each sample was ground and homogenized in 5 mL 90% acetone in the presence of low quantities of MgCO3 and CaCO3. The mixture was centrifuged and filtered. The pigment extract was diluted with 90% acetone to a final volume of 10 mL. The quantification of chlorophyll in fresh tissue was performed using spectrophotometric methods with the aid of a SPECORD 200 Plus UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena, Germany) equipped with 1 cm quartz cells. Spectrophotometric readings were taken at wavelengths of 630 nm, 647 nm, 664 nm, and 691 nm15. Ritchie’s Formulas (2)-(4) 15 were employed to calculate the chlorophylls’ concentration, which was expressed in milligrams per gram of fresh weight (mg/g).

where, Chl a is concentration of chlorophyll a, Chl b is concentration of chlorophyll b and TC is total chlorophyll’s concentration.

The Chlorophyll Stability Index (CSI) was calculated using Eq. (5), as out-lined by Pandiyan et al.16. This index provides a measure of plant resilience to adverse stress conditions.

The activity of catalase (CAT) in corn leaves extracts was determined according to the method of Luck17. Briefly, the extract was mixed with 3 mL of 2 mM H2O2 in phosphate buffer pH 7.0, and the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm was measured using the SPECORD 200 Plus UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). Enzyme activity was quantified in units per assay. One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to reduce the absorbance by 0.05.

The activity of peroxidase activity (POD) in corn leaves extracts was undertaken utilizing the protocol described by Reddy et al.18. Briefly, the extract was treated with 3 mL of 0.05 M pyrogallol and 0.5 mL H2O2, and the change in absorbance at 430 nm was monitored. Enzyme activity was expressed in units, with one unit representing the change in absorbance per minute at 430 nm.

Cytogenetic analysis

Furthermore, an experiment was conducted to assess the genotoxicity of TMA-IONPs towards corn seeds. For this experimental phase, 20 intact corn caryopses (for treated samples and a non-treated control sample) were allowed to germinate on moistened filter paper in plates in an incubator under controlled conditions at 24 ± 0.5 °C in complete darkness. In the test plate, 15 mL of an aqueous solution of TMA-IONPs, with six different concentrations of TMA-IONPs (7.6, 15.2, 22.8, 30.4, 38.0, and 45.6 µg/mL) was added, while the control sample was allowed to germinate under identical environmental conditions using 15 mL of distilled water. For cytogenetic analysis, two germinated caryopses with roots measuring 1–2 cm in length were chosen three days after germination. Root tips were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (1 glacial acetic acid/3 absolute ethanol; v/v) for 24 h, followed by storage in 70% ethanol at 4 °C. The staining process involved softening the root tips in a 1:1 solution of 37% HCl and distilled water for 25 min and then placing them in a modified carbol-fuchsin dye19 in a refrigerator. Five microscope slides were prepared for each variant using the squash technique20 with individual root tips from each germinated corn caryopsis. The dark root tip was sliced into three thin sections, which were then crushed on a slide and covered with a drop of 45% acetic acid21. A single operator analyzed a minimum of 2000 cells and over 40 microscopic fields for each prepared slide using a Euromex IS 1153-EPL microscope (40 × objective, Euromex Optics, Arnhem, Netherlands). Relevant abnormal cells were photographed using a CMEX-18000-PRO digital camera and the Euromex ImageFocus Alpha software (ver. × 64). The quantitative parameters, mitotic index (MI) and chromosomal aberration index (AI), were calculated following21, as:

where TAC is total number of analyzed cells, TA is total number of abnormal cells and TDC is total number of divided cells).

Statistical analysis

Each experimental sample consisted of forty sound seeds from a single gene pool. For each experimental sample, two replicates were prepared. The average plant lengths and standard deviations were computed for every batch of test seeds. Every batch of plantlets had its confidence interval assessed using the Student t-test at the 95% confidence level. Using a certain weight from whole fresh green masses acquired for each experimental sample, all biochemical analyses were performed in triplicate. The findings were displayed as mean ± standard deviation. A difference was deemed significant if it was p < 0.05. Results from microscopic analyses of five slides for each experimental case (control and TMA-IONPs-treated samples) are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Descriptive statistical parameters were calculated for both MI and AI for each experimental sample. The statistical significance between the control and TMA-IONP-treated samples was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test to determine pairwise differences between treatment groups. Statistical significance was defined as a probability level of p < 0.05. Microsoft Excel 2016 and OriginLab software (vers. 2023b) were used to execute all statistical analysis and graph representation.

Results

Morphological and structural characterization of TMA-IONPs

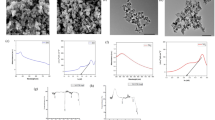

The morphology and physical dimensions of the TMA-IONPs were investigated using TEM and SEM. TEM and SEM images depicted the quasi-spherical shape of the nanoparticles (Fig. 1A, B), with a size distribution ranging between 4 and 19 nm (Fig. 1C). The histogram of the TMA-IONPs was constructed using values obtained from 220 nanoparticles in five different TEM images, which were measured using the ImageJ software (vers.1.8.0) and plotted using the OriginLab software (vers. 2023b). The fitting of the histogram was performed using a lognormal function, which provided the median value and standard deviation (10.78 nm and 2.18 nm, respectively).

We visually observed the status of the TMA-IONPs suspension’s stability by examining the eventual precipitation at the bottom of the bottle, according to the procedure reported by22. A slight deposit was noticed in the suspension after the first seven months. However, after a vigorous stir, the suspension appeared to remain stable for additionally two months. No further homogenization was observed in the tenth month, with clear phase separation.

Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMA) acts as a well-known capping agent, which is deposited on nanoparticles through surface–OH groups to minimize particle aggregation resulting from interparticle interactions23. The primary reason for the electrostatic repulsion effect is the charge of tetramethylammonium cations adsorbed on the particle surface in a water-based medium.

ATR-FTIR analysis was performed to characterize the surface of the synthesized TMA-IONPs suspension, as illustrated in Fig. 1D. The broad band at 3312.84 cm−1, assigned to the O–H stretching vibrations, could be mainly related to the presence of water from the aqueous suspension of TMA-IONP nanoparticles24. Additionally, an intense band at 1636.2 cm−1 was detected, which could be assigned to the H–O–H bending vibrations mode of water molecules. The ATR-FTIR spectrum of the TMA-IONPs sample also revealed a peak band at 1488.89 cm−1, assignable to the asymmetric methyl deformation mode (CH3) of TMA23. The band at 1396.48 cm−1 was assigned to the bending vibrations of the methyl groups25, indicating that tetramethylammonium ions, N(CH3)4+, were present on the surface of the nanoparticles. Additionally, the characteristic band of quaternary amine at 951 cm−1 originates from TMA used as a stabilizing agent in the synthesis of TMA-IONPs23,26. Skeleton vibrations of the ferrophase were observed at frequencies of approximately 650 cm−1. In addition, skeleton vibrations of the ferrophase would have been expected at frequencies lower than 600 cm−1, but the ATR-FTIR device that we used did not allow the observation of bands at frequencies lower than 600 cm−1. This IR band represents the stretching vibration of the Fe–O bonds in the crystalline lattices of iron-oxide nanoparticles (magnetite and maghemite)25. Other researchers obtained similar results23,24,27.

Phytotoxicity effects of TMA-IONPs on corn germination, seedling growth, chlorophyll level and enzymatic enzymes

Upon increasing the concentration of TMA-IONPs, a corresponding increase in germination percentage (GP) was observed. A 100% germination was found in samples treated with both concentrations, 7.6 and 38 μg/mL, of TMA-IONPs relative to the control sample, which exhibited a GP of 85% (Fig. 2). The application of TMA-IONPs to corn seeds appeared to elicit an increase in the moisture content of the green tissue of young plants, up to 89.39%, compared to the control, which displayed a moisture content of 88.52%. A significant enhancement in the seedling length was recorded across all concentrations of added TMA-IONPs suspensions, in contrast to the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between values of length at investigated TMA-IONPs concentrations. Notably, the mean length of the sample treated with a volume fraction of 38 μg/mL TMA-IONPs surpassed that of the other samples, exhibiting a 2.35-fold increase compared to the control. The relationship between the average seedling length and the concentration of the nanoparticle solution added to the culture medium was linear, with a slope of 1.41 and a correlation coefficient R-squared value of 0.828.

The average length of seedlings and germination percentage (GP) versus concentrations of TMA-IONPs. * statistic significant with p < 0.05 accordingly to Student test within groups and p < 0.01 accordingly to ANOVA single factor test between groups; ** statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

According to the graphical representations of photosynthetic pigments (Fig. 3), the concentration of chlorophylls exhibited a statistically significant increase in all samples treated with TMA-IONPs (p < 0.05). By adding a concentration of 38 μg/mL of TMA-IONPs suspension, the level of chlorophyll a level was 55% higher than that of the control sample. A comparable response was observed in the case of chlorophyll b content, which increased up to 63%, with the highest value corresponding to the 38 μg/mL concentration of TMA-IONPs solution. The total chlorophyll content increased for all TMA-IONP concentrations, reaching up to 53% (for 38 μg/mL) compared to that of the control sample. A similar trend was observed for chlorophyll a and b levels; a linear correlation (Chl a = 3.74⋅Chl b + 15.47) was observed between chlorophyll a (Chl a) and chlorophyll b (Chl b) levels, with a correlation coefficient R-squared value of 0.94.

Evolution of the chlorophyll content in corn plantlets according to -TMA-IONPs concentration (Chl a—chlorophyll a, Chl b—chlorophyll b, TC—total chlorophylls) (left axis) and the chlorophyll a/b ratio (Chl a/Chl b) (right secondary axis). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. * Statistically significant differences (p < 0.01), ** statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to the control.

Regarding the chlorophyll ratio (chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b) (Fig. 3), no statistically significant differences were observed compared with the control, except for the samples treated with 15.2 and 38 μg/mL TMA-IONPs. The highest chlorophyll a/b ratio (4.87) was recorded at 15.2 μg/mL, representing an 8% increase over the control (4.51), whereas the lowest value (4.28) was observed at 38 μg/mL. Although this concentration also showed the highest absolute chlorophyll b content, the a/b ratio remained within the physiologically acceptable range and did not suggest pigment imbalance or stress-induced chlorophyll b accumulation. These results indicate a coordinated enhancement of both chlorophyll a and b biosynthesis under nanoparticle treatment, rather than a shift toward a stress-associated pigment profile. Furthermore, the experimental results demonstrated a significantly higher chlorophyll stability index (CSI) for all TMA-IONPs concentrations investigated in this experimental study. The maximum CSI value was recorded in samples treated with 38 μg/mL TMA-IONPs (53% increase).

The TMA-IONPs treatment did not exhibit any inhibitory effects on the peroxidase (POD) activity of the corn leaves, in contrast to the control (Fig. 4). The most significant increase in POD activity (up to 78%) was observed at a TMA-IONPs concentration of 30.4 μg/mL. An elevated level of POD activity facilitates the elimination of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) activity levels in corn plantlets versus TMA-IONP concentrations. Data are presented on two separate vertical axes: POD activity is shown on the left axis and CAT activity is represented on the right axis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. * Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05); ** statistically insignificant differences (p > 0.05) in relation to the control.

In comparison to the control, the catalase (CAT) activity of corn leaves was enhanced by TMA-IONPs treatment (Fig. 4), with the exception of the sample treated with the highest concentration of TMA-IONPs, where a significant decrease was observed (7.7 lower than the control). A substantial increase in CAT activity was noted in the sample treated with 30.4 μg/mL TMA-IONPs (7.5 times higher than the control). The significant increase in catalase (CAT) activity observed at 30.4 µg/mL TMA-IONPs could be a direct response to oxidative stress induced by the nanoparticles. At this concentration, the seedlings likely experienced an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) that triggered the activation of antioxidant enzymes, with catalase playing a key role in the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide. The 7.5-fold increase in CAT activity compared to that in the control suggests a robust defense mechanism aimed at mitigating oxidative damage. This response may indicate the ability of the plants to adapt to mild stress.

Regarding the aspect of the foliar surface of corn seedling on the 7th day of corn seedling growth in presence of iron oxide nanoparticles at varying concentrations, very small lesions were noticed at concentrations higher than 30.4 μg/mL. These lesions indicate the initiation of plant stress, which are potentially associated with oxidative stress or localized nanoparticle toxicity. The direct interaction between iron oxide nanoparticles and plant tissues, possibly through reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation or ionic imbalances, may have contributed to this visual damage, suggesting that concentrations > 30.4 μg/mL might surpass the capacity of plants to mitigate nanoparticle-induced stress.

Genotoxicity evaluation of germinated corn caryopses treated with TMA-IONPs

To assess changes in cell cycle progression within the apical meristem of the corn roots, the mitotic index (MI), the percentage of cells in each mitosis phase (prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase), and clastogenic effects, as measured by the chromosomal aberration index (AI), were evaluated. The frequency of each mitotic phase is shown in Fig. 5A. A general trend of increase was observed for prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase; with the most notable enhancement in the frequency of cells in prophase, from approximately 0.71% to 3.52%, and in the frequency of cells in metaphase, from approximately 0.66% to 2.18%. The highest values were recorded for the sample treated with 38 μg/mL of TMA-IONPs.

(A) The percentage of cells in each mitosis phase for all cells analyzed, according to different treatment with TMA-IONPs; PP—prophase, MP—metaphase, AP—anaphase, and TP—telophase. (B) Mitotic index (MI) and aberrations index (AI) in germinated corn caryopses treated with different TMA-IONPs concentrations (μg/mL). Data are mean ± standard deviation. * Statistically significant differences (p < 0.01), ** statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

The results on MI and AI indices are illustrated in Fig. 5B, indicating that the TMA-IONPs suspension as a germination substrate for seeds was capable of modifying mitotic division in root tip cells. Each index value (mean with error bar) represents the mean of five replicates (slides) for each experimental sample with standard deviation. All cytogenetic analysis results (MI and AI values) were statistically significant compared with the control, for all treated samples (p < 0.05).

TMA-IONPs with a mean size of 10.78 nm demonstrated the ability to stimulate mitotic division activity, with the mitotic index increasing for all TMA-IONPs concentrations, exhibiting a 4.5-fold increase at 38 μg/mL TMA-IONPs compared to the control. For all TMA-IONP concentrations, a low level of chromosomal aberrations was observed, with an increase in the mitotic aberration index from approximately 0.13 in the control sample to 1.81% for the highest concentration of nanoparticle treatment, suggesting that the TMA-IONP sample is relatively safe and non-genotoxic. The results revealed various chromosomal abnormalities, including laggards, stickiness, vagrant chromosomes, ring chromosomes, chromosome gaps, interchromatin bridges, and C-mitosis at different levels of treatment. Overall, aberrations increased with increasing TMA-IONP concentrations compared with the control. Photomicrographs of some relevant abnormal cells observed during microscopic analyses are shown in Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs of some relevant abnormal cells observed during the microscopic analyses: (a) chromosome gaps at anaphase; (b) apolar anaphase with vagrant chromosomes; (c, j, k, n, s) laggard chromosomes in metaphases; (d) anaphase with star effect and chromosome gaps; (e) anaphase with multiple interchromatin bridges and vagrant chromosome; (f, h) anaphase with ring chromosomes; (g) sticky metaphase with laggard chromosomes; (i) C mitosis; (l) anaphase with two bridges and fragments; (m) broken interchromatin bridges in anaphase; (o) anaphase with interchromatin bridge; (p) anaphase with vagrant chromosome; (r) sticky anaphase with fragments. The circles and arrows indicate particularly, the specific chromosomal aberrations.

Correlation analysis yielded a Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient of 0.714 (p < 0.01) and a Pearson’s coefficient of 0.888 (p < 0.01) between cytogenetic indices (M.I. and A.I.), indicating a positive correlation. For the largest volume fraction utilized in this experiment, a tendency toward a decreased mitotic index was observed compared to the other values; however, this value remained higher than that obtained for the control sample.

Laggard chromosomes in metaphase constituted one of the primary abnormal cell types observed in the present study. Additionally, vagrant chromosomes represent another frequently observed aberration. These abnormal cells are classified as physiological aberrations. It appears that the TMA-IONPs solutions used as germination substrates for seeds may influence centromere division.

Furthermore, a linear positive correlation between the mitotic index and seedling length was observed, with a fitted line yielding a slope of 8.52 and a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.903. This strong association suggests a close relationship between cell division and plant growth under the influence of iron oxide nanoparticles. Correlation analysis yielded a Kendall’s tau correlation coefficient of 0.857 (p < 0.05) and a Pearson’s coefficient of 0.925 (p < 0.01) between the values of the mitotic index and seedling lengths. The mitotic index reflects the rate of cell division, with a higher index indicating an increased cellular proliferation. As corn seedlings develop, their elongation is primarily driven by rapid cell division in the meristematic regions, particularly in roots and shoots. The observed correlation implies that an increased frequency and rate of cell division correspond to enhanced seedling growth rates.

To assess the significance of differences between treatments, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test (p < 0.05) was performed. The results revealed that the 15.2 µg/mL TMA-IONPs treatment differed significantly from all other concentrations for Chl a, Chl b, TC, chlorophyll ratio, catalase (CAT), average seedling length, MI, and AI, except for peroxidase (POD), where significant differences were observed only at 22 and 30.4 µg/mL. Similarly, the 30.4 µg/mL treatment showed significant differences from all others for chlorophyll-related parameters, CAT activity, MI, and AI; in terms of seedling length, it differed only from 15.2 µg/mL, whereas for POD activity, significance was observed only when compared to 15.2 and 45.6 µg/mL. The 38 µg/mL treatment showed the most statistically distinct behavior, differing significantly from all other treatments for chlorophyll content parameters, chlorophyll ratio, CAT, MI, and AI; significant differences in seedling length were noted relative to 7.6, 15.2, and 45.6 µg/mL treatments, whereas POD activity showed no significant difference from other concentrations.

These results suggest that concentrations of 15.2, 30.4, and 38 µg/mL elicited specific physiological responses, with 38 µg/mL producing the most consistent and statistically significant changes across the majority of evaluated parameters. This clear statistical separation supports the hypothesis of a dose-specific, non-linear effect of TMA-IONPs, likely governed by hormetic dynamics and concentration-dependent modulation of redox and growth-related pathways.

Discussion

In recent decades, research in the field of nanotechnology has significantly increased, and the use of nanoparticles in various biological and agricultural applications has become a major area of interest. The rapid global population growth, climate changes and limitations of traditional agricultural practices have resulted in loss of plant nutrient supply. Nano-agricultural technology presents significant potential for enhancing crop growth, mitigating stress, and providing economic benefits with reduced environmental impacts. One of the essential agricultural crops is corn (Zea mays), which holds significant importance in both human and animal nutrition. Studying the effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on corn seeds and their potential effects on plant development is therefore a topic of interest and importance in the context of ensuring food security and agricultural sustainability. Iron plays a crucial role in plant development, because it is essential for both plant productivity and product quality. Iron homeostasis is a significant determinant of photosynthetic efficiency in higher plants28. Consequently, it is imperative to develop efficient and environmentally sustainable nanofertilizers that can be used in agricultural applications.

Numerous studies have investigated the influence of iron oxide nanoparticles on plants, particularly corn, by utilizing culture substrates or soil for seedling development after seeds germination29,30,31. In this study, corn seeds germination as well as the resulting seedlings growth were performed under controlled environmental conditions and exclusively in the presence of aqueous solutions of TMA-IONPs at varying concentrations. Alternative iron sources were not used. In contrast to previous studies of our group, this experiment employed only low concentrations of TMA-IONPs in the culture medium for the seedlings in their early development stage.

The stabilization of iron-oxide nanoparticles plays a crucial role in producing suspensions that are resistant to aggregation within biological environments. Certain researchers have emphasized the significance of the stabilizing agent employed in nanoparticle surface coating, considering its uptake and accumulation by the plant32. Tetra-methylammonium hydroxide (TMA) has emerged as an effective stabilizing agent for iron-oxide nanoparticles23. Suspensions stabilized with TMA exhibited remarkable stability for long time, compared to those treated with alternative stabilizers, including citric acid, tartaric acid, aspartic acid, and hyaluronic acid, as employed by our research team. However, the current body of literature lacks extensive investigation into the application of TMA as a stabilizing agent for iron-oxide nanoparticles, specifically in the context of plant studies. Mori et al.33 examined the ecotoxicological effects of TMA on various aquatic organisms as well as their synergistic interactions with potassium iodide. The research revealed that TMA exhibited moderate toxicity towards the microcrustacean Daphnia magna and low toxicity to the fish species Oryzias latipes. Notably, the study found that TMA had a minimal ecologi-cal impact on algal and bacterial populations.

The findings of this investigation, which employed TMA-IONPs of a larger average diameter (over 10 nm of mean size) compared to previous studies (mean size of approximately 8 nm), suggest an inverse relationship between nanoparticle size and toxicity. Smaller iron-oxide nanoparticles demonstrate enhanced surface reactivity, attributable to their greater surface-area-to-volume ratio34. This may enhance their interactions with plant tissues and cellular membranes. Root exposure to nanoparticles allows their translocation within plants via symplastic or apoplastic routes35,36,37. The former involves intercellular movement through plasmodesmata35,36, whereas the latter utilizes the cell walls and extracellular spaces of adjacent cells37. However, the presence of biological barriers with varying dimensions impedes facile nano-particle translocation. Thus, the dimensions of iron-oxide nanoparticles play a crucial role in determining their capacity for translocation within plant structures.

Our study examined the effect of various concentrations of TMA-IONPs suspension, utilized as growth substrates, on corn seedling development. Concentrations up to 45.6 mg/L exhibited a stimulatory influence on seed germination and seedling growth. This finding aligns with previous research that has consistently demonstrated the positive effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on the development of various plant species. Alkhatib et al.38 conducted a study investigated the effects of iron oxide nanoparticles of varying sizes and concentrations on tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum). The results indicated that the smallest nanoparticles, with a size of 5 nm, induced the most significant adverse effects at all concentrations, such as reduced shoot height. In contrast, plants treated with larger nanoparticles (10 and 20 nm) exhibited fewer morphological changes than the control group38. Plaksenkova et al. (2019) found that garden rocket (Eruca vesicaria) exposed to nanoparticles at concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 mg/L exhibited significantly increased shoot lengths39. Similar stimulatory effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on the growth of Ocimum basilicum seedlings were observed, with concentrations up to 3 mg/L positively influencing seedling length40. Kokina et al.41 demonstrated that the addition of iron oxide nanoparticles at concentrations up to 4 mg/L enhanced the length of yellow medick (Medicago sativa) seedlings. Furthermore, studies on barley (Hordeum vulgare) seedlings revealed improved growth when exposed to 17 mg/L or concentrations of up to 250 mg/L iron oxide nanoparticles35. Iron oxide nanoparticles, with dimensions ranging from 20 to 35 nm, at concentrations up to 1 mg/L, significantly enhanced plant growth parameters of Chinese fringe flowers (Loropetalum chinense), including shoot count, plant length, and leaf number per explant, compared to conventional iron fertilizers42. Furthermore, iron oxide nanoparticles, with a mean size of 40 nm, increased germination and growth at low concentrations, thereby enhancing tolerance and anti-oxidant enzyme activities in evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) plants43. Research conducted by Iannone et al.44 elucidated the physiological effects of citric-acid-coated iron oxide nanoparticles with a mean size of 10 nm on Triticum aestivum L. in hydroponic environments. Their findings revealed that a concentration of 10 mg/L enhanced the root elongation and accelerated germination. In a separate study, Li et al.11 observed that iron oxide nanoparticles at a concentration of 20 mg/L not only promoted growth in Zea mays but also led to substantial increases in germination and vigor indices, with improvements of 27% and 39%, respectively. Additionally, Wang et al.45 reported growth-promoting effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on Curcumis melo plants, although they noted that the nanoparticles did not translocate to the aerial parts of the plants.

Furthermore, our results demonstrated that TMA-IONPs suspension employed as growth substrates for corn seedling development enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity (CAT and POD) and chlorophyll biosynthesis. Chlorophyll performs essential functions in light harvesting and energy transfer during photosynthesis. Iron is a crucial element for chlorophyll synthesis. Iron deficiency in plants may lead to decreased chlorophyll levels, resulting in reduced photosynthetic rates. Moreover, iron is a significant component of cellular redox systems and serves as a cofactor for various antioxidant enzymes such as catalase and peroxidase. Iron oxide nanoparticles have the potential to induce oxidative stress through ROS production, thereby activating antioxidant defense mechanisms in plants. Other researchers have obtained comparable results regarding the effect of iron oxide nanoparticles on the development of various plant species. Wang et al. (2015) reported that iron oxide nanoparticles at 20 mg/L on Citrullus lanatus demonstrated increased antioxidant enzymes and chlorophyll contents46. Iannone et al.47 observed elevated chlorophyll levels and CAT activity in soybean and alfalfa seedlings treated with iron oxide nanoparticles coated with citric acid at concentrations up to 100 mg/L. CAT activity in ryegrass and pumpkin seedlings increased significantly when exposed to iron oxide nanoparticles coated with polyvinylpyrrolidone, with a mean size of 25 nm and concentrations up to 100 mg/L48. Similarly, Hu et al.49 observed increased CAT and POD activities compared to the control in Citrus maxima seedlings under iron oxide nanoparticle treatment at concentrations of up to 100 mg/L. Li et al.50 reported that the presence of iron oxide nanoparticles, with a mean size of 9 nm and concentrations up to 50 mg/L, resulted in significantly higher CAT and POD activities in watermelon plants. Iron oxide nanoparticles with a mean size of 20 nm and concentrations of up to 50 mg/L increased the chlorophyll content in Pseudostellaria heterophylla plants51. Furthermore, enhanced growth and chlorophyll content were observed in Cannabis sativa plants treated with iron oxide nanoparticles with a mean size of 17 nm and concentrations of up to 500 mg/L52.

After seven days of growth in the presence of aqueous solution of iron oxide nanoparticles, very small lesions were noticed on the foliar surface of plants exposed to concentrations > 30.4 μg/mL. The emergence of small spots on corn leaves after seven days of growth in an aqueous solution of iron oxide nanoparticles may be attributed to the oxidative stress induced by these nanoparticles. Iron oxide likely generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can result in localized cellular damage, manifesting as necrotic spots on leaves. The observed increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD), in these plants further corroborates the hypothesis that plants experience oxidative stress. These enzymes constitute part of the defense mechanisms of plants to neutralize ROS and mitigate further damage, although visible staining on the leaves suggests that stress may have exceeded these protective responses in certain areas. This indicates that while plants activate their antioxidant defenses in response to nanoparticle exposure, prolonged or excessive stress could lead to damage that surpasses their repair capacity. Furthermore, given that the growth medium consisted exclusively of a nanoparticle solution, it is probable that the plants experienced nutrient deficiencies. Soil or nutrient-rich media provide essential macro and micronutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium. In the absence of these nutrients, plants may encounter difficulties in executing normal physiological processes, such as photosynthesis, root development, and protein synthesis. Although the plants might have had excess iron from the iron oxide nanoparticles, the deficiency of other nutrients could have limited growth. This could explain why despite the increased chlorophyll A content and mitotic activity, visible signs of stress, such as leaf spots, appeared.

In addition to the observed effects of TMA-IONPs on corn seedling development, the data suggest a potential hormetic response to nanoparticle treatment. Hormesis is characterized by a dose–response relationship, where low doses of a substance can stimulate biological processes, while higher doses result in toxicity or inhibition. In the present study, we observed that low concentrations of TMA-IONPs (up to 45.6 mg/L) promoted seed germination, seedling growth, and antioxidant enzyme activity. However, at higher concentrations, oxidative stress was induced, as evidenced by the increased antioxidant enzyme activity and visible leaf lesions. This suggests that the corn seedlings initially benefited from the nanoparticles, but at elevated concentrations, the beneficial effects were outweighed by the cellular damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. These findings align with the concept of hormesis, in which the beneficial effects of low-dose nanoparticle exposure are followed by detrimental effects at higher doses. The hormetic response observed in this study could be attributed to the activation of stress response pathways at low nanoparticle concentrations, which may enhance plant resilience and growth. However, at higher concentrations, overwhelming oxidative stress and potential nutrient imbalances appear to trigger adverse effects, such as reduced growth and leaf damage. This dual nature of the response highlights the importance of optimizing nanoparticle concentrations for agricultural applications to harness the beneficial effects without causing harm to plants.

In this study, the observed biphasic response to TMA-IONPs treatment, with a maximum increase in antioxidant enzyme activity at 30.4 µg/mL and a peak in other growth parameters at 38 µg/mL, can be attributed to the complex nature of plant stress responses. At lower concentrations, nanoparticles may induce mild oxidative stress, stimulating the activation of antioxidant enzymes as a protective response. This is in line with the hormetic dose–response model, where low doses of stressors enhance certain biological functions. However, at higher concentrations, nanoparticles may optimize nutrient bioavailability, activate growth-promoting pathways, or provide other benefits that lead to improved growth parameters, such as increased chlorophyll content and seedling length.

The positive effects of low concentrations of TMA-IONPs on corn seedlings may be explained by a combination of mechanisms. A key contributing factor appears to be hormesis, a biphasic dose–response phenomenon whereby low doses of a stressor stimulate biological functions, while higher doses inhibit them. In this context, exposure to low nanoparticle concentrations may induce moderate oxidative stress, leading to the activation of antioxidant defense systems and signaling pathways that enhance growth and resilience. Additionally, iron is a critical micronutrient for plants and acts as a cofactor in numerous enzymatic processes, including chlorophyll biosynthesis and peroxidases and catalases. The high surface area and small size of the nanoparticles likely enhance Fe bioavailability and facilitate interaction with root cells. These complementary effects may collectively account for the improved germination rate, seedling vigor, and enzymatic activity observed in our experimental setup.

Plant cells possess appropriate mechanisms for iron storage in the form of complex combinations known as phyto-siderophores; externally originating Fe3⁺ ions are likely to be reduced to Fe2⁺ ions, which are significantly more soluble in water. In this context, the supply of iron ions from internalized iron-oxide nanoparticles can support plant growth in the experimentally designed arrangement, which no other nutrients were added. Furthermore, excess iron can initiate cytotoxicity mechanisms due to catalytic Fenton reactions mediated by free iron ions, resulting in reactive oxygen species that overwhelm cellular defense mechanisms dedicated to mitigating peroxidative damage.

There is limited evidence in the literature regarding the genotoxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles in plants, particularly Zea mays. This species is widely recognized as an exceptional genetic model for the assessment and monitoring of environmental mutagens53. Extensive research about nanoparticles genotoxicity has been conducted on the effects of silver nanoparticles54,55. Our findings demonstrated that TMA-IONPs possessed the capacity to enhance mitotic division activity, with a dose-dependent effect on the mitotic index observed for concentrations up to 38 μg/mL TMA-IONPs. Chromosomal aberrations were observed at higher concentrations of TMA-IONPs; however, the percentage of these aberrations was low, with a maximum of only 1.82% at the highest concentration. This suggests that while some genotoxic effects may occur, they do not significantly affect other plant growth parameters, such as germination or seedling development. The low occurrence of chromosomal aberrations could indicate a mild stress response, but overall plant growth and physiological processes appear to remain largely unaffected by the TMA-IONPs treatments. The concentrations of nanoparticles used in this study seemed to be below the threshold that would induce substantial toxicity. The observed positive effects on germination, seedling growth, and antioxidant enzyme activity suggest that the beneficial effects of TMA-IONPs outweigh the mild genotoxicity observed at higher concentrations.

Previous investigations by our research group on corn seeds, utilizing various types of iron oxide nanoparticles stabilized with different agents, demonstrated a stimulatory effect of relatively low concentrations of nanoparticles on mitotic division and a relatively minor induction of chromosomal aberrations that increased with increasing treatment doses56,57. Comparable results were observed when Lens culinaris seeds were subjected to treatment with Si nanoparticles, with the mitotic index exhibiting a significant increase at concentrations up to 50 mg/L58. In the case of corn seeds treated with Mn3O4 nanoparticles, a substantial increase of 35.5% in the mitotic index was noted59. Similarly, enhanced mitotic activity at low concentrations was observed in corn seeds treated with petroleum-based magnetic fluid60. Conversely, contrasting outcomes have been reported for the treatment of corn seeds with other types of magnetic nanoparticles. Ruffini et al.61 observed a decrease in mitotic activity when corn seeds were treated with TiO2 nanoparticles. Analogous results were obtained by Gantayat et al.62 for Allium cepa treated with iron oxide nanoparticles, indicating a potential genotoxic effect at concentrations starting at 100 mg/L. Singh et al.63 also reported a decreased mitotic index for Allium cepa treated with iron oxide nanoparticles at concentrations up to 20 mg/L.

As a result of the statistical analysis performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test (p < 0.05), it was observed that TMA-IONPs at concentrations of 15.2, 30.4, and 38 μg/mL induced distinct and statistically significant responses across multiple physiological and biochemical parameters. Among these, the 38 μg/mL treatment consistently differed from both the control and most of the other treatments, particularly in terms of chlorophyll content, catalase activity, mitotic index, and aberration index. These findings support the existence of a dose-specific, nonlinear effect of TMA-IONPs, in which moderate concentrations may enhance plant function. This is consistent with a hormetic model of action, where low-to-intermediate levels of stress induced by nanoparticles stimulate protective pathways, including redox signaling and cell division processes, ultimately promoting plant growth and resilience up to a threshold beyond which toxicity may occur.

Furthermore, in this experimental investigation, we analyzed plant tissues from samples treated with nanoparticles using TEM imaging; however, the images obtained did not provide conclusive evidence regarding the internalization of the nanoparticles. It is possible that the nanoparticles were primarily adsorbed on the root surface rather than internalized, especially at higher concentrations. Subsequent studies will focus on refining electron microscopy analyses to further investigate the potential internalization of iron-oxide nanoparticles and the mechanisms underlying their interaction with plant tissues.

Conclusions

This study concludes that iron oxide nanoparticles coated with TMA, having a mean size of 10.78 nm, at low concentrations up to 45.6 μg/mL enhanced germination, seedling growth, antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase and peroxidase), chlorophyll synthesis, and mitotic activity when aqueous solutions of nanoparticles were utilized as the substrate for corn seed germination and subsequent seedling development. Mild toxic effects appeared to manifest at nanoparticle concentrations exceeding 30.4 μg/mL. The percentage of induced chromosomal aberrations was less than 2%. Although the results obtained under controlled laboratory conditions demonstrate that low concentrations of TMA-IONPs can stimulate early seedling growth, antioxidant activity, and chlorophyll biosynthesis, their practical use as nanofertilizers remains to be confirmed. These low-cost nanoparticle formulations may offer promising prospects for sustainable crop enhancement; however, further investigations are needed to validate their performance under field conditions. Such studies should also include comparative trials with conventional fertilizers and cost–benefit analyses that consider production costs, environmental impacts, and agricultural yield improvements.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Linsinger, T. et al. Requirements on measurements for the implementation of the European Commission definition of the term “Nanomaterial” in Publications Office of the European Union (Luxembourg, 2012).

Ali, S., Mehmood, A. & Khan, N. Uptake, Translocation, and consequences of nanomaterials on plant growth and stress adaptation. J. Nanomater. 2021, 6677616. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6677616 (2021).

Hoang, S. A. et al. Metal nanoparticles as effective promotors for maize production. Sci. Rep. 9, 13925. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50265-2 (2019).

Włodarczyk, A., Gorgon, S., Radon, A. & Bajdak-Rusinek, K. Magnetite nanoparticles in magnetic hyperthermia and cancer therapies: challenges and perspectives. Nanomaterials 12, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12111807 (2022).

Aazami, M. A., Rasouli, F. & Ebrahimzadeh, A. Oxidative damage, antioxidant mechanism and gene expression in tomato responding to salinity stress under in vitro conditions and application of iron and zinc oxide nanoparticles on callus in-duction and plant regeneration. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 597. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03379-7 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Effect of surface coating and organic matter on the uptake of CeO2 NPs by corn plants grown in soil: Insight into the uptake mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 225–226, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.05.008 (2012).

Arami, H., Khandhar, A., Liggitt, D. & Krishnan, K. M. In vivo delivery, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8576–8607. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CS00541H (2015).

Wang, X., Xie, H., Wang, P. & Yin, H. Nanoparticles in plants: Uptake, transport and physiological activity in leaf and root. Materials 16, 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16083097 (2023).

Sun, X. D. et al. Magnetite nanoparticle coating chemistry regulates root uptake pathways and iron chlorosis in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120(27), e2304306120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2304306120 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Enhanced germination and growth of alfalfa with seed presoaking and hydroponic culture in Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2023, 9783977. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9783977 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Uptake, translocation and physiological effects of magnetic iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles in corn (Zea mays L.). Chemosphere 159, 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.05.083 (2016).

Răcuciu, M. & Creangă, D. TMA-OH coated magnetic nanoparticles internalized in vegetal tissue. Rom. J. Phys. 52(3–4), 395–402 (2007).

Goodarzi, A., Sahoo, Y., Swihart, M. T. & Prasad, P. N. Aqueous ferrofluid of citric acid coated magnetite particles. Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 789, N6.6.1 (2004).

Rajabi Dehnavi, A., Zahedi, M., Ludwiczak, A., Cardenas Perez, S. & Piernik, A. Effect of salinity on seed germination and seedling development of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) genotypes. Agronomy 10, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10060859 (2020).

Ritchie, R. J. Universal chlorophyll equations for estimating chlorophylls a, b, c, and d and total chlorophylls in natural assemblages of photosynthetic organisms using acetone, methanol, or ethanol solvents. Photosynthetica 46, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-008-0019-7 (2008).

Pandiyan, M. et al. Studies on performance of drought tolerant genotypes under drought and normal conditions through morpho, physio and biochemical attributes of blackgram (Vigna Mungo L.) and green gram (Vigna Radiata L.) Int. J. of Adv. Res. 5, 489–496. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/3176 (2017).

Luck, H. Catalase. In Method of Enzymatic Analysis (ed. Bergmeyer) 885–894 (Academic Press, 1965). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-395630-9.50158-4.

Reddy, K. P., Subhani, S. M., Khan, P. A. & Kumar, K. B. Effect of light and benzyladenine and desk treated growing leaves: II. Changes in the peroxidase activity. Cell Physiol. 26, 984 (1995).

Gamborg, O. L. & Wetter, L. R. Plant Tissue Culture Methods (Saskatoon, Sask: National Research Council of Canada, Prairie Regional Laboratory, 1975).

Singh, R. J. Plant Cytogenetics 3rd edn. (CRC Press, 2016).

Truta, E., Vochita, G., Zamfirache, M. M., Olteanu, Z. & Rosu, C. M. Copper-induced genotoxic effects in root meristems of Triticum aestivum L. cv. Beti. Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 8, 83–92 (2013).

Baki, A., Remmo, A., Löwa, N., Wiekhorst, F. & Bleul, R. Albumin-coated single-core iron oxide nanoparticles for enhanced molecular magnetic imaging (MRI/MPI). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6235 (2021).

Andrade, Â. L., Valente, M. A., Ferreira, J. M. & Fabris, J. D. Preparation of size-controlled nanoparticles of magnetite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 324, 1753–1757. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMMM.2011.12.033 (2012).

Cheng, F. Y. et al. Characterization of aqueous dispersions of Fe(3)O(4) nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Biomaterials 26(7), 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.016 (2005).

Cornell, R. M. & Schwertmann, U. The Iron Oxides. Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Use 2nd edn, 253–296 (Wiley, 2003).

Ouasri, A., Rhandour, A., Dhamelincourt, M. C., Dhamelincourt, P. & Mazzah, A. Vibrational study of (CH3)4NSbCl6 and [(CH3)4N]2SiF6. Spectrochim Acta A 58(12), 2779–2788 (2002).

Dani, R. K., Schumann, C., Taratula, O. & Taratula, O. Temperature-tunable iron oxide nanoparticles for remote-controlled drug release. AAPS PharmSciTech 15, 963–972. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-014-0131-x (2014).

Briat, J. F., Dubos, C. & Gaymard, F. Iron nutrition, biomass production, and plant product quality. Trends Plant Sci. 20(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2014.07.005 (2015).

Yousaf, N. et al. Characterization of root and foliar-applied iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe2O3, Fe2O3, Fe3O4, and bulk Fe3O4) in improving maize (Zea mays L.) performance. Nanomaterials 13, 3036. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13233036 (2023).

Yan, L., Li, P., Zhao, X., Ji, R. & Zhao, L. Physiological and metabolic responses of maize (Zea mays) plants to Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sci Total Environ. 718, 137400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137400 (2020).

Velásquez, A. A., Urquijo, J. P., Montoya, Y. A., Susunaga, D. M. & Villanueva-Mejía, D. F. Evaluation of the application of suspensions of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with quaternized chitosan and phosphates on yellow maize and chili pepper plants. Interactions 245, 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10751-024-01843-y (2024).

Judy, J. D., Unrine, J. M., Rao, W., Wirick, S. & Bertsch, P. M. Bioavailability of gold nanomaterials to plants: Importance of particle size and surface coating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 8467–8474. https://doi.org/10.1021/es3019397 (2012).

Mori, I. C. et al. Toxicity of tetramethylammonium hydroxide to aquatic organisms and its synergistic action with potassium iodide. Chemosphere 120, 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.011 (2015).

Ali, A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, applications, and challenges of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 9, 49–67. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSA.S99986 (2016).

Tombuloglu, H., Slimani, Y., Tombuloglu, G., Almessiere, M. & Baykal, A. Uptake and translocation of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles and its impact on photosynthetic genes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Chemosphere 226, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.075 (2019).

Raliya, R. et al. Quantitative understanding of nanoparticle uptake in watermelon plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01288 (2016).

González-Melendi, P. et al. Nanoparticles as smart treatment-delivery systems in plants: Assessment of different techniques of microscopy for their visualisation in plant tissues. Ann. Bot. 101(1), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcm283 (2008).

Alkhatib, R., Alkhatib, B., Abdo, N., Al-Eitan, L. & Creamer, R. Physio-biochemical and ultrastructural impact of (Fe3O4) nanoparticles on tobacco. BMC Plant Biol. 19(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1864-1 (2019).

Plaksenkova, I. et al. Effects of Fe3O4 nanoparticle stress on the growth and development of rocket Eruca sativa. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2678247. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2678247 (2019).

Elfeky, S., Mohhamed, M., Khater, M., Osman, Y. A. H. & Elsherbini, E. Effect of magnetite nano–fertilizer on growth and yield of Ocimum basilicum L. Int. J. Indig. Med. Plants 46, 1286–1293 (2013).

Kokina, I., Plaksenkova, I., Jermalonoka, M. & Petrova, A. Impact of iron oxide nanoparticles on yellow medick (Medica-gofalcata L.) plants. J. Plant Interact. 15, 1–7 (2020).

Asadi-Kavan, Z., Khavari-Nejad, R. A., Iranbakhsh, A. & Najafi, F. Cooperative effects of iron oxide nanoparticle (α-Fe2O3) and citrate on germination and oxidative system of evening primrose (Oenthera biennis L.). J. Plant Interact. 15(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2020.1774671 (2020).

Babalı, N., Alaylı, A., Nadaroğlu, H. & Demir, T. Synthesis of nano iron oxide and investigation of its use as a fertilizer ingredient. INJIRR 6(1), 6–10 (2022).

Iannone, M. F., Groppa, M. D., de Sousa, M. E., van Raap, M. B. F. & Benavides, M. P. Impact of magnetite iron oxide nanoparticles on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) development: Evaluation of oxidative damage. Environ. Exp. Bot. 131, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.07.004 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. The impacts of γ-Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the physiology and fruit quality of muskmelon (Cucumis melo) plants. Environ. Pollut. 249, 1011–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.119 (2019).

Wang, M., Liu, X., Hu, J., Li, J. & Huang, J. Nano-ferric oxide promotes watermelon growth. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 6, 160–167. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbnb.2015.63016 (2015).

Iannone, M. F. et al. Magnetite nanoparticles coated with citric acid are not phytotoxic and stimulate soybean and alfalfa growth. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 211, 111942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.111942 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Physiological effects of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles on per-ennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and pumpkin (Cucurbita mixta) plants. Nanotoxicology 5, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.3109/17435390.2010.489206 (2011).

Hu, J. et al. Comparative impacts of iron oxide nanoparticles and ferric ions on the growth of Citrus maxima. Environ. Pollut. 221, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.11.064 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Physiological effects of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles to-wards watermelon. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 5561–5567. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2013.7533 (2013).

Li, J., Ma, Y. & Xie, Y. Stimulatory effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the growth and yield of Pseudostellaria heterophylla via improved photosynthetic performance. HortScience 1, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15658-20 (2021).

Deng, C. et al. Effects of iron oxide nanoparticles on phenotype and metabolite changes in hemp clones (Cannabis sativa L.). Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 16, 134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-022-1569-9 (2022).

Grant, W. F. The present status of higher plant bioassays for the detection of environmental mutagens. Mutat Res. 310(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0027-5107(94)90112-0 (1994).

Ghosh, M. et al. In vitro and In vivo genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. Mutat. Res. 749, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrgentox.2012.08.007 (2012).

Abdelsalam, N. R. et al. Genotoxicity effects of silver nanoparticles on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) root tip cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 155, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.02.069 (2018).

Răcuciu, M. Iron oxide nanoparticles coated with aspartic acid and their genotoxic impact on root tip cells of Zea mays embryos. Rom. Rep. Phys. 72, 701 (2020).

Răcuciu, M. & Creangă, D. Cytogenetical changes induced by β-cyclodextrin coated nanoparticles in plant seeds. Rom. J. Phys. 54(1–2), 125–131 (2009).

Khan, Z. & Ansari, M. Y. K. Impact of Si engineered nanoparticles on seed germination vigour index and genotoxicity assessment via DNA damage of root tip cells in Lens culinaris. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9029.1000218 (2018).

Sun, G. et al. Mn3O4 nanoparticles alleviate ROS-inhibited root apex mitosis activities to improve maize drought tolerance. Adv Biol (Weinh) 7(7), e2200317. https://doi.org/10.1002/adbi.202200317 (2023).

Pavel, A. & Creanga, D. E. Chromosomal aberrations in plants under magnetic fluid influence. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 289, 469–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2004.11.132 (2005).

Ruffini Castiglione, M., Giorgetti, L., Geri, C. & Cremonini, R. The effects of nano-TiO2 on seed germination, development and mitosis of root tip cells of Vicia narbonensis L. and Zea mays L. J. Nanoparticle Res. 13, 2443–2449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-010-0135-8 (2011).

Gantayat, S., Nayak, S. P., Badamali, S. K., Pradhan, C. & Das, A. B. Analysis on cytotoxicity and oxidative damage of iron nano-composite on Allium cepa L. root meristems. Cytologia 85(4), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1508/cytologia.85.325 (2020).

Chandra Sekhar Singh, B. Toxicity analysis of hybrid nanodiamond/Fe3O4 nanoparticles on Allium cepa L. J. Toxicol. 202, 5903409. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5903409 (2022).

Funding

Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through research grant LBUS-IRG-2022-08.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“M.R. design of the study; M.R., S.O. and L.B-T. methodology and investigations; M.R., S.O. and L.B-T. analyzing of data; M.R. writing original draft of manuscript and editing; M.R. and S.O. writing review of the manuscript; M.R. funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Răcuciu, M., Barbu-Tudoran, L. & Oancea, S. Evaluation of phytotoxicity and genotoxicity of TMA-stabilized iron-oxide nanoparticle in corn (Zea mays) young plants. Sci Rep 15, 18951 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03872-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03872-1