Abstract

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) allows the non-invasive detection of interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs). Clinical MEG analysis in epileptic patients traditionally relies on the visual identification of IEDs, which is time consuming and partially subjective. Automatic, data-driven detection methods exist but show limited performance. Still, the rise of deep learning (DL)—with its ability to reproduce human-like abilities—could revolutionize clinical MEG practice. Here, we developed and validated STIED, a simple yet powerful supervised DL algorithm combining two convolutional neural networks with temporal (1D time-course) and spatial (2D topography) features of MEG signals inspired from current clinical guidelines. Our DL model enabled a successful identification of IEDs in patients suffering from focal epilepsy with frequent and high amplitude spikes (FE group), with high-performance metrics—accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity all exceeding 85%—when learning from spatiotemporal features of IEDs. This performance can be attributed to our handling of input data, which mimics established clinical MEG practice. Reverse engineering further revealed that STIED encodes fine spatiotemporal features of IEDs rather than their mere amplitude. The model trained on the FE group also showed promising results when applied to a separate group of presurgical patients with different types of refractory focal epilepsy, though further work is needed to distinguish IEDs from physiological transients. This proof-of-concept study represents a first step towards the use of STIED and DL algorithms in the routine clinical MEG evaluation of epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizure1. It affects people of all ages and has neurobiological, cognitive, psychological and social consequences. While pharmacological treatments work successfully in most patients, approximately one-third of them suffer from refractory (i.e., drug-resistant) epilepsy2. These patients are possible epilepsy surgery candidates and must therefore undergo a presurgical evaluation aiming at delineating as precisely as possible the epileptogenic zone.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) contributes to this evaluation, mainly by allowing the non-invasive detection and localization of interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs)—subclinical events occurring between seizures3,4—which help to localize the epileptogenic zone5,6. Clinical MEG analysis of patients with epilepsy traditionally relies on the visual identification of IEDs by an experienced clinical magnetoencephalographer, who inspects both IED sensor time courses and spatial topographies along with their source localization, usually by equivalent current dipole (ECD) modeling7,8. This approach is highly time consuming (on average 8 h per patient9) and partially subjective (notwithstanding existing guidelines10). The development of efficient data-driven, automatic approaches to IED detection would represent a major advance in clinical MEG practice. Several proposals based on unsupervised algorithms have been explored, e.g., Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM), with limitations regarding detection specificity or full automation11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

In the last years, supervised deep learning (DL) algorithms emerged as novel automatic approaches18,19,20,21. These methods are mainly based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) extracting temporal features of IED waveforms from MEG signals, and then supplemented with somewhat ad-hoc techniques for the subsequent spatial localization of epileptic events, e.g., splitting sensor channels into different brain regions18,21, classification and segmentation networks19, or graph convolutional networks20. While promising, none of these approaches performed well enough to be incorporated into routine clinical MEG practice.

Here, we hypothesized that a reliable, high-performance DL algorithm should combine both temporal (spiking waveform) and spatial (dipolar magnetic pattern) features used by clinical magnetoencephalographers to visually identify and select epileptiform discharges in MEG signals10. For that purpose, we designed STIED, a simple but powerful DL algorithm for the SpatioTemporal detection of focal IEDs. We trained and validated STIED models in a cohort of 10 school-aged children with focal epilepsy (FE) selected based on frequent, high-amplitude, and isolated IEDs arising mainly from the perisylvian areas to which MEG is highly sensitive22. These cases thus provide an excellent first case study to benchmark DL models. The sample size was not an issue here as we used a Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) approach to estimate the performance of the model when applied to new patient data. This approach is particularly appropriate for small datasets, especially when model accuracy is more important than the computational cost of training23. To test our hypothesis, we compared the performances of three CNN algorithms: a temporal model (1D-CNN applied to a MEG waveform) encoding temporal features only, a spatial model (2D-CNN applied to a magnetic field pattern) encoding spatial features only, and a spatiotemporal model integrating both aspects simultaneously. We show that all models lead to high-performance IED detection metrics (accuracy, specificity and sensitivity)—with the spatiotemporal model being the most effective—thanks to the combined encoding of IED amplitude with temporal waveform morphology and spatial dipolar magnetic pattern. As further proof of concept, we provide a preliminary test of the generalizability of the spatiotemporal model directly on 12 presurgical patients with refractory focal epilepsy (RFE), i.e., the typical clinical target of MEG diagnostic evaluation in epilepsy.

Methods

Participants and data acquisition

Participants

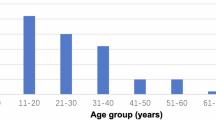

We trained and validated our DL models using a small dataset of 10 children (age: 5–11 years; 5 females and 5 males) suffering from FE, most of them from self-limited epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes (SeLECTS), with a high number of visually detected IEDs (VDS-IED) marked by a clinical magnetoencephalographer (O.F.). The trained spatiotemporal DL model was also tested on a cohort of 12 patients suffering from RFE, including 3 children (age: 6–15 years; 2 females and 1 male) and 9 adults (age: 19–48 years; 1 female and 8 males). See Table 1 for clinical characteristics of both FE and RFE groups. All FE patients and their legal representative signed a written informed consent after approval by the ULB–Hôpital Erasme Ethics Committee. The ULB–Hôpital Erasme Ethics Committee and RFE patients gave approval for the research use of clinical MEG data acquired in the context of their non-invasive presurgical evaluation. The experimental protocols for MEG data acquired in FE and RFE patients were approved by the ULB–Hôpital Erasme Ethics Committee. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data acquisition

Participants underwent MEG scanning during a seizure-free wakeful rest of at least 5 min in sitting position with their eyes open for the FE group, and one hour of recording in supine position to trigger sleep for the RFE group (see24 for details on the clinical MEG protocol). Data were recorded using a whole-scalp-covering MEG system (Neuromag Triux; MEGIN, Helsinki, Finland; 0.1–330 Hz band-pass, 1 kHz sampling rate) installed in a lightweight magnetically shielded room (Maxshield, MEGIN; see25 for details). The 306-channel sensor array combines 102 magnetometers and 204 planar gradiometers. Head movements were tracked by four coils whose position relative to fiducials (nasion and tragi) was digitized beforehand (Fastrack, Polhemus, Colchester, Vermont, USA), along with at least 300 face and scalp points for co-registration with a structural brain 3D T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) (Intera, Philips, The Netherlands).

MEG data preparation

The overall pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1 (upper panels A, B and C).

Schematic representation of the overall deep learning approach. (A) Raw MEG data. (B) MEG preprocessing. (C) Machine learning (ML) preprocessing. (D) Training and testing steps conducted to develop the three DL models (temporal, spatial, spatiotemporal) following the LOOCV design. (E) Prediction step in new raw MEG data, resulting in a binary yes/no (spike/non-spike) prediction for the patient data left out in the LOOCV design.

MEG preprocessing

We followed standard denoising steps of MEG data, i.e., signal space separation to correct for environmental magnetic interferences and head movements (Maxfilter v2.2.14, MEGIN, with default parameters26) and ICA (FastICA27) of band-filtered data (0.5–45 Hz) to remove physiological artifacts (eye blinks and cardiac activity)28. The resulting data were further band-filtered between 4 and 30 Hz and temporally segmented into 200 ms-long non-overlapping windows. This length was chosen to enable full inclusion of isolated IEDs, whose typical duration range from 50 to 100 ms29.

Spatial/temporal feature extraction

Input data for training/testing of subsequent DL models was extracted from each window by applying principal component analysis (PCA) separately to the 204 planar gradiometer signals and to the 102 magnetometer signals. In each case, a principal component (PC) is associated with a magnetic topography that encodes its spatial distribution across sensors (magnetometers, size 102 channels \(\times\) 1; gradiometers, 204 channels \(\times\) 1) and a waveform that encodes how this magnetic pattern evolves in time within the window (size 1 \(\times\) 200 time samples). Here, we elected to focus on the time course of the first PC of gradiometers, i.e., the combination of all 204 gradiometer signals that explained the largest fraction of temporal variance in the window, and on the spatial topography of the first PC of magnetometers, i.e., the magnetic field pattern that explained the largest fraction of spatial variance within the window. The latter topographies were then converted into 2D images by a fourth order polynomial interpolation over a 60 \(\times\) 60 pixel grid using the open-source software FieldTrip30. This splitting of gradiometers/magnetometers to extract temporal/spatial features broadly reproduces the visual IED identification procedure typically followed by our clinical magnetoencephalographers; the higher signal-to-noise ratio of gradiometers yields a cleaner visualization of MEG time courses10,31 (notwithstanding lesser sensitivity to deep IED activity in, e.g., mesiotemporal epilepsy32) whereas magnetometers show higher sensitivity to dipolar magnetic patterns33 (as well as to deep IEDs32). Extracting a single waveform or image per window also allowed to reduce the size and redundancy of input data, the size and complexity of our DL network models, and the computational load of model training. Since this data reduction could miss potentially relevant, low-variance IED features included in higher-order PCs, we also used second PCs as inputs to DL models and checked whether they bear predictive power for IED detection. Each of these PC data were further standardized per subject.

Machine learning preprocessing of training data (FE group)

The windowed data associated to FE patients was further prepared for model training. Each window was labeled according to a binary classification (‘Spike’/‘Non-spike’) depending on whether or not it contains an annotated VDS-IED17 (see Fig. 1, panel D). Over the resulting labeled dataset, we performed a threefold data augmentation. First, each ‘Spike’ window was shifted 15 times to the past and future by 7 ms steps, hence allowing to train our DL models independently of the precise IED timing within a window. The number of 30 replicas per ‘Spike’ window was determined through trial and error to optimize the performance. Then, we randomly removed ‘Non-spike’ windows to achieve a balanced training dataset. Second, we further augmented the dataset spatially by rotating magnetic topographical images four times at 90° intervals, so as to train our DL model independently of the precise IED dipole position and orientation. Last, we added sign-inverted data given the sign ambiguity of PCA27. The resulting training dataset size was 200 time samples \(\times\) NT = 30,000 windows for the temporal model and 60 \(\times\) 60 pixels \(\times\) NS = 75,000 windows for the spatial model. The spatiotemporal model was trained on the same NS windows than the spatial one, leading to a dataset size of 200 \(\times\) NS waveforms and 60 \(\times\) 60 pixels \(\times\) NS images where some images were associated to the same waveform.

Model architectures

The architecture of our three DL models is illustrated in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. All these models were implemented using the Tensorflow library35 and run on a laptop equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800H processor, 40 GB RAM memory and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 graphic card. Of note, non-trainable hyperparameters were chosen by exploring the space generated by the combination of different number of CNN layers (1, 2, or 3), CNN filters (8, 16, 32, or 64), dense layers (1, 2, or 4), and dense-layer neurons (8, 16, 32, 64).

Temporal model (1D-CNN)

In the temporal model, the gradiometric PC waveform of a window is passed through three successive blocks made of a 1D convolutional layer followed by dropout and maxpooling layers (Fig. 2). The output was then flattened and fed to a two-layer decision block. Each convolutional layer has a different number of filters (16, 32, 64), a leaky rectified linear unit (ReLU) as activation function, and subsequent dropout layer (probability value 0.5) to prevent overfitting and maxpooling layer (pooling size 2) for downsampling. The decision block was composed of a dense layer with 16 neurons and ReLU activation functions, followed by a single neuron with sigmoid activation function providing a probability between 0 and 1 for a window to contain a spike. The final binary yes/no (‘Spike’/’Non-spike’) decision was based on a non-trainable probability threshold set to 0.5.

Spatial model (2D-CNN)

The model design to analyze spatial features was the same as for the temporal model, except that the inputs consisted here in images of magnetometric PC field pattern, so all convolutional layers were 2D (Fig. 3).

Spatiotemporal model (STIED)

To incorporate both temporal and spatial features in a genuinely spatiotemporal IED detection, we designed a model architecture that processes temporal and spatial inputs in parallel using the same 1D-CNN (Fig. 2) and 2D-CNN (Fig. 3) up to the first dense layer of their decision block. The feature vectors from the outputs of the temporal and spatial dense layers were downsampled (0.5 dropout), combined using weighted concatenation with one trainable scalar weight for the temporal features (\({w}_{t}\)) and one for the spatial features (\({w}_{s}=1-{w}_{t}\)), and finally fed to the exact same decision block than the one used in the temporal model described above (Fig. 4).

Spatiotemporal model (STIED). The input corresponds to both the gradiometric waveform and the magnetometric topography of a time window. The architecture incorporates both 1D-CNN and 2D-CNN up to their dense layer, an extra dropout, a weighted concatenation with trainable weights (\({w}_{t}\) and \({w}_{s}\)), and a common decision block (two dense layers).

Normalized and maximum amplitude models

Since IEDs are primarily high-amplitude events, we sought to examine whether our STIED models are merely driven by the gross amplitude of IEDs or if they learn subtler features. To do so, we isolated the effect of amplitude from other features by considering both classifiers independent of amplitude and classifiers that depend solely on amplitude. For amplitude-independent IED detection, we applied the same 1D-CNN, 2D-CNN, and STIED architectures on input data after amplitude normalization (NormAmplitude models). Normalization consisted in window-by-window division of data by the maximum amplitude (i.e., maximum amplitude of gradiometric PC waveform within the window for temporal features, maximum amplitude of magnetometric PC topography for spatial features). The specific importance of amplitude in IED detection, independently of other morphological features, was assessed using a simple deep learning classification model based on a multilayer perceptron (MaxAmplitude models). The input data for this model consisted in the maximum amplitude used for data normalization in NormAmplitude models. The perceptron was trained to determine the probability that a given window contained a spike, thereby enabling binary classification (probability threshold 0.5) based solely on amplitude. As above, three versions of the MaxAmplitude models were considered: a temporal one (using the maximum amplitude of gradiometric PC waveform), a spatial one (using maximum amplitude of magnetometric PC topography), and a spatio-temporal one (incorporating both maximum amplitudes as inputs). Each perceptron consisted in one hidden layer of 8 neurons (temporal and spatial models) or two hidden layers of 16 neurons (spatiotemporal model) with ReLU activation function and followed by an output layer of a single neuron with sigmoid activation function to produce a probability-like output.

Training and performance evaluation

Model training

Model training was performed using an Adam optimizer algorithm with a batch size of 128 windows, binary cross-entropy as loss function, and a reduced learning rate when loss stopped improving. As preliminary sanity check, we trained our models by randomly extracting 80% of the entire dataset for training and using the remaining 20% for testing. We did not observe overfitting and determined that 150 epochs/training steps were enough to reach a learning plateau in all models. For model performance evaluation, given that our dataset was composed of 10 patients, we performed a tenfold repeated LOOCV wherein all windows of 9 out of 10 subjects were used for training, and all windows of the remaining subject for testing. This allowed to evaluate model performance in a clinically oriented setup (i.e., generalizability to the inclusion of new patients with similar epilepsy) and inter-individual variability of performance metrics.

Performance metrics (FE group)

For each cross-validation iterate, we compared model window classification (yes/no) to the actual presence of VDS-IEDs (‘Spikes’/‘Non-Spike’) using accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity according to the standard expressions

Here, TP (true positive) stands for the number of positive model predictions that contain at least one VDS-IED, FP (false positive) the number of positive predictions that do not contain any VDS-IED, FN (false negative) the number of negative predictions that contain at least one VDS-IED, and TN (true negative) the number of negative predictions that contain no VDS-IED. In our tenfold LOOCV design, we evaluated these metrics per FE patient (i.e., applying to this patient models trained on the other nine patients), using both balanced test data (i.e., extracting an equal number of ‘Spikes’/‘Non-Spike’ windows from the test patient) as done in previous works18,20,21, or using the full, unbalanced test data as this corresponds to the realistic case of diagnosing a new patient. All performance data were analyzed quantitatively at the group level by computing their average and standard deviation across FE patients, and statistically using one-way ANOVA and paired t tests.

Comparison with unsupervised IED detection algorithms (FE group)

Previous work developed automated IED detection algorithm based on unsupervised machine learning algorithms such as ICA and HMM11,12,13,14,15,16,17. We sought to assess the added-value of our supervised DL approach by comparing its performance metrics with similar metrics derived from both the ICA and the amplitude HMM of MEG signals described in17 and tested on the same dataset of FE patients.

IED localization of predicted IEDs (RFE group)

As a final and more exploratory analysis, we examined the performance of our STIED model, trained in our FE group, on different patients with RFE. This provides a drastic test of model generalizability since this dataset differed in the type of epilepsy (RFE instead of FE), population (both children and adults instead of children only), and recording paradigm (sleep recordings instead of wakeful rest). This also allows to showcase a practical way to use STIED in new patients, and how to extract IED localization using further post-processing (since our deep learning classifiers only predict the presence or absence of IEDs within a window, without specifying its precise timing or localization). Specifically, the timing of each predicted IED was extracted as the highest-amplitude peak within the corresponding window (according to STIED). The brain source generator of each predicted IED was then localized as the global maximum of brain activity at the corresponding timing, imaged on patients’ MRI using noise-standardized Minimum Norm Estimation (see34 for implementation details). To give a sense of clustering of predicted IED location, we created an IED density map by binarizing each IED brain image (value 1 in a 5-mm voxel around the global maximum, zero elsewhere) and averaging them over all predictions in the patient so as to measure the fraction of IEDs predicted at this voxel (i.e., a voxel at 100% concentrates all predicted IEDs, whereas IEDs are spread over large areas in a map with low values). Although VDS-IEDs were not marked temporally as they were in the FE patients, we had access to the localization of VDS-IED brain sources reconstructed by a clinical magnetoencephalographer (X.D.T.) using ECD modeling, to which we compared our density map of STIED predictions. Of note, the lack of temporal annotations did not allow us to go beyond this qualitative comparison of localizations and evaluate quantitatively detection performance in RFE patients.

Results

We now report the detection performance of these supervised DL models and analyze the impact of using temporal, spatial, or spatiotemporal features. We also explore the validity of our data reduction, assess the relevance of IED amplitude and IED morphology in STIED and compare its performance to unsupervised detection algorithms (ICA and HMM). Then, we test the possible generalizability of STIED to another, unlabeled dataset of patients with RFE.

Detection performance of STIED in SeLECTS

The performance metrics for the three DL model types (temporal 1D-CNN, spatial 2D-CNN, spatiotemporal STIED) are summarized in Table 2 for balanced and unbalanced test data.

Impact of model type

Classification accuracy and specificity were consistently large whatever the model type, both for balanced and unbalanced test data (accuracy > 85%, specificity > 93%; mean over 10 cross-validation iterates), with no significant effect of model type (p > 0.12). So, all three DL models were equivalent in their ability to correctly predict VDS-IEDs. Sensitivity was on average larger for the temporal and spatiotemporal models (> 84%) than for the spatial model (75%), though this observation was not statistically significant due to large inter-subject variability in sensitivity (p > 0.26). This suggests that temporal features of IED waveforms are most useful to avoid false detections. Despite the absence of statistical effects, combining spatiotemporal features maximized all three performance metrics in the realistic setup of unbalanced test data (Table 2), indicating a slight but possible superiority of the STIED model, on which we shall focus hereafter. Interestingly, the trained weights \({w}_{t}\) and \({w}_{s}\) were both close to 0.5, showing that while STIED did not perform significantly better than the temporal 1D-CNN model, it effectively used both temporal and spatial features in its decision process.

Balanced vs. unbalanced metrics

The observation of similar performance metrics from balanced and unbalanced test data (Table 2) further advocates for the robustness of our DL algorithms. Specifically, the identical sensitivities (combined with consistently large specificities) indicate that all three models identified the same IEDs regardless of the amount of data without VDS-IEDs. In other words, DL model performance did not depend on IED frequency of the test patient. This conclusion was further supported by the absence of correlations between performance metrics and number of VDS-IEDs (Spearman correlation, |r| < 0.09; p > 0.36).

Impact of data reduction

The first PC used for data reduction explained significantly more data variance than the second PC of same windowed data (t test on window covariance eigenvalues, p < 3 × 10–6), but this does not preclude that the latter contains useful IED features. Figure 5a compares performance metrics (unbalanced test data) for our three DL models applied to the first vs. second PC. All metrics were significantly smaller when using the second PC in STIED (p < 0.01), with a particularly strong drop in mean sensitivity of 52%. The drop in accuracy and sensitivity were similarly significant in the temporal and spatial models (p < 0.05) but not in specificity (p > 0.11). Thus, the second PC contains remnant, low-variance features of IEDs excluded by our data reduction procedure, though these features are less effective at IED detection and are poorly specific to IEDs.

(a) Detection performance of the temporal, spatial and spatiotemporal models obtained from 1st-PC (purple) vs. 2nd-PC (yellow). (b) Detection performance of the three DL Full models (purple; top, 1D-CNN; middle, 2D-CNN; bottom, STIED) compared with NormAmplitude models encoding morphological and/or topographical IED features independently of their amplitude (green), and with MaxAmplitude models encoding the amplitude feature only (orange). All performance metrics are based on unbalanced test data. Bar plots show mean values across tenfold LOOCV, and vertical bars show standard errors. “*” indicates statistical significance (ANOVA, post-hoc t tests).

Contribution of IED amplitude

Figure 5b compares our DL models (Full) to similar models wherein the encoding of IED amplitude is explicitly precluded (NormAmplitude), and to a simple amplitude threshold model that solely encodes IED amplitude (MaxAmplitude). Remarkably, eliminating the amplitude feature did not alter performance metrics (unbalanced test data) for the three model types, except for a significant decrease of accuracy/specificity (p < 0.01; NormAmplitude vs. Full) in the spatial model (2D-CNN) and a marginal (non-significant; p = 0.09) decrease of sensitivity in the spatiotemporal model (STIED). Amplitude-based classification led to significantly lower accuracy/specificity (p < 0.004; except for spatial MaxAmplitude vs. NormAmplitude where p > 0.09) but higher sensitivity, though the latter effect was marginal in the original STIED model (p > 0.25). We conclude that IED amplitude is not effective in recognizing IEDs and plays a relatively marginal role in STIED. In other words, STIED is mostly driven by IED waveform morphology and dipolar topography.

Comparison with unsupervised classifications

Table 3 compares performance metrics of STIED (unbalanced test data) to those of two unsupervised detection algorithms (ICA and HMM) developed in a previous work and tested on the same dataset17. All approaches showed similar sensitivities (p = 0.67), but STIED was significantly more specific to IEDs than both supervised methods (< 55%; p < 2 × 10–9). This merely reflects the expected fact that the supervised DL algorithm learns from VDS-IEDs and thus follows closely the clinical magnetoencephalographer’s decision.

Generalizability of FE-group-trained STIED to RFE patients

As a final step, we sought to evaluate the performance of our STIED model, trained in our FE group, on 12 patients with RFE. Perhaps unsurprisingly, results were mitigated with only 2 patients reproducing exactly the location of IED events, 9 patients in which additional non-epileptiform events were detected besides the accurate location of VDS-IEDs, and 1 patient in which a cluster of VDS-IEDs was missed altogether.

Figure 6 illustrates these results by comparing the density map of predicted IEDs (Fig. 6, left) and ECD localization of VDS-IEDs (Fig. 6, right) in three patients. Figure 6a is representative of the successful cases where STIED co-localizes IEDs with VDS-IEDs. Both approaches were consistent with multifocal independent irritative zones, with the most active being posterior to the left frontal lesion. Figure 6b illustrates a case of partial success. Clinical analysis reported few VDS-IEDs, which were accurately identified by the STIED model. Nonetheless, Rolandic spikes in the centrotemporal area and sleep-related events in the occipital areas were also wrongly predicted, likely indicative of physiological transients10,36. Figure 6c illustrates a case of mitigated success. Clinical assessment revealed two active, independent irritative zones located at the left opercular/periinsular and ventral occipital regions, which might be part of a common epileptogenic network, but STIED missed the ventral occipital cluster of VDS-IEDs. We conclude that, while STIED trained on FE patients learned IED features that generalize to all patients with RFE, other types of epileptiform activities were not recognized (such as polymorphic waveform), while some forms of physiological activity were falsely detected.

Localization of STIED predictions and VDS-IEDs in selected RFE patients. Left panel: Density maps of IEDs predicted by STIED, representing the fraction of IEDs predicted at each voxel. Color scales are adjusted to maximal fraction in patient. Right panel: ECD localization of VDS-IEDs. Each white dot indicates the dipole localization of one IED detected by visual analysis of MEG signals. (a) Successful example of coincident localization (blue squares). (b) Partially successful example where non-epileptiform events (green squares) are detected, such as Rolandic and sleep physiological transients. (c) Mitigated example where a cluster of VDS-IEDs is missed (orange squares) in the left-occipital part. All MRIs are in neurological convention.

Discussion

The development of fully automated tools for the detection and localization of IEDs is a long-standing goal in the field of clinical epilepsy. Here, we introduced STIED, a simple yet effective DL solution for IED automatic detection in clinical MEG recordings. This is part of the global momentum that “artificial intelligence” bears in technology, not the least in medical fields—including neuroscience37,38 and clinical epilepsy39. In fact, STIED is not the first attempt in applying supervised DL to the evaluation of epilepsy with MEG18,19,20,21. Here, we aimed to design a computationally reasonable architecture that encodes both temporal and spatial features in a way analogous to how clinical magnetoencephalographers analyze their clinical MEG recordings 10. This allowed us to train our STIED model with high sensitivity and specificity, despite a relatively small training dataset, at least in the context of our FE group. We focused here on patients with FE, mainly SeLECTS, because their high IED amplitude and frequency yielded a relatively large count of IED events in a limited duration of MEG signals, which admittedly may have contributed to the efficient training of STIED at small dataset size. Interestingly, our results suggest that, after training, detection performance does not depend closely on IED frequency and thus could generalize to epileptic patients with scarcer interictal events. This contrasts with previous recent studies18,19,20 proposing DL-based IED detection, which showed a substantial drop in sensitivity to less than 50% when assessed with unbalanced compared to balanced test data20. While authors overcame this issue ad-hoc by adjusting the probability threshold at the end of their decision blocks (using a thresholding moving strategy to enhance performance18,19,20), one advantage of our DL models is that they showed high sensitivity without such adjustment. Still, the generalizability of our current version of STIED to other types of epilepsy such as RFE was partial, presumably because it does not capture sufficiently the variety of IED field patterns and waveform morphologies (which may be different in deep medial temporal epilepsy40 or changes as the type of epilepsy evolves with age41). This being said, this paper provides proof of concept for the effectiveness of the STIED model architecture. Future updates of STIED with a larger and more diverse training dataset are necessary to fully validate this DL solution and to widen its range of applicability. STIED could also be an efficient and fast approach to assess the spike-wave index (i.e., fraction of recording time showing spike-and-wave activity42), a key diagnostic element for some pediatric epileptic conditions (reaching up to 85% in our training dataset43).

The STIED architecture is the result of several trials not reported here. Regarding artificial neural network design, we quickly settled for a quite classical setup that combines 1D-CNN as done in previous works to analyze temporal signals44, 2D-CNN typical of spatial image processing45, and dense layers with sigmoid final neuron for classification. The number and size of layers were varied to maximize performance while minimizing complexity. In this endeavor, the identification of CNN inputs with relevant low-dimensional features amongst high-dimensional MEG data, proved key. We did so using a data reduction based on PCA that loosely follows what is done during clinical MEG visual analysis, i.e., extract IED waveform signals from gradiometers and images of IED dipolar patterns from magnetometers. This likely explains why STIED could learn from, and closely agree with, clinical magnetoencephalographers. One possible caveat of this procedure is that PCA can be dominated by large-amplitude transients such as electronic noise or physiological artefacts (e.g., ocular and cardiac magnetic fields) in time windows where they occur. This would likely be detrimental to STIED detection performance, at least for IED events simultaneous to noise artefacts. However, this possible issue was mitigated here altogether by MEG signal denoising prior to model training and testing. Another caveat of this data reduction was the exclusion of MEG features specific of, though poorly sensitive to, IEDs. Critically, it might also miss deep epileptiform activity, which would be subdominant in MEG recordings32. This limitation could be alleviated in future updates of STIED that would allow inputting multiple PCs, though at the moment the right number to use remains unclear. On the other hand, this strong data reduction allowed to train and run the model on affordable hardware, with high performance despite reasonable training times (about 4 h for 10 subjects with 5-min MEG recordings) and small processing time of new data (less than 30 s for 1 h MEG recording). This means that STIED can detect IEDs similarly to clinical magnetoencephalographers, about 300 time faster—again at least within our FE group.

Beyond sheer performance, we sought to partially reverse engineer the STIED model and investigate what features of MEG signals drive IED detection. Generally speaking, reaching a full interpretation of model decisions remains a difficult and fundamental issue in the field of DL. The scope of our interpretability analysis here was relatively restricted and focused specifically on the impact of amplitude and input data type (temporal, spatial, or spatiotemporal). A surprising finding is that the amplitude of IED waveforms—at first sight a primary gross characteristic of epileptiform activity—was not critical in the STIED decision process. In fact, IED amplitude alone was poorly specific of visually identified epileptiform activity. Interestingly, a similarly low specificity was found in unsupervised algorithms based on ICA and HMM, for which arguments were given for the hypothesis that false positive events actually correspond to genuine but small-amplitude IEDs unidentified by clinical MEG evaluation17. This illustrates a possible advantage of unsupervised models. On the other hand, STIED yielded a fully automated decision, whereas both ICA and HMM were semi-automated. Further, whether such small-amplitude events, unidentified by STIED too, represent IEDs or clinically irrelevant physiological events, remains to be fully clarified. In the current state of knowledge, a conservative approach may be warranted for clinical applications so STIED likely represents the best data-driven approach so far. In the future, it will be interesting to compare the outcome of STIED and unsupervised algorithms in other types of IED recordings, such as the ICA of MEG based on optically pumped magnetometers46 or the HMM of stereo-electroencephalography data47.

Our reverse engineering analysis also revealed that, while STIED does rely on both its spatial and temporal inputs (as we intended), the spatial features of IED magnetic topography bring at most a subtle added value to detection performance, compared with the temporal morphology of IEDs. In hindsight, this is likely because IED spiking waveforms are automatically accompanied with dipolar magnetic field patterns, so the latter do not add independent information to the former. Indeed, epileptiform spikes originate from bursts of hyperexcitable neurons within focal neural populations. In neocortical epilepsies (as was the case in our training group), focal excitation leads to post-synaptic current flows along apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons that are necessarily dipolar48. More generally, all sharp electrophysiological events—not only IEDs but also physiological transients typically occurring in Rolandic, supramarginal, and occipital areas10,36 as well as transient oscillatory bursts emerging in brain functional networks49,50,51—are focal and thus dipolar. Spatial features thus hardly distinguish sharp physiological events from IEDs, which presumably explains the poorer performance of the spatial DL model. Another, more technical implication is that data augmentation by rotation of topographical patterns should not be overdone. While we initially reasoned (following standard image recognition processing) that such rotations would improve model generalizability across patients by allowing more diverse IED localizations, during our trial phase we found that coarse 90° rotations used here worked better than finer rotations (e.g., at 12°, the sensitivity of the spatial DL model tended to increase slightly, but specificity dropped significantly, p < 0.03). Associating IEDs with too many dipolar patterns presumably renders DL models oversensitive to sharp physiological events. This aspect will require further consideration when updating STIED with a larger training dataset. On the other hand, including spatial features might help against false detections of spike-like artefacts that may arise in MEG signals with atypical dipolar patterns.

The problem of physiological confounds was somewhat alleviated by the inclusion of temporal features, yet physiological transients with spiking waveform morphology remain a critical challenge to overcome10,36 as they are detrimental to detection specificity. This was illustrated by the high rate of false detections, together with the accurate location of VDS-IEDs, when applying our current version of STIED to sleep recordings of 9 out 12 patients with RFE. Some physiological transients typically emerge during drowsiness and sleep 28, so a critical next step might be to include sleep recordings of healthy controls to help STIED learn to distinguish them from epileptiform activity.

Conclusion

In sum, we provided proof of concept that STIED is a promising DL solution for the automated detection of IEDs in focal epilepsy, though further validation is necessary before envisaging deployment in clinical routine. In future work, we intend to update the current version with a large-scale training dataset of labelled MEG recordings in patients with different types of epilepsies, including sleep recordings to discriminate physiological spikes. If expected improvements in model generalizability and detection specificity are confirmed, this would establish STIED as an invaluable tool to assist clinical magnetoencephalographers in getting a fast and accurate clinical evaluation of epilepsy from MEG recordings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author (R.F.M. or A.G.) on reasonable request. Data and codes will be made available on request after approval by institutional authorities (Hôpital Universitaire de Bruxelles and Université Libre de Bruxelles).

References

Fisher, R. S. et al. ILAE Official Report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia 55(4), 475–482 (2014).

Picot, M. C., Baldy-Moulinier, M., Daurès, J. P., Dujols, P. & Crespel, A. The prevalence of epilepsy and pharmacoresistant epilepsy in adults: A population-based study in a Western European country. Epilepsia 49(7), 1230–1238 (2008).

Kirsch, H. E., Robinson, S. E., Mantle, M. & Nagarajan, S. Automated localization of magnetoencephalographic interictal spikes by adaptive spatial filtering. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117(10), 2264–2271 (2006).

Kural, M. A. et al. Criteria for defining interictal epileptiform discharges in EEG: A clinical validation study. Neurology 94(20), e2139–e2147 (2020).

Panigrahi, M. & Jayalakshmi, S. Presurgical evaluation of epilepsy. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 3(1 SUPPL.), 74–81 (2008).

Feys, O. & De Tiège, X. From cryogenic to on‐scalp magnetoencephalography for the evaluation of paediatric epilepsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. (2023).

Bagic, A. I., Knowlton, R. C., Rose, D. F. & Ebersole, J. S. American clinical magnetoencephalography society clinical practice guideline 1: Recording and analysis of spontaneous cerebral activity*. (2011).

Ebersole, J. S. Magnetoencephalography/magnetic source imaging in the assessment of patients with epilepsy. (1997).

De Tiège, X., Lundqvist, D., Beniczky, S., Seri, S. & Paetau, R. Current clinical magnetoencephalography practice across Europe: Are we closer to use MEG as an established clinical tool?. Seizure 50, 53–59 (2017).

Laohathai, C., Ebersole, J. S., Mosher, J. C., Bagić, A. I., Sumida, A., Von Allmen, G. & Funke, M. E. Practical fundamentals of clinical MEG interpretation in epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 12, (2021).

Malinowska, U. et al. Interictal networks in Magnetoencephalography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35(6), 2789–2805 (2014).

Pizzo, F. et al. Deep brain activities can be detected with magnetoencephalography. Nat. Commun. 10(1), (2019).

Ossadtchi, A. et al. Automated interictal spike detection and source localization in magnetoencephalography using independent components analysis and spatio-temporal clustering. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115(3), 508–522 (2004).

Ossadtchi, A., Mosher, J. C., Sutherling, W. W., Greenblatt, R. E. & Leahy, R. M. Hidden Markov modelling of spike propagation from interictal MEG data. Phys. Med. Biol. 50(14), 3447–3469 (2005).

Seedat, Z. A. et al. Mapping Interictal activity in epilepsy using a hidden Markov model: A magnetoencephalography study. Hum. Brain Mapp. (2022).

Ye, S., Bagić, A. & He, B. Disentanglement of resting state brain networks for localizing epileptogenic zone in focal epilepsy. (2022).

Fernández-Martín, R. et al. Towards the automated detection of interictal epileptiform discharges with magnetoencephalography. J. Neurosci. Methods 403, (2024).

Zheng, L. et al. EMS-Net: A deep learning method for autodetecting epileptic magnetoencephalography spikes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39(6), 1833–1844 (2020).

Hirano, R. et al. Fully-automated spike detection and dipole analysis of epileptic MEG using deep learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41(10), 2879–2890 (2022).

Mouches, P., Dejean, T., Jung, J., Bouet, R., Lartizien, C. & Quentin, R. Time CNN and graph convolution network for epileptic spike detection in MEG data. (2023).

Zheng, L. et al. An artificial intelligence–based pipeline for automated detection and localisation of epileptic sources from magnetoencephalography. J. Neural Eng. 20(4), 046036 (2023).

Feys, O. et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in refractory insular epilepsy. Epilepsia (2023).

Bickel, P. et al. Springer Series in Statistics.

De Tiège, X. et al. Clinical added value of magnetic source imaging in the presurgical evaluation of refractory focal epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 83(4), 417–423 (2012).

De Tiège, X. et al. Recording epileptic activity with MEG in a light-weight magnetic shield. Epilepsy Res. 82(2–3), 227–231 (2008).

Taulu, S., Simola, J. & Kajola, M. Applications of the signal space separation method. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 53(9), 3359–3372 (2005).

Hyvärinen, A., Karhunen, J. & Oja, E. Independent component analysis. (2001).

Vigário, R. N. Independent component approach to the analysis of EEG and MEG signals. Acta Polytech. Scand. Math. Comput. Ser. 47(101), 589–593 (1999).

Khalid, M. I. et al. Epileptic MEG spikes detection using amplitude thresholding and dynamic time warping. IEEE Access 5, 11658–11667 (2017).

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E. & Schoffelen, J. M. FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, (2011).

Hari, R. & Puce, A. MEG - EEG Primer. (2023).

Enatsu, R. et al. Usefulness of MEG magnetometer for spike detection in patients with mesial temporal epileptic focus. Neuroimage 41(4), 1206–1219 (2008).

Wens, V. Exploring the limits of MEG spatial resolution with multipolar expansions. Neuroimage 270, (2023).

Wens, V. et al. A geometric correction scheme for spatial leakage effects in MEG/EEG seed-based functional connectivity mapping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36(11), 4604–4621 (2015).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. (2015).

Rampp, S. et al. Normal variants in magnetoencephalography. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 37(6), 518–536 (2020).

Badrulhisham, F., Pogatzki-Zahn, E., Segelcke, D., Spisak, T. & Vollert, J. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in neuroscience: A primer for researchers. Brain Behav. Immun. 115, 470–479 (2024).

Marblestone, A. H., Wayne, G. & Kording, K. P. Toward an integration of deep learning and neuroscience. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 10, (2016).

Lucas, A., Revell, A. & Davis, K. A. Artificial intelligence in epilepsy—applications and pathways to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 20(6), 319–336 (2024).

Feys, O. et al. On-scalp magnetoencephalography based on optically pumped magnetometers can detect mesial temporal lobe epileptiform discharges. Ann. Neurol. 95(3), 620–622 (2024).

Feys, O. et al. On-scalp magnetoencephalography for the diagnostic evaluation of epilepsy during infancy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 155, 29–31 (2023).

Aeby, A. et al. A qualitative awake EEG score for the diagnosis of continuous spike and waves during sleep (CSWS) syndrome in self-limited focal epilepsy (SFE): A case-control study. Seizure 84, 34–39 (2021).

O. Feys, P. Corvilain, A. Aeby, C. Sculier, N. Holmes, M. Brookes, S. Goldman, V. Wens, and X. De Tiège, “On-Scalp Optically Pumped Magnetometers versus Cryogenic Magnetoencephalography for Diagnostic Evaluation of Epilepsy in School-aged Children,” Radiology, (2022).

Kiranyaz, S., Avci, O., Abdeljaber, O., Ince, T., Gabbouj, M. & Inman, D. J. 1D convolutional neural networks and applications: A survey. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 151, (2021).

Li, Z., Liu, F., Yang, W., Peng, S. & Zhou, J. A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst 33(12), 6999–7019 (2022).

Feys, O. et al. Tri-axial rubidium and helium optically pumped magnetometers for on-scalp magnetoencephalography recording of interictal epileptiform discharges: A case study. Front. Neurosci. 17, (2023).

Feys, O. et al. Delayed effective connectivity characterizes the epileptogenic zone during stereo-EEG. Clin. Neurophysiol. 158, 59–68 (2024).

Hamalainen, M., Hari, R., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Knuutila, J. & Lounasmaa, O. V. Magnetoencephalography theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. (1993).

Hari, R. & Salmelin, R. Human cortical oscillations: a neuromagnetic view through the skull. Trends Neurosci. (1997).

van Ede, F., Quinn, A. J., Woolrich, M. W. & Nobre, A. C. Neural oscillations: Sustained rhythms or transient burst-events?. Trends Neurosci. 41(7), 415–417 (2018).

Coquelet, N., De Tiège, X., Roshchupkina, L., Peigneux, P., Goldman, S., Woolrich, M. & Wens, V. Microstates and power envelope hidden Markov modeling probe bursting brain activity at different timescales. Neuroimage, 247, (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fonds Erasme (Brussels, Belgium; Research Convention: « Les Voies du Savoir»). Odile Feys is supported by the Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l’Industrie et l’Agriculture (FRIA, Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS), Brussels, Belgium). Xavier De Tiège is Clinical Researcher at the FRS-FNRS (Brussels, Belgium). The MEG project at the Hôpital Universitaire de Bruxelles is financially supported by the Fonds Erasme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.F.M. and A.G. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, design and implementation of the algorithm, software, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization and writing (original draft, review and editing); O.F. contributed to data acquisition, clinical data analysis (localization of IEDs) and writing (review); E.J. contributed to data acquisition and writing (review); A.A. contributed to writing (review) and resources; C.U. contributed to writing (review) and resources; X.D.T. contributed to conceptualization, data acquisition and clinical data analysis (localization of IEDs), supervision, writing (review), resources and funding; V.W. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, supervision and writing (original draft, review and editing). X.D.T. and V.W. contributed equally to this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and consent to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Martín, R., Gijón, A., Feys, O. et al. STIED: a deep learning model for the spatiotemporal detection of focal interictal epileptiform discharges with MEG. Sci Rep 15, 21017 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03880-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03880-1