Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may impact outcomes in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score assesses cardiovascular risk post-ACS. This study evaluated whether incorporating the STOP-BANG score (a surrogate for OSA) enhances GRACE’s predictive ability. A total of 227 myocardial infarction (MI) patients were included, with 66 (29.07%) experiencing in-hospital cardiovascular events. Patients with events were older, predominantly male, and had worse clinical markers, including lower hemoglobin and ejection fraction and higher RDW, creatinine, CRP, and GRACE scores (p < 0.001). While STOP-BANG was higher in event patients, risk group classification was non-significant (p = 0.3). Three models were trained: (1) all selected features, (2) GRACE alone, and (3) GRACE + STOP-BANG. The Extra Trees Classifier performed best (ROC-AUC = 0.82). Adding STOP-BANG improved the F1-score, accuracy, and precision but had a non-significant effect on ROC-AUC. The decision curve analysis showed an increased net benefit when STOP-BANG was incorporated. Feature importance analysis ranked STOP-BANG highest in models, reinforcing its relevance. While this study showed that STOP-BANG improved risk stratification, further multicenter validation is needed to confirm its clinical utility in ACS risk models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) represent chronic conditions that impose considerable financial and non-financial burdens on both patients and governments1. A principal concern in these patients is the occurrence of other cardiovascular events following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or stroke. The rate of these events was as high as 23.3% in a study2. Furthermore, a comparison of the healthcare costs associated with the initial event and the costs associated with the secondary event showed a two-fold increase3, showing the importance of risk assessment in these patients regarding a post-MI cardiovascular event. For this purpose, some tools have been developed that use clinical features at the time of AMI to determine the high-risk patients. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score is the most widely accepted tool4.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an underdiagnosed sleep-disordered breathing. This condition is characterized by the partial or complete obstruction of the respiratory tract, leading to disrupted oxygenation, increased sympathetic activity, and oxidative stress5. Studies have shown that untreated OSA patients are at a higher risk for cardiovascular events after MI6,7. Although the golden standard for detecting OSA is polysomnographic evaluation, the STOP-BANG questionnaire is also a validated tool for risk stratification of patients8.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has recently become a significant method in data science and is increasingly impacting medical research9,10,11, characterized by a rapid rate of innovation. This development is partially driven by the significant increase in computational power and data accessibility. The recent utilization of machine learning (ML) algorithms is transforming data analysis in cardiovascular and respiratory medicine12,13,14. ML provides the capability to examine, choose, and incorporate extensive interrelated variables while identifying nonlinear dependencies (patterns) that enhance the optimization of classification and prediction tasks, surpassing the limitations of traditional statistics15.

The current study sought to implement and assess the efficacy of ML in integrating the STOP-BANG score with existing clinical variables and derived scores to identify whether the OSA risk score could enhance existing risk prediction tools for post-myocardial infarction cardiovascular events within the same hospital admission.

Methods and materials

Study design

The prospective observational study was conducted on patients presenting with either ST-elevation MI (STEMI) or non-ST-elevation (NSTEMI). This study followed the guidelines provided by the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences with the reference code of IR.MUMS.IRH.REC.1403.144. The research took place in Ghaem Hospital, Mashhad, Iran, from March 2024 to March 2025. The inclusion criteria were: (I) a minimum age of 18 and (II) duration between symptom onset and hospitalization < 48 h, and those under active OSA treatment were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian (s). The eligible patients were then assessed by the researchers for data collection. The patients received standard treatment for MI (either medical or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)) throughout the study period and were followed during hospitalization for their outcome.

Data collection

A data collection sheet was used encompassing fields for demographic (sex and age) and anthropometric (height, weight, and neck circumference) data. The patients were also enquired about their medical history of CVD, their medication, and risk factors for cardiovascular incidents. Furthermore, the laboratory reports of electrolytes and hematological indices were retrieved using patients’ records. The angiography (the culprit vessel and TIMI-flow) and electrocardiogram (MI type, STEMI localization) reports were also recorded on the data collection sheets. The patients received a score according to the GRACE scoring system. Using an online calculator, the GRACE score was calculated using age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, and Killip class16. Also, the patients were classified based on Killip classification. Furthermore, the patients were evaluated in terms of the STOP-BANG questionnaire items. The STOP-BANG tool assesses snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, body mass index, age, neck circumference, and male gender17, assigning one point per item for a total possible score of 0–8. and each received a score. Traditionally, the STOP-BANG score shows a low (0–2), intermediate3,4, or high5,6,7,8 risk for OSA. However, a later study proposing a modified risk stratification based on STOP-BANG showed enhanced specificity18. The patients in this study were categorized accordingly. The patients labeled as intermediate risk (a STOP-BANG score of 3–4) were thus categorized into high-risk in the presence of (a) a STOP score equal to or higher than two and (b) a BMI > 35 kg/m, a neck circumference > 40 cm, or male sex.

Outcomes

The definition of an outcome in this study was based on the occurrence of a cardiovascular event during the index hospitalization of the patients. These events included all-cause mortality, new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), re-infarction, worsening heart failure, ventricular arrhythmia, recurrent or refractory angina, cardiogenic shock, and stroke. The definition of AF requires the diagnosis of AF according to ICD-9 code 427.31 during the hospital stay19. Re-infarction was diagnosed according to the ESC/ACC committee definition20. Criteria for worsening heart failure included new-onset pulmonary edema or worsening signs/symptoms of heart failure necessitating changes in medical treatment or a need for mechanical ventilation. Refractory angina refers to chest pains lasting for longer than 48 h after PCI or those needing intensified medication. Cardiogenic shock was defined according to the Shock Trial21, and stroke was diagnosed in the case of a rapid onset of documented neurologic deficit lasting > 24 h or until death.

Machine learning

All the processes of data handling and model development in this study were conducted using Python 3.11, Jupyter Notebooks22, the SciPy 1.11.4, the Scikit Learn module 1.2.2, Pandas 2.1.4, NumPy 1.26.4, XGBoost 2.1.3, and LightGBM 4.5.0. The figures were plotted using Matplotlib 3.7.5 and Seaborn 0.13.2, and SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) 0.46.0 was used during feature selection.

We split the dataset into 70% training and 30% testing. All preprocessing steps, including imputation and scaling, in addition to feature-selection steps, including RFE and SHAP, were performed strictly on the training set. Specifically, we computed the median values (for SimpleImputer) and the robust-scaling parameters using only the training data and then applied those same parameters to the test data. During the preprocessing, missing values were imputed using SimpleImputer with “median” selected as the strategy for the continuous features due to the non-normal distribution of the data. The details of the missing values for the included features are shown in Table 1. Finally, to normalize the features’ range, RobustScaler was used on the training set. The present dataset was imbalanced; therefore, we used settings native to the used algorithms to address this issue rather than using oversampling methods.

Feature selection was balanced on technical measures and domain knowledge. Primarily, the features that were incorporated in GRACE and STOP-BANG were excluded. Then, Recursive Feature Elimination with five-fold cross-validation (using RandomForestClassifier) and Shapley values (using XGBoost Classifier) were used, and the features found important by both methods were then revised in terms of their relevance, ensuring alignment with domain knowledge. The final selected features were SPO2, CRP, hemoglobin, platelets, K, glucose, admission to PCI time, EF, culprit vessel, STOP BANG score, and GRACE score. The details of the features selected or removed based on technical measures or domain knowledge are shown in S1.

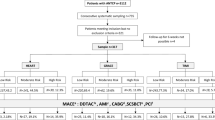

Models were trained over three sets from the selected features to address the research question. The first model was trained on all the features, the second model was trained on the GRACE score as the sole feature, and the third used GRACE and STOP-BANG scores. The dataset was split into 70% train and 30% test sets in each scenario using a constant method to ensure the three models were evaluated over the same individuals in the test set. The test set was left for the final step to minimize the risk of over/underfitting. Seven models were trained over the whole feature set, including the Extra Trees Classifier, Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Classifier (GBC), XGBoost, and LightGBM. However, given the simplicity of the other two models using STOP-BANG and GRACE scores, Logistic Regression was selected in these scenarios. In order to tune the hyperparameters for the selected ML algorithms, hyperparameter tuning was applied using five-fold cross-validation over the train set. The training phase was conducted using ten-fold cross-validation. In the whole set scenario, the best algorithm was selected according to the global generalizability and F1 scores (i.e., the Extra Trees estimator) and named the ML Model. Then, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision-Recall (PR) curves, along with the respective area under the curve (AUC), were plotted by comparing the three models. Also, decision curve analysis (DCA)23 was applied to compare the clinical usefulness of the models. Finally, the confusion matrix and the importance of the feature of the ML Model were plotted. The y-axis in a DCA plot is the net benefit (a balanced representation of the benefits of true positives and the costs of false positives), and the x-axis is the threshold probability at which a decision is made. For example, a conservative approach would be to take the intervention at lower threshold probabilities, which may come at the cost of higher false positives. Therefore, DCA plots are a practical way to show the net benefit of a given model or intervention. The decision curve of an intervention is compared with three main curves: (a) always act: this is when the intervention is made all the time, no matter the prediction; (b) never act: this is when no interventions are made, leading to no harm and no benefits; (c) Oracle, which is the perfect scenario with perfect predictions and thus, perfect net benefit. The decision curves for a model are therefore compared with these lines.

Statistical analysis

Due to the non-normal distribution of the data, continuous variables were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR). The study sample was divided based on the occurrence or absence of an event and then classified according to STOP-BANG risk categories. Then, the continuous and categorical features were compared between the groups within each classification using non-parametric tests. The improvement of models (from GRACE to GRACE + STOP-BANG) was assessed using the method proposed by DeLong’s test to compare the AUCs of curves24. Furthermore, the Brier scores were calculated for each of the three models.

Results

The present study included 227 patients eligible for enrollment; 66 (29.07%) patients had at least one cardiovascular event after their index MI during the hospitalization, while 161 (70.93%) did not. Unfortunately, four patients (1.76%) expired during their hospitalization. The baseline clinical features of the patients are compared between the two groups in Table 2. Noticeably, the patients with an in-hospital event had a significantly higher proportion of male patients, older age, and a longer hospitalization duration than those without an in-hospital event. Furthermore, these patients had significantly lower hemoglobin and higher RDW, creatinine, and CRP. The ejection fraction was significantly lower among the patients with an in-hospital event (p-value < 0.001), while the GRACE score was significantly higher in these patients (p-value < 0.001). Although the STOP-BANG scores were significantly higher among patients with an event (p-value < 0.001), categorizing subjects into three classes showed no significant differences between the two groups (p-value = 0.3) (Table 2).

The patients were also grouped based on the modified risk stratification of OSA. Accordingly, 57 (25.11%) were categorized as low-risk, 13 (5.72%) as intermediate, and 157 (69.16%) as high-risk patients. The GRACE score significantly differed between the groups and was highest in the group with intermediate risk for OSA (p-value = 0.02). The detailed comparison of these groups in terms of the assessed clinical features is shown in Table 3.

The Extra Trees Classifier was ranked first among algorithms using the whole features with a ROC-AUC = 0.82 (95% CI 0.66–0.92), F1 score = 0.66, precision = 0.75 and recall = 0.60. Training Logistic Regression using GRACE and STOP-BANG scores yielded ROC-AUC = 0.76 (95% CI 0.61–0.88), F1 score = 0.59, precision = 0.71, and recall = 0.50. Also, training Logistic Regression using GRACE scores only resulted in ROC-AUC = 0.70 (95% CI 0.58–0.82), F1 score = 0.57, precision = 0.52, and recall = 0.65. Comparing the GRACE + STOP-BANG and GRACE models shows improvement in ROC-AUC by 0.06, F1 score by 0.02, accuracy by 0.08, and precision by 0.19 (Table 4) and AP by 0.17 (Fig. 1); however, the results of DeLong’s test showed that the improvement in ROC-AUC was statistically non-significant. Furthermore, the ML Model had the lowest Brier score (0.14), while the GRACE + STOP-BANG model showed a slightly lower Brier score than the GRACE model.

Also, an independent model using all the selected features but excluding the STOP-BANG score was trained and compared with the ML Model to determine the effect of removing STOP-BANG from the model. The new ROC-AUC (0.78 (95% CI 0.63–0.90)) showed a non-significant reduction (p-value = 0.46) compared to the ML model. However, the Brier score of the ML model dropped by 0.02, the F1 score by 0.10, recall by 0.15, and accuracy by 0.03, while precision did not change.

The decision curve analysis showed higher benefits for the ML Model than the other two models. Also, applying the STOP-BANG risk score in the risk prediction of patients improved the new model’s net benefit over a moderately wide threshold probability range (0.4–0.7) (Fig. 2, Top). Also, retraining a model without STOP-BANG resulted in less net benefit across almost all threshold probabilities (Fig. 2, Bottom). These results showed that implementing STOP-BANG in the risk assessment of acute MI patients improved the net benefit of the models.

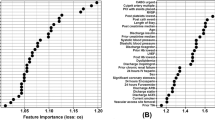

Figure 3 shows the confusion matrix for the first (Extra Trees Classifier) and second (Random Forest) ranked algorithms in ML Model training. Accordingly, the model missed 9 (45%) of the events in the test set. On the other hand, the feature importance plot for the Extra Trees Classifier showed that the STOP-BANG score was placed as the first important feature in the outcome prediction, while the GRACE score was placed fourth. The Random Forest algorithm also showed similar results; STOP-BANG was the first most important feature, while the GRACE score was among the least important features (Fig. 4). Moreover, the decision tree plot shown in Fig. 5 shows the importance of STOP-BANG, hemoglobin, and GRACE scores in categorizing patients. Accordingly, 84% of patients with STOP-BANG score ≤ 5.5, hemoglobin ≤ 11.85, and GRACE > 136.85 were patients with an in-hospital event.

Radial Decision Tree visualization with impurity-based node coloring: nodes represent decision points, colored by impurity (darker blue indicates higher impurity). Edge thickness highlights gain importance (thicker lines for higher gain), and node size corresponds to decision depth. The first and second percentages in each bracket show the portion of patients without and with events, respectively.

Discussion

The present study showed that implementing the STOP-BANG score to the conventionally assessed risk estimation of MI patients for an in-hospital cardiac event (i.e., the GRACE score) improved the model. The performance of the models was compared from different perspectives. This study showed that adding STOP-BANG to the GRACE model lead to higher f1, accuracy, and precision, which suggests that it makes overall better predictions and has a lower false positive rate. However, comparing the two models did not show a statistically significant improvement in the ROC-AUC, which might not be a reliable indicator of model performance in our study. The dataset in this paper was imbalanced, which limits the reliability of ROC-AUC25 for judging the model’s performance. On the other hand, evaluating the key determinants of the ML Model’s performance showed that the STOP-BANG score was the top significant contributor in different algorithms. Moreover, the use of DCAs in this study further showed the importance of STOP-BANG in identifying high-risk patients. DCA plots are particularly useful for practical decision-making when applying a model/intervention. DCA plots are designed to overcome the limitations of traditional statistics26, and this study showed a considerable drop in the Net Benefit of the ML Model when STOP-BANG was removed. Hence, these findings suggest that it still holds considerable value in predicting the target variable.

Several reports support the increased risk of post-MI events among patients with OSA27,28. Furthermore, a study showed the prognostic value of OSA severity due to nocturnal hypoxia29. The results of our study also highlighted the importance of OSA by using a valid risk estimating tool for this condition. Moreover, a meta-analysis has shown that OSA also contributes to increasing the risk of cardiovascular events in patients undergoing PCI30. OSA plays a significant role in the prognosis of CVDs through multiple pathophysiological mechanisms. OSA contributes to oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis and increase the risk of MI and stroke31. Additionally, OSA is strongly linked to cardiac arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation AF, worsening outcomes, and complicating rhythm control strategies. The intermittent hypoxia observed in OSA further exacerbates vascular damage by activating inflammatory pathways and increasing macrophage recruitment, ultimately leading to heightened coronary atherosclerosis and adverse cardiovascular events31,32.

Another study implementing ML models to explore the benefit of integrating STOP-BANG scores into GRACE scores showed performance improvement14. Unlike the present study, their results showed significant improvement in the ROC-AUC of the model after adding STOP-BANG. Our study was further imbalanced compared to them in terms of class imbalance. Furthermore, the sets of features used were different between the studies. Also, the distribution of patients in terms of STOP-BANG risk categories (low, moderate, and high) was considerably different between the two studies. Although both studies showed the importance of using STOP-BANG in better risk assessment of patients, the non-significant rise in ROC-AUC in the present study may be thus explained. Similar to the present study, they also showed that ejection fraction was among the significant features contributing to the model’s prediction. This is in line with the class I indication of echocardiography outlined in the management of non-STEMI patients, according to the 2014 AHA/ACC Guidelines33. Noteworthy, the death rate in the present study was 1.8%, comparable to other larger cohorts34,35.

Notably, smoking status was not significantly associated with events despite a previous study showing an association between smoking and atrial fibrillation36. While some reports describe a ‘smoker’s paradox’—with smokers appearing to have better short-term outcomes after MI—further analysis often reveals that any apparent benefit is ‘pseudo-protective.’ Indeed, longer-term data indicate that smoking increases the risk of recurrent MI and overall mortality37, and the acute post-MI setting and our in-hospital timeframe may have precluded the detection of such an effect in this cohort.

As part of this study, an external validation of the GRACE tool was conducted over a sample of patients. The results showed that the GRACE tool had a moderate discriminative ability over our population with an AUC of 0.70 (95% CI 0.58–0.82)38. As the tool was originally not developed over a population similar to the present study, suboptimal performance is expected. For example, a Pakistani study also showed a moderate discriminative ability for GRACE39. Furthermore, another Asian study showed low discriminative ability for the GRACE model40. On the other hand, a Canadian study showed 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.88)35, and a Dutch study showed 0.86 (95% CI 0.83 to 0.90) C-static values, showing considerably higher discrimination of the tool over those populations compared to ours.

The present study’s limitations included the absence of a confirmatory evaluation for patients labeled as high-risk for OSA. However, this approach may be more feasible in clinical practice, given the cost-benefit of a questionnaire versus the gold-standard diagnostic tool. Furthermore, although the samples were selected from a referral hospital, the single-center nature and relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings. Although we employed domain-guided feature selection and cross-validation techniques to mitigate overfitting, the limited number of outcome events relative to the number of predictors still presents a risk of model overfitting. As such, the findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and require validation in larger, multicenter cohorts.

We also used five-fold/ten-fold cross-validation during model training; however, the limited number of outcome events relative to model complexity presents a risk of overfitting despite our attempts to minimize it. This risk underscores the preliminary nature of our findings, which require validation in larger, preferably multicenter cohorts. Also, our approach to handling missing data warrants comment. Although multiple imputation is often recommended in predictive modeling studies41, we opted for median imputation due to the low proportion of missingness (all features < 10%) and the non-normal distribution of our variables. Finally, given the frequent presence of imbalanced datasets in medical research, we specifically addressed this by deliberately avoiding synthetic over-sampling or under-sampling techniques to prevent data distortion.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that using the STOP-BANG score in conjunction with the GRACE score enhances key performance metrics such as F1-score, accuracy, and precision in the assessment of MI patients regarding post-MI in-hospital cardiovascular events. Also, the significant contribution of STOP-BANG in the trained machine learning algorithms and its impact on DCA reinforce its clinical relevance. These findings suggest that STOP-BANG remains a valuable addition to risk assessment models, offering practical benefits for clinical decision-making. Furthermore, this study showed that the GRACE tool has a moderate discriminative ability on the study sample.

Data availability

The deidentified data may be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request, pending approval from the relevant institutional review board (IRB) or ethics committee and subject to compliance with data protection regulations.

References

Li, S. et al. Cardiovascular events and death after myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke in an older medicare population. Clin. Cardiol. 42 (3), 391–399 (2019).

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2017 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 135 (10), e146–e603 (2017).

Yang, E. et al. Clinical and economic outcomes among elderly myocardial infarction survivors in the united States. Cardiovasc. Ther. 34 (6), 450–459 (2016).

Georgiopoulos, G. et al. Modification of the GRACE risk score for risk prediction in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA Cardiol. 8 (10), 946–956 (2023).

Bonsignore, M. R., Baiamonte, P., Mazzuca, E., Castrogiovanni, A. & Marrone, O. Obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities: A dangerous liaison. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 14, 8 (2019).

Lee, C. H. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 133 (21), 2008–2017 (2016).

Cassar, A., Morgenthaler, T. I., Lennon, R. J., Rihal, C. S. & Lerman, A. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea is associated with decreased cardiac death after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50 (14), 1310–1314 (2007).

Chung, F., Abdullah, H. R. & Liao, P. STOP-Bang Questionnaire: A practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 149 (3), 631–638 (2016).

Rajkomar, A., Dean, J. & Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 380 (14), 1347–1358 (2019).

Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 25 (1), 44–56 (2019).

Eriksen Alexander, V., Möller, S. & Ryg, J. Use of GPT-4 to diagnose complex clinical cases. NEJM AI. 1 (1), AIp2300031 (2024).

Zinzuwadia, A. N. et al. Tailoring risk prediction models to local populations. JAMA Cardiol. 9 (11), 1018–1028 (2024).

Taleb, I. et al. Machine learning multicenter risk model to predict right ventricular failure after mechanical circulatory support: The STOP-RVF score. JAMA Cardiol. 9 (3), 272–282 (2024).

Calvillo-Argüelles, O. et al. Integrating the STOP-BANG score and clinical data to predict cardiovascular events after infarction: A machine learning study. Chest 158 (4), 1669–1679 (2020).

Hunter, D. J. & Holmes, C. Where medical statistics Meets artificial intelligence. N. Engl. J. Med. 389 (13), 1211–1219 (2023).

Elbarouni, B. et al. Validation of the global registry of acute coronary event (GRACE) risk score for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome in Canada. Am. Heart J. 158 (3), 392–399 (2009).

Chung, F. et al. STOP questionnaire: A tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 108 (5), 812–821 (2008).

Chung, F., Yang, Y., Brown, R. & Liao, P. Alternative scoring models of STOP-bang questionnaire improve specificity to detect undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 10 (9), 951–958 (2014).

World Health Organization. International Classification of diseases: [9th] Ninth Revision, Basic Tabulation List with Alphabetic Index (World Health Organization, 1978).

Thygesen, K. et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 33 (20), 2551–2567 (2012).

Hochman, J. S. et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK investigators. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (9), 625–634 (1999).

Kluyver, T. et al. Jupyter Notebooks–A Publishing Format for Reproducible Computational Workflows. 87–90 (Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas, 2016).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Mak. 26 (6), 565–574 (2006).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44 (3), 837–845 (1988).

Movahedi, F., Padman, R. & Antaki, J. F. Limitations of receiver operating characteristic curve on imbalanced data: Assist device mortality risk scores. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 165 (4), 1433–42e2 (2023).

Vickers, A. J., van Calster, B. & Steyerberg, E. W. A simple, step-by-step guide to interpreting decision curve analysis. Diagn. Prognost. Res. 3 (1), 18 (2019).

Garcia-Rio, F. et al. CPAP effect on recurrent episodes in patients with sleep apnea and myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 168 (2), 1328–1335 (2013).

Lee, C-H. et al. Severe obstructive sleep apnea and outcomes following myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 7 (6), 616–621 (2011).

Xie, J. et al. Nocturnal hypoxemia due to obstructive sleep apnea is an independent predictor of poor prognosis after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 (8), e003162 (2016).

Zhao, Y., Yu, B. Y., Liu, Y. & Liu, Y. Meta-analysis of the effect of obstructive sleep apnea on cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 120 (6), 1026–1030 (2017).

Platek, A. E. et al. Stratification of cardiovascular risk in patients with atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea—Validity of the 2MACE score. Sleep. Breath. 21 (3), 601–606 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. Effect of obstructive sleep apnea on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes with varying numbers of standard modifiable risk factors: Insight from the OSA-ACS study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 56 (1), 65–74 (2023).

Amsterdam, E. A. et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 130 (25), e344–e426 (2014).

van der Sangen, N. M. R. et al. External validation of the GRACE risk score and the risk-treatment paradox in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Open. Heart 9(1), e001984 (2022).

Gong, I. Y. et al. GRACE risk score: Sex-based validity of in-hospital mortality prediction in Canadian patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 244, 24–29 (2017).

Wu, Z., Tang, C. & Wang, D. Bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study of association between smoking initiation and atrial fibrillation. Tob. Induc. Dis. 22, 10–18332 (2024).

Sia, C. H. et al. Association between smoking status and outcomes in myocardial infarction patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 6466 (2021).

Hosmer, D. W. Jr., Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R. X. Applied Logistic Regression (Wiley, 2013).

Kumar, D. et al. Prognostic value of GRACE score for in-hospital and 6 months outcomes after non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Egypt. Heart J. 73 (1), 22 (2021).

Thalib, L. et al. Validation of the 6-month GRACE score in predicting 1-year mortality of patients with acute coronary syndrome admitted to the Arabian Gulf hospitals. Angiology 68 (3), 251–256 (2017).

Moons, K. G. M. et al. PROBAST: A tool to assess risk of Bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 170 (1), W1–W33 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA) for language and style improvements in the manuscript draft. The authors accept full responsibility for all content and editorial decisions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences [Grant Number: 4030286].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VM, BS, and MM designed the study and AT conducted data gathering. VM was in charge of data analysis and preparation of manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahri, B., Tajik, A., Moohebati, M. et al. Incorporating the STOP-BANG questionnaire improves prediction of cardiovascular events during hospitalization after myocardial infarction. Sci Rep 15, 19180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03882-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03882-z