Abstract

Storm Daniel, the deadliest Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone, caused significant flooding in Thessaly Region, Greece, from September 4 to 7, 2023. This study examines the potential impact of such extreme weather events on vector-borne disease transmission by assessing changes in mosquito populations and West Nile virus (WNV) circulation before and after the flood in two regional units of Thessaly. Systematic monitoring data on mosquito larvae and adults, along with WNV circulation in mosquitoes and humans from 2021 to 2023, were analyzed using a weekly interrupted time series regression design controlling for confounding drivers and temporal trends. Results indicate a significant post-flood increase in Culex mosquito populations over the 7 weeks following the event. However, despite this increase—alongside optimal temperature conditions and pre-flood amplification of WNV—no corresponding rise in WNV circulation was observed in mosquitoes or human cases. This unexpected outcome may be influenced by multiple ecological factors, including disruptions of avian host communities, human displacement, and the timing of the flood during the autumn bird migration period. These findings underscore the complexity of vector-virus-host interactions and highlight the importance of continued systematic entomological surveillance for targeted mosquito control practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV), belonging to the Flaviviridae family and categorized within the Japanese encephalitis serocomplex, comprises over 70 viruses with at least five phylogenetic lineages, while only lineages 1 and 2 are associated with notable human disease outbreaks. In Greece, Culex pipiens serves as the primary vector, initially infecting birds before biting increasingly humans during late summer, potentially augmenting WNV transmission risk1,2,3,4.

The anticipated consequence of global warming is an increased likelihood of experiencing more frequent and intense floodings, due to increased temperature, and more frequent and intense precipitations5. Mosquitoes tend to become prevalent following a flood6. Initially, floods wash away Culex species larvae, as their eggs are laid on the surface of water bodies7. In contrast, “floodwater Aedes species” lay their eggs on damp soil and are resistant to desiccation8,9. These eggs hatch after flooding in the remaining stagnant water, and adult mosquitoes emerge quickly. Following the recession of floodwaters, stagnant pools of water frequently persist. These pools commonly attract adult female Culex spp. mosquitoes, leading to a resurgence in populations approximately 2 weeks post-flood8.

Climate factors, especially temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric moisture, are recognized for their influence on the abundance of mosquitoes in general and of Culex mosquitoes specifically. The specific effects of these climate variables on mosquito populations differ according to the particular Culex species, geographical region, and seasonal variations10,11. Generally, rising temperatures appear to be associated with an increased incidence of WNV infections10,12. High temperatures show a positive correlation with the transmission of WNV13 due to several factors, such as accelerated viral replication, larger mosquito populations, and faster larval development14,15,16. The recently developed models can predict a WNV outbreak 4 weeks in advance, specifically in response to temperature increase17,18. Elevated temperature during the winter months is also linked to a higher rate of WNV infections15,19,20. In essence, high temperature tends to increase the prevalence of WNV infections during the summer months and impedes its decline in winter15,21.

The relationship between precipitation and the transmission rate of WNV is intricate and depends on various factors, such as the volume and frequency of precipitation, and the season of the year11,22. Emerging evidence shows that both slight and heavy precipitation may increase WNV rates weeks after the events23,24. However, a surge in mosquito populations doesn’t always lead to VBD outbreaks6,16. For instance, in Canada, increased precipitation led to more Culex tarsalis mosquitoes but lower WNV infection rates, possibly due to changes in bird-mosquito interactions25 and in Kansas, despite confirmed evidence of WNV activity in the area after heavy rains and early summer floods in 2007, there was no increase in human cases of arboviral disease documented in four counties for the remainder of 200726.

In Greece and in Italy, Cx. pipiens is the primary WNV vector1,27. Molecular and serological detections in Greece and in Italy have proven effective for early virus circulation data28,29,30.

Ecodevelopment utilizes the innovative “eBite” mobile application and web dashboard, patented by the Hellenic Industrial Property Organization, for real-time recording and management of entomological field data, comparing larvae and adult population dynamics of predominant mosquito genera and WNV epidemiological data.

The aim of the present study was to estimate the impact of the extreme flooding caused by storm Daniel on mosquito populations and the transmission of WNV among mosquitoes and humans in a WNV-endemic region in Greece drawing on the wealth of systematically collected data within eBite over 3 years, comparing patterns before and after calendar week 36—the week of the 2023 flood—across all years.

Material and methods

Study area

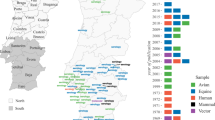

Thessaly, a predominantly agricultural region in Central Greece (Fig. 1), belongs to the Hot-Summer Mediterranean Climate (Csa) type according to the Köppen-Geiger classification, which is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The study area is characterized by extensive irrigation systems, minimal tourism, and frequent flood events in the Pinios River basin, with increased flood intensity due to climate change and economic development.

Storm Daniel, which hit Greece from September 4–7, 2023, caused severe flash floods in Eastern Thessaly with record-breaking rainfall of 700–800 mm in 24 h, expanding Lake Karla’s surface area from 3500 to 19,000 ha (Fig. 2). Thessaly, a hotspot for West Nile virus (WNV) since 2010, reported 44 of the 89 cases of West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND) in Greece in 2023. Mosquito control is implemented in Thessaly from May to October each year and relies preponderantly on larviciding, leading presumably to a reduced larvae and adult population during the implementation period. Only very restricted adulticiding interventions take place in areas where human cases of West Nile fever (WNF) are detected. Larviciding interventions are based on weekly entomological surveillance in a network of 3092 larvae breeding sites such as draining channels, watercourses, wetlands, and urban catch basins, and efficacy is monitored bimonthly through adult sampling at 14 fixed trapping sites in the regional units (RUs) of Larissa and Karditsa (Fig. 1).

Mosquito data

Since 2018, the eBite© tablet application has been used by over 130 field technicians in Thessaly and in four other Greek regions. Through this application mosquito larvae and adult population as well as insecticide application data are electronically recorded and monitored in real time, facilitating effective mosquito control project management. It implies a geodatabase of over 260,000 digitized breeding sites, which are visualized using ESRI webGIS services. The data aggregated in eBite© is accessible to more than 250 supervisors from contracting authorities for transparency and quality assurance reasons.

Over the 3-years period of 2021–2023, a total of 3092 potential mosquito breeding sites in the rural-periurban system in Thessaly were regularly inspected, with larvae sampling conducted using a 12 cm diameter dipping net with 1.2 mm mesh width along a 10 m path, and larvae were counted and categorized into Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex genera using a 5-point abundance scale31,32. In 2023, 18,781 larvae samplings were performed, with a reduction post-week 36 due to flooding after storm Daniel, affecting accessibility to breeding sites (Table 1).

As part of routine mosquito control programs in Thessaly, adult mosquitoes were collected using CO2-baited light traps known as “Ecodev traps”, set up in the morning, and retrieved after approximately 24 h, with live mosquitoes transported to the laboratory for identification and counting after short exposure to − 20 °C for immobilization31. For the morphological identification of adults, the key from Becker et al. 201033 was used. From 2021 to 2023, 14 fixed trapping sites were monitored fortnightly in Larissa and Karditsa RUs, and following the Daniel flood, the network was expanded to 50 trapping sites across all four regional units, including Larissa, Karditsa, Magnesia, and Trikala (Fig. 1).

West Nile virus

In the laboratory of Ecodevelopment, during 2023, adult Cx. pipiens mosquitoes were grouped into pools of maximum 55 individuals. Mosquitoes were homogenized using 30 μl of phosphate buffer saline (PBS 1X) per mosquito, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 1 min. The pools were stored at 4 °C for no longer than 12 h, or frozen at − 20 °C.

The total RNA was extracted from 100 μl of supernatant of the homogenized pools. RNA extraction was performed using the Sacace Biotechnologies Ribo-Sorb RNA/DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sacace Biotechnologies, Como, Italy). WNV was detected using a commercial real-time RT-PCR kit (Real Time PCR Kit for WNV, Sacace Biotechnologies, Como, Italy) which amplifies the 5’ non-coding region and partial of the nucleoprotein gene.

In the laboratory of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, throughout 2021–2023, the homogenization was performed in PBS using glass beads (diameter 150–212 μm) in a FastPrep FP120 cell disrupter (Bio-101, Thermo Savant; Q-Biogene, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The total RNA was extracted from 200 μl of supernatant of the homogenized pools, using the QIAamp cador Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. WNV was detected using a commercial real-time RT-PCR (RealStar WNV RT-PCR Kit, altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany). WNV risk indicators, like the Minimum Infection Rate (MIR), link infected mosquito prevalence to human case risk. The MIR, used here, is the number of positive pools divided by total tested mosquitoes, multiplied by 100034. All WNV-positive mosquito pools were tested by an RT-nested PCR which amplifies a 520nt fragment of the NS3a gene of WNV genome35. The PCR products were Sanger sequenced and BLAST analysis was performed.

Data analysis

We obtained meteorological data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) latest fifth-generation reanalysis product, ERA5-Land36,37. From this source we extracted hourly estimates of total precipitation and 2 m air temperature from 2021 to 2023 and aggregated at municipality level surveyed by the entomological surveillance within the flooded area. We merged the weather records with the data on larvae and adult Culex (and Aedes see supplementary data) mosquitoes and aggregated the data to weekly time series. The larvae and adult data were analysed for 2021–2023 between the weeks 18–43.

We conducted interrupted timeseries analysis38 to study the relationship between the flood and the entomological observations by constructing a model and counterfactual scenario of what would have been the expected larvae and adult mosquito counts if no flood had occurred and used this to estimate the relative effect of the flood impact. The counterfactual prediction was constructed based on a record of the normal weekly patterns before the flood, adjusting for temperature and rainfall anomalies. It was fitted using an over-dispersed Poisson distribution regression model using smoothing splines with 3 degrees of freedom for time (weekly), temperature and precipitation. Year was included as fixed factor. The flood was studied using a dummy variable with onset during the week of the flood and the following 7 weeks until the end of the study. We estimated the Culex (and Aedes see supplementary data) larvae and adults counts relative risk associated to flood, by adding 13 municipalities areas as fixed factor into the model. Residual diagnostic plots were investigated to assess statistical inference assumptions. The selected model did not include time lags, or mosquito larvae or adult spraying interventions, and the sensitivity analysis indicates that these factors did not markedly affect the estimates of the flood effect.

Results

To better understand and showcase the impact of Storm Daniel on mosquito larvae and adult population as well as infection rates in mosquitoes and WNV transmission to humans, in the following analysis authors will compare what happened before and after week 36 each year for the period 2021–2023.

Mosquito larvae and adult data

In 2023, 1029 weekly mosquito larvae samplings were conducted, 679 before and 350 after the flood in week 36. In comparison, there were 1002 and 1008 samplings in 2022, and 1066 and 635 in 2021, respectively (Table 1).

Culex larvae positivity of breeding sites (percentage of breeding sites inspected with positive findings for the presence of Culex larvae) before the flood ranged from 2 to 6%, dropping below 2% during week 36, but rising sharply afterward, peaking in week 40 with 18% positivity (Fig. 3a). The temperatures post-flood in 2023 were notably higher than in the previous 2 years. This flood-induced increase in larvae positivity of breeding sites in Culex, deviated from previous years’ trends (Fig. 3b).

Similar trends have also been observed for mosquito larvae of the genera Aedes and Anopheles (Figure S1).

In 2023, 33,316 adult female mosquitoes were collected in Thessaly out of which 30,963 were identified as Culex spp. Comparatively, in 2022, 21,692 adults were collected comprising 20,663 Culex spp., and in 2021, 12,421 female adults out of which 11,447 Culex spp. (Table 2).

The relative numbers for Aedes spp. and Anopheles spp. are shown in Table S1.

In 2023, the average population of Culex mosquitoes per trap per night quadrupled the weeks after the flood (Table 2, Fig. 4). The rise in adult mosquito population correlated with increased positivity of mosquito larvae breeding sites, although the larvae population increased more rapidly than the adult mosquito population. Maximum daily temperature (23.3 °C) in week 38 seems to be sufficient for the completion of the molting into adult mosquitoes and thus subsequent increase in adult mosquito population. While the trend of adult mosquito populations in previous years was similar to 2023 before week 36, the size of mosquito populations differed notably after storm Daniel, but this trend subsided several weeks post-flood.

The relative data for Aedes and Anopheles adult mosquitoes are displayed in Figure S2.

Relative risk estimates and Interrupted timeseries analysis

Figure 5 shows the relative risk estimates for Culex larvae counts for up to 7 weeks after the flood. Statistically significant values have been obtained at weeks 3–7 (Fig. 5a). The largest effect of flood was observed at week 5 with a relative risk estimate of 5.7 (95% CI 3.3–9.8) for Culex larvae counts (Fig. 5a). Adult mosquito counts observed a deviation above normal with a relative risk of 5.5 (95% CI 3.2–9.7) at week 3 for Culex (Fig. 5b) species counts.

Relative risk estimates for Aedes larvae counts and Aedes adult counts are demonstrated in Figure S3.

Figure 6 shows the observed and predicted values of Culex larvae counts (Fig. 6) along with the counterfactual predictions in the absence of flood. The climate-based counterfactual predictions showed much lower values for the Culex larvae and adults compared to what was observed.

These results show that the increase in Culex larval populations following the flood cannot be explained solely by climate variables (temperature, precipitation), but that the direct impact of the flooded surfaces plays an important role.

Relative data for predicted and observed values of Aedes larvae counts with counterfactual predictions in the absence of flood are shown in Figure S4.

Monitoring of WNV infection in mosquitoes

In 2023, before the flood event, in the framework of systematic entomological surveillance within the mosquito control programmes in Larisa and Karditsa RUs, a total of 3314 Cx. pipiens mosquitoes were analysed for the presence of WNV, and the virus was detected in three (3) pools. This resulted in a Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) of 0.91 for the region of Thessaly (Fig. 7a). Referring to the RUs of Larissa and Karditsa an MIR of 1.1 and 0 respectively was calculated for the period until week 36 (Fig. 7b). After the flood event the adult mosquito monitoring network was expanded and screening of adult mosquitoes for the detection of WNV circulation was carried out in all samples. A total of 12,641 Cx. pipiens mosquitoes were analysed and the virus was detected in two (2) mosquito pools. The MIR for the region of Thessaly after the flood event was determined to be 0.16 (Fig. 7a), suggesting that the MIR at Thessaly was higher before the flood event than after it. In the RUs of Larissa and Karditsa the respective MIRs were 0 and 0.42 respectively for the period after week 36, indicating equally a descending MIR in Larisa after the flood and an increasing in Karditsa.

In 2021 and 2022, the same analysis took place during the same timeframe. In 2022, until week 36, the MIR in Thessaly with 0.82 was slightly lower compared to that of 2023 (Fig. 7a), and the MIR after week 36 with 0.7 was lower compared to the period before this week, but clearly higher than in 2023. For the RUs of Larisa and Karditsa (Fig. 7b) before week 36 the MIRs in 2022 were 0.94 and 0 respectively, slightly lower than in 2023 for the same period, and after week 36 the MIRs were 0.75 in the RU of Larisa and 0 in the RU of Karditsa indicating a slight decrease in Larisa and stable conditions in Karditsa. Concerning 2021, the MIR in Thessaly before week 36 was at quite high levels (1.76) and was zeroed after this week (Fig. 7a) while in the RUs of Larisa and Karditsa the respective MIRs were 0.56 and 6.2 before week 36 and 0 in both RUs after it (Fig. 7b). The number of analysed mosquitoes and the positive pools for the region of Thessaly and the RUs of Larisa and Karditsa are presented in Table 3.

The sequencing of the PCR products showed that all sequences belonged to WNV lineage 2, presenting > 99% identity with respective WNV Greek sequences of the previous years, suggesting that there was no new virus incursion in the region of Thessaly in 2023.

Data on WNV infections in humans in Thessaly Region, 2021–2023

According to the annual reports of the National Public Health Organization39, the total confirmed WNND cases in 2023 in Greece were 119, and 46 out of them occurred in the Thessaly region, designating it as one of the WNV epicenters for 2023 (Fig. 8a). 18 out of these 46 WNND cases were recorded in the RU of Larissa and 16 in the RU of Karditsa. It was observed that in Larissa 17 out of the 18 WNND cases in 2023 were reported before week 36 and only one case was recorded after the flood (Fig. 8b) and in Karditsa all 16 cases occurred before the flood. As a result, the incidence rates per 100,000 population for the RU of Larissa were 6.32 before and 0.37 after week 36, while in Karditsa it was 12.38 and 0 respectively.

An inverse trend was recorded in Thessaly in 2022 when a total of 27 WNND cases were registered in Thessaly, with 6 WNND cases in the RU of Larissa having occurred before week 36, and 19 cases afterwards and no cases in the RU of Karditsa before and after week 36 (Fig. 8b). As a result, the incidence rates in the RU of Larissa before and after week 36 were 2.23 and 7.06, respectively. No human cases were reported in Thessaly in 2021 (Fig. 8a).

Before storm Daniel, Larissa and Karditsa saw high WNV cases and positive mosquito pools (Fig. 9a). Post-flood, transmission didn’t intensify as feared (Fig. 9b). Trikala and Magnesia had consistent human cases before and after the flood, but no mosquito pool data exists for comparison (Fig. 9ab).

Discussion

Flood phenomena due to climate change are increasingly happening worldwide. Although rainfall has been associated with increased risk for mosquito-borne diseases, the number of studies on identifying the specific impact of a flood is very limited24. To our knowledge the present study is the first to examine flood impacts on mosquito larvae and adult populations and disease epidemiology for three consecutive years.

Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece, caused unprecedented, severe flash floods on September 4–7, 2023 and the hydrologic impact persisted beyond the precipitation period, affecting major water sources as well as agricultural and urban areas. Especially lake Karla (RU of Larissa and Magnesia) quadrupled in size post-flood, making the agricultural land inaccessible for a long period [https://greenagenda.gr].

Before the flood, ECODEVELOPMENT conducted routine entomological and epidemiological monitoring in Larissa and Karditsa for decision making about standard mosquito control actions. After the flood, adult monitoring was intensified, with adult sampling sites reaching 50 from initially 14.

Culex mosquito larvae populations increased gradually, peaking in week 39 with fourfold populations in relation to the pre-flood period, most probably due to the initial larvae outflushing by floodwaters and the formation of new breeding sites afterwards as it also happened in Kansas26. The Aedes mosquito larvae population increased 18-fold post-flood—an exceptionally high surge, though not unexpected for floodwater species like Aedes caspius and Aedes detritus, which typically hatch en masse after the first autumn rains following summer droughts9.

Our statistical analysis examined the time-varying effects of temperature and rainfall on weekly larvae and adult counts of Culex and Aedes species following the 7 weeks after the 2023 flood and observed significant increases in Culex and Aedes larvae and adult populations associated with storm Daniel. As could be expected, the highest risk of Aedes larvae occurred approximately 2 weeks after the heavy rains and flooding (in week 3 after the storm). The probability (relative risk) of getting Aedes larvae and adults in the third week after the storm was 15% (95% CI 5.70–40.8, P ≤ 0.01)) and 20% (95% CI 7.25–54.5, P ≤ 0.01)) respectively, whereas for Culex larvae and adults it was ~ 5% (larvae, RR:4.1%, 95% CI 2.13–7.96, P ≤ 0.01 and adults, RR:5.5%, 95% CI 3.16–9.67, P ≤ 0.01). Subsequently, the highest risk for Culex larvae was identified during the 5th week after the storm when floodwaters accumulated in ditches, catch basins, or other areas and became stagnant water.

As this analysis shows, the ratio of larvae increase post-flood was relatively higher than that of adult mosquitoes, which can be expected due to factors like natural mortality, predation, intraspecific competition and a lack of nutrients40,40,41,43. Breeding site positivity for Culex spp. and Aedes spp. in 2021 and 2022 as well as adult population sizes in 2021 before week 36 showed a common trend but differed significantly afterwards. While larvae and adult populations ceased after week 36 in the two previous years, in 2023 both peaked at the beginning of October (week 39) followed by a steady decrease afterwards, most probably influenced by decreasing temperatures and the shortening photoperiod consistent with the progression of the season44,45.

Epidemiological surveillance in the regional units of Larisa and Karditsa before Storm Daniel detected WNV circulation in adult Culex mosquitoes showing increased positivity rates from early to mid-summer. This finding is in line with the fact that Thessaly was the WNV outbreak epicenter in 2023, with 44 human cases by early September. While MIR in mosquitoes is known to be a strong predictor of WNV transmission to humans46, its correlation with human cases in Thessaly showed notable variability over the 3-year period. In 2021, for instance, significant WNV circulation in mosquitoes was observed before week 36 without resulting in any recorded human cases. In contrast, in 2022, higher MIRs were again detected before week 36, but human cases were delayed, accumulating after week 36 and indicating an unusually late onset and prolonged transmission season, despite the absence of exceptionally high temperatures during this period. These patterns highlight on the one hand that molecular detection of WNV in mosquitoes remains a valuable early warning tool, capable of indicating virus presence even in the absence of human West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND) cases—considering the possibility of asymptomatic or mild, unrecorded infections. On the other hand, the discrepancy in MIRs and human cases in Thessaly during the periods before and after week 36 in 2022 shows that the usefulness of this indicator depends strongly on the intensity of monitoring because, depending on the total number of mosquitoes analysed, the MIR index varies significantly. In cases where a smaller number of mosquitoes are tested for the presence of WNV, the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) index could be considered a more reliable indicator47. This approach, however, was not feasible in Thessaly, as the extreme variability in the number of Cx. pipiens collected per sample (Median = 22, range 1–1531 in 2022) made it impossible to use a fixed pool size. Nonetheless, in this study, the Minimum Infection Rate (MIR) derived from molecular analysis of Culex mosquitoes proved to be a valuable indicator of virus circulation in Thessaly, correlating with human cases before and after the flood event in 2023.

Remarkably, though, while particularly Culex mosquito populations increased exponentially in the aftermath of Storm Daniel and favorable temperatures persisted, both the MIR values and human WNV cases declined. This was counterintuitive, as such an increase in vector abundance combined with suitable environmental conditions could be expected to sustain or even amplify WNV transmission48,49. The observed drop in virus circulation and human cases despite high vector densities suggests that the flood-induced environmental disruption may have interrupted the transmission cycle—whether by eradicating infected mosquitoes, displacing infected avian hosts50, human displacement49, and/or modifying human behaviors such as reduced time spent outdoors and closed doors and windows.

Nevertheless, a definitive explanation for this apparent contradiction remains elusive, as the effects of extreme flooding on WNV transmission are shaped by a complex and dynamic interplay of climatic, ecological, and behavioral factors. These findings highlight the need for more detailed, multidisciplinary field studies to better understand the mechanisms driving arbovirus circulation under such conditions.

Also, while the overall number of WNND cases in the Region of Thessaly declined from 46 in 2023 to 38 in 202451, the extreme flooding caused by Storm Daniel in late 2023 could have been expected to lead to increased WNV transmission not only during the fall of 2023 but also throughout the entire 2024 season as happened in Louisiana and Mississippi after storm Katrina in 200649. This was not uniformly the case across the region. While in Karditsa and Trikala WNND cases dropped from 16 to 7 and from 12 to 1 respectively, a closer look at the Larissa RU, where floodwater persisted in the extended Lake Karla (see Fig. 2) and surrounding agricultural areas well into 2024, reveals a contrasting trend. Here, WNND cases rose from 18 in 2023 to 30 in 2024, with 24 of these occurring before epidemiological week 36 and another 6 cases afterward, indicating a prolonged and sustained WNV transmission period. This trend was also confirmed by MIRs for Larissa RU which showed values of 1.18 before and 1.40 after week 36 in 2024 [Ecodevelopment, unpublished data]. This localized increase may reflect an intensified presence of wild birds—primary WNV hosts—attracted by the new wetland-like environment, combined with significant challenges in implementing mosquito control measures in areas that remained inaccessible due to long-term flooding. Also, the relatively early onset of WNND cases in the RU of Larissa in 2024 (week 25) could reflect early virus amplification. This raises the question if vertical transmission in Culex pipiens, a mechanism known to support WNV overwintering in temperate regions52,53, may have contributed to the early re-emergence of the virus in this flood-affected area. These findings underscore the complexity of arbovirus ecology and highlights the limitations of vector density alone as a predictor of transmission risk, emphasizing the importance of ecological and behavioral context in shaping outbreak dynamics.

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the complex and sometimes counterintuitive effects of extreme flooding on mosquito populations and WNV transmission dynamics. By integrating longitudinal entomological, virological, and epidemiological data, it highlights how environmental disruptions—such as those caused by Storm Daniel—can alter transmission cycles in ways that are not sufficiently captured by vector abundance alone. The findings underscore the importance of sustained, real-time surveillance systems that combine larval and adult mosquito monitoring, molecular detection of WNV, and human case reporting to support early warning and targeted response. Crucially, the observed decoupling between mosquito population surges and virus circulation calls for more integrated, interdisciplinary field studies to better understand how ecological, climatic, and behavioral factors interact during and after extreme weather events. Strengthening such surveillance and research frameworks will be essential for anticipating and mitigating arbovirus risks in an era of increasing climate variability.

Data availability

Mosquito larvae and adult monitoring data that support the findings of this study has been deposited in the Mendeley Data repository: Gewehr, Sandra; Mourelatos, Spiros (2024), “THESSALY 2023”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/9frz4845vw.1.

References

Papa, A., Xanthopoulou, K., Gewehr, S. & Mourelatos, S. Detection of West Nile virus lineage 2 in mosquitoes during a human outbreak in Greece. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 1176–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03438.x (2011).

Hamer, G. L. et al. Host selection by Culex pipiens mosquitoes and West Nile virus amplification. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80, 268–278. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.268 (2009).

Kilpatrick, A. M., Kramer, L. D., Jones, M. J., Marra, P. P. & Daszak, P. West Nile virus epidemics in North America are driven by shifts in mosquito feeding behavior. PLoS Biol. 4, e82. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040082 (2006).

Martínez-de, J. et al. Culex pipiens forms and urbanization: Effects on blood feeding sources and transmission of avian Plasmodium. Malaria J. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1643-5 (2016).

Alifu, H., Hirabayashi, Y., Imada, Y. & Shiogama, H. Enhancement of river flooding due to global warming. Sci. Rep. 12, 20687. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25182-6 (2002).

Gilliland, T. M., Rowley, W. A., Swack, N. S., Vandyk, J. K. & Bartoces, M. G. Arbovirus surveillance in Iowa, USA, during the flood of 1993. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 11, 157–161 (1995).

Gardner, A. M. Weather variability affects abundance of larval Culex (Diptera: Culicidae) in storm water catch basins in suburban Chicago. Med. Entomol. 49, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1603/me11073 (2012).

Godsey, M. S., Burkhalter, K., Delorey, M. & Savage, H. M. Seasonality and time of host-seeking activity of Culex tarsalis and floodwater Aedes in northern Colorado, 2006–2007. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 26, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.2987/09-5966.1 (2010).

Rydzanicz, K., Kącki, Z. & Jawień, P. Environmental factors associated with the distribution of floodwater mosquito eggs in irrigated fields in Wrocław Poland. J. Vector Ecol. 36, 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7134.2011.00173.x (2011).

Vukmir, N. R., Bojanić, J., Mijović, B., Roganović, T. & Aćimović, J. Did intensive floods influence higher incidence rate of the West Nile virus in the population exposed to flooding in the Republic of Srpska in 2014?. Arch. Vet. Med 12(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.46784/e-avm.v12i1.35 (2019).

Ferraccioli, F. et al. Effects of climatic and environmental factors on mosquito population inferred from West Nile virus surveillance in Greece. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45666-3 (2023).

Farooq, Z. et al. Artificial intelligence to predict West Nile virus outbreaks with eco-climatic drivers. Lancet Reg. Heal. Eur. 17, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100370 (2022).

Farooq, Z. et al. European projections of West Nile virus transmission under climate change scenarios. One Health 16, 100509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100509 (2023).

Anyamba, A. et al. Recent weather extremes and impacts on agricultural production and vector-borne disease outbreak patterns. PLoS ONE 9(3), e92538. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092538 (2014).

Paz, S. Climate change impacts on West Nile virus transmission in a global context. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370(1665), 20130561. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0561 (2015).

Soverow, J. E., Wellenius, G. A., Fisman, D. N. & Mittleman, M. A. Infectious disease in a warming world: How weather influenced West Nile virus in the United States (2001–2005). Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 1049–1052. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0800487 (2009).

Kilpatrick, A. M. & Pape, W. J. Predicting human West Nile virus infections with mosquito surveillance data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 178, 829–835. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt046 (2013).

DeFelice, N. B. et al. Use of temperature to improve West Nile virus forecasts. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14(3), e1006047. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006047 (2018).

DeGroote, J. P. & Sugumaran, R. Landscape, demographic and climatic associations with human West Nile virus occurrence regionally in 2012 in the United States of America. Geospat. Health 9, 153–168. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2014.13 (2014).

Hahn, M. B. et al. Meteorological conditions associated with increased incidence of West Nile virus disease in the United States, 2004–2012. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92, 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0737 (2015).

Reisen, W. K., Fang, Y. & Martinez, V. M. Effects of temperature on the transmission of West Nile virus by Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2006)043[0309:EOTOTT]2.0.CO;2 (2006).

Giesen, C. et al. A systematic review of environmental factors related to WNV circulation in European and Mediterranean countries. One Health 16, 100478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100478 (2023).

Coalson, J. E. et al. The complex epidemiological relationship between flooding events and human outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases: A scoping review. Environ. Health Perspect. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP8887 (2021).

Landesman, W. J., Allan, B. F., Langerhans, R. B., Knight, T. M. & Chase, J. M. Inter-annual associationsbetween precipitation and human incidence of West Nile virus in the United States. VectorBorne Zoonot. 7, 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0590 (2007).

Chen, C.-C. et al. Modeling monthly variation of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae) abundance and West Nile virus infection rate in the Canadian prairies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 3033–3051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10073033 (2013).

Harrison, B. A. et al. Rapid assessment of mosquitoes and arbovirus activity after floods in Southeastern Kansas, 2007. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 25, 265–271. https://doi.org/10.2987/08-5754.1 (2009).

Calzolari, M. et al. West Nile Virus Surveillance in 2013 via mosquito screening in northern Italy and the influence of weather on virus circulation. PLoS ONE 10(10), e0140915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140915 (2015).

Tsioka, K. et al. West Nile virus in Culex mosquitoes in Central Macedonia, Greece, 2022. Viruses 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010224 (2023).

Chiari, M. et al. West Nile virus surveillance in the Lombardy region Northern Italy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 62, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12375 (2015).

Vakali, A. et al. Entomological surveillance activities in regions in Greece: Data on mosquito species abundance and West Nile virus detection in Culex pipiens pools (2019–2020). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8010001 (2022).

Gewehr, S. & Mourelatos, S. THESSALY 2023, Mendeley Data, V1, (2024). https://doi.org/10.17632/9frz4845vw.1

European Mosquito Control Association. Guidelines for mosquito control in built-up areas in Europe. (2024). https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/jDRvgn

Becker, N. et al. Mosquitoes and their Control (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-92874-4.

ECDC. Guidelines for the surveillance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe. Stockholm 100. (2012). https://doi.org/10.2807/ese.17.36.20265-en

Papa, A., Papadopoulou, E., Gavana, E., Kalaitzopoulou, S. & Mourelatos, S. Detection of West Nile virus lineage 2 in Culex mosquitoes, Greece, 2012. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 13, 682–684. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2012.1212 (2013).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Muñoz, S. J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4349-2021 (2021).

Liyanage, P. et al. Evaluation of intensified dengue control measures with interrupted time series analysis in the Panadura Medical Officer of Health division in Sri Lanka: A case study and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Planet. Heal. 3, e211–e218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30057-9 (2019).

National Public Health Organization. Annual epidemiological report for West Nile Virus infection, Greece, 2023. https://eody.gov.gr/en/epidemiological-statistical-data/annual-epidemiological-data/. Accessed on 06 June 2025.

Ranasinghe, H. A. K. & Amarasinghe, L. D. Naturally occurring microbiota associated with mosquito breeding habitats and their effects on mosquito larvae. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4065315 (2020).

Alto, B. W., Muturi, E. J. & Lampman, R. L. Effects of nutrition and density in Culex pipiens. Med. Vet. Entomol. 26, 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01010.x (2012).

Reiskind, M. H., Walton, E. T. & Wilson, M. L. Nutrient-dependent reduced growth and survival of larval Culex restuans (Diptera: Culicidae): Laboratory and field experiments in Michigan. J. Med. Entomol. 41, 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.650 (2004).

Dambach, P. The use of aquatic predators for larval control of mosquito disease vectors: Opportunities and limitations. Biol. Control 150, 104357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104357 (2020).

Mori, A., Romero-Severson, J. & Severson, D. W. Genetic basis for reproductive diapause is correlated with life history traits within the Culex pipiens complex. Insect Mol. Biol. 16, 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00746.x (2007).

Peffers, C. S., Pomeroy, L. W. & Meuti, M. E. Critical photoperiod and its potential to predict mosquito distributions and control medically important pests. J. Med. Entomol. 58, 1610–1618. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjab049 (2021).

Riccardo, F. et al. An early start of West Nile virus seasonal transmission: The added value of One Heath surveillance in detecting early circulation and triggering timely response in Italy, June to July 2018. Euro Surveill. 23(32), 1800427. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.32.1800427 (2018).

Gu, W., Lampman, R. & Novak, R. J. Problems in estimating mosquito infection rates using minimum infection rate. J. Med. Entomol. 40(5), 595–596. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-40.5.595 (2003).

Mulatti, P. et al. Determinants of the population growth of the West Nile virus mosquito vector Culex pipiens in a repeatedly affected area in Italy. Parasites Vectors 7, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-26 (2014).

Caillouët, K. A., Michaels, S. R., Xiong, X., Foppa, I. & Wesson, D. M. Increase in West Nile neuroinvasive disease after Hurricane Katrina. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14(5), 804–807. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071066 (2008).

Paz, S. & Semenza, J. C. Environmental drivers of West Nile fever epidemiology in Europe and Western Asia–A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 10(8), 3543–3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083543 (2013).

National Public Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Report for West Nile Virus infection, Greece, 4 December 2024. (2024). Accessed 30 Sep 2025 at https://eody.gov.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/report_wnv_eng_20241204.pdf

Fechter-Leggett, E., Nelms, B. M., Barker, C. M. & Reisen, W. K. West Nile virus cluster analysis and vertical transmission in Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in Sacramento and Yolo Counties, California, 2011. J. Vector Ecol. 37, 442–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7134.2012.00248.x (2012).

Mbaoma, O. C., Thomas, S. M. & Beierkuhnlein, C. Significance of vertical transmission of arboviruses in mosquito-borne disease epidemiology. Parasites Vectors 18, 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-025-06761-8 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The screening of mosquitoes for WNV in Aristotle University of Thessaloniki was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant No. 874735 (VEO). Rocklöv and Dafka were supported by the Alexander von Humboldt foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. contributed to conceptualisation, writing – review & editing, investigation, methodology and resources.E.C. contributed to writing – original draft, data curation, formal analysis, methodology and investigation.S.K. contributed to investigation, methodology and project administration.X.T. contributed to data curation and visualisation.N.L. contributed to nivestigation, methodology and project administration.K.T. contributed to methodology and Investigation.A.P. contributed to writing – review & editing.S.D. contributed to formal analysis, methodology and validation.J.R. contributed to formal analysis, methodology, validation and writing – review & editing.S.G. contributed to conceptualisation, data curation, writing – review & editing, investigation, methodology, visualization and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mourelatos, S., Charizani, E., Kalaitzopoulou, S. et al. Extreme flood and WNV transmission in Thessaly, Greece, 2023. Sci Rep 15, 22433 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03884-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03884-x