Abstract

The discharge of non/ill-treated industrial effluent containing organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) and potentially toxic metal ions into the aquatic ecosystem has endangered both aquatic life and man. Thus, this study presents the evaluation of potentially toxic metal ions in thirteen industrial effluents sampled from five different states in Nigeria, as well as the level of OCPs content of a pesticide industry sited in Kanu State, Nigeria. The range of concentration estimated for the analyte was noticed to be higher than the recommended concentration limits for both OCPs and potentially toxic metal ions. Thus, biozinc oxide nanoparticles (BioZnONPs), zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs), and biozinc oxide-carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposite (BioZnONPs-CMC) were fabricated and characterized using non-destructive spectroscopic techniques and a specific surface area analyzer for remediation of industrial effluents. The incorporation of nanoparticles and nanocomposites resulted in a substantial reduction in key water quality parameters, including total dissolved solids (TDS), sulfate (SO₄²⁻), electrical conductivity (EC), total phosphorus, chemical oxygen demand (COD), chloride (Cl⁻), and pH, highlighting their potential for effective water purification applications. The OCPs mean adsorption capacities of BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC were determined as 10.2 ± 10.182 mg g–1, 14.2 ± 4.526 mg g–1, and 14.2 ± 4.525 mg g–1, respectively. Conversely, BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC exhibited strong efficacy in removing cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), and lead (Pb) ions from industrial effluents, underscoring their potential as effective agents for heavy metal remediation. This study shows the successful fabrication of wastewater treatment agents for the removal of OCPs and potentially toxic metal ions. To maintain a safe environment, this study also highlights the necessity of routinely evaluating both treated and untreated industrial effluents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global application of pesticides in agricultural practices has resulted in the widespread of these chemicals in the environment. Pesticides are classified based on their functions and active chemical constituents. Among the pesticides are organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), which are designed to interrupt the neural activity of the pests, leading to their death. Most of the time, this class of pesticide is made to have a certain function. Hence, their effectiveness in pest control results in their application in large volumes. Many local farmers (in Africa and Pakistan) utilize OCPs extensively, and these pollute the surface water bodies as they move alongside runoffs1,2,3. Besides the extensive application of OCPs in the agricultural sector, accidental spillage, misuse, improper disposal, and industrial discharge during their production have contributed immensely to the recalcitrant occurrence of OCPs residues and their metabolites in water sources4,5. Despite decades of policies banning the use of OCPs in most nations, some African countries have yet to enforce these regulations. Additionally, they have not provided viable alternatives for agricultural use or domestic insect control, which is crucial in combating endemic diseases like malaria. The presence of OCPs in the aquatic ecosystem is of great concern to man. Due to their persistent nature, they bioaccumulate, biomagnified, and pose a broad range of devastating challenges to human health and the environment6,7,8,9.

A Medium- or long-term exposure to OCPs may result in convulsion, atherosclerosis, dizziness, porphyria, vomiting, transient hepatotoxicity, irritability, involuntary movement of the muscles, peripheral and chloracne, endocrine disruption, neuropsychological impairment, liver damage, cardiovascular diseases, and impaired reproduction10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Besides OCPs, metal ions such as Cr(VI), Cd(II), and Pb(II) have demonstrated a high tendency to negatively impact the quality of water sources. These metal ions are toxic and are frequently emitted into water bodies by fertilizer runoff from farmlands, paints, alloys, coal combustion, printing, pulp, waste batteries, steel smelting, refineries, and electroplating industries18. Meanwhile, anemia, lung inefficiency, asthma, hypertension, malaise, liver and kidney damage, pneumonitis, loss of appetite, nasal septum, renal damage, skin allergies, cancer, bronchitis, calcium depletion in bones, and learning and behavioral difficulties in children can all result from metal ion toxicity19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

Due to the toxic implications of potentially toxic metal ions and OCPs to man and aquatic life, several technologies have been designed to eliminate these water contaminants from the aquatic ecosystem. The treatment techniques include coagulation-flocculation27, chemical precipitation28, advanced oxidation processes29,30,31, reverse osmosis32, photodegradation33, nanofiltration34,35,36,37, electrochemical treatment38, ozonization39, application of membrane technology40, ion-exchange processes41, anaerobic biodegradation42,43 and adsorption44,45,46 using activated carbons47,48,49. However, most of them demand significant financial investment, and their use is frequently limited because the economic considerations outweigh the significance of pollution management. As a result, their implementation in non-industrialized countries is impractical. Due to its convenience, ease of operation, and flexibility of design, adsorption is regarded as one of the most practicable methods for water purification available50. This technique can remove several types of water contaminants, making it useful for water pollution control51. Adsorbents such as activated carbon have been widely utilized for removing water contaminants through batch adsorption techniques. However, their effectiveness is constrained by high production costs and the challenging regeneration process, which limits their practicality for large-scale and sustainable applications52. To circumvent this drawback, adsorbents such as biochar53,54, sugarcane bagasse55, Fe3O4@PS56, seeds57, Acacia etbaica58, rice husk59, porous carbonaceous material60, Scots pine61, kaolinite clay62, leaves63, MSNPs/Fe3O464, mazari palm65, groundnuts66,67, CS–AgONPs68, pine cone shell69, and Arthrostira plantensis70 have been employed for water contaminant removal. However, these techniques have had variable levels of success, particularly with pollutants at low but ecologically important concentrations, and they are not always available or convenient in some settings. Therefore, much research is ongoing into designing materials and methods that work across a range of concentrations and are available at low cost as adsorbents for use in environmental remediation.

Metal nanoparticles have been widely employed in several fields, including the water treatment sector, due to the benefits of their nano-scale characteristics. Techniques such as chemical vapour deposition, chemical precipitation, co-precipitation, thermal decomposition, electrochemical depositions, ablation, microwave-assisted, polyol process, combustion method, sol-gel method, ultrasound, solvothermal synthesis, anodization, and sonochemical synthesis, amongst others, have been used for the synthesis of metal nanoparticles71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85.

However, these synthetic routes were reported to be relatively expensive and toxic to the environment86. On the other hand, most academics like the use of green synthetic pathways since it lowers harmful waste, is environmentally benign, and reasonably inexpensive87. Meanwhile, they exhibit unique catalytic characteristics in their nano sizes due to their large surface area and intrinsic properties. Hence, the fabrication of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) via the green synthetic route for water remediation can promote environmental safety and effective wastewater purification. Zinc oxide nanoparticles as absorbents can be desorbed and regenerated after several cycles of application. Hence, preventing the reintroduction of contaminants into the environment. Dalium guineense is known in English as Black Velvet Tarimand, Icheku in Igbo, and Awin in Yoruba. The stem bark of this tree plant is believed to house phytochemicals with reductive potential and, hence, can be used for the biosynthesis of ZnONPs.

The objectives of the study research were to validate the presence and concentration levels of potentially toxic metal ions (Cd, Cr and Pb) and OCPs (alpha(α)-BHC, endrin aldehyde, beta(β)-BHC, dieldrin, endrin, gamma(γ)-BHC, endrin ketone, delta(δ)-BHC, heptachlor, heptachlor epoxide, endosulfan sulfate, aldrin, alpha(α)-chlordane, endosulfan I, endosulfan II, P,p’-DDE (dichloro-diphenyl chloroethane), P,P′-DDD (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane), gamma(γ)-chlordane, P,P′-DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), and methoxychlor) from various industrial effluents collected from different geopolitical zones in Nigeria. This study presents a pioneering approach to the remediation of industrial effluents by fabricating and characterizing biozinc oxide nanoparticles (BioZnONPs), zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs), and a novel biozinc oxide-carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposite (BioZnONPs-CMC). Unlike conventional treatment methods, our work uniquely integrates bio-based nanomaterials with advanced spectroscopic and surface area analyses to enhance the removal efficiency of both organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) and potentially toxic metal ions from contaminated wastewater. The study provides the first comprehensive assessment of industrial effluent contamination across five Nigerian states, revealing pollutant concentrations exceeding regulatory limits. Our findings demonstrate the superior adsorption capacities of these nanomaterials, particularly in the sequestration of water contaminants. By bridging nanotechnology with sustainable wastewater treatment, this research contributes a significant advancement toward safer industrial discharge management and environmental sustainability.

Materials and methods

The materials used for the experiments (sodium hydroxide, granulated lead, cadmium and chromium metal, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), H2SO4, HCl, H3PO4, NaOH, and analytical grade acetone and ethanol, Zinc acetate dihydrate) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without additional purification.

Chemical synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONP)

ZnO nanoparticles were produced by mixing aqueous solutions of Zinc acetate dihydrate and sodium hydroxide. This involved dissolving 22.8 g (0.124 mol) of zinc acetate dihydrate in 750 cm3 of deionized water and 6.0 g (0.1 mol) of NaOH in 1500 ml of deionized water. Both solutions were mixed by adding the aqueous NaOH dropwise under magnetic stirring and maintaining the stirring for 30 min. The mixture was allowed to cool, and precipitates were filtered and washed with distilled water and absolute ethanol several times. The precipitates obtained were then dried at 60 °C for 24 h and calcined at 200 °C for 2 h.

Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (BioZnONP)

The modified method of Amaku et al. (2021) was used to acquire the aqueous plant extract. Briefly, 300 g of powdered Dalium guineense Stem bark was extracted using double-distilled water (DDW) (0.5 L) at room temperature for 5 days88. Thereafter, 50 ml of the aqueous extract was heated to 60 °C on a magnetic stirrer hotplate, and 5 g of Zn(NO3)2.6H2O was added with continuous stirring for 1 h. 10 ml of 1 M NaOH was added dropwise at the rate of 3 ml min−1 to take pH to 12. The stirring was continued for 1 h until a light brown solid was produced. The product was purified by re-dispersing in DDW thrice, followed by centrifugation and drying in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h.

Biosynthesis of bio-zinc oxide-CMC nanocomposite (BioZnONP-CMC)

Aqueous extract of Dalium guineense Stem bark (50 ml) was heated to 60 °C on a magnetic stirrer hotplate, and 5 g of Zn(NO3)2.6H2O was added with continuous stirring for 1 h. 10 cm3 of 1 M NaOH was added dropwise at the rate of 2 cm3 min−1 to adjust the pH to 12. CMC (1 g) was added, and stirring was continued for 1 h until a light brown solid was produced. The product was purified by re-dispersing in distilled water thrice, followed by centrifugation and drying in an oven at 60 °C for 5 h.

Characterization of nanoparticles

The nanomaterials ZnONPs, BioZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC were synthesized and characterized by making use of Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) (Termo Nicolet-870 spectrophotometer, USA). The crystallinity of the adsorbents was assessed using powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance powder X-ray diffraction, Bruker, USA). The surface structure and morphologies of synthesized nanomaterials were investigated using a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM). Finally, specific surface area, pore volume, and size of BioZnONPs and BioZnONPs-CMC were examined by making use of the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) nitrogen sorption–desorption method (Micromeritics Instruments Corp., USA).

Effluent sample collection

Treated and untreated effluent samples were collected from sixteen industries and designated as shown in Fig. 1. The effluent samples (treated and untreated) were collected in 2.5 L amber bottles and washed with distilled water, acetone, and n-hexane (Table 1). Thereafter, the samples were stored in an ice bath and later transferred to the lab. Effluent for potentially toxic metal analysis was collected using a HNO3 (0.05 M) pre-treated polyethylene bottle. Before the relevant analyses, samples were stored at 4 °C to prevent the degradation of the analyte.

Preparation of stock solutions

A stock solution of Cd and Pb was separately prepared by dissolving an accurately weighed amount of 1 g of lead and cadmium granules in 50 ml of 2 M nitric acid and made up to the 1 dm3 mark with deionized water. On the other hand, an accurate amount of K2Cr2O7 salt was transferred into a 1 L standard flask and made up to mark using deionized water. Thereafter, different working solutions of the metal ions were prepared daily from the 1000 mg L−1 stock solution. A flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Varian SpectrAA 100) was employed for the quantification of metal ions. Meanwhile, wavelengths of 228.9, 357.9, and 283.2 were selected for AAS analyses of Cd, Cr, and Pb, respectively.

Digestion of samples

The modified method of Aga &Brhane 2014 was used to digest the samples collected from different industries. Briefly, to a mixture of concentrated HNO3 (3 ml) and H2O2 (3 ml), a 50 ml aliquot sample was transferred and heated to an elevated temperature (70 °C) for 1 h and allowed to cool89. The solution was thereafter diluted and filtered (a glass funnel and Whatman filter) into 50 ml volumetric and made up to mark using distilled-deionized water. Blank digestion was also performed using a similar approach, and the analytes under investigation were quantified using a Varian SpectrAA 100 flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer.

Sample extraction

Preliminary cleaning of the samples was performed using a filtration technique. Analyte extraction of the samples was done using the liquid-liquid extraction technique as provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) method 3510-C90. Briefly, 500 cm3 aliquot was extracted using 40 ml of dichloromethane (DCM). Triplicate extraction of the analytes was carried out per sample, and the extract fractions were combined and concentrated to 2 ml.

Clean‑up

For the clean-up stage, a silica gel column (1 g/6 cm3 covered with 2 g anhydrous sodium sulfate and conditioned with 6 cm3 dichloromethane was used. A ratio of 2.5:1.5:1 was used to prepare a mixture of n-hexane: DCM: toluene; 50 cm3 of the mixture was used to elute the concentrated extracts. The obtained eluent portions were mixed and concentrated to dryness by rotary evaporation. Following that, the extracts acquired were redissolved in 2 cm3 n-hexane before GC-MS measurement.

GC-MS analysis

A gas chromatography equipped with an auto-sampler and coupled to an Agilent Mass Spectrophotometric Detector, model 6890 N, was employed. 1 µL of the cleaned extract was injected into a 30 m x 0.25 mm ID DB 5MS coated fused silica column with a film thickness of 0.15 µL, making use of the pulsed splitless mode. As a carrier gas, helium gas was utilized, and the column head pressure was kept constant at 20 psi to create a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. Meanwhile, conditions of operation were pre-programmed such that the Temperatures for the injector and detector were set to 270 and 300 °C, respectively while the oven temperature was set as follows: 70 °C held for 2 min, then ramp at 25 °C/min to 180 °C kept constant for 1 min, and finally ramp at 5 °C/min to 300 °C. Appropriate quality control procedures were adhered to.

Determination of physicochemical parameters

After calibrating the probes independently with the relevant calibration solution, the Hanna multi-parameter test meter was utilized to determine total dissolved solids (TDS), solution temperature, pH of the media, and electrical conductivity (EC). Each probe was immersed in the sample, and readings were stabilized before data retrieval for each parameter. Phosphate concentration was estimated by placing 10 mL of the sample into a 10 mL cuvette, and the readings were assessed using a Hanna HI83399 photometer. After zeroing the instrument, 10 drops of phosphate high range (HR) reagent A and 1 packet of phosphate HR reagent B were introduced, followed by a mild shaking of the cuvette. This mixture was placed in the photometer, allowed to stand for 5 min, and the phosphate concentration was read off.

The concentration of nitrate was evaluated by pouring a 10 mL diluted aliquot (10-fold dilution) of the sample into a 10 mL cuvette and inserting it into the photometer’s cuvette holder. The instrument was tared to ensure consistency with acquired results. After removing the cuvette, a packet of nitrate reagent was applied. The cuvette was covered, agitated forcefully for 10 s, flipped alternatively for 50 s, and positioned in the photometer’s cuvette holder before the nitrate concentration was determined after 4.5 min. The same photometer was employed to evaluate total nitrogen, chloride, and total phosphorus employing the methods and reagents indicated in the instruction handbook91,92. The biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) after a 5-day incubation duration was calculated using a modified method of Aniyikaiye et al.93. Meanwhile, 10 mL of FeCl3, NH4Cl, CaCl2, MgSO4, and Na2SO3 with 10 L were added to 10 L of distilled water. Separately, two 10 mL aliquots of each effluent were put into two 300 cm3 BOD bottles, which were subsequently filled with dilution water, also, blank solutions were in two 300 mL BOD bottles containing only dilution water. One BOD bottle containing effluent and one blank bottle were incubated at 20 degrees Celsius for ten days, while the dissolved oxygen content (DO) of the effluent in the second BOD bottle (DO1) and the blank were measured instantly with the Hanna multi-parameter test meter. Meanwhile, after 5 days, the DO of the incubated sample (DO5) and the blank were measured using the same test meter, and BOD5 was calculated as:

The Hanna COD medium and high-range reagents were used to estimate the COD of samples.

About 2 mL of deionized water containing 0.2 mL of HR was transferred to the first vail (blank) while the second vail holds 2 mL of the sample containing 0.2 mL of HR. Following mixing, the contents were digested for 2 h in a Hanna reactor (pre-heated to 150 °C) and allowed to attain room temperature. The photometer was tared with a blank before determining the COD of the samples.

Application of nanoparticles for metal and pesticide removal

0.01 g of BioZnONPs-CMC, ZnONPs, or BioZnONPs was contacted separately to 100 cm3 aliquots of the effluent samples in a stoppered 250 mL bottle. The mixture was agitated in a thermostated water bath for 180 min at 150 rpm under the sun. Thereafter, the samples were filtered through Whatman no. 1 filter paper and analyzed with AAS and GC-MS for metal ions and OCPs, respectively. The uptake capacity (mg g−1) was determined using Eq. 1:

Where qe represents the uptake capacity of the adsorbents, Co (mg dm−3) is the initial concentration of analyte in solution, V is the volume of adsorbate (dm3), W is the mass of adsorbent (g), and Ce (mg dm−3) is the equilibrium concentration of the analyte.

Statistical analysis

The physicochemical properties of each effluent sample were analyzed in triplicate. Descriptive statistics such as the parameters’ minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation were also generated to highlight their average responses and dispersions. The results were also evaluated using single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Duncan Multiple Range Test was used to compare means. SPSS software (Version 22.0) was used for statistical analysis.

Results and discussion

Characterization of nanomaterials

The crystalline structure of BioZnONPs-CMC, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs was acquired using powdered X-ray diffraction patterns and displayed in Fig. 2. The XRD patterns of ZnONPs demonstrate the 2θ values 31.77°, 34.42°, 36.25°, 47.54°, 56.60°, 62.86°, 66.38°, 67.96°, 69.10°, 72.56°, and 76.95°, which matched the different crystalline planes of ZnONP particles. These peak values relate to the crystal or lattice plane of (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (004), and (202) which confirms the pure crystalline nature of ZnONPs (see Fig. 2b). The result is in good agreement with Allah and Alshamsi (2022). The XRD patterns acquired for ZnONPs are in good agreement with Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) No.361,451. The influence of the capping agent from the plant extract and the modifier (CMC) may be responsible for the poor signals as observed for BioZnONPs-CMC and BioZnONPs (see Fig. 2a and c).

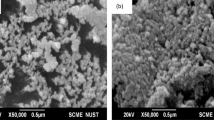

The TEM images of ZnONPs, BioZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC are displayed in Fig. 3. Uniformly distributed and aggregated spherical ZnO nanoparticles with a typical size of 12.40 ± 3.39 nm were observed for the ZnONPs. Meanwhile, an irregularly striated morphology sustained an inter-agglomeration of ZnO nanoparticles. This could be attributed to the capping agent from plant extract and CMC employed for the fabrication of BioZnONPs and BioZnONPs-CMC (see Fig. 3b and c).

The pore diameter, pore volume, and BET surface area of BioZnONPs-CMC and BioMag-CMC were acquired by making use of the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) nitrogen gas adsorption-desorption sorption measurements technique. The pore volume and BET surface area of the nanoparticles increased in the order BioZnONPs < BioZnONPs-CMC < ZnONPs (see Table 2). Pore diameter was obtained using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) theory and was observed to increase in the order ZnONPs < BioZnONPs-CMC < BioZnONPs (see Table 2). Meanwhile, the isotherms profile of BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC demonstrated a characteristic type-IV curve with a hysteresis loop within a relative pressure range (P/P0) > 0.40 and > 0.90 (see Fig. 4). Meanwhile, the occurrence of evaporation and condensation at different pressures may be responsible for this phenomenon94. To exhibit a type-IV isotherm profile suggests that the nanoparticles (ZnONPs, BioZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC) are mesoporous, and this is in close agreement with the values obtained from TEM assessment and also consistent with the report of other researchers95,96.

The FTIR spectrum revealed the existence of several functional groups on ZnONPs, BioZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC. The spectra revealed strong similarities in the nanoparticles’ bands, with a little difference in the intensity of their peaks (see Fig. 5). The broadband between 3300 and 3400 cm−1 correlated to O-H stretching, indicating the availability of hydroxyl functional groups on the surface of the nanoparticles. Sharp peaks at 1600–1640 cm−1 and 1020 − 1040 cm−1 are assigned to the stretching vibrations of the C = O and -OH groups, respectively97,98,99,100,101. The consequence of using CMC as a modifier for ZnONPs was noticed on the spectra acquired for BioZnONPs-CMC. The BioZnONPs-CMC hydroxyl band (3300 and 3400 cm−1) was observed to be broad (see Fig. 5). Furthermore, the FTIR spectrum of ZnONPs was noticed to have prominent infrared peaks between 500 and 1700 cm−1 above which the peak intensity is tremendously reduced. Meanwhile, the peak at 696 cm−1 corresponds to ZnONPs102,103.

Physicochemical properties

The liquid effluents collected from the personal care product industry (APCU), the textile industry in Kano (TKKU), soft drink industry in Kanon (SDKU), malting industry in Abia (MAAU), pesticide industry in Kano (PCKT), tannery industry in Kano (UTUK), brewery industry in Port Harcourt (RPBT), paint industry in Abia (PAAU), the pharmaceutical industry in kano (PKKT), fertilizer industry in Port Harcourt (TFRP), cement board industry in Enugu (FCTE), coal mine industry in Gombe (CMTG) and cement industry in Gombe (CAGT) were all notice to sustain colour and an unpleasant odour due to the presence of excessive organic and inorganic gaseous substances, phytoplankton and dissolved toxic mater. Hence, the physicochemical parameters (pH, Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), COD, EC, Cl− ions, TDS, total nitrogen, nitrate and PO43−, total phosphorus, and sulphate) of the aforementioned effluents were assessed. The BOD values of the samples collected from five states in Nigeria ranged between 1.5 and 42.9 mg/L. The MAAU and CAGT were observed to have the least and the highest BOD values, respectively (see Table 3). Except for MAAU and PAAU, the BOD values estimated for the effluent samples were above the permissible limit (< 6 mg/L) as provided by the World Health Organization (WHO)104. The high BOD5 level could be attributed to a high volume of bacteria/microorganisms in the industrial effluents that may be responsible for the consumption of dissolved oxygen105,106. This further justifies the awful odour of the effluents. The concentration value of BOD was noticed to reduce from 6.3 to 3.9 mg dm−3 when SDKU was treated with BioZnONPs. Meanwhile, a similar observation was made on treating TKKU with BioZnONPs-CMC. Besides SDKU and TKKU, an increased BOD5 was observed when the nanoparticles and nanocomposites were employed as wastewater treatment agents for the samples. A similar observation was made in the treatment of effluent samples collected from a catfish (Clarias gariepinus) pond at Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria, via the application of Luffa cylindrica fibre in a packed bed107. The phenomenon could be attributed to the degradation of organic molecules that generate chemical residues with deoxygenation characteristics.

The mean chemical oxygen demand (COD) concentration for APCU, TKKU, SDKU, MAAU, PCKT, UTUK, RPBT, PAAU, PKKT, TFRP, FCTE, CMTG, and CAGT was determined and presented in Table 4. The estimated values obtained after filtration varied from 162 to 7021 mg dm−3. Meanwhile, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), a permissible limit of 4 mg dm−3 is stipulated for the concentration of COD104. Hence, the values obtained for the samples were noticed to far surpass the permissible limit set by the stakeholders. The high COD values indicate high oxygen depletion. This could be attributed to the high microbial load in the industrial effluent. On the other hand, the application of BioZnONPs, BioZnONPs-CMC, and ZnONPs as wastewater treatment agents on the samples resulted in the reduction of the COD concentration. This could be due to the possible antimicrobial characteristics of the nanoparticles or the degradation of oxygen-starving molecules in the effluent samples (see Table 4). The % removal of COD by BioZnONPs, BioZnONPs-CMC, and ZnONPs was consistent with the removal of COD from industrial effluent using dates nut carbon, tamarind nut carbon, and metakaolin as wastewater treatment agents108.

It has been proven that pH is an important factor in determining the acid-base balance of water. Water’s pH level determines its utility for many purposes, and it is known to influence the accessibility of micronutrients, as well as trace and potentially toxic metals. It is well-documented that low or high pH levels are hazardous to aquatic life109. Hence, in water quality assessment and wastewater treatment plant design, validation of wastewater pH is an integral part of the process. The pH values of the thirteen industrial effluents were acquired at the point of sampling. These values were either slightly greater or less than the permissible pH range (6.5–8.5) for surface water systems110. Meanwhile, after the application of nanoparticles onto the industrial effluent, the pH of APCU, TKKU, SDKU, RPBT, PAAU, TFRP, FCTE, CMTG, and CAGT was observed to decrease. On the other hand, the pH of MAAU, PCKT, UTUK, and PKKT effluents was noticed to increase. The pH variation reflects the uniqueness of the respective industries and the nature of contaminants released by the industries. However, UTUK, TFRP, and FCTE exhibited extreme solution pH that is detrimental to aquatic life. Hence, effluents from the industries must be effectively pretreated before discharge.

In industrial effluents, the dissolved ions from degraded plant materials are primarily responsible for EC. This parameter serves as a valuable indicator of the amount of dissolved salt in the effluent. The EC data obtained for all sites ranged from 7049.55 ± 16.26 to 219.59 ± 14.14 mS/m and varied significantly (P < 0.05) for TFRP and CAGT industrial effluent, respectively. On the other hand, the EC values acquired for UTUK, RPBT, TFRP, FCTE, and APCU were higher than the allowed threshold of 1000 mS/m by WHO110. Meanwhile, the high solution pH of TFRP may induce the precipitation of polar particles in the effluent, which can enhance the EC value. The application of the nanoparticles to the effluents under investigation was noticed to elevate the EC values of the treated effluents. The degradation of the water contaminants into polar residues by the nanoparticles may be responsible for the elevated EC values after treatment.

The average chloride ion concentration of the collected industrial effluents was within the.

range of 1.44 ± 0.27 and 56.12 ± 4.84 mg dm−3. Meanwhile, the allowable limit of chloride ion concentration in surface water is 250 mg dm−3 as provided by WHO110. The highest Cl− concentration was recorded for effluent collected from the textile industry in Kano. This could be attributed to the application of excess chloride-base salts in her industrial chemical processes111. In summary, the concentration of chloride ions detected in the 13 effluents collected from five states was noticed to be below the threshold concentration. On the other hand, the application of nanoparticles as wastewater treatment agents on the effluent samples was noticed to significantly reduce the concentration of chloride ions (see Table 5). The TDS concentration in water samples retrieved from the treated and untreated industrial wastewater ranged from 111.58 ± 0.51 mg dm−3 (PKKT) to 3614.66 ± 126.57 mg dm−3 (TFRP). With reference to the threshold limit (600 mg dm−3) as provided by WHO110, UTUK, RPBT, TFRP, and FCTE demonstrated TDS loads that were higher than the permissible limit. This could be due to the discharge of toxicological additives that induce the precipitation of particles in the aquatic ecosystem. Meanwhile, TDS and EC demonstrated a significant relationship (see Table 5).

The concentration of nitrate in the sampled wastewater ranged from 57.42 ± 6.29 dm−3 (PAAU).

to 1.64 ± 0.07 dm−3 (CMTG) (Table 6,). On the other hand, a concentration range of 0.04 ± 0.001 dm−3 (CAGT) to 1.87 ± 0.34 dm−3 (RPBT) was obtained for phosphate (Table 6,). As recommended by WHO, the acceptable limits of sulphate, nitrate, and phosphate in surface water are 250 mg dm−3, 50 mg dm−3, and 5 mg dm−3, respectively112. As displayed in Table 6, the effluent sourced from the paint industry in Aba, Abia State (PAAU) had nitrate concentrations that exceeded the recommended limit. This suggests the possibility of using excess sodium nitrate or nitrate-based chemicals in the production of paint. Besides the aforementioned effluent, the concentration of nitrate in APCU, TKKU, SDKU, MAAU, PCKT, UTUK, RPBT, PKKT, TFRP, FCTE, CMTG, and CAGT was below the threshold limit. A similar trend was observed for the validation of phosphate in the 13 samples collected. On the other hand, the concentration of sulphate was observed to be below the threshold limit (see Table 7). Finally, 10 mg/L and 1.0 mg/L permissible limits for total nitrogen and total phosphorus, respectively, were recommended by WHO112. The concentration of total nitrogen in the samples collected from the industries was observed to exceed the allowed threshold concentration except for TKKU, PCKT, and CMTG. Similar observations were made for total phosphorus, except for CMTG and CAGT. Meanwhile, a significant reduction in the concentration of total phosphorus was observed after the application of the nanoparticle but the reverse was the case for total nitrogen.

Assessment of pesticides and potentially toxic metal ions in industrial wastewater samples

The concentration of Cd, Cr, and Pb metal ions in industrial wastewater samples obtained from various states in Nigeria is displayed in Table S1 (see supplementary information). The analytes were significantly present in the treated and untreated retrieved wastewater samples. The concentration of Cd estimated for APCU, TKKU, SDKU, MAAU, PCKT, UTUK, RPBT, PAAU, PKKT, TFRP, FCTE, CMTG, and CAGT was higher than the permissible limit of 0.003 mg dm−3 as stipulated by WHO110. The result obtained is consistent with the report of other authors113,114. The devastating health implications of Cd ions call for the identification and elimination of Cd compounds from the vicinity and operations of these enterprises. Hence, the application of BioZnONPs, BioZnONPs-CMC, and ZnONPs for the elimination of Cd ions from collected effluents demonstrated an average removal capacity of 0.495 ± 0.0354 mg g−1, 0.44 ± 0.0283 mg g−1, and 0.445 ± 0.0071 mg g−1, respectively (see Table 8). BioZnONPs demonstrated a superior capacity to eliminate Cd ions from industrial effluents. This could be attributed to the electrostatic interaction or complexation between the active functional groups on the surface of the nanoparticles and Cd ions115. On the other hand, the estimated concentration of Pb ions in the effluent samples was higher than the WHO and USEPA recommended maximum concentration of Pb (0.015 mg L−1) for surface water112. The concentration values obtained for APC U, TKKU, SDKU, MAAU, PCKT, UTUK, RPBT, PAAU, PKKT, TFRP, FCTE, CMTG, and CAGT were significant and should be addressed. The uptake potential of BioZnONPs, BioZnONPs-CMC, and ZnONPs for Pb was assessed and represented in Table 8. BioZnONPs were noticed to be most effective for the removal of Pb from industrial wastewater with a mean uptake potential of 0.012 ± 0.0113 mg g−1. The effectiveness of the BioZnONPs and BioZnONPs-CMC may be associated with the electrostatic interaction between the Pb ions and the hydroxyl functional groups on the surface of the nanoparticles. Meanwhile, our findings are consistent with the report on the uptake of Pb ions by ZnONPs synthesized using mangrove leaf extract116. Assessment of the chromium level in the effluent revealed the need to effectively pretreat the effluents before discharge. The Cr load of the effluent samples was noticed to be higher than the permissible concentration limit (see Table S1, supplementary information). Meanwhile, the potentially toxic metal remediation assessment of the effluents via the application of nanoparticles revealed similar results. BioZnONPs exhibited 0.065 ± 0.0071 mg g−1 for Cr removal. In summary, BioZnONPs, BioZnONPs-CMC, and ZnONPs have shown exceptional selective uptake capacity for the sequestration of potentially toxic metal ions from industrial effluents, however, BioZnONPs demonstrated good capacity and affinity for Cd, Cr and Pb even at a very low concentration.

Among the retrieved samples, industrial effluents collected from a pesticide plant in Kano (PCKT) were validated for trace pesticide (OCPs) residues (see Table S2, supplementary information). A varied concentration of these water contaminants was obtained, and this could be associated with the kind of activities within the industry. Meanwhile, dieldrin and endrin were determined to have the highest and lowest concentrations, respectively. The lower concentration of these analytes in the aquatic environment can harm aquatic life by disrupting endocrine and estrogenic activities. As a result, it is critical to pre-treat these industrial effluents before emission. Table 9 shows the concentration of the OCPs in the wastewater and the uptake potential of BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC for these water contaminants. Table 9 revealed that ZnONPs sequestered Endosulfan II, Endosulfan Sulphate, Methoxychlor, Endrin Ketone, α-BHC, and δ-BHC to a level of no detection. On the other hand, Endrin, P,P’-DDD, Endosulfan II, P,P’-DDT, Endrin aldehyde, Endosulfan Sulphate, Methoxychlor, and Endrin Ketone were not detected after the application of BioZnONPs. The effectiveness of BioZnONPs-CMC was observed in its ability to adsorb Endosulfan II, Methoxychlor, α-BHC, δ-BHC, Endrin Ketone, and Endosulfan I to a point of no detection. Furthermore, BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC were noticed to effectively reduce the concentration of the OCPs with average uptake capacity of 10.2 ± 10.182, 14.2 ± 4.526 and 14.2 ± 4.525, respectively. The effectiveness of these nanomaterials could be associated with the degradation of the OCPs by the nanoparticles and the electrostatic interaction of the chemical moieties on the surface of the nanoparticles117. Meanwhile, variations of the effluent composition could be responsible for the selective nature of the nanoparticles.

Mechanism of OCPs and potentially toxic metal ions removal by zinc oxide nanosorbent

It is imperative to validate the mechanism responsible for the simultaneous removal of OCPs and potentially toxic metals from industrial effluents using BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC. The removal of potentially toxic metal ions from aqueous solution by zinc oxide nanoparticles is solely driven by physical adsorption and oxidation/reduction by photogenerated e−/h+ pairs118. A positive zeta potential value is commonly estimated for Wurtzite-type ZnONPs, and this indicates a positively charged surface. However, recent synthetic modifications were noticed to introduce negatively charged centers like hydroxyl groups to the surface of ZnONPs, resulting in a negative zeta potential. A study estimated a zeta potential value of −23.6 mV for ZnONPs, and the negative value was attributed to the presence of negatively charged chemical moieties on the surface of ZnONPs118,119. In this study, physical adsorption is believed to be responsible for the uptake of Cd, Cr, and Pb onto BioZnONPs and ZnONPs. On the other hand, adsorption via electrostatic interaction may be responsible for the removal of Cd, Cr, and Pb by BioZnONPs-CMC (see Fig. 6). On the contrary, Vander Waals’s weak forces and hydrogen bond may be responsible for the adhesion of the OCPs to the surface of the nanoparticle which is thereafter degraded to molecular fragments. This could be due to electron excitation from the valence band to the conduction band, which results in the development of extremely active electrons in the conduction band and holes in the valence band, culminating in radical formation when appropriate frequency radiation impacts ZnO nanoparticles (see Fig. 6).

Conclusion

The indiscriminate discharge of untreated industrial effluents into the water bodies has posed a serious challenge to the water treatment plants due to the diversified chemistry of the contaminants. This work presents the physicochemical status of industrial effluents collected from Abia State, Enugu State, Gombe State, Kanu State, and Rivers State. The physicochemical parameters of the effluents varied and were noticed to exceed the recommended concentration limits. The application of BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC to the retrieved industrial effluents was observed to reduce the solution pH, EC, TDS, DO, SO42-, COD, Cl-, and total phosphorus. Physicochemical properties such as BOD, PO43- and total nitrogen were also significantly influenced. Adsorption of OCPs and potentially toxic metal ions was effective when BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC were used as adsorbents. Meanwhile, average uptake capacities of 10.2 ± 10.182, 14.2 ± 4.526, and 14.2 ± 4.525 were observed for BioZnONPs, ZnONPs, and BioZnONPs-CMC, respectively, in the removal of OCPs from industrial effluent. On the other hand, BioZnONPs (0.191 ± 0.018 mg g−1), ZnONPs (0.168 ± 0.007 mg g−1), and BioZnONPs-CMC (0.169 ± 0.025 mg g−1) demonstrated good potential for the uptake of Cd, Cr, and Pb ions from the industrial effluent. Fabrication of the nanocomposite using different synthetic routes provided us with a promising water treatment agent with good reusability, cost-effectiveness, and environmentally friendly characteristics for the simultaneous elimination of metal ions and OCPs from industrial effluents. The evaluation of the potentially toxic metal and OCPs status of these effluents is an intervention toward the sustainability of a healthy aquatic ecosystem. The application of these materials for the removal of emerging contaminants, PCBs, microplastics, PAHs, volatile organic compounds, and dyes from industrial effluent could be assessed in the future. Meanwhile, the data obtained from this work may also be considered a guide for policy-making within the Nigerian state.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the corresponding author Dr. James Friday Amaku, upon reasonable request via e-mail fridaya@vut.ac.za.

References

Ayranci, E. & Hoda, N. Adsorption kinetics and isotherms of pesticides onto activated carbon-cloth. Chemosphere 60 (11), 1600–1607 (2005).

Olisah, C., Okoh, O. O. & Okoh, A. I. Occurrence of organochlorine pesticide residues in biological and environmental matrices in Africa: A two-decade review. Heliyon 6 (3). (2020).

Saeed, M. F. et al. Pesticide exposure in the local community of Vehari district in Pakistan: an assessment of knowledge and residues in human blood. Sci. Total Environ. 587, 137–144 (2017).

Kuster, M., de Alda, M. L. & Barceló, D. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometric analysis and regulatory issues of Polar pesticides in natural and treated waters. J. Chromatogr. A. 1216 (3), 520–529 (2009).

Cosgrove, S., Jefferson, B. & Jarvis, P. Application of activated carbon fabric for the removal of a recalcitrant pesticide from agricultural run-off. Sci. Total Environ. 815, 152626 (2022).

Agrawal, A. & Sharma, B. Pesticides induced oxidative stress in mammalian systems. Int. J. Biol. Med. Res. 1 (3), 90–104 (2010).

Guan, Y. F., Wang, J. Z., Ni, H. G. & Zeng, E. Y. Organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in riverine runoff of the Pearl river delta, China: assessment of mass loading, input source and environmental fate. Environ. Pollut. 157 (2), 618–624 (2009).

Nakata, H. et al. Organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyl residues in foodstuffs and human tissues from China: status of contamination, historical trend, and human dietary exposure. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 43, 0473–0480 (2002).

Poon, B., Leung, C., Wong, C. & Wong, M. H. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides in human adipose tissue and breast milk collected in Hong Kong. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 49, 274–282 (2005).

Asawasinsopon, R. et al. The association between organochlorine and thyroid hormone levels in cord serum: a study from Northern Thailand. Environ. Int. 32 (4), 554–559 (2006).

Dalvie, M. A. et al. The long-term effects of DDT exposure on semen, fertility, and sexual function of malaria vector-control workers in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environ. Res. 96 (1), 1–8 (2004).

Dalvie, M. A. et al. The hormonal effects of long-term DDT exposure on malaria vector-control workers in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environ. Res. 96 (1), 9–19 (2004).

Hinck, J. E., Norstrom, R. J., Orazio, C. E., Schmitt, C. J. & Tillitt, D. E. Persistence of organochlorine chemical residues in fish from the tombigbee river (Alabama, USA): continuing risk to wildlife from a former DDT manufacturing facility. Environ. Pollut. 157 (2), 582–591 (2009).

Hileman, B. Environmental estrogens linked to reproductive abnormalities, cancer. Chem. Eng. News. 72 (5), 19–23 (1994).

Giannandrea, F., Gandini, L., Paoli, D., Turci, R. & Figà-Talamanca, I. Pesticide exposure and serum organochlorine residuals among testicular cancer patients and healthy controls. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. B. 46 (8), 780–787 (2011).

Corporation, S. R. & Service, U. S. P. H. Draft Toxicological Profile for Wood Creosote, Coal Tar Creosote, Coal Tar, Coal Tar Pitch, and Coal Tar Pitch Volatiles. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency (2000).

Health, U. D. & Services, H. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Toxicological profile for Lead (update) PB/99/166704. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services (1999).

Garg, U., Kaur, M., Jawa, G., Sud, D. & Garg, V. Removal of cadmium (II) from aqueous solutions by adsorption on agricultural waste biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 154 (1), 1149–1157 (2008).

Bernard, A. Cadmium & its adverse effects on human health. Indian J. Med. Res. 128 (4), 557 (2008).

Jain, N., Johnson, T. A., Kumar, A., Mishra, S. & Gupta, N. Biosorption of cd (II) on jatropha fruit coat and seed coat. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187 (7), 1–12 (2015).

Jain, C. K., Malik, D. S. & Yadav, A. K. Applicability of plant based biosorbents in the removal of heavy metals: a review. Environ. Processes. 3 (2), 495–523 (2016).

Salman, M., Athar, M. & Farooq, U. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions using Indigenous and modified lignocellulosic materials. Reviews Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology. 14 (2), 211–228 (2015).

Sreejalekshmi, K., Krishnan, K. A. & Anirudhan, T. Adsorption of Pb (II) and Pb (II)-citric acid on sawdust activated carbon: kinetic and equilibrium isotherm studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 161 (2), 1506–1513 (2009).

Nityanandi, D. & Subbhuraam, C. Kinetics and thermodynamic of adsorption of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution using puresorbe. J. Hazard. Mater. 170 (2–3), 876–882 (2009).

Lee, K., Ulrich, C., Geil, R. & Trochimowicz, H. Effects of inhaled chromium dioxide dust on rats exposed for two years. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 10 (1), 125–145 (1988).

Gad, S. et al. In Acute toxicity of four chromate salts, Chromium symposium, pp 43–58. (1986).

Thuy, P. T., Moons, K., Van Dijk, J., Viet Anh, N. & Van der Bruggen, B. To what extent are pesticides removed from surface water during coagulation–flocculation? Water Environ. J. 22 (3), 217–223 (2008).

Barka, N. et al. Kinetics and equilibrium of cadmium removal from aqueous solutions by sorption onto synthesized hydroxyapatite. Desalination Water Treat. 43 (1–3), 8–16 (2012).

Safdar, M. et al. Effect of sorption on Co (II), Cu (II), Ni (II) and Zn (II) ions precipitation. Desalination 266 (1), 171–174 (2011).

Lafi, W. K. & Al-Qodah, Z. Combined advanced oxidation and biological treatment processes for the removal of pesticides from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 137 (1), 489–497 (2006).

Badawy, M. I., Ghaly, M. Y. & Gad-Allah, T. A. Advanced oxidation processes for the removal of organophosphorus pesticides from wastewater. Desalination 194 (1–3), 166–175 (2006).

Malaeb, L. & Ayoub, G. M. Reverse osmosis technology for water treatment: state of the Art review. Desalination 267 (1), 1–8 (2011).

Senthilnathan, J. & Philip, L. Removal of mixed pesticides from drinking water system by photodegradation using suspended and immobilized TiO2. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. B. 44 (3), 262–270 (2009).

Ding, Z., Hu, X., Morales, V. L. & Gao, B. Filtration and transport of heavy metals in graphene oxide enabled sand columns. Chem. Eng. J. 257, 248–252 (2014).

Moons, K. & Van der Bruggen, B. Removal of micropollutants during drinking water production from surface water with nanofiltration. Desalination 199 (1–3), 245–247 (2006).

Yangali-Quintanilla, V., Maeng, S. K., Fujioka, T., Kennedy, M. & Amy, G. Proposing nanofiltration as acceptable barrier for organic contaminants in water reuse. J. Membr. Sci. 362 (1–2), 334–345 (2010).

Maity, S. et al. Techno-economic feasibility and life cycle assessment analysis for a developed novel biosorbent-based arsenic bio-filter system. Environ. Geochem. Health. 46 (3), 79 (2024).

Sulaymon, A. H., Sharif, A. O. & Al-Shalchi, T. K. Removal of cadmium from simulated wastewaters by electrodeposition on stainless steeel tubes bundle electrode. Desalination Water Treat. 29 (1–3), 218–226 (2011).

Reungoat, J. et al. Removal of micropollutants and reduction of biological activity in a full scale reclamation plant using ozonation and activated carbon filtration. Water Res. 44 (2), 625–637 (2010).

Petersková, M., Valderrama, C., Gibert, O. & Cortina, J. L. Extraction of valuable metal ions (Cs, Rb, Li, U) from reverse osmosis concentrate using selective sorbents. Desalination 286, 316–323 (2012).

Wong, C. W., Barford, J. P., Chen, G. & McKay, G. Kinetics and equilibrium studies for the removal of cadmium ions by ion exchange resin. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2 (1), 698–707 (2014).

Baczynski, T. P., Pleissner, D. & Grotenhuis, T. Anaerobic biodegradation of organochlorine pesticides in contaminated soil–significance of temperature and availability. Chemosphere 78 (1), 22–28 (2010).

Chiu, T. C., Yen, J. H., Liu, T. L. & Wang, Y. S. Anaerobic degradation of the organochlorine pesticides DDT and heptachlor in river sediment of Taiwan. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 72, 821–828 (2004).

Dokania, P., Maity, S., Patil, P. B. & Sarkar, A. Isothermal and kinetics modeling approach for the bioremediation of potentially toxic trace metal ions using a novel biosorbent acalypha wilkesiana (Copperleaf) leaves. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 196 (5), 2487–2517 (2024).

Maity, S., Nanda, S. & Sarkar, A. Colocasia esculenta stem as novel biosorbent for potentially toxic metals removal from aqueous system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (42), 58885–58901 (2021).

Maity, S., Patil, P. B., SenSharma, S. & Sarkar, A. Bioremediation of heavy metals from the aqueous environment using Artocarpus heterophyllus (jackfruit) seed as a novel biosorbent. Chemosphere 307, 136115 (2022).

Humbert, H., Gallard, H., Suty, H. & Croué, J. P. Natural organic matter (NOM) and pesticides removal using a combination of ion exchange resin and powdered activated carbon (PAC). Water Res. 42 (6–7), 1635–1643 (2008).

Oliveira, L. C. et al. Preparation of activated carbons from coffee husks utilizing FeCl3 and ZnCl2 as activating agents. J. Hazard. Mater. 165 (1–3), 87–94 (2009).

Salman, J. & Hameed, B. Removal of insecticide Carbofuran from aqueous solutions by banana stalks activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 176 (1–3), 814–819 (2010).

Faust, S. & Aly, O. Adsorption processes for water Treatment Butterwort Publishers. Boston, MA (1987).

Bhatnagar, A. & Sillanpää, M. Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—a review. Chem. Eng. J. 157 (2–3), 277–296 (2010).

Seyhi, B., Drogui, P., Gortares-Moroyoqui, P., Estrada‐Alvarado, M. I. & Alvarez, L. H. Adsorption of an organochlorine pesticide using activated carbon produced from an agro‐waste material. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 89 (12), 1811–1816 (2014).

Amutova, F. et al. Adsorption of organochlorinated pesticides: adsorption kinetic and adsorption isotherm study. Results Eng. 17, 100823 (2023).

Abdel-Ghani, N. T., Hefny, M. & El-Chaghaby, G. A. F. Removal of lead from aqueous solution using low cost abundantly available adsorbents. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 4 (1), 67–73 (2007).

Ramos, S. N. et al. Removal of cobalt(II), copper(II), and nickel(II) ions from aqueous solutions using phthalate-functionalized sugarcane Bagasse: Mono- and multicomponent adsorption in batch mode. Ind. Crops Prod. 79, 116–130 (2016).

Lan, J., Cheng, Y. & Zhao, Z. Effective organochlorine pesticides removal from aqueous systems by magnetic nanospheres coated with polystyrene. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 29 (1), 168 (2014).

Sen, B., Sarma, H. & Bhattacharyya, K. Effect of pH on Cu (II) removal from water using Adenanthera pavonina seeds as adsorbent. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 6 (5), 737–745 (2016).

Gebrekidan, A. et al. Acacia Etbaica as a potential low-cost adsorbent for removal of organochlorine pesticides from water. J. Water Resour. Prot. 7 (03), 278 (2015).

Feng, Q., Lin, Q., Gong, F., Sugita, S. & Shoya, M. Adsorption of lead and mercury by rice husk Ash. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 278 (1), 1–8 (2004).

Pinto, M. C. E. et al. Mesoporous carbon derived from a biopolymer and a clay: preparation, characterization and application for an organochlorine pesticide adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 225, 342–354 (2016).

Komkiene, J. & Baltrenaite, E. Biochar as adsorbent for removal of heavy metal ions [cadmium (II), copper (II), lead (II), zinc (II)] from aqueous phase. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13 (2), 471–482 (2016).

Unuabonah, E., Adebowale, K. & Olu-Owolabi, B. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of the adsorption of lead (II) ions onto phosphate-modified kaolinite clay. J. Hazard. Mater. 144 (1), 386–395 (2007).

Asgarzadeh, S., Rostamian, R., Faez, E., Maleki, A. & Daraei, H. Biosorption of Pb (II), Cu (II), and Ni (II) ions onto novel Lowcost P. eldarica leaves-based biosorbent: isotherm, kinetics, and operational parameters investigation. Desalination Water Treat. 57 (31), 14544–14551 (2016).

El-Said, W., Fouad, D., Ali, M. & El-Gahami, M. Green synthesis of magnetic mesoporous silica nanocomposite and its adsorptive performance against organochlorine pesticides. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 15, 1731–1744 (2018).

Khan, S. U. et al. Biosorption of nickel (II) and copper (II) ions from aqueous solution using novel biomass derived from Nannorrhops Ritchiana (Mazri Palm). Desalination Water Treat. 57 (9), 3964–3974 (2016).

Babarinde, A. & Onyiaocha, G. O. Equilibrium sorption of divalent metal ions onto groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) shell: kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamics. Chem. Int. 2 (1), 37–46 (2016).

Brás, I. P., Santos, L. & Alves, A. Organochlorine pesticides removal by pinus bark sorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33 (4), 631–634 (1999).

Rahmanifar, B. & Moradi Dehaghi, S. Removal of organochlorine pesticides by Chitosan loaded with silver oxide nanoparticles from water. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 16, 1781–1786 (2014).

Martín-Lara, M. A., Blázquez, G., Calero, M., Almendros, A. I. & Ronda, A. Binary biosorption of copper and lead onto pine cone shell in batch reactors and in fixed bed columns. Int. J. Miner. Process. 148, 72–82 (2016).

Markou, G. et al. Biosorption of Cu2+ and Ni2+ by Arthrospira platensis with different biochemical compositions. Chem. Eng. J. 259, 806–813 (2015).

Krishnadasan, S., Brown, R., Demello, A. & Demello, J. Intelligent routes to the controlled synthesis of nanoparticles. Lab. Chip. 7 (11), 1434–1441 (2007).

Bhaduri, S. & Bhaduri, S. Enhanced low temperature toughness of Al2O3-ZrO2 Nano/nano composites. Nanostruct. Mater. 8 (6), 755–763 (1997).

Lamas, D., Lascalea, G. & De Reca, N. W. Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline powders for partially stabilized zirconia ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 18 (9), 1217–1221 (1998).

Wang, R. C. & Tsai, C. C. Efficient synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles, nanowalls, and nanowires by thermal decomposition of zinc acetate at a low temperature. Appl. Phys. A. 94, 241–245 (2009).

Wu, J. J. & Liu, S. C. Low-temperature growth of well‐aligned ZnO nanorods by chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 14 (3), 215–218 (2002).

Ristić, M., Musić, S., Ivanda, M. & Popović, S. Sol–gel synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline ZnO powders. J. Alloys Compd. 397 (1–2), L1–L4 (2005).

Chang, S. S., Yoon, S. O., Park, H. J. & Sakai, A. Luminescence properties of Zn nanowires prepared by electrochemical etching. Mater. Lett. 53 (6), 432–436 (2002).

Ni, Y., Wei, X., Hong, J. & Ye, Y. Hydrothermal Preparation and optical properties of ZnO nanorods. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B. 121 (1–2), 42–47 (2005).

Scarisoreanu, N. et al. Properties of ZnO thin films prepared by radio-frequency plasma beam assisted laser ablation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 247 (1–4), 518–525 (2005).

Vázquez, A., López, I. A. & Gómez, I. Growth mechanism of one-dimensional zinc sulfide nanostructures through electrophoretic deposition. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 2701–2704 (2013).

Singh, O., Kohli, N. & Singh, R. C. Precursor controlled morphology of zinc oxide and its sensing behaviour. Sens. Actuators B. 178, 149–154 (2013).

Shetty, A. & Nanda, K. K. Synthesis of zinc oxide porous structures by anodization with water as an electrolyte. Appl. Phys. A. 109, 151–157 (2012).

Rajesh, D., Lakshmi, B. V. & Sunandana, C. Two-step synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles. Phys. B: Condens. Matter. 407 (23), 4537–4539 (2012).

Kooti, M. & Naghdi Sedeh, A. Microwave-assisted combustion synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles. J. Chem. 2013. (2013).

Zak, A. K. et al. Sonochemical synthesis of hierarchical ZnO nanostructures. Ultrason. Sonochem. 20 (1), 395–400 (2013).

Bhattacharya, D. & Gupta, R. K. Nanotechnology and potential of microorganisms. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 25 (4), 199–204 (2005).

El-Said, W. A., Cho, H. Y., Yea, C. H. & Choi, J. W. Synthesis of metal nanoparticles inside living human cells based on the intracellular formation process. Adv. Mater. 26 (6), 910–918 (2014).

Nnaji, J. C., Amaku, J. F., Amadi, O. K. & Nwadinobi, S. I. Evaluation and remediation protocol of selected organochlorine pesticides and heavy metals in industrial wastewater using nanoparticles (NPs) in Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 2170 (2023).

Aga, B. & Brhane, G. Determination the level of some heavy metals (Mn and Cu) in drinking water using wet digestion method of adigrat town. Int. J. Technol. 2 (10), 32–36 (2014).

EPA, M. Method 3540 C. Soxhlet extraction. URL: (1996). http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/testmethods/sw846/pdfs/3540c.pdf.

Patil, P., Sawant, D. & Deshmukh, R. Physico-chemical parameters for testing of water–A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 3 (3), 1194–1207 (2012).

Dessie, B. K. et al. An integrated approach for water quality assessment in African catchments based on physico-chemical and biological indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168326 (2024).

Aniyikaiye, T. E., Oluseyi, T., Odiyo, J. O. & Edokpayi, J. N. Physico-chemical analysis of wastewater discharge from selected paint industries in Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16 (7), 1235 (2019).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87(9–10), 1051–1069 (2015).

Abomuti, M. A., Danish, E. Y., Firoz, A., Hasan, N. & Malik, M. A. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using salvia officinalis leaf extract and their photocatalytic and antifungal activities. Biology 10 (11), 1075 (2021).

Pai, S., Sridevi, H., Varadavenkatesan, T., Vinayagam, R. & Selvaraj, R. Photocatalytic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesis using Peltophorum pterocarpum leaf extract and their characterization. Optik 185, 248–255 (2019).

Thirugnanam, T. Effect of polymers (PEG and PVP) on sol-gel synthesis of microsized zinc oxide. J. Nanomater. 2013. (2013).

Li, H. et al. Sol–gel Preparation of transparent zinc oxide films with highly Preferential crystal orientation. Vacuum 77 (1), 57–62 (2004).

Silva, R. F. & Zaniquelli, M. E. Morphology of nanometric size particulate aluminium-doped zinc oxide films. Colloids Surf., A. 198, 551–558 (2002).

Maensiri, S., Laokul, P. & Promarak, V. Synthesis and optical properties of nanocrystalline ZnO powders by a simple method using zinc acetate dihydrate and Poly (vinyl pyrrolidone). J. Cryst. Growth. 289 (1), 102–106 (2006).

Saoud, K. et al. Synthesis of supported silver nano-spheres on zinc oxide nanorods for visible light photocatalytic applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 63, 134–140 (2015).

Michrafy, A., Diarra, H., Dodds, J. A. & Michrafy, M. Experimental and numerical analyses of homogeneity over strip width in roll compaction. Powder Technol. 206 (1–2), 154–160 (2011).

Musić, S., Popović, S., Maljković, M. & Dragčević, Đ. Influence of synthesis procedure on the formation and properties of zinc oxide. J. Alloys Compd. 347 (1–2), 324–332 (2002).

WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. World Health Organ. 216, 303–304 (2011).

Hasan, M. K., Shahriar, A. & Jim, K. U. Water pollution in Bangladesh and its impact on public health. Heliyon 5(8), e02145 (2019).

Whitehead, P. G., Wilby, R. L., Battarbee, R. W., Kernan, M. & Wade, A. J. A review of the potential impacts of climate change on surface water quality. Hydrol. Sci. J. 54 (1), 101–123 (2009).

Ighalo, J. O., Adeniyi, A. G., Eletta, O. A., Ojetimi, N. I. & Ajala, O. J. Evaluation of Luffa cylindrica fibres in a biomass packed bed for the treatment of fish pond effluent before environmental release. Sustainable Water Resour. Manage. 6 (6), 120 (2020).

Parande, A. K., Sivashanmugam, A., Beulah, H. & Palaniswamy, N. Performance evaluation of low cost adsorbents in reduction of COD in sugar industrial effluent. J. Hazard. Mater. 168 (2–3), 800–805 (2009).

Gensemer, R. W. et al. Evaluating the effects of pH, hardness, and dissolved organic carbon on the toxicity of aluminum to freshwater aquatic organisms under circumneutral conditions. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 37 (1), 49–60 (2018).

Organization, W. H. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: first addendum to the fourth edition. (2017).

Mary, I. A., Ramkumar, T. & Venkatramanan, S. Application of statistical analysis for the hydrogeochemistry of saline groundwater in Kodiakarai, Tamilnadu, India. J. Coastal Res. 28 (1A), 89–98 (2012).

Organization, W. H. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. World Health Organization, Vol. 1. (2004).

Bawa-Allah, K., Saliu, J. & Otitoloju, A. Heavy metal pollution monitoring in vulnerable ecosystems: a case study of the Lagos lagoon, Nigeria. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 100, 609–613 (2018).

Agoro, M. A., Adeniji, A. O., Adefisoye, M. A. & Okoh, O. O. Heavy metals in wastewater and sewage sludge from selected municipal treatment plants in Eastern cape Province, South Africa. Water 12 (10), 2746 (2020).

Radhakrishnan, A., Rejani, P., Khan, J. S. & Beena, B. Effect of annealing on the spectral and optical characteristics of nano ZnO: evaluation of adsorption of toxic metal ions from industrial waste water. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 133, 457–465 (2016).

Al-Mur, B. A. Green zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticle synthesis using Mangrove leaf extract from Avicenna Marina: properties and application for the removal of toxic metal ions (Cd2 + and Pb2+). Water 15 (3), 455 (2023).

Carvalho, R. R. R. et al. DLLME-SFO-GC-MS procedure for the determination of 10 organochlorine pesticides in water and remediation using magnetite nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 45336–45348 (2020).

Le, A. T., Pung, S. Y., Sreekantan, S. & Matsuda, A. Mechanisms of removal of heavy metal ions by ZnO particles. Heliyon 5 (4). (2019).

Litter, M. I. Mechanisms of removal of heavy metals and arsenic from water by TiO2-heterogeneous photocatalysis. Pure Appl. Chem. 87 (6), 557–567 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to VAAL University of Technology and Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria, for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A., N.C., O.A., and F.M. conceptualized the research, conducted laboratory experiments, analyzed the obtained data, and wrote the manuscript. J.A., N.C., and J.G. supervised, read, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amaku, J.F., Chidozie, N.J., Amadi, O.K. et al. A robust assessment and treatment of selected organochlorine pesticides and heavy metals in industrial wastewater using nanoparticles: a case study in Nigeria. Sci Rep 15, 32126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03897-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03897-6