Abstract

Cosmogenic nuclei production for dating the Earth surface exposure of rock/mineral samples, especially 3He, is a robust technique in geochronology. We describe its application to constrain the ages of key eruptive episodes of the volcanic history of Deception Island (Antarctica): (i) the volcanic products of the island formed before the caldera collapse (pre-caldera material); and (ii) the caldera-forming event (syn-caldera material). High 3He/4He ratios (up to 910 RA; RA = 1.39 × 10–6) in the crystal structure of olivine phenocrysts measured through total fusion He release are much higher than the magmatic values previously obtained in the inclusions of the same olivines obtained by hydraulic crushing. Such high values indicate a cosmogenic origin and reveal an age of c. 4 Ma for the pre-caldera material, and c. 4.6 ka and 170 ka for the syn-caldera deposits. The result of c. 4.6 ka for the caldera collapse episode is consistent with previous age estimations based on tephrochronology, whereas the c. 170 ka result reveals the presence of pre-caldera olivines embedded in the syn-caldera deposits that experienced less exposure to cosmic rays compared to the samples with ages of 4 Ma. This oldest age estimate represents the first quantitative geochronological approach attempting to date Deception Island formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our main aim is to apply cosmogenic 3He (3Hecos) dating in olivines to determine the age of volcanic materials deposited before (pre) and during (syn) the caldera-forming event on Deception Island, Antarctica1. The caldera collapse on Deception Island, one of the largest volcanic eruptions confirmed in Antarctica during the Holocene, occurred between ∼8300 years2 (paleomagnetism) and ∼3980 ± 125 calibrated years Before Present (cal a BP)3 (tephrochronology based on 14C). A further aim is to compare ages determined by cosmogenic 3He ages, tephrochronology and paleomagnetism of the syn-caldera erupted tephras, to assess recent calibrations of cosmogenic nuclide production rates at south polar latitudes.

Noble gases have been widely employed to characterise the different Earth reservoirs including the mantle (e.g.,4) and to understand processes related to crustal assimilation or recycling of materials through subduction zones (e.g.,5). However, interactions of cosmic ray particles have been proven to influence the noble gas isotope production when they interact with rock surfaces (e.g., 6,7), showing characteristically different isotopic abundances from the ones of the Earth reservoirs (e.g., 7). The cosmogenic noble gases have been applied to study glaciers and ice sheets movements, the determination of rates of erosion or tectonic uplift, and for dating lava flows (e.g., 8).

In dense minerals of volcanic rocks, such as olivines, 3He can be preserved in the crystal structure through nucleogenic n, α reactions with 6Li 9,10, or in melt/fluid inclusions of mantle origin11. Once erupted and exposed at the surface, cosmic-ray spallation reactions in minerals provide an additional source of 3He and other cosmogenic noble gas isotopes. If the concentration of cosmogenic 3He is measured and the production rate known, then a surface exposure age can be calculated. Lava flows were one of the first surfaces to be studied via cosmogenic noble gases, particularly 3He coupled with K-Ar dating techniques12,13,14. Surface dating via cosmogenic noble gases has also been used to date volcanic eruptions, especially using cosmogenic 3He in olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts in basaltic samples12,13,15,16,17,18,19, and when other methods like 14C and 40Ar/39Ar dating are not suitable because the erupted rocks are very young, or both lack carbonaceous/organic material and appropriate textures, respectively8. Volcanic products are highly suitable because the relatively short duration of the exposure to cosmic rays means it is commensurate with eruption age (within age uncertainty)12,13,15,20. However, they can be affected by processes that may limit the precision of cosmogenic 3He for eruption timing, such as erosion, a potential windblown cover, or deposition of river borne sediment (e.g.,21), as well as change of altitude (e.g.,22), or even poor understanding of production rates.

We measured 3Hecos in olivine phenocrysts by stepwise heating and total fusion from four pre-caldera basaltic material (juvenile inside a syn-caldera ignimbrite, tuff, crystal-rich rock and pyroclastic breccia), and two pyroclastic density current deposits (mostly basaltic-andesitic ignimbrites) belonging to the caldera-forming event on Deception Island (Antarctica). Helium isotopic ratios of fluid/melt inclusions in the same olivine samples were previously analysed (extraction by crushing) to advance understanding of magma degassing under Deception Island and its primary source23.

Geological setting

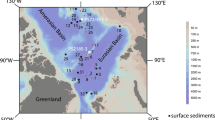

Deception Island is located on the southwestern side of Bransfield Strait (Fig. 1a), a NE-SW oriented basin 400 km long and 80 km wide24, at the northernmost part of Antarctica. Its formation is related to the back-arc rifting associated with the subduction of the Phoenix plate under the Antarctic plate during the Cenozoic, ~4 Ma ago25,26,27,28 (Fig. 1a). Spreading of the Phoenix plate slowed down 3.3 Ma ago,28,29,30,31 however subduction is still ongoing at very slow rates of 1 cm/a32.

(a) Simplified regional tectonic map and location of the South Shetland Islands (modified from86). AP: Antarctic Peninsula, BP: Bransfield Platform, BS: Bransfield Strait, HFZ: Hero Fracture Zone, SA: South America, SFZ: Shackleton Fracture Zone, SST: South Shetland Trench. (b) Deception Island orthophotomap (data obtained from Spatial Data Infrastructure for Deception Island SIMAC)87. BAD: Argentinian Base (Base Argentina Decepción). BEGC: Spanish Base (Base Española Gabriel de Castilla). BS: British Station (destroyed). CS: Chilean Station (destroyed). Black dots wihin Port Foster indicate submarine volcanic edifices.

Deception Island (Fig. 1b, 2a) is a 30 km basal diameter composite volcano, which rises from ~1400 m below sea level up to ~ 540 m above sea level33,34. The emerged part of the volcano is a horseshoe-shaped island that is 15 km in diameter, whose central part is occupied by a sea-flooded volcanic collapse caldera (Port Foster) with dimensions of about 6 × 10 km, and a maximum water depth of ~ 190 m (Fig. 1b). The caldera-forming eruption was the most remarkable event in Deception Island’s geological history, dividing the evolution of the island in to three main stages: pre-caldera, syn-caldera and post-caldera1. The pre-caldera stage was characterized by the coalescence of multiple seamounts (Fumarole Bay Formation) that led to a subaerial volcanic shield (Basaltic Shield Formation)34,35 (and references therein). The available geochronological database for the eruptions during this pre-caldera period yield ages ranging from < 100 ka (lithostratigraphy)36, 0.75 Ma (paleomagnetism and K-Ar data)37, to < 12 ka (paleomagnetism)2. The syn-caldera deposits correspond to the Outer Coast Tuff Formation (OCTF)1,35,36, a massive unit composed of pyroclastic density current deposits (50-70 m average thickness) corresponding to c. of 60 km3 of erupted magma1.

(a) Simplified geological map of Deception Island (modified from1,39). Shapefiles and Digital Elevation Model obtained from the SIMAC geodatabase87. (b) Detail of Deception Island orthophotomap showing the Vapour Col outcrop area (data obtained from Spatial Data Infrastructure for Deception Island SIMAC)87. (c) Photograph showing the Outer Coast Tuff Formation forming the cliffs along Kendall Terrace, and the hand-specimen aspect of the samples hosting the olivine-bearing juvenile pre-caldera material (i.e. dark lithics). (d) Image of the Vapour Col outcrop showing post-caldera deposits unconformably overlying the syn-caldera OCTF deposits. (e) Image of the Fumarole Bay outcrop.

The post-caldera stage is characterised by at least 30 eruptions distributed along 70 eruptive vents mostly located within the caldera (e.g.,1,38,39,40) and is marked by a caldera sea flooding event forming Port Poster, the timing of which could not be constrained by K-Ar dating but is considered to have occurred within the last few thousand years41. This stage includes the historical eruptive activity (1829-1970), which has mainly consisted of monogenetic small volume eruptions (<0.1 km3 of erupted magma) (e.g.,40,42) with different degrees of explosivity depending on the amount and provenance of water (e.g. seawater, aquifers, ice) that interacted with the ascending magma40,42,43,44,45,46.

The volcanic rocks of Deception Island (bulk rock and glasses) are tholeiitic, ranging from basalts to trachydacites and rhyolites (e.g.,35,47,48), with no significant differences among pre-, syn-, and post-caldera rocks in terms of trace element compositions48. Samples DI-35 and DI-36 belong to the OCTF syn-caldera unit, whereas olivine phenocrysts in sample DI-68 represent juvenile fragments from the pre-caldera units inside the OCTF (e.g.,23,46,48). Pre-caldera samples with no cosmogenic 3He signal, DI-18, DI-67 and PRR-10298, correspond to a tuff, crystal rich rock and pyroclastic breccia, respectively. Olivine phenocrysts are commonly subhedral- to euhedral for all studied samples.

Previous stable isotope and noble gas studies on Deception Island have focused on magmatic activity beneath the volcano. Samples studied include fumaroles and hot springs gases 49,50, and fluid/melt inclusions in olivine phenocrysts23,46. Padron et al. 50 described an increase in the 3He/4He ratio (7.1-7.5 RA; where RA is 3He/4He normalized to the 3He/4He ratio of the atmosphere, 1.39 x 10-6 = 1 RA), relative to that previously studied (6.3-7.0 RA)49 , which was attributed to a magmatic input beneath Deception Island. 3He/4He ratios of 7.2-8.7 RA were reported for the pre-caldera stage and 5.1-7.0 RA for the syn-caldera sample23. 4He/20Ne ratio is a sensitive tracer of atmospheric contamination and results show a range of values from ca. 0.0001 up to >200 (Table 1), significantly greater than atmospheric ratio (0.318). A correction for atmospheric He has been applied to the measured He isotope ratios (e.g.,51), however this correction is small to negligible for the samples with the highest 4He/20Ne ratios. Combining this with 4He/20Ne and 4He/40Ar* ratios (40Ar* refers to 40Ar corrected for an atmospheric argon component), a MORB-like magmatic source slightly modified by a subduction component could be established23.

Results

The pre-caldera DI-68 olivines shows the highest 3He/4He ratios of 910 RA released in the 2000ºC heating step (Fig. 2, Table 1). We note that these are higher than the Solar and the Solar wind values of 280 ± 20 RA52, and 330 ± 6 RA53 , respectively. Fusion of residual crushed powders of pre-caldera olivine samples DI-18, DI-67 and PRR-10298 yielded lower 3He/4He values of 7.0, 4.4 and 5.7 RA, respectively, which are below their magmatic ratios (7.2, 8.7 and 8.1 RA, respectively23). Whereas syn-caldera DI-35 and DI-36 olivines are up to 27 and 43 RA, respectively (Table 1). The 3He/4He values are significantly higher than those of magmatic 3He/4He ratios obtained with crushing of olivines, indicating the presence of cosmogenic 3He in the samples. One exception is a low 3He/4He ratio of 2.1 RA observed in the 800ºC fraction of step-heating of DI-35 olivine (Table 1), which might be contaminated by either atmospheric/radiogenic He in a small amount of groundmass persistently sticking to the sample, or to U-rich inclusions within this mineral aliquot. The high 3He/4He values obtained by fusion (i.e., cosmogenic) plot above the MORB mantle endmember (8 RA54), yet their values by crushing (i.e., magmatic) are around MORB23 (Table 1). The 4He/20Ne ratios of the olivines obtained by heating are significantly lower than those obtained with crushing the olivines separated from the same samples (1-20023, the MORB-source mantle (>1000) and the air (0.3184,55). The low 4He/20Ne ratios would result from air-derived 20Ne contamination on the sample surface (20Ne is not a cosmogenic isotope), which is supported by the atmospheric isotopic compositions of Ne (Table 1).

Applying the average of the most recently proposed production rates of 124 atoms/g/a56 to the syn-caldera samples, the exposure ages of the ejected material at sea level are 4.8 ka and 0.18 Ma (DI-36 and DI-35, respectively, Table 1), whereas the age value for the pre-caldera material is 5.0 Ma (Table 1). After applying an altitude correction57,58 the ages increase to 6.7 ka and 0.25 Ma (DI-36 and DI-35, respectively), and 5.9 Ma for the pre-caldera sample (Table 1) (i.e. uncertainties of 0.07 and 0.0019 Ma for the syn-caldera episodes, and 0.85 Ma for the pre-caldera material). If applying a higher production rate (reasonable for high latitudes, e.g.,59) of up to 180 atoms/g/a, the age values (corrected for altitude) decrease to 4.6 ka and 0.17 Ma for the syn-caldera olivines and 4.0 Ma for the pre-caldera ones (Table 1) (i.e. variations of 0.05 and 0.0013 Ma for the syn-caldera episodes, and 0.58 Ma for the pre-caldera material). Reasons for the large (factor 38) difference in exposure between syncaldera samples DI-35 and DI-36 will be considered in the next section.

Discussion and conclusions

Cosmogenic helium in Deception Island

The stepwise heating of olivine phenocrysts to extract the trapped noble gases is the most favourable procedure to release cosmogenic noble gases due to the good retention of He and Ne in olivine (e.g.,12,20,60,61,62). It is generally accepted that crushing releases magmatic (non-cosmogenic) noble gases trapped in fluid/melt inclusions mineral grains, even if minor cosmogenic “contamination” released by crushing has been described by e.g.,63. Hence, in order to date the minerals by using the cosmogenic component, melting the sample (total fusion) is preferred because the cosmogenic component is preserved within the crystal structure of the olivines8. Therefore, since the studied samples were firstly crushed to retrieve the magmatic signal23, the 3He/4He ratios obtained by stepwise heating (up to 1800-2000 ºC) is considered to be mostly cosmogenic helium (Fig. 3).

(a) Sketch showing the cosmic rays’ penetration within the outcrop. The highest cosmogenic He isotopic signal occurs at the surface of the rock (black-bold arrows) decreasing progressively inward (white-dashed arrows). However, the magmatic signal of the He isotopic ratio (c. 7–8 RA23), remains independent of the cosmic activity. The inset box indicates the place in the dark lithics where the studied olivines were extracted. (b) 3He/4He vs. 4He/20Ne diagram highlighting the difference between the noble gas magmatic values (black circles) retrieved from crushing the olivine crystals (gas released from fluid and melt inclusions; FI, MI), and the cosmogenic values (crosses) in the relict powder of the crushed olivines through total fusion. White starts: MORB and AIR 3He/4He values. The two inserted pictures show one of the studied olivine crystals extracted and separated from the rock in (a), and the powder aspect of the olivine crystals before total fusion and after crushing.

High 3He/4He ratios (Table 1, Fig. 3) of up to 910 RA (DI-68) are much higher than MORB values or any other mantle He isotopic ratio (e.g.,5) and in Deception Island23, can only be explained by cosmic ray interactions with the rocks exposed on the surface. Values of the syn-caldera samples (up to 43 RA; DI-35, DI-36) are among the highest values for oceanic islands basalts (OIB) with ratios up to 35-43 RA (e.g., Northwest Iceland64) However, Deception Island is not related to OIB and lies within a back-arc geodynamic setting (e.g.,48). This confirms that the syn-caldera samples with higher He isotopic ratios than typical MORB rocks measured by stepwise heating are also enriched by 3Hecos.

Pre-caldera samples DI-18, DI-67, and PRR-10298 were not analysed by crushing and stepped heating released He with 3He/4He between 4.4-6.9 RA. This is slightly below the 3He/4He value of 7.1 Ra obtained by crushing of pre-caldera samples DI-68 assumed to be of magmatic origin. This indicates these samples were not exposed to cosmic rays throughout most of their geological history. Minor differences in 3He/4He may be attributed to: (i) partial release of 3Hecos during crushing DI-68; (ii) addition of 4He by α decay of uranium- and thorium-rich inclusions in the olivine; and (iii) natural variations in 3He/4He of the magmatic source of the pre-caldera samples. The pre-caldera olivine phenocrysts are likely to have been covered by their host lava, snow, or soil for a significant time during their history, or were still subaqueous before the emergence of the island. Hence, for the same lava unit, or eruptive episode, the maximum exposure age in this study should be taken as the minimum eruption age estimate because it does not account for any periods of burial or erosion of the surface.

Ages of pre- and syn-caldera deposits: volcanic and geodynamic implications

Mechanisms such as atmospheric shielding, deposit mantling, tectonic elevation changes, altitude-latitude and denudation rates need to be accounted for when correcting the inferred ages in any geochronological study. The atmosphere at sea level equals to 3.5 m thickness of rock8 and the flux of cosmic rays is attenuated exponentially below the Earth’s surface65, which can be reduced further if some snow/ice is present covering the rock in winter. The attenuation coefficient of cosmic rays penetrating the rocks in Antarctica is estimated around 150 g/cm2 66. Samples analysed in this study were collected at the exposed surface of the outcrops (Fig. 2), i.e., at the atmosphere-surface interface, where the production decreases exponentially with depth being relatively constant in the top 4 cm of a surface67, thus we may consider only a minor depth shielding effect.

Erosion on Deception Island is mostly by sea wave action along the coasts and glacier activity on land 68, whereas wind erosion is negligible69. The permeable nature of surface deposits (e.g., loose recent tephra) limits the effects of fluvial erosion. Both shielding and erosion rates ‒despite their uncertainties‒ are considered to be minor on Deception Island, consequently the cosmogenic ages represent minimum estimates. An additional uncertainty in the cosmogenic isotope production rate is related to the variations in the intensity and orientation of the geomagnetic field over time, especially on surfaces exposed for 50 ka or less below 60ºN/S (e.g.,17,70). The Deception Island latitude (i.e., avg. 63º S) and the prolonged exposure period (mainly for the pre-caldera samples) suggest a negligible impact on the cosmogenic isotope production due to geomagnetic field variations. The small altitude difference among all samples implies a minor effect (up to 0.4 times higher production rate at 150 m high with respect to the sea-level) on the cosmogenic production rates (e.g.19,57,71,72) slightly increasing the age estimates (Table 1). This also suggests negligible increase in erosion rate at lower altitudes73.

The ages for the syn-caldera materials are between 4.6 ka (DI-36) to 0.25 Ma (DI-35) (depending on the production rates used of 124-180 atoms/g/a) (Table 1). The significant difference between samples DI-35 and DI-36 may be due to sample DI-36 experiencing part of its history being partially buried beneath the surface (higher shielding) and/or having a slower denudation rate (Fig. 3). We therefore conclude that the c. 6.7 - 4.6 ka result (DI-36) is reasonably consistent with the previous estimate of the caldera-collapse event of c. 8300 years based on paleomagnetic studies2 and 3980 cal a BP using tephrochronology on Byers Peninsula in Livingston Island3. The oldest cosmogenic age (0.25 - 0.17 Ma) of the syn-caldera episode is explained by olivine phenocrysts in pre-caldera clasts of older basalts being ripped-out and embedded in the DI-35 syn-caldera deposits (see also23).

The pre-caldera olivines embedded in the OCTF yield 3Hecos ages between 5.9 and 4.0 Ma depending on the production rates of 124-180 atoms/g/a (Table 1). This represents the first quantitative estimate for one of the oldest eruptions forming the island, i.e., during the first phase of the pre-caldera event, which correlates with the Bransfield spreading activity, which started 4 Ma ago25 and slowed down at 3.3 Ma29,31. Previous investigations also showed Deception Island on a geodynamic map with the Bransfield opening at c. 4 Ma74. Therefore, the age obtained for DI-68 is consistent with existing geodynamic models.

Based on the preceding discussion, we find that a cosmogenic production rate of c. 180 3He atoms/g/a in southern polar latitudes is more suitable (with lower uncertainty values as well) than the currently assumed of c. 124 3He atoms/g/a56. This higher rate might be related to the persistent low atmospheric pressure and/or potential variations in the geomagnetic field during the Holocene (e.g.,75).

Future studies will be needed to increase the sample density of the pre-caldera units, as the geomagnetic field may have varied during the last 4 Ma, thus affecting the cosmogenic isotope production8. In fact, geomagnetic field variations between 19 to 55 mT have been reported during the Quaternary76. Control on collecting samples progressively deeper below the surface of the outcrop may also enhance the knowledge of cosmic ray penetration and noble gas retention.

Material and methods

The studied samples were collected at Kendall Terrace (DI-67, DI-68), Vapour Col (DI-35, DI-36) and Fumarole Bay (DI-18, PRR-10298) (Figs. 2a, b; Table 1) during the Spanish Antarctic Campaign in 2010-2011. Kendall Terrace is formed by an extensive lava flow located at the northwest side of the volcano outside the caldera rims. It terminates at the sea with a > 50 m high cliff mostly composed by OCTF deposits68 (Fig. 2c). Vapour Col, located in the southwest part of Port Foster Bay (Figs. 2b, d), was supposedly formed by at least, two explosive eruptive events after the caldera collapse45. The formation of these craters led to the exposure of a >20 m - high cliff of OCTF deposits covered by post-caldera materials (Fig. 2d). Fumarole Bay Formation corresponds to the first pre-caldera period with low-energy erupted tephras from multiple centres likely emitted by subaqueous fire fountaining during the initial emergence of the volcano36.

All samples were collected in the horizontal (not sloped surfaces) from the highest levels of their exposed open surfaces (Table 1), that were sediment/rock/soil free and standing above the main flow surface (samples deposited from pyroclastic density current and pryroclastic breccia), and on top of a cliff (e.g., DI-68). This implies an effective sampling for a cosmogenic target (e.g.,17,65,77).

Samples were crushed in an agate mortar and sieved (mesh size of 250-400 µm) to separate and handpick the cleanest olivine crystals (i.e,. avoiding any adhering patina glass) under a binocular microscope (Fig. 3; see also23). Samples were ultrasonically cleaned using acetone and loaded into a gas extraction system where they were baked at 120 ºC overnight while being pumped to ultra-high-vacuum. Noble gas extraction consisted firstly of single-step hydraulic crushing (30 MPa during 30 seconds) in our previous study23 that determined the magmatic He isotopic signals and minimized the release of matrix-sited components (e.g.,5,78), followed in the present study by stepwise heating of the crushed powder at between 800ºC to 2000ºC to achieve total fusion of olivine in a Ta-ribbon furnace79. Combining He isotope data obtained by different gas extraction techniques means that the, cosmogenic 3He can be resolved from any magmatic 3He remaining in the sample following crushing (e.g.,56,80,81). Noble gas isotope analyses of the extracted gases were carried out using MS-IV (modified VG-5400) mass spectrometer in the University of Tokyo, Japan, (for more details on the procedure82). An additional analysis of sample DI-36 was made using a Thermo-Helix-SFT mass spectrometer at Laboratorio de Isótopos Estables (University of Salamanca, Spain) where a CO2 laser was used to heat the sample in a single step to total fusion (e.g.,83). Furnace blanks were routinely analysed before sample measurements and as an additional calibration to ensure noble gas blank levels were low and the spectrometer’s sensitivity and tune settings were consistent. The HESJ (Helium Standard of Japan; R/RA = 20.6384) and a calibration bottle containing air (R/RA =1), were the standards used for He isotope analyses in Tokyo and Salamanca, respectively.

At high latitudes (> 60º), 3He production rates at sea level are expected to be between 100-180 atoms/g/a (e.g.,4,8,56,58,59,80,85). Given that the samples were collected at elevations of up to 150 m, we applied equations for altitude correction57,58. Based on the chemistry of the olivines (forsterite (Fo)<82; the syn-caldera olivines, i.e., samples DI-35 and DI-36, have Fo ranges of 77-86 mol %, whereas the pre-caldera DI-68 is Fo78-8048), a rate of 103 atoms/g/a has been proposed80, which has more recently been refined to 124 ± 11 atoms/g/a56.

The 3He concentrations in Table 1 used to calculate the cosmogenic ages have been corrected for a magmatic contribution. However, no correction has been applied to correct for a radiogenic 4He contribution due to the small concentration of U and Th in the lavas (Th = 0.3 - 1.4 ppm, and U = 0.11 - 0.41 ppm48) hosting the olivines, and their young eruption ages. According to the parameters in the 4He production equations81, such low U and Th concentrations yield R factor values > 0.99, independent of the olivine-lava partition coefficients for U and Th and eruption ages. When R is near 1, the radiogenic 4He correction is simplified to assume that magmatic 3He/4He is equal to that obtained by crushing, and all the 4He released by total fusion is of only magmatic origin. To check the consistency of the results produced in this study for the caldera-forming episode, we compared our ages to the most recent ages obtained by palaeomagnetism2 and those based on tephrochronology studies3.

Data availability

All data analysed and generated during this study are included in this published article and would be archived at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org) a general-purpose open-access repository developed under the European OpenAIRE program.

References

Martí, J., Geyer, A. & Aguirre-Diaz, G. Origin and evolution of the Deception Island caldera (South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Bull. Volcanol. 75, 732 (2013).

Oliva-Urcia, B. et al. Paleomagnetism from Deception Island (South Shetlands archipelago, Antarctica), new insights into the interpretation of the volcanic evolution using a geomagnetic model. Int. J. Earth Sci. (Geol. Rundsch.) 105, 1353–1370 (2016).

Antoniades, D. et al. The timing and widespread effects of the largest Holocene volcanic eruption in Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 8, 17279 (2018).

Ozima, M. & Podosek, F. A. Noble Gas Geochemistry. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), (2001).

Hilton, D. R., Fischer, T. P. & Marty, B. Noble gases and volatile recycling at subduction zones. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 319–370 (2002).

Paneth, F. A., Reasbeck, P. & Mayne, K. I. Helium 3 content and age of meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2, 300–303 (1952).

Marti, K., Eberhardt, P. & Geiss, J. Spallation, fission, and neutron capture anomalies in meteoritic krypton and xenon. Zeits. Naturforschung A 21, 398–426 (1966).

Niedermann, S. Cosmic-Ray-Produced Noble Gases in Terrestrial Rocks: Dating Tools for Surface Processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 731–784 (2002).

Aldrich, L. T. & Nier, A. O. The Occurrence of 3He in Natural Sources of Helium. Phys. Rev. 74, 1590–1594 (1948).

Morrison, P. & Pine, J. Radiogenic Origin of the Helium Isotopes in Rock. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 62, 71–92 (1955).

Stuart, F. M., Lass-Evans, S., Godfrey Fitton, J. & Ellam, R. M. High 3He/4He ratios in picritic basalts from Baffin Island and the role of a mixed reservoir in mantle plumes. Nature 424, 57–59 (2003).

Kurz, M. D. Cosmogenic helium in a terrestrial igneous rock. Nature 320, 435–439 (1986).

Kurz, M. D. In situ production of terrestrial cosmogenic helium and some applications to geochronology. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 50, 2855–2862 (1986).

Cerling, T. E. Dating geomorphologic surfaces using cosmogenic 3He. Quatern. Res. 33, 148–156 (1990).

Craig, H. & Poreda, R. J. Cosmogenic 3He in terrestrial rocks: The summit lavas of Maui. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 83, 1970–1974 (1986).

Marti, K. & Craig, H. Cosmic-ray-produced neon and helium in the summit lavas of Maui. Nature 325, 335–337 (1987).

Licciardi, J. M., Kurz, M. D. & Curtice, J. M. Cosmogenic 3He production rates from Holocene lava flows in Iceland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 246, 251–264 (2006).

Fenton, C. R. & Niedermann, S. Surface exposure dating of young basalts (1–200 ka) in the San Francisco volcanic field (Arizona, USA) using cosmogenic 3He and 21Ne. Quat. Geochronol. 19, 87–105 (2014).

Doll, P. et al. Cosmogenic 3He chronology of postglacial lava flows at Mt Ruapehu, New Zealand. Geochronol. 6, 365–395 (2024).

Staudacher, T. & Allègre, C. J. Ages of the second caldera of Piton de la Fournaise volcano (Réunion) determined by cosmic ray produced 3He and 21Ne. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 119, 395–404 (1993).

Foeken, J. P. T., Day, S. & Stuart, F. M. Cosmogenic 3He exposure dating of the Quaternary basalts from Fogo, Cape Verdes: Implications for rift zone and magmatic reorganisation. Quat. Geochronol. 4, 37–49 (2009).

Blard, P.-H. et al. An inter-laboratory comparison of cosmogenic 3He and radiogenic 4He in the CRONUS-P pyroxene standard. Quat. Geochronol. 26, 11–19 (2015).

Álvarez-Valero, A. M. et al. Noble gas isotopes reveal degassing-derived eruptions at Deception Island (Antarctica): implications for the current high levels of volcanic activity. Sci. Rep. 12, 19557 (2022).

Fretzdorff, S. & Smellie, J. L. Electron microprobe characterization of ash layers in sediments from the central Bransfield basin (Antarctic Peninsula): evidence for at least two volcanic sources. Antarct. Sci. 14, 412–421 (2002).

Barker, P. F. The Cenozoic subduction history of the Pacific margin of the Antarctic Peninsula: ridge crest–trench interactions. J. Geol. Soc. 139, 787–801 (1982).

Dalziel, I. W. D. Tectonic evolution of a forearc terrane, southern Scotia Ridge, Antarctica. in Tectonic Evolution of a Forearc Terrane, Southern Scotia Ridge, Antarctica (ed. Dalziel, I. W. D.) (Geological Society of America, 1984).

McCarron, J. J. & Larter, R. D. Late Cretaceous to early Tertiary subduction history of the Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geol. Soc. 155, 255–268 (1998).

Burton-Johnson, A., Bastias, J. & Kraus, S. Breaking the Ring of Fire: How Ridge Collision, Slab Age, and Convergence Rate Narrowed and Terminated the Antarctic Continental Arc. Tectonics 42, e2022TC007634 (2023).

Lawver, L. et al. Distributed, active extension in Bransfield basin Antarctic Peninsula: Evidence from multibeam bathymetry. GSA Today 6, 1–6 (1996).

Henriet, J. P., Meissner, R., Miller, H., The Grape Team. 1992 Active margin processes along the Antarctic Peninsula. Tectonophysics 201, 229–253 (1992).

Livermore, R. et al. Autopsy on a dead spreading center: The Phoenix Ridge, Drake Passage. Antarct. Geol. 28, 607–610 (2000).

Robertson Maurice, S. D., Wiens, D. A., Shore, P. J., Vera, E. & Dorman, L. M. Seismicity and tectonics of the South Shetland Islands and Bransfield Strait from a regional broadband seismograph deployment. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JB002416 (2003).

Luzón, F., Almendros, J. & García-Jerez, A. Shallow structure of Deception Island, Antarctica, from correlations of ambient seismic noise on a set of dense seismic arrays. Geophys. J. Int. 185, 737–748 (2011).

Geyer, A. et al. Chapter 7.1 Deception Island. Memoirs 55, 667–693 (2021).

Smellie, J. L. Volcanic hazard. In: (eds. López-Martínez, J., Smellie, J. L., Thomson, J. W. & Thomson, M. R. A.), (British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, 2002).

Smellie, J. L. Lithostratigraphy and volcanic evolution of Deception Island South Shetland Islands. Antarct. Sci. 13, 188–209 (2001).

Valencio, D. A., Mendía, JoséE. & Vilas, J. F. Palaeomagnetism and K sbnd Ar age of Mesozoic and Cenozoic igneous rocks from Antarctica. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 45, 61–68 (1979).

Orheim, O. A 200-Year Record of Glacier Mass Balance at Deception Island, Southwest Atlantic Ocean, and Its Bearing on Models of Global Climatic Change. (1972).

J.L. Smellie & López-Martínez, J. Geology and geomorphology of Deception Island, 1:25000. In López-Martínez, J.; Smellie, J.L., Thomson, J.W. & Thomson, M.R.A., eds., Geology and Geomorphology of Deception Island, British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, UK. (2002).

Pedrazzi, D. et al. Historic hydrovolcanism at Deception Island (Antarctica): implications for eruption hazards. Bull. Volcanol. 80, 11 (2017).

Hopfenblatt, J. et al. Formation of Stanley Patch volcanic cone: New insights into the evolution of Deception Island caldera (Antarctica). J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 415, 107249 (2021).

Baker, P. E., Mcreath, I., Harvey, M. R., Roobol, M. J. & Davies, T. G. The Geology of the South Shetland Islands: Volcanic evolution of Deception Island. Survey Sci. Rep. 78, 81 (1975).

Smellie, J. L. Geology. in (eds. López-Martínez, Smellie, J. L., Thomson, J. W. & Thomson, M. R. A.) 11–30 (British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, 2002).

Pedrazzi, D., Aguirre-Díaz, G., Bartolini, S., Martí, J. & Geyer, A. The 1970 eruption on Deception Island (Antarctica): eruptive dynamics and implications for volcanic hazards. J. Geol. Soc. 171, 765–778 (2014).

Pedrazzi, D., Kereszturi, G., Lobo, A., Geyer, A. & Calle, J. Geomorphology of the post-caldera monogenetic volcanoes at Deception Island, Antarctica: Implications for landform recognition and volcanic hazard assessment. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 402, 106986 (2020).

Álvarez-Valero, A. M. et al. δD and δ18O variations of the magmatic system beneath Deception Island volcano (Antarctica): Implications for magma ascent and eruption forecasting. Chem. Geol. 542, 119595 (2020).

Aparicio, A., Risso, C., Viramonte, J., Menegatti, M. & Petrinovic, I. E. volcanismo de isla decepcion (Peninsula Antartica). Boletin Geol. Minerol. 108, 19–42 (1997).

Geyer, A. et al. Deciphering the evolution of Deception Island’s magmatic system. Sci. Rep. 9, 373 (2019).

Kusakabe, M. et al. Noble gas and stable isotope geochemistry of thermal fluids from Deception Island Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 21, 255–267 (2009).

Padrón, E. et al. Geochemical evidence of different sources of long-period seismic events at Deception volcano, South Shetland Islands Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 27, 557–565 (2015).

Italiano, F. et al. Noble gases and rock geochemistry of alkaline intraplate volcanics from the Amik and Ceyhan-Osmaniye areas SE Turkey. Chem. Geol. 469, 34–46 (2017).

Ozima, M., Suzuki, T. K., Yamada, A. & Podosek, F. A. Noble gas isotopic fractionation between solar wind and the Sun, and implications for Genesis solar wind oxygen measurements. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 47, 2049–2055 (2012).

Heber, V. S. et al. Noble gas composition of the solar wind as collected by the Genesis mission. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 7414–7432 (2009).

Graham, D. W. Noble Gas Isotope Geochemistry of Mid-Ocean Ridge and Ocean Island Basalts: Characterization of Mantle Source Reservoirs. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 247–317 (2002).

Sano, Y. & Wakita, H. Geographical distribution of 3He/4He ratios in Japan: Implications for arc tectonics and incipient magmatism. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 90, 8729–8741 (1985).

Blard, P.-H. Cosmogenic 3He in terrestrial rocks: A review. Chem. Geol. 586, 120543 (2021).

Kurz, M. D., Colodner, D., Trull, T. W., Moore, R. B. & O’Brien, K. Cosmic-ray exposure dating with in-situ produced cosmogenic He-3-results from young Hawaiian lava flows. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 97, 177–189 (1990).

Martin, L. C. P. et al. The CREp program and the ICE-D production rate calibration database: A fully parameterizable and updated online tool to compute cosmic-ray exposure ages. Quat. Geochronol. 38, 25–49 (2017).

Cerling, T. E. & Craig, H. Geomorphology and in-ssitu cosmogenic isotopes. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 22, 273–317 (1994).

Staudacher, T. & Allègre, C. J. Cosmogenic neon in ultramafic nodules from Asia and in quartzite from Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 106, 87–102 (1991).

Sarda, P., Staudacher, T., Allègre, C. J. & Lecomte, A. Cosmogenic neon and helium at Réunion: measurement of erosion rate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 119, 405–417 (1993).

Schäfer, J. M. et al. The oldest ice on Earth in Beacon Valley, Antarctica: new evidence from surface exposure dating. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 179, 91–99 (2000).

Moreira, M. & Madureira, P. Cosmogenic helium and neon in 11 Myr old ultramafic xenoliths: Consequences for mantle signatures in old samples. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., (2005).

Breddam, K. & Kurz, M. Helium Isotopic Signatures of Icelandic Alkaline Lavas. AGU Fall Meeting Abstr. 1, 1025 (2001).

Dunne, J., Elmore, D. & Muzikar, P. Scaling factors for the rates of production of cosmogenic nuclides for geometric shielding and attenuation at depth on sloped surfaces. Geomorphology 27, 3–11 (1999).

Brown, E. T., Brook, E. J., Raisbeck, G. M., Yiou, F. & Kurz, M. D. Effective attenuation lengths of cosmic rays producing 10Be AND 26Al in quartz: Implications for exposure age dating. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19, 369–372 (1992).

Masarik, J. & Reedy, R. C. Terrestrial cosmogenic-nuclide production systematics calculated from numerical simulations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 136, 381–395 (1995).

López-Martínez, J., Smellie, J. Geology and Geomorphology of Deception Island. (2002).

Smith, K. L. et al. Weather, ice, and snow conditions at Deception Island, Antarctica: long time-series photographic monitoring. Deep Sea Res. Part II 50, 1649–1664 (2003).

Gosse, J. C. & Stone, J. O. Terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide methods passing milestones toward paleo-altimetry. EOS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 82, 82–89 (2001).

Gayer, E. et al. Cosmogenic 3He in Himalayan garnets indicating an altitude dependence of the 3He/10Be production ratio. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 229, 91–104 (2004).

Amidon, W. H., Farley, K. A., Burbank, D. W. & Pratt-Sitaula, B. Anomalous cosmogenic 3He production and elevation scaling in the high Himalaya. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 265, 287–301 (2008).

Summerfield, M. A. et al. Long-term rates of denudation in the Dry Valleys, Transantarctic Mountains, southern Victoria Land, Antarctica based on in situ produced cosmogenic 21Ne. Geomorphology 27, 113–129 (1999).

Lodolo, E. & Pérez, L. F. An abandoned rift in the southwestern part of the South Scotia Ridge (Antarctica): Implications for the genesis of the Bransfield Strait. Tectonics 34, 2451–2464 (2015).

Nilsson, A., Holme, R., Korte, M., Suttie, N. & Hill, M. Reconstructing Holocene geomagnetic field variation: new methods, models and implications. Geophys. J. Int. 198, 229–248 (2014).

Chauvin, A., Gillot, P.-Y. & Bonhommet, N. Paleointensity of the Earth’s magnetic field recorded by two Late Quaternary volcanic sequences at the Island of La Réunion (Indian Ocean). J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 96, 1981–2006 (1991).

Anderson, S. W., Krinsley, D. H. & Fink, J. H. Criteria for recognition of constructional silicic lava flow surfaces. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 19, 531–541 (1994).

Hilton, D. R., Hammerschmidt, K., Loock, G. & Friedrichsen, H. Helium and argon isotope systematics of the central Lau Basin and Valu Fa Ridge: Evidence of crust/mantle interactions in a back-arc basin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 2819–2841 (1993).

Sumino, H., Dobrzhinetskaya, L. F., Burgess, R. & Kagi, H. Deep-mantle-derived noble gases in metamorphic diamonds from the Kokchetav massif Kazakhstan. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 439–449 (2011).

Dunai, T. J. Scaling factors for production rates of in situ produced cosmogenic nuclides: a critical reevaluation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 176, 157–169 (2000).

Blard, P.-H. & Farley, K. A. The influence of radiogenic 4He on cosmogenic 3He determinations in volcanic olivine and pyroxene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 276, 20–29 (2008).

Sumino, H., Nagao, K. & Notsu, K. Highly Sensitive and Precise Measurement of Helium Isotopes Using a Mass Spectrometer with Double Collector System. J. Mass Spectrom. Soc. Jpn. 49, 61–68 (2001).

Álvarez-Valero, A. M. et al. Noble gas variation during partial crustal melting and magma ascent processes. Chem. Geol. 588, 120635 (2022).

Matsuda, J. et al. The 3He/4He ratio of the new internal He Standard of Japan (HESJ). Geochem. J. 36, 191–195 (2002).

Lal, D. Cosmic ray labeling of erosion surfaces: in situ nuclide production. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 104, 424–439 (1991).

Martos, Y. M., Catalán, M., Galindo-Zaldívar, J., Maldonado, A. & Bohoyo, F. Insights about the structure and evolution of the Scotia Arc from a new magnetic data compilation. Global Planet. Change 123, 239–248 (2014).

Torrecillas, C., Berrocoso, M. & García-García, A. The Multidisciplinary Scientific Information Support System (SIMAC) for Deception Island. In Antarctica: Contributions to Global Earth Sciences (ed. Fütterer, D. K.) (Springer, 2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the military staff of the Spanish Antarctic Base “Gabriel de Castilla” for their constant help and logistic support, and the crew of the scientific vessel “BIO-Hespérides” without which this research would not have been possible. We dedicate this paper to Drs. Andrés Barbosa and “Manen” Catalán for their special elegance -Life and Science-. The manuscript has greatly benefited from detailed and constructive comments by two anonymous reviewers, and the editor Michael Dee. We are also grateful to P.-H. Blard for his important comments on an earlier version. This research was supported by the Spanish Government (MICINN projects) RECALDEC (CTM2009-05919-E/ANT), PEVOLDEC (CTM2011-13578-E/ANT), POSVOLDEC (CTM2016-79617-P) (AEI/FEDER, UE), VOLGASDEC (PGC2018-095693-B-I00) (AEI/FEDER, UE), HYDROCAL (PID2020-114876GB-I00), and EruptING (PID2021-127189OB-I00) (MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033). We also appreciate the assistance of the project: Playas Ricas en Olivino de Tenerife: Efectos sobre el ciclo del carbono e influencia sobre los organismos marinos (2022CLISA30) Caja Canarias Fundación y Fundación “La Caixa”. A.M.A-V also thanks the JSPS invitation fellowship (S18113) at the University of Tokyo, and the USAL-2019 project (Programa Propio—mod. 1B). This research is part of POLARCSIC activities. A.P.-S. is grateful for his PhD grant “Programa Propio III Universidad de Salamanca cofounded by Banco de Santander” and his joint 2022 COMNAP-IAATO Antarctic Fellowship. A. C acknowledges the grant RYC2021‐033270‐I funded by MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and by the EU “Next Generation EU/PRTR". We also thank the Polar Rock Repository (http:// resea rch. bpcrc. osu. edu/ rr/) for loaning the rock sample PRR-10298 collected by C.H. Shultz in 1970. This sample on loan is based on services provided by the Polar Rock Repository with support from the National Science Foundation, under Cooperative Agreements OPP-1643713 and OPP-2137467 (https:// doi. org/ 10. 7289/ V5RF5 S18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G., G.K., A.P.-S., A.C., A.M.A.-V. performed fieldwork on Deception Island. A.M.A.-V. manually separated the olivine phenocrysts. H.S. and A.M.A.-V. designed the manuscript’s idea, analysed the noble gases and made the calculations. L.A. utilized the data to develop her master’s thesis. A.G. and A.P.-S. built Figs. 1 and 2. H.S., A.C., R.B., L.A., A.P.-S. and A.M.A.-V. designed Table 1. L.A., A.P.-S., A.G., H.A., M.A., M.B., J.B., M.G.-A., G.I., G.K. and J.A.L.-R. contributed with key discussions on the geology of the Antarctic area and the isotopic ratios to outline the manuscript. A.M.A.-V. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Álvarez-Valero, A.M., Sumino, H., Burgess, R. et al. Cosmogenic helium signatures at Deception Island volcano (Antarctica): geochronological implications for its eruptive history. Sci Rep 15, 24683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03925-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03925-5