Abstract

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by impaired diastolic function closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. This study aims to identify hub genes related to HFpEF and mitochondrial function, and to elucidate their potential mechanisms to offer new insights for therapeutic strategies. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the GSE194151 dataset were intersected with mitochondrial-related genes (MRGs) to identify candidate genes. Machine learning techniques, including LASSO regression, SVM-RFE, and Boruta analysis, were used to select hub genes. A ceRNA regulatory network was constructed. Single-cell RNA sequencing data from GSE236585 were utilized to identify key cell types and analyze cell-cell interactions. Hub gene expression was validated using GSE236584, GSE180065, and RT-qPCR. We identified 336 DEGs and 1136 MRGs, with 9 intersecting candidate genes. Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1 emerged as hub genes through machine learning techniques. Vwa8 localized to the cytoplasm, while Mthfd2 and Decr1 were nuclear. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that Decr1 is involved in the citric acid cycle and Parkinson’s disease pathways, Mthfd2 in cardiac muscle contraction and ascorbate and aldolate metabolism, and Vwa8 in primary bile acid biosynthesis and pentose and gluconate interconversion pathways. Single-cell analysis highlighted fibroblasts as key cells with elevated hub gene expression in HFpEF. The ceRNA network included 2 mRNAs, 4 miRNAs, and 10 lncRNAs. Additionally, TF-mRNA analysis identified FOXL1 as a common regulator of Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1. Hub genes showed significant diagnostic potential with high AUC values in both training and validation datasets. RT-qPCR confirmed their upregulation in HFpEF samples. This study identifies Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1 as pivotal hub genes in HFpEF, elucidating their molecular mechanisms and potential as diagnostic biomarkers. These findings provide a valuable basis for developing targeted therapies for HFpEF, underscoring the importance of integrative bioinformatics and experimental approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) significantly contributes to the worldwide prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. Characterized by cardiac structural or functional abnormalities, HF results in reduced cardiac output or elevated intra-cardiac pressure, under both resting and stress conditions1. HF is categorized into three subtypes based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): HFrEF (LVEF < 40%), HFmrEF (LVEF 40–49%), and HFpEF (LVEF ≥ 50%)2. In the HFpEF subtype, patients frequently display myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammation, all of which contribute to diastolic dysfunction3. Considering that nearly half of the patients with heart failure symptoms are diagnosed with HFpEF4, prompt identification of this subtype is essential for effective clinical management and treatment planning.

HFpEF is frequently categorized as a clinical syndrome rather than a discrete disease entity5. Comorbid conditions such as severe obesity, pulmonary diseases, and myocardial ischemia, which are prevalent among HFpEF patients, may mimic heart failure symptoms6. Furthermore, the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria has historically constrained research into HFpEF. I Only recently have comprehensive diagnostic criteria been established by the European Society of Cardiology7. Nonetheless, the management of HFpEF continues to pose significant challenges8. HFpEF and HFrEF exhibit comparable clinical manifestations and adverse prognostic indicators; however, therapeutic strategies effective for HFrEF do not exhibit the same efficacy in HFpEF9, indicating potential disparities in their molecular mechanisms. Consequently, delineating the pathophysiological underpinnings of HFpEF and pinpointing novel therapeutic targets is critically important.

Notably, research has identified a robust association between mitochondrial dysfunction and HFpEF. The heart’s contractile function depends on an adequate supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), of which approximately 70% is produced via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation10. Therefore, mitochondrial stability is imperative for the heart’s energy supply. In individuals with HFpEF, mitochondrial dysfunction is characterized by reduced ATP synthesis, resulting in an inadequate energy supply to myocardial cells, potentially a pivotal factor in the development or aggravation of HFpEF symptoms11. Thus, mitochondrial dysfunction could be integral to the pathophysiology of HFpEF. While the link between mitochondrial dysfunction and HFpEF is established, the precise effects of mitochondrial impairment on cardiac function in HFpEF, alongside the intricacies of the underlying mechanisms, are yet to be fully understood, necessitating additional investigation.

Present therapeutic approaches for heart failure predominantly utilize pharmacological agents, including beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Nonetheless, these pharmacological interventions fail to address mitochondrial dysfunction, a critical pathogenic factor in HF. Recent studies indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction is pivotal in the pathogenesis of heart failure, particularly in HFpEF. In light of this, our study employed bioinformatics analysis to pinpoint pivotal mitochondria-related genes (MRGs) implicated in HFpEF. Subsequently, we confirmed the diagnostic relevance of these genes for HFpEF and evaluated their predictive value for the risk of HFpEF development using a Nomogram model. Moreover, we examined the association between these pivotal genes and the immune microenvironment, and delved into their prospective molecular regulatory mechanisms through single-cell sequencing data. Our findings offer novel insights into the molecular underpinnings, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies for HFpEF.

Materials and methods

Data extraction

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) was used to download the training set (GSE194151) and testing sets (GSE236584 and GSE180065). In GSE194151, the control group contained heart tissues from 7 female and 8 male mice (control diet), and the HFpEF group contained heart tissues from 7 female and 8 male mice (high fat diet + L-NAME)12. In GSE236584, the heart tissues of 6 HFpEF mice and 6 control mice were obtained. Additionally, the heart tissues from 10 mice (high fat diet + L-NAME) and 5 mice (control diet) were gained in GSE180065. The single cell data set GSE236585 was also downloaded from GEO database, containing the heart tissues of 3 HFpEF mice and 3 control mice. The 1136 mitochondria-related genes (MRGs; Supplementary Table 1) were downloaded from MitoCarta3.0 database (https://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta).

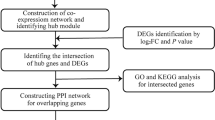

Identification and enrichment analysis of candidate genes

To screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HFpEF and control group, the “DESeq2” package (version 1.34.0)13 was used to proceed differential expression analysis for the expression matrix of GSE194151 (P < 0.05, |log2 FoldChange| > 0.5). Using “ggplot2” (version 3.4.1)14, the DEGs were visualized by volcano map. Subsequently, 1136 human MRGs were homologously transformed to obtain 1118 mice MRGs (Supplementary Table 2). By intersecting DEGs and mice MRGs, the candidate genes were then screened. The result was visualized by “VennDiagram” (version 1.7.1)15. To investigate the function and pathways associated with candidate genes, the Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)16,17,18 analyses were executed using “clusterProfiler” package (version 4.2.2)19 (P < 0.05). The KEGG pathway database is copyrighted by Kanehisa laboratories and we do require formal permission from them to publish this material commercially under an Open Access license. Lastly, the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed was constructed using the STRING database (http://www/string-db.org/) with the interaction type restricted to ‘physical interactions’ (confidence score > 0.4). The result was visualized by “Cytoscape” (version 3.8.2)20.

Characterization and evaluation of hub genes

In order to further screen the hub genes, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis (3-fold cross validation) was firstly performed using “glmnet” (version 4.1-4)21, which screened out the feature genes whose regression coefficients were not penalized to zero. Next, the candidate genes were analyzed by support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) analysis using “caret” (version 6.0–93)22, which iteratively removed the features with the lowest scores by ranking the feature scores. Further, the Boruta algorithm iteratively removed genes with low correlation to identify the final characterized genes, which was performed by the “Boruta” package (version 8.0.0)23 with default parameters. By intersecting potential hub gene obtained from LASSO, SVM-RFE and Boruta analyses, the final hub genes were obtained. The result was visualized by “VennDiagram” (version 1.7.1)15.

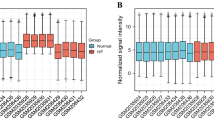

In GSE194151, the expression of hub genes were displayed by rank sum test (P < 0.05). The result was drawn by box plots. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrated the diagnostic value of hub genes for HFpEF. The expression of hub genes and ROC curves were verified in GSE236584 and GSE180065.

Localization prediction of hub genes

In this study, we first queried the FASTA sequences of the hub genes through the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Then, the FASTA sequences were inserted into mRNALocater (http://bio-bigdata.cn/mRNALocater) to calculate the prediction scores of each hub gene in five subcellular localizations, and the final localization was based on the highest prediction score. The prediction scores were shown by stacked histograms. The distribution of hub genes on chromosomes was analyzed using “OmicCircos” (version 1.36.0)24.

Construction and evaluation of nomogram

Based on the hub genes expression, the samples of HFpEF in GSE194151 were used as ending events, and nomogram was constructed by “rms” (version 6.5-1)25 to predict the risk of HFpEF occurrence. Calibration curves clearly illustrated the predictive capability of the nomogram. The Hosmer-Lemeshow (HL) test was employed to evaluate the nomogram model’s goodness of fit by analyzing discrepancies between predicted and observed values. An HL test P-value exceeding 0.05 suggested no significant discrepancy between predicted and actual values, indicating a good model fit. Conversely, a P-value below 0.05 indicated significant differences, implying poor model fit. Additionally, the mean absolute error (MAE) was used to evaluate the discrepancy between predicted and actual values. Generally, an MAE below 0.1 indicated minor discrepancies between actual and predicted risk, reflecting high predictive accuracy of the nomogram model. Moreover, the ROC curves evaluated the prediction ability of nomogram.

Function enrichment of hub genes

In GSE194151, the Spearman correlation coefficients for each key gene and all genes separately in the HFpEF samples were calculated and ranked according to the correlation coefficients from largest to smallest. Based on the genes set (c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt) from the MSigDB database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/), the GSEA was enforced (FDR < 0.05). The top 10 signaling pathways (sorted by enrichment score) from the enrichment results of each hub gene were visualized using the R package “enrichplot”.

Transcription factors (TFs) prediction and CeRNA regulatory network construction

This study employed the miRNet database (https://www.mirnet.ca/) to predict TFs for hub genes, facilitating the construction of a hub gene-TF network. The ceRNA network was constructed using the miRNet, NetworkAnalyst, miRcode2, and StarBase databases. The methodology proceeded as follows: Initially, the miRNet and NetworkAnalyst (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/NetworkAnalyst/) databases were utilized to predict miRNAs targeting hub genes, identifying 146 common miRNAs via intersection analysis. Subsequently, the miRNet, miRcode2 (http://www.mircode.org/index.php) and StarBase (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) databases were employed to predict competing lncRNAs for these 146 miRNAs, leading to the identification of 10 common lncRNAs through intersection analysis. Finally, miRNA-hub gene pairs and lncRNA-miRNA pairs were integrated to establish a hub gene-centric ceRNA network. Both the hub gene-TF network and the ceRNA network were visualized with the R package “Cytoscape” (version 3.8.2)20.

Single cell data analysis

In GSE236585, the single-cell sequencing data was filtered through data quality control by CreateSeuratObject function of “Seurat” (version 4.1.0)26 (nFeature_RNA < 300, nFeature_RNA > 5,000, nCount_RNA > 20,000, percent.mt ≥ 5%). The data was normalized by NormalizeData and FindVariableFeatures, and the 2000 highly variable genes were identified. The result was visualized by LabelPoints function. Based on the highly variable genes, the RunPCA function was used to execute the principal component analysis (PCA). the top 20 principal components were selected by JackStrawPlot function (P < 0.05). And the gravel plot was drawn to identify available dimensions using EIbowPlot function. Using the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions, the unsupervised clustering was proceeded to confirm the cell clusters according to the above principal components (resolution = 0.4), and the nonlinear dimensionality reduction was assessed by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Using “SingleR” (version 1.83.1)27, the cell clusters were annotated. The proportion of different cell clusters between HFpEF and control samples was shown by histograms. Further, the marker genes of different cell types were screened by FindAllMarkers function and the Wilcoxon test was used to examine the differential marker genes of each cell cluster (|log2 FC| > 1, adj. P < 0.05). Then, bubble plot was used to show the expression of the top 5 marker genes in different cell types. Moreover, the UMAP plot displayed the expression of hub genes, and the bubble chart showed the expression of hub genes in different cell cluster. The cell with the highest expression in HFpEF group was called key cells. By “clusterProfiler” (version 4.2.2)19, the GO function enrichment analysis of marker gene in the key cell was implemented (adj. P < 0.05). The result was shown by “ggplot2” (version 3.4.1)14. Additionally, the cell communication between cell types was analyzed by “cellchat” (version 1.5.0)28. Finally, UMAP dimensionality reduction was performed on key cells, and their subtypes were analyzed by proposed time series using “Monocle” (version 2.22.0)29. Meanwhile, the expression trajectories of hub genes in key cells were analyzed.

Construction of a murine HFpEF model through metabolic and hypertensive insults

C57BL/6 male mice, each weighing approximately 20 g and aged 8 weeks, were sourced from Hu’nan Silaikejingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd, China. The protocols for animal care and experimental procedures were compliant with relevant international and national guidelines and were accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). All experiments involving animals conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health and were approved and reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital in Xi’an, Shaanxi, China(project licence number: 2023 K-S151). The studies were in compliance with all ethical regulations. The animals were allocated into two distinct groups, subjected to a dual challenge consisting of a high-fat diet (HFD) providing 60% of energy from fat and administration of Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) at a concentration of 0.5 g l − 1 in their drinking water, or maintained on a standard diet for a duration of 15 weeks30,31. This dual intervention paradigm was designed to induce a state analogous to human HFpEF, characterized by metabolic derangements, including obesity and metabolic syndrome, and mechanical strain from hypertension due to the inhibition of constitutive NO synthases. At the conclusion of the 15-week treatment period, all experimental mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and left ventricular samples were collected from mice across the experimental cohorts and preserved at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

Real-time quantitative-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The TRIzol method was used to extract the total RNA in five pairs mouse left ventricle samples (5 HFpEF samples and 5 control samples). The cDNA was synthesized by SweScript First Strand cDNA synthesis kit. The SYBR Green qPCR Mix were used to perform the RT-qPCR reaction. The relative expression of hub genes was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt formula, using GAPDH as the internal control. Finally, GraphPad Prism 5 was used for data visualization and analysis. The primers of hub genes were shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Bioinformatics analyses were conducted using the R programming language. Statistical significance was denoted as follows: * for P < 0.05, ** for P < 0.01, *** for P < 0.001, and **** for P < 0.0001.

Results

Candidate genes screening and functional enrichment analysis

Within the training set, 336 DEGs (P < 0.05, |log2 FC| > 0.5) were identified between the HFpEF group (n = 6) and the control group (n = 6) using DESeq2 (version 1.34.0). Of these, 143 genes were up-regulated, while 193 were down-regulated (Fig. 1A). Following intersection analysis (Fig. 1B), Acot2, Decr1, Ech1, Hao2, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 were identified as up-regulated MRGs, whereas Bcl2 l11, Mtfr2, and Pld6 were found to be down-regulated. These nine genes were designated as candidate genes for further analysis. The GO analysis showed candidate genes were related with fatty acid oxidation, phosphate ion binding and peroxisome etc. (Fig. 1C). And the KEGG analysis revealed candidate genes were enriched in peroxisome, fatty acid elongation and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids etc. (Fig. 1D). Moreover, the PPI network revealed interactions among Decr1, Ech1, Acot2, and Hao2, characterized by physical interactions with a confidence score of > 0.4 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Screening candidate genes based on GSE194151 dataset. (A) The volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in GSE194151 dataset. (B) Overlapping genes between MRGs and GSE194151 DEGs. (C) The Circular graphs of GO enrichment analysis. (D) KEGG analysis of the candidate genes. Various significant pathways and associated genes are represented with different colors.

Vwa8, Mthfd2 and Decr1 were identified as hub genes

In this study, three machine learning algorithms—LASSO, SVM-RFE, and Boruta—were employed to identify key features from nine candidate genes. LASSO identified five significant genes: Vwa8, Mthfd2, Decr1, Bcl2 l11, and Mtfr2 (Fig. 2A). SVM-RFE selected four genes: Decr1, Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Ech1 (Fig. 2B). Boruta identified eight genes: Vwa8, Mthfd2, Decr1, Ech1, Bcl2 l11, Mtfr2, Acot2, and Hao2 (Fig. 2C). Intersection analysis revealed that Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1 were consistently identified as common feature genes by all three algorithms (Fig. 2D).

Identification of hub genes and assessment of their diagnostic capabilities. (A) Results of the Lasso multivariate model. (B) The curve of change in the predicted true value of each gene in SVM-RFE algorithm. (C) Boruta method identified candidate genes in GSE194151 dataset. (D) Overlap between Lasso-feature factors, SVM-RFE-feature factors, and Boruta-feature factors. (E) ROC curves of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 in the GSE194151 dataset. (F) ROC curves of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 in the GSE236584 and GSE180065 datasets.

Subsequently, the discriminatory power of these three genes to differentiate HFpEF samples from controls was assessed using ROC analysis on the training set. The results indicated ROC-AUC values of 1.0 for Decr1 and Vwa8, and 0.991 for Mthfd2 (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the discriminatory ability of these genes was consistently validated in the validation datasets GSE236584 and GSE180065, yielding AUC values exceeding 0.95 (Fig. 2F). These findings suggest that these genes hold potential as diagnostic biomarkers and can be defined as hub genes for subsequent analyses.

Moreover, the subcellular localization of the three hub genes was predicted using the mRNALocater database. The results demonstrated that Vwa8 is localized in the cytoplasm, whereas Mthfd2 and Decr1 are localized in the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 2 A). Furthermore, the chromosomal distribution of the hub genes is as follows: Mthfd2 is located on chromosome 2, Decr1 on chromosome 8, and Vwa8 on chromosome 13 (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Construction of a nomogram based on hub genes

A nomogram was developed using three hub genes to predict the risk of HFpEF (Fig. 3A). Calibration curve analysis revealed a HL test P-value of 0.63 and MAE = 0.001 (Fig. 3B), indicating no significant difference and small error between the model predictions and actual outcomes. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis demonstrated an AUC of 1 for the nomogram (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that the nomogram based on hub genes exhibits high accuracy and practical utility in predicting HFpEF risk.

Potential biological pathways revealed by GSEA analysis of hub genes

This study involved a comprehensive GSEA of three hub genes: Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8, aimed at identifying their associated biological pathways. Figure 4 illustrated the top ten KEGG pathways enriched for Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8. Subsequent analysis revealed significant enrichment of each hub gene in various functional pathways. Decr1 was associated with enrichment in 54 KEGG pathways, including metabolic processes such as the citrate cycle and fatty acid metabolism, signal transduction pathways like MAPK and calcium signaling, and disease-related pathways concerning Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (Supplementary Table 3). Mthfd2 showed enrichment in 81 pathways, covering cardiac functions such as cardiac muscle contraction and dilated cardiomyopathy, metabolic pathways like glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolism, as well as cell cycle processes (Supplementary Table 4). Vwa8 was enriched across 59 pathways, predominantly associated with metabolic activities such as fatty acid degradation and amino acid metabolism, immune responses like RIG-I-like receptor signaling and cell adhesion molecules, and neurological disorders including Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (Supplementary Table 5).

TF-mRNA and CeRNA networks based on hub genes

The TF-hub gene network, as anticipated via the miRNet database, comprised 17 nodes: 3 hub genes and 14 TFs, connected by 19 edges (Fig. 5A). Specifically, Vwa8 engaged with 8 TFs, Decr1 with 6, and Mthfd2 with 5. Notably, FOXL1 interacted with all three hub genes, whereas FOXC1 impacted Vwa8 and Mthfd2, and SREBF1 affected Vwa8 and Decr1.

The ceRNA network encompassed 16 nodes, which included the hub genes Mthfd2 and Decr1, 4 miRNAs, and 10 lncRNAs, establishing 27 edges in total (Fig. 5B). In particular, lncRNA NEAT1 and XIST modulated Decr1 and Mthfd2 expression through competitive binding with hsa-mir-107. Six lncRNAs modulated Decr1 expression via competitive binding with hsa-mir-146b-5p. Furthermore, hsa-mir-761 and hsa-mir-3619-5p were competitively bound by seven lncRNAs (EPB41L4 A-AS1, HCG17, LINC00242, PVT1, NEAT1, LINC00324, and XIST) to modulate Mthfd2 expression.

The marker genes of 8 cell clusters were screened

A total of 51,975 cells were remained by data quality control (Supplementary Fig. 3 A). After data normalization, 2000 high variability genes were identified (Supplementary Fig. 3B). The data was dimensional reduced by PCA and the top 20 principal components were finally selected (Supplementary Fig. 3 C). Subsequently, 20 cell subtypes were identified (Fig. 6A). In the process of cell cluster annotation, we identified eight distinct cell types: B cells, Endothelial cells, Fibroblasts, Granulocytes, Macrophages, Monocytes, NK cells, and T cells (Fig. 6B). The relative proportions of these eight cell clusters were found to be comparable between the HFpEF and control cohorts, with Fibroblasts being the most prevalent (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Within these eight defined cellular clusters, we identified a total of 4,793 uniquely differentially expressed marker genes (Supplementary Fig. 3E). Figure 6C presented the expression profiles of the five most prominent marker genes across these eight cell types.

The identification of cell clusters based on scRNA seq data. (A) The umap algorithm was applied to the top 20 PCs for dimensionality reduction, and 20 cell clusters were successfully classified. (B) Umap of eight cell types in GSE236585. (C) The dot plot of the top 5 differentially expressed marker gene expression of subgroups.

Cluster 7and cluster 12 in fibroblasts were most differentiated in state5

The UMAP plot showed the high expression of hub genes (Fig. 7A). Fibroblasts had higher expression in HFpEF group, and the cell amount of Fibroblasts was higher (Fig. 7B and C). Thus, Fibroblasts was the key cell in this study. The marker gene of Fibroblasts were enriched in extracellular matrix organization, collagen − containing extracellular matrix and extracellular matrix structural constituent (Fig. 7D). The cell communication result displayed there were more ligand-receptor pairs between Macrophages and Monocytes, and the strongest communication relationship was between Granulocytes and NK cells (Supplementary Fig. 4 A). Moreover, Macrophages have the highest number of ligand-receptor pairs (Supplementary Fig. 4B and 4 C).

Identification and functional enrichment analysis of key cell clusters-fibroblasts. (A) The umap plots of the all-cell types-based hub genes expression. (B) Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 had high expression levels in fibroblasts. (C) Number of cells in different cell types. (D) GO analysis of marker genes in fibroblast clusters.

By UMAP dimensionality reduction, Fibroblasts was divided into 15 cell subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 5). The cluster7 and cluster12 of Fibroblasts were highly differentiated in state5 (Fig. 8A). Further, the expression of Mthfd2 and Decr1 at different stages of Fibroblasts showed a trend of inverted “U” shape. And the expression of Vwa8 at different stages of Fibroblasts was constant (Fig. 8B).

Analysis of fibroblast cell trajectories and pseudo-temporal gene expression patterns, with a focus on the expression trends of hub genes. (A) Cell trajectory and pseudo-time analysis for the identified hub cell types. (B) Expression trends of the hub genes in different developmental stages of fibroblasts.

Validation result of hub genes expression

In the training dataset GSE194151, we extracted the expression profiles of three hub genes. Figure 9A illustrated that Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1 expression levels were markedly elevated in the HFpEF group relative to controls (P < 0.0001 for all). The notable upregulation of these genes in the HFpEF versus control group was corroborated in independent validation datasets GSE236584 (Fig. 9B) and GSE236584 (Fig. 9C), with both datasets showing statistical significance (P < 0.01). Additionally, in the established HFpEF mouse model, RT-qPCR experiments confirmed significant elevations in Vwa8, Mthfd2, and Decr1 expression within the HFpEF cohort compared to controls (P < 0.05 for all, Fig. 9D).

Expression analysis of the hub gene. A. Expression pattern of hub gene between HFpEF group and control group in training set GSE194151.Expression levels of hub gene in validation sets GSE236584 (B) and GSE180065 (C). D. PCR results of the expression level of hub genes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. Control.

Discussion

HFpEF represents a widespread and multifaceted cardiac condition, the etiology and pathogenesis of which remain incompletely elucidated, impeding the advancement of targeted diagnostics and therapies. Mitochondria are crucial for energy metabolism within cardiac cells, with their dysfunction intimately linked to the pathogenesis of HFpEF. Consequently, a thorough investigation into the expression profiles of mitochondrial genes in HFpEF is paramount for deciphering the molecular underpinnings of this condition.

In this investigation, bioinformatics techniques were utilized to pinpoint MRGs such as 2,4-Dienoyl-CoA Reductase 1 (Decr1), Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (Mthfd2), and Von Willebrand Factor A Domain Containing 8 (Vwa8), which exhibit diagnostic potential. Although this study does not construct clinical diagnostic models, the efficiency of machine learning in biomarker screening suggests its potential in future translational research, complementing recent predictive studies based on clinical data32,33,34,35,36. PCR analysis revealed a marked upregulation of these gene expressions in the HFpEF model using C57BL/6 mice, corroborating findings from publicly available datasets. These observations substantiate the pivotal involvement of mitochondrial function in the pathogenesis of HFpEF.

Decr1, a pivotal gene encoding a protein integral to fatty acid β-oxidation, plays a crucial role in lipid metabolism within tumor cells, as evidenced by numerous studies36,37,38,39. Nonetheless, the implications of Decr1 in HF remain insufficiently explored40,41,42. Guan et al. (PMID: 32802835) reported a widespread reduction in Decr1 expression among HF patients, a finding not influenced by the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which implies a possible association between Decr1 and HF pathogenesis. In contrast, our investigation revealed a marked elevation in Decr1 expression within the HFpEF mouse model, diverging from Guan et al.‘s observations and indicating disparate Decr1 functions across HF subtypes. It is imperative to acknowledge that there are substantial disparities between this research and that conducted by Guan et al. in various critical dimensions. The first notable difference pertains to the HF subtype under investigation. Our study concentrated on the HFpEF mouse model, whereas Guan et al. examined cardiac tissues from patients with surgically-managed HF, potentially involving surgical stress responses that can affect gene expression. Secondly, this analysis did not account for the influence of T2DM on Decr1 expression, in contrast to Guan et al.‘s inclusion of T2DM patients in their cohort. Furthermore, interspecies variations must not be disregarded. Despite employing homologous conversion techniques for candidate gene identification, there remain intrinsic regulatory discrepancies in gene expression between humans and mice. Consequently, while this research documents an upregulation of Decr1 in the HFpEF mouse model, further validation in human subjects is required, considering HF subtypes, metabolic conditions, and gene regulatory interspecies divergence.

Mthfd2 is a critical enzyme in mitochondrial folate one-carbon metabolism and is instrumental in the metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells43,44,45,46,47. Although the role of Mthfd2 in cardiovascular diseases is not well-defined, emerging research indicates a connection between mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction and coronary artery disease, hinting at Mthfd2’s possible influence48,49,50. Moreover, research by Mo et al.51 demonstrated that Mthfd2 inhibition can trigger ferroptosis in ovarian cancer cells, characterized by the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced ATP production, and inhibited glycolysis. These alterations are intimately linked to the development of HFpEF, indicating that Mthfd2 might play a comparable role in its regulation52,53,54,55. However, additional mechanistic investigations are required to substantiate this hypothesis.

Vwa8 encodes a protein of 1905 amino acids, with suggested ATPase activity indicating a possible role in cellular energy metabolism56, although its precise function is yet to be elucidated. Tissue distribution analyses reveal that Vwa8 is ubiquitously expressed in multiple mouse organs such as the liver, kidney, heart, pancreas, and skeletal muscle, with splice variants Vwa8a and Vwa8b identified57. This study observed a marked increase in Vwa8 expression within the cardiac tissues of HFpEF mouse models. Contrarily, Z Huang et al.58 reported elevated Circ-Vwa8 levels in myocardial tissues of CHF patients, with a concurrent decrease in linear Vwa8 RNA compared to controls. They inferred that these findings pertain to human samples; however, the absence of explicit information on control sample sources introduces ambiguity in interpreting their results and comparing them to ours. Furthermore, the observed discrepancies might be ascribed to factors such as sample origin (human vs. animal models), disease variants (CHF vs. HFpEF), and specimen processing and analysis techniques (Western Blot vs. PCR). Specifically, in disease conditions, RNA and protein levels may diverge due to the complexities of post-transcriptional and translational regulation leading to disparate responses. Thus, a comprehensive comparison of our findings with those of Z Huang et al. necessitates consideration of all these variables. Despite divergent outcomes, both studies collectively highlight a significant research avenue, indicating distinct roles of Vwa8 and its circular RNA across various HF subtypes. Moreover, research into Vwa8’s role in heart failure remains limited, with the study by Moulun Luo et al.59 offering insightful clues. Their findings revealed that depletion of Vwa8 in mouse liver cells causes mitochondrial abnormalities and triggers an increase in ROS through NOX4 activation, which upregulates HNF4a expression. This cascade could potentially exacerbate oxidative stress at the cellular level, culminating in heightened ROS generation. While our results appear to contradict the depletion scenario reported previously, the complexity of cellular stress responses in disease states suggests that Vwa8 may participate in various compensatory and regulatory processes across different contexts. In HFpEF, Vwa8 upregulation could be a cardiac cellular response to sustained pressure or injury, aimed at preserving or restoring mitochondrial function to satisfy energy demands or mitigate oxidative stress. This compensatory increase may serve to suppress excessive ROS generation or to maintain cardiac cellular homeostasis. Alternatively, Vwa8 upregulation may paradoxically enhance ROS production, aligning with Moulun Luo et al.‘s findings and indicating a comparable compensatory mechanism in the heart under chronic disease conditions. Additionally, Vwa8 may fulfill distinct biological roles across various tissues or engage in different molecular pathways depending on the disease stage. Therefore, despite the apparent contradiction between Vwa8 upregulation in HFpEF and its depletion in Moulun Luo et al.‘s study, Vwa8’s involvement in ROS regulation and cardiac protection in HFpEF cannot be excluded. In summary, we propose that Vwa8 upregulation may represent a compensatory cardiac response to chronic pathological conditions, potentially involving molecular mechanisms akin to those described by Moulun Luo et al.59. Given the nascent understanding of Vwa8’s role in HF, our hypothesis opens avenues for future research to elucidate Vwa8’s precise role, especially its potential in ROS regulation and mitochondrial function in HF.

This study’s single-gene GSEA analysis identified enrichment in critical KEGG pathways—specifically, “OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION,” “CARDIAC MUSCLE CONTRACTION,” and “FATTY ACID METABOLISM”—among three MRGs: Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8. This insight offers a fresh perspective for investigating the molecular functions of these genes in the pathogenesis of cardiac abnormalities in HF patients. Prior research has demonstrated a marked decrease in oxidative phosphorylation activity within the cardiac mitochondria of individuals with HF60. The association of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 with the oxidative phosphorylation pathway intimates a potential regulatory role, possibly reflecting metabolic dysregulation in HF. Considering the heart’s substantial energy requirements for continuous electrophysiological and mechanical functions, such as contraction and relaxation61,62, the observed enrichment of the cardiac muscle contraction pathway aligns with expectations. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms underlying Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8’s regulation of cardiac contraction and relaxation warrant further investigation. Meanwhile, multiple studies have elucidated the intimate link between alterations in fatty acid metabolism and the onset of cardiac diseases62,63,64,65. The detected enrichment of the fatty acid metabolism pathway in this study may signify the involvement of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 in this process, potentially impacting cardiac function. Nonetheless, a comprehensive elucidation of the molecular mechanisms necessitates additional in-depth research and validation. In conclusion, this study’s findings align with extant literature, offering novel insights into the molecular underpinnings of cardiac diseases. Specifically, the prominence of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 within pivotal energy metabolism pathways hints at potential metabolic dysregulation in HF, suggesting targets for prospective research and clinical intervention development.

The analysis of the TF-mRNA regulatory network in this study demonstrates that FOXL1 concurrently regulates Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8. FOXL1 is a member of the Forkhead box (Fox) family of proteins, encompassing more than 100 human members characterized by a conserved 100-amino acid DNA-binding domain66. Recent studies have primarily concentrated on FOXL1’s role in a spectrum of physiological and pathological processes across multiple cancer types, such as non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer67,68,69,70. Conversely, the investigation of FOXL1 within the cardiovascular domain remains scant. Nonetheless, current evidence indicates that the FOXL1-FHL5 interaction is crucial for vascular remodeling71, and FOXL1 is recognized as a pivotal transcription factor in atherosclerosis72. These investigations imply the potential significance of FOXL1 in cardiovascular disorders; however, its exact function in disease pathogenesis is not yet fully elucidated. Moreover, the regulatory nexus between FOXL1 and genes Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 remains to be clarified, underscoring the imperative for additional research to delineate their interplay and its possible influence on disease advancement.

Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network analysis identified nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) and X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) as crucial modulators, engaging with hsa-mir-107 and consequently altering Decr1 and Mthfd2 expression. NEAT1, an abundant and unspliced polyadenylated non-coding transcript, is ubiquitously present in various tissues72. Discovered in 2007, NEAT1 has been implicated in an array of physiological and pathological processes, such as carcinogenesis, neurodegenerative disorders, and viral infections73,74,75. In the context of cardiovascular diseases, NEAT1 modulates miR-370-3p, which affects STAT3 expression and contributes to atherosclerosis progression76. Furthermore, NEAT1 mitigates ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis77, and modulates inflammatory responses to reduce complications in ischemic stroke78. These findings underscore NEAT1’s potential as a therapeutic target, offering promising avenues for future research and clinical intervention.

XIST, a long non-coding RNA, is critically involved in maintaining gene dosage balance by specifically inactivating one of the X chromosomes in females79,80. Emerging research indicates that XIST contributes to tumorigenesis and progression by functioning as a molecular sponge81,82,83. Within the realm of cardiovascular pathology, XIST is notably upregulated in individuals with chronic heart failure, influencing myocardial cell functionality84. XIST modulates myocardial infarction via a ceRNA mechanism85, governs myocardial cell apoptosis86,87, and attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injuries88,89,90. This implies that in-depth investigation into XIST’s roles and mechanisms in cardiovascular disorders could pave the way for innovative therapeutic approaches, especially for individuals suffering from CHF.

MiR-107 is reportedly downregulated in CHF, where it competes for binding sites91. Associations between miR-107 and a spectrum of cardiovascular diseases have been established, encompassing metabolic and cardiac functions92, angiogenesis93, and hypoxia94. Research indicates that miR-107 mediates gene expression regulation via the PI3 K-AKT and MAPK signaling pathways95,96. Furthermore, the XIST-miR-107 axis constitutes a crucial component of the ceRNA network implicated in HF97. Taken together, these findings underscore the intimate link between miR-107 and the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases.

The sequestering function of lncRNA NEAT1 for miR-107 in neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases is well-established73,98,99,100. Additionally, Bin Huang and colleagues have corroborated the regulatory influence of the lncRNA XIST-miR-107 axis in Alzheimer’s disease101. Single-gene GSEA analysis of Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 demonstrated substantial involvement in the “PARKINSONS DISEASE,” “ALZHEIMERS DISEASE,” and “HUNTINGTONS DISEASE”. These results align with the conclusions of other studies on the involvement of lncRNAs NEAT1 and XIST in neurodegenerative disorders, implying that the NEAT1-miR-107 and XIST-miR-107 networks could be pivotal in disease mechanisms.

Single-cell sequencing analysis in this study identified fibroblasts as a pivotal cell population in HFpEF, crucial for elucidating the cellular intricacies of HF. Prior research indicates that the activation and differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts are central to the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis, a key mechanism in HF development102. The transdifferentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts is crucial for the excessive buildup and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM)103,104. Fibroblast responsiveness to TGF-β signaling triggers their conversion to myofibroblasts, hastening fibrosis105,106. Moreover, myofibroblasts modify the cardiac ECM’s composition and structure through the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), which affects myocardial compliance, contractility, and electrical conduction, contributing to HF progression103,107. This study’s single-gene GSEA analysis of three diagnostic markers demonstrated notable enrichment in the “ECM RECEPTOR INTERACTION” pathway, aligning with ECM’s established role in cardiac pathology and underscoring ECM’s significance in cardiac fibroblast function and HF progression. Notably, the study by Yuhua Zhang et al.108 offers valuable insights into the phenotypic traits of cardiac fibroblasts in HFpEF patients. They observed that HFpEF patients, also suffering from hypertension, displayed an enlarged cross-sectional area of myocardial cells and a marked increase in collagen content, suggesting a link between cardiac fibrosis and augmented cardiac stiffness—a correlation not prominent in hypertensive patients without HF. Additionally, the study revealed elevated collagen I synthesis and a notable reduction in MT1-MMP levels in the fibroblasts of these patients, indicative of ECM remodeling alterations throughout the disease course. These findings augment our study’s results and imply that shifts in cardiac fibroblast phenotypes could be instrumental in the pathogenesis of heart failure, especially HFpEF.

Decr1, distinguished as a crucial gene in this study, appears to play a pivotal role in the metabolism and function of cardiac fibroblasts. Prior studies109 have demonstrated that elevated WTAP levels stimulate cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration, implicating a significant function in diabetic cardiac fibrosis. WTAP operates by augmenting m6 A methylation of the androgen receptor (AR) and facilitating its YTHDF2-mediated degradation, a process in which the interaction between AR and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidase Decr1 is vital. AR overexpression impedes Decr1-mediated mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, consequently inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and migration. Conversely, AR inhibition may activate Decr1, potentially leading to improved fibroblast function. These findings suggest that heightened WTAP and YTHDF2 levels, accompanied by AR downregulation, correlate with diabetic cardiomyopathy, potentially enhancing fibroblast proliferation and migration via Decr1 activation and its associated mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Thus, within the HFpEF context, Decr1, as a regulator of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in cardiac fibroblasts, might affect their metabolic state and function, contributing to the cardiac fibrotic process. Continued investigation into the specific roles of Decr1 in fibroblasts will further clarify its involvement in HFpEF pathogenesis. Regarding Mthfd2, despite limited research in cardiovascular disease, studies in other fibrotic conditions underscore its significance. For instance, in pulmonary fibroblasts, TGF-β induces Mthfd2 expression to facilitate collagen synthesis, with Mthfd2 inhibitors shown to mitigate pulmonary fibrosis110. Consequently, it may be posited that in HFpEF, Mthfd2 could foster collagen synthesis in fibroblasts via analogous mechanisms, thus contributing to cardiac fibrosis. Thus, Mthfd2 also emerges as a potential regulator of fibroblast function in the context of HFpEF. Regrettably, current research has yet to elucidate the relationship between Vwa8 and fibroblasts.

This research advances our understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving pathological changes in HF. However, recognizing the limitations of this research is crucial. The principal limitation stems from its reliance on a mouse model of HFpEF, absent direct data from HF patients. Clinical sample validation is imperative for translating these findings into human disease biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Variations between animal models and human pathology could introduce biases, constraining the experimental results’ relevance to human diseases.

Moreover, while bioinformatics and single-cell sequencing have offered profound insights into candidate genes and cellular populations, identifying Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8 as diagnostic markers for HFpEF and highlighting cardiac fibroblasts’ significance, these results predominantly derive from transcriptomic data. Considering the intricate post-transcriptional and post-translational regulatory mechanisms, future studies should integrate multi-omics data, including proteomics and metabolomics, to thoroughly validate these genes’ functions and investigate their regulatory mechanisms.

An additional limitation includes the partial validation of subcellular localization and chromosome distribution for Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8; the study does not fully ascertain their functional significance, potentially affecting a comprehensive understanding of these genes’ roles in HF.

Furthermore, despite the construction of TF-key gene and ceRNA regulatory networks, their foundation on predictive and correlative analyses necessitates direct experimental validation. Future research must empirically substantiate these regulatory associations using RNA interference, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, and immunoprecipitation, in both in vitro and in vivo settings, to determine their exact roles in HFpEF pathogenesis.

Additionally, while this study sheds light on the role of cardiac fibroblasts in HFpEF, HF is characterized by intricate interplays among diverse cell types and molecular pathways. Subsequent research ought to encompass additional cardiac cell types like cardiomyocytes and vascular endothelial cells, and examine their interrelations for an extensive understanding of HF pathogenesis.

Lastly, although the study centers on the link between mitochondrial function and HF, it is pertinent to acknowledge that mitochondrial dysfunction represents only one facet of HF’s pathophysiology. HF development is influenced by an interplay of genetic and environmental factors, with complex interactions at molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. Consequently, future research should employ systems biology approaches to investigate the comprehensive pathological mechanisms of HF within a broader biological framework.

Conclusions

Combining bioinformatics and single-cell sequencing, this study offers detailed insights into the molecular underpinnings of pathological alterations in HF. It has successfully pinpointed critical mitochondrial-associated genes, including Decr1, Mthfd2, and Vwa8. Preliminary evidence from this research confirms the pivotal role of cardiac fibroblasts in HFpEF, illuminating the intricate cellular dynamics of HF. Despite its limitations, the study offers fresh perspectives on the molecular mechanisms of heart failure and identifies potential targets for future therapies.

Subsequent studies should validate these genes in clinical specimens and elucidate HF’s molecular regulatory networks by integrating multi-omics data, including proteomics and metabolomics, alongside functional assays. Additionally, research should broaden its scope to encompass various cardiac cell types and their interactions, aiming to construct an exhaustive map of the global pathological landscape of HF, thus laying a robust scientific groundwork for the precision diagnosis and treatment of HF.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HFpEF:

-

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- MRGs:

-

Mitochondrial related genes

- DEGs:

-

Differential expressed genes

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- SVM-RFE:

-

Support vector machine-recursive feature elimination

- HL:

-

Hosmer-Lemeshow

- TFs:

-

Transcription factors

- UMAP:

-

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

- RT-qPCR:

-

Real-time quantitative-polymerase chain reaction

- Decr1:

-

2,4-Dienoyl-CoA Reductase 1

- Mthfd2:

-

Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2

- Vwa8:

-

Von Willebrand Factor A Domain Containing 8

References

Li, P. et al. Similarities and differences between HFmrEF and HFpEF. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 678614 (2021).

Ponikowski, P. et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2129–2200 (2016).

Simmonds, S. J., Cuijpers, I., Heymans, S. & Jones, E. Cellular and molecular differences between HFpEF and HFrEF: A step ahead in an improved pathological Understanding. Cells 9, 242 (2020).

Sanhueza-Olivares, F. et al. A potential role of autophagy-mediated vascular senescence in the pathophysiology of HFpEF. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1057349 (2022).

Gladden, J. D., Linke, W. A. & Redfield, M. M. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Pflugers Arch. 466, 1037–1053 (2014).

Ho, J. E. et al. Predicting heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: the international collaboration on heart failure subtypes. Circ. Heart Fail. 9 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003116 (2016).

Pieske, B. et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the heart failure association (HFA) of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 391–412 (2020).

Butler, J. et al. Developing therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: current state and future directions. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 97–112 (2014).

Dunlay, S. M., Roger, V. L. & Redfield, M. M. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 591–602 (2017).

Taegtmeyer, H., Wilson, C. R., Razeghi, P. & Sharma, S. Metabolic energetics and genetics in the heart. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1047, 208–218 (2005).

Krueger, K. J. et al. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and D-ribose in HFpEF: a brief narrative review. Ann. Transl Med. 9, 1504 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Sex differences in heart mitochondria regulate diastolic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3850 (2022).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Nandy, A., Basu, A. & Ghosh, A. Robust inference for skewed data in health sciences. J. Appl. Stat. 49, 2093–2123 (2022).

Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 12, 35 (2011).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (Camb). 2, 100141 (2021).

Smoot, M. E., Ono, K., Ruscheinski, J., Wang, P. L. & Ideker, T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics 27, 431–432 (2011).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Qian, Y. et al. A clinical and laboratory-based nomogram for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-diabetic adults: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 11, 2349–2359 (2022).

Kebede Kassaw, A., Yimer, A., Abey, W., Molla, T. L. & Zemariam, A. B. The application of machine learning approaches to determine the predictors of anemia among under five children in Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 13, 22919 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. OmicCircos: A Simple-to-Use R package for the circular visualization of multidimensional omics data. Cancer Inf. 13, 13–20 (2014).

Sachs, M. C. & plotROC: A tool for plotting ROC curves. J. Stat. Softw. 79, 2 (2017). [pii].

Hao, Y. et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587e29 (2021).

Aran, D. et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20, 163–172 (2019).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using cellchat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

Ni, L., Yang, H., Wu, X., Zhou, K. & Wang, S. The expression and prognostic value of Disulfidptosis progress in lung adenocarcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 15, 7741–7759 (2023).

Schiattarella, G. G. et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature 568, 351–356 (2019).

Gou, Q., Zhao, Q., Dong, M., Liang, L. & You, H. Diagnostic potential of energy metabolism-related genes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1296547 (2023).

Zheng, B. et al. Prediction of 90 day readmission in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction by interpretable machine learning. ESC Heart Fail. 11, 4267–4276 (2024).

Ward, M. et al. Ensemble machine learning model identifies patients with HFpEF from matrix-related plasma biomarkers. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 322, H798–H805 (2022).

Jawadi, Z. et al. Predicting in-hospital mortality among patients admitted with a diagnosis of heart failure: a machine learning approach. ESC Heart Fail. 11, 2490–2498 (2024).

Avvisato, R., Forzano, I., Varzideh, F., Mone, P. & Santulli, G. A machine learning model identifies a functional connectome signature that predicts blood pressure levels: imaging insights from a large population of 35 882 patients. Cardiovasc. Res. 119, 1458–1460 (2023).

Guo, S. et al. Reduced 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase 1 is served as an unfavorable biomarker and is related to immune infiltration in cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49, 2475–2486 (2023).

Ursini-Siegel, J. et al. Elevated expression of DecR1 impairs ErbB2/Neu-induced mammary tumor development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6361–6371 (2007).

Nassar, Z. D. et al. Human DECR1 is an androgen-repressed survival factor that regulates PUFA oxidation to protect prostate tumor cells from ferroptosis. Elife 9, e54166 (2020).

Blomme, A. et al. 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase regulates lipid homeostasis in treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 11, 2508 (2020).

Peng, C., Zhang, Y., Lang, X. & Zhang, Y. Role of mitochondrial metabolic disorder and immune infiltration in diabetic cardiomyopathy: new insights from bioinformatics analysis. J. Transl Med. 21, 66 (2023).

Sanchez-Ruderisch, H., Queirós, A. M., Fliegner, D., Eschen, C. & Kararigas, G. Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex-specific regulation of cardiac MicroRNAs targeting mitochondrial proteins in pressure overload. Biol. Sex. Differ. 10, 8 (2019).

Wei, X. H. et al. Quantitative proteomics reveal that metabolic improvement contributes to the cardioprotective effect of T(89) on Isoproterenol-Induced cardiac injury. Front. Physiol. 12, 653349 (2021).

Christensen, K. E. & Mackenzie, R. E. Mitochondrial methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, Methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase, and formyltetrahydrofolate synthetases. Vitam. Horm. 79, 393–410 (2008).

Liu, F. et al. Increased MTHFD2 expression is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 35, 8685–8690 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 overexpression is associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 48, 953–960 (2016).

Lin, H. et al. MTHFD2 overexpression predicts poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma and is associated with cell proliferation and Vimentin-Modulated migration and invasion. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 51, 991–1000 (2018).

Ju, H. Q. et al. Modulation of redox homeostasis by Inhibition of MTHFD2 in colorectal cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 111, 584–596 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. Association of maternal folate intake and offspring MTHFD1 and MTHFD2 genes with congenital heart disease. Nutrients 15, 3502 (2023).

Khatami, M., Ratki, F. M., Tajfar, S. & Akrami, F. Relationship of the MTHFD1 (rs2236225), eNOS (rs1799983), CBS (rs2850144) and ACE (rs4343) gene polymorphisms in a population of Iranian pediatric patients with congenital heart defects. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 33, 442–448 (2017).

Song, X. et al. Association of MTHFD1 gene polymorphisms and maternal smoking with risk of congenital heart disease: a hospital-based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 22, 88 (2022).

Mo, X., Liu, Q., Liang, K. & Song, Y. Interference with MTHFD2 induces ferroptosis in ovarian cancer cells through ERK signaling to suppress tumor malignant progression. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 56(3), 333–345 (2024).

Mongirdienė, A., Skrodenis, L., Varoneckaitė, L., Mierkytė, G. & Gerulis, J. Reactive oxygen species induced pathways in heart failure pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies. Biomedicines 10, 602 (2022).

Xiong, Y. et al. Inhibition of ferroptosis reverses heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in mice. J. Transl Med. 22, 199 (2024).

Sun, Q. et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is the major source of cardiac adenosine triphosphate production in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc. Res. 120, 360–371 (2024).

Fillmore, N. et al. Uncoupling of Glycolysis from glucose oxidation accompanies the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Mol. Med. 24, 3 (2018).

Umair, M. et al. Mutated VWA8 is associated with developmental delay, microcephaly, and scoliosis and plays a novel role in early development and skeletal morphogenesis in zebrafish. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 736960 (2021).

Luo, M. et al. Characterization of the novel protein KIAA0564 (Von Willebrand Domain-containing protein 8). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 487, 545–551 (2017).

Huang, Z. et al. [High expression of Circ-PALLD in heart failure is transcriptionally regulated by the transcription factor GATA4]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 43, 1371–1378 (2023).

Luo, M. et al. Deletion of the mitochondrial protein VWA8 induces oxidative stress and an HNF4α compensatory response in hepatocytes. Biochemistry 58, 4983–4996 (2019).

Rosca, M. G. et al. Cardiac mitochondria in heart failure: decrease in respirasomes and oxidative phosphorylation. Cardiovasc. Res. 80, 30–39 (2008).

Rosca, M. G. & Hoppel, C. L. Mitochondria in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 88, 40–50 (2010).

Ashrafian, H. & Frenneaux, M. P. Metabolic modulation in heart failure: the coming of age. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 21, 5–7 (2007).

Hu, T. et al. Short-chain fatty acid metabolism and multiple effects on cardiovascular diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 81, 101706 (2022).

Yamamoto, T. & Sano, M. Deranged myocardial fatty acid metabolism in heart failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 996 (2022).

Arumugam, S., Sreedhar, R., Thandavarayan, R. A., Karuppagounder, V. & Watanabe, K. Targeting fatty acid metabolism in heart failure: is it a suitable therapeutic approach. Drug Discov Today. 21, 1003–1008 (2016).

Hannenhalli, S. & Kaestner, K. H. The evolution of Fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 233–240 (2009).

Luo, D. B. et al. LncRNA TRERNA1 promotes malignant progression of NSCLC through targeting FOXL1. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 1233–1242 (2020).

Zhong, J., Wang, H., Yu, J., Zhang, J. & Wang, H. Overexpression of forkhead box L1 (FOXL1) inhibits the proliferation and invasion of breast Cancer cells. Oncol. Res. 25, 959–965 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. FOXL1, a novel candidate tumor suppressor, inhibits tumor aggressiveness and predicts outcome in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 5416–5425 (2013).

Perreault, N., Sackett, S. D., Katz, J. P., Furth, E. E. & Kaestner, K. H. Foxl1 is a mesenchymal modifier of min in carcinogenesis of stomach and colon. Genes Dev. 19, 311–315 (2005).

Wong, D. et al. FHL5 controls vascular Disease-Associated gene programs in smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 132, 1144–1161 (2023).

Hridoy, H. M. et al. In Silico based analysis to explore genetic linkage between atherosclerosis and its potential risk factors. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 36, 101574 (2023).

Li, K. & Wang, Z. LncRNA NEAT1: key player in neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 86, 101878 (2023).

Klec, C., Prinz, F. & Pichler, M. Involvement of the long noncoding RNA NEAT1 in carcinogenesis. Mol. Oncol. 13, 46–60 (2019).

Prinz, F., Kapeller, A., Pichler, M. & Klec, C. The implications of the long Non-Coding RNA NEAT1 in Non-Cancerous diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 627 (2019).

Liu, A., Zhang, Y., Xun, S. & Sun, M. Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes atherosclerosis via regulating the enriched abundant transcript 1/miR-370-3p/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/flavin-containing monooxygenase-3 axis. Bioengineered 13, 1541–1553 (2022).

Zhou, Z. W., Ren, X., Zheng, L. J., Li, A. P. & Zhou, W. S. LncRNA NEAT1 ameliorate ischemic stroke via promoting Mfn2 expression through binding to Nova and activates Sirt3. Metab. Brain Dis. 37, 653–664 (2022).

Zhou, Z. W., Ren, X., Zhou, W. S., Li, A. P. & Zheng, L. J. LncRNA NEAT1 alleviates ischemic stroke via transcriptional Inhibition of NLRP3 mediated by the miR–10b–5p/BCL6 axis. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars). 82, 12–21 (2022).

Giorgetti, L. et al. Structural organization of the inactive X chromosome in the mouse. Nature 535, 575–579 (2016).

Brown, C. J. et al. F. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 349, 38–44 (1991).

Ghafouri-Fard, S., Dashti, S., Farsi, M., Taheri, M. & Mousavinejad, S. A. X-Inactive-Specific transcript: review of its functions in the carcinogenesis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 690522 (2021).

Chen, Y. K. & Yen, Y. The ambivalent role of LncRNA Xist in carcinogenesis. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep. 15, 314–323 (2019).

Yang, Z., Jiang, X., Jiang, X. & Zhao, H. X-inactive-specific transcript: A long noncoding RNA with complex roles in human cancers. Gene 679, 28–35 (2018).

Sun, Z. L., Chen, M. H., Guo, Y. N. & Liu, Z. Q. LncRNA XIST is elevated in patients with chronic heart failure and has a regulatory role in cardiomyocyte function. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 35, 677–682 (2021).

Zhou, T., Qin, G., Yang, L., Xiang, D. & Li, S. LncRNA XIST regulates myocardial infarction by targeting miR-130a-3p. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 8659–8667 (2019).

Cai, C. L., Jin, L., Lang, X. L. & Li, B. L. Long noncoding RNA XIST regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting miR-873-5p/MCL1 axis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 12878–12886 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Silence of LncRNA XIST represses myocardial cell apoptosis in rats with acute myocardial infarction through regulating miR-449. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 8566–8572 (2019).

Bao, J. et al. LncRNA JPX targets SERCA2a to mitigate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by binding to EZH2. Exp. Cell. Res. 427, 113572 (2023).

Bai, Q., Li, Y., Song, K., Huang, J. & Qin, L. Knockdown of XIST up-regulates 263294miR-340-5p to relieve myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting Cyclin D1. ESC Heart Fail. 9, 1050–1060 (2022).

Wang, X., Li, X. L. & Qin, L. J. The LncRNA XIST/miR-150-5p/c-Fos axis regulates sepsis-induced myocardial injury via TXNIP-modulated pyroptosis. Lab. Invest. 101, 1118–1129 (2021).

Voellenkle, C. et al. MicroRNA signatures in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronic heart failure patients. Physiol. Genomics. 42, 420–426 (2010).

Rech, M. et al. AntagomiR-103 and – 107 treatment affects cardiac function and metabolism. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 14, 424–437 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. MicroRNA-107 contributes to post-stroke angiogenesis by targeting Dicer-1. Sci. Rep. 5, 13316 (2015).

Kulshreshtha, R. et al. A MicroRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1859–1867 (2007).

Fan, Q., Wu, M., Li, C. & Li, J. MiR-107 aggravates Oxygen-Glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R)-Induced injury through inactivating PI3K-AKT signalling pathway by targeting FGF9/FGF12 in PC12 cells. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 31, 106295 (2022).

Niu, C. C. et al. Upregulation of miR-107 expression following hyperbaric oxygen treatment suppresses HMGB1/RAGE signaling in degenerated human nucleus pulposus cells. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 42 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. Establishment and analysis of the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network based on competitive endogenous RNA identifies functional genes in heart failure. Math. Biosci. Eng. 18, 4011–4026 (2021).

Ke, S. et al. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 aggravates Aβ-Induced neuronal damage by targeting miR-107 in Alzheimer’s disease. Yonsei Med. J. 60, 640–650 (2019).

Dong, L., Zheng, Y. & Luo, X. LncRNA NEAT1 promotes autophagy of neurons in mice by impairing miR-107-5p. Bioengineered 13, 12261–12274 (2022).

Sabaie, H. et al. Molecular insight into the therapeutic potential of long Non-coding RNA-Associated competing endogenous RNA axes in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic scoping review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 742242 (2021).

Huang, B., Ou, G. Y. & Zhang, N. Identification of key regulatory molecules in the early development stage of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28, e18151 (2024).

Yao, Y. et al. ADAMTS16 activates latent TGF-β, accentuating fibrosis and dysfunction of the pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 956–969 (2020).

Fan, D., Takawale, A., Lee, J. & Kassiri, Z. Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 5, 15 (2012).

Zhou, H. T., Yu, X. F. & Zhou, G. M. Diosgenin inhibits angiotensin II-induced extracellular matrix remodeling in cardiac fibroblasts through regulating the TGF–β1/Smad3 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 15, 2823–2828 (2017).

Dobaczewski, M., Chen, W. & Frangogiannis, N. G. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 51, 600–606 (2011).

Okayama, K. et al. Hepatocyte growth factor reduces cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting endothelial-mesenchymal transition. Hypertension 59, 958–965 (2012).

Frangogiannis, N. G. The extracellular matrix in ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. Circ. Res. 125, 117–146 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Phenotypic characterization of primary cardiac fibroblasts from patients with HFpEF. PLoS One. 17, e0262479 (2022).

Song, K. et al. WTAP boosts lipid oxidation and induces diabetic cardiac fibrosis by enhancing AR methylation. iScience 26, 107931 (2023).

Meliton, A. Y. et al. Mitochondrial One-Carbon Metabolism is Required for TGF-β-Induced Glycine Synthesis and Collagen Protein Production. bioRxiv 11.07.566074 [pii] (2023). (2023).

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi (2023-JC-YB-762).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All applicable international and national guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China (No. 2023 K-S151).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, H., Fan, X., Diao, J. et al. Integrative transcriptomic and single-cell analysis reveals mitochondrial-related gene biomarkers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Sci Rep 15, 44241 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03926-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03926-4