Abstract

Transradial access (TRA) in neurointervention has gained popularity due to fewer procedural complications and reduced recovery time compared to transfemoral access (TFA). This study aimed to assess the feasibility and safety of using 0.018-inch guidewire (018’’GW)-supported distal access catheters (DAC) in establishing transradial neurointerventional access, in comparison to the Ballast long sheath. We performed a retrospective review of a prospective database of transradial neurointervention with Ballast long sheath-supported DACs or 018’’GW-supported DACs. Patient demographics, baseline clinical characteristics, and detailed procedural information were recorded. The success rate of TRA neurointervention using 018’’GW-supported DACs was comparable to that of the Ballast long sheath protocol (100% vs. 96.3%, p = 0.19). Both protocols achieved comparable placement heights of DACs and outcomes for aneurysm and symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (sICAS) treatment. Moreover, the 018’’GW-supported DACs significantly decreased 6-month radial artery occlusion (RAO) rates (5.88% vs. 18.18%, p = 0.045) without any major vascular or neurological complications. This study highlights the feasibility and safety of 018’’GW-supported DACs in TRA neurointervention, offering a viable alternative with reduced complications and enhanced distal stability in comparison with the Ballast long sheath.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing advancement and popularization of neurointerventional techniques in recent years have led to a growing preference for transradial access (TRA). This popularity is largely due to TRA’s ability to minimize access-related complications, reduce post-procedural bed rest, and enhance both patient comfort and satisfaction1,2,3.

Due to challenges such as large loop formation angles, tortuosity and complex anatomy (such as types of the arch), the optimal transradial access establishment approach and effective neurointerventional devices for TRA remain unclear. The long sheath-supported distal access catheters (DAC) are commonly used to establish transradial neurointervention access in China. However, research indicated that using larger sheaths may cause endothelial damage, increasing the risk of radial artery occlusion (RAO) and radial artery spasm (RAS)4,5. As a common and specific complication of TRA, RAO can compromise the radial artery’s future usability for repeat TRA, fistula preparation, coronary artery bypass grafting, or reconstructive surgery.

The 0.018-inch guidewire (018’’GW), a common support device used in peripheral vascular interventions, is highly flexible and provides internal support without damaging the endothelium6. The purpose of this study is to assess the feasibility, safety, and incidence of RAO with the 018’’GW-supported DACs in TRA neurointervention, compared to the 088’’ Ballast long sheath.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective review of a prospective database, comparing two groups: consecutive patients undergoing TRA neurointervention using Ballast long sheath-supported DACs between August 2023 and October 2023 (long-sheath group), and consecutive patients undergoing TRA neurointervention using 018’’GW-supported DACs between January and March 2024 (018’’GW group). The period from November to December 2023 marked the transition from the Ballast long sheath-supported DACs technique to the 018’’GW-supported DACs technique. Inclusion criteria included first-time TRA, radial artery diameter ≥ 2.5 mm, modified Allen test (-), and age ≥ 18 years. Exclusion criteria included: endovascular procedure contraindications (such as coagulation dysfunction, severe infection, and malignant disease), refusal to undergo assessment of radial artery patency and acute ischemic stroke. Data collection encompassed patient demographics, baseline clinical characteristics, and procedural details. Outcome variables included the feasibility and safety of access establishment, along with specific access-related complications (such as RAO, RAS, forearm hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, etc.). Radial artery patency was assessed using Doppler ultrasonography at 24 h postoperatively, at discharge, and 6 months after the procedure. A 6-month radial artery ultrasound follow-up was performed on patients diagnosed with RAO at 24 h postoperatively or at discharge. Since some RAO cases may undergo spontaneous recanalization, the final RAO data will be based on the 6-month ultrasound assessment. The tortuosity index (TI) was calculated for the ipsilateral segments (common carotid artery (CCA) and extracranial internal carotid artery (EICA)) that were traversed by both access establishment protocols. TI = 1 - (straight line distance/distance along the centerline). The calculation methods and definitions were described in detail in previous studies7. Aortic arch type was classified according to previously published classification as: bovine, types 1, 2 and 38. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (2021-Q094-02). The requirement for written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Transradial neurointerventional access establishment procedure

All transradial artery (TRA) neurointerventional procedures were conducted by a single experienced physician, with over two years of proficiency in Ballast long sheath support techniques and a portfolio exceeding 200 cases utilizing the 018’’GW supported-DACs techniques. Under general anesthesia, the radial artery was successfully punctured using a modified Seldinger technique, followed by the placement of a 6 French (6 F) short radial sheath. Spasmolytic drugs (200 µg of nitroglycerin and 2.5 mg of verapamil diluted in normal saline) were directly injected through the sheath. Intravenous heparin (70 unit/kg) is administered to maintain an activated clotting time of between 250 and 350 s. Subsequently, a 018’’GW or a long sheath was used to support DACs to establish TRA. Technical success was defined as radial artery puncture, short sheath insertion, and completion of the neurointerventional procedure using either the 018’’GW or the long sheath-supported DACs, without conversion to TFA.

The long sheath-supported DACs

After exchanging the 6 F radial short sheath (Cordis, Switzerland), a Simmons-2-shaped catheter (anterior circulation) or a vertebral angiography catheter (posterior circulation) inside the 6 F Ballast long sheath (Balt, USA) helped reach the target vessel and position the Ballast selectively into the diseased vessel. Therefore, the Ballast supports the advancement of DAC under the guidance of a 035’’GW using the coaxial technique.

018’’ guidewire-supported DACs

Using the coaxial technique, the DAC is selectively positioned in the target vessel under the 035’’GW guidance and through the 6 F short sheath. Initially, it is placed alongside a Simmons 2-shaped (anterior circulation) or a vertebral angiographic catheter (posterior circulation); thereafter, an 018’ GW is inserted inside the DAC. Thus, the 018’ GW will internally support the DAC’s progression to the proximal segment of the lesion under the 035’ guidance.

Based on the patient’s clinical condition, the appropriate DAC (SMIROA, CED MEDICAL, China; Zenith, China; Soft, TONBRIDGE, China; Easyport, YIJIE, China; Navien, EV3, USA; Wellthrough, INT MEDICAL, China) was chosen for further interventions.

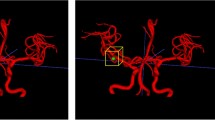

The two access establishment protocols are demonstrated in Fig. 1. The vivid schematic illustrations can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1 online.

A radial artery compression device was used to compress the puncture site for 6–8 h following the intervention until no blood oozed from the puncture site.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data. Mean (SD) descriptions and unpaired t-tests were used for normally distributed continuous variables; Median (IQR) descriptions and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Frequency descriptions and χ2 test or Fisher’s test were used for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University Institutional Review Board (2021-Q094-02). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University Institutional Review Board waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Results

Over the study period, 126 eligible patients underwent transradial neurointervention at our facility, split into two groups: 70 using the 018’’GW and 54 using the Ballast long sheath. Comparative analysis showed no significant differences between the groups regarding sex (p = 0.59), age (p = 0.89), Body Mass index (p = 0.92), arterial hypertension (p = 0.47), current smoking (p = 0.44), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.30), alcohol abuse (p > 0.99), dyslipidemia (p = 0.47), antithrombotic medication (p = 0.61), calcium channel blockers (p > 0.99), aortic arch type (p = 0.96) and TI (p = 0.07 for CCA and p = 0.5 for EICA).

DSA illustration of the long sheath-supported distal access catheters (DAC) and 018’’ guidewire (018’’GW)-supported DACs to establish transradial neurointerventional access. (A) The long sheath (white arrow) was positioned in the left common carotid artery, providing support for the DAC (red arrow) to establish transradial neurointerventional access. (B) The 018’’GW supported the DAC (white arrow) internally at the distal end of the left ICA via radial artery access. (C) The 018’’GW support system (red arrow) was parallel to the interventional system including stent-microcatheter (white arrow) and coil-microcatheter (yellow arrow) inside the DAC. (D) The 018’’GW (white arrow) independently provided support inside the DAC (red arrow), irrespective of the deployment or operation of other interventional devices (yellow arrow) within the same catheter.

In the 018’’GW group, pathologies included: aneurysms (n = 37, 52.86%), symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (sICAS) (n = 31, 44.29%), carotid artery dissection (n = 1, 1.43%) and chronic unruptured arteriovenous malformation/arteriovenous fistula (AVM/AVF) (n = 1, 1.43%). The long-sheath group showed similar pathologies: aneurysms (n = 26, 48.15%), sICAS (n = 24, 44.44%), carotid artery dissection (n = 2, 3.70%), and chronic unruptured AVM/AVF (n = 2, 3.70%). Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in the types of cerebrovascular lesions between the groups (p = 0.16). Patient demographics, baseline clinical characteristics and procedural details are summarized in Table 1.

Feasibility

The 018’’GW-supported DACs in establishing transradial neurointerventional access was feasible

In the 018’’GW group, all 70 procedures (100%) were performed with successful transradial access establishment. In the long-sheath group, the success rate of establishing transradial access was 96.3% (52/54). However, 1 case (1.85%) required conversion to TFA due to long sheath kinking (Fig. 2. A), and 1 case (1.85%) was converted due to repeated dislodgment of the long sheath. The success rate of establishing transradial neurointerventional access with the 018’’GW did not differ from Ballast long sheaths (100% vs. 96.3%, p = 0.19) (Table 1).

For interventions using the 018’’GW, the DAC tip was positioned at or beyond the ICA-C4 segment in 19 (55.88%) cases. In posterior circulation interventions, the tip of DACs supported by the 018’’GW reached or exceeded the VA-V4 segment in 12 (33.33%) cases. The placement height of DACs under the support of the 018’’GW showed no difference compared to the Ballast long sheath group (55.88% vs. 34.04% for ICA-C4 segment and above, p = 0.07; 33.33% vs. 42.86% for VA-V4 segment and above, p = 0.68) (Table 1).

In the comparison of supporting performance at the distal end of the access, the tip of the 018’’GW was able to reach the distal end of the DAC to provide support (30/31, 96.77%), demonstrating intracranial high positioning performance. Due to the tortuosity of the intracranial segment of ICA and VA, in most cases, the Ballast long sheath could only provide support for the DAC in the extracranial segment, resulting in the absence of external support from the long sheath for the distal portion of the DAC. This underscores the 018’’GW’s capability to stabilize the distal end of access during transradial interventions.

In the 018’’GW group, the left TRA was performed in 7 patients (one for amputation of right upper extremity, one for excessive tortuosity of the right radial artery and five for left vertebral artery lesions).

Feasibility of the 018’’GW-supported distal access catheter in transradial neurointervention for intracranial aneurysms

There were no significant statistical differences between the two groups in the number of ruptured aneurysms (24.32% vs 42.31%, p = 0.17), aneurysm location (p = 0.07), or embolization techniques (p = 0.14). Aneurysm embolization outcomes were assessed using the Raymond Roy classification (RRC) (coiling/stent-assisted coiling) and the O’Kelly-Marotta (OKM) grading scale (pipeline) 180 days after the procedure. The effectiveness of transradial aneurysm treatment using 018’’ guidewire-supported DACs was found to be comparable to that of the Ballast long sheath group, with no statistically significant difference in outcomes (p = 0.13 for coiling/stent-assisted coiling and p > 0.99 for pipeline) (Table 2). Two representative cases were illustrated in Fig. 2. B-C.

Feasibility of the 018’’GW -supported distal access catheter in transradial neurointervention for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis

There were no significant statistical differences between the two groups in the stenotic artery (p = 0.70), length of lesion (7.33 ± 1.29 mm vs 7.58 ± 0.97 mm, p = 0.43), or interventional techniques (p>0.99). Pre-treatment stenosis and post-treatment stenosis rates of sICAS in the 018’’GW group were similar to those in the Ballast long sheath group (p = 0.12 for pre-treatment and p = 0.43 for post-treatment) (Table 2).

A. During the procedure of catheterizing the right common carotid artery through right transradial access (TRA), the long sheath kinked (white arrow). We used a goose neck snare kit to retract the kinked sheath via transfemoral access and then withdrew the kinked long sheath via TRA. B. An adult patient underwent a TRA stent-assisted coil embolization for a ruptured, wide basilar aneurysm (yellow arrow) located in the left internal carotid artery (ICA)-C7 segment. The 018’’ guidewire (red arrow) internally supported the distal access catheter (DAC, white arrow), enabling stable access and successful completion of the intervention. C. A pipeline (yellow arrow) was successfully deployed for the treatment of a left bilobed ophthalmic segment-aneurysm via TRA with established by the 018’’ guidewire (red arrow)-supported DAC (white arrow).

Safety

No macrovascular complications or neurologic deficits occurred in the 018’’ guidewire group. However, 1 case (1.85%, p = 0.44) of asymptomatic brachiocephalic artery dissection (Fig. 3. A), and 1 case (1.85%, p = 0.44) of postoperative persistent neurologic deficits occurred following the transradial neurointerventions with the access established by the Ballast long sheath-supported DACs (Table 2).

The 018’’ guidewire-supported DACs in TRA significantly reduced 6-month RAO

Comparative analysis revealed no significant difference in the preoperative radial artery diameter at the puncture site between the groups (2.63 ± 0.08 mm vs 2.66 ± 0.08 mm, p = 0.06). In the 018’’GW group, there was 1 case of RAO at 24 hours postoperatively, 3 cases at discharge, and 1 case at follow-up, with recanalization observed in 1 patient at follow-up who had RAO at discharge. In the Long-sheath group, 4 cases of RAO occurred at 24 hours postoperatively, 6 cases at discharge, and 3 cases at follow-up, with recanalization observed at follow-up in 1 patient with RAO at 24 hours postoperatively and in 2 patients with RAO at discharge. Utilizing an 018’’GW instead of a Ballast long sheath to support the DAC for transradial neurointerventional access markedly decreased the 6-month incidence of RAO (5.71% vs. 18.52%, p = 0.045) (Fig. 3. B-C) (Table 2). All recorded 6-month RAOs were asymptomatic. There was no significant difference in RAS rates between the two groups (0 vs 3.7%, p = 0.19). More critically, a patient in the long-sheath group experienced severe RAS, leading to sheath entrapment and intimal avulsion during retraction (Fig. 3. D).

The safety of the 018’’ guidewire and long sheath in transradial neurointervention access. (A) A follow-up angiography revealed an asymptomatic dissection of the brachiocephalic artery following the withdrawal of a long sheath catheterizing the right internal carotid artery (ICA). (B) An adult patient, presenting severe stenosis in the M3 segment of the right middle cerebral artery, was treated with balloon angioplasty and stent placement through the long sheath support via transradial access (TRA). Ultrasonography 24 h post-procedure detected a right asymptomatic radial artery occlusion (RAO). (C) An adult patient with a ruptured aneurysm in the left ICA-C7 segment received flow diversion therapy. Subsequent angiography 6 months postoperatively indicated RAO. (D) One case of excessive RAS in the long-sheath group resulted long sheath entrapment and intimal avulsion during long sheath retraction. Angiography revealed contrast leakage from the radial artery in several places.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report comparing 018’’GW-supported DAC and the widely used Ballast long sheath-supported DAC in establishing access for transradial neurointervention. We have confirmed the feasibility and safety of 018’’GW-supported DACs in transradial neurointervention, with a technical success rate of 100%, no adverse vascular events, and a reduction in radial access complications (6-month RAO = 5.71%).

In neurointerventional therapy, TRA is increasingly favored due to its shorter required bed rest, reduced and less severe postoperative complications, and enhanced patient privacy9,10. However, the stability of the access is crucial for the success and prognosis of TRA interventions. Owing to the nascent stage of device development for transradial neurointervention, robust strategies of establishing stable radial access are under investigation. For instance, Chen et al. employed various configurations to treat aneurysms with flow diversion via TRA, including a 6 F Envoy guide catheter over a 6 F short transradial introducer sheath, a 088’’ Infinity guide catheter without a sheath, and an intermediate catheter without a guide catheter. Among these interventions, 10 cases (20.41%) required conversion to TFA, primarily due to access instability11. In 2021, Srinivasan et al. detailed their use of DACs alone in posterior circulation interventions, though they did not discuss complications specific of TRA12. Furthermore, the Neuron MAX long sheath, commonly used in TFA, showed disappointing outcomes in TRA, chiefly due to high rates of RAO13. In 2021, Weinberg et al. assessed the efficacy of the Ballast long sheath in 91 transradial neurointerventions, noting a transfemoral conversion rate of 3.3%, comparable to our 3.7%. They reported a similar RAS rate of 3.7%, akin to our findings with the same sheath14. However, they did not observe RAO after adopting Ballast long sheath.

Patency of the radial artery after transradial neurointervention is important for future follow-up and other therapeutic needs15,16. Rashid et al.'s meta-analysis on RAO rates in TRA demonstrated that the incidence of flow reduction was significantly lower when radial artery inner diameter/cannulated sheath outer diameter was ≥ 1.0.17. Our team found in the current study that the success rate of 018’’GW support was comparable to that of Ballast long sheaths without additional adverse events, and notably reduced 6-month RAO incidence. We attribute complications associated with Ballast’s sheaths to their large outer diameter, particularly in sharply angled TRA access. In contrast, the internal support and flexible material of the 018’’GW substantially minimize vascular endothelial damage. In addition, the radial artery long sheath (23 cm-Merit Ideal Sheath or 16 cm-Terumo Glidesheath) has proven effective in mitigating 6-month RAO and RAS18. In addition to the smaller outer diameter of the thin-walled sheath system, another important reason is that, compared to the 6 F sheathless long sheath, the thin-walled sheath prevents friction against the vessel wall during the delivery of interventional devices. With the growing popularity of TRA and the increasing awareness of radial artery protection, specialized TRA devices and techniques are continuously advancing. Studies have shown that radial catheters such as the 079Rist, 081 FUBKI, and 081BMX performed well in transradial neurointervention19,20,21. With flexible support technologies and a variety of radial access devices available, we will continue to make steady progress on the path of transradial neurointervention.

In aneurysm embolization procedures, the intra-aneurysm coil microcatheter tip and the dual-intervention system of the SAC generate significant and continuous tension at the distal end of the access, requiring high performance of the support device. Our preliminary findings suggested that the transradial access, established using the 018’’ guidewire-supported DAC, achieved a success rate comparable to that of the long sheath in aneurysm treatment. However, the 018’’GW demonstrated superior positioning performance compared to the Ballast long sheath proximal support, resulting in fewer tension-related failures and a reduction in intervention time. In sICAS interventions, the unnecessary portion of the long sheath extending outside the body resulted in a loss of the internal interventional material’s length due to placement difficulties. This occasionally led to challenges in balloon and stent exchanges and insufficient balloon lengths. In addition, the external device of the access system supported internally by the 018’’GW was the DAC, which was thinner and softer than the long sheath and caused less damage to the vessel wall.

Several cardiology studies identified extended operation durations and increased radiation exposure as principal barriers to adopting TRA22,23. Compared to the Ballast long sheath, most of the 018’’GWs (96.77%) were able to be easily and quickly delivered to the head of the DACs, although DAC placement heights were similar. Our team found that with the enhanced distal stabilization provided by the 018’’GW, operation durations were significantly reduced and efficiency was significantly improved. The internal and fully supported performance of the 018’’GW was friendly to the specific access requirements. Commonly left TRA entails longer operative times and increased operator discomfort, while all 7 cases of left TRA in our study used an 018’’GW instead of a long sheath. Despite subjective variations, statistical analysis (p = 0.02, Table 1) indicates that the convenience and distal stability provided by the 018’’GW mitigated discomfort and reduced operative times, enhancing operator preference. Evaluating fluoroscopic times for transradial neurointerventions using 018’’ guidewire-supported DACs compared to other TRA protocols will be crucial in our ongoing research. The 018’’GW is also an effective alternative, for situations with strict limitations on the outer diameter of the device or distal support requirements when high positioning, such as distal TRA.

Moreover, the treatment of cerebral aneurysms with flow diversion presents a significant technical challenge in TRA24,25. Due to the rigidity of flow-diverters and the complex curvature of deep vessels, the flow-diverter deployment typically necessitates supplementary support for the intermediate catheter. The 2.7 mm outer diameter of long sheaths currently used in neuroradiology (such as Neuron MAX and Axs Infinity) restricts their utility in TRA applications26. In this study, eleven (11/12, 91.67%) aneurysm embolizations were performed using the 018’’GW-supported DAC for TRA pipeline (Flex) implantations achieved a grade D on the O’KM grading scale. Our success rate of transradial implantation of FD was 100% higher than the 79.6% (39/49) of Chen et al.11. Experience has shown that the 018’’GW’s internal support technology, unlike the 088 triaxial system, adequately provides the necessary distal stability of the access during flow-diverter deployment.

From a health economics perspective, the novel transradial access establishment protocol of 018’’GW-supported DACs could reduce patient surgical costs and access complications, and increase patient preference for TRA by reducing reliance on high-performance long sheaths, as long as it remains safe and feasible27,28.

However, our findings also highlight indispensable applications for use of long sheaths. In endovascular recanalization of patients with acute ischemic stroke, whether via TRA or TFA, thrombus aspiration necessitates the use of long sheaths for external support. Similarly, for procedures like stent-assisted angioplasty and cerebral umbrella delivery at lower anatomical levels, long sheaths are the preferred method for establishing access. Despite these specific uses, 018’’GWs offer a versatile alternative in TRA protocols, allowing operators to pair them with a wide range of catheters without hindering the delivery of interventional devices.

This study had limitations, including a single-center and single-operator design, its small cohort size, retrospective nature, patient heterogeneity, and focus on Chinese patients. Additionally, this study may contain biases in selecting the protocols of transradial neurointerventional access establishment and the choice of procedures. Prior to perfecting the 018’’GW support technique, intervention strategies for deep lesions varied, employing appropriate long sheaths and access modalities. Subsequent the operator chose the 018’’GW-supported DAC in TRA as the preferred option for treating deep lesions within both the anterior and posterior circulations. This study omitted several variables that could provide additional insights into the feasibility and safety of the 018’’GW-supported DACs in TRA, such as specific treatment details for different pathologies, fluoroscopy time, access establishment time, number of attempts, the duration of hemostasis at the puncture site, and long term functionality. Nonetheless, preliminary results from our center validate the supportive performance of the 018’’GW in TRA, affirming its feasibility and safety, and underscoring the need for further research for its broader indications.

Conclusion

This study showed that the technique of establishing transradial neurointerventional access with 018’’GW-supported DACs was feasible and safe, and its role in neurointervention deserved further exploration. This novel access establishment protocol (internal support technology) provides more options and guidance for neurointerventionalists to establish a satisfactory radial access.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, S. H. et al. Transradial versus transfemoral access for anterior circulation mechanical thrombectomy: comparison of technical and clinical outcomes. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 11, 874–878. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014485 (2019).

Lee, J. E., Kan, P. & Commentary Propensity-Adjusted comparative analysis of radial versus femoral access for neurointerventional treatments. Neurosurgery 89, E124–e125. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyab162 (2021).

Snelling, B. M. et al. Transradial access: lessons learned from cardiology. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 10, 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013295 (2018).

Saito, S., Ikei, H., Hosokawa, G. & Tanaka, S. Influence of the ratio between radial artery inner diameter and sheath outer diameter on radial artery flow after transradial coronary intervention. Catheterization Cardiovasc. Interventions: Official J. Soc. Cardiac Angiography Interventions. 46, 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1522-726x(199902)46:2%3C173::Aid-ccd12%3E3.0.Co;2-4 (1999).

Brunet, M. C., Chen, S. H. & Peterson, E. C. Transradial access for neurointerventions: management of access challenges and complications. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 12, 82–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015145 (2020).

Lorenzoni, R., Ferraresi, R., Manzi, M. & Roffi, M. Guidewires for lower extremity artery angioplasty: a review. EuroIntervention: J. EuroPCR Collab. Working Group. Interventional Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 11, 799–807. https://doi.org/10.4244/eijv11i7a164 (2015).

Mokin, M. et al. Semi-automated measurement of vascular tortuosity and its implications for mechanical thrombectomy performance. Neuroradiology 63, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-020-02525-6 (2021).

Madhwal, S. et al. Predictors of difficult carotid stenting as determined by aortic arch angiography. J. Invasive Cardiol. 20, 200–204 (2008).

Restrepo-Orozco, A. et al. Radial access intervention. Neurosurg. Clin. North Am. 33, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2021.11.006 (2022).

Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., Cui, G., Xiong, H. & Wang, D. L. Transradial versus transfemoral access for posterior circulation endovascular intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 234, 108006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2023.108006 (2023).

Chen, S. H. et al. Transradial approach for flow diversion treatment of cerebral aneurysms: a multicenter study. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 11, 796–800. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014620 (2019).

Srinivasan, V. M., Cotton, P. C., Burkhardt, J. K., Johnson, J. N. & Kan, P. Distal Access Catheters for Coaxial Radial Access for Posterior Circulation Interventions. World neurosurgery 149, e1001-e1006, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.01.048

Boeken, T. et al. Prohibitive radial artery occlusion rates following transradial access using a 6-French neuron MAX long sheath for intracranial aneurysm treatment. Clin. Neuroradiol. 32, 1031–1036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-022-01177-8 (2022).

Weinberg, J. H. et al. Early experience with a novel 088 long sheath in transradial neurointerventions. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 202, 106510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106510 (2021).

Bernat, I. et al. Best practices for the prevention of radial artery occlusion after transradial diagnostic angiography and intervention: an international consensus paper. JACC Cardiovasc. Intervent. 12, 2235–2246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.043 (2019).

Aminian, A. et al. Distal versus conventional radial access for coronary angiography and intervention: the DISCO RADIAL trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Intervent. 15, 1191–1201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2022.04.032 (2022).

Rashid, M. et al. Radial artery occlusion after transradial interventions: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Association. 5 https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.115.002686 (2016).

Luther, E. et al. Implementation of a radial long sheath protocol for radial artery spasm reduces access site conversions in neurointerventions. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 13, 547–551. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016564 (2021).

Phillips, T. J. et al. Transradial versus transfemoral access for anterior circulation mechanical thrombectomy: analysis of 375 consecutive cases. Stroke Vascular Neurol. 6, 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2020-000624 (2021).

Rautio, R., Alpay, K., Rahi, M. & Sinisalo, M. A summary of the first 100 neurointerventional procedures performed with the Rist radial access device in a Finnish neurovascular center. Eur. J. Radiol. 158, 110604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110604 (2023).

Marangoni, M. et al. Practical uses of the BENCHMARK™ BMX®81 in the road less travelled: Guide catheter comparison for radial access in neurovascular intervention. Interventional Neuroradiology: J. Peritherapeutic Neuroradiol. Surg. Procedures Relat. Neurosciences. 15910199241261756 https://doi.org/10.1177/15910199241261756 (2024).

Singh, S., Singh, M., Grewal, N. & Khosla, S. The fluoroscopy time, door to balloon time, contrast volume use and prevalence of vascular access site failure with transradial versus transfemoral approach in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Medicine: Including Mol. Interventions. 16, 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2015.08.013 (2015).

Plourde, G. et al. Radiation exposure in relation to the arterial access site used for diagnostic coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (London England). 386, 2192–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00305-0 (2015).

Liu, X., Luo, W., Wang, M., Huang, C. & Bao, K. Feasibility and safety of flow diversion in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms via transradial approach: A Single-Arm Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 13, 892938. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.892938 (2022).

Khandelwal, P. et al. Dual-center study comparing transradial and transfemoral approaches for flow diversion treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Brain Circulation. 7, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/bc.bc_38_20 (2021).

Chivot, C., Bouzerar, R. & Yzet, T. Transitioning to transradial access for cerebral aneurysm embolization. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 40, 1947–1953. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6234 (2019).

Catapano, J. S. et al. Propensity-adjusted cost analysis of radial versus femoral access for neuroendovascular procedures. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 13, 752–754. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016728 (2021).

Lorenzo Górriz, A. et al. Early exploration of the economic impact of transradial access (TRA) versus transfemoral access (TFA) for neurovascular procedures in Spain. J. Med. Econ. 26, 1445–1454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2023.2266956 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. and S.H. contributed to the conception and design of the study; L.B., Y.Z. and J.L. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; L.B. and S.H. contributed to drafting the text or preparing the figures. All authors and relevant patients agreed for publication of the paper in this journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, L., Zhao, Y., Li, J. et al. Feasibility and safety of 0.018-inch guidewire-supported distal access catheters in establishing transradial neurointerventional access. Sci Rep 15, 19009 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03986-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03986-6