Abstract

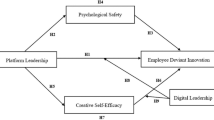

Platform leadership emphasizes shared goals, unlocking potential, and generating positive impacts for both leaders and subordinates. This style greatly influences frontline nurses’ attitudes and behaviors, underscoring the need to study how it stimulates innovation. Using 422 questionnaires from 52 hospitals, internal mechanisms of platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovation were analysed with Mplus 8.0 and HLM 6.08. The study uncovered the following results: Firstly, platform leadership was positively correlated with frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. Secondly, leader–member exchange (LMX) and relational energy served as mediators between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. Thirdly, the error management climate was positively correlated with frontline nurses’ innovative behavior and acted as a moderator in the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. The study’s findings reveal the internal mechanisms of platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior, offering valuable insights for organizational improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Innovative behavior is defined as employees’ capacity to conceive novel ideas and incorporate them into their daily work processes1,2,3. A plethora of factors can exert an influence on this behavior, and leadership styles, in particular, play an especially pivotal role4,5. In the digital era, the enhanced efficiency of information and resource dissemination has catalyzed the implementation of “decentralized” and “leaderless” management paradigms, which have emerged as a prominent trend in organizational transformation6. Specifically, platform leadership underscores the collaborative endeavors between leaders and their subordinates. By engaging in “platform building” and “platform optimization,” it not only improves the quality and level of the platform but also unlocks the potential of both parties, enabling mutual growth7. The platform represents careers, and in contrast to other leadership styles, platform leadership places the interests of both leaders and subordinates at the forefront, facilitating their co-development6,7. For instance, it encourages personalized exchanges among subordinates to enhance role performance8, cultivates their independent personalities to stimulate innovative behavior9, and nurtures workplace gratitude to drive business model innovation10. Although subordinates’ proactive behavior is vital for managing uncertainty, maintaining flexibility, and promoting innovation, leadership style remains a key determinant of innovative behavior11. In healthcare, front-line nurses are core human resources, shouldering significant responsibilities in patient care. Platform leadership, which centers around collaborating with front-line nurses and continuously motivating their potential, yields positive outcomes7. This leadership style is pivotal in promoting the transition to “decentralized” and “leaderless” management within organizations6. It enables organizations to perceive changes in market demand and implement autonomous actions, significantly driving employees’ positive behavior. However, the existing literature on platform leadership is predominantly composed of normative theories, with limited empirical analyses7. A comprehensive understanding of how platform leadership influences subordinates’ proactive behavior and the underlying mechanisms driving innovative behavior remains largely unexplored12. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to actively explore the internal mechanism through which platform leadership affects the innovative behavior of front-line nurses.

Leader–member exchange (LMX) theory delineates the diverse interactions and relationships that leaders forge with distinct subordinates through their cognitive assessments, operating within the limitations of time and resources13. High—quality leader—member exchange relationships have the capacity to satisfy the fundamental psychological requirements of overqualified subordinates, such as the needs for safety, self—esteem, and a sense of belonging. This enables them to develop emotional connections with leaders. Under such circumstances, subordinates are more inclined to exhibit a stronger sense of organizational commitment14. This heightened commitment serves as a driving force for innovative behavior, which in turn improves innovation performance. On the contrary, low—quality leader—member exchanges lead to subordinates receiving less empowerment, trust, and emotional backing15. Consequently, in hospital environments, leader—member exchanges exert a positive influence on the intrinsic motivation and behavioral performance of front—line nurses. They potentially play a crucial part in platform leadership and encourage innovative behavior among these front—line medical professionals.

The emergence of the positive organizational behavior movement has sparked scholars’ interest in workplace energy, with research focusing on cultivating positive emotions, activating work energy, and unleashing employee potential16. According to COR theory, individuals seek to acquire and maintain valuable resources like job control, autonomy, self-efficacy, and self-esteem to cope with work challenges17. Human energy is also considered an important organizational resource18. Research shows that relational energy stems from interpersonal interactions and combines individual energy in group settings19. High levels of relational energy contribute to enhancing individual psychological resources and elevating mental levels. Conversely, a lack of energy can lead to negative emotions and decreased work experiences, such as work fatigue, stress, and work disengagement20,21. Platform leadership emphasizes equal communication between leaders and subordinates and fosters good relationships among leaders and team members through empowerment, care, and other leadership behaviors. As a result, members gain social, interpersonal, and relational energy22. This energy serves as the fundamental driving force behind social interactions and phenomena, instilling group members with confidence, enthusiasm, and motivation to engage in activities that enhance work performance, inspire innovative behavior, and align with their moral standards. Therefore, relational energy may play a crucial role in platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Errors refer to unintentional actions by individuals that deviate from the original plan due to a lack of certain skills or knowledge23. Atmosphere refers to the environment generated by interactions among people in a specific setting24. Error management climate is defined as the organization’s response and consistent attitude towards employee errors, reflecting the organizational culture in managing mistakes. This climate can be positive or negative23,25. Positive error management involves organizations handling errors with a supportive and inclusive approach, promptly correcting them to prevent recurrence, while negative error management involves zero tolerance for errors, often leading to questioning or punishment when errors occur. This study primarily explores error management climate from a positive perspective. In a positive error management climate, organizations provide subordinates with a supportive work environment, emphasizing the acceptance and tolerance of errors26. In such a climate, the attitudes and behaviors of the organization and colleagues towards frontline nurses’ errors not only convey a sense of support to the nurses but also provide them with opportunities for learning and improvement. This, in turn, enables frontline nurses to feel a higher level of organizational support. Therefore, the error management climate may significantly affect the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. Additionally, existing literature often focuses on organizational climate at a single level27,28,29,30, overlooking the impact of multiple factors.

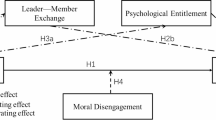

Therefore, this study constructs a cross-level influence model of platform leadership on frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. It enriches the theoretical research on platform leadership and uncovers the “black box” of how platform leadership influences frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. Additionally, it provides some reference and guidance for enterprise innovation activities and management practices.

Hypothesis development

Platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior

Platform leadership emphasizes equality and mutual growth between leaders and subordinates, striving to expand the business platform further31. In order to promote the development and growth of the business platform, leaders actively assist subordinates in continuous growth, create a positive organizational environment, enhance support for subordinates’ work, encourage subordinates to continuously improve their work skills, knowledge, and experience, actively remove various obstacles encountered in the innovation process, provide timely guidance, increase subordinates’ work motivation32, unleash their innovative potential, encourage them to develop new knowledge, technologies, and abilities, take on innovative tasks with high risks and uncertainties, provide strong logistical support to subordinates, and promote their innovative behavior33. Platform leadership prioritizes open communication, employee involvement in decision-making, and proactive authority delegation to foster innovative spirit and enhance professional development among subordinates34,35. This leadership style, which pursues equality and mutual progress, becomes a role model for subordinates to engage in active learning, constantly stimulates their innovative consciousness and curiosity36, enhancing their innovative behavior, which is the main driving force for breakthrough innovation37. Furthermore, some subordinates may lack interest and initiative in innovation; platform leadership transforms subordinates’ attitudes towards innovation, generates a sense of innovation identity, and internalizes it into innovative behavior12. Additionally, leading by example, platform leadership continuously surpasses oneself and encourages subordinates to break through themselves, values subordinates’ novel viewpoints, and provides support for various differentiated needs12,35. In an open and equal communication atmosphere, sharing platform leadership’s knowledge, experience, and skills enhances subordinates’ psychological resilience in the innovation process, stimulates their divergent thinking and creative potential34. Moreover, the work platform constructed by platform leadership can provide subordinates with the necessary knowledge, skills, information, and other resources for innovation, thereby promoting employee innovative behavior38. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1

Platform leadership is positively correlated with frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Mediating role of LMX

The establishment of LMX is predominantly shaped by the frequency and quality of interactions between superiors and subordinates39. Platform leadership is characterized by remarkable qualities such as platform construction, empowerment, equality, and mutual growth6. These characteristics render the interaction process between leaders and subordinates more likely to be of high frequency and quality. When leaders possess platform leadership, subordinates can sense the leaders’ appreciation and support. This, in turn, not only strengthens their respect and loyalty towards the leaders but also contributes to the cultivation of a collaborative and harmonious communication relationship between superiors and subordinates40. In this context, leaders tend to regard frontline nurses as “insiders”. They initiate a positive interaction relationship through initial investments founded on respect and trust. As a result, frontline nurses are prompted to respond positively to the leaders’ feedback, with the intention of maintaining this high—level LMX relationship.

In the case of subordinates, engaging in innovative behavior is fraught with risks and uncertainties. However, a good leader—member relationship has been proven to promote innovation41. There are several mechanisms through which LMX influences frontline nurses’ innovative behavior: Firstly, frequent information exchange with leaders serves as a valuable source of resources and information for innovation42. Secondly, high-quality LMX endows subordinates with greater autonomy. This enhanced autonomy strengthens their sense of responsibility, which in turn leads to more innovative efforts within their expanded job roles43. Thirdly, a strong leader—employee relationship builds trust. Trust motivates subordinates to take on challenges, and leaders are also involved in assisting subordinates in problem—solving throughout the process, which can spark innovation44,45. Fourthly, a quality leader—member exchange offers subordinates challenging tasks, decision—making opportunities, and autonomy15. These positive signals activate frontline nurses’ sense of psychological empowerment, thereby prompting them to actively engage in innovative behavior. Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2

LMX plays a mediating role between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Mediating role of relational energy

Platform leaders, as the bearers of high-level relational energy, have the ability to transfer this energy to their subordinates through interpersonal interaction rituals. This energy transfer offers subordinates emotional comfort, cognitive adjustment, and harmonious interpersonal relationships, empowering them to obtain work-related energy from these interactions39. On one hand, platform leaders actively establish a shared career-development platform. This measure enables leaders to forge positive relationships with frontline nurses and encourages high-quality interactions among the nurses. Consequently, it fosters emotional resonance within the platform, enhances the frontline nurses’ sense of team identity, and enriches their reserves of relational energy46. On the other hand, platform leaders stress the significance of boundaryless communication and interactive learning with colleagues47. During the process of communication and interaction, emotional convergence takes place, which facilitates the dissemination of relational energy within the team19.

Innovative behavior represents a continuous state, and an adequate supply of psychological resources is indispensable for its sustenance. As a positive emotional resource, relational energy exerts a positive and facilitating influence on the innovative behavior of frontline nurses. Firstly, relational energy expands subordinates’ cognitive horizons, alleviates the adverse impacts of work-related stress48, bolsters their confidence in achieving innovation success, and channels their focus towards team innovation efforts. Secondly, relational energy fosters shared interests among team members and cultivates a sense of moral righteousness grounded in group symbols. This encourages members to engage in positive actions that align with such moral values and responsibilities49. Lastly, relational energy disseminates group norms, motivating subordinates to shoulder more work responsibilities as a reciprocation for organizational support. This, in turn, ignites their enthusiasm for work goals and paves the way for the realization of innovative behaviors50. Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is put forward.

H3

Relational energy plays a mediating role between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

LMX and relational energy in the chain of mediation

As a positive emotional resource, relational energy is formed through interaction processes among individuals within the hospital. It is not only a concrete manifestation of individuals’ internal psychology but also transcends individual social relationships or attributes. According to the Interaction Ritual Chain Theory, participants in interaction rituals have differences in status and power, leading to varying levels of relational energy obtained from group interactions51,52. High-level LMX is more conducive to the derivation of relational energy, facilitating the transfer and diffusion of relational energy from superiors to subordinates19. Conversely, in low-level LMX relationships, subordinates tend to avoid mutual attention and emotional symbol transmission among members, detach from emotional bonds, release negative emotional energy, leading to the decline of relational energy53. According to the Interaction Ritual Chain Theory, group assembly and common events are the “prerequisite elements” of interaction rituals, which can trigger group enthusiasm, activate relational energy, and form common moral standards through the formation of common focus and emotional bonds, pushing the formation of positive organizational behaviors and other “resultant elements”. Firstly, the common career platform built by platform leaders can shape broader “ritual boundaries” within the team, attracting frontline nurses with common values to participate, and fostering good LMX relationships. Secondly, high-level LMX enables frontline nurses to cultivate common emotions, set common goals, develop common symbols, form emotional resonance through interaction rituals, and thus enhance relational energy reserves. Finally, enriched relational energy helps subordinates increase their satisfaction with the organization and work, fully engage in innovation activities54, and achieve a high level of innovative behavioral state. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4

LMX and relational energy play a chain-mediating role between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Error management climate and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior

Error management climate reflects the organization’s feedback when facing subordinates’ work errors, directly affecting subordinates’ psychology and behavior23,25. In a strong error management climate, organizations show a positive attitude towards employee mistakes, help find solutions, and learn from experiences55. Conversely, a low-level error management climate can increase subordinates’ sense of error pressure, and the fear of mistakes may stifle employee creativity, leading to negative impacts55. Additionally, the error management climate perceives mistakes as valuable learning and growth opportunities, conveying positive signals that encourage exploration in new areas and support experimental endeavors56. Subordinates do not have to worry about being criticized or ridiculed for exploring new ideas but instead receive respect and assistance from the organization56. This significantly increases subordinates’ exploratory motivation23, driving subordinates to innovate in situations where organizational resources are limited or their ideas are rejected by superiors to gain more freedom in exploring new areas57. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5

Error management climate is positively correlated with frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Moderating role of error management climate

When subordinates face major technological challenges, innovation risks, and various uncertainties in the innovation process, they may choose to fear and passively engage in minor tasks, lacking breakthrough innovative behaviors37. Only frontline nurses who are not afraid of risks and actively engage in innovation will have strong innovation resilience, be willing to overcome various technical challenges and obstacles encountered in the innovation process, and ultimately achieve breakthrough innovations. As part of organizational culture, the tolerance of work errors by the error management climate deeply influences subordinates’ willingness to implement innovation55. Organizations with a high-level error management climate exhibit greater inclusivity when facing employee errors, helping subordinates eliminate psychological insecurities generated by innovation25,58. In a strong error management climate, subordinates are encouraged to face errors positively, reducing withdrawal behaviors, and enhancing platform leadership’s impact on subordinates’ innovative behavior26. Conversely, in a low-level error management climate, hospitals with zero tolerance for errors can enhance frontline nurses’ fear of potential errors and risks, making frontline nurses hesitant to try innovation even when encouraged by platform leadership, thus weakening the positive impact of platform leadership on innovative behavior. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H6

The error management climate plays a positive moderating role in the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Data collection

The survey was divided into two sections. The first section introduced the significance of the study, assured participants that their data would be used exclusively for academic purposes, and concluded with an informed consent clause. This clause gave participants the option to select “Agree” to sign the consent form or “Disagree” to decline, thus ensuring written informed consent. The second section encompassed items related to various variables. To minimize the possibility of participants guessing the answers, the sequence of these items was randomized.

Prior to data collection, the study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Economics and Management at Pingdingshan University (Approval Number: EA-2024037). The review confirmed that the study employed anonymized interview data, safeguarded participants from harm, and did not involve experiments on humans or the use of human tissue samples. Additionally, the study did not encroach upon sensitive personal information or commercial interests. It adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. Furthermore, in accordance with relevant legislation, all participants were adults, as the legal working age exceeds the age of majority.

Data collection took place from January to April 2024. In this study, 60 hospitals were selected as research subjects to ensure the broad applicability of the findings. Assistance was obtained from individuals familiar with these hospitals, such as friends, classmates, or acquaintances. With their consent, survey links were distributed, and they were requested to invite 7 to 10 nurses to participate. Participants were assured in the survey introduction that their data would be used solely for academic purposes, without any commercial intent, and that their responses would be completed anonymously. To incentivize participation, each respondent who completed the survey was offered a small gift.

A total of 526 surveys were distributed, resulting in 466 responses. After excluding invalid surveys due to errors or missing information, 429 surveys were obtained from 54 hospitals. Two hospitals with fewer than 5 valid surveys were excluded, resulting in 422 surveys from 52 hospitals that met the quality standards recommended by the HLM software59. Geographically, the hospitals were spread across 13 in China, 7 in Thailand, 6 in Malaysia, 8 in Kazakhstan, 7 in the UK, 6 in the US, and 5 in New Zealand. Among the 422 nurses, 163 held a college degree or below (38.6%), 219 held a bachelor’s degree (51.9%), 32 held a master’s degree (7.6%), and 8 held a doctorate (1.9%), with an average age of 26.5 years (SD 3.4).

Measure

The measurement of platform leadership is based on the study by Zhang et al.60 and consists of 5 items. For example, “My leader enhances our potential by developing platforms”.

The measurement of LMX is inspired by the research of Janssen and Van Yperen61 and includes 4 items. For instance, “I trust my superior leader and support their decisions”.

The measurement of relational energy is adapted from Owens et al.19 and comprises 3 items. For example, “When I need encouragement, I choose to communicate with team members”.

Error management climate utilizes the revised Error Management Climate Measurement Scale by Cigularov et al.62. This scale includes 4 dimensions: error learning, error thinking, error communication, and error competence, with a total of 16 items, such as “People reflect on how to correct mistakes after they occur”.

Frontline nurses’ innovative behavior was measured using a 4-item scale adapted from Bani et al.63 and Wang et al.64, including the item “I often generate new and creative ideas.”

The items were actually rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 7 indicating strongly agree.

Sample common method bias test

This study emphasized the importance of balancing item sequence and ensuring respondent anonymity to mitigate common method bias in questionnaire design. Additionally, the Harman single-factor test revealed a 37.19% variance explanation rate, demonstrating successful bias control in data analysis.

Results

Reliability and validity

The factor loadings for all items in Table 1 exceed 0.60, with CR values ranging from 0.79 to 0.85 and AVE values above 0.50, indicating strong reliability and convergent validity. In Table 2, the square root of AVE surpasses the correlation coefficients between variables, demonstrating good discriminant validity.

Model fit

Table 3 presents the results of comparisons with alternative models. After a thorough and in-depth analysis, it is clear that all the fit indices of the five—factor model have reached excellent fitting standards.

Basic characteristic test

In this study, error management climate is a shared construct, with an average \(r_{wg}\) of 0.78, meeting the necessary standards65.

Hypothesis testing

Null Model

The models are detailed, indicating a within-group component (σ2) of 0.46, between-group components (τ00) of 0.13, and an ICC1 of 0.22. As per Cohen66, an ICC1 of 0.22 is significantly correlated, signifying that group differences are notable. Consequently, a general regression model is not suitable for analysis.

Level 1: \(NIB_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + r_{ij}\).

Level 2: \(\beta_{0j} = \gamma_{00} + u_{0j}\).

Mixed Model: \(NIB_{ij} = \gamma_{oo} + u_{oj} + r_{ij}\).

Random coefficients regression model

The models are presented below. As indicated by the results in Table 4, H1 is confirmed. Meanwhile, σ2 is 0.38, the effect sizes is 0.17.

Level 1: \(NIB_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + \beta_{1j} \left( {PL_{ij} - \overline{PL}_{.j} } \right) + \beta_{2j} \left( {LMX_{ij} - \overline{LMX}_{.j} } \right) + \beta_{3j} \left( {RE_{ij} - \overline{RE}_{.j} } \right) + r_{ij}\).

Level 2: \(\beta_{0j} = \gamma_{00} + u_{0j}\); \(\beta_{1j} = \gamma_{10} + u_{1j}\); \(\beta_{2j} = \gamma_{20} + u_{2j}\); \(\beta_{3j} = \gamma_{30} + u_{3j}\);

Mixed Model: \(NIB_{{ij}} = \gamma _{{00}} + u_{{0j}}\)\(+ \gamma _{{10}} \left( {PL_{{ij}} - \overline{{PL}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{1j}} \left( {PL_{{ij}} - \overline{{PL}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{20}} \left( {LMX_{{ij}} - \overline{{LMX}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{2j}} \left( {LMX_{{ij}} - \overline{{LMX}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{30}} \left( {RE_{{ij}} - \overline{{RE}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{3j}} \left( {RE_{{ij}} - \overline{{RE}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ r_{{ij}}\)

Direct and indirect effects

In Table 5, the total effect is 0.48 (p < 0.001), with a direct effect of 0.24 (p < 0.001) and an indirect effect of 0.23 (p < 0.001) observed. The indirect effects of Ind1 (PL- > LMX- > NIB), Ind2 (PL- > RE- > NIB), and Ind3 (PL- > LMX- > RE- > NIB) are 0.11, 0.07, and 0.05, respectively. Upon conducting 5000 Bootstrap iterations, it is found that the 95% confidence intervals of Ind1, Ind2, and Ind3 exclude 0. As a result, H2, H3, and H4 are validated.

Intercepts as outcomes model

The models are presented below. As indicated by the results in Table 6, H5 is confirmed. Meanwhile, τ00 is 0.11, the effect sizes is 0.15.

Level 1: \(NIB_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + r_{ij}\).

Level 2: \(\beta_{0j} = \gamma_{00} + \gamma_{01} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{EMC}_{.} } \right) + u_{0j}\).

Mixed Model: \(NIB_{ij} = \gamma_{00} + \gamma_{01} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{EMC}_{.} } \right) + u_{0j} + r_{ij}\).

Slope as outcomes model

The models and results are presented in Table 7, confirming H6. Figure 2 illustrates the moderating impact of error management climate. There, the slope of high error management climate is larger than that of low error management climate. This means that the stronger error management climate the hospital has, the stronger the moderating effect on the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior.

Level 1: \(NIB_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + \beta_{1j} \left( {PL_{ij} - \overline{PL}_{.j} } \right) + \beta_{2j} \left( {LMX_{ij} - \overline{LMX}_{.j} } \right) + \beta_{3j} \left( {RE_{ij} - \overline{RE}_{.j} } \right) + r_{ij}\).

Level 2: \(\beta _{{0j}} = \gamma _{{00}} + \gamma _{{01}} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{{EMC}} _{.} } \right) + u_{{0j}}\); \(\beta _{{1j}} = \gamma _{{10}} + \gamma _{{11}} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{{EMC}} _{.} } \right) + u_{{1j}}\); \(\beta _{{2j}} = \gamma _{{20}} + u_{{2j}}\); \(\beta _{{3j}} = \gamma _{{30}} + u_{{3j}}\)

Mixed Model: \(NIB_{{ij}} = \gamma _{{00}} + \gamma _{{01}} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{{EMC}} _{.} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{10}} \left( {PL_{{ij}} - \overline{{PL}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{11}} \left( {EMC_{j} - \overline{{EMC}} _{.} } \right)\left( {PL_{{ij}} - \overline{{PL}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{20}} \left( {LMX_{{ij}} - \overline{{LMX}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ \gamma _{{30}} \left( {RE_{{ij}} - \overline{{RE}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{0j}} + u_{{1j}} \left( {PL_{{ij}} - \overline{{PL}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{2j}} \left( {LMX_{{ij}} - \overline{{LMX}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ u_{{3j}} \left( {RE_{{ij}} - \overline{{RE}} _{{.j}} } \right)\)\(+ r_{{ij}}\)

Discussion

This study expands the theories related to leadership styles. Previous research has comprehensively demonstrated distinct ways in which different leadership styles impact employees’ behavior. Transformational leaders exert their influence through charisma, captivating their teams with their vision and enthusiasm, and inspiring them to achieve beyond their self-perceived capabilities1. Charismatic leaders, with their extraordinary charm and personal magnetism, serve as powerful role—models, leaving a profound imprint on their followers, guiding them to adopt similar values and behaviors in the workplace67. Inclusive leaders, with their high level of awareness and sensitivity, are adept at meeting the diverse needs of their subordinates, creating an environment where everyone feels valued and respected, thus tapping into their latent potential and enabling them to contribute more effectively to the organization68,69. Servant leaders, by prioritizing serving their subordinates, not only meet the immediate needs of their team members but also foster a culture that is in line with the organization’s mission, promoting long—term commitment and loyalty among employees70. This study validates that platform leadership is positively correlated with frontline nurses’ innovative behavior, providing empirical support for the viewpoints put forward by relevant scholars31,32,47.

This study unveils the transmission mechanism from platform leadership to frontline nurses’ innovative behavior, specifically the mediating roles of two variables, namely LMX and relational energy, in this process. Platform leadership nurtures high-quality LMX through frequent and trust-based interactions, thereby enhancing frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. LMX acts as a mediator in this relationship by offering resources39,41, autonomy42, trust44, and challenging tasks15. Collectively, these elements empower nurses to engage in innovation. Meanwhile, platform leadership cultivates relational energy via shared development platforms and boundaryless communication46,47. This energy, conveyed through emotional and cognitive support, broadens nurses’ cognitive horizons, reinforces shared goals48, and aligns their behaviors with group norms50, thus sustaining their innovative endeavors. Both LMX and relational energy serve as crucial psychological mechanisms that connect platform leadership with innovation. LMX emphasizes resource-enabled empowerment, while relational energy focuses on emotionally-driven motivation.

This study explores the direct effect of the error management climate, an organizational-level factor, on frontline nurses’ innovative behavior, as well as its moderating role in the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. The error management climate significantly propels frontline nurses’ innovative behavior by fostering psychological safety and exploratory motivation. A robust error management climate encourages constructive responses to errors, reducing the fear of criticism and inspiring risk-taking in the pursuit of novel solutions23,55. It reframes mistakes as learning opportunities, empowering nurses to conduct experiments even in the face of resource constraints or leadership resistance56. This environment enhances nurses’ willingness to surmount technical challenges and pursue breakthrough innovations. The error management climate also positively moderates the relationship between platform leadership and innovation. A high-level error management climate alleviates innovation-related insecurities, enabling nurses to embrace leadership encouragement without fearing punitive consequences for potential errors26,58. Conversely, a low-level error management climate exacerbates risk aversion, weakening the influence of leadership by intensifying nurses’ hesitation to innovate55. Effective error tolerance, therefore, amplifies the leadership’s ability to stimulate innovative behaviors.

Theoretical contribution

On the one hand, the extant literature has delved into the positive impact of platform leadership on subordinates from perspectives such as social cognition, social exchange, or work resources12,33,34,37. However, the theoretical exploration in this area still has room for expansion. This study makes significant theoretical contributions by integrating positive psychology theories. By leveraging the interactional ritual chains theory and LMX theory, it delves into the intricate mechanism of how platform leadership impacts front-line nurses’ innovative behavior. The finding that LMX and relational energy partially mediate this relationship represents a major theoretical innovation. It not only enriches the understanding of platform leadership’s role in fostering high—quality social exchanges between supervisors and subordinates, which in turn promotes team interactions, but also reveals that platform leadership can effectively facilitate the transfer and spread of relational energy, enhancing positive energy activation. These results break new ground in the theoretical framework of platform leadership research, providing a fresh and in-depth perspective for scholars to understand the far-reaching impact of platform leadership on individual innovative behavior.

On the other hand, previous research on error management climate has been predominantly confined to a single-level analysis27,28,29,30. Converting organizational-level variables into individual-level characteristics without applying multilevel analysis techniques, although acknowledging the influence of organizational factors, significantly weakens the explanatory power of the research theory71. This limitation in the existing theoretical framework calls for a more comprehensive and rigorous approach. This study addresses this gap and makes a substantial theoretical contribution. By revealing the significance of group differences in error management climate, it emphasizes the need to consider both individual and organizational variables through hierarchical linear modeling. This innovative analytical approach not only provides a more accurate and detailed understanding of the complex relationship between error management climate and front-line nurses’ innovative behavior but also sets a new standard for future research in this field. It encourages scholars to take into account the multi-level nature of variables, enabling a deeper exploration of how these variables interact across different levels to influence front-line nurses’ innovative behavior. This research thus broadens the theoretical scope of error management climate research and offers valuable insights for the development of more effective leadership and innovation-promoting strategies.

Practical implications

Firstly, actively incorporate the platform concept into organizational development. In contrast to traditional leadership models, platform leadership emphasizes the construction and enhancement of a shared platform that fosters mutual growth and potential empowerment between leaders and subordinates. This approach aligns with frontline nurses’ strong motivations for self-fulfillment and self-expression. Therefore, managers should establish a common platform for collaborative efforts, embed a people-centric philosophy into organizational management practices, provide frontline nurses with resources and emotional support, and cultivate an environment conducive to innovation. Additionally, managers should adopt inclusive management strategies to enable frontline nurses to showcase their talents, encourage subordinates to co-develop the platform, and foster a sense of ownership among team members.

Secondly, optimize LMX levels. By fostering high-quality internal team relationships, hospitals can alleviate the work pressure of frontline nurses and promote a positive state of innovative behavior. Specifically, hospitals can organize leaderless team-building activities or boundary-less discussions to facilitate smooth communication between superiors and subordinates, thereby enhancing trust and mutual reciprocity within the team. Moreover, during resource allocation and empowerment, managers should avoid favoritism, adopt an open and inclusive mindset, blur the boundaries of “relationship circles,” and reserve development opportunities and advancement spaces for individuals outside these circles. This approach reduces polarization within leadership relationships and drives the organization’s long-term development.

Thirdly, continually enhance relational energy. Managers can strengthen team cohesion by creating a shared platform for collaborative efforts, establishing mutual learning groups, and activating frontline nurses’ shared emotional states and values. Through verbal and non-verbal interpersonal interactions, managers can maintain frontline nurses’ high energy levels for innovation activities. Additionally, inspiring educational initiatives for frontline nurses within the team can improve interaction and communication between leaders and nurses, transmit positive energy through emotional exchanges, and sustain their abundant energy in innovation activities.

Lastly, cultivate and strengthen an error-friendly atmosphere within the hospital. In terms of management practices, managers should establish open communication mechanisms within the hospital to support members in discussing, analyzing, and learning from mistakes. This approach helps guide frontline nurses to perceive errors correctly. Through cultural development, regular seminars on error management processes and norms can integrate themes of exploration, inclusivity, and encouragement into the organizational culture, reducing frontline nurses’ concerns about potential mistakes in innovation activities. In terms of system improvement, hospitals should develop clear error management systems, including processes for discovering, reporting, analyzing, and resolving errors. This ensures that frontline nurses have sufficient confidence and a sense of security to report mistakes in innovation activities.

Limitations and future directions

Firstly, the application of cross-sectional methods faces challenges in accurately examining the dynamic operational processes of variables. Cross-sectional research collects data at a single point in time, making it difficult to track how variables change and interact over time. To improve the accuracy of the research, future studies could adopt a longitudinal design. A longitudinal approach enables researchers to track changes in variables over a long period, which helps in achieving a deeper understanding of their dynamic interrelationships.

Secondly, since the study was based on data from seven countries, the diverse cultural backgrounds of these nations may have affected the findings. Cultural factors, such as values, beliefs, and social norms, can have a significant impact on human behavior and the variables being studied. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct further research from a cross—cultural perspective. By comparing and analysing data from a wider range of cultures, researchers can gain more comprehensive insights and a more accurate understanding of the studied phenomena, which will aid in the development of more generalizable theories.

Finally, a noteworthy concern in this study is the comparatively low standard deviations (SDs, approximately ranging from 0.4 to 0.6) of the variables measured via a 7-point Likert scale. The limited variation in responses may compromise the generalizability and robustness of our research findings. There are two potential reasons for this phenomenon. On the one hand, the characteristics of the sample could be a contributing element. The participants may have shared common backgrounds, experiences, or attitudes, which led to consistent responses. On the other hand, the wording or framing of the Likert-scale items might have constrained the response range. If the questions were unclear or overly focused, it would limit the possible answers. The low SDs may weaken the statistical power and the capacity to detect significant relationships between variables. Therefore, future research should employ a more diverse sample to augment response variability. Additionally, meticulous item design and pre-testing can guarantee that the questions are clear, unbiased, and cover a broad spectrum of responses, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the results.

Conclusions

This study has produced several significant findings. Firstly, there is a positive correlation between platform leadership and innovative behavior among frontline nurses. Secondly, both LMX and relational energy serve as mediators in the relationship between platform leadership and frontline nurses’ innovative behavior. Thirdly, the error management climate is positively associated with innovative behavior and acts as a moderator in the relationship between platform leadership and innovative behavior. These findings illuminate the inner mechanisms through which platform leadership influences frontline nurses’ innovative behavior, offering valuable insights for enhancing the efficiency of human resource utilization in hospitals.

Data availability

Available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PL:

-

Platform leadership

- LMX:

-

Leader–member exchange

- RE:

-

Relational energy

- EMC:

-

Error management climate

- NIB:

-

Frontline nurses’ innovative behavior

References

Ng, T. W. Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadersh. Quart. 28(3), 385–417 (2017).

Fan, J., He, J., Dai, H., Jing, Y. & Shang, G. The impact of perceived overqualification on employees’ innovation behaviour: Role of psychological contract breach, psychological distance and employment relationship atmosphere. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 44(3), 407–422 (2023).

Fan, J. P., Fan, Y. K., He, J. & Dai, H. C. How does a good leader–member relationship motivate employees’ innovative behaviour?. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-04-2023-0180 (2023).

Chen, X. & Li, J. Articulating a vision: The impact of visionary leadership on employees’ proactive behavior. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 8(8), 54–66 (2023) (Chinese).

Voet, J. V. D. & Steijn, B. Team innovation through collaboration: How visionary leadership spurs innovation via team cohesion. Public Manag. Rev. 23(9), 1275–1294 (2021).

Hao, X., Zhang, J., Lei, Z. & Liu, W. Platform leadership: The multi-dimensional construction, measurement and verification the impact on innovation behavior. Manag. World 37(1), 186–199 (2021) (Chinese).

Hao, X. Platform leadership: A new pattern of leadership. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 4, 6–11 (2016) (Chinese).

An, S., Chen, Y. & Zhang, Y. The influence mechanism of platform leadership on employees’ individual role performance: A moderated chain mediating model. J. Technol. Econ. 41(5), 134–144 (2022) (Chinese).

Jiang, B., Wang, W. & Wang, X. The influence of platform leadership on employees deviant innovation: A moderated serial mediation model. Sci. Technol. Progress Policy 40(6), 140–150 (2023) (Chinese).

Wang, B. & Hao, X. How does platform leadership drive business model innovation? A moderated chain mediation model. J. Ind. Eng./Eng. Manag. 37(5), 23–35 (2023) (Chinese).

Cai, W. J., Lysova, E. I., Khapova, S. N. & Bossink, B. A. G. Does entrepreneurial leadership foster creativity among employees and teams? The mediating role of creative efficacy beliefs. J. Bus. Psychol. 34(2), 203–217 (2019).

Hu, D., Qin, J., Li, C. & Deng, Y. Platform leadership and employee proactivity: On the mediating role of workplace thriving and the moderating role of role breadth self-efficacy. West Forum Econ. Managemen 34(6), 68–78 (2023) (Chinese).

Wang, Y., Lan, J. & Zheng, G. Public-mindedness carries out from the top: The mechanism of leader–member exchange on the service impact of street-level bureaucrats. Pub. Adm. Policy Rev. 11(3), 29–40 (2022) (Chinese).

Chao, C., Zhang, A. & Wang, H. Enhancing the effects of power sharing on psychological empowerment: The roles of management control and power distance orientation. Manag. Organ. Rev. 10(1), 135–156 (2014).

Zhou, L., Wang, M., Chen, G. & Shi, J. Supervisors′ upward exchange relationships and subordinate outcomes: Testing the multilevel mediation role of empowerment. J. Appl. Psychol. 97(3), 668–680 (2012).

Li, Z., Ma, C., Zhang, X. & Guo, Q. Full of energy-The relationship between supervisor developmental feedback and task performance: A conservation of resources perspective. Pers. Rev. 52(5), 1614–1631 (2023).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44(3), 513–524 (1989).

Quinn, R. W., Spreitzer, G. M. & Lam, C. F. Building a sustainable model of human energy in organizations: Exploring the critical role of resources. Acad. Manag. Ann. 6(1), 337–396 (2012).

Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M. & Cameron, K. S. Relational energy at work: Implications for job engagement and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 101(1), 35–49 (2016).

Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 88(3), 518–528 (2003).

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. & Schaufeli, W. B. Recipmcal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocation. Behav. 74(3), 235–244 (2009).

Cole, M. S., Bruch, H. & Vogel, B. Energy at work: A measurement validation and linkage to unit effectiveness. J. Organ. Behav. 33(4), 445–467 (2012).

Van Dyck, C., Frese, M., Baer, M. & Sonnentag, S. Organizational error management culture and its impact on performance: A two-study replication. J. Appl. Psychol. 90(6), 1228–1240 (2005).

Keith, N. & Frese, M. Enhancing Firm Performance and Innovativeness Through Error Management Culture (Sage, 2010).

Cheng Z. Linking error management atmosphere with service employee’s thriving at work: A social information processing perspective. In 16th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management (ICSSSM2019): 2019; Shenzhen, China (2019).

Maurer, T. J., Hartnell, C. A. & Lippstreu, M. A model of leadership motivations, error management culture, leadership capacity, and career success. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 90(4), 481–507 (2017).

De-Clercq, D. & Belausteguigoitia, I. Mitigating the negative effect of perceived organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior: Moderating roles of contextual and personal resources. J. Manag. Organ. 23(5), 689–708 (2017).

Gronewold, U., Gold, A. & Salterio, S. E. Reporting self-made errors: The impact of organizational error-management climate and error type. J. Bus. Ethics 117(1), 189–208 (2013).

Horvath, D., Keith, N., Klamar, A. & Frese, M. How to induce an error management climate: Experimental evidence from newly formed teams. J. Bus. Psychol. 38(4), 763–775 (2023).

Cheng, J., Bai, H. & Hu, C. The relationship between ethical leadership and employee voice: The roles of error management climate and organizational commitment. J. Manag. Organ. 28(1), 58–76 (2019).

Pan, J. & Lin, J. Construction of network entrepreneurial platform leadership characteristics model: Based on the grounded theory. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 20(5), 958–978 (2019).

Yang, X., Jin, R. & Zhao, C. Platform leadership and sustainable competitive advantage: The mediating role of ambidextrous learning. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.836241 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Liu, R. & Chen, H. Research on influencing factors of platform leadership in business ecosystem. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 13(3), 370–394 (2022).

Ding, T., Qi, Z. & Yang, J. For the organization is for oneself: Impact of platform leadership on harmonious innovation passion of new-generation employees. J. Organ. Change Manag. 36(6), 985–1009 (2023).

Perrons, R. K. The open kimono: How Intel balances trust and power to maintain platform leadership. Res. Policy 38(8), 1300–1312 (2009).

Lee, S. M., Kim, T., Noh, Y. & Lee, B. Success factors of platform leadership in web 2.0 service business. Serv. Bus. 4(2), 89–103 (2010).

Li, L., Tao, H. & Song, H. Multilevel influence of platform leadership on employee proactive innovative behavior. Sci. Technol. Progress Policy 39(13), 133–140 (2022) (Chinese).

Ely, K., Boyce, L. A., Nelson, J. K., Zaccaro, S. J. & Hernez-Broome, G. Evaluating leadership coaching: A review and integrated framework. Leadersh. Quart. 21(4), 585–599 (2010).

Zhao, S. & Mei, Y. A study on the moderating differences of different paths of ego-depletion on the influence of moral leadership on employees’ moral voice. Chin. J. Manag. 19(9), 1325–1335 (2022) (Chinese).

Peng, A. C. & Kim, D. A meta-analytic test of the differential pathways linking ethical leadership to normative conduct. J. Organ. Behav. 41(4), 348–368 (2020).

Qu, R., Wang, Z., Jiao, L. & Shi, K. The contingent influence of leader–member exchange on researchers creativity. Sci. Sci. Manag. S& T 7, 156–165 (2013) (Chinese).

Luksyte, A. & Spitzmueller, C. When are overqualified employees creative? It depends on contextual factors. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 635–653 (2015).

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J. & Sparrowe, R. T. An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 85(3), 407–416 (2000).

Zhang, M. J., Law, K. S. & Lin, B. You think you are big fish in a small pond? Perceived overqualification, goal orientations, and proactivity at work. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 61–84 (2016).

Reimer, N. K., Schmid, K., Hewstone, M. & Ramiah, A. A. Self-Categorization and Social Identification: Making Sense of us and Them (Wiley-Blackwell, 2020).

Sumpter, M. D. & Gibson, C. B. Riding the wave to recovery: Relational energy as an HR managerial resource for employees during crisis recovery. Hum. Resour. Manage. 62(4), 581–613 (2023).

Xin, J., Kong, M. & Xie, R. Platform leadership: Concepts, dimensions, and measurements. Stud. Sci. Sci. 38(8), 1481–1488 (2020) (Chinese).

Wu, M., Wang, R., Estay, C. & Shen, W. Curvilinear relationship between ambidextrous leadership and employee silence: Mediating effects of role stress and relational energy. J. Manag. Psychol. 37(8), 746–764 (2022).

Brown, K. R. Interaction ritual chains and the mobilization of conscientious consumers. Qual. Sociol. 34(1), 121–141 (2011).

Weigelt, O. et al. Time to recharge batteries: Development and validation of a pictorial scale of human energy. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy. 31(5), 781–798 (2022).

Ferguson, T. W. Whose bodies? bringing gender into interaction ritual chain theory. Sociol. Relig. 81(3), 247–271 (2020).

Tang, X. & Pan, Y. Research on e-commerce live broadcast based on interaction ritual chain theory. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 11(6), 15–21 (2020).

Zhu, C., Zhang, F., Ling, C. D. & Xu, Y. Supervisor feedback, relational energy, and employee voice: The moderating role of leader–member exchange quality. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 34(17), 3308–3335 (2023).

Shulga, L. V., Busser, J. A. & Chang, W. Relational energy and co-creation: Effects on hospitality stakeholders’ wellbeing. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 31(8), 1026–1047 (2022).

Fan, Z., Sun, H., Zhu, P., Zhu, M. & Zhang, X. How do developmental I-deals promote team creativity: The role of team creative-efficacy and error management atmosphere. Chin. Manag. Stud. 18(1), 196–209 (2024).

Wang, X., Guchait, P. & Pasamehmetoglu, A. Anxiety and gratitude toward the organization: Relationships with error management culture and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 89, 102592 (2020).

Criscuolo, P., Salter, A. & Ter Wal, A. L. J. Going underground: Bootlegging and individual innovative performance. Organ. Sci. 25(5), 1287–1305 (2014).

Carmeli, A., Sheaffer, Z., Binyamin, G., Reiter-Palmon, R. & Shimoni, T. Transformational leadership and creative problem-solving: The mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. J. Creat. Behav. 48(2), 115–135 (2014).

Cora, J. M. & Hox, J. J. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodol. Eur. J. Res. Methods Behav. Soc. Sci. 1(3), 86–92 (2005).

Zhang, X. H. Driving R&D personnel engagement: A chain-mediation model based on the interactive energy perspective of platform leadership. J. East China Normal (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 55(6), 159–169 (2023) (Chinese).

Janssen, O. & Yperen, N. W. V. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader–member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 47(3), 368–384 (2004).

Cigularov, K. P., Chen, P. Y. & Rosecrance, J. The effects of error management climate and safety communication on safety: A multi-level study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 42(5), 1498–1506 (2010).

Bani, M. S., Zeffane, R. & Albaity, M. Determinants of employees’ innovative behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 30(3), 1601–1620 (2018).

Wang, T., Chen, C. & Song, Y. A research on the double-edge effect of challenging stressors on employees` innovative behavior. Nankai Bus. Rev. 22(5), 90–100 (2019) (Chinese).

Zohar, D. A group-level model of safetyclimate:testing the effect of group climate on microaccidents in manufacturing jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 85(4), 587–596 (2000).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn. (Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 1988).

Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J. & Puranam, P. Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 44(1), 134–143 (2001).

Qi, L., Liu, B., Wei, X. & Hu, Y. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE 14(2), e0212091 (2019).

Choi, S. B., Tran, T. B. H. & Kang, S. W. Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person-job fit. J. Happiness Stud. 18(6), 1877–1901 (2017).

Hunter, E. M. et al. Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. Leadersh. Quart. 24(2), 316–331 (2013).

Zhang, Z. The contextualization and multilevel issues in research of organizational psychology. Acta Psychol. Sin. 42(1), 10–21 (2010) (Chinese).

Funding

This study did not receive any funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ning Li and He Wang took the lead in questionnaire design, data collection, and manuscript writing. Meanwhile, Ning Li was responsible for designing the research framework and processing the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Economics and Management at Pingdingshan University (Approval Number: EA-2024037). The review confirmed that the study employed anonymized interview data, safeguarded participants from harm, and did not involve experiments on humans or the use of human tissue samples. Additionally, the study did not encroach upon sensitive personal information or commercial interests. It adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. Furthermore, in accordance with relevant legislation, all participants were adults, as the legal working age exceeds the age of majority.

Informed consent

All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Wang, H. How platform leadership stimulates innovative behavior in frontline nurses: a cross-level moderated mediation model. Sci Rep 15, 19536 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04018-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04018-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The mediating role of innovative self-efficacy between transformational leadership and innovation performance among nurses in tertiary hospitals in China

BMC Nursing (2026)

-

The impact of ambidextrous leadership on innovative work behavior among critical care nurses: a cross-sectional study

BMC Nursing (2025)